ABSTRACT

This review focuses on answering the research question: What can we learn from studies of interventions to address the implementation of inclusive education of students with disabilities in low- and lower middle-income countries? A systematic literature review was conducted to identify studies focused on interventions aiming to improve inclusive education in low- and lower-middle-income countries. The searches returned 1,266 studies for a title and abstract review. Only 31 studies evaluated interventions and included 20 or more respondents. Published between 2000 and 2019, these studies estimate the impact of a number of approaches that can be used to increase support for students with disabilities in general education settings including teacher trainings, improving facilities and educational materials, and forming partnerships within the community. Covering 19 of 84 low- and lower-middle-income countries, this systematic review underscores the limited amount of work on this critical topic and the need for further research.

Introduction

Few concepts have had the same influence on education in the last 30 years, as ‘inclusion’ of students with disabilities (Chong & Graham, Citation2017). The merits of inclusive education are no longer debated as they were previously (Artiles & Kozleski, Citation2016), but the theoretical and practical questions around its implementation persist (Amor et al., Citation2019; Schuelka & Engsig Citation2020; Reeves, Ng, Harris, & Phelan, Citation2020). The right to inclusive education is recognised by the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UN General Assembly, Citation2006) and the Sustainable Development Goals (UN General Assembly, Citation2015). As of 2020, 164 countries have signed the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). However, despite the support and the policies written to this end, the implementation of these goals has proven much more difficult in practice (Mittler, Citation2015). It is especially difficult to implement in resource constrained settings.

This study focuses on answering the following research questions:

What research is available on interventions to address the implementation of inclusive education of students with disabilities in low- and lower-middle-income countries?

What can we learn about potential approaches for improving implementation in low- and lower-middle-income countries from studies of interventions?

As noted in previous work, research studies can support evidence-based disability and policy evaluation (Sherlaw, Lucas, Jourdain, & Monaghan, Citation2014). Furthermore, previous research has shown that policymakers can learn from the successes and challenges of the policies and practice of other countries (Kim & Fox, Citation2011). We recognise the inability to universalise the best solutions (Grech, Citation2009); however, we also seek to gain a deeper understanding of potential interventions and to provide policymakers and stakeholders with a survey of what is possible.

This research builds on other important literature reviews of inclusive practices. Previous research has focused on teaching practices (Lindner & Schwab, Citation2020), projects in primary schools (Srivastava, de Boer, & Pijl, Citation2015a), the scope of published articles (Amor et al., Citation2019), and interventions for keeping students with disabilities in general education in Western countries (Reichrath, de Witte, & Winkens, Citation2010). To be as comprehensive as possible, we used a broad definition of inclusive education (IE). Search criteria were designed to include any program where at least some students are with their peers in the general education classroom and where additional policies, services and practices are in place to support inclusion.

Methods

Focus on Interventions

This review specifically addresses interventions that are actively seeking to improve inclusion. It focuses on interventions, or practices, that are promoting both policy and programmatic changes to increase the full participation of students with disabilities in education.

Determination of Inclusion

For feasibility and to provide as comprehensive a review of the literature as possible, we use Griffiths’ (2015) definition of inclusion which defines IE as any policy, strategy or practice that is intending for learners to participate fully in general education. This broad definition allows us to look at all types of interventions that are promoting elements of IE through policies and practices.

To apply this, we begin with the author definition of inclusion to get the broadest list of possible studies. This process can be seen in our search strategy. This initial large group of studies was analysed and in any case where authors used the term inclusion but students were in exclusive segregated settings, we did not include those studies. We include studies that may not have all the elements of inclusion and we review any program that included elements of the inclusion described in the CRPD: content, teaching methods, approaches, structures, strategies or environment (United Nations General Assembly, Citation2006).

Search Procedure

From June to August 2019, a review was conducted of research in English focused on the implementation of IE in low- and lower-middle-income countries since 2000. This research focused on intervention studies after 2000 to look at a more current context of implementing these interventions. Literature was obtained by searches in scholarly databases, specifically Ebscohost, Education Source, ERIC, Academic Search Complete, Google Scholar, Web of Science, World Bank eLibrary, UNESCO digital library, Proquest and Oxford Handbooks Online. The main search terms used were ‘inclusive education’ and the names of low- and lower-middle income countries. The list of low- and lower-middle-income countries was retrieved from the Atlas of sustainable development goals issued by the World Bank (Citation2018). In order to look for studies measuring the effect of this implementation, the additional terms such as ‘disabil* or disabl* or special education’ and ‘implement* or interv* or pilot’ and ‘eval* or impact or effect* or outcome*’ and ‘inclusive education’ were used. The references of relevant literature reviews and studies were used to find additional sources.

