ABSTRACT

Students with severe intellectual disabilities or profound and multiple learning difficulties (S/PMLD) have the highest complexity of needs of any student cohort. Decisions regarding curriculum inclusions for these students predominantly fall to their classroom teachers. These decisions directly correlate with students’ everyday learning experiences and have an influence on their life-long socio-economic, health, and well-being outcomes. This scoping review presents an overview of the factors that teachers consider when making these important choices. Online databases were used to identify peer-reviewed research undertaken internationally between 2011 and 2021 with 11 articles identified for inclusion. Results are presented using four key themes, (1) teacher as guardian, (2) teacher as educator, (3) teacher as employee and (4) teacher as (non)academic. Within, it details a paucity of research into understanding the decision-making schema of teachers of students with S/PMLD, revealing a lack of practical guidance or appropriate professional learning opportunities. Recommendations for future research and practice initiatives are detailed.

Teaching as a profession is characterised by a constant process of decision-making. Teachers are responsible for making decisions central to the learning, social and personal experiences of their students. Teachers are frequently relied on to make reliable and independent choices such as implementing complex adjustments, study patterns, and day-to-day experiences, influenced by their thoughts and judgement (Eggleston, Citation2019; Ruppar et al., Citation2015). The quality of these choices directly influences student engagement, learning outcomes, and life milestones. The interaction between a teacher’s action and cognitive influences is central to understanding the teaching process and supporting and improving professional experiences and student outcomes (Borko & Shavelson, Citation2013).

Students with severe intellectual disabilities or profound and multiple learning difficulties (S/PMLD) have the highest complexity of needs within the student body. There is a shared understanding that students who are S/PMLD will have all or some of the following characteristics: severe learning difficulties, sensory impairments, physical disabilities, unconventional communication profiles, challenging behaviours and complex medical conditions (Colley & Tilbury, Citation2021; Nind & Strnadova, Citation2020). It is recognised that these students will need high levels of adult support throughout their educational experience and will most likely be enrolled in a specialist educational setting (Colley & Tilbury, Citation2021). Curriculum experiences for these learners are centralised around the pillars of communication, sensory, personal care, physical and wellbeing development, with a clear motivation to develop independent skills and experiences of happiness for students (Colley & Tilbury, Citation2021; Lawson et al., Citation2015; Nind & Strnadova, Citation2020).

C. Jones (Citation2019) states there is a paucity of research into teachers’ experiences who support these students and that the teachers of pupils with S/PMLD can experience more emotional pressures in their work. As well as the highly dynamic emotionality of their role, the work of Male (Citation2015) and Carpenter (Citation2007) show that there is a professional expectation that these teachers must have a highly individualised and specialist knowledge of their pupils, paired with the responsibility to develop individualised curriculum programs for each of their students and a constantly reflexive consideration of their pedagogy. The role of teaching students with S/PMLD is highly complex and examining the emotional and cognitive influences of how teachers make choices about curriculum is crucial, revealing insights into the way teachers conceptualise the nature of learning and its relationship to students with S/PMLD (Colley, Citation2018; Lawson & Jones, Citation2018)

Due to the complexities associated with supporting students with S/PMLD, the impact of decisions is not limited to day-to-day experiences within the classroom, or even their educational experience more generally, but can have far-reaching implications for whole of life outcomes, the formation and sustained connections to their community and social-emotional development and wellbeing (Colley, Citation2018). Gaining insight into the personal and professional decision-making practices adopted by teachers in the education of these students allows for an exploration into not only how these teachers make choices but what motivations underly their choice-making (Vanlommel et al., Citation2017). By increasing our understanding of how decisions are influenced by these pressures and how teachers deal with the challenges they face is critical in the progress towards the inclusion of students with S/PMLD, as well as the provision of a safe and supportive professional context (C. Jones, Citation2019; Ruppar et al., Citation2015).

Rationale

Explorative searches on the intended topic were conducted, it was clear to the research team that a structured search technique and analysis methodology would be required. These initial searches yielded minimally relevant information and a high level of variation depending on the different search terms utilised. It was clear that a more methodical approach would be required. A scoping review methodology was identified for its capacity to map quickly and easily multiple and varied thematic responses to a research question. The research intention was to gain a broad scope of the current knowledge base of the topic, a systematic review, which is more precise in its focus, was not seen as appropriate (Munn et al., Citation2018). Due to the intended sample population’s small size in relationship to the extensive work completed in decision-making for teachers more broadly, a structured research approach was necessary to quickly identify and extract relevant articles.

A scoping review methodology facilitates a rigorous and specific structure for evidence identification and synthesis and are a standard method for researchers to quickly and coherently present an evidence base to inform decision-making (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005; Munn et al., Citation2018). Scoping reviews allow for an iterative analysis process, identify academic knowledge gaps, and rapidly map critical concepts within a research area while maintaining academic rigour and coherence (Anderson et al., Citation2020; Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005; Peters et al., Citation2015). A scoping review enabled the authors to present a specific evidence-based response to the question; What role do teachers adopt when making curriculum-related decisions for students with severe intellectual disabilities or profound and multiple learning difficulties?

