ABSTRACT

School leadership practices that promote inclusion for students with special educational needs have received significant attention in the literature. However, few studies have examined the psychometric properties of scales to evaluate principals’ inclusive leadership practices in the Asian, specifically Malaysian, context. This study examined the dimensionality, reliability, and validity of a scale testing inclusive leadership in Malaysian schools. A total of 604 responses were collected from teachers working at 63 public primary and secondary schools in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. The study was conducted across two phases. In phase 1, the construct validity of the scale for Malaysian principals’ inclusive leadership practices was established using exploratory factor analysis. In phase 2, a confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to assess the dimensionality, reliability, convergent, and discriminant validity of the scale. Results supported a two-factor, 29-item scale. The scale may be utilised as a reliable and valid instrument for examining principals’ inclusive school leadership practices in the Malaysian context.

Introduction

The Salamanca Statement (UNESCO, Citation1994) is arguably the most significant international document in the field of special education. It endorsed the idea of inclusive education, which became a major global influence in subsequent years. More than 92 nations signed on to advocating equal educational opportunity and access for all students, including those with special educational needs (SENs) (UNESCO, Citation2020). After this, many education systems began to implement policies and programmes that enabled schools to serve all children, particularly those with SENs (Adams et al., Citation2020), as full inclusion is only possible if mainstream schools are capable of educating all children in their communities (Tan & Adams, Citation2021; UNESCO, Citation2020).

The Malaysian Education Act Citation1996 (1998) mandates children’s right to equal education without discrimination. Schools are mandated to accept students with SENs, provide inclusive educational opportunities and offer support and facilities to meet their needs (Adams et al., Citation2017, 2020; Jelas & Ali, Citation2014). The Malaysia Education Blueprint 2013–2025 (Ministry of Education, Citation2012) further emphasises the national commitment to an inclusive education model. Among the key transformation and changes required in the Blueprint was the commitment that, by 2025, 75% of children with special needs will be enrolled in inclusive programmes, and high-quality education will be provided to every child with SENs. At all levels of the educational system, leadership is a crucial factor in supporting inclusive school development (Adams et al., Citation2020; DeMatthews et al., Citation2020; UNESCO, Citation2020).

School leadership practices that promote inclusion for students with SENs have been the subject of many investigations in the literature (see Adams, Citation2020, Billingsley et al., Citation2019; DeMatthews et al., Citation2020). In schools, principals are instrumental in driving the culture and focusing on inclusion as well as promoting equality and equity, which are critical in promoting learning for all students and particularly for students with SENs (Swaffield & Major, Citation2019; UNESCO, Citation2017). A range of instruments with various dimensions have been used for measuring school leadership in inclusive education, depicting the inconsistencies in determining the psychometric properties of the construct (e.g. Billingsley et al., Citation2019; DeMatthews et al., Citation2021a; Swaffield & Major, Citation2019). However, few such studies have been conducted in the Asian, specifically Malaysian, context (Adams et al., Citation2023). This research aims to close this gap.

This study validated an instrument for use in measuring principals’ inclusive school leadership practices in the context of Malaysia. The research question that guided the study was as follows: what are the dimensions of inclusive school leadership practices in Malaysia? The study offers future directions for assessing school principals’ inclusive leadership practices in the given context.

Sociocultural Theory

A sociocultural perspective highlights the mutual influences between individuals and their immediate surroundings. This includes individual learning in interaction with others within learning context (Rogoff, Citation2003). Vygotsky concentrated on the inter-relationships that occur between individual learning and its relation to language, environmental arrangements, aspects of curriculum over time (Beneke et al., Citation2020; Vygotsky, Citation1978). For example, through school principals’ interactions with teachers and students, particularly students with SENs in their schools, principals learn and construct meanings of inclusive education. Further, principals’ knowledge, abilities and attitudes establish and sustain inclusive practices in their schools (Lyons, Citation2016). Cultural adaptation in the validation of an instrument through a sociocultural lens is important to ensure the validity and relevance of the instrument across diverse contexts. Therefore, applying sociocultural theory for this study is a crucial step to ensure the validity of the instrument in the context of Malaysia.

Inclusive School Leadership

Interest in the area of leadership and its effectiveness is widespread among both researchers and practicing leaders (Adams et al., Citation2023; Gómez-Leal et al., Citation2022; Sebastian et al., Citation2019). However, the interpretation of the term ‘leadership’ by researchers and practitioners varies greatly. Here, we consider it to be the process ‘whereby an individual person influences a group of individuals to achieve a common goal’ (Sharma & Jain, Citation2013, p. 310). The process of leadership involves the management of people’s emotions, thoughts, and actions to achieve organisational goals (Oskarsdottir et al., Citation2020). A leader can persuade others by applying leadership knowledge and skills, directing the organisation in a cohesive and coherent manner in which everyone has a chance to grow to fulfil their full potential (Uljens, Citation2018).

A growing body of research and educational theories offer immense support for the notion that principals’ leadership contributes to improved school performance (Sebastian et al., Citation2019) and student learning (Adams, Citation2018, Gómez-Leal et al., Citation2022; Adams et al., Citation2017; Sebastian et al., Citation2019) in their schools. From a wide range of global evidence (Day et al., Citation2016; Leithwood et al., Citation2006), four broad categories emerge that indicate successful school leadership practices; (1) setting direction, (2) developing people, (3) restructuring the organization, and (4) managing instructional programmes. Researchers and educators have proposed a range of other conceptual models to explain how leadership can impact student learning (Hallinger & Wang, Citation2015; Leithwood et al., Citation2020; Robinson et al., Citation2008).

