?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Despite the well-documented COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on public health, it is crucial to acknowledge the broader societal costs of the pandemic and the resulting pandemic-related restrictions. In particular, this research highlights the impact of COVID-19 on two forms of crime: domestic violence and child abuse. This study aims to evaluate the prolonged effect of COVID-19 on arrests for domestic violence and child abuse in Hong Kong by employing a single-group interrupted time-series analysis of ten-year monthly arrest data obtained from the Hong Kong Police Review. Consistent with previous studies, this study found that there was no immediate effect of COVID-19 on arrests for domestic violence and child abuse, but there was subsequently an increasing trend of domestic violence and child abuse during the COVID-19 pandemic. The increased trend of family violence during the COVID-19 pandemic may be explained by the accumulated strains and changes in routine activities associated with the pandemic and the anti-pandemic measures implemented by the government. Limitations and implications for future studies are discussed.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has imposed unprecedented challenges on the public health system and has far-ranging impacts on individual lifestyles. To curb the spread of the virus, governments worldwide implemented public health measures, including social distancing and stay-at-home, aimed at limiting face-to-face interactions. While these measures have been effective in slowing down the transmission of the virus, concerns have arisen regarding their potential repercussions, often unintended, for families and children. Specifically, there is a concern that these anti-pandemic measures inadvertently exacerbate the vulnerability of victims of domestic violence and child maltreatment. According to the routine activity perspective, home confinement and limited access to social services can increase the risk of family violence due to the increased proximity between domestic violence perpetrators and victims within residential settings (Krishnakumar & Verma, Citation2021). Additionally, school closures have isolated students at home, making them more vulnerable to maltreatment or abuse by their caregivers (e.g., parents, relatives, and domestic helpers) (Bucerius et al., Citation2021). Accordingly, children may have become one of the most vulnerable populations during the pandemic, as they not only have a higher risk of experiencing child abuse but also witnessing violent confrontations among family members in their homes. The victims of family violence may endure severe psychological trauma and suicidal intentions, while such adverse childhood experiences can further impede children’s psychological development and contribute to delinquency later in life (Herzog & Schmahl, Citation2018; Hughes et al., Citation2017).

Despite the adverse consequences, there is a relative scarcity of empirical research on the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on both domestic violence and child abuse in Chinese societies. Moreover, the associations between the COVID-19 pandemic, domestic violence, and child abuse have yielded mixed results in Western societies (Demir & Park, Citation2022; Piquero et al., Citation2021). In addition, there have been limited studies that have employed interrupted time series analysis to examine changes in child abuse amid the pandemic in Chinese societies, particularly within the unique Chinese social context where the Chinese government adopted the ‘zero covid' strategy to minimize the number of positive cases as close to zero as possible.

This study chose Hong Kong, a special administrative region of the People’s Republic of China, located in southern China, as the research site for several key reasons. First, Hong Kong is at risk of importing COVID-19, given its shared border and high infrastructural and social connectivity with China (Chan et al., Citation2021a). In addition, Hong Kong was one of the first cities to implement social distancing measures, some of which (such as school closures) remain effective over three years after the pandemic outbreak (Ioannidis et al., Citation2023; Tso et al., Citation2022). Second, the Hong Kong government adopted a ‘dynamic zero COVID' approach, characterized by mandatory testing and strict social distancing measures, in order to prevent community transmission of COVID-19. This approach differs from the ‘live with COVID' approach adopted by most Western countries (Lau et al., Citation2022; Matus et al., Citation2023). For instance, Hong Kong enforced one of the most rigorous and lengthy quarantine measures, requiring individuals to undergo a 21-day quarantine period at designated quarantine facilities or hotels (Fong et al., Citation2023). However, such stringent containment measures may potentially exacerbate family conflicts due to the substantial shift in routine activities from the public to the private sphere (Krishnakumar & Verma, Citation2021; Zhang, Citation2022).

Third, it is important to note that Hong Kong has not implemented a complete city lockdown since the beginning of the pandemic. Nevertheless, the prolonged and stringent containment policies have potentially resulted in a mental health emergency for Hong Kong citizens. Specifically, there has been an alarming increase in mental health symptoms such as depression and anxiety, particularly among parents who have experienced a long period of social distancing, severe disruption of daily life, and job insecurity due to the anti-pandemic measures (Choi et al., Citation2020; Tso et al., Citation2022; Zhao et al., Citation2020). According to Agnew’s general strain theory, these pandemic-related stressors may contribute to negative emotions that can lead to delinquent coping strategies, such as crime and deviance, as a means to alleviate the strain-induced negative affections (Agnew, Citation1992). Finally, although previous studies have employed short-term time-series analyses to examine the relationship between the COVID-19 pandemic and domestic violence, the findings have been somewhat mixed (Campedelli et al., Citation2020; Piquero et al., Citation2021; Leslie & Wilson, Citation2020). Moreover, evidence in Asian societies, including Hong Kong, has been scarce (Seposo et al., Citation2023).

These factors highlight the accessibility and reliability of assessing the effect of pandemic-related restrictions on family violence in a non-Western context, particularly focusing on the changes in domestic violence and child abuse cases in Hong Kong. Against this context, the present research aims to contribute new empirical evidence for COVID-19 and family violence based on the non-Western social context by analyzing how the trends in domestic violence and child abuse evolved before and amid the pandemic with ten-year monthly police arrest data.

Increased risk of family violence during COVID-19

Despite differences in the meaning of violence presented from culture to culture, family violence broadly refers to any acts of violence, threatening behavior, or physical, sexual, or emotional abuse, often between intimate partners or else between family members (Zhang, Citation2022). This type of violence can happen to anyone, regardless of their background, sexuality, age, disability, or gender. Although domestic violence can involve abusers and victims of either gender, the majority of the perpetrators of domestic violence tend to be male and victims to be female. Victims of domestic violence can be affected by a series of abusive behaviors, including physical and non-physical acts, that accumulate over time (Flury et al., Citation2010). Such abusive experiences can prompt prolonged psychological trauma, mental disorders such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, and depression, or even incite self-destructive behavior such as drug abuse or suicide intention (Knight & Hester, Citation2016; Liu et al., Citation2021).

