ABSTRACT

This paper focuses on how opera rehearsal participants use depictions to accomplish proposals; they use a locally created scene, comprised of concrete embodiments to represent another physically or temporally distant scene. Whereas earlier work investigating depictions in interaction has mainly focused on demonstrations in pedagogical scenarios, this paper will discuss how depictions serve the ongoing creation, and aesthetic negotiation, of a yet-to-be-artistic product. In simultaneously creating and referencing iterations of this artwork, participants’ depictions are both self-referential, in introversive semiosis, as well as externally referencing prototypes of mundane behaviour, in extroversive semiosis. We argue that the negotiations of the extroversive and introversive references through depiction constitute the artistic labour of creating a performance. Furthermore, we suggest that the iterative nature of rehearsing an artistic piece demonstrates analogies between introversive semiosis and interactional techniques for projection and depiction. Opera is accomplished through dynamic collaborative social processes, techniques for which include the depictions described in this paper.

Introduction

This paper examines depictions that are used to make proposals during scenic opera rehearsals. The purpose of scenic rehearsals is to create and coordinate dramatic action to the opera’s musical score, which has already been separately rehearsed. Performers and a director accomplish this by collaboratively producing concrete embodiments of possible dramatic actions for experimentation and evaluation. These embodiments take the form of depictions: creating one physically proximal scene in interaction in order to represent another physically distant scene (Clark Citation2016). A brief example follows, of how depictions can unfold in these rehearsals. Below, the director (DIR) comments on a movement they have been rehearsing and produces an assessment of what the singer has just done while rehearsing (“backa ut”/backing out). Transcription conventions are found in Appendix.

While verbally proposing, and extolling the virtues of the proposal, the director also physically enacts the motion, providing a precise visual form of the movement she wishes to assess. The depiction element in this case is embodied, with the body showing rather than describing the motion. The voice modality here is concurrently describing the motion, both its shape (“backa ut”/back out) and its usefulness (“very good”). The rehearsal participants are constantly engaged in making proposals, discussing them and experimenting with their implementation through depictions. Earlier work investigating depictions in interaction has mainly focused on reported speech and demonstrations in pedagogical scenarios (e.g. Clark and Gerrig Citation1990; Keevallik Citation2017; Stukenbrock Citation2014), whereas this paper will discuss how depictions serve the ongoing creation and aesthetic negotiation of a yet-to-be-artistic product. In simultaneously creating and referencing iterations of this artwork, participants’ depictions are both self-referential, in introversive semiosis, as well as externally referencing prototypes of mundane behaviour, in extroversive semiosis (Jakobson Citation1971) (see below).

We argue that the negotiations of the extroversive and introversive references through depiction constitute the artistic labour of rehearsing and creating a performance. The proposal depictions make hypothetical, newly created aesthetic options visually available and physically embodied for negotiation in relation to the performance as a whole. The paper thus examines how participants organize the practicalities of artistic labour through the use of depictions: specifically, how do depictions propose dramatic action, and how do participants manage the iterative nature of rehearsing?

Social and interactional perspectives on opera and creativity

Prior work analysing the interactions in theatrical rehearsals has not yet systematically investigated the role of depictions in rehearsals. However, extroversive reference to prototypes of mundane behaviour has been implicitly targeted in several works. Lefebvre (Citation2018) has examined how actors and the director draw on everyday conversational knowledge to embody text, by applying naturalistic use of gaze and pauses. In examining the longitudinal process of bringing a script to life, both Norrthon (Citation2019) and Hazel (Citation2018) have shown the iterative process by which participants engage in complex coordination of utterances, objects, and embodiment to produce scenes which otherwise occur quite naturally in everyday interaction, such as utterance overlap or serving cake. Other studies have examined how performers organize the rehearsal space and coordinate their bodies into preparation for undertaking rehearsal of a scene (Schmidt Citation2018), and further how the work done in rehearsal is later evaluated (Hazel Citation2015). This work has so far targeted naturalistic theatre, and theatre across art styles has many differences from the art form of opera. Opera is often conceived of in terms of “excess and transgression” (Atkinson Citation2006, 187), and as breaking with naturalistic patterns of behaviour, to instead tell stories in extreme and exaggerated ways – not the least with bombastic song and dramatic music.

As the work on theatre above shows, arts come into being in social contexts. In his ethnographic study of opera companies, Atkinson (Citation2006) stressed the mundane and social organization involved in the work of creating an opera performance, in contrast to the extravagant art form that opera is. The extravagancies, and the “operatic magic” as Atkinson terms it, are made possible precisely due to the disciplined routines and embodied labour of rehearsals in the rehearsal workplace. Creativity is inherently social; Due (Citation2016) stressed the embodied aspect of creativity in workplace meetings, demonstrating how new ideas were co-created with the aid of multimodal resources, building on participants’ prior actions in proposal sequences. In this paper we will discuss the semiotic features of this distributed cognition of human creativity.

Depictions: communication by showing

Depictions, or versions of the concept, have been given multiple names, including some types of reported speech (Holt and Clift Citation2007), polyphony (Bahktin Citation1981), shifts in authorship and footing (Goffman Citation1981), reenactments (Sidnell Citation2006), bodily quotes (Keevallik Citation2010), and others. The terms “animation” (Cantarutti Citation2020) and “depiction” (Clark Citation2016) are the most neutral with respect to temporality (is the represented event past or present or future), realism (is it imaginary or reflecting something that happened), and interactional resources (what resources such as voice, body and language, are involved in the depictions). Such neutrality is important for our analysis, given that the majority of work to date has focused on verbal (e.g. Holt and Clift Citation2007; Niemelä Citation2010), past/real-event (e.g. Goodwin Citation1982, Citation1990) depictions, whereas participants in our data use depictions with a wide variety of multimodal practices, temporal referents, and realistic and imaginary elements. We use depiction, rather than animation, solely because the former has been more widely used so far.

