ABSTRACT

Leaving school prematurely can have lifelong repercussions, and further entrench inequity and cycles of poverty faced by youth with disabilities on the African continent. This manuscript shares the experiences of youth with disabilities in Ethiopia, Ghana, and South Africa who left education sooner than desired. It highlights the barriers leading to these educational inequalities, and facilitators that created necessary access and support systems. Method: This was a participatory research study with youth with disabilities implemented in three sites, namely, Ethiopia, Ghana and South Africa. This sample size for this paper was a total of 41 participants, which included males and females between 14–35 years of age, who self-identified as having a motor, communication, vision, and/or hearing impairment. Seven focus groups across the three sites were held. Results: Our analysis identified three key themes related to educational experiences: social environment, physical environment, and managing health challenges. Conclusion: The interdependence of relationships and support facilitated participation and inclusion in the education systems. We have framed recommendations using a feminist ethics of care, as it relates to attentiveness, responsibility, competence, responsiveness, and integrity.

Introduction

Despite global and national policies promoting and supporting education for youth with disabilities, many students with disabilities prematurely leave school at a higher rate than students without disabilities (Bost & Riccomini, Citation2006; Zablocki & Krezmien, Citation2013). This premature leaving can have lifelong repercussions, such as greater economic and social isolation in adulthood (Jesus et al., Citation2021; Rust & Metts, Citation2007), further entrenching inequity and cycles of poverty. In an attempt to understand and rectify educational inequalities faced by youth with disabilities on the African continent, we explored the following questions: 1. What are the key barriers and facilitators to education accessibility experienced by out-of-school youth with disabilities in Ethiopia, Ghana, and South Africa?; and 2. How do these experiences align and differ across cultural context?

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) states that individuals with disabilities have the right to inclusive education at all levels, without discrimination and on the basis of equal opportunity (UNICEF, Citation2017). This right means that children with disabilities should be entitled to free and compulsory primary education and youth and adults with disabilities should have access to secondary and higher education, vocational training, adult education, and lifelong learning (UNICEF, Citation2017). Despite these global commitments, people with disabilities tend to have significantly less access to school than those without disabilities (Devries et al., Citation2014; Stalker & McArthur, Citation2012). Having an impairment appears to double the likelihood of never enrolling in school in some African countries and considerably increases the likelihood of leaving school early (UNESCO, Citation2018; Cramm, Niebhor, Finkenflugel, & Lorenzo, Citation2013).

Research indicates that children with disabilities in Africa have a high level of exclusion from any form of school (ACPF, Citation2011; UNESCO, Citation2020). Although educational possibilities for African adolescents have improved over time, the largest advances appear to be in terms of gender parity and access to primary school (Musau, Citation2018). The education of youth with disabilities and the advancement of education beyond elementary school appear to be lagging (Cramm et al., Citation2013) and persons with disabilities in Africa have limited opportunities to benefit fully from education (Chataika, Mckenzie, Swart, & Lyner-Cleophas, Citation2012; Musau, Citation2018). If Ethiopia, Ghana, or South Africa are to achieve their educational obligations as signatories of the UNCRPD, it is critical to understand experiences of youth with disabilities who have been left behind. This study sought to capture the perspectives of youth with disabilities who left school sooner than desired, to better understand critical aspects of their experiences and identify potential supports which might have better enabled them to remain in school to achieve their desired level of education.

Methods

This focus group-based study was part of a participatory research project, developed and implemented in partnership with youth with disabilities. The research questions, study design, and data collection tools were all created in partnership between academic researchers and youth with disabilities researchers. To gain the richest data, youth with disabilities moderated the focus group discussions, with support from other researchers. Prior to data collection, the study was reviewed and approved by institutional ethics review boards in Canada, Ethiopia, Ghana, and South Africa.

Participants

This study included young people (male and female) who self-identified as having a motor, communication, vision, and/or hearing impairments. We chose the specific age criteria as 14–35 to align with the African Youth Charter. Defining ‘youth’ as up to age 35 allows for inclusion of people with disabilities who often start school at a much later age than peers on the continent of Africa. We included any participants who were not presently attending school – either because they did not ever have access, had dropped out, or they had completed one level of schooling and did not continue to the next level of schooling. We sampled participants strategically for diverse representation of gender and type of disability. Each country had a research site coordinator who worked with local community-based rehabilitation (CBR) programs, disabled persons organisations (DPOs), schools, governmental organisations and/or non-governmental organisations to identify potential participants.

Focus Groups

We conducted seven focus groups in total – one in Ghana, three in Ethiopia and three in South Africa. We aimed to recruit 6–8 participants per focus group, however actual focus group sizes ranged from 3–8 due to last-minute schedule conflicts of some potential participants. Focus groups lasted approximately 90 minutes (range: 65–105 minutes). Each site followed the same semi-structured focus group guide. Discussions revolved around experiences in school in general, barriers participants faced in attending school, facilitators that enabled them to attend and succeed in school, thoughts about how their disability affected their ability to participate in school, reasons why they might not have continued school as long as they would have liked, and suggestions for institutional and system changes to support students with disabilities to succeed up to university education and beyond.

