?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Ateji (当て字) pertains to one of the unique uses of language in the manga that is constructed with two types of Japanese scripts. Its one-of-a-kind structure presents challenges in translation, but feasible solutions have hardly been explored. Drawing on ateji categories, social semiotic multimodal approach and translation procedures, this study performs qualitative content analysis to identify practical ways to reconstruct the closest meaning of ateji. It finds that most of the adopted translation procedures reflect partial meaning transformations because of the target language’s lack of semiotic resources that can be used to convey ateji’s complex meanings. Nevertheless, translations published in the 2010s have shown that a smaller font size – the semiotic resource of the typography mode – is used in glosses to produce the closest meaning transformation of ateji into the target text. This finding has also revealed that writing and typography are effective modes of ateji translation.

1. Introduction

Manga, which refers to comics originating from Japan, has become a global phenomenon. Although it shares several similarities in format with Western comics (Jüngst Citation2004, 83), it also has seven unique basic storytelling techniques: iconic characters, genre maturity, sense of place, character designs, wordless panels, small real-world details, subjective motion, and emotionally expressive effects (McCloud Citation2006, 216). In terms of language use, ateji (当て字) is one of manga’s unique characteristics. The Japanese language has three writing scripts: kanji, hiragana, and katakana. Kanji is the Chinese character, hiragana is the “cursive Japanese syllabary used primarily for native Japanese words” and katakana is the “angular Japanese syllabary used primarily for loanwords” (Weblio Citation2021). Within the language of manga, ateji is the joining of two words into one through a reading gloss, known as furigana, which is inserted above or beside another that gives its pronunciation or reading (Lewis Citation2010, 28). The three writing scripts are utilised in ateji formation in the manga. Manga authors use ateji creatively and strategically to add more layers of meaning to the dialogue and further develop the story’s character and complex worlds (Lewis Citation2010). For instance, Nami, a female pirate in One Piece, has a fighting tactic called  – an ateji combined with kanji and katakana. The kanji 風速計 (fūsoku kei) means “anemometer”, and it is used because the spinning top of Nami’s wand looks similar to that of the anemometer cup. The furigana スイングアーム (suingu āmu), an English loanword (swing arm) written using katakana, reflects Nami swinging her arm when performing this tactic. Moreover, the use of an English loanword shows Nami’s English-speaking origin. These multiple layers of meanings complicate their transformation into the target language – especially when this has only one script.

– an ateji combined with kanji and katakana. The kanji 風速計 (fūsoku kei) means “anemometer”, and it is used because the spinning top of Nami’s wand looks similar to that of the anemometer cup. The furigana スイングアーム (suingu āmu), an English loanword (swing arm) written using katakana, reflects Nami swinging her arm when performing this tactic. Moreover, the use of an English loanword shows Nami’s English-speaking origin. These multiple layers of meanings complicate their transformation into the target language – especially when this has only one script.

Manga is popular worldwide, and it has led translation studies to address different aspects of the genre: format (Rota Citation2008/Citation2014); scanlation (Rampant Citation2010); 擬音語 (giongo, words used to mimic sound) and 擬態語 (gitaigo, words used to mimic actions, situations or behaviours that do not involve sound) (Fujimura Citation2012; Inose Citation2010); mode fluidity (Huang and Archer Citation2014); typefaces ( Armour and Takeyama Citation2015); wine language (Jones and Normand-Marconnet Citation2016) and agency in non-professional manga translation (Abdolmaleki, Tavakoli and Ketabi Citation2018; Fabbretti Citation2019). Nevertheless, manga translations have received less attention than comic translations (Jüngst Citation2004, 83) because the manga is not accepted as media content, and the researchers have insufficient knowledge of the Japanese language (O'Hagan Citation2007).

In addition, existing studies on ateji are rare and mainly focus on examining its categories used in manga (Lewis Citation2010) and on how native speakers perceive different ateji (Melander Citation2016). Ateji translation has only been investigated by Gyllenfjell (Citation2013) and Ali (Citation2015); hence, little is currently known about the translation of ateji in manga – especially from a social semiotic multimodal perspective.

This study adopts a qualitative content analysis approach to shed light on this issue and examine the translation of ateji from Japanese to Malay. By adopting Bezemer and Kress’s (Citation2016) social semiotic multimodal approach, this study first explains the modes involved in meaning–making in the manga. Afterward, drawing on Lewis’s (Citation2010) five categories of ateji, it presents the forms of ateji identified in the study. Then, through the social semiotic multimodal approach and Kaindl’s (Citation1999) translation procedures, it discusses how manga translators use the available modes and semiotic resources in the target social context to translate the message conveyed by ateji.

2. Relevant studies

2.1. Ateji and translation

Before the Nara period, as in contemporary Japanese, ateji had been used as a phonetic guide (Sasahara Citation2010, 893). Lewis (Citation2010) noted that ateji is used in manga not only to provide readers with a phonetic guide to read kanji but also to convey more layers of meaning. She proposed five categories of ateji – translative, denotive, contrastive, abbreviation/contrastive, and translative/contrastive – with each form having its features (Citation2010, 32–34). Section 3.2 further explains these.

Melander (Citation2016) identified the five types of ateji as specified by Lewis (Citation2010) and conducted a questionnaire study involving native Japanese speakers to obtain more sociolinguistic data regarding the nuances, implications, societal implications, functions, and other elements of these styles. Investigations on ateji translation were only conducted by Gyllenfjell (Citation2013) and Ali (Citation2015). Gyllenfjell (Citation2013) discussed ateji translation procedures based on Newmark’s translation procedures. The identified translation procedures are transference, compensation, functional equivalent, omission/complete change, paraphrase, and partial translation. The analysis only examined the ateji with kanji, with a different reading from its furigana, and the ateji that conveys additional meanings. The current study adopts a similar stance and does not include ateji that only provide a phonetic guide. Further, Ali (Citation2015) identified five main types of translation methods (patterns): (1) colloquial language is translated, (2) foreign words’ fantasy and fictional elements are lost in translation, (3) pronouns signifying further distance are translated, (4) modified meanings that are fixed and clear are translated and (5) ateji in the form of manga-based original words is omitted. Gyllenfjell (Citation2013) and Ali (Citation2015) have provided insights into the translation procedures that can be adopted when translating ateji; however, they have not considered manga’s multimodal nature and changes in the translators’/publishers’ agency.

2.2. Manga/comic translation

Research on manga and comic translation has been conducted from different perspectives, such as globalisation (Jüngst Citation2008/Citation2014; Giovanni Citation2008/Citation2014), localisation (Zanettin Citation2008/Citation2014; Citation2014), multimodal perspectives (Borodo Citation2015; Kaindl Citation2004), social semiotic multimodal perspectives (Huang and Archer Citation2014; Armour and Takeyama Citation2015), audio–visual perspectives (Borodo Citation2016) and censorship (Zanettin Citation2018). Some scholars who uphold the importance of manga’s multimodal nature and the interaction between modes have applied a general multimodal perspective or a social semiotic multimodal perspective with a combination of different theories. In this regard, Huang and Archer (Citation2014) adopted Halliday’s (Citation1978) metafunctional view of text and studied the relation between typography and translation to examine how different layouts can shape meaning in the official translation and scanlation. Their study revealed that the potential of modes in the manga is not strictly controlled by the logic of space and time but by the mode user’s decisions (in this case, the author and the translator), which determine the mode that is most effective in gaining readers’ attention and is suitable for conveying certain meanings. Huang and Archer (Citation2014) also pointed out that social semiotic multimodal theory can best explain manga translation because modes and their use are studied in social contexts; thus, manga translation is about translating not only images and writings but also semiotic systems embedded in evolving social practices.