Objectives

A scoping review was conducted to systematically identify and analyse the research undertaken into the various roles teachers inhabit within the curriculum design process for students with S/PMLD. The primary objective of this review was to present a comprehensive foundation for future research initiatives and promote investigation into this area of knowledge (Munn et al., Citation2018).

The research question was created using the Sample, Phenomenon of Interest (this includes behaviours, experiences, and interventions), Design, Evaluation, Research type (SPIDER) research question formulation tool (Cooke et al., Citation2012). The SPIDER tool was developed as an alternative to the more frequently used Population/Problem, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome (PICO) research question formulation approach. SPIDER was designed to capture qualitative and mixed methods research more reliably within search protocols and remove more irrelevant aspects of the PICO tool, such as Comparison, which is only related to quantitative methodologies. The Intervention and Outcome of PICO also need significant manipulation when aligning with a qualitative or mixed method paradigm (Cooke et al., Citation2012). Due to the intent of the scoping review, which sought to identify teacher perspectives, points of view and reflections on the decision-making process, the SPIDER tool was more aligned to the requirements of the study.

Method

The protocol for this scoping review was drafted using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) (Tricco et al., Citation2018). The PRISMA-ScR is a checklist containing 22 items (two of which are optional) included in any scoping review. The PRISMA-ScR was developed to provide researchers and academics, through to end-users, clarity about the structure and form scoping reviews take and promote shared acceptance of key terminologies, concepts, and items for inclusion within this methodological approach (Tricco et al., Citation2018).

Papers included in this review met the following criteria as needing to be peer-reviewed, published between 2011 and 2021 and written in English. Each article’s Phenomenon of Interest was required to be clearly articulated as investigating the curriculum decision-making of teachers and specifically in educational settings. To be eligible for inclusion in this review, journal articles also needed a sample participant base of teachers of students with S/PMLD. Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed method studies/publications were included. This decision aligns with Peters et al. (Citation2015), who state that articles, regardless of their quality, inform the existing evidence base, and searches should not limit evidence collection based on evidence quality or research methodology.

Papers were excluded if they did not meet the sample participant base, or if the results associated with the participant base could not be identified within the study results. Common trends within the participant base of excluded papers included allied health professionals, parents, pre-service teachers, or teaching assistants. In addition, an exclusion parameter for the profiling of singular teacher/student relationships was used. The researchers posit that articles profiling a singular teacher/student relationship could focus on one relationship’s interpersonal features and emotional factors instead of decision-making practices that a teacher would use more generally. Papers were excluded where the diagnosis of the student body was not specified. For example, if the paper used the terminology students with a disability rather than students with S/PMLD. The use of terminology such as students with a disability was too broad and did not allow the requisite student cohort to be identified. Using strict terminology guidelines ensured that specific evidence in response to the research question was captured (Cooke et al., Citation2012).

Search Strategy

When identifying articles for inclusion, the following journal databases were searched on the advice of a research librarian: EBSCO, ProQuest, JSTOR, Sage, Emerald, and Informit. The first author drafted the search strategy and consulted with the two other authors who supported the approach in line with the SPIDER protocol. The search was last undertaken in October 2021. The final search results were exported; duplicates were removed before more systematic eligibility assessments were undertaken according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria as outlined.

The SPIDER research question tool allows for a systematic and repeatable search strategy to be utilised (Cooke et al., Citation2012). details the search terms and formulation of the search strategy based on the SPIDER tool. The first author executed the initial search and consequent exclusion eligibility assessments. The first author completed an initial evaluation of the title and abstract information to collate the final list and then completed a final full-text read-through of the remaining articles.

Table 1. Search strategy using the SPIDER tool.

Selection of Sources of Evidence

The initial database and manual searches identified 162 articles. Ninety-four articles were excluded as they did not meet the inclusion criteria. The remaining titles and abstracts of the 68 articles were then assessed against the exclusion criteria. At this stage, 36 articles were removed. Eight duplicates were removed, reducing the number of included articles to 24 for a full text read through. Eleven articles were removed during this stage of the process, primarily due to their lack of specificity to curriculum development. Thirteen articles were identified for final inclusion. However, two articles were excluded during analysis due to the inability to extract findings directly related to teaching students with S/PMLD. This final exclusion resulted in 11 articles retained for inclusion within this scoping review. The selection process was primarily managed by the first author, but at each stage of exclusion the second and third authors were consulted; being sent copies of each article marked for removal and given full explanatory notes on why the article was not appropriate for inclusion and time to review each decision. Full agreeance at each stage of exclusion was met in the first instance. reports literature search results, including the number of articles removed and reasons for excluding full-text articles at each stage.