School leadership has been shown to successfully enable inclusive education for students with SENs. Numerous studies have shown the important role of leadership in establishing successful inclusive schools (DeMatthews et al., Citation2020; DeMatthews, Citation2020; Hoppey & McLeskey, Citation2013; Kozleski, Citation2019; Waldron et al., Citation2011). These researchers show that leadership is crucial for the development of inclusive schools that seek to cater to the academic, social, and emotional needs of all students, including those with SENs. Principals must have certain information, abilities, and attitudes to collaborate effectively with important stakeholders and establish and sustain inclusive practices in their schools (Lyons, Citation2016). In the same manner, strengthening a principal’s capacity to enhance organisational performance, school climate, and teacher cooperation can produce an indirect impact on student achievement (Orphanos & Orr, Citation2014). Principals who are equipped with this knowledge and these competencies are better able to improve education delivery, comprehend student needs, encourage school-family collaboration, and eliminate segregated programmes (DeMatthews et al., Citation2020).

Oskarsdottir et al. (Citation2020) developed a model that was specifically focused on inclusive school leadership practices. In this model, inclusive school leadership is made up of a combination of three core functions of leadership: (1) setting direction and building a vision, (2) human development, and (3) organizational development. Due to their central focus on valuing all learners in the learning community, Oskarsdottir et al. (Citation2020) consider that these three broad areas of the inclusive school leadership model can influence and support leaders’ core functions in the school community. Similarly, Billingsley et al. (Citation2019) suggest that inclusive leadership in schools includes four major functions: (1) creating a school-wide vision for inclusive education, (2) supporting professional learning communities, (3) redesigning schools for inclusive education, and (4) sharing leadership with others. These four functions were identified in an extensive review of recent research related to the role of the school principal in addressing the needs of students with SENs (Billingsley et al., Citation2019).

In this paper, we defined inclusive school leadership with reference to the commitment of principals to promoting equity and fairness in building the school community and promoting the full participation of all students. According to this definition, which is in line with the articulation of other researchers, principals should ensure the full participation and contribution of the staff to create and sustain the learning community and support everyone to reach their maximum potential. This is supported by DeMatthews (Citation2015), for whom principals are responsible for establishing a welcoming environment for all children, selecting faculty and staff that uphold inclusive beliefs and practices, formalising structures that allow teachers to use data for tracking student development and fix problems and allocating resources in the most effective and flexible way possible, as well as Oskarsdottir et al. (Citation2019).

The School As an Inclusive Community

The idea of the inclusive school is rooted in the concept of inclusive education, although some consider it to be an ideological concept (Allan, Citation2014). In inclusive education, regardless of the challenges, students are enrolled in age-appropriate general education classes, where they can ideally receive excellent instruction and support commensurate with their abilities to help them succeed in the core curriculum (Oskarsdottir et al., Citation2019). Leaders of inclusive schools need to ensure that their schools and classrooms operate on the understanding that students with SENs are as fundamentally competent as their abled peers. Overarching this belief, parameters need to be established by principals who commit to developing inclusive communities by emphasising non-discrimination and preventing exclusion on the basis of disability (Billingsley et al., Citation2019; Kefallinou et al., Citation2020). The underpinning of inclusive leadership therefore resides in enhancing involvement and representation among all teachers, administrators, and students, as well as in the entirety of the school (Moya et al., Citation2020).

As an inclusive community, a school respects the right of all learners to quality education (Kefallinou et al., Citation2020). It focuses on increasing participation for all learners, creating systems that value all individuals equally, and promoting equity, compassion, human rights, and respect (DeMatthews et al., Citation2020). In a school community, the principal provides leadership in assessing curricular materials, staffing, and resource allocation, reconfiguring resources as needed (Causton & Theoharis, Citation2014; Lyons, Citation2016). Likewise, the principal shows commitment to inclusivity though discussions about the meaning of diversity, understanding of and beliefs related to dis/ability, and the values associated with the inclusive approach (Causton-Theoharis et al., Citation2011; Lyons, Citation2016). Principals also establish a clear direction for building and sustaining the learning community (Hoppey & McLeskey, Citation2013; Oskarsdottir et al., 2019). School leaders who promote inclusivity will re-examine priorities and make informed decisions based on the evidence (Billingsley et al., Citation2018a; DeMatthews et al., Citation2020; Robinson et al., Citation2015). All of these attributes resonate with consistent and interrelated leadership practices that are evident in a school that forms an inclusive community.

Management of Teaching and Learning Process

Segregated schools have a curriculum, teaching and evaluation methods, facilities, and specialised teachers and staff, based on the type of disabilities experienced by their students (Kassah et al., Citation2018; Nag et al., Citation2021; Robiyansah et al., Citation2020). Unlike a segregated setup, inclusive schools ensure that students with SENs are educated in mainstream classes together with their abled peers (Kefallinou et al., Citation2020; Robiyansah et al., Citation2020; Sakiz, Citation2017). School principals and teachers collaborate to ensure that all students learn successfully, including students with SENs. Teachers, therefore, need to be equipped with the requisite knowledge, skills, and attitudes to teach students with SENs in mainstream classrooms (Adams et al., Citation2021, Moberg et al., Citation2020; Saloviita, Citation2020).

