ABSTRACT

While nineteenth- and early twentieth-century trans-Tasman movement is an established historical phenomenon, architectural history still tends to consider architects as “belonging” to one nation or the other. This exploratory paper on the theme of trans-Tasman trips and tropes addresses the question of whether architects or our region can – or should – be considered wholly Australian, or New Zealander. To do this, it employs a two-pronged approach. It first examines participation in the competition for the Australian War Memorial in Canberra, held in 1925–26. Secondly, it focuses on trans-Tasman practice and movement in the history of three relatively unknown competitors: Charles Towle, Gordon Keesing, and Peter Kaad. Charles Towle was born in Australia and emigrated in his infancy; Gordon Keesing was born in New Zealand and trained in Australia. Peter Kaad was born in Fiji, and travelled to Australia for his schooling and education. This paper then considers the designs they submitted to the competition for the Australian War Memorial. Finally, it explores the various issues in the consideration of trans-Tasman movement and practice, and lines of further inquiry, that the examples of Towle, Keesing and Kaad reveal.

Studying groupings of architects can yield unexpected research trajectories. Charles Towle, for example, is one of several largely unknown architects who entered the 1925–26 competition to design the Australian War Memorial in Canberra. At the time I first pondered his identity, I was focused on the competition itself, and was probably consuming a lamington from the café on the ground floor of our faculty building: a sugar hit customarily shared with my officemate, who hailed from Christchurch. Lamingtons were a shared part of our national heritages, creating both a sibling-like bond and a mechanism for time-honoured trans-Tasman one-upping as to which nation could lay claim to its glory.

Towle stood out on this list as an entrant with a New Zealand address in an Australian competition for a monument to Australian endeavour in a conflict that was popularly conceived as the crucible of Australian nationhood. After all, there is an NZ in Anzac, even if this is something that Australians tend to overlook.Footnote1 An exploratory dig into Towle’s own history, though, reveals that what constitutes “his” side of the Tasman Sea is less easily discerned. Born in New South Wales and educated in New Zealand, Towle in fact lived and practised in both countries for extended periods, served in the armed forces of both, and participated in a range of architectural competitions. Yet in 1941, barely two years after he had moved to Australia, a New Zealand paper described him as “a Sydneyite”Footnote2; and in 1948, after having lived in New South Wales for nearly a decade, he and his wife were referred to by the Sydney Bulletin as “the Charles Towles, from Maoriland.”Footnote3

Neither definitively New Zealander nor Australian, Charles Towle seems to occupy a nether-land: adrift in the Tasman, perhaps. Is his relative obscurity, despite his relative success, a product of his vaguely defined belonging? As architectural historians of both nations looking at the early 20th century, we tend to operate in tandem rather than adopting a trans-Tasman approach. We cast an acute eye on the travels and experiences of architects within studies of their individual oeuvres, and flesh out the issues within the parameters of a home-centric gaze, focusing on the travels and homecomings of “our” architects. Yet the interconnectedness of their routes, the broader patterns that emerge, and the ramifications for our region are less well-studied. One can turf-stamp on land, but water doesn’t discriminate, and the ocean was the mechanism of connectedness within the Tasman world — and beyond. Australia and New Zealand’s relationship has always been mediated — and facilitated — by their surrounding seas. With this interconnectedness in mind, it makes sense to broaden our constructs in looking at architects and their practices. Perhaps this fluidity of border and identity provides a way in which to understand practice within our region. Perhaps, like the lamington, Towle in fact belongs to both New Zealand and Australia.

In keeping with this special issue’s theme of Trans-Tasman Trips and Tropes, this exploratory paper considers to what extent architects can — or should — be considered wholly Australian, or New Zealander, if there is evidence to suggest trans-Tasman links. Its approach is two-pronged, conducted first through an examination of participation in the competition for the Australian War Memorial in Canberra (AWM). Unlike many war memorial competitions, that for the AWM, held between 1925 and 1926, has a significant advantage for architectural historians: not only is there a complete list of competitors, but there is also a substantial collection of contemporary photographs of the designs submitted to it, found in the National Archives of Australia, as well as an unpublished review of the designs submitted to the competition by Melbourne architect and entrant William Lucas in the National Library of Australia.Footnote4 Secondly, this paper highlights trans-Tasman practice and movement in the history of three competitors. These biographies, while not exhaustive, nonetheless provide preliminary excursions in deeper study. Charles Towle’s relative obscurity and ill-defined belonging make him an obvious candidate. Gordon Keesing provides yet another permutation of identity as a New Zealand-born, Sydney-based practitioner well-known on either side of the Tasman in the 1920s. Peter Kaad is of further interest as a Scandinavian name amid a sea of Anglophones: while more firmly placeable as an Australian architect, having practised his entire career in Queensland and New South Wales, Kaad’s background is more culturally diverse than first anticipated. This paper then considers the designs for the AWM submitted by these three competitors. Finally, it explores the various issues in the consideration of trans-Tasman movement and practice and some potential lines of further inquiry revealed by the examples of these three architects.

Crossing the Ditch: From “Perennial Interchange” to Turf-Stamping

Trans-Tasman movement is a well-documented historical phenomenon. In 1988, drawing on decades of his own research into the reasons, mechanisms and impacts of the history of what has long been colloquially known as “crossing the ditch,” historian Rollo Arnold commented that:

[a]ny real probing of the trans-Tasman relationship quickly throws up a curious blend by of certainties and ambiguities, of subtle shifts between near and far and between shifting and emigrating, of uncertainty about one people or about two peoples, of interplay between strangers and brothers.Footnote5

Of course, the sibling-like relationship implied by a shared history of British colonisation belies the long, rich histories of the First Nations peoples of each land. The diverse islands and communities in the south Pacific had been grouped together in the European mind as “Australasia,” regardless of indigeneity.Footnote6 In 1890, the term was formalised, comprising the British colonies of Australia, Tasmania, New Zealand and Fiji; Australia federated in 1901, but New Zealand demurred, instead obtaining Dominion status in 1907.Footnote7 Travel between the colonies was unhindered by processes of immigration up until the First World War, with these only formalised in 1920.Footnote8

The significance of “steady two-way trans-Tasman population movements” between New Zealand and Australia — and particularly the latter’s east coast — in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries lead Arnold to characterise these as “the Perennial Interchange.”Footnote9 Since then, many historians have examined the trans-Tasman relationship from a range of perspectives, including economics, demography, migration, military and even culinary history (the Anzac biscuit and pavlova are as squabbled over as the lamington).Footnote10 Architectural history, however, has been less inclined to consider either this interchange or the broader professional relationship between the two lands as a factor within early twentieth-century practice.Footnote11 Individual travels aside, we still tend to think of architects as being either “New Zealanders” or “Australians.” As in the case of the humble lamington, this can lead to issues with claiming territory. In her 2013 study of Joseph Fearis Munnings (1879–1937), Heulwen Roberts characterised him as “largely forgotten in the country of his birth,” and sought the “inclusion of his name alongside those of other successful first-generation New Zealand architects — albeit as one whose major achievements are outside of New Zealand.”Footnote12 The degree to which an architect can be considered to “belong” to one country is harder to assess when so many variables within “belonging” are at play, such as place of birth, or training, or, longest residence, or most prominent achievement. Roberts’ term “first-generation,” implying not only New Zealand-born, but also New Zealand-trained, emphasises the perceived value of the home-grown to any country’s conception of a national architecture. Yet by that same logic, surely Australia could claim the University of Auckland’s first Chair and Dean of Architecture, Cyril Roy Knight (1893–1972). Born in Sydney, serving with the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) in WW1, he received his architectural training at the University of Liverpool in England after the war, under the AIF’s scheme of non-military employment (NME).Footnote13 Furthermore, both Munnings and Knight spent periods undertaking further education and honing their skills in the United Kingdom. For some (good, if hotly felt) reason, though, we would reject any claim that either were British architects. We also fervently hold that Amyas Connell (1901–1980) and Raymond McGrath (1903–1977) were New Zealander and Australian respectively, despite both architects establishing and continuing their careers in the United Kingdom.Footnote14 Are these varied attempts to have one’s cake (or lamington), and eat it, too? The humorous yet provocative title of Geoff Mew and Adrian Humphris’ 2011 paper “The 102-foot Australian invasion of Central Wellington in the 1920s,” which mentions high-rise projects by Australian-based firms A & K Henderson and Hennessy, Hennessy & Co., hints at historical turf-stamping.Footnote15 Several other projects predate the Henderson/Hennessy ditch-crossings into New Zealand, such as Grainger & d’Ebro’s Auckland Art Gallery and Library (1887), and J.J. and E.J. Clark’s Auckland Town Hall (1911).Footnote16 Indeed, the aftermath of the 1906–07 Auckland Town Hall competition laid bare anxieties as well as rivalries. Of the forty-six entries received, all three prizes were awarded to Victorian architects. The reactions of Auckland City Council members at a special meeting called to hear the results were reported in the press.