Data Extraction

Specific data items on article characteristics were extracted (year of publication, country of origin) and methodological features (methodological design, sample population and number/scope of participants). This process was undertaken to develop a more comprehensive understanding of the evidence base before a reflexive thematic analysis of findings was undertaken. A reflexive thematic analysis was chosen as it is a flexible method that captures a rich and detailed picture of qualitative data and its capacity to effectively address research questions that investigate the behaviours and motivations of individuals and explore factors that underpin decisions; central intentions of the research question (Braun & Clarke, Citation2012; Braun et al., Citation2019). The thematic analysis followed the six stages described by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006), familiarising with the data, generating initial codes, searching for themes, reviewing themes, defining, and naming themes. The article characteristics, geographic, methodological, and thematic information of each article is shown in .

Table 2. Included article features.

A critical appraisal of the sources of evidence was not undertaken. The PRISMA-ScR suggests this as an optional feature of a scoping review. A quality appraisal was unnecessary to maintain responses relevant to the research question, as the intention was to map the current knowledge in this area and clarify the conceptual responses, as opposed to analysing the research type and quality of the field (Munn et al., Citation2018).

To identify common themes across all the retained articles, the first author undertook a process of reflexive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). Reflexive thematic analysis is an inductive process and allows for patterns across data sources to be identified and then transitioned into a theoretical presentation of core concepts, allowing for a more abstracted and interpretive commentary to be articulated (Braun & Clarke, Citation2020; Graneheim et al., Citation2017).

Results

This scoping review identified 11 peer-reviewed articles over the last 10 years that informed a response to the research question (see ). The characteristics of each of these sources are articulated in .

The first author developed key themes after patterns across the articles were explored and discussed between the first and second authors. Although reflexive thematic analysis does not require a coding reliability process; it was decided to be important due to the first author having never undertaken this process previously, and to encourage more thoughtful analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2019). The first and second authors discussed the final thematic interpretation and jointly discussed three of the eleven included articles. In this collaborative process, they identified a lack of clarity in aspects of the coding, Power and How would you know? The authors deeply discussed possible reasons for their individual divergence in interpretation. It was decided that the original intention of each of these codes lacked clarity, leading the first two authors to collaboratively explore their meaning and intention, ensuring that they were reflecting the intended content across sources (Braun & Clarke, Citation2013, Citation2020).

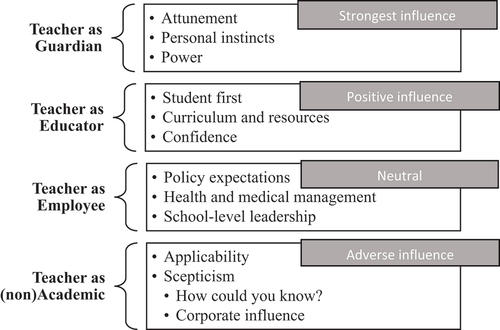

Finally, four themes were developed and agreed upon that capture teachers’ multiple professional identities throughout the curriculum planning and implementation process. The themes were (1) teacher as guardian, (2) teacher as educator, (3) teacher as employee and (4) teacher as (non)academic. A visual representation of these themes and sub-themes within each is presented in . The themes and secondary codes presented within each included article are articulated in .

In line with the PRISMA-ScR protocol, the results of this review will be structured as a discussion, in which a summary of results aligned to each theme will be presented, and then an extended conclusions section, where an analysis of the results and implications for future research will be discussed (Tricco et al., Citation2018).

Discussion

Summary of Evidence

This scoping review had the objective of investigating the research question; What role do teachers adopt when making curriculum-related decisions for students with severe intellectual disabilities or profound and multiple learning difficulties?

Four key themes described teachers’ roles and the possible influencing factors that shape these roles were identified. However, the findings indicate a paucity of research focusing specifically on this field of knowledge. This dearth of recent investigations is reflected in the small number of articles included in this review.

Eight of the eleven included articles directly call on more research into decision-making practices and influences on teachers of students with S/PMLD. For example, Bon and Bigbee (Citation2011) link this to an ethical decision-making approach, stating, ‘we discovered inadequate information about the influence and interaction of ethical codes on the decisions made by special education leaders when faced with ethical dilemmas’ (p. 332). This issue is reinforced in more contemporary work, with Knight, Huber, Kuntz, Cater and Juarez (Citation2019), Timberlake (Citation2016) and Ruppar et al. (Citation2015) all concluding that researchers should attempt to identify what motivates teachers of students with S/PMLD and how they prioritise specific academic content areas. Moreover, researchers should clarify the specific contextual influences on teachers’ decisions when planning curricula for students with S/PMLD (Timberlake, Citation2016).

Across the four key themes, each theme had an identifiable level of influence over teachers’ decision-making. This level of influence is indicated in .