The searches resulted in a total of 1,266 studies. From these searches, a title-abstract review was conducted to determine whether the study was focused on an intervention addressing the implementation of IE. Studies that were focused on an intervention for policy implementation were then pulled for further review. Throughout the focus and methodology review of the 120 pulled studies, an additional eight studies were found. Again, in the interest of being as comprehensive as possible, when one of the studies pulled referenced a study that was evaluating an intervention for implementation, that study was also pulled for further review. Clear exclusion criteria were used to eliminate articles not aligned with the focus of the review. Studies focused exclusively on attitudes towards IE (with no feedback on implementation), pre-service teachers (not yet working in classrooms), readiness of schools to implement IE, programs that maintained students with disabilities in separate settings, experiences of people with disabilities not specific to their education, studies detailing the state of inclusion, and outlines of programs offered were not included. Both quantitative and qualitative studies are included to learn from as many interventions as possible; however, studies that included a sample of less than 20 participants were eliminated from review.

Studies were included in this review if they were done in non-segregated settings in an area that is presently implementing elements of IE. The methods section must have clearly outlined sampling, data collection and analysis with either a description of the analysis or multiple data points to triangulate the findings. If studies did not include a description of the sampling, data collection and analysis – or if qualitative, multiple ways that data were collected to triangulate the findings – they were also excluded for methodological reasons. 31 articles met these criteria.

The reviewed studies used a number of different terms in discussing the implementation of IE. There are 20 studies that acknowledge the declarations and vision of the United Nations in the discussion and implementation of IE. They reference the CRPD, Salamanca, Sustainable Development Goals, Millennium Development Goals, and the Convention on the Rights of the Child among others. These studies used a variety of terms in discussing students with disabilities. The terms used include children with disabilities (CWD), students with disabilities (SWD), people with disabilities (PWD), special educational needs (SEN), and learners with special educational needs (LSEN). Some studies did address the specific impairments of people included within the studies. These included physical, visual, hearing, and specific learning disabilities (SpLD). For the purpose of this review, students with disabilities will be used when discussing outcomes. When appropriate, more specific terms will be used.

Results

There were 31 studies found that met the criteria of a study of an intervention for the implementation of IE, with at least 20 respondents, conducted in a low or lower middle income country, and published between 2000 and 2019. These studies used a number of different methodologies but only six studies examined an intervention with a pre- and post-test assessment. One study completed a pre- and mid-point test for intervention effect and one study did conduct questionnaires pre- and post-intervention that were analysed qualitatively. Four studies used a control group to compare effect of an intervention. The 31 studies are focused on a range of school levels including preschool, primary, secondary, and technical and vocation education training (TVET). Several of these studies look at a mix of schooling levels while others focus specifically on one part of school. There are 10 studies looking at primary schools and two that are concerned with secondary schools. There is also one study focused on preschool and one focused on TVET.

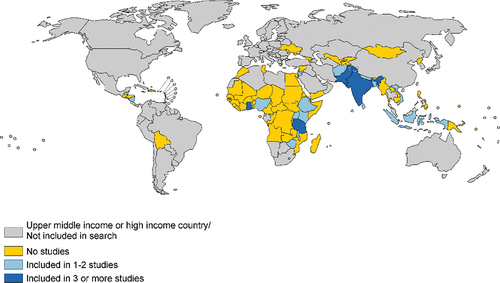

The 31 studies examined programs in 19 low- or lower-middle-income countries. The countries with the most study representations are India with five, followed by Ghana with four. Out of the 84 low- and lower-middle-income countries searched for in this review, 65 had no research studies meeting inclusion criteria (see Map in ).

Study Outcomes

The 31 studies will be reported below in the following categories: teaching, school conditions, partnerships, programs to promote inclusion, and transition. For each type of intervention, tables have been created that provide information about the study, intervention and its outcomes. Tables that summarise the methods and findings for each study can be seen in . A more complete description of the research methodology, findings and limitations for each study can be found in the supplemental materials.

Table 1. Teachers: Teacher Training.

Table 2. Teachers: Curriculum and Instruction.

Table 3. School Conditions: Facilities and Resources.

Table 4. School Conditions: Moving to Increased Integration and Inclusion.

Table 5. Programs focused on Inclusion within the Community and Schools.

Table 6. Partnerships.

Table 7. Transition.

Teaching

There are two types of teaching interventions included within this study. These include those focused on curriculum and teaching practice and those focused on teacher training for inclusive practices.

