ABSTRACT

The growth of digital culture has opened up new spaces of engagement where interactive users discuss social issues, including crime. Given crime’s ubiquity in popular culture, cultural criminologists argue that diverse emotional involvement with crime in popular cultural texts, such as social media, provides important insights into how citizens comprehend issues related to crime. Here, an analysis of emotion should be placed into the foreground (Hayward, K., and J. Young. 2004. “Cultural Criminology: Some Notes on the Script.” Theoretical Criminology 8 (3): 259–273). Taking this as a cue to explore these often neglected popular moral and emotional aspects of crime, this article focuses on constructions of popular crime discourses, using citizens’ responses to the Mo Robinson people smuggling case on Facebook as a case study. Applying multimodal critical discourse analysis and a framework for analysing evaluation, we reveal ideological themes through which participants judge crime, perpetrator and victims. Our analysis of the Free Mo Robinson Facebook page demonstrates that although social media has the potential to challenge and shift traditional narratives about crime, it can also perpetuate and amplify ideological narratives of crime control that fail to address the wider socio-political and structural contexts in which crime occurs.

1. Introduction: the Mo Robinson case

In the early hours of 23rd October 2019, the bodies of 39 Vietnamese, 28 men, three boys, and eight women, were found in the trailer of an articulated refrigerator lorry in an industrial park in Grays, Essex in the UK. The trailer had been shipped from the port of Zeebrugge, Belgium, to Purfleet, Essex, UK. Maurice “Mo” Robinson, a 25-year old lorry driver from Craigavon in Northern Ireland, was arrested at the scene shortly after the deceased victims were detected. Robinson had collected the trailer at Purfleet with his lorry cab less than an hour before he discovered the victims had died and he informed the police. Friends and relatives of Robinson protested his innocence and a Facebook page called Free Mo Robinson was created on 24th October 2019, one day after his arrest. Robinson first pleaded guilty at the Old Bailey to conspiring with others to assist illegal immigration between 01st May 2018 and 24th October 2019 and later pleaded guilty to 39 counts of manslaughter in April 2020. Prosecutors alleged that Robinson was part of an international ring of people smugglers and investigations, led by Essex Police and involving police in Belgium, Ireland and Vietnam, led to several other arrests and ongoing prosecutions (BBC News, 25 Nov., Citation2019). The Mo Robinson case has captured a great deal of public and media interest since the initial report of the suspected crime and the subsequent police investigation. Here we seek to explore and understand one form of citizen engagement with this case on social media, and in particular on Facebook. We focus specifically on the Facebook page Free Mo Robinson, created initially in support of Robinson, which includes content from before and after his guilt was established.

The impact of mass media coverage on public attitudes and beliefs regarding crime and deviance is well-documented (Hall et al. Citation1978; Yar Citation2012; Mayr and Machin Citation2012). More recently, the one-directional nature and agenda-setting role of so-called “old” media has been altered by digital communication and social media technologies that have transformed the capacity of ordinary people to engage and intervene in debates about crime events and criminal justice responses (e.g. Powell, Overington, and Hamilton Citation2018). This is because the rise of the internet in general has transformed media “consumers” into “consumer-producers”, which for some has raised the hopes for a re-democratised public sphere (see Papacharissi Citation2015). There has also been a notable digital turn in criminological theory and research, which explores in part the nature of citizen participation on social media in response to crimes (e.g. Stratton, Powell, and Cameron Citation2017). Here the work of cultural criminologists in particular has sought to explore how the internet is changing the socially constructed nature of crime and deviance (e.g. Yar Citation2012).

Media representations of human trafficking are problematic owing to the complexity of the phenomenon. Although men, women and children are trafficked, it is “sex trafficking” that has dominated political and media discourses, as well as popular representations in film and documentaries (Gregoriou and Ras Citation2018). Gregoriou and Ras (Citation2018, 17) note that usually only those who are young and female and who are exploited in the sex trade and moved without their consent are given the label of being “trafficked”. Many other real victims not only do not receive adequate support, but are also criminalised. This understanding and its mediated representations largely ignore structural reasons such as poverty and the demand for cheap labour that causes trafficking in the first place. It also prevents more informed discussion of how the socio-economic and political inequalities framing labour exploitation are produced, maintained and re-produced.

In the UK, migration that is facilitated by human smugglers falls under the general category of illegal immigration. The UK’s National Crime Agency (NCA) firmly associates human smuggling with organised crime (Diba, Papanicolaou, and Antonopoulos Citation2019). According to statistics from 2018, three in five Britons supported the UK Home Office “hostile environment” policy, which makes it difficult for illegal immigrants to stay in the country (Wilson and Kirk Citation2018; quoted in Diba, Papanicolaou, and Antonopoulos Citation2019). Accordingly, law enforcement activity against human trafficking and smuggling typically receives ample discussion in both mainstream and social media. This punitive stance by the British government and some sections of the media can be said to be infused with what has been referred to in criminology as “penal populism” (Newburn Citation1997). Penal populism prioritises public “common-sense” over expert knowledge in criminal justice affairs and is built around the idea that the public or its various representatives should have a strong influence on penal affairs (Pratt Citation2007, 35). As with populism itself, penal populism usually focuses on emotive rather than rational debates, and it employs a “tabloid” rhetorical style of communication that bears simplicity and directness (Canovan Citation1999, 3). Perceptions about crime and penal populism are influenced by both mainstream “old” and “new” media. In the words of Pratt (Citation2007, 4), the media can shape, solidify and direct public opinion about crime and punishment, while “simultaneously reflecting it back as the authentic voice(s) of ordinary people”. At the same time, the technical affordances of social media are conducive to simplifying content, which in turn makes it more prone to common-sensical populist explanations of crime at the expense of more elaborate accounts by experts in criminal justice. As we will see below, at least one of the discourse themes we have identified on the Free Mo Robinson Facebook site bears traces, if not to say clear expressions of a populist punitive sentiment towards the offender, as well as the victims. The comments also demonstrate an abiding preoccupation with the illegality and criminality of trafficking and people smuggling and attribute a significant amount of responsibility to the victims themselves.

