ABSTRACT

The aim of this article is to analyze the reactions of some mainstream Israeli politicians to a celebrity marriage between Tzahi Halevi, a Jewish Israeli actor, and Lucy Aharish, a Palestinian Israeli TV personality. Drawing upon the notion of stance, we unveil the affective trouble generated by this heterosexual union vis-à-vis the Israeli national project. More specifically, we tease out the kaleidoscopic collage of politicians’ affective (dis)attachments in relation to Halevi, Aharish and a variety of socioculturally relevant categories such as the Israeli nation. This affective patchwork, we argue, is itself the product of a tension that is at the very heart of the Israeli nation-state, that between the policing of Jewishness as the defining principle of the Israeli national imagined community, on the one hand, and the upholding of the democratic imperative to equal treatment and recognition, on the other.

Introduction

On 28 November 2019 the inhabitants of the Israeli town of Jaljulia woke up with the sight of slashed tires and slogans spray-painted on their cars. The message of the graffiti was loud and clear: “Jews, stop intermarriage” (see Haaretz, 28 November 2019). This episode was not an isolated event but was yet another violent display of anxieties about Jewish/Palestinian intermarriage fueled by the Israeli extreme-right fringe group Lehava (see also section 2 below). Crucially, there is a gendered dimension to the fears about intimate relationships in Israel. As spelled out in their mission statement, Lehava strives towards “saving the women of Israel who have been tempted to have a relationship with a goy (i.e. non-Jewish man).” That the women in question are specifically Jewish and the problematic goyim are Palestinian is revealed by Lehava chairperson Bentzi Gopstein, who stated in an interview:

If an Arab hits on a Jewish woman, talk is not what’s needed. An Arab who hits on a Jewish woman I don’t think needs to keep walking down the street too much with his Jewish woman

In sum, scholarship of nationalism has highlighted the potentially invigorating role played by foreign women in upholding the reproductive futurity of the nation, and Lehava’s anxieties have been directed towards Jewish women having intimate relationships with Palestinian men. In contrast, in this article, we explore a somewhat different scenario, one in which a Jewish Israeli man marries a woman who, on the one hand, is not part of the ethno-religious group that defines the national community, but, on the other hand, cannot be considered as “foreign,” i.e. a Palestinian citizen of Israel.

For this purpose, we investigate a mediatized debate among mainstream Israeli politicians who commented on a celebrity heterosexual marriage between two television personalities, Tsahi Halevi and Lucy Aharish, who are both Israeli citizens but are Jewish Israeli and Palestinian Israeli, respectively. As we explain in more detail below, Israel constitutes a complex example of the relationship between citizenship and nationality: while there are approximately one million Palestinians who are citizens of Israel and should enjoy the same rights and duties as Jewish Israeli citizens, Israeli nationalism has historically been built around a Jewish Zionist idea of common origin from, and belonging to, the land of Israel, that has consistently sought to exclude – erase even – Palestinians and their symbols from the Israeli national imaginary.

In light of this, we draw upon the notion of stance (Jaffe Citation2009), coupled with a social approach to affect (Ahmed Citation2004; Wetherell Citation2012), in order to tease out the affective trouble generated by the celebrity wedding as is discursively manifested in the ambivalent, contradictory, and apparently incompatible stances taken by mainstream Israeli politicians. By offering a granular analysis of these politicians’ affective responses to a heterosexual union, the article not only seeks to contribute to current scholarship on discourse and affect, but also offers a fresh perspective on nationalism by exploring the visceral nature of national belonging.

In what follows, we begin by offering some historical background about issues of citizenship and inter-faith marriage in Israel, followed by a brief summary of the Halevi/Arish marriage debate. We will then move on to present the two theoretical notions that inform the article – stance and affect – before delving into detailed analysis of relevant excerpts from the media debate.

Background

Citizenship in Israel, inter-faith marriage and “assimilation”

The modern state of Israel is a product of the Zionist movement, which holds the ideology that Jews deserve their own nation state in their perceived homeland. When the British mandate of Palestine ended in 1948, the newly formed state of Israel established itself over most its former territory, while expelling much of the Palestinian population. Ever since, the population of Israel was mostly Jewish, but the remaining Palestinians and their descendants form a significant minority. The Palestinian minority in Israel (unlike Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank) are Israeli citizens, and officially have the same legal rights as Jewish Israelis; in practice, however, they are in many ways “second class citizens,” and suffer from considerable discrimination (Smooha Citation2013).