Teacher Training

Of the six teacher training programs implemented, five saw an improvement in their target elements of IE including teacher attitudes, concerns related to inclusion, self-efficacy, knowledge of disabilities and or teaching strategies. These studies employed lectures, PowerPoints, videos, handouts, discussions and projects (Carew, Deluca, Groce, & Kett, Citation2019; Delkamiller, Swain, Ritzman, & Leader-Janssen, Citation2016; Kurniawati, de Boer, Minnaert, & Mangunsong, Citation2017; Sibtain, Citation2013; Srivastava, de Boer, & Pijl, Citation2015b). The time spent in each training varied greatly, from a ten-hour workshop to a two-year training program. Four of the five positive training studies target teacher attitudes towards the inclusion of students with disabilities. Again, these studies do not point to one instructional method or length of time (Carew et al., Citation2019; Kurniawati et al., Citation2017; Sibtain, Citation2013; Srivastava et al., Citation2015b). These four studies did see an improvement in attitudes towards inclusion, but two of these studies note that this does not translate to change in measures of behaviour or intentions of adopting practices (Carew et al., Citation2019; Kurniawati et al., Citation2017).

Finally, a study in Zimbabwe interviewed teachers with extensive experience with IE including a bachelor’s in a special education related field and at least 5 years of experience including children with disabilities in primary school classrooms. The study found that all 24 primary teachers interviewed describe four competencies necessary for teaching students with disabilities in general education settings. These include screening and assessment, differentiation of instruction, classroom and behaviour management, and collaboration; the study was designed with the intention of using these competencies as a baseline for future teacher training (Majoko, Citation2019). See .

Curriculum and Instruction

Studies examined possible choices for teaching strategies and curriculum. In considering teacher strategies for providing support and education to students with disabilities within the classroom, several approaches, including small group instruction, were highlighted. A study from Indonesia compared ‘Cluster-Based Instruction (CBI)’ (a mixture of whole group, small group and individualised instruction) to ‘Full Inclusive Instruction (FII)’ (whole group instruction) and found that CBI had a significant positive effect on achievement in mathematics when compared to FII (Gunarhadi, Anwar, Andayani, & Shaari, Citation2016). Another study implemented a program for first graders that provided small group and individualised instruction for one year to students who scored less than 70% on an initial assessment. Researchers saw improvements in mean differences of 27 percentage points or more from pre to post scores (Stone-Macdonald & Fettig, Citation2019).

Aside from teaching strategies, one study addressed choices made in the provision of curriculum. This study from India examined a policy of curriculum choices in junior colleges and the effects of these choices on students with disabilities entering collegiate maths classes (Eichhorn, Citation2016). The student and faculty participants reported that current practices are not developing students with disabilities’ maths skills for post-secondary mathematics because the curricular choices do not ensure that students with disabilities take the maths classes they need to be prepared. See .

School Conditions

There are two types of interventions focused on school conditions. These include studies focused on the facilities and resources and studies focused on pilot schools, programs and classrooms that are moving to increased integration and inclusion of students with disabilities.

Facilities and Resources

With regards to facilities and materials, researchers focused on classroom resources, school facilities, human resources and support for students with disabilities. From interviews with parents and teachers, participants reported a lack of teaching and learning resources for preschool teachers and 97% of the 334 participants agreed that resources influenced the implementation of IE (Okongo, Ngao, Rop, & Nyongesa, Citation2015). In a study of water and sanitation facilities for students with disabilities in Uganda and Malawi, researchers found that only seven of the 41 schools surveyed provided these facilities for students with disabilities (Erhard, Degabriele, Naughton, & Freeman, Citation2013). In another study, researchers find that facilities and materials are related to academic performance in public secondary schools in Nigeria. A chi-square analysis was used to understand the relationship between academic performance and facilities equipped for students with disabilities and included scores from school observation checklists and examination records of 910 students with hearing impairments, physical impairments and visual impairments. The analysis found a significant correlation between the academic performance on examination records and the facilities (Oluremi & Olubukola, Citation2013). Still, one more study focused on the relationship between successful IE practice and the amount of materials, mindset towards inclusion, and human resources (Adeniyi, Owolabi, & Olojede, Citation2015). This survey study of 227 teachers revealed a significant relationship in a multivariate regression between materials, human resources, mindset and IE practice. In fact, the highest relationship, significant at 0.05, was found between materials and successful IE practice.See .