In staging theory (Clark Citation2016), depictions are performances that are taken, by local interlocutors, to represent an action or event occurred at some other time and/or place (real or imaginary). Clark distinguishes depictions from indexes (indexical signification as in pointing) and descriptions (symbolic signification as in language).

Although some theories treat social life as performative generally (e.g. Austin Citation1962), Clark focuses on a particular type of performance wherein participants treat each other as creating, referencing, and illustrating a distal scene that is displaced from the current interactional context. The local action is “split” when depicting, as the participants simultaneously animate a scene that is not treated as occurring in the here-and-now (e.g. how a character moves), as well as doing action in the here-and-now (e.g. proposing). Additionally, other interlocutors may be positioned in different ways in relation to depictions, for example, as recipients, as “stage managers” who organize the participants and resources.

Depictions and referentiality

The concept of depictions builds on the idea of iconicity as elaborated by Peirce (Citation1955). In the case of iconicity, the referent of the sign shares similar features with the sign itself – an icon represents something by virtue of being like that which it represents. Iconicity, then, necessitates a referent that the sign mimics. This mimesis, as it occurs in actual interactional use, has been argued not to necessarily be literal, but rather to analyse and highlight relevant features of some referent for local action (Streeck Citation2008). Such an interactionally situated mechanism better describes both the diversity of iconic forms in our data, as well as better allows for depictions of the hypothetical and prototypical.

An additional feature of the depictions in our data is that they are not only referring to the imperceivable prototypes of mundane behaviour, but also to itself, e.g. the developing performance as perceived by the participants. Jakobson (Citation1971) developed Peirce’s model of the sign so that, in addition to Peirce’s iconicity, indexicality and symbolicity, a fourth sign relationship was coined, which he called connotative signs. This sign relationship is characterized by a lack of external referent (which would be extroversive semiosis). Instead, introversive semiosis operates by internal reference. According to Jakobson, this kind of sign relationship is typical of music and abstract visual art, but it can also operate in other kinds of media as well and alongside extroversive semiosis (for instance in poetry). Agawu (Citation1991) drew on the analogy of syntax to explain introversive semiosis in music, showing how musical phrases can create internal references and structures that mutually inform each other, such as how the establishment of a musical key informs our understanding of subsequent notes. This “utterance”-internal structuring, which informs expectations for recipients as the utterance emerges (Auer Citation2009), applies in interaction more generally, for example with activities unfolding, and as we will show, is a useful explanation of the activity of creating an artistic performance. Note that theories of semiosis do not follow the same epistemological framework as interactional research. Traditional semiotics works with ethically applied categorizations of language and action, whereas the key interest for interactional studies is to uncover participants’ own methods for organizing their activities and making sense of available resources as meaningful – that is, how a gesture or a word contribute to meaning and sense in “this” specific moment. In combining the terminology of semiotics with interactional methodology, we aim to show how participants treat meaning as relevant for accomplishing their activities (see also Goodwin Citation2007), and how the temporal and artistic concerns of participants come to reflect orientations that are analogous to introversive and extroversive semiosis. In this way, we aim to build a terminological bridge between the disciplines, while grounding the analysis in participant action (see Methods).

Depictions in interactional research

Some research has analysed the occurrence of depictions in everyday human activities. This has primarily been done in the field of multimodal interaction analysis, where depictions have been most extensively analysed in the form of reported speech (e.g. Holt and Clift Citation2007), depictive gestures (Streeck Citation2008, Citation2009) and reenactments (Sidnell Citation2006). Multimodal interaction analysis prioritizes the examination of members’ practices for achieving local actions (in our case, below, achieving a proposal). The examination of actual, situated occurrences of multimodal depictions in interaction has overwhelmingly been in teaching contexts (though there are exceptions such as Due and Lange Citation2020 who demonstrates depictions body parts with other body parts in video mediated physiotherapy consultations; and Due Citation2016 for depictive gestures during business meetings) Termed “demonstrations,” these depictions are used to correct and coach behaviour (Evans and Reynolds Citation2016), to model how other participants should configure their bodies (Nishizaka Citation2017), to highlight errors and provide alternatives (Keevallik Citation2010, Citation2017), to provide referents for imaginary practice (Stukenbrock Citation2012), and to model how an expert would approach the task with their professional vision (Goodwin Citation1994). This paper will provide an analysis of how depictions can be used in a non-teaching context, for the purpose of proposing options and creating art. As the participants work through the libretto in rehearsal, they experiment with and decide how to position themselves. This procedure is called “blocking” (see also Hazel Citation2018). Blocking is a multiparty engagement of all performers who will be present at that at that moment in the libretto.

The suggestions for how to block can be termed proposals. The literature on proposals in multimodal interaction analysis began with telephone and verbal-only data (e.g. Davidson Citation1984), and focused on ways for managing rejection, accounts (Houtkoop-Steenstra Citation1987). More recently, studies have examined the interactional management of rights to propose (Stevanovic Citation2015), as well as how opportunities to propose can be provided (e.g. Weiste Citation2020). Multimodal analysis of multiparty proposing has so far been restricted to mediated interaction, such as staff meetings (Asmuß and Oshima Citation2012; Nissi Citation2015) and facilitating civic engagement (e.g. Mondada Citation2015), where a chairperson organizes proposals and their discussion. One non-mediated exception is Stivers and Sidnell’s (Citation2016) study of proposals in children’s play, wherein body positioning, along with other multimodal resources, was used to mark a proposal as disjunctive with the prior activity.

