ABSTRACT

New Zealand’s first gaol was built at Okiato in 1840. Like many other gaol buildings built in this period of New Zealand’s colonial history, it has been dismissed as ad hoc and inadequate. Building on work by John Stacpoole, this paper argues that this was not the case, but instead –like the official residence of the British Resident, James Busby (now known as the Treaty House at Waitangi), – New Zealand’s earliest gaol was a deliberate design, consequent of New Zealand’s status as an extension of New South Wales (NSW), and it attributes the design to discredited NSW’s Colonial Architect Ambrose Hallen, the erstwhile editor of John Verge’s Waitangi Treaty House design. The mistaking of Hallen’s Okiato gaol as building rather than architecture was a result of its apparently rudimentary nature, and the New Zealand Centennial’s positioning of New Zealand architecture as directly inherited from Britain – consequently bypassing the significant role of NSW in New Zealand’s earliest colonial architecture, and facilitating the historical belittling of Hallen’s value as an architect.

Introduction: New Zealand’s Early Gaol Architecture

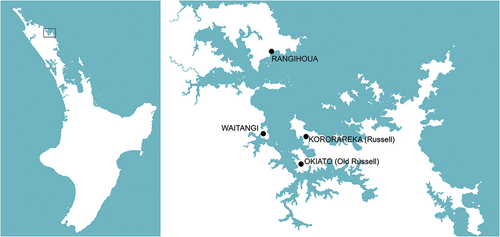

New Zealand’s first gaol was located at Okiato in the Bay of Islands (). It was a four-roomed structure made of logs built in 1840. Like other gaols built during this period in New Zealand, it has been too simply dismissed as an ad hoc and inadequate building. Jean Dunn, for example, wrote in 1948 that: “[t]he first prisons … were flimsy, consisting of a gaoler’s room, and one or two cells where prisoners lived together.”Footnote1 Likewise, P.K. Mayhew stated a decade later that “[t]he first gaols in the colony were largely facades. … There was in the colony no gaol strong enough to hold a man who had set his mind upon escaping.”Footnote2 Much later, in 2007, Greg Newbold similarly characterised early lock-ups and gaols as “makeshift structures of wood, raupo and toetoe, and so insecure that prisoners had to be restrained in irons much of the time.”Footnote3 Similar sentiments can be found in American prison histories, with both Hirsch and Rothman describing early jails as distinguished only by sturdier doors and “slightly more impressive” locks.Footnote4 This presents New Zealand gaols as repeating the architectural evolution of British prisons, so carefully documented by Evans in The Fabrication of Virtue, from the nondescript and inadequate to a fully developed architectural type.Footnote5

Figure 1. Okiato, Bay of Islands, location map, map information from Land Information New Zealand, redrawn Christine McCarthy.

The very few mentions of gaols in New Zealand mainstream or architectural histories rarely delve deeper. While a notion of architectural “evolution” from the rudimentary to increasing sophistication typifies many narratives of New Zealand colonial architecture,Footnote6 histories of New Zealand’s penal architecture typically depict the historical duration of provisional buildings as longer than that of many other architectural types. Expanding on John Stacpoole’s biography of William Mason, this paper argues that this view is deficient, and, like James Busby’s official British residence (now known as the Treaty House), New Zealand’s earliest gaol in Okiato was architecturally-designed, with its plan imported from Australia.

New Zealand as Part of the Colony of New South Wales

The building of the Okiato gaol followed the signing of Te Tiriti o Waitangi (The Treaty of Waitangi)Footnote7 in 1840, when the Crown and the leaders of some Māori iwi (tribes) agreed to allow a British government,Footnote8 while guaranteeing Māori rangatiratangaFootnote9 over their property (in the broadest sense of the word), with any land to be sold exclusively to the Crown with Māori gaining the rights of British citizenship. Ned Fletcher, in his recently published The English Text of the Treaty of Waitangi, has challenged the established view that the British intended comprehensive colonisation of New Zealand in 1840. He reminds us that: “the principal purpose of establishing government over British subjects [was] for the protection of Māori [from Pākehā] … The effect of the Treaty was to set up an arrangement similar to a federation, in which the sovereign power did not supplant tribal government.”Footnote10 He further demonstrates that “at 1840, British sovereignty was not seen as incompatible with continuing indigenous self-government.”Footnote11 Fletcher’s new understanding of what “sovereignty” meant in 1840, and renewed focus on the purpose of the Treaty to introduce British law to control British subjects in New Zealand, suggests a prime place for the architecture intended to achieve this law and control, understood within the broader administrative context of New Zealand’s colonisation.

The context leading to the Treaty signing included the appointments of James Busby, as the official British Resident in 1832, and William Hobson, as a Lieutenant Governor and Consul of New Zealand in June 1839.Footnote12 Hobson would leave for New Zealand via New South Wales (NSW) in August, arriving first at Port Jackson on Christmas Eve, and then in New Zealand on 29 January 1840.Footnote13 In preparation for his new role, he met with Richard Bourke (the former governor of NSW) in London, and with George Gipps (who had held the governorship since 1837) in Australia.Footnote14 While Hobson was still in Sydney, Gipps proclaimed that NSW had been extended to include “any territory of which the sovereignty has been, or may be, acquired by Her Majesty in New Zealand.”Footnote15 Shortly following his arrival in New Zealand, Hobson repeated Gipps’ proclamation on 30 January.Footnote16

Extending NSW to include any parts of New Zealand over which Britain acquired sovereignty was a deliberate administrative decision.Footnote17 Dalziel writes this was “a method of control that simplified annexation,” but it was also consistent with the territorial expansionist policy in NSW, following Commissioner John Thomas Bigge’s report on Lachlan Macquarie’s governorship.Footnote18 This incorporation of New Zealand into NSW’s colonial structure also built on an earlier relationship to which trade was fundamental, including the exchange of architectural ideas, building materials, and even buildings and builders. For example, the builder of Kerikeri’s Stone Store (1832–36), was George Clarke, a Sydney mason. Surveyor Gilbert Mair also “imported a carpenter from Sydney to build his house and stores.”Footnote19 Building materials included Sydney sandstone used on the Stone Store, and Australian ironbark shingles.Footnote20 Stacpoole suggested the influence of Australian (NSW or Tasmanian) houses on George Clarke’s Waimate Mission House, and cited a resemblance between NSW Colonial Architect Francis Greenway’s brick church in Liverpool, NSW, and Waimate’s wooden chapel.Footnote21 Salmond likewise writes that: “The earliest mission houses built around the Bay of Islands are typical wooden versions of contemporary brick houses in Australia.”Footnote22

Imported buildings notably included a prefabricated house made in NSW and gifted from Governor King to Ngāpuhi chief Te Pahi (?−1810) in 1806, and Busby’s official residence, or the Treaty House, named as such in the 1930s in pre-centennial iterations of nationhood because it formed the backdrop to the 6 February 1840 signing of Te Tiriti o Waitangi.Footnote23 The initial design of the Treaty House (1832–33) was by fashionable Sydney architect John Verge (1782–1861). It was prefabricated in Australian hardwood in Sydney, with the chimney made of Parramatta bricks.Footnote24

New Zealand would remain administratively linked to NSW for about a year, until a Royal Charter established it as a separate colony in November 1840, a change that came into effect in New Zealand in May 1841.Footnote25 However, NSW laws continued to operate in New Zealand until 1842 when a legislative council was established.Footnote26