Mr. Smeeton expressed regret that no New Zealander had been successful

Mr. Glover remarked to the same effect.

The Mayor: We had the benefit of their brains.

A Councillor: Victoria scoops the pool.

Mr. Entrican: They deserve it, I suppose.

Mr. Bagnall: They have more opportunities and larger experience than we have here.Footnote17

The second-place winners, half-brothers William and Herbert Black, submitted their collaboration from Herbert’s Melbourne address, although William had in fact been based in South Africa for nearly two decades, a circumstance which again calls nationality into question.Footnote18 Visiting New Zealand shortly after, angling to secure the commission after a blow-out in costs, William showed an almost Herculean tactlessness with his comment that Wellington’s domestic architecture was “50 years behind the times.”Footnote19 Two years later, reporting on the announcement of the competition to design Parliament House in Canberra, the New Zealand architectural journal Progress wrote that “we hope that a New Zealand Architect will win the first prize of £2000.”Footnote20 But it doesn’t all have to be rivalrous. Lamingtons can surely be shared.

Anzacs

Towle, Keesing and Kaad are all associated with First World War memorial competitions, and in particular, with the competition for the AWM in Canberra. As structures designed mostly within the first decade after the armistice, war memorials provide a distinct snapshot in time. Large scale — namely national, state and provincial — war memorials were prestigious and costly projects, often advertised Empire-wide, which brought professional fame and monetary reward to first and subsequent place-winners.Footnote21 Participation demanded significant investments in time and energy: labours of love — or of loss — for the many entrants with first-hand or family experience of service. Despite the wealth of scholarship devoted to the social and political relevance of completed monuments, the scores of alternative designs submitted to large-scale competitions have largely escaped attention, providing rich pickings for architectural historians.

The First World War’s profound effects on national identities, populations and modes of mourning have been extensively studied. The conventional, justificatory narratives declaim that both Australia and New Zealand realised their individual potential through the travails of war; the supposed “newness” of each civilisation engaged in a new, “total,” war eclipses earlier South African (Boer) War participation, and conveniently obscures the darker past of frontier conflicts. The AIF’s slouch hat and the so-called “lemon squeezer” hat worn by the New Zealand Expeditionary Force (NZEF) instantly signal the difference between the two military forces, but their broader designation as Anzacs — the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps — indicates a common colonial and regional bond.

There is also a significant crossover in identity through service. People enlisted to serve king and “country” wherever they happened to be at the time: a product of the perennial interchange.Footnote22 The University of New South Wales/Australian Defence Force Academy’s (ADFA) AIF Project website lists just under 4000 AIF members — including nurses — who were born in New Zealand.Footnote23 A manual search for “Australia” as place of birth on ADFA’s NZEF Project website yields 3516 entries, although this figure is an underestimate, as not all database entries include birthplace.Footnote24 But birth is only one factor, and “Australian” or “New Zealander” do not take into account those born in the broader south Pacific region, such as Fiji, or those who had migrated from further away and crossed the Tasman at least once in the course of settling. The criteria for designated nationality in Christopher Pugsley’s figure of 2049 New Zealanders who served in the AIF is unclear, but could include enlistees giving either New Zealand addresses or next of kin.Footnote25 Regardless of exactitude, these figures all demonstrate that “crossing the ditch” was both an established and a continuing phenomenon in that time period.

Conditional Participation

Participants in war memorial competitions, be they Anzacs, invested expatriates, or career opportunists, provide a snapshot of contemporary practice, as do the conditions of competition issued for these large-scale projects. Restrictions placed on eligibility reveal tensions between national pride and colonial inferiority complex.

Entry to the Auckland War Memorial Museum (AWMM) competition (1921) was unrestricted, with organisers seeking an Empire-wide response: memoranda were sent to architectural institutes in the United Kingdom and Canada as well as to all registered competitors.Footnote26 In the end, any cultural cringe was assuaged: all placed designs had New Zealand addresses. First prize was awarded to Auckland architects Grierson, Aimer & Draffin; all three were also NZEF veterans. Progress delightedly proclaimed that “this should completely convince the general public of the Dominion that the architectural profession of this country is on a high plane.”Footnote27 Other memorial competitions narrowed the field specifically to Australia and New Zealand, demonstrating the perceived importance of the sibling relationship in seeking a design solution — or perhaps acknowledging the trans-Tasman mobility of the profession. The Otago War Memorial (Dunedin, held 1921), for example, received 63 designs “from New Zealand, Australia and Tasmania;” the mention of the island state as a separate entity shows the continued presence of a broader regional identity over more recent federation — in the New Zealand mind, at least.Footnote28 The National War Memorial of Victoria (Melbourne, held 1923) also sought solutions from “‘Australasians,’ or British subjects residing in Australasia.”Footnote29

The competition for the nationally representative AWM (Canberra, 1925–26) was more stringently “limited to Architects who are British subjects resident or domiciled in Australia, or born in Australia and living abroad.”Footnote30 Those both born and residing in New Zealand had to meet these conditions, even if they had actually served with the Australian forces.Footnote31 Despite this privileging of “Australianness,” adjudication for the AWM was still supposed to defer to British authority: shortlisted entries were to be sent to senior Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) figure and Imperial War Graves Commission (IWGC) architect Reginald Blomfield. In the end, on reviewing all entries and deciding none were wholly feasible, the Australian committee dispensed with Blomfield’s services, invited the architects of two separate designs (Emil Sodersten and John Crust) to combine their entries, and made twelve act of grace awards with much smaller premiums than had originally been advertised.Footnote32 The resulting furore eclipsed any surrounding the Auckland Town Hall.

Assessing Participation

These examples demonstrate that the notion of nationality — of “belonging” — had various permutations. Birth, residence, and practice all emerge as qualifications. Yet in reality, birth is less relevant than it may first seem. Competitors were, after all, born before either Australian Federation or the granting of New Zealand’s dominion status: Australasian, perhaps; natural-born British subject, definitely, according to military attestation papers.Footnote33

Of the sixty-nine designs submitted to the AWM competition, three had English addresses, one from the USA, and two from New Zealand.Footnote34 All six were eligible by virtue of Australian birth, but on exploring some of their life stories, it becomes clear that one person’s “Australian” may be another’s deserter, or even recent interloper. Hubert Christian Corlette (1869–1956), author of design number 69, had lived permanently in the United Kingdom since his arrival there as an Australian architectural student in the 1890s. He had, however, nourished his Australian ties during his physical absence, serving as the Royal Australian Institute of Architects’ representative in Britain, and acting as an informal architectural ambassador of sorts for bevies of students who made their way to London in the 1920s and 1930s.Footnote35 The much younger Leslie James Hendy (1903–1969) submitted design number 67 from San Francisco, where he had only resided since 1925.Footnote36 Auckland-based architect Edward George Le Petit (1895–1983) (design number 62) was born in Tasmania, but emigrated to New Zealand with his family during his early childhood, and served with the NZEF during the war.Footnote37 Despite seemingly having stayed in New Zealand for the entirety of his career, his birth on the other side of the Tasman conferred automatic eligibility to compete. The other New Zealander was Charles Towle, who will be discussed more fully in due course.

Other “Australian” entrants had trans-Tasman origins. Melbourne-based Philip Burgoyne Hudson (1887–1952) was born in New Zealand, emigrating to Tasmania in his early teens with his widowed father and siblings.Footnote38 With his Melbourne-born (and at least partially overseas-trained) partner James Hastie Wardrop (1891–1975), a fellow AIF veteran, he submitted two schemes — nos. 6 and 19 — for the AWM, and two for the Australian Memorial at Villers-Bretonneux, France (one of which received an honourable mention). Their greatest achievement was the Shrine of Remembrance (1934), which won the Victorian competition. Gordon Samuel Keesing (entry number 31, as Hennessy, Hennessy, Keesing & Co.), who will also be discussed in due course, was also New Zealand-born, arriving in Australia to commence his architectural training. And despite only having crossed the Tasman as late as 1923, Munnings was eligible to enter as an architect resident in Australia.