Much as Stevanovic (Citation2015) forewarned concerning the temporality of proposals, the proposals in the opera rehearsals do not divide neatly between proximal and distal (or remote, Lindström Citation2017). Proposals in theatrical rehearsals concern both the proximal work of establishing a current iteration (Hazel Citation2018) of this particular section of the opera and an eventual iteration (what will be attempted in the final performance), as well as the (re)indexing of who has rights to make, evaluate, build on, and accept the proposals (Stevanovic Citation2015, 201; “deontics”). Accepting a proposal at any given moment also does not entail its relative permanence (as with writing down proposals in drafting, Asmuß and Oshima Citation2012; Mondada Citation2015; Nissi Citation2015), but rather its acceptability for progressing the iterations of the eventual performance piece. This paper thus also contributes to the literature on proposals, and rehearsal-based ones in particular, by demonstrating how the practice of depicting helps participants accomplish this dual local-distal action.

This paper aims to contribute to this literature in two ways. First, we will detail the sequential process of using multimodal depictions for creating and rehearsing a performance, and accomplishing proposals. Second, we will demonstrate how depictions can accomplish artistic labour and make hypothetical scenarios available for co-participation. We will thereby show how aesthetics are socially accomplished and negotiated through introversive and extroversive semiosis.

Method

We analyse a corpus of video recordings (20 h) of professional opera rehearsals using multimodal interaction analysis (Broth and Keevallik Citation2020). This method involves using displayed participant orientations as the basis for understanding how participants organize their actions with respect to co-participants and interactional activities. As we aim to show how participants procedurally manage and accomplish depictions, analysing the sequence of talk provides an emic perspective on how participants make their actions mutually intelligible as depictions and as proposals. Similarly, the analytic text will reveal how introversive and extroversive semiosis are members’ concerns, rather than solely analyst-applied labels, by demonstrating the systematicity in the methods that participants themselves use when making semiosis concepts relevant. This is not to say that participants explicitly label their concerns as semiosis of one kind or another, but that they systematically make relevant the nature of the meaning they are actively creating in rehearsal work, and the relationship between local action (sorting out the current idea) and other available meanings from culture, the opera world, and prior rehearsal events. The transcriptions below follow Jefferson’s (Citation2004) conventions for representing utterances and Mondada’s (Citation2018) conventions for representing embodiment (see Appendix), with additional notation for music (♪bracketed with♪), and libretto lines (libretto lines italicized).

Fieldwork was carried out during the entire rehearsal period of an opera production at a Swedish opera house. Video recordings of the scenic rehearsals in a rehearsal space (not the eventual performance stage) were made. Although a multitude of professions are involved in an opera production (such as conductor, choir, designers and more) the participants of the interactions in focus of the present study were director, assistant director and soloist singer performers. Languages spoken in the data are Swedish and English, and the libretto of the performance is in Italian. Participants gave informed consent for video recording and research.

Even though the director is leading the work, and continuously communicates her artistic vision to the group, both the director and the performers present proposals. The scenic opera rehearsal is a highly collaborative environment where everybody participates in creation. The cases below were selected as the best concise examples of the relevant points for each subsection of analysis.

Analysis

Below, we focus on two elements of depictions in opera rehearsals: first, how participants accomplish depictions in the course of social interaction and what actions are involved; and second, how participants orient to the extroversive and introversive semiosis inherent in their work, through managing reference to both other productions and artworks, and to current and past iterations of any given section of the opera. We introduce these components incrementally, although they are present in all extracts.

Multimodal lamination of resources to create depictions

We will first focus on demonstrating the way the participants accomplish depicting and proposing with multimodal resources. Proposal depictions are both experimental embodied attempts at blocking part of the opera as well as proposals – a statement of how a section could be blocked, for (dis)approval and modification by the co-participants. Proposal depictions are essentially acting, that is, not qualitatively distinguishable from what the performers are doing on stage as the same multimodal resources are used to do both. Thus, in terms of referentiality, on-stage/performance depictions and rehearsal depictions share the same referents (see section on depictions above). However, a feature of the proposal depictions is that they may be overlaid with a stance towards themselves as such. This is a characteristic feature of certain theatre traditions such as Bertold Brecht’s epic theatre and “alienated method of acting,” where the actors distance themselves from their characters (Steer Citation1968), but it is also a more general feature of how depictions may work in mundane everyday interaction, as evidenced by how participants through co-animations may affiliate with an affective stance indexed by an initial animation (Cantarutti Citation2020). The proposal depictions draw on mundane social behaviour (see Lefebvre Citation2018), such as how emotions or relationships look when enacted, to create versions of the opera scenes. As such, the proposal depictions are symbolical icons (Peirce Citation1955) and engage in extroversive semiosis (Jakobson Citation1971). They also engage in introversive semiosis, by treating the depiction as an iteration of the eventual performance, but we will return to this below.

Proposal depictions involve a lamination of multimodal resources including bodily movement and position, voice, the environment, quotation from the libretto, use of the musical score, and use of other parts of the base scene (including other participants) as props. These components are sometimes additionally laminated with descriptive language belonging to the proximal scene (see Extracts 2–5). All resources are organized to coordinate the involvement of co-participants as particular roles, such as audience/recipient, prop, or co-depictor (Clark Citation2016). For example, in this extract the baritone soloist (BAR) has proposed that he can lie down next to the other soloist, a soprano (SOP) while singing, and the director (DIR) has asked him to show her what that looks like. The spatial configuration of the participants already resembles a theatre stage, with the soloists onstage and the director opposite, as an audience; this spatial configuration affords an easy transition into a depiction. In this scene, BAR’s character mourns as his daughter (SOP) dies. BAR begins to experiment with (and suggest) what physical actions can accompany this portion of the libretto, which develops from a verbal proposal (lines 2–7) into a depiction (lines 5–18) of possible blocking for the scene. SOP participates by jointly enacting the depiction, while DIR participates as a recipient ().