The Site of New Zealand’s First Gaol

When Hobson landed in the Bay of Islands in January 1840, he brought a small contingent of officials, including Willoughby Shortland (Colonial Secretary), George Cooper (Treasurer and Collector of Customs), and Felton Mathew (Acting Surveyor-General).Footnote27 Thirty-year-old architect, William Mason, was also part of Hobson’s contingent of officials appointed in Sydney but he arrived, as the Superintendent of Works, in Kororāreka six weeks later on 17 March.Footnote28 At this time, Felton Mathew identified Okiato, near Ōpua and Ōtuihi, as the site for the new government headquarters on 23 March 1840 because it had “the most level land in the Bay,” good anchorage, and adjacent land appropriate for expansion.Footnote29

Okiato was controlled by Pōmare II (Ngāpuhi), and was occupied by ship-owner and trader James Reddy Clendon (c1801–72), who had settled there in 1832. Clendon had built a 180 foot long jetty there and “equipped the place for stores and all the facilities necessary for such a venture, including a stockade for defence.”Footnote30 In 1839 Clendon had been appointed United States Consul, resulting in significant trade at Okiato from ship captains from New England, and this “established him as the most influential European in the Bay,” contributing to the decision to buy his site.Footnote31 Okiato also had existing buildings to accommodate “the residence of a Police Magistrate, a Store, Barrack, Hospital, [and] Mechanics Workshop.”Footnote32 Additionally, Clendon’s house on the site made an appropriate Government House.Footnote33

Mathew, on behalf of Hobson, agreed to buy the property, with possession of the site from May 1840. Hobson renamed it “Russell” after Lord John Russell, the Colonial Secretary in London.Footnote34 Mathew’s July 1840 survey of the site proposed 80–90 subdivisions and streets (such as Bedford Street, Hobson Street, Melbourne Street and Emma Place).Footnote35

The Okiato Gaol

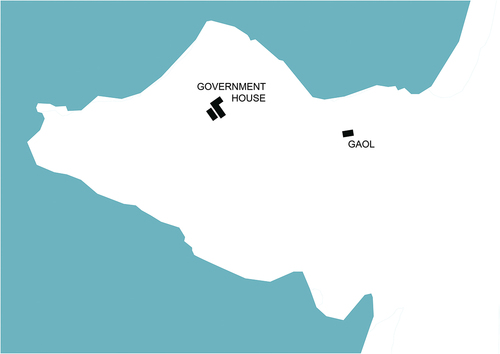

The gaol was built by July 1840, and cost £420.Footnote36 It was constructed near the police station, but outside the Government House property, which was connected to the gaol by Bedford Street ().Footnote37 Goddard states that the 80th regiment was involved in constructing new buildings, including the gaol.Footnote38

Figure 2. Gaol location, Okiato, Bay of Islands. Redrawn Christine McCarthy with additional information sourced from Goddard, “Okiato,” map information from Land Information New Zealand.

While both Dunn and Mayhew generally disparage the quality of gaol building in the colony, they suggest that the Okiato gaol was of a comparatively higher standard than other structures. Dunn described it as “a stouter structure, being made of wood, and containing a kitchen, a gaoler’s room and two cells which could each hold seven prisoners,” while Mayhew wrote that the gaol was “a comparatively formidable structure made of wood.”Footnote39 Their prime source for this distinction appears to be the colonial Blue Books, which describe the gaol as built of “stout wooden slabs” and being a log house,Footnote40 rather than any specific architectural expertise – Dunn being an MA history student, and Mayhew the Director of the Penal Division (1956–60). The stress on the comparative stoutness and formidability of a timber building contrasts other gaols built of seemingly less rigid materials, such as raupō and toetoe,Footnote41 at a time before the dominance of stone and concrete in New Zealand gaol buildings.

Neither Dunn nor Mayhew suggest that the gaol was the work of an architect, unlike Stacpoole, who would later credit the building to William Mason, stating that Mason’s initial work in the Bay of Islands was:

confined to kitchens and outhouses, a gaol, a mess house or bakehouse, and some barracks at Old Russell, and the conversion of existing buildings for a courthouse, post office, and general offices. He also put up houses for himself and for schools and boats’ crews. … the new additions seem to have been little more than shacks, providing much-needed temporary accommodation.Footnote42

Stacpoole de-emphasises the significance of Mason’s first architectural work at Okiato, describing it collectively as “little more than shacks,” and he omits the Okiato gaol from his indexing of Mason’s architectural works.Footnote43 In early July 1840, the gaol was described as:

a disgrace to any Government, in wet weather it is completely under water, and in many places you may put your hands between the boards; it is merely a wooden frame, boarded all round. The only prisoner at present in this horrid hole is a New Zealand native, who was tried some three months ago … this same man has been incarcerated ever since, and about three weeks ago the rain came into the prison half-way up to his knees.Footnote44

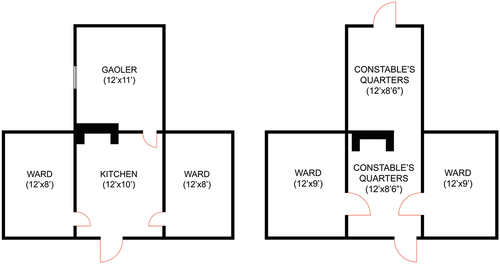

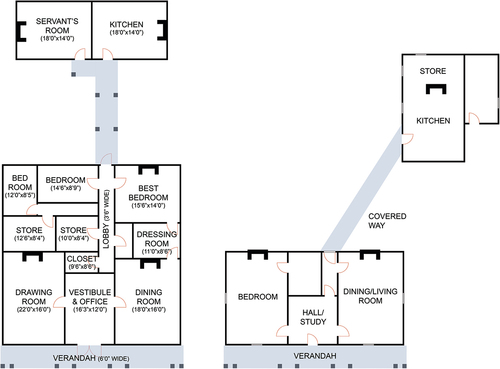

On the surface, the gaol appears like a pragmatic and vernacular response lacking architectural cunning or embellishment. This apparent naivety is well-conveyed in the neat, but amateur, Blue Book drawings and mostly, but not completely, consistently recorded dimensions: the kitchen is both 10’x13’ and 12’x10’ in 1843, and the log diameter shrinks from 15” (1842) to 12” (1843).Footnote45 One of the difficulties with the measurements provided is the kitchen dimensions of 10’x13’ and 12’x10’ indicate not just an inconsistency of dimensions, but uncertainty regarding which dimension is width and which is depth. All of the plans indicate that the gaoler’s room was wider than the kitchen, however the placement of the fireplace, and the doorway (depending on door swing) may have impacted on the perception of this. Rather than independently drawn (suggesting accuracy in their consistency), the initial plan by the gaoler – unlikely to be equipped with a measuring tape and relying on an experiential understanding of the building geometryFootnote46 – would have been copied by others to provide the multiple sets of Blue Books needed to fulfil administrative obligations, including sending copies to the Colonial Office in London. This means both the drawings and their dimensions cannot be taken at face value. A range of plan interpretations (both possible and unlikely) are presented in . This suggests that the goal had either a core of prison wards and kitchen with a lean-to gaoler’s quarters or a core of kitchen and gaoler’s quarters with the wards as wings (). The more obvious plan where the dimensions of the central kitchen align with both the wards and the gaoler’s accommodation – an option also not present in the Blue Book plans – is not generated from this process, but is another possibility. The building dimensions given in the 1841 Blue Book of 30’x12’Footnote47 may suggest the gaoler’s room was a later addition, favouring a core of wards and kitchen.