These sampled practitioners show Arnold’s “perennial interchange” in action. With a mobile profession, it becomes increasingly difficult to make definite claims of national belonging. Instead, these brief examples show that region, rather than nation, may well be a more useful construct within which to examine architectural practice of the time than nation: a circumstance which the following three sketches — of Towle, Keesing and Kaad — make even more compelling.

Investigating Individuals: Towle, Keesing, Kaad

Neither Towle, Keesing nor Kaad have attracted much scholarly attention. A lone entry on the Heritage New Zealand website states that “[l]ittle is known of Auckland architect Charles Towle.”Footnote39 Secondary sources are indeed scant. His sole appearance in Susan Brookes’ Index to the Journal of the New Zealand Institute of Architects [NZIA], 1912–1980, is an obituary published in 1961,Footnote40 and he is absent from both the Encyclopedia of Australian Architecture and Peter Shaw’s History of New Zealand Architecture (1991). A single mention in Donald Johnson’s Sources of Modernism is a very brief byline to Amyas O’Connell, in which Johnson states that “Charles Towle of Sydney” designed the Auckland Cathedral.Footnote41 Similarly, Keesing has received little serious academic consideration aside from several cursory appearances in broader studies of the Australian war memorial works overseas and the IWGC, and within firm-related entries in the Encyclopedia of Australian Architecture. Peter Kaad, meanwhile, has been overshadowed by his prolific and influential practice partner Samuel Lipson (1901–95). However, searches of both Australian and New Zealand architectural media and newspapers from the period reveal that all three architects were successful practitioners who shed light on different aspects of trans-Tasman practice.

Charles Raymond Towle

Born in Young, New South Wales, Charles Raymond Towle (1896–1960) moved to New Zealand with his family in his infancy.Footnote42 He was trained in the office of Bamford & Pierce in Auckland, and joined the Auckland Architectural Students’ Association after its formation in 1914.Footnote43 One of a generation of young practitioners whose careers were interrupted by war, he enlisted for service in September 1915, and spent three years on the Western Front and in England. Returning to New Zealand in early 1919, he was discharged as medically unfit with “disordered action of the heart” (DAH), a condition attributed to “stress of service.”Footnote44

Just over a year later, following a stint in the Auckland office of Hoggard, Prouse & Gummer, Towle sailed for England via Canada and the United States with Lionel Ernest Skipwith (1896–1980), a fellow former AASA member: both men then attended the Architectural Association (AA) School of Architecture in Bedford Square.Footnote45 Towle’s travel is unsurprising, for several reasons. Firstly, his family background was financially secure and socially mobile: his father had been a manager of the Bank of New South Wales, his elder brother was a prominent barrister, and his mother and his sisters made frequent appearances in the social pages of the Auckland newspapers.Footnote46 Secondly, this was a path trodden by his employers as young men: Bamford had studied at the RIBA School of Architecture, then worked in the office of Edwin Lutyens, where he met Pierce, as had William Henry Gummer.Footnote47 There is also the (uncorroborated) suggestion that Towle had formerly attended the AA for three months in 1918, during a period of leave from active service.Footnote48 The fact that at least five of Towle’s (and Skipwith’s) former fellow AASA members were studying at the AA School immediately before and after the armistice under the auspices of the NZEF was a probable further inducement.Footnote49 Towle attended the AA School for around one year: in August 1921, his design for a church steeple appeared in the AA Student Exhibition and was briefly praised in British architect H.S. Goodhart Rendel’s published criticism of the display, and he was admitted as an Associate of the Royal Institute of British Architects.Footnote50 Reporting on this achievement, the Auckland Star noted that Towle had “just accepted a position for twelve months on the staff of an eminent architect engaged in work in India,” namely Ambrose Poynter.Footnote51 After returning to England to undertake further architectural work with J.E. Franck and Wallis, Gilbert & Partners, and a planned sketching tour to Europe, Towle finally left the shores of “Home” (in the colonial sense) for the South in December 1924.Footnote52

Arriving in Sydney on the Hobson’s Bay, and proceeding to Canberra, Towle forged architectural and administrative connections, becoming acquainted with Australian Commonwealth architect John Smith Murdoch (1862–1945). The most probable means of introduction was Frederick Greenfield Ward, a former AIF chaplain and the incumbent rector of the Anglican church of St John in the new federal capital, Canberra, who had married Towle’s sister Margery in 1918.Footnote53 Despite having given his country of intended future residence on the Hobson’s Bay’s passenger list as Australia, however, Towle returned to New Zealand within a few months. Correspondence reveals that this may have been due to an ongoing illness.Footnote54 On 22 June 1925 he wrote to Murdoch that

I have been “in dock” again since reaching Auckland, and had another operation. I am fit again now, however, and am at present working in an office here, preparatory to starting practice on my own. I imagine there will be opportunities here for a man just starting: of course, it is bound to be slow at first.Footnote55

Murdoch replied with concern, stating that he was sorry “that you have been ailing again. In fact, I heard of this from Mr Ward,” indicating a relatively solid social connection. Of work prospects, he reassured Towle that “I hear there is more movement in Auckland than in many of the other New Zealand towns, and trust that this will continue until you get a footing with the practice you contemplate beginning.”Footnote56

Towle also asked about the forthcoming competition for the Australian Memorial at Villers-Bretonneux, France, for which Murdoch would become an assessor. “Are the conditions out yet? and if so, to whom should I apply for a copy?” he asked; “I am very anxious to compete, as I know that part of the battlefields so well.”Footnote57 Murdoch replied that he was

not altogether sure, however, whether you would be qualified for this Competition, the latest intention with regard to which is that it will be confined to Architects who served with the Australian forces, and the fathers of such Architects. Of course, this qualification may be altered, but that is the idea as the matter stands at present. However, for the National War Museum at Canberra there will be no doubt about your qualification. You are acquainted with the site of the building, which should perhaps assist you a little in forming a definite idea as to what may be a suitable design for it. I think copies of the Conditions will be available at Wellington, but in case that may not be so, it might be advisable for you to write to Mr Daley about the end of July and ask him to send you the Conditions, and register your name as a competitor…Footnote58

Towle took Murdoch’s kindly advice and focused on the far more lucrative AWM competition, submitting a design (), even though the conditions for Villers-Bretonneux were subsequently changed to allow entry to Australian-born architects who had served with the NZEF. His career also blossomed. He started the business he had envisaged — in August 1925, a press advertisement stated that he had “commenced practice in architecture at 5, (first floor), Safe Deposit Building, High Street” — and he also assumed the position of honorary secretary of the NZIA.Footnote59

Figure 1. Charles Towle, competition design for the Australian War Memorial, elevation view (1925–26). Collection: National Archives of Australia.

Figure 2. Charles Towle, competition design for the Australian War Memorial, plan view (1925–26). Collection: National Archives of Australia.

In late 1927, Towle entered into partnership with Trevor George Kissling (c.1897–c.1972), a fellow Australian-born, Auckland-trained architect.Footnote60 Their advertised tenders covered various domestic and commercial works, including stores and housing for the New Zealand Tobacco Company at Brigham’s Creek,Footnote61 and alterations and additions to the landmark home Te Kiteroa at Takapuna in order to establish the Brett Memorial Home (1930, dem. 1973), an orphanage administered by the Anglican Church.Footnote62 Again, Towle had eyes for prospects in Australia: the partnership entered the 1928 competition for an Anglican cathedral to be built across the Tasman in Canberra. Theirs was one of five entries from New Zealand firms/collaborations out of a total of forty-nine, but was not placed.Footnote63 The Sydney-based journal Building described it as “not outstanding” but “a good interpretation of an accepted [Perpendicular] style.”Footnote64 After a few years, Towle resumed sole practice. His commercial works included a warehouse for prominent cycle importer W.H. Worrall, at 28–30 Anzac Avenue (formerly known as Hercules House) (1935–36),Footnote65 and the former Bank of New South Wales in Tutanekai Street, Rotorua (1937).Footnote66

Towle’s most successful works at this time, however, were ecclesiastical. The rational classicism of his First Church of Christ, Scientist in Symonds Street, Auckland (1933) () echoed the prevailing mode expressed worldwide by the sect’s places of worship.Footnote67 The small timber Anglican church of St Margaret at Te Kauwhata (1937–38), on the other hand, referenced the characteristic and influential Anglican churches built in the nineteenth century by Frederick Thatcher for Bishop Selwyn of Auckland.Footnote68

Figure 3. Charles Towle, First Church of Christ, Scientist, Symonds Street, Auckland (1933). Collection: Auckland War Memorial Museum.

