ABSTRACT

This article offers a critical semiotic analysis of the media discourses about Banksy’s Walled Off Hotel in Bethlehem. Unlike the existing burgeoning scholarship on this tourist initiative, the article focuses less on the space of the hotel itself and the street art therein than on their mediatization. With the help of the notion of mediatization, the article offers a granular account of the discursive circulation of Banksy’s street art assemblage, with the concomitant processes of social value formation as well as the ambivalent array of moral and affective components involved in such valorization. The mediatization of Banksy’s street art in Palestine interpellates visitors by affectively and morally enticing them to have a first-hand experience of the Israeli/Palestinian conflict, namely consuming its mediatized object par excellence, the graffitied wall and/or its reproduction. Less enthusiastic uptakes instead take issue with the affective logic upon which such mediatization seems to be built.

Introduction

In March 2017 street artist par excellence, Banksy, started a new commercial venture, The Walled Off Hotel in Bethlehem (the entrance to the hotel can be seen in ). Unlike its near-homophone Waldorf in New York and elsewhere in the world, the Bethlehem accommodation touts “the worst view in the world” (The Guardian 3 March Citation2017), directly overlooking the separation wall that divides Israel from the West Bank; it also boasts a large selection of street art and other creations, which make the hotel a semiotic and material assemblage (see also Sharma Citation2021 and Pennycook this issue). The Walled Off Hotel is not Banksy’s first engagement with Palestine. Since his initial visit in 2005, he created several iconic images on the separation wall, which in his words “essentially turns Palestine into the world’s largest open prison” (The Guardian 5 August Citation2005). The timing of the new initiative was not accidental. As Banksy clarified in an interview, year 2017 marked “exactly 100 years since Britain took control of Palestine and started rearranging the furniture – with chaotic results.” He went on to say: “I don’t know why, but it felt like a good time to reflect on what happens when the United Kingdom makes a huge political decision without fully comprehending the consequences” (The Guardian 3 March Citation2017). In the same interview, Banksy also explained that such a commercial venture has a quasi-medicinal aim, “being a three-storey cure for fanaticism” (The Guardian 3 March Citation2017), but obviously only available for those who can afford this type of therapy. For the cost of the rooms decorated with artwork by Banksy, the Palestinian artist Sami Musa and the Montreal-based Dominique Petrin ranges from 200 to 900 USD per night. There is also a 60 USD option, which, according to the hotel website, is “outfitted with surplus items from an Israeli military barracks, and offers no frills, includes locker, personal safe, shared bathroom, as well as complimentary earplugs.”

The opening of the hotel received mixed reactions: it was criticized by some as trivializing the conflict; it was welcomed by others who saw the potential of attracting travellers and economic capital to Bethlehem and the West Bank. Moreover, the hotel has become the object of sustained academic inquiry. For example, the Palestinian scholar Jamil Khader draws upon Foucault’s notion of heterotopia to capture the irreconcilable ambivalences of the space of the hotel conveying “the dystopian realities in Palestine” at the same time as it “inscribes a utopian dimension that universalizes the Palestinian struggle for freedom by linking it to the struggles of other disposable communities around the world” (Khader Citation2018, 138). Also focusing on ambiguities but in relation to movement more specifically, in another article Khader (Citation2020) employs the metaphor of architectural parallax, that is, the difference in the direction of an object depending on the observer’s viewpoint, in order to illustrate the contradictions between “on the one hand, the free mobility of ideas and capital which made such an installation-hotel possible in the first place, and on the other, the restrictions on the mobility of Palestinians under Israeli military occupation and Zionist settler-colonial regime” (Citation2020, 474).

Unlike this important burgeoning scholarship, the present article focuses less on the space of the hotel itself with the street art therein than on their mediatization (Agha Citation2011). I believe that mediatization is a particularly useful concept through which to address the topic of this special issue, namely the interconnectedness of the semiotic, political, and economic aspects of street art. As it will become clearer in the next section, mediatization allows us to give a granular account of the discursive circulation of street art, with the concomitant processes of social value formation as well as the complex array of moral and affective components involved in such valorization.

Mediatization, morality and affect

Over the last few years, mediatization has gained considerable momentum in different strands of research interested in understanding the role played by different media as “centering institutions” (Silverstein Citation1998), in “social envisioning” (Peters Citation1997) and in making “society imaginable to itself” (Mazzarella Citation2004, 357). At the risk of oversimplification, mediatization can be understood in two different but interrelated ways. Firstly, from a media studies perspective, it indicates “a historical, ongoing, long-term process in which more and more media emerge and are institutionalized” in such a way that “in the long run [they] increasingly become relevant for the social construction of everyday life, society, and culture as a whole” (Krotz Citation2009, 24). According to this view, mediatization has become an intrinsic modality of late modern conditions permeating everyday life in large parts of the world. What mediatization entails and how it affects people’s behaviour is pithily captured by Lundby (Citation2009), who rhetorically asks: “Who could manage without a cell phone, e-mail, favourite social networking site, or whatever means of communication one chooses to stay connected?” (Citation2009, 1).