BAR projects moving into the proposal sequence with a short depiction that establishes the portion of the libretto to be discussed by singing “non morir” and gesturing like his character. The projection develops further by indexing, verbally, potential embodied practices that could occur in the scene (lines 2–7), while using his body to project the upcoming touching and lifting of SOP (lines 2–7). From a multimodal interaction analytic perspective, such “location-indexing” depictions thus act as “pre”s, actions that establish intersubjectivity and project a longer upcoming turn (Terasaki Citation2004). With respect to semiosis, specifically Agawu’s (Citation1991) terminology, these depictions act as “beginnings,” establishing a point from which introversive semiosis can anchor itself and inform participant expectations. The location-indexing depiction “begins” (i.e. informs expectations about) both a referent within the libretto (“non morir”), as well as an iteration of this portion of the artistic performance piece. The participants even explicitly orient to the iterative nature of the process by projecting that the upcoming proposal is based on a temporally earlier thought (“det var där jag tänkte”/that’s where I thought, line 7). In order for participants to make sense of the proposal, the speaker must situate the proposal in both the temporal unfolding of the rehearsal process (this iteration proposed at this time), and in the opera’s libretto.

Bit by bit, BAR adds further multimodal resources to the depiction, by getting his body into position (line 2), trying to lift SOP (lines 5, 7), and finally adding a sung version of the libretto (line 7). Through these multiple projections (see also Schmidt Citation2018, on projecting and preparing for the opening of a rehearsed section), BAR both frames his movements as depicting, and forewarns SOP of the upcoming touch on her body. BAR’s depiction on line 8 is not reproducing a perceptible object (indeed, all depictions depart from precise reproduction, Streeck Citation2008). Rather, it is referencing a prototype of a specific type of human behaviour, stemming from a cultural repertoire of such (see Lefebvre Citation2018, for a gaze-based example of drawing on mundane knowledge of behaviour). For example, this scene requires a representation of a father mourning a dying daughter (extroversive semiosis) that is appropriate for this particular opera production (introversive semiosis). The artistic labour consists in BAR inventing this behaviour in real-time, simultaneously to proposing that it should occur in the scene. BAR draws on expectations for a father, such as how a father should touch or hold a daughter, how they should react to death, and so forth, and previous iterations of the current performance.

The artistic labour carried out by BAR in the depiction on line 08 invites collaboration from his co-participants. DIR’s comment, “mm” (line 3), passes an opportunity to take her own turn, giving BAR a longer opportunity to continue his depiction, analogous to storytelling (C. Goodwin Citation1986), which (re)positions her as the audience/recipient for the depiction. Her watching the soloists, while spatially distanced from them, and withholding of much verbal work (lines 8–17), continually aligns her as the recipient, and permits time for BAR and SOP to attempt the blocking. SOP is first positioned as a prop – an object which BAR can lift. SOP responds as her (dying) character would: as a passive recipient. However, when BAR’s “skips ahead” and fast-forwards the scene ahead (quickly reciting his text, line 13), he goes precisely to where SOP can participate more actively and try out her sung portions in this bodily configuration. BAR thus repositions SOP as a more active co-depictor, which allows SOP to validate whether the current depiction physically “works” for her in the scene – whether the bodily positions permit her own contributions to the scene. Such co-participation can also be seen as a temporary endorsement of the depiction, in accepting the terms of the depiction that have been set up (C. Goodwin Citation2007) and co-implementing, however briefly, the aesthetics of the proposed blocking (Stivers Citation2008).

BAR further acts as a “stage manager” (Clark Citation2016) by switching footing (Goffman Citation1981) towards the end of the extract, back into the here-and-now of the rehearsal. He accounts for his embodied motions using descriptive language, “prova lägga ner” (line 18), in overlap with SOP’s continued singing (see Stukenbrock Citation2012 for a similar division of multimodal labour for managing proximal and distal scenes). In verbalizing an utterance that is not part of the libretto, in a non-sung voice, he does not interjacently overlap SOP’s sung contribution, as they are in separate scenes. This distribution of modalities separates the depiction itself from the metacommentary that locates and accounts for elements of the depiction.

The proposal nature of the depiction is marked by treating the actions as experimental, for eventual comment from others (the director, for instance, withholds commentary in the extract shown, commentary from all participants is given much later on). The depiction is marked as an “initial” attempt, for instance with accounting for his motions with “prova lägga ner” (line 19, try to lay down), and claims not to know how to move (line 7). BAR also thereby projects the need to update, practice, and (as eventually emerges in this case) change the blocking to a more suitable version. In situating the current depiction as temporary, the participants make space for future iterations. They make sense of the depiction as one iteration to be made meaningful later, as well as presently. In short, participants not only treat mentions of location in the libretto as introversive “beginnings” (Agawu Citation1991), but they can also organize proposal depictions as a whole as iterations for which later introversive semiosis may be relevant. We now turn to examining how the participants orient to introversive semiosis in depictions.