Amid times of crisis, there tends to be a rise in domestic violence incidents, often attributed to economic instability and stressful living conditions. For instance, previous studies have found that the rate of domestic violence rose during the Great Recession in the United States, and experiences during natural disasters such as Hurricane Katrina were associated with an increased likelihood of violent methods of conflict resolution (Harville et al., Citation2011; Schneider et al., Citation2016). Concerning the COVID-19 pandemic, it might not only be a significant physical health concern, but might also become a psychosocial crisis worldwide. That is, economic recession, job insecurity, fear of infection, and prolonged quarantine can incite severe psychological problems such as anxiety and depression or even exacerbate pre-existing disorders (Campbell, Citation2020; Gulati & Kelly, Citation2020; Sediri et al., Citation2020).

In the context of Hong Kong, there may be an elevated risk of family conflicts during COVID-19 compared to Western societies due to its status as one of the most densely populated cities in the world. Even before the pandemic, factors such as limited living spaces, multigenerational households, and the influence of authoritarian parenting ingrained in Chinese culture were positively correlated with a higher risk of family conflicts (Chan et al., Citation2021b). These risks could have been further aggravated during COVID-19 as the pandemic-related restrictions, such as mandatory quarantine, have forced family members to spend extended periods of time together in confined environments. Moreover, alcohol abuse, which is often cited as a risk factor for domestic violence, has been associated with a build-up of stressful events and a lack of social support—both of which may be heightened as a result of COVID-19 (Krishnakumar & Verma, Citation2021). With the dine-in services ban in bars and restaurants, domestic perpetrators who previously engaged in abusive alcohol use tend to consume alcohol at home, potentially increasing the risk of violence for the entire household (Campbell, Citation2020). All these factors suggest an ad-hoc opportunity for the domestic perpetrator to exert further control over the household.

Decreased detection and intervention of family violence during COVID-19

Under normal circumstances, domestic violence victims might be reluctant to seek help from healthcare providers or engage in social service utilization. Amid the pandemic, the situation can worsen further. On the one hand, the closures of schools and social service centers limit the options for victims to seek immediate formal assistance, as the social service infrastructure might be limited or operating remotely (Fawole et al., Citation2021). Access to temporary housing shelter, and other advocacy services might also be constrained due to social distancing and quarantine requirements. On the other hand, the school closures and the shutdown of critical community organizations, coupled with the fear of infection, make it challenging for social workers, victim-serving professionals, or relatives and friends to detect and report domestic abuse (Humphreys et al., Citation2020; Pereda & Díaz-Faes, Citation2020). Domestic violence perpetrators often use isolation as a means of control or to prevent the disclosure of abuse, and the conditions imposed by the pandemic further exacerbate the isolation experienced by victims, marginalizing them even more (Campbell, Citation2020; Humphreys et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, the COVID-19 lockdown also limits informal mechanisms of social support through relatives and close friends for help with domestic violence (Fawole et al., Citation2021). Due to the heightened risk and reduced social support, victims of domestic violence may experience increased victimization, as they face significant challenges in leaving their abusers amid the pandemic context. The combination of increased risk and decreased social support creates a difficult situation for victims, making it harder for them to escape abusive relationships during the pandemic.

Current study

Despite the heightened risk factors and the limited interventions for the victims of family violence, empirical research has provided mixed findings for the association between the COVID-19 pandemic, domestic violence, and child abuse (Piquero et al., Citation2021; Balmori De La Miyar et al., Citation2021; Evans et al., Citation2021; Payne et al., Citation2022). Therefore, the association between the COVID-19 pandemic and domestic violence remains vague. Moreover, it is noteworthy that domestic violence extends beyond violence between intimate partners. Children are also at-risk and can be the most vulnerable group affected by domestic violence. Even if they are not directly abused by their parents, they can still experience the impact of domestic violence indirectly by witnessing the violence, observing the aftermath such as their mother’s injuries or broken objects, or witnessing their mother’s emotional distress (Meltzer et al., Citation2009). These traumatic events can have serious adverse effects on children’s well-being, leading to long-term psychological, emotional, and behavioral problems over the course of their lives (Ferrara et al., Citation2021; Forke et al., Citation2019).

It is important to acknowledge that most existing research on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on domestic violence has focused on short-term effects, typically examining a few weeks or months of data following the outbreak or implementation of anti-pandemic measures. Additionally, prior research has suggested that the impact of COVID-19 on domestic violence may vary across geographical settings and cultures (Demir & Park, Citation2022). Hence, it is particularly crucial to investigate whether changes in trends of domestic violence and child abuse are consistent or divergent across different cultural contexts. However, research specifically investigating the impact of COVID-19 on both domestic violence and child abuse in Chinese societies has been limited. To address this gap, this study employs an interrupted time series analysis using ten years of monthly police arrest data to examine the extended effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on domestic violence and child abuse in Hong Kong. This study hypothesizes the following:

H1.1: There are statistically significant differences in the number of domestic violence arrests between January 2013 and December 2022, before and after the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic.

H1.2: There are statistically significant differences in the number of child abuse arrests between January 2013 and December 2022, before and after the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic.

H2.1: There is a statistically significant increasing trend in the number of domestic violence arrests after January 2020, the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic.