Secondly, without downplaying the structural role played by mediating technologies in late modern societies but with an interest in tracing more precisely their discursive manifestations, some linguistic anthropologists have argued that mediatization “includes all the representational choices involved in the production and editing of text, image, and talk in the creation of media products” (Jaffe Citation2009, 572). Such a definition echoes a well-established critical discourse analytical approach according to which media practitioners (editors, sub-editors, filmmakers, journalists, photographers, etc.) always need to make choices when visually representing or writing about a phenomenon “out there” – be it crime, fashion, political developments, or resistance movements. Whether intentional or not, such choices are inherently ideological because they entail the exclusion of possible alternatives.

Bridging a media studies perspective on the institutionalization of mediated practices in everyday life with a linguistic anthropological attention to the nitty-gritty of discursive exchanges, Agha has suggested that:

To speak of mediatization is to speak of institutional practices that reflexively link processes of communication to processes of commoditization. Today, familiar institutions in any large-scale society (e.g. schooling, the law, electoral politics, the mass media) all presuppose a variety of mediatized practices as conditions on their possibility. In linking communication to commoditization, mediatized institutions link communicative roles to positions within a socioeconomic division of labor, thereby expanding the effective scale of production and dissemination of messages across a population, and thus the scale at which persons can orient to common presuppositions in acts of communication with each other. And since mediatization is a narrow special case of mediation, such links also expand the scale at which differentiated forms of uptake and response to common messages can occur, and thus, through the proliferation of uptake formulations, increase the felt complexity of so-called “complex society” for those who belong to it. (Agha Citation2011, 163)

Granted, commodity and commodification seem to have become problematic buzzwords in much sociolinguistically inflected scholarship and should be treated with caution (see McGill Citation2013; Lou Citation2021 for a critique). A cautionary note is also raised by Agha who reminds us that “nothing is always or only a commodity” (Agha Citation2011, 164) but depends on the context. Sacred texts are illuminating examples, being “treated as retail commodities in one participation framework (acts of purchase), but not in another (prayer)” (Agha Citation2011, 164). By the same token, street art, murals and graffiti can be forms of politically charged semiosis in one participation framework (see e.g. Pennycook Citation2007; Haupt et al. Citation2019), but they can be turned into commodities when they are extracted, removed, and then put on sale, or, in a less heavy-lifting manner, when they are re-semiotized (Iedema Citation2003) into products of mass consumption such as T-shirts, mugs, fridge magnets and marketed on, say, a website. Whether the transgressive aspect of street art gets transferred or is tamed and made “respectable” in such resemiotizations should not be assumed but investigated empirically (see Ross, Lennon, and Kramer Citation2020 for an insightful analysis of the commodification and co-optation of graffiti and street art).

Such a perspective on mediatization, then, does not seek to establish a priori whether a mediatized object is a commodity. Rather, it forces us to trace more precisely the “inter-linkages among semiotic encounters of diverse kinds, some of which may involve mediatized objects, others may recycle mediatized images in other activities, others do neither, and others, which, while they do neither, may later be recycled in mediatized depictions” (Agha Citation2011, 165). Moreover, it illustrates how such discursive connections are bound up with value production. Crucially, a great deal of subject formation is also involved in mediatized encounters thanks to participatory frameworks involving communicative acts of interpellation (Althusser Citation1971): (1) audiences are first “hailed” as specific types of consumers imbued with a plethora of qualities – this is the moment of subject formation; (2) they then may or may not “turn around” responding to the interpellation – the uptake, and (3) subsequently, a variety of other social actors may reproduce and/or contest these subject positions – what one might wish to call the scaling of uptake.

I argue in this article that morality and affect play key roles in such ideological processes of subject formation and object evaluation (see also Thurlow Citation2016; Borba Citation2021). Here affect is conceptualized not so much as a psychological state but as a socio-cultural set of practices through which emotions are brought into being semiotically in interaction, and orient subjects towards other subjects or objects “with degrees of proximity and urgency, sympathy and concern, aversion or hostility” (Martin Citation2014, 120). And, as Martin goes on to explain, “these orientations are never fixed or complete but are open to contestation and negotiation, mediated often (though not exclusively) by rhetorical argument” (Martin Citation2014, 120). By morality I mean discursive acts in which speakers/writers express their views about what counts as good or bad conduct as in the case of buying (or not) a souvenir produced in a context of conflict and suffering. Whether, and if so how, moral judgments are imbued with affective layers has been the topic of a long-standing debate in philosophy (see Spencer-Bennet Citation2018 for a discussion) and is ultimately an empirical question.