Moving to Increased Integration and Inclusion

Ten studies focused on the varying degrees of integrating students within general education and the outcomes of those policies, programs and pilots. Three of those studies focused on degrees of integration for students with disabilities. They address integrated and segregated settings and resource rooms. In both studies that compared integrated and segregated settings, neither study was conclusive in findings. In a study of parent satisfaction with programs in Jordan, about 50% of the 22 parents with children in segregated settings were most satisfied with educational services, while the 19 parents with children in integrated settings were mixed in their response to educational services. Several felt these services were suitable but others noted traditional teaching methods and lack of student progress as reasons for concern (Al-Dababneh, Citation2016). A study of integrated and segregated settings for students with visual impairments in Ghana, examined how students in both environments were progressing in mobility, social, and academic skills. Researchers interviewed six current students, four past students, eight teachers and nine parents from each program and the impact of the programs was not clear-cut. A majority of students from both programs reported ability to attend school independently, being active in school activities, and average performance in academics (Agbeke, Citation2005). A study from Jordan focused on another degree of integrated education, the resource room, which provides small group services to students in general education settings. These researchers found a high level of satisfaction for the 190 mothers of students and a medium to low level of satisfaction for teachers in resource rooms. The mothers who participated in the study were most satisfied with their children’s improvement in academic performance. The 135 resource room teachers surveyed were most satisfied with their job and least satisfied with their salary (Alkhateeb & Hadidi, Citation2009).

Two studies noted positive outcomes through integration. A study of teachers in Ghana found that teachers in the Integrated Education Program are amenable to IE and informed about policy (Ocloo & Subbey, Citation2008). A study of 20 teachers from model inclusive schools in Pakistan, teachers noted positive changes academically for all students in the sample of model schools integrating students with disabilities (Uzair-ul-Hassan, Hussain, Parveen, & De Souza, Citation2015). Still, both studies included findings that showed a lack of training for teachers (Ocloo & Subbey, Citation2008; Uzair-ul-Hassan et al., Citation2015).

Multiple studies of integration found a lack of support to accessing education in integrated settings. In a study in Tanzania 10 out of 10 head teachers reported lack of trained teachers and a lack of learning facilities in inclusive schools. In fact, the majority of teachers in focus groups reported they did not favour IE citing lack of needed materials or productivity and fear of disturbing the classroom (Tungaraza, Citation2014). Observations completed in Lesotho revealed a lack of inclusive practices in the classroom by teachers working in general and special education showed evidence of integrated education and not IE (Mosia, Citation2014). Furthermore, in another study within Lesotho, researchers examined pilot schools and newly registered ‘Special Education Unit’ schools that had been trained on IE approaches for students with disabilities in general education settings. The study provides an example of how the degree of inclusion is different in observation than in description. The 130 teachers surveyed rated themselves with a mean of 8.06, with 10 representing a high level of inclusion. However, researchers who completed observations of 20 teachers did not see instruction of students with disabilities as part of an approach to teaching but as something completed in teacher free time (Johnstone & Chapman, Citation2009). Finally, a study of 11 schools in India found that 40% of teachers did not change their teaching practices after the head of school implemented integrated education for students with disabilities. The students with disabilities were given access to but not fully included in general education classrooms (Singal, Citation2008).See .

Programs Focused on Inclusion within the Community and Schools

The programs included in this section include interventions focused on promoting inclusion through community and school reform. In a program in India to support students with disabilities in general education through community mobilisation, improved school infrastructure, and effective systems of response to students with disabilities, 98% of the 568 surveyed students with disabilities like attending schools and 97% of the 568 surveyed peers report being friends with a student with a disability (Chadha, Citation2007).

There are also multiple lessons that can be learned from these interventions about the needs for greater supports in providing education to students with disabilities in general education settings. In the study within India, 85% of the 419 teachers report they are not getting enough support. In Ghana, ‘inclusive project’ schools had focused on community awareness, teachers, facilities and materials in interest of providing access, retention and participation for students with disabilities in general education settings (Agbenyega, Citation2007). This included teacher training but the study found that a comparison of teacher attitudes in ‘inclusive project’ and non-project schools found no difference in scales focused on behavioural issues, student needs, resource issues and professional competency. Researchers hypothesised this finding may be due to lack of preparation, support and resources, and could also be due to a lack of involvement of teachers in designing the program. See .

Partnerships

Four studies focused on the partnerships created between stakeholders, or the people involved in the implementation of IE. These included studies focused on increasing social accountability (Trani et al., Citation2019), creating community support (Villa et al., Citation2003), development of plans for inclusion (Polat, Citation2011) and an increase in stakeholder technical skills (Beutel, Tangen, & Carrington, Citation2019). These studies show that programs can be implemented to create inclusion plans and measurement tools through community and stakeholder participation. These development plans and measurement tools can be created in different ways. In a study done with stakeholders (NGO and government workers) from Nepal, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh, a training held in Australia focused on return to work plans (Beutel et al., Citation2019). The training created a change in the way these stakeholders viewed inclusion as a systemic issue and allowed for continued partnerships after training as stakeholders continued implementing their plans. One study in Pakistan and Afghanistan sought to develop mechanisms for monitoring school implementation of services for students with disabilities and found group workshops were a method for creating action items and training community members (Trani et al., Citation2019). Finally, a study in Tanzania encouraged schools to create teams of teachers and parents interested in making Whole School Development Plans for the implementation of integration of students with disabilities in primary schools. The researchers found trends in the teams’ priorities for improvement including need for improved teaching and environment, academic performance, enrolment of students with disabilities, and stronger community campaigns against HIV (Polat, Citation2011). Additionally, community engagement can impact different areas of community inclusion. In an expansion of a Community Support program for students with disabilities in Viet Nam, researchers reported six areas of impact including improvements in community awareness, development of local infrastructure, quality of teaching and family support (Villa et al., Citation2003). These programs provide opportunities for multiple stakeholders to be involved and for goals to be context-specific. They show that through programs aimed at greater community engagement goals can be created and improvements in integration of students with disabilities can be accomplished. See .