Figure 3. Okiato gaol plan variations, information sourced from Blue Books: 1842: CO 213–28; 1843: CO 213–29; IA 12–05;. Drawn Christine McCarthy.

The Blue Books’ plans present a nearly symmetrical structure, located within a 48 × 39 foot, 10 ft high log stockade.Footnote48 The gaol building’s entry is aligned with the stockade gate, and is direct into a central kitchen that accesses equally-sized wards on either side and accommodation for the gaoler at the rear – the only space with a window. The kitchen fireplace is located on an internal wall. This is uncharacteristic in its colonial New Zealand context, where more usually:

the familial hearth was not so much the heart of the New Zealand cottage as an awkward appendage. Fire was always a danger in houses made of raupo, canvas, or wood, and at first many settlers did their cooking outside on an open fire. Where bricks were available, chimney could be safety made. … The typical fireplace was a very large enclosure - … with a wall around it and its own roof; joined to the cottage at one end.Footnote49

The internal position of the fireplace consequently indicates it was built of brick and this speculation is consistent with the 1943 discovery of the location of the gaol, which noted “part of the brick floor in evidence.”Footnote50 The knowledge that the Treaty House chimneys were made of Parramatta brick may mean that the gaol’s chimney and floor were likewise built of Parramatta bricks.Footnote51

Despite this plan documentation, it is only because of Stacpoole’s brief mention that the design of the gaol can be credited to William Mason. Mason was an Englishman, initially trained by his architect-builder father before working for Thomas Telford, Edward Blore, and the Bishop of London.Footnote52 He immigrated to Sydney in 1838, where he worked for Mortimer Lewis (Governor Gipps’ Colonial Architect, 1835–49),Footnote53 prior to moving to New Zealand in 1840.

When Mason completed his first architectural work at Okiato, he was freshly arrived from Lewis’ NSW Colonial Architect’s office, which was presumably also, in 1840, New Zealand’s Colonial Architect’s office. Lewis had become Colonial Architect in 1835, following the pressured resignation from the post of Ambrose Hallen (?−1845).Footnote54 In the month after Mason arrived in Sydney, in 1838, the Colonel Architect’s office was working on four gaols, a watch house, and a police station, with another two watch houses, a gaol, and a police station in the pipe-line.Footnote55 The office had one architect, one Clerk of Works, and one draughtsperson,Footnote56 one of whom was Mason, suggesting the high likelihood of Mason’s involvement in, or knowledge of, the office’s criminal justice work. Mason’s employment in the NSW Colonial Architect’s office (an office with a significant amount of gaol-related work) and New Zealand’s administrative relationship with NSW, makes a connection between NSW gaol design and New Zealand’s first gaol at Okiato logical.Footnote57

New South Wales Gaol Design

As well as trade connections between New Zealand and NSW through whaling, sealing, flax, and timber trade, Samuel Marsden (1764–1838), the Church of England’s Church Missionary Society agent in the South Seas, was another important go-between.Footnote58 Marsden was based at Parramatta and began the first Christian mission to New Zealand at Rangihoua in 1814.Footnote59 Marsden was also the NSW penal settlement’s chaplain and appointed a magistrate in 1795.Footnote60 In these roles he acquired a reputation as the “flogging parson” criticised for giving convicts particularly severe sentences.Footnote61 Marsden’s interest in criminal justice matters extended to the design of prisons, and he is known to have corresponded with English penal reformers, including Elizabeth Fry.Footnote62 Australian prison historian, James Kerr, credits Marsden with supervising the construction of the masonry Parramatta Gaol (1802), which was based on what Kerr calls the “Sydney plan” .Footnote63 Kerr dates the “Sydney plan” gaol design to the beginning of the nineteenth century.Footnote64 It was built in Sydney and Norfolk Island, with other NSW variations in Liverpool, Newcastle, and Windsor.Footnote65

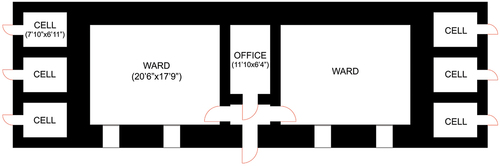

Figure 5. Parramatta Gaol, 1802, supervised by Samuel Marsden, Christian Missionary Society; dimensions cell: 7’10“x6’11;” ward: 20’6“x17’9” office:11’10“x6’4;” overall 74ftx24ft, 10 ft high thick wall 3.5’ core perimeter. Based on drawings in Kerr Design for Convicts (p. 20, Fig 23; p. 22, Fig 27 (detail), p. 47, Fig 68) and Kerr Out of Sight, Out of Mind (p. 23, Fig 15–16), many of which do not have a separate enclosed “Office.” Redrawn Christine McCarthy.

This symmetrical plan had a transverse central passage (sometimes used as an office) accessing wards on either side, with peripheral rows of three externally-accessed and equally-sized cells on both sides of the building.Footnote66 The plan thus establishes a hierarchy of spaces and access routes, where groups of prisoners in congregate wards are spatially controlled by an entrance lobby, and individual prisoners can be placed in externally-accessed solitary punitive cells. Unlike the congregate wards, the solitary cells have no windows, making them not only solitary, but dark. The location of the windows in the congregate wards indicate a directional orientation, and the rear wall sometimes formed part of a barracks wall or stockade, as occurred in the 1801 stone gaol at Norfolk Island.Footnote67 This indicates that the plan needs to be understood as part of a larger complex. Kerr describes the Sydney plan as “basically an army barrack plan with cells attached … it became a standard type in NSW.”Footnote68 However, this does not mean that most convicts at this time lived in Sydney plan gaols. Instead, prior to 1819, convicts were largely accommodated in private houses, because gaols only accommodated people who committed crimes in NSW – not all the convicts transported from Britain. As architect Francis Greenway wrote of NSW in c1814, “the whole country was the prison and […] jails were only for those who committed new crimes after setting foot on shore.”Footnote69 This was because convicts assigned to private masters were housed by their masters, and convicts assigned to government work found private accommodation paid for by undertaking private jobs outside work hours.

In the 1820s a number of changes affected this. Greenway’s Hyde Park Barracks (1817–19), which would provide convict accommodation, was completed. The increasing number of convicts transported to NSW was unable to be absorbed by the assignment system and the “territorial containment” policy of Governor Lachlan Macquarie (1810–21) was replaced with Commissioner Bigge’s policy of “territorial sprawl” from late 1820.Footnote70 This territorial expansion not only required convict labour to build public infrastructure in undeveloped areas and meet the labour needs of new sheep farmers, but it also expanded the area over which “law and order” was needed.Footnote71 One architectural consequence of this was that stockades were built outside major centres to support convict labour on building public works, assist in the process of assignment where “batches” of convicts were sent to district magistrates who assigned convicts in rural areas, and to expand the scope of law and order.Footnote72

Kerr refers to the development at this time of a “basic plan” (Plan A) (), built throughout NSW as a watch house, lock-up, and gaol, “for over half a century.”Footnote73 This symmetrical self-sufficient stockade planFootnote74 located a three-roomed gaol building as an island within the gaol yard. The building entry was direct into a central kitchen and constable quarters with a fireplace, from which two lateral windowless 10-foot square wards could be accessed.Footnote75 Despite its apparent logic and simplicity, the plan was not simply the earlier Sydney plan sans peripheral cells. Windows were removed from the wards, a fireplace was added, and the narrow passage widened to become a room, providing accommodation for the gaoler – needed because the basic plan was no longer connected to a larger penal establishment. The basic plan was built in locally-available materials (e.g. logs, timber, rubble and ashlar masonry, or brick),Footnote76 reflecting the geographic scope of its use.

