ABSTRACT

This paper examines language ideologies – sets of normative beliefs about language and its speakers – in a Finnish university student union’s Facebook communication practices. Prior research has discussed how today’s Nordic universities appear to be caught in an ideological tension between the preservation of ethnolinguistic nationalism and the pursuit of internationalization through the use of English. We are interested in the case of university student unions in the changing landscape of communication practices today. We analyzed the student union’s Facebook posts using critical discursive psychology. Our analysis identifies the university’s Finnish–English bilingualism as discursively affording an ambiguous kind of inclusion to students as Finnish-speaking/local and English-speaking/international students, and also social media communication as possibly contributing to the inclusion of all students as social media users. We argue that multimodal affordances of social media may act as an alternative discursive resource for inclusive intergroup relations among students in a student organization on an international campus.

Introduction

This paper explores how different language ideologies – sets of normative beliefs about language and its speakers – manifest in a Finnish student union’s communication practices in social media. In a number of non-English-speaking countries, English-medium instruction has been adopted as a common strategy to internationalize higher education (see Macaro et al. Citation2018). A similar development has also taken place within the context of our study – that of Nordic countries in general and Finland in particular. In this transformation, university student unions in Finland may be facing issues related to language ideologies because these ideologies might create inequalities among linguistically diverse students by mediating “between social structures and forms of talk” (Woolard and Schieffelin Citation1994, 55).

In recent years, Nordic countries have increasingly seen the greater presence of English in their scientific domains as a threat to Nordic languages (Davidsen-Nielsen Citation2008). The contrast between English and Nordic languages here implies an ideological tension between the preservation of ethnolinguistic nationalism and the pursuit of internationalization through the use of English. Saarinen and Taalas (Citation2017) identified this tension in language policies in Nordic higher education at the national and institutional levels. Given the social function of language ideologies, today’s Nordic universities most likely need to juggle different language ideologies to strive for equality among students with different linguistic backgrounds (see Shirahata and Lahti Citation2023 for the case of a Finnish university). In this paper, we explore how this tension might manifest itself in the communication activities of university-embedded student unions.

The rapid development of communication technology – the global expansion of the Internet in the 1990s and social media in the 2000s – has been changing the landscape of communication practices (see Herring and Androutsopoulos Citation2015). Zhou, Su, and Liu (Citation2021) argue for the importance of investigating how people combine various traditional and new modes of communication (e.g. face-to-face conversations, phone calls, text messages) to maintain relationships with their partners, families, friends, colleagues, and/or acquaintances. It is thus worthwhile to pay attention to these changes in communication practices when examining language ideologies in higher education today, where many individual students and student organizations extensively rely on social media in their day-to-day communication.

We explore, as a case, language ideologies and accompanying intergroup relations among students in social media communication practices of the Student Union of the University of Jyväskylä, Finland (Jyväskylän yliopiston ylioppilaskunta, JYY). The University of Jyväskylä (Jyväskylän yliopisto, JYU) had approximately 14,051 degree students in 2021, out of whom 561 (4%) were categorized as “international students”.Footnote1 In addition, there are typically between 300 and 500 incoming exchange students yearly. Up front, JYU seems to create a paradoxical vision of their language policy (Jyväskylän Yliopisto Citation2015b, 1): “Jyväskylän yliopisto on perinteiltään vahvasti suomenkielinen, mutta monikielinen ja kulttuurinen akateeminen yhteisö” [The University of Jyväskylä has a strong Finnish-speaking tradition, but is a multilingual and multicultural academic community; authors’ own translation]. This ambiguity, including its practical implications, is not explicitly addressed in university documents. Meanwhile, the student union JYY openly pronounce the challenges of the parallel use of Finnish and English in their equality plan:

The Universities Act defines Finnish as JYY’s official language (The Universities Act 558/2009, 46 §). As the resources allow, JYY aims to use English as often as possible in communication. However, JYY communication is not entirely bilingual. This puts international students in a weaker position in relation to Finnish speaking students. However, the student union aims to actively reduce these differences by paying attention to non-Finnish speakers in its communication. (Student Union of University of Jyväskylä Citation2019, 8)

Language ideologies as practical and lived

Our study is informed by the understanding of language ideologies as sets of meanings according to language and its presumed speakers, where groups of language speakers come to be associated with specific qualities, rights, and obligations (e.g. Irvine Citation1989). Language ideologies often function as “a mediating link between social structures and forms of talk” (Woolard and Schieffelin Citation1994, 55). People consciously or subconsciously make references to these ideologies when bringing up different group memberships (e.g. nationality or ethnicity) in interactions with others. At the broader societal level, language ideologies have long been considered crucial for the construction of national or ethnic identities (see Kroskrity Citation2010). Piller (Citation2011) claims that language proficiency and language choice are likely to be one of the major sources of inequality in so-called intercultural communication. She argues that underpinning natural language use is “a system of choices to which speakers enjoy differential levels of access” (144).

In higher education today, the expansion of English-medium instruction in non-English-speaking countries has been propelling an ideological shift concerning English, from reserving English as the language of specific English-speaking countries to acknowledging English as a lingua franca. The construct of “native and non-native speakers” of English (see Holliday Citation2006) that privileges some groups of people over others has been problematized. Instead, seeing English as a lingua franca has been advocated to enhance equality on international campuses (e.g. Jenkins Citation2018). This situation of the English language leads to and is led by the paradigm shift in the field of applied linguistics from defining language as named languages to highlighting the fluidity of linguistic practices in interaction (e.g. Makoni and Pennycook Citation2007).