Transition

Two studies focus on transition to higher education and employment and address the educational experiences of youth and adults with disabilities. In the study focused on students with disabilities in Ethiopia, researchers found several limiting factors for inclusion in vocational education including lack of preparedness, lack of accessibility, and need for adapted facilities and pedagogies (Malle, Pirttimaa, & Saloviita, Citation2015). In reflecting on employment in Ghana, people with disabilities with varying levels of education noted the importance of school in gaining skills for employment. The youth and adult participants saw the benefits of education as both social and academic (Singal, Salifu, Iddrisu, Casely-Hayford, & Lundebye, Citation2015). See .

Study Implications

The studies in this review provide an opportunity to learn from those who are currently implementing IE. There are seven implications repeated throughout these studies that provide key points for implementation of IE in the future: stronger and more explicit policy and legislation (6), resources and funding provided to schools (22), reformed teacher education pre-service and in-service trainings (17), expanded collaboration and voice to local stakeholders (11), goals and indicators for inclusion that are specific to the local context (4), incentives as a motivation for implementing IE (3), and more research (8).

Discussion

The 31 studies within this review, published between 2000 and 2019, also demonstrated a number of interventions that can be used for increased support for students with disabilities in general education settings including training for teachers, facilities and materials, and partnerships within the community. Five of the studies with pre and mid, or post design assessments evaluated teacher trainings. Those five teacher training programs saw an improvement in their target elements of IE including teacher attitudes, concerns related to inclusion, self-efficacy, knowledge of disabilities and/or teaching strategies. These studies employed lectures, PowerPoints, videos, handouts, discussions, and projects (Carew et al., Citation2019; Delkamiller et al., Citation2016; Kurniawati et al., Citation2017; Sibtain, Citation2013; Srivastava et al., Citation2015b). The evaluations of these interventions show the effect that a number of different forms of teacher trainings can have on teacher attitudes and knowledge and the positive effect of tailored instruction.

Furthermore, studies focused on instruction interventions found positive effects on achievement. ‘Cluster-Based Instruction (CBI)’ (a mixture of whole group, small group and individualised instruction) had a significant positive effect on achievement in mathematics when compared to ‘Full Inclusive Instruction (FII)’ (whole group instruction) (Gunarhadi et al., Citation2016). Also, a study focused on small group and individualised instruction for first graders, saw improvements in mean differences of 27 points or more from pre to post scores over the three year project (Stone-Macdonald & Fettig, Citation2019). These studies demonstrated the benefit of including small groups and individualised instruction as part of IE in low- and lower-middle income countries.

This study presents the first systematic review of interventions to improve IE for students with disabilities in low- and lower-middle income countries. The research revealed limitations of the education for students with disabilities in multiple geographies. Two studies found integrated education but not IE was being provided (Johnstone & Chapman, Citation2009; Mosia, Citation2014); students with disabilities had access to classrooms with their peers but their needs were not being met (Bowen & Ellis, Citation2009). In another study, Singal (Citation2008) found that although students with disabilities were given access to general education settings, they were not always fully included within the classroom. This review found barriers to IE that include need for increased funding and lack of specific policies and definition of inclusion, teacher training, resources, materials and/or access to buildings.

Still, it was striking that despite a broad search that used wide ranging terms to find all studies on implementation that were published in English since 2000, only 31 studies carried out in low- and lower-middle income countries were found. Given the importance of IE in the fight for equitable education, the agreement of 164 countries to the CRPD, and the challenges of IE in practice, this underscores the need for more research. Moreover, of these 31 studies, only six had a pre and post design to evaluate the intervention, two used some version of a pre-test with analysis following part of the intervention, and four studies used a match group. While each of these studies raised important questions around implementation, the paucity of evaluations of interventions that include data from before and after, or control groups, contributes to our limited knowledge of what is most effective. Nonetheless, these studies do provide important insights into areas that are worthy of further research. The limited number of studies underscores a larger issue of funding for research in low and lower-middle income countries. It is important that research moves beyond high-income countries to include a variety of contexts (Grech, Citation2009).