Zionist ideology maintains that Judaism is not just a religion, but rather a nationality, and the ethno-religious boundaries between Jewish Israelis and Palestinians are generally conceptualized in terms of a larger conflict of nationalities (Lefkowitz Citation2004). This leads to an inevitable tension between the notions of citizenship and nationality in Israel – Palestinians may be citizens of the state, but they are not considered part of the nation that defines it, nor can they be. Israel defines itself as simultaneously and equally Jewish and democratic, but as Israeli sociologist Sammy Smooha points out, “there is an inherent contradiction between the Jewish-Zionist state and democracy. Israeli democracy is not a substantive democracy based on full equality between citizens” (Citation2013; 217. See also Rouhana Citation2006; Yiftachel Citation2006).Footnote1 This tension between the Jewish and democratic nature of Israel manifests itself in many ways, the most relevant of which for our purposes is the Israeli preoccupation with Palestinian birth rates. From a Zionist perspective, there is a fear that if Palestinians’ share of the population increases, the country could no longer be sufficiently Jewish while maintaining the democratic rights of minority citizens. As a result, mainstream discourse quite often invokes the notion of a “demographic threat” looming over the future of Israel’s existence (Orenstein Citation2004).

Against this backdrop, inter-faith marriages become a matter of crossing ethnic-national lines, not just religious ones. Since Judaism is a seen as an inseparable nationality-faith combination, there is no notion of marriage to a non-Jew (Israeli citizen or not) that is equivalent to the English term “inter-faith.” An examination of the terms that Israelis do use to refer to such marriages is telling: a common phrase is nisuim meuravim, which literally means “mixed marriage,” and can refer to any mixed marriage, not necessarily inter-faith. Another term is nisuey taarovet, which literally means “a marriage of mixture,” but has different connotations: the term sounds dated and strongly implies disapproval, not unlike the English word “miscegenation.”

A further term which is used in this context did not originally refer to marriage: the word hitbolelut, which literally means “assimilation.” The term originated as part of a broad debate among Jews in nineteenth century Europe concerned with the loss of Jewish identity, and possible conversion to Christianity (Gilad Citation2018). In twenty-first century Israel, in which Jews are a majority, the term is still in use, but increasingly refers to marriages between Jews and non-Jews, and specifically to marriages between Jews and Palestinians (Gilad Citation2018). The narrowing of the meaning of the term hitbolelut is most obviously seen in the name of the Israeli extreme-right fringe group Lehava, which is an acronym for Lemeniat hitbolelut be-erets hakodeš “For the prevention of hitbolelut in the holy land.” As mentioned in the introduction, Lehava is at the vocal forefront of anti-hitbolelut rhetoric in Israel, and does not stop at rhetoric: the group became notorious in 2014 when they held a demonstration in front of wedding between a Muslim man and a Jewish woman who had converted to Islam.

Despite the Israeli anxiety about the so-called “demographic threat,” mainstream media do not typically concern themselves with inter-faith marriage as a phenomenon nor. Groups such as Lehava are widely considered racist and by no means represent the dominant view; the aforementioned Lehava demonstration was the subject of much criticism in the Israeli media, and Moshe Yeelon, then the defense minister from the ruling party Likud, tried to declare them an illegal organization. However, the issue of inter-faith marriage did become a very prominent topic of debate, involving politicians from throughout the political spectrum, in the days following the October 2018 marriage of two well-known Israeli celebrities: Lucy Aharish and Tsahi Halevi. The discourse surrounding this marriage, which unleashed a barrage of fears and anti-hitbolelut sentiments, is the focus of this paper.

The celebrity marriage of Lucy Aharish and Tsahi Halevi

Lucy Aharish, born in 1989, is one the few Muslim Palestinians citizens of Israel who have risen to prominence in the Jewish dominated Israeli media. She began her career as a news presenter, and had several successful televised talk shows, in which she often condemned Israeli racism against Palestinians. Nevertheless, she embraces her identity as Israeli, and her politics rarely stray from the views of mainstream Jewish left circles. For example, in 2015, Aharish made headlines when she lit the torch in Israel’s Independence Day ceremony, an event shunned by many Palestinian citizens of Israel who take a strong anti-Zionist stance. Aharish is a divisive figure; while generally embraced by the Jewish Israeli establishment, she suffers online harassment from right-wing groups. In Palestinian circles, she is often accused of pandering to Jewish viewers (Younis Citation2015).

Tsahi Halevi, born 1975, is a Jewish Israeli actor who became famous in Israel after appearing in the successful television show Fauda, in which he portrays an Israeli special forces officer, who is undercover in the West Bank impersonating a Palestinian. Halevy and Aharish had been dating for four years, but did not make their relationship known to the public until their wedding. The marriage was initially not headline news, and was reported in celebrity gossip columns.Footnote2 However, interest in the wedding quickly moved from the gossip pages to the social media accounts of prominent politicians, who expressed far more explicit opinions and ambivalent affective stances, thus revealing the emotional short-circuiting that this marriage causes in the Israeli psyche.