An example of an adverse influence is expressed by teachers directly steering away from specific types of information or not valuing the contribution certain sources of information could make to their decision-making, even leading to rejecting the contribution it could make. This type of influence is predominantly throughout the teacher as (non)academic theme. Spanning across seven of the included articles, this direct aversion to engaging in the evidence base is expressed as a perceived lack of relevance in research agendas, non-specific professional learning, and promoting ill-fitting evidence-based practices for the student body. This aversion away from the research evidence base was directly cited extensively, but also reinforced by continual preferencing towards personal instincts and emotional attunement, as seen in the teacher as guardian theme (Bon & Bigbee, Citation2011; Feiler & Watson, Citation2011; Greenway et al., Citation2013; Hopkins & Dymond, Citation2020, Knight et al., Citation2019; Lawson & Jones, Citation2018; Shipton & O’Nions, Citation2019).

Teacher as Guardian

Teachers draw from personal histories, instincts, and personal ethical codes to make the perceived ‘right’ choices for their students. The teacher as guardian theme is grounded in relational experiences, personal history (both professional and personal), and emotional understandings. Teacher as guardian was the most widely and positively discussed thematic trend across all articles. Discussions regarding the importance of emotional attunement and relational reciprocity between teacher and student were present. Bon and Bigbee (Citation2011) report that ‘gut’ feelings tend to underly participant decisions, with this, often being at odds with policy or lawful requirements of the role “ … do I do what they tell me to do, or do I do ‘what’s best for the child?” (p. 341).

All 11 articles reported that a teacher’s personal instincts informed decisions; their personal history, experiences and expectations and belief structures fed into most decision-making considerations. The ‘right’ thing was often based on an intuitive understanding and made by the teacher based on their perceived emotional connection or awareness of the student (Bon & Bigbee, Citation2011; Feiler & Watson, Citation2011; Lawson & Jones, Citation2018; Quinn & Serna, Citation2019; Shipton & O’Nions, Citation2019). Timberlake (Citation2016) articulated a trend among participants to consistently use the phrase ‘I’m able to do what I think is best … I decide what the best possible world is for the kids’ (p. 203).

The complexity of integrating a personal code of ethics while still maintaining a student-focussed decision-making pathway that upholds lawful obligations led to significant levels of inner conflict in participants. Trying to manage this paradigm was raised by some study participants as a primary contributor to decisions that made curriculum pathways sit in conflict with inclusive educational experiences (Bon & Bigbee, Citation2011; Ruppar et al., Citation2011). Ruppar et al. (Citation2015) explored a teacher’s intuitions and the effect on future student outcomes, articulating that ‘A link, therefore, was seen between teachers’ experiences and their expectations for students, which led to more restrictive or more expansive goals for the students’ (p.218). In recognising the level of influence, their choices have over student outcomes, as Shipton and O’Nions (Citation2019) and Timberlake (Citation2016) reported, teachers responded to the responsibility and power they had over their students well beyond the daily experiences of the classroom. However, teachers were not insensitive to this power, expressing a sense of caution when trying to make decisions “ … [I have an] awareness of the enormity of teacher responsibility for students’ lives, and acknowledgement that there may be different ‘right’ answers” (Timberlake, Citation2016, p. 203).

Teacher as Educator

A teacher’s confidence and self-efficacy in using their professional skills to meet student needs are critical to their choices, professionalism, and perception of their students’ abilities (Ruppar et al., Citation2015).

There are two primary interactive trends within the Teacher as educator theme that most often take a steering role in the decision-making process for teachers, student-first planning, and feelings of professional confidence. Student-first planning is articulated as the centre of all decision-making in all 11 of the included articles. Most of the time, this is despite the structural or system requirements, as captured by Lawson and Jones (Citation2018) with their analysis that ‘Generally, students were privileged at the expense of curriculum, and importance placed on a responsive interactional relationship between teacher and student’ (p. 204). The motivation to anchor decisions in this student-first context highlighted tensions that teachers have when navigating between students and curriculum.

If they want to base things on appropriate evidence-based practice and provide curriculum that way, there needs to be enough out there so we can select what’s good and I don’t really think there is … there is hardly anything out there, um I really feel like we are pioneers’ … classroom decisions were based on what they came up with or created on their own.

The weight of responsibility for making curriculum choices without the support of the structural elements of the system is tangible and has created a context of professional singularity. Timberlake (Citation2016) states that the context of aloneness is developed by the experienced social and professional isolation special education teachers have from their peers and the significant individual discretionary power and autonomy in all decision-making processes. Feelings of professional and personal self-efficacy in relation to a teacher’s experiences of aloneness relate to their capacity to make, trust, and implement their choices with confidence (Bon & Bigbee, Citation2011; Greenway et al., Citation2013; Lawson & Jones, Citation2018; Quinn & Serna, Citation2019; Ruppar et al., Citation2015; Shipton & O’Nions, Citation2019; Timberlake, Citation2016).

