ABSTRACT

Succeeding at university can be a complex matter, and the barriers are manifold for students with disabilities (SwDs). Accommodations are available for those with needs, but these alone do not meet the political goals of inclusive educations. Student ambassadors act as experienced representatives on campuses, supporting others and gaining individual benefits themselves. Approaches building on SwDs’ experiences and capacities can be a means to overcome the complex barriers often faced throughout education. This scoping review aimed to map research on student ambassador interventions for SwDs in higher education and identify the interventions’ key concepts. The result will inform an ambassador intervention in higher education. Six electronic databases were searched for peer-reviewed articles of any design published between 2010 and December 2020. Six studies met the inclusion criteria. A thematic synthesis resulted in three key concepts: peer guidance and supportive relationships; building strategies and transferable skills; and advocating for change. However, no program utilises exclusively students with disabilities in ambassador roles. The results indicate a lack of research as well as awareness on the unexplored potential of actively involving SwDs in ambassador roles.

Introduction

Becoming a university student is, for many, a life-changing event. It is often a time of great excitement, but also uncertainty and unfamiliar demands. Having a disability can add further stress to an already challenging situation. In Nordic countries, every fourth student in higher education (HE) reports a lasting injury, illness or disability (SSB, Citation2018). Chronic conditions are most reported, followed by mental health conditions and, subsequently, reading and writing difficulties.

Ensuring inclusive education is a significant political goal in most countries (European Commision, Citation2010; J. Sachs, Kroll, Lafortune, Fuller, & Woelm, Citation2021). HE is an important gateway to employment for the general population, but more significantly so for students with disabilities (SwDs) (Molden, Wendelborg, & Tøssebro, Citation2009). However, SwDs are less likely to pursue and graduate from HE, compared to students without disabilities (Kim & Lee, Citation2016), and face barriers when transitioning to employment (Goodall, Mjøen, Witsø, Horghagen, & Kvam, Citation2022; Nolan & Gleeson, Citation2017; WHO, Citation2011).

The barriers SwDs face through HE are numerous and complex (Kreider, Bendixen, & Lutz, Citation2015). The process of finding information about campus services and requesting accommodations is challenging and time consuming (Langørgen & Magnus, Citation2018; Magnus, Citation2009). SwDs work harder to reach their goals, participate less in social activities than fellow students (D. Sachs & Schreuer, Citation2011), and experience tensions regarding stigma, misconceptions and individual identity (Kraus, Citation2008; Lightner, Kipps-Vaughan, Schulte, & Trice, Citation2012). Although accommodations and adaptations are available, many students do not disclose their disabilities and, thus, do not receive accommodations they could potentially benefit from (Newman & Madaus, Citation2015). In Nordic countries, every third SwD considers the support that they receive as insufficient (SSB, Citation2018). Studies have raised concerns about the ways universities respond to, support, and meet the needs of SwDs (Hutcheon & Wolbring, Citation2012; Leake & Stodden, Citation2014; D. Sachs & Schreuer, Citation2011). This article addresses the need to develop alternative approaches when aiming for inclusive educations.

Barriers in today’s practice can be grounded in existing conceptualisations of disability. The medical model has deep roots, viewing disability as a personal concern and a deviation from ‘normality’. Contrastingly, the social model frames disability as a socially constructed phenomenon that exists due to environmental barriers (Shakespeare, Citation2017). In a relational model, disability is seen as emerging from the mismatch between the functioning of an individual and societal and environmental demands (Shakespeare, Citation2013; Tøssebro, Citation2004). This also represents changes in perspectives of rehabilitation; from the non-participating user receiving services, to overcoming challenges through active user-involvement and empowerment (Tøssebro, Citation2013). Participation, although individually conceptualised (Hammel et al., Citation2008), promotes human rights enabling democracy, public security, economic development and social inclusion (United Nations, Citation2018). The right to participate emancipates groups and individuals, addressing discriminating and marginalising practices. Drawing upon the evolving paradigms of disability there is an imminent need to introduce approaches involving active participation of SwDs. Currently, SwDs are prominently viewed and supported through a medical lens within universities (Nieminen, Citation2021).