Figure 6. Plan A: basic stockade plan (c1832). Based on drawing from Kerr Design for Convicts (p. 83, Fig 128) (left); Plan B: Ambrose Hallen. Design of a gaol and court house for Goulburn Plains, 1832 (based on Dixson Collection, ref: DLADD 203, YRIZNNin, State Library of New South Wales (right). Redrawn Christine McCarthy.

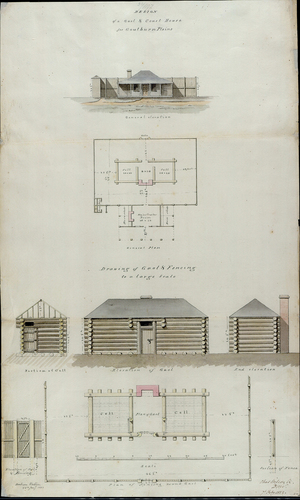

Drawings of this design and its variations are documented in an 1837 “set of plans entitled ‘Gaols, Courthouses, and Police Offices,’”Footnote77 prepared by Lewis, and currently lodged in the NSW State Archives. It contained “at least one example of every type of building needed for the enforcement of law and the punishment of offenders. There are watch-houses, police stations, court-houses, log jails, lock-ups, and - typical of the era - treadmills.”Footnote78 This included the basic plan (Plan A), a variation with a courthouse (Plan B), and an extended plan (Plan C)Footnote79 (). It would be logical to assume that these are Lewis designs,Footnote80 and Kerr in his 1984 Design for Convicts does so. However, a drawing of a Goulburn Plains proposal (Plan B) (), signed in January 1832 by Ambrose Hallen, the Colonial Architect immediately prior to Lewis, demonstrates this was not the case.Footnote81

Figure 7. Adjusted Okiato Gaol plan, Bay of Islands, Redrawn by Christine McCarthy (left). Plan C: extended basic plan c1837. Based on drawing from Kerr Design for Convicts (p. 83, Fig 129) (right).

Figure 8. Ambrose Hallen. Design of a gaol and court house for Goulburn Plains, 1832 (Dixson Collection, ref: DLADD 203, YRIZNNin, State Library of New South Wales).

The Goulburn Plains drawing incorporates the basic plan into a courthouse variation, suggesting that Plans A and B were Hallen, not Lewis, designs. The front façade presents a simple timber weatherboard house-like courthouse, with an extended hipped roof, verandah and chimney backgrounded by a 10 ft high fence. Inside the stockade, behind the courthouse, is a log cabin (a gaol), strikingly windowless excepting a barred opening above the entrance, which faces away from the courthouse. The plan has rigorous bilateral symmetry. The stockade gate, the gaol building entry, the fireplace, the back entrance into the court room and the court room’s front entrance are all on axis, aligning the courthouse and the constable’s quarters, the prisoners’ wards being reflected in it. The magistrate’s room is capped by a hipped roof that extends over a front verandah and lateral “horse sheds.” While the design effects close proximity and secure access between courtroom and gaol, it also very clearly distinguishes their architectures. The finely-scaled courtroom aesthetically contrasts the frontier rawness of the window-less log gaol, and its gaol gate, as a social and legal hierarchy is fundamental to the architectural planning and detail. “Civilisation” (the law) contrasts the seemingly rudimentary – but architecturally-designed – housing of the criminal. But this is not a crude house. It presents the aesthetic differentiation of gaol and court architecture where the language of a frontier “primitive hut” is critical to the architecture. It consequently performs the role which is often touted as distinguishing architecture from “mere” building, an ability to convey meaning.Footnote82 While Hallen was reputedly a bad architect - as we will see, his Goulburn Plains drawing and its juxtaposition of courthouse and gaol reveal the log cabin as architecturally astute because it, like Decimus Burton’s 1840s’ use of tree limbs as rustic posts at London Zoo,Footnote83 exhibits raw timber knowingly. Its aesthetic rawness clearly has the architectural intent of robust containment, and the design responded to a specific request to both replace a dilapidated gaol and address the inconvenience of holding court in “a Temporary Bark Hut.”Footnote84 It demonstrates the “basic gaol” (Plan A) as a component in an adaptive kit of parts critical to Bigge’s policy of “territorial sprawl.”

The Goulburn Plains stockade plan is important because it establishes Hallen – not Lewis – as the likely architect of the NSW “basic plan” gaol, and opens up the potential for other plans in the 1837 “Plans of gaols,” to also have an Ambrose Hallen origin.

Ambrose Hallen and John Verge: The Okiato Goal and the Treaty House

Ambrose Hallen was the NSW Colonial Architect from 1832 until 1835. His tenure as Colonial Architect ended with what have been described as “hostile and subversive” attempts to replace Hallen with Lewis.Footnote85 Hallen seems to be universally deemed incompetent or unmentioned in Australian architectural histories.Footnote86 In addition, he is also considered to have contributed little actual work. Herman, for example, writes that Hallen “did little more for Australian architecture than maintain the work of his predecessors.”Footnote87 presenting us with the contradiction of Hallen being deemed to have done no or little work to evaluate and an evaluation of incompetence. However, two contextual issues might explain these conclusions. Firstly, Hallen’s boss, Governor Richard Bourke had a specific view of gaol architecture, which Kerr characterises as prioritising “architectural [rather] than functional considerations, and more inclined to select a design and let his convict department fit a gaol into it,” suggesting that Bourke’s notion of architecture would have aligned better to Lewis’ work, because “Lewis, though competent, was primarily a man of fashion concerned with the exposition of the Greek Revival.”Footnote88 Herman characterises Lewis’ career as shifting from design purity to “eclecticism and virtuosity,” reflecting “the confused merging of the various architectural conceptions,” while, Freeland describes Lewis as an “ordinary architect,” “completely schizophrenic architecturally,” and “an architect of limited capacity whose taste lay largely in books and rules rather than innately in his heart.”Footnote89 Regardless of these historians’ evaluations, it is clear that Lewis, more effectively than Hallen, met architectural obligations to reflect contemporary values of Western architectural culture in a colonial context.Footnote90

The second contextual point worth noting is that Hallen’s tenure as Colonial Architect followed Commissioner Bigge’s report which was critical of Lachlan Macquarie’s governorship, resulting in strict instructions that opposed “the extravagant public building programmes that had addled the mind of Macquarie.”Footnote91 Freeland states that, as a consequence, other than repairs and building extensions, virtually all government building ceased for 15 years.Footnote92 This period of austerity would also impact on New Zealand’s Treaty House. When Hallen left the role of Colonial Architect and government building resumed in the mid 1830s, it was initially “much more restrained than it had been in 1815.”Footnote93 This context explains both Lewis’ shift from purity to later eclecticism and the larger number of buildings credited to him.Footnote94 It is within this context that the predecessors to the Okiato goal developed. But, this does not mean that Hallen has not been recognised for flamboyancy or inventiveness. Herman, for example, writing of Hallen’s Rosslyn Hall (1834), has stated that:

we must regret the demolition of its staircase. It is reputed to have been a circular spiral “wide enough for a coach and pair,” and since we have always wanted to see a coach and pair being driven up and down a staircase, the disappointment is a bitter one. The bedrooms were large and had a remarkable feature: each contained a bath let in flush with the floor, so that one stepped down, rather than up into it. Whether this was an innovation of Ambrose’s, or whether the baths were later additions, history does not reveal.Footnote95