To manage teaching and learning among students with SENs in inclusive schools, principals must provide a shared vision and support systems that will promote inclusive practices (UNESCO, Citation1994). Strong leadership, driven by a clear vision of inclusion, plays a major role in envisioning, evaluating, and strengthening family – school – community partnerships (Kefallinou et al., Citation2020). Likewise, increasing instructional awareness, holding discussions on social inclusion, and fostering participation within and beyond the school community are essential components in making teachers and the school community sufficiently competent and motivated to sustain an inclusive effort (Gross et al., Citation2015; Poulos et al., Citation2014).

Further, inclusive education focuses on the preparation of high-quality individualised educational programs (IEPs) to meet the learning needs of students with SENs in mainstream classroom settings (Sakiz, Citation2017; Timothy & Agbenyega, Citation2018). In developing IEPs, a team of educators and classroom assistants sets goals and formulates the classroom instructions that students with SENs will receive (Sakiz, Citation2017; Sharma et al., Citation2016). Then, parents are notified of their child’s learning progress (Adams et al., Citation2016; Muega, Citation2016). However, the adoption of this type of personalised approach to promote teaching and learning requires principals to ensure adequate infrastructure and resources to facilitate the learning process of each individual student in the classroom (Kefallinou et al., Citation2020; Rowe et al., Citation2012).

The preceding review of the literature indicates that two components, namely, (i) the school as an inclusive community and (ii) the management of teaching-learning processes be crucial components in the measure of a principal’s inclusive school leadership practices. Hence, in this study, principals; inclusive school leadership practices are broadly defined as the principal’s commitment to promoting equity and fairness for building the school community and providing a shared vision of inclusion in education.

Methodology

Data Collection

Data for this study were drawn from a survey on inclusive school leadership practices carried out in Malaysia. A total of 604 responses were collected from teachers at 63 public primary and secondary schools in Kuala Lumpur, with a response rate of 73%. To ensure adherence to ethical standards, permission to collect data was sought from the Ministry of Education of Malaysia before contacting the teachers for data collection. All participation in this study was voluntary, and the anonymity and confidentiality of respondents were guaranteed during the process of data collection.

Participant Characteristics

Of the 604 respondents, 369 (61.1%) were teaching at primary schools and 235 (38.9%) were at secondary schools. The majority of respondents, 495 (82%), were female, and 109 (18%) were male teachers. Most (538) teachers had a bachelor’s degree (89.1%), followed by 51 with a master’s degree (8.4%) and 15 with a diploma certificate (2.5%). All had experience teaching students with SENs. Their experience ranged across less than 5 years (119 teachers), 5 to 10 years (206), 11 to 15 years (178), 16 to 20 years (48), and more than 20 years (53). presents the demographic breakdown of the participants.

Table 1. Demographic profile of respondents.

Instrument

The instrument used in this study was adapted from the inclusive leadership in schools (LEI-Q) survey developed by Moya et al. (Citation2020). This instrument consists of 40 items and is used to capture the perception of teachers regarding their principal’s inclusive school leadership practices. These items test two constructs (1) The school as an inclusive community, and (2) Management of the teaching-learning processes; they were to be rated across four response options, from (Not implemented) through 2 (Partially implemented), 3 (Substantially implemented), and 4 (Fully implemented). The reliability of the two scales were α = 0.971 and α = 0.975, respectively.

We first reviewed the two constructs and the 40 items in terms of the suitability, clarity, and interpretation for the Malaysian context. The review panel consisted of three lecturers in educational management and leadership from two local public universities, three researchers of the current study, and one doctorate student who was studying inclusive school leadership in primary schools, one school head teacher, and one teacher. The panel agreed that the two constructs were multidimensional, and its 32 items were found relevant to the Malaysian principal’s inclusive school leadership practices. However, minor adjustments were made to the terminologies in the items for better alignment with the local context. Notably, 8 items were excluded from the original 40-item scale developed by Moya et al. (Citation2020). The decision to remove these items was not arbitrary; rather, it emanated from a rigorous consideration of their applicability within the Malaysian cultural and educational context. For example, items such as ‘enables the different members of the educational community to participate in the evaluation of management tasks’, ‘establishes sanctions for the use of symbols and actions that promote exclusion’ and ‘establishes mechanisms to promote the participation of students in the regulation of conflicts that arise in the school environment’ were found to be less relevant due to specific cultural nuances and contextual differences.

Specifically, within the Malaysian cultural context, how people respect authority and follow clear structures is important. In our culture, openly judging how leaders manage tasks might be seen as questioning their authority. Also, giving punishments for symbolic actions may clash with the prevailing cultural emphasis on harmony. Likewise, allowing students to take part in solving conflicts, while a valuable practice in other cultural settings, might be seen differently here where teachers usually handle such matters without student involvement. Thus, the adaptation of this scale was guided by a commitment to ensuring the scale’s sensitivity to the unique characteristics of Malaysian schools, thus contributing to the validity and reliability of our assessment.