Granules of identity and affect: a stance approach

Over the last thirty years or so, the notion of identity has played a key role in sociolinguistic and (critical) discourse analytical work on sexuality. Strongly influenced by Judith Butler’s (Citation1990) concept of performativity, a large body of research has offered analytically nuanced illustrations of the multiple ways in which sexual identities are constructed, negotiated and contested via discursive means, and power imbalances are (re)produced and/or challenged (see e.g. the articles in the Journal of Language and Sexuality and the contributions to Milani Citation2018). Alongside a focus on unpacking identity work, there is a burgeoning interest among sociolinguists and (critical) discourse analysts in understanding the realm of the affective in relation to sexuality (see e.g. Borba, this issue; Milani Citation2015; Leap Citation2018). This scholarship, though, has focused primarily on the affective layerings of same-sex desire, thus sidelining the emotional investments in heterosexuality.

Of course we are not suggesting that we should all jump on the affect bandwagon, and go beyond identity, and leave it behind us; rather, in line with the remit of this special issue, we believe that we should investigate the discursive production of identities at the same time as we cast a critical gaze at what lies beside, and gives an affective valence to them. In saying so, we are inspired by queer theorist Eve Kosofky Sedgwick, who suggested that the English preposition “beside” “seems to offer some useful resistance to the ease with which beneath and beyond turn from spatial descriptors into implicit narratives of, respectively, origin and telos” (Sedgwick Citation2003, 8). “Beside” is then perhaps the best spatial descriptor through which to grasp the “irreducible entanglement of thinking and feeling, knowing that and knowing how, propositional and nonpropositional knowledge” (Zerilli Citation2015, 266, emphasis added).

Most importantly, a heuristics of the “beside” is not at odds with the political aims of the journal Social Semiotics, which overtly encourages “a critique of the limitations on and variations in the ways in which semiotic resources/practices may perpetuate biases, imbalance or legitimize and maintain kinds of power interests.” Quite the contrary, semiotic work on heterosexuality has much to gain from an engagement with emotions because an analytical focus on affect allows us to achieve a more nuanced understanding of social structures and practices, as well as gain deeper insights into the ways in which mainstream sexual politics works.

At this juncture, it is important to clarify what we mean by emotions. Drawing upon the work of cultural theorist Sara Ahmed, we believe that emotions should be taken into consideration less for their ontological status than for their performative ability to “do things, […] align individuals with communities—or bodily space with social space—[and] mediate the relationship between the psychic and the social, and between the individual and the collective” (Ahmed Citation2004, 119). According to such a performative perspective, emotions are not states lodged somewhere in people’s minds or body, and therefore invisible, but are social forces that are produced, circulated, and materialize semiotically through language. Viewing emotions as social also means taking into account their interconnectedness with reason and power, considering the often subtle ways in which discipline and control operate not so much through the mobilization of individuals’ “rational capacities to evaluate truth claims but through affects” (Isin Citation2004, 225; see also Martin Citation2014 and Richardson this issue for the interconnectedness of reason and emotion in politics).

Analytically, then, finding affect does not require us to abandon what social semioticians and discourse analysts do best – analyzing meaning-making practices and their textual outcomes – in order to embark on an esoteric quest of what is prior or external to the realm of the semiotic (see however Thrift Citation2008 and Massumi Citation1996). Inspired by the work of Ian Burkitt, discursive psychologist Margaret Wetherell explains that

feelings are not expressed in discourse so much as completed in discourse. That is, the emotion terms and narratives available in a culture, the conventional elements so thoroughly studied by social constructionist researchers, realise the affect and turn it for the moment into a particular kind of thing. What may start out as inchoate can sometimes be turned into an articulation, mentally organised and publicly communicated, in ways that engage with and reproduce regimes and power relations. (Wetherell Citation2012, 24)

While it lies beyond the scope of this article to offer an overview of the sociolinguistic and discourse analytical literature on the concept (see Jaffe Citation2009), stance is particularly apt to offer a granular picture of speakers’ identity positionings and their emotional layerings. Stance has been famously defined by Du Bois as

