ABSTRACT

The article explores key trajectories of Swedish press discourse on immigration in the period 2010–2022 which covers a variety of socio-economic and political developments including parliamentary entry and growth of the immigration-critical Swedish far-right. Analysing the press across its key variants (liberal/conservative, nationwide/regional, broadsheet/tabloid), the article points to how dynamics of the press discourse on immigration locates within the key “discursive shifts” in the wider Swedish public sphere, including those related to regular political events such as national-parliamentary elections (of 2010, 2014, 2018, and 2022) as well as those marked by other, pivotal contextual factors such as the 2015–2016 European “Refugee Crisis.” Deploying a systematic, multi-method approach from within critical discourse studies, the article leads to a number of findings, including on the gradual change and the apparent negativisation of the analysed press discourse over time. It highlights that the increasing hybridity and ambivalence of discursive constructions of immigration in the press are among the key factors underlying their alignment with the wider logic of the public sphere in Sweden, and especially with developments in Swedish political discourse in recent years.

1. Introduction

The analysis presented in this article aims at exploring the trajectories of Swedish press discourse on immigration in the period 2010-2022. Exploring key stages of development of Swedish press’ framing of immigration and multiculturalism in that period, the article points to the key “discursive shifts” (Krzyżanowski Citation2018b, Citation2020a) in the Swedish public sphere in order to trace moments/periods and dynamics of change in portraying and representing immigration. We approach our period of investigation – i.e. 2010–2022 – as the one marking a highly critical, temporal frame for Sweden. On the one hand, it is a period when, politically speaking, the significant impact of the explicitly anti-immigration Swedish far-right would reinforce a wider tendency towards normalisation of the “politics of exclusion” (Krzyżanowski and Wodak Citation2009) as a comprehensive set of views present in the wider public and especially political imagination (Demker Citation2015; Ekström, Krzyżanowski, and Johnson Citation2023; Krzyżanowski Citation2018a).

But on the other hand, 2010–2022 is also the key period of Sweden witnessing a deep, socio-economic change strongly conditioned by the ever-more obvious, neoliberal intervention into, and effectively marketisation of, Swedish welfare state and of related public services (Blomqvist and Palme Citation2020). These, in turn, would significantly contribute to the ever more obvious dismantling of the often over-idealised and “exceptionalised” (Schierup and Ålund Citation2011) Swedish welfare state system as well as underpin the gradual ending to Swedish humanitarian “politics of solidarity” (Scarpa and Schierup Citation2018). These developments would often result in stereotypical building of connections in the public discourse between many of Sweden’s vital social problems and immigration (see Ekman Citation2022; Ekström, Krzyżanowski, and Johnson Citation2023; Sarnecki Citation2021).

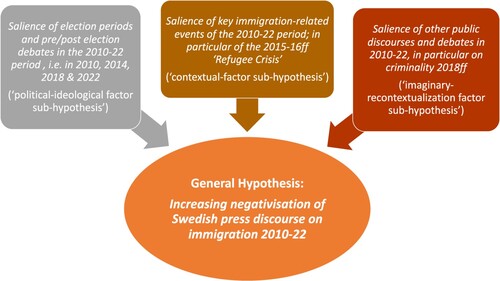

Attempting to bring together the above political and various other factors of key influence to the recent dynamics of the Swedish public sphere, the current article aims to explore how and to what extent they all played prominent role in how, in its discourse, the Swedish press would perceive immigration as well as effectively changing patterns of its representation between 2010 and 2022. While our general hypothesis here is based on the assumption that the portrayal of immigration by the Swedish press would not noly significantly alter but also become ever more negativised over time, we also rely in our study on a number of further sub-hypotheses (see also ), i.e.:

Political-ideological-factor sub-hypothesis: which interrogates the salience of dynamics of public debates on immigration developing under intensified impact of political-ideological framing in the periods leading directly to, or immediately following, the key national-parliamentary elections in the period 2010–2022 (specifically in years of 2010, 2014, 2018 and 2022).

Contextual-factor sub-hypothesis: which recognises the potential salience of such key immigration-related developments and contextual factors of the 2010–2022 period as, in particular, the 2015–2016 “Refugee Crisis” in Europe during which a significant shift occurred in Swedish immigration politics/policies/attitudes towards migrants, refuges, and asylum seekers.