Focus groups were conducted in English in Ghana and South Africa and in Amharic in Ethiopia. Each focus group had at least two trained facilitators (one of whom was a youth with disability), one who moderated the discussion and one who assisted and took notes. Where necessary a sign language interpreter was present. All researchers and participants completed COVID-19 self-screening and followed all health and safety precautions in accordance with local public health guidance at the time of the focus group. For South Africa, this meant that focus groups were conducted via Zoom, rather than in person due to local public health regulations at the time.

Data Analysis

All focus groups were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim and the Amharic transcription was translated into English and checked by a third party for accuracy. The international research team debriefed after each focus group to discuss how it went, and identify changes or follow-up/verification questions for subsequent focus groups. We analysed data concurrently and recursively within and across focus groups to identify themes (Charmaz, Citation2014). We utilised joint interpretation among academic and youth researchers as well as with representation from each of the study locations as a fundamental approach in our analysis. This approach strengthens the trustworthiness and applicability for those who must act on the findings (Jagosh et al., Citation2012; Salsberg, Maccauley, & Parry, Citation2014). Each research site began by open and focused coding of the transcripts from their location, identifying initial, site-specific findings. The international team then met to review and discuss site-specific findings and overall similarities and differences across sites. An analysis team representing members from all study sites and Canada then worked together to complete the analysis across sites, using the initial site-specific findings as the basis for discussion among the team related to the data across sites and come to consensus on overarching findings. We then recoded all transcripts with the assistance of NVivo software using the final themes.

Results

We had a total of 41 participants across seven focus groups. Participants had a range of impairments and varying life situations (e.g. unemployed, employed), and their age of leaving education (if they had any education at all) varied. provides participant details per site.

Table 1. Participant demographics.

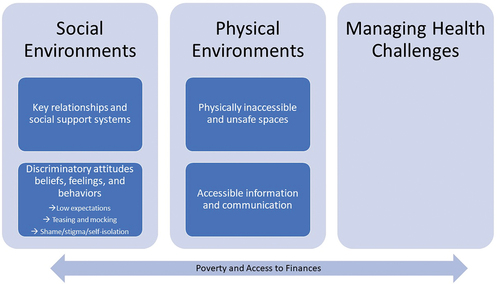

We have organised results across three themes: (a) Social Environments, (b) Built Environments, and (c) Health Challenges (See ). Poverty and limited access to money were underlying factors cross-cutting the three themes. For example, students discontinued school due to not having the finances available to pay for accessibility devices or to pay for necessary healthcare or treatment or for basic necessities of living (e.g. food/shelter), which led to them leave education so they could work to pay for their basic needs.

Social Environments

The social environment was the most prevalent consideration related to entry into or continuation in education. This included (a) having key relationships and social support systems which enabled youth with disabilities to enrol and be successful in school; and (b) experiencing discriminatory attitudes, beliefs, feelings, and behaviours, which caused youth with disabilities to discontinue education.

Key Relationships and Social Support Systems

Participants in all three countries shared how family members and others (typically parents, but also extended family, teachers, students, and other community members) enabled them to go to school because they supported them financially: ‘Teachers were good to me. They would buy lunch for me, pay school fees since I had no parents’ (Male, PI, South Africa). Conversely, many participants across all sites shared that the main reason they stopped attending school was that the key people in their lives died or we no longer a supportive figure for them.

If my parents hadn’t died early and I got a helper I wouldn’t have dropped out of school. I have gone very far in my education. So, because my parents died and I didn’t get money to continue that is why I dropped out. x(Male, HI, Ghana)

—

My problem was clear. I had no support whatsoever. I had no home. Since my parents were dead, I did not have a family to support me. But I was so interested to learn all the way to the end. (Female, PI, Ethiopia)

Beyond finances, participants indicated key figures in their lives who offered moral or emotional support to encourage continuation and success in their studies.

Teachers convinced my family to send me to school and encouraged me to study. They were constantly visiting me at home to consult with my parents. (Male, HI, Ethiopia)

—

I stopped school because when my grandmother passed away, there was not enough support system at home so I took pressure from friends and I decided to drop out. (Male, PI, South Africa)

Although many participants indicated the loss of supportive people as an important factor in them stopping education, some participants indicated that key figures in their lives who should have been supportive were not, rendering education more difficult.

I started university education without any support from my family. They were even pushing me to quit. They said, ‘school is for the rich, not for you’. My parents are poor farmers. Their attitude towards my education has been one of the factors that put pressure on me to drop out of university. (Female, VI, Ethiopia)

—

[My] family treated me like an outsider after my disability. I used to fight with my cousin as she used to say I’m useless. (Female, PI & VI, South Africa)

For many participants, an important factor for their success in school was the physical support offered to them by others, which could be in the form of reading out assignments or content on the blackboard to students with visual impairments, or physically supporting them with disability-related supports (for learning or to navigate inaccessible environments).

My little sister was also helping me to carry my bag as I walk to school. Then, she started working in another town and I had to struggle to carry my own bag with one hand and hold my crutch with the other. (Male, PI, Ethiopia)

—

My mentor that passed away helped me to get software overseas that I could speak over it and translate my work. Not having facilities does not allow you to do what you want to do. It makes you incapable. (Male, PI, South Africa)

In addition to discussing key individuals and how they helped in their education, participants across all sites also shared many unhelpful/harmful experiences due to attitudes of key individuals that resulted in them discontinuing their education.