In December 1940, Towle won the high-profile competition to design the new Holy Trinity Anglican cathedral in Parnell, which had been restricted to New Zealand-registered architects. Towle’s design was most likely produced in Australia, as he crossed the Tasman on the Aorangi in April 1939, arriving in Sydney to take up a position designing “aerodrome buildings for the Commonwealth Government.”Footnote69 Again, family proved a probable link: another sister, Mary, and her husband had settled there after leaving their home in Fiji. During the Second World War Towle was granted an honorary commission in the Citizen Air Force, and worked with the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF),Footnote70 but from this time onward, traces of his Australian career are sporadic. In 1945 he occupied a temporary role as designing architect for the New South Wales housing commission, and the following year he was commissioned as town planner to the NSW settlement of Oberon.Footnote71 In 1949, Architecture briefly noted that Towle had been elected a Fellow of the RIBA: his nomination papers noted that his “work, current on boards” included club rooms, churches, flats, shops and “a 45-bed hospital.”Footnote72

If details of Towle’s later practice are sketchy, traces of his movements across the Tasman are not. Having married from his former Auckland social circle in 1948, he and his wife continued to cross the Tasman on regular occasions, possibly for both business and pleasure, as shipping and, later, air travel records reveal. They returned permanently to New Zealand in April 1957 for the long-anticipated construction of the Auckland Cathedral; the Christchurch Press reported that Towle “intended to give the work personal supervision, and to this end he [has] closed down his architectural practice in Sydney.”Footnote73 However, he became ill in late 1959, retired due to “longstanding ill health” in August 1960, and died later that year from a stroke.Footnote74 His death certificate states that he had been resident in New Zealand for 45 years, confirming that he spent the good part of two decades either in Australia or based in England: a significant portion of his career by any yardstick.Footnote75

Gordon Samuel Keesing

Gordon Samuel Keesing (1888–1972) was born in Auckland into an established Jewish family. Like Towle, he came from relative privilege, and had family links in Australia: his mother’s extensive family was based in Melbourne, and he travelled there around 1905 to commence his articles with prominent English-born architect Charles d’Ebro (1850–1920).Footnote76 The exact reason for their association is yet to be ascertained, but d’Ebro was known professionally in New Zealand through his work with John Grainger on the earlier mentioned Auckland Public Library (1884–87); d’Ebro had also made a subsequent trip on his own in 1894 to study meat- and freezing-works.Footnote77 After three years with d’Ebro, Keesing worked with J.J. & E.J. Clark, another firm with known interests on the other side of the Tasman, as the aforementioned winners of the Auckland Town Hall competition.Footnote78 A later newspaper report stated that Keesing was partly responsible for this building’s designFootnote79; however, given the closeness of the date to his supposed completion of articles with d’Ebro, any involvement would have been minimal.

In mid-1911, after a year with Kent & Budden in Sydney, a firm with several employees with significant overseas experience, Keesing travelled to England to continue his studies in architecture.Footnote80 Initial newspaper reports suggested that he would be in London “for some considerable time,”Footnote81 but he left for America within two months, where he stayed for two years while attending the Atelier Prevot in New York, and then proceeding to Paris and the Atelier Gromort.Footnote82 In 1914, his Soane Medallion entry, comprising designs for an “Official country residence for a royal personage,” received an honourable mention and was exhibited in the rooms of the Royal Society of Architects in London.Footnote83 Shortly after this major achievement, Keesing embarked on the Mahra at Gibraltar for Sydney.Footnote84

Buoyed by his recent American and European experiences, Keesing then threw himself into furthering the cause of architectural education, a role which has thus far been largely unacknowledged. Having been a founding member of the Victorian Architectural Students Society (VASS) during his time with d’Ebro, he attended the Society’s meeting in Melbourne in April 1914 and spoke for the importance of the Beaux-Arts method.Footnote85 A few months later, he argued in the Sydney-based architectural journal The Salon that “The Atelier system would go far to promote high ideals in the minds of our Architectural students,” recommending that the NSW Institute of Architects inaugurate a similar initiative.Footnote86 A further paper, drawing on his personal experience at Atelier Gromort, appeared in Building the following January.Footnote87 He also occupied a position on the Board of Examiners for the NSW Institute of Architects.Footnote88 Most significant, though, was his single-handed establishment of an Atelier in Sydney in early 1915, which was directly inspired by his own experiences: this came a mere two years after the London’s First Atelier was formed.Footnote89 The Sydney Atelier was unfortunately short-lived, given the escalating engagement of the First World War and Keesing’s own enlistment in February 1916. He also, like Towle, had an eye to opportunities across the Tasman. Immediately prior to his embarkation for war, he entered a “non-competitive” sketch in a competition for improving Cathedral Square in Christchurch, writing to the selection committee that he could not complete it before leaving; the adjudicator, Samuel Hurst Seager (himself a noted ditch-crosser), felt that it had “considerable merit.”Footnote90

Having served with the AIF Field Company Engineers on the Western Front, Keesing’s return home was delayed by a tremendous architectural opportunity: attachment to the staff of the official secretary of the Australian High Commission in London, to work with the Graves Registration and the War Graves Commission.Footnote91 He spent time in London and France, designing an Australian battlefield memorial () and selecting the sites for its erection.Footnote92 In September 1919, the Sydney journal Architecture featured perspective drawings of the massive obelisk, which Keesing had forwarded from England, together with a suggested perspective view and plan of a memorial to the missing prepared to help secure a suitable site at Villers-Bretonneux. Architecture reported that a competition for the Villers-Bretonneux memorial was envisaged, but Keesing “holds himself ineligible … owing to the close association he has had with the matter.”Footnote93 Keesing then journeyed to Gallipoli with IWGC architect John James Burnet (1857–1938), where the pair worked on the design of Australian war cemeteries and associated monuments.Footnote94 At the end of October Keesing headed south again as originally planned, although this time for a more poignant homecoming: his father had died in mid-September.

Figure 4. Gordon Keesing, AIF divisional battle memorial design (1919), Architecture: An Australian Review of Architecture and the Allied Arts and Sciences 7, no. 1 (January 1920): 23. Collection: State Library Victoria.

By this stage, Keesing had gained authority as an expert on war memorials on both sides of the Tasman. In New Zealand in the wake of his father’s death, he was interviewed by the Auckland Star on the appropriate siting and style of memorials within the Dominion, and a few weeks later he addressed “a gathering of Auckland architects” on the same topic.Footnote95 Back in Sydney, where he had brought his newly widowed mother and orphaned nephew to live, Keesing gave a lecture to the Jewish Literary and Debating Society on his experiences with the IWGC.Footnote96 His interest in and talent for commemoration continued with his win — alongside four others — in a 1920 competition held by the Sydney-based War Memorials Advisory Board for designs for moderate-cost “type war memorials,” intended for an illustrated pamphlet circulated for the guidance of smaller local groups.Footnote97 In 1923, he produced a design for a cenotaph for the community of Gosford (), the construction of which was completed the following year.Footnote98 Keesing was also concerned with the welfare of his fellow returned soldier architects, playing a prominent role in advocating for their professional needs.Footnote99

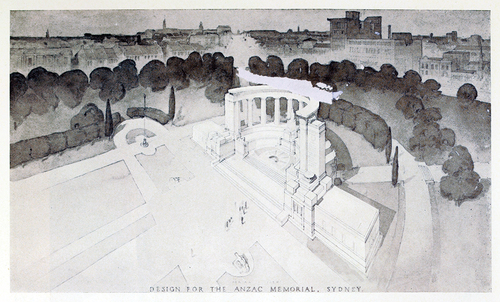

In 1924, Keesing joined the Sydney firm of Hennessy & Hennessy in partnership.Footnote100 By the time Keesing joined, its British-born and trained founder John Francis Hennessy (1853–1924) had retired, and the firm was under the direction of his son, John Francis junior (Jack junior) (1887–1956). Both father and son had worked or studied in the USA, Jack junior having attended the University of Pennsylvania.Footnote101 Hennessy, Hennessy, Keesing & Co. entered the competition for the AWM (); while Keesing had more significant experience in memorial design, the extent to which he was involved with the entry still needs to be determined. The firm also entered the competition for the Australian memorial at Villers-Bretonneux: while Keesing had intimate knowledge of both the site and the other IWGC schemes, though, his earlier declaration of ineligibility may have endured.

Figure 6. Hennessy, Hennessy, Keesing & Co., competition design for the Australian War Memorial, perspective view (1925–26). Collection: National Archives of Australia.

