ABSTRACT

The purpose of the study was to demonstrate how art could be connected to therapeutic treatment processes. The intervention took place between 2020 and 2021 at an eating disorder (ED) unit in Vaasa Central Hospital, Finland. Eating disorder patients and reference group saw an art video by artist Johanna Ketola depicting nature and mystical features. Participants then discussed thoughts stimulated by the artwork. Participants’ depictions were coded, and content analysis of the written texts was carried out by applying cognitive semiotics blending theory (CSBT). Findings show that the artwork stimulated flexibility of thought, which allowed further possibilities to develop thinking and ways of expression. Art-viewing interventions can help patients find new ways to express themselves. The study shows how CSBT, and art viewing interventions, can be used in the clinical context to analyse meaning-making processes. With such interventions, the patient can develop skills to express one's own personal condition.

Introduction

The aim of this study has been to examine meaning-making during art intervention in a unit for eating disorders at Vaasa Central hospital in Finland. The study also inspects how thinking can be analysed in a clinical setting to identify how patient's meaning-making and reflection of thoughts are formed. The main research question was: How can artwork with activating elements inspire the reflection of thoughts in people with eating disorders compared to caretaking professionals? This was explored by sub-questions: What main observations can be made in the expressions of the groups? What contents come through when analysing participants’ reflections on the artwork? What findings reflect differences between the eating disorder group and the reference group?

Eating disorders (ED), including anorexia, bulimia, and other not clearly specified conditions, are a serious mental health condition. The average prevalence of anorexia nervosa is 0.3% and bulimia nervosa 1% in young females (lower in males). Eating disorder not otherwise specified (ED-NOS, characteristic for anorexia or bulimia but does not meet all criteria) accounts for 60% of all cases. Patients generally suffer from psychological problems for several years after clinical recovery (Isomaa Citation2011).

Art therapy has been effectively used for treatment of eating disorders (see e.g. Prijatna, Satiadarma, and Wati Citation2021). It belongs to the field of psychological therapy that mixes artmaking, creative processes, applied theory of human behaviour and experience, as per The American Art Therapy Association (Citation2017). Art therapy as a method focuses on making art and reflecting on patients’ art creations. Viewing art made by professional artists, drawing themes and ideas from the artworks, and incorporating them into the patients’ personal narratives is not a common practice. Although art-viewing is not an established method in therapy settings, studies (e.g. Timonen and Timonen Citation2021) show benefits from interacting with artworks in the role of viewer. Art is thought to foster self-expression and insight, and the non-threatening properties in art can promote feelings of safety and wellbeing (Thaler et al. Citation2017). This study aims to introduce a content analysis model, applied from cognitive semiotics blending theory (CSBT) to a clinical setting, as a possible model to analyse texts written by mental health patients. It is also of interest to compare the texts with a reference group in case noticeable differences can be seen. This is a slightly different approach to previous art research conducted in the art therapy and mental health sector.

Theoretical background

Meaning-making

It is important to find suitable tools to inspect human conditions, where experiences and characteristics affect how we observe our environment. When it comes to artworks, individual art viewing is one possibility, laced with interpretations and meaning unique to the viewer.

Semiotics as the study of symbolic communication places the viewer of art into the forefront, challenging the idea of intentionality, that artworks objectively depict something, as Curtin (Citation2006) explains. For Mieke Bal, the stories in artworks are in motion and fluctuate through time. She sees art getting its meaning only in interactions with the viewer, which is why artworks receive many different readings in their lifetime. Bal (Citation1994, 150) states that “artwork cannot exist outside the circumstances in which the […] viewer views the images.” She continues that works of art are constructed within always specific contexts of viewing, and the response elicited by the image is not neutral but dependent on the viewer's gender, race, cultural background, and so on (Bal Citation1994).

The classical tradition of fine art typically relies on knowledge of visual and literary sources, although even as early as the Renaissance and Baroque, viewer participation in meaning-making has been acknowledged. This is evident in the reception aesthetics Wolfgang Kemp (Citation1998) made famous. In reception aesthetics, viewer and artwork are seen in a dialogue with each other in a metaphorical sense. This is something that linguists such as Per Linell have also pointed out, but Linell (Citation2009) discusses dialogical interaction in various social contexts while Kemp's focus is on art and aesthetics.

Erwin Panofsky wrote about subjective art – artworks that make the viewer consider their conditions of perception and inner life – as opposed to objective art – artworks that require minimal emotional identification from the viewer (Podro Citation1982). Parsons (Citation2002) emphasized that meaning is not independent of context, because it depends on the viewer and their culture. This is in line with Ernst Gombrich (Citation1960), who related depictions of art to the viewer's background, experience and knowledge, and their schemas.

