ABSTRACT

Rehabilitation services in education settings are evolving from pull-out interventions focused on remediation for children and youth with special education needs to inclusive whole-school tiered approaches focused on participation. A limited number of discipline-specific practice models for tiered services currently exist. However, there is a paucity of explanatory theory. This realist synthesis was conducted as a first step towards developing a middle-range explanatory theory of tiered rehabilitation services in education settings. The guiding research question was: What are the outcomes of successful tiered approaches to rehabilitation services for children and youth in education settings, in what circumstances do these services best occur, and how and why? An expert panel identified assumptions regarding tiered services. Relevant literature (n = 52) was located through a systematic literature review and was analysed in three stages. Several important contextual characteristics create optimal environments for implementing tiered approaches to rehabilitation services via three main mechanisms: (a) collaborative relationships, (b) authentic service delivery, and (c) reciprocal capacity building. Positive outcomes were noted at student, parent, professional, and systems levels. This first-known realist synthesis regarding tiered approaches to rehabilitation services in education settings advances understanding of the contexts and mechanisms that support successful outcomes.

Introduction

Across speech-language pathology (SLP), occupational therapy (OT), and physiotherapy (PT), researchers and practitioners are exploring tiered approaches to delivering rehabilitation services in education settings as an alternative to remediation-focused, one-to-one, pull-out models (Archibald, Citation2017; Camden, Leger, Morel, & Missiuna, Citation2015; Campbell, Missiuna, Rivard, & Pollock, Citation2012; Chu, Citation2017; Ebbels, McCartney, Slonims, Dockrell, & Norbury, Citation2019; Hutton, Citation2009; Kaelin et al., Citation2019; Mills & Chapparo, Citation2018). Incorporating elements of response to intervention (RTI), and several inter-professional and collaborative consultation models, tiered approaches to rehabilitation aim to enhance all students’ participation, and promote the inclusion of children and youth with special education needs (Campbell, Kennedy, Pollock, & Missiuna, Citation2016; Gustafson, Svensson, & Fälth, Citation2014; Idol, Paolucci-Whitcomb, & Nevin, Citation2010; Missiuna et al., Citation2015; Pfeiffer, Pavelko, Hahs-Vaughn, & Dudding, Citation2019). Although consensus has not been reached regarding one cogent definition of inclusion, it is generally understood as providing education to all students, including students with disabilities, in general, education classrooms, with needed support embedded therein (Amor et al., Citation2019; Krischler, Powell, & Pit-Ten Cate, Citation2019; McCrimmon, Citation2014; Ritter, Wehner, Lohaus, & Krämer, Citation2020). Inclusive tiered approaches to delivering rehabilitation services are most typically provided along a continuum of three tiers (Chu, Citation2017). Tier one rehabilitation services are delivered at a school-wide or classroom-wide level and are beneficial for all (Campbell et al., Citation2016). In tier two, targeted rehabilitation services are provided for aggregates of students requiring additional support for specific issues, and are necessary for some (Law, Reilly, & Snow, Citation2013). Tier three refers to individualised, intensive rehabilitation services that are essential for a few (Ebbels et al., Citation2019). Services are needs-based and can change over time (Ebbels et al., Citation2019). Students receiving tier two or tier three services continue to receive tier one services alongside peers in their classroom (Chu, Citation2017).

Outcome studies have documented positive results when rehabilitation services in schools are offered at various tiers. For example, Throneburg, Calvert, Sturm, Paramboukas, and Paul (Citation2000) found that students with SLP need who received whole-class and pull-out services made significantly better gains in curricular vocabulary knowledge than students in pull-out intervention only. A randomised controlled trial involving 3- to 6-year-olds indicated that a tier-one SLP reading intervention had a significant impact on pre-literacy (Bleses et al., Citation2018), and a pre-test, post-test control group study indicated that a tier-one OT intervention improved kindergarteners’ motor skills (Ohl et al., Citation2013).

Research regarding tiered models of rehabilitation services in education settings has elucidated several benefits and barriers. Benefits include: (a) enhanced school, home, and community participation, (b) earlier identification of difficulties, (c) problem prevention, (d) capacity development among educators/families, (e) responsiveness to unique school/classroom/student needs, and (f) reduction in service wait times, (Cahill, McGuire, Krumdick, & Lee, Citation2014; Camden et al., Citation2015; Campbell et al., Citation2016; Ebbels et al., Citation2019; Missiuna et al., Citation2015, Citation2016; Wilson & Harris, Citation2018). Barriers include: (a) lack of clarity regarding rehabilitation professionals’ roles at each tier, (b) insufficient resources, (c) rehabilitation professionals’ prioritisation of tier three services, (d) variations in professionals’ skills for each tier, and (e) operational variations among coordinating organisations (Cahill et al., Citation2014; Campbell et al., Citation2012; Ebbels et al., Citation2019; Wilson & Harris, Citation2018).

Of the studies cited in the preceding paragraph, several are based on the Partnering for Change (P4C) tiered model of OT practice (Missiuna et al., Citation2016; Wilson & Harris, Citation2018). Partnering for Change (P4C) was designed to be a more inclusive alternative to decontextualised pull-out models for children with developmental coordination disorder by focusing on ‘building Capacity through Collaboration and Coaching in Context’ (4 Cs) (Missiuna et al., Citation2016, p. 146). Camden et al. (Citation2015) proposed an inter-disciplinary model, the Apollo model, to guide tiered practice in community settings including schools, and Ebbels et al. (Citation2019) described an evidence-informed untitled tiered practice model of speech and language service delivery for children with language disorders. The remaining studies cited above described tiered rehabilitation service within the education system’s established RTI structure (Bleses et al., Citation2018; Cahill et al., Citation2014; Ohl et al., Citation2013).

Although the importance of practice models in SLP, OT, and PT is well established, rehabilitation has been broadly criticised for neglecting the role of explanatory theory (Darrah, Loomis, Manns, Norton, & May, Citation2006; McColl, Law, & Stewart, Citation2015; Rodriguez & Gonzalez Rothi, Citation2009; Siegert, McPherson, & Dean, Citation2005). To our knowledge, there are no current explanatory theories specific to tiered approaches to delivering rehabilitation services in education settings. Explanatory theory is imperative to guide the development and empirical testing of programmes and interventions and to inform policy (Jagosh, Citation2020a; Siegert et al., Citation2005; Whyte, Citation2014). Yet research for the purpose of generating explanatory theory is often not prioritised due to a focus on outcome studies, lack of funding for research to develop theory, and journal limitations regarding publishing theoretical manuscripts (Chatterjee, Citation2005; Siegert et al., Citation2005). Discussion of what distinguishes theories and practice models is beyond the scope of this paper; however, theories are generally understood as a broad set of analytical principles designed to be explanatory whereas models are typically descriptive and have a narrower focus (Nilsen, Citation2015).

Considering the global interest in, and noted benefits of, tiered approaches to rehabilitation services in education settings, along with the paucity of related theory, our research team’s long-term aim is to develop the first-known middle-range theory of tiered rehabilitation services in education settings to guide future research and inform policy and practice. We have adopted the definition of middle-range theory put forth by Merton (Citation1967, p. 39): ‘theories that lie between the minor but necessary working hypotheses … .and the all inclusive systematic efforts to develop a unified theory that will explain all observed uniformities … ’.