The next section will comprise a brief overview of cultural criminology and how it has been applied to the analysis of crime in popular culture. This provides relevant insights to our own multimodal analysis of a sample of Facebook postings on the Free Mo Robinson page, the key findings of which will inform our concluding discussion of the extent to which this digital discourse platform reflects or potentially challenges dominant ideologies about crime and illegal immigration.

2. Crime, popular culture and cultural criminology

Cultural criminology has paid particular attention to the reciprocal relationship between crime and popular culture and the centrality of the media image in that process (Ferrell, Hayward, and Young Citation2008; Fawcett and Kohm Citation2019). It aims not just to explore the role of media in shaping public attitudes, but also to examine closely the “microcircuits of knowledge regarding crime, deviance and the societal reactions to these” (Websdale and Ferrell Citation1999, 349; emphasis original). Building on printed media analysis of crime ideologies (e.g. Hall et al. Citation1978; Cohen and Young Citation1981), cultural criminology has extended its scope of enquiry to the production, negotiation and contestation of crime across a range of media, such as film (Rafter Citation2007), TV dramas (Cavender and Deutsch Citation2007) and the internet (Yar Citation2012; Kennedy Citation2018). This last, emerging subfield of what has been called a “digital criminology” (Stratton, Powell, and Cameron Citation2017) explores the nature of citizen participation on social media in response to crime events (see Powell, Overington, and Hamilton Citation2018; Salter Citation2013). Yar (Citation2012, 207) argues that the internet should not be analysed as just technology, but as “technologically enabled social practices”. In other words, the internet should be seen as part of the social construction of crime and deviance. This puts emphasis on the social part of social media and what citizens do with it.

It is the aim of this article to further extend these analyses of popular representations of crime on the internet, bearing in mind Hayward and Young’s (Citation2004, 264) contention that users’ “various feelings of anger, humiliation, exuberance, excitement, [and] fear” should be placed into the foreground of analysis. The internet, as a system of mediated communication inevitably adds to the circulation of crime-related discourses, images, signs and symbols, which need to be analysed if we want to understand in more detail how crime is imagined and constructed. This is where a combined cultural/popular criminological and multimodal discourse-analytical approach can be instructive. While cultural criminology provides a theoretical framework to interrogate the “diffuse cultural anxieties” (Rafter and Brown Citation2011, 5) and insecurities that are embodied and activated through popular cultural crime texts on the internet, a multimodal discourse approach offers a systematic toolkit for analysing the semiotic modes to express these in greater detail.

3. Methodological framework

In this paper we explore through a social semiotic, multimodal approach how discussion of a crime case on Facebook contributes to its “meaning-making” (Powell, Overington, and Hamilton Citation2018). In order to address our research objectives, we use a set of analytical tools developed in multimodal CDA or MCDA (Machin and Mayr Citation2012; Machin Citation2013). In MCDA, texts are analysed as regards lexical, grammatical and other semiotic choices in order to reveal underlying discourses and ideologies. In other words, we ask here, what do the ways in which the Facebook posts represent participants and actions tell us about popular crime and immigration discourses? How do users align or dis-align with certain ideological discourses about crime, such as “penal populism” and public (punitive) perceptions of immigration and trafficking?

For the analysis of the language in the posts, we employ the Appraisal model (Martin Citation2000; Martin and White Citation2005), which is specifically designed to identify evaluation and provides a systematic account of language resources for expressing emotions and attitudes. In our analysis, we consider the Appraisal category of Judgement. Within the system of Judgement, the two main distinctions are Social Sanction and Social Esteem. Martin (Citation2000, 156) states that “social esteem involves admiration and criticism, typically without legal implications”; “social sanction” on the other hand involves praise and condemnation, often with legal implications’. Given this description, it is perhaps unsurprising that social sanction features heavily in the judgemental language on the Free Mo Robinson Facebook page. The different targets of positive and negative judgement and the divergent use of social sanction and social esteem by a range of comments provide insights into the ideological positions of the commentators. Evaluation and emotion have been observed as an important part of social media engagement and use (Myers Citation2010), both driving and binding “affective communities” (Papacharissi Citation2015, 127). This means that feeds are often powered by statements of opinion, fact, or a blend of both. Papacharissi (Citation2015, 127) notes that online feeds appear to be lacking in coherent rational discussion and consist more of “floods of emotion” and simplified narratives, often with clear polarities of “good” and “evil”, which allow for expression of shared sentiments or outrage. Many of the evaluative comments on the Free Mo Robinson page could be described along these lines. Our aim in this article is therefore to analyse if and how judgemental stance in the Free Mo Robinson Facebook campaign exhibits ideological evaluations of the social actors involved in this case, i.e. the offender(s), the victims, the police and the media.

4. Data and analysis

The data for analysis has been acquired by collecting the main posts from the page’s “admin” – Facebook parlance for the user who administers and oversees a page – and the comments on those posts with the “most relevant” option selected. This is the default option for Facebook posts and is defined by the site as showing “friends’ comments and the most engaging comments first” (neither author is Facebook friends with anyone who has commented on this site). Other options are “newest” and “all comments”. Keeping the default settings in place whilst not being logged in to Facebook provides a data sample of 91 comments from across the lifespan of the page and so includes language from the time of Mo Robinson’s arrest, throughout the initial custody period when he was questioned by police and after he was charged with assisting illegal immigration and 39 counts of manslaughter. Whilst logging in to Facebook or “liking” the page would likely have yielded a larger number of comments, our method of data collection provides a sample that is extensive enough to be representative, whilst also being amenable to close qualitative analysis. The posts and comments discussed are rendered here as they appear on the page with spelling and grammatical errors intact. A thematic analysis was conducted to organise the posts into separate discourse themes.