Jozwiak (Citation2014) suggests that the emotional response a viewer has to an artwork triggers reflections, which give meaning to the piece. In this way, the viewer brings to the work their own context, where both intellectual and emotional responses relate to the person's value system that guides the development of personal meaning. Quoting Beardsley's text in 1981, Jozwiak (Citation2014, 85) brings up the therapeutic value of art experience where it can “generate feelings of personal integrity, resolve lesser conflicts, develop imagination, refine perceptual discrimination, and improve the ability to empathise.” He discusses viewers’ interpretation of artworks as metaphors for their own personal lives.

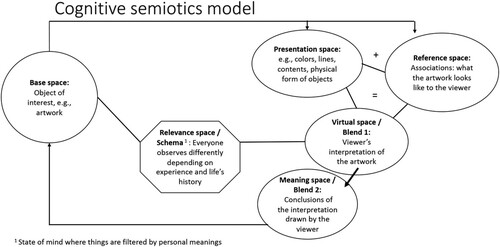

Cognitive semiotics blending theory

Cognitive semiotics studies how signs and other meanings function in human experience, in interaction with the environment as dynamic processes rather than static products (P.A. Brandt Citation2011, Citation2020; Zlatev Citation2012). P.A. Brandt's cognitive semiotics blending theory (CSBT) examines personal meaning-making processes. CSBT uses concepts base -, presentation -, reference -, virtual -, meaning - and relevance space to study how meaning is formed. Space in CSBT refers to mental spaces or frames through which one learns to observe the world. In P.A Brandt's (Citation2011) use of the terminology, space as a production of meaning emerges in thoughts and communications from personal and interpersonal conscious experience in the context where one lives. In CSBT, base space is the starting situation: in language, the spoken or written sentence. Presentation space lists objective elements or the literal meaning of a sentence or an image. Reference space brings interpretation to presentation space, where the content is given meaning. If presentation space is viewed in the sense of semiotic concepts of signifier (physical form: letters, image, verbalization of e.g. a tree) as Line Brandt (Citation2013) suggests, then the reference space is signified (mental concept of a tree). Virtual space, or “blend 1” as it is also referred to, combines presentation and reference spaces together and can be thought of as the sign (combination of signifier and signified: representation of a tree), although as L. Brandt (Citation2013) notes, this is not formally acknowledged, and the signifier/signified equivalents are also not pre-categorized and can be used as the analyst sees fit. Meaning space is sometimes referred to as “blend 2” (Brandt Citation2011).

Brandt and Brandt (Citation2005) refer to Peircean semiotics, seeing Peirce's concepts of representamen, object and interpretant as another way to explain presentation-, reference- and virtual spaces. According to them, the content of virtual space is structured by an interpretant. Interpretant here means the interpreter's understanding of the sign, or a translation of the sign that allows for a more complex understanding of the sign's object, as Atkin put it (Citation2022). Interpretant is important, because it refers to the human factor in understanding signs and interpreting them in meaningful ways. The sign can attain both a primary denoted and a secondary connoted meaning. Connotation, defined by Barthes (Citation1967), is the subjective meaning of the sign that is affected by the interpreter's culture and emotional connection. Therefore, there are often many ways to interpret an artwork, for example.

In CSBT, relevance space is important as it specifies how the sign is to be interpreted. This is affected by the individual's own schemas – the mental structures and frameworks that influence how thoughts are organized. According to L. Brandt (Citation2013), meaning may emerge in virtual space or meaning space. Relevance space or identified schemas may introduce certain “lenses” through which a person views their environment and tries to give an understandable meaning to observations. Meaning is seen as a process that is constantly being reinterpreted. Furthermore, cognitive semioticians claim that it is necessary to focus on semiosis, the process of meaning-making (termed by Peirce, see e.g. Powell Citation1953), rather than merely on signs and sign systems (Konderak Citation2018). In Figure can be seen the CSBT-model applied from Brandt and Brandt (Citation2005).

Figure 1. Summary of the CSBT-model and its main features applied from Brandt and Brandt (Citation2005) to the clinical setting.