Analytically, the moral and affective loadings of mediatization can be captured through the notion of stance. While it lies beyond the scope of this article to offer an overview of the sociolinguistic and discourse analytical literature on the concept (see Jaworski Citation2007), suffice it to say that stance has been famously defined by Du Bois as

a public act by a social actor, achieved dialogically through overt communicative means […] through which social actors simultaneously evaluate objects, positions subjects (themselves and others), and align with other subjects, with respect to any salient dimension of the sociocultural field. (Citation2007, 163; emphasis added)

The researcher’s positionality vis-à-vis the complexity of Israel/Palestine

The examples under investigation in this article are part of a larger ethnographic project which started soon after the opening of the Walled Off Hotel in Bethlehem in 2017. I stayed at the hotel several times and took part in guided tours of the graffiti on the separation wall and adjacent Aida refugee camp. I interviewed local artists, visitors, shop owners and other stakeholders directly involved (or not) in the tourism business in Bethlehem. I also sought to collect any mention of the Walled Off Hotel in mainstream media, airline magazines, TripAdvisor comments and cookbooks. In no way do I wish to suggest that the analysis in this article is representative of all the different media discourses about the hotel. Rather, in what follows, I offer a glimpse into the texture of the mediatization of street art that can be viewed and bought at The Walled Off Hotel.

Such an interest in the semiotic activities in and about the hotel has been spurred by my critical discourse analytical commitment to tracing and understanding how social inequalities are produced and contested. I am a wandering academic carrying a complex history of migration. While I experienced the Israeli system of checkpoints during fieldwork, I have also been extremely privileged to be able to move in and out of the West Bank pretty seamlessly. I cannot emphasize enough the privilege embodied in such freedom of movement, which is in stark contrast with the feeling of confinement, lived experiences of surveillance, and endless movement control directly felt by Palestinians in the West Bank.

When I discussed an earlier version of this paper with an audience in Israel, I was met with suspicion, confrontation, and selective misunderstanding (see Milani Citation2020). Therefore, I want to state upfront that I never aimed at writing a “balanced” article in which Banksy’s work would be compared with, say, the paintings by Israeli children living on the Gazan border. I certainly do not wish to downplay the distress and bereavement experienced by many Israelis because of the armed conflict. I recognize the right of the state of Israel to exist and I also firmly believe that Israelis and Palestinians share the responsibility for past and current hostilities. Yet I am also wary of the pitfalls of the illusion of symmetry, that is, the conviction that both sides of the conflict carry equal weight. Ultimately, the Israeli/Palestinian conflict is asymmetrical and in line with radical left activists in Israel and elsewhere I “underscore Israel’s dominant position as a powerful occupying force” (Katriel Citation2020, 11) in the West Bank.

Finally, it is not the aim of this article to either praise or issue a quick verdict of guilt against Banksy’s street art in Palestine or elsewhere. Whether such artwork is considered ontologically “good,” “bad” or a bit of both is beside the point. Rather, the goal is to understand what the mediatization of Banksy’s street art does, ensnaring viewers/readers into an intricate patchwork of moral and affective stances bound up with capitalist consumption. It is to such complex identity work to which I now turn.

Street art and the quandaries of a morally good consumer

The Walled Off Hotel gift shop can be a relevant starting point for tracing the mediatization of Banksy’s street art and its political valence. As we are told on the hotel website,

Extract 1

The gift shop is situated towards the back of the hotel and sells items created exclusively for the Walled Off by Banksy. It should not be confused with the “Banksy Shop” next door – which has nothing to do with Banksy at all. All profits from sales go towards sustaining the hotel and social projects. Select items are available worldwide on mail order.

Secondly, there is also the discursive enactment of a definite moral stance. The website indicates that all profits go to sustaining the hotel and to an unspecified set of social projects. In such a way, readers/viewers are reassured of the good nature of the consumerist enterprise of selling products connected to Palestinian grim conditions in the West Bank. Taken together, the description of the gift shop and the picture of Banksy’s collectables sold on the hotel website are textbook examples of mediatization understood as “institutional practices that reflexively link processes of communication to processes of commoditization,” and, in doing so, laminate this linkage with a moral patina. Here graffiti on the Separation Wall as a form of political communication (see Hanauer Citation2011) has been resemiotized as an object of consumption that should be invested in for a good cause.