4.1. Themes: defending and condemning Mo Robinson

Through carrying out a thematic analysis of the posts we can identify comments that defend Mo Robinson and those that are more focused on his condemnation. The theme that received the most postings is the Victims to Blame theme, which is comprised of anti-immigration ideologies reminiscent of those constructed and reinforced across other institutional discourse arenas, such as the mainstream media and right-wing populist politicians (see Wodak Citation2015). While many of the comments in this theme do not concentrate on defending Mo Robinson per se, the very act of focusing blame on the victims themselves reinforces an interpretation of the event in which Robinson’s culpability is diminished. Other comments in this theme focus on national governments and human traffickers and smugglers. We can also discern posts and comments which, at least ostensibly, are not concerned with defending or condemning Robinson and which are instead focused on this incident from a legal perspective. In these posts, references are made to aspects of the case, such as due process and the presumption of innocence. outlines the themes and the number of posts associated with each and the subsequent discussion will analyse the most prominent of these. While the findings presented below may not be all that surprising given the call to “free” Mo Robinson, they reveal and confirm how social media users join in with their affective communities (Papacharissi Citation2015).

Table 1. Themes on Free Mo Robinson page.

4.2. Mo Robinson as unknowing

A dominant theme on this Facebook page, prevalent both before and after the establishment of Mo Robinson’s culpability, was the argument that he was “unknowing”, that is, that he was either not aware that the victims were concealed in the trailer or he was unaware of the potential consequences of this. Mo Robinson as Unknowing is one of two interconnected themes that construct Robinson as innocent or without culpability.

Those arguing that Mo Robinson was ignorant to the extent that he was innocent account for 13 comments and offer four main perspectives. The first perspective is from supporters connected to the transport and haulage industry. The mainstay of these arguments was that Robinson was essentially no more than “just the delivery driver” (C13) (C = comment) and that there is no reason he would have been aware of his cargo because “anything put inside the trailer was put in prior to the vehicle leaving its original destination” (C12). These comments encode a stance of positive social sanction in terms of Robinson’s role. Phrases that invoke positive social sanction, such as “no evidence he had been involved in loading the trailer” (C3), attribute truthfulness to the explanation that supporters assumed Robinson would offer to police and form part of the overall narrative framework of Robinson as not culpable, evident in 59 of the 91 comments in the data set. These comments were made after Robinson was arrested and before he was charged. They demonstrate an assumption of innocence and a willingness to pursue explanations for Robinson’s involvement. However, attributing positive social sanction to Robinson in these comments is essentially hypothetical. These users assume that this is the defence that will be proffered, but we have no evidence that Robinson ever made this claim. The preference to seek affiliation with Robinson may be explained by professional solidarity or may indicate an accommodation of the assumption that the victims bear primary culpability in this case or indeed both. Certainly, those users who identify as members of the haulage profession show disdain for the victims in other comments (see 4.6). The second argument in this theme adopts a rationalisation strategy, arguing that it does not make sense that Mo Robinson would be involved in human trafficking, firstly owing to the risk factor – it is a “huge risk for a young guy to take who clearly loved that truck” (C4) – and secondly because of the potential trauma he would suffer, represented by comments like “hes gotta live with the image of them poor people for the rest of his life” (C10). More disturbing is a focus that views the horror suffered by the victims only in terms of its effect on potential perpetrators (see further 4.3 and 4.6). In terms of Appraisal, a rationalisation strategy is achieved through language that encodes social esteem, particularly the sub-definition of esteem known as “normality” (Martin and White Citation2005). These comments rely on the assumption that it would be abnormal for Robinson to be involved, in this case because it would compromise his affection for his truck – which admittedly may not seem overly rational to observers who do not share the same disproportionate pride in motor vehicles – and his own peace of mind.

The third and fourth perspectives adopted by comments in the Mo Robinson as Unknowing theme employ a strategy of negotiation. These comments do not wholly discount Robinson’s culpability, but instead offer points in mitigation. The third perspective relates to the stage of the investigation after Mo Robinson’s arrest and essentially argues that “arrest is part of the procedure […] he will get out when they find no evidence he had been involved loading the trailer” (C3). Another comment offers a fairly lengthy explanation of the rules by which the police can acquire an extension to keep a suspect in custody and speculates that “it could be that he has valuable info without knowing” (C7). The second use of the negotiation strategy, the fourth perspective taken in this theme, is connected to the “just the delivery driver” (C13) argumentation referred to above, but in this case the argument is that even if Robinson was aware that he was smuggling human beings this still does not make him culpable for the victims’ deaths. One commentator argues, “He’s probably least to blame out of them all, he simply goes to the dock and drives 2 mins down the road to let them out” and defines Robinson as “small fish” (C10) in the wider trafficking operation. This type of comment acknowledges that blame can be attributed to Robinson, but suggests that greater blame should be attached to the “big fish” in the operation and therefore seeks to negotiate “down”, as it were, Robinson’s responsibility for the deaths of the 39 victims. In terms of Appraisal, Robinson is judged negatively. However, because these arguments negotiate to reduce his culpability and hence somewhat avoid the seriousness of his crime, these judgements do not inscribe social sanction, but instead use phrases of social esteem, such as “small fish” and “silly boy” (C11). Particularly noteworthy in several of these comments is how Robinson’s involvement is reduced through “graduation” (Martin and White Citation2005, 154), which demonstrates how attitudinal expressions can be upgraded or downgraded through linguistic resources. The Facebook commentators here state that Robinson “only collected” the trailer (C4), his work for the haulage company was “not necessarily moving people” (C5), that “even if he had prior knowledge” (C8) “he only had the cab 30mins” (C9) and “he’s probably least to blame” (C10). The underlined elements in these clauses downgrade the level of Mo Robinson’s culpability through a type of graduation known as “intensification”. Essentially the commentators argue that even if Robinson was aware that there were people in the trailer his responsibility is limited. This type of argument resonates further in the Victims to Blame theme where, as we will see, several commentators argue that Mo Robinson is not to blame for the victims’ deaths, because they willingly entered the trailer.