Discriminatory Attitudes, Beliefs, Feelings, and Behaviours

Participants most commonly expressed discrimination related to teachers, students, and the community having low expectations about their capabilities for study and success. Participants also shared experiences of teasing, stigma, mocking, and name-calling, which also led to their ultimate discontinuation of their education. Finally, in the Ethiopian context, participants also shared experiences of shame, embarrassment, or self-stigma related to their disabilities that were influenced by attitudes of others.

Low Expectations

Participants shared many experiences with people having low expectations related to their abilities. These low expectations included not believing children with disabilities could be successful through education, anticipating an inability to do something before the student even tries, or assuming that any success was from benevolence of others, rather than the initiative of the student. Often, these low expectations started within the immediate family.

When I completed Form 4 I passed very well and was supposed to continue, but my mother said I couldn’t do anything for myself so I can’t go to the boarding school. She was concerned about how I will be able to fetch water for myself and also climb stairs… So, I suggested she take me to the day school and she said it was too far away. It really hurts me when I remember or think about it. Even with the training college too my mother said no because of my disability. (Male, PI, Ghana)

Another participant from Ghana reflected how these low expectations are actually not in the best interest of the family unit, as family could ultimately stand to benefit from supporting the education of the child with a disability.

Once they give birth to a disabled child they don’t take the child to school. They keep the child at home for a long time but the same parents when they give birth to ‘normal’ children ensure to give them the best education. But for we the disabled, especially we the deaf, because they know we cannot hear they don’t want to take us to school. However, when they do we are able to advance to become very knowledgeable people. The irony is that we, the rejected stones, later become the corner stones for our families, taking care of our families. (Male, HI, Ghana)

In addition to experiencing low expectations from immediate family members, participants also had to battle low expectations from teachers and fellow students, including not being asked to answer questions on the blackboard, and anticipating they would not be capable of performing in school or participating in class activities, even before being given the chance to try.

One day we were having athletics competition and the teacher placed me ahead of the rest because he felt I was disabled, but I insisted I start from the same point as the able students and … I ended the race in the 2nd position. (Female, VI, Ghana)

—

When I was in school, non-disabled students believed that students with disabilities did not have the ability to handle their own school work. They said that we [students with disabilities] get promoted not because we actually earned it, but because teachers give us pass marks out of sympathy compassion. They often say ‘Are you sure you are actually worthy of your results? The teacher must have been benevolent’. (Female, VI, Ethiopia)

Finally, participants indicated that low expectations went beyond family and school and permeated within wider society, creating communities that were not supportive of educating children with disabilities or employing graduates with disabilities after they complete their education. Some indicated that the societal belief that persons with disabilities could not ‘make it’ in education was a major challenge.

Many people think that we are simply liabilities to the nation. They do not think that we can educate ourselves and change the country. (Male, PI, Ethiopia)

Teasing and Mocking

In addition to having to navigate the low expectations of others, participants across countries indicated that experiences of teasing and mocking in school (from both teachers and students) precipitated their decision to discontinue their studies.

If children were not laughing at me, I would continue with my studies. Teachers should have intervened instead the teachers did nothing to stop the situation. I felt I was not recognised and not taken seriously. There was nothing I could have done but to leave school. (Male, PI, South Africa)

—

As for me, they used to mock me a lot. They called me ‘alookme’ because of how my eyes are and because of that people didn’t want to get close to me. So I didn’t have friends (Female, VI, Ghana).

Although often the teasing would come from fellow students either behind the teacher’s back or with the teacher aware but not intervening, sometimes the mockery came directly from the teachers themselves.

One time the teacher wrote on the board and I could not read it. When I complained, he sarcastically responded that if I cannot read, I should go and find ‘alontey goggles’ to wear and the whole class laughed at me. (Female, PI, Ghana)

Participants discussed employing a range of coping mechanisms related to the teasing – from laughing along to it, to getting in physical altercations because of it, to brushing it off or withdrawing into themselves.

Yes, there were people who said ‘things’ about us. I tried not to pay attention to what I hear and see; I preferred minding my own business. If things get better for me, I am interested to go back to school. I still want to remain hopeful because it will never be too late to go back to school at any age. (Male, PI, Ethiopia)

Participants in the Ethiopian context in particular also expressed internal shame, or self-stigma related to their disability, linked to their discouraging experiences in society.

Shame/Self Stigma/Isolation

Some participants from Ethiopia indicated that they were embarrassed by their impairment, and tried to hide it when possible. Sometimes, they indicated avoiding participating in some general school activities, if it meant that their disability would be more evident to others.

I was also very much ashamed of myself because of my disability. I tried to avoid any attention on me by hiding away my walking aid behind my back. It was so embarrassing. The rural community has ‘a big thing’ [judgmental view] about disability.(Female, PI, Ethiopia)

A different participant also echoed:

I used to feel so bad about myself because of my disability. I was so embarrassed when I could not walk as fast as my friends as we go together to school. Some friends used to leave me in the middle of the road all by myself since they did not want to be late. They never had positive attitude about me. (Female, PI, Ethiopia)

In addition to feeling embarrassment or shame about the impairment, one participant expressed a view shared between him and his friends that they were not capable of success (in education or employment), and therefore a reluctance to pursue education further.