Imaginary-recontextualisation-factor sub-hypothesis: which looks into the salience of recontextualisation of debates and imaginaries related to issues other than immigration – in particular public debates surrounding “criminality”, widely evident in Sweden from 2018 onwards – for the eventual creation of wider immigration- and multiculturalism critical “proxy discourse” (Ekström, Krzyżanowski, and Johnson Citation2023).

Pursuing the above hypotheses, as well as exploring the interplay of various discursive and wider social dynamics they encompass, the study aims to illustrate the key discursive shifts that occurred in Swedish discourses and imaginaries of immigration and multiculturalism throughout 2010-2022. It does so by way of tracing ideas, positions and arguments and their construction in, as well as recontextualisation by/into, the analysed Swedish press discourse. The press is, therefore, analysed as part of a wider Swedish public sphere and of its media landscape which has played active role in the observed social changes and especially in the discursive shifts in public discourse. Hence, the press as our object of study is perceived here as one of key active agents of the Swedish public domain and a key opinion-making voice. It not only passively or neutrally “reports upon” or merely “replicates,” e.g. political opinions and/or ideological views but can itself be potentially contributing to the deepening and progressive normalisation of various immigration-related views in the Swedish public domain (Krzyżanowski and Ekström Citation2022).

Accordingly, while the analysis presented here recognises the significance of key political dynamics – by generally anchoring the research design around the key electoral campaign periods that occurred in 2010–2022 (see Sub-hypothesis 1, above) – it still views the press as making its own and indeed significant contribution, both as far as manufacturing of its own discourse and when relying on various patterns of “recontextualisation” (Bernstein Citation1990; Krzyżanowski Citation2016) of wider public including political narratives and views. That process, as we show below, often allows the press to construct a hybrid discursive “voice” (and agency), by either amalgamating various political ideological positions and views and/or by combining as well as dynamically interchanging those with discourses related to, e.g. immigration-related contextual developments and events (in particular the 2015–2016 ff “Refugee Crisis”; see Sub-hypothesis 2). Finally, we also investigate if/how the Swedish press could be constructing – or at least carrying across and disseminating – the discourses which, while initially not pertaining to immigration per se, would eventually become key containers for negativised immigration- and multiculturalism-related views (see our Sub-hypothesis 3, above).

Our study builds on earlier extensive analyses of discourses on immigration in Swedish politics, and especially on the works emphasising its (strategically) “hybrid” and ambivalent character (see, e.g. Demker Citation2015; Krzyżanowski Citation2018a). However, we also draw extensively on the significant body of work which has shown that complexities of the increasingly negative portrayal of immigration in the Swedish media not only accelerated (Bolin, Hinnfors, and Strömbäck Citation2016) but also further deepened (Ekman and Krzyżanowski Citation2021) in/throughout the second decade of 2000s and in its aftermath. We hence aim to bring various insights together and show that – as evidenced in/by the press – they occurred in correlation with acceleration of other public debates and in relation to key contextual factors. We follow a comprehensive view on the role and dynamics of press discourse as located at the intersection of media and the political, and offer analysis of not only selected media genres (such as, e.g. editorials) but also of the press discourse more widely. At the same time, we offer a study covering the entire period 2010–2022 to follow a timeline starting in 2010 (i.e. when Swedish far-right Sweden Democrats, or SD,Footnote1 entered the national parliament), going through the period before/after the 2015–2016 Refugee Crisis which constituted the key break for many “traditional” discourses on immigration, and up to the most recent 2022 national parliamentary campaign and elections which saw the far-right make very significant gains including under immigration-critical and nativist slogans.

2. The changing and ambivalent attitudes towards immigration in Sweden

In the second half of the twentieth century, Sweden became internationally known as one of Europe’s key countries of open multiculturalism where standards of social and gender equality as well as of the widely-praised, inclusive welfare state model (Östberg and Andersson Citation2013) all worked in sync with largely positive attitudes towards immigration as part of Swedish socio-political value system. However, to say that such openness towards migrants and asylum-seekers/refugees met with continuous and stable public support would probably be an oversimplification. Namely, already from the late 1980s onwards, public attitudes towards immigration in Sweden would often change, frequently on a par with various transnational developments and especially in periods of their local (national) accommodation including ensuing politicisation and mediatisation (Krzyżanowski, Triandafyllidou, and Wodak Citation2018).