Rather than formal language ideologies, we are interested in lived ideologies (see Billig et al. Citation1988) represented in popular ideas about language produced and reproduced in different spheres of social interaction from media and policy, through organizational communication and social media to mundane everyday conversation. Language ideologies represented in individual persons’ language practices have been argued to be more consequential to language practices of a community than language planning or management (e.g. Lo Bianco Citation2008; Spolsky Citation2004). Such lived ideologies are morally and politically loaded as they construct a version of the social world aligned with a specific point of view while suppressing others (e.g. Gal Citation2006). Since they are shared and widely circulated, they come to be viewed as commonsensical and a mere representation of some objective and natural state of affairs (e.g. Kraft and Lønsmann Citation2018). However, it is also important to consider that persons and groups might draw on more than one lived ideology to justify and normalize their conduct depending on the needs of the unfolding situation (Kraft and Lønsmann Citation2018); in this way, we see lived ideologies as practical, and we acknowledge their fragmented and potentially contradictory character (see e.g. Wetherell, Stiven, and Potter Citation1987).

We further see that such practical lived ideologies can be talked into being explicitly through expressing ideas or sharing accounts about the social dimension of language; they can also be constructed implicitly through systematically enacting certain linguistic choices in interactions with others. To take this thinking to the context of our study, we have noticed that JYY rarely explicitly discuss issues of language in their Facebook posts. The union’s lived ideologies concerning the social dimension of language can be inferred from a systematic study of how JYY select specific linguistic and visual means to communicate about specific topics with their audience(s).

Multimodal affordances of social media

The context in which this paper is set is that of online communication, here specifically social media. Social media offers its users a variety of communicative affordances (see Gibson Citation[1986] 2015). In their clearest form, such affordances appear as pre-designed templates or functionalities that instill possibilities and constraints for communication. There is, in other words, an interdependence between the way social media is designed and the way it is used (Jovanovic and Van Leeuwen Citation2018). Social media communication is typically multimodal in nature. It may, for example, mix (moving) images with writing and a specific kind of layout, and include music or other types of sound. Together, these form modal ensembles of meaning (Kress Citation2010, 159). In his explanation about multimodal discourse analysis, Kress (Citation2012) emphasizes the importance of looking into all modes of communication, seeing language as “always a partial bearer of the meaning of a textual/semiotic whole” (38). Herring (Citation2018) proposes such an analytic approach specifically to discourse analysis of computer-mediated communication, which has become increasingly multimodal with the emergence of new features (e.g. emojis, stickers, GIFs, video clips). In our study of language ideologies, we cover multiple modes of communication that JYY utilize in their Facebook posts.

A specific kind of visual mode typical for social media is the emoji (絵文字: 絵 e “picture” + 文字 moji “letter, character”), a graphical symbol that depicts for example faces or objects. Emojis were originally created for a Japanese mobile communication platform in the late 1990s, and they are now available on various mobile and web platforms worldwide. As summarized by Danesi (Citation2016) and others (Bai et al. Citation2019; Tang and Hew Citation2019), emojis have orthographic and semantic structure and pragmatic functions: functioning as punctuation marks, referring to concepts, expressing emotions, playfulness, and intimacy, adding nuance and tone to text, etc. Emojis may seem to represent a kind of universal “language” of online media, where a standardized list is kept up by the Unicode ConsortiumFootnote2 (Danesi Citation2016; Moschini Citation2016). However, in reality, there is considerable variation both between how emojis appear across platforms as well as how they are interpreted by individual users (Miller et al. Citation2016). There also seem to be differences in the interpretation and use of emojis across different geographical and linguistic communities (Barbieri et al. Citation2016; Ge and Herring Citation2018). Nevertheless, we agree that emojis serve as a universal semiotic resource for computer-mediated communication to a considerable extent (Danesi Citation2016).

Social media interaction often mixes aspects of private and public communication (Jovanovic and Van Leeuwen Citation2018). This is also the case with Facebook, and here especially its “pages” that are meant for communities or organizations. Facebook pages represent the type of one-to-many social media where the receivers are not truly known to the sender of the message. Since pages such as the one of JYY are public, anyone using Facebook can follow them.

Methodology

Critical discursive psychology

We apply the framework of critical discursive psychology (CDP) that offers a communicative reading of traditional psychological concepts (such as social categories) by redefining them as discursive resources that can be drawn upon in text and talk to construct social order (Potter and Wetherell Citation1987; Wiggins Citation2017). Central to this approach is the idea that text and talk on any topic can be inconsistent and even dilemmatic (e.g. Wetherell Citation1996). CDP has typically been applied to examine topical talk in researcher-provoked data, such as in the analysis of interview and focus group data where the participants have been asked to discuss specific themes (e.g. Seymour-Smith, Wetherell, and Phoenix Citation2002). Applications of CDP to naturally occurring data, and especially under the theme of language ideologies, are rare (for exceptions, see Shirahata and Lahti Citation2023).

We see that the notion of lived practical ideologies in which we are interested is akin to CDP’s analytical concept of interpretative repertoires. We adapt the concept to our needs by both expanding and narrowing it down. Just as interpretative repertoires have been defined as commonsensical and recognizable storylines, descriptions or accounts employed to deal with a specific topic (e.g. Wetherell Citation1996), we expand this definition to also include patterned systematic ways of selecting specific linguistic and visual means to communicate about specific topics (for some examples of CDP being used to analyze visual images, see Burke Citation2018; Lennon and Kilby Citation2020). By the same token, we narrow the concept of interpretative repertoires down by departing from the notion of the commonsensical as typically defined in CDP (i.e. with relation to some broader sociocultural context, e.g. Wiggins Citation2017). Instead, we treat the commonsensical as local and locally accounted for: what appears to be commonsensical (reoccurring, patterned, accountable) within the scope of our data set. In this way, our application of CDP is purely inductive, and it acquires a strong ethnomethodological flavor. In line with CDP, our analysis remains poised on identifying potential ideological dilemmas or cracks and inconsistencies among different co-occurring language ideologies (e.g. Wetherell Citation1996).