Overview of Research

Realist evaluation (RE) is a theory-driven approach to research that is based on realist ontology (i.e., a mind-independent reality exists but perception of reality is constructed) (Waldron et al., Citation2020; Wong et al., Citation2016). The goal of RE is to generate middle-range explanatory program theory by evaluating existing programs and interventions through asking 'how, why, for whom, to what extent, and in what context complex interventions work' (Wong et al., Citation2016, p. 2). Although an extensive process, the use of RE to develop middle-range programme theory is increasing because of its utility in uncovering how a programme brings about outcomes (expected and non-expected) as well as identifying what those outcomes are rather than exclusively focusing on if a programme brings about a specific set of expected outcomes (Doi, Wason, Malden, & Jepson, Citation2018; Fick & Muhajarine, Citation2019; Jefford, Stockler, & Tattersall, Citation2003; Pawson, Citation2006). Furthermore, while outcome studies aim to reduce complexity by eliminating confounding variables, RE aims to identify and examine as many variables as possible that may influence the manifestation and outcomes of a programme (Fick & Muhajarine, Citation2019). RE is based on the belief that programme outcomes (O) are generated when certain mechanisms (M) are activated by programmes or interventions delivered in certain contexts (C). For our study, context was defined as the settings, structures, environments, conditions, and circumstances within which a programme or intervention occurs (Shaw et al., Citation2018). Mechanism was defined as the way in which individuals involved in a programme reason about and respond to the programme or interventions (i.e., demonstrate agency) in the particular context in which a programme is delivered (Shaw et al., Citation2018). Outcome was defined as the impacts of a programme resulting from the interaction between mechanisms and contexts (De Souza, Citation2013).

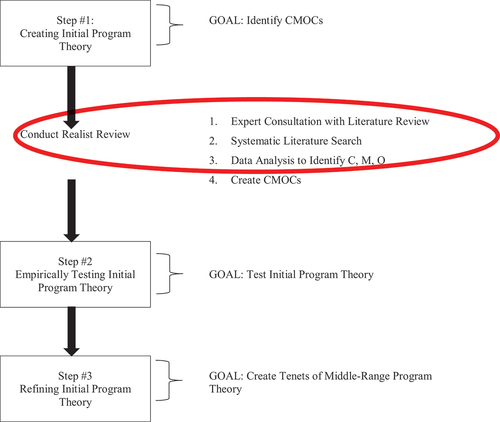

There are three main steps in the iterative and extensive process of RE to generate middle-range programme theory: (1) creating an initial programme theory, (2) empirically testing the initial programme theory, and (3) refining the initial programme theory to create the tenets of the middle-range programme theory (Fick & Muhajarine, Citation2019). This paper reports on research conducted towards realising Step #1, creating an initial programme theory.

Step #1: Creating Initial Programme Theory

In RE, the first steps toward creating an initial programme theory involves: (a) identifying the contexts, mechanisms, and outcomes relevant to a programme or intervention; then (b) combining and mapping them as a set of context-mechanism-outcome configurations or CMOCs (i.e., C + M = O) (Pawson, Citation2006). One of the main ways to identify relevant contexts, mechanisms, and outcomes (and the avenue adopted for this research study) is conducting a realist synthesis of relevant literature (Marchal, Kegels, & Van Belle, Citation2018). Realist synthesis is a method for literature review that guides the interrogation and synthesis of existing literature to identify ‘what works for whom in what circumstances and in what respects’ (Pawson, Citation2006, p. 74). Unlike meta-analyses and traditional systematic reviews, which favour the inclusion of randomised controlled trials, realist syntheses expand beyond empirical studies to include other forms of literature while preserving the requirement for systematic and transparent search and selection processes (Booth, Wright, & Briscoe, Citation2018). The research question used to guide this realist synthesis was: What are the outcomes of successful tiered approaches to rehabilitation services for children and youth in education settings (O), in what circumstances do these services best occur (C), and how and why (M)? This study reports on the broad contexts, mechanisms, and outcomes relevant to tiered rehabilitation services in education settings identified via the realist synthesis (i.e., part [a] of Step #1). The immediate next step of our research team (to be reported in a subsequent publication) is to apply an extant theory to guide the creation of CMOCs (i.e., part [b] of Step #1). : Realist Evaluation Process offers a diagrammatic representation of the whole RE process and indicates which components are reported herein.

Figure 1. Realist Evaluation Process (Created based on Emmel, Greenhalgh, Manzano, Monaghan, & Dalkin, Citation2018).

Methods

The Realist and Meta-Narrative Evidence Syntheses: Evolving Standards (RAMESES) (found at https://bmcmedresmethodol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2288-11-115) were used to guide and report our realist synthesis (Wong, Greenhalgh, Westhorp, Buckingham, & Pawson, Citation2013).

Expert Consultation and Literature Review

Realist syntheses begin with participatory expert consultation and literature review to identify assumptions about when, how, why, and for whom a programme or intervention works (Pawson, Greenhalgh, Harvey, & Walshe, Citation2005). Our multidisciplinary team of researchers and clinicians with expertise in tiered approaches to school-based rehabilitation functioned as the expert panel. Panel members had both published and reviewed relevant literature prior to convening for a participatory roundtable discussion (e.g., Campbell et al., Citation2016, Citation2012; Kennedy et al., Citation2018; Missiuna et al., Citation2015, Citation2012, Citation2016, Citation2012; Pollock, Dix, Whalen, Campbell, & Missiuna, Citation2017). An impartial experienced independent researcher (SV), hired to conduct data analysis, facilitated the roundtable discussion to elicit assumptions related to tiered services. The roundtable discussion was recorded and transcribed. Contexts (C), mechanisms (M), and outcomes (O) were drawn from the recorded discussion and later used to guide data analysis. See Supplementary File Part 1: Assumptions Related to Tiered Rehabilitation Services. Ethics approval was not required for the roundtable discussion since our team of experts were not themselves the focus of the research and the discussion was conducted during the ordinary course of involvement with the current research team (Government of Canada, Citation2018). All team members voluntarily consented to participation and agreed to be recorded. Hence, ethical principles outlined in the Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans were upheld (Government of Canada, Citation2018).

Searching Process

A member of the team (IE) searched the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Education Resources Information Center (ERIC), and Web of Science databases. Recognising ‘there is a limit on what a review can cover’ (Pawson, Citation2006, p. 36), we selected these databases because relevant literature could best be located therein (rehabilitation/education/both). In consultation with the research team, IE and a library liaison from McMaster University constructed a search strategy comprising 37 terms reflecting three independent concepts: tiered services (n = 9); rehabilitation services (n = 22); and education settings (n = 6). IE searched terms independently and then combined terms for the same concept using the Boolean search operator OR. Next, IE combined searches for the three independent concepts with the Boolean operator AND to yield articles including all three concepts. Inclusion criteria for the initial search required that articles be published: (a) from 1996, (b) in English, (c) in a peer-reviewed source. The literature search began in November 2017 and continued iteratively until April 2018. See Supplementary File Part 2: Search Strategy Protocol.

Selection and Appraisal of Documents

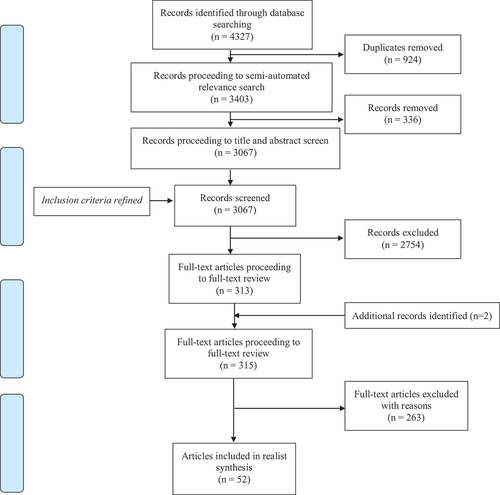

The search process yielded 4327 citations, reduced to 3403 by removing duplicates via EndNote (Clarivate Analytics, Citation2018). The principal investigator (WC) and one member of the research team (AW) further reduced citations to 3067 using a semi-automated relevance search conducted in EndNote (Clarivate Analytics, Citation2018). These 3067 articles proceeded to title and abstract screen (AW/LR) using Covidence (Veritas Health Information, Citation2018). To ensure the relevance of articles, we refined inclusion criteria such that articles had to meet all of the following: (a) services must be delivered at more than one tier, (b) tier one services must be present, (c) service delivery must involve one or more rehabilitation professional(s) (OT/PT/SLP), (d) services must be implemented in an education setting (preschool to end of high school), (e) students must be 2 to 21 years, and (f) articles must pertain to high-income economies (The World Bank, Citation2017) (to permit inclusion of literature applicable to Canadian context). Records that included relevant terminology but did not contain enough information to inform decision-making were advanced to full-text review. AW and LR engaged in dual review for training and confirmed reviewer agreement prior to single reviewer mode (agreement = 90.7%). Ultimately, 313 articles proceeded to full-text review plus two identified by WC (these two additional articles were known to the research team but were not located during the database search).