Greenway et al. (Citation2013) and Shipton and O’Nions (Citation2019) report this phenomenon in detail, revealing that teachers often feel isolated from peers, operate under a lack of accountability, and perceive that leadership cannot, or does not need to support them. This phenomenon of isolation is explored in detail by Timberlake (Citation2016), who presents a conceptual decision-making model that is not just informed but defined, by aloneness. Some teachers dually noted that this context allowed for more autonomy and cultivated feelings of capacity and positive self-efficacy. Others reported that aloneness undermined their confidence and created an environment where teachers questioned their skills and were untrusting of their own decisions (Shipton & O’Nions, Citation2019; Timberlake, Citation2016).

The ubiquity of aloneness has led some teachers positively welcoming this decision-making context and adopting a complete responsibility model for all decisions for their students and resultant outcomes (Ruppar et al., Citation2015). Some teachers interpreted this isolation as an accepted norm of their role and perceived it as recognising high performance, professional credibility, and an expression of trust from leadership (Greenway et al., Citation2013; Shipton & O’Nions, Citation2019; Timberlake, Citation2016).

Teacher as Employee

The interaction and influence of the system structures, professional learning, and school-level support that feed into teachers’ decision-making.

In the Teacher as employee theme, teachers acknowledge their legal and professional requirements to policy or school level accountability processes. Bon and Bigbee (Citation2011) suggested that policy compliance issues, such as standardised curriculum access, frequently featured in the considerations of participants. Teachers commonly referenced professional obligations or requirements but expressed a tendency to navigate around them or ignore them in preference for other elements that they think will work when making decisions for individual students (Greenway et al., Citation2013; Knight et al., Citation2019).

Hopkins and Dymond (Citation2020), Lawson and C. Jones (Citation2019) and Ruppar et al. (Citation2015) all cite that when facing generalised curriculum and pedagogical choices, it is policy, administrative requirements, and status-quo set by other teaching peers that take precedence and most influence enacted decisions. The dual-policy requirements of standardisation and individualisation are a central tension in teachers’ decision-making (Timberlake, Citation2016). However, the levels of accountability and oversight in implementing these requirements were inconsistent and a source of high anxiety (Bon & Bigbee, Citation2011). This context led to lower levels of support in accessing resources, diminished collegiate and leadership support and, as concluded by Greenway et al. (Citation2013), lead to positioning these teachers on the fringes of ‘mainstream’ school and district culture (Bon & Bigbee, Citation2011; Ruppar et al., Citation2011).

Teacher as employee also describes the changing role and requisite skills for students with S/PMLD, including the necessity to respond and manage their students’ health and medical requirements and teachers expressing a low level of confidence when making informed decisions in this area (Lawson & Jones, Citation2018; Quinn & Serna, Citation2019; Shipton & O’Nions, Citation2019). In addition, access to appropriate professional learning to support confident and informed decision-making more generally was sighted (Bon & Bigbee, Citation2011; Feiler & Watson, Citation2011; Greenway et al., Citation2013; Ruppar et al., Citation2015). There is no one decision-making model for teaching professionals, and decision-making is not a part of most initial teacher education programs or professional learning priorities (Bon & Bigbee, Citation2011). With decisions being made void of specific decision-making structures or ethical choice-making frameworks, teachers are left to self-conceptualise, further reinforcing the context of aloneness and low levels of confidence and professional efficacy (Greenway et al., Citation2013; Ruppar et al., Citation2015; Timberlake, Citation2016).

Teacher as (Non)Academic

Research and evidence-based practices (EBP) are not reported as positively influencing factors within the decision-making process for teachers of students with S/PMLD. Teachers tended to believe that the traditional evidence base is not usually developed or trialled by students with S/PMLD (Greenway et al., Citation2013). Knight et al. (Citation2019) report that their data found that ‘recommendations from researchers who work/have worked at my school’ was the second most negligible influencing factor in teachers’ decisions regarding their in-class practice. Although there are elevated levels of apprehension regarding EBP for their students, teachers recognise the critical role EBPs could play in developing meaningful curriculums if they saw them as relevant (Feiler & Watson, Citation2011; Greenway et al., Citation2013).

Due to these levels of apprehension, teachers would consistently revert to the teacher as guardian mindset; with a participant from the Greenway et al. (Citation2013) study stating, ‘ … I don’t think there have been any studies done on our classrooms … like we know more than what the researchers know about how to run a classroom like this’ (p. 464). It is important to note that personal instincts are highly relevant within the teacher as guardian mindset. Someone’s instincts are developed by their evidence from prior experiences and draw from both a professional and personal evidence base, including theoretical knowledge sources. Teachers express general scepticism or distrust of research, even seeing some evidence-based practices as money-making endeavours (Greenway et al., Citation2013).