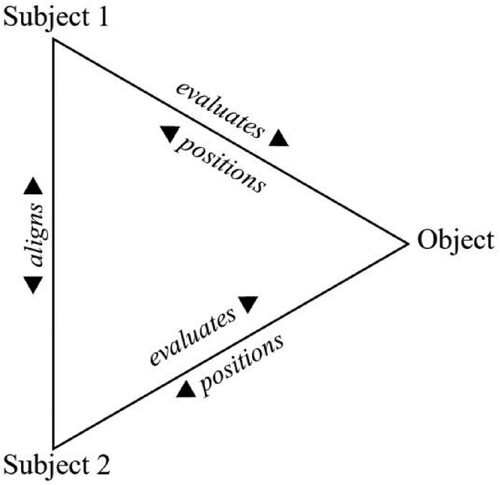

a public act by a social actor, achieved dialogically through overt communicative means […] through which social actors simultaneously evaluate objects, positions subjects (themselves and others), and align with other subjects, with respect to any salient dimension of the sociocultural field. (Citation2007, 163)

Figure 1. The stance triangle (reproduced based on Du Bois Citation2007, 163).

A plethora of terms have been employed in the literature to describe various types of stance-taking and create different taxonomies. Differences notwithstanding, there are two key elements that recur: (1) evaluation; and (2) the imbrication of evaluation with a speaker self and other positioning (Jaffe Citation2009, 7). And affect plays a “sticky” role (Ahmed Citation2004) in gelling the interstices between evaluation and positioning (see also the contributions to Peräkylä and Sorjonen Citation2012 as well as Starr, Wang, and Go Citation2020). As Jaffe explains, “displays of affective stance are resources through which individuals can lay claims to particular identities and statuses as well as evaluate others’ claims and statuses” and thereby pursue “the drawing of social boundaries that is central to the work of social differentiation” (Citation2009, 7). Put differently, affect is part and parcel of the creation of a variety of (dis)attachments to people, objects and socioculturally relevant phenomena. In the specific case of this paper, we will see in the section below how affect laminates the discursive manifestations of (1) the relationships between Israeli politicians and a specific object, a celebrity marriage between a Jewish man and a Palestinian woman; (2) these politicians’ positionings of themselves and the main protagonists in the marriage; and (3) their alignments vis-à-vis the “imagined community” of the Israeli nation.

Affective (dis)attachments in Israeli mainstream political discourse

Although there were many online news, tweets and Facebook posts addressing the wedding, we focus here on the pronouncements made by prominent politicians who can be considered mainstream in the Israeli context, as we believe that what they believe is acceptable to say in the public sphere is telling of more general and widespread sentiments in Israeli society. We demonstrate that although the views expressed are different, the key differences are not necessarily in the evaluation of the marriage itself, but rather in the affective stances undergirding said evaluation.

Much of the political interest in the marriage is due to the actions of lawmaker Oren Hazan, then a Member of Knesset (MK) from the governing right-wing Likud party. Hazan, who was serving his first term, had already garnered a reputation for himself as a trouble maker: in January 2018 the Knesset’s ethics committee had suspended him for six months following a series of inflammatory statements towards Palestinian MKs. On the day of the Aharish-Halevi wedding, Hazan wasted no time, and at 8PM promptly tweeted the following:

(1)

I don’t blame Lucy Aharish for seducing a Jewish soul in order to hurt our country and prevent more Jewish descendants from continuing the Jewish lineage. On the contrary, she’s welcome to convert (to Judaism).

I do blame Tsahi Islamifed-Levi (Hebrew pun) for taking Fauda one step too far - my brother, snap out of it.

Lucy, it’s not personal, but know this, Tsahi is my brother and the people of Israel are my people, enough with the hitbolelut!

As Martin (Citation2014, 120) argues,

emotions serve to situate subjects in relation to their world, orienting them towards its objects with degrees of proximity and urgency, sympathy and concern, aversion or hostility. These emotional orientations are never fixed or complete but are open to contestation and negotiation. (see also Richardson, this issue)

Hazan’s tweet was a spark that ignited a media firestorm: over the following couple of days, a large number of Israeli politicians also felt the need to comment on the matter. Many did so to critique Hazan’s original tweet, and call out its thinly veiled racism while congratulating the happy couple. For example, Stav Shafir, an MK from the left-wing opposition labor party, shared Hazan’s tweet on her FB with the following comment:

(2)

I will say this gently: brave and kind Lucy Aharish knows what it means to be Jewish, more than the person who tweeted this racist and repulsive tweet that I had to share here – I hope that everyone will see who we have to deal with and what kind of filth Netanyahu has brought into our homes. Congratulations Lucy and Tsahi. May you be surrounded only with love, support and the freedom to be who you are.

