ABSTRACT

The last decades have seen the ideological transformations of graffiti and street art once constructed as criminal acts and associated with urban decay to being acceptable and profitable forms of commercial art. The spaces and places where these art forms are found have long transcended streets to art galleries and corporate advertising billboards and campaigns making them “the most visible forms of global urban culture and urban transgression” (Ferrell 2016, xxx; Bofkin 2014). This special issue on street art/art in the street explores street art's proliferation and complexity in different contexts as it relates to the political economy and neoliberal capitalism raising questions of social class, urban growth, cultural production, and consumerism. The themes investigated include notions of legality and illegality, regimes of visibility and invisibility, semiotic situated acts and art, ephemerality, permanence and mediatization, the political economy of place as well as the changing symbolic and economic value of street art tapping into issues of subcultural status and social class identities. This collection of papers draws on a range of theoretical frameworks and methodological approaches providing readers with interdisciplinary insights into the complex and changing nature of street art to account (and better understand) this social semiotic phenomena.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

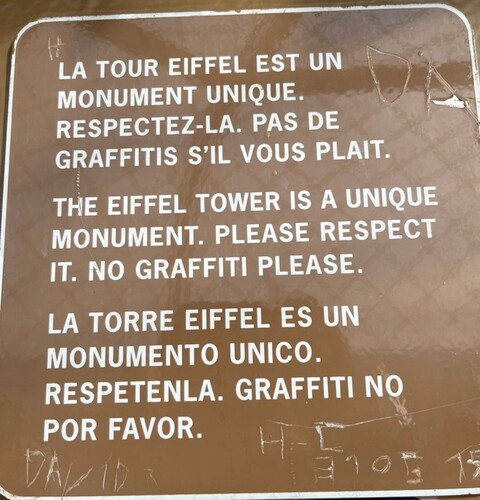

We open this special issue on Street Art – Semiotics, Politics, and the Economy with a multilingual and rather unexpected sign that Kellie recently encountered at the Eiffel Tower in Paris, France in the Spring of 2022. By making the overt claim to visitors that the tower is “unique” and should therefore be “respected” the sign inexplicitly classifies graffiti as vandalism, detrimental and therefore also unwelcome. This is an interesting and powerful (if not pretentious) discursive move juxtapositioning different perceptions of what may be classified as “gaze worthy” and perhaps even as “art.” The Eiffel Tower is indeed a symbolic icon of Paris and by extension, of France that was originally built for the 1889 World’s Fair and thus intended for temporary viewing. It has since become a permanent fixture within the city’s semiotic landscape and an international architectural wonder admired globally by many ().

To have this structure “tagged” or “bombed” would no doubt be deemed as “damaging” a historical monument and polluting visual space for the sign’s creators. At least, this is how one could interpret this rather “polite” request given the repetitive use of “please” in the sign and perhaps another unexpected instance of language use. In contrast, graffiti writers might see the tower as a space for public display imbued with a high regime of visibility, given how many people pass through there on a daily (and annual) basis. Nevertheless, during Kellie’s visit, there was no graffiti to be found, just a few inscriptions consisting of letters, numbers, and what appeared to be symbols on the sign. While these engraved inscriptions are illegible, their unsanctioned marking and physical emplacement are nevertheless noteworthy and could be interpreted as an explicit visual reply/message that is there to stay (so long as the sign remains) despite its ambiguous meaning to the sign authors and wider audience functioning as a semiotic trespass in social and normative spatial terms (Young Citation2014). This example highlights many of the themes that are explored in this special issue, some of which include notions of legality and illegality, regimes of visibility and invisibility, semiotic situated acts and art, ephemerality, permanence and mediatization, the political economy of place as well as the changing symbolic and economic value of street art tapping into issues of subcultural status and social class identities.

The semiotic prominence of street art

While the marking and drawing of public surfaces have been taking place since Graeco-Roman antiquity (Coulmas Citation2009; Eastmond Citation2015; Petrucci ([Citation1980] Citation1993); Ferrell Citation2016; Baird and Taylor Citation2016), the prominence of graffiti and street art have emerged within the past 50 years or so. The historical development and issues surrounding graffiti and street art began in the US in the 1970s and are predominately associated with African American and Latino urban youth cultures in the streets of Philadelphia and New York City. According to Iveson (Citation2010), both peaked in the 1980s and began proliferating throughout metropolitan centers to other locales worldwide. Despite being a “local” practice and localized form of public address that has become international in spite of efforts of urban authorities to eradicate its placement in the streets, primarily on walls, buildings or moving trains (Pennycook Citation2007, Citation2010; Campos Citation2016; Karlander Citation2019; Iveson Citation2010; Kramer Citation2010, Citation2022; Fernandez-Barkan Citation2022), both graffiti and street art raise relevant questions about ideologies of aesthetics and individual rights to city spaces. Ideologies of aesthetics are navigated by socio-cultural trends highly influenced by (elite) social class tastes (Bourdieu Citation1984) while individuals’ rights are largely determined by powerful social actors involved in shaping and place-making practices on the local, regional, national, and even global levels, which in turn are regulated by the political economy.