About cognition

Cognition (perception, thinking, memory, etc.) must be related to environmental context, where meaning and variations in behaviour in people (and animals) are shaped (Cauchoix, Chaine, and Barragan-Jason Citation2020). Behavioural components, like verbal and non-verbal tools (speech, gestures, mimicry, etc.) and shifting of focus, lead to formation of thoughts and longer lasting belief systems and attitudes (Glass and Holyoak Citation1986). The result can be seen in people's schemas i.e. cognitive frameworks that help organize and interpret information. Schemas can be positive and negative due to their tendency to guide our behaviour (Louis et al. Citation2018). One possibility to analyse schemas is to use Aaron T. Beck's cognitive model (Beck Citation1976). He describes understanding for anxiety and depression by focusing on self-image (or self-esteem) as a main schema. This is identified in three areas (sc. cognitive triangle): reflection about self, others/environment (context), and future. Schemas are visible in modes they generate (e.g. attitudes, behaviours). Many ED patients have anxiety and depression (Sander, Moessner, and Bauer Citation2021), so self-image shows relevance in this context.

To gain understanding of patients’ cognitions, especially thoughts, it is important to examine how associations between different things are formed, which leads to the possibility to reflect thoughts and to modify negatively loaded ones, like Judith S. Beck emphasizes (Citation1995).

Method

Participants

The participants were outpatients with regular visits to the ED-unit between 2020 and 2021, and professionals, who were working personnel with therapeutic contact with patients during that time. The eating disorder group (ED-group; patients) consisted of 16 female participants, ages ranging from 17 to 29, with anorexia nervosa as diagnosis, some had also developed bulimia symptoms. There were 10 professionals in the second group, ages ranging from 27 to 40, somewhat older than patients – two unit-personnel, seven therapists/therapist students, one psychologist, all but one were female. They functioned as a reference group (Ref-group; professionals), against which the ED-group's data was reflected. Four patients used Swedish, and the Ref-group used Finnish in the study. Participants were asked whether they wanted to take part in the study – participation was voluntary.

Setting

A 12 m2 room with white walls was adapted to the intervention. There were dark curtains covering the windows, blankets, large green beanbag chairs, a small drawer with video viewing equipment and two 55″ LG televisions on adjacent walls. The green chairs gave impression of a mossy forest floor. The TV cables were attached to the walls with white tape so attention would not be drawn to them. The televisions were placed at eye level when the person was sitting down. Viewers could choose to use headphones to listen to the sounds while watching the video. The installation ran on Brightsign-mediaplayer with the BrightAuthor software application.

Material

The work used in the study was an art video called Valley L447 (2014–2015) by Johanna Ketola, a contemporary artist from Jämsä, Finland. The video was chosen because it has many ambiguous elements that can be depicted in multiple ways, but also had familiarity for the subjects in terms of the setting (Finnish forest scenery). It was exhibited in art museums and was obtainable from the artist who showed interest in the study. The artist has described her work portraying the relationship between humans, nature, and consumer culture in the twenty-first century (Hippolyte Citation2016). The artwork depicts natural and artificial elements in forest scenes, grazing horses dressed in zebra-striped blankets, and a roaming greyhound in a leopard-striped coat. Humans are shown only from behind as they attempt to blend into the background in tree-patterned hoodies and sweatpants. Some human-made objects, a sculpted owl and a compost camouflaged as a large rock, break the natural scenery. A still image from the video can be seen in .

Figure 2. Still image from Valley L447 (2016) video installation by Johanna Ketola, size varies – published with permission from the artist.

The soundscape of the forest was designed by composer, Petri Alanko. The sounds at first appear natural: rainfall, wind, and bird song, evolving later into something slightly disturbing and unnatural.

Procedure

The participants were instructed to visit the study room one at a time, ED patients accompanied by a nurse, professionals viewed the video by themselves. The participants could choose where to sit and view the video, and were free to spend as much time as they wanted in the room. They were then asked to write down their initial thoughts. The instructor did not give a model for how to view and write, so participants were free to express themselves without any leading questions. All the discussion topics came from the viewers. After the session, ED patients’ discussion topics were further addressed in therapy. On average, the participants spent 15–20 minutes viewing the video and then about 5–10 minutes writing down their thoughts. The art intervention was the only art-related content for the patients during the study period.

Analysis

Round 1

In round 1, an inductive approach to the analysis was taken, and the study subjects’ texts were coded in TAMSAnalyzer (qualitative analysis software, Macintosh). Coding began by finding similar expressions in the texts and grouping them together. Codes that summarize the essential content of the texts were created. Because codes are a system of signals or symbols for communication (a descriptive phrase or word) whose purpose is to reflect expressions (e.g. Miles and Huberman Citation1994), it was important to make sure they diversely described the texts.