Figure 7. Hennessy, Hennessy, Keesing & Co., competition design for the Australian War Memorial, plan view (1925–26). Collection: National Archives of Australia.

Keesing left the partnership with Hennessy in December 1926, and spent an extended period in New ZealandFootnote102; whether this was for work, family or pleasure is not clear, but his expertise as a speaker and architectural authority was again in demand. In April, the Auckland Star sought his opinion on his home city’s growth and development.Footnote103 In July, he gave an invited address appraising exhibits at an art show; in August, he was a member of a panel speaking at the University of Auckland on art in the community; and in October, he delivered a lecture on town planning.Footnote104

In Keesing’s later years of practice, he joined Copeman & Lemont (Sydney), staying until the practice’s suspension in 1942 during the Second World War.Footnote105

Peter Alexander Kaad

The third practitioner considered in this paper, albeit more briefly, is Peter Alexander Kaad (1898–1983), who was born at Motusa on the south Pacific island of Rotuma, within the British colony of Fiji.Footnote106 His Danish father, Hans Christian Kaad, was a prominent and successful copra trader who ran ships from Fiji to both New Zealand and Australia; his Rotuman mother, Sarote Vaofouu, was an “almost legendary hostess” on their later home island of Levuka.Footnote107 Between 1911 and 1914 Kaad was a student at Newington College in Sydney, a school with strong Pacific connections which attracted students from Fijian and Tongan nobility.Footnote108 There, he apparently developed a fondness for drawing and sketching.Footnote109 Too young to serve in the First World War, he enrolled at Sydney Technical College, winning a prize for drawing in 1917.Footnote110 On entering the AWMM competition in 1921, he gave his address as “c/o Works and Railways Department, Customs House, Sydney.”Footnote111 From 1922, he was associated with Hall & Prentice in Brisbane, then H.E. Ross & Rowe in Sydney.Footnote112 He was also involved in education: the Directory of Queensland Architects notes that he was acting lecturer in design at Brisbane Central Technical College from 1922 to 1923, and a design instructor at Sydney Technical College in the 1930s.Footnote113

During the 1920s he entered several war memorial competitions. In 1922 his collaboration with W. Stanton Cook secured first prize in a competition for a monument at Mosman; his solo entry for the Auckland competition was unplaced, as was another entry the following year for a monument to be erected at Port Said to the Australian and New Zealand forces. His design for the AWM, entry no. 38 (), received one of twelve “act of grace” honoraria. Kaad submitted a further two designs for the Anzac Memorial in Sydney (competition held 1929), one of which was awarded third place (); the other, on which he collaborated with C.G. Hay, received an honorary mention.

Figure 8. Peter Kaad, competition design for the Australian War Memorial, elevation view (1925–26). Collection: National Archives of Australia.

Figure 9. Peter Kaad, competition design for the Australian War Memorial, plan view (1925–26). Collection: National Archives of Australia.

Figure 10. Peter Kaad, competition design for the Anzac Memorial, Sydney, aerial perspective (1929–30), The Home: An Australian Quarterly 11, no. 9 (September 1930): 41. Collection: National Library of Australia.

From 1934 to 1936 Kaad worked with Sydney Warden, then in 1936 commenced a successful partnership with Samuel Lipson.Footnote114

The Designs for the Australian War Memorial

The competition for the AWM presented architects with a challenge, stipulating the provision of adequate functional gallery spaces for the large collection of war relics as well as an internally located hall of memory, the walls of which were to be lined with the names of the dead.

The legacy Keesing carried from his experience of the battlefield cemeteries of France and Gallipoli in the immediate aftermath of the war was a stern commemorative vision, expressed through powerful mass. The divisional obelisks () employ a traditional commemorative form: mounted on sturdy stepped bases, though, their proportion is strikingly weighty, as if built to withstand bombardment. Keesing’s Gosford Cenotaph () takes weightiness to a further extreme, retaining the tapering of an obelisk, but increasing its sense of sheer mass through truncation and by removing the bulk of the base. More firmly anchored to the ground, with the plaques on its faces framed by slightly projecting ornament, the Gosford Cenotaph becomes more receptive to interpretation, recalling in proportion and detail both a gravestone and a military bunker, and thus the landscape of the abandoned battlefields.

The AWM scheme, on the other hand, demanded more complex and sophisticated planning. The extent to which Keesing authored Hennessy, Hennessy, Keesing & Co.’s competition entry is as yet undetermined, but both he and Hennessy junior had first-hand experience of the Beaux-Arts system of education, with its emphasis on planning and fitness of solution, and their firm’s entry demonstrates this shared experience. The building’s exterior () is a clear essay in monumental character, rooted to the ground and vividly expressing a solemn purpose: the columned entrance provides an unmistakeable, almost ceremonial, focal point. Projecting wings to either side are relieved by engaged columns, echoing the entrance and creating a visual rhythm akin to a military drumbeat, while the windowless external walls clearly indicate that this is not a structure for habitation or occupation. The shallow dome, raised on an attic and visible beyond the façade, also visually signals that a grand space is expected within, confirmed by the plan view (), which further asserts Beaux-Arts principles in its careful distribution of spaces and cross-axial symmetry. This dominating central space forms the Hall of Memory, with ambulatories placed around its perimeter to protect the space from incidental routes of passage. Between the ambulatories and the Hall of Memory is a narrow corridor, lined with the names of the dead: a slight departure from the conditions’ stipulation, but one which enabled the firm to allow the hall to be punctuated with enough entrances to allow for smooth circulation, light, and relative privacy for those searching for their loved one’s names. As an example of planning and character it could easily emerge from the pages of an early twentieth-century American journal — but as a statement of a distinctly Australian national expression it is less coherent.

A strong expression of external character is also evident in Towle’s scheme (). The entrance, similarly pushed forward from the façade, is in this case buttressed by at either side by a second mass of stone. The entranceway itself is marked by twin columns, which rely on a heavy surrounding masonry frame for effective contrast; its proportion, together with its heavy attic and even the arched frieze above the entrance doorway, invite comparison with another popular commemorative form, the triumphal arch. To either side, projecting wings are punctuated with low-set windows, again placed purposefully within blank expanses of masonry. This visual contrast of mass and void is an aesthetic which also occurs in Towle’s other work: his later First Church of Christ, Scientist in Auckland (), for example, juxtaposes windows with broad expanses of exterior wall, and weighs down its columned entranceway with a heavy attic. Similarly, the upper storey windows of his entirely unceremonial warehouse in Anzac Avenue are framed with broad expanses of masonry. And in all three, there are touches of delicate and judiciously-placed ornament. The dentils above the Memorial’s entrance, and around the entire façade of the First Church, are entirely in keeping with the rationalised classicism of each structure; the touches of delicate fluting on the warehouse display a playfulness in design. Like Hennessy, Hennessy, Keesing and Co.’s design, Towle’s elevation and perspective () delineate a raised central form; in plan, however, this square space is revealed to be a central hall separate from the required Hall of Memory, which is instead pushed to the rear of the structure, a circumstance which seems to weaken the processional sense of planning. In his design report, Towle described his plan as a “well-known ‘Aeroplane shape,’ with the Hall of Memory & its surrounding galleries forming the ‘fuselage,’ & the exhibition portion the wings.”Footnote115 The most important — devotional — spaces were apportioned to the central axis, and the lesser — utilitarian — to its subsidiary. Towle’s Hall of Memory thus gains a distinctly ecclesiastical tone through its nave-like elongation, barrel-vaulted ceiling and apse-like end; even the location of the Hall in the furthest part of the Memorial from the entrance could be likened to the hierarchical segmentation of the church from nave to chancel.Footnote116 In this way, it is tempting to see Towle’s AWM design as an initial step in the development of his interest in and aptitude for religious architecture. These idiosyncrasies aside, like Hennessy, Hennessy, Keesing & Co.’s design, the scheme is far more an expression of Towle’s overseas education than of any specifically New Zealander expression.

Kaad’s design for the AWM (), in contrast, lays an immediate and purposeful emphasis on external expression. His design report stated that “the character … externally should be one of simplicity, & a suggestion of quiet spirituality embodying the finer sentiments of self-sacrifice & valour, rather than the characteristics of the horrors of war symbolised by heavy massiveness.”Footnote117 This simple stillness is achieved by a finely wrought Ionic entrance portico unequivocally recalling a Classical temple, contrasted with blank wings to either side, the horizontality of which were intended to avoid “competing with the pyramidal form” of Mount Ainslie behind. The emphasis on commemoration was intentionally carried through by Kaad’s siting of the Hall of Memory as “the starting point & the key to circulation,” at the very front of the plan, being the first space encountered by visitors beyond the vestibule.