Although Hazan was generally critiqued and mocked for his statement, the anti-hitbolelut sentiment that he raised was in no way unanimously rejected. An interesting quote comes from the Minister of Interior Affairs at the time, Arye Der’i of the religious right-wing Shas party. In a live radio interview broadcast the day after the wedding, the interviewer, Yael Dayan, asked him if he wished to congratulate the couple, and Der’i replied with the following:

(3)

It’s clear to me that Lucy did not intend to betray the state of Israel and that they are a couple who are in love and are getting married. But this will not be the right thing for either of them. They will have children, and they will have a problem with their status in the state of Israel. If she desires a Jew, I think conversion can serve that. The matter is personal between them but if I am asked I must say that it is our duty to conserve the Jewish people.

It’s still possible to convert, this is not a good thing. I’m speaking out of experience, I see couples like this whose children encounter difficult problems with this matter, one must consider the future. We can’t encourage these things.

The interviewer’s belief that the topic merits discussion with the minister of interior affairs, as well as the minister’s willingness to engage in the conversation, speak volumes to the extent to which the marriage struck a nerve among Israelis. An analysis of Der’i’s words shows that although the tone is far more pleasant than that of Hazan’s, there is considerable similarity nonetheless.

Unlike Hazan, Der’i does evaluate Aharish and Halevi as a couple, and his general stance seems to be one of concern for their well-being. While that may seem positive, the emotion of concern is actually quite jarring, given that he is replying to a request to congratulate the couple. Furthermore, it is interesting to note how Der’i also allocates differential evaluations to the involved participants. Like Hazan, he opens with an overt evaluation of Aharish, not blaming her for the wedding. However, the word choice (“intend to betray”) reveals the speaker’s stance towards the event: Aharish’s actions are again described in terms of criminal activity, an act of treason no less. Furthermore, Der’i also speaks of Aharish’s “desire,” once again conjuring up the image of the Oriental seductress, whereas Halevi himself is never mentioned separately, as if he were an unwitting participant, lacking any agency or desire of his own. Like Hazan, Der’i frames his objection only as a matter of faith, avoiding any explicitly racist opposition to the marriage. However, his invitation for Aharish to convert also sounds rather ambivalent, as he follows it by discussing the possible future problems of their marriage. It is not obvious that he means that all issues will be resolved if she does convert, and his final words can certainly be understood as a rejection of the marriage in general, whether or not Aharish converts.

The previous examples may give the impression that politicians were split along party lines, with right-wing politicians objecting to the marriage (while varying in tone) and left-wing politicians calling them out on their racism. However, critiques of the marriage were not limited to the right-wing or religious parties. Of particular interest is Yair Lapid, the chairman of the centrist party Yesh Atid. Lapid’s entry to Israeli politics was fairly recent, following a successful career as a journalist, in which he made a name for himself as the voice of the Israeli consensus – neither too left nor too right – a perception that he wholeheartedly embraced (Mann Citation2015). In 2012, he founded Yesh Atid, as a party that defines itself as “representing the Israeli middle class, that serves in the army, works and pays taxes, but still can’t make ends meet.”Footnote3 In the 2013 general elections, Yesh Atid won 19 out of 120 seats in the Knesset, making it the second largest party. Lapid’s take on thorny topics can therefore be considered as indicative of what Israelis deem as an acceptable mainstream position. Four days after the wedding, Lapid was interviewed on the radio on the topic; afterwards he posted a long post on FB discussing both the radio interview and his views on the Aharish-Halevi marriage, which we reproduce here.Footnote4

(4)

I love Lucy Aharish. I’m happy for her on her wedding. I think that the attack on her in the last couple of days have been disgusting. The discussion about hitbolelut should not be done on top of a young couple that has just gotten married. That doesn’t mean that there’s no place for this discussion, that doesn’t mean there’s no problem, but it’s obvious that two private individuals have the right to marry whoever they like.

…

I make a distinction between this private case and the national question. I believe that most Israelis can sense this complexity. They too are humans, they too love Lucy, they too don’t want to hurt and offend, and they too would prefer that their children marry Jews. If their children don’t, they will still love them, but it will be hard on them. I think that’s their right.

…

After all it’s not just us Jews who have a problem with hitbolelut (notice that I didn’t use the term nisuey taarovet that has problematic connotations in my opinion). The vast majority of Christians, Muslims, and people of all other religions would prefer that their children marry within the community. It’s natural and it’s just human. Yes, I want my grandchildren to celebrate Passover and Hannukah, I want them to feel a deep connection to the state of Israel, it’s important for me that they speak Hebrew and feel a part of this chain of generations. I don’t think that is condescending, or xenophobic. I don’t think that whoever is not Jewish is not as good a person, or not worthy, but I am part of a community and it is important for me to preserve it. After all I don’t think my family is better than others, but that doesn’t change the fact that I love it more.