AW and LR conducted full-text review of 315 articles in consultation with WC. Training involved dual full-text review of 32 articles (AW/LR) to confirm agreement prior to single reviewer mode (K = 0.904). Problematic articles identified during single review underwent dual review (n = 8). Fifty-two articles met the inclusion criteria. See : PRISMA Flow Diagram of Document Selection Process.

Figure 2. PRISMA Flow Diagram of Document Selection Process (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, & Altman, Citation2009).

Data Extraction, Analysis, and Synthesis

Consistent with both qualitative and realist approaches to data analysis, SV completed data extraction, analysis, and synthesis in three stages: data preparation, coding, and moving from codes to descriptive categories (Bazeley, Citation2013; Gilmore, McAuliffe, Power, & Vallières, Citation2019; Pawson, Citation2006). Data preparation involved: (1) uploading the 52 articles to NVivo (QSR International, Citation2018), (2) inputting terms (with definitions) related to contexts (C), mechanisms (M), and outcomes (O) that were drawn from RE methodological literature and the expert panel discussion regarding programme assumptions (thereby serving as a deductive data extraction matrix), and (3) reviewing all literature for conceptual understanding (Gilmore et al., Citation2019). Coding involved reading documents in detail, extracting data relevant to contexts (C), mechanisms (M), and outcomes (O), and organising extracted data under appropriate matrix terms or nodes. Data were extracted both deductively (as per terms in the matrix) and inductively using both topic coding (codes that describe the literal topic of an excerpt) and analytical coding (codes that interpret or reflect the meaning of an excerpt) (Richards, Citation2009). Combining deductive and inductive data extraction and using both topic and analytical inductive coding enhanced analytical rigour and is compatible with both qualitative data analysis and realist methodology (Fereday & Muir-Cochrane, Citation2016; Gilmore et al., Citation2019). Moving from codes to descriptive categories involved combining and abstracting codes through ‘continuous dialogue’ with the data to create analytically useful and focused categories (Bazeley, Citation2013, p. 244; Jagosh, Citation2020a). Continuous dialogue with the data can be described as a process of reading (re-reading), analysing, and comparatively interrogating data contained in codes in order to identify common ideas and sort codes into categories with similar characteristics (Bazeley, Citation2013). Analytical debriefing with the research team supported confirmability and triangulation (Lincoln & Guba, Citation1985). Memo-writing (at all stages), diagramming, and visual mapping supplemented analysis (Bazeley, Citation2013).

Results

See Supplementary File Part 3: Document Characteristics for an overview of included articles. For clarity and consistency, results (descriptive categories) are presented in response to each sequential component of the research question (i.e., outcomes, contexts, and mechanisms). Direct quotes have been used judiciously to illustrate and support findings (Richards, Citation2009). A summary of results is presented in .

Table 1. Summary of Results.

What are the Outcomes of Successful Tiered Approaches (O)?

Successful tiered approaches to rehabilitation services in education settings are characterised by several outcomes at the children and youth, parent and professional, and system level. For children and youth, successful tiered approaches facilitate the achievement of academic and rehabilitation goals and foster the development of skills needed to participate in everyday contexts (Ritzman, Sanger, & Coufal, Citation2006; Throneburg et al., Citation2000). Increased participation facilitates positive social outcomes, including a greater sense of inclusion and belonging. Silliman, Ford, Beasman, and Evans (Citation1999) noted ‘the greatest growth … occurs in the intertwined areas of social development and increased self-confidence, both of which … indirectly influence the motivation to achieve academically (p. 13).’ Other beneficial child and youth outcomes include earlier and potentially more accurate identification of needs resulting in an earlier intervention, decreased level of impairment, and decreased likelihood of labelling (e.g., learning disability) (Brebner, Attrill, Marsh, & Coles, Citation2017; Ehren & Nelson, Citation2005; Elksnin, Citation1997; Hutton, Tuppeny, & Hasselbusch, Citation2016).

For parents and professionals, successful tiered approaches cultivate growth and development. Increased knowledge and skills gained by parents and professionals led to deeper understanding of the needs of children and youth. Christner (Citation2015) stated ‘[t]he OT supports the classroom by providing a greater knowledge base to help support all students … .’ (p. 142). Findings indicated that parents and professionals developed confidence in their ability to carry knowledge and skills forward for use with future students (professionals) and/or in other contexts (parents/professionals). Parents in a study by Missiuna et al. (Citation2012), which evaluated the Partnering for Change tiered approach, reported having more confidence in advocating for their children. One parent stated, ‘The knowledge I gained absolutely helped my son to be more successful at school … .’ (p. 1449). In addition, education and rehabilitation professionals also developed greater insight about each other’s role and context. This led to ‘an appreciation of each individual’s unique contribution’ (Peña & Quinn, Citation2003, p. 54) and cultivated a culture of satisfaction, collaboration, and respect.

For systems, tiered approaches facilitated earlier and more timely intervention irrespective of formal identification of need. As a result, problem exacerbation may be prevented, and fewer children obtain formal diagnoses. In a study by Sanger, Mohling, and Stremlau (Citation2011), SLPs agreed that tiered approaches ‘support a model of prevention versus “wait until you fail” … are preventive and can decrease the number of students eligible for special education … ’ (p. 8). Tiered approaches can be more resource efficient since more children benefit and fewer children are referred for other (potentially more costly) services. Justice, McGinty, Guo, and Moore (Citation2009) asserted that ‘every dollar invested … will be returned to society in later years through a reduction in special education and other societal programmes … ’ (p. 61). In one study of a tiered approach aimed at addressing speech-sound errors and disorders, Mire and Montgomery (Citation2008) stated that the tiered approach ‘significantly improved the efficiency and effectiveness of SLPs in this district’ (p. 159). A final positive system-level outcome is the ongoing advancement of knowledge and resources regarding tiered approaches and curriculum development. As implementation and evaluation occurs, ‘more [is] learned about how general education and special education supports are integrated throughout the tiers of intervention to support students …’ (Johnson, Citation2012, p. 325). Both research-based evidence and practice-based expertise are imperative to informing sustainable tiered services. Researcher-practitioner partnerships can expand knowledge regarding tiered approaches as can individual practitioners who ‘lend their expertise to the design of interventions for students’ (Linan-Thompson & Ortiz, Citation2009, p. 116).

In what Circumstances do these Services Best Occur (C)?

Several macro-, meso-, and micro-level contextual circumstances for successful tiered approaches were identified. On a macro-level, there must be broad acceptance that children with disabilities can learn in inclusive general education classrooms and, therefore, should be included therein (Horn & Banerjee, Citation2009; Linan-Thompson & Ortiz, Citation2009). Legislation that mandates inclusive education and aims to ensure success for all students is also an important macro-level contextual condition (Ohl et al., Citation2013; Ritzman et al., Citation2006). For example, in the United States, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) and the No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB) are largely credited for prompting a shift towards tiered approaches to rehabilitation services in education. Allocation of funds to adequately support legislation enactment is imperative (Cavallaro, Ballard-Rosa, & Lynch, Citation1998). Finally, as stated by Horn and Banerjee (Citation2009, p. 407), macro-level contexts must include a ‘high quality, universally designed curriculum that supports all children’s access to and participation in the general curriculum’ (p. 407).

On a meso-level, consensus must exist that current approaches to rehabilitation services are problematic (e.g., ‘wait to fail’) and that tiered approaches would better meet student need (Christner, Citation2015; Troia, Citation2005). School boards and employers of rehabilitation professionals should possess clear guidelines (i.e., policies/procedures) explicitly addressing tiered approaches (Cahill et al., Citation2014; Paul, Blosser, & Jakubowitz, Citation2006). For example, Pollock et al. (Citation2017) reported that ‘education to stakeholders, such as school boards, principals, other health care professionals, and families, was important to raise their awareness of the [tiered] model and how it differs from current practice’ (p. 248). Where appropriate, partnerships could be established with universities or professional organisations to support guideline development (e.g., American Speech-Language-Hearing Association) (Bahr, Velleman, & Ziegler, Citation1999; Reeder, Arnold, Jeffries, & McEwen, Citation2011).