Data set

Membership in JYY is compulsory for bachelor’s and master’s degree students of the University of Jyväskylä to register for attendance each academic year (it is optional for doctoral and exchange students). JYY use a number of communication channels: Facebook (7.1 K followers), Twitter (2,226 followers), Instagram (4,567 followers), LinkedIn, their own website, newsletters, and periodicals. We chose JYY’s Facebook posts as our data source for the following reasons: we are interested in language ideologies with respect to recent communication practices as well as more established ones; the number of the followers of JYY’s Facebook page is noticeably bigger than those of the union’s other social media sites; and JYY’s Facebook page is public and open to anyone, even those without a Facebook account.

Our data set consists of Facebook posts created by JYY from July 2021 (a month before the beginning of the academic year 2021/22) to June 2022 (a month after the end of most courses during the academic year). Within this time frame, JYY published 218 posts. In this study, given our interest in multimodality or the cooccurrence of linguistic and visual means in social media communication, we decided to focus on the posts that include both text and visual imagery (190 posts), which resulted in removing the posts with only text or visual imagery (28 posts altogether: 25 with only visual imagery and 3 with only text) from our data. While we acknowledge that all text is multimodal with typographic elements such as layout, typeface, or font size, these elements are out of the scope of this study. We also excluded reactions and comments to the posts from the analysis. Hyperlinks were followed when available to better understand the content and meaning of the posts. In our initial analysis, we classified the posts into five genres: event/election/survey/meeting announcements and reports (116 posts), open position advertisements (31), administrative/practical information provisions (23), greetings/appeals (18), and sustainability campaigns (2).

Data analysis

In our analysis, language ideologies were regarded as interpretative repertoires identifiable through recognizing patterned ways of selecting specific linguistic and visual means to communicate about specific topics. We saw different language ideologies as different interpretative repertoires about language and its speakers. When it comes to CDP’s analytical concept of subject positions, we approached it as constructions of student groups together with their characteristics, rights and obligations as language speakers. We acknowledged that subject positions can be produced explicitly through direct references to groups, but also implicitly through mentions of qualities, activities, or responsibilities commonsensically associated with some groups. We also considered how communication practices such as selecting a specific language in creating a post on a specific topic construct subject positions through implying a specific student group with a specific language proficiency as the audience of the post. Last but not least, we addressed possible discrepancies or conflicts among the identified language ideologies as ideological dilemmas. Keeping in mind that CDP uniquely combines theory-guided and data-driven analysis, we attempted to illuminate the aspect of local communication practices as manifestations of language ideologies or large-scale societal beliefs.

The first author was primarily responsible for the analysis, and the second and third authors assisted her by discussing the analytic choices with her. The first author went through the selected JYY’s Facebook posts to inductively identify patterns in JYY’s communication practices (e.g. which languages are used and how visible they are, whether emojis are used or not, what types of visual images are accompanied by text, whether hyperlinks are available or not). She then examined patterns in the matters featured in the posts in terms of the social and political context and language use, in order to address JYY’s contextualized language use. In this way, she elucidated language ideologies that may be underpinning JYY’s language use on the Facebook platform. She also explored JYY’s use of emojis, visual images, and hyperlinks along with languages so as to identify language ideologies that are associated with recent communication practices in social media. In the process of identifying language ideologies along with JYY’s communication practices, the first author also tried to determine what student groups are implied as the audiences of JYY’s Facebook posts. Through the construction of these student groups within the JYY community, at the same time, certain types of intergroup relations among students are established. In some cases, students may be categorized as belonging to one big group, leading to inclusion; in other cases, students may be divided into in- and out-groups resulting in mutual exclusion. Finally, the first author examined the interrelationships among the language ideologies for possible discrepancies or ideological dilemmas.

Findings

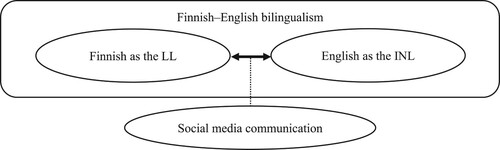

visualizes the language ideologies in JYY’s Facebook posts that we have identified. Overall, we see the notions of Finnish as the local language and English as the international language as together forming Finnish–English bilingualism. This bilingualism discursively affords both inclusive and mutually exclusive intergroup relations to students in the community: the inclusion of all students who speak either Finnish or English and the mutual exclusion of Finnish-speaking/local students and English-speaking/international students in the community. The inclusive relation is based on the view of Finnish and English as means of communication, whereas the mutually exclusive relation is based on the view of Finnish and English as conduits for localness and internationality respectively. The construction of a clear distinction between Finnish-speaking students as “local” and English-speaking students as “international” creates a dilemma between the notions of Finnish as the local language and English as the international language within JYY’s Finnish–English bilingualism. Meanwhile, social media communication as a shared means of communication is identified as possibly challenging the division of students constructed through the use of Finnish and English, allowing JYY to mitigate the ideological dilemma for the inclusion of all students as social media users. In the following, we will examine several empirical examples to illustrate how the identified language ideologies are locally deployed in JYY’s Facebook posts. We will first focus on languages, and will then move onto emojis, visual images (illustrations, photos, and videos), and hyperlinks.

Figure 1. Language ideologies in JYY’s Facebook posts. Note: solid figures – language ideologies, double arrow – ideological dilemma, LL – local language, INL – international language.