None of my friends with hearing impairments believe that we can get proper education and become employable professionals. I never encountered a person with hearing impairment who is a professional employee with a university degree. I did not believe that I could get anywhere with education. That was why I decided to find other jobs that I can easily handle. (Male, HI, Ethiopia)

Having discussed the importance of the social environment, we will now turn to the school’s built environment as a contributing factor to remaining in or leaving education.

Physical Environments

Aspects of the physical environment pertinent to this study’s participants included (a) physically inaccessible and unsafe spaces; and (b) having accessible information and communication.

Physically Inaccessible and Unsafe Spaces

A number of participants with physical disabilities indicated that they had the greatest challenges and sometimes dropped out of school because of inaccessible facilities and unsafe physical spaces.

Buildings in schools are not accessible for crutches and wheelchair users. The roads in and outside schools are not comfortable for those walking with crutches. For example, how is it possible for me to go up to the upper floors of the buildings even here at this university? It is pointless if schools are being built like this. Only the able-bodied students can benefit. (Female, PI, Ethiopia)

—

At primary school, I wasn’t really strong physically. One day it rained and everybody had gone home and left me alone at the school and I didn’t know how I could go home through the mud. During that time too, there were no mobile phones for me to call anyone to come and pick me. So, I was in the school alone ‘til very late at around 4pm when I saw a passerby and pleaded with him to help me cross the mud. He carried me on his back ‘til we got to the roadside where he dropped me. (Male, PI, Ghana)

A participant from South Africa reflected on the irony of the government providing financial support to enable students to attend school in environments that are not physically accessible to them and indicated a desire not only for physical modifications, but support for personal assistants as well. A participant from Ethiopia also shared a similar perspective about the primary importance of investing in accessibility.

The schools should be physically accessible for wheelchair users and the visually impaired. The walkways and buildings should be built with the consideration of students with disabilities. Before stipends and other things, accessible materials and resources for students with visual impairments should be made available at schools.

Participants indicated a need for assistive devices to continue their education, and shared stories of dropping out when they were not able to get the devices that they needed to navigate their physical environments.

Having Accessible Information and Communication

The key experiences related to having accessible information and communication were communicated by students with sensory disabilities in the three countries. Most commonly, we heard from students who were deaf or hard of hearing who indicated that they had positive experiences in segregated schools (e.g. ‘Because I was at the school for the deaf and all of us over there were deaf I didn’t face any problems in school’ (Female, HI, Ghana)), and negative experiences and even drop out when they were required to learn in inclusive schools.

From grades 1–3, I was in a special school for the deaf. Learning was good here. After the third grade, I went to an inclusive school. The problem began from here. Teachers were not trained in sign language. Learning was very difficult for me when there were no teachers that could communicate with me in sign language. That was the major reason for me to drop out of school. (Male, HI, Ethiopia)

Students who were deaf or hard of hearing indicated that they would not understand what was happening in the class, but would try to get by with support of their peers, although not ideal. A participant indicated that even if teachers in inclusive schools received some training in sign language (e.g. the alphabet), it was not enough.

Students learned the subjects from grades 1–4 using sign language. Since grade 5, things are changed; there is no sign language at all. So, the students are forced to withdraw from schools. (Male, HI, Ethiopia)

Students who were blind or had low vision also indicated the critical importance of information and communication accessibility for them to continue with their schooling. They suggested that all schools should provide materials like braille books, audio recorders, personal computers, stylus and slates to properly accommodate students with sensory and/or communication impairments.

When I was in university, I had to ‘beg’ another a sighted student to write my assignments all the time. If I had my own personal computer, I would have done my assignments by myself and I would not have dropped out. How could I be academically successful if I were not studying and doing assignments independently? (Female, VI, Ethiopia)

A number of participants indicated that easier access to braille materials and braille learning supports would have better enabled them in their educational journey.

If you take a look at the whole Ghana, there is only one school for the blind in Akropong. So if anyone from anywhere wants to learn how to use the braille they must go to Akropong. [We need] not just Akropong because a lot of blind people want to learn how to use the Braille. (Female, PI, Ghana)

One participant indicated it was particularly challenging to complete group assignments, when she did not have the supports needed to communicate and keep up with their peers.

Among several challenges at the university, doing assignments in groups with other students was one of my difficulties; I did not have accessible resources available for me to study and share tasks with my peers in cooperative learning activities. I had no assistive devices to interact with my peers in group assignments. I failed to handle the academic duties because there were no accessible materials, devices, and support systems at the institution to assist me with my needs. (Female,VI, Ethiopia)

As it relates to educational accommodations, a number of other participants in different contexts also indicated an appreciation for being given more time to take exams or complete assignments (e.g. communicate their knowledge of the content), due to the specific limitations of their disabilities.

Having discussed social and physical environments, we now discuss how health challenges affected the ability of youth with disabilities to complete school.

Managing Health Challenges

Some participants indicated that they dropped out of school in the middle of an academic year, due to an inability to manage impairment-related health challenges. The experiences with health included leaving school because the health issue manifested at school (e.g. epileptic seizures in the middle of tests). Participants also indicated that because of their health issues, they could not function at school.