There are limitations of this review. Resource constraints limited the reviews to English language literature. The criteria for inclusion in the review required studies to detail rigorous study methods, and be focused on students with disabilities being educated in the general education system. These criteria ensured minimum standards but may have excluded some studies providing insights and generating hypotheses. Despite the limitations of our criteria, we specifically chose broad search terms and a definition of IE that allowed for any research applying elements of IE with the purpose of conducting a more extensive review.

There are also several limitations to the research studies themselves. Although these studies focus on the implementation of IE, not every study is conducting an experiment with an intervention and measured outcomes. Of the studies that did assess or evaluate programs or interventions, four used a control group and 10 did not. There were also a few limitations related to sampling, including a lack of clarity related to the sample (3). These limitations have been included within the tables in supplemental materials so that the limits of each intervention and its accompanying study are clear. From a critical perspective, these studies were also limited by their lack of input from students with disabilities. Only 11 studies provided opportunity for their participation in this research. Finally, these studies do raise questions regarding replicability. In a review of this literature, there were no replication studies, although many were piloting programs with the intent of growing the intervention. Without a clear understanding of the ability to replicate these, the context and sample have been included in the very first column of the tables in supplemental materials. This is to ensure that the tables capture the salient characteristics of the research and it can be placed within its specific context.

Conclusion and Recommendations

This review focused on interventions in low- and lower-middle-income countries to understand the possible effective interventions for contexts with limited resources. The studies included in this review provide several possible ways for moving the IE agenda forward: teacher training, small group and individual instruction in addition to large group, funding to improve facilities and building stakeholder partnerships. First, the more rigorous studies demonstrated teacher training can positively impact teachers’ attitudes towards inclusion, teaching strategies and knowledge of disabilities in as little as ten hours. Over 50% of the 31 studies advocate for improved pre-service and in-service trainings for teachers. Second, similarly strong evaluations revealed that adding small groups and individual instruction to inclusive large group instruction improved outcomes in low resource settings. Third, there are positive relationships between both accessible facilities and academic performance and materials and inclusive practice. Of the 31 studies currently reviewed, 70% of studies advocate for an increase of resources and funding to provide the necessary materials. Finally, interventions for developing action items for IE can involve different groups of government workers, community members, teachers and parents with measurable positive outcomes for inclusion.

Given the nascent findings, more research focused on interventions and their outcomes should be developed to assist policymakers and practitioners in continuing to improve IE. Future research should include the voices of students with disabilities (Cluley et al., Citation2020). The commitment to IE as a right for all people expressed in the widely ratified CRPD, necessitates that we take these interventions seriously when developing policies, strategies and practice so that all learners can participate fully in general education.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (61 KB)Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Corina Post and Willetta Waisath for their review of initial searches, to Nick Perry for his assistance with the map, and to Kate Huh for her editorial assistance and substantive feedback on the results.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912X.2022.2095359

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. (Srivastava et al., Citation2015b)

2. (Kurniawati et al., Citation2017)

3. (Carew et al., Citation2019)

4. (Delkamiller et al., Citation2016)

5. (Sibtain, Citation2013)

6. (Majoko, Citation2019)

7. (Eichhorn, Citation2016)

8. (Gunarhadi et al., Citation2016)

9. (Stone-Macdonald & Fettig, Citation2019)

10. (Okongo et al., Citation2015)

11. (Erhard et al., Citation2013)

12. (Adeniyi et al., Citation2015)

13. (Oluremi & Olubukola, Citation2013)

14. (Das, Kuyini, & Desai, Citation2013)

15. (Singal, Citation2008)

16. (Ocloo & Subbey, Citation2008)

17. (Agbeke, Citation2005)

18. (Al-Dababneh, Citation2016)

19. (Al Khateeb & Hadidi, Citation2009)

20. (Mosia, Citation2014)

21. (Johnstone & Chapman, Citation2009)

22. (Uzair-ul-Hassan et al., Citation2015)

23. (Tungaraza, Citation2014)

24. (Chadha, Citation2007)

25. (Agbenyega, Citation2007)

26. (Beutel et al., Citation2019)

27. (Trani et al., Citation2019)

28. (Polat, Citation2011)

29. (Villa et al., Citation2003)

30. (Malle et al., Citation2015)

31. (Singal et al., Citation2015)

References

- Adeniyi, S. O., Owolabi, J. O., & Olojede, K. (2015). Determinants of successful inclusive education practice in Lagos State Nigeria. World Journal of Education, 5(2), 26–32.