In the last decades, we have seen the ideological transformations of graffiti and street art, once constructed as criminal acts and associated with urban decay to being acceptable and profitable forms of commercial art. The spaces and places in which these art forms are found have long transcended streets to art galleries and corporate advertising billboards and campaigns making them “the most visible forms of global urban culture and urban transgression” (Ferrell Citation2016, xxx; Bofkin Citation2014). For Ferrell, this deems graffiti and street art both complex and confusing resulting in among other things, “the very impossibility in defining them” (Citation2016, xxxi). It is not our intention to define graffiti or street art here, an ongoing debate (see McAuliffe Citation2012; Blanché Citation2015; Ross Citation2016; Avramides and Tsilimpounidi Citation2017; Campos, Zaimakis, and Pavoni Citation2021), but to explore its proliferation and complexity in different contexts as it relates to the political economy and neoliberal capitalism raising questions of social class, urban growth, cultural production, and consumerism.

The political economy of place

Scholars in sociology, cultural geography and the burgeoning field of linguistic/semiotic landscapes have pointed out that street art plays a key role, together with other semiotic resources, in the branding and marketing of specific places – be they neighborhoods, entire cities and even rural areas (Zukin Citation1995, Citation2011; Pennycook Citation2010; Schachter Citation2014; Muth Citation2016; Ross Citation2016; Gonçalves Citation2018, Citation2019; Järlehed Citation2017; Trinch and Snadjr Citation2020; Jaworski and Gonçalves Citation2022).

For Goldman and Papson (Citation2006, 328), “it sometimes seems as if there is hardly any market arena, not even a niche, that has been left uncolonized by branding processes [where] branding represents one institutionalized method of practically materializing the political economy of signs.” Street art as a polysemic sign is no exception when it comes to the branding of place (Gonçalves Citation2019) within the political economy of urban life, what economist theorists have referred to as “consumption-driven urban development” (Markusen and Schrock Citation2006). This entails massive visual changes within urban landscapes by means of replacement through revitalization and gentrification processes especially as it pertains to former zones and neighborhoods of industrial production (Franzén et al. 2010; Trinch and Snadjr Citation2020; Snadjr and Trinch Citation2022). Such processes are “densely connected into the circuits of global capital and cultural circulation” concerned with capitalist production rather than social reproduction (Lees Citation2003, 2490) indexing the socio-economic inequalities among neighborhood residents, many of whom are racial and ethnic minorities, who, because of revitalization processes (and increased housing prices) get geographically displaced. The new political economy of urban life has no doubt been instigated by neoliberal policies where urban development is largely financed privately for economic profit (see Kramer Citation2022) and where new cultural and semiotic landscapes of cities are in global competition with one another.

The model of “growth machines” within the political economy of place (Molotch Citation1976) is helpful here as it has advanced our knowledge in terms of the commodification of place and the understanding that place commodification is fundamental to contemporary urban life and a prerequisite in any urban analysis of market societies. For Molotch (Citation1976), the city is regarded as a “growth machine” that serves the interests of a land-based elite consisting of private investors but also politically influential players. Landowners invest in their properties to reap growth-inducing resources, which contribute to the continuous growth cycle of urban hubs and neoliberal cities. In contrast to neoclassical economists (within sociology), Molotch (Citation1976) and later Logan and Molotch (Citation1987) attempt to understand and show how markets work as social phenomena rather than just “producers” and “consumers” whose relations are ordered by impersonal “laws” of supply and demand. For these scholars, the fundamental attributes of all commodities, including place, are social contexts through which they are used and exchanged. In quoting the work of Agha (Citation2011), Milani (Citation2022) reminds us that “nothing is always or only a commodity” (Agha Citation2011, 164) but indeed context-dependent. For Milani (Citation2022), “street art like any other form of visual manifestation in contemporary society is part and parcel of the ways in which global capitalism functions especially in neoliberal cities.” This resonates with twenty-first-century transitions in both the political and cultural economy and the emergence of the so-called creative class” (Florida Citation2002), which allows and encourages collaborations among advertising and street art industries, primarily in urban space (Borghini et al. Citation2010; Banet-Weiser Citation2011).

Within the context of cities, “various avant-garde movements have been synonymous with urban life” (Ley Citation2003, 2534), where artists (many of whom) reside, work, and showcase their artwork in urban areas attracting economic capital, investors, and policy makers (at various levels) paving the way for the re-appropriation of space. Such processes reverberate with Zukin’s (Citation1982) earlier notion of “the artistic mode of production,” where changes in neighborhoods are accomplished through artists’ symbolic appropriation of space. In other words, artists indirectly set the stage in attracting capital reinvestment, revitalization movements and gentrification processes. Artwork and revitalization processes often go hand in hand leading Markusen and Schrock (Citation2006, 1661) to talk about “artistic dividends,” which are the added value to both regional and local economies through means of artistic work. As cultural intermediaries, street artists themselves are aware of their role in these processes and express feelings of ambivalence, praising the expanding urban canvas and work opportunities that follow with urban growth, while they criticize consequences in terms of increased privatization and commercialization of public space, class stratification and the displacement of local communities (Anderson, Borg, and Ohlsson Citation2007; Romero Citation2018).

Within the context of street art, the production, consumption, display, and contestation of these processes are complex and often responses to the experience of public spaces as being “implicitly, structurally, forms of advertising, embodying the codes of socialization in the political economy” (Irvine Citation2012, 21). Indeed, semiotic changes in neighborhoods are inevitably tied to different socio-economic and political processes at various societal levels (ranging from the local, regional, national, and international), and their investigations give us a better understanding of the complex and dynamic ways in which particular instances of visual, multimodal and thus semiotic processes and productions such as street art can be deployed to re-appropriate space and valorize it (Järlehed Citation2022; Snadjr and Trinch Citation2022). This brings us to the issue of the political economy of signs and communication more broadly, to which we now turn.