Herman later referred to the inset baths at Roslyn Hall to query John Verge’s status as designing “the first authenticated bathroom in Australia,” suggesting that: “despite all the credit given to Verge in this matter,” Hallen might be the correct architect to recognise.Footnote96

The spectre of Roslyn Hall is not the only time that Verge’s status was impacted by Hallen, as Hallen was the Colonial Architect who, in 1833, infamously amended Verge’s design for Busby’s British Residence (now Treaty House, located at Waitangi, not far from the Okiato gaol site) ().Footnote97 Verge had been contracted by Busby, resulting in a proposal for a nine-room house, excluding corridors and closets, and a detached kitchen. Governor Bourke considered Verge’s design to be “far too expensive” and Hallen was instructed to rework it.Footnote98

Figure 9. Treaty House: John Verge plan (1832) (left); Ambrose Hallen plan (1833) (right) (based on McLean “Science and Research Internal Report No. 76” p. 19, Plate 2 and p. 20 Fig 2). Redrawn Christine McCarthy.

It is conventional, in New Zealand architectural historiography, for Hallen to be disparaged in his refiguring of Verge’s design. Stacpoole, for example, writes that the “[a]lterations were aimed at economy rather than architectural improvement, for Verge was a better architect than Hallen.”Footnote99 Likewise, Bill Toomath writes: “the elegance of its proportions, attest to the sophisticated hand of Busby’s leading Sydney architect, John Verge … The dignified grace of this New Zealand icon, though, conceals its niggardly beginnings … The governor had Verge’s plan reduced.”Footnote100 This discomfort with Hallen’s involvement continued to Verge’s descendent, Will Verge, who wrote in 1954 that:

Busby got a temporary instead of a finished house, and the plans were altered so that the front part of the cottage, consisting of two rooms and a lobby, were prepared under the supervision of Ambrose Hallen, Colonial Architect. … It seems that the result of Governor Bourke’s action was that Verge must share with Hallen the honour of being associated with this building - the historic British Residency at Waitangi.Footnote101

Herman (also in 1954) stated that: “from what we know of [Hallen’s …] work we are not encouraged to think any great improvements were made. However, the house did turn out to be very beautiful in appearance.”Footnote102 Again, Hallen’s reputation taints his involvement in the Treaty House regardless of its elegant proportions or beautiful appearance. History seems to condemn Hallen to be forever the bad architect. However, it is not clear that Verge’s plan () was a work of particular merit, as Herman also described Verge’s 1832 plan as:

full of waste space which would have involved, as a consequence, the transport of a great deal of unnecessary building material. The inconvenient placing of the rooms is self-evident, and the multitude of cupboards and store-rooms show that Verge did not know what to do with the surplus space caused by his awkward room arrangement.Footnote103

Freeland qualifies Verge’s design ability as relative to his provincial context, noting that “[i]n the Sydney of 1830 Verge’s building knowledge and skill were outstanding,”Footnote104 and that:

Verge was a thoroughly skilled builder who had a limited degree of remembered architectural knowledge. His planning … was weak to the point of being poor and, while his details were refined as one would expect from a well trained builder, his taste and sense of style on a large scale were underdeveloped.Footnote105

Herman likewise characterises Verge’s planning as “awkward.”Footnote106 The first Treaty House plan does not challenge this evaluation. Hallen reduced Verge’s design by about 50%,Footnote107 so that rather than only altering “the front part of the cottage,” as Will Verge suggests, Busby’s house became only the altered “front part of the cottage.” The resulting design consequently comprised “a structure of two main rooms with a large passage which could be used as a third room, if needed,”Footnote108 a description echoing that of Hallen’s basic gaol design (Plan A).

Hallen’s amendments also retained a detached kitchen, which, in Sydney, was a response to the meteorological and criminological climate. Freeland dates it to when houses “expanded beyond a couple of rooms,” and attributes this to both the unbearable heat from cooking for about eight months of the year, and the sociological convention of separate quarters for servants unable to be provided in basement servant quarters, as occurred in England, because of Sydney’s sandstone foundation.Footnote109 This separation was particularly favoured in NSW because servants were usually assigned convicts.Footnote110 These kitchens are described as being like prison cells. They had flagged floors and “small windows set halfway up the wall and barred for security against predators.”Footnote111

These impacts of convicts on Sydney’s architecture – the detached kitchen, and the NSW gaol plan – thus permeated New Zealand’s early government architectures of the Treaty House and the Okiato gaol, both of which can be linked to the “incompetent” Ambrose Hallen, and demonstrate that Okiato gaol was not only “little more than a shack,” but also originated in the NSW Colonial Architect’s office. Comparing Plan C with the Okiato gaol plan () makes this clear. The administrative context of 1840 New Zealand supports this connection as logical. It is the conventional telling of New Zealand’s penal past that is out of step.

Conclusion: Primitive Huts and Bad Architecture

Dunn (1948) and Mayhew (1959), the two penal historians who specifically refer to Okiato gaol, were writing in the aftermath of the 1940 centennial, when a strategic shift in writing New Zealand history was engineered. Rachel Barrowman states that the themes of cultural transference and adaptation were imposed on the consequent writing.Footnote112 She further states that: “It was the problem of distance: of the relationship between there and here, Britain and New Zealand, the centre and the periphery, and of how to make a cultural home in this land.”Footnote113

In Paul Pascoe’s 1940 centennial history of architecture, gaols are absent. Instead, the evolution of architecture in New Zealand was framed such that imported institutions preceded their architecture and had a direct relationship with England, bypassing the architectural significance of NSW in originating New Zealand government architecture.Footnote114 As Pascoe proclaimed: “Our Architecture Derived from England.”Footnote115 His emphasis on the avant garde of institutions sans “architecture,” protects the Centennial publications’ mandated history of cultural transference and adaptation by pointing to both the early presence of Western culture (the institution) and a later time when architectural transference and adaption had been achieved.Footnote116 Thus, built into this earliest published architectural history of New Zealand is an idea of absence, an implicit instruction not to look for fully-formed architectural ideation in the built environment in 1840 because, for Pascoe, the transfer of architecture from Britain was a deferred one. Instead we are tasked to see the unmet needs of “a highly civilised community”Footnote117 whose “primitive” buildings lack sufficient distinction and dignity.

The Okiato gaol then was likely perceived to have been too primitive for the “highly civilised” British settlers,Footnote118 fitting comfortably into that category of building that is “understood to be the form that precedes the arrival of culture.”Footnote119 Gaols in England at the time were increasingly masonry structures and presented grand, if not intimidating, elevations thought worthy of public institutions. But this centennial context only partly explains why the seemingly rudimentary gaol plan, its unprocessed materiality, and (perhaps deficient) craftsmanship, blinded historians to its architectural lineage, such that, when faced with representations of Okiato gaol, they saw a building - not architecture.

Pascoe’s history of architecture supports the idea of an organic development of prison architecture in New Zealand, but it also effected the conventional distancing from NSW’s history as a penal colony fundamental to New Zealand identity in its looking to England for architectural origins. Yet British criminality is just as fundamental to New Zealand’s colonisation as it is to Australia’s. While NSW was colonised because Britain wanted a place to exile criminals, New Zealand‘s colonisation by Britain was influenced by their citizens here behaving criminally. NSW’s expansion to include New Zealand has particular importance in relation to this given the increasing geographic reach of NSW’s system of law and order, following the adoption of Bigge’s policy of “territorial sprawl” and its potential architectural impacts.