H2.2: There is a statistically significant increasing trend in the number of child abuse arrests after January 2020, the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Method

Data sources

Previous studies have acknowledged the limitations of relying on official crime data, but it should be noted that there is a lack of self-reported victimization data like the US National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS) in Hong Kong. In addition, the data on calls for service for domestic violence and child abuse is not accessible to the general public. As a result, this analysis has to rely solely on the arrest data proffered by the Hong Kong Police Force, which is publicly available on the Hong Kong Police Force Website. Nonetheless, the Hong Kong Police Force statistics have been the most widely used crime data for crime studies in Hong Kong (Chen & Zhong, Citation2021). One of the benefits of the Hong Kong Police Force statistics is the availability of trend data (monthly and annual data) for overall and specific crimes over a period of time (Cheung & Cheung, Citation2013). In addition, there are no prohibitions on the usage of official crime data for research purposes, and all data have been anonymized to protect the privacy of individuals; therefore, ethical concerns are not an issue for using official crime data in our analysis. On the other hand, the first confirmed case of COVID-19 in Hong Kong was reported on January 23, 2020. To account for the prolonged effect of COVID-19 on domestic violence and child abuse and to rule out the influence of historical effects on the outcome, ten years (from 2013 to 2022) of monthly arrest data was analyzed. In this article, the unit of analysis is the monthly count (N = 120) of the number of arrests for domestic violence and child abuse. The reason for using ‘count' data rather than ‘rate' data is that there was only a 0.87% decrease in the population in Hong Kong, indicating that the population is stable over time (Census and Statistics Department, Citation2021).

Measurements

There are two dependent variables in this study: monthly counts of domestic violence arrests and child abuse arrests. In this study, domestic violence refers to any acts of violence that involve threatening behavior or physical, sexual, or emotional abuse between adults who are or have been intimate partners (Department of Justice, Citation2023). Similarly, child abuse refers to ‘any act of commission or omission that endangers or impairs a child’s physical or psychological health and development of an individual under the age of 18' (Social Welfare Department, Citation2020). Domestic violence arrests include arrests for physical violence, sexual violence, psychological abuse, and multiple abuse on intimate partners. Similarly, child abuse arrests include arrests for physical abuse, sexual abuse, psychological abuse, and multiple abuse of an individual under the age of 18. The only difference is that child abuse arrests include any act of neglect committed by the caregivers. Each dependent variable was measured by the number of monthly domestic violence arrests and child abuse arrests during each month between January 2013 through December 2022.

The independent variable in this study is the COVID-19 pandemic. COVID-19 is represented as a dummy variable, where 0 indicates the pre-COVID-19 period, and 1 represents the during COVID-19 period. Although the Hong Kong government did not implement any pandemic-related restrictions after the first confirmed positive case on 23 January 2020, the citizens of Hong Kong have been very attentive to personal preventive measures in the absence of mandatory anti-pandemic measures. For instance, an online survey with 1,715 samples revealed that 70.1% of respondents reported avoiding going out, and 64.3% of them minimized social activities and stayed at home during leisure time (Chan et al., Citation2021a). Considering the precautionary behaviors adopted by the general public, it was evident that there was a significant change in the routine activities of the citizens in Hong Kong soon after the pandemic outbreak. Consequently, Month 86 of our data, January 2020, was considered the ‘intervention' point or beginning of the treatment of the following interrupted time-series analysis. As a result, the monthly data was segmented into pre-intervention period (January 2013 to December 2019) and the post-intervention period (January 2020 to December 2022).

To avoid potential confounders undermining the accuracy of the research findings, four variables were controlled in this study: the unemployment rate, bar restrictions, school closures, and working-from-home arrangements of integrated family social services centers. Although there has been a well-established predictive role of unemployment and alcohol consumption in domestic violence and child abuse, the adverse effects can be further aggravated during the COVID-19 pandemic. On the one hand, the COVID-19 pandemic and containment policies have been substantially disrupting commercial activities in societies, contributing to the economic downturn in Hong Kong, which led to the highest unemployment rate and economic stress amid the pandemic years (Lau et al., Citation2021). On the other hand, social distancing measures such as restrictions on group members and the opening of bars can alter individuals’ alcohol consumption behavior from public to private settings (Hartley & Jarvis, Citation2020). Additionally, bar closures may lead to alcohol withdrawal, and alcohol withdrawal syndrome, such as impulsivity, can be conducive to domestic violence (Krishnakumar & Verma, Citation2021). In addition, as noted, school closures and working-from-home arrangements of integrated family social services centers can lead to increased exposure to domestic violence perpetrators or child abusers and decreased intervention amid the pandemic. Hence, these two variables were controlled in this study.

In this study, monthly unemployment rates from 2013 to 2022 were extracted from the Census and Statistics Department website, which is publicly accessible. As it was skewed, a log transformation was performed on the unemployment rate data. Bar restrictions, school closures, and working-from-home arrangements of integrated family social services centers were measured as a binary variable (0 = no; 1 = yes). A coding of 1 was used for the period after the Hong Kong government officially announced restrictions on bar operations, school closures, and working-from-home arrangements for the integrated family social services centers, and a code of 0 was used when the government retracted such restrictions.

Statistical analyses

The data analysis was employed in three steps. First, descriptive statistics such as the mean and standard deviation of domestic violence and child abuse arrests were presented. Second, an independent samples t-test was conducted to analyze the differences in the mean counts of domestic violence and child abuse arrests before and during COVID-19. Finally, this study employed a single-group interrupted time-series analysis (ITSA) to examine the impact of COVID-19 on domestic violence and child abuse arrests. ITSA is a quasi-experimental research design commonly used to assess the effects of a policy, measure, or intervention by comparing the outcomes of the pre—and post-intervention periods (Demir & Park, Citation2022; Linden, Citation2015, Citation2017, Citation2018). In this study, the single-group ITSA approach as described by Linden and colleagues was chosen over the commonly used autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) models because the latter can produce biased results if model assumptions are violated. Linden’s approach is considered reliable and straightforward to apply (Linden, Citation2015). The intervention in this study was defined as the month of the first confirmed positive COVID-19 case, January 2020. The itsa command in STATA 15.0 was used for data analysis, and the model was defined accordingly:

Where Yd refers to domestic violence arrests and Yc refers to child abuse arrests, Tt represents the time since the start of the study, Xt is a dummy variable representing the intervention (pre-COVID-19 = 0, otherwise 1), and XtTt is an interaction term (Linden, Citation2015). As this study is a single-group study, β0 represents the intercept or initial level of the outcome variable. β1 indicates the slope or trend of the outcome variable before the intervention is introduced. β2 reflects the immediate change in the level of the outcome variable after the intervention is introduced (compared to the counterfactual). β3 indicates the difference between the pre-intervention and post-intervention slopes of the outcome variable. β4 lg(U) refers to the logged unemployment rate, and β5, β6, and β7 are the binary variables representing bar restrictions, school closures, and working-from-home arrangements of integrated family social services centers. Therefore, a significant p-value in β2 indicates an immediate treatment effect of the COVID-19 pandemic, and a significant p-value in β3 indicates the continuous effects of COVID-19 on domestic violence and child abuse arrests over time. In such a way, this analysis enables researchers to investigate whether the rise or fall in domestic violence and child abuse is a short-term or continuous change, at least based on the timeframe covered by the available data.

