ABSTRACT

Few studies have focused on visual representation of crime-related events in news images across national contexts. In this study, eighty-three news images from two hundred Iranian and Dutch news articles published in national newspapers were qualitatively analyzed. These images were scrutinized for their use of semiotic strategies as well as the overall visual pattern. The findings showed few similarities and notable differences between news images in the two cultural contexts. The Visual Pattern Analysis led to identification of six visual framing patterns. While Iranian images focus on non-identifiable arrested criminals, Dutch images frame crime in terms of identifiable victims and crime location. Remarkably, crime is rarely framed in terms of social causes and solutions in either corpus. The discussion links the findings to the socio-cultural contexts in which images are produced and received. The visual discourse analysis raised questions about the production and reception of crime news images to be investigated in future studies.

Framing similar issues differently: a cross-cultural discourse analysis of news images

News images, in spite of their crucial role in news storytelling, are infrequently investigated in socio-cultural studies of news (e.g. Müller and Griffin Citation2012) and of newspapers in particular (e.g. Caple Citation2013). Yet, news images offer an essential part of societal narrative on newsworthy events. News images call attention and raise awareness with an immediacy that text cannot easily achieve, specifying aspects of news (Adam, Quinn, and Edmonds Citation2007) and increasing mass audience’s emotional reaction toward social events. A convincing example was provided in 2020 by the world-wide reactions to the images of Minneapolis police officers’ action against George Floyd. Such news images represent as well as shape particular attitudes towards socio-political issues (e.g. Iyer and Oldmeadow Citation2006; also, Franklin Citation2015). As such, news that is accompanied with imagery shows as well as affects producers’ and audiences’ cognitive understanding of social events, and guides their communication about those events (see, Van Dijk Citation1985a, Citation1985b; Broersma Citation2007).

Imagery on crime news is particularly interesting as a socio-cultural research topic. Of all media topics, crime bares a general high degree of newsworthiness. For news on crime, the public highly relies on, and is attracted to, information provided in mass media (e.g. Graber Citation1980). Media “have become central in production and filtering of crime ideas” for the public (Dowler, Fleming, and Muzzatti Citation2006, 839), and powerfully affect audiences’ understanding and shaping discourses of fear, crime and justice in society (e.g. Quinney Citation1970). As crime news is concerned with antisocial deeds and reactions thereupon, the representation of crime-related events is in itself affected by dominant cultural and political ideologies (e.g. Catalano and Waugh Citation2013). Particularly, visual depiction of crime is central in capturing meanings and emotions around crime and conveying them to audiences (Greer, Ferrell, and Jewkes Citation2007, 5), and is, as such, a dominant force in shaping cultures’ view on crime (Hayward Citation2010). This is why photojournalistic crime reportage is said to struggle between documenting and stereotyping reality (Fahmy, Bock, and Wanta Citation2014). For instance, news images on shocking crimes (such as mass shootings) may bring about civic debate and awareness (see, Taylor Citation2000) but, depending on their particular perspective, these images may also victimize criminals or desensitize the public (Moyer Citation2015).

Taking a comparative approach helps to show that choices in news are not inevitable (Entman Citation2007); this is particularly true for news imagery on crime. In this article, Iranian crime news imagery is studied and compared to those from the Netherlands. Both Iran and The Netherlands are highly developed and literate societies with longstanding journalistic traditions. Particularly for Iran, however, crime news discourse as well as news images are still under-investigated in academic research, yet inherently controversial and thus relevant from a socio-cultural viewpoint (Rafiee, Spooren, and Sanders Citation2018). In the present study, we inspect visual patterns and their contextual significance in crime news images accompanying articles that were published in Iranian and Dutch national newspapers.

The aim of our cross-cultural approach is to contribute to our understanding of culture-specific representation patterns (e.g. Örnebring Citation2012; Zelizer Citation2010). Focusing on non-western societies may provide information about the alternative function, position, and use of media and journalism practices than those already well known (e.g. Wasserman and de Beer Citation2009). As such it may help to avoid the trap of ethnocentricity, in which findings from few (usually western) cultures are generalized to other, less well-studied cultures.

Visual construction of social events in news images

Images can be analyzed from different approaches including content analysis, semiology, aesthetics, psychoanalysis, ethnomethodology, anthropology and discourse analysis, among others (see, Rose Citation2001; Jewitt and Oyama Citation2001). Discourse analysis, as Rose (Citation2001) explains, “explore[s] how images construct views of the social world” through the analysis of visual elements and their contextual meaning (141). Accordingly, it can also assist in hypothesizing about the reasons behind production of visual representations and their possible effects on audiences, with a critical perspective. Therefore, it is particularly relevant for analyzing patterns, meanings and functions of crime news images cross-culturally.

Visual framing analysis is one of the useful methods in analyzing the discourse of news images. Visual framing can be defined as the selection of some elements at the cost of others, in such a way that it implies, consciously or unconsciously, a certain perspective on the issue at hand (e.g. Van den Broek et al. Citation2010). Accordingly, it presumes that in depicting newsworthy events, photojournalists cannot record all aspects of an event from a neutral perspective (Walton Citation1984). Therefore, they report some aspects of the actual event in particular ways (Newton Citation2001). Framing occurs at the level of image as well as at the level of cognition (e.g. Carter Citation2013). At the level of the image, framing pertains to what is included in the viewing frame (strategy 1) and the way it is framed (strategy 2). At the level of cognition, the choices with respect to the visual selection and salience have the potential to represent particular meanings in a social context (strategy 3). The latter is achieved through repeated framing of social affairs in a particular way, as a result of which news media can guide the audiences in defining social problems, interpreting the causes, offering moral evaluations and suggesting solutions to those problems (Entman Citation1993). Following Van den Broek et al. (Citation2010), we call these three levels of framing respectively Selection, Salience and Spin (112). In a discourse analytical perspective toward framing, the ideologies behind visual framing and ideologies shaped by a certain framing will also be discussed (strategy 4); what Rodriguez and Dimitrova (Citation2011) call Ideological Interpretation (57). In sum, a frame can be defined as a cluster of interpretations referring to different aspects of a social issue that orient around “a certain organizing idea” (Gamson and Modigliani Citation1987, 376).

Visual framing analysis of crime news

Previous research shows that media coverage of factual crime, across different modes and media, is highly affected by dominant socio-political and socio-cultural biases (e.g. Mayr and Machin Citation2011; Catalano and Waugh Citation2013; Pritchard and Hughes Citation2006; also, Machin and Mayr Citation2013; Shahin Citation2016). Such framing can even distort the realities of crime and criminality (e.g. Grosholz and Kubrin Citation2007). In spite of their theoretical and societal relevance, crime news images published in the press are under-investigated. This is especially true for studies taking cross-national perspective. Given the interdependence of communication and cultural context (e.g. Gumperz and Hymes Citation1964) and the reported cross-cultural variety in conceptualization of journalistic values and ideals (e.g. Donsbach and Klett Citation1993), such an analysis is interesting, as the crime scenario is of generic, existential interest to all societies. As such, it makes a highly relevant case for cross-cultural comparison of visual framing, enlightening cultural effects on the conceptualization of crime events and expanding our knowledge of existing journalistic practices. Previous studies showed broad variation in photojournalism practices across cultural contexts (Kim and Kelly Citation2008) and in visual patterns used in crime reports (see, Dahmen Citation2018, 174), but a systematic cross-cultural comparative approach of visual framing in reporting crime is lacking. The research question of this study is how visual patterns of framing strategies are used and how they vary across cultures. By performing a comparative analysis of crime and crime-related events in Iranian and Dutch news images, we aim to illuminate (a) how visual framing differs between the two cultures, (b) how news ideologies are conveyed through semiotic choices, and (c) what the variation tells us about production and reception of such news images.