The final questionnaire consisted of two parts. The first part collected data on the teachers’ demographic information, including school type, gender, educational qualification, and teaching experience in SEN. The second part consisted of the 32 items based on two sub-constructs: “(1) The school as an inclusive community, in 12 items, and (2) Management of teaching-learning processes, in 20 items. A 5-point Likert-type scale was used, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). A sample item from the first dimension follows: ‘My principal promotes initiatives that foster the participation of school community in the educational process’, and a sample item from the second dimension follows: ‘My principal encourages teachers to communicate situations of discrimination that occurs in the school’.

Data Analysis

A variety of procedures can be used for tool validation, but the current investigation engaged the three stages of (i) item development, (ii) scale development, and (iii) scale evaluation, following the suggestion of Boateng et al. (Citation2018). For the statistical analysis, this study employed both an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). However, following the strong recommendation not to conduct both EFA and CFA on the same data (Ramayah et al., Citation2018), the sample was split into two data sets to enable one to be used for EFA and the other for CFA. Given that there were 32 items in the questionnaire, a minimum sample of 200 is sufficient for an EFA, based on sample recommendations ranging from 3 to 20 responses per variable by Mundfrom et al. (Citation2005). The random split feature in Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) 25 was employed to select the sample from the dataset. The remaining sample of 404 responses was adequate for conducting a CFA (Kline, Citation2015; Muthén & Muthén, Citation2002) and was so used.

Data Cleaning and Preparation

Data cleaning and preparation were the first actions conducted in examining the dataset. In this stage, suspicious and inconsistent responses were assessed, using the straight lining method (Hair et al., 2010). No critical issues were identified at this stage. However, in seven cases, teachers responded that they had not taught SEN classes. These cases were omitted, leaving a final sample size of 604. The dataset was further explored using minimum and maximum values, means, and standard deviation, and its distribution was examined through checking univariate skewness and kurtosis. The results of these analyses are displayed in .

Table 2. Descriptive statistics for the questionnaire items.

As noted in , the responses are generally evenly spread out across the scale, as indicated by the range and minimum and maximum values. With the exception of the item IL_SIC4, the items were assigned both maximum and minimum scores by the respondents. The means for the items seem to be slightly on the higher end of the scale (between 3.538 and 3.972) while the standard deviations (SDs) indicate no extraordinary deviations of data from the mean (SDs between 0.778 and 0.916). For the distribution patterns of the data, the recommendations of Curran et al. (Citation1996) were used, such that skewness in the range of −2 to +2 and kurtosis in the range of −7 to +7 are considered not to cause adverse effects on the results of subsequent analyses. The statistics for skewness and kurtosis are thus within the acceptable range.

Findings

Exploratory Factory Analysis (EFA)

This study used specific parameters for performing and assessing EFA. Maximum likelihood with varimax rotation were employed as the method for factor extraction, following the prevailing recommendations (Costello & Osborne, Citation2005; Osborne, Citation2014). Sample adequacy was assessed using the Kaiser – Meyer – Olkin (KMO) measure, in which a value greater than or equal to 0.90 was expected (Pallant, Citation2007). Finally, factors were identified based both on eigenvalues greater than one and on observation of the scree plot (Cattell, Citation1966).

Examination of the SPSS output for the EFA indicates that the sample was statistically adequate for the analysis, as the KMO value was 0.96. Further, using the scree plot shown in and eigenvalues, the items developed for measuring inclusive school leadership in the current study could be grouped into two factors.

shows the rotated factor matrix, in which factor loadings greater than or equal to.50 are displayed. As seen in the table, the majority of items are clearly loaded onto one of the factors. Six items are cross-loaded; these are put under the factor with the higher loading, as indicated in italics. Accordingly, for the results of the EFA, factor 1 (school inclusive community) has 12 items, while factor 2 (managing teaching and learning) consists of 20 items. The two factors explained 77.52% of the variance in inclusive school leadership. As such, this is considered as a high-potential factor structure for measuring inclusive school leadership. Consequently, CFA proceeded with these factors and their associated items to examine their validity and reliability.

Table 3. Rotated factor matrix for two factors.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

As noted, CFA procedures were conducted for the 404 samples with the use of AMOS 23. For CFA, three types of indices (residual-based, parsimonious, and incremental) along with composite reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE) were used in assessing the results. Following recommendations from researchers of structural equation modelling (see Schermelleh-Engel et al., Citation2003; Thakkar, Citation2020), and chi-square (x2) was not used as a criterion for accepting or rejecting the model. summarises the criteria used in this study to evaluate the model fit and to assess validity and reliability.

Table 4. Criteria for model fit indices.

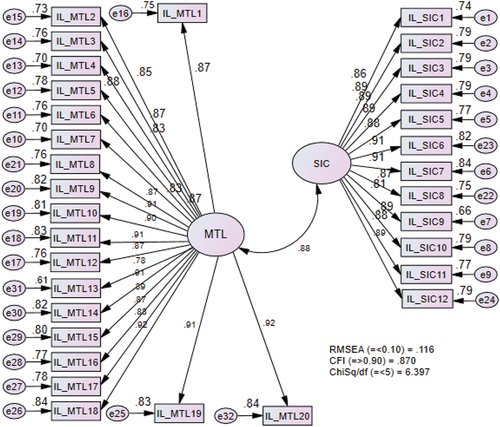

For the initial CFA model (model A, ), despite significant factor loadings (that is, loadings ≥ .40) for the items, none of the fit indices were within the pre-defined cut-off values. Thus, model A did not have acceptable fit to the data per the indices in .