Armour and Takeyama (Citation2015) adopted a broad theoretical framework drawn from previous work on multimodality, typography, and Jewitt's (Citation2009)social semiotic approach to multimodal analysis to examine whether typeface fulfills its role of bringing meaning from the source text to the target text. They further argued that it seems challenging to use different typefaces in the target text to provide the same reading experience and mood as in the source text; therefore, choosing the typeface that functions well in the target text is an important shift that can occur in manga translation. However, while Huang and Archer’s (Citation2014) and Armour and Takeyama’s (Citation2015) research, which used manga as data and adopted multimodal perspectives, yielded significant findings, ateji has not been examined through a social semiotic multimodal lens – and particularly through the social semiotic multimodal approach proposed by Bezemer and Kress (Citation2016). Thus, this study attempts to fill this research gap.

3. Theoretical framework

3.1. Social semiotic multimodal approach

Bezemer and Kress (Citation2016) proposed the social semiotic multimodal approach, which this study uses to analyse how ateji produces meaning in manga and how translators use available multimodal resources in the target social context to translate ateji. This approach provides comprehensive concepts for systematic analysis; the ones adopted in this study are sign maker, motivated signs, modes, semiotic resources, modal affordances, multimodal ensembles, interest, agency, social change, transformation, and transduction. Sign maker refers to a sign’s producer and interpreter, and interpreting is the remaking of a sign (Jewitt, Bezemer, and O’Halloran Citation2016). In this study, manga authors are the producer of all signs as they make meaning using different modes and semiotic resources; meanwhile, the translators or publishers are the interpreters who reconstruct these signs to produce target texts. Motivated signs refer to all the signs used in meaning–making, driven by the sign maker’s interests. Modes are a set of socially shaped and culturally available material resources for creating meaning. The types of modes proposed by Bezemer and Kress (Citation2016) are speech, writing, image, gaze, gesture, and layout. Semiotic resources are social semiotics that is developed, shaped, and constantly reshaped by community members depending on their interests to produce meaning. Bezemer and Kress (Citation2016) also proposed semiotic resources under each mode; for instance, those under the mode of writing are grammar, syntax, lexis as well as typeface and font size (graphical resources) (Bezemer and Kress Citation2016, 16–17). Modal affordance refers to a mode’s potential and limitation to create meaning. Multimodal ensembles refer to modes and semiotic resources operating as complex signs and functioning as complements to convey meaning (Bezemer and Kress Citation2016). Interest refers to a sign maker’s subjectivity, which consists of all their relevant social experiences. The sign maker’s interest shapes their agency, which refers to one’s choice of resources to design a sign complex to make meaning (Jewitt, Bezemer, and O’Halloran Citation2016). A social construct is the field of power-governed actions that produce social change, which then causes semiotic change. Bezemer and Kress (Citation2016) explained that we can understand social change and the characteristics of a social context through this assumption by analysing semiotic changes, which can be explained using the concepts of “transformation” and “transduction.” The former refers to the change in the arrangements of entities in a mode, although these entities remain within the same mode. Conversely, the latter refers to an entity in one mode that has changed to be transmitted in another; for example, a meaning component conveyed through the image mode has changed to being communicated through the writing mode.

3.2. Forms of ateji

Lewis (Citation2010, 32–34) proposed five categories of ateji, namely translative, denotive, contrastive, abbreviation/contrastive, and translative/contrastive ateji. These categories of ateji are comprehensive; thus, this paper draws primarily on them to identify forms of ateji in the data under study. For translative ateji, the kanji is the translation of the pronunciation written in furigana. For example, ateji  consists of kanji 恐怖の間 (kyōfu no ma), which is the translation for the furigana テラー・ルーム (terā rūmu), both denoting “terror room.” The furigana of translative ateji almost always involves English words to convey an aura of foreignness or coolness (Lewis Citation2010). Translative ateji is useful in explaining terminology by enabling manga authors to use terms regardless of the reader’s knowledge of them. This approach can also eliminate the need for footnotes, which would affect reading flow (Lewis Citation2010). The kanji of a denotive ateji is a proper noun, while the furigana is a pronoun spoken by a character in conversation, such as “that” and “he.” For example,

consists of kanji 恐怖の間 (kyōfu no ma), which is the translation for the furigana テラー・ルーム (terā rūmu), both denoting “terror room.” The furigana of translative ateji almost always involves English words to convey an aura of foreignness or coolness (Lewis Citation2010). Translative ateji is useful in explaining terminology by enabling manga authors to use terms regardless of the reader’s knowledge of them. This approach can also eliminate the need for footnotes, which would affect reading flow (Lewis Citation2010). The kanji of a denotive ateji is a proper noun, while the furigana is a pronoun spoken by a character in conversation, such as “that” and “he.” For example,  consists of kanji 三葉 (Mitsuha) to denote the name of the character, and furigana わたし (watashi) is a pronoun spoken by Mitsuha to refer to “I.” Denotive ateji can reflect relationships between characters and indicate the roles of specific ones (Lewis Citation2010). Contrastive ateji is formed by two different Japanese words – for instance, kanji 記憶 (kioku) and furigana こころ (kokoro) combine as contrastive ateji to convey the integration concepts of memory and soul (Lewis Citation2010). An author can use the differences and similarities between these words to either broaden or narrow the meanings of the ateji (Lewis Citation2010). Abbreviation/contrastive and translative/contrastive ateji are subsets of their respective categories. Abbreviation/contrastive ateji is constructed with English words written in katakana and an abbreviation, which facilitate quick reading (Lewis Citation2010), such as

consists of kanji 三葉 (Mitsuha) to denote the name of the character, and furigana わたし (watashi) is a pronoun spoken by Mitsuha to refer to “I.” Denotive ateji can reflect relationships between characters and indicate the roles of specific ones (Lewis Citation2010). Contrastive ateji is formed by two different Japanese words – for instance, kanji 記憶 (kioku) and furigana こころ (kokoro) combine as contrastive ateji to convey the integration concepts of memory and soul (Lewis Citation2010). An author can use the differences and similarities between these words to either broaden or narrow the meanings of the ateji (Lewis Citation2010). Abbreviation/contrastive and translative/contrastive ateji are subsets of their respective categories. Abbreviation/contrastive ateji is constructed with English words written in katakana and an abbreviation, which facilitate quick reading (Lewis Citation2010), such as  , constructed with the abbreviation of the goalkeeper (GK) and its pronunciation ゴールキーパー (gōrukīpā). Translative/contrastive ateji refers to kanji paired with a foreign-language reading to contrast with the kanji, and it delivers a sense of foreignness, such as in the case of translative ateji with the tension provided by contrastive ateji. The foreign characteristics of the unfamiliar words in this category are important and exist outside everyday vocabulary (Lewis Citation2010, 34). For example, the ateji

, constructed with the abbreviation of the goalkeeper (GK) and its pronunciation ゴールキーパー (gōrukīpā). Translative/contrastive ateji refers to kanji paired with a foreign-language reading to contrast with the kanji, and it delivers a sense of foreignness, such as in the case of translative ateji with the tension provided by contrastive ateji. The foreign characteristics of the unfamiliar words in this category are important and exist outside everyday vocabulary (Lewis Citation2010, 34). For example, the ateji  is constructed with 暗号 (angō; “code”) and loanword スペル (superu; “spell”).

is constructed with 暗号 (angō; “code”) and loanword スペル (superu; “spell”).