Finally, the understanding of Okiato gaol as originating from the NSW Colonial Architect’s office might also raise questions about the status of “building” and “architecture” in a colonial context. Such questions have already been well-traversed in relation to racism and indigenous architecture, and that is not the area examined here. We can say now that Okiato gaol was architecturally designed, even if its author was deemed to be a bad architect, querying the frequent conflation in architectural histories of authorship and quality, where good architects produce good architecture, often bypassing sustained attention on the quality of building design itself. As the product of the NSW Colonial Architect’s office, the gaol is part of a system reliant on maintaining a distinction between the ideas of building and architecture, one vital to safeguard (in order to justify) the profession of architecture. The primitive hut traditionally stands at that point of adjudication, because it is the promise of the architecture it precedes.

What happens then when, rather than appearing to be architecture, architecture mimics building? In stating this I am conscious of Homi Bhabha’s formulation of the colonial problem of mimicry as a “difference that is almost the same, but not quite.”Footnote120 However, while Bhabha identified the colonial problem of mimicry as when “the mimic is fuelled by the coloniser who seeks ‘a reformed, recognizable Other,’”Footnote121 the Okiato gaol’s mimicry is unabashedly directed towards the precursor (the log cabin), not the “highly civilised” architecture (the prison). This arises in New Zealand because, unlike at Goulburn Plains, Okiato gaol lacks its juxtaposition. Despite being a NSW Colonial Architect design, the Okiato gaol fails to present itself as architecture, because it leaves aside the relationship that demonstrates its Western cultural competence. Rather than a “primitive hut” offering the promise of architecture, the Okiato gaol contests the conventionally-assumed direction of Western colonial processes. When a presumed primitive hut is revealed to be architecture then perhaps a critical lynchpin of architecture collapses. It is this quandary that John Stacpoole, rather than Ambrose Hallen, left us when he described the Okiato gaol as “little more than [a] shack,” opening up the possibility that it might be good or bad architecture as well as simply a building.

Post Script

The Okiato gaol is no longer standing. After 10 months, in February 1841, Hobson left Okiato and established a new capital at Tāmaki Makaurau (Auckland), moving permanently on 13 March.Footnote122 The move to Auckland followed a Royal Charter creating New Zealand as a colony in November 1840, a change which came into effect in New Zealand in May 1841.Footnote123 As a consequence, Okiato was no longer known as “Russell.” Instead, official roles moved to Kororāreka, and Kororāreka was increasingly referred to as “Russell.”Footnote124

A year after the colonial government administration moved to Tāmaki Makaurau, on 1 May 1842, the old government house at Okiato was burnt down.Footnote125 Sale writes that “the only things left of the brief Bay of Islands capital were some of Mrs Hobson’s rose bushes and the name Russell.” however, continued reference to the gaol at Okiato in government records suggests it operated until at least 1844.Footnote126 During the Northern War (1845–46), Okiato was proposed by Governor Robert FitzRoy as a possible place for the colonial military forces where “strong fortifications [would be built] from which operations in the interior could be carried out.”Footnote127 Both Hill and Wards referred to British troops being established at Okiato in September 1845, with Hill describing this move as a retreat and Wards stating that Colonel Despard saw the strategic advantage of Okiato as preventing “[Te Ruki] Kawiti’s communications with the sea and the all-important fishing grounds.”Footnote128 Despite this Kawiti’s design of Ruapekapeka and other pā confounded British victory in the north. The government sold Okiato in 1891 to G.E. Schmidt.Footnote129

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Peter Wood for comments on an early draft of this paper.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. Jean Dunn, “An Enquiry into the New Zealand Prison System. 1840–80” MA thesis., Victoria University, 1948.

2. P.K. Mayhew, The Penal Architecture of New Zealand 1840–1924 (Wellington: Department of Justice, 1959), preface, 2.

3. Greg Newbold, The Problem of Prisons: Corrections Reform in New Zealand since 1840 (Wellington: Dunmore Press, 2007), 23.

4. David J. Rothman, The Discovery of the Asylum: Social Order and Disorder in the New Republic (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1971), 55–56; Adam Jay Hirsch, The Rise of the Penitentiary: Prisons and Punishment in Early America (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992), 9.

5. Robin Evans, The Fabrication of Virtue: English Prison Architecture, 1750–1840 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982), 16.

6. For example, Hodgson describes 1840 Wellington as “a townscape of scattered huts and makeshift buildings” and notes that “settlers hoped that permanent materials such as stone might be used for churches in New Zealand” (Terence Hodgson, Looking at the Architecture of New Zealand (Wellington: Grantham House Publishing, 1990), 2). Stacpoole likewise states that courthouses, churches and commercial premises in the colonies were “usually smaller in scale and less formal in planning than similar buildings in the home country; very frequently there was an amateurishness about their design, the work of skilled but not necessarily expert hands; and where the designer was indeed expert he had probably to use available materials or available methods of construction, different from the materials and methods he would have employed in more highly developed countries.” John Stacpoole, Colonial Architecture in New Zealand (Wellington: A.H. & A.W. Reed, 1976), 9.

7. Note that the Treaty of Waitangi conventionally refers to the English text which is not a direct translation of Te Tiriti o Waitangi, which most people, including William Hobson, signed.

8. The English version (The Treaty) referred to sovereignty.

9. “rangatiratanga” is a noun meaning “chieftainship, right to exercise authority, chiefly automony, chiefly authority, ownership, leadership of a social group, domain of the rangatira, noble birth, attributes of a chief.” Te Aka: Māori Dictionary https://www.maoridictionary.co.nz/

10. James Belich, Making Peoples: A History of the New Zealanders: From Polynesian Settlement to the End of the Nineteenth Century (Auckland: Penguin Books (New Zealand), 1996), 180–181; Ned Fletcher, The English Text of the Treaty of Waitangi (Wellington: Bridget Williams Books, 2022), 529.

11. Fletcher, The English Text of the Treaty of Waitangi, 46.

12. Ruth M. Ross, New Zealand’s First Xapital (Wellington Department of Internal Affairs New Zealand, 1946), 9. Ross dates the letter patent extending NSW as 15 June 1939.

13. Kenneth A. Simpson, “H29 Hobson, William 1792–1842.” In The Oxford History of New Zealand edited by W.H. Oliver and B.R. Williams (Oxford: Clarendon Press; Auckland: Oxford University Press, 1988; first published 1981),197; Ross, New Zealand’s First Capital, 10.

14. Claudia Orange, The Treaty of Waitangi (Wellington: Bridget Williams Books Ltd, 2011), 41.

15. Proclamation quoted, Fletcher, The English Text of the Treaty of Waitangi, 302; Belich, Making Peoples, 180. Hobson left Sydney for New Zealand on 19 January 1840. The proclamation followed Queen Victoria’s letters patent in June 1839. Ross, New Zealand’s First Capital, 9.

16. Philippa Mein Smith, A Concise History of New Zealand (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 45; Orange, The Treaty of Waitangi, 42; Ross, New Zealand’s First Capital, 9.