Our case study is a comparative corpus analysis of Iranian and Dutch crime news images, performed through Visual Pattern Analysis. The main goal of Visual Pattern Analysis is a systematic investigation of the visual construal of social events (here, crime) in news photos, scrutinizing visual journalistic practices across cultural contexts. To that effect, we study news from an under-investigated non-western society in comparison to news from a frequently investigated western society. In our study, we follow a systematic and detailed content analysis of visually presented frames including an extended number of semiotic elements (see, Appendix 1).

Case study: Iranian vs Dutch news images

The cultural contexts of the two countries under study, Iran and The Netherlands, differ in several respects, in spite of similarities. This makes the discourse analysis of media representations from the two contexts an interesting case. Such a comparison can help identify culture-specific patterns more reliably and build hypotheses about which contextual factors may have led to such representations (e.g. Renkema and Schubert Citation2018, chap.15). However, the two cultures have rarely been compared in cross-cultural analyses of journalism studies. Differences in news images of the two countries may relate to different contextual factors, including but not limited to the (history of) visual cultures, the degree and nature of political control over media, existing journalistic conventions, societal communication styles, etcetera. Here, we limit ourselves to a set of differences that seem most relevant to the scope of this study. Considering the socio-political context, Iran shows higher control and censorship in publication of news in general (Shahidi Citation2008; see Khiabany Citation2007), including news items covering politics and crime. With respect to forensic characteristics, punishments for criminal acts tend to be more severe in Iran (Rahmani and Koohshahi Citation2016). Moreover, the two cultures differ regarding the supposed purpose of punishment. In Iran, punishment can be a public affair, whereas Dutch punishments, which are fewer and more moderate (Tak Citation2008), are not publicly performed. In line with these characteristics, in the Netherlands there is much less control by the government over media and (crime) news.

The observed and documented differences can be explained in terms of the multidimensional approach to culture (Hofstede, Hofstede, and Minkov Citation2010). For comparing national cultures on the level of aggregation, Hofstede’s model distinguishes various dimensions, among which Long/Short Term Orientation and Power Distance (Hofstede Citation2011). In terms of social behavior, Iran has been described as having a lower degree of long-term orientation than the Netherlands. This fits in with a societal system that employs a more normative perspective and appreciates that the results of events are immediately visible. In addition, Iran and the Netherlands also differ in power distance, that is, the degree to which less powerful members of organizations and institutions in society accept and expect that power is distributed unequally (Hofstede Citation2011, 9). The higher degree of power distance in Iran is compatible with a high degree of control over media and punishments and its public acceptance (e.g. Ghassemi Citation2009). In contrast, the Netherlands scores very low on power distance.

There are also considerable differences with regard to the journalistic conventions between the two countries. For instance, it seems that there is more freedom in the Iranian journalistic handbooks with regard to publishing images, including “decorative images,” and in terms of instructions for editing the images, including “montage” and “collage.” Although the handbooks do not explicitly suggest to apply these techniques in (crime) news (Badii and Ghandi Citation2016), these types of images are generally supported by handbooks for their supposed effect on the audience’s creation of a vivid visual imagination of the events where it has no access to the actual event or when graphics help reduce the amount of verbal news text (375). Instructions for including such types of visuals in journalistic texts are not witnessed in widely used Dutch handbooks (e.g. Kussendrager et al. Citation2018). Our aim is to identify these patterns, particularly in crime news, and clarify their relations to the sociocultural factors of their background.

Method

Corpus

A corpus of two hundred crime news articles from four Iranian and four Dutch newspapers was used for this study. This corpus existed of randomly selected news articles through searching for five keywords: crime, rape, murder, child abuse and kidnapping.Footnote1 The use of these keywords helped us to capture reports on similar types of offences in the two countries. All of the newspapers are among the high circulation national papers. Etemad and Shargh are two Iranian serious (or broadsheet) newspapers used in the study and NRC Handelsblad and de Volkskrant are two Dutch quality newspapers. Iran and Jam-e-Jam are the Iranian popular (or tabloid) newspapers used in the study, whereas Algemeen Dagblad and De Telegraaf are their Dutch counterparts (for these distinctions, cf. Semino and Short Citation2004, 19). The 200 crime news articles were equally collected from the Iranian and Dutch newspapers that is, one-hundred of the news articles were collected from the Dutch newspapers and one-hundred from the Iranian newspapers. The news articles were checked for the presence of one or more images. An image was defined as a visual representation with specific separating framing lines around it. Among the 200 crime news articles, 58 were accompanied by a total number of 83 images. All of these images were analyzed for the present study. As we see in , the distribution of images did not follow the same pattern in the Dutch as in the Iranian newspapers.

Table 1. Distribution of the Iranian and the Dutch news images and texts in 200 news articles (100 from each country).

Analysis and procedure

In what follows, a Visual Pattern Analysis was performed, that is, an inductive content analysis of image patterns, i.e. distinct combinations of particular frames and semiotic strategies, which are expressed in distinct combinations of particular frames and semiotic strategies. The Visual Pattern Analysis was performed in three phases. First, semiotic strategies were identified, based on the expressions of selection and salience that were found in the corpus. Second, combinations of semiotic strategies were identified to find out if and what visual framing patterns the images followed. Third, it was analyzed how visual framing patterns were to be interpreted in terms of motivations behind the framing. Below, we will explain these three phases in detail.

Phase 1: identifying semiotic strategies

In this first phase, coders looked at individual categories of selection and salience. In order to analyze semiotic strategies in a systematic way, we followed certain formal criteria for coding how each of the semiotic categories of selection and salience were used in the data.

The first step was to decide which categories of selection and salience were most relevant for the analysis of our data and to determine relevant sub-categories for them, with regard to the purpose of this study and based on the categories defined in literature (e.g. Kress and van Leeuwen Citation1996; Machin and Mayr Citation2012). This was repeated several times until we came to a final set of categories and a final codebook. A category was considered relevant when it was (a) prominent in the data, and (b) relevant to the research question. For instance, it was decided that size was important but metaphoricity not, since the latter did not seem to be a key factor in our data and it was not the specific focus of our research question whereas for the former both were the case. Therefore, size was added to the codebook in terms of the absolute or relative bigness of the objects and actors. Second, a codebook was designed which included the categories and sub-categories in detail. The third step included the actual coding of the images: For each image, a coding scheme was filled in. Coding was double-checked based on the final set of categories and sub-categories.

The semiotic categories and sub-categories as considered for the present study as well as their proposed functions are briefly presented in . Appendix 1 explains the operationalization of the coding scheme in more details.

Table 2. Categories, their function and sub-categories.

Phase 2: identifying patterns of semiotic strategies

In the second phase, coders tried to discover to what extent images share similar patterns regarding function and semiotic features. We grouped images into different categories (called patterns) based on our understanding and interpretation of the meaning and significance of the images (see, Ely et al. Citation1997). An informal cluster analysis was carried out in which we considered common patterns between images based on the semiotic features defined in the first phase, identifying their functions. Note that in order to be able to choose a function one defines the spin of the image that is, what seems to be the message of the image with regard to the visual choices made at selection and salience levels and their proposed functions (see, Van den Broek et al. Citation2010, 112–113). Functions were determined following the proposed function of semiotic strategies provided in literature (e.g. Kress and van Leeuwen Citation1996). We chose the function that seemed most compatible with the semiotic feature of that image. This was done in an iterative approach based on discussion of these functions among the authors. For instance, an image showing a mugshot of a criminal depicting an identifiable face probably has the primary function to let audiences identify that actor or see him as a certain individual (Lashmar Citation2014); whereas an image depicting a criminal with blurred eyes and handcuffs on his hand is aimed at focusing on the judicial event i.e. the fact that the criminal is arrested. We then explained the variation within each pattern. Patterns were defined when images were remarkably similar in use of semiotic strategies and seemed to serve similar functions.

