ABSTRACT

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Chinese state temporarily locked down physical courtrooms and fully relied on online trials based on videoconference technology. This raises the question of how computer-mediated communication affects the realization of justice. This question is particularly significant for criminal cases, where assessing the credibility of evidence, debating between involved actors, and establishing legal identity heavily affect the life-altering sentence. Based on the systemic functional-multimodal discourse analysis (SF-MDA) of a case recording, this study shows that China’s online courts are textually unregulated, with inscribed unbalanced power relations that favor the judge and/or procurator against the defendants. It also finds ineffective ideational meaning-making, the failure to clarify legal jargon and procedures for defendants, and the lack of defense support. These problems illustrate that the current adoption of videoconferencing technology in criminal trials can seriously undermine the court’s constitutionality and legitimacy. Although online courts are a welcome alternative that can help protect public health and avoid delays in the disposal of cases, their currently disorganized implementation, affordabilities, and technical problems compromise justice.

Introduction

The history of online courts (also known as virtual courts, remote courts, and distance courts) is traced to a bail hearing conducted over a videophone in 1972 in Illinois in the US (Turner Citation2020). China adopted online courts rather late and cautiously. China’s first online criminal trial, which involved a parole case, took place in 2011. Online court practices were gradually promoted in provincial and state-level courts after a new policy on the Smart Court (Zhihui Fayuan) was announced in 2016. However, their application had been restricted to civil disputes related to e-commerce and copyright infringements (Guo Citation2021; Shi, Sourdin, and Li Citation2021; Sung Citation2020).

A drastic change occurred when the COVID-19 pandemic broke out. In 2020, China’s Supreme People’s Court announced the temporary closure of physical courts and issued new regulations that broadened the use of online courts. Newly developed videoconferencing technology was implemented in criminal cases at the preliminary levels of local courts. Because such implementation is untested, problems potentially arise in various parts of the trial process including the confidentiality of defendants and evidence, the liability of witnesses, and communications among parties (Fielding et al. Citation2020; Turner Citation2020). In the past, videoconferencing technology merely functioned as an optional tool to assist trial processes. But in current China, videoconferencing technology operates as the platform for the entire range of court processes – from the pre-trial phase to the final verdict (Guo Citation2021; Yu and Xia Citation2021). China’s first criminal trial that entirely relied on videoconferencing took place on 7 February 2020. As reported by the China Supreme People’s Procuratorate, this case’s judge, procurator, defendant, and attorney (of the defendant) participated in the online trial from separate physical spaces – the physical courtroom, the procuratorate office, the detention center, and the law firm’s office respectively (Yang Citation2020).

This abrupt change raises scholarly and legal questions about videoconferencing technology’s impact on justice. Because court trials often involve life-altering outcomes for defendants, there is an urgent need to understand how videoconferencing technology is reshaping trial processes. For example, it likely affects the meaning construction in the courtroom and reinscribes power relations between court participants. Many legal studies theoretically discuss the constitutionality of defendants’ physical presence and non-presence in criminal courts, but few studies empirically examine defendants’ virtual presence and physical non-presence in online courts (Shi, Sourdin, and Li Citation2021; Sung Citation2020; Xu Citation2017). This study helps fill this research gap; it does so by exploring how the due process of law and communications between court participants are affected by videoconferencing technology.

This study’s empirical dataset is an online court trial recording. We analyze this recording with the framework of “systemic functional-multimodal discourse analysis” (SF-MDA). Building on Halliday’s metafunctional principle of meaning (ideational, interpersonal, and textual levels), SF-MDA is a framework that assesses communicative effectiveness by analyzing how meanings are constructed (Baldry and Thibault Citation2006). SF-MDA conceptualizes various semiotic resources such as audio, gesture, and facial expressions as representational “modes.” The construction of meaning is rarely achieved through words alone but also through the mediation of multiple co-expressing modes (O’Halloran Citation2008). The construction of legal evidence is inherently multimodal and the establishment of legal identities is inseparable from the body language and facial expressions of participants (Matoesian Citation2008). Videoconferencing technology reshapes these context-dependent modes in the online trial process, which in turn affects the use of evidence, legal identities, the defense, the sentencing, and the overall justice of the court.

Literature review

Online criminal courts: advantages and challenges

Studies of the advantages of remote dispute resolution – which began with the use of videophones in the 1970s – primarily investigate economic savings and resource issues (Fielding et al. Citation2020). Immediately before the COVID-19 outbreak, videoconferencing technology in criminal cases was mostly used when the detained defendants need safer, less costly, and/or easier participation in the trial (Davis et al. Citation2015; Poulin Citation2004). Videoconferencing allows greater flexibility in court scheduling, which in turn permits a higher use rate of courtrooms and personnel (Turner Citation2020). Contradictory results have been reported; some cases of online trials take more time than regular trials because of technical malfunctions and constant adjournment (Fielding et al. Citation2020). Despite this, an online survey conducted by Turner (Citation2020) found that over 75% of defense attorneys, judges, and prosecutors in Texas believed that online courts sometimes or always save time or resources for those involved.