Four main categories were formed, which were Positive, Negative, Content-oriented, and Thematic, and the codes were placed under them. The categories made it possible to see the general emphasis of ideas and emotions in the texts. Thematic and Content-oriented as categories list codes that could not be placed under Positive or Negative and were not related to mood.

There were 36 unique codes identified in the categories (see ). 12 codes appear in more than one category because they carried out different qualitative meanings and were interpreted as positive or negative depending on the context (e.g. Affective and Longing).

Table 1. Codes and categories.

Round 2

In round 2, a more thorough qualitative content analysis was conducted using CSBT. First the whole data was examined, then important details identified, which gave the basis for this analysis. The logic here was both deductive and inductive. CSBT introduced by P.A. Brandt and L. Brandt was applied as a method for the analysis. This required some adaptation to suit the purpose of the study. In Brandt and Brandt’s (Citation2005) example, usually one metaphorical sentence (e.g. “the surgeon is a butcher”) is analysed in the six mental spaces to present formation of meaning. The texts in this study were not metaphorical in that sense, although a few metaphorical expressions were present; instead, topics and sentiments were of interest. Full texts were analysed instead of slicing individual sentences artificially into too specific details; the idea was to find out how meaning was formed in the participants’ writings.

Ten main codes were chosen for the content analysis when examining the data more closely. They are like the codes picked in round 1, but these focused on key parts of the data and helped notice unifying topics among the participants. The codes are (1) Calming, (2) Personal life, (3) Distressing/Scary, (4) Human actions as negative, (5) Strangeness/Oddness, (6) Animals, (7) Humans, (8) Finnish/Swedish themes, (9) Globalization, and (10) Camouflage/Observations about hiding and loneliness. These codes appeared in different spaces depending on their emphasis. After the main coding process, possibility of other codes was checked, especially for blends 1 and 2. A more general analysis for the relevance space was conducted by reflecting the findings against the cognitive schema model by Beck (Citation1976).

It was essential to look at the whole sequence of meaning-making in the different mental spaces to gain understanding of the person's thought processes. Base space, the starting situation, was the same for everyone, so it was not included in . Due to the structure and length of the writings, some of the spaces were not always possible to determine in detail. The presentation space sometimes had a general signifier “nature” because there were no other special details, such as trees, rocks, etc., mentioned in the text. References to the codes in Table are underlined.

Table 2. Coding for the content analysis.

The analysis was conducted with the following guidelines: (1) Presentation space: Content, physical form of objects, (horses, tree trunks, cliffs, forest, etc.); (2) Reference space: Associations the presentation space gave the viewer, (e.g. peaceful and calm forest, “cliff looks like a turtle”); (3) Virtual space (blend1): Interpretation of the artwork from the first two spaces, (family's summer cottage, “the tree trunks were people after all … ”); (4) Meaning space (blend2): Conclusions of the interpretations following blend1, (longing for togetherness, human's relationship with nature “is difficult to put into words but in the video, it shows all its sides, evokes feelings”); (5) Relevance space (schema-area): Everyone's observations are slightly different depending on experience and lived history.

Key findings are organized under central topics identified in the analysis.

Reliability and validity

Reliability: The personnel were informed of the study by the unit leader and were given directions on how to instruct the patients in the task. The writings on the artwork were collected in a separate notebook kept in the study room with a writer number, date, and time. The unit leader could relate the writer number to personal information. The data was thoroughly analysed by the main researcher, who was entirely blind concerning the participants’ identities. During the ongoing analysis process, and after the basic analysis, the data was discussed with a senior researcher and inconsistencies in conclusions were reviewed. To gain understanding of the patients’ way of thinking and language use, the findings in the ED-group were verified with the ward personnel.

Validity: One challenge in the analysis was to identify how to separate blends 1 and 2 from each other, as in the phrase “relationship with nature”: whether it is a question of personal relationship or a reference to a more global connection with nature. Thus, the same writing could first be seen to mean both contents. When the phrase was connected to other parts of the text, the difference became clearer, e.g. with emphasis on one's own experiences (blend1) or a general discussion of the role of nature in humans’ lives (blend2). The analysis logic was compared and explored against other examples in CSBT literature by P.A. Brandt (e.g. Citation2011, Citation2020), L. Brandt (e.g. Citation2013), and Stampoulidis, Bolognesi, and Zlatev (Citation2019).

The ethical deliberation was executed by Vaasa Central hospital and the study belongs to the project organized by the Welfare organization in Pohjanmaa.