JYY’s Finnish–English bilingual language use prioritizing Finnish over English: integrating English-speaking students into the primarily Finnish-speaking JYY community

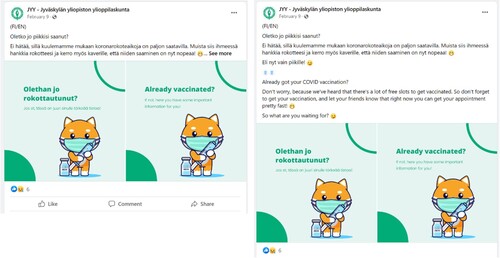

maps out the patterns of JYY’s language use in text and accompanying visual images of their Facebook posts. In almost all the cases (186/190 posts) both Finnish and English are used in text, and in most cases (146/190) Finnish and English are used in parallel. For example, the post in notifies the JYY community of the easier access to COVID-19 vaccination service in the local region. It provides the same information in the Finnish and English texts although there are some form-level differences (e.g. a positive or negative form, a suggestion or question form) between the two language versions. This typical pattern of JYY’s language use in Facebook presents Finnish and English as the working languages of JYY. The members of JYY are thus assumed to speak either Finnish or English. However, the two languages have different status – Finnish acts as the primary working language, and English as the additional one. This hierarchical relation between the two named languages is easily noticeable from the fact that Finnish text is always displayed ahead of English text. This order is usually signaled by the symbol (FI/EN) at the beginning of the main text, as in .

Table 1. JYY’s language use in their Facebook posts.

The higher status of Finnish over English is also evident from the imbalanced presence of the two languages in the main text and the accompanying visual image(s) in JYY’s posts as a whole (see ). As well as many posts in which Finnish and English are used simultaneously in text, there are posts in which the Finnish text is longer and contains more detail than the English text (11/190), or full information is given in Finnish but only a short summarizing note is provided in English (29/190). There are no reverse cases. Furthermore, while there are some posts in which only Finnish is used in text (4/190), there is not a single post in which only English is used. As to accompanying visual images, only Finnish is used in image captions in many posts (83/190) although there are also many posts in which Finnish and English are simultaneously used in image captions (50/190). In some posts (23/190), the Finnish caption is longer and contains more detail than the English caption, but not vice versa. There is only one post in which only English is used in the image caption (the post announces a Christmas fair by a local civic organization committed to international development cooperation).

In light of the hierarchical relation between Finnish and English across JYY’s Facebook posts, it can be inferred that Finnish speakers are the primary audience although English speakers are also considered part of the audience. In other words, Finnish-speaking students are placed in the center of the JYY community, and English-speaking students in the periphery. JYY nevertheless use Finnish and English in parallel in most of their posts. Therefore, JYY’s Finnish–English bilingual language use in their posts can be taken as an attempt to integrate English-speaking students with limited proficiency in Finnish into the primarily Finnish-speaking community.

JYY’s Finnish–English bilingualism with a dilemma between Finnish as the local language and English as the international language: inclusion of all as Finnish- or English-speaking students or mutual exclusion of local and international students in the JYY community

We will now move on to examine the patterns of the matters that JYY feature in their Facebook posts in terms of the social and political context and language use. In doing so, we will address language ideologies that may be embedded in JYY’s Finnish–English bilingual language use prioritizing Finnish over English. The social and political context and language use in the featured matters are notified explicitly or implicitly within the posts and/or by the linked information.

As summarized in , JYY’s posts feature not only JYY’s own matters but also the university’s (JYU’s), regional, national, EU, and global matters. This broader range of the contexts locates JYY in a specific university, region, country, and continent. As to the language use, the posts that are about local matters – JYY’s, the university’s, regional, or national ones (125/190 posts, see the columns FI > EN and FI in ) – are mostly in Finnish instead of English, which is to be expected. The use of English is expected in only a small number of the matters (8/190, see the columns EN > FI and EN in ), all of which but one (a global matter) are the university’s or regional matters that have something to do with internationality: the recruitment of JYU’s tutors for new international students (5 posts), the recruitment of JYU’s student ambassadors who are expected to collaborate with international students (1), and the announcement of a Christmas fair by a local civic organization committed to international development cooperation (1). This greater presence of Finnish over English in the matters featured in JYY’s posts indicates that the use of Finnish as the local language is the norm, and the use of English as the international language is occasional. Here, the notions of Finnish as the local language and English as the international languages are visible, forming Finnish–English bilingualism. This bilingualism can thus be identified as underpinning JYY’s Finnish–English bilingual language use in their Facebook posts.

Table 2. The matters featured in JYY’s Facebook posts.

In the previous section, we pointed to the possibility that JYY may be attempting to integrate English-speaking students into the primarily Finnish-speaking community through the employment of English in addition to Finnish as their working languages on the Facebook platform. In this line of analysis, JYY’s Finnish–English bilingualism can be regarded as discursively warranting their attempt of integration in the linguistically diverse community. However, a comparison of two specific posts ( and ) challenges this interpretation. The post in announces that JYU is recruiting tutors for new international students. The post itself does not provide any information on the language requirements to be an international tutor, but such information is available through the link to JYU’s webpage about the position written in English. On this webpage, “good command of English” is listed as the primary language requirement, and “working knowledge of Finnish” as “an asset” (Jyväskylän Yliopisto Citation2015a). Apparently, international students are conceived as speakers of English rather than Finnish, and English is construed as the international language, as contrasted with Finnish as the local language. Meanwhile, the post in announces that JYU is recruiting tutors for new students in Finnish study programs. It is clarified here that tutoring students in those programs “does not concern international students”, implying that students who speak Finnish are usually conceived as local students. All in all, the members of JYY are classified as either local students who are assumed to speak Finnish, or international students who are assumed to speak English. This classification creates a dilemma between the notions of Finnish as the local language and English as the international language within JYY’s Finnish–English bilingualism. It is not logically possible to see students who speak both Finnish and English as both local and international students, to see students who speak Finnish as international students, or to see students who do not speak Finnish as local students.