There are examples of universities providing peer-mentors to facilitate support for SwDs (Nora & Crisp, Citation2007; Terrion, Citation2012). However, considering that mentoring is a widely used intervention, little knowledge exists when it comes to mentoring in the field of disability (Brown, Takahashi, & Roberts, Citation2010; Budge, Citation2006). Students can also be engaged as ambassadors where they act as experienced representatives to recruit prospective students or support underrepresented individuals (Green, Citation2018; Ylonen, Citation2012). While designed to increase access and retention for others, the role also indicates a positive effect on the ambassador’s own retention and success (Green, Citation2018). Still, the roles of mentors and ambassadors seem commonly restricted to students without disabilities. However, at Trinity College in Dublin, Ireland, the term ambassador is reserved solely for SwDs. The Disability Service Student Ambassador Programme was developed in 2015 (Dublin, Citation2019). Ambassadors represent and showcase Trinity College Dublin Disability Service to prospective students and share their experiences, acting as positive role models and information providers. The Program aims to facilitate learning opportunities and skill development as pathways through education and into employment. While experiences and results from this program, have not been published, other research clearly recommends that universities must develop strategies and support on campus that builds on the students’ experiences and capacities in order to reach political goals of inclusion and democratic rights (Getzel, Citation2008; Nolan & Gleeson, Citation2017). This scoping review aims to map research on student ambassador interventions for SwDs to provide an overview of existing experiences. Additionally, we aim to identify the key concepts used in different approaches to inform the design of an ambassador intervention in higher education.

Materials and Methods

A protocol for the scoping review has been registered in Open Science Framework [https://osf.io/z76bp/]. This scoping review followed the methodological steps provided by Arksey and O’Malley (Citation2005) and further enhancements by Levac, Colquhoun, and O’Brien (Citation2010); (1) Identifying the research question; (2) Identifying relevant studies; (3) Study selection; (4) Charting the data; (5) Collating, summarising and reporting the result, and; (6) Consultation. A scoping review was considered appropriate as they are commonly used to provide overviews of an area of evidence, and involve synthesising and analysing a wide range of research – providing a greater conceptual clarity within a topic (Davis, Drey, & Gould, Citation2009), as well as informing future research (Tricco et al., Citation2016).

Identifying the Research Question

To inform the development of an ambassador intervention, we explored the content and experiences of existing relevant approaches, as well as students’ experiences and evaluations. The following research questions guided the review:

What student ambassador interventions exist for SwDs in higher education?

What are the components and key concepts in the interventions?

What are students’ experiences and evaluations of the interventions?

Identifying Relevant Studies

A comprehensive literature search was conducted in six databases: ERIC, Education Source, Web of Science, PsycINFO, CINAHL and MEDLINE. The databases were searched by an information specialist (the fifth author) on the 4th, 8th, and 12th of December 2020. The search strategy was developed in collaboration with the first, second and last author and the information specialist. Several preliminary searches using different terms and combinations were conducted and discussed before the final search strategy was established. The search strategy was optimised by including a combination of free-text terms and thesaurus terms (e.g ERIC Subject Descriptors and Medical Subject Headings-MeSH), to identify relevant studies involving relevant populations (students with disability in higher education) and approaches (ambassador interventions). Broad search terms were considered necessary to avoid relevant studies being missed. Results were restricted to publication year 2010–2020, English language, and peer-reviewed journals. See for an example search string (ERIC).

Table 1. Search concepts and terms. example search string from ERIC database.

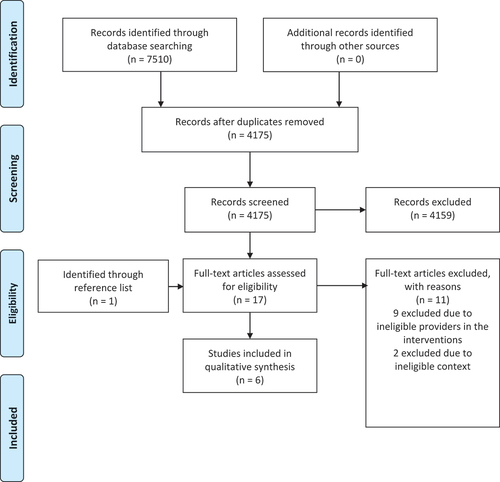

A total of 7510 references were initially identified through database searching. The references were imported to EndNote 20. Guided by the method of Bramer, Giustini, de Jonge, Holland, and Bekhuis (Citation2016), p. 3335 duplicates were removed, resulting in 4175 unique references.