- Agbeke, W. K. (2005). Impact of segregation and inclusive education at the basic education level on children with low vision in Ghana. International Congress Series, 1282, 775–779.

- Agbenyega, J. (2007). Examining teachers’ concerns and attitudes to inclusive education in Ghana. International Journal of Whole Schooling, 3(1), 41–56.

- Al Khateeb, J. M., & Hadidi, M. S. (2009). Teachers’ and mothers’ satisfaction with resource room programs in Jordan. Journal of the International Association of Special Education, 10(1). doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2015.11.005

- Al-Dababneh, K. A. (2016). Quality assessment of special education programmes: listen to the parents. International Journal of Special Education, 31(3), 480–507.

- Amor, A. M., Hagiwara, M. S., Shogren, K. A., Thompson, J. R., Verdugo, M. Á., Burke, K. M., & Aguayo, V. (2019). International perspectives and trends in research on inclusive education: a systematic review. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 23(12), 1277–1295.

- Artiles, A. J., & Kozleski, E. B. (2016). Inclusive education’s promises and trajectories: critical notes about future research on a venerable idea. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 24(43–44), 1–25.

- Beutel, D., Tangen, D., & Carrington, S. (2019). Building bridges between global concepts and local contexts: implications for inclusive education in Nepal, Sri Lanka, and Bangladesh. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 23(1), 109–124.

- Bowen, T. B., & Ellis, L. E. (2009). Integration. In S. Wallace Ed., A dictionary of education. Oxford University Press Retrieved 25 May 2020 https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199212064.001.0001/acref-9780199212064-e-496

- Carew, M. T., Deluca, M., Groce, N., & Kett, M. (2019). The impact of an inclusive education intervention on teacher preparedness to educate children with disabilities within the lakes region of Kenya. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 23(3), 229–244.

- Chadha, A. (2007). Evaluation of a pilot project on inclusive education in India. Journal of the International Association of Special Education, 8(1), 54–60.

- Chong, P. W., & Graham, L. J. (2017). Discourses, decisions, designs: ‘Special’ education policy-making in New South Wales, Scotland, Finland and Malaysia. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 47(4), 598–615.

- Cluley, V., Fyson, R., & Pilnick, A. (2020). Theorising disability: A practical and representative ontology of learning disability. Disability & Society, 35(2), 235–257. doi:10.1080/09687599.2019.16326928

- Das, A. K., Kuyini, A. B., & Desai, I. P. (2013). Inclusive education in india: are the teachers prepared? International Journal of Special Education, 28(1), 27–36.

- Delkamiller, J., Swain, K., Ritzman, M. J., & Leader-Janssen, E. M. (2016). Evaluating a special education training programme in Nicaragua. International Journal of Disability, Development & Education, 63(3), 322–333.

- Eichhorn, M. S. (2016). Haunted by math: the impact of policy and practice on students with math learning disabilities in the transition to post-secondary education in Mumbai, India. Global Education Review, 3(3), 75–93.

- Erhard, L., Degabriele, J., Naughton, D., & Freeman, M. C. (2013). Policy and provision of WASH in schools for children with disabilities: a case study in Malawi and Uganda. Global Public Health, 8(9), 1000–1013.

- Grech, S. (2009). Disability, poverty and development: Critical reflections on the majority world debate. Disability & Society, 24(6), 771–784.

- Gunarhadi, S., Anwar, M., Andayani, T. R., & Shaari, A. S. (2016). The effect of cluster-based instruction on mathematic achievement in inclusive schools. International Journal of Special Education, 31(1), 78–87.

- Johnstone, C. J., & Chapman, D. W. (2009). Contributions and constraints to the implementation of inclusive education in Lesotho. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 56(2), 131–148.

- Kim, K. M., & Fox, M. H. (2011). A comparative examination of disability anti‐discrimination legislation in the United States and Korea. Disability & Society, 26(3), 269–283.

- Kurniawati, F., de Boer, A. A., Minnaert, A. E. M. G., & Mangunsong, F. (2017). Evaluating the effect of a teacher training programme on the primary teachers’ attitudes, knowledge and teaching strategies regarding special educational needs. Educational Psychology, 37(3), 287–297.

- Lindner, K. T., & Schwab, S. (2020). Differentiation and individualisation in inclusive education: a systematic review and narrative synthesis. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 1–21. doi:10.1080/13603116.2020.1813450

- Majoko, T. (2019). Teacher key competencies for inclusive education: tapping pragmatic realities of zimbabwean special needs education teachers. SAGE Open, 9(1), 215824401882345.

- Malle, A. Y., Pirttimaa, R., & Saloviita, T. (2015). Inclusion of students with disabilities in formal vocational education programs in Ethiopia. International Journal of Special Education, 30(2), 57–67.