When Finnish and English are regarded as mere means of communication, JYY’s Finnish–English bilingual language use in their Facebook posts appears to be enabling JYY to integrate English-speaking students into the primarily Finnish-speaking community. However, once Finnish and English are regarded as conduits for localness and internationality respectively, the dilemma arises between the notions of Finnish as the local language and English as the international language. This results in the construction of a clear distinction between Finnish-speaking students (possibly also proficient in English) as local students and English-speaking students (some of them possibly proficient in Finnish) as international students. Hence, on the one hand, JYY’s Finnish–English bilingualism might act as a discursive resource for the inclusion of all students who speak either Finnish or English, but, on the other hand, it might act as a resource for the mutual exclusion of Finnish-speaking/local students and English-speaking/international students in the community.

JYY’s social media communication in their Facebook posts: inclusion of all recipients as social media users

The multimodal nature of social media communication in JYY’s Facebook posts may be seen as mitigating the ideological dilemma constructed through their language use. Across their posts, JYY utilize emojis, visual images, and hyperlinks, along with languages. In this section, we will examine the basic properties and functions of emojis, visual images, and hyperlinks in the data. In addition to the posts examined above () we include one more post () to illustrate our argument. The post in gives instructions for getting the cloth patch for the student overallsFootnote3 in connection with JYY board elections.

The double use of one type of emoji ( ) in the post in and (

) in the post in and ( ) in the posts in and and the triple use of one type of emoji (

) in the posts in and and the triple use of one type of emoji ( ) in the post in mark off a boundary between the Finnish and English texts within the post. The visual images in the posts in and can be recognized as illustrations, the image in the post in as a photo, and the image in as a video. The use of similar green-colored backgrounds for the illustrations in the posts in and and the video in the post in achieves some degree of cohesion across the JYY’s posts in terms of visual design. Likewise, the Finnish and English texts sharing a photo or a video in the posts in and respectively can be interpreted as creating some cohesion within each post. Lastly, the blue underlined URLs in should be recognized as hyperlinks for further information. When examining the posts, we had little difficulty in recognizing emojis, visual images, and hyperlinks as such and understanding the basic properties and functions of these symbols. We assume that JYY members should also be able to do so as long as they are familiar with social media communication.

) in the post in mark off a boundary between the Finnish and English texts within the post. The visual images in the posts in and can be recognized as illustrations, the image in the post in as a photo, and the image in as a video. The use of similar green-colored backgrounds for the illustrations in the posts in and and the video in the post in achieves some degree of cohesion across the JYY’s posts in terms of visual design. Likewise, the Finnish and English texts sharing a photo or a video in the posts in and respectively can be interpreted as creating some cohesion within each post. Lastly, the blue underlined URLs in should be recognized as hyperlinks for further information. When examining the posts, we had little difficulty in recognizing emojis, visual images, and hyperlinks as such and understanding the basic properties and functions of these symbols. We assume that JYY members should also be able to do so as long as they are familiar with social media communication.

Apparently, emojis, visual images, and hyperlinks are different from languages in property and function and have little to do with the notions of Finnish as the local language and English as the international language. This point is highlighted in the posts in which Finnish and English are used in parallel. In the post in , for example, the same emojis ( and

and  ) are used in both Finnish and English texts, and the same illustration is displayed as the accompanying visual images, apparently creating a certain degree of cohesion between the two language versions of the post. Language – Finnish or English – is the only difference between the two versions. Hence, both Finnish-speaking/local and English-speaking/international students in the JYY community can be grouped together as social media users. Social media communication as a shared means of communication may be allowing JYY to mitigate the dilemma between the notions of Finnish as the local language and English as the international language, with respect to intergroup relations among students (as addressed above), for the inclusion of all in the community.

) are used in both Finnish and English texts, and the same illustration is displayed as the accompanying visual images, apparently creating a certain degree of cohesion between the two language versions of the post. Language – Finnish or English – is the only difference between the two versions. Hence, both Finnish-speaking/local and English-speaking/international students in the JYY community can be grouped together as social media users. Social media communication as a shared means of communication may be allowing JYY to mitigate the dilemma between the notions of Finnish as the local language and English as the international language, with respect to intergroup relations among students (as addressed above), for the inclusion of all in the community.

Discussion

Our analysis identifies patterns of the communication practices in JYY’s Facebook posts and language ideologies and intergroup relations they entail. In our data set, languages, emojis, visual images, and hyperlinks are utilized as central means of communication. JYY use Finnish and English as the primary and additional working languages to convey the main message. Emojis, visual images, and hyperlinks appear to be creating a certain degree of cohesion between texts in the two named languages. JYY’s language use can be seen as constructing Finnish–English bilingualism with a dilemma between the notions of Finnish as the local language and English as the international language. These different language ideologies together can be seen as shaping the image of the student union into an international Finnish university’s student community. With respect to intergroup relations among students, JYY’s local bilingualism proposes both inclusion of all students who speak either Finnish or English and mutual exclusion of Finnish-speaking/local students and English-speaking/international students. Since a clear distinction between Finnish-speaking students as “local” and English-speaking students as “international” appears to have been established, the mutual exclusion among students is inevitable. Due to this condition, JYY’s bilingualism takes an ambiguous character as a resource for inclusion. Meanwhile, the way multimodal affordances are used suggests an attempt to include all students who use social media. Here, social media communication as a shared means of communication seems to offer a possible solution to the ideological dilemma by emphasizing shared symbolic understanding, rather than relying on named languages only.