Study Selection

Studies were included if the following inclusion criteria were met:

Studies must include approaches to support or strengthen participation for students with non-specific disabilities

Studies must include active involvement of students as key providers (ambassadors) in the approaches. Based on available research, studies were included in prioritised order:

Studies including SwDs in ambassador roles

Studies including students in ambassador roles

Studies must be situated in higher education, equivalent to bachelor or master level

Studies must be published after 2010-01-01 to capture new and relevant research

Studies must be in English language and published in peer-reviewed journals with no restrictions to study design

Research was excluded if one or more inclusion criteria were not met. Approaches directed towards specific diagnoses or exceeding beyond perspectives of disabilities, or where key providers were non-students (e.g faculty staff, therapists), were excluded. Approaches based on solely economic support, digital tools/aids, or only at specific challenges or skill enhancements (e.g reading and writing programs, enhancing mathematics skills etc.), were not eligible. Special education, individualised education or curriculum developed specifically for students with disabilities were also excluded.

Based on the criteria for inclusion and exclusion, the first author screened all titles and abstracts yielded from the search. This was subsequentially reviewed by the last author. When the initial selection was completed, screening of full-text articles was performed independently by the first and last author. The selection of titles, abstracts and full texts was based on a consensus with the other authors. The second author was consulted when a disagreement occurred. An overview of the selection process is illustrated in .

Figure 1. The process of study selection is illustrated in a PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flow diagram (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, & Altman, Citation2010).

Charting the Data

A data extraction table was developed prior to the search and updated during the review as recommended by Levac et al. (Citation2010). Extracted information included: author(s), year of publication, geographical context, aim of study, study design, name of intervention, participants, sample size and outcome.

Analysing the Data

The analysis is based on a thematic synthesis approach which involves three steps: coding line-by-line, the generation of descriptive themes and the generation of analytical themes (Thomas & Harden, Citation2008). In the first step, the intervention descriptions in each primary study were coded line-by-line by the first author. Codes were developed through an iterative process, whereby the descriptions were continuously revisited and new codes were added, if necessary. This process enables a translation of meaning across studies (Britten et al., Citation2002). Before completing this step, codes were checked for consistency and reviewed by the last author to ensure rigour. In step two, all authors discussed the similarities and shared meaning across studies based on the initial coding and grouped related codes into a new hierarchy of codes. The final step of generating analytical themes was carried out through several meetings and discussions between the first and last author, and all authors reviewed the final draft of the key concepts.

Assessing Methodological Quality

Assessing methodological quality can be an appropriate step if the main concern is to explore an effect across studies, but is generally not required in scoping methodology (Peters et al., Citation2015). This scoping review aimed to map research to identify key concepts, and – if stated – the evaluation outcome from the studies. Therefore, a critical appraisal of included studies was not undertaken.

Results

Study Characteristics

This scoping review located six studies describing four interventions complying with the inclusion criteria. None of the interventions included exclusively SwDs as ambassadors.

Three interventions were mentor programs, with the remaining being a student-driven committee. The articles were published between 2013 and 2020. The study designs included qualitative (n = 2), quantitative (n = 1) and mixed methods (n = 3). The studies were conducted in the United States (US) (n = 4) and Canada (n = 2). presents an overview of the included studies and the main study characteristics.

Table 2. Study characteristics of included studies.

One of the studies from the US describes the Greater Opportunity for Academic Learning and Living Successes (GOALS2) program in a university in Pennsylvania, where Occupational Therapist (OT) students practiced OT services to mentor SwDs (Boney, Potvin, & Chabot, Citation2019). Two studies from the US describe the Student to Student Mentoring Program (SSMP) at the university of Massachusetts, where Psychology or Disability Studies students mentor 1st year SwDs (Hillier, Goldstein, Tornatore, Byrne, & Johnson, Citation2019; Hillier et al., Citation2018). The remaining study from the US describes the Peer Mentor Program (PMP) in a university in New England where Psychology students mentor SwDs (Lombardi, Rifenbark, Monahan, Tarconish, & Rhoads, Citation2020). The two studies from Canada describe the Accessibility Planning Committee (APC) at the University of Windsor, where Social Work and Disability Studies students raise awareness of disability and accessibility issues (Cragg, Carter, & Nikolova, Citation2013; Cragg, Nikolova, & Carter, Citation2015).

Across the studies, disabilities among mentees included neurological-, psychological-, mobility-, medical-, learning disabilities and ‘other’. Eight out of 35 mentors reported a disability (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, Asperger syndrome, post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, anxiety and dyslexia) in the SSMP (Hillier et al., Citation2019), while the remaining studies do not state the disability status of their mentors or members.

Intervention Components

The process of initial coding resulted in 61 codes representing the interventions components and are presented in .

Table 3. Intervention components.

Key Concepts across the Interventions

The analysis resulted in 12 groups of codes and further, three key concepts emerged: peer guidance and supportive relationships, building strategies and transferable skills, and advocating for change. Code groups and key concepts are presented in .

Table 4. Code groups (n = 12) and key concepts (n = 3) across the interventions.