Phase 3: interpreting motivations for patterns

In the final phase, we interpreted the social significance of framings in the two socio-cultural contexts, including possible reasons behind such representations and possible effect of framings on the audiences. The analysis was grounded in the results of the previous phases. The final phase will be discussed in the Conclusion and Discussion section. In order to analyze the social significance of visual framing in the data, we relied on our understanding of these two contexts and the differences between them which comes partly from the literature (see above) and partly from the authors’ native and near-native knowledge (see, Ely et al. Citation1997). We will also discuss the implications that certain representation patterns may indicate for the role and function of photojournalistic news images in the two socio-cultural contexts. For instance, images showing criminals after arrest with handcuffs and in the police station can represent the effectiveness of the police and might come from the control over publication of news media.

Reliability

In pre-coding sessions on 10 example images, it was observed that the Iranian images have more complicated framing than the Dutch ones: The authors could easily agree on the coding and interpretation of the Dutch images, but the Iranian corpus needed more native perspective to be interpreted. Therefore, it was decided that, in order to check the reliability, an Iranian coder re-coded the whole corpus. Overall, the coders agreed upon most of the coding. The two coders disagreed in a few cases, predominantly related to actors’ identifiability and emotion as well as setting being depicted in a detailed way. In total, less than 10 cases led to a noteworthy discussion between 1st and 2nd coder, in the sense that they did not reach immediate agreement upon interpretation. However, in these cases, upon further explanation, the 2nd coder was able to agree with the 1st coder’s interpretation, which was noted as considered the final coding decision.

Visual discourse can be highly culture-specific (Jewitt and Oyama Citation2001). In interpreting visual discourse, having both a native perspective and a non-native one are helpful and even crucial. Having a native perspective helps the researcher to understand images from the perspective of the producers and audiences of the same culture. Yet, having a non-native perspective helps to void over-interpretation of the findings. As for the interpretation of the meanings behind visual representations and their relation to the cultural contexts (Phase 3), the Iranian and the Dutch authors discussed possibilities in several sessions and during writing of the paper. The interpretations given in this paper are the outcome of the discussions and agreement among the Iranian and the Dutch authors about the meaning and cultural significance of the visual framings.

Results

The research question of this study concerned the way crime and crime-related events are framed in Dutch and Iranian news images. We analyzed visual framing throughout the whole corpus for each of the semiotic strategies and for each image. First, we present our findings of the visual representations in each of the semiotic strategies. Subsequently, based on the combination of strategies and the supposed focus and function of each image, six patterns of semiotic strategies are discerned. For a more detailed report of the results, see Appendix 2.

Semiotic strategies

Occurrence. In the Dutch images, the occurrence of particular elements frames crime more in terms of victims and crime location, whereas in the Iranian images it frames crime predominantly in terms of criminals and judicial settings, thus focusing on the aftermath of crime from judicial perspective. For instance, in Dutch images, victims appeared most often (N = 10) and other social actors (N = 6) were also observed; criminals appeared in only 2 images and officials (N = 2) appeared where they are shown together with other social actors. By contrast, Iranian images show criminals appear in 37 cases, although victims (N = 9), officials (N = 11) and other actors (N = 14) are also observed.

Composition. In both corpora, three compositional strategies can be distinguished: Foregrounding/backgrounding, size, and centrality. Both Iranian and Dutch images vary in the use of compositional strategies to put a focus on a particular actor or object (by being depicted in the fore/background, larger/smaller, and/or more or less central rather than other, simultaneously depicted actors or objects). Thus, occurrence of the actor or object occurring in the viewing frame is further emphasized through salience in the compositional design. Notably, in Iranian images, when more than one actor is depicted, criminal and/or officials are the actors who are compositionally focused upon. It is not easy to evaluate the same compositional characteristic in the Dutch images since most of the images in the Dutch corpus depict only one (type of) actor.

Actors. In the Dutch images, victims are presented in a recognizable way and they are presented as innocent and kind; in Iranian images victims are also presented as suffering. As to criminals, both in Dutch and in Iranian images these are presented as non-recognizable (anonymized by a blur or black part on the face). A difference between the two cultures is that criminals in Dutch images are presented with regard to their social position (e.g. in the profession that they carry out in ordinary life, depicted before the crime), whereas in Iranian images they are often presented in relation to the judicial process of arresting and trial (that is, after the crime, and under judicial control). Specifically, the Iranian images depict criminals mainly in prison clothes (23 out of 32). Depicting criminals who put hands on their face seems to be a noticeable pattern in Iranian images (N = 7).

Actions. In the Iranian images crime is visually framed in terms of crime-related actions much more often than in the Dutch images. In the former, most of the images depict or imply some sort of crime-related action, and this focus is on the judicial aftermath of the crime that is, arrest, trial and investigations are emphasized. There are no judicial actors (judges, police officers) in most of the images, which suggests that the emphasis is not on fighting crime but on the action involving the criminals themselves (i.e. being or having been arrested). Other actions depicted or implied in the Iranian news images include hospitalization, social protest against crime and other aspects such as crime itself. In the Dutch corpus, the few depicted actions include mourning (N = 2) and doing general investigation (e.g. searching for body parts of a victim; N = 2) where the agents are also present.

Perspective. Perspective, in terms of distance, anchor and angle, was more varied in Iranian than in Dutch images. In the Dutch data, there is a tendency to depict actors from an eye-level angle (N = 16), front and oblique front anchor (N = 14) and very close (N = 12) distance. It must be noticed that such perspectives in Dutch news images are almost always used to represent victims; thus, the dominance of victims leads to dominance of this pattern in the Dutch corpus. In the Iranian images a closer distance is observed to officials than in the Dutch images; criminals being depicted from (oblique) back is also a trend in the Iranian corpus. A limited number of Iranian images depicts criminals from the perspective of an official, a pattern that is absent in the Dutch data.

Degree of realism. Both Iranian and Dutch images offer a high degree of realism in depicting victims and officials, and a relatively low degree of realism in depicting criminals in that the criminals’ faces are blurred etcetera; other social actors are depicted with a moderate degree of realism. However, in the Iranian corpus images are contextualized more often and more realistic or detailed photographs are used than in the Dutch images, whereas in the Dutch images, depictions offer a relatively high degree of realism with regard to actors (in particular, victims). In the Iranian corpus, most of the images were photographs (N = 53), while 5 were invented ones – a genre that was not seen in the Dutch corpus. Among the Iranian photographs, most were realistic (N = 41), although use of non-realistic images is also considerable (N = 17). Overall, the Dutch images showed 20 photographs and 5 images which show geographical area of crime location on a map. Among the photographs, only 5 showed realistic images; others (N = 20) were modified for their color saturation, setting, actors, etc.

Patterns of semiotic strategies

Based on the application of all of the semiotic strategies in each image and our holistic interpretation of that, we identified six patterns of visual framing at the level of image: Who?; Where Was It?; Emotional Aftermath; Out of Focus; Highly Manipulated; and Objectified Action. Below, we explain these patterns focusing on the semiotic strategies and variations observed in each of them as well as their hypothetical function. Illustrations that exemplify the particular framing strategies follow the explanation of each pattern. Please note that for privacy and copyright reasons, the illustrations are modified versions of example images that depict the framing strategies without revealing identity of the depicted actors and source (image effects by free online software Snapstouch, see http://www.snapstouch.com).Footnote2 The original images can be made available by the authors upon personal request.