Results

Codes and categories

The analysis of the texts in round 1 shows 407 mentions of the codes by the ED-group and Ref-group (ED:Ref), (168:239). The codes in the categories were mentioned as follows: 91 Negative mentions (32:59), 78 Positive mentions (39:39); 108 Content-based mentions (40:68); 130 Thematic mentions (57:73). The distribution of codes into categories is represented in .

The three most often mentioned codes were Animal (ED:Ref; 15:20), Nature (12:9) and Calming (7:13). The highest number of mentions in the negative category were from the codes Anxious (2:11), Camouflage (3:10), and Challenging (2:12).

Content-analysis

The numbered codes in indicate how objects in the presentation space can become concepts and attain a connotative or even metaphorical meaning as they go through the process of interpretation. This is based on how expressions in the texts connect to the analysis sequence (presentation space … → meaning space): the different spaces affecting each other, i.e. associations (reference space) being a requisite for interpretations (virtual space). Meaning space cannot be reached without first processing thoughts on more basic levels, and the space is not always discernible.

shows the main observations of the analysis.

In can be seen how descriptions relating to the code (6)Animals dominated in both groups (ED: 25 mentions, Ref: 26 mentions), its meaning seen differently in each space. (1)Calming was another dominating code, but patients mentioned it much more often than the Ref-group (14:6). (3)Distressing/scary as a code had many mentions (8:15) and seemed like an important descriptor of the content. Interestingly, calmness was mentioned by the ED patients much more often than by the Ref-group, whereas distressing and scary feelings were slightly more prominent among the Ref-group, even though that group was smaller. Another interesting code for the study was (2)Personal life (6:1); personal topics were clearly more prominent among the patients. The code and category analysis counted how many times each code was mentioned, while in the content analysis the same code may have appeared in multiple spaces and is thus counted more than once. The latter highlights the significance of emphasis of codes such as “calming.” Patients focused more on calmness, contemplating why the video felt calming, while many professionals mentioned it but did not deliberate on it.

Some clarifying codes were formed after the initial analysis and placed in under blends 1 and/or 2: (a)Contradictory observations, ED:Ref, 3:5 mentions (blends 1/2), (b)Multiple meanings 3:4 (blends 1/2), (c)Playfulness 1:1 (blend1), (d)Contemplative questions/remarks 6:10 (blends 1/2).

The main schema points for the ED-group can be seen falling into Beck’s (Citation1976) observational areas of self, environment/others, and future, indicating mainly negative self-image but also some positive views and attitudes towards the future: “when you find a way out of the forest, you will feel fine again.”

Key findings

The key findings are summarized by the four following topics.

Context, nature

The hypothetical starting point is that nature is widely linked with physical and psychological wellbeing (e.g. Nanda et al. Citation2011), which may explain why many viewed the video in positive tones, even when disturbing associations were found. It bears noting that emotional responses to nature are not straightforwardly positive, especially in the time of climate crisis, which can create feelings of anxiety.

Humans in the video were universally disliked and interpreted as a sign of negativity. One patient wrote that human's relationship with nature “is difficult to put into words but in the video, it shows all its sides, evokes feelings,” this was a conclusion of the interpretation of humans’ “multifaceted relationship with nature” ((b)multiple meanings → (d)contemplative remark), and came from the associations: calmness, joy, fear, powerful, and austere. The humans were presented from behind, faces never visible. According to Mather (Citation2014), viewers immediately focus on faces when they are visible in images, so seeing humans only from behind can feel disturbing and wrong. Positive content included discussions of animals and their interactions.

Body, eating

The artwork gave patients ways to reflect on their conditions, express thoughts about eating, body ideals, loneliness, personal problems, and even memories about past events. Patients also associated the video with physical feelings such as calmness, which “stabilized the heartbeat,” something that the Ref-group did not do.

Similarly, discussions of the patients’ ED habits and body ideals, and one comparing her condition with the grazing horses (“horses need to eat to have energy to play around”), were meaningful. The same patient's interpretation of the horses eating together was that none of them was observing how others were eating. She saw the video evoking feelings of being “stuck” and concluded that “when you find a way out of the forest, you will feel fine again.” This (d)contemplative remark slightly contradicted the associations she made of the forest and animals, which were for the most part positive, though loneliness was one association. Perhaps she was projecting the feeling of being stuck that comes from her ED condition onto the artwork. Another patient interpreted the animals dressed up as others in terms of wanting to be something else (unnatural body ideals → longing away from oneself, (d)contemplative remark).