Key Concept 1: Peer Guidance and Supportive Relationships

Three out of four interventions were mentor programs, meaning mentoring aspects were given substantial attention in the studies – both individually and combined. The mentor programs were structured on peer mentoring and based on theoretical frameworks. One described the Coaching-in-Context process (Boney et al., Citation2019). Two studies used a framework by Nora and Crisp (Citation2007) that emphasises psychological and emotional support, goal setting, role modelling and supporting academic success (Hillier et al., Citation2018). The last provided introductions to Applied Behavioural Analysis for the mentors (Lombardi et al., Citation2020). A common aspect in the mentoring programs was the mentor’s role in facilitating the mentees in working towards goal attainment. Goals were either self-identified by mentees (Boney et al., Citation2019; Lombardi et al., Citation2020) or based on common challenges that SwDs face according to literature or staff experiences (Hillier et al., Citation2019). Mentors met regularly with their mentees, usually for one hour per week (Hillier et al., Citation2019; Lombardi et al., Citation2020), where the sessions focused on addressing issues relevant to obtain mentees’ goals. As part of the process, mentors created plans, built reports, reviewed progress, and tracked the process towards goal attainment (Boney et al., Citation2019; Hillier et al., Citation2018; Lombardi et al., Citation2020).

The mentor relationship provided SwDs with guidance from fellow students, also creating opportunities for peer support. While most mentors did not have disabilities themselves, they had experiences of being students and were, through their training, presented with overviews of typical scenarios, issues, strengths and challenges related to different disabilities (Hillier et al., Citation2018). Mentees experienced supportive relationships with mentors, and valued having fellow students to talk to rather than staff (Hillier et al., Citation2019).

Key Concept 2: Building Strategies and Transferable Skills

The second key concept was facilitation to develop beneficial strategies and skills for education and future employment. Social- and communication strategies were given much attention, and could, for instance, be about when and how to enter a conversation (Hillier et al., Citation2019; Lombardi et al., Citation2020), socialising on campus (Hillier et al., Citation2019; Lombardi et al., Citation2020) and classroom etiquette (Hillier et al., Citation2019). Within academic strategies, time management, organisation and study strategies were recursive in all mentor programs. In Boney et al. (Citation2019), participants addressed topics such as assistive technology, breakdown, initiating and pacing. In Lombardi et al. (Citation2020), examples were reviewing and planning homework. Hillier et al. (Citation2019) outlined how mentors helped mentees with preparing for finals, understanding how to improve academic performance, assessing strengths and areas for improvement, and addressing unrealistic expectations. In the mentor programs, strategies such as seeking help, and finding and accessing campus resources were practiced (Hillier et al., Citation2019; Lombardi et al., Citation2020). Mentors also worked with mentees on personal strategies such as coping with peer pressure (Hillier et al., Citation2019) and self-advocacy (Boney et al., Citation2019). Health- and wellness strategies such as exercise, sleep and eating (Boney et al., Citation2019) were addressed, along with how to manage stress and increase self-care (Hillier et al., Citation2019).

From the perspectives of the students in ambassador roles, participation enabled access to enhanced learning situations, developed work related skills, and added valuable experiences for future employment. In the GOALS2 program, OT students practiced OT services relevant for future work (Boney et al., Citation2019). Psychology or Disability Studies students gained knowledge and experience in disability issues and in peer- and social supports in the SSMP and PMP (Hillier et al., Citation2018; Lombardi et al., Citation2020). In the APC, social work students practiced social work skills gaining relevant experiences for future employment. For instance, students took part in field placements, counselled students, held presentations, practiced leadership and citizenship skills and networked professionally within campuses and communities (Cragg et al., Citation2013, Citation2015). Mentor training and interactions with SwDs provided mentors with disability knowledge and frameworks relevant for future employment (Hillier et al., Citation2018). Through the interventions, students were provided with arenas to practice communication with peers and staff (Boney et al., Citation2019; Hillier et al., Citation2018; Lombardi et al., Citation2020), and to experience personal growth and practice relevant skills in a safe environment (Cragg et al., Citation2013).

Key Concept 3: Advocating for Change

This concept provides insight on how the initiatives facilitates advocating for change. Cragg et al. (Citation2013) described that the students acted as a liaison between the APC and various university departments that focus on disability and accessibility policies and services. Through this, students created a greater support network. Students promoted and advocated through presentations to faculty members, radio programs, university websites, and through field placements on campus (Cragg et al., Citation2015). Cragg et al. (Citation2015) described how interactions within campus and community involvement -between fellow students and faculty members – raised and influenced awareness and attitudes towards disability issues. It was noted that staff started reporting issues and barriers to the committee. The circumstances indicated that the barriers reported were not new, but the presence of the committee had made them aware of their existence (Cragg et al., Citation2015).