3.3. Kaindl’s (Citation1999) translation procedures

Kaindl (Citation1999) proposed performing several procedures when translating comics/manga: repetition, deletion, detraction, addition, transmutation, and substitution. Repetition (repetitio) refers to “source language, typography or picture elements that are taken over in their identical form,” while size enlargement and the reduction of pictorial elements depend on the publisher’s decision. Deletion (deletio) refers to “the removal of text or pictures,” while detraction (detractio) concerns “parts of linguistic/pictorial/typographic elements that are omitted in the translation.” At the pictorial level, this procedure often involves retouching pictures to comply with censorship regulations. Addition (adiectio) refers to “operations in which linguistic/pictorial material which was not there in the original is added in the translation to replace or supplement the source material,” and transmutation (transmutatio) pertains to “a change in the order of source language or source pictorial elements.” Lastly, substitution (substitutio) includes “translation procedures in which the original linguistic/typographic/pictorial material is replaced by more or less equivalent material.” Kaindl (Citation1999, 284) also mentioned that “different translation strategies can be applied to individual elements within the same panel.” Kaindl’s procedures are significant since not only are they the first recommended practices for comics/manga translation, but they can also cater to linguistic as well as typographical, and pictorial elements. By applying Kaindl’s (Citation1999) translation procedures, this study examines how the meanings of ateji are constructed into the target language.

4. Data and methodology

This study’s data consisted of six Japanese manga and their respective Malay translations. The source texts were ドラゴンボール 巻43 “バイバイドラゴンワールド” (Citation1995), ワンピース巻四十九 “ナイトメア・ルフィ” (Citation2008a), ワンピース巻五十 “再び辿りつく” (Citation2008b), ワンピース巻ハ十 “開幕宣言” (Citation2015), ワンピース巻ハ十一 “ネコマムシの旦那に会いに行こう” (Citation2016a), published by Shueisha Inc., and 君の名は01 (Citation2016a), published by the Kadokawa Corporation. Meanwhile, the target texts were Dragon Ball Mutiara Naga 43 Jumpa Lagi Mutiara Naga (Citation1998), Budak Getah 49 Mimpi Ngeri Luffy (Citation2008c), Budak Getah 50 Ketibaan Sekali Lagi (Citation2008d), Budak Getah 80 Perisytiharan Permulaan Baru (kaimaku sengen) (Citation2016b), Budak Getah 81 Pergi Berjumpa dengan Tuan (master) Nekomamushi (Citation2016c), published by Comics House Sdn. Bhd., and NAMAMU … 01 (Citation2016b), published by Kadokawa Gempak Starz Sdn. Bhd. The above-mentioned manga was selected because of their demonstrated use of ateji.

This study adopted a qualitative content analysis approach. Before identifying the types of ateji used in the data, content analysis was first conducted based on Bezemer and Kress’s (Citation2016) types of modes to identify those used by manga to create meaning. Subsequently, ateji forms were first determined based on Lewis’s (Citation2010) categories. The identified ateji and the translations were then examined to determine the procedures that manga translators followed to use the multiple modes in manga for reconstructing the meaning of ateji in the target social semiotic context. Finally, the effective modes that can be used to translate ateji were identified.

5. Data analysis and findings

5.1. Modes in manga

In the social semiotic multimodal approach, the modes used to create meaning in communication are speech, writing, image, gaze, gesture, and layout (Bezemer and Kress Citation2016). Content analysis on source texts showed that manga, like printed media, does not have the mode of speech. Nevertheless, findings indicated that manga authors use different typefaces and speech balloons to convey acoustic features. For instance, different typefaces represent different characters’ dialogues, sound effects (known as giongo/gitaigo in the manga) are drawn with different styles and lines that symbolise different acoustic features, and speech balloons with varying shapes/lines denote sound characteristics (e.g. a jagged line conveys shouting). These findings showed that despite the presence of acoustic elements in the manga, their function is realised through the mode of image and typography. Moreover, the characters’ gaze and gestures are depicted through illustrations, indicating that in manga both function as semiotic resources under the mode of the image. In addition, manga has the mode of layout, but it is different from that of Western comics, with its reading flow being from right to left. In brief, meaning–making in manga involves four modes: writing, image, typography, and layout. Section 5.3 discusses the transfer of meaning between these modes during ateji translation along with the concepts of transformation and transduction. It is worth pointing out that the four modes complement each other as multimodal ensembles in meaning–making. As layout mode and its semiotic resource’s “reading direction” do not undergo any changes during the translation process, they are not included in the discussion.

5.2. Forms of ateji

The content analysis of the source text showed that Lewis’s (Citation2010) five forms of ateji were used to convey different meanings. The occurrences for each form are shown in .

Table 1. Occurrences of the five types of ateji.

The following section discusses the translations of the five forms of ateji. Examples are provided to illustrate ateji and their translation and how manga translators used multiple modes in the manga to remake the meaning conveyed by ateji into the target language. The Japanese source text is marked (a), and the Malay translation (b).

5.3. Ateji translation

5.3.1. Translative ateji

The analysis revealed that among all the ateji, translative ateji occurred most frequently and was used to convey the following elements: fighting tactics, the names of a character/a group of characters, the names of a place, and nouns and adjectives.

5.3.1.1. Fighting tactics

In One Piece, the sign maker used ateji to name these fighting tactics and thus convey multiple layers of meaning. The analysis revealed that translations published in the 2010s conveyed more complete meanings than those released in the 2000s because of the different use of multimodal resources to reconstruct meaning. Examples 1 and 2 below prove this point.

Example 1

Table

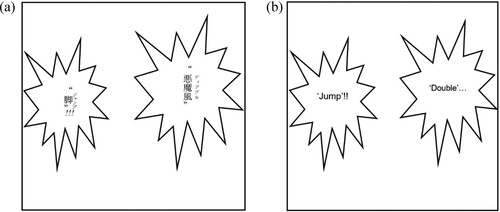

The image mode of Example 1 () shows that a character named Sanji is performing a fighting tactic while his left leg is on fire. The jagged speech balloons – the semiotic resource of the image mode – display ateji  . This multimodal ensemble shows Sanji shouting the tactic’s name, which is a translative ateji constructed with kanji 悪魔風脚 (akumafū ashi; “devil-liked leg”) and a furigana ディアブルジャンブ (diaburu janbu) as its pronunciation. By using this tactic, Sanji heats his leg, enabling his kicks to have greater impact and burn his opponents; thus, the “devil-liked leg” reflects the power of this tactic. The furigana “diaburu janbu” are French loanwords, “Diable Jambe”, meaning “devil leg” and they may hint at Sanji’s French-speaking origin, conveying a sense of foreignness. Readers who know French can also understand the meaning.