Pattern 1, Who? (n = 56): This pattern entails a variety of images that are characterized by the contextualization and identification of the actors and the setting. In images displaying this pattern, events are depicted by identifying particular person(s) and including certain place(s) while de-identifying and excluding others. Here, the main message of the news image is expressed in terms of contextualization (the what and where of the news story) and identification (the who of the news story). This pattern includes four variations all but one of which appear in images from both countries. The variations include “contextualized but not identifiable” (N = 23; 21 Iranian, 2 Dutch), “identifiable but not contextualized” (N = 18; 11 Iranian, 7 Dutch), “neither contextualized nor identifiable” (N = 8; 8 Iranian, no Dutch), “both contextualized and identifiable” (N = 7; 4 Iranian, 3 Dutch).

The first variation (cf. for a typical example) includes images of non-identifiable criminals often taken from eye-level, frontal anchor and personal or social distances in both corpora. While the Iranian images use this pattern to show criminals in a judicial context (sometimes accompanied by officials or other actors) and depict or imply judicial actions, in the Dutch images they are depicted in their work area. These images are remarkable as they characterize the criminals not with regard to their personal identity but according to their criminality or social position. The second variation (cf. ) is used to portray actors that sometimes are identifiable, but presented without a clear setting. These images are almost always taken from eye-level, frontal anchor and very close distance. Exclusion of the setting in these images puts further emphasis on the identifiable actor. Whereas in the Iranian images, it depicts officials, criminals and victims, in the Dutch images the pattern is only used to depict victims. It seems that this pattern is used to build a close relation between the viewers and the victims, to identify victims and criminals, and to observe the actual officials following the crime case.

Portraits of unidentifiable actors in an unclear setting appear only in the Iranian corpus and are almost always used to present arrested criminals that cannot be identified (cf. ). In these images, which are mostly taken from eye-level, front or oblique front and personal distance, the context is excluded by cutting off the picture or manipulated by some art technique (blur, drawing). It is not easy to distinguish the function of these images, but it seems that the rationale behind showing such depictions is to offer evidence that “the criminal is indeed arrested, under investigation, etc.,” thus emphasizing the judicial aspect of crime events.

The final variation (cf. ) is used to depict identifiable officials or criminals in a judicial setting taken from eye-level, front and relatively close distance, in the Iranian corpus; the Dutch news images use this pattern to depict identifiable victims from eye-level, front anchor and close personal distance, in a setting which is more or less included in the viewing frame. While the Dutch images offer closer proximity and seem to be used to give the opportunity of identifying the victims or build a closer personal relation between them and the viewer, the Iranian ones offer more observation of the context and seem to contextualize the viewer in such images.

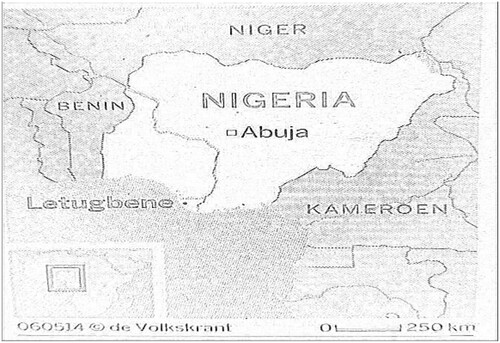

Pattern 2, Where Was It? (n = 10): This pattern depicts geographical areas (on a map), which occupy the whole viewing frame. This pattern appears more often among the Dutch images (N = 7) than in the Iranian corpus (N = 3). It is not easy to interpret this pattern based on the criteria defined for perspective: The viewer is offered a map or a depiction of the crime location in the whole image with no actors, thus no angle, distance or anchor can be defined the same way as it is for the actors. Although the image does not depict any actions, it indirectly refers to crime itself. The function of this pattern is probably to specify the exact or approximate location in which crime has occurred (the where of the news story) ().

Pattern 3, Emotional Aftermath (N = 10): This pattern frames crime in terms of the emotional aftermath of the criminal acts and has two variations. The first variation frames events in terms of physically or emotionally injured passive victims and other social actors (e.g. their families) (cf. for a typical example). Unlike pattern 1, identification of the person or place is not the main focus in images of this pattern; instead, the emotional aftermath is the main focus. This pattern depicts the actors from an intimate or close personal distance from front or front oblique and eye-level or high angle, and has two variations: Either depicting the individual’s face (N = 5) or depicting the body parts of an actor (N = 2). Actors are not necessarily identifiable. This pattern is used in Iranian depictions of victims (N = 5) and Dutch depictions of secondary victims (N = 2). While the former focuses on hospitalization and crime, the latter focuses on emotional reactions such as crying. Iranian images following this pattern show a higher degree of realism and details compared to the Dutch ones. The function of this pattern can be to depict the aftermath of crime in terms of emotional and physical effects on (secondary) victims.

Figure 6. Example of image depicting emotionally affected and passive actors (Jam-e-Jam, January 20, 2014).

The other variation of this pattern is used to present protesters while actively protesting against crime events in society, from eye-level angle, front anchor and social distance (). Images in this pattern also imply that citizens are emotionally affected by crime (being angry and dissatisfied), but the main focus is on their active participation in showing their anger. The actors are more-or-less identifiable and the image is set in a social context. This pattern is only observed in the Iranian reports and shows images with a relatively high degree of realism with regard to actors, settings and the image itself. The function of this pattern could be to depict people’s active reaction toward crime events in society.

Pattern 4, Out of Focus (n = 5): This pattern depicts an overall public setting with some officials or other actors from a far social, public or impersonal distance who, in some cases, conduct crime-related actions. This pattern offers the viewer an overall far-reaching view of the crime location, official setting, etc. from eye-level angle and different anchors, and presents a high degree of realism with regard to the overall setting. It is used to frame events both in the Iranian (N = 1) and in the Dutch (N = 4) images (cf. ). In both sets of data, this pattern is used to depict a number of officials and/or other actors. The function of this pattern might be to offer audiences a general overview of the crime location or crime-related actions, without giving precise visual information about or focusing on a specific aspect. In one of the Dutch images, a number of Syrian protesters are depicted while protesting: Although this image seems to have applied pattern 3 (i.e. Emotional Aftermath: collective reaction), since the image is depicting a number of protesters which are not protesting against crime but are only displayed as quasi-criminals, this image also seems to have an “out-of-focus” function.

Pattern 5, Highly Manipulated (n = 3): Very few Iranian images represent highly manipulated images (cf. ) that are noticeable for their representation of non-realistic scenes, actors, settings or (non-realistic) combination of more than one event in one single image. These images and the other patterns mentioned above are not mutually exclusive categories; thus, all of the three invented images also express pattern 1.

Pattern 6, Objectified Action (n = 2): Very few Iranian images only show judicial objects and crime tools: One depicted a number of handcuffs locked in each other () and the other depicted some drugs discovered from the criminals after their arrest. In both cases, the degree of realism is high in terms of objects but low in terms of the setting. The former could be an example of what Iranian journalism handbooks call a “decorative” image which is supposed to attract audiences and give them more (interpretive) information (see, Badii and Ghandi Citation2016). In this pattern, the image of crime tools may not only serve a depicting function but also represent actions: The function of this pattern seems to be to explain crime and/or judicial actions without a clear reference to the actors or settings, thus in a more general sense (i.e. not individualized in terms of only specific actors).

Figure 9. Example of image depicting judicial objects i.e. a number of handcuffs (Jam-e-Jam, November 7, 2013).