Professionals did not interpret the video to relate to eating or body, understandably, because they are not afflicted by such thoughts. Their interpretations and associations related to loneliness, fear, contrasts, and coexistence, but also individual differences and beauty within. Professionals made more (a)contradictory observations than patients. It could be that the patients related to the video on a more personal level and were more used to talking about personal feelings because of their ongoing treatment, while the professionals perhaps saw it as an assignment to analyse the artwork.

Personal

There was a clear difference between participants in the ED-group, where some would discuss very personal topics while others would only write that the video was calming and nice to look at. It seems that ED patients tend to protect themselves by controlling information from the environment. Having control is one of the core elements in people with ED (Fairburn Citation2008). Attard (Citation2020) points out that one can repress uncomfortable feelings by putting a positive front for others and not express negative emotions. Emphasis on positive and neutral content also appears in the patients’ texts and can be explained with a common self-image schema mode in ED called the “Pollyanna mode.” According to Simpson (Citation2020), people who fit this mode can “silver-line” even the most difficult circumstances and keep themselves blind to their condition by overcompensating underlying negativity and pessimism.

The video seems to have emphasized loneliness in both groups, as they interpreted the animals as alone and hiding. The Ref-group focused on this idea, but it was also present in the ED-group. These themes were easily identifiable in the video because the artwork brought up elements for this content (e.g. hiding in the forest, dressing in camouflage, rainfall sounds – only a few mentioned the soundscape). The video also showed some (c)playful elements in different ways (e.g. patterns connecting to animals and terrain), interpreted by one patient.

The most interesting discussions of the artwork in therapy context are often those surrounding the patient's history and experiences. When one patient associated the video's landscape with familiarity, interpreting it as alike the forest where her family's summer cottage is, this resurfaced memories that were not in the patient's mind before and could stem new conversations with the therapist.

It is possible to see how meaning of the artwork starts to form in the subjects’ texts with such descriptions as fear, joy, creepy, etc. Distressing and scary themes were emphasized more by the professionals, which can be explained by how the participants have learned to focus on these kinds of clinical situations – ED: focus on optimism, neutrality, tendency to avoid negative feelings; Ref: focus on negative, emotionally loaded contents to discover clinical problems. It is also obvious that the older age of the Ref-group has led to more various learning experiences, which may affect interpretations.

Language, culture

The professionals wrote generally more than the patients. The average number of words written by the patients was 34 and 95 for the professionals. Participants in the Ref-group writing longer and more descriptive texts may relate to differences in attitude towards the intervention or professionals having more tools to express thoughts in writing. This may also support the clinical view that people with ED have difficulty expressing and processing emotions, or it can indicate the need to escape from negative thoughts or hide them from others. Some variation in text length could also be seen in the two language groups. Swedish speakers seemed to go more into detail when describing the video, finding comparisons to their own lives directly and indirectly. Only one Swedish text was similar to the Finnish texts in length and level of discussion. Even though it is not possible to draw conclusions about Swedish and Finnish speakers due to the small sample size, there may be some cultural and linguistic influences affecting how the artwork was discussed by the participants.

Some were affected by the cultural symbolism of the forest, being reminded of Finnish and Swedish literature, where forests act as an integral part of folklore and other stories. One patient associated the forest with Swedish children's literature, her interpretation being that the forest was like the one in Astrid Lindgren's book, “Ronia the Robber's Daughter,” while a slightly older professional interpreted the forest as a “Kalevala (the national epic of Finland) landscape.”

There was also some metaphorical discussion. One professional's conclusion was that the artwork is a “mirror to humanity,” something he came to after interpreting the animals in exotic furs to represent consumerism and globalization. In both groups, an individual (d)contemplated the addition of a sunny beach to the end of the video. The professional suggesting this argued that it would bring a feeling of calmness; for the patient, the sunny beach represented a way out of one's problems and increased feelings of wellness (a much more personal thought).

Discussion

The results indicate that art viewing interventions can give patients new ways to express thoughts and feelings towards their condition, themselves, and the context where they live. After the video session, these discussion topics can be returned to in therapy. The meaning that came out of the video was spontaneous and very personal to some of the viewers. It was rewarding to see how some patients found ways to discuss their disorder through the artwork, albeit almost as a side note, relating to themes of food, eating and even loneliness.

The art video activates observations and associations related to social and cultural ideas, emotions, and personal life. Schemas influence how individuals filter their observations, but observations also build up new schemas when thoughts adapt to new information. These observations can be processed and talked about in therapy to discover the individual's mind and build up new modes (i.e. attitudes and behaviour) to change the content of schemas. It is possible that artworks signal unpredictable paths in thought processes through themes identified within them. This can also increase metaphorical thought. This is important for both the therapist, who can use these discoveries to lead the discussion towards new areas, and the patient, who can hopefully enjoy the art intervention and discuss opinions important to her/himself through the artwork, as could be seen from the results. It is important to note that art-viewing interventions cannot replace psychotherapy. They can be used in addition to other therapy methods when a change to routine is wanted. It is advisable that professionals working with patients get acquainted with the same therapeutic material as their patient (e.g. artworks) to be able to reflect patients’ thoughts against their own.