Cognizant that not everyone would agree on such a confident moral stance, resistant readers/viewers who find the sale of political semiosis debateable are directly addressed on the hotel website:

Extract 2

Just in case you weren’t sure what Banksy thinks about the wall (not a fan) his latest range of ‘souvenir collectables’ anticipate the day the concrete menace has been defeated and feral youth scribble on its skeletal remains. For those of you concerned that making glorified tourist tat from military oppression is ethically dubious – there is at least the solace that each wall is lovingly hand painted by craftspeople in the local area.

In brief, hidden polemic is employed to simultaneously anticipate and incorporate a moral critique of the souvenir sale, and thereby take distance from such criticism and justify the sales. What is particularly interesting is the tone of this excerpt. While “feral youth” linguistically evokes a kind of punk aesthetics that matches Banksy’s overall visual style, the “lovingly hand-painted” wall is stridently at odds with the affective loading of graffiti as materializations of anger and suffering. Here the authorial voice’s evaluation and justification of a “glorified tourist tat” is irreverent (see in particular Weeks (Citation2012) for a discussion about the negative connotations of the word “tourist” as opposed to “traveller”). One cannot but wonder whether the word “solace” in this context encodes the authorial voice’s sarcastic wink dismissing a far too anxious ethical consumer, or conversely if it indicates tongue-in-cheek critical distance on the part of the authorial voice from their own otherwise positive evaluation of the sale of Banksy’s street art.

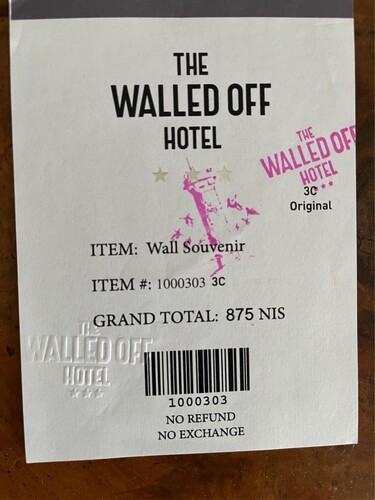

Overall, this extract offers a window into the complex ambivalences of the moral and affective stances instantiated by the mediatization of the Walled Off Hotel Street art. On the one hand, the sale of re-semiotized versions of the separation wall is overlayed with a veneer of goodness at the same time as viewers are reassured of the ethical nature of this commercial activity. The morality of this enterprise, however, is not completely crystal clear but is tainted by the qualms of presumed resistant readers and the ambiguousness encoded in the authorial voice’s flippant tone. It is such moral ambiguity that I also experienced when interpellated by a hotel employee into the purchase of a Banksy’s souvenir (see and ).

Just before checking out from the Walled Off Hotel, I decided to browse the books and other items in the hotel’s gift shop. No sooner did I cast my gaze on the small reproductions of the wall (see above) than the shop assistant said something along these lines: “Since you stayed at the hotel, you can buy one of these.” These words not only reminded me of what I had read on the hotel’s website (see Extract 1) but were a mundane linguistic instantiation of elite production through which “wider groups of people [are] being persuaded to think of themselves as privileged (rather than entitled) and feeling good about it because it is something they have worked for, something they have earned” (Thurlow Citation2016, 510). I was being interpellated into a subject position of social distinction not too dissimilar to the elite status in tourism discourse analyzed by Jaworski and Thurlow (Citation2009, Citation2017): I was now in the position of being able to buy the object, a situation that was exclusive to that specific moment and could only be repeated if I had stayed at the hotel again.

Undecided about what to do, I started to ask a barrage of questions about who had made the artwork and who would benefit from the purchase. The shop assistant replied giving somewhat vague answers in line with what can also be found on the hotel website: the reproductions are made by local artists, but Banksy vets them and signs them off. I found myself in a quandary – to buy or not to buy? – Buying would entail taking a morally ambiguous stance: one of social distinction and complicity in a voyeuristic gaze on the conflict, though with some reassurance of contributing to a good cause. Not buying would mean opting out completely, not without a sense of guilt, though, of having missed an opportunity to support a worthy initiative (see also Larkin Citation2014 for an analysis of the complexity of entrepreneurial initiatives around the wall). Possibly sensing this moral dilemma, the shop assistant began to praise the beauty of one of the items (see ), highlighting the dream of a future in which the wall will have been torn to pieces. It is at this juncture that I could not resist the tentation of what Thurlow calls “the sensuous, euphoric play of stuff – the little things themselves” (Thurlow Citation2016, 510). Granted, Thurlow is interested in understanding a different set of affective and moral dilemmas, those experienced by air travellers upgrading themselves to premium economy. Such quandaries emerge because

inequality is just too attractive. Especially, when we are everywhere and constantly being taught to elevate ourselves, to desire a better-than-all-the-rest status. And that its attainment all just so easy. It is really just a matter of a slipping out of those pale-blue seats and into those ever so slightly dark-blue seats. Just beyond that harmless swatch of curtain. And, frankly, because I'm worth it. (Thurlow Citation2016, 511)

Aestheticizing politics or politicizing art?