. This multimodal ensemble shows Sanji shouting the tactic’s name, which is a translative ateji constructed with kanji 悪魔風脚 (akumafū ashi; “devil-liked leg”) and a furigana ディアブルジャンブ (diaburu janbu) as its pronunciation. By using this tactic, Sanji heats his leg, enabling his kicks to have greater impact and burn his opponents; thus, the “devil-liked leg” reflects the power of this tactic. The furigana “diaburu janbu” are French loanwords, “Diable Jambe”, meaning “devil leg” and they may hint at Sanji’s French-speaking origin, conveying a sense of foreignness. Readers who know French can also understand the meaning.

Figure 1. (a) ワンピース巻四十九 (Citation2008c, 139); (b) Budak Getah 49 (Citation2008c, 139).

In the target text, the ateji is substituted as “Double” … “Jump,” assuming that Malay readers can understand English. With the complementary image mode, it is easy for readers to understand that it is a tactic name; however, the meaning of the kanji, French words, and Sanji’s French origin is lost in translation. In terms of semiotic change in meaning–making, a partial transformation as only one meaning (tactic name) can be conveyed through the writing mode in the target text. Thus, the detraction procedure was also adopted. Example 2 shows another fighting tactic name in One Piece, published in the 2010s.

Example 2

Table

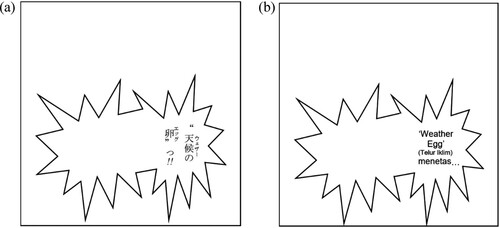

The image mode of Example 2 () shows a cracked eggshell floating in the stormy sky and Nami using a wand that points to the sky. There are two combined jagged speech balloons. The writing mode in one of them shows ateji  . It is a translative ateji constructed with kanji 天候の卵 (tenkō no tamago) and furigana ウェザーエッグ (uezā eggu) as its pronunciation. The kanji means “climate egg,” while “uezā eggu” are English loanwords that refer to “weather egg.” The use of ateji as part of the multimodal ensembles in this panel not only tells readers the tactic name but also hints at Nami’s English-speaking origin concisely.

. It is a translative ateji constructed with kanji 天候の卵 (tenkō no tamago) and furigana ウェザーエッグ (uezā eggu) as its pronunciation. The kanji means “climate egg,” while “uezā eggu” are English loanwords that refer to “weather egg.” The use of ateji as part of the multimodal ensembles in this panel not only tells readers the tactic name but also hints at Nami’s English-speaking origin concisely.

Figure 2. (a) ワンピース巻ハ十一 (Citation2016c, 17); (b) Budak Getah 81 (Citation2016c, 17).

In the Malay translation, the furigana is substituted with the English original words “Weather Egg,” and the kanji is translated literally as “Telur Iklim” (climate egg) with smaller font size (semiotic resources of the mode of typography) in gloss form. This multimodal ensemble already conveys the closest meanings. However, an extra word, “menetas … ” (hatches …) is inserted, and it is believed that such added sense of hatching is interpreted from the cracked eggshell image. This approach shows that instead of the transformation of ateji’s meaning in the writing mode, transduction takes place when the meaning of “hatches,” conveyed through the image mode in the source text, is changed to be transmitted through the image and writing modes in the target text.

5.3.1.2. Name of a character/a group of characters

Example 3

Table

The image mode of Example 3 () shows a group of characters. An inscription,  , interacts with the image mode to tell the readers the group name of these characters.

, interacts with the image mode to tell the readers the group name of these characters.  is a translative ateji constructed with the kanji 侠客団 (kyōkaku-dan) that means “a group of people who acting under the pretence of chivalry while participating in gangs” (Weblio Citation2021) and an English loanword ガーディアンズ (gādianzu) that refers to “guardians” – the nocturnal combat force of the Mokomo Dukedom. While “kyōkaku-dan” has the connotation of lawless, mafia-like behaviour, “gādianzu” conveys the main duty of this group, namely guarding the dukedom. Thus, the ateji conveys the appearance of this group (humanoid with animal features) and their roles as well as adding a sense of foreignness.

is a translative ateji constructed with the kanji 侠客団 (kyōkaku-dan) that means “a group of people who acting under the pretence of chivalry while participating in gangs” (Weblio Citation2021) and an English loanword ガーディアンズ (gādianzu) that refers to “guardians” – the nocturnal combat force of the Mokomo Dukedom. While “kyōkaku-dan” has the connotation of lawless, mafia-like behaviour, “gādianzu” conveys the main duty of this group, namely guarding the dukedom. Thus, the ateji conveys the appearance of this group (humanoid with animal features) and their roles as well as adding a sense of foreignness.

Figure 3. (a) ワンピース巻ハ十一 (Citation2016c, 58); (b) Budak Getah 81 (Citation2016c, 58).

In the target text, the kanji is substituted as Kumpulan Pendekar (swordsman group) conveys the group’s guarding role but not the lawless, mafia-like behaviour. The furigana is substituted with its original language as “GUARDIANS” and also as “Gaadianzu” in gloss with smaller font size. This multimodal ensemble reflects a transformation with addition.

5.3.1.3. Name of a place

Example 4

Table

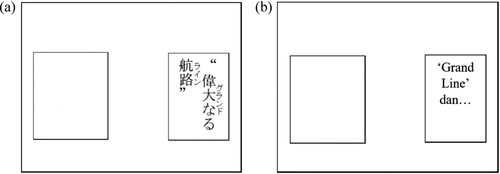

The writing mode in Example 4 () shows two narrations of names of places in two speech balloons that look like signboards. The narration interacts with the image mode, which shows a sky with clouds and sea to convey information on the location. The first narration,  , is a translative ateji that is formed with the kanji 偉大なる航路 (idai naru kōro) and loanwords グランドライン (gurando rain) in furigana as the ateji’s pronunciation. The kanji conveys the meaning of “grand nautical route,” while the furigana conveys the proper name of the nautical route that is “Grand Line” and is substituted with “Grand Line” in the target text. This substitution causes the meaning of “nautical” to only be understood through image mode; thus, detraction occurs, and meanings undergo partial transformation.

, is a translative ateji that is formed with the kanji 偉大なる航路 (idai naru kōro) and loanwords グランドライン (gurando rain) in furigana as the ateji’s pronunciation. The kanji conveys the meaning of “grand nautical route,” while the furigana conveys the proper name of the nautical route that is “Grand Line” and is substituted with “Grand Line” in the target text. This substitution causes the meaning of “nautical” to only be understood through image mode; thus, detraction occurs, and meanings undergo partial transformation.