The changing value of street art and the art market

In a now classic article entitled When talk isn’t cheap, Irvine theorized a political economic approach, one in which “the allocation of resources, the coordination of production, and the distribution of goods and services, seen (as they must be) in political perspective, involve linguistic forms and verbal practices in many ways” (Citation1989, 249). As Gal (Citation2016) explains in retrospect, a political economic perspective was the result of a shift in anthropological thinking from a view of language as purely denotative – a mirror of the social world and its inequalities – to an understanding of semiosis as performative, one which illustrates how semiotic practice, i.e. what we say, write and represent visually, on the one hand, and semiotic ideologies – what we believe about systems of significations (such as languages, visuality, etc.), and the values we ascribe to them – on the other hand, actively “produce social difference and inequality within and across interactions” (Graan Citation2016, 139).

In the case of graffiti and street art, a key ingredient in their valorization is their classification as art (see Wells Citation2016 for an overview). Bloch maintains that graffiti is a “performative art” (Citation2016, 446), and according to Halsey and Young (Citation2006, 276–277), it is an “affective process that does things to writers’ bodies (and the bodies of onlookers) as much as to the bodies of metal, concrete, and plastic, which typically compose the surfaces of urban worlds” (emphasis in original). For some scholars, its ephemeral, spontaneous and hidden nature becomes obscured and even delegitimatized when it becomes sanctioned by local, municipal, and regional authorities financially interested in making aesthetically pleasing city spaces with the hopes of contributing to the economic cycle and increased profit of “growth machines” (Molotch Citation1976).

Graffiti and street art contain ephemeral messages encompassing both identity and territorial claims often found in many forms, including protest, irony, humor, subversion, commentary, critique, an intervention, an individual or collective manifesto or simply an assertion of existence (Irvine Citation2012, 3; Taylor, Pooley, and Carragher Citation2016). Sanctioning such artistic processes may appear to diminish acts of transgression (by artists themselves) and be regarded as an act of “selling out” by peers within a particular subculture (Schachter Citation2014; Gonçalves Citation2019; Milani Citation2022; Pennycook Citation2022, but see Dickens Citation2010 for a counterargument). At the same time, such sanctioning functions as implicit ways in which behavior, space and art are both policed and controlled in a top-down fashion (Pennycook Citation2010; Bloch Citation2016). This differs, of course, from how sanctioned and commissioned work within the private sector has been viewed, leading to what Janis (Citation1983) has termed “Post-Graffiti” in his criticism of the gallerization of graffiti. In this way, graffiti and street art essentially become coopted and institutionalized by those outside the subcultures into the art world resulting not only in the evolution of the art market (Wells Citation2016; Weill Citation2022) but also the changing consequences for artists’ careers (Lachmann Citation1988; McRobbie Citation2004; Banet-Weiser Citation2011; Snyder Citation2016; Campos and Leal Citation2021).

The changing semantic and thus ideological labeling of graffiti and street art from illegal to sanctioned to commissioned to auctioned also represents its changing symbolic, market and thus economic value, which have even resulted in new linguistic coinages such as “Banksy-ed” (Reyburn Citation2021). Many readers may remember the 2018 scenario when Banksy’s “Girl with Balloon” picture sold for a record $ 1.4 million US dollars at Sotheby’s, which was subsequently shredded going viral for all the world to see. While the ideological stunt was intended to subvert the excess of the art trade, according to Banksy’s Instagram post (Reyburn Citation2021), it marked an epic historical moment for Banksy, street artists, and the art world in general by exponentially increasing the value of performance (street) art. According to a recent New York Times article, the half-shredded artwork was recently auctioned at Sotheby’s and re-sold for the price of $25.4 million US dollars (Reyburn Citation2021) indexing the “destruction of economic value for the sake of ‘an aristocratic measure of value’” (Baudrillard Citation1981, 106–107, italics in the original) inevitably connected to dominant social class tastes and signs of distinction.

Other readers may also remember the notorious incident of a Korean couple who defaced an abstract piece () of the well-known American graffiti artist JonOne that was worth some $400,000 (Kim and Ives Citation2021). Thinking that the piece was part of a public and participatory art project, the couple added a large splash of teal paint to the work igniting a heated debate about contemporary art globally and its inherent value. The CitationKorea JoongAng Daily, a local newspaper wrote a story about it entitled Graffitied Graffiti (2021), depicting the scandal and the mediation involved between the couple, the artist, and exhibition representatives with hopes of resolving the issue without legal action.

Civil lawsuits are not uncommon nowadays between artists and capitalism’s major players in how hegemonic constructions of value become normalized (Bonadio Citation2019; Kramer Citation2022). We are seeing this currently unfold in real time for artist Kristen Visbal and her iconic bronze sculpture Fearless Girl representing female empowerment and gender equality, which has been placed on the steps of the New York Stock Exchange and on view in the financial district since 2017 ().

Visbal is in a legal dispute surrounding issues of copyright and trademark agreements with State Street Global Advisors, the asset management firm, that commissioned and funded the sculpture (Small Citation2021). We believe such disputes extend well beyond the discourses depicting binaries of what counts as private and/or public street art centering on the realm of moral principles and politics where questions of ownership, culture, economy, materialism, symbolism, and power emerge resonating with well-known predicaments of social class theory (Bourdieu Citation1984, Citation1991; Kramer Citation2022). For some, street art has emerged as a new sign of cultural capital and thus a new signifier of social class distinction (Gonçalves Citation2022) where claims to eliteness are made (Thurlow and Jaworski Citation2012, Citation2017). This is the result of street art’s institutionalization, which has been shaped by complex socio-cultural, political, and economic process, including de-subculturalization and artification (Campos and Leal Citation2021; Shapiro and Heinich Citation2012) with regards to its changing market and aesthetic value, which not only shape but are also shaped by the field of cultural production (Bourdieu Citation1983, Citation1984, Citation1993) and highly influenced by global capitalism.