In our case, us Jews, the hitbolelut problem is even more complicated. Even though some people were angry at me for mentioning the Shoah, I think it’s very relevant to any discussion about the size of the Jewish people. There is no other people in the world that had a third of its people murdered. That’s not victimization, it’s just a fact. If there were 300 million Jews in the world, it’s likely that we would be less worried. But that’s not the case. Before World War II there were about 16.5 million Jews in the world. Today there are 14.5 million. We are a small people. If we want it to keep on existing, we must acknowledge that hitbolelut poses us with a difficult challenge.

The extremists on both sides, as usual, refuse to acknowledge this complexity. Smutrich and Oren Hazan talk in terrifying terms of racial purity. The radical left screams “racism” about the mere notion that there is a Jewish people that needs to be protected. The vast majority of Israelis, as always, stand in the middle and realize that not every problem in the world has a simple answer.

So once again, congratulations to Lucy. You think this is complicated? Wait till you see what married life is like …

The opening paragraph makes it clear that Lapid approaches the issue quite differently from Hazan and Der’i. To begin with, his initial words brim with a positive affective stance expressing his fondness towards Aharish and his excitement about the wedding. Moreover, unlike Der’i and Hazan, who “do not blame” Lucy for the wedding, Lapid explicitly says that getting married is within Aharish and Halevi’s rights. His strongly positive affective stance is further articulated in describing the attacks against them as “disgusting.” In spite of all this affective alignment with Aharish, Lapid’s text does not actually take an unequivocal stance against the critique of the wedding: the opening paragraph ends with impressive back-pedaling from what the former affective attachments may have implied (“that doesn’t mean there’s no problem”). According to Lapid, Aharish and Halevi certainly have a right to get married, but that does not mean that he does not object to hitbolelut, nor that the matter should not be discussed – the couples’ right to get married is seen as no more important than the right of Israelis to be against such marriages.

A running theme in Lapid’s post is that the matter is complicated. Lapid creates a false equivalence between “the extremists on both sides” who fail to see the complexity of the situation, allowing him to position himself as a voice of reason. It is true that both Hazan (in (1)) and Shafir (in (2)) do not present “complicated” positions; Hazan clearly states that he opposes the marriage, and Shafir says that Hazan has no right to do so. However, even though Lapid sees himself as being in the middle, the supposedly complicated viewpoint that he presents is not so different from Hazan’s rejection of the marriage. In fact, as shown above, Hazan did not explicitly use “terrifying terms of racial purity” either, and the racist implications of his position are arguably there in Lapid’s post as well, as it discusses the marriage in terms of a threat to the very existence of the Jewish people. What actually seems to be complicated is not so much Lapid’s positions, but rather the apparently contradictory set of affective (dis-)attachments that he utilizes in order to reject the marriage while simultaneously distancing himself from its other critics and expressing his devotion to Aharish. This truly complex affective patchwork allows Lapid to package incompatible stances together and combine them into a single text that reads as consistent.

While Lapid declares that his position is driven by neither racism nor xenophobia, the arguments that he raises against hitbolelut highlight the Israeli confound between the notion of religion and nation (“Yes, I want my grandchildren to celebrate Passover and Hannukah, I want them to feel a deep connection to the state of Israel, it’s important for me that they speak Hebrew”). Aharish’s grandchildren might not celebrate Passover, but she does, of course, speak Hebrew, and expresses a deep connection to Israel, as evinced by her appearance in the national Independence Day ceremony. If cultural assimilation is truly Lapid’s worry, he should have no cause for concern. But arguably, the fact that Aharish so clearly presents a model of a Palestinian who embraces Hebrew, Israeli identity, and assimilation into mainstream Jewish Israeli society, is precisely what makes her so threatening to the Zionist definition of the nation. And Lapid certainly does feel threatened, a fact that is seen most clearly in his linking of hitbolelut with the specter of the Shoah.

Lapid officially objects to Hazans’ post, but it appears that what he actually opposes is Hazan’s lack of decorum, not his assertions or the ideologies that motivate them. Lapid’s insistence that the issue is complicated serves, in fact, to legitimize Hazan’s conceptualization of the marriage as a matter of public debate. What truly separates the two is not any objective evaluation of the marriage (as both see it as a “problem”), but rather the affective lamination of how they go about addressing the issue. Whereas Hazan is openly confrontational, Lapid swings back and forth between aligning with Lucy and expressing where his true loyalties lie – the Jewish people.