Of course, Banksy’s street art as a mediatized object does not necessarily generate the kind of morally ambivalent uptake experienced by me. Among the people I interviewed and those who gave public statements on the Walled Off Hotel, it was not uncommon to take far more definite moral and affective stances in the evaluation of the hotel. For example, Bethlehem’s mayor Anton Salman categorically stated in an interview reported in The Jerusalem Post: “The Banksy Hotel is a new experience for tourists in Bethlehem … It helps show the conflict our people are facing.” By the same token, a hotel manager and a restaurant owner who spoke with me emphasized how the opening of the hotel contributed to bringing in a new category of visitors – politically sensitive and willing to stay the night in Bethlehem – which is differentiated from the traditional visitor – the pilgrim who typically stays overnight in Israel and gets bussed in and out of Bethlehem over the day mainly to worship the birthplace of Jesus in the Nativity Church.

Others were less complimentary such as the Palestinian artist Ayed Arafah, who stated directly after the hotel’s inauguration:

Extract 3

I see how [Banksy’s] work brings a lot of people to Bethlehem to see the wall and the city. But now all the people who come to take photos of the paintings and graffiti … it’s become like Disneyland. Like you are living in a zoo. (Ayed Arafah, https://hexagongallery.com/news/walled-off-hotel-not-all-palestinians-are-happy-with-banksys-bethlehem-hotel/)

Extract 4

The fact that the wall has become a commodity to be sold and traded and mass produced that by itself a big shame and unacceptable while the real apartheid wall is still standing and besieging all the West Bank and Gaza. By all means, that wall is an ugly grey monster that is blocking us from the nice views of our hijacked olive groves and land; the wall has blocked us from our historic Palestine and our capital Jerusalem and our water resources and made us into slaves in our land. (Rana Bishara, personal communication)

The materiality of the wall was also brought up by the car mechanic who works just around the corner from the Walled Off Hotel. Sitting in the claustrophobic shade of his workshop on a hot summer day with no view other than the 10-meter-high separation wall (see below), he reminisced of times long gone when people came from Jerusalem to have their car repaired by him. Such a narrative is in stark contrast to the dire reality of the present with little work and the never-ending Israeli military surveillance in the nearby turret.

Extract 4

Come, I want to show you the facts of this place … Contrary to the air-conditioned hotel where tourists sit to enjoy the view of the wall from the lobby … this is the reality that we live … while constructing the wall … the soldiers used the next-door building for surveillance and they used to go up from one side of the building … Then the army tried to destroy the garage … and I stood with my friends and relatives and formed a human shield and we prevented the army from destroying the place.

The juxtaposition of the diametrically different lived experiences of the tourist and the mechanic in relation to the wall, the hotel and Banksy’s street art resonate well with Walter Benjamin’s famous opposition between the “aestheticization of politics” and “politicization of art.”

“Fiat ars – pereat mundus”, says Fascism, and, as Marinetti admits, expects war to supply the artistic gratification of a sense perception that has been changed by technology. This is evidently the consummation of “l’art pour l’art.” Mankind, which in Homer’s time was an object of contemplation for the Olympian gods, now is one for itself. Its self-alienation has reached such a degree that it can experience its own destruction as an aesthetic pleasure of the first order. This is the situation of politics which Fascism is rendering aesthetic. Communism responds by politicizing art. (Benjamin Citation1969, 20)

Extract 5

Si gode di un’altra vista al Walled Off Hotel nei territori occupati. La sua inaugurazione l’anno scorso ha suscitato clamore perché dietro ć’è lo zampino del celebre e controverso graffitista Banksy … Ogni stanza ha un intervento di Banksy, come l’immagine giocosa di una lotta coi cuscini tra un soldato israeliano e un manifestante palestinese.

One can enjoy a different view at the Walled Off Hotel in the occupied territories. Its inauguration last year caused a stir because behind it is the hand of the famous and controversial graffiti artist Banksy … Each room has a Banksy intervention, like the playful image of a pillow fight between an Israeli soldier and a Palestinian protester. (Ulisse, June Citation2018)

An equally ambivalent stance is also taken by the famous Palestinian master chef Sami Tamimi and British writer Tara Wigley in yet another discursive moment of the mediatization of the Walled Off Hotel in the cookbook Falastin (Tamimi and Wigley Citation2020). Directly after a tantalizing recipe of a sugary muhallabieh (the Palestinian version of panna cotta), with cherries and hibiscus syrup, the cookbook comes to a closure with a more bittersweet ending dedicated to The Walled Off Hotel, the separation wall, and the Balfour botch.