Mediatization

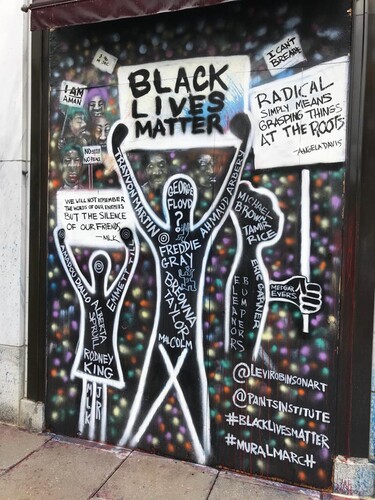

Del Percio et al. remind us that a political economic perspective requires paying attention to “the technologies and processes governing the valuation of resources” – both symbolic and material – “as well as their production, circulation, and consumption within a given place and at a specific moment in time” (Del Percio, Flubacher, and Duchêne Citation2017, 55). In the last year that we have been working on this special issue, we have also taken note about street art in the mass media that extend beyond its changing symbolic and thus economic and market value. We have read about the powerful effect (and affect) of street art in socio-political movements surrounding racial minorities such as Black Lives Matter in the US (Jacobs Citation2020) ( and ) to articles that explore the survival of the Afghan Art movement under the new Taliban regime (Hassan Citation2021) ().

Figure 6. Anti-corruption mural painted by the ArtLords artists groups with a school girl holding pens that was vandalized by Taliban fighters in Kandahar, Afghanistan. (Photo by Kiana Hayer New York Times Redux/Laif).

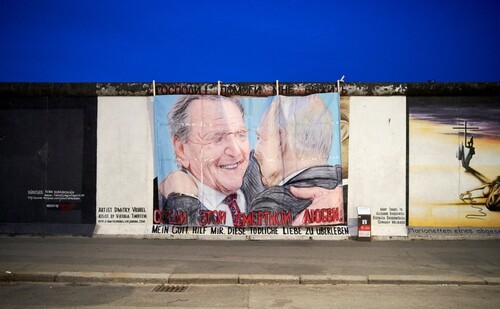

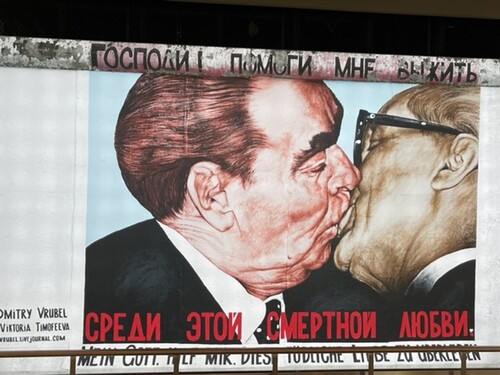

Most recently, we have seen makeshift pop-up street art depicting contemporary iconic political figures such as the embrace of former German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder and Vladimir Putin portraying their close personal and professional ties with regard to the Ukraine crisis and more specifically, Nord Stream, the Russian-controlled company in charge of building the first undersea gas pipeline directly connecting Germany and Russia (). This makeshift pop-up street art now hangs over the legendary “Bruderkuss” between Brezhnev and Honecker entitled “My God, Help Me to Survive This Deadly Love,” considered to be the most recognizable mural included in the East Side Gallery in Berlin ().

Figure 7. Makeshift pop-up street art at the East Side Gallery in Berlin depicting a Schröder/Putin embrace (Reuters).

Figure 8. The iconic “Bruderkuss” between Leonid Brezhnev, the former General Secretary of the Soviet Union in the 1979 and Erich Honecker, the former General Secretary of the Socialist Unity Party of the GDR. (Author’s picture).

Clearly, this is no longer about aesthetics, but about social, cultural, political, and thus ideological messages surrounding race and minoritized communities (with regards to Black Lives Matter) and about erasure, censorship and the future of art and culture under an oppressive political regime (within the Afghan context). And with the recent makeshift pop-up street art of the Schröder/Putin embrace, we are confronted with controversial and even “causal explanations” in a given crisis (Campos, Zaimakis, and Pavoni Citation2021) and time of war.

These examples indicate that street art has become a very prevalent, prominent and dare we say universal semiotic form of meaning-making in contexts of societal, political, and thus historical transformations and cultural production inextricably linked to issues of class, race, ethnicity, nationality, and gender. And different media play a key role in the production, circulation, and contestation of street art as a semiotic form and its valuation.