Meanwhile, Turner (Citation2020) also reported that a sizable portion of participants was significantly dissatisfied with technology usage – they questioned the reliability and legitimacy of online courts. Regarding reliability, over 83% of the relevant parties reported difficulties in assessing witnesses’ credibility. This has been corroborated by a study that demonstrates that mock jurors rate witness appearance more positively when the testimony is given in person instead of through the video format (Landström, Granhag, and Hartwig Citation2005). Concerns were raised over how poor lighting, the camera angle, and the prison setting (of incarcerated defendants) affect a judge’s perception of a defendant as less credible and/or more dangerous (Nir and Musial Citation2022; Rossner and Tait Citation2023).

Regarding the legitimacy of online courts, studies have reported that the majority of legal participants frequently encountered difficulties in providing solid evidence, investigating them, and presenting cases due to the inability to read or use body language (Davis et al. Citation2015; Turner Citation2020). Furthermore, computer-mediated communication hinders the quality of defense when attorneys cannot establish close relations with their defendants. Defendants are also less likely to fully understand legal proceedings as a result of technology malfunctions, constant distractions, and their compromised presence (Nir and Musial Citation2022). Above all, scholars generally argue that the court should not extensively rely on videoconferencing technology, given videoconferencing’s negative impact on the representation of defendants and the integrity of the justice system (Bannon and Keith Citation2020; Nir and Musial Citation2022; Poulin Citation2004; Turner Citation2020).

In China, the Internet-based smart court was established in 2016 to cope with thriving e-commerce businesses and cross-regional civil disputes (Sung Citation2020). Only after the COVID-19 outbreak have online courts been broadly adopted to cope with the public health crisis and avoid delays in criminal disposition. The use of videoconferencing technology expanded in terms of both breadth and depth; it swiftly went beyond digital documentation to the entire process of digital litigation and criminal trials (Guo Citation2021). The new online courts in China are beginning to attract scholarly analyses. These studies report some similar benefits and problems found by international scholars in Western online courts. Zhuang and Tian (Citation2020) praise online courts for alleviating China’s long-lasting problem of police shortage and improving the efficiency and safety of detention centers. Meanwhile, Yang (Citation2022) problematizes the loss of implicit evidence (e.g. defendants’ gaze and body language), the inability to directly review evidence, and technology malfunctions that block efficient defense. Yang also suspects that the non-standardized and unregulated video angle, size, and layout may unfairly affect the judge’s perception of the defendant.

Multimodality and modes in court rooms

As current studies indicate, major problems of online courts derive from videoconferencing technology’s impact on meaning construction and communication. However, existing studies of videoconferencing technology overwhelmingly focus on distance learning and daily conversation (Hampel and Stickler Citation2012; Martin, Ahlgrim-Delzell, and Budhrani Citation2017; Norris Citation2016; Satar Citation2013). There is a serious lack of theoretical and empirical studies of videoconferencing technology related to legal linguistics. Borrowing from SF-MDA, this study helps fill this gap by developing an analytical framework for studying legal meaning construction.

SF-MDA is a theoretical and analytical framework in which meanings are not only verbally constructed but also realized through the interplay of various modes such as gaze and gesture (O’Halloran Citation2008, Citation2011). Back in 1995, the founder of systemic functional linguistics (i.e. Michael Halliday) already emphasized multimodality in legal linguistics because legal evidence and defendants’ narratives are increasingly multimodal owing to technological development (Hibbitts Citation1995; Matoesian Citation2008). But until the COVID-19 pandemic, most studies in relevant fields still focused on the physical courtroom.

Matoesian (Citation2008) is an early analysis of multimodal legal identity construction. It identifies speech-synchronized gestures through the detailed description of a rape victim’s narrative; it reveals that the ascription of blame is not only carried out through talk but also embodied. In China, He’s (Citation2020) paper on multimodality transcripts of a court hearing reveals how the defendant drastically changes the linguistic mode of tone to express a sense of guilt when undeniable evidence transpires. Yuan (Citation2019) employs SF-MDA to comparatively analyze meaning constructions in Chinese and American courtrooms through verbal and spatial modes. On the interpersonal meaning level, Chinese legal actors tend to reply with gaze-shifting to convey power relations and judgments. Tone, pitch, and body language are less often used. Yuan (Citation2019) also indicates the salient role played by the courtroom layout: Chinese courtrooms require legal actors to sit behind desks, which resembles an inquisitorial lecture hall, whereas the frequent use of gestures and body language in American courtrooms shows characteristics of an adversarial battlefield.

The shift toward online courts has extensively reformatted the legal communication platform, transformed the courtroom layout, and eliminated whole-body movements (Guichon and Cohen Citation2016; Hampel and Stickler Citation2012; Norris and Pirini Citation2017). Considering the significant role that modes play in legal discourse for physical courts, how metafunctional meanings are constructed in videoconferencing technology-based online courts requires rigorous examination.