Orienting to introversive semiosis in depictions

The relevance of introversive semiosis is clearest when the participants refer back to prior iterations in the rehearsal process and make them relevant for ongoing proposal depictions. In these situations, the participants connect the piece into a temporal whole, where the components (rehearsals) become relevant for making meaning and accounting for ongoing action (current proposals). This conceptualization of introversive semiosis differs from traditional semiotics, where the internal references can be thought of as pre-established by the existence of the whole artistic piece, such as a piece of music. However, it also shows how the lived temporality of meaning making changes the way introversive reference may be experienced. As participants listen to music (especially the first time), introversive reference is about projection and expectation, as well as recalling prior gestures or movements. We argue the rehearsals function in the same way, and that projection, expectation, recalling events, and establishing intersubjectivity are analogous to introversive semiosis.

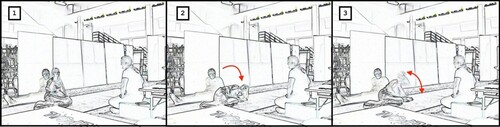

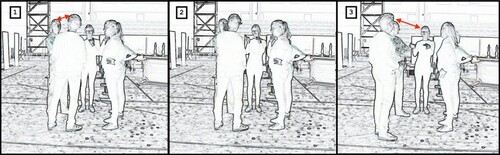

Below, BAR proposes a way to move his body and orient to another performer. SOP (not the performer in question) comments on the similarity of the action to a movement BAR did to her (SOP) yesterday in rehearsing a related section of the scene. SOP’s comment is minimally acknowledged by DIR (line 9) and BAR (line 10), but BAR continues talking and keeps addressing DIR by means of gaze. Once BAR is finished with his proposal (line 17), SOP is given the space to elaborate on her contribution ().

Figure 2. Baritone gazes at another soloist while depicting gazing at a ghost (1,2). Soprano starts to speak but is not attended (2). Soprano restarts her comment (3), that Baritone also did such a gaze in a previous scene.

BAR opens by indexing where in the libretto his depiction pertains to (lines 2–7). He projects a proposal (lines 6–7, see Stevanovic Citation2015), but SOP begins to comment on the topic before the content of the proposal can occur (line 8). SOP’s comment gets a minimal acknowledgement from BAR; he immediately returns to the distal scene by gazing away from DIR and switching footing into speaking (“jag måste bryta den här rösten I huvudet”/I have to stop this voice in my head, line 11) and gesturing as his character. It is only once BAR concludes his depiction that SOP restarts her contribution. SOP’s comment turns out to be an endorsement, and it is now attended.

SOP’s comment, though constrained until the proposal depiction had been accomplished, does important introversive semiosis work. Both BAR and SOP orient to the temporal situation of this proposal depiction; for BAR, he suggests that the current action had been thought about at some prior point (line 7), while for SOP, she orients to the way the depicted action resembles the way BAR acted in earlier iteration of the scene, with her (“de gjorde du på mej igår”/you did that to me yesterday, line 8). Such an observation demonstrates the introversive semiosis-based sense making in which the participants are engaged. SOP’s observation not only endorses BAR’s proposal as recognizable, and as appropriate, but also as an iteration of blocking within the rehearsal process. A method of performing “madness” that had arisen earlier in a different section now becomes relevant for the current discussion and scene. SOP’s comment shows that proposals are evaluable based on their coherency for the art piece, and it is this coherency that also invokes introversive reference. BAR enacting such a motion, one that resembles how he acted towards SOP previously, creates a coherent sense of in what way BAR’s character is being “mad,” and links the two occasions within the rehearsals. The participants orient to the importance of portraying the characters in a way that is meaningful and sensible, within the framework of their production.

Invoking introversive and extroversive semiosis from other productions

In creating the current opera performance, the participants use not only the current introversive semiosis as a resource, but also the aesthetics of other performances that serves as models on which acting in the current performance can be based. In Extract 4 below, the director is using extroversive and introversive semiosis to refer to another production, namely Shakespeare’s Hamlet, in alternating between depicting the characters of Hamlet and Gertrude (lines 1–5 and 6–12). This is deployed in order to illustrate how BAR and SOP can act in a particular scene in the current opera. DIR depicts Hamlet’s madness, highlighting with her body (Streeck Citation2008) the way gaze can address thin air, rather than a person, and thus display insanity ().

In the midst of her depicting (line 7), DIR addresses SOP by means of gaze. When doing so, SOP begins shaking her head and says “de e ingen där”/there is no one there, while frowning, in overlap with the end of DIR’s utterance (line 7), in an early onset displaying agreement (Pomerantz Citation1984) with the model DIR depicts. Depictions from the other production here serve as source material for producing an aesthetic the participants can emulate. It is both an account for the appropriateness of the proposed version of the scene, as well as a means to establish intersubjectivity on what the version should look like. The co-participation in the proposal depiction by SOP is thus bound up with accomplishing the artistic labour: proposed versions of scenes are done with reference to intersubjectively available concepts (in this case, how speaking to thin air looks crazy) and by highlighting relevant details.

Nonserious depictions as a way to establish aesthetic choices

Finally, as important as it is to establish what the aesthetic choices for blocking should be, it is equally important to establish what they should not be. Participants therefore sometimes depict dramatic action that they do not intend to do in the performance, in order to establish the aesthetic choices of the current work. In these moments, we see the bipartite nature of introversive and extroversive semiosis. The former informs what aesthetics the participants maintain coherency with, while the latter informs on the myriad of options available. Our final example shows how aesthetics can be negotiated by means of depicting an action that ostensibly does not belong within the aesthetics of the current piece. Extract 5 below occurs a bit later in time than Extract 2 above. DIR, SOP and BAR are discussing different ways to die in an opera performance and the director has mentioned a particular production where blood was pumped out of the dress of a performer while she was singing her final aria. Everybody agreed that this was a “beautiful” portrayal of a death, an agreement that establishes a beginning of introversive semiosis for the portrayal of death in the current production. However, SOP contrasts this realistic portrayal of death with a humorous depiction of how opera singers sometimes seem to die and then pause dying in order to sing. She frames this as “the worst thing about opera” (lines 8–9), and thus as an inverted proposal, a depiction of what she does not wish to do ().