Lapid’s text is riddled with incompatible stances – going directly from calling the attacks on the marriage “disgusting” to stating that “that doesn’t mean there’s no place for this discussion.” One might assume that denouncing something as disgusting does actually mean that there is no place for it; however, as argued before, it is in the nature of emotional claims to never be fixed, and always be open for debate (Martin Citation2014). Lapid’s affective somersaults can thus serve as the glue to hold his arguments together. One of the striking features of Lapid’s rhetoric is how he asserts that his own affective mindscape also applies to his target audience – the imagined average Israeli with whom he constantly aligns. By doing so, Lapid takes his reader on a rollercoaster ride that manages to be quite alluring. Unlike Hazan’s half-hearted attempts to claim that he is not racist, Lapid’s more complicated affective display offers a way to reject the marriage while still convincing oneself that racism and xenophobia really do have nothing to do with it. When we remember the elephant in the room that is never actually invoked in this debate, the convoluted Israeli notion of citizenship and the incompatibility of a state being equally Jewish and Democratic, it can become clear why Lapid’s “complicated” stance can find an eager audience.

Conclusion

In this article we have illustrated how a Jewish/Palestinian celebrity marriage offers a fruitful epistemological site for the study of the affective trouble generated by a heterosexual union vis-à-vis the Israeli national project. The normative position taken by these politicians is not so dissimilar after all to that espoused by the far-right wing group Lehava with which we opened the article, that Jewish Israelis should not marry Palestinians, whether they are citizens of Israel or not. Yet the key difference lies in the affective lamination (see also Hill Citation1995; McIntosh Citation2009) that coats this propositional content. Lehava is a right-wing extremist organization, which expressed its normative stance against Jewish/Palestinian intermarriage through fairly straightforward racist and hateful words and actions against Palestinian men. In contrast, the mainstream political discourse about the celebrity marriage between a Jewish man and Palestinian woman is characterized by a kaleidoscopic collage of affective (dis)attachments in relation to Halevi, Aharish and a variety of socioculturally relevant categories such as the Israeli nation. This affective patchwork, in turn, is itself the product of a tension that is at the very heart of the Israeli nation-state, that between the policing of Jewishness as the defining principle of the Israeli national imagined community (Anderson Citation1983), on the one hand, and the upholding of the democratic imperative to equal treatment and recognition, on the other (Smooha Citation2013).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Roey J. Gafter

Roey J. Gafter is a lecturer in the department of Hebrew Language at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. He is a sociolinguist whose work focuses on the use of linguistic resources in the construction of ethnic identities. His research explores sociophonetic variation in Hebrew, the Israeli construction of ethnic identity from a discourse analytic perspective, and contact between Hebrew and Arabic. He has published, inter alia, in the Journal of Sociolinguistics, Discourse Context & Media, and Linguistic Inquiry.

Tommaso M. Milani

Tommaso M. Milani is a critical discourse analyst who is interested in the ways in which power imbalances are (re)produced and/or contested through semiotic means. His main research foci are: language ideologies, language policy and planning, linguistic landscape, as well as language, gender and sexuality. He has published extensively on these topics in international journals and edited volumes. Among his publications are the edited collection Language and Masculinities: Performances, Intersections and Dislocations (Routledge, 2016) and the special issue of the journal Linguistic Landscape on Gender, Sexuality and Linguistic Landscapes (2018). He is co-editor of the journal Language in Society.

Notes

1 For a further critical discussion of the notion of the notion of “Jewish and democratic”, see White (Citation2012, chapter 1).

2 Such as in an article from the website mako’s “celebrity” page: https://www.mako.co.il/entertainment-celebs/local-2018/Article-96f99c66dae5661006.htm.

3 On the party website: https://www.yeshatid.org.il/%D7%94%D7%9E%D7%A4%D7%9C%D7%92%D7%94.

4 Because of space constraint, we reproduce here only an excerpt.

References

- Ahmed, Sara. 2004. “Affective Economies.” Social Text 22 (2): 117–139. doi: https://doi.org/10.1215/01642472-22-2_79-117

- Anderson, Benedict. 1983. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso.

- Butler, Judith. 1990. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. New York: Routledge.

- Du Bois, John W. 2007. “The Stance Triangle.” In Stancetaking in Discourse: Subjectivity, Evaluation, Interaction, edited by Robert Englebretson, 139–182. Benjamins: Amsterdam.

- Gilad, Elon. 2018. “From Odessa to Ramla: How Hitbolelut got its Racist Meaning.” Ha’aretz. [In Hebrew], October 18. Accessed May 2020. https://www.haaretz.co.il/magazine/the-edge/mehasafa/1.6572006.