Case briefing

This study analyzes the recording of an online criminal court trial that occurred in a primary-level court in 2021 in China. This trial case was selected because it showcases the untested but full adoption of videoconferencing technology in criminal courts. Many procedures were unregulated in 2021 and most of them remain unregulated now in 2023. Because online courts are still in the experimental stage with restrictions of “case complexity,” we choose a commonplace case instead of a high-profile one (Supreme People’s Court of China Citation2021). At the current stage, a common guilty plea case represents a larger portion of online court cases than high-profile cases.

The two defendants were accused of facilitating online money laundering by using their bank accounts as illegal funds transfer channels in 2020. A procuratorate investigation was conducted in 2021 with both defendants signing guilty pleas. The recorded trial was held for a collegial panel to make the sentence decision. It was openly livestreamed on the China Trial Online Website, with recordings open for review. It was a real-time trial. Throughout the entire process, all participants were separately located in different physical places. The only communication tool was a videoconferencing technology-based platform. The hearing lasted for 32 min with four major participants. Every aspect of the court hearing – examination, investigation, and debate – was fully carried out online. This online trial offers us a case of complex and dynamic ideational and interpersonal meaning construction. For clarity’s sake, we refer to the four major participants by their roles, namely the Judge, the Procurator, Defendant A (located in the upper right area of the screen), and Defendant B (located at the lower right area of the screen). Procurators (公诉人, 检察官) in China are charged with both the investigation and prosecution of crime. They resemble the prosecutor in common-law contexts. However, procurators are not independent lawyers but representatives of the state.

Theoretical framework

This study’s theoretical framework is SF-MDA. SF-MDA involves formulating systematic descriptions of the selected semiotic resources to fulfill the realization of ideational, interpersonal, and textual meanings. Moreover, it allows multimodal texts to be annotated multiple times, as meanings often arise from combined semiotic interactions (Jewitt, Bezemer, and O’Halloran Citation2016). However, for online trials, spoken language is arguably the most important mode used, and it is impossible to incorporate all modes into this study’s discussion (Norris and Pirini Citation2017). This study takes the metafunctional analysis of He’s (Citation2020), which adapted SF-MDA to legal discourse analysis, as a reference. We selected four most frequently appearing modes for analysis, each of which has been identified as salient in the previous literature review.

Metafunction

The ideational meaning of a court hearing is developed by all participants in the litigation, based on relevant legal facts, during the presentation of evidence, debates, and sentencing. Namely, the entire process of a legal hearing can be interpreted as the construction of the ideational meaning of legal facts (Martin and Zappavigna Citation2016).

Interpersonal meaning is an aggregate of the relations between each participant’s identity, status, purpose, emotion, and attitude toward the trial. It is mainly manifested in the triangular relationship between the judge, procurator, and the defense – namely, the neutrality of the judge and the confrontation between the procurator and the defense (He Citation2020).

The coherent organization of the trial proceedings is at the same time the construction of textual meaning. In legal discourse, it entails the gravity of the courtroom, the standard procedural steps to ensure justice, and the cultural norms in the local (Chinese) context (O’Halloran Citation2011).

Semiotic resources

The number of usages of modes – including verbal, visual, gestural, linguistic, and spatial modes – is unmanageably large in the 32-minute video recording of our case. All these usages of modes contribute to the eventual sentencing. But following the example of current studies on multimodality in legal settings such as He (Citation2020), we only focus on the following four semiotic resources, separately and jointly.

Verbal mode – Spoken words: Court trials are primarily verbal communication; it is through words that most ideational and interpersonal meanings are achieved (Bergeron Citation2021; Ehrlich Citation2003). The basic units for analyzing spoken language include the speech of the Judge, the Procurator, Defendant A, and Defendant B, and the background voice of other court personnel for textual meaning cohesion.

Visual mode – layout: As this open trial is presented online in video format, the layout of each participant’s camera resembles the courtroom layout. This plays a significant role in displaying power relations (Poulin Citation2004; Zheng Citation2014).

Gestural mode: This includes both the gesture (or the lack of gesture, as the camera angle only captures the upper half of the body) and the facial expressions of the four participants. The heavy impact of gestural modes on meaning construction cannot be overlooked. As found in studies of physical courtrooms, gestures sometimes play a superordinate role over language (Matoesian Citation2008, Citation2010; Nir and Musial Citation2022).

Distractions and interruptions: As Nir and Musial (Citation2022) report, technological problems were noted in all 44 observational journals on online courts in the US. Similarly, Fielding et al. (Citation2020) show that online courts may cause serious time delays due to technical malfunctions. It should be mentioned that all incidents of distraction (e.g. blurry images, frozen screens) are part of the hearing process and are thus already integrated into the construction of meanings. We dedicate a separate discussion to distractions and interruptions because equipment quality is one of the most significant yet understudied features of applied videoconferencing technology.

Results and discussion

Textual meaning

The construction of textual meaning in an online court may be approached in terms of two meaning construction tasks: (1) to ensure a coherent structure of trial proceedings, and (2) to build up background knowledge for audiences of the livestreaming and the recorded trial. Based on our analysis of the initial information checking period (which lasts for around ten minutes) of this trial, we find that the two tasks are barely accomplished due to the inaudible court announcement and the unregulated layout of the livestreaming screen.