The depiction (lines 9–13) consists of somebody who is dying and keeps falling towards the floor, but at the last minute, pushes themself up again. She repeats this movement cycle three times, and simultaneously her voice alternates between the distal scene portraying her character explaining what she is doing (“nu dör ja nu dör ja”/Now I’m dying, “nej ja ska bara sjunga en- lite saker till”/No I’ll just sing a little bit more) and the proximal scene providing descriptive language to the distal scene (“de e ju liksom de här”/it’s kind of like this, “å så man ba”/so one just, “å så kom det en aria”/and now comes an aria). In performing her depiction, SOP reinforces her agreement on the more realistic aesthetics of dying as evoked by the director just prior – it provides an account that aligns with the necessity of a subtle aesthetic of dying. DIR and BAR smile, thereby treating SOP’s depiction as nonserious (lines 12–17). DIR then replies by implying that this is not what they will do in the current opera, but that they have two options for portraying death in a more suitable matter: either “sitta å pumpa faktiskt blod”/sit and pump actual blood (line 18–22) or “å ligga”/“to lie down” (line 23), to which SOP affiliates (line 25). This illustrates how both extroversive and introversive semiosis is at play when making aesthetic choices. Further, this shows how introversive semiosis is relevant for the interactants. Although SOP’s depiction on lines 9–13 is referencing someone dying, it does not do so in a manner that is suitable for this performance. In making relevant the internal coherency of the piece, the participants draw on introversive semiosis. The depiction of death works under one aesthetic framework (“other” operas), but not this one. The non-serious depiction (an extreme case formulation, Pomerantz Citation1986) allows SOP and DIR to distinguish between these two scenes, and align on which fits with this opera.

The aesthetics of the performance are made co-present in the rehearsal, as an available “object” that can be co-participated with, negotiated, and evaluated. The depictions refer not only to an eventual performance, but also to other iterations of the art piece so far, drawing on introversive semiosis to make sense of the depictions within the rehearsals process and aesthetics of the piece. Through these depictions, these opportunities for experiment and iteration, the artists accomplish the artistic labour of opera rehearsing.

Discussion

In this paper, we investigated how depictions are interactionally situated in a collaborative, creative setting. We showed how participants propose how the dramatic action at that point should unfold, using tentative framing such as “I think” or “try this” to establish the proposal nature of the depiction. The depiction itself makes the interpersonal, spatial, musical, and textual resources immediately available for collaboration and aesthetic negotiation.

The tension between solving local concerns (how to solve positioning on the stage, how the performer’s voices can manage certain postures) and orienting to the eventual performance of the libretto (performing character, how it ought to look, the aesthetics) constitutes a lived, developing semiosis. The depictions in these opera rehearsals demonstrate a degree of both introversive and extroversive semiosis. The extroversive elements involve drawing on prototypical and conceptual references to mundane behaviour (how a father holds their daughter, how a body displays strain, etc.) (see also Lefebvre Citation2018). Introversive semiosis is accomplished by situating the depiction in a particular scene, at a particular point of rehearsal (see Extract 1), and also distinguishing it from other potential (see Extract 5) or actual proposed ways of performing. As such, the aesthetics of the performance as a whole are made relevant, and participants orient to keeping that aesthetics coherent (see Extract 4). Conceived this way, introversive semiosis is analogous to the inextricably situated nature of interaction (Suchman Citation1987): meaning is made of actions as they emerge, sequentially orienting both retrospectively and prospective in a web of relevancies and contingencies.

As we have argued, this is a specific interpretation and situation of introversive and extroversive semiosis. We have used semiotic terminology as way of describing how the participants’ organization of their artistic labour systematically orients to the temporal nature of rehearsing (how a depiction fits with prior iterations), to the coherency of the eventual artwork (how choices fit in with prior choices and the developing aesthetics of the performance), and to the way their performance may evoke broader ideas of how the characters should look (being a father, being mad). While the participants would obviously not use this terminology themselves (but neither would they use other interactional terminology, e.g. adjacency pair), their orientations to these issues show how semiotic ideas may be relevant for local action. We hope that this overlap – the point where concepts of semiosis can be seen in situated interaction – can be another zone where interactional studies and semiotics can have mutual discourse. Specific to the findings of this paper, we expect such overlap would focus on longer term activities where temporal relations may become relevant.

We have thus shown how theories of semiosis is not only a matter for art or media, but for participants doing action in an activity with both local and distal considerations. This suggests that particularly the concept of introversive semiosis may be useful for considering how participants organize long term activities. Multimodal interaction analytic research has focused more on immediate sequences than temporally extended activities (see Robinson Citation2013; Pekarek Doehler, Wagner, and González-Martínez Citation2018 for excellent exceptions), as participant orientation to longer term elements can be difficult to demonstrate in recordings. Introversive semiosis provides a framework for examining how orientations to the overall activity are situated in local action, and vice versa, making meaning (and sense) out of iterative changes, temporal displacement, and potentially cultural reference (Linell Citation2009). Such semiotic practices may be less salient in activities that do not have long(er) term implications or contingencies – as compared to an opera rehearsal, where the reason for meeting and working is ultimately to create an art piece that must be presented (Hazel Citation2018) – but where participants make such longitudinal reference relevant, the concept may be useful.