Most of the images in our data depict realistic images. The three invented images, of which is an example, show the complete opposite. This image focuses on the arrested criminal, a woman sitting on a chair who is accused of having abducted and abused a boy, and the frightened victim being abused and trying to defend himself. The image remarkably deviates from realistic depiction of events in a number of ways: in terms of time, blending of actions, setting, size and perspective. The victim is depicted at the time of abuse, which is rare in the depiction of crime events, and the criminal is depicted at some time after her arrest. The size of the components is also remarkable. The victim (a child) is presented as much bigger than the criminal (an adult). The criminal’s hands depicted in the middle in an integrated frame are almost the same size as the criminal and are depicted from a different anchor. The lack of realism carries on into the features that were further added to the image. Consider for instance the shadow of the child on the wall: it suggests she is defending herself but it is unrealistic in that it is not isomorphic to the body posture of the child. The image is also remarkable because it blends different actions (i.e. crime, arrest and imprisonment) occurring at different times and places in the real world, in a single viewing frame. The invented setting with an illusionary background adds to the non-realistic nature of the image.

This image is symbolic and can as such be seen as an example of crime and punishment rather than as an illustration or clarification of the criminal event. The image is amalgamated from different sources to transfer several messages. It seems that the journalist tries to exploit this non-realistic depiction to tell his/her story of “the innocent child who has been abused by the villain and the villain who is now in handcuffs awaiting to pay for her wrong-doing.” An informal check showed that his type of symbolic depiction is quite common on the crime pages of the Iranian newspaper Jam-e-Jam. It seems that this image is a “collage” and that the aim is to give as much information as possible by adding scenes from two different events and be preventive by showing crime scene (see Badii and Ghandi Citation2016, 375).

To summarize, the Iranian and the Dutch corpus show few similarities and prominent differences in framing crime. The similarities are limited to use of compositional strategies and the overall presence of most of the visual patterns in news images from both countries. For instance, both Dutch and Iranian images offer a high degree of realism in depicting victims and officials, and a relatively low degree of realism in depicting criminals. Beside the difference in number of images from the two countries (see ), Iranian and Dutch images also show prominent differences in semiotic strategies and the patterns that these semiotic choices shape. This is true both for the variation of patterns and the dominance of certain types over others. The Dutch images frame crime more in terms of victims and crime location and much less in terms of crime-related actions. Victims are presented as kind people we see around in everyday life and criminals are presented with regard to their social position. The Iranian images frame crime predominantly in terms of the criminals under judicial control, and may present victims as suffering from crime. Thus, the images offer a judicial perspective. With regards to visual patterns, Iranian images show more variety, although this is about a bigger corpus. Certain patterns are not observed in the Dutch images at all. When the same pattern is observed in both corpora, differences are often observed in focus or variation of the pattern.

Conclusion and discussion

The research question of this study concerned how crime and crime-related events are framed in Dutch and Iranian crime news images. The Visual Pattern Analysis led to identification of six visual framing patterns in reporting crime, a few similarities and a considerable number of prominent differences between visual framing in crime news images from the two countries. The differences between the Dutch and the Iranian news images confirm previous findings that photojournalistic discourses can be highly culture-dependent (Kim and Kelly Citation2008; cf. Krzyżanowski Citation2014). Also, the deviation of Iranian news images from western conventions shows that Iranian journalists have their own journalistic conventions and do not merely follow western values. We also found that only 29 percent of news texts were accompanied by images. Although this may demonstrate the general privilege of texts over images for journalists (e.g. Zelizer Citation2004) or may be the result of limitations on producing or publishing crime-related images, our data also show that this can significantly vary across cultural contexts. Crime news in the Iranian newspapers appears to be accompanied by crime-related images three times more often than crime news in the Dutch newspapers (45% vs 13%). The higher number of images in the Iranian news reports suggests that Iranian media pay more attention to visual depiction of crime than the Dutch media. This may relate to a previous finding that Iranian news stories are relatively lengthy and employ a storytelling format in narrating news (Rafiee, Spooren, and Sanders Citation2018). One interpretation of the number of images in Iranian news is that images help narratives by making news more interesting, helping the flow of storytelling and enriching information. If this is the case, this raises the issue whether audiences show higher comprehension or enjoyment of reading Iranian crime news. Or do Iranian and Dutch audiences prefer reading familiar crime news following the conventions of their own press? Whether the higher emphasis on visual depictions relate to a difference in communication styles, production rules or different access to images in the two countries needs further investigation.

Our findings show that whether the dominant tendency of the media is to depict the perpetrators or the victims can also depend on the cultural context (cf. Dahmen Citation2018). The higher emphasis on criminals and judicial aspects in Iran and on victims in the Netherlands mirrors a similar finding in an analysis of the language of news texts (Rafiee, Spooren, and Sanders, Citationunder review). The relatively high number of depictions in Iranian newspapers of judicial settings, actions and actors suggest that the agency of crime as a social issue lies with the judicial system. Crime is presented as something that must be punished, suppressed or controlled, rather than something that could be viewed from the angle of the victim. Similarly, the higher focus of the Dutch news on victims and lower attention to criminals and official aspects represents crime with special emphasis on those who are targeted by criminal acts that is, the victims. How these different representations are perceived by readers from the two contexts and by individuals with different ideologies is another topic for future research.

The use of manipulated images in the Iranian media and their absence in Dutch media could be an indication that within Iranian journalistic discourse there is more freedom with respect to such images, although it should be noted that we are talking about small numbers. But these invented images could also serve an informative function, for example in case the journalist does not have access to (better) photos. Both of these hypotheses are supported when we compare instructions in Dutch and Iranian academic handbooks of journalism; the former is also observed for suggested textual structures (see, Rafiee, Spooren, and Sanders Citation2018, 65). The Iranian handbooks of journalism, for instance, emphasize using images and allow for many more variations than Dutch handbooks as they believe that visuals help readers imaging the actual events (see, Badii and Ghandi Citation2016, chap. 7). This could also explain the presence of more images in Iranian crime news. The Dutch journalism, on the opposite, seem to strive for the so-called objectivity norm by capturing more realistic images. A follow-up question is how widely used these types of remarkable images are. Do they play an informative or entertaining role for the audiences and how does this differ across cultural contexts? What kind of reactions do such images evoke in different cultures?

Our findings add to the body of knowledge about news photojournalism in western and non-western countries. Our study is one of the first to offer a cross-cultural corpus-based news analysis of visual reporting of different crimes across cultural contexts, although the current analysis is only the start of a cross-cultural comparison. This comparison helped us to identify frames in a reliable and reproducible way; it also showed that journalistic practices can vary across socio-cultural contexts. We followed a systematic approach to explain meaning making in news images, which has been argued to be missing from the literature (Caple Citation2013), as well as a replicable analysis of visual framing using a detailed model of analysis and scrutinizing different semiotic strategies. Finally, our interpretations of the results raised questions and hypotheses for further research into photojournalistic practices especially in the Iranian culture. Beside the above mentioned topics for future research, it would be interesting to study how visual representations of crime news may vary in different types of newspapers or in depictions of domestic versus foreign crime events.

Acknowledgement

We would like to express our gratitude to Ali Kafi for his assistance in re-coding the whole corpus as well as to the two anonymous reviewers for their invaluable comments on a first version of the manuscript. Data are available upon request to the corresponding author by email.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Afrooz Rafiee

Afrooz Rafiee is a final-year PhD candidate and teacher at Radboud University Nijmegen. Her research, teaching and supervision concerns comparative discourse studies with a focus on journalistic texts and images. In her PhD project, she investigates crime news discourse in Dutch and Iranian national newspapers by looking at discourse structure, linguistic formulations and visual framing as well as the differences between journalism education in the two cultural contexts. Recently, she is engaged in research on emotion representation in (journalistic) discourse.