The online trial begins with a muttered voice reading out an announcement; this lasts from 14″ of the video clip of the trial to 1′ 35″. After confirming with a judge, the muttered voice announces the “Notice on Appearance in Court.” The Notice specifies 11 rules on the dos (Rule 1–5) and don’ts (Rule 6–11) during the trial. No audiences are permitted on the site. Yet, Rules No. 7, 8, and 9 are still directed at their appearance.

| (7) | During the court session, auditors are not allowed to audio record, video record, or take photographs, to walk around or enter the trial area without permission, or to make speeches, raise questions, applause, make noise, or do any other acts that may hinder the trial. | ||||

| (8) | Without the permission of the presiding judge or the sole judge, journalists are not allowed to audio record, video record, or take photographs. | ||||

| (9) | For those who violate court rules, the presiding judge or sole judge may deliver verbal warnings and admonitions; confiscate audio, video, and photographic equipment, instruct order to exclude the relevant persons from the court; or impose fines or detention upon the approval of the chief judge. | ||||

Regarding textual meaning, the Court Notice announcement can be considered a social ritual that describes and prescribes court rules (Guo Citation2021). The major purpose is to uphold solemnity and legitimacy. However, in this online trial, the voice quality of the announcement is too poor to accomplish this purpose. Moreover, the announcement fails to provide any textual and cultural norm information. For online audiences, the content is also irrelevant. In physical courts, the arrangement of sitting positions is a strong indicator of power relations. As noted by Poulin (Citation2004), online courts may achieve an analogous arrangement by adjusting the layout of the screen, subtitles, and sizes of various participants on the screen.

However, this does not happen in our case. Only the Judge’s identity is provided; it is marked on the lower left of the screen (See ). On the upper left, a mysterious participant occupies 4/9 of the space on the screen. But no sign or information is given to identify her, who remained silent during the entire trial. Participants who speak and act: the Judge, the Procurator, Defendant A, and Defendant B respectively occupied one-ninth of the screen space. Additionally, the identities of the Procurator, Defendant A, and Defendant B are not provided. Audiences can only speculate who they are based on what they said. By January 2023, over 400 online criminal trial recordings are posted already on the China Court Trial Online website. Yet, screen display protocols and relevant regulations that provide the necessary information for court participants and audiences are still seriously lacking.

Interpersonal meaning

Yuan (Citation2019) finds that Chinese courtrooms are like lecture halls wherein the judge and procurators give lessons to the defendant through forceful language and sharp gazes. This study’s analysis yields a similar finding. A problem of Yuan (Citation2019) and similar studies is that their analyses neglect to take into account the defendant’s experiences (Turner Citation2020). Our following analysis avoids this pitfall by robustly drawing from the defendant’s perspective. It puts into relief how hierarchical forms of communication are imposed on the defendant to achieve order and obedience in the court.

The first relevant incident occurred when Defendant A grinned or laughed three times during the first five minutes of the trial. Each of the grinning and laughing is followed by a warning from the Judge. Grinning is considered an outright contempt of court. As shown in Excerpts 1 and 2, the first instance of grinning occurred during the initial 15 s of the trial ().

The Criminal Tribunal of the People’s Court of W District, X City begins now. The court rules have just been announced. Defendant A, why are you laughing there?

X市W区人民法院刑事审判庭现在开始,首先刚才,法庭纪律已经宣读了,A你在那儿笑啥呢。

Defendant A, you really like laughing. Why not let us stop the trial? You can laugh all you want before we restart.

你很好笑,要不咱庭先不用开了,你笑够了再开。

The second relevant incident involved an interaction between the Procurator and the Defendants. The issue of respect for the court is brought up twice by the judge as the trial proceeds, with the implied interpersonal meaning of mandatory compliance. After the Procurator read out the bill of indictment, Defendant B raised his hand and said “I have an objection.” He argued that the alleged total amount of money involved in this Internet fraud was wrongly calculated. Defendant A reported a similar issue, claiming that his bank’s relevant bills were around 300,000 RMB instead of the alleged amount of 800,000 RMB. The confrontational relationship between the Procurator and the defendants was multimodally displayed. The Procurator responded in an aggressive tone by raising his voice and pitch; he moved closer to the camera, with his gaze fixated on the screen and repeatedly calling out the defendants’ names. The Procurator pressured the defendants by saying “Do you understand now?” four times – this vividly reveals the interpersonal dynamics between the powerful Procurator and the lawyer-less Defendants, who were reprimanded for raising “stupid” arguments ().

To temporarily set aside this dispute, the Judge responded with the hypothetical modal verb of promising a separate decision later, while problematizing the Defendants’ attitudes.

Before we continue, I want to say something to the Defendants. We do not mean to force you. Since the Defendants have signed a plea agreement at the procuratorial stage, the Procurator has also made sentencing suggestions. […] The court will consider the case’s facts, today’s trial process, and the Defendants’ attitudes toward confession to make a comprehensive collegial judgment later. Therefore, I want the two Defendants to remember to take this court and the case seriously and truthfully. Today is your last chance.