The in situ negotiations between the extroversive semiosis and introversive semiosis, through depictions, are what constitute the artistic labour of creating an opera performance. In that way, human creativity is collaboration mitigated through interaction. As Atkinson (Citation2006) suggests, the magic of opera is created in the mundane nature of rehearsal.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Vetenskapsrådet [2016-00827]. Thank you very much indeed to Leelo Keevallik, Angelika Linke, and two anonymous reviewers for their extremely helpful comments and insights. Thank you to the participants in the data, without whose wonderful help this work would not be possible.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Agnes Löfgren

Agnes Löfgren is a PhD student in Interactional linguistics with a background in Speech and Language Pathology, French and Linguistics. She is employed within the Non-lexical vocalizations project that investigates the language/body distinction. Her contribution to the project concerns interaction in artistic contexts, focusing on the relationship between aesthetic and linguistic expression.

Emily Hofstetter

Emily Hofstetter (PhD) is a research fellow in Interactional linguistics in the Non-lexical vocalizations project. She uses multimodal interaction analysis to study micro-level details of social interaction, particularly with recordings of sport and play. Her previous work has examined several institutional settings, such as neonatal clinics, visiting a local politician, and helping colleagues work in safer environments. She has also worked to apply this research in communication training, using the CARM methodology for presenting and discussing interactional research results.

References

- Agawu, V. Kofi. 1991. Playing with Signs: A Semiotic Interpretation of Classical Music. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Asmuß, Birte, and Sae Oshima. 2012. “Negotiation of Entitlement in Proposal Sequences.” Discourse Studies 14 (1): 67–86.

- Atkinson, Paul. 2006. Everyday Arias: An Operatic Ethnography. Oxford: Rowman Altamira.

- Auer, Peter. 2009. “On-line Syntax: Thoughts on the Temporality of Spoken Language.” Language Sciences 31 (1): 1–13.

- Austin, J. L. 1962. How to Do Things with Words. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Bahktin, Mikhail. 1981. The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays. Edited by Michael Holquist. Translated by Caryl Emerson and Michael Holquist. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Broth, Mathias, and Leelo Keevallik, eds. 2020. Multimodal Interaktionsanalys. Lund: Studentliterattur.

- Cantarutti, Marina. 2020. “The Multimodal and Sequential Design of Co-Animation as a Practice for Association in English Interaction.” Doctoral thesis, University of York, York.

- Clark, Herbert. 2016. “Depicting as a Method of Communication.” Psychological Review 123 (3): 324–347.

- Clark, Herbert, and Richard J. Gerrig. 1990. “Quotations as Demonstrations.” Language 66 (4): 764–805.

- Davidson, Judy. 1984. “Subsequent Versions of Invitations, Offers, Requests, and Proposals Dealing with Potential or Actual Rejection.” In Structures of Social Action: Studies in Conversation Analysis, edited by J. Maxwell Atkinson and John Heritage, 102–128. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Due, Brian Lystgaard. 2016. “Co-Constructed Imagination Space: A Multimodal Analysis of the Interactional Accomplishment of Imagination During Idea-Development Meetings.” CoDesign 14 (3): 153–169. doi:10.1080/15710882.2016.1263668.

- Due, Brian Lystgaard, and Simon Bierring Lange. 2020. “Body Part Highlighting: Exploring Two Types of Embodied Practices in Two Sub-Types of Showing Sequences in Video-Mediated Consultations.” Social Interaction. Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality 3 (3). doi:10.7146/si.v3i3.122250.

- Evans, Bryn, and Edward Reynolds. 2016. “The Organization of Corrective Demonstrations Using Embodied Action in Sports Coaching Feedback: Corrective Demonstrations in Sports Coaching.” Symbolic Interaction 39 (4): 525–556.

- Goffman, Erving. 1981. Forms of Talk. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Goodwin, Marjorie Harness. 1982. “‘Instigating’: Storytelling as Social Process.” American Ethnologist 9 (4): 799–816.

- Goodwin, Charles. 1986. “Between and Within: Alternative Sequential Treatments of Continuers and Assessments.” Human Studies 9 (2): 205–217.

- Goodwin, Marjorie Harness. 1990. “Tactical Uses of Stories: Participation Frameworks Within Girls’ and Boys’ Disputes.” Discourse Processes 13 (1): 33–71.

- Goodwin, Charles. 1994. “Professional Vision.” American Anthropologist 96 (3): 606–633.

- Goodwin, Charles. 2007. “Participation, Stance and Affect in the Organization of Activities.” Discourse & Society 18 (1): 53–73.

- Hazel, Spencer. 2015. “Acting, Interacting, Enacting” Akademisk kvarter/Academic Quarter 12: 44–64.

- Hazel, Spencer. 2018. “Discovering Interactional Authenticity: Tracking Theatre Practitioners Across Rehearsals.” In Longitudinal Studies on the Organization of Social Interaction, edited by Simona Pekarek Doehler, Johannes Wagner and Esther González-Martínez, 255–283. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Holt, Elizabeth, and Rebecca Clift, eds. 2007. Reporting Talk: Reported Speech in Interaction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Houtkoop-Steenstra, Hanneke. 1987. Establishing Agreement: An Analysis of Proposal-Acceptance Sequences. Dordrecht: Foris Publications.

- Jakobson, Roman. 1971. Language in Relation to Other Communication Systems. Selected Writings II: Word and Language. Paris: Mouton.