Resource availability is also a fundamental meso-level contextual circumstance. Time must be allotted to enable rehabilitation professionals to have a consistent and ongoing presence in schools and to adopt a workload orientation that considers direct and indirect activities across all tiers rather than a caseload orientation focusing on direct activities for individual students receiving services at tier three (Chu, Citation2017; Ehren & Nelson, Citation2005). Dedicated time to meet with educators and attend school-wide meetings must be an ‘untouchable’ aspect of supporting students (Silliman et al., Citation1999, p. 13). Administrative support is closely linked to time provision for rehabilitation professionals (Bose & Hinojosa, Citation2008). Supportive administrators are characterised as leaders in inclusive education who understand, value, and allot adequate time to tiered approaches (Bose & Hinojosa, Citation2008; Silliman et al., Citation1999). Intervention resources required include documentation forms and materials appropriate to service delivery in all tiers (Chu, Citation2017; Johnson, Citation2012; Paul et al., Citation2006).

On a micro-level, all school-level stakeholders must acknowledge that parents, educators, rehabilitation professionals, and others are ‘part of the fabric of the school’ (Campbell et al., Citation2012, p. 56) and that all are equal and integral partners in supporting students in general education classrooms (Brebner et al., Citation2017; Christner, Citation2015; Chu, Citation2017). The knowledge, skills, and characteristics of rehabilitation professionals are important to the micro-level context. A strong evidence-informed body of disciplinary knowledge is imperative combined with knowledge of curriculum (Bose & Hinojosa, Citation2008; Chu, Citation2017; Ehren, Citation2000). Rehabilitation professionals must possess a clear perspective on their role within education and understand others’ roles (Ehren & Whitmire, Citation2009; Paul et al., Citation2006). Essential skills include advocacy, effective communication, solution-focused problem solving, and time management (Barnett & O’shaughnessy, Citation2015; Bose & Hinojosa, Citation2008; Christner, Citation2015; Sanger et al., Citation2011). Other important characteristics of rehabilitation professionals include openness, flexibility, responsivity, and respect (Bose & Hinojosa, Citation2008; Ritzman et al., Citation2006; Silliman et al., Citation1999; Soto Torres, Citation2018).

Why and How (M)?

Three main mechanisms were identified that operated within the contexts described above and lead to beneficial outcomes: fostering collaborative relationships, delivering authentic services, and building capacity for all.

Fostering Collaborative Relationships

Fostering collaborative relationships is an essential mechanism of successful tiered approaches to rehabilitation in education. Collaboration must include all ‘key players’ (Christner, Citation2015, p. 141) such as educators, rehabilitation professionals, parents, administrators, and other related service providers. Key players are respected and trusted co-equal partners whose unique expertise is understood and valued. Ehren and Whitmire (Citation2009) emphasised that ‘collaborative efforts are informed and enhanced by the expertise and experience of others’ (p. 100). Effective collaboration requires commitment (ideally voluntary) from all key players to the delivery of effective tiered services and to the collaborative relationship itself. Peña and Quinn (Citation2003) stated that the evolutionary and dynamic process of effective collaboration ‘takes time, commitment, and nurturing’ (p. 54). Fostering collaborative relationships also requires clear, consistent, constructive, and open communication that is understandable to all. Embedded within fostering collaborative relationships is a sense of shared responsibility and accountability for the success of all children and youth including ‘shared ownership of problems among equals’ (Paul et al., Citation2006, p. 8). Shared responsibility is reflected in shared assessments, goal setting, and decision-making. Hadley, Simmerman, Long, and Luna (Citation2000) iterated that in fostering collaborative relationships, key players ‘jointly determine student needs, develop goals, plan activities to achieve the goals, implement the activities, and evaluate the progress of the students’ (p. 281). One way to promote shared responsibility is through utilisation of ‘common philosophical framework[s]’ (Paul et al., Citation2006, p. 8), including theories, models, and/or terminologies relevant within education. Finally, fostering collaborative relationships also involves varying degrees of shared responsibility for teaching, or co-teaching (Bahr et al., Citation1999; Brebner et al., Citation2017; Justice & Kaderavek, Citation2004; Ritzman et al., Citation2006; Silliman et al., Citation1999; Soto, Mu Ller, Hunt, & Goetz, Citation2001; Staskowski & Rivera, Citation2005). Co-teaching can take many nuanced and individualised forms including co-planning only, educator delivering lessons and rehabilitation professional circulating (to tailor content/provide support as needed), rehabilitation professional delivering lessons (e.g., phonological awareness) and educator observing or circulating. Justice (Citation2006) noted ‘improved outcomes … when SLPs and classroom teachers collaboratively plan and co-teach language lessons in preschool and elementary classrooms’ (p. 287).

Delivering Authentic Services

In delivering authentic services, all aspects of service delivery including assessment, goal setting, intervention, and progress monitoring must be curriculum relevant and promote access to and achievement of curricular content. Jackson, Pretti-Frontczak, Harjusola-Webb, Grisham-Brown, and Romani (Citation2009) stated:

Assessment practices are considered authentic when they are conducted in familiar or typical settings, with familiar and interesting toys and materials, and by people who are familiar to the child (Bagnato & Yeh-Ho, Citation2006). Further, authentic assessment practices encourage children to show what they know and can do in the ways in which they would typically use the concept or skill … .(p. 429)

Roth and Troia (Citation2009, p. 77) recommended that ‘goals are authentic, anchored in the curriculum, and based on student needs and strengths’. Ritzman et al. (Citation2006) stated that intervention ‘supporting the activities of the classroom without interrupting the flow of the instructional discourse is essential’ (p. 225). Progress monitoring is ongoing and contextualised, and data gathered informs dynamic adjustments as needed.

Overall, authentic services are contextualised in the natural and age-appropriate environments within which children and youth normally participate including classrooms, playgrounds, gymnasiums, hallways, and cafeterias (Bose & Hinojosa, Citation2008; Campbell et al., Citation2012; Christner, Citation2015; Hadley et al., Citation2000). Where possible, services and supports are provided in real time during engagement in school tasks and activities. Finally, all aspects of authentic services, including the design of interventions are fluid and flexible. Flexibility enables rehabilitation professionals to be responsive to the needs of children and youth as they evolve and change and as the demands of the curriculum change.

Building Capacity for All

Building capacity for all involves ‘sharing of ideas and a spirit of “give and take” rather than simply one person advising the other’ (Bose & Hinojosa, Citation2008, p. 292). Providing services in authentic contexts such as the classroom not only cultivates skill development among children and youth requiring support (as previously described) but capacity is built among typically developing students. Grether and Sickman (Citation2008) stated that ‘ … typical peers can support diverse learners … These students can be the models and extension of the classroom teacher and SLP during the interactions with the classroom curriculum’ (p. 161).

Tiered approaches to rehabilitation promote capacity building among rehabilitation professionals-especially in understanding, developing, and/or adapting curriculum, classroom and behaviour management, whole-class instruction, classroom transitions, and other classroom practices (Ehren & Nelson, Citation2005; Staskowski & Rivera, Citation2005; Troia, Citation2005). Villeneuve (Citation2009) noted the importance for rehabilitation professionals to ‘understand school board policies, curriculum, and classroom practices of teachers in order to develop educationally relevant approaches to providing service’ (p. 213). Reciprocally, capacity also is built among educators. Benefits noted for educators include increased knowledge and skill in recognising and assessing need, providing educational activities that are therapeutic, and more consistently carrying over rehabilitation activities within the classroom (Brebner et al., Citation2017; Dodge, Citation2004; Ratzon et al., Citation2009). Noted benefits can be achieved incidentally through observation of rehabilitation professionals, discussions, and/or role modelling and more formally via in-service education or educational materials. Staskowski and Rivera (Citation2005) stated that ‘teachers and administrators learn the nature of the SLP’s expertise, and the SLP learns about classroom practices and the curriculum’ (p. 145). Finally, capacity building is extended to parents and families. Pollock et al. (Citation2017) reported that the Partnering for Change tiered approach ‘has been associated with … increased capacity of families … to support students’ (p. 250). Reeder et al. (Citation2011) outlined that physiotherapists promoted capacity building among parents and families via teaching and training.