Such a pattern was, probably, most conspicuously established in the aftermath of the arrival of Central- and Eastern European refugees in Sweden (and elsewhere) after the Fall of the Iron Curtain in the late 1980s. Then, despite inital openness, specific “moral panics” would eventually come to be built in media and especially politics effectively also brining a notable change of immigration-related attitudes. These would soon be politicised including via the so-called 1989 “St Lucia’s Day Decision” (Luciabeslutet) tightening Swedish asylum-related laws (Andersson and Geverts Citation2008; Demker Citation2023). As is, however, quite often the case with such strategies of mobilising the change of immigration-related public moods for political gains (Rydgren Citation2002, Citation2006), those actions may, despite being initiated in and by the political and media mainstream (Hinnfors, Spehar, and Bucken-Knapp Citation2012), eventually weaken the latter and strengthen radical movements. Such would indeed be the case in Sweden of the said late 1980s and ealry 1990s. At that time, the country’s first post-war right-wing populist party, the “New Democracy” (Ny Demokrati, NyD), would emerge as well as enter the Swedish parliament in 1991, i.e. in the aftermath of the Luciabeslutet and while using anti-immigration slogans against the fertile ground of the already changed, immigration-related moods.

However, due to the evident political failure of the Swedish early far right capitalising on anti-immigration moods (NB: the ND would only remain in the parliament for one short term in 1991-1994), and, seemingly despite the earlier/initial scare built around immigration in the late 1980s and the early 1990s, attitudes towards immigration in Sweden would gradually become ever more positive – and certainly ever less negative – and remain such throughout the remainder of the 1990s. This, paradoxically, would occur despite the then still progressing change of national asylum and other immigration laws (Abiri Citation2000). Interestingly, immigration-related attitudes would not even change in face of arrival, and later evolution, of a new Swedish far-right party – the “Sweden Democrats” (Sverigedemokraterna, SD) from the early 2000s onwards (Wildros Citation2017). Indeed, it is argued that following the earlier experiences with the ND in the 1980s/1990s, an efficient cordon sanitaire would be built around the “new” far-right and its anti-immigration claims by the mainstream parties and the media in early 2000s (Backlund Citation2023). This would largely remain unbroken for a significant period of time, with only the 2015ff “Refugee Crisis” bringing a revival of the ever more-negative immigration attitudes in the public discourse and the wider public imagination (Ekström, Krzyżanowski, and Johnson Citation2023).

However, the above trend of a relatively continuous lack of radical anti-immigration attitudes would eventually undergo a significant change from ca. 2015. Those dynamics would commonly be associated with the 2015ff “Refugee Crisis” while, however, de facto combining several reasons. These would include, inter alia, a strong politicisation of immigration by a number of mainstream parties – in addition to the SD on the far-right (Rydgren and van der Meiden Citation2019) – in the run up to, as well as the aftermath of, the 2014 Swedish parliamentary elections (Krzyżanowski Citation2018a). Since then, namely, not only would the negative attitudes towards immigration as such increase among the wider Swedish populace but they would also enter for good as well as eventually progressively spread across political and media agendas (Demker Citation2015, Citation2016; Krzyżanowski Citation2018a). They would, subsequently, create a background to the ever more expressly exclusionary politics and policies (Goldschmidt and Rydgren Citation2018) as well as having a spill over effect onto more persistent patterns of negative politicisation and mediatisation of immigration inclding in the media (Theorin and Strömbäck Citation2020).

3. Discursive shifts on immigration in/and the Swedish media

This study draws on two fields of research: on the specifically political process of the ideological “mainstreaming” of the far-right and its ideologies (Mondon and Winter Citation2020; Odmalm and Hepburn Citation2017; Rydgren and van der Meiden Citation2019) and on the deeper, social-wide dynamics of “normalisation” of exclusion as a token pervasiveness of “illiberal” exclusionary thinking in the public domain (Kallis Citation2021; Krzyżanowski Citation2018a, Citation2018b, Citation2020a, Citation2020b; Krzyżanowski et al. Citation2021, Citation2023; Laruelle Citation2022; Mudde Citation2019; Wodak Citation2021). We contend that during the often closely entangled mainstreaming and normalisation processes, anti-immigration sentiments often become ever more prevalent in the public domain while the portrayal of immigration and multiculturalism as “challenges”, or even as “threats” to society, is made into the acceptable “new normal” (Krzyżanowski et al. Citation2023). The above, we claim, builds on the ever more evident recurrence of discourses wherein immigrants are framed as a default “other” of (however imaginary) native “people” and “society.”