在就这之前,我想给被告人示明一下,咱没有任何就是强迫你的意思,鉴于这个检察环节的被告人都签订了认罪认罚,检察机关也对量刑提出了建议 … 我们法庭呢会结合案件情况,结合今天的庭审情况,就是包括被告人认罪态度,我们再进行一个综合的合议评判,所以说,给二被告人想说明一下就是,认真的,实事求是的针对这个案件的情况,今天是你们最后一个机会。

The third relevant incident occurred near the end of the trial. When the two Defendants were signing and confirming the trial transcript, the Judge raised the attitude issue again to criticize Defendant B for his confrontation with the Procurator. Defendant B was admonished for “not acting very well in today’s trial.” This moral stance adopted by the Judge exactly corroborates Yuan’s (Citation2019) argument that the contemporary Chinese trial is hierarchical and inquisitorial. The judge and/or procurators lecture the defendants using forceful speech. Additionally, when an issue concerning sentence leveling arose, the Procurator expressed his impatience through linguistic resources such as frowning, tonic salience, pitch, and volume variation. He repeatedly questioned the defendant’s ability to comprehend what he said. The Judge, rather than investigating and addressing this dispute, purposefully avoided the defendants’ arguments. She responded through modal verbs such as she “shall decide later” while simultaneously signaling the court’s power to maintain order and obedience.

It is found that in physical Chinese courtrooms, where the typical layout and sitting arrangement obstruct large body movements, body language is scantily used (Yuan Citation2019). This contrast with courtrooms in the West. As many studies of multimodality show, American courtrooms tend to be adversarial and participants preferred acting over mere talking to impress the jury (Ehrlich Citation2003; Martin et al. Citation2013; Matoesian Citation2008, Citation2010). Large body movements are even more constricted in the Chinese online courtroom. This constriction succinctly illustrates the power asymmetry and the superficiality of Chinese online courts. In our case, in which the Judge and Procurator acted as representatives of the state, had very limited upper body movements. The movements were confined to constantly searching, flipping, and reviewing printed case files with their gaze fixed on documents. Except when they questioned and confronted the two Defendants, they did not look into the camera. Their singular focus on printed materials, their lack of bodily and head movements, and their suppression of argumentation (by using the plea deal to legitimize the sentence leveling, for example) made the trial merely symbolic or ornamental. The trial did not look or operate like a meaningful process that shaped the outcome through debate and evidence. The two Defendants had slightly more active bodily movements. But such movements were either considered as “non-serious” or completely dismissed, as we will later show.

Ideational meaning

The construction of ideational meaning is essential for the reaching of a sentence; an effective construction of ideational meaning promotes the realization of justice (He Citation2020). Courtroom trials primarily proceed through legal discourses and dialogue. Current studies have pointed out that defendants may not fully understand the legal jargon (particularly in verbal mode) in online trials because their support from lawyers is greatly restricted (Davis et al. Citation2015; Turner Citation2020). This problem is exacerbated in China because according to China’s 1996 Criminal Law, only economically or physically vulnerable persons can receive legal aid. Consequently, the Defendants of our case lacked legal aid. This section demonstrates how videoconferencing technology compromises legal communication and the quality of self-defense. These problems ultimately undermine the online court’s constitutionality and obstruct the due process of law (Poulin Citation2004).

During the process [of signing the guilty plea deal], did your lawyer provide you with any help?

那在你这个过程中,律师给你提供帮助了没有?

No.

没有。

Oh? Was the lawyer present or not?

啊?律师在场不在?

The lawyer confirmed that it happened.

律师证实,有这事儿。

Was the lawyer present or not?

律师在场不在?

Yes, the lawyer was present.

律师在场啊。

For this trial, you are doing self-defense. You do not need a lawyer to defend you, right?

这一次是自我辩护,不需要律师给你辩护了,是不是?

I thought that when a lawyer was assigned earlier, he or she would defend me. I do not know if we can contact him or her over the phone.

我以为,以为当时指派那个,指派那个律师的情况下,他会给我辩护,不知道联系到电话了没有。

That means you have agreed to self-defense, right?

等于你已经同意自我辩护了,是不是?

Hmm.

嗯。

Excerpt 5 illustrates another instance in which the judge undermines the construction of ideational meaning in online courts. The Judge interrupted Defendant B when Defendant B tried to express his opinion on the sentencing.

Do you have any recommendations on the crime and sentencing that the Procuratorate is charging you with?

检察院指控你的犯罪事实以及对你的量刑有啥建议没有?

Do you mean whether I have any opinions?

有啥意见没有?

Regarding sentencing recommendation—do you have any opinions? Or the facts that you are charged with?

对这个量刑建议有啥意见没有,就是指控你的犯罪事实。

Regarding the crime, I admit there is such a thing. But regarding the sentencing …

犯罪事实,我承认有这事,那你量刑 … .

Regarding sentencing recommendation—do you have any opinions? The Procurator has already signed a plea deal with you. Do you have any opinions?

量刑建议这个,你有啥意见没有,检察院不跟你签了吗,有啥意见没有。

What opinions can I have? They are government affairs.

哪能有啥意见呢,公家的事。

You do not have any opinions? Oh? Ah, ah, ah.

没有啥意见吧?啊?哦哦哦

No.