In the mentoring programs, students advocated for change through strengthening knowledge and awareness on disability related issues among both fellow students and staff on campus. Hillier et al. (Citation2018) underlined how the mentors became more aware about stigmatised groups in society, recognising discriminating stereotypes, and became more open-minded towards others.

Two studies (Cragg et al., Citation2013, Citation2015) presented how students advocated change through student placement. These students attended meetings, counselled students, and participated in program development research. The students were also involved in developing an accessibility plan for the campus. Accessibility committees and student-driven-committees empowered students to become advocates for themselves and for each other, by allowing for knowledge transfer and promoting collaborative learning between students and the wider university (Cragg et al., Citation2015). Cragg et al. (Citation2013) highlighted how student involvement in the committee gave the students a voice to advocate for themselves, where they could use their experiences to remove barriers. Through this, they demonstrated civic engagement with accessibility issues. Being advocates for change, they modelled a belief in equality and social justice (Cragg et al., Citation2015).

Evaluation and Outcome

The studies explored outcomes both from the perspectives of SwDs (n = 3) and students in ambassador roles (n = 3) using qualitative data (Cragg et al., Citation2013, Citation2015), quantitative data (Lombardi et al., Citation2020), and mixed methods (Boney et al., Citation2019; Hillier et al., Citation2019, Citation2018).

Participation from both perspectives was generally associated with positive outcomes. SwDs experienced overall satisfaction, support and benefits (Boney et al., Citation2019; Hillier et al., Citation2019). Students in ambassador roles experienced more commitment to the university (Hillier et al., Citation2018) and gained relevant work experience (Cragg et al., Citation2013, Citation2015). Hillier et al. (Citation2019) found that benefits experienced by mentees, such as knowledge about the university and feelings of confidence, had lasting effects one year on. However, mentoring had limited impact towards complex skills, for instance self-advocacy and developing friendships (Hillier et al., Citation2019), and can cause unique challenges for mentors such as feelings of over-protection, trouble in communicating and not knowing how to help (Hillier et al., Citation2018). Even though mentees self-reported a positive impact on academic achievement (Boney et al., Citation2019), a significant impact on academic outcomes was not observed in the included studies (Hillier et al., Citation2019; Lombardi et al., Citation2020).

Discussion

This scoping review aimed to map research describing student ambassador interventions for SwDs in higher education. The systematic search yielded no studies published in peer-reviewed journals where SwDs exclusively hold roles as ambassadors. We did, however, find interventions for SwDs engaging students without disabilities as ambassadors, mentors, and committee members. The key concepts generated in this scoping review can add insight when designing inclusive interventions. Studies included in this review indicate the value of ambassador approaches as means of fostering peer relationships, competences, skill-building, and self-advocacy. Although SwDs experiences and voices in ambassador roles can add valuable contributions, these opportunities seem neither utilised nor explored today.

Guidance from peers can be an alternative solution to meet the complex challenges that SwDs face (Nora & Crisp, Citation2007), as accommodation services sometimes fail in meeting many of the personal, emotional and social needs in HE. While peers can offer valuable psychosocial support and be role models with related experiences (Budge, Citation2006; Terrion, Citation2012), students without disabilities lack the first-hand perspectives that SwDs can benefit from. Ideally, peer mentoring enables a mutual learning relationship (Brown et al., Citation2010), where SwDs may potentially benefit both as mentors and mentees. Yet, SwDs use a lot of time and energy on their studies (Magnus, Citation2009), and may have limited capacity to get involved in time-consuming activities. It is also crucial to be sensitive to power distribution in peer relationships and be aware of potential negative effects and the impact on both mentors and mentees (Embuldeniya et al., Citation2013).

SwDs benefit when faculties utilise students’ experiences and capacities, promote career related experiences, adopt principles of universal design, and are disability-aware (Getzel, Citation2008; Getzel & Thoma, Citation2008; Kraus, Citation2008; Nolan & Gleeson, Citation2017). Instead, students are left responsible for their own inclusion (Langørgen & Magnus, Citation2018; Magnus, Citation2009) and are faced with discriminating practices and misconceptions about their abilities when entering working life (WHO, Citation2011). How disability is conceptualised within societies is critical for how students develop a disability identity (Kraus, Citation2008). Universities today maintain practices pervaded by medical comprehensions, viewing SwDs as ‘special’, ‘different’ and as a ‘problem to be fixed’ (Nieminen, Citation2021, p. 3). Universities should rather provide opportunities for SwDs to build personal experiences, social connections and skills as stepping-stones to gain confidence in their abilities (Nolan & Gleeson, Citation2017). Still, research worldwide shows that lecturers lack knowledge, awareness, skills, and resources to support SwDs (Kendall, Citation2018; Moriña & Orozco, Citation2021; Mutanga & Walker, Citation2017; Svendby, Citation2020), and for many, their ability to support depends on prior encounters and experiences with SwDs.