Wilbert Spooren

Prof. Dr Wilbert Spooren (1956) got his PhD from Radboud University Nijmegen (1989). He published on text structure and text quality, and has a specific interest in texts functioning in new media. He is presently professor of Discourse Studies of Dutch at the Centre for Language Studies, Radboud University Nijmegen.

José Sanders

José Sanders is professor of Narrative Communication at the Communication and Information Sciences department of Radboud University Nijmegen, The Netherlands. Her research expertise is rooted in the domain of cognitive text linguistics and her research examines the form and function of text characteristics in various discourse genres, specifically narratives. Projects concern for example the use of narrative techniques (quotation, perspective, naming and framing) in genres such as journalistic news articles, and the cognitive representation of their corresponding linguistic forms (represented voice, viewpoint, reference, metaphor) in readers. She examines in current projects how narrative reports function in journalistic media and health communication.

Notes

1 The corpus was collected for and previously used in another study, which is reported in Rafiee, Spooren, and Sanders (Citation2018). All of the articles were hard news texts about crime; therefore, no opinion or commentary articles were included.

2 Different effects had to be used for different images. The use of effects depended on (a) the possibility of applying a certain effect on an image as well as (b) the quality of the image after change.

References

- Adam, Pegie S., Sara Quinn, and Rick Edmonds. 2007. Eyetracking the News: A Story of Print and Online Reading. St. Petersburg, FL: Poynter Institute.

- Badii, Naiim, and Hossein Ghandi. 2016. Rʊ̈znɑmenegɑrɪye Novɪn [Modern Journalism]. 10th ed. Tehran: Allɑme Tæbɑtæbɑyɪ University.

- Broersma, Marcel, ed. 2007. Form and Style in Journalism: European Newspapers and the Representation of News, 1880–2005. Leuven: Peeters.

- Caple, Helen. 2013. Photojournalism: A Social Semiotic Approach. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Carter, Michael J. 2013. “The Hermeneutics of Frames and Framing: An Examination of the Media’s Construction of Reality.” Sage Open 3 (2): 1–12. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/2158244013487915.

- Catalano, Theresa, and Linda R. Waugh. 2013. “The Ideologies Behind Newspaper Crime Reports of Latinos and Wall Street/CEOs: A Critical Analysis of Metonymy in Text and Image.” Critical Discourse Studies 10 (4): 406–426.

- Dahmen, Nicole S. 2018. “Visually Reporting Mass Shootings: US Newspaper Photographic Coverage of Three Mass School Shootings.” American Behavioral Scientist 62 (2): 163–180.

- Donsbach, Wolfgang, and Bettina Klett. 1993. “Subjective Objectivity: How Journalists in Four Countries Define a Key Term of Their Profession.” International Communication Gazette 51 (1): 53–83.

- Dowler, Kenneth, Thomas Fleming, and Stephen L. Muzzatti. 2006. “Constructing Crime: Media, Crime, and Popular Culture.” Canadian Journal of Criminology and Criminal Justice 48 (6): 837–850.

- Ely, Margot, Ruth Vinz, Maryann Downing, and Margaret Anzul. 1997. On Writing Qualitative Research: Living by Words, no. 12. London: The Falmer Press.

- Entman, Robert M. 1993. “Framing: Toward Clarification of a Fractured Paradigm.” Journal of Communication 43 (4): 51–58.

- Entman, Robert M. 2007. “Framing Bias: Media in the Distribution of Power.” Journal of Communication 57 (1): 163–173.

- Fahmy, Shahira, Mary A. Bock, and Wayne Wanta. 2014. Visual Communication Theory and Research: A Mass Communication Perspective. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Franklin, Stuart. 2015. “In a World of Words, Pictures Still Matter.” The Guardian, December 5. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2015/dec/05/world-words-photos-matter-photojournalism-reportage.

- Gamson, William A., and Andre Modigliani. 1987. “The Changing Culture of Affirmative Action.” In Equal Employment Opportunity: Labor Market Discrimination and Public Policy, edited by Paul Burstein, 373–393. New York: De Gruyter.

- Ghassemi, Ghassem. 2009. “Criminal Punishment in Islamic Societies: Empirical Study of Attitudes to Criminal Sentencing in Iran.” European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research 15 (1-2): 159–180.

- Graber, Doris A. 1980. Crime News and the Public. New York: Praeger.

- Greer, Chris, Jeff Ferrell, and Yvonne Jewkes. 2007. “It’s the Image That Matters: Style, Substance and Critical Scholarship.” Crime, Media & Culture 3 (1): 5–10.

- Grosholz, Jessica M., and Charis E. Kubrin. 2007. “Crime in the News: How Crimes, Offenders and Victims Are Portrayed in the Media.” Journal of Criminal Justice and Popular Culture 14 (1): 59–83.

- Gumperz, John J., and Dell Hymes. 1964. “Directions in Sociolinguistics: The Ethnography of Communication.” American Anthropologist 66 (6): 1–186.

- Hayward, Keith. 2010. “Opening the Lens: Cultural Criminology and the Image.” In Framing Crime: Cultural Criminology and the Image, edited by K. Hayward and M. Presdee, 13–28. New York: Routledge.

- Hofstede, Geert. 2011. “Dimensionalizing Cultures: The Hofstede Model in Context.” Online Readings in Psychology and Culture 2 (1). doi:10.9707/2307-0919.1014.

- Hofstede, Geert, Gert Jan Hofstede, and Michael Minkov. 2010. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Iyer, Aarti, and Julian Oldmeadow. 2006. “Picture This: Emotional and Political Responses to Photographs of the Kenneth Bigley Kidnapping.” European Journal of Social Psychology 36 (5): 635–647.

- Jewitt, Carey, and Rumiko Oyama. 2001. “Visual Meaning: A Social Semiotic Approach.” In Handbook of Visual Analysis, edited by Theo van Leeuwen and C. Jewitt, 134–156. London: Sage.

- Khiabany, Gholam. 2007. “Iranian Media: The Paradox of Modernity.” Social Semiotics 17 (4): 479–501.

- Kim, Yung-Soo, and James D. Kelly. 2008. “A Matter of Culture: A Comparative Study of Photojournalism in American and Korean Newspapers.” International Communication Gazette 70 (2): 155–173.

- Kress, Gunther R., and Theo van Leeuwen. 1996. Reading Images: The Grammar of Visual Design. London: Psychology Press.

- Krzyżanowski, Michał. 2014. “Values, Imaginaries and Templates of Journalistic Practice: A Critical Discourse Analysis.” Social Semiotics 24 (3): 345–365.

- Kussendrager, Nico, Piet Bakker, Aline Douma, Gonnie Eggink, Esther van der Meer, and Malou Willemars. 2018. Basisboek Journalistiek. 6th ed. Groningen: Noordhoff Uitgevers.

- Lashmar, Paul. 2014. “How to Humiliate and Shame: A Reporter's Guide to the Power of the Mugshot.” Social Semiotics 24 (1): 56–87.

- Machin, David, and Andrea Mayr. 2012. How to Do Critical Discourse Analysis: A Multimodal Introduction. London: Sage.

- Machin, David, and Andrea Mayr. 2013. “Personalising Crime and Crime-Fighting in Factual Television: An Analysis of Social Actors and Transitivity in Language and Images.” Critical Discourse Studies 10 (4): 356–372.

- Mayr, Andrea, and David Machin. 2011. The Language of Crime and Deviance: An Introduction to Critical Linguistic Analysis in Media and Popular Culture. London: Continuum.

- Moyer, Justin W. 2015. “Graphic N.Y. Daily News Cover on Virginia Shooting Criticized as ‘Death Porn’.” The Washington Post, August 27. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/morning-mix/wp/2015/08/27/n-y-daily-news-executed-on-live-tv-cover-criticized-as-death-porn/.