4.3. Mo Robinson as victim

In addition to the 13 comments that view him as unknowing and the 19 comments that blame the victims addressed below, 16 comments take the view that Mo Robinson himself is a victim in this case. Some of these comments are connected to the argument of lesser culpability described above but take this one step further in arguing that Robinson’s apparent “small fish” status actually makes him another type of victim in the trafficking industry. Robinson is judged through negative social esteem when he is labelled a “patsy” (C23) and another comment argues that “if Mo is guilty he had them for the least time” and that the “real culprits” (C18) were those with whom he organised the operation.

Two commentators here argue that Robinson’s motivations may have been honourable. One states, “Maybe was genuinely thinking he was helping people” (C20), while another argues, “He may not necessarily have bad intentions […] maybe he was seeing things differently, he will make some money helping people to get in at the same time” (C14). In these comments, positive social sanction is used to cast a perpetrator in a case where 39 victims have died as ethical and moral. Obviously, it is impossible, even for those determined to avoid condemnation of Mo Robinson, such as in C14, to detach human trafficking from commercialism. For these commentators, Robinson’s greed has been partly acknowledged, albeit with a mitigation offered. One post laments that “it’s sad that a young guy like this played at high stakes and clearly lost and will pay a high price” (C28), while another states “that’s his life fucked … and all for a few easy quid or so he thought, what a mug” (C21). Any condemnation of Robinson here is restricted to the level of social esteem, whereas when he is positively evaluated social sanction is used. Forensic linguistic analysis of courtroom proceedings by Heffer (Citation2007) and Statham (Citation2016) note a pattern in the distribution of judgement used by participants at trial, in which defence arguments that acknowledge the shortcomings of a defendant will usually be restricted to judgements of social esteem. The social media comments here mirror the patterns of courtroom language in limiting any criticism of Robinson to judgements of social esteem. The same comments do not refer to the lost lives of the 39 genuine victims in this case.

There are comments that offer support to Robinson without question and without specific comment on the case. One comment lexically infantilises him as “an innocent young boy” who “has been wronged” (C24), in order to legitimise him as a victim (see 4.6). In addition to two comments in the Mo Robinson as Unknowing theme, four comments in the current theme classify Robinson as “young”, a “good looking young guy” (C14), an “innocent young boy” (C24), “a young man who is carrying out his work” (C27), and a “young guy” (C28) despite the fact that he is 25-years old, which is older than 18 of the victims in this case. C36 refers to him as “the boy”. With the exception of C78, which describes some of the victims as “youngsters”, a word common in Hiberno-English to describe youths, the victims are never described as “young”.

Six comments within the Mo Robinson as Victim theme refer to him as a victim of the media and/or social media. C15 for example states, “He only picked up trailer 25 min’s! The media are bastards for naming and demonising an innocent man” and C17, seemingly without any hint of irony, refers to “false facts” disseminated in the media and states that “papers need educated and reporters”. These condemnations are particularly judgemental in that they invoke social sanction through the implication that it is unethical that Robinson has been named at all and through the accusation that the stories are apparently untrue. The police are also judged through negative social sanction for releasing Robinson’s name. One claims, “Think this guy is as much a victim as those found. His name should never have been released” (C25) and another states, “Only the police would release his name which I find is disgraceful” (C27). The same comment includes several elements in this theme, continuing with “As it seems he is in this case a young man who is carrying out his work and finds an intolerable horror only to be persecuted by the media, guilty until proven innocent springs to mind” (C27). We note that “intolerable horror” only refers to the perpetrator. C27 illustrates a link between media coverage and the legal process, which is elaborated upon by a number of users who frame their defence of Robinson through a concern for due process. C16 refers specifically to “trial by media” and asks, “How is he going to get a fair trial when social media has already convicted him? […] his lawyers (if they’re worth their salt) will argue he can’t get a fair trial”.

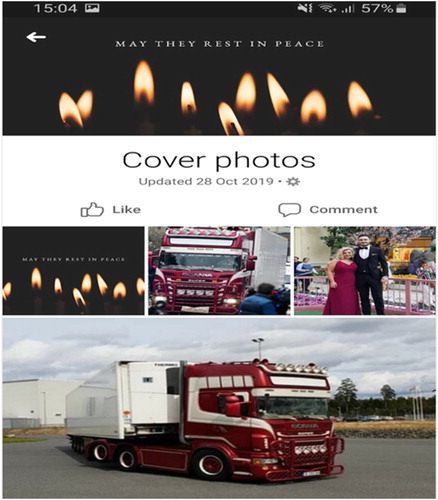

The initial images used on the Facebook site also illustrate the construction of Robinson as unknowing and as a victim. Facebook has two dominant methods for visual representation: the “cover photo”, which is a landscape image placed across the top of a page, and the “profile picture”, which is a smaller image that appears in a circle and slightly overlaps the larger cover photo (see ). The first cover photo depicted Robinson embracing his partner, with both smiling at the camera (see ). This representation essentially humanises him, “demanding” our sympathy (Kress and van Leeuwen Citation1996). After he was charged, images of Robinson and his partner and of his truck were updated to an image commemorating the victims. The initial images were intended to further the Mo Robinson as Unknowing theme by establishing his professional status as “just the delivery driver” (C13). The updated commemorative image shows several lit candles against a black background, bearing the inscription “May they rest in peace”. The candles symbolise the souls of the deceased, a well-established Judeo-Christian convention. This trajectory of perpetrator to victims through visual representation is also detectable in the profile pictures (see ). Initially the same images of Robinson and his partner, and of his truck were also used as profile pictures. After Robinson’s culpability emerged, the page’s profile picture was updated to the Vietnamese flag, which can be seen at the bottom-left corner of the memoriam image as an encircled five-point star against a red background. It slightly protrudes into the image, suggesting that they belong together. Although it is the default layout of Facebook that profile pictures are placed on top of cover photos, in this case the Vietnamese flag overlapping the memoriam image of the candles seems to reinforce the relationship between the two images. It is particularly noteworthy that this recognition of the victims seems to have depended upon the culpability of Robinson. The images do not offer commemoration or recognition of the deceased until after the extent of Robinson’s involvement in their deaths begins to emerge.