Results

presents the results of independent sample t-tests and descriptive statistics for the two dependent variables. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the Hong Kong police made about 124 arrests (M = 124.4) for domestic violence and 76 arrests (M = 76.4) for child abuse each month. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Hong Kong police made about 96 arrests (M = 96.3) for domestic violence and 90 arrests (M = 89.8) for child abuse each month. Overall, from January 2013 through December 2022, the average number of domestic violence Hong Kong police made about 116 (M = 115.95) arrests for domestic violence, ranging from 57 to 194 arrests each month. In addition, the Hong Kong police made about 80 arrests (M = 80.45) for child abuse, ranging from 34 to 148 arrests each month. Notably, the independent samples t-tests indicated statistically significant decreases in arrests for domestic violence (Mean diff = 28.1, p = .00) during the COVID-19 period compared to the pre-COVID-19 pandemic period. In contrast, arrests for child abuse (Mean diff = 13.4, p = .00) significantly increased during COVID-19. Moreover, the effect size for the difference in means of domestic violence arrests during COVID-19 (M = 96.25, SD = 18.215) and pre-COVID-19 (M = 124.39, SD = 25.143) was large, with Cohen’s d = −1.288 (95% CI [−1.819,—0.758]). This indicates that the mean number of domestic violence arrests during COVID-19 was 1.288 standard deviations lower than the mean before COVID-19. Additionally, the effect size for the difference in means of child abuse arrests during COVID-19 (M = 89.81, SD = 33.263) and pre-COVID-19 (M = 76.44, SD = 17.190) was medium, with Cohen’s d = 0.524 (95% CI [0.168, 0.880]). This indicates that the mean number of child abuse arrests during COVID-19 was 0.524 standard deviations higher than the mean before COVID-19.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics and independent samples test.

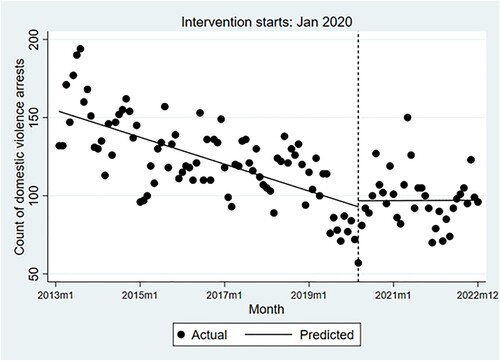

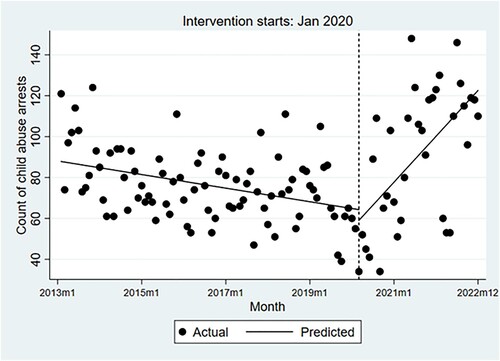

To evaluate the continuous effect of COVID-19 on arrests for domestic violence and child abuse, this study conducted a single-group interrupted time-series analysis using 120 full months of observed data. The monthly data spans from January 2013 to December 2022, with the intervention commencing in the 86th month of the data. The results of the interrupted time-series analysis for the effect of COVID-19 on arrests for domestic violence and child abuse are presented in and , respectively. and visually display the estimated trend lines before and after the intervention. The findings demonstrate a statistically significant decreasing trend in the monthly count of arrests for both domestic violence and child abuse before the COVID-19 pandemic.

Table 2. Interrupted time-series analysis, domestic violence arrests results (N = 120).

Table 3. Interrupted time-series analysis, child abuse arrests results (N = 120).

In addition, a statistically significant increasing trend was observed in the monthly count of arrests for both domestic violence and child abuse amid the COVID-19 pandemic. More specifically, the post-intervention slope estimate indicates a monthly count drop of 0.63 (b = −0.63, p = .00) for arrests for domestic violence and 0.21 (b = −0.21, p = .03) for arrests for child abuse before the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the post-intervention slope estimate demonstrates an increase of 0.35 (b = −0.63 + 0.98 = 0.35) in domestic violence arrests and 1.9 (b = −0.21 + 2.1 = 1.9) in child abuse arrests per month during the COVID-19 pandemic. It is noteworthy, however, that the post-intervention slope estimate for child abuse arrests was greater than that of domestic violence arrests, indicating a larger increase in the monthly count of child abuse compared to domestic violence. However, no statistically significant temporal effect of COVID-19 was found for arrests for domestic violence or child abuse. In addition, logged unemployment (b = 16.2, p = 0.059) was marginally positively associated with domestic violence arrests. Surprisingly, school closure was negatively associated with domestic violence (b = −16.4, p = 0.00) and child abuse arrests (b = −35.0, p = 0.00).

Discussion

Despite the significance of examining the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on public health, it is crucial to acknowledge the broader societal repercussions of the pandemic and the resulting pandemic-related restrictions. This research specifically highlights the impact of COVID-19 on two forms of crime: domestic violence and child abuse. By utilizing a single-group interrupted time-series analysis, this study evaluates the long-term effect of COVID-19 on arrests for domestic violence and child abuse in Hong Kong. Consistent with Hypothesis 2.1 and 2.2, as well as previous studies conducted in Western societies (Bucerius et al., Citation2021; Rebbe et al., Citation2022; Shariati & Guerette, Citation2023), this study found that there was no immediate effect of COVID-19 on the number of arrests for domestic violence and child abuse. However, it identified a later increasing trend of domestic violence and child abuse in Hong Kong during the COVID-19 pandemic. These findings denote that the impact of COVID-19 on domestic violence and child abuse may be a global issue that transcends cultural and societal differences. Consequently, it emphasizes the necessity of a coordinated, global approach to addressing the lingering effects of the pandemic on vulnerable populations, particularly victims of domestic violence and child abuse (Huang et al., Citation2024).