没有。

As previously discussed, Defendant B queried the court’s miscalculation of the monetary amount involved in the case. Defendant B said it might be a double-counting problem and then made the hand sign of “two” with two fingers. The Procurator impatiently interrupted him and explained that the extra amount of illegally transferred money involved “a separate case” (另案处理). As the Procurator asked “Do you understand now?” four times, Defendant B awkwardly waved his hand and said, “I do not understand what you mean by a separate case.” This confrontation was temporarily avoided as the Judge suggested a reconsideration of the sentencing level. Nonetheless, on the level of ideational meaning construction, Defendant B was still confused with the legal jargon of the “separate case.” He raised his hand to bring up this issue again before signing the court transcript. Although the trial lasted for 32 min and had adequate time for elaboration, explanations were not given to properly guarantee a voluntary, informed, and factually-based guilty plea.

Additionally, Chinese online court platforms do not have a hand-raise function to attract attention, unlike the Zoom platform used in the US (Nir and Musial Citation2022). Defendant B employed multimodal resources through hand movements to raise objections or express questions. But these movements and expressions were repeatedly ignored by the Judge and the Procurator, whose attention was fixated on printed documents. Body movements bear significant importance in physical courts when gestures are readily acknowledged as a part of meaning construction. However, body movements can be more easily dismissed when they are staged two-dimensionally on a small part of the video screen ().

Our analysis also shows that the due process of examining the reliability of evidence is undermined in online courts. The submission and presentation of evidence are crucial for sentence-leveling in the court. Excerpt 6 demonstrates that in our case, guidance on evidence submission is so seriously lacking that the Defendants completely failed to make use of this part of the due process.

Do you have any evidence to submit to the court?

你们两个有啥证据向法庭具交没有?

I … I do not even know what procedures there are and what can be submitted. I cannot submit anything.

我,我都不懂有什么程序,能提交什么,我啥也提交不了。

Interruption and distraction

Two major problems have been identified in the technical adoption of videoconferencing technology in online trials: technical malfunctions and continuous distractions from the external environment (Nir and Musial Citation2022; Turner Citation2020). Our analysis of online courts in China yields similar findings. We highlight three aspects of our findings.

Firstly, we find that the poor-quality communication afforded by videoconferencing technology causes delay and repetition. In the first ten minutes of the video clip, the one-word question sentence “啊” and “诶” – both of which may be roughly translated as “Oh?” – appeared nine times. This shows that utterances made by the participants were not clearly heard by each other. Furthermore, after the first two minutes of background vocals, interruptions occurred seven times in the following eight minutes. Each interruption delayed the trial for 11 s on average. This means that in each minute of the trial, at least one-sixth of the time is wasted on double-checking and repeating what was said.

Secondly, we find that online connection interruptions cause the participants to miss important content – this phenomenon is also observed by Turner (Citation2020). As the trial went into the court investigation phase, the audio quality of the Procurator’s explanation (which lasted 36 s) was too poor to be audible. Our brief calculation of audio and connection issues reveals that in the last 20 min of the trial, there are 13 repetitions of sentences and 16 technical interruptions of the speaker’s speech. Relatedly, this might be a part of the reason that the Procurator had to repeat the question “Do you understand now” four times. He might be unsure whether the Defendants could hear his counterarguments in the poor-quality communicative context. In the chaotic online context, the Defendants’ responses also became inaudible.

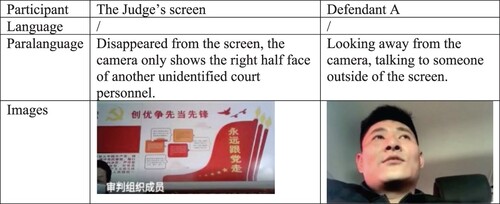

Thirdly, we find that the supposedly semi-closed environment of the court is seriously disrupted by the external environment. The participants were repeatedly distracted from the trial by different persons located outside the camera shot. We could not observe who these disruptors were and what they said. Regardless of who they are, these disruptions undermined the legitimacy and reliability of the court. There were six instances when we see Defendant A looking above the camera away from the screen. His lips were moving, which indicated that he was speaking. But he muted these conversations. is a screenshot that shows the Procurator reading the indictment statement when Defendant A was speaking to an unknown disruptor who we could not observe. Meanwhile, the Judge disappeared from her screen and was replaced with the face of an unidentified court personnel.

While external distractions negatively affect an online trial in various ways, they most seriously affect the defendant. Distractions can undermine defendants’ reliability because the identity of the person to which a defendant speak and the content of the conversation may be deemed to conflict with due process. Moreover, by undermining the defendant’s concentration and proper behavior, distractions can leave negative impressions on the audience, the jury, and the judge. Apart from the defendant, all participants in an online trial can be distracted. In our case, the Judge was distracted as well (and left the screen for 23 s); she did not notice the external distraction of Defendant A.