Discussion

Jagosh, Citation2020b, 1, p. 28) stated that the main contribution of realist research is ‘cutting through the complexity of interventions … to find the most important aspects of that complexity … ’. Current findings of this realist synthesis clearly cut through the complexity of the included literature to elucidate several important contexts, mechanisms, and outcomes that are integral to successful tiered approaches to rehabilitation services in education settings. In their current descriptive form, these findings can be utilised as a checkpoint for policymakers who may be considering initiating new programmes involving rehabilitation services in education or reflecting on current models of service delivery. For example, in the Canadian province within which our team is situated, many rehabilitation services in schools are delivered using direct, pull-out services via contracted rehabilitation professionals (Deloitte & Touche LLP, Citation2010). Multiple challenges were noted in a review of rehabilitation services provided in schools including: (a) lengthy wait times for contracted services funded by the Ministry of Health, (b) confusion among educators and families because services are offered by multiple rehabilitation professionals (some employed by schools and others by contracted health care agencies), and, (c) uncertainty among educators about how to access and coordinate services on behalf of students (Deloitte & Touche LLP, Citation2010). One main recommendation emerging from the review was to ‘establish alternate models of service delivery across the province to improve access and wait times’ (Deloitte & Touche LLP, Citation2010, p. 8). Given that realist syntheses aim to inform policy regarding the delivery of social services (Pawson, Citation2006), tiered services could be considered one such ‘alternate model’ based on findings of earlier and more timely access to services, increased knowledge and understanding among parents and professionals, deeper insight and clarity among professionals regarding their roles, and improved service coordination.

Two fundamental macro-level contextual circumstances upon which successful tiered approaches are built both relate to inclusive education: (1) the belief that children and youth with special needs can and should learn in inclusive environments, and (2) the need for a high-quality, universally designed general curriculum that promotes access and participation for all students. These macro-level contextual circumstances are consistent with Article 24 of the United Nations Convention of the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, which mandates that people with disabilities be included in general education, have access to quality education in their communities, and be provided with accommodations and support to facilitate participation (United Nations, Citation2006). As previously stated, inclusive education is generally understood as providing education to all students, including students with disabilities, in general education classrooms, with needed support (Amor et al., Citation2019; Krischler et al., Citation2019; McCrimmon, Citation2014; Ritter et al., Citation2020). Although inclusive education is a global imperative with many noted benefits, barriers to implementation persist (Ahmad, Citation2012; Heyder, Südkamp, & Steinmayr, Citation2020; Klang et al., Citation2019; Krischler et al., Citation2019; Reid et al., Citation2018; Soto Torres, Citation2018). Types of barriers include epistemological, systemic, attitudinal, and practical (Ahmad, Citation2012; Heyder et al., Citation2020; Krischler et al., Citation2019; McCrimmon, Citation2014; Page, Mavropoulou, & Harrington, Citation2020). Several recent studies describe persistent barriers to inclusive education; for example, educators’ perceived or actual level of competence in supporting students with special education needs, if low, can be a barrier (Klang et al., Citation2019; Lavin, Francis, Mason, & LeSueur, Citation2020; Li & Cheung, Citation2019). Lavin et al. (Citation2020) reported lack of support for educators as a barrier and Klang et al. (Citation2019) noted barriers to social participation for children with special education needs in inclusive settings. Results of this realist synthesis explicitly extend knowledge regarding the implementation of inclusive education by indicating that tiered approaches to rehabilitation in education settings could address several of these barriers by building the capacity of educators, providing authentic support directly in classrooms in real time, and promoting positive social outcomes for students with special education needs.

Our review identified three main mechanisms for successful tiered services: fostering collaborative relationships, building capacity for all, and delivering authentic services. These mechanisms reflect three distinct ways in which rehabilitation professionals take reasoned action within their context to effect positive outcomes. Jagosh et al. (Citation2012) stated that each mechanism is a ‘generative force that leads to outcomes’ (p. 317). Literature regarding rehabilitation service delivery in schools has largely focused on collaboration between rehabilitation professionals and educators to promote student outcomes (Borg & Drange, Citation2019; Wintle, Krupa, Cramm, & DeLuca, Citation2017). Our findings regarding collaboration are consistent with existing literature in: (a) reinforcing the importance of collaboration, (b) reporting on essential features of collaborative relationships, (c) acknowledging the need for coordination among complex interfacing systems, and, (d) acknowledging that collaboration is situated within existing global, governmental, and professional discourses (Archibald, Citation2017; Flynn & Power-defur, Citation2013; Regan, Orchard, Khalili, Brunton, & Leslie, Citation2015; Villeneuve & Shulha, Citation2012; World Health Organization, Citation2010). However, despite broad acceptance of the importance of collaboration, research specific to inter-professional collaboration in schools indicates a lack of knowledge about how inter-professional collaboration meets the needs of educators and students, and how it includes students’ families (Kennedy et al., Citation2019). There is also a significant body of research indicating several persistent barriers to inter-professional collaboration (Borg & Drange, Citation2019; Pfeiffer et al., Citation2019; Wintle et al., Citation2017). For example, findings from a scoping review of inter-professional collaboration among OTs and educators suggested that OTs visiting schools from outside agencies, OT caseload size and educators’ busy schedules may constrain collaborative service delivery (Wintle et al., Citation2017). Similarly, Pfeiffer et al. (Citation2019) cite time constraints/scheduling and lack of administrative supports as barriers to collaboration for SLPs working in schools.

Our study extends current knowledge in two important ways. First, our findings not only confirm the importance of collaboration but situate it within a detailed consideration of the contexts that facilitate effective collaboration. Previous authors have identified contextual barriers to collaboration, but our research outlines the macro-, meso-, and micro-level contextual factors important to successful collaboration and, as such, provides a pragmatic checklist for considering contexts. Second, realist approaches posit that mechanisms may have interactive effects (Lacouture, Breton, Guichard, & Ridde, Citation2015). Much of the literature regarding rehabilitation services in schools has focused on a siloed understanding of collaboration. Some authors have suggested that inter-professional collaboration is the main construct in effectively supporting children with special education needs within education (Edwards, Citation2012; Knackendoffel, Dettmer, & Thurston, Citation2018). Research regarding the importance of capacity building for all stakeholders and delivery of authentic services is much sparser although it is explicitly addressed in the Partnering for Change research (Campbell et al., Citation2016; Missiuna et al., Citation2012). To some extent, an implicit assumption may exist that collaboration among rehabilitation professionals and educators necessarily begets capacity building (Kerins, Citation2018). However, our analysis elucidated three discreet but equally important mechanisms. Each mechanism possesses its own attributes and influences, yet undoubtedly interacts with other mechanisms within the described contexts to bring about successful student, parent and professional, and systems outcomes (Lacouture et al., Citation2015; Shaw et al., Citation2018). Our finding regarding mechanisms calls for a more robust understanding of delivery of rehabilitation services in education settings. The finding also sets the stage for advancing research and knowledge in a new way: moving from studying siloed constructs with a focus on collaboration to a more nuanced exploration of several potential mechanisms, how they are interconnected, and how they may work together symbiotically in context to promote successful outcomes.

Limitations

Although our search for literature focused on three highly relevant databases, it is possible that we did not locate all articles relevant to our research question. Additionally, as outlined by Pawson et al. (Citation2005), we acknowledge that our findings do not provide directive or generalisable formulae for programme implementation. Finally, similar to other kinds of qualitative research, we acknowledge that readers intending to implement or improve tiered approaches to rehabilitation services will need to use their judgement in interpreting and applying our findings in a manner that is aligned with their context.