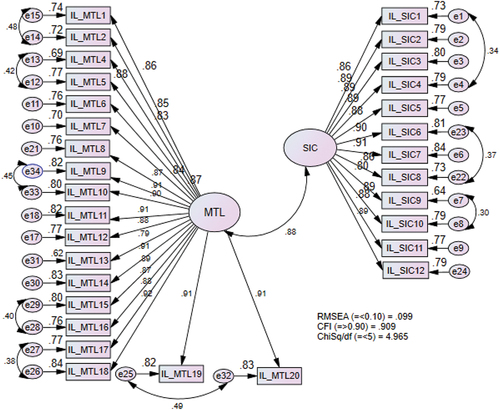

Consequently, the model was modified by drawing co-variances between errors. Moreover, only one item (IL_MTL3) was deleted during the modification. (model B) shows the model after the minimum necessary modifications had been made.

From the fit indices (RMSEA = 0.099; SRMR = 0.037; CMIN/DF = 4.965; CFI = 0.909), the model has reasonable fit to data. Subsequently, the convergent and discriminant validity of the model was assessed. Convergent validity was assessed using AVE (≥0.50) and CR (≥0.70), while discriminant validity was confirmed by ensuring that correlation between the factors is lower than the average variance explained (square root of AVE) due to the factors.

shows the CR, AVE, and correlations for the constructs of model B. From the results presented in , model B passes the threshold for convergent validity, as both CR and AVE are above the minimum cut-off values. However, the model did not achieve discriminant validity, as the correlation between the factors (0.881) was greater than the variance explained by the factors (shown in the √AVE column, ). Thus, model B did not pass the assessment of validity. Subsequently, modifications were obtained by deleting items (item IL_MTL5 and IL_MTL7), which produced some amount of cross-loading in the initial stages of the factor exploration.

Table 5. Assessment of validity: model B.

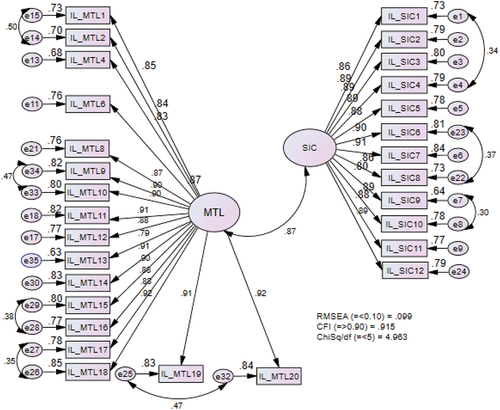

shows the CFA model after the necessary modifications have been made, as stated above. Based on the obtained model fit indices (RMSEA = 0.099; SRMR = 0.037; CMIN/DF = 4.963 CFI = 0.915), the model provides reasonable fit to data. Subsequently, the convergent and discriminant validity of the model were assessed, the results of which are shown in .

Table 6. Assessment of validity: model C.

As seen in , the CR and AVE for model C were both above thresholds for convergent validity. Further, the square root for AVE (√AVE) for each factor is greater than the correlation between the factors (0.874). Thus, model C achieved discriminate validity as well. From this finding, it is evident that school inclusive community (SIC) and managing teaching and learning (MTL) are distinct factors that can be used together to measure inclusive school leadership in the given context.

Discussion

This study tested the dimensionality and assessed the reliability and validity of an instrument to measure inclusive leadership in schools in the context of Malaysia. EFA produced two factors for use in measuring inclusive school leadership. It was found that the modified CFA model (model C) achieved reasonable fit and both convergent and discriminant validity. The findings confirmed that SIC and MTL are acceptable dimensions for use in measuring inclusive school leadership in the Malaysian context.

The identification of inclusive school leadership factors in this study offers crucial insights for school leaders seeking to implement inclusive education, with a particular emphasis on understanding the cultural context. One of the primary aspects of inclusive school leadership is transforming the school into an inclusive community (Moya et al., Citation2020). This study corroborates the core leadership practices identified by D. DeMatthews (Citation2020) for creating effective inclusive schools. These are (i) creating a culture of change-oriented collaboration, (ii) planning and evaluating, (iii) building capacity, and (iv) developing/revising plans. The items in this dimension also provide for explicit leadership practices that school leaders can enact for reforming schools into inclusive communities.

In the Malaysian context, where hierarchical structures and respect for authority are significant cultural factors, the role of principals in creating and promoting inclusive schools becomes more complex. Our instrument, validated for the Malaysian context, becomes a valuable tool for assessing daily inclusive leadership practices, prompting a reconsideration of principals’ roles in implementing inclusive education through a whole-school approach. Principals’ engagement in creating and promoting inclusive schools is essential for the successful inclusion of students with special needs in mainstream classes, aligning with inclusive educational policies and practices (Khaleel et al., Citation2021).

Inclusive school leadership also encompasses the management of teaching and learning (MTL), serving as the core aspect of instructional leadership. Notably, Lambrecht et al. (Citation2022) found that instructional leadership has a direct on the implementation of an Individualized Education Program (IEP). Additionally, principals are required to utilise available autonomy accorded to them to adjust the curriculum and assessment methods, addressing the diverse needs of students with SENs. Additionally, principals must influence teaching and learning through the development of a mechanism that is supportive for all students. Thus, a key responsibility that principals have is supporting the development and utilisation of inclusive pedagogy in mainstream classes (Florian & Beaton, Citation2018). This study raises the possibility that school principals could engage in MTL to a greater degree to increase the level of achievement of all students, particularly among students with SENs.