At grade 6, I developed a tumor on my finger. I was not able to write. I tried to get help [from a large national hospital] … they said they could not help me beyond this point. They recommended that the better procedure and medication were only available abroad. So, I dropped out of school in grade six because of that. (Female, PI, Ethiopia)

Another participant indicated both physical challenges to performance as well as challenges in following medication and attending school, but ultimately dropping out because of the differences in age between her and her classmates. In addition to age gaps with peers due to health conditions, participants indicated that having gaps in school due to health-related leaves created significant challenges to keep up with peers academically.

I had to abandon school to undergo this surgery and by the time I returned, my colleagues were in Form 3… The headmaster wanted me to sit for the Senior Secondary School Certificate Exams if I wanted to but I felt that I wasn’t ready because I had been away for a long while. No matter how brilliant you are when you stay out of class you lose track of things. (Male, VI, Ghana)

A number of participants indicated that they dropped out of school temporarily to seek health care, but did not get the healthcare they needed and therefore did not ultimately return to school. In addition to health challenges brought about by disability, several participants in Ethiopia and Ghana indicated leaving their education earlier than desired due to pregnancy.

In grade 10, I got married and I was pregnant. Because of birth, I dropped out of school. In fact, my husband encouraged me to complete my education … Even if I am currently begging, I always thank God and I have a plan to complete grade 10. I hope I will get support. (Female, PI, Ethiopia)

Although some participants withdrew from education because they got pregnant, others stopped schooling for other reasons (e.g. limited finances, lack of accessibility), and then got pregnant and did not return to education because of that.

The problem I faced was that though I am deaf, I learned with hearing students. There was no language translator to communicate with them. I was copying all the lessons from others as I could not listen to my teachers. I withdrew from my school and soon I got pregnant. Then, I started caring for my child instead of going to school. (Female, HI, Ethiopia)

—

When I completed JHS, I had wanted to continue with my education but my father asked me to wait and in the process, I got pregnant. This is why I did not continue school. (Female, HI, Ghana)

One participant indicated that she had a child while a student, but she felt very well-supported by her school community.

I remember that both students and teachers were very much supportive when I was in school. I thank them for that. When I found out that I got pregnant, they were caring for me even after I delivered the baby. Some former classmates of mine are still helping me and my child with our expenses. (Female, PI, Ethiopia)

Discussion

This study’s findings indicate factors that influenced youth with disabilities in Ethiopia, Ghana and South Africa to not attend school or leave education sooner than desired. There were many consistent experiences across all three study sites, despite the different cultural, political, social and economic aspects of each country. This consistency may indicate that although there are local nuances to experience, youth with disabilities in these three sites experience similar social, environmental, and health barriers. Many participants expressed the need to access financial resources to fund their tuition fees and additional support needs such as assistive devices and equipment.

The strongest factor leading to the discontinuation of education across all contexts was the loss of key social support networks and relationships. Participants credited much of their success and inclusion to their supportive relationships. They indicated the essential role that family, peers, mentors, teachers, school staff, personal assistants, and other community members played in supporting them financially and emotionally, assisting them with their academics, and providing disability-related supports in their daily lives. The importance of support networks for persons with disabilities is evident in the literature. Family is a key source of care and supports for people with disabilities through their life course (Grossman & Magaña, Citation2016). Apart from family, supports from various sources, such as friends, neighbours, and social groups, also contribute to the quality of life of persons with disabilities (Holanda et al., Citation2015). The widening of support networks can increase the social participation of persons with disabilities, ease their feelings of loneliness and isolation, and lighten the amount of work done by family members (Holanda et al., Citation2015).

This study revealed that it was especially challenging for students with disabilities who lost their parents or grandparents to continue their education as they lost key sources of financial and emotional support. This finding highlights the need for close monitoring of support and relationships to ensure their loss does not lead to drop out. Schools and universities can establish peer support programs for students to connect and support each other. Furthermore, we suggest ministries of education, school governing bodies, and university councils must advocate for schools and universities to employ staff with disabilities who become role models so that students can see that they are able to succeed and pursue further education to be employable (Lindsay, Hartman, & Fellin, Citation2015). Non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and religious organisations could form support networks across community organisations and schools or universities to ensure that students with disabilities are able to socialise outside their families.

Stigma and discriminatory attitudes towards participants were a factor that came up frequently in all sites. Stigma, as defined by Link and Phelan (Citation2001), is when ‘labeling, stereotyping, separation, status loss, and discrimination occur together in a power situation that allows them’ (p. 377). Our findings indicated that participants had experiences of stigma in relation to their abilities to succeed at school and extracurricular activities, where they were deemed less capable because of their disabilities. Participants expressed discrimination towards disability and how families treat their children with disabilities differently than their children without disabilities by often limiting the participation, hiding them away from society and not educating them. Experiencing negative attitudes affects children with disabilities’ sense of themselves (Barg, Armstrong, Hetz, & Latimer, Citation2010). Guarneri, Oberleitner, and Connolly (Citation2019) claim that experiences of stigmatisation and self-stigmatisation can have negative consequences on a learner’s ability to perform academically, affect their involvement in extracurricular activities, and impact their mental well-being. Participants expressed the futility they felt as cultural beliefs limited their participation and inclusion in everyday activities. The experiences of being bullied, mocked, and teased at school by peers for their differences led to serious consequences, such as low self-esteem, dropping out of classes, and social isolation.