While there are many different approaches to the critical study of media representations, we believe that Agha’s understanding of mediatization is particularly relevant in comprehending the circulation of street art, and its political and economic dimensions. According to Agha,

To speak of mediatization is to speak of institutional practices that reflexively link processes of communication to processes of commoditization. Today, familiar institutions in any large-scale society (e.g. schooling, the law, electoral politics, the mass media) all presuppose a variety of mediatized practices as conditions on their possibility. In linking communication to commoditization, mediatized institutions link communicative roles to positions within a socioeconomic division of labor, thereby expanding the effective scale of production and dissemination of messages across a population, and thus the scale at which persons can orient to common presuppositions in acts of communication with each other. And since mediatization is a narrow special case of mediation, such links also expand the scale at which differentiated forms of uptake and response to common messages can occur, and thus, through the proliferation of uptake formulations, increase the felt complexity of so-called “complex society” for those who belong to it. (Agha Citation2011, 163)

Beyond the street – expanding surfaces and the exploration of materiality and function

While we have alluded to the different places, spaces, and surfaces where street art is found, we want to briefly discuss the relevance of street art’s expansion in terms of its emplacement with regard to materiality and function. From a historical perspective, and as Fernandez-Barkan (Citation2022) explores, graffiti and street art have made their way from signs of transgressive semiotics in unauthorized spaces like Russian trains to being archived and showcased in books, magazines, photographs and films highlighting how changing situated semiotic acts are performed sub-culturally yet influenced transnationally from the US to Russia and back again. According to Scollon and Scollon (Citation2003, 149) signs are considered transgressive to the viewer “if they appear in places not acceptable for the display of visual semiotic design.” These authors also indicate that at the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries within European and Western aesthetics of urban design, there was a stark preference for surfaces to be sign-less (without signs) indexing high degrees of elegance (Scollon and Scollon Citation2003, 149). For street artists, the city is a colossal canvas playground where blank or semi-blank surfaces are regarded as highly prized commodities for artists. “Clean” or even buffed space may be interpreted as an open invitation awaiting semiotic conquest whether it be sprayed, stenciled, or tagged and where the application and remix of materials, styles, imageries, and techniques are used drawing on a wide range of sources and different types of media. While the street may be considered to be the most egalitarian, democratic and thus inclusive space (Järlehed Citation2022; Jaworski and Gonçalves Citation2022), urban space is never neutral (Lefebrve Citation1991; Harvey Citation2006) and city walls are hardly public (Chang Citation2018). Yet, city walls are imbued with high regimes of public visibility and ensuing recognition. For Lamazares (Citation2014, 321), “recognition is both an internal code within the community of practice of street artists, and the larger social effect sought by the works as acts in public or publicly viewable space.” This recognition is often instantaneous via global circulation networked by advanced information and communication technology (Blommaert Citation2016; MacDowall and de Souza Citation2018) leading to the ways in which such artwork is recognized, mediatized, and valued. This process not only affects artists and their career trajectories (Weill Citation2022) but is indicative of how material surfaces and their symbolic and semiotic values and functions have shifted, resulting in a resignification of street art (Campos and Leal Citation2021; Gonçalves Citation2022). We see this happening in numerous places and spaces. Apart from being found in tattoo parlors, cafés (see ), galleries and museums – the latter of which is considered a place of “educative leisure” (Hanquinet and Savage Citation2012) – we now find the commissioning and perhaps even cooption of street art in Palestinian hotels for the sake of economic profit and global tourist appeal (Milani Citation2022), in private homes and gardens in Brazil (Gonçalves Citation2022) for reasons of aesthetics and claims to exclusivity.

Most recently, we have come across shower curtains, pillow cases (see ), sling chairs, socks, bar stools, stickers, yoga mats, bathmats, ipad and iphone holders as well as sunglasses sporting graffiti and street art, where artists create pieces which reflect their individual styles and for some artists, their designs are reminiscent of childhood memories. In these ways, graffiti and street art surpass the visual and move into more multisensorial, embodied and thus mobile spaces and places (Pennycook, Citation2022) where they can be touched, worn, carried, and sat on, among other things. Undeniably and perhaps also somewhat unsurprisingly, all of this street art paraphernalia is driven by contemporary capitalist market trends and neoliberal pursuits.

To sum up, this special issue of Social Semiotics centers on the dialectics of space and visuality by means of critically investigating street art (in its broadest form). This entails looking into different social semiotic processes of visuality from historical movements to contemporary arts-led revitalization movements (and beyond) that take place in urban centers as well as island territories in various parts of the world. The papers in this SI critically address and examine a range of diverse and complex processes, including the production of street art by artists themselves (Fernandez-Barkan; Snadjr and Trinch; Gonçalves), their public display, and the consumption, commission, and contestation of such work by different society members (Kramer, Järlehed). By so doing, the contributors of this special issue also illustrate the complex power relations surrounding street art, which involve a variety of social actors besides the artists themselves: entrepreneurs (Kramer Citation2022; Milani Citation2022), local policy makers (Järlehed), local residents (Gonçalves; Snajdr and Trinch), all of whom play significant roles within the socio-political regimes of visibility within urban transformation and regeneration processes in city spaces (Iveson Citation2010) as well as outside urban conglomerates (Gonçalves). Needless to say, an ambition to understand the semiotics, politics and economy of street art requires eclectic analytical and methodological apparatuses, ranging from ethnographic techniques to cultural studies analysis, from critical discourse analysis to art historical approaches. Such an interdisciplinary collection we believe provides readers with a comprehensive insight into the complex and changing nature of street art in order to account (and better understand) these social semiotic phenomena.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Rober Kaçi at Laif Photos and Reporting as well as both Lee Cibis and Sylvia Buchholtz at Reuters News Agency, for granting us permission to use several photos in this introduction. They would also like to thank Jennifer Biancaniello for allowing us to use pictures from the Washington D.C. area for this piece. They thank Ronald Kramer for his helpful feedback on an earlier draft of this introduction. And last but not least, the authors would like to thank all of the authors of this special issue for their insightful and thought-provoking contributions and the editors of Social Semiotics for believing in our ideas about the politics and economy of street art.