Despite this immediate expression of purpose, however, the relatively simplistic planning () is the real point of differentiation between Kaad’s scheme and those by Towle and Hennessy and Keesing. Large exhibition spaces are divided up by partitions rather than distributed evenly; passage through the entrance is potentially blocked by the small size of the vestibule and the tight funnelling of progress to the side halls. This sacrifice of planning for the grander symbolic vision can be explained by Kaad’s own relative inexperience. Not only was he a decade younger than Keesing, for instance, but his education was also far more limited, having trained at the Sydney Technical College, without the benefit of either American, European or British experience. However, the idealised rendition of the Greek façade, simply expressed, and his emphasis on quiet spirituality, foreshadows Kaad’s third prize design in the Anzac Memorial (), in which classical form becomes more honed, more pared back to essentials, more appropriate to a society that was moving on from academic translations of classicism to the exploration of newer modes of architectural expression.

These three designs say far more about their authors’ architectural education and practical experience than any expression of a distinct mode of design specific to one side of the Tasman or the other. The overseas experience of Keesing and Towle, moreover, was not exclusively a feature of either Australian or New Zealand architectural education: travel from the Tasman region to the larger centres of education was a shared phenomenon, a circumstance which should further strengthen the call for consideration of the broader Tasman relationship.

Further Inquiry

The examples of Towle, Kaad and Keesing each highlight various issues in the consideration of trans-Tasman movement and practice, as well as lines of further inquiry. As we have seen, Towle practised in both nations for lengthy periods of time. Announcing the results for the Auckland Cathedral in 1940, the New Zealand Herald, based in Towle’s “home” town of Auckland, wrote with a sense of pride that he was “an old boy of King’s College” who “removed to Sydney last year.”Footnote118 But in other quarters, Towle’s “belonging” was obscured. Despite the competition’s restriction to New Zealand-registered architects, as well as Towle’s relatively recent departure, several other New Zealand papers ignored this context, describing him as “a Sydney man,”Footnote119 “a Sydneyite,”Footnote120 and “of Sydney.”Footnote121 To further confuse matters, in the Gisborne Herald, Towle became simply “the Sydney architect,” while second-place winner Amyas Connell — who had by then been absent from New Zealand for over sixteen years — was (if erroneously) “the Aucklander … now resident in England.”Footnote122 Back in Australia, meanwhile, the Brisbane Courier-Mail described the relative newcomer as “the New Zealand architect.”Footnote123 “Belonging,” it seems, could swiftly become “othering,” whether intentional or unintentional. And such “othering” can in turn come full circle and lead to future convoluted assumptions and perceptions of “belonging,” such as Johnson’s characterisation of Towle in Sources of Modernism as being an architect “of Sydney.” At the end of the day, perhaps Towle was just not successful enough during his periods of residency to be considered territory worth claiming by either nation. But by taking his career as a whole, and by exploring his traces on both sides of the Tasman, a deeper picture is revealed: both of Towle himself, and of the interchange between the two nations.

Keesing is another part of this broader story of interchange. His relative anonymity is disproportionate to his contribution to architectural education and discourse, and the breadth of its reach is best revealed by a study of sources on either side of the Tasman. In his landmark study of the Australian architectural institutes, J.M. Freeland asserted that “clubs” like Keesing’s Sydney Atelier “came and went like mushrooms between 1890 and 1920,”Footnote124 but the Atelier in fact received significant press coverage in the brief time it was active. The Salon published its student drawings, publicised an Atelier exhibition, and featured a favourable review by G. Sydney Jones of its student workFootnote125; a report also appeared in the British journal Building News.Footnote126 Significantly, across the Tasman, Progress noted the “quick success” of the “valuable little institute” under Keesing, and detailed the first-year syllabus “for local guidance.”Footnote127 One wonders what might have transpired had war not intervened, particularly given Keesing’s place as a practitioner with a foot in both countries. Certainly his articles, lectures and appearances on matters relating to architecture and town planning point to an ongoing presence in the intellectual life of the profession in both Australia and New Zealand. Ann McEwan has credited Hennessy with the importation of Beaux-Arts attitudes to Sydney, citing his 1912 paper to Architecture,Footnote128 but it can be argued that Keesing was also important, given his establishment of the Sydney Atelier, and his articles on Beaux-Arts methods. And certainly, given Keesing’s demonstrated links across the Tasman, where (as McEwan has also shown) Beaux-Arts education was a developing force in architectural education, we should consider that the trans-Tasman “perennial interchange” of ideas, collegiality and collaboration is just as important as physical manifestations of practice on either side of the ditch.

Kaad provides further dimensions of inquiry, widening the idea of regionality, and casting light on the diversity of the profession. He has largely remained in the shadow of his practice partner Samuel Lipson amid increasing interest in European émigré architects and the Jewish diaspora, and the significant role played by their firm in sponsoring European architects.Footnote129 The consequence of seeing him only in relation to Lipson, and of errors about his background (in one instance he is erroneously described as Australian born of Dutch heritageFootnote130), though, slots him into a particular narrative of European-Australian interchange. In reality, with his Rotuman heritage, he was one of the first non-Caucasian/architects of colour practising in Australia, and moreover, at a time when the rumblings of White Australia were becoming increasingly heightened. His case thus opens up broader questions about architects from diverse backgrounds; about “belonging,” assimilation, prejudice, and professional camaraderie, prompting us to consider whether there might be other cases of architects whose family connections to First Nations peoples remain obscure to us. His Pacific Islander heritage is also a reminder that the trans-Tasman concept of architectural regionality could usefully be cast wider.

Conclusion

Among the things revealed by any investigation of the trans-Tasman relationship, Arnold argued, are “certainties and ambiguities.”Footnote131 In exploring the concept of national belonging enforced by conditions of competition for war memorials, the cases of Charles Towle, Gordon Keesing and Peter Kaad, and their designs for the Australian War Memorial, this paper has revealed more ambiguities than certainties. It has sought to expand what we may think of as “Australian” or “New Zealand” architects, to go beyond strict boundaries of geography and nationality, to prompt questions into the roles architects and their practices play in the “perennial interchange.” Furthermore, this idea of interchange can be usefully extended beyond physical dimensions, to encompass the ongoing reciprocal exchange of both workforce and ideas.

Instead of looking inwards to home turf, or stamping on it in an attempt to cement a certainty, or even simply operating in tandem, we can learn much by acting as siblings, dipping our toes into the Tasman and leaning into the ambiguities to see what these may reveal. Within architectural history, there is a definite role for a deeper engagement with the phenomenon of trans-Tasman movement and the identity of architects on either side of the ditch — and around the broader region. The examples of Towle, Keesing and Kaad reveal that prospects are rich and the trajectories of future inquiry are many. To explore these, one simply has to follow the (lamington) crumbs.

Acknowledgments

My thanks to Dr Rebecca McLaughlan for her fine company and ongoing encouragement. Other thanks are due to my colleague Dr Andrew Murray, Sarah Cox at the University of Auckland Library’s Cultural Collections, Helena Lunt at the Auckland War Memorial Museum, Julie Daly, archivist at Newington College, and finally to Dr Bart Ziino for bringing Keesing to my attention many years ago. All reasonable efforts have been made to gain permission for the reproduction of images in this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. For a thorough examination of the Anzac relationship, see Christopher Pugsley, The Anzac Experience: New Zealand, Australia and Empire in the First World War (Auckland: Reed Publishing, 2004).

2. “Architects’ Awards,” Grey River Argus, February 11, 1941, 4, https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/GRA19410211.2.25.

3. “Women’s Letters from Sydney,” The Bulletin, 69, no. 3594 (1948): 21, http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-552727182.

4. Architectural Competition for the design of the proposed Australian War Memorial, A3560. These photographs, part of the Mildenhall collection, were used for reproduction in the press, such as the 1927 coverage of the competition in the Sydney-based journal Building. William Lucas, “Commonwealth of Australia Federal Capital Commission, Australian War Memorial, Canberra. Architectural Competition, July 1925–February 1927,” unpublished review (1927), held National Library of Australia.

5. Rollo Arnold, “The Australasian Peoples and Their World, 1888–1915,” in Tasman Relations, ed. Keith Sinclair (Auckland: Auckland University Press, 1988), 52.