Two major criminological theories, namely Agnew’s (Citation1992) general strain theory (GST) and Cohen and Felson’s (Citation1979) routine activity theory (RAT), can proffer viable explanations for the increasing trend of domestic violence and child abuse amid the pandemic. The general strain theory has been one of the most dominating criminological theories in explaining crime and delinquency. According to Agnew (Citation1992), there are three major crime-producing strains: (1) failure to achieve positively valued goals, (2) removal of positively valued stimuli, and (3) confrontation with negatively valued stimuli. These strains are deemed to trigger negative affections such as anger and depression, which motivate individuals to take corrective actions. When conventional coping mechanisms, such as social support, are insufficient, individuals may resort to criminal or delinquent behavior as an illegitimate coping strategy. In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, multiple layers of stressors can emerge for families, intensifying the risk of domestic violence. Individuals may experience direct pandemic-related stressors, such as fear of infection, social isolation, and indirect stressors, such as increased economic burden due to economic recession (Campbell, Citation2020). These pandemic-related stressors are likely to elicit wide-ranging negative affections such as anger, loneliness, frustration, and depression that may further promote interpersonal conflicts, such as domestic violence (Katz et al., Citation2021).

In contrast to GST, which asserts that crime and deviance result from strainful life events, Cohen and Felson’s (Citation1979) routine activity theory proposes that crime and deviance are influenced by changes in routine activities within society. More specifically, crime is more likely to occur when three key elements converge: motivated offenders, suitable targets, and the absence of capable guardianship. In other words, crimes are viewed as a reflection of the patterns of everyday life rather than an indication of a malfunctioning society (Estévez-Soto, Citation2021). Exceptional events such as hurricanes and earthquakes can have crucial impacts on social structures, and so too can crime opportunities. Shedding light on the COVID-19 crisis, the most noticeable change in routine activities can be attributed to school closures, which disrupted the daily routines of families in society (Shariati & Guerette, Citation2023). According to the routine activity theory, school closures can possibly enhance suitable targets’ exposure to motivated domestic violence and child abusers, with reduced capable guardianship (e.g., social work professionals and teachers in schools).

Surprisingly, the findings in this study reveal a negative association between school closures and arrests for domestic violence and child abuse. This unexpected finding may be attributed to the measurement of the dependent variable of this study, namely the police arrest data of domestic violence and child abuse. That is, school closures may reduce the detection and intervention of child abuse and domestic violence by external guardians, such as social service professionals and teachers (Flury et al., Citation2010; Krishnakumar & Verma, Citation2021). Schools often act as a safety net for children and victims of domestic violence, providing a supportive environment where victims can confide in teachers, counselors, or other staff members trained to recognize signs of abuse. These professionals are trained to recognize signs of abuse and are legally obligated to report suspected child abuse to the appropriate authorities. With schools closed, victims of family violence have limited opportunities to reach out for help or escape abusive situations, and simultaneously there is a decrease in the number of professionals who can observe and report instances of domestic violence, resulting in fewer arrests (Campbell, Citation2020). As a result, the unexpected finding may not imply that school closures serve as a protective factor against child abuse. Rather, it denotes more ad-hoc crime opportunities for the perpetrators of domestic violence and child abuse to isolate and abuse their vulnerable target at home amid the pandemic. Consequently, it is essential to approach the interpretation of the findings with caution when applying Cohen and Felson’s routine activity theory. While the theory offers viable explanations for the consistent rise in certain crime trends (e.g., cybercrime), it may overlook the complex mechanisms of crime reporting, potentially distorting the recorded number of arrests for domestic violence and child abuse. This highlights the need to carefully evaluate the limitations of the theory in understanding the intricate dynamics and reporting biases associated with changes in these specific types of crime trends.

Furthermore, in line with Hypotheses 1.1 and 1.2, there were significant changes in the number of arrests for domestic violence and child abuse in Hong Kong before and after the pandemic outbreak. Nonetheless, it remains unclear why there was a statistically significant decrease in the number of domestic violence arrests. Relying solely on official police arrest data may contribute to the potential underreporting of domestic violence incidents, given that the pandemic restrictions can impede the victims from seeking help from external guardians. In contrast, child abuse cases are less likely to be underreported as they become more visible following school closures and the mandatory reporting system by social work professionals contributes to the identification and reporting of suspicious child abuse cases. In addition, it is also uncertain why the increase in monthly counts of arrests for child abuse overshadowed the arrests for domestic violence in Hong Kong, which provides contrasting evidence with a prior study that suggested a rise in domestic violence reports but a decline in reports of child maltreatment in California (Rebbe et al., Citation2022). These unexpected results might be attributed to cultural differences between Western and Chinese cultures. In general, victims of domestic violence, who are predominantly women, might be hesitant to seek help from the police due to concerns about embarrassment, emotional attachment to the offender, and fear of retaliation (Rebbe et al., Citation2022). However, in Chinese societies, victims of domestic violence may be more reluctant to report due to the fear of ‘losing face' with their families (Su et al., Citation2022). Furthermore, domestic violence is often viewed as a private family matter in Chinese societies, making it less likely for community members or law enforcement agencies to intervene (Sun et al., Citation2022). Also, the fear of infection during the pandemic may have further impeded relatives and friends from intervening or mediating domestic violence incidents. In contrast to domestic violence, Chinese societies are generally less tolerant of child abuse, and intervention from external sources (e.g., neighbors) is therefore more likely to occur (Howe, Citation2005). Finally, mandatory quarantine and school closure may have contributed to parental burnout, resulting in increased parent–child conflicts or abusive practices (Liu et al., Citation2022).