- Müller, Marion, and Michael Griffin. 2012. “Comparing Visual Communication.” In The Handbook of Comparative Communication Research, edited by Frank Esser and Thomas Hanitzsch, 94–118. New York: Routledge.

- Newton, Julianne. 2001. The Burden of Visual Truth: The Role of Photojournalism in Mediating Reality. London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Örnebring, Henrik. 2012. “Comparative Journalism Research – an Overview.” Sociology Compass 6 (10): 769–780.

- Pritchard, David, and Karen D. Hughes. 2006. Patterns of deviance in crime news. Journal of Communication 47 (3): 49–67.

- Quinney, Richard. 1970. The Social Reality of Crime. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers.

- Rafiee, Afrooz, Wilbert Spooren, and José Sanders. 2018. “Culture and Discourse Structure: A Comparative Study of Dutch and Iranian News Texts.” Discourse & Communication 12 (1): 58–79.

- Rafiee, Afrooz, Wilbert Spooren, and José Sanders. Under review. “Framing Similar Issues Differently: A Comparative Analysis of Dutch and Iranian News Texts.” Language & Communication

- Rahmani, Tahmineh, and Nader Mirzadeh Koohshahi. 2016. “Introduction to Iran's Judicial System.” Journal of Law, Policy & Globalization 45: 47–54.

- Renkema, Jan, and Christoph Schubert. 2018. Introduction to Discourse Studies. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Rodriguez, Lulu, and Daniela V. Dimitrova. 2011. “The Levels of Visual Framing.” Journal of Visual Literacy 30 (1): 48–65.

- Rose, Gillian. 2001. Visual Methodologies: An Introduction to Researching with Visual Materials. London: Sage.

- Semino, Elena, and Mick Short. 2004. Corpus Stylistics: Speech, Writing and Thought Presentation in a Corpus of English Writing. London: Routledge.

- Shahidi, Hossein. 2008. “Iranian Journalism and the law in the Twentieth Century.” Iranian Studies 41 (5): 739–754.

- Shahin, Saif. 2016. “Framing ‘Bad News’ Culpability and Innocence in News Coverage of Tragedies.” Journalism Practice 10 (5): 645–662.

- Tak, Peter J. 2008. The Dutch Criminal Justice System. Nijmegen: Wolf Legal Publishers.

- Taylor, John. 2000. “Problems in Photojournalism: Realism, the Nature of News and the Humanitarian Narrative.” Journalism Studies 1 (1): 129–143.

- Van den Broek, Jos, Willem Koetsenruijter, Jap de Jong, and Laetitia Smit. 2010. Beeldtaal: Perspectieven voor Makers en Gebruikers. Meppel: Boom Lemma.

- Van Dijk, Teun Adrianus. 1985a. “Introduction: Discourse Analysis in (Mass) Media Communication Research.” In Discourse and Communication: New Approaches to the Analysis of Mass Media Discourse and Communication, edited by Teun van Dijk, 1–9. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

- Van Dijk, Teun Adrianus. 1985b. “Structures of News in the Press.” In Discourse and Communication: New Approaches to the Analysis of Mass Media Discourse and Communication, edited by Teun van Dijk, 69–93. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

- Walton, Kendall L. 1984. “Transparent Pictures: On the Nature of Photographic Realism.” Critical Inquiry 1 (2): 246–277.

- Wasserman, Herman, and Arnold S. de Beer. 2009. “Towards De-Westernizing Journalism Studies.” In The Handbook of Journalism Studies, edited by K. Wahl-Jorgensen and Thomas Hanitzsch, 448–458. New York: Routledge.

- Zelizer, Barbie. 2004. “When War is Reduced to a Photograph.” In Reporting War: Journalism in Wartime, edited by Stuart Allan and Barbie Zelizer, 115–135. London: Routledge.

- Zelizer, Barbie. 2010. About to Die: How News Images Move the Public. New York: Oxford University Press.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Detailed explanation of the model of analysis

The coding scheme included the following variables.

Occurrence. At this level, we merely coded which actor(s), object(s) and setting were depicted in the image. Main participants were categorized as officials, criminals, victims, and other. “Officials” referred to policemen and judges; “others” could include doctors, victims’ family members, etc.

Objects were divided into three categories: “judicial” objects such as handcuffs and court counter, “hospital” materials like bed and survival machines, “crime” tools and “other” objects such as stationary materials, chairs, etc.

Settings were categorized as “judicial,” such as police station, court or prison, hospital, “public” including depictions of events on the street, “geographical area” such as depiction of maps or crime location, “other” and “unclear” settings.

Composition. In order to analyze composition of the actors and elements, we considered size, being foregrounded or backgrounded and centrality, and asked: Which element is bigger than the other(s)? Or, which element(s) occupy a considerable part of the viewing frame? Which actors and objects are foregrounded? Which actor or actors are put in the absolute or relative center of the image?

Actors. Actors were categorized in images based on their emotion (through body pose and facial expression), clothing and being active or passive. We coded emotion based on facial expression and/or body pose as negative (sad etc.), positive (laughing etc.) or neutral. Clothing was coded as “every day,” “uniform,” “prison,” “hospital.”

Actions. For the analysis of actions, we asked: What action, event or process is depicted or implied in the image? Is the agent present or absent? Actions were categorized as “crime,” “hospitalization,” “judicial” (e.g. arrest, trial) and “other crime-related” actions (e.g. protesting against crime). Implied actions were those that could be inferred from settings, objects and actors; depicted actions were those that are depicted in images through explicit presentation of the action at the moment of happening. The second question had two categories of present or absent.

Perspective. In order to analyze perspective, the image was coded for angle, anchor and distance. Categories for coding angle were bird-eye, high, eye-level, low, worm. Anchor was coded as frontal, back, oblique, front-oblique and back-oblique. Distance was coded as intimate (only head and neck), close personal (head, neck and shoulders), far personal (upper body), close social (head up to knees), far social (whole body), public (all the body observed and other social actors could be placed in the viewing frame) and impersonal (actor depicted from quite far distance).

Degree of realism. For the analysis of the degree of realism, we analyzed to what extent the image captures naturalistic and detailed depictions in showing actors, setting and the overall image, separately. For actors, we asked: Has the actor been depicted in a naturalistic moment or is s/he posed for the photo in one or another way? Is the actor’s face in the image identifiable (detailed capture of the actor’s face), not identifiable or manipulated (blurred face or covered eyes)? Is the depiction of the actor a realistic or a non-realistic, invented one (e.g. drawings, Photoshop)?

To establish the setting’s degree of realism, we asked: Is the setting included or excluded? Does the image depict a detailed or a non-detailed setting (i.e. does it belong to a specific context shown in details)? Is the setting naturalistic, invented (i.e. artificially created by Photoshop or drawing) or manipulated (e.g. naturalistic setting with manipulations of light)?

The analysis also looked at the overall image and asked whether the image depicted the scene as it appeared in the real world: Does the image present a photograph or is it an invented image? Does the image represent a real-world scene considering the color, naturalness in depiction of actors, objects and setting, composition and other characteristics? Invented images are not representations of a real-world scene but they are (partly) manipulated or created by editors or other responsible producers. Another issue is whether the image captures depth. In order to measure depth, we looked at contrasting sizes, shadow and light and also converging lines to see if a 3D space was created. Images were then coded as having or lacking depth.