Limitations

This study had a specific focus on students with S/PMLD as a parameter for included articles. Broadening this focus to special education or students with disabilities may mean relevant information related to this investigation from the broader field of research was omitted. The choice to be refined in focus was motivated by the paucity of research available and the personal and systematic complexities that hold power in the decision-making process for teachers in this field. The research results presented in a significant proportion of the articles are either based on small sample sizes of participants, or very jurisdictionally specific locations by a singular state or school community, or both. Although general trends can be mapped across the findings, it is important to recognise these sampling features as a clear limitation in directly interpreting these findings to be applicable in every context or different jurisdictional area, or assume that the experiences of individual or school communities of teachers directly reflect these more generalised trends. This limitation was as a result of the process, and at no stage did the research team use geographic information as an inclusion/exclusion criterion. In addition, this study did not include grey literature, which may have offered a broader scope of relevant information. The inclusion of grey literature would have only reinforced highly jurisdictionally and geographically bound characteristics, as it is closely tied to the policies, priorities and cultures of specific school systems or jurisdictional mandates. The authors would recommend that if contextually specific research were to take place, and then the relevant grey literature should be referenced.

Conclusions

Two best-practice features of curriculum planning discussed across literature and policy into practice guidance are an age-appropriate response to curriculum design and the involvement of parents/home as equal partners in the designing curriculum (Colley, Citation2018; Lyons & Arthur-Kelly, Citation2014; Moljord, Citation2018). These features of decision-making best practice were not revealed during analysis, further indicating a lack of coherence between research and policy and the reality of practice. Although the search criteria and question were not designed to specifically examine these elements, the lack of reference in any of the included articles is concerning and should be explored further.

Age-appropriateness and parent/home relationships are consistently raised as central pillars of teacher planning when creating and maintaining socially inclusive and meaningful educational experiences for students with disabilities, particularly students with S/PMLD. Neither parent/home engagement nor age-appropriate considerations were identified as prioritised influences within the retained articles. Although links could be made between age-appropriateness to the Teacher as educator theme, this link is tentative at best through the need to use the standardised curriculum. Inherent to age-appropriateness is also the dedication to offering experiences and pop-cultural engagement as reflected in the identities of same-age peers.

This concern also extends to the lack of discussion regarding parent/home and teacher relationships. Collaboration between these two parties is essential in developing meaningful curriculum pathways that respond to student capacities and lifelong learning and skills needs (Ayres et al., Citation2011; Bobzien, Citation2014; Colley, Citation2018).

Knight et al. (Citation2019), Timberlake (Citation2016), and Ruppar et al. (Citation2015) conclude that there is a significant gap in research examining the cognitive and emotional influences on teachers when they make curriculum decisions for students with S/PMLD. The authors recommend further investigations into what motivates educators, why they prioritise specific academic content areas/skills and experiences, and how this is then operationalised. Undertaking this recommendation is fundamental in increasing the quality of support teacher experience at the school and systems level. Furthermore, findings could inform the development of appropriate and standardised decision-making models, targeted professional learning programs, and develop clarity of process when navigating a complex curriculum context that upholds a more inclusive and supportive system for teachers and students alike. Brezicha (Citation2019) found that when offered a way to undertake structured decision-making, teachers feel a higher sense of ownership and control, leading to positive feelings and higher levels of job satisfaction and improved personal psychology. The pressures caused by a teacher’s emotionally charged and isolated professional position can be positively responded to when considering Brezicha’s (Citation2019) findings.

In identifying the type of influence each of the four key themes had over decision-making, the authors do not wish to allude to the quality, success or failure of a teacher’s decisions or practice choices. The authors do not intend or wish to communicate a level of judgement and do not make qualitative assessments on the positive or negative flow-on effect of these levels or types of influence. Instead, it helps contextualise how and why teachers make decisions and identifies gaps in knowledge and research to practice translations. In no way do the research team wish to allude to the discussions within the Teacher as (non)academic theme as a negative commentary on teacher practice. Teachers prioritising intuition over data-driven sources is a trend seen across all teaching contexts (Vanlommel et al., Citation2017). Vanlommel et al. (Citation2017) stress the importance of research investigating the formation and development of intuition if teacher decision-making is better understood and high-quality professional support and learning is to be developed.

The authors feel the negligible influence of the evidence base is primarily due to the reliance teachers have on their intuition and significant research into practice gaps. This uneven balance between intuition and evidence-based decisions articulates a deficit in how researchers communicate with this population of teachers when sharing their findings and raises a concern regarding how effectively researchers translate their findings into a practice framework. Considering this interaction, it also reveals a gap between education authorities’ increasing demand for data and evidence to justify decisions and everyday decision-making practices. Evidence-based practices need to be integrated into appropriate professional learning, complemented with a decision-making model that is sensitive to this intuitive process. Doing this allows evidence and data to be established as critical in teaching and learning context in a practical sense, leading to more positive student outcomes and reducing personal biases (Vanlommel et al., Citation2017).