Conclusion

Triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic, China initiated an unprecedented shift from physical courts to videoconferencing-based online courts. This led to considerable uncertainties, challenges, and problems. Based on the analysis of a criminal trial recording, this study shows that current online courts are unregulated and chaotic in their modes and layout. We find that some defendants feel that the online trial is weird and funny. We confirm that China’s online courts – just like China’s physical courts – resemble lecture halls in which the judge and procurator use forceful language to subdue defendants and gain compliance. We also find that body language is constricted by videoconferencing technology’s affordances and ignored by the judge. This results in trials that resemble ceremonial shows rather than substantive legal deliberation. Importantly, our analysis shows that ideational meaning construction in online trials undermines legal support for the defendant. This problem seriously threatens the legitimacy and constitutionality of the justice system.

This research has the limitation of investigating only one online trial case. Our findings are preliminary for the research field of Chinese online courts. They should not be generalized at the national or global level. Meanwhile, online courts are likely to continue in China with the state’s investment in smart courts (Baldwin et al. Citation2020; Yu and Xia Citation2021). Our findings are timely and needed. They strongly demonstrate that if online criminal courts remain after the pandemic, special regulations and practices should be developed to address the many problems we identified, protect the defendant’s constitutional rights, and maintain the integrity of the justice system.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers and editor for their invaluable comments and kind help during the reviewing process.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Alyousef, Hesham S., and Suliman M. Alnasser. 2015. “A Study of Cohesion in International Postgraduate Business Students’ Multimodal Written Texts: An SF-MDA of a Key Topic in Finance.” The Buckingham Journal of Language and Linguistics 8:56–78. https://doi.org/10.5750/bjll.v1i0.1047.

- Baldry, Anthony P., and Paul J. Thibault. 2006. Multimodal Transcription and Text Analysis. London: Equinox.

- Baldwin, Julie M., John M. Eassey, and Erika J. Brooke. 2020. “Court Operations During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” American Journal of Criminal Justice 45:743–758. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-020-09553-1.

- Bannon, Alicia L., and Douglas Keith. 2020. “Remote Court: Principles for Virtual Proceedings During the COVID-19 Pandemic and Beyond.” Northwest University Law Review 115 (6): 1875–1920.

- Bergeron, Pierre H. 2021. “COVID-19, Zoom, and Appellate Oral Argument: Is the Future Virtual?” Journal of Appellate Practice and Process 21 (1): 193–224.

- Davis, Robin, Billie Jo Matelevich-Hoang, Alexandra Barton, Sara Debus-Sherrill, and Emily Niedzwiecki. 2015. Research on Videoconferencing at Post-Arraignment Release Hearings: Phase I Final Report. https://www.ojp.gov/library/publications/research-videoconferencing-post-arraignment-release-hearings-phase-i-final.

- Ehrlich, Susan L. 2003. Reproducing Rape: Language and Sexual Consent. New York: Routledge.

- Fielding, Nigel, Sabine Braun, Graham Hieke, and Chelsea Mainwaring. 2020. “Video Enabled Justice Evaluation.” Sussex Police and Crime Commissioner and University of Surrey. https://www.sussex-pcc.gov.uk/media/4851/vej-final-report-ver-11b.pdf.

- Guichon, Nicolas, and Cathy Cohen. 2016. “Multimodality and CALL.” In The Routledge Handbook of Language Learning and Technology, edited by Fiona Farr and Liam Murray, 509–521. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- Guo, Meirong. 2021. “Internet Court’s Challenges and Future in China.” Computer Law & Security Review 40:105522. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clsr.2020.105522.

- Hampel, Regine, and Ursula Stickler. 2012. “The Use of Videoconferencing to Support Multimodal Interaction in an Online Language Classroom.” ReCALL 24 (2): 116–137. https://doi.org/10.1017/S095834401200002X.

- He, Jingqiu. 2020. “刑事法庭审判话语的多模态意义构建” [Multimodal Meaning Construction of Trial Discourse in Criminal Courts]. Liaoning Shifan Xuebao 43 (2): 126–131.

- Hibbitts, Bernard J. 1995. “Making Motions: The Embodiment of Law in Gestures.” Journal of Contemporary Legal Issues 6:51–81.

- Jewitt, Carey, Jeff Bezemer, and Kay L. O'Halloran. 2016. Introducing Multimodality. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- Landström, Sara, Pär Anders Granhag, and Maria Hartwig. 2005. “Witnesses Appearing Live Versus on Video: Effects on Observers’ Perception, Veracity Assessments and Memory.” Applied Cognitive Psychology 19 (7): 913–933. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.1131.

- Martin, Florence, Lynn Ahlgrim-Delzell, and Kiran Budhrani. 2017. “Systematic Review of Two Decades (1995 to 2014) of Research on Synchronous Online Learning.” American Journal of Distance Education 31 (1): 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923647.2017.1264807.

- Martin, James R., and Michele Zappavigna. 2016. “Exploring Restorative Justice: Dialectics of Theory and Practice.” International Journal of Speech, Language and the Law 23 (2): 217–244.

- Martin, James R., Michele Zappavigna, Paul Dwyer, and Chris Cléirigh. 2013. “Users in Uses of Language: Embodied Identity in Youth Justice Conferencing.” Text & Talk 33 (4-5): 467–496. https://doi.org/10.1515/text-2013-0022.