Appendix 2. Detailed report of quantitative findings

Occurrence. Overall, in 18 Dutch images (13 news articles) at least one actor was depicted: Victims appeared the most (N = 10) and other social actors (N = 6) were also observed; criminals appeared in only 2 images and officials (N = 2) appeared where they are shown together with other social actors. The latter is the only image that depicts two different types of actors. Objects appeared in 12 Dutch images: judicial objects (a gun) appeared only once and 12 images depicted other general objects such as books, trees, homes, etc.; no hospitalization materials were depicted. Among the Dutch news images containing a depiction of the setting (N = 20), 8 depicted public settings, 5 showed geographical areas and in 2 cases the setting is unclear; no image depicted a judicial setting or a hospital; in 3 cases, it was not easy to recognize the setting as a public area or other type of setting. Half of the images depicting setting (10 out of 20) show approximate or precise areas where the crime occurred.

In the Iranian corpus, actors are observed in 53 images (41 news articles), objects in 38 and settings in 45 images. In 14 images, more than one type of actor is depicted. Overall, criminals appear in 37 images, although victims (N = 9), officials (N = 11) and other actors (N = 14) are also observed. In Iranian images, a variety of patterns in depicting actors is observed. This includes depiction of criminals (N = 27), victims (N = 5), officials (N = 3), others (N = 4), criminals and officials (N = 3), criminals and victims (N = 1), criminals, officials and others (N = 4), criminals and other (N = 2), official and other (N = 1), victim and other (N = 3). Judicial objects such as handcuffs and court counters were observed in 16 images, hospitalization materials in 4, crime tools in 1 and other general objects in 28 images. As for setting, judicial settings were observed the most (N = 26), followed by public spaces (N = 9), geographical areas (N = 2) and other places (N = 1); in 7 images, an unclear setting was depicted.

Composition. In both corpora, all of the three compositional strategies namely foregrounding, size and centrality are more-or-less used to focus the depicted actors further. In most of the images, the included actors are foregrounded, occupy a considerable part of the viewing frame and are often put in the absolute or relative center of the image. Thus, what is included in the viewing frame (selection) is further emphasized through compositional design (salience).

In a few images in both corpora, it is also objects and places that are focused upon through compositional design: These include crime locations, geographical areas, crime tool and other general objects; in the Iranian images, judicial objects are also focused upon. When more than one actor is depicted in Iranian images, criminal and/or officials are the actors who are compositionally focused upon; it is not easy to evaluate the same compositional characteristic in the Dutch images since most of the images in the Dutch corpus depict only one (type of) actor.

Actors. Overall, Dutch news images present the criminals and victims before the occurrence of the crime, whereas Iranian news images depict them both before and after the crime event. In Dutch news images, victims are shown in portrait format with neutral or positive (smiling) emotion; officials are depicted in official suits with neutral emotions. In 3 images, other actors are depicted with a negative emotion; 2 of these depict second victims and one shows quasi-criminals. In the two images depicting actual criminals, these actors are depicted with eyes covered, while one (swimming trainer) is wearing a uniform (swimsuit) with no clearly recognizable emotion and the other one everyday clothes with a positive posture.

In the Iranian corpus, criminals are mainly depicted in prison clothes (23 out of 32). Depicting criminals who put hands on their face seems to be a noticeable pattern in Iranian images (N = 7). This way of presenting actors is only observed in the depiction of criminals and its function seems to be two-fold: It makes them unidentifiable, and applies a negative body pose to them. Other actors are shown in everyday clothes and officials in uniforms or formal everyday clothes and victims are depicted in hospital or every day clothes. When facial or bodily expression is clear, actors often show a negative (22 out of 44) or a neutral emotion (N = 19). The negative emotion is often observed in criminals (e.g. downward posture and hands on face), although such emotion is sometimes attributed to hospitalized victims and other social actors (e.g. angry protesters). There are also 3 depictions of victims with positive facial expressions (e.g. smiling).

Actions. There is a higher tendency in Iranian images than in Dutch images to depict or imply (crime-related) actions. In the Dutch corpus, the few depicted actions include: mourning (N = 2) and doing general investigation (e.g. searching for body parts of a victim) (N = 2) where the agents are also present. In the Iranian corpus, images depicted various actions (43 out of 58) including judicial ones (N = 32), hospitalization (N = 4), crime (N = 3) and other crime-related actions (N = 5); one image depicted both crime and judicial actions together (cf. invented images). In the depiction of judicial actions, the agent is often absent and such actions are implied through objects and/or settings. For instance, arrest is often implied through showing a handcuff on the person’s hand. Crime is implied agentless and hospitalization includes agents in a few cases. Thus, the action is agentless and only the patient (here, the criminal) is shown, which again implies the focus is respectively on criminals and the action rather than on the agents. Another depicted action including agents is protesting.

Perspective. Perspective, in terms of distance, anchor and angle, was more varied in Iranian than in Dutch images. In the Dutch data, there is a tendency to depict actors from an eye-level angle (N = 16), front and oblique front anchor (N = 14) and very close (N = 12) distance. It must be noticed that such perspectives in Dutch news images are almost always used to represent victims; thus, the dominance of victims leads to dominance of this pattern in the Dutch corpus. Criminals are depicted from the front, at eye level, one from close personal and the other one from public distance. Other social actors and officials are often depicted from eye-level but at different (incl. mixed) anchors and distances; when the focus is on depicting emotion, closer distance with other actors (i.e. second victims) is observed (N = 2). In the Iranian corpus, there is a tendency to depict actors also from an eye-level angle (N = 39) and/or front and front oblique anchor (N = 43) and from personal (N = 24) or social distance (N = 20). In Iranian images, victims are often depicted from eye-level (N = 6), front and front oblique (N = 9) and from varying (relatively close) distances; criminals are often depicted at eye-level (N = 27) from front or front oblique (N = 25) and from far personal (N = 10) and close social distance (N = 10) although back and oblique back are also considerably used (N = 11); Officials are also observed often from eye-level (N = 8), front and front oblique (N = 9) and different distances varying from intimate to impersonal.

Degree of realism. In terms of actors, Dutch images showed more realistic and detailed portraits of the victims and more modified ones when depicting the criminals: criminals were depicted with a bar on their eyes in order to remain anonymized. In terms of setting, Dutch images often use de-contextualized depictions of victims but more contextualized depictions of criminals, officials and other social actors. Overall, the Dutch images showed 20 photographs and 5 images which show geographical area of crime location on a map. Among the photographs, only 5 showed realistic images; others (N = 20) were modified for their color saturation, setting, actors, etc. Almost half of the images (13 out of 25) were categorized as offering deep depictions.

The Iranian corpus depicted real actors in almost all of the images (N = 52); one image depicted a made-up character and in 2 cases, both real and made-up actors are observed (cf. invented images). Most of these images depicted actors with naturalistic posture (N = 31) and in fewer the actors were posed (N = 17); in 3 cases, images offered mixed depictions. Whereas some of the pictures included identifiable actors (N = 20), others depicted actors which couldn’t be identified (N = 16), were manipulated (N = 10) or a combination of these (N = 7). In these images, victims, officials and other actors are often identifiable; criminals are often not identifiable because the anchor of the picture is behind the criminal or because their face is either covered by their hands or a bar or because their image or face is blurred; in a few images (N = 6), criminals are identifiable.

Iranian images often contextualize actors in settings (N = 36) and in some cases, either no setting is included or the setting is deleted (N = 20); inclusion or exclusion of the setting occurs in images with different actors. The inclusion or exclusion of the setting is often the result of a naturalistic depiction (N = 46), although in some cases the setting is manipulated (N = 7) or made-up (N = 3). In the Iranian corpus, most of the images were photographs (N = 53), while 5 were invented ones. Among the photographs, most were realistic (N = 41), although use of non-realistic images is also considerable (N = 17).