6. Nicholas Halter, Australian Travellers in the South Seas (Canberra: Australian National University Press, 2021), 29, ProQuest Ebook Central, explains that the term was first used in 1765 by French philosopher Charles de Brosses.

7. Halter, Australian Travellers, 29; Philippa Mein Smith, A Concise History of New Zealand (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 97, Cambridge Books Online.

8. Philippa Mein Smith and Peter Hempenstall, “Living Together,” in Remaking the Tasman World, eds. Philippa Mein Smith, Peter Hempenstall and Shaun Goldfinch (Canterbury: Canterbury University Press, 2009), 62–63.

9. Arnold, “The Australasian Peoples,” 53.

10. Major studies include Tasman Relations, ed. Keith Sinclair (Auckland: Auckland University Press, 1988); Remaking the Tasman World, eds. Philippa Mein Smith, Peter Hempenstall and Shaun Goldfinch (Canterbury: Canterbury University Press, 2009); A History of Australia, New Zealand and the Pacific, eds. Donald Denoon, Philippa Mein Smith and Marivic Wyndham (Oxford: Blackwell, 2000); Halter, Australian Travellers; Frances Steel, Oceania Under Steam: Sea Transport and the Cultures of Colonialism, c.1870–1914 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2011). Helen Leach at the University of Otago remains the definitive authority on the subject of the region’s edible cultures.

11. This mobility has been observed and documented by Julie Willis and Soon-Tzu Speechley in their studies of colonial networks in Asia; see Soon-Tzu Speechley & Julie Willis, “Building Networks: Professional Mobility and the Migration of Architects in the Imperial World,” in Architectural Encounters in Asia Pacific: Built Traces of Intercolonial Trade, Industry and Labour, 1800s-1950s, eds. Amanda Achmadi, Paul Walker & Soon-Tzu Speechley, (London: Bloomsbury), forthcoming. The broader field of study within our region, however, remains dramatically understudied. Travel as a phenomenon among Australian architects has been explored in Julie Willis & Katti Williams, “Travel à la Mode: Australian Architects and the Changing Nature of the International Tour,” Fabrications 31, no. 3 (2021): 357–397.

12. Heulwen Roberts, “Architect of Empire: Joseph Fearis Munnings (1879–1931)” (MA thesis, University of Canterbury, 2013), 1.

13. First Australian Imperial Force Personnel Dossiers, B2455, National Archives of Australia, Canberra (hereafter cited as B2455, NAA): Knight, Cyril Roy. For an appraisal of Knight’s contribution to New Zealand architectural education, see Julia Gatley, “‘Back to the South:’ Cyril Knight and the Modernisation of the Auckland School of Architecture,” The Journal of Architecture 25, no. 4 (2020): 396–418, and Ann McEwan, “An ‘American Dream’ in the ‘England of the Pacific:’ American Influences on New Zealand Architecture” (PhD thesis, University of Canterbury, 2001): 217–224. Gatley and McEwan both describe Knight as a defence force scholarship recipient, but that program was a New Zealand phenomenon; Australians instead participated in a scheme of non-military employment (NME), which was instigated more broadly as a means of demobilising troops in an orderly manner, while providing extra skills to assist in a return to civilian life. Several architects — and future architects — benefited from extended periods of leave for this “employment.” See Julie Willis and Katti Williams, “International Engagement, International Opportunity: Enlisted Australian Architects in World War I,” in States of Emergency: Architecture, Urbanism and the First World War, eds. Erin Eckhold Sassin and Sophie Hochhäusl (Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2022), 131–152.

14. For the relative silence on New Zealand expatriates, see Ann McEwan, “Learning in London: The Architectural Association and Early Twentieth-Century New Zealand Architects,” Interstices: Journal of Architecture and Related Arts 18 (2018): 25–36.

15. Geoff Mew and Adrian Humphris, “The 102-foot Australian Invasion of Central Wellington in the 1920s,” Architectural History Aotearoa 8 (2011): 30–35.

16. The main resource for such intercolonial efforts is the special issue edited by G. Alex Bremner and Andrew Leach, “The Architecture of the Tasman World, 1788–1850,” Fabrications 29, no. 3 (2019). For J.J. Clark’s practice more generally, his involvement in projects in New Zealand, and the Auckland Town Hall, see Andrew Dodd, “John James Clark in Australia, 1852–1915” (PhD thesis, University of Melbourne, 2009).

17. “Auckland’s Town Hall,” New Zealand Herald (Auckland), March 13, 1907, 8, https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NZH19070313.2.92.

18. William Black, letter to editor, Auckland Star, June 13, 1908, 7, https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/AS19080613.2.48.8. The duration of Herbert Black’s residence in Australia is unknown.

19. Auckland Star, June 13, 1908, 7; “Local and General News,” New Zealand Herald, May 15, 1908, 4, https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NZH19080515.2.17.

20. “Australia’s Federal Capital City,” Progress (NZ) 9, no. 12 (1914): 1201, https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/periodicals/P19140801.2.35.

21. The monographs by Inglis and Phillips are the definitive texts on memorials in Australian and New Zealand respectively: K.S. Inglis, Sacred Places: War Memorials in the Australian Landscape, 3rd edition (Carlton: Melbourne University Press, 2008); Jock Phillips, To The Memory (Nelson: Potter and Burton, 2016). See also Phillips’ earlier collaboration with Chris Maclean, The Sorrow and the Pride: New Zealand War Memorials (Wellington: GOP Books, 1990). For a history of the AWM, see Michael McKernan, Here Is Their Spirit: A History of the Australian War Memorial 1917–1990 (St Lucia: University of Queensland Press, 1991).

22. Arnold, The Australasian Peoples, 69.

23. “The AIF Project,” University of New South Wales/Australian Defence Force Academy, accessed September 30, 2023, https://www.aif.adfa.edu.au/NZBorn.

24. “The NZEF Project,” University of New South Wales/Australian Defence Force Academy, accessed October 23, 2023, https://nzef.adfa.edu.au/. Some enlisted architects known to have been born in Australia, for example, do not have a place of birth listed: Towle is one.

25. Pugsley, The Anzac Experience, 33.

26. Answers to Questions 3, 28 March 1922. Conditions for Competitive designs for Auckland War Memorial and Museum Building, Auckland Domain, June 1921, 2, in Competition for Designs, MUS-1997-20-1, Auckland War Memorial Museum (hereafter cited as MUS-1997-20-1, AWMM).

27. “Honour to New Zealand Architects,” Progress 18, no. 1 (1922): 5, https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/periodicals/P19220901.2.6.

28. “Dunedin War Memorial,” Auckland Star, July 5, 1921, 9, https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/AS19210705.2.111; “Dunedin War Memorial Competition,” Progress 16, no. 12 (1921): 271, https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/periodicals/P19210801.2.6. Again, all the placed architects had New Zealand addresses, the winner being William Henry Gummer.

29. For Gummer’s design, see Phillips, To The Memory, 143–44.

30. War Memorial Building: Architectural Competition A292, C20068 Part 1A, National Archives of Australia, Canberra (hereafter A292, C20068 part 1A, NAA): conditions of competition, condition 2.

31. Provision was made for Australians-born located overseas, with entrants directed to deliver completed drawings to offices in Sydney, London or New York; the date of release of the conditions of competition and for closing was carefully orchestrated to ensure that all competitors had the same amount of time. A292, C20068 part 1A, NAA.

32. Inglis, Sacred Places, 333–47.

33. This terminology was used on AIF and NZEF attestation papers.

34. List of competitors, Building (Sydney) (March 1927): 68, http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-273552886. Press coverage such as this referred to seventy designs being submitted, but the published list omitted number 32; the official number is taken to be sixty-nine.

35. Willis & Williams, “Travel à la Mode,” 380; “Board of Architects of New South Wales,” Architecture 16, no. 5 (May 1927): 92, http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-3007858868.

36. Hendy would later become a naturalised US citizen.

37. Le Petit’s collaboration with G.E. Downer was awarded third place in the competition for the Auckland War Memorial Museum.

38. Hudson was a pupil at the Friends’ School in Hobart from 1901–03. Author’s correspondence with Melinda Clarke, archivist of the Friends’ School, 14 September 2023.

39. “Church of the Holy Sepulchre and Hall,” Heritage New Zealand/Pouhere Taonga, accessed November 10, 2023, https://www.heritage.org.nz/list-details/98/Listing.

40. “Charles Raymond Towle (F.) FRIBA,” Journal of the New Zealand Institute of Architects 28, no. 4 (May 1961): 111–112. This obituary contains a few factual errors.