- Matoesian, Gregory M. 2008. “You Might Win the Battle but Lose the War: Multimodal, Interactive, and Extralinguistic Aspects of Witness Resistance.” Journal of English Linguistics 36 (3): 195–219. https://doi.org/10.1177/0075424208321202.

- Matoesian, Gregory M. 2010. “Multimodality and Forensic Linguistics – Multimodal Aspects of Victim’s Narrative in Direct Examination.” In The Routledge Handbook of Forensic Linguistics, edited by Malcolm Coulthard and Alison Johnson, 569–585. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- Nir, Esther, and Jennifer Musial. 2022. “Zooming In: Courtrooms and Defendants’ Rights During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Social & Legal Studies 31 (5): 725–745. https://doi.org/10.1177/09646639221076099.

- Norris, Sigrid. 2016. “Concepts in Multimodal Discourse Analysis with Examples from Video Conferencing.” Yearbook of the Poznan Linguistic Meeting 2 (1): 141–165. https://doi.org/10.1515/yplm-2016-0007.

- Norris, Sigrid, and Jesse Poono Pirini. 2017. “Communicating Knowledge, Getting Attention, and Negotiating Disagreement via Videoconferencing Technology: A Multimodal Analysis” Journal of Organizational Knowledge Communication 3 (1): 23–48. https://doi.org/10.7146/jookc.v3i1.23876.

- O’Halloran, Kay L. 2008. “Systemic Functional-Multimodal Discourse Analysis (SF-MDA): Constructing Ideational Meaning Using Language and Visual Imagery.” Visual Communication 7 (4): 443–475. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470357208096210.

- O’Halloran, Kay L. 2011. “Multimodal Discourse Analysis.” In The Bloomsbury Handbook of Discourse Analysis, edited by Ken Hyland, Brian Paltridge, and Lillian Wong, 249–282. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- Poulin, Anne B. 2004. “Criminal Justice and Videoconferencing Technology: The Remote Defendant.” Tulane Law Review 78 (4): 1089–1168.

- Rossner, Meredith, and David Tait. 2023. “Presence and Participation in a Virtual Court.” Criminology & Criminal Justice 23 (1): 135–157. https://doi.org/10.1177/17488958211017372.

- Satar, Müge. 2013. “Multimodal Language Learner Interactions Via Desktop Videoconferencing within a Framework of Social Presence: Gaze.” ReCALL 25 (1): 122–142. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0958344012000286.

- Shi, Changqing, Tania Sourdin, and Bin Li. 2021. “The Smart Court-A New Pathway to Justice in China?” International Journal for Court Administration 12 (1): 1–19. https://doi.org/10.36745/ijca.308.

- Sung, Huang-Chih. 2020. “Can Online Courts Promote Access to Justice? A Case Study of the Internet Courts in China.” Computer Law & Security Review 39 (1): 105461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clsr.2020.105461.

- Supreme People’s Court of China. 2021. “人民法院在线诉讼规则” [Regulations on Online Trials at People’s Court of China]. Accessed January 29, 2023. https://www.court.gov.cn/zixun-xiangqing-309551.html.

- Turner, Jenia I. 2020. “Remote Criminal Justice.” Texas Tech Law Review 53:197–271.

- Xu, Alison. 2017. “Chinese Judicial Justice on the Cloud: A Future Call or a Pandora’s Box? An Analysis of the ‘Intelligent Court System’ of China.” Information & Communications Technology Law 26 (1): 59–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600834.2017.1269873.

- Yang, Lujia. 2020. “重拳出击·严惩破坏防疫犯罪,远程视频开庭审理一起防疫物资诈骗案” [Harsh Law Enforcement: Remote Criminal Trials to Severely Punish Crimes that Undermine Pandemic Prevention]. The Supreme People’s Procuratorate of the People’s Republic of China Online. Accessed January 1, 2023. https://www.spp.gov.cn/spp/zdgz/202002/t20200208_453960.shtml.

- Yang, Ting. 2022. “刑事案件在线庭审的问题检视与规则优化” [Review of the Problems and Suggestion of Online Trials in Criminal Court]. Zhongnan Minzu Daxue Xueshu Xuebao 42 (1): 118–128. https://doi.org/10.19898/j.cnki.42-1704/C.2022.0115.

- Yu, Jia, and Jun Xia. 2021. “E-justice Evaluation Factors: The Case of Smart Court of China.” Information Development 37 (4): 658–670. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266666920967387.

- Yuan, Chuanyou. 2019. “A Battlefield or a Lecture Hall? A Contrastive Multimodal Discourse Analysis of Courtroom Trials.” Social Semiotics 29 (5): 645–669. https://doi.org/10.1080/10350330.2018.1504653.

- Zheng, Ying-Long. 2014. “Courtroom Setups in China’s Criminal Trials.” Semiotica 201:299–322. https://doi.org/10.1515/sem-2014-0021.

- Zhuang, Xulong, and Ran Tian. 2020. “疫情期间刑事案件“视频庭审”的正当性” [The Legitimacy of Video Trials in Criminal Cases During the Pandemic]. Falv Shiyong 5 (1): 57–64.