This study had some challenges. The CSBT model required slight adjustments to fit the analysis of colloquial texts. The assignment was given to the participants by different personnel, so they may have perceived it differently. The analysed texts varied in length, and it was sometimes difficult to place them in the applied analysis model.

It appears that ED patients have an increased need for control (Fairburn Citation2008), and this can hinder free expressions. It is important to provide a space for expressions to find out more about the person's own thoughts without tying them into existing patterns or structures. CSBT provides an opportunity to analyse freely produced expressions and seems like a suitable analysis model for even colloquial texts. With suitable art interventions, it is possible to find out more about the patient's own thoughts and approaches and grasp contents that are more subconscious. When thoughts are shared, social dialogue is reachable between humans.

Concluding remarks

Eating disorders influence interactions in the daily and social life. Cultural ideals often influence how people see themselves, and everyday social problems can emerge and detrimentally affect people suffering from these kinds of mental health problems. Art interventions can offer possibilities to express one's ideas, to develop more advanced language use and generate different creative ways of expression in therapy (e.g. Rosal Citation2018). Cognitive semiotics blending theory is a promising candidate for looking at thoughts emerging in related environments, and it suits a clinical therapeutic setting well, but it requires more real-life examples for it to grow into a more usable method also in healthcare settings. This research area requires interest from stakeholders to be developed further.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks the psychological research group at Pohjanmaa welfare area for contributing to and supporting the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- The American Art Therapy Association. 2017. “The Art Therapy Profession.” Accessed 15 February 2023. https://arttherapy.org/about-art-therapy.

- Atkin, A. 2022. “Peirce’s Theory of Signs.” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2022 Edition), edited by E. N. Zalta and U. Nodelman. Stanford: Metaphysics Research Lab, Department of Philosophy, Stanford University. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2022/entries/peirce-semiotics.

- Attard, A. 2020. “Repressing Emotions: 10 Ways to Reduce Emotional Avoidance.” PositivePsychology.com. Accessed 22 July 2022. https://positivepsychology.com/repress-emotions.

- Bal, M. 1994. On Meaning-Making: Essays in Semiotics. Sonoma: Polebridge Press.

- Barthes, R. 1967. Elements of Semiology. London: Cape Editions.

- Beck, A. T. 1976. Cognitive Therapy and the Emotional Disorders. New York: Meridian.

- Beck, J. S. 1995. Cognitive Therapy: Basics and Beyond. New York: Guilford Press.

- Brandt, P. A. 2011. “What Is Cognitive Semiotics? A New Paradigm in the Study of Meaning.” Signata 2 (2): 49–60. doi:10.4000/signata.526.

- Brandt, L. 2013. The Communicative Mind: A Linguistic Exploration of Conceptual Integration and Meaning Construction. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Brandt, P. A. 2020. Cognitive Semiotics. Signs, Mind and Meaning. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Brandt, L., and P. A. Brandt. 2005. “Making Sense of a Blend: A Cognitive Semiotics Approach to Metaphor.” In Annual Review of Cognitive Linguistics 3, edited by Ruiz de Mendoza Ibáñez, 216–249. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Cauchoix, M., A. S. Chaine, and G. Barragan-Jason. 2020. “Cognition in Context: Plasticity in Cognitive Performance in Response to Ongoing Environmental Variables.” Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 8 (28 April): 1–8. doi:10.3389/fevo.2020.00106.

- Curtin, B. 2006. “Semiotics and Visual Representations.” The Academic Journal of the Faculty of Architecture of Chulalongkorn University 01-2551: 51–62. http://www.arch.chula.ac.th/journal/files/article/lJjpgMx2iiSun103202.pdf.

- Fairburn, C. G. 2008. Cognitive Behavior Therapy and Eating Disorders. New York: Guilford Press.

- Glass, A. L., and K. J. Holyoak. 1986. Cognition. 2nd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Gombrich, E. H. 1960. Art and Illusion. A Study in the Psychology of Pictorial Representation. The A. W. Mellon Lectures in the Fine Arts 1956. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Hippolyte. 2016. 8–31 January 2016 Johanna Ketola Valley L447. Photographic Gallery Hippolyte, Helsinki. Accessed 10 April 2022. https://hippolyte.fi/en/nayttely/johanna-ketola-valley-l447/.