Conclusion

This realist synthesis was conducted as part of the first step in a realist evaluation aimed at developing a middle-range explanatory programme theory of tiered rehabilitation services in education settings. More specifically this study answered the question: What are the outcomes of successful tiered approaches to rehabilitation services for children and youth in education settings, in what circumstances do these services best occur, and how and why? Findings advance our understanding of successful tiered approaches by clearly explicating and describing several macro-, meso-, and micro-level contextual factors and three main mechanisms (fostering collaborative relationships, delivering authentic services, and building capacity for all) that lead to positive outcomes for children, youth, parents, professionals, and systems. Findings also contribute to extending knowledge regarding inclusive education and inter-professional collaboration. Despite the limitations, our findings may be useful to those considering new programme development for delivering tiered rehabilitation services in education settings or to (re)assess existing programmes. Next steps in our programme of research involve using extant theory to guide the development of CMOCs, which will subsequently be tested through primary empirical research.

Acknowledgments

Wenonah Campbell is grateful for the current support of the John and Margaret Lillie Chair in Childhood Disability Research. The research team is appreciative of the contributions of Annette Wilkins, Cindy DeCola, Annie Jiang, and Eileen Kim. This article is dedicated to Nancy Pollock, our valued team member, collaborator, and friend. Nancy died after this article was written. She contributed to the project design and implementation of this study and is therefore recognized as a full author.

Data Availability

A list of the literature included as data can be found in Supplementary File Part 3: Document Characteristics.

Disclosure Statement

No financial interests or benefits have arisen from this research.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ahmad, W. (2012). Barriers of inclusive education for children with intellectual disability. Indian Streams Research Journal, 2(11), 1–4. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/325757581_Barriers_of_Inclusive_Education_for_Children_with_Intellectual_Disability

- Amor, A. M., Hagiwara, M., Shogren, K. A., Thompson, J. R., Verdugo, M. A., Burke, K. M., & Aguayo, V. (2019). International perspectives and trends in research on inclusive education: A systematic review. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 23(12), 1277–1295.

- Archibald, L. M. D. (2017). SLP-educator classroom collaboration: A review to inform reason-based practice. Autism & Developmental Language Impairments, 2, 1–17.

- Bagnato, S. J., & Yeh-Ho, H. (2006). High-stakes testing with preschool children: Violation of professional standards for evidence-based practice in early childhood intervention. KEDI International Journal of Educational Policy, 3(1), 23–43.

- Bahr, R. H., Velleman, S. L., & Ziegler, M. A. (1999). Meeting the challenge of suspected developmental apraxia of speech through inclusion. Topics in Language Disorders, 19(3), 19–35. https://journals.lww.com/topicsinlanguagedisorders/Fulltext/1999/05000/Meeting_the_Challenge_of_Suspected_Developmental.4.aspx

- Barnett, J. E., & O’shaughnessy, K. (2015). Enhancing collaboration between occupational therapists and early childhood educators working with children on the autism spectrum. Early Childhood Education Journal, 43(6), 467–472.

- Bazeley, P. (2013). Qualitative data analysis. London, UK: SAGE.

- Bleses, D., Hojen, A., Justice, L. M., Dale, P. S., Dybdal, L., Piasta, S. B., … Haghish, E. F. (2018). The effectiveness of a large-scale language and preliteracy intervention: The spell randomized controlled trial in Denmark. Child Development, 89(4), e342–e363.

- Booth, A., Wright, J., & Briscoe, S. (2018). Scoping and searching to support realist approaches. In N. Emmel, J. Greenhalgh, A. Manzano, M. Monaghan, & S. Dalkin (Eds.), Doing realist research (pp. 147–165). London, UK: SAGE.

- Borg, E., & Drange, I. (2019). Interprofessional collaboration in school: Effects on teaching and learning. Improving Schools, 22(3), 251–266.

- Bose, P., & Hinojosa, J. (2008). Reported experiences from occupational therapists interacting with teachers in inclusive early childhood classrooms. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 62(3), 289–297.

- Brebner, C., Attrill, S., Marsh, C., & Coles, L. (2017). Facilitating children’s speech, language and communication development: An exploration of an embedded, service-based professional development program. Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 33(3), 223–240.

- Cahill, S. M., McGuire, B., Krumdick, N. D., & Lee, M. M. (2014). National survey of occupational therapy practitioners’ involvement in response to intervention. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 68(6), 234–240.

- Camden, C., Leger, F., Morel, J., & Missiuna, C. (2015). A service delivery model for children with DCD based on principles of best practice. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics, 35(4), 412–425.

- Campbell, W., Kennedy, J., Pollock, N., & Missiuna, C. (2016). Screening children through response to intervention and dynamic performance analysis: The example of partnering for change. Current Developmental Disorders Reports, 3(3), 200–205.

- Campbell, W. N., Missiuna, C. A., Rivard, L. M., & Pollock, N. A. (2012). “Support for everyone”: Experiences of occupational therapists delivering a new model of school-based service. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. Revue Canadienne D’Ergothérapie, 79(1), 51–59.

- Cavallaro, C. C., Ballard-Rosa, M., & Lynch, E. W. (1998). A preliminary study of inclusive special education services for infants, toddlers, and preschool-age children in California. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 18(3), 169–182.

- Chatterjee, N. (2005). Theory for all and rehabilitation for the few (with money): Who does our theory serve? Disability and Rehabilitation, 27(24), 1503–1508.

- Christner, A. (2015). Promoting the role of occupational therapy in school-based collaboration: Outcome project. Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools, & Early Intervention, 8(2), 136–148.

- Chu, S. (2017). Supporting children with special educational needs (SEN): An introduction to a 3-tiered school-based occupational therapy model of service delivery in the United Kingdom. World Federation of Occupational Therapists Bulletin, 73(2), 107–116.

- Clarivate Analytics. (2018). EndNote. https://endnote.com/buy/

- Darrah, J., Loomis, J., Manns, P., Norton, B., & May, L. (2006). Role of conceptual models in a physical therapy curriculum: Application of an integrated model of theory, research, and clinical practice. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 22(5), 239–250.

- De Souza, D. E. (2013). Elaborating the context-mechanism-outcome configuration (CMOc) in realist evaluation: A critical realist perspective. Evaluation, 19(2), 141–154.

- Deloitte & Touche LLP. (2010). Review of School Health Support Services: Final report. http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/common/system/services/lhin/docs/deloitte_shss_review_report.pdf

- Dodge, E. P. (2004). Communication skills: The foundation for meaningful group intervention in school-based programs. Topics in Language Disorders, 24(2), 141–150.

- Doi, L., Wason, D., Malden, S., & Jepson, R. (2018). Supporting the health and well-being of school-aged children through a school nurse programme: A realist evaluation. BMC Health Services Research, 18(1), 664.

- Ebbels, S. H., McCartney, E., Slonims, V., Dockrell, J. E., & Norbury, C. F. (2019). Evidence-based pathways to intervention for children with language disorders. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 54(1), 3–19.

- Edwards, A. (2012). The role of common knowledge in achieving collaboration across practices. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 1(1), 22–32.

- Ehren, B. J. (2000). Maintaining a therapeutic focus and sharing responsibility for student success: Keys to in-classroom speech-language services. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 31(3), 219–229.

- Ehren, B. J., & Nelson, N. W. (2005). The responsiveness to intervention approach and language impairment. Topics in Language Disorders, 25(2), 120–131. https://journals.lww.com/topicsinlanguagedisorders/Fulltext/2005/04000/The_Responsiveness_to_Intervention_Approach_and.5.aspx

- Ehren, B. J., & Whitmire, K. (2009). Speech-language pathologists as primary contributors to response to intervention at the secondary level. Seminars in Speech and Language, 30(2), 90–104.

- Elksnin, L. K. (1997). Collaborative speech and language services for students with learning disabilities. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 30(4), 414–426.

- Emmel, N., Greenhalgh, J., Manzano, A., Monaghan, M., & Dalkin, S. (Eds.). (2018). Doing realist research. London, UK: SAGE.

- Fereday, J., & Muir-Cochrane, E. (2016). Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5(1), 80–92.