Figure 4. (a) ワンピース巻五十 (Citation2008d, 32); (b) Budak Getah 50 (Citation2008d, 32).

5.3.1.4. Noun and adjective

Example 5

Table

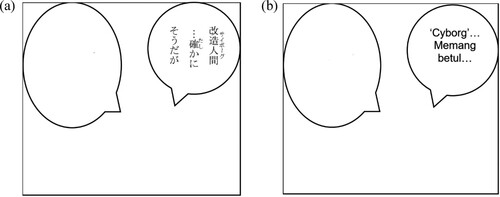

The findings show that some nouns and adjectives use translative ateji. In Example 5 (), the image mode shows a character named Pacifista and two speech balloons pointing at him. He is telling Sanji that he is a Cyborg – albeit different from Franky. A translative ateji,  , is used which combines kanji 改造人間 (kaizō ningen) and the loanword サイボーグ (saibōgu) in furigana as pronunciation. While “kaizō ningen” refers to a human being whose body is reconstructed (Weblio Citation2021), “saibōgu” (cyborg) is “a creature that is part human, part machine” (Oxford Learner’s Dictionaries Citation2021). These dictionary definitions convey quite similar meanings; however, as Pacifista says, he is different from Franky as in the manga he has lost his humanity, while Franky retains it.

, is used which combines kanji 改造人間 (kaizō ningen) and the loanword サイボーグ (saibōgu) in furigana as pronunciation. While “kaizō ningen” refers to a human being whose body is reconstructed (Weblio Citation2021), “saibōgu” (cyborg) is “a creature that is part human, part machine” (Oxford Learner’s Dictionaries Citation2021). These dictionary definitions convey quite similar meanings; however, as Pacifista says, he is different from Franky as in the manga he has lost his humanity, while Franky retains it.

Figure 5. (a) ワンピース巻五十 (Citation2008d, 75); (b) Budak Getah 50 (Citation2008d, 75).

In the manga, the sign maker also uses ateji  , constructed by kanji 鉄人 (tetsujin; “iron man”) and furigana サイボーグ (saibōgu; “cyborg”) to refer to Franky. Hence, it appears that the sign maker uses “cyborgs” to refer to all “part human, part machine” but differentiates their possession of humanity with different kanji. In the Malay translation, the ateji is substituted with “cyborg,” confirming the occurrence of a partial transformation in which the differences in the possession of humanity conveyed through 改造人間 are detracted.

, constructed by kanji 鉄人 (tetsujin; “iron man”) and furigana サイボーグ (saibōgu; “cyborg”) to refer to Franky. Hence, it appears that the sign maker uses “cyborgs” to refer to all “part human, part machine” but differentiates their possession of humanity with different kanji. In the Malay translation, the ateji is substituted with “cyborg,” confirming the occurrence of a partial transformation in which the differences in the possession of humanity conveyed through 改造人間 are detracted.

5.3.2. Denotive ateji

Example 6

Table

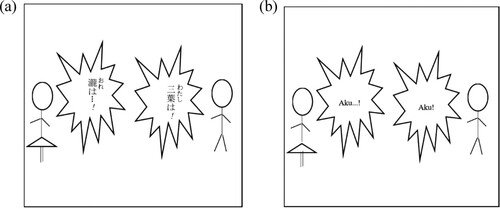

In the manga  , the male lead 瀧 (Taki) and the female lead 三葉 (Mitsuha) occasionally experience body-swapping. The author uses denotive ateji to show the characters’ real identities. In Example 6 (), the image mode shows two speech balloons directed at Taki and Mitsuha, who have swapped bodies and are saying “I” at the same time. The ateji

, the male lead 瀧 (Taki) and the female lead 三葉 (Mitsuha) occasionally experience body-swapping. The author uses denotive ateji to show the characters’ real identities. In Example 6 (), the image mode shows two speech balloons directed at Taki and Mitsuha, who have swapped bodies and are saying “I” at the same time. The ateji  is used in Taki’s dialogue, and the ateji

is used in Taki’s dialogue, and the ateji  is used in Mitsuha’s dialogue to indicate that they have exchanged bodies. The kanji are proper nouns (the characters’ names), while the furigana are pronouns, おれ (ore) and わたし (watashi), both of which refer to “I.” The difference between the two pronouns is that おれ (ore) is used by a male to refer to himself as “I,” while わたし (watashi) is a neutral pronoun normally used by a female for the same purpose. The use of the two denotive ateji can describe the relationships between characters and indicates their identities (Lewis Citation2010). Both ateji are substituted with “Aku” in the Malay translation, which is a casual and gender-neutral reference to “I” as the Malay language has no gendered first-person pronouns. The characters’ names are detracted, causing a partial transformation as their real identities, which could easily be understood through the mode of writing, are no longer available in the target text.

is used in Mitsuha’s dialogue to indicate that they have exchanged bodies. The kanji are proper nouns (the characters’ names), while the furigana are pronouns, おれ (ore) and わたし (watashi), both of which refer to “I.” The difference between the two pronouns is that おれ (ore) is used by a male to refer to himself as “I,” while わたし (watashi) is a neutral pronoun normally used by a female for the same purpose. The use of the two denotive ateji can describe the relationships between characters and indicates their identities (Lewis Citation2010). Both ateji are substituted with “Aku” in the Malay translation, which is a casual and gender-neutral reference to “I” as the Malay language has no gendered first-person pronouns. The characters’ names are detracted, causing a partial transformation as their real identities, which could easily be understood through the mode of writing, are no longer available in the target text.

Figure 6. (a) 君の名は01 (Citation2016b, 128); (b) NAMAMU … 01 (Citation2016b, 128).

5.3.3. Contrastive ateji

5.3.3.1. Fighting tactic

Example 7

Table

This study found that a fighting tactic was also conveyed through contrastive ateji. The image in Example 7 () shows that the lead character, Luffy, is fighting with an antagonist named Oars. He is using a tactic called  (Gomu Gomu no Ono), and the jagged speech balloon displays part of the tactic name,

(Gomu Gomu no Ono), and the jagged speech balloon displays part of the tactic name,  . It is a contrastive ateji constructed with the kanji 戦斧 (senpu; “battle axe”) and the furigana オノ (ono; “axe”). While オノis written as 斧 (ono) in kanji, the word 斧 in 戦斧 is pronounced as “pu,” although it is a similar kanji. This is because 斧 is combined with戦 (sen), which then form a multi-kanji compound word that needs to be pronounced according to the 音読み (onyomi), the Chinese style of reading. “Ono” is the Japanese reading. The similar meaning component “axe” narrows down the meanings of the ateji to facilitate readers’ understanding of the battle axe as a type of axe. The partial transformation occurred in the target text as the substitution of the axe does not convey the meaning of battle possessed by the kanji 戦 (sen); thus, detraction is also applied.

. It is a contrastive ateji constructed with the kanji 戦斧 (senpu; “battle axe”) and the furigana オノ (ono; “axe”). While オノis written as 斧 (ono) in kanji, the word 斧 in 戦斧 is pronounced as “pu,” although it is a similar kanji. This is because 斧 is combined with戦 (sen), which then form a multi-kanji compound word that needs to be pronounced according to the 音読み (onyomi), the Chinese style of reading. “Ono” is the Japanese reading. The similar meaning component “axe” narrows down the meanings of the ateji to facilitate readers’ understanding of the battle axe as a type of axe. The partial transformation occurred in the target text as the substitution of the axe does not convey the meaning of battle possessed by the kanji 戦 (sen); thus, detraction is also applied.