Dedication

To street artist Dmitri Vrubel.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Kellie Gonçalves

Kellie Gonçalves is a sociolinguist whose research interests are at the interdisciplinary interface between sociolinguistics, applied linguistics, human geography, mobility studies and social semiotics. Her recent publications include Labour Policies, Language Use and the ‘New’ Economy - The Case of Adventure Tourism. (Palgrave Macmillan 2020); Language, Global Mobilities, Blue-Collar Workers and Blue-collar Workplaces (with H. Kelly-Holmes. (Eds.) Routledge, 2021). Kellie is currently book review editor of the journal Linguistic Landscape.

Tommaso M. Milani

Tommaso M. Milani is a critical discourse analyst who is interested in the ways in which power imbalances are (re)produced and/or contested through semiotic means. His main research foci are: language ideologies, language policy and planning, linguistic landscape, as well as language, gender and sexuality. He has published extensively on these topics in international journals and edited volumes. Among his publications are the edited collection Language and Masculinities: Performances, Intersections and Dislocations (Routledge, 2016) and the special issue of the journal Linguistic Landscape on Gender, Sexuality and Linguistic Landscapes (2018). He is co-editor of the journal Language in Society.

References

- Agha, Asif. 2011. “Meet Mediatization.” Language & Communication 31: 163–170.

- Anderson, Ivar, Kristian Borg, and Sverker Ohlsson. 2007. Playground Sweden. Årsta: Dokument Förlag.

- Avramides, Konstantinos, and Myrto Tsilimpounidi. 2017. “Graffiti and Street Art: Reading, Writing and Representing the City.” In Graffiti and Street Art: Reading, Writing and Representing the City, edited by Konstantinos Avramides, and Myrto Tsilimpounidi, 1–24. New York: Routledge.

- Baird, J. A., and Claire Taylor. 2016. “Ancient Graffiti.” In The Routledge Handbook of Graffiti and Street Art, edited by Jeffrey I. Ross, 17–26. New York: Routledge.

- Banet-Weiser, Sarah. 2011. “Convergence on the Street: Rethinking the Authentic/Commercial Binary.” Cultural Studies 25 (4-5): 641–658.

- Baudrillard, Jean. 1981. For a Critique of the Political Economy of the Sign. London: Verso.

- Blanché, Ulrich. 2015. “Street Art and Related Terms: Discussion and Working Definitions.” Street Art and Urban Creativity Scientific Journal 1 (1): 32–39.

- Bloch, Stefano. 2016. “Challenging the Defense of Graffiti, in Defense of Graffiti.” In The Routledge Handbook of Graffiti and Street Art, edited by Jeffrey I. Ross, 440–451. New York: Routledge.

- Blommaert, Jan. 2016. “Meeting of Styles and the Online Infrastructures of Graffiti.” Applied Linguistics Review 7 (2): 99–115.

- Bofkin, Lee. 2014. Concrete Canvas. London: Cassell.

- Bonadio, Enrico. 2019. The Cambridge Handbook of Copyright in Street Art and Graffiti. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Borghini, Stefania, Luca Massimiliano Visconti, Laurel Anderson, and John F. Sherry Jr. 2010. “Symbiotic Postures of Commercial Advertising and Street Art.” Journal of Advertising 39 (3): 113–126.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1983. “The Field of Cultural Production, or: The Economic World Reversed.” Poetics 12: 311–356.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1984. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste. Translated by R. Nice. Cambridge: Polity.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1991. Language and Symbolic Power. Cambridge: Hard University Press.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1993. The Field of Cultural Production. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Campos, Ricardo. 2016. “From Marx to Merkel: Political Muralism and Street Art in Lisbon.” In The Routledge Handbook of Graffiti and Street Art, edited by Jeffrey I. Ross, 301–317. New York: Routledge.

- Campos, Ricardo, and Gabriela Leal. 2021. “An Emerging Art World: The De-Subculturalization and Artification Process of Graffiti and Pixação in São PAulo.” International Journal of Cultural Studies 24 (6): 974–992.

- Campos, Ricardo, Yiannis Zaimakis, and Andrea Pavoni, eds. 2021. Political Graffiti in Critical Times: The Aesthetics of Street Politics. New York: Berghahn.

- Chang, T. C. 2018. “Writing on the Wall: Street Art in Graffiti-Free Singapore.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 43 (6): 1046–1063.

- Coulmas, Florian. 2009. “Linguistic Landscaping and the Seed of the Public Sphere.” In Linguistic Landscape: Expanding the Scenery, edited by E. Shohamy, and D. Gorter, 13–24. New York: Routledge.

- Del Percio, Alfonso, Mi-Cha Flubacher, and Alexandre Duchêne. 2017. “Language and Political Economy.” In The Oxford Handbook of Language and Society, edited by Ofelia García, Nelson Flores, and Massimiliano Spotti, 55–75. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Dickens Luke, A. 2010. “Pictures On Walls? Producing, Pricing and Collecting the Street Art Screen Print”. Culture, Theory, Policy and Action 14 (1-2): 65-81.

- Eastmond, Anthony. 2015. Viewing Inscriptions in the Late Antique and Medieval World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Fernández-Barkan, Davida. 2022. Russian Train Graffiti: Is it Street Art? Social Semiotics.

- Ferrell, Jeff. 2016. “Foreword: Graffiti, Street Art, and the Politics of Complexity.” In The Routledge Handbook of Graffiti and Street Art, edited by Jeffrey I. Ross, xxx–xxxviii. New York: Routledge.