- Mittler, P. (2015). The UN convention on the rights of persons with disabilities: implementing a paradigm shift. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 12(2), 79–89.

- Mosia, P. A. (2014). Threats to inclusive education in lesotho: an overview of policy and implementation challenges. Africa Education Review, 11(3), 292–310.

- Ocloo, M. A., & Subbey, M. (2008). Perception of basic education school teachers towards inclusive education in the hohoe district of Ghana. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 12(5–6), 639–650.

- Okongo, R. B., Ngao, G., Rop, N. K., & Nyongesa, W. J. (2015). Effect of availability of teaching and learning resources on the implementation of inclusive education in pre-school centers in Nyamira North Sub-County, Nyamira County, Kenya. Journal of Education and Practice, 6(35), 132–141.

- Oluremi, F. D., & Olubukola, O. O. (2013). Impact of facilities on academic performance of students with special needs in mainstreamed public schools in Southwestern Nigeria. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 13(2), 159–167.

- Polat, F. (2011). Inclusion in education: A step towards social justice. International Journal of Educational Development, Education Quality for Social Justice, 31(1), 50–58.

- Reeves, P., Ng, S. L., Harris, M., & Phelan, S. K. (2020). The exclusionary effects of inclusion today: (Re)production of disability in inclusive education settings. Disability & Society, 1–26. doi:10.1080/09687599.2020.1828042

- Reichrath, E., de Witte, L. P., & Winkens, I. (2010). Interventions in general education for students with disabilities: A systematic review. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 14(6), 563–580.

- Schuelka, M. J., & Engsig, T. T. (2020). On the question of educational purpose: Complex educational systems analysis for inclusion. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 1–18. doi:10.1080/13603116.2019.1698062

- Sherlaw, W., Lucas, B., Jourdain, A., & Monaghan, N. (2014). Disabled people, inclusion and policy: Better outcomes through a public health approach? Disability & Society, 29(3), 444–459.

- Sibtain, A. (2013). Training teacher’s in early indentation and management of Specific Learning Difficulties (Spld) in mainstream pakistani school. Journal of Pakistan Psychiatric Society, 10(2), 72–76.

- Singal, N. (2008). Working towards inclusion: reflections from the classroom. Teaching and Teacher Education, 24(6), 1516–1529.

- Singal, N., Salifu, E. M., Iddrisu, K., Casely-Hayford, L., & Lundebye, H. (2015). The impact of education in shaping lives: reflections of young people with disabilities in Ghana. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 19(9), 908–925.

- Srivastava, M., de Boer, A. A., & Pijl, S. J. (2015a). Inclusive education in developing countries: a closer look at its implementation in the last 10 years. Educational Review, 67(2), 179–195.

- Srivastava, M., de Boer, A. A., & Pijl, S. J. (2015b). Know how to teach me … evaluating the effects of an in-service training program for regular school teachers toward inclusive education. International Journal of School & Educational Psychology, 3(4), 219–230.

- Stone-Macdonald, A., & Fettig, A. (2019). Culturally relevant assessment and support of grade 1 students with mild disabilities in tanzania: an exploratory study. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 66(4), 374–388.

- Trani, J. F., Bakhshi, P., Mozaffari, A., Sohail, M., Rawab, H., Kaplan, I., … Hovmand, P. (2019). Strengthening child inclusion in the classroom in rural schools of pakistan and afghanistan: what did we learn by testing the system dynamics protocol for community engagement? Research in Comparative and International Education, 14(1), 158–181.

- Tungaraza, T. (2014). The arduous march toward inclusive education in tanzania: head teachers’ and teachers’ perspectives. Africa Today, 61(2), 109–123.

- UN General Assembly. (2006). Optional protocol to the convention on the rights of persons with disabilities. New York, NY: United Nations Retrieved 29 July 2019. http://www.un.org/disabilities/documents/convention/convoptprot-e.pdf

- UN General Assembly. (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. New York, NY: UN Accessed 19 March 2019. https://undocs.org/A/RES/70/1

- Uzair-ul-Hassan, M., Hussain, M., Parveen, I., & De Souza, J. (2015). Exploring teachers’ experiences and practices in inclusive classrooms of model schools. Journal of Theory & Practice in Education, 11(3), 894–915.

- Villa, R. A., Van Tac, L., Muc, P. M., Ryan, S., Thuy, N. T. M., Weill, C., & Thousand, J. S. (2003). Inclusion in Viet Nam: more than a decade of implementation. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 28(1), 23–32.

- World Bank. (2018). Atlas of sustainable development goals 2018: From world development indicators. Washington DC, World Bank. Retrieved 21 June 2019. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/590681527864542864/Atlas-of-Sustainable-Development-Goals-2018-World-Development-Indicator