Figure 7. (a) ワンピース巻四十九 (Citation2008c, 181); (b) Budak Getah 49 (Citation2008c, 181).

5.3.3.2. Noun

Example 8

Table

A noun in contrastive ateji form has also been identified. The image in Example 8 () shows a ship in rough seas. Again, the jagged speech balloons and the writing in them show somebody shouting that a storm is coming.  is a contrastive ateji constructed with the kanji 大嵐 (ōarashi; “raging storm”) and the furigana オオシケ (ōshike; “very stormy weather at sea”) (Weblio Citation2021). While “ōshike” conveys a more specific reference to nautical affairs, “ōarashi” does not; thus, the interaction between both the kanji and the furigana broadens the meaning and conveys a terrible storm and rough sea. In the target text, the contrastive ateji is substituted and detracted as “badai,” which refers to a storm (PRPM Citation2021). Because it does not convey the nautical affair, the partial transformation of meaning takes place in the target text.

is a contrastive ateji constructed with the kanji 大嵐 (ōarashi; “raging storm”) and the furigana オオシケ (ōshike; “very stormy weather at sea”) (Weblio Citation2021). While “ōshike” conveys a more specific reference to nautical affairs, “ōarashi” does not; thus, the interaction between both the kanji and the furigana broadens the meaning and conveys a terrible storm and rough sea. In the target text, the contrastive ateji is substituted and detracted as “badai,” which refers to a storm (PRPM Citation2021). Because it does not convey the nautical affair, the partial transformation of meaning takes place in the target text.

Figure 8. (a) ワンピース巻五十 (Citation2008d, 131); (b) Budak Getah 50 (Citation2008d, 131).

5.3.4. Abbreviation/contrastive ateji

Example 9

Table

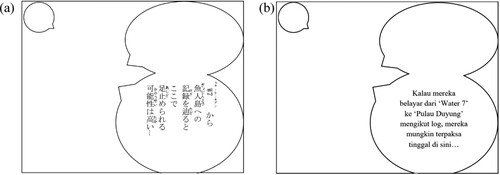

The image mode in Example 9 () shows two characters having a conversation. One of the speech balloons contains an abbreviation/contrastive ateji  , which does not involve kanji but is constructed in the form of ateji with the abbreviation W7 and the furigana ウォーターセブン (u∼ōtā sebun; “water seven”).

, which does not involve kanji but is constructed in the form of ateji with the abbreviation W7 and the furigana ウォーターセブン (u∼ōtā sebun; “water seven”).  is a proper name that refers to a place in the story, and the ateji could communicate how the place is part of the nautical-like strategic routine and has a military-like connotation. It also enables quick reading (Lewis Citation2010). By translating

is a proper name that refers to a place in the story, and the ateji could communicate how the place is part of the nautical-like strategic routine and has a military-like connotation. It also enables quick reading (Lewis Citation2010). By translating  as Water 7, the translator substitutes “u∼ōtā” with its English spelling “water” and “sebun” with the number “7,” although the abbreviation W7 is detracted. This procedure causes the target text to lose the impression of a military-like context. Moreover, the translation no longer retains the sign maker’s intention to provide quick reading; thus, a partial transformation occurs.

as Water 7, the translator substitutes “u∼ōtā” with its English spelling “water” and “sebun” with the number “7,” although the abbreviation W7 is detracted. This procedure causes the target text to lose the impression of a military-like context. Moreover, the translation no longer retains the sign maker’s intention to provide quick reading; thus, a partial transformation occurs.

Figure 9. (a) ワンピース巻四十九 (Citation2008c, 81); (b) Budak Getah 49 (Citation2008c, 81).

5.3.5. Translative/contrastive ateji

Example 10

Table

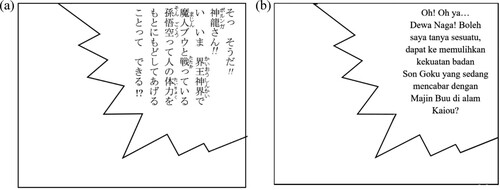

The findings reveal that translative/contrastive ateji is used to convey the character’s name and a made-up word. Examples 10 and 11 are such cases. The image in Example 10 () shows a character named Dende asking Porunga (a wish-granting dragon in Dragon Ball) to restore Son Goku’s strength. The image in this panel only displays Porunga’s body, while the previous panel shows Porunga’s face. In Dende’s speech balloon, the ateji  is used, constructed with the kanji 神龍 (shinryū; “dragon god”) and the furigana ポルンガ (Porunga). In the manga, Porunga is from planet Namek and uses the Namekian language to grant wishes. Thus, the name Porunga is Namekian, a language created in the manga. The furigana complements the kanji to help readers differentiate the wish-granting dragons in Dragon Ball as there are a few with different names in the story, namely Shenron, Porunga, and Super Shenron.

is used, constructed with the kanji 神龍 (shinryū; “dragon god”) and the furigana ポルンガ (Porunga). In the manga, Porunga is from planet Namek and uses the Namekian language to grant wishes. Thus, the name Porunga is Namekian, a language created in the manga. The furigana complements the kanji to help readers differentiate the wish-granting dragons in Dragon Ball as there are a few with different names in the story, namely Shenron, Porunga, and Super Shenron.

Figure 10. (a) ドラゴンボール 巻43 (Citation1995, 125); (b) Dragon Ball Mutiara Naga 43 (Citation1998, 125).

In the target text, the kanji 神 (shin) is not translated as “Tuhan,” the literal equivalent of “god;” rather, it is substituted with “Dewa” (spirits worshipped by people). This substitution is different in meaning and believed to be related to the concept of monotheism in Islam (Malaysia’s official religion); here, the translator/publisher seems to be avoiding controversy. It is worth noting that although specific terms in Islam that are not allowed to be used in publications other than Islamic ones are stated in Malaysia’s publication guidelines, “Tuhan” is not (see MOHA Citation2017). Thus, it can be said that the substitution was prompted by the translators’/publishers’ agency and interest in the evaluation of social acceptability. In addition, the kanji 龍 (ryū) is substituted with “Naga” (dragon), while the furigana ポルンガ (Porunga) is detracted. The detraction of Porunga in the writing mode may cause readers to remain unaware of the existence of different wish-granting dragons in Dragon Ball if they are not familiar with them; hence, a partial transformation occurs during translation.