Finally, the instrument adopted was found to be a valid measure of principals’ inclusive school leadership practices in the Malaysian context. it had a two-factor structure, composed of 29 items with 12 items for SIC and 17 items for MTL. The item analysis in this study showed that the reliabilities of the two factors were acceptable, where the CRs for SIC and MTL were 0.976 and 0.983, respectively. These findings not only validate the instrument but also underscore its relevance and applicability within a unique cultural context, providing a lens through which to understand and enhance inclusive school leadership practices in Malaysia.

Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

Although the scale for principals’ inclusive school leadership practices was validated in the current study, our sample only included teachers in public primary and secondary schools in Kuala Lumpur. Future studies could further validate the scale with teacher samples in other states in Malaysia, especially in the Borneo States, where schools are faced with added challenges, such inadequate educational resources or facilities and poor teacher quality.

Conclusion and Implications

As Malaysia remains committed to an inclusive education model aiming to have 75% of children with special needs enrolled in inclusive programmes by 2025, with a focus on providing high-quality education for every child (Ministry of Education, Citation2012), school principals are key figures in transacting this progress. Thus, the need for assessing a principal’s inclusive leadership practices has become more significant, necessitating the development of a reliable measuring tool. Hence, the primary objective of this study was to validate an instrument that could be used to assess a principal’s inclusive school leadership practices in the Malaysian context. The results of the validation process revealed that the measurement of a principal’s inclusive school leadership practices is composed of two dimensions (i) SIC and (ii) MTL. Building upon this adapted and validated instrument, this scale holds the potential to serve as a reliable and valid tool for examining principals’ inclusive school leadership practices not only in other Malaysian states but also in various Asian contexts.

Acknowledgments

This research is part of the Fundamental Research Grant Scheme FRGS/1/2020/SSI0/UM/02/5 financed by the Ministry of Higher Education, Malaysia.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Adams, D. (2018). Mastering theories of educational leadership and management. University of Malaya Press.

- Adams, D. (2020). Inclusive leadership for inclusive schools. International Online Journal of Educational Leadership, 4(1), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.22452/iojel.vol4no1.1

- Adams, D., Che Ahmad, A., & Kolandavelu, R. (2020). Raising your child with special needs: Guidance and practices. Institut Terjemahan & Buku Malaysia Berhad.

- Adams, D., Harris, A., & Jones, M. S. (2016). Teacher-parent collaboration for an inclusive classroom: Success for every child. Malaysian Online Journal of Educational Sciences, 4(3), 58–72.

- Adams, D., Harris, A., & Jones, M. S. (2017). Exploring teachers’ and parents’ perceptions on social inclusion practices in Malaysia. Pertanika Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, 25(4), 1721–1738.

- Adams, D., Mohamed, A., Moosa, V., & Shareefa, M. (2021). Teachers’ readiness for inclusive education in a developing country: Fantasy or possibility? Educational Studies, 49(6), 896–913. https://doi.org/10.1080/03055698.2021.1908882

- Adams, D., Thien, L. M., Chuin, E. C. Y., & Semaadderi, P. (2023). The elusive Malayan tiger ‘captured’: A systematic review of research on educational leadership and management in Malaysia. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 51(3), 673–692. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143221998697

- Allan, J. (2014). Inclusive education and the arts. Cambridge Journal of Education, 44(4), 511–523. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2014.921282

- Beneke, M. R., Skrtic, T. M., Guan, C., Hyland, S., An, Z. G., Alzahrani, T., Uyanik, H. R., Amilivia, J. M., & Love, H. R. (2020). The mediating role of exclusionary school organizations in pre-service teachers’ constructions of inclusion. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 24(13), 1372–1388. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2018.1530309

- Billingsley, B., McLeskey, J., & Crockett, J. (2019). Success for all students: leading for effective inclusive schools. In J. Crockett, B. Billingsley & M. Boscardin (Eds.), Handbook of Leadership and Administration for Special Education (2nd ed., pp. 306–332). New York: Routledge.

- Boateng, G. O., Neilands, T. B., Frongillo, E. A., Melgar-Quiñonez, H. R., & Young, S. L. (2018). Best practices for developing and validating scales for health, social, and behavioral research: A primer. Frontiers in Public Health, 6(149), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2018.00149

- Brown, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In K. A. Bollen & J. S. Long (Eds.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 136–162). Sage.

- Byrne, B. M. (2016). Adaptation of assessment scales in crossnational research: Issues, guidelines, and caveats. International Perspectives in Psychology, 5(1), 51–65.

- Cattell, R. B. (1966). The scree test for the number of factors. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 1(2), 245–276. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr0102_10

- Causton, J., & Theoharis, G. (2014). The principal’s handbook for leading inclusive schools. Brookes Publishing.

- Causton-Theoharis, J., Theoharis, G., Bull, T., Cosier, M., & Dempf-Aldrich, K. (2011). Schools of promise: A school district —university partnership centered on inclusive school reform. Remedial and Special Education, 32(3), 192–205. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741932510366163

- Costello, A. B., & Osborne, J. (2005). Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 10(1), 7.