Extract 6

The “making of art of the occupation” question is complex but our take is that: … If art helps get people to look at (and therefore think about, talk about, and tell people about) the separation wall, for example is this really such a bad thing? … Tara bought three T-shirts for her kids to wear back home in London … Does this make Tara an “occupation tourist”, making light of what she has seen by a “been there, done that, got the T-shirt” attitude? … On the one hand, these souvenirs are all too easy, too neat: the fridge magnet, the tote bag. But the questions and chats really do follow … Getting people talking, getting kids asking questions; it’s a really important part of the process of making change happen.

Extract 7

Boire un verre face au mur!

La terrasse du Walled Off donne directement sur le mur. On y ressent donc précisément le ressenti des palestiniens enfermés dans leurs territoires. Et l'on ne peut qu'admirer leur manière artistique de se rebeller. Tout en sirotant un excellent mocktail ou une bière locale Sheperd. La visite du musée a l'intérieur est un must, comme celle de la gallérie de peintures, sans un décor Bansky grandiose! Bref, un endroit insolite où l'on arrive à se trouver bien!

Have a drink facing the wall!

The terrace of the Walled Off is directly on the wall. It is precisely the feeling of Palestinians locked in their territories. And we can only admire their artistic way of rebelling. While sipping an excellent mocktail or a local Sheperd beer.

The visit to the museum inside is a must, like that to the gallery of paintings, without a grandiose Banksy decor! In short, an unusual place where it’s possible to feel well!

Concluding remarks

With its trophies of surveillance systems juxtaposed to more rudimental slingshots above a porcelain plate of a young Princess Diana, it is evident that a certain degree of irony is employed by the Walled Off Hotel as a semiotic and material assemblage which represents the Israeli/Palestinian conflict and its colonial roots for prospective visitors. With the help of street art in the hotel and “authentic” miniature reproductions of the wall sold therein, the Walled Off Hotel cleverly twists and turns the neoliberal imperative to invest, this time for a “good cause,” that is, Palestinian resistance against Israeli occupation. With political economic savviness, the mediatization of the Walled Off Hotel and street art connected to it relies on turning Israeli apparatuses of security into artistic objects of spectacle, with a view to targeting a specific segment of the tourist population, those who are relatively well-off, politically aware, and even those who might be sceptical of the whole hotel enterprise, in order to bring valuable economic resources into the hotel and the city of Bethlehem. All this with a little bit of tongue-in-cheek distance. The logic goes as follows: Dear visitor, whether distraught by Palestinian resistance and suffering, drawing pleasure from watching it, or a bit of both, come and give us your money, while we wink at you and, a little bit, at ourselves too. More specifically, the mediatization of Banksy’s street art in Palestine interpellates visitors by affectively and morally enticing them to have a first-hand experience of the Israeli/Palestinian conflict, namely consuming its mediatized object par excellence, the graffitied wall and/or its reproduction. Other scholars have argued that the “Wall in Palestine is a thing – an object – which outside its particular context and placement, means nothing. It is mortar and concrete and wire, constructed to a specific width and height and length” (Mielke Citation2017, 13). Quite the opposite, I would argue. Through mediatization, the Wall means a lot to different people outside its placement and immediate surroundings. Moreover, such meanings are imbued with complex affective and moral loadings, as manifested in the stances of various social actors in several discursive sites. Less enthusiastic uptakes take issue with the “logic of affect” (Isin Citation2004) upon which such mediatization seems to be built. For these voices, the activation of the spectacle of pain and resistance together with a certain degree of pleasure and (self)-indulgence while reassuring consumers that they are doing something virtuous might be walking an ethically dodgy line that engenders moral dilemmas. In contrast, the positive stances in the uptakes evaluate the Walled Off Hotel as a street art assemblage (Pennycook, this issue) that might indeed serve an important educational and political function in that it makes Israeli occupation and Palestinian resistance to it visible for a variety of relatively wealthy audiences. Analogous to the platform at Ground Zero in New York City, the Walled Off Hotel might “function not as a means to an end, but as a memorial in itself – one that both commemorates and inspires a more politicized form of tourism” (Lisle Citation2004, 19). And the street art sold therein, though part and parcel of capitalist consumption, might work as a memento reminding viewers of current socio-political inequities and stimulating political engagement.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Dr Muzna Awayed-Bishara for our long-standing conversation about Israel/Palestine and for helping me to collect the interview data and translating it from Arabic to English. I would also like to thank Roey Gafter, Marie Maegaard, Roberta Piazza, Sarah Schulman and the audiences at the conferences Sociolinguistics Symposium 22 in Auckland and Mediatizing Resistance in Rio de Janeiro for their insightful comments on previous versions of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Tommaso M. Milani