4.4. Process of justice

In a similar vein to those comments that argue that Mo Robinson has been the victim of trial by media, 11 comments refer to the process of justice itself. Eight comments refer to the distinction between charges being brought by police and the accused being brought forward for trial and/or being convicted by a jury. Four of these refer in some form to the principle of the presumption of innocence. C30, whilst somewhat endorsing the unlikely outcome of a dismissal of the case on fair trial grounds, is one of the few comments that connects the process of justice to “the sake of the 39 victims and their families”. C40, making a judgement of negative social sanction of the other posts on the page, states that it is “maddening that everything is centred on and around him and not the 39 victims”. Some of the comments in the Process of Justice theme can therefore not be categorised into those themes that defend Robinson.

The position of other comments is more complex. C32 also judges the content of the page negatively, stating that those who equate being charged with a crime with being tried and convicted for it should “try reading before making stupid statements”. In this case, the other users judged are those who condemn Robinson. The comment continues, “A charge isn’t an indication of guilt and definitely not conviction”. C33 says, “Getting charged is not being guilty..still a court case for him to prove he is innocent..a lot of people including myself can tell you innocent people can pick up charges”. While these statements semantically operate as generalised statements about what a charge “is” or “is not”, as mere representatives rather than expressives in Searle’s (Citation1969) terms, the adverbial modification that a charge is “definitely not a conviction” and the qualification and presupposition that there “is still a court case for him to prove he is innocent” implies affiliation with or sympathy for Robinson. On an interpersonal level therefore, we can view these seemingly normative statements as encoding stance. They invoke negative judgements of social sanction on those who would view Robinson as guilty because he has been charged. From a legal standpoint this is of course accurate in the first instance. Robinson pleaded guilty to plotting to assist illegal immigration in November 2019 and to manslaughter in April 2020, so in October 2019 when these comments were made Robinson’s guilt had not been legally established. When analysed linguistically, however, these comments are not merely neutral observations.

4.5. Punishment/penal populism

This article has progressed from those themes that defend Robinson to those which, at least ostensibly, would claim perhaps to defend due process, and eventually to those which condemn, rather than defend him. In the Punishment/Penal Populism theme, 18 comments accept Robinson’s guilt and call for punishment. Within these comments there are 20 judgements of negative social sanction that reveal that these users have a strongly adverse view of Robinson and his actions. Robinson is called a “disgraceful person” (C48), a “greedy, vile money-grabbing scumbag” (C47), a “bastard” (C54), an “evil sectarian Loyalist” (C55), an “evil bastard” (C56), “SCUM” (C57) and a “tramp” (C58), for example. 13 additional occurrences of social sanction call for Robinson to be punished for his crimes, in most cases calling for the imposition of a lengthy prison sentence, for example: “I hope he never gets out of prison” (C47), “hope the bastard gets life” (C49), “mandatory life sentence” (C53), “lock him up and throw the fucking key away” (C50). These comments invoke positive social sanction in that they describe what should happen if justice is to be served and again reveal an adverse and antagonistic response to the actions of Mo Robinson. In a parallel of courtroom discourse, when commentators refer to the heinousness of Robinson’s crimes and call for his punishment, judgements of social sanction are used. Heffer (Citation2007) and Statham (Citation2016) illustrate that while the legal language of the defence often includes judgements of social esteem, seen in the Mo Robinson as Victim theme, the prosecution will rely more heavily on judgements of social sanction. The comments in this theme therefore demonstrate that social media users utilise the language of Appraisal in a way that mirrors the language of courtroom prosecutors.

An aspect of this case that was covered extensively in traditional media and commented upon at length on various social media platforms was the luxurious lifestyle enjoyed by Robinson and his partner. Demonstrating awareness of the processes of investigation and punishment in organised crime cases, a number of commentators utilise positive social sanction to call for Robinson’s assets to be seized as they represent the proceeds of crime, “He should have his assets seized and sold and money given to families of the victims” (C48), “All their assets should be seized & the money put towards the return of the victims’ bodies to their families so they can have a proper burial” (C51). The comments assume that Robinson’s partner and family had knowledge of his criminality and invocations of negative social sanction condemn their role in his actions and positive social sanction call for punishment: “They probably know he was involved. With the amount of money involved I am certain his nearest and dearest knew. Maybe they will be arrested too at some point […] His girlfriend is expecting as well but no sympathy from me, he will still see his child through prison visits” (C44), “she knew all about what he was doing she loves the lifestyle” (C46). Robinson and his partner’s status as parents is also addressed through judgements of social sanction, they are condemned as “not fit parents take the kid of them” (C45). In a reflection of the penal populism often present in societal commentaries on crime, some posts also refer to the death penalty by implication, as in, “an eye for an eye” (C54), and directly, as in “Unfortunately we don't have the death penalty so we are going to have to pay to keep this kretin locked up for a long time” (C48). These comments appear to confirm that social media can act as a powerful tool for espousing law and order discourses (Powell, Overington, and Hamilton Citation2018).

Most of the comments in the Punishment theme followed Robinson’s being charged and a clear dichotomy emerges in the patterns of Appraisal between these comments and those in the Process of Justice theme. Most comments here were also the result of charges being brought but whilst comments in the Punishment theme were clear in their condemnation, those in the Process of Justice theme pivoted instead to the scenario in which Robinson’s guilt had yet to be proven. The extent to which these comments represent a defence of Robinson or should be seen as merely a defence of due process essentially depends on how much legal knowledge the speaker truly has. Judgements of social sanction are evident in both themes, but there are marked deviations. The Process of Justice theme contains negative judgements that target the role of the media while the judgements of social sanction in the Punishment theme are of positive social sanction when referring to justice; they are ethical and moral calls for Robinson to be punished. Negative social sanction in the Punishment theme is targeted at Robinson on a personal level, there is no attempt to conceptually detach him from the deaths of the victims. Whereas the Process of Justice theme refers explicitly to the presumption of innocence and to varying degrees discusses the role of Crown Prosecutors in the charging of Robinson, in the Punishment theme guilt is presumed.