Both processes above – yet particularly the wider and deeper logic of normalisation – are best grasped by the idea of strategic discursive shifts (Krzyżanowski Citation2018a; Citation2020b; Krzyżanowski and Krzyżanowska Citation2022). The latter makes it possible to identify how and when public and political discourses transform and when various calls for exclusion are often, first, enacted, then, perpetuated, and eventually, normalised, in line with pronounced strategies of political, media and other public sphere actors. This process creates recurrent path dependencies by allowing exclusion to be “pre-legitimised” (Krzyżanowski Citation2014) as well as fuelled via the wider “atmosphere of incitement” (Wodak Citation2015, Citation2021).

Indeed, existent empirical studies on Swedish media’s reporting on immigration have all been pointing quite extensively to several such “discursive shifts” taking place in recent years (Strömbäck, Andersson, and Nedlund Citation2017). They showed that “mainstream” media coverage of immigration increased exponentially in Sweden between the 1960s and ca. 2015 (Asp Citation1998; Bolin, Hinnfors, and Strömbäck Citation2016; Hedman Citation1985; Hultén Citation2006; Strömbäck, Andersson, and Nedlund Citation2017) thus widely following international patterns of reporting (Benson Citation2013). However, they also showcased that the qualitative change of discourses has evidently taken place. Already the 1980s mentioned above have been a significant transformative period for when the imaginary of immigration significantly negativised for the first time in post-war Swedish media (Hultén Citation2006). Thereby, immigrants’ portrayal shifted: from being considered as an asset and essential prerequisite for the construction of the Swedish economy – to the view that immigrants, at best, constitute an economic burden for society. This shift was explained in many ways, but most exponentially by the transformation of the Swedish migration policy: from one initially focussed on guest-worker programmes in the 1950s and 1960s, to one oriented towards political and other refugees arriving from 1970s onwards (Hultén Citation2006, 213; Nilsson Citation2004).

In the early 1990s, then, there was another significant “discursive shift” in Swedish news media’s framing and reporting of immigration. Due to increased refugee immigration to Sweden as a result of the war/s in the Balkans, namely, the media to a much greater extent focussed on refugee-related issues with news also becoming ever more sensationalist, conflict-oriented and focused on societal and economic challenges (Asp Citation2002; Ghersetti and Odén Citation2018). These shifts, importantly, eventually also created a longer path-dependency – of especially negativisation of immigration portrayal – for decades to come (Asp Citation2002; Hultén Citation2006). Indeed, as shown in a number of later analyses (Brune Citation2004; Strömbäck, Andersson, and Nedlund Citation2017) from 1990s onwards the Swedish news media by default tended to focus on refugee immigration and its costs – rather than on other types of immigration. Additionally, immigrants would be frequently connected to issues of criminality, violence, and to general challenges to law and order in the country (Brune Citation2004; Hultén Citation2006). In this context, as Strömbäck, Andersson, and Nedlund (Citation2017) highlighted, media’s highly ambivalent role in replicating negativised perceptions of immigration would become obvious on a par with its rather evident inability to provide corrective tendencies or alternatives allowing for a less negative tone of the discourse on immigration.

Additionally, already at the beginning of the 2000s, several Swedish official reports (e.g. SOU Citation2006, 21; Citation2007, 102; Citation2012, 74) emphasised that media reporting on immigration has changed in Sweden and that its increasing negativisation could have had long-lasting impact on the wider public discourse. Not surprisingly, hence, media discourse analyses which followed in, especially, the 2010s, clearly pointed to the negativisation of media discourse on immigration and argued for its path-dependent character. For example, it would be shown that nationwide newspapers would have focussed on refugee immigration even well before the 2015ff “Refugee Crisis” (Strömbäck, Andersson, and Nedlund Citation2017). At the same time, immigration would also be increasingly embedded in frames of weakening social cohesion, of criminality, and of economic burden (Strömbäck, Andersson, and Nedlund Citation2017: viii). Similarly, analyses of Swedish nationwide newspapers between 2010 and 2015 (Bolin, Hinnfors, and Strömbäck Citation2016) would show that negative perspectives on immigration dominated over positive ones in addition to having progressively increased over time. In a similar vein, analysis of editorials in the aftermath of the 2015–2016 “Refugee Crisis” (Ekman and Krzyżanowski Citation2021) would also show that the press has moved from issue-based perceptions/descriptions to the negative, value-based framing. Indeed, this tendency would be made evident even in the most recent studies focussed on negative portrayal of specific ethnic and cultural groups (such as, e.g. the Roma – see Breazu and Machin Citation2024).