Tommaso M. Milani is a critical discourse analyst who is interested in the ways in which power imbalances are (re)produced and/or contested through semiotic means. His main research foci are: language ideologies, language policy and planning, linguistic landscape, as well as language, gender and sexuality. He has published extensively on these topics in international journals and edited volumes. Among his publications are the edited collection Language and Masculinities: Performances, Intersections and Dislocations (Routledge, 2016) and the special issue of the journal Linguistic Landscape on Gender, Sexuality and Linguistic Landscapes (2018). He is co-editor of the journal Language in Society.

References

- Agha, Asif. 2011. “Meet Mediatization.” Language & Communication 31: 163–170.

- Althusser, Louis. 1971. Lenin and Philosophy and Other Essays. New York: Monthly Review Press.

- Benjamin, Walter. 1969. “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” In Illuminations, edited by Hannah Arendt, 1–26. New York: Schocken Books.

- Borba, Rodrigo. 2021. “Disgusting Politics: Circuits of Affects and the Making of Bolsonaro.” Social Semiotics 31 (5): 677–694.

- Bucholtz, Mary. 2003. “Sociolinguistic Nostalgia and the Authentication of Identity.” Journal of Sociolinguistics 7 (3): 398–416.

- Buck-Morss, Susan. 1992. “Aesthetics and Anaesthetics: Walter Benjamin's Artwork Essay Reconsidered.” October 62: 3–41.

- Chouliaraki, Lilie. 2008. The Spectatorship of Suffering. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Du Bois, John W. 2007. “The Stance Triangle.” In Stancetaking in Discourse: Subjectivity, Evaluation, Interaction, edited by Robert Englebretson, 139–182. Benjamins: Amsterdam.

- Fairclough, Norman. 1989. Language and Power. London: Longman.

- Gafter, Roey J, and Tommaso M. Milani. 2021. “Affective Trouble: A Jewish/Palestinian Heterosexual Wedding Threatening the Israeli Nation-State?” Social Semiotics 31 (5): 710–723.

- The Guardian. 2005. “Spray Can Prankster Tackles Israel’s Security Barrier.” August 5.

- The Guardian. 2017. “Worst View in the World.” Banksy Opens Hotel Overlooking Bethlehem Wall, March 3.

- Hanauer, David I. 2011. “The Discursive Construction of the Separation Wall at Abu Dis.” Journal of Language and Politics 10 (3): 301–321.

- Hansen, Miriam Bratu. 2004. “Room-for-Play: Benjamin’s Gamble with Cinema.” October 109: 3–45.

- Haupt, Adam, Quentin E. Williams, Samy H. Alim, and Emile Jansen. 2019. Neva Again: Hip Hop Art, Activism and Education in Post-Apartheid South Africa. Pretoria: HSRC Press.

- Iedema, Rick. 2003. “Multimodality, Resemiotization: Extending the Analysis of Discourse as Multi-Semiotic Practice.” Visual Communication 2 (1): 29–57.

- Isin, Engin F. 2004. “The Neurotic Citizen.” Citizenship Studies 8 (3): 217–235.

- Jaffe, Alexandra M. 2009. “Entextualization, Mediatization and Authentication: Orthographic Choice in Media Transcripts.” Text & Talk 29: 571–594.

- Jaworski, Adam. 2007. “Language in the Media: Authenticity and Othering.” In Language in the Media: Representations, Identities, Ideologies, edited by Sally Johnson, and Astrid Ensslin, 271–280. London: Continuum.

- Jaworski, Adam, and Crispin Thurlow. 2009. “Taking an Elitist Stance: Ideology and the Discursive Production of Social Distinction.” In Stance: Sociolinguistic Perspectives, edited by Alexandra Jaffe, 195–226. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Jaworski, Adam, and Crispin Thurlow. 2017. Elite Discourse: The Rhetorics of Status, Privilege and Power. London: Routledge.

- Katriel, Tamar. 2020. Defiant Discourse: Speech and Action in Grassroots Activism. London: Routledge.

- Khader, Jamil. 2018. “Dystopian Dark Tourism, Fan Subculture, and the Ongoing Nakba in Banksy's Walled Off Heterotopia.” In Tourism and Hospitality in Conflict Destinations, edited by Rami K. Isaac, Erdinç Çakmak, and Richard Butler, 137–152. London: Routledge.

- Khader, Jamil. 2020. “Architectural Parallax, Neoliberal Politics and the Universality of the Palestinian Struggle: Banksy’s Walled Off Hotel.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 23 (3): 474–494.