4.6. Victims to blame

Most comments on the page, 19 of the 91 comments in this data set, reflect the anti-immigration ideologies that are prevalent in Britain and are consistently constructed by the policies of the Tory government and the right-wing media (e.g. Gabrielatos and Baker Citation2008). The comments in this theme are highly judgemental. There are 38 instances of judgement contained within the 19 comments considered here. Anti-immigrant ideologies that are bluntly articulated with uncomfortable frequency on this page fit into a number of categories.

The first category comprises comments that condemn the dead as illegal immigrants who have effectively forfeited their status as victims. There are 10 explicit references to the victims as “illegal” or as entering Britain “illegally”. Comments such as “they were trying to get into the country illegally so they weren’t innocent” (C69) and “as far as I’m concerned those people killed themselves trying to sneak into a country illegally” (C72) inscribe negative social sanction to the deceased. The crux of this perspective is expressed by C70: “39 wank bags who should of stayed in their own country or used their savings for proper visas no sympathy at all”. Some comments are explicitly connected to the Mo Robinson as Victim theme. C62, for example, further claims, “Before people say they are desperate the lorry driver was probably desperate too otherwise why do a job like that”, whilst other comments condemn Robinson alongside his victims, “Them 39 people were illegal, absolutely no right to be here, no sympathy for them and anyone who got them here” (C75). C75 again inscribes negative social sanction through another use of “illegal” but attaches the illegality to both perpetrators and victims. As well as through illegality, the victims are condemned through references to an assumed intentionality to damage Britain in arguments such as C74 – “they just want to send the money back home” – and more explicitly in C79 – “they were coming here to undermine the UK society by being here illegally. Exactly who was trying to fill their pockets off the back of others? That's right, the illegals. Millions of people have come to the UK to contribute, not take”. The construction of immigration as having a negative economic impact in society is clearly evident here. Van Dijk (Citation1991), Gabrielatos and Baker (Citation2008) and Wodak (Citation2015), amongst others, have demonstrated that immigrants are often constructed through a limited number of narrative frameworks, particularly in right-wing sections of the print media. Alongside a negative economic impact, these include violence, criminality, damaging public health and threatening social relations. The ideological construction of immigration as damaging society without acknowledging any of the benefits of diversity in some sectors of the media is explicitly reflected here in Facebook comments, which view immigrants as “coming here to undermine the UK society” (C79).

Five comments condemn the families of victims through negative social sanction for being complicit in human trafficking. C78 includes an admonition almost as well-worn as “coming over here, taking our jobs” by saying “they shouldn’t be here anyway”. The same comment goes on to state, “They paid £30k each … . The parents of the dead youngsters are as guilty as anyone else involved! […] There is 2 sides to this … . These gangs wouldn't be able to work if people weren't throwing money at them!”. Equally condemned in five comments using negative social sanction are foreign governments who “couldn’t care less” (C63) about their citizens. In two fairly predictable generalisations, the Chinese government, despite the fact that Robinson’s victims were from Vietnam, is condemned for “the fact that they run a country in a way that many of their people want or need to run from” (C62) and for controlling the internet (C61). The somewhat incoherent argument in this comment is that people are “sitting ducks for traffickers” because “they literally don’t know what’s going on” (C61).

There are interrelated comments that recognise the victimhood of the dead in five occurrences of negative social sanction, but statistically these pale in comparison to the 25 judgements that blame the victims and their families. Even in comments where victims are viewed as desperate and vulnerable, such as in “They are let down by their governments, and taken advantage of by the traffickers. The poor girls could have possibly been made to work in brothels. Human traffickers are the scum of the earth” (C61), anti-immigration ideologies persist. Both human traffickers and foreign governments are condemned here, but there are no arguments proffered that destination countries should help victims. Comments like “It is sad but those families supported the whole illegal activity and know from previous smuggling failures the dangers. So none of the dead are 100% innocent in all of this. If there where no one trying to cross boarders illegally there would never be these situations” (C64) reflect a general trend in public discourses around illegal immigration. These are focused on border security and prioritise reactionary over preventative enforcement of human trafficking and smuggling, and largely fail to address root causes such as endemic poverty gaps, a global capitalist obsession with cheap labour, conflict and other structural inequalities.

It is noteworthy that C61 refers to the victims as “poor girls”. Gregoriou and Ras (Citation2018) and Ras (Citation2020) demonstrate that media representations of human trafficking legitimise certain types of victims. Children and women, rather than adults and men, are identifiable as victims in large corpora of British national newspapers. The lack of sympathy shown to the victims of Mo Robinson across the media spectrum and on this Facebook page is striking. Of the 39 victims in this case, eight were women and, if we assume 18-years old as the threshold of adulthood, none could be described as “girls”, three victims were boys under 18, the remaining 28 were adult males. Given that a large majority of these victims do not fit into media-made categories of the legitimate “ideal victim” (Christie, Citation1986), lack of sympathy is prevalent, as demonstrated in the comments discussed so far. C61 misclassifies the victims as “girls” before sympathy is expressed, whilst the only victim whose photograph appears on the page is Pham Thi Tra My, one of the younger female victims (see below). The user has imbedded a news article from World News Australia, which shows the young woman with bright red lips and a yellow flower tucked behind her ear in front of what appears to be a building. This individualisation humanises this victim, unlike all the others who remain nameless and invisible and hence removed from the viewer/reader (Van Leeuwen Citation2008). The juxtaposition of the image of the woman with the headline “Truck horror: Naked, foaming at the mouth” amounts to a sensationalised and arguably sexualised portrayal of the victim, evoking connotations of sex trafficking. The headline also uses a well-trodden theme in crime reporting and true crime, Gothicism, as expressed in “truck horror” (Picard and Greek Citation2007).