Prior research has found that native-speakerism of English (Holliday Citation2006) is often relevant to discussions about students’ language use (e.g. Mortensen and Fabricius Citation2014) as well as institutional language policies (e.g. Jenkins Citation2014) in internationalizing and “Englishizing” higher education. This language ideology reserves authenticity or legitimacy of the use of English to people who are recognized as “native speakers” of English (Lowe and Pinner Citation2016), by combining the notions of national or ethnic language and standard language (Doerr Citation2009). We hardly see a trace of this ideology in JYY’s language use. English is simply construed as an international language or a lingua franca. However, as with other kinds of inclusive views of English, JYY’s view of English is unlikely to defy the global spread of English or normative standard English, which is “social in character, being connected with capital and power and with the construction of particular kinds of human subjectivities” (O’Regan Citation2021, 6). Undoubtedly, the use of English as a lingua franca in higher education in non-English-speaking countries has been opening up new opportunities for students with different linguistic backgrounds to socialize and study together. Meanwhile, the political and economic power of English has been solidified. There is a need for further reflection and discussion on how the use of English for internationalization of higher education perpetuates the hegemony of English.

Of particular interest is that the dilemma within JYY’s Finnish–English bilingualism creates a kind of dichotomy, and therefore does not allow students who speak both Finnish and English to be seen as both local and international students. Although an individual’s language use should not be confined to named languages (Li Citation2011; Makoni and Pennycook Citation2007), the working languages of a student organization under the official umbrella of a university most likely act as conduits for localness or internationality to result in the discursive construction of the mutually exclusive intergroup relations between local and international students. Indeed, today’s universities are still constructing themselves as national institutions involved in the process of internationalization of higher education through English (see Saarinen and Taalas Citation2017). In the JYY community, students with the international status who are proficient in Finnish and students with the local status who are proficient in English but not in Finnish are located between groups of international and local students. This situation can be interpreted in both negative and positive ways – those students are either marginalized or they can have the benefit of intergroup mobility.

Social media is characterized by “the cooccurrence or convergence of different modes of communication on a single platform” (Herring and Androutsopoulos Citation2015, 130). Accordingly, JYY’s Facebook communication practices include emojis, visual images, and hyperlinks as well as more traditional language use, highlighting the multimodal nature of communication that has always been present in human communication as in gestures, gaze, facial expressions, etc. (see Jewitt, Bezemer, and O’Halloran Citation2016). In JYY’s Facebook posts, emojis are used across Finnish and English texts. Emojis are at times referred to as a universal language of online media that transcends the boundaries of named languages (Danesi Citation2016; Moschini Citation2016). However, we found it challenging to examine the semantic structure and pragmatic functions of emojis in an ethnomethodological approach, and we were only able to identify some orthographic functions. The same applies to hyperlinks; the basic function (i.e. digital referencing for further information) is obvious, but more sophisticated semantics and pragmatics are not. Further research is needed to explore the concept of emojis as a universal “language” although they can stand alone as a unique universal semiotic resource for computer-mediated communication (see Danesi Citation2016).

Visual images, more than anything else, challenged us to value the ethnomethodological aspects of CDP (see Potter and Wetherell Citation1987). In the early stage of analysis, we attempted to make interpretations about people featured in photos, only to realize how much we rely on our knowledge and experiences to make inferences about people on the basis of their appearances. This is because JYY’s Facebook posts contained no explanation or interaction concerning the accompanying photos to support our interpretation. Also, since JYY is only a university’s student organization, it did not seem reasonable for us to back up our interpretation by drawing on common-sense beliefs widely circulated in society, as in some media discourse studies that applied CDP to examine visual images in news media (e.g. Burke Citation2018; Lennon and Kilby Citation2020). A similar difficulty has been noted by Bezemer and Kress (Citation2017), who acknowledge the difficulty of making sense of a video in a teenager’s private Facebook post without reading the text in the post; however, the researchers elicited cohesion being produced across different modes of text making. In line with Bezemer and Kress’s (Citation2017) finding, the current study suggests that, despite the potential centrality of language on the Facebook platform, multimodal affordances of social media may act as a discursive resource for inclusive intergroup relations among students in a student organization on an international campus, providing an online space for intercultural communication where students with different linguistic backgrounds become aware of and learn about one another (Jones and Hafner Citation2021).

In the introduction, we took a look at JYY’s equality plan to learn their official expression of difficulty in practicing the ideal or complete parallel use of Finnish and English in their everyday activities and the resulting possible exclusion of non-Finnish-speaking students/international students through the use of Finnish only. These concerns are reflected in JYY’s Finnish–English bilingualism that affords students both inclusive and exclusive intergroup relations, together with the potential marginalization of or intergroup mobility for students who do not fit in the categories of Finnish-speaking/local students and English-speaking/international students. The university law in Finland recognizes only Finnish and Swedish as the official languages; international students make up only 4% of the student body. Against this social and political backdrop, the construction of a rather perplexing social reality might be seen as a sign of JYY’s commitment and efforts to achieving a higher level of inclusion in the student community. It is certainly a challenge to find a balanced approach to language practices on the campus. Going forward, we need more research across a range of societal and linguistic contexts to gain a better understanding of the variety of potential approaches to language ideologies and practices in the ever-more international field of higher education.