‘Participation’ for SwDs involves more than merely granting compensating measures in academic situations (D. Sachs & Schreuer, Citation2011). In Hammel et al. (Citation2008), individuals with disabilities related different values to the term participation. For instance, it could be about active and meaningful engagement, being part of a community, supporting others, social connections, and inclusion. Accommodation services alone can, in many ways, facilitate a sense of being different instead of a sense of belonging. Hutcheon and Wolbring (Citation2012) and Kraus (Citation2008) highlight the importance of involving SwDs in initiatives regarding themselves to change for more inclusive practices and precise solutions. Involving students in decisions and development of own interventions is suggested as an important step to disowning the medical comprehensions of disabilities, and to promote social justice (Kraus, Citation2008).

Being ambassadors at Trinity College, Dublin, SwDs take an active, and often leading role, where their personal perspectives are acknowledged and showcased (Dublin, Citation2019). SwDs hold unique experiences and competences that should be reflected as a resource in education and employment (Kraus, Citation2008; Langørgen & Magnus, Citation2020). Utilising and promoting student experiences and voices can lay a powerful groundwork in inclusive practices. Furthermore, the process of developing such practices can emancipate students, helping them develop positive identities (Bessaha et al., Citation2020; Kraus, Citation2008). Moving towards more inclusive societies, universities need to acknowledge disability as a social construct, placing responsibility on campuses for discriminating practices; thus promoting a paradigm shift where students are emancipated, instead of merely being dependent on others for support (Kraus, Citation2008). Educational institutions hold a unique opportunity to acknowledge diversity and, at the same time, provide inclusive environments – setting precedence for diversity to the wider society (Leake & Stodden, Citation2014).

Methodological Considerations

This scoping review has applied rigorous and transparent methods to generate key concepts of current student ambassador interventions for SwDs, but it has several limitations. First, the thematic synthesis is based on a small number of studies. The studies explored participants’ experiences with taking part in the interventions and may not provide full program descriptions, which can result in missing or undetailed data as a basis for the synthesis.

Analysing primary studies into concepts can raise concerns towards adopting concepts into other contexts. The synthesis consists of interventions also including students without disabilities as ambassadors. While perceived relevant to inform the development of an ambassador intervention, there is uncertainty related to the pertinence. As the thematic synthesis provides transparency related to the process of analysis (Thomas & Harden, Citation2008) and the context of each study was stated, it allows readers to make their own judgements regarding the concept development and context relevance.

Finally, the findings may have been limited by the search terms used and the search strategy. Restrictions in publication date, language and peer reviewed journals may have excluded relevant studies. However, these restrictions were chosen to capture existing knowledge on new and relevant interventions.

Implications

This study shows an imminent lack of research on interventions utilising and promoting SwDs’ experiences and voices, as no studies exclusively or purposefully included SwDs as ambassadors. The studies included in the synthesis show positive experiences from students and campus communities taking part in the interventions. A such, this scoping review provides rationale for implementing similar interventions in all HE institutions. This study also implies that more weight should be placed on viewing SwDs as resources, actively integrating their experiences and voices into the development and facilitation of future interventions. Further research is of importance to support interventions through addressing both the process and the impact of promoting the voices of SwDs.

Acknowledgments

This work is part of the project “Pathways to the world of work for students with disabilities in higher education. The authors would like to give a special thanks to Dr. Gemma Goodall, Dr. Odd Morten Mjøen and the project group for helpful input and discussions throughout this process.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32.

- Bessaha, M., Reed, R., Donlon, A. J., Mathews, W., Bell, A. C., & Merolla, D. (2020). Creating a more inclusive environment for students with disabilities: Findings from participatory action research. Disability Studies Quarterly, 40(3). doi:10.18061/dsq.v40i3.7094

- Boney, J. D., Potvin, M.-C., & Chabot, M. (2019). The GOALS 2 program: Expanded supports for students with disabilities in postsecondary education (practice brief). Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 32(3), 321–329.