4.7. Awareness of racism

Thus far we have seen that trafficking narratives and the characters within them are often imbued with racialised and gendered assumptions, which hamper effective assistance to exploited workers and the development of policies to prevent trafficking (Balgamwalla, Citation2016). Despite the dominating view of victims correlating with the findings of Gregoriou and Ras (Citation2018) through a particular absence of sympathy or close scrutiny of the root causes of human trafficking on this Facebook page, there are some commentators who recognise the highly problematic nature of some of the sentiments expressed. Negative judgements of social sanction are also the mainstay of stance in these five comments. However, in this case they judge not the victims, but both those who condemn them and those who defend Robinson. C84 problematises the page itself by claiming that Robinson’s status as a British white male engenders a willingness to excuse his actions that would not be so prevalent if he could be identified as “other”. For example, “People are still saying he’s innocent … ..well the police aint … ..dont suppose this page would even be up if it was a romanian driver or a bulgarian would it??” (C84). C82 responds to another comment that equates the victims with “asylum seekers” who are inevitably assumed to be involved in criminality: “You’re making a lot of assumptions on your own prejudice. How do you know they aren’t under any form of abuse or national government affect? Their political situation may force them into wanting to flee, all I can say is thank god you aren’t a police officer with your narrow view” (C82). This is the comment in this data set that comes closest to any analytical awareness of the structural drivers of immigration and trafficking. Comments that call out racism, as it were, are unfortunately less frequent than those that express it, but there are dissenting voices present on this page that reject those narratives that seek to diminish Robinson’s responsibility, or those that attribute blame to the deceased without engaging in any in-depth consideration of the very complex issues raised by this case.

5. Conclusion

This article has provided an analysis of some of the comments and images on the Free Mo Robinson Facebook page. Our examination of the data acknowledges Rafter’s (Citation2007) view that popular culture can tell us much about how crime is viewed in the social world. By applying Martin’s (Citation2000) and Martin and White's (2005) Appraisal framework and examining some of the visual elements of the page, we have upheld Hayward and Young’s (Citation2004) contention that in an analysis of (social) media representation of crime a consideration of emotion and affect should be foremost. Social media platforms such as Facebook accommodate new technological practices for making meaning and Yar (Citation2012, 207) reminds us that we should view these in terms of their status as social practice. Just as in other areas of discourse analysed by CDA, language on social media operates ideologically. Despite the democratising potential of social media and other forms of computer mediated communication, these online fora will not necessarily be ideologically divergent from dominant, common-sense principles that are constructed in other forms of institutional discourses, such as in the print and broadcast media or political discourse.

Our analysis has found that a majority of comments on the Free Mo Robinson page interpret this event in ways that seek to reduce the culpability of the perpetrator, whilst the most dominant theme in this data is represented by comments that blame the victims themselves. Again, this is hardly surprising given the site was set up to “free” Mo Robinson. What is a matter for concern, however, is the degree to which the victims are judged through the language of social sanction for their supposed illegality and criminality and the threat they are believed to pose to social harmony. This linguistic representation reflects and reinforces the anti-immigrant ideologies of right-wing media and politicians in the UK. One reason for this may be that the victims in this case do not correlate with factors that would define them as “ideal” or “legitimate” victims of human trafficking. Most of the victims were neither very young nor vulnerable females and they were also deemed to have chosen to pursue this form of immigration willingly, which goes further in explaining the lack of sympathy in much of the judgemental language of these comments. Comments that focus on the choice of these victims to engage in irregular entrance to the UK obviously ignore the systemic inequalities that drive this type of immigration in the first place. Although some comments condemn the traffickers for exploitation of the victims, these rarely acknowledge the root causes of inequality and are often focused on the view that traffickers are operating illegally against the UK and that they are assisted by the victims and their families or by the victims’ home countries. We certainly find language that condemns Mo Robinson in the strongest social sanction terms in this data set, many of which reflect and reinforce notions of penal populism. While these comments are less frequent than those that seek to reduce Robinson’s culpability, they are also highly judgemental. Nonetheless, these occurrences are less prominent than those that blame the victims and seek to either exonerate Robinson or mitigate his culpability.

One of our main questions in this article was how users align or dis-align with public and mainstream media perceptions of immigration and human trafficking. Our analysis suggests a high degree of alignment. Nonetheless, we have produced some evidence of the potentiality of social media to accommodate dissenting and challenging views. The fact that some users acknowledge the highly problematic nature of the comments of their fellow contributors and explicitly point out that the mitigation offered to Robinson would likely not be so forthcoming if he was not part of the ethnic and national majority, suggests a more critical engagement with Free Mo Robinson.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Andrea Mayr

Andrea Mayr is Lecturer in Media and Communication at Zayed University, UAE, where she teaches and researches in multimodal critical discourse studies, with a particular focus on crime. She is author of The Language of Crime and Deviance (2012) and co-author of Language and Power (2018). She is currently working on the second edition of How to Do Critical Discourse Analysis: A Multimodal Introduction (co-authored with David Machin).

Simon Statham

Simon Statham is Lecturer in English Language at Queen’s University Belfast where he teaches and researches in critical linguistics and stylistics. He is author of Redefining Trial by Media (John Benjamins, 2016) and co-author (with Paul Simpson and Andrea Mayr) of Language and Power (Routledge, 2018). His most recent publication is an article on crime fiction adaptation in the International Journal of Literary Linguistics.

References

- Balgamwalla, S. 2016. “Trafficking in Narratives: Conceptualising and Recasting Victims, Offenders, and Rescuers in the War on Human Trafficking.” Denver Law Review 94 (1): 1–41.

- BBC News ‘Lorry Driver Mo Robinson Admits Plot after 39 Migrant Deaths’. 2019, Nov. 25. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-50545658

- Canovan, M. 1999. “Trust the People! Populism and the Two Faces of Democracy.” Political Studies 47: 2–16.

- Cavender, G., and S. Deutsch. 2007. “CSI and Moral Authority: The Police and Science.” Crime, Media, Culture 3 (1): 67–81.