Low expectations from family, school, and the community were also commonly experienced by the participants. A large body of literature indicates that expectations from teachers, school, and parents affect students’ educational outcomes and self-perceptions, although the degree of effect varies based on contexts or individuals (Carpenter, Flowers, Mertens, & Mulhall, Citation2004; Johnston, Wildy, & Shand, Citation2019; Rubie‐Davies, Citation2006; Tsiplakides & Keramida, Citation2010). Setting high expectations for all students motivates students with disabilities to achieve their full potential and helps other students develop an understanding that students with disabilities are as capable as their peers (Milsom, Citation2006). Research also indicates that there can be a discrepancy between teacher expectations and student-perceived expectations of teachers, thus highlighting the importance of communicating high expectations to students clearly (Carpenter, Flowers, Mertens, & Mulhall, Citation2004). As students react to the expectations that people hold of them (Johnston, Wildy, & Shand, Citation2019), the present study suggests that teachers, school administrators, staff support as well as families need to consistently have high expectations for students with disabilities, communicate those expectations clearly, and support them to meet those high expectations.

Many participants attested to the inaccessible built environment and exclusionary spaces in their schools, especially for participants who use mobility devices, and those who are visually impaired. In line with other studies conducted in Ethiopia, Ghana, and South Africa (Ackah-Jnr & Danso, Citation2019; Debele, Citation2016; Vincent & Chiwandire, Citation2017), this study highlights the need to improve accessible environments for students with disabilities. Relevant government ministries must ensure disability inclusion in policy implementation to facilitate environmental accessibility of educational facilities. It is critical to provide the assistive devices, technology, and learning materials, such as braille books, that students with disabilities need to continue their education (Fernandez-Batanero, Montenegro-Rueda, Fernandez-Cerero, & Garcia-Martinez, Citation2022; Nasiforo & Ntawiha, Citation2021). In the present study, when devices and technology were not available, participants depended on other students to complete their schoolwork. Having to ‘beg’ for assistance exacerbated their feelings of dependency and frustration and hindered them from succeeding and transitioning through the education system.

Students who were deaf or hard of hearing reported positive experiences in segregated schools and expressed communication challenges in inclusive schools due to the lack of teachers trained in sign language. Previous research also pointed out the barriers that deaf or hard of hearing students experienced in the general education classroom, including the lack of qualified teachers to teach deaf or hard of hearing students, lack of sign language interpreters, lack of awareness of the characteristics and needs of deaf or hard of hearing students, and limited class participation of deaf or hard of hearing students (K. Alasim, Citation2020; K. N. Alasim, Citation2018; Alves, de Souza, Grenier, & Lieberman, Citation2021). The CRPD explicitly notes that States Parties shall ensure ‘the education of persons, and in particular children, who are blind, deaf or deafblind, is delivered in the most appropriate languages and modes and means of communication for the individual’ and shall take measures to hire teachers who have qualifications in sign language (United Nations, Citation2006, p. 17). Our study further underscores the necessity for Deaf students to receive quality education in their language of choice. Inclusion needs to be understood by the ‘experience of students rather than by a placement or location alone’ and there are various educational settings that meet the linguistic and cultural needs of deaf or hard of hearing students (Murray, Snoddon, De Meulder, & Underwood, Citation2020, p. 702). Given the boundaries of this study, deeper research that specifically explores the needs and experiences of Deaf students as it relates to educational success in Africa is warranted.

Another issue revealed in the study was the effect of pregnancy on school dropout – particularly in Ethiopia and Ghana. Some participants indicated that they left their education due to pregnancy, and others indicated that they left their education due to other factors and then they became pregnant. This finding aligns with the findings of Birchall (Citation2018) who indicated that ‘early marriage and pregnancy can be both the cause and consequence of dropping out of school’ (p. 2). A Ghanaian study indicated that sex education is often inaccessible to persons with disabilities (Shamrock & Ginn, Citation2021). UN Women (Citation2020) indicated that women and girls with disabilities are highly vulnerable to sexual and gender-based violence in African countries. We suggest that to best support the education of youth with disabilities to the level that they desire, comprehensive sex education is critical.

This study is not without limitations. For example, although we attempted to have a diversity of impairment type represented in the focus groups, there were significantly more participants with a physical impairment, and the perspectives of persons with intellectual and psychosocial impairments were not captured at all. Future research might seek to target people in these impairment categories specifically to understand how their experiences align or differ with this study’s findings. Additionally, although we implemented rigorous translation processes, we anticipate that there is some potential loss of meaning for the Ethiopian focus groups, given their translation from the original Amharic text. To further mitigate meaning loss, all Amharic focus groups were initially analysed in Amharic by Ethiopian team members, and bilingual Ethiopian team members also participated in and verified accuracy of later stages of analysis. Finally, due to participants not showing up at the scheduled focus group time, some focus group discussions did not have our ideal 6–8 participant number, meaning some of the conversations may have been less rich or multifaced than they could have been.