- Fick, F., & Muhajarine, N. (2019). First steps: Creating an initial program theory for a realist evaluation of healthy start-départ santé intervention in childcare centres. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 22(6), 545–556.

- Flynn, P., & Power-defur, L. (2013, November 14-16). Collaboration in schools: Let the magic begin! ASHA Convention, Chicago, IL.

- Gilmore, B., McAuliffe, E., Power, J., & Vallières, F. (2019). Data analysis and synthesis within a realist evaluation: Toward more transparent methodological approaches. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 18, 1609406919859754.

- Government of Canada. (2018). Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans-TCPS 2. https://ethics.gc.ca/eng/policy-politique_tcps2-eptc2_2018.html

- Grether, S. M., & Sickman, L. S. (2008). AAC and RTI: Building classroom-based strategies for every child in the classroom. Seminars in Speech and Language, 29(2), 155–163.

- Gustafson, S., Svensson, I., & Fälth, L. (2014). Response to intervention and dynamic assessment: Implementing systematic, dynamic and individualised interventions in primary school. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 61(1), 27–43.

- Hadley, P. A., Simmerman, A., Long, M., & Luna, M. (2000). Facilitating language development for inner-city children: Experimental evaluation of a collaborative, classroom-based intervention. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 31(3), 280–295.

- Heyder, A., Südkamp, A., & Steinmayr, R. (2020). How are teachers’ attitudes toward inclusion related to the social-emotional school experiences of students with and without special educational needs? Learning and Individual Differences, 77, 101776.

- Horn, E., & Banerjee, R. (2009). Understanding curriculum modifications and embedded learning opportunities in the context of supporting all children’s success. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 40(4), 406–415.

- Hutton, E. (2009). Occupational therapy in mainstream primary schools: An evaluation of a pilot project. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 72(7), 308–313.

- Hutton, E., Tuppeny, S., & Hasselbusch, A. (2016). Making a case for universal and targeted children’s occupational therapy in the United Kingdom. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 79(7), 450–453.

- Idol, L., Paolucci-Whitcomb, P., & Nevin, A. (2010). The collaborative consultation model. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 6(4), 329–346.

- Jackson, S., Pretti-Frontczak, K., Harjusola-Webb, S., Grisham-Brown, J., & Romani, J. M. (2009). Response to intervention: Implications for early childhood professionals. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 40(4), 424–434.

- Jagosh, J. (2020a). Retroductive theorizing in Pawson and Tilley’s applied scientific realism. Journal of Critical Realism, 19(2), 121–130.

- Jagosh, J. (2020b, May 16). Public health architecture and realist methodology [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3rqyrS1NVSs&feature=youtu.be

- Jagosh, J., Macaulay, A. C., Pluye, P., Salsberg, J., Bush, P. L., Henderson, J., … Greenhalgh, T. (2012). Uncovering the benefits of participatory research: Implications of a realist review for health research and practice. Milbank Quarterly, 90(2), 311–346.

- Jefford, M., Stockler, M. R., & Tattersall, M. H. (2003). Outcomes research: What is it and why does it matter? Internal Medicine Journal, 33(3), 110–118.

- Johnson, C. D. (2012). Classroom listening assessment: Strategies for speech-language pathologists. Seminars in Speech and Language, 33(4), 322–339.

- Justice, L. M. (2006). Evidence-based practice, response to intervention, and the prevention of reading difficulties. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 37(4), 284–297.

- Justice, L. M., & Kaderavek, J. N. (2004). Embedded-explicit emergent literacy intervention I: Background and description of approach. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 35(3), 201–211.

- Justice, L. M., McGinty, A., Guo, Y., & Moore, D. (2009). Implementation of responsiveness to intervention in early education settings. Seminars in Speech and Language, 30(2), 59–74.

- Kaelin, V. C., Ray-Kaeser, S., Moioli, S., Kocher Stalder, C., Santinelli, L., Echsel, A., & Schulze, C. (2019). Occupational therapy practice in mainstream schools: Results from an online survey in Switzerland. Occupational Therapy International, 2019, 3647397.

- Kennedy, J., Missiuna, C., Pollock, N., Wu, S., Yost, J., & Campbell, W. (2018). A scoping review to explore how universal design for learning is described and implemented by rehabilitation health professionals in school settings. Child: Care, Health and Development, 44(5), 670–688.

- Kennedy, J. N., Missiuna, C. A., Pollock, N. A., Sahagian Whalen, S., Dix, L., & Campbell, W. N. (2019). Making connections between school and home: Exploring therapists’ perceptions of their relationships with families in partnering for change. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 83(2), 98–106.

- Kerins, M. (2018). Promoting interprofessional practice in schools. The ASHA Leader, 23, 12.

- Klang, N., Göransson, K., Lindqvist, G., Nilholm, C., Hansson, S., & Bengtsson, K. (2019). Instructional practices for pupils with an intellectual disability in mainstream and special educational settings. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 67(2), 151–166.

- Knackendoffel, A., Dettmer, P., & Thurston, L. P. (2018). Collaboration, consultation, and teamwork for students with special needs (8th ed.). New York, NY: Pearson.

- Krischler, M., Powell, J. J. W., & Pit-Ten Cate, I. M. (2019). What is meant by inclusion? On the effects of different definitions on attitudes toward inclusive education. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 34(5), 632–648.

- Lacouture, A., Breton, E., Guichard, A., & Ridde, V. (2015). The concept of mechanism from a realist approach: A scoping review to facilitate its operationalization in public health program evaluation. Implementation Science, 10(1), 153.

- Lavin, C. E., Francis, G. L., Mason, L. H., & LeSueur, R. F. (2020). Perceptions of inclusive education in Mexico City: An exploratory study. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 1–15. doi:10.1080/1034912x.2020.1749572

- Law, J., Reilly, S., & Snow, P. C. (2013). Child speech, language and communication need re-examined in a public health context: A new direction for the speech and language therapy profession. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 48(5), 486–496.

- Li, K. M., & Cheung, R. Y. M. (2019). Pre-service teachers’ self-efficacy in implementing inclusive education in Hong Kong: The roles of attitudes, sentiments, and concerns. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 1–11. doi:10.1080/1034912x.2019.1678743

- Linan-Thompson, S., & Ortiz, A. A. (2009). Response to intervention and english-language learners: Instructional and assessment considerations. Seminars in Speech and Language, 30(2), 105–120.

- Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: SAGE.

- Marchal, B., Kegels, G., & Van Belle, S. (2018). Theory and realist methods. In N. Emmel, J. Greenhalgh, A. Manzano, M. Monaghan, & S. Dalkin (Eds.), Doing realist research (pp. 79–89). London, UK: SAGE.

- McColl, M. A., Law, M. C., & Stewart, D. (2015). Theoretical basis of occupational therapy (3rd ed.). Thorofare, NJ: SLACK.

- McCrimmon, A. W. (2014). Inclusive education in Canada. Intervention in School and Clinic, 50(4), 234–237.

- Merton, R. K. (1967). On theoretical sociology: Five essays, old and new. New York, NY: he Free Press.

- Mills, C., & Chapparo, C. (2018). Listening to teachers: Views on delivery of a classroom based sensory intervention for students with autism. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 65(1), 15–24.

- Mire, S. P., & Montgomery, J. K. (2008). Early intervening for students with speech sound disorders. Communication Disorders Quarterly, 30(3), 155–166.

- Missiuna, C., Campbell, W., Dix, L., Pollock, N., Bennett, S., Stewart, D., … Cairney, J. (2015). Partnering for change: An innovative service for integrated rehabilitation services [Webinar]. CanChild. https://srs-mcmaster.ca/library/p4c_webinar/presentation_html5.html

- Missiuna, C., Hecimovich, C. A., Pollock, N., Bennett, S., Campbell, W., Camden, C., … Song, K. (2015). Partnering for change. www.partneringforchange.ca

- Missiuna, C., Pollock, N., Campbell, W., DeCola, C., Hecimovich, C., Sahagian Whalen, S., … Camden, C. (2016). Using an innovative model of service delivery to identify children who are struggling in school. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 80(3), 145–154.