Several limitations should be acknowledged in this study. First, relying on officially recorded crime data is often associated with under-reporting issues. In other words, the findings of the current study can be distorted by the unrevealed ‘dark figures.' Second, this study employed data analysis with police arrest data, which omits other data, such as police calls for services, that can help to depict a more comprehensive picture of the changes in incident reporting during the COVID-19 pandemic. Third, it should be noted that this study focused on the changes in police arrest data for domestic violence and child abuse before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. It remains unclear whether the increasing trend of domestic violence and child abuse will continue in the post-COVID-19 period. More research is needed to examine further the lingering effect of COVID-19 on family violence beyond the pandemic period. Finally, this study employed a single-group interrupted time-series analysis of the effect of COVID-19 on domestic violence and child abuse in Hong Kong. A critical drawback of single-group interrupted time-series analysis is that it is not feasible to ascertain whether factors other than the intervention are accountable for any variations in the time series without a compatible control group. As a result, any causal attribution made may be inaccurate. Nonetheless, this limitation is inevitable as it is practically impossible to find a city not influenced by the COVID-19 pandemic, let alone a city where pandemic-related restrictions remain effective for over three years.

Despite the limitations mentioned, this study offers significant contributions to the emerging body of research on the impact of COVID-19 on the risk of domestic violence and child abuse in Hong Kong. This study represents an initial attempt to explore this issue using an interrupted time series analysis, which differs from most existing studies that have employed cross-sectional population studies and systematic reviews to examine the temporal effects of COVID-19 on family violence (Chan & Fung, Citation2022; Chu et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, this study goes beyond the short-term impact of COVID-19 and considers the prolonged influence of the pandemic on family violence in a non-Western social context. By including pre-COVID data and controlling for potential confounders, it offers valuable insights into the long-term effects of the pandemic on the risk of domestic violence and child abuse (Campedelli et al., Citation2020; Leslie & Wilson, Citation2020; Rebbe et al., Citation2022; Shariati & Guerette, Citation2023). To fully comprehend the long-term impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the risk of domestic violence and its aftermath, researchers and policymakers should monitor the continuous effect of COVID-19 on family violence closely in the post-pandemic period. Regarding policy implications, social workers should reinforce outreach services to families in need and offer family counseling to enhance parent–child and couple relationships (Wong et al., Citation2022). Governments and social work practitioners should also promote resilience training to help parents cope with parenting stressors and prevent parental burnout (Liu et al., Citation2022). Finally, the government should take an active role in educating communities about the signs and reporting channels of child abuse and domestic violence to encourage timely detection and interventions.

Conclusion

This study fills a gap in the existing literature by examining the continuous effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on family violence in a non-Western context like Hong Kong. By extending the analysis beyond the initial weeks or months of the pandemic and utilizing a ten-year monthly police arrest data, this research aims to capture the sustained impact of COVID-19 on family violence, which has often been overlooked in previous studies. Although no significant temporal effects were found for the arrest of domestic violence and child abuse, the results of the ITSA revealed an upward trend in domestic violence and child abuse cases during the pandemic. It is noteworthy that a history of abusive practice can be seen as a significant risk factor for future domestic violence perpetration. Individuals with a history of abusive practices may have learned and internalized aggressive and violent behaviors as effective strategies for controlling and resolving interpersonal relationships. Therefore, initial acts of domestic violence during the pandemic may potentially predict future instances of domestic abuse in the post-pandemic period. Accordingly, further studies are warranted to determine whether the rising trend of family violence persists even in the post-COVID era. If so, the research community should shed more light on investigating repeated cases of domestic violence during and after COVID-19.

Furthermore, this study suggests particular risks in relying on arrest data as the only measure of domestic violence and child abuse. This is because the analysis shows that the anti-pandemic restrictions may impede victims of family violence from seeking assistance. This does not rule out the possibility of a further increase in cases not reported to authorities. Hence, future studies should incorporate both call data and arrest data and the demographic information of the domestic perpetrators to depict a clearer picture of household violence during the pandemic. This study also highlights the need for resilience programs and more accessible social services to facilitate the early identification and intervention of potential domestic violence and child abuse cases in Hong Kong.

Conflict of interest statement

I certify that I have NO affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest (such as honoraria; educational grants; participation in speakers’ bureaus; membership, employment, consultancies, stock ownership, or other equity interest; and expert testimony or patent-licensing arrangements), or non-financial interest (such as personal or professional relationships, affiliations, knowledge or beliefs) in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Agnew, R. (1992). Foundation for a general strain theory of crime and delinquency. Criminology; an Interdisciplinary Journal, 30(1), 47–88. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.1992.tb01093.x

- Bucerius, S. M., Roberts, B. W. R., & Jones, D. J. (2021). The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on domestic violence and child abuse. Journal of Community Safety and Well-Being, 6(2), 75–79. https://doi.org/10.35502/jcswb.204

- Campbell, A. M. (2020). An increasing risk of family violence during the Covid-19 pandemic: Strengthening community collaborations to save lives. Forensic Science International: Reports, 2(100089), 100089. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fsir.2020.100089

- Campedelli, G. M., Favarin, S., Aziani, A., & Piquero, A. R. (2020). Disentangling community-level changes in crime trends during the COVID-19 pandemic in Chicago. Crime Science, 9(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40163-020-00131-8

- Census and Statistics Department. (2021). Thematic Household Survey Report. https://www.censtatd.gov.hk/en/EIndexbySubject.html?pcode=B1130201&scode=453.

- Chan, H.-Y., Chen, A., Ma, W., Sze, N.-N., & Liu, X. (2021a). COVID-19, community response, public policy, and travel patterns: A tale of Hong Kong. Transport Policy, 106, 173–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2021.04.002

- Chan, R. C. H., & Fung, S. C. (2022). Elevated levels of COVID-19-related stress and mental health problems among parents of children with developmental disorders during the pandemic. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 52(3), 1314–1325. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-021-05004-w

- Chan, S. M., Wong, H., Chung, R. Y.-N., & Au-Yeung, T. C. (2021b). Association of living density with anxiety and stress: A cross-sectional population study in Hong Kong. Health & Social Care in the Community, 29(4), 1019–1029. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.13136

- Chen, X., & Zhong, H. (2021). Development and crime drop: A time-series analysis of crime rates in Hong Kong in the last three decades. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 65(4), 409–433. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X20969946

- Cheung, Y. W., & Cheung, N. W. T. (2013). Crime and criminal justice in Hong Kong. In Handbook of Asian criminology (pp. 183–198). Springer New York.