17. Keith Sinclair, A History of New Zealand (Middlesex: Penguin Books, 1960), 66.

18. Raewyn Dalziel, “The Politics of Settlement.” In The Oxford History of New Zealand, edited by W.H. Oliver and B.R. Williams (Oxford: Clarendon Press; Auckland: Oxford University Press, 1988), 87; Barrie Dyster, “Public Employment and Assignment to Private Masters, 1788–1821,” Convict Workers: Reinterpreting Australia’s past, ed. Stephen Nicholas (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988), 135–37.

19. Hodgson, Looking at the Architecture of New Zealand, [0]; Jeremy Salmond, Old New Zealand Houses: 1800–1940 (Auckland: Reed Methuen, 1986), 49–50; Stacpoole, Colonial Architecture, 10–11, 19.

20. Salmond, Old New Zealand Houses, 23; Peter Shaw, New Zealand Architecture: From Polynesian Beginnings to 1990 (Auckland: Hodder & Stoughton, 1991), 17; Stacpoole, Colonial Architecture, 19.

21. Stacpoole, Colonial Architecture, 13, 18.

22. Salmond, Old New Zealand Houses, 80.

23. Salmond, Old New Zealand Houses, 21, 27; Stacpoole, Colonial Architecture, 18; Deidre Brown, “Te Pahi’s Whare: The first European house in New Zealand,” Fabulation: 20th Annual Conference of the Society of Architectural Historians Australia and New Zealand, eds. Stuart King, Anuradha Chatterjee and Stephen Loo (Launceston, Australia: University of Tasmania, 5–8 July 2012), 164–186.

24. Shaw, New Zealand Architecture, 18; Martin McLean, “Science and Research Internal Report No. 76: ‘The Garden of New Zealand:’ A History of the Waitangi Treaty House and Grounds from Pre-European Time to the Present,” (Wellington: Department of Conservation, 1990), 28.

25. Orange, The Treaty of Waitangi, 92.

26. Greg Newbold, The Problem of Prisons, 22–23.

27. Dalziel, “The Politics of Settlement,” 88; Ross, New Zealand’s First Capital, 10, 20, 22.

28. John Stacpoole, William Mason: The First New Zealand Architect (Auckland: Auckland University Press, 1971), 24.

29. Mathew quoted, Stacpoole, William Mason, 25; A.H. Reed, Historic Northland (Wellington: A.H. & A.W. Reed, 1968), 27; Jeanette Richardson, A Capital Story: An Account of New Zealand’s First Seat of Government at Okiato in the Bay of Islands (Whangarei: Calders Design & Print Co., 2012), 38.

30. Melina Goddard, Okiato: The Site of New Zealand’s First Capital (Bay of Islands: Bay of Islands Area Office, Department of Conservation/Te Papa Atawhai, 2010), 2; Ross, New Zealand’s First Capital, 38.

31. E.V. Sale, Historic Trails of the Far North (Wellington: A.H. & A.W. Reed Ltd, 1981), 12; Patricia Adams and R.M. Ross, “Hokianga Homes of Missionary, Magistrate, and Pakeha Maori,” in Historic Buildings of New Zealand: North Island (Auckland: Cassell New Zealand, 1979), 23; Reed, Historic Northland, 27; Ross, New Zealand’s First Capital, 37; Goddard, Okiato, 2.

32. Mathew quoted, Stacpoole, William Mason, 25. Also Richardson, A Capital Story, 34–36, 41; Ross, New Zealand’s First Capital, 22, 28–33, 42.

33. Ross, New Zealand’s First Capital, 38.

34. Stacpoole, William Mason, 25; Reed, Historic Northland, 27; Ross, New Zealand’s First Capital, 39–41, 50; Richardson, A Capital Story, 45; Sale, Historic Trails of the Far North, 12; Reed, Historic Northland, 27.

35. Ross, New Zealand’s First Capital, 48; Richardson, A Capital Story, 61.

36. “Gaol at Okiato,” The Colonist (Sydney, NSW), 9 July 1840, 3; ” [untitled] We beg most respectfully,” New Zealand Advertiser and Bay of Islands, 3 December 1840, 3; “Blue Book of Statistics: Colony of New Zealand” (1840), 50–51, held Archives New Zealand, Wellington, Ref: IA-12-01; R112764953.

37. Stacpoole, Colonial Architecture, 19; Ross, New Zealand’s First Capital, 47.

38. Goddard, “Okiato,” 3; Ross, New Zealand’s First Capital, 47.

39. Dunn, “An Enquiry into the New Zealand Prison System. 1840–80,” 2; P. K. Mayhew, The Penal Architecture of New Zealand 1840–1924, 3.

40. The Blue Books reported on various aspects of the colony, copies of which being sent to the Colonial Office in London. Blue Book of Statistics: Colony of New Zealand (1841), 197, held Archives New Zealand, Wellington, Ref: IA 12–02; Blue Book of Statistics: Colony of New Zealand (1843), 215, held Archives New Zealand, Wellington, Ref: IA 12–05.

41. Raupō is also known as bullrush or typha orientalis; toetoe is also known as plumed tussock or Austroderia splendens; sometimes misspelt as toitoi.

42. Stacpoole, William Mason, 26, emphasis added. Hill notes that the Mounted Police main barracks were established at Okiato. Richardson S. Hill, Policing the Colonial Frontier (Wellington, New Zealand: Historical Publications Branch, Department of Internal Affairs; V.R. Ward Government Printer, 1986), 128. “Old Russell” is sometimes used for Okiato, to distinguish it from Kororāreka, which is currently known as Russell.

43. Stacpoole, William Mason, 26, 193–94

44. “Gaol at Okiato,” 3.

45. Blue Book of Statistics: Colony of New Zealand (1842), 105, held National Archives, Kew, England, Ref: CO 213–28 1842; Blue Books of Statistics (1843), 232, IA 12–05; Blue Books of Statistics (1844), 211, IA 12–06.

46. For example, door swings can impact on perceptions of whether a wall continues in a straight line across two rooms, and a fireplace could also affect measurements along a wall and perceptions of where walls connect.

47. Blue Books of Statistics (1841), 197, IA 12–02.

48. Blue Books of Statistics (1842), 9, CO 213–28.

49. Salmond, Old New Zealand Houses, 67–68.

50. Goddard, “Okiato,” 13, .

51. McLean, “Science and Research Internal Report No. 76,” 28.

52. Stacpoole, William Mason, 14–16.

53. ibid., 21.

54. Morton Herman, The Early Australian Architects and Their Work (Sydney: Angus and Robertson, 1954), 113.

55. Stacpoole, William Mason, 22–23; also Herman, The Early Australian Architects, 199.

56. Stacpoole, William Mason, 22–23.

57. Richardson makes a similar connection when he states that Mason’s Auckland Court House design “owed a debt to Lewis’ court houses in New South Wales, especially the Darlinghurst Court House (1835–44), construction of part of which Mason had superintended.” Peter Richardson, “Building the Dominion: Government Architecture in New Zealand 1840–1922.” (PhD diss., University of Canterbury (Christchurch), 1997), 62.

58. Belich, Making Peoples, 134; Angela Middleton, Pēwhairangi: Bay of Islands Missions and Maori 1814 to 1845 (Dunedin: Otago University Press, 2014), 36.

59. Michael King, The Penguin History of New Zealand (Auckland: Penguin Books, 2003), 140; Smith, A Concise History of New Zealand, 31; Belich, Making Peoples, 135.