The revelations by Timberlake (Citation2016) regarding teacher’s feelings of aloneness and isolation are not new. Work undertaken by P. Jones (Citation2004) profiled the interactions between teacher identity and the perception that they are separate and different from their mainstream colleagues. The tension between a teacher’s identity as a ‘special educator’ and their identity as a ‘teacher’ more generally needs to be examined further if an inclusive culture within education systems is cultivated (Jones, Citation2004). The lack of progress between the P. Jones (Citation2004) study and Timberlake (Citation2016) reflects a lack of change in cultural and systemic dimensions to the profession. The multi-jurisdictional context of these studies indicates that this is a phenomenon not limited to a single jurisdiction. The influence of isolation on teachers’ professional identities of students with S/PMLD and the effect on the cultivation of collegiate support networks and learning communities need to be examined. How teachers experience isolation and the potential impact on their decision-making processes and thinking around professional learning and support regarding relevancy and usability is an area for future investigation. Professional learning opportunities and the development of a profession-specific decision-making model are needed to support teachers in navigating the dual-policy obligations of individualisation and standardisation and making decisions that support a balance between the need for student-led flexibility and their professional obligations. Although a defining feature in most Western countries, the tension between individualisation needs and standardised system pressures is highly variable in its characteristics due to specific jurisdictions’ policy settings. The authors advocate that research particularly needs to focus on localised investigations and extend beyond the primary research sites, as included in the articles herein, which exclusively include the United States and the United Kingdom.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Anderson, J. K., Howarth, E., Vainre, M., Humphrey, A., Jones, P. B., & Ford, T. J. (2020). Advancing methodology for scoping reviews: Recommendations arising from a scoping literature review (SLR) to inform transformation of children and adolescent mental health services. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 20(242). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-020-01127-3

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Ayres, K. M., Lowrey, K. A., Douglas, K. H., & Sievers, C. (2011). I can identify Saturn, but I ‘can’t brush my teeth: What happens when the curricular focus for students with severe disabilities shifts. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 46(1), 11–21. https://www.jstor.org/journal/eductraiautideve

- Bobzien, J. L. (2014). Academic or functional life skills? Using behaviours associated with happiness to guide instruction for students with profound/multiple disabilities. Education Research International, 2014, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/710816

- Bon, S., & Bigbee, A. (2011). Special education leadership: Integrating professional and personal codes of ethics to serve the best interests of the child. Journal of School Leadership, 21(3), 324–359. https://doi.org/10.1177/105268461102100302

- Borko, H., & Shavelson, R. J. (2013). Teacher decision making. In B. F. Jones & L. Idol (Eds.), Dimensions of thinking and cognitive instruction (pp. 311–341). Routledge. https://www.routledge.com/

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2012). Thematic analysis. In H. Cooper, P. M. Camic, D. L. Long, A. T. Panter, D. Rindskopf & K. J. Sher (Eds.), APA Handbook of research methods in psychology, research designs (Vol. 2, pp. 57–71). American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. Sage Publications. https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/home

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise & Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2020). One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qualitative Research in Psychology, 18(3), 328–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238

- Braun, V., Clarke, V., Hayfield, N., & Terry, G. (2019). Answers to frequently asked questions about thematic analysis. https://cdn.auckland.ac.nz/assets/psych/about/our-research/documents/Answers%20to%20frequently%20asked%20questions%20about%20thematic%20analysis%20April%202019.pdf

- Brezicha, K. F., & Fuller, E. J. (2019). Building teachers’ trust in principals: Exploring the effects of the match between Teacher and Principal Race/Ethnicity and gender and feelings of trust. Journal of School Leadership, 29(1), 25–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/1052684618825087

- Carpenter, B. (2007). Changing children– Changing schools? Concerns for the future of teacher training in special education. PMLD–Link, 19(2), 2–4. https://www.pmldlink.org.uk/

- Colley, A. (2018). To what extent have learners with severe, profound and multiple learning difficulties been excluded from the policy and practice of inclusive education? International Journal of Inclusive Education, 24(7), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2018.1483437

- Colley, A., & Tilbury, J. (2021). Enhancing wellbeing and independence for young people with profound and multiple learning difficulties: Lives lived well. Routledge. https://www.routledge.com/

- Cooke, A., Smith, D., & Booth, A. (2012). Beyond PICO: The SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qualitative Health Research, 22(10), 1435–1443. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732312452938

- Eggleston, J. (Ed.). (2019). Teacher decision-making in the classroom: A collection of papers. Routledge & K. Paul. (Original work published in 1979) https://www.routledge.com/

- Feiler, A., & Watson, D. (2011). Involving children with learning and communication difficulties: The perspectives of teachers, speech and language therapists and teaching assistants. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 39(2), 113–120. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3156.2010.00626