4. Empirical data

The empirical data analysed below draws on articles published in Swedish nationwide liberal and conservative broadsheets (Dagens Nyheter, DN, and Svenska Dagbladet, SvD), in tabloids (Aftonbladet, AB, and Expressen, Ex), in addition to widely-read regional newspapers (Göteborgs-Posten, GP – published in West-Swedish Gothenburg, and Sydsvenskan, Syd – published in South-Swedish Malmö). These outlets traditionally share the highest percentage of national newspaper readership in Sweden as well as remaining main newspapers in terms of readership outreach, including in the years of 2010, 2014, 2018 and 2022 focused upon in the study (see Orvesto Citation2011, Citation2015, Citation2019, Citation2022). Additionally, via our choice of sources, the corpus effectively covered outlets from Sweden’s most populated areas and from the country’s major cities. The data also spanned various newspaper genres including news-reports and articles pertaining to news, sports and culture in addition to editorials, debate articles, and letters to the editor. The data has been identified and collected using the Mediearkivet (Retriever Research) database.

Given our hypotheses followed in the study, the longitudinal character of the corpus has been assured by focusing on four temporally ordered periods in 2010, 2014, 2018 and 2022 thus effectively allowing to cover each of the election periods within the scope of investigation as well as the more general diachrony of discourse. The first step in the construction of data corpus was to delimit its scope to six months before and after each election day: 19th September 2010, 14th September 2014, 9th September 2018, and 11th September 2022. The second step, then, was to use the discourse-specific logic by phrasing a query for the keyword search. To begin with, this included “Sweden” and any of the truncated keywords “immigrant,” “refugee,” “asylum seeker,” “migrant,” “newcomers,” “foreign-born,” or “ethnic.” However, to make the data sample more relevant, the query would also be supplemented with keywords that more closely indicated issues persistently put in connection/relation with/to immigration in the Swedish public discourse (see above), i.e.: “welfare,” “unemployed,” “benefits,” “Islam,” “integration,” “alienation,” “crime,” “violence,” “criminal,” and “gang.” This resulted in the following query (in Swedish): “Sverige AND (invandr* OR flykting* OR asylsök* OR migrant* OR nyanländ* OR utrikesfödd* OR etnisk*) AND (välfärd* OR arbetslös* OR bidrag* OR islam* OR integration* OR utanförskap* OR brott* OR våld* OR krimin* OR gäng*).”

The searches conducted with the above query within the given sampling periods resulted in a general corpus of 10 101 articles in total. While this “large” corpus served the analysis of the general discourse and corpus dynamics (see below), the eventual in-depth CDA required a further down-sampling in order to make the sample manageable (see Baker et al. [Citation2008] for the full description of such a down-sampling procedure). Hence, a “smaller” (downscaled) corpus was subsequently also created with the focus on 14-day periods (a week before and after each election date), resulting in 952 articles in total. Qualitatively, the “small” corpus would then be further restricted to articles covering not only “immigration” and “immigrants” but also at least one or several of the related topics (above). Effectively, the down-sampling would render a total of 290 articles from the four election years in question () that would be, subsequently, put under a close, in-depth Critical Discourse Analysis (see below for the key results).

Table 1. Articles in the period 2010–2022 per each election year and analysed newspaper (after both quantitative and qualitative down-sampling).

5. Analysis & key findings

5.1. General press discourse/corpus dynamics over time

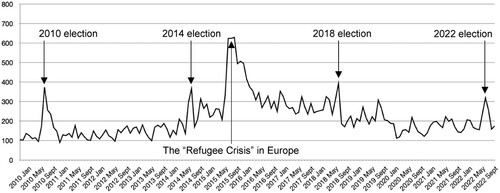

To some extent confirming our hypotheses – and specifically the political-ideological-factor one (above) – emphasises that a number of peaks in press discourses on “immigration” in the period 2010–2022 occurred in close connection with the widely-defined election periods. However, while the election periods yielded a number of significant increases in press reporting on “immigration” as such, we at the same time also find a confirmation of our contextual-factor-hypothesis. Namely, in particular, the 2015–2016 “Refugee Crisis” emerged as the key factor that yielded a peak in press reporting/discourse that doubled the highest scores during the election periods. This emphasised the combination of the two hypotheses above but also predominance of the contextual-factors.