- Florida, Richard. 2002. The Rise of the Creative Class: And How It’s Transforming Work, Leisure, Community and Everyday Life. New York: Basic Books.

- Gal, Susan. 2016. “Language and Political Economy: An Afterword.” Journal of Ethnographic Theory 6 (3): 331–335.

- Goldman, Robert, and Stephen Papson. 2006. “Capital’s Brandscapes.” Journal of Consumer Culture 6: 327–353.

- Gonçalves, Kellie. 2018. “YO! Or OY? – Say What? Creative Place-Making Through a Metrolingual Artifact in Dumbo, Brooklyn.” International Journal of Multilingualism 16 (1): 42–58.

- Gonçalves, Kellie. 2019. “The Semiotic Paradox of Street Art: Gentrification and the Commodification of Bushwick, Brooklyn.” In Making Sense of People, Place and Linguistic Landscapes, edited by Amiena Peck, Quentin E. Williams, and Christopher Stroud, 141–160. London: Bloomsbury.

- Gonçalves, Kellie. 2022. “Street Art as ‘street fetish’ - A New Signifier of Social Class? The Case of Brazil’s ‘Beverley Hills’.” Social Semiotics.

- Graan, Andrew. 2016. “Introduction: Language and Political Economy Revisited.” Journal of Ethnographic Theory 6 (3): 139–149.

- Hanquinet, Laurie, and Mike Savage. 2012. “Educative Leisure and the Art Museum.” Museum & Society 10 (1): 42–59.

- Harvey, David. 2006. Spaces of Global Capitalism: Towards a Theory of Uneven Geographic Development. London: Verso.

- Hasley, Mark, and Alison Young. 2006. “‘Our Desires are Ungovernable’: Writing Graffiti in Urban Space.” Theoretical Criminology 10 (3): 165–186.

- Hasan Sharif. 2021. “Afghan Art Flourished for 20 Years. Can It Survive the New Taliban Regime?” The New York Times. Accessed May20, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/31/world/asia/afghanistan-taliban-artists.html?searchResultPosition=6

- Irvine Judith T. 1989. “When Talk Isn’t Cheap: Language and Political Economy.” American Ethnologist 16 (2): 248–267.

- Irvine, Martin. 2012. “The Work on the Street.” In The Handbook of Visual Culture, edited by Ian Heywood, and Barry Sandywell, 235–278. London: Berg.

- Iveson, Kurt. 2010. “Graffiti, Street Art and the City.” City 14 (1-2): 25–32.

- Jacobs, Julia. 2020. “The ‘Black Lives Matter’ Street Art That Contains Multitudes.” New York Times. Accessed May 12, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/16/arts/design/black-lives-matter-murals-new-york.html?searchResultPosition=7

- Janis, Sidney. 1983. Post-graffiti. Sidney Janis Gallery. New York.

- Jaworski, Adam, and Kellie Gonçalves. 2022. “Between Egalitarian and Elitist Stance in Oslo: SitatIBSEN as Banal Nationalism.” In Spaces of Multilingualism, edited by U. Røyneland, and R. Blackwood. New York: Routledge.

- Järlehed, Johan. 2017. ““B som i Bilbao och Ceñe som i A Coruña. Identitet, ideologi och indexikalitet i galiciska och baskiska stadslogotyper” [Identity, ideology and indexicality in Galician and Basque city logos].” In Språkens magi. Festskrift till Ingmar Söhrman, professor i romanska språk, edited by Andrea Castro, and Anton Granvik, 93–106. Göteborg: Göteborgs universitet.

- Järlehed, Johan. 2022. “The White Worker’s Hotdog and the not so White Worker’s Falafel: Food-Based Public Art and Urban Redevelopment in a Changing Society.” Social Semiotics.

- Karlander, David. 2019. “A Semiotics of Non-Existence? Erasure and Erased Writing Under Anti-Graffiti Regimes.” Linguistic Landscape 5 (2): 199–216.

- Kim, Youmi, and Mike Ives. 2021. “Couple Who Defaced $400,000 Painting Thought It Was a Public Art Project”. Accessed 15 May 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/07/world/asia/jonone-vandalism-south-korea-art.html?searchResultPosition=1.

- Korea JoongAng Daily. Accessed 7 May 2022. https://koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/2021/03/30/imageNews/photos/jonone-graffiti-mural/20210330172500515.html.

- Kramer, Ronald. 2010. “Painting with Permission: Legal Graffiti in New York City.” Ethnography 11 (2): 235–253.

- Kramer, Ronald. 2022. “The battle for 5Pointz and signifying regimes: Desirable subjects, hierarchies of value, and legitimizing state power.” Social Semiotics.

- Lachmann, Richard. 1988. “Graffiti as Career and Ideology.” American Journal of Sociology 94 (2): 229–250.

- Lamazares, Alexander. 2014. “Exploring São PAulo's Visual Culture: Encounters with Art and Street Culture Along Augusta Street.” Visual Resources 30 (4): 319–335.

- Lees, Loretta. 2003. “Super-Gentrification: The Case of Brooklyn Heights, New York City.” Urban Studies 40 (12): 2487-2509.

- Lefebrve, Henri. 1991. The Production of Space. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

- Ley, David. 2003. “Artists, Aestheticisation and the Field of Gentrification.” Urban Studies 40 (12): 2527–2544.

- Logan, John R., and Harvey Molotch. 1987. Urban Frontiers. Berkeley, CA: California University Press.