- Choi, E. P. H., Hui, B. P. H., & Wan, E. Y. F. (2020). Depression and anxiety in Hong Kong during COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(10), 3740. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103740

- Chu, K. A., Schwartz, C., Towner, E., Kasparian, N. A., & Callaghan, B. (2021). Parenting under pressure: A mixed-methods investigation of the impact of COVID-19 on family life. Journal of Affective Disorders Reports, 5(100161), 100161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadr.2021.100161

- Cohen, L. E., & Felson, M. (1979). Social change and crime rate trends: A routine activity approach. American Sociological Review, 44(4), 588. https://doi.org/10.2307/2094589

- De La Miyar, J. R., Hoehn-Velasco, L., & Silverio-Murillo, A. (2021). Druglords don’t stay at home: COVID-19 pandemic and crime patterns in Mexico City. Journal of Criminal Justice, 72.

- Demir, M., & Park, S. (2022). The effect of COVID-19 on domestic violence and assaults. Criminal Justice Review, 47(4), 445–463. https://doi.org/10.1177/07340168211061160

- Department of Justice. (2023). The policy for prosecuting cases involving domestic violence - definition of domestic violence. https://www.doj.gov.hk/en/publications/domesticviolence_2.html

- Estévez-Soto, P. R. (2021). Crime and COVID-19: Effect of changes in routine activities in Mexico City. Crime Science, 10(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40163-021-00151-y

- Evans, D. P., Hawk, S. R., & Ripkey, C. E. (2021). Domestic violence in Atlanta, Georgia before and during COVID-19. Violence and Gender, 8(3), 140–147. https://doi.org/10.1089/vio.2020.0061

- Fawole, O. I., Okedare, O. O., & Reed, E. (2021). Home was not a safe haven: Women's experiences of intimate partner violence during the COVID-19 lockdown in Nigeria. BMC Women's Health, 21(1), 32. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-021-01177-9

- Ferrara, P., Franceschini, G., Corsello, G., Mestrovic, J., Giardino, I., Vural, M., Pop, T. L., Namazova-Baranova, L., Somekh, E., Indrio, F., & Pettoello-Mantovani, M. (2021). Children witnessing domestic and family violence: A widespread occurrence during the Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. The Journal of Pediatrics, 235, 305–306.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2021.04.071

- Flury, M., Nyberg, E., & Riecher-Rössler, A. (2010). Domestic violence against women: Definitions, epidemiology, risk factors and consequences. Swiss Medical Weekly, 140, w13099. https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2010.13099

- Fong, T. C. T., Chang, K., & Ho, R. T. H. (2023). Association between quarantine and sleep disturbance in Hong Kong adults: The mediating role of COVID-19 mental impact and distress. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 14, 1127070. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1127070

- Forke, C. M., Catallozzi, M., Localio, A. R., Grisso, J. A., Wiebe, D. J., & Fein, J. A. (2019). Intergenerational effects of witnessing domestic violence: Health of the witnesses and their children. Preventive Medicine Reports, 15(100942), 100942. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2019.100942

- Gulati, G., & Kelly, B. D. (2020). Domestic violence against women and the COVID-19 pandemic: What is the role of psychiatry? International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 71(101594), 101594. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2020.101594

- Hartley, K., & Jarvis, D. S. L. (2020). Policymaking in a low-trust state: Legitimacy, state capacity, and responses to COVID-19 in Hong Kong. Policy and Society, 39(3), 403–423. https://doi.org/10.1080/14494035.2020.1783791

- Harville, E. W., Taylor, C. A., Tesfai, H., Xiong, X., & Buekens, P. (2011). Experience of Hurricane Katrina and reported intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 26(4), 833–845. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260510365861

- Herzog, J. I., & Schmahl, C. (2018). Adverse childhood experiences and the consequences on neurobiological, psychosocial, and somatic conditions across the lifespan. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9, 420. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00420

- Howe, D. (2005). Child abuse and neglect: Attachment, development and intervention. Red Globe Press.

- Huang, N., Zhang, S., Mu, Y., Yu, Y., Riem, M. M. E., & Guo, J. (2024). Does the COVID-19 pandemic increase or decrease the global cyberbullying behaviors? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 25(2), 1018–1035. https://doi.org/10.1177/15248380231171185

- Hughes, K., Bellis, M. A., Hardcastle, K. A., Sethi, D., Butchart, A., Mikton, C., Jones, L., & Dunne, M. P. (2017). The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Public Health, 2(8), e356–e366. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30118-4

- Humphreys, K. L., Myint, M. T., & Zeanah, C. H. (2020). Increased risk for family violence during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pediatrics, 146(1), https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-0982

- Ioannidis, J. P. A., Zonta, F., & Levitt, M. (2023). Estimates of COVID-19 deaths in Mainland China after abandoning zero COVID policy. European Journal of Clinical Investigation, 53(4).