Since we expanded the scope of language ideology in this paper by including not only linguistic but also visual means of communication, we were able to elucidate the inclusion of all in the JYY community that is made possible by multimodal affordances, as an alternative to the ambiguous kind of inclusion. When university student unions face language barriers, it would be important to explore different modes of communication, the configurations of traditional and new media (Zhou, Su, and Liu Citation2021), especially newly available communicative affordances (see Herring Citation2018), understanding that language accounts only partially for the meaning of text or speech (Kress Citation2012). This also applies to research. Jovanovic and Van Leeuwen (Citation2018) conclude their study on social media dialogue: “as discourse analysts, we should, at all times, search for both, for constraints as well as for signs of freedom” (697). This is something we strived for in our study as well. We hope that in future studies, scholars will continue exploring the many ways in which multimodal affordances may challenge existing understandings of language practices and ideologies in the context of social media use.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to the anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback on an earlier version of the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mai Shirahata

Mai Shirahata is a Doctoral Researcher at the Department of Language and Communication Studies, University of Jyväskylä, Finland. Her doctoral research project explores language ideologies in internationalizing higher education concerning intergroup relations and interpersonal relationships among students. She is interested in ethnomethodological approaches to intercultural communication.

Malgorzata Lahti

Malgorzata Lahti, PhD, is a Senior Lecturer at the Department of Language and Communication Studies, University of Jyväskylä, Finland. Her research interests include critical intercultural communication pedagogy as well as interculturality and multilingualism in interactions in professional and academic contexts. In her ongoing research projects, she is exploring knowledge construction in interactions of a cleaning team. She is also applying the perspective of interculturality to the study of interprofessional teamwork in health care.

Marko Siitonen

Marko Siitonen, PhD, works as a Professor at the Department of Language and Communication Studies, University of Jyväskylä, Finland. He heads the international MA programme on Language, Globalization, and Intercultural Communication. His research has focused on social interaction in online communities across contexts. In addition, his research interests span the topical areas of intercultural communication and technology-mediated communication at work.

Notes

3 Student overalls are part of the university student tradition in Finland. Students often collect overall patches by participating in different student events.

References

- Bai, Q., Q. Dan, Z. Mu, and M. Yang. 2019. “A Systematic Review of Emoji: Current Research and Future Perspectives.” Frontiers in Psychology 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02221.

- Barbieri, F., G. Kruszewski, F. Ronzano, and H. Saggion. 2016. “How Cosmopolitan Are Emojis? Exploring Emojis Usage and Meaning Over Different Languages with Distributional Semantics.” In Proceedings of the 24th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, 531–535. New York: Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/2964284.2967278

- Bezemer, J., and G. Kress. 2017. “Young People, Facebook and Pedagogy: Recognizing Contemporary Forms of Multimodal Text Making.” In Global Youth in Digital Trajectories, edited by M. Kontopodis, C. Varvantakis, and C. Wulf, 22–38. London: Routledge.

- Billig, M., S. Condor, D. Edwards, M. Gane, D. Middleton, and A. Radley. 1988. Ideological Dilemmas: A Social Psychology of Everyday Thinking. London: Sage Publications.

- Burke, S. 2018. “The Discursive “Othering” of Jews and Muslims in the Britain First Solidarity Patrol.” Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology 28 (5): 365–377. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2373

- Danesi, M. 2016. The Semiotics of Emoji: The Rise of Visual Language in the Age of the Internet. London: Bloomsbury.

- Davidsen-Nielsen, N. 2008. “Parallelsproglighed—Begrebets Oprindelse.” Accessed June 4, 2020. https://cip.ku.dk/om/om_parallelsproglighed/oversigtsartikler_om_parallelsproglighed/parallelsproglighed_begrebets_oprindelse/.

- Doerr, N. M. 2009. The Native Speaker Concept: Ethnographic Investigations of Native Speaker Effects. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

- Gal, S. 2006. “Migration, Minorities and Multilingualism: Language Ideologies in Europe.” In Language Ideologies, Policies and Practices: Language and the Future of Europe, edited by C. Mar-Molinero and P. Stevenson, 13–27. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ge, J., and S. C. Herring. 2018. “Communicative Functions of Emoji Sequences on Sina Weibo.” First Monday 23: 11. https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v23i11.9413.

- Gibson, J. (1986) 2015. The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception: Classic Edition. New York: Psychology Press.

- Herring, S. C. 2018. “The Coevolution of Computer-Mediated Communication and Computer-Mediated Discourse Analysis.” In Analyzing Digital Discourse: New Insights and Future Directions, edited by P. Bou-Franch, and P. G. Blitvich, 25–67. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Herring, S. C., and J. Androutsopoulos. 2015. “Computer-Mediated Discourse 2.0.” In The Handbook of Discourse Analysis, 2nd ed., edited by D. Tannen, H. E. Hamilton, and D. Schiffrin, 127–151. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

- Holliday, A. 2006. “Native-Speakerism.” ELT Journal 60 (4): 385–387. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccl030

- Irvine, J. T. 1989. “When Talk Isn’t Cheap: Language and Political Economy.” American Ethnologist 16 (2): 248–267. https://doi.org/10.1525/ae.1989.16.2.02a00040

- Jenkins, J. 2014. English as a Lingua Franca in the International University: The Politics of Academic English Language Policy. London: Routledge.

- Jenkins, J. 2018. “English Medium Instruction in Higher Education: The Role of ELF.” In Second Handbook of English Language Teaching, edited by X. Gao, 91–108. Cham: Springer.

- Jewitt, C., J. Bezemer, and K. O’Halloran. 2016. Introducing Multimodality. London: Routledge.

- Jones, R. H., and C. A. Hafner. 2021. Understanding Digital Literacies: A Practical Introduction. 2nd ed. London: Routledge.

- Jovanovic, D., and T. Van Leeuwen. 2018. “Multimodal Dialogue on Social Media.” Social Semiotics 28 (5): 683–699. https://doi.org/10.1080/10350330.2018.1504732

- Jyväskylän Yliopisto. 2015a. Internationalisation at Home. Accessed October 24, 2022. https://www.jyu.fi/en/study/internationalisation-and-student-exchange/internationalisation-at-home#autotoc-item-autotoc-4.