Figure 2. Distribution of articles per month mentioning “(invandr* OR flykting* OR asylsök* OR migrant* OR nyanländ* OR utrikesfödd* OR etnisk*) AND (välfärd* OR arbetslös* OR bidrag* OR islam* OR integration* OR utanförskap* OR brott* OR våld* OR krimin* OR ang*) AND Sverige” (truncated versions of “immigrant,” “refugee,” “asylum seeker,” “migrant,” “newcomers,” “foreign born,” or “ethnic,” and “welfare,” “unemployed,” “benefits,” “Islam,” “integration,” “alienation,” “crime,” “violence,” “criminal,” or “gang,” supplemented by “Sweden”) in AB, DN, Ex, GP, SvD, and Syd 2010-01-01 and 2022-12-31.

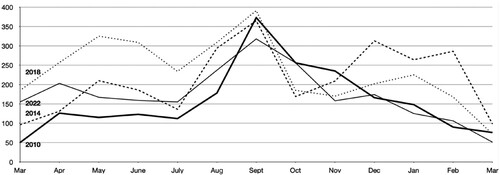

confirms the above dynamics wherein the most significant peak in the reporting would occur during the “Refugee Crisis” with not only far more significant size if compared to the election periods but also a much more prolonged character (close to 12 months in total). The figure also shows evident peaks occurring in the reporting during each of the election periods throughout our wider time-scope under investigation (2010-2022). This tendency, which is also evident in showing election periods in overlay, points to the fact that election months (September) were, in fact, the highest ones in reporting frequency in the election years (2010, 2014, 2018, and 2022). They were also accompanied by the rather usual “waves” (i.e. subsequent increases/drops in reporting) taking place in months both preceding and following the actual elections.

Figure 3. Distribution of articles per month, six months before and six after the election day in 2010, 2014, 2018, and 2022 with mentions of “(invandr* OR flykting* OR asylsök* OR migrant* OR nyanländ* OR utrikesfödd* OR etnisk*) AND (välfärd* OR arbetslös* OR bidrag* OR islam* OR integration* OR utanförskap* OR brott* OR våld* OR krimin* OR ang*) AND Sverige” (truncated versions of “immigrant,” “refugee,” “asylum seeker,” “migrant,” “newcomers,” “foreign born,” or “ethnic,” and “welfare,” “unemployed,” “benefits,” “Islam,” “integration,” “alienation,” “crime,” “violence,” “criminal,” or “gang,” supplemented by “Sweden”) in AB, DN, Ex, GP, SvD, and Syd (total 10 101 articles).

Comparing all of the different election periods above, the 2014 one stands out as somewhat less sizeable – though it is worth emphasising that, as such, this period was also unusually prolonged due to the extended time taken up by the government coalition negotiations in the aftermath of Sept 2014 elections. Also, we argue, the discourse would by then focus only partially on immigration and/or refugees as such given that many of immigration- and multiculturalism-related issues would have gradually be taken over by then emergent “proxy discourse” on criminality that would later become evident from ca. 2018 onwards (Ekström, Krzyżanowski, and Johnson Citation2023).

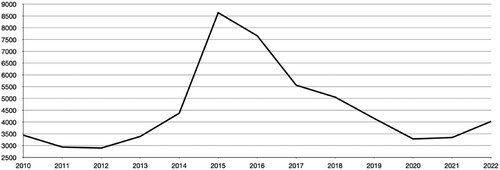

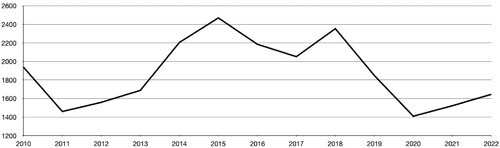

Looking into how the discourse on, and frequency of, immigration-related topics in the media coverage would change between 2010 and 2022, the graphs below ( and ) present the results for all years during the analysis period. Common to these graphs is the fact that, just like in similar studies but with a focus on the period 2010–2014 (Bolin, Hinnfors, and Strömbäck Citation2016; Strömbäck, Andersson, and Nedlund Citation2017), they reveal an overall increase in the reporting on immigration issues between 2012 and 2014, a peak in connection with the 2015ff “Refugee Crisis” in Europe and in its immediate aftermath, and, finally, a decline of discourse by 2020, before, in 2022, a new increase would begin in the run-up to the election. In particular, as displayed in – presenting only the “immigration” related discourse – notions related more strictly to immigration started to radically increase only as of 2014 (the initial phase of the “Refugee Crisis”) to eventually peak in early 2015 when, contextually speaking, numbers of refugees arriving in Sweden started to decrease yet stricter refugee-related policies were soon adopted (see Krzyżanowski Citation2018b).