- Curran, P. J., West, S. G., & Finch, J. F. (1996). The robustness of test statistics to nonnormality and specification error in confirmatory factor analysis. Psychological Methods, 1(1), 16–29. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.1.1.16

- Day, C., Gu, Q., & Sammons, P. (2016). The impact of leadership on Student outcomes: How successful school leaders use transformational and instructional strategies to make a difference. Educational Administration Quarterly, 52(2), 221–258. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X15616863

- DeMatthews, D. (2015). Making sense of social justice leadership: A case study of a principal’s experiences to create a more inclusive school. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 14(2), 139–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/15700763.2014.997939

- DeMatthews, D. (2020). Undoing systems of exclusion: Exploring inclusive leadership and systems thinking in two inclusive elementary schools. Journal of Educational Administration, 59(1), 5–21. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEA-02-2020-0044

- DeMatthews, D., Billingsley, B., Mcleskey, J., & Sharma, U. (2020). Principal leadership for students with disabilities in effective inclusive schools. Journal of Educational Administration, 58(5), 539–554. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEA-10-2019-0177

- DeMatthews, D. E., Kotok, S., & Serafini, A. (2020). Leadership preparation for special education and inclusive schools: Beliefs and recommendations from successful principals. Journal of Research on Leadership Education, 15(4), 303–329. https://doi.org/10.1177/1942775119838308

- DeMatthews, D. E., Serafini, A., & Watson, T. N. (2020). Leading inclusive schools: Principal perceptions, practices, and challenges to meaningful change. Educational Administration Quarterly, 57(1), 3–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X20913897

- DeMatthews, D. E., Serafini, A., & Watson, T. N. (2021a). Leading inclusive schools: Principal perceptions, practices, and challenges to meaningful change. Educational Administration Quarterly, 57(1), 3–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X20913897

- Florian, L., & Beaton, M. (2018). Inclusive pedagogy in action: Getting it right for every child. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 22(8), 870–884. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2017.1412513

- Gómez-Leal, R., Holzer, A. A., Bradley, C., Fernández-Berrocal, P., & Patti, J. (2022). The relationship between emotional intelligence and leadership in school leaders: A systematic review. Cambridge Journal of Education, 52(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2021.1927987

- Gross, J. M. S., Haines, S. J., Hill, C., Grace, L., Blue-Banning, M., & Turnbull, A. P. (2015). Strong School – community partnerships in inclusive schools are “part of the fabric of the School we count on them. School Community Journal, 25(2), 9–34.

- Hallinger, P., & Wang, W. C. (2015). Assessing instructional leadership with the principal instructional management rating scale. Springer Science Press.

- Hoppey, D., & McLeskey, J. (2013). A case study of principal leadership in an effective inclusive school. The Journal of Special Education, 46(4), 245–256. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022466910390507

- Jelas, Z. M., & Ali, M. M. (2014). Inclusive education in Malaysia: Policy and practice. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 18(10), 991–1003. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2012.693398

- Kassah, B. L. L., Kassah, A. K., & Phillips, D. (2018). Children with intellectual disabilities and special school education in Ghana. International Journal of Disabilities Development Education, 65(3), 341–354. https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912X.2017.1374358

- Kefallinou, A., Symeonidou, S., & Meijer, C. J. W. (2020). Understanding the value of inclusive education and its implementation: A review of the literature. Prospects, 49(3–4), 135–152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11125-020-09500-2

- Khaleel, N. Alhosani, M. & Duyar, I.(2021). The role of school principals in promoting inclusive schools: A teachers’ perspective. Frontiers in Education, 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.603241

- Kline, R. B. (2015). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (2nd ed.).Guilford Press.

- Kozleski, E.(2019). System-wide leadership for culturally responsive education. In J. Crockett, B. Billingsley & M. L. Boscardin (Eds.), Handbook of leadership and administration for special education (pp. 180–195). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Lambrecht, J., Lenkeit, J., Hartmann, A., Ehlert, A., Knigge, M., & Spörer, N. (2022). The effect of school leadership on implementing inclusive education: How transformational and instructional leadership practices affect individualised education planning. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 26(9), 943–957. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2020.1752825

- Leithwood, K., Aitken, R., & Jantzi, D. (2006). Making schools smarter: Leading with evidence. Corwin Press.

- Leithwood, K., Harris, A., & Hopkins, D. (2020). Seven strong claims about successful school leadership revisited. School Leadership & Management, 40(1), 5–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2019.1596077

- Lyons, W. (2016). Principal preservice education for leadership in inclusive schools. The Canadian Journal of Action Research, 17(1), 36–50. https://doi.org/10.33524/cjar.v17i1.242

- MacCallum, R. C., Browne, M. W., & Sugawara, H. M. (1996). Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychological Methods, 1(2), 130–149. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.1.2.130

- Malaysian Education Act 1996. (1998). (Act 550) Part IV, national education system. Chap. 8. International Law Book Services.

- Ministry of Education. (2012). Malaysia education blueprint 2013–2025. Retrieved March 9, 2023, from http://www.moe.gov.my

- Moberg, S., Muta, E., Korenaga, K., Kuorelahti, M., & Savolainen, H. (2020). Struggling for inclusive education in Japan and Finland: Teachers’ attitudes towards inclusive education. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 35(1), 100–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2019.1615800

- Moya, E. C., Molonia, T., & Cara, M. J. C. (2020). Inclusive leadership and education quality: Adaptation and validation of the questionnaire “Inclusive leadership in schools” (LEI-Q) to the Italian context. Sustainability, 12(13), 2–17. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135375

- Muega, M. A. G. (2016). Inclusive education in the Philippines: Through the eyes of teachers, administrators, and parents of children with special needs. Social Science Diliman, 12(1), 5–28.