- Jyväskylän Yliopisto. 2015b. Jyväskylän Yliopiston Kielipolitiikka. Accessed October 24, 2022. https://www.jyu.fi/fi/yliopisto/organisaatio-ja-johtaminen/johtosaanto-ja-periaatteet/dokumentit/kielipolitiikka.

- Kraft, K., and D. Lønsmann. 2018. “A Language Ideological Landscape: The Complex Map in International Companies in Denmark.” In English in Business and Commerce: Interactions and Policies, edited by T. Sherman and J. Nekvapil, 46–72. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.

- Kress, G. 2010. Multimodality: A Social Semiotic Approach to Contemporary Communication. London: Routledge.

- Kress, G. 2012. “Multimodal Discourse Analysis.” In The Routledge Handbook of Discourse Analysis, edited by J. P. Gee and M. Handford, 35–50. London: Routledge.

- Kroskrity, P. V. 2010. “Language Ideologies – Evolving Perspectives.” In Society and Language Use, edited by J. Jaspers, J. O. Östman, and J. Verschueren, 192–211. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Lennon, H. W., and L. Kilby. 2020. “A Multimodal Discourse Analysis of ‘Brexit’: Flagging the Nation in Political Cartoons.” In Political Communication: Discursive Perspectives, edited by M. A. Demasi, S. Burke, and C. Tileagă, 115–146. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Li, W. 2011. “Moment Analysis and Translanguaging Space: Discursive Construction of Identities by Multilingual Chinese Youth in Britain.” Journal of Pragmatics 43 (5): 1222–1235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2010.07.035

- Lo Bianco, J. 2008. “Tense Times and Language Planning.” Current Issues in Language Planning 9 (2): 155–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/14664200802139430

- Lowe, R. J., and R. Pinner. 2016. “Finding the Connections Between Native-Speakerism and Authenticity.” Applied Linguistics Review 7 (1): 27–52. https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2016-0002

- Macaro, E., S. Curle, J. Pun, J. An, and J. Dearden. 2018. “A Systematic Review of English Medium Instruction in Higher Education.” Language Teaching 51 (1): 36–76. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444817000350

- Makoni, S., and A. Pennycook. 2007. “Disinventing and Reconstituting Languages.” In Disinventing and Reconstituting Languages, edited by S. Makoni and A. Pennycook, 1–41. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- Miller, H., J. Thebault-Spieker, S. Chang, I. Johnson, L. Terveen, and B. Hecht. 2016. “‘Blissfully Happy’ or ‘Ready to Fight’: Varying Interpretations of Emoji.” In Proceedings of the 10th International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media ICWSM-16, 10(1), 259–268. https://doi.org/10.1609/icwsm.v10i1.14757.

- Mortensen, J., and A. Fabricius. 2014. “Language Ideologies in Danish Higher Education: Exploring Student Perspectives.” In English in Nordic Universities: Ideologies and Practices, edited by A. K. Hultgren, F. Gregersen, and J. Thøgersen, 193–223. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Moschini, I. 2016. “The ‘Face with Tears of Joy’ Emoji: A Socio-Semiotic and Multimodal Insight Into a Japan-America Mash-Up.” Hermes–Journal of Language and Communication in Business 55: 11–25.

- O’Regan, J. P. 2021. Global English and Political Economy. London: Routledge.

- Piller, I. 2011. Intercultural Communication: A Critical Introduction. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Potter, J., and M. Wetherell. 1987. Discourse and Social Psychology: Beyond Attitudes and Behaviour. London: Sage Publications.

- Saarinen, T., and P. Taalas. 2017. “Nordic Language Policies for Higher Education and Their Multi-Layered Motivations.” Higher Education 73 (4): 597–612. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-015-9981-8

- Seymour-Smith, S., M. Wetherell, and A. Phoenix. 2002. “‘My Wife Ordered Me to Come!’: A Discursive Analysis of Doctors’ and Nurses’ Accounts of Men’s Use of General Practitioners.” Journal of Health Psychology 7 (3): 253–267. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105302007003220

- Shirahata, M., and M. Lahti. 2023. “Language Ideological Landscapes for Students in University Language Policies: Inclusion, Exclusion, or Hierarchy.” Current Issues in Language Planning 24 (3): 272–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/14664208.2022.2088165

- Spolsky, B. 2004. Language Policy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Student Union of University of Jyväskylä. 2019. The Student Union of the University of Jyväskylä Equality Plan 2019–2023. Accessed October 24, 2022. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1uBKsZmwuxPXrTLCgfplvEOaH-t4G2dx5/view.

- Tang, Y., and K. F. Hew. 2019. “Emoticon, Emoji, and Sticker Use in Computer-Mediated Communication: A Review of Theories and Research Findings.” International Journal of Communication 13: 2457–2483.

- Wetherell, M. 1996. “Fear of Fat: Interpretative Repertoires and Ideological Dilemmas.” In Using English: From Conversation to Canon, edited by J. Maybin and N. Mercer, 36–41. London: Routledge.

- Wetherell, M., H. Stiven, and J. Potter. 1987. “Unequal Egalitarianism: A Preliminary Study of Discourses Concerning Gender and Employment Opportunities.” British Journal of Social Psychology 26 (1): 59–71. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8309.1987.tb00761.x

- Wiggins, S. 2017. Discursive Psychology: Theory, Method and Applications. London: Sage Publications.

- Woolard, K. A., and B. B. Schieffelin. 1994. “Language Ideology.” Annual Review of Anthropology 23 (1): 55–82. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.an.23.100194.000415

- Zhou, B., C. C. Su, and J. Liu. 2021. “Multimodal Connectedness and Communication Patterns: A Comparative Study Across Europe, the United States, and China.” New Media & Society 23 (7): 1773–1797. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448211015986