41. Donald Johnson, Sources of Modernism (Sydney: University of Sydney Library, 2002): 144, ebook, https://ses.library.usyd.edu.au/bitstream/handle/2123/7701/sup0001.pdf?sequence=1.

42. “Personal Items,” New Zealand Herald, June 22, 1914, 8, https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NZH19140629.2.85. Towle’s father died in 1914, leaving him a very healthy legacy of 600 shares in a company named Commercial Chambers Limited, which leased office spaces. Edwin Charles Towle, digitised probate record, 1914, R21455801, Archives New Zealand.

43. Towle, Charles Raymond, WW1 26.37, digitised military personnel file, R22013001, Archives New Zealand (hereafter WW1 ANZ). Towle appears in a group photograph of AASA members: see “The Auckland Architectural Students’ Association,” Progress 9, no. 1 (1915): 417, https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/periodicals/P19150901.2.12.1.

44. Towle, WW1 ANZ. Towle inflated his age by a year, giving his date of birth as 1895. Also known as “soldiers’ heart,” DAH was variously recognised as “debility,” “effort syndrome” and neurasthenia. See Arthur Frederick Hurst, Medical Diseases of the War (London: Arnold, 1918), 281–94, https://ia600905.us.archive.org/10/items/medicaldiseaseso00hursuoft/medicaldiseaseso00hursuoft.pdf

45. Towle, Charles Raymond, associateship nomination papers, RIBA Archives, London (hereafter A/RIBA). Neither Towle nor Skipwith appear in McEwan, “Learning in London.” There is one oblique reference in McEwan’s PhD thesis: an unrelated footnote states that volume 32 of the Architectural Forum was presented to the University of Auckland by a Mrs Towle in 1960. This was the year of Charles Towle’s death, and Mrs Towle was presumably his widow Madeline. McEwan, “An ‘American Dream,’” 74, n.1. The AA School of Architecture List of Students 1901–51, Archives of the Architectural Association, London, has Towle listed for 1920–21, and an “L.E. Skipworth,” presumably Skipwith, for 1920–22. Archives of the Architectural Association, London. Niagara, departing 30 June 1920, Washington, Seattle Passenger Lists, 1890–1957, roll 50, M1383, National Archives and Records Administration (Washington, DC), via ancestry.com. Towle and Skipwith embarked at Auckland for England.

46. “Obituary: Death of Mr E.C. Towle,” Auckland Star, June 29, 1914, 7, https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/AS19140629.2.68.

47. “Personal Paragraphs,” New Zealand Graphic (Auckland), January 21, 1905, 43, https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/periodicals/NZGRAP19050121.2.61. Gummer and Hoggard had also travelled in the USA. Ian Lochhead, “Gummer, William Henry,” Dictionary of New Zealand Biography (1998), Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, https://teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/4g24/gummer-william-henry. See also McEwan, “An ‘American Dream,’” 126, 204–05.

48. Towle, A/RIBA mentions “3 months in 1918,” but this is not noted beside his entry in the AA List of Students, nor in his NZEF service record, Towle, WW1 ANZ.

49. Horace Lovell Massey and Alfred Percy Morgan, for example, were still there by the time Towle arrived.

50. H.S. Goodhart-Rendel, “A Review of the Exhibition of Students’ Drawings,” Architectural Association Journal (August 1921): 40.

51. “Personals,” Auckland Star, September 10, 1921, 2, https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/AS19210920.2.10; “New Zealanders at Home (19 October),” New Zealand Herald, November 24, 1923, 12, https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NZH19231124.2.129; “Shavings,” Evening Star (Otago), March 7, 1933, 2, https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/ESD19330307.2.10.6. Towle, fellowship nomination papers, RIBA (hereafter F/RIBA).

52. Towle, F/RIBA. “New Zealanders at Home,” 12. Hobson’s Bay, Passenger lists leaving UK 1890–1960, BT27, National Archives (Kew), via Findmypast.com. Towle embarked at London for Sydney.

53. Michael Hall, “The Sentinel Over Canberra’s Military History: Some Parishioners of St John Commemorated on the ACT Memorial,” Australian Journal of Biography and History, no. 2 (2019): 83–85, https://search.informit.org/doi/pdf/10.3316/informit.682736404688293.

54. “Personal,” Auckland Star, April 4, 1925, 7, https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/AS19250404.2.48.

55. Towle to Murdoch, 22 May 1925; letter from Murdoch to Towle, 30 June 1925, A292, C20068 part 1A, NAA.

56. Murdoch to Towle, 30 June 1925, A292, C20068 part 1A, NAA.

57. Towle to Murdoch, 22 May 1925, A292, C20068 part 1A, NAA.

58. Murdoch to Towle, 30 June 1925, A292, C20068 part 1A, NAA.

59. Advertisement, Auckland Star, August 12, 1925, 5, https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/AS19250812.2.17.5. “Holiday Notices,” Auckland Star, December 2, 1925, 24, https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/AS19251202.2.194.3.

60. Kissling had previously been a representative of Gummer and Ford at their new branch in New Plymouth. “Tenders,” Taranaki Daily News, February 16, 1926, https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/TDN19260216.2.2.4; “Public Notices,” Taranaki Daily News, May 6, 1926, 1,, https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/TDN19260506.2.2.4; “Professional Notices,” New Zealand Herald, October 8, 1927, 5, https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NZH19271008.2.7.8.

61. Tender, Auckland Star, June 5, 1929, 22, https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NZH19290605.2.185.2; Tender, Auckland Star, October 12, 1929, 21, 2023, https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/AS19291012.2.219.4.

62. “Brett Memorial Home,” Auckland Star, January 9, 1920, 10, https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/AS19300109.2.124.

63. “Canberra Cathedral Design,” Building 41, no. 256 (1928): 89, 2023, http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-346869926.

64. “Canberra Cathedral Design,” 89.

65. Tender, New Zealand Herald, November 18, 1935, 22, https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NZH19351118.2.170.5. A Heritage New Zealand/Pouhere Taonga entry incorrectly states that Hercules House was later known as the Lawford Buildings; the C.E. Lawford premises was later built to occupy the space between the Tasman Buildings and Hercules House at 24–26 Anzac Avenue. “Church of the Holy Sepulchre and Hall,” Heritage New Zealand/Pouhere Taonga, https://www.heritage.org.nz/list-details/98/Listing.

66. Tender, New Zealand Herald, January 16, 1937, 21, https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NZH19370116.2.176.7. Towle, F/RIBA, records “various branches and alterations” for the Bank of NSW, Auckland.

67. Tender, New Zealand Herald, December 7, 1932, 20, https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NZH19321207.2.194.4. Paul Ivey has explored the use of classicism in the sect’s architecture, noting that while it implied “Christian primitivism” and “esoteric or specialised knowledge,” the employment of the style was not wholesale nor required by church doctrine. Paul Ivey, “American Christian Science Architecture and its Influence,” Mary Baker Eddy Library, 2011, https://www.marybakereddylibrary.org/research/american-christian-science-architecture-and-its-influence/. This impulse towards classicism is also evident in other nonconformist places of worship.

68. Tender, New Zealand Herald, August 31, 1936, 18, https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NZH19360831.2.152.1. “Awards Made,” Auckland Star, December 30, 1940, 3, https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/AS19401230.2.36, retrospectively describes St Margaret’s as “a modern version of Selwyn architecture.” For the influence of Selwyn and Thatcher on New Zealand evangelical architecture, see Margaret Alington, An Excellent Recruit: Frederick Thatcher, Architect, Priest and Private Secretary in Early New Zealand (Auckland: Polygraphia, 2007), and G.A. Bremner, Imperial Gothic: Religious Architecture and High Anglican Culture in the British Empire, c.1840–1870 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013). Towle also produced other ecclesiastical works, including a conversion of a former vestry space within the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Grafton to form a Lady Chapel (1938).

69. “Opportunities for Business,” Construction (Sydney), January 8, 1941, 14, 2023, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article222860207. Towle’s starting date is unclear. Conditions for the Auckland competition were available from December 1938, with the competition originally intended to close in December 1939; see “Competitions,” Auckland Star, December 20, 1938, 24, https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/AS19381220.2.219.2.

70. “Items from the Government Gazette,” Air Force News, April 19, 1941, 9, 2023, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-page28956491. He resigned at his own request in 1943; “Royal Australian Air Force,” Commonwealth of Australia Gazette, January 28, 1943, 370, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article232689855. Towle, F/RIBA, records RAAF employment between 1940 and 1944.