- Jefferson, Gail. 2004. “Glossary of Transcript Symbols with an Introduction.” In Conversation Analysis: Studies from the First Generation, edited by Gene H. Lerner, 13–31. Pragmatics & Beyond. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Keevallik, Leelo. 2010. “Bodily Quoting in Dance Correction.” Research on Language & Social Interaction 43 (4): 401–426.

- Keevallik, Leelo. 2017. “Linking Performances: The Temporality of Contrastive Grammar.” In Linking Clauses and Actions in Social Interaction, edited by Ritva Laury, Marja Etelämäki, and Elizabeth Couper-Kuhlen, 54–73. Helsinki: Finnish Literature Society.

- Lefebvre, Augustin. 2018. “Reading and Embodying the Script During the Theatrical Rehearsal.” Language and Dialogue 8 (2): 261–288.

- Lindström, Anna. 2017. “Accepting Remote Proposals.” In Enabling Human Conduct: Studies of Talk-in-Interaction in Honor of Emanuel A. Schegloff, edited by Geoffrey Raymond, Gene H. Lerner, and John Heritage, 125–143. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Linell, Per. 2009. Rethinking Language, Mind, and World Dialogically: Interactional and Contextual Theories of Human Sense-Making. Charlotte, NC: Information Age.

- Mondada, Lorenza. 2015. “The Facilitators’ Task of Formulating Citizens’ Proposals in Political Meetings: Orchestrating Multiple Embodied Orientations to Recipients.” Gesprächsforschung 16: 1–62.

- Mondada, Lorenza. 2018. “Multiple Temporalities of Language and Body in Interaction: Challenges for Transcribing Multimodality.” Research on Language and Social Interaction 51 (1): 85–106.

- Niemelä, Maarit. 2010. “The Reporting Space in Conversational Storytelling: Orchestrating All Semiotic Channels for Taking a Stance.” Journal of Pragmatics 42 (12): 3258–3270.

- Nishizaka, Aug. 2017. “The Perceived Body and Embodied Vision in Interaction.” Mind, Culture, and Activity 24 (2): 110–128. doi:10.1080/10749039.2017.1296465.

- Nissi, Riikka. 2015. “From Entry Proposals to a Joint Statement: Practices of Shared Text Production in Multiparty Meeting Interaction.” Journal of Pragmatics 79 (April): 1–21.

- Norrthon, Stefan. 2019. “To Stage an Overlap – the Longitudinal, Collaborative and Embodied Process of Staging Eight Lines in a Professional Theatre Rehearsal Process.” Journal of Pragmatics 142: 171–184.

- Peirce, Charles S. 1955. Philosophical Writings of Peirce. New York: Dover Publications.

- Pekarek Doehler, Simona, Johannes Wagner, and Esther González-Martínez, eds. 2018. Longitudinal Studies on the Organization of Social Interaction. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Pomerantz, Anita. 1984. “Agreeing and Disagreeing with Assessments: Some Features of Preferred/Dispreferred Turn Shapes.” In Structures of Social Action: Studies in Conversation Analysis, edited by J. Maxwell Atkinson and John Heritage, 57–101. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Pomerantz, Anita. 1986. “Extreme Case Formulations: A Way of Legitimizing Claims.” Human Studies 9 (2–3): 219–229.

- Robinson, Jeffrey D. 2013. “Overall Structural Organization.” In The Handbook of Conversation Analysis, edited by Jack Sidnell and Tanya Stivers, 257–280. Chichester: Wiley.

- Schmidt, Axel. 2018. “Prefiguring the Future: Projections and Preparations Within Theatrical Rehearsals.” In Time in Embodied Interaction: Synchronicity and Sequentiality of Multimodal Resources, edited by Arnulf Deppermann and Jürgen Streeck, 231–260. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Sidnell, Jack. 2006. “Coordinating Gesture, Talk, and Gaze in Reenactments.” Research on Language and Social Interaction 39 (4): 377–409.

- Steer, W. A. J. 1968. “Brecht’s Epic Theatre: Theory and Practice.” The Modern Language Review 63 (3): 636–649.

- Stevanovic, Melisa. 2015. “Displays of Uncertainty and Proximal Deontic Claims: The Case of Proposal Sequences.” Journal of Pragmatics 78: 84–97.

- Stivers, Tanya. 2008. “Stance, Alignment, and Affiliation During Storytelling: When Nodding Is a Token of Affiliation.” Research on Language and Social Interaction 41 (1): 31–57.

- Stivers, Tanya, and Jack Sidnell. 2016. “Proposals for Activity Collaboration.” Research on Language and Social Interaction 49 (2): 148–166.

- Streeck, Jurgen. 2008. “Depicting by Gesture.” Gesture 8 (3): 285–301.

- Streeck, Jürgen. 2009. Gesturecraft: The Manu-Facture of Meaning. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Stukenbrock, Anja. 2012. “Imagined Spaces as a Resource in Interaction.” Bulletin VALS-ASLA 96: 141–161.

- Stukenbrock, Anja. 2014. “Take the Words Out of My Mouth: Verbal Instructions as Embodied Practices.” Journal of Pragmatics 65: 80–102.

- Suchman, Lucy A. 1987. Plans and Situated Actions: The Problem of Human-Machine Communication. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Terasaki, Alene K. 2004. “Pre-Announcement Sequences in Conversation.” In Conversation Analysis: Studies from the First Generation, edited by Gene H. Lerner, 171–224. Pragmatics & Beyond. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Weiste, Elina. 2020. “Co-Constructing Desired Activities: Small-Scale Activity Decisions in Occupational Therapy.” In Joint Decision Making in Mental Health: An Interactional Approach, edited by Camilla Lindholm, Melisa Stevanovic, and Elina Weiste, 235–252. The Language of Mental Health. Cham: Springer International.