- Isomaa, R. 2011. Eating Disorders, Weight Perception, and Dieting in Adolescence. Turku: Uniprint.

- Jozwiak, J. 2014. “Meaning and Meaning-Making: An Exploration into the Importance of Creative Viewer Response for Art Practice.” PhD diss., London: Goldsmiths College, University of London.

- Kemp, W. 1998. “The Work of Art and Its Beholder: The Methodology of the Aesthetic of Reception.” In The Subjects of Art History: Historical Objects in Contemporary Perspectives, edited by M. A. Cheetham, M. A. Holly, and K. Moxey, 180–196. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Konderak, P. 2018. Mind, Cognition, Semiosis: Ways to Cognitive Semiotics. Lublin: Maria Curie-Sklodowska University Press.

- Linell, P. 2009. Rethinking Language, Mind, and World Dialogically: Interactional and Contextual Theories of Human Sense-Making. Charlotte: Information Age Publishing.

- Louis, J. P., A. M. Wood, G. Lockwood, R. M.-H. Ho, and E. Ferguson. 2018. “Positive Clinical Psychology and Schema Therapy (ST): The Development of the Young Positive Schema Questionnaire (YPSQ) to Complement the Young Schema Questionnaire 3 Short Form (YSQ-S3).” Psychological Assessment 30 (9): 1199–1213. doi:10.1037/pas0000567.

- Mather, G. 2014. The Psychology of Visual Art: Eye, Brain and Art. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Miles, M. B., and M. Huberman. 1994. An Expanded Sourcebook. Qualitative Data Analysis. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

- Nanda, U., S. Eisen, R. S. Zadeh, and D. Owen. 2011. “Effect of Visual Art on Patient Anxiety and Agitation in a Mental Health Facility and Implications for the Business Case.” Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing 18 (5): 386–393. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2850.2010.01682.x.

- Parsons, M. 2002. “Aesthetic Experience and the Construction of Meanings.” Journal of Aesthetic Education 36 (2): 24–37. doi:10.2307/3333755.

- Podro, M. 1982. The Critical Historians of Art. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Powell, S. C. 1953. “Charles S. Peirce, Semiosis, and the ‘Mind’.” ETC: A Review of General Semantics 10 (3): 201–208. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42581088.

- Prijatna, Z. M., M. P. Satiadarma, and L. Wati. 2021. “The Use of Art Therapy in the Treatment of Eating Disorders: A Systematic Review.” Proceedings of the 1st Tarumanagara International Conference on Medicine and Health (TICMIH 2021). Advances in Health Sciences Research 41 (December 1): 103–110. doi:10.2991/ahsr.k.211130.020.

- Rosal, M. L. 2018. Cognitive-Behavioral Art Therapy. From Behaviorism to the Third Wave. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Sander, J., M. Moessner, and S. Bauer. 2021. “Depression, Anxiety and Eating Disorder-Related Impairment: Moderators in Female Adolescents and Young Adults.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18 (5): 2779. doi:10.3390/ijerph18052779.

- Simpson, S. 2020. “Schema Therapy Conceptualisation of Eating Disorders.” In Schema Therapy for Eating Disorders: Theory and Practice for Individual and Group Settings, edited by S. Simpson, and E. Smith, 56–66. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Stampoulidis, G., M. Bolognesi, and J. Zlatev. 2019. “A Cognitive Semiotic Exploration of Metaphors in Greek Street Art.” Cognitive Semiotics 12 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1515/cogsem-2019-2008.

- Thaler, L., C.-E. Drapeau, J. Leclerc, M. Lajeuness, D. Cottier, E. Kahan, N. Ferenczy, and H. Steiger. 2017. “An Adjunctive, Museum-Based Art Therapy Experience in the Treatment of Women with Severe Eating Disorders.” The Arts in Psychotherapy 56 (August): 1–6. doi:10.1016/j.aip.2017.08.002.

- Timonen, K., and T. Timonen. 2021. “Art as Contextual Element in Improving Hospital Patients’ Well-Being: A Scoping Review.” Journal of Applied Arts & Health 12 (2): 177–191. doi:10.1386/jaah_00067_1.

- Zlatev, J. 2012. “Cognitive Semiotics: An Emerging Field for the Transdisciplinary Study of Meaning.” The Public Journal of Semiotics 4 (1): 2–24. doi:10.37693/pjos.2012.4.8837.