- Bramer, W. M., Giustini, D., de Jonge, G. B., Holland, L., & Bekhuis, T. (2016). De-duplication of database search results for systematic reviews in endnote. Journal of the Medical Library Association: JMLA, 104(3), 240.

- Britten, N., Campbell, R., Pope, C., Donovan, J., Morgan, M., & Pill, R. (2002). Using meta ethnography to synthesise qualitative research: A worked example. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 7(4), 209–215.

- Brown, S. E., Takahashi, K., & Roberts, K. D. (2010). Mentoring individuals with disabilities in postsecondary education: A review of the literature. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 23(2), 98–111.

- Budge, S. (2006). Peer mentoring in postsecondary education: Implications for research and practice. Journal of College Reading and Learning, 37(1), 71–85.

- Cragg, S. J., Carter, I., & Nikolova, K. (2013). Transforming barriers into bridges: The benefits of a student-driven accessibility planning committee. practice brief. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 26(3), 273–277.

- Cragg, S. J., Nikolova, K., & Carter, I. (2015). Sustaining learning initiatives through a student-led accessibility. Professional Development: The International Journal of Continuing, 18(2), 15–23.

- Davis, K., Drey, N., & Gould, D. (2009). What are scoping studies? A review of the nursing literature. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 46(10), 1386–1400.

- Dublin, T. C. (2019August26). Disability service student ambassador programme. https://www.tcd.ie/disability/current/volunteer.php

- Embuldeniya, G., Veinot, P., Bell, E., Bell, M., Nyhof-Young, J., Sale, J. E. M., & Britten, N. (2013). The experience and impact of chronic disease peer support interventions: A qualitative synthesis. Patient Education and Counseling, 92(1), 3–12.

- European Commision. (2010). European disability strategy 2010-2020: Arenewed commitment to a barrier-free Europe. Brussels. Retrieved August 25, 2021, from https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM%3A2010%3A0636%3AFIN%3Aen%3APDF

- Getzel, E. E. (2008). Addressing the persistence and retention of students with disabilities in higher education: Incorporating key strategies and supports on campus. Exceptionality, 16(4), 207–219.

- Getzel, E. E., & Thoma, C. A. (2008). Experiences of college students with disabilities and the importance of self-determination in higher education settings. Career Development for Exceptional Individuals, 31(2), 77–84.

- Goodall, G., Mjøen, O. M., Witsø, A. E., Horghagen, S., & Kvam, L. (2022). Barriers and facilitators in the transition from higher education to employment for students with disabilities: A rapid systematic review. Paper presented at the Frontiers in Education, 7, 882066.

- Green, A. (2018). The influence of involvement in a widening participation outreach program on student ambassadors’ retention and success. Student Success, 9(3), 25–37.

- Hammel, J., Magasi, S., Heinemann, A., Whiteneck, G., Bogner, J., & Rodriguez, E. (2008). What does participation mean? An insider perspective from people with disabilities. Disability and Rehabilitation, 30(19), 1445–1460.

- Hillier, A., Goldstein, J., Tornatore, L., Byrne, E., Ryan, J., & Johnson, H. (2018). Mentoring college students with disabilities: Experiences of the mentors. International Journal of Mentoring and Coaching in Education, 7(3), 202–218.

- Hillier, A., Goldstein, J., Tornatore, L., Byrne, E., & Johnson, H. M. (2019). Outcomes of a peer mentoring program for university students with disabilities. Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning, 27(5), 487–508.

- Hutcheon, E. J., & Wolbring, G. (2012). Voices of “disabled” post secondary students: Examining higher education “disability” policy using an ableism lens. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 5(1), 39–49.

- Kendall, L. (2018). Supporting students with disabilities within a UK university: Lecturer perspectives. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 55(6), 694–703.

- Kim, W. H., & Lee, J. (2016). The effect of accommodation on academic performance of college students with disabilities. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 60(1), 40–50.

- Kraus, A. (2008). The sociopolitical construction of identity: A multidimensional model of disability.

- Kreider, C. M., Bendixen, R. M., & Lutz, B. J. (2015). Holistic needs of university students with invisible disabilities: A qualitative study. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics, 35(4), 426–441.

- Langørgen, E., & Magnus, E. (2018). ‘We are just ordinary people working hard to reach our goals!’Disabled students’ participation in Norwegian higher education. Disability & Society, 33(4), 598–617.

- Langørgen, E., & Magnus, E. (2020). ‘I have something to contribute to working life’–students with disabilities showcasing employability while on practical placement. Journal of Education and Work, 33(4), 271–284.