Example 11

Table

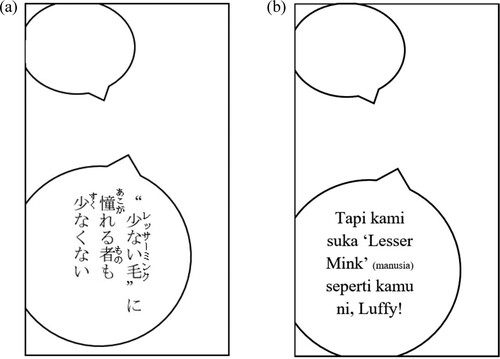

In One Piece, the Minks are a tribe of fur-covered mammalian humanoids with animal features. The image mode in Example 11 () shows Wanda, one of the Minks, licking Luffy’s face. In the dialogues, Wanda tells Luffy that the Mink tribe likes  , which is a made-up word used by the tribe to refer to human beings. It is a translative/contrastive ateji constructed with the kanji 少ない毛 (sukunai ke; “less hair”) and the furigana レッサーミンク (ressā minku; “lesser mink”). The dictionary definition of “mink” is “a small wild animal with thick shiny fur, a long body, and short legs. Mink are often kept on farms for their fur” (Oxford Learner’s Dictionaries Citation2021). Through this definition, the sign maker of the manga seems to have broadened its meaning by contrasting it with “sukunai ke” to refer to human beings with no fur but with hair, as opposed to the Mink tribe in the manga. This initiative also reveals that the author used ateji to create a new word to show the unique language usage of the Mink tribe.

, which is a made-up word used by the tribe to refer to human beings. It is a translative/contrastive ateji constructed with the kanji 少ない毛 (sukunai ke; “less hair”) and the furigana レッサーミンク (ressā minku; “lesser mink”). The dictionary definition of “mink” is “a small wild animal with thick shiny fur, a long body, and short legs. Mink are often kept on farms for their fur” (Oxford Learner’s Dictionaries Citation2021). Through this definition, the sign maker of the manga seems to have broadened its meaning by contrasting it with “sukunai ke” to refer to human beings with no fur but with hair, as opposed to the Mink tribe in the manga. This initiative also reveals that the author used ateji to create a new word to show the unique language usage of the Mink tribe.

Figure 11. (a) ワンピース巻ハ十 (Citation2015, 202); (b) Budak Getah 80 (Citation2016b, 202).

In the target text, the translator only substitutes “ressā minku” with the original English spelling as “lesser mink,” without transferring the meaning of the kanji “less hair” into the target language. In addition, the aforementioned “human being,” which can be understood through the storyline and Luffy’s image, is translated as “manusia” (human being) in gloss form with smaller font size. Hence, the translation applied substitution, detraction, and addition. In terms of semiotic change, the addition of “manusia” is transduction from the image mode. A partial transformation of other meaning components also takes place.

6. Discussion

This study identified the five forms of ateji outlined by Lewis (Citation2010), who noted that translative/contrastive ateji is not a part of everyday vocabulary. Examples 10 and 11 illustrated this point, that is, the furigana of a translative/contrastive ateji can be constructed with a created language to signify the foreign identity of the created world. The substitution was found to be the most frequently used translation procedure, and it was used together with detraction (Examples 1, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10), addition (Example 3), and in combination with “literal translation and addition” (Example 2) and “detraction and addition” (Example 11) to form triplet procedures. It is significant to note that, among all the identified translation procedures, excluding addition, the substitution of furigana and literal translation of kanji as showed in Example 2 come closest to retaining the meaning of ateji. However, the weakness of this method is that the target text may be long, thus requiring a smaller font size to ensure that all meanings are conveyed through speech balloons with limited space. Some of the font sizes are too small to be read clearly and can be misinterpreted as a character speaking in a lower voice (McCloud, Citation2006). Thus, to address these issues, this study suggests that the phonetic guide in Microsoft Word can be utilised. Examples of ateji translated using the phonetic guide are (Example 2),

(Example 9), and

(Example 11). The adopted translation procedures are the literal translation of kanji, the repetition of abbreviation, and the substitution of furigana by spelling it out in alphabets. With the phonetic guide, one can translate the meaning and forms of ateji into the target text.

In comparison to ateji in translations published in the 1990s (Example 10), which are substituted with the Malay translation, and to ateji in translations published in the 2000s (Examples 1, 4, 5, 7, and 9), which are substituted with the English translation, a smaller font size – the semiotic resource of the typography mode – expands the potential of the modal affordance of the alphabetic writing system in the Malay language (the only one script) to complement other modes in conveying more complete meanings of ateji in translations published in the 2010s (Examples 2, 3, and 11). The change in interest and agency in using modes and semiotic resources also indicates a social change in the target society, which involves readers in the target context demanding the closest meaning as well as translators/publishers as interpreters of source text and sign makers of target text being more aware of expanding the affordances of existing modes to convey the closest meaning. The findings also showed that among all the motivated signs to convey the closest meaning of ateji to readers, typography and writing mode are perceived as effective. This is consistent with Huang and Archer’s (Citation2014) finding, in which the potential of mode in meaning–making is controlled by the mode user, who determines the most effective one to attract readers’ attention.

In terms of semiotic change, this study identified partial transformation (Examples 1, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10), transformation and transduction (Example 2), transformation with addition (Example 3), and partial transformation and transduction (Example 11). The partial transformation of an ateji’s meaning shows inadequate awareness of the importance of utilising multimodal ensembles to convey complete meaning; thus, such awareness must be improved. Transformation with addition and transformation and transduction indicate the agency and interest of the translators/publishers in assigning more salience to the writing mode; meaning that is conveyed through the image mode in the source text is now conveyed through both image and writing modes in the target text. However, it is worth noting that semiotic changes identified in this study do not aim to evaluate whether or not a translation is good, and the many factors underlying every translation decision must be examined in depth. Transformation and transduction, as well as their derivatives identified in this study, can help translators/publishers and manga translation researchers to systematically analyse meaning conveyed by each mode in multimodal text and understand how sign makers effectively use the available multimodal resources in their social context in translation.

7. Conclusion

This study examined how manga translators use different modes and semiotic resources available in the target social context to translate ateji. The research results showed that the phonetic guide, which possesses the affordance of writing mode and typography mode, is effective in reproducing the meaning and form of ateji into language with only one script – in this case, Malay. This study aims to contribute a feasible solution to ateji translation, providing a new perspective to explore solutions to translation problems using the social semiotic multimodal approach.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Yean Fun Chow

Yean Fun Chow is a senior lecturer at the Translation and Interpreting Studies Section, School of Humanities, Universiti Sains Malaysia. Her research interests include media translation, multimodality, Japanese translation, Chinese translation, and Cantonese translation.

References

- Abdolmaleki, Saleh Delforouz, Mansoor Tavakoli, and Saeed Ketabi. 2018. “Agency in Non-Professional Manga Translation in Iran.” The International Journal of Translation and Interpreting Research 10 (1): 92–110.

- Ali, Mohammad. 2015. “Analisis Penerjemahan Ateji dalam Komik Jepang ke dalam Bahasa Indonesia.” Master’s Thesis, Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia, Bandung.

- Armour, William Spencer, and Yuki Takeyama. 2015. “Translating Japanese Typefaces in ‘Manga’: Bleach.” New Readings 15: 21–45.

- Bezemer, Jeff, and Gunther Kress. 2016. Multimodality, Learning, and Communication: A Social Semiotic Frame. New York: Routledge.

- Borodo, Michal. 2015. “Multimodality, Translation and Comics.” Perspectives 23 (1): 22–41.