Conclusion

To conclude, we find it appropriate to reflect on the notion of interdependence that was illustrated in many of the interactions that participants shared with family members, teachers, friends, their peers and classmates without impairments. These interactions facilitated participation and inclusion in the education systems. It may be helpful to frame recommendations from the perspective of Tronto’s (Citation1993) feminist ethics of care, namely, attentiveness, responsibility, competence, responsiveness, and integrity. Attentiveness requires that family members, staff in schools and universities are attentive to the actual needs of students with disabilities. Responsibility means that students with disabilities who are in need of accommodations are able to state their needs and deliberate around their priorities. Competence is understanding that people who engage with students with disabilities require a certain level of skill appropriate to the context (e.g. teachers of Deaf students). Responsiveness implies that the support given happens in relational terms to ensure that the support provided meets the needs of students, who in turn are able to respond. Integrity means that support and care given alleviates affliction. Being attentive to the needs of youth with disabilities, being able to respond with the necessary help and resources, family members encouraging young girls who became pregnant to go back to complete their education, staff addressing the experiences of shame, teasing and bullying, and strangers helping navigate a muddy road, show the interdependence and ethics of care that can help reduce the number of youth with disabilities who do not complete school or university.

Acknowledgments

The co-authors would like to express deep appreciation to all this study’s participants for sharing their stories with our team. We would also like to acknowledge the other members of the overall Transitions of Youth with Disabilities in Education Systems team who are not listed as authors on this manuscript, including Benedicta Apambila, Raymond Ayivor, Araba Botchway, Rose Dodd, Hamdia Mahama, Melkitu Melak, Nina Okoroafor, and Kegnie Shitu. This study was funded by the Mastercard Foundation Scholars Program’s Partners Research Funds.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Throughout manuscript text: PI = Physical Impairment; HI = Hearing Impairment; VI = Visual Impairment.

References

- Ackah-Jnr, F. R., & Danso, J. B. (2019). Examining the physical environment of Ghanaian inclusive schools: How accessible, suitable and appropriate is such environment for inclusive education? International Journal of Inclusive Education, 23(2), 188–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2018.1427808

- ACPF. (2011). The lives of children with disabilities in Africa: A glimpse into a hidden world.Addis Ababa: The African child policy forum. Retrieved from https://www.firah.org/upload/notices3/2011/lives_of_children_with_disabilities_in_africa.pdf

- Alasim, K. (2020). Inclusion programmes for students who are deaf and hard of hearing in Saudi Arabia: Issues and recommendations. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 67(6), 571–591. https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912X.2019.1628184

- Alasim, K. N. (2018). Participation and interaction of deaf and hard-of-hearing students in inclusion classroom. International Journal of Special Education, 33(2), 493–506.

- Alves, M. L. M., de Souza, J. V., Grenier, M., & Lieberman, L. (2021). The invisible student in physical education classes: Voices from deaf and hard of hearing students on inclusion. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2021.1931718

- Barg, C., Armstrong, B., Hetz, S., & Latimer, A. (2010). Physical disability, stigma, and physical activity in children. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 57(4), 371–382. https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912X.2010.524417

- Birchall, J. (2018). Early marriage, pregnancy and girl child school dropout. K4D Helpdesk Report. Institute of Development Studies.

- Bost, L. W., & Riccomini, P. J. (2006). Effective instruction: An inconspicuous strategy for dropout prevention. Remedial and Special Education, 27(5), 301–311. https://doi.org/10.1177/07419325060270050501

- Carpenter, D. M., Flowers, N., Mertens, S. B., & Mulhall, P. F. (2004). High expectations for every student. Middle School Journal, 35(5), 64–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/00940771.2004.11461454

- Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory (2nd ed.). Sage.

- Chataika, T., Mckenzie, J. A., Swart, E., & Lyner-Cleophas, M. (2012). Access to education in Africa: Responding to the United Nations convention on the rights of persons with disabilities. Disability & Society, 27(3), 385–398. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2012.654989

- Cramm, J. M., Neiboer, A. P., Finkenflugel, H., & Lorenzo, T. (2013). Comparison of barriers to employment among youth with and without disabilities in South Africa. Work, 46(1), 19–24.

- Debele, A. F. (2016). The study of accessibility of the physical environment of primary schools to implement inclusive education: The case of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Imperial Journal of Interdisciplinary Research, 2(1), 26–36.

- Devries, K. M., Kyegombe, N., Zuurmond, M., Parkes, J., Child, J. C., Walakira, E. J., & Naker, D. (2014). Violence against primary school children with disabilities in Uganda: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 14(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-1017

- Fernandez-Batanero, J. M., Montenegro-Rueda, M., Fernandez-Cerero, J., & Garcia-Martinez, I. (2022). Assistive technology for the inclusion of students with disabilities: A systematic review. Educational Technology Research & Development, 70(5), 1911–1930. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-022-10127-7

- Grossman, B. R., & Magaña, S. (2016). Introduction to the special issue: Family support of persons with disabilities across the life course. Journal of Family Social Work, 19(4), 237–251. https://doi.org/10.1080/10522158.2016.1234272