- Kiesling, Scott F. 2018. “Masculine Stances and the Linguistics of Affect: On Masculine Ease.” NORMA: International Journal for Masculinity Studies 13 (3-4): 191–212.

- Krotz, Friedrich. 2009. “Mediatization: A Concept with Which to Grasp Media and Societal Change.” In Mediatization: Concept, Changes, Consequences, edited by Knut Lundby, 19–38. New York: Peter Lang.

- Larkin, Craig. 2014. “Jerusalem’s Separation Wall and Global Message Board: Graffiti, Murals, and the Art of Sumud.” The Arab Studies Journal 22 (1): 134–169.

- Light, Duncan. 2017. “Progress in Dark Tourism and Thanatourism Research: An Uneasy Relationship with Heritage Tourism.” Tourism Management 61: 275–301.

- Lisle, Debbie. 2004. “Gazing at Ground Zero: Tourism, Voyeurism and Spectacle.” Journal for Cultural Research 8 (1): 1–19.

- Lou, Jackie. 2021. “What are we Talking about when we Talk about the Commodification of Language?” Invited lecture at the PhD workshop The political economy of language and space/place, University of Gothenburg 6-8 September 2021.

- Lundby, Knut. 2009. “Introduction: ‘mediatization as Key’.” In Mediatization: Concept, Changes, Consequences, edited by Knut Lundby, 1–18. New York: Peter Lang.

- Martin, James. 2014. Politics and Rhetoric: A Critical Introduction. London: Routledge.

- Mazzarella, William. 2004. “Culture, Globalization, Mediation.” Annual Review of Anthropology 33: 345–367.

- McGill, Kenneth. 2013. “Political Economy and Language: A Review of Some Recent Literature.” Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 23 (2): 84–101.

- Mielke, Anelynda. 2017. “Objectifying the Border: Symbolism and Subaltern Experience of Borders in Palestine and Canada.” Borderlands 16 (1): 1–25.

- Milani, Tommaso M. 2020. “Commodified Necropolitics.” Paper presented at the workshop The Discourses and Materialities of Tourism, Bar-Ilan University, 12-14 February 2020.

- Munt, Sally. 2007. Queer Attachments: The Cultural Politics of Shame. London: Routledge.

- Pennycook, Alastair. 2007. “Linguistic Landscapes and the Transgressive Semiotics of Graffiti.” In Linguistic Landscape: Expanding the Scenery, edited by Elana Shohamy, and Durk Gorter, 302–312. London: Routledge.

- Peters, John D. 1997. “Seeing Bifocally: Media, Place, Culture.” In Culture, Power, Place: Explorations in Critical Anthropology, edited by Akhil Gupta, and James Ferguson, 75–92. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Probyn, Elspeth. 2004. “Everyday Shame.” Cultural Studies 18 (2-3): 328–349.

- Ross, Jeffrey I., John F. Lennon, and Ronald Kramer. 2020. “Moving Beyond Banksy and Fairey: Interrogating the Co-Optation and Commodification of Modern Graffiti and Street Art.” Visual Inquiry: Learning & Teaching Art 9 (1-12): 5–23.

- Seidman, Gay. 2016. “Naming, Shaming, Changing the World.” In The SAGE Handbook of Resistance, edited by David Courpasson, and Steven Vallas, 351–366. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Sharma, Bal Krishna. 2021. “The Scarf, Language, and Other Semiotic Assemblages in the Formation of a new Chinatown.” Applied Linguistics Review 12 (1): 65–91.

- Shoaps, Robin. 2009. “Moral Irony and Moral Personhood in Sakapultek Discourse and Culture.” In Stance: Sociolinguistic Perspectives, edited by Alexandra Jaffe, 92–118. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Silverstein, Michael. 1998. “Contemporary Transformations of Local Linguistic Communities.” Annual Review of Anthropology 27: 401–426.

- Spencer-Bennet, Joe. 2018. Moral Talk: Stance and Evaluation in Political Discourse. London: Routledge.

- Tamimi, Sami, and Tara Wigley. 2020. Falastin: A Cookbook. New York: Ten Speed Press.

- Thurlow, Crispin. 2016. “Queering Critical Discourse Studies or/and Performing ‘Post-Class’ Ideologies.” Critical Discourse Studies 13 (5): 485–514.

- Ulisse. 2018. “Art Hotel più belli del mondo.” June.

- Urry, John. 1990. The Tourist Gaze: Leisure and Travel in Contemporary Societies. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Weeks, Lara. 2012. “I am not a Tourist: Aims and Implications of ‘Traveling’.” Tourist Studies 12 (2): 186–203.