- Borodo, Michal. 2016. “Exploring the Links Between Comics Translation and AVT.” TranscUlturAl: A Journal of Translation and Cultural Studies 8 (2): 68.

- Fabbretti, Matteo. 2019. “Amateur Translation Agency in Action.” Translation Matters 1 (1): 46–60.

- Fujimura, Noriko. 2012. “音のない音を文字にすることのジレンマ—マンガにおける擬態語表現の翻訳分析から.” 文化環境研究 6: 62–71.

- Giovanni, Elena Di. 2008/2014. “The Winx Club as a Challenge to Globalization Translating from Italy to the Rest of the World.” In Comics in Translation, edited by Federico Zanettin, 345–366. London: Routledge. https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=AbNACwAAQBAJ&hl=zh_CN&pg=GBS.PP1.

- Gyllenfjell, Per. 2013. “Case Study of Manga Translation Problems.” Bachelor Thesis, Högskolan Dalarna University.

- Halliday, Michael AK. 1978. Language as Social Semiotic: The Social Interpretation of Language and Meaning. London: Arnold.

- Huang, Cheng-Wen, and Arlene Archer. 2014. “Fluidity of Modes in the Translation of Manga: the Case of Kishimoto’s Naruto.” Visual Communication 13 (4): 471–486.

- Inose, Hiroko. 2010. “マンガにみる擬音語・擬態語の翻訳手法.” 通訳翻訳研究への招待 10: 161–176.

- Jewitt, Carey. 2009. The Routledge Handbook of Multimodal Analysis. London: Routledge.

- Jewitt, Carey, Jeff Bezemer, and Kay O’Halloran. 2016. Introducing Multimodality. New York: Routledge.

- Jones, Jason Christopher, and Nadine Normand-Marconnet. 2016. “From West to East to West: A Case Study on Japanese Wine Manga Translated in French.” TranscUlturAl: A Journal of Translation and Cultural Studies 8 (2): 154–173.

- Jüngst, Heike Elisabeth. 2004. “Japanese Comics in Germany.” Perspectives 12 (2): 83–105.

- Jüngst, Heike Elisabeth. 2008/2014. “Translating Manga.” In Comics in Translation, edited by Federico Zanettin, 88–128. London: Routledge. https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=AbNACwAAQBAJ&hl=zh_CN&pg=GBS.PP1.

- Kaindl, Klaus. 1999. “Thump, Whizz, Poom.” Target International Journal of Translation Studies 11 (2): 263–288.

- Kaindl, Klaus. 2004. “Multimodality in the Translation of Humour in Comics.” In Perspectives on Multimodality, edited by Eija Ventola, Cassily Charles, and Martin Kaltenbacher, 173–192. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Lewis, Mia. 2010. “Painting Words and Worlds: The Use of Ateji in Clamp’s Manga.” Columbia East Asia Review 3:28–45.

- McCloud, Scott. 2006. Making Comics: Story Telling Secrets of Comics, Manga and Graphic Novels. New York: HarperCollins Publishers.

- Melander, Edvin. 2016. “Rubi-The Interlinear Poetic Gloss of Japanese.” Bachelor Thesis, Lunds Universitet.

- MOHA (Ministry of Home Affairs). 2017. “Garis Panduan Penerbitan di bawah Akta Mesin Cetak dan Penerbitan 1984 [AKTA 301].” Ministry of Home Affairs. Accessed May 23, 2021. https://www.moha.gov.my/images/maklumat_bahagian/PQ/Garis_Panduan_Penerbitan_2017.pdf.

- OLD. 2021. Oxford Learner’s Dictionaries. Accessed May 23, 2021. https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/.

- O'Hagan, Minako. 2007. “Manga, Anime and Video Games: Globalizing Japanese Cultural Production.” Perspectives 14 (4): 242–247.

- PRPM. 2021. Pusat Rujukan Persuratan Melayu. Accessed May 23, 2021. http://prpm.dbp.gov.my/.

- Rampant, James. 2010. “The Manga Polysystem: What Fans Want, Fans Get.” In Manga: An Anthology of Global and Cultural Perspectives, edited by Toni Johnson-Woods, 221–232. New York: The Continuum International Publishing Group.

- Rota, Valerio. 2008/2014. “Aspects of Adaptation. The Translation of Comics Formats.” In Comics in Translation, edited by Federico Zanettin, 129–157. London: Routledge. https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=AbNACwAAQBAJ&hl=zh_CN&pg=GBS.PP1.

- Sasahara, Hiroyuki. 2010. 当て字・当て読み漢字表現辞典. Tokyo: Sanseido Co. Ltd.

- Weblio. 2021. 英和辞典・和英辞典. Accessed May 23, 2021. http://ejje.weblio.jp/.

- Zanettin, Federico. 2008/2014. “The Translation of Comics as Localization. On Three Italian Translations of La Piste des Navajos.” In Comics in Translation, edited by Federico Zanettin, 316–344. London: Routledge. https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=AbNACwAAQBAJ&hl=zh_CN&pg=GBS.PP1.

- Zanettin, Federico. 2014. “Visual Adaptation in Translated Comic.” inTRAlinea 16: 1–34.

- Zanettin, Federico. 2018. “Translation, Censorship and the Development of European Comics Cultures.” Perspectives 26 (6): 868–884.

- Data

- Oda, Eiichiro. 2008a. ワンピース巻四十九‘ナイトメア・ルフィ’. Tokyo: Shueisha Inc.

- Oda, Eiichiro. 2008b. ワンピース巻五十‘再び辿りつく’. Tokyo: Shueisha Inc.

- Oda, Eiichiro. 2008c. Budak Getah 49 Mimpi Ngeri Luffy. Selangor: Comics House Sdn. Bhd.

- Oda, Eiichiro. 2008d. Budak Getah 50 Ketibaan Sekali Lagi. Selangor: Comics House Sdn. Bhd.

- Oda, Eiichiro. 2015. ワンピース巻ハ十‘開幕宣言’. Tokyo: Shueisha.

- Oda, Eiichiro. 2016a. ワンピース巻ハ十一‘ネコマムシの旦那に会いに行こう’. Tokyo: Shueisha.

- Oda, Eiichiro. 2016b. Budak Getah 80 Perisytiharan Permulaan Baru (Kaimaku Sengen). Selangor: Comics House Sdn. Bhd.

- Oda, Eiichiro. 2016c. Budak Getah 81 Pergi Berjumpa Dengan Tuan (Master) Nekpomamushi. Selangor: Comics House Sdn. Bhd.

- Shinkai, Makoto, and Ranmaru Kotone. 2016a. 君の名は 01. Tokyo: Kadokawa Corporation.

- Shinkai, Makoto, and Ranmaru Kotone. 2016b. NAMAMU … 01. Translated by uepinmon. Kuala Lumpur: Kadokawa Gempak Starz Sdn. Bhd.

- Toriyama, Akira. 1995. ドラゴンボール巻43‘バイバイドラゴンワールド’. Tokyo: Shueisha Inc.

- Toriyama, Akira. 1998. Dragon Ball Mutiara Naga 43 Jumpa Lagi Mutiara Naga. Selangor: Comics House Sdn. Bhd.