- Mundfrom, D. J., Shaw, D. G., & Ke, T. L. (2005). Minimum sample size recommendations for conducting factor analyses. International Journal of Testing, 5(2), 159–168. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327574ijt0502_4

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2002). How to use a Monte Carlo study to decide on sample size and determine power. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 9(4), 599–620. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0904_8

- Nag, H., Nærland, T., & Øverland, K. (2021). The importance of school leadership support when working with students with Smith-Magenis syndrome – AQ methodology study. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 70(3), 340–356. https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912X.2021.1888893

- Orphanos, S., & Orr, M. T. (2014). Learning leadership matters: The influence of innovative school leadership preparation on teachers’ experiences and outcomes. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 42(5), 680–700. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143213502187

- Osborne, J. W. (2014). Best practices in exploratory factor analysis. CreateSpace Independent Publishing.

- Óskarsdóttir, E., Donnelly, V., Turner-Cmuchal, M., & Florian, L. (2020). Inclusive school leaders – their role in raising the achievement of all learners. Journal of Educational Administration, 58(5), 521–537. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEA-10-2019-0190

- Pallant, J. (2007). SPSS survival manual. Open University Press.

- Poulos, E., Culberston, N., Piazza, P., & D’Entremont, C. (2014). Making space: The value of teacher collaboration. Rennie Center Education Research & Policy, 80(2), 28–32.

- Ramayah, T., Cheah, J.-H., Chuah, F., Ting, H., & Memon, M. A. (2018). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLSSEM) using SmartPLS 3.0: An updated and practical guide to statistical analysis. Pearson Malaysia.

- Robinson, V. M. J., Lloyd, C. A., & Rowe, K. J. (2008). The impact of leadership on Student outcomes: An analysis of the differential effects of leadership types. Educational Administration Quarterly, 44(5), 635–674. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X08321509

- Robiyansah, I. E., Mudjito, M., & Murtadlo, M. (2020). The development of inclusive education management model: Practical guidelines for learning in inclusive school. Journal of Education and Learning (EduLearn), 14(1), 80–86. https://doi.org/10.11591/edulearn.v14i1.13505

- Rogoff, B. (2003). The cultural nature of human development. Oxford university press.

- Rowe, N., Wilkin, A., & Wilson, R. (2012). Mapping of seminal reports on good teaching (NFER research programme: Developing the education workforce). National Foundation for Educational Research.

- Sakiz, H. (2017). Students with learning disabilities within the context of inclusive education: Issues of identification and school management. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 22(3), 285–305. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2017.1363302

- Saloviita, T. (2020). Attitudes of teachers towards inclusive education in Finland. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 64(2), 270–282. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2018.1541819

- Schermelleh-Engel, K., Moosbrugger, H., & Müller, H. (2003). Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: Tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Methods of Psychological Research Online, 8(2), 23–74.

- Sebastian, J., Allensworth, E., Wiedermann, W., Hochbein, C., & Cunningham, M. (2019). Principal leadership and school performance: An examination of Instructional leadership and organizational management. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 18(4), 591–613. https://doi.org/10.1080/15700763.2018.1513151

- Sharma, M. K., & Jain, S. (2013). Leadership management: Principles, models and theories. Global Journal of Management and Business Studies, 3(3), 309–318.

- Sharma, U., Loreman, T., & Macanawai, S. (2016). Factors contributing to the implementation of inclusive education in Pacific Island countries. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 20(4), 397–412. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2015.1081636

- Swaffield, S., & Major, L. (2019). Inclusive educational leadership to establish a co-operative school cluster trust? Exploring perspectives and making links with leadership for learning. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 23(11), 1149–1163. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2019.1629164

- Tan, K. L., & Adams, D. (2021). Leadership opportunities for students with disabilities in co-curriculum activities: Insights and implications. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education 70(5), 788–802. https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912X.2021.1904504

- Thakkar, J. J. (2020). Structural equation modelling: Application for research and practice. Springer.

- Timothy, S., & Agbenyega, J. S. (2018). Inclusive school leaders’ perceptions on the implementation of individual education plans. International Journal of Whole Schooling, 14(1), 1–30.

- Uljens, M. (2018). Understanding educational leadership and curriculum reform: Beyond global economism and neo- conservative Nationalism. Nordic Journal of Comparative and International Education (NJCIE), 2(2–3), 196–213. https://doi.org/10.7577/njcie.2811

- UNESCO. (1994). The salamanca statement and framework for action on special needs education. UN.

- UNESCO. (2017). Accountability in education: Meeting our commitments. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000259338

- UNESCO. (2020). Towards inclusion in education: Status, trends and challenges: The UNESCO salamanca statement 25 years on.

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.

- Waldron, N. L., McLeskey, J., & Redd, L. (2011). Setting the direction: The role of the principal in developing an effective, inclusive school. Journal of Special Education Leadership, 24(2), 51–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/019263655904325117

- Wheaton, B., Muthen, B., Alwin, D. F., & Summers, G. F. (1977). Assessing reliability and stability in panel models. Sociological Methodology, 8, 84–136. https://doi.org/10.2307/270754