- Katz, I., Katz, C., Andresen, S., Bérubé, A., Collin-Vezina, D., Fallon, B., Fouché, A., Haffejee, S., Masrawa, N., Muñoz, P., Priolo Filho, S. R., Tarabulsy, G., Truter, E., Varela, N., & Wekerle, C. (2021). Child maltreatment reports and Child Protection Service responses during COVID-19: Knowledge exchange among Australia, Brazil, Canada, Colombia, Germany, Israel, and South Africa. Child Abuse & Neglect, 116(Pt 2), 105078. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.105078

- Knight, L., & Hester, M. (2016). Domestic violence and mental health in older adults. International Review of Psychiatry, 28(5), 464–474. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540261.2016.1215294

- Krishnakumar, A., & Verma, S. (2021). Understanding domestic violence in India during COVID-19: A routine activity approach. Asian Journal of Criminology, 16(1), 19–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11417-020-09340-1

- Lau, S. M., Chan, Y. C., Fung, K. K., Hung, S. L., & Feng, J. (2021). Hong Kong under COVID-19: Roles of community development service. International Social Work, 64(2), 270–274. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020872820967734

- Lau, S. S. S., Ho, C. C. Y., Pang, R. C. K., Su, S., Kwok, H., Fung, S.-F., & Ho, R. C. (2022). COVID-19 burnout subject to the dynamic zero-COVID policy in Hong Kong: Development and psychometric evaluation of the COVID-19 burnout frequency scale. Sustainability, 14(14), 8235. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148235

- Leslie, E., & Wilson, R. (2020). Sheltering in place and domestic violence: Evidence from calls for service during COVID-19. Journal of Public Economics, 189(104241), 104241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104241

- Linden, A. (2015). Conducting interrupted time-series analysis for single- and multiple-group comparisons. The Stata Journal: Promoting Communications on Statistics and Stata, 15(2), 480–500. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536867X1501500208

- Linden, A. (2017). A comprehensive set of postestimation measures to enrich interrupted time-series analysis. The Stata Journal: Promoting Communications on Statistics and Stata, 17(1), 73–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536867X1701700105

- Linden, A. (2018). Using forecast modelling to evaluate treatment effects in single-group interrupted time series analysis. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 24(4), 695–700. https://doi.org/10.1111/jep.12946

- Liu, M., Xue, J., Zhao, N., Wang, X., Jiao, D., & Zhu, T. (2021). Using social media to explore the consequences of domestic violence on mental health. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(3-4), NP1965–1985NP. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260518757756

- Liu, Y., Chee, J. H., & Wang, Y. (2022). Parental burnout and resilience intervention among Chinese parents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1034520. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1034520

- Matus, K., Sharif, N., Li, A., Cai, Z., Lee, W. H., & Song, M. (2023). From SARS to COVID-19: the role of experience and experts in Hong Kong’s initial policy response to an emerging pandemic. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 10(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01467-z

- Meltzer, H., Doos, L., Vostanis, P., Ford, T., & Goodman, R. (2009). The mental health of children who witness domestic violence. Child & Family Social Work, 14(4), 491–501. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2206.2009.00633.x

- Payne, J. L., Morgan, A., & Piquero, A. R. (2022). COVID-19 and social distancing measures in Queensland, Australia, are associated with short-term decreases in recorded violent crime. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 18(1), 89–113. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-020-09441-y

- Pereda, N., & Díaz-Faes, D. A. (2020). Family violence against children in the wake of COVID-19 pandemic: a review of current perspectives and risk factors. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 14(1), 40. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-020-00347-1

- Piquero, A. R., Jennings, W. G., Jemison, E., Kaukinen, C., & Knaul, F. M. (2021). Domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic - Evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Criminal Justice, 74(101806), 101806. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2021.101806

- Rebbe, R., Lyons, V. H., Webster, D., & Putnam-Hornstein, E. (2022). Domestic violence alleged in California child maltreatment reports during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Family Violence, 37(7), 1041–1048. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-021-00344-8

- Schneider, D., Harknett, K., & McLanahan, S. (2016). Intimate partner violence in the Great Recession. Demography, 53(2), 471–505. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-016-0462-1

- Sediri, S., Zgueb, Y., Ouanes, S., Ouali, U., Bourgou, S., Jomli, R., & Nacef, F. (2020). Women’s mental health: Acute impact of COVID-19 pandemic on domestic violence. Archives of Women's Mental Health, 23(6), 749–756. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-020-01082-4

- Seposo, X., Celis-Seposo, A. K., & Ueda, K. (2023). Child abuse consultation rates before vs during the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan. JAMA Network Open, 6(3), e231878. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.1878

- Shariati, A., & Guerette, R. T. (2023). Findings from a natural experiment on the impact of covid-19 residential quarantines on domestic violence patterns in New Orleans. Journal of Family Violence, 38(2), 203–214. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-022-00380-y

- Social Welfare Department. (2020). Child Abuse … … It Matters You. https://www.swd.gov.hk/vs/doc/publicity/Child%20Abuse%20It%20Matters%20You.pdf.

- Su, Z., McDonnell, D., Cheshmehzangi, A., Ahmad, J., Chen, H., Šegalo, S., & Cai, Y. (2022). Corrigendum: What “Family Affair?” domestic violence awareness in China. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 990348. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.990348

- Sun, I. Y., Wu, Y., Wang, X., & Xue, J. (2022). Officer and organizational correlates with police interventions in domestic violence in China. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(11-12), NP8325–NP8349. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260520975694

- Tso, W. W. Y., Wong, R. S., Tung, K. T. S., Rao, N., Fu, K. W., Yam, J. C. S., Chua, G. T., Chen, E. Y. H., Lee, T. M. C., Chan, S. K. W., Wong, W. H. S., Xiong, X., Chui, C. S., Li, X., Wong, K., Leung, C., Tsang, S. K. M., Chan, G. C. F., Tam, P. K. H., … Lp, P. (2022). Vulnerability and resilience in children during the COVID-19 pandemic. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 31(1), 161–176. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-020-01680-8

- Wong, D. F. K., Lau, Y. Y., Chan, H. S., & Zhuang, X. (2022). Family functioning under COVID-19: An ecological perspective of family resilience of Hong Kong Chinese families. Child & Family Social Work, 27(4), 838–850. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12934

- Zhang, H. (2022). The influence of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic on family violence in China. Journal of Family Violence, 37(5), 733–743. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-020-00196-8

- Zhao, S. Z., Wong, J. Y. H., Luk, T. T., Wai, A. K. C., Lam, T. H., & Wang, M. P. (2020). Mental health crisis under COVID-19 pandemic in Hong Kong, China. International Journal of Infectious Diseases, 100, 431–433. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2020.09.030