- Hill, Jane H. 1995. “The Voices of Don Gabriel: Responsibility and Self in a Modern Mexican Narrative.” In The Dialogic Emergence of Culture, edited by Dennis Tedlock, and Bruce Mannheim, 97–147. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

- Isin, Engin F. 2004. “The Neurotic Citizen.” Citizenship Studies 8 (3): 217–235. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/1362102042000256970

- Jaffe, Alexandra. 2009. “The Sociolinguistics of Stance.” In Stance: Sociolinguistic Perspectives, edited by Alexandra Jaffe, 3–29. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Leap, William, ed. 2018. “Language/Sexuality/Affect.” Special issue of the Journal of Language and Sexuality 7 (1).

- Lefkowitz, Daniel. 2004. Words and Stones: The Politics of Language and Identity in Israel. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Mann, Rafi. 2015. “The Transmigration of Media Personalities and Celebrities to Politics: The Case of Yair Lapid.” Israel Affairs 21 (2): 262–276. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13537121.2015.1008239

- Martin, James. 2014. Politics and Rhetoric: A Critical Introduction. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Massumi, Brian. 1996. “The Autonomy of Affect.” In Deleuze: A Critical Reader, edited by Paul Patton, 217–239. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Maxwell, Alexander. 2016. “Nationalism and Sexuality.” In The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Gender and Sexuality Studies, edited by Nancy A. Naples. London: Wiley.

- McIntosh, Janet. 2009. “Social Boundaries, Self-Lamination, and Metalinguistic Anxiety in White Kenyan Narratives about the African Occult.” In Stance: Sociolinguistic Perspectives, edited by Alexandra Jaffe, 72–91. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Milani, Tommaso M. 2015. “Sexual Cityzenship: Discourses, Bodies and Spaces at Jo’burg Pride 2012.” Journal of Language and Politics 14 (3): 431–454. doi: https://doi.org/10.1075/jlp.14.3.06mil

- Milani, Tommaso M., ed. 2018. Queering Language Gender and Sexuality. Sheffield: Equinox.

- Orenstein, Daniel E. 2004. “Population Growth and Environmental Impact: Ideology and Academic Discourse in Israel.” Population and Environment 26 (1): 41–60. doi: https://doi.org/10.1023/B:POEN.0000039952.74913.53

- Peräkylä, Anssi, and Marja-Leena Sorjonen, eds. 2012. Emotion in Interaction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Rouhana, Nadim N. 2006. “‘Jewish and Democratic’? The Price of a National Self-Deception.” Journal of Palestine Studies 35 (2): 64–74. doi: https://doi.org/10.1525/jps.2006.35.2.64

- Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky. 2003. Touching Feeling: Affect, Pedagogy, Performativity. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Smooha, Sammy. 2013. “A Zionist State, a Binational State and an In-Between Jewish and Democratic State.” In Nationalism and Binationalism, edited by Anita Shapira, Yedidia Z. Stern, and Alexander Yakobson, 206–224. Brighton, UK: Sussex Academic Press.

- Starr, Rebecca Lurie, Tianxiao Wang, and Christian Go. 2020. “Sexuality vs. Sensuality: The Multimodal Construction of Affective Stance in Chinese ASMR Performances.” Journal of Sociolinguistics. Pub. ahead of print. doi:10.1111/josl.12410.

- Thrift, Nigel. 2008. Non-Representational Theory: Space, Politics, Affect. London: Routledge.

- Wetherell, Margaret. 2012. Affect and Emotion: A New Social Science Understanding. London: Sage.

- White, Ben. 2012. Palestinians in Israel: Segregation, Discrimination and Democracy. London: Pluto Books.

- Yiftachel, Oren. 2006. Ethnocracy: Land, and the Politics of Identity Israel/Palestine. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Younis, Rami. 2015. “In the Democracy According to Lucy Only Arabs Like Her are Allowed to Speak.” Sixa Mekomit [Hebrew], February 12. Accessed May 2020. https://www.mekomit.co.il/%D7%91%D7%93%D7%9E%D7%95%D7%A7%D7%A8%D7%98%D7%99%D7%94-%D7%A2%D7%9C-%D7%A4%D7%99-%D7%9C%D7%95%D7%A1%D7%99-%D7%90%D7%94%D7%A8%D7%99%D7%A9-%D7%A8%D7%A7-%D7%9C%D7%A2%D7%A8%D7%91%D7%99%D7%9D-%D7%9B%D7%9E/.

- Yuval-Davis, Nira. 1997. Gender and Nation. London: Sage.

- Zerilli, Linda. 2015. “The Turn to Affect and the Problem of Judgment.” New Literary History 46 (2): 261–286. doi: https://doi.org/10.1353/nlh.2015.0019