- Guarneri, J. A., Oberleitner, D. E., & Connolly, S. (2019). Perceived stigma and self-stigma in college students: A literature review and implications for practice and research. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 41(1), 48–62. Online. https://doi.org/10.1080/01973533.2018.1550723

- Holanda, C. M. D. A., Andrade, F. L. J. P. D., Bezerra, M. A., Nascimento, J. P. D. S., Neves, R. D. F., Alves, S. B., & Ribeiro, K. S. Q. S. (2015). Support networks and people with physical disabilities: Social inclusion and access to health services. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 20(1), 175–184. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232014201.19012013

- Jagosh, J., Macaulay, A. C., Pluye, P., Salsberg, J., Bush, P. L., Henderson, J. et al. (2012). Uncovering the benefits of participatory research: Implications of a realist review for health research and practice. The Milbank Quarterly, 90(2), 311–346.

- Jesus, T. S., Bhattacharjya, S., Papadimitriou, C., Bogdanova, Y., Bentley, J., Arango-Lasprilla, J. C., & Refugee Empowerment Task Force, International Networking Group of the American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine. (2021). Lockdown-related disparities experienced by people with disabilities during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic: Scoping review with thematic analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(12), 6178.

- Johnston, O., Wildy, H., & Shand, J. (2019). A decade of teacher expectations research 2008–2018: Historical foundations, new developments, and future pathways. Australian Journal of Education, 63(1), 44–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004944118824420

- Lindsay, S., Hartman, L. R., & Fellin, M. (2015). A systematic review of mentorship programs to facilitate transition to post-secondary education and employment for youth and young adults with disabilities. Disability and Rehabilitation, 38(14), 1329–1349. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2015.1092174

- Link, B. G., & Phelan, J. C. (2001). Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology, 27(1), 363–385. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.363

- Milsom, A. (2006). Creating positive school experiences for students with disabilities. Professional School Counseling, 10(1), 66–72. https://doi.org/10.5330/prsc.10.1.ek6317552h2kh4m6

- Murray, J. J., Snoddon, K., De Meulder, M., & Underwood, K. (2020). Intersectional inclusion for deaf learners: Moving beyond general comment no. 4 on article 24 of the United Nations convention on the rights of persons with disabilities. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 24(7), 691–705. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2018.1482013

- Musau, Z. (2018). Africa grapples with huge disparities in education. Africa Renewal, Africa Renewal. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/africarenewal/magazine/issue/december-2017-march-2018

- Nasiforo, B. M., & Ntawiha, P. (2021). Provision of assistive resources for learners with visual impairment in colleges of the University of Rwanda. Rwandan Journal of Education, 5(1), 21–30.

- Rubie‐Davies, C. M. (2006). Teacher expectations and student self‐perceptions: Exploring relationships. Psychology in the Schools, 43(5), 537–552. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.20169

- Rust, T., & Metts, R. (2007). Poverty and disability: Trapped in a web of causation. Northampton: Regional and Urban Modeling, 284100032. https://ecomod.net/sites/default/files/document-conference/ecomod2007-rum/181.pdf.

- Salsberg, J., Macaulay, A. C., & Parry, D. (2014). Guide to integrated knowledge translation research, In I. D. Graham, J. Tetroe & A. Pearson (Eds.), turning knowledge into action: Practical guidance on how to do integrated knowledge translation research. Wolters Kluwer, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- Shamrock, O. W., & Ginn, H. G. (2021). Disability and sexuality: Toward a focus on sexuality education in Ghana. Sexuality and Disability, 39(4), 629–645. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-021-09699-8

- Stalker, K., & McArthur, K. (2012). Child abuse, child protection and disabled children: A review of recent research. Child Abuse Review, 21(1), 24–40. https://doi.org/10.1002/car.1154

- Tronto, J. (1993). Moral boundaries: A political argument for an ethic of care. Routledge.

- Tsiplakides, I., & Keramida, A. (2010). The relationship between teacher expectations and student achievement in the teaching of English as a foreign language. English Language Teaching, 3(2), 22–26. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v3n2p22

- UNESCO. (2018). Education and disability: Analysis of data from 49 countries. Retrieved from https://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents/ip49-education-disability-2018-en.pdf

- UNESCO. (2020). Global education monitoring report 2020: Inclusion and education: All means all. UNESCO. Retrieved from https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000373718

- UNICEF. (2017). Inclusive education: Understanding article 24 of the United Nations Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities. Retrieved from https://www.unicef.org/eca/sites/unicef.org.eca/files/IE_summary_accessible_220917_0.pdf

- United Nations. (2006). Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities. https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities-2.html

- UN Women. (2020). Mapping of discrimination against women and girls with disabilities in east & Southern Africa. https://africa.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/Field%20Office%20Africa/Attachments/Publications/2020/Mapping%20of%20Discrimination%20Against%20Women%20and%20Girls%20With%20Disability-Web.pdf

- Vincent, L., & Chiwandire, D. (2017). Wheelchair users, access and exclusion in South African higher education. African Journal of Disability, 6(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.4102/ajod.v6i0.353

- Zablocki, M., & Krezmien, M. P. (2013). Drop-out predictors among students with high-incidence disabilities: A national longitudinal and transitional study 2 analysis. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 24(1), 53–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/1044207311427726