- MacDowall, Lachlan and Poppy de Souza. 2018. “‘I’d Double Tap That!!’: Street Art, Graffiti, and Instagram Research.” Media, Culture & Society 40 (1): 3-22.

- Markusen, Ann, and Greg Schrock. 2006. “The Distinctive City: Divergent Patterns in Growth, Hierarchy and Specialization.” Urban Studies 43 (8): 1301–1323.

- McAuliffe, Cameron. 2012. “Graffiti or Street Art? Negotiating the Moral Geographies of the Creative City”. Journal of Urban Affairs 34(2): 189–206.

- McRobbie, Angela. 2004. “‘Everyone is Creative’: Artists as Pioneers of the New Economy?” In Contemporary Culture and Everyday Life, edited by Elizabeth Silva, and Tony Bennett. London: Routledge.

- Milani Tommaso M. 2022. “Banksy’s Walled Off Hotel and the Mediatization of Street-Art.” Social Semiotics.

- Molotch, Harvey. 1976. “The City as Growth Machine: Toward a Political Economy of Place.” American Journal of Sociology 82 (2): 309–332.

- Muth, Sebastian. 2016. “Street Art as Commercial Discourse: Commercialisation and a New Typology of Signs in the Cityscapes of Chisinau and Minsk.” In Negotiating and Contesting Identities in Linguistic Landscapes, edited by Robert Blackwood, and Elizabeth Lanza, 19–36. London: Bloomsbury.

- Pennycook, Alastair. 2007. “Linguistic Landscapes and the Transgressive Semiotics of Graffiti.” In Linguistic Landscape: Expanding the Scenery, edited by Elana Shohamy, and Durk Gorter, 302–312. London: Routledge.

- Pennycook, Alastair. 2010. “Spatial Narrations: Graffscapes and City Souls.” In Semiotic Landscapes Language, Image, Space, edited by Adam Jaworski, and Crispin Thurlow, 137–150. London: Continuum.

- Pennycook, Alastair. 2022. “Street Art Assemblages.” Social Semiotics.

- Petrucci, Armando. 1980 (1993). Public Lettering. Translated by L. Lappin. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Reyburn, Scott. 2021. Banksy’s Shredding Artwork Is Auctioned for $25.4 Million at Sotheby’s. Accessed 15 May 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/14/arts/design/banksy-art-sothebys-auction.html?searchResultPosition=1.

- Romero, Rachel. 2018. “Bittersweet Ambivalence: Austin’s Street Artists Speak of Gentrification.” Journal of Cultural Geography 35 (1): 1–22.

- Ross, Jeffrey I. 2016. “Introduction: Sorting it all out.” In The Routledge Handbook of Graffiti and Street Art, edited by Jeffrey I. Ross, 1–10. New York: Routledge.

- Schachter, Rafael. 2014. “The Ugly Truth: Street Art Graffiti and the Creative City.” Art & the Public Sphere 3 (2): 161–176.

- Scollon, Ron, and Suzie Wong Scollon. 2003. Discourses in Place: Language in the Material World. London: Routledge.

- Shapiro, Roberta, and Natalie Heinich. 2012. “When is Artification?” Contemporary Aesthetics (4). https://digitalcommons.risd.edu/liberalarts_contempaesthetics/vol0/iss4/9/

- Snajdr, Edward and Shonna Trinch. 2022. “To Preserve and to Protect Vanishing Signs: Activism through Art, Ethnography and Linguistics in a Gentrifying City.” Social Semiotics.

- Snyder, Gregory. 2016. “Graffiti and the Subculture Career.” In The Routledge Handbook of Graffiti and Street Art, edited by Jeffrey I. Ross, 204–214. New York: Routledge.

- Small, Zachary. 2021. “The ‘Fearless Girl’ Statue Is in Limbo.” Accessed 10 May 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/11/16/arts/design/fearless-girl-fate-uncertain.html?searchResultPosition=2.

- Taylor, Myra F., Julie Anne Pooley, and Georgia Carragher. 2016. “The Psychology Behind Graffiti Involvement.” In The Routledge Handbook of Graffiti and Street Art, edited by Jeffrey I. Ross, 194–203. New York: Routledge.

- Thurlow, Crispin, and Adam Jaworski. 2012. “Elite Mobilities: The Semiotic Landscapes of Luxury and Privilege.” Social Semiotics 22 (5): 487–516.

- Thurlow, Crispin, and Adam Jaworski. 2017. “Introducing Elite Discourse: The Rhetorics of Status, Privilege, and Power.” Social Semiotics 27 (3): 243–254.

- Trinch, Shonna, and Edward Snadjr. 2020. What the Signs Say: Language, Gentrification, and Place-Making in Brooklyn. Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Press.

- Wells, Maia M. 2016. “Graffiti, Street Art, and the Evolution of the Art Market.” In The Routledge Handbook of Graffiti and Street Art, edited by Jeffrey I. Ross, 464–474. New York: Routledge.

- Weill, Pierre-Edouard. 2022. “From the Train Yard to the Auction House: Connecting the Graffiti Subculture to the Art Market.” Cultural Sociology 16 (1): 45–67.

- Young, Alison. 2014. Street Art, Public City: Law, Crime and the Urban Imagination. London: Routledge.

- Zukin, Sharon. 1982. Loft Living: Culture and Capital in Urban Change. Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University Press.

- Zukin, Sharon. 1995. The Cultures of Cities. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.

- Zukin, Sharon. 2011. “Reconstructing the Authenticity of Place.” Theory and Society 40 (2): 161–164.