Figure 4. Distribution of articles per year mentioning “(invandr* OR flykting* OR asylsök* OR migrant* OR nyanländ* OR utrikesfödd* OR etnisk*) AND Sverige” (truncated versions of “immigrant,” “refugee,” “asylum seeker,” “migrant,” “newcomers,” “foreign born,” or “ethnic,” supplemented by “Sweden”) in AB, DN, Ex, GP, SvD, and Syd between 2010-01-01 and 2022-12-31 (totally 58 743 articles).

Figure 5. Distribution of articles per year mentioning “invandr* AND Sverige” in AB, DN, Ex, GP, SvD, and Syd between 2010-01-01 and 2022-12-31 (total 20 108 articles).

Considered more closely, the above discourse dynamics displayed several further tendencies. For example, as is shown in , a “localised” or “domesticated” combination of keywords (e.g. “immigration” and “Sweden”) reveals discourse peaks at several occasions: not only in 2014–2015 as above but also in, e.g. the early 2018 that should be considered as part of a run-up to the elections later that year. Interestingly, while, over time, we first see the increase of “immigration” as a keyword rather late – i.e. before and then after the “Refugee Crisis” 2014–2015, with the said concept preceding and later replacing that of “refugees” – it is also the “immigration” and “Sweden” combination which decreases rather rapidly. This happens from 2018 onwards when a new discourse explictly combining “immigration” and “criminality” emerges, yet before the “immigration” concept as such eventually disappears in the course of construction of “proxy discourse” on criminality (Ekström, Krzyżanowski, and Johnson Citation2023). The latter would often implicitly – hence not in a way that is effectively traceable to a corpus/keyword analysis – frequently allude to and imply “immigration” yet without nominally using that term/keyword as such.

5.2. Key voices, actors, & topics in Swedish media discourse on immigration 2010–2022

Our entry-level discourse examination, typical for a multilevel critical discourse analysis (Krzyżanowski Citation2010), zooms in at combination of key topics and voices in discourse while thereby highlighting strategic construction of agency in the press reporting. The analysis examines whether it is the media itself who kept its own “voice” in thematising relevant, immigration-related matters (e.g. via opinions expressed by the journalists, editors and the like) or whether other – and in particular political – actors (individual politicians, political parties) would instead be allowed to express opinions and debate issues at hand. This focus is vital given the overall tendency of the Swedish press to overwhelmingly rely on various (own or other) voices in its discourse and reporting. Our analysis therefore combines the examination of, on the one hand, the key debated themes and foci – encompassed in a typically critical-analytical examination by various “discourse topics” (Krzyżanowski Citation2010; van Dijk Citation1991) – while also relating their exploration to the tracing who specifically in the media reporting was given agency to express the said topical issues and hence held the key “voice” (Bakhtin Citation1981; Citation1984; Pietikäinen and Dufva Citation2006).

As is indicated by the overview of key topics over time (see and ), there has been a particularly obvious shift in the discourse on immigration in the Swedish press between the two elections of 2010 and 2014 on the one hand, and those held in 2018 and in 2022 on the other. In the context of the 2010 & 2014 elections, the SD remained the key actor “voicing” calls for a stricter migration policy while specifically focussing on immigrants on the one hand, and on Islam/Muslims on the other. It is vital to note that such thematic and voice dynamics dovetails with relevant “discursive shifts” emerging from 2010 onwards when the SD entered the Swedish parliament. Already in 2010, namely, much of the focus of the media was explicitly on SD and the party's role as openly critical of Islam. In that context, the SD explicitly perceived itself as the only party that “dared” to express such opinions (a common trope among the European far-right of early 2010s; see Krzyżanowski Citation2013) while, allegedly, doing so on behalf of the wider Swedish (native) population. At that time, to be sure, calls for stricter immigration-related policies – e.g. the Liberals’ (L) demand of Swedish language tests as a prerequisite for citizenship or alike – would still be seen as isolated and viewed as unwelcome in the political “mainstream.” However