- Leake, D. W., & Stodden, R. A. (2014). Higher education and disability: Past and future of underrepresented populations. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 27(4), 399–408.

- Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O’Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5(1), 69.

- Lightner, K. L., Kipps-Vaughan, D., Schulte, T., & Trice, A. D. (2012). Reasons university students with a learning disability wait to seek disability services. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 25(2), 145–159.

- Lombardi, A., Rifenbark, G. G., Monahan, J., Tarconish, E., & Rhoads, C. (2020). Aided by extant data: The effect of peer mentoring on achievement for college students with disabilities. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 33(2), 143–154.

- Magnus, E. (2009). Student, som alle andre: En studie av hverdagslivet til studenter med nedsatt funksjonsevne. Trondheim: Norges teknisk-naturvitenskapelige universitet.

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2010). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. International Journal of Surgery (London, England), 8(5), 336–341.

- Molden, T. H., Wendelborg, C., & Tøssebro, J. (2009). Levekår blant personer med nedsatt funksjonsevne. Analyse av levekårsundersøkelsen blant personer med nedsatt funksjonsevne 2007. Trondheim: NTNU Samfunnsforskning AS.

- Moriña, A., & Orozco, I. (2021). Spanish faculty members speak out: Barriers and aids for students with disabilities at university. Disability & Society, 36(2), 159–178.

- Mutanga, O., & Walker, M. (2017). Exploration of the academic lives of students with disabilities at South African universities: Lecturers’ perspectives. African Journal of Disability, 6(1), 1–9.

- Newman, L. A., & Madaus, J. W. (2015). Reported accommodations and supports provided to secondary and postsecondary students with disabilities: National perspective. Career Development and Transition for Exceptional Individuals, 38(3), 173–181.

- Nieminen, J. H. (2021). Governing the ‘disabled assessee’: A critical reframing of assessment accommodations as sociocultural practices. Disability & Society, 1–28. doi:10.1080/09687599.2021.1874304

- Nolan, C., & Gleeson, C. I. (2017). The transition to employment: The perspectives of students and graduates with disabilities. Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research, 19(3), 230–244.

- Nora, A., & Crisp, G. (2007). Mentoring students: Conceptualizing and validating the multi-dimensions of a support system. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 9(3), 337–356.

- Peters, M. D. J., Godfrey, C. M., Khalil, H., McInerney, P., Parker, D., & Soares, C. B. (2015). Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. International Journal of evidence-based Healthcare, 13(3), 141–146.

- Sachs, D., & Schreuer, N. (2011). Inclusion of students with disabilities in higher education: performance and participation in student’s experiences. Disability Studies Quarterly, 31(2). doi:10.18061/dsq.v31i2.1593

- Sachs, J., Kroll, C., Lafortune, G., Fuller, G., & Woelm, F. (2021). Sustainable Development Report 2021: Cambridge University Press.

- Shakespeare, T. (2013). Disability rights and wrongs revisited. London: Routledge.

- Shakespeare, T. (2017). Disability: The basics. London: Routledge.

- SSB. (2018). Den europeiske studentundersøkelsen. Retrieved June 6, 2021, from https://www.ssb.no/utdanning/artikler-og-publikasjoner/hver-fjerde-student-har-en-funksjonsnedsettelse

- Svendby, R. (2020). Lecturers’ teaching experiences with invisibly disabled students in higher education: Connecting and aiming at inclusion. Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research, 22(1), 275–284.

- Terrion, J. L. (2012). Student Peer Mentors asa Navigational Resource in Higher Education. In S. J. Fletcher & C. A. Mullan eds., Navigational resource in higher education (pp. 383–397). Sage handbook of mentoring and coaching in education. Thousand Oaks CA: Sage Publications.

- Thomas, J., & Harden, A. (2008). Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 8(1), 45.

- Tøssebro, J. (2004). Introduction to the special issue: Understanding disability.

- Tøssebro, J. (2013). Hva er funksjonshemming. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K., Colquhoun, H., Kastner, M., … Wilson, K. (2016). A scoping review on the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 16(1), 15.

- United Nations. (2018). Guidelines for States on the effective implementation of the right to participate in public affairs. Switzerland: Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. Retrieved June 6, 2021, from https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/PublicAffairs/GuidelinesRightParticipatePublicAffairs_web.pdf

- WHO. (2011). Geneva: World report on disability. Retrieved June 4, 2021 from https://www.who.int/disabilities/world_report/2011/report.pdf

- Ylonen, A. (2012). Student ambassador experience in higher education: Skills and competencies for the future? British Educational Research Journal, 38(5), 801–811.