60. King, The Penguin History of New Zealand, 140; Middleton, Pēwhairangi, 24.

61. Smith, A Concise History of New Zealand, 31–32; Middleton, Pēwhairangi, 24, 88; Belich, Making Peoples, 135.

62. James Semple Kerr, Design for Convicts (Sydney: Library of Australian History, 1984), 67.

63. Kerr, Design for Convicts, 21–22. Marsden not only supervised the building of the Parramatta Gaol, he also proposed a design for the Parramatta Female Factory, based on the Woollen Manufactories in Leeds, following a request from Governor Macquarie in December 1817. Kerr states that Macquarie’s architect, Francis Greenway, had “adopted ‘the width of the rooms, as proposed in … [Marsden’s] Plan, and the general dimensions of them.’” Kerr, Design for Convicts, 42, 43.

64. James Semple Kerr, Out of Sight, Out of Mind: Australia’s Places of Confinement, 1788–1988 (Sydney: S.H Ervin Gallery, 1988), 22.

65. Kerr, Out of Sight, Out of Mind, 22.

66. ibid., 22–23.

67. ibid., 23, fig 16.

68. Kerr, Design for Convicts, 20.

69. Stephen Nicholas, “The Care and Feeding of Convicts” In Convict Workers: Reinterpreting Australia’s Past, edited by Stephen Nicholas (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988), 189; Dyster, “Public Employment and Assignment to Private Masters,” 129; Herman, The Early Australian Architects, 44, 60; Hughes put this slightly differently: “To its settlers, New South Wales was not a jail but a free community with rather a large preponderance of prisoners in it.” Robert Hughes, The Fatal Shore: The Epic of Australia’s Founding (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1987), 288, 346.

70. Hughes, The Fatal Shore, 426; Dyster, “Public Employment and Assignment to Private Masters,” 129, 135–37.

71. Kerr, Design for Convicts, 58, 81; Dyster, “Public Employment and Assignment to Private Masters,” 136, 138.

72. Nicholas, “The Care and Feeding of Convicts,” 190; Kerr, Out of Sight, Out of Mind, 27; Kerr, Design for Convicts, 61; Dyster, “Public Employment and Assignment to Private Masters,” 138.

73. Kerr, Design for Convicts, 83; Kerr, Out of Sight, Out of Mind, 22.

74. Kerr, Out of Sight, Out of Mind, 22.

75. ibid., 27.

76. ibid., 27.

77. Herman, The Early Australian Architects, 199; Kerr, Design for Convicts, 83–84.

78. Herman, The Early Australian Architects, 199.

79. Kerr, Design for Convicts, 83–84.

80. For example, Kerr, Design for Convicts, 83, Fig 131 replicates Hallen’s 1832 courthouse stockade design as if it is Lewis’ referencing Lewis’ Plan of Gaols as his source.

81. Kerr, Out of Sight, Out of Mind, 27.

82. William Whyte, “How do Buildings Mean? Some Issues of Interpretation in the History of Architecture,” History and Theory 45 (May 2006) 154, 177.

83. Salmond, Old New Zealand Houses, 81.

84. Goulburn Plains gaol and courthouse (1831–32) 1–2, held State Library of New South Wales Ref: DLADD 203; IR Number: YRIZNNIn.

85. Herman, The Early Australian Architects, 117.

86. Herman, The Early Australian Architects, 117, 156; Kerr, Design for Convicts, 103. J.M. Freeland, Architecture in Australia: A History (Melbourne: F.W. Cheshire, 1968), doesn’t even mention Hallen.

87. Herman, The Early Australian Architects, 116; “Government Architects - New South Wales,” Pillars of a Nation, accessed November 29, 2022, http://www.pillarsofanation.com.au/architects1.html

88. Kerr, Design for Convicts, 103.

89. Herman, The Early Australian Architects, 200, 206; Freeland, Architecture in Australia, 95.

90. Herman, The Early Australian Architects, 205.

91. Freeland, Architecture in Australia, 50.

92. ibid., 50.

93. ibid., 50, 95.

94. Herman, The Early Australian Architects, 205.

95. ibid., 115.

96. ibid., 179.

97. ibid., 116.

98. Salmond, Old New Zealand Houses, 27; McLean, “Science and Research Internal Report No. 76,” 16, 19, Plate 2; William Toomath, Built in New Zealand: The Houses We Live In (Auckland: HarperCollins, 1996), 20; Herman further writes that: “Busby, too, was not happy about the plan and later had Ambrose Hallen alter it.” Herman, The Early Australian Architects, 172.

99. Stacpoole, Colonial Architecture, 14.

100. Toomath, Built in New Zealand, 19–20.

101. Will Grave Verge, “John Verge: An Early Architect of the 1830’s,” Royal Australian Historical Society: Journal and Proceedings 40, no. I (1954) 33–34.

102. Herman, The Early Australian Architects, 172.

103. ibid., 170–171.

104. Freeland, Architecture in Australia, 81, emphasis added.

105. Freeland, Architecture in Australia, 81–82.

106. Herman, “The Architecture and the Architects,” 37.

107. McLean, “Science and Research Internal Report No. 76,” 18; Herman, The Early Australian Architects, 116; Toomath, Built in New Zealand, 20.

108. McLean, “Science and Research Internal Report No. 76,” 18, 27; Hodgson, Looking at the Architecture of New Zealand, [1]; Shaw, New Zealand Architecture, 18.

109. Freeland, Architecture in Australia, 73.

110. ibid., 73.

111. ibid., 73.

112. Rachel Barrowman, “History and Romance: The Making of the Centennial Historical Surveys,” Creating a National Spirit:Ccelebrating New Zealand’s Centennial, ed. William Renwick (Wellington: Victoria University Press, 2004), 165.

113. Barrowman, “History and Romance,” 166.

114. Paul Pascoe, “Public Buildings,” Making New Zealand 2, no. 21 (1940), 2.

115. Pascoe, “Public Buildings,” 2.

116. Pascoe, “Public Buildings,” 8.

117. Pascoe, “Public Buildings,” 2.

118. Pascoe, “Public Buildings,” 2.

119. Mark Wigley, “Cabin Fever,” Perspecta 30 (January 1999), 123.

120. Homi K. Bhabha, The Location of Culture (London: Routledge, 1998), 86.

121. Bhabha, The Location of Culture, 86.

122. Middleton, Pēwhairangi, 232; Sale, Historic Trails of the Far North, 12; Goddard, “Okiato,” 4.

123. Orange, The Treaty of Waitangi, 92.

124. Sale, Historic Trails of the Far North, 12–13; Goddard, “Okiato,” 4.

125. Reed, Historic Northland, 27; Adams and Ross, “Hokianga Homes of Missionary, Magistrate, and Pakeha Maori,” 23; Goddard, “Okiato,” 2. When the fire occurred, the northern Police Magistracy moved from Okiato to Kororāreka. Hill, Policing the Colonial Frontier, 180.

126. Sale, Historic Trails of the Far North, 12–13; The last Blue Book to list the Okiato Gaol is in 1844. Blue Book of Statistics: Colony of New Zealand (1844), 188, 215, held Archives New Zealand, Wellington, Ref: IA 12–06.

127. Ian Wards, The Shadow of the Land: A Study of British Policy and Racial Conflict in New Zealand 1832–1852 (Wellington: A.R. Shearer, Government Printer; Historical Publications Branch, Department of Internal Affairs, 1968), 186.

128. Hill, Policing the Colonial Frontier, 190; Wards, The Shadow of the Land, 189.

129. Goddard, “Okiato,” 4.