- Christie, N. 1986. “The Ideal Victim.” In From Crime Policy to Victim Policy, edited by E. A. Fattah, 17–30. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Cohen, S., and J. Young. 1981. The Manufacturing of News: Social Problems, Deviance and the Mass Media. London: Constable.

- Diba, P., G. Papanicolaou, and G. Antonopoulos. 2019. “The Digital Routes of Human Smuggling? Evidence from the UK”. Crime Prevention and Community Safety. doi:10.1057/s41300-019-00060-y.

- Fawcett, C., and S. Kohm. 2019. “Carceral Violence at the Intersection of Madness and Crime in Batman: Arkham Asylum and Batman: Arkham City.” Crime, Media, Culture 16 (2): 265–285.

- Ferrell, J., K. Hayward, and J. Young. 2008. Cultural Criminology: An Invitation. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

- Gabrielatos, C., and P. Baker. 2008. “Fleeing, Sneaking, Flooding: A Corpus Analysis of Discursive Constructions of Refugees and Asylum Seekers in the UK Press, 1996-2005.” Journal of English Linguistics 36 (1): 5–38.

- Gregoriou, C., and I. Ras. 2018. “Representations of Transnational Human Trafficking: A Critical Review.” In Representations of Transnational Human Trafficking: Present-day News Media, True Crime and Fiction, edited by C. Gregoriou, 1–25. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hall, S., C. Critcher, T. Jefferson, J. Clarke, and B. Roberts. 1978. Policing the Crisis: Mugging, the State, and Law and Order. London: Macmillan.

- Hayward, K., and J. Young. 2004. “Cultural Criminology: Some Notes on the Script.” Theoretical Criminology 8 (3): 259–273.

- Heffer, C. 2007. “Judgement In Court: Evaluating Participants in Courtroom Discourse.” In Language and the Law: International Outlooks, edited by K. Kredens, and S. Godz-Raskowski, 145–179. Amsterdam and Philadelphia, PA: John Benjamins.

- Kennedy, L. 2018. “Man I’m all Torn up Inside’: Analysing Audience Responses to Making a Murderer.” Crime, Media, Culture 14 (3): 391–408.

- Kress, G., and T. van Leeuwen. 1996. Reading Images: The Grammar of Visual Design. London: Routledge.

- Machin, D. 2013. “What is Multimodal Critical Discourse Studies?” Critical Discourse Studies 10 (4): 347–355.

- Machin, D., and A. Mayr. 2012. How to Do Critical Discourse Analysis. London: Sage.

- Martin, J. R. 2000. ““Beyond Exchange: APPRAISAL System in English”.” In Evaluation in Text, edited by S. Hunston, and G. Thompson, 142–176. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Martin, J. R., and P. R. R. White. 2005. The Language of Evaluation: Appraisal in English. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Mayr, A., and D. Machin. 2012. The Language of Crime and Deviance: An Introduction to Critical Linguistic Analysis in Media and Popular Culture. London: Continuum.

- Myers, G. 2010. The Discourse of Blogs and Wikis. London: Continuum.

- Newburn, T. 1997. “Youth Crime, and Justice.” In The Oxford Handbook of Criminology, edited by M. Maguire, R. Morgan, and R. Reiner, 490–523. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Papacharissi, Z. 2015. “Affective Publics and Structure of Storytelling: Sentiment, Events and Mediality.” Information, Communication and Society 19 (3): 307–324.

- Picard, C., and C. Greek. 2007. “Introduction: Toward a Gothic Criminology.” In Monsters in and Among Us: Toward a Gothic Criminology, edited by E. Ingebretsen, 1–43. Madison, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press.

- Powell, A., C. Overington, and G. Hamilton. 2018. “Following #Jill Meagher: Collective Meaning-Making in Response to Crime Events via Social Media.” Crime, Media, Culture 14 (3): 409–428.

- Pratt, J. 2007. Penal Populism. London: Routledge.

- Rafter, N. 2007. “Crime, Film and Criminology: Recent Sex-Crime Movies.” Theoretical Criminology 11 (3): 403–420.

- Rafter, N., and M. Brown. 2011. Criminology Goes to the Movies. New York, NY: New York University Press.

- Ras, I. 2020. ““Child Victims of Human Trafficking and Modern Slavery in British Newspapers”.” In Contemporary Media Stylistics, edited by H. Ringrow, and S. Pihlaja, 191–214. London and New York: Bloomsbury.

- Salter, M. 2013. “Justice and Revenge in Online Counter-Publics: Emerging Responses to Sexual Violence in the Age of Social Media.” Crime, Media, Culture 9 (3): 225–242.

- Searle, J. R. 1969. Speech Acts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Statham, S. 2016. Redefining Trial by Media; Towards a Critical-Forensic Linguistic Interface. Amsterdam and Philadelphia, PA: John Benjamins.

- Stratton, G., A. Powell, and R. Cameron. 2017. “Crime and Justice in Digital Society: Towards a “Digital Criminology?” International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy 6 (2): 17–33.

- Van Dijk, T. 1991. Racism and the Press. London: Routledge.

- Van Leeuwen, T. 2008. Discourse and Practice: New Tools for Critical Discourse Analysis. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Websdale, N., and J. Ferrell. 1999. “Taking the Trouble.” In Making Trouble: Cultural Constructions of Crime, Deviance and Control, edited by J. Ferrell, and N. Websdale, 349–364. Hawthorne, NY: Aldine de Gruyter.

- Wilson, J., and A. Kirk. 2018. “Three in Five Britons Support a ‘Hostile Environment’ for Illegal immigration, Poll Shows”. The Telegraph. May 26. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/politics/2018/05/26/three-five-britons-support-hostile-environment-illegal-immigrants/.

- Wodak, R. 2015. The Politics of Fear. What Right-Wing Populist Discourses Mean. London: Sage.

- Yar, M. 2012. “Crime, Media and the Will-to-Representation: Reconsidering Relationships in the New Media Age.” Crime, Media, Culture 8 (3): 245–260.