- Graneheim, U. H., Lindgren, B., & Lundman, B. (2017). Methodological challenges in qualitative content analysis: A discussion paper. Nurse Education Today, 56, 29–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2017.06.002

- Greenway, R., McCollow, M., Hudson, R., Peck, C., & Davis, C. (2013). Autonomy and accountability: Teacher perspectives on evidence-based practice and decision-making for students with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 48, 456–468. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24232503

- Hopkins, S., & Dymond, S. K. (2020). Factors influencing teachers’ decisions about their use of community-based instruction. Intellectual Developmental Disabilities, 58(5), 432–446. https://doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556-58.5.432

- Jones, C. (2019). “All the small things”: Research exploring the positive experiences of teachers working with pupils with profound and multiple learning difficulties [ DEdPsy Thesis]. Cardiff University. http://orca.cardiff.ac.uk/id/eprint/127612

- Jones, P. (2004). They are not like us and neither should they be’: Issues of teacher identity for teachers of pupils with profound and multiple learning difficulties. Disability & Society, 19(2), 159 169. https://doi.org/10.1080/0968759042000181785

- Knight, V. F., Huber, H. B., Kuntz, E. M., Carter, E. W., & Juarez, A. P. (2019). Instructional practices, priorities, and preparedness for educating students with autism and intellectual disability. Focus on Autism & Other Developmental Disabilities, 34(1), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088357618755694

- Knight, V., Huber, H., Kuntz, E., Carter, E., & Juarez, A. (2018). Instructional practices, priorities, and preparedness for educating students with autism and intellectual disability. Focus on Autism & Other Developmental Disabilities, 34(1), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088357618755694

- Lawson, H., Byers, R., Rayner, M., Aird, R., & Pease, L. (2015). Curriculum models, issues and tensions. In P. Lacey, R. Ashdown, P. Jones, H. Lawson & M. Pipe (Eds.), The Routledge companion to severe, profound and multiple learning difficulties (pp. 233–245). Routledge. https://www.routledge.com/.

- Lawson, H., & Jones, P. (2018). Teachers’ pedagogical decision-making and influences on this when teaching students with severe intellectual disabilities. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 18(3), 196–210. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-3802.12405

- Lyons, G., & Arthur-Kelly, M. (2014). UNESCO inclusion policy and the education of school students with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities: Where to now? Creative Education, 5(7), 445–456. https://doi.org/10.4236/ce.2014.57054

- Male, D. (2015). Learners with SLD and PMLD: Provision, policy and practice. In P. Lacey, R. Ashdown, P. Jones, H. Lawson & M. Pipe (Eds.), The Routledge companion to severe, profound and multiple learning difficulties (pp. 9–18). Routledge. https://www.routledge.com/.

- Moljord, G. (2018). Curriculum research for students with intellectual disabilities: A content analytic review. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 33(5), 646–659. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2017.1408222

- Munn, Z., Peters, M. D. J., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(143). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

- Nind, M., & Strnadova, I. (2020). Changes in the lives of people with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities. In M. Nind & I. Strnadova (Eds.), Belonging for people with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities (pp. 1–21). Routledge. https://www.routledge.com/.

- Peters, M. D., Godfrey, C. M., Khalil, H., McInerney, P., Parker, D., & Soares, C. B. (2015). Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare, 13(3), 141–146. https://doi.org/10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050

- Quinn, B. L., & Serna, R. W. (2019). Educators’ experiences identifying pain among students in special education settings. The Journal of School Nursing, 35(3), 210–220. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059840517747974

- Quinn, B., & Serna, R. W. (2017). Challenges and barriers to identifying pain in the special education classroom: A review. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 4, 328–338. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-017-0117-1

- Ruppar, A. L., Dymond, S. K., & Gaffney, J. S. (2011). Teachers’ perspectives on literacy instruction for students with severe disabilities who use augmentative communication. Research & Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 36(3), 100–111. https://doi.org/10.2511/027494811800824435

- Ruppar, A. L., Gaffney, J. S., & Dymond, S. K. (2015). Influences on teachers’ decisions about literacy for secondary students with severe disabilities. Exceptional children, 81(2), 209–226. https://doi.org/10.1177/0014402914551739

- Shipton, C., & O’Nions, C. (2019). An exploration of the attitudes that surround and embody those working with children and young people with PMLD. Support for Learning, 34(3), 277–289. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9604.12265

- Timberlake, M. T. (2016). The path to academic access for students with significant cognitive disabilities. The Journal of Special Education, 49(4), 199–208. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022466914554296

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

- Vanlommel, K., Van Gasse, R., Vanhoof, J., & Van Petegem, P. (2017). Teachers’ decision-making: Data based or intuition driven? International Journal of Educational Research, 83, 75–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2017.02.013