- Missiuna, C., Pollock, N., Campbell, W. N., Bennett, S., Hecimovich, C., Gaines, R., … Molinaro, E. (2012). Use of the medical research council framework to develop a complex intervention in pediatric occupational therapy: Assessing feasibility. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 33(5), 1443–1452.

- Missiuna, C., Pollock, N., Levac, D., Campbell, W., Whalen, S., Bennett, S., … Russell, D. (2012). Partnering for change: An innovative school-based occupational therapy service delivery model for children with developmental coordination disorder. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. Revue Canadienne D’Ergothérapie, 79(1), 41–50.

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G.; PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ, 339, b2535.

- Nilsen, P. (2015). Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implementation Science, 10, 53.

- Ohl, A. M., Graze, H., Weber, K., Kenny, S., Salvatore, C., & Wagreich, S. (2013). Effectiveness of a 10-week tier-1 response to intervention program in improving fine motor and visual-motor skills in general education kindergarten students. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 67(5), 507–514.

- Page, A., Mavropoulou, S., & Harrington, I. (2020). Culturally responsive inclusive education: The value of the local context. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 1–14. doi:10.1080/1034912x.2020.1757627

- Paul, D. R., Blosser, J., & Jakubowitz, M. D. (2006). Principles and challenges for forming successful literacy partnerships. Topics in Language Disorders, 26(1), 5–23.

- Pawson, R. (2006). Evidence-based policy: A realist perspective. London, UK: SAGE.

- Pawson, R., Greenhalgh, T., Harvey, G., & Walshe, K. (2005). Realist review: A new method of systematic review designed for complex policy interventions. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 10(1), 21–34.

- Peña, E. D., & Quinn, R. (2003). Developing effective collaboration teams in speech-language pathology. Communication Disorders Quarterly, 24(2), 53–63.

- Pfeiffer, D. L., Pavelko, S. L., Hahs-Vaughn, D. L., & Dudding, C. C. (2019). A national survey of speech-language pathologists’ engagement in interprofessional collaborative practice in schools: Identifying predictive factors and barriers to implementation. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 50(4), 639–655.

- Pollock, N. A., Dix, L., Whalen, S. S., Campbell, W. N., & Missiuna, C. A. (2017). Supporting occupational therapists implementing a capacity-building model in schools. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. Revue Canadienne D’Ergothérapie, 84(4–5), 242–252.

- QSR International. (2018). NVivo 11. https://www.qsrinternational.com/.

- Ratzon, N. Z., Lahav, O., Cohen-Hamsi, S., Metzger, Y., Efraim, D., & Bart, O. (2009). Comparing different short-term service delivery methods of visual-motor treatment for first grade students in mainstream schools. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 30(6), 1168–1176.

- Reeder, D. L., Arnold, S. H., Jeffries, L. M., & McEwen, I. R. (2011). The role of occupational therapists and physical therapists in elementary school system early intervening services and response to intervention: A case report. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics, 31(1), 44–57.

- Regan, S., Orchard, C., Khalili, H., Brunton, L., & Leslie, K. (2015). Legislating interprofessional collaboration: A policy analysis of health professions regulatory legislation in Ontario, Canada. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 29(4), 359–364.

- Reid, L., Bennett, S., Specht, J., White, R., Somma, M., Li, X., … Patel, A. (2018). If inclusion means everyone, why not me? https://www.inclusiveeducationresearch.ca/docs/why-not-me.pdf

- Richards, L. (2009). Handling qualitative data. London, UK: SAGE.

- Ritter, R., Wehner, A., Lohaus, G., & Krämer, P. (2020). Effect of same-discipline compared to different-discipline collaboration on teacher trainees’ attitudes towards inclusive education and their collaboration skills. Teaching and Teacher Education, 87, 102955.

- Ritzman, M. J., Sanger, D., & Coufal, K. L. (2006). A case study of a collaborative speech-language pathologist. Communication Disorders Quarterly, 27(4), 221–231.

- Rodriguez, A. D., & Gonzalez Rothi, L. J. (2009). Even broken clocks are right twice a day: The utility of models in the clinical reasoning process. Advances in Speech Language Pathology, 8(2), 120–123.

- Roth, F. P., & Troia, G. A. (2009). Applications of responsiveness to intervention and the speech-language pathologist in elementary school settings. Seminars in Speech and Language, 30(2), 75–89.

- Sanger, D., Mohling, S., & Stremlau, A. (2011). Speech-language pathologists’ opinions on response to intervention. Communication Disorders Quarterly, 34(1), 3–16.

- Shaw, J., Gray, C. S., Baker, G. R., Denis, J. L., Breton, M., Gutberg, J., … Wodchis, W. (2018). Mechanisms, contexts and points of contention: Operationalizing realist-informed research for complex health interventions. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(1), 178.

- Siegert, R. J., McPherson, K. M., & Dean, S. G. (2005). Theory development and a science of rehabilitation. Disability and Rehabilitation, 27(24), 1493–1501.

- Silliman, E. R., Ford, C. S., Beasman, J., & Evans, D. (1999). An inclusion model for children with language learning disabilities: Building classroom partnerships. Topics in Language Disorders, 19(3), 1–18.

- Soto, G., Mu Ller, E., Hunt, P., & Goetz, L. (2001). Professional skills for serving students who use AAC in general education classrooms: A team perspective. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 32(1), 51–56.

- Soto Torres, Y. (2018). Safe and inclusive schools: Inclusive values found in Chilean teachers’ practices. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 24(1), 89–102.

- Staskowski, M., & Rivera, E. A. (2005). Speech-language pathologists’ involvement in responsiveness to intervention activities: A complement to curriculum-relevant practice. Topics in Language Disorders, 25(2), 132–147.

- The World Bank. (2017). World Bank country and lending groups. https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups

- Throneburg, R. N., Calvert, L. K., Sturm, J. J., Paramboukas, A. A., & Paul, P. J. (2000). A comparison of service delivery models: Effects on curricular vocabulary skills in the school setting. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 9(1), 10–20.

- Troia, G. A. (2005). Responsiveness to intervention: Roles for speech-language pathologists in the prevention and identification of learning disabilities. Topics in Language Disorders, 25(2), 106–119.

- United Nations. (2006). Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities. https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities.html

- Veritas Health Information. (2018). Covidence systematic review software. http://www.covidence.org/

- Villeneuve, M. (2009). A critical examination of school-based occupational therapy collaborative consultation. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. Revue Canadienne D’Ergothérapie, 76, 206–218.

- Villeneuve, M. A., & Shulha, L. M. (2012). Learning together for effective collaboration in school-based occupational therapy practice. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. Revue Canadienne D’Ergothérapie, 79(5), 293–302.

- Waldron, T., Carr, T., McMullen, L., Westhorp, G., Duncan, V., Neufeld, S. M., … Groot, G. (2020). Development of a program theory for shared decision-making: A realist synthesis. BMC Health Services Research, 20(1), 59.

- Whyte, J. (2014). Contributions of treatment theory and enablement theory to rehabilitation research and practice. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 95(1 Suppl), S17–23 e12.

- Wilson, A. L., & Harris, S. R. (2018). Collaborative occupational therapy: Teachers’ impressions of the Partnering for Change (P4C) model. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics, 38(2), 130–142.

- Wintle, J., Krupa, T., Cramm, H., & DeLuca, C. (2017). A scoping review of the tensions in OT-teacher collaborations. Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools, & Early Intervention, 10(4), 327–345.

- Wong, G., Greenhalgh, T., Westhorp, G., Buckingham, J., & Pawson, R. (2013). RAMESES publication standards: Realist syntheses. BMC Medicine, 11(1), 21.

- Wong, G., Westhorp, G., Manzano, A., Greenhalgh, J., Jagosh, J., & Greenhalgh, T. (2016). RAMESES II reporting standards for realist evaluations. BMC Medicine, 14(1), 96.

- World Health Organization. (2010). Framework for action on interprofessional education and collaborative practice. https://www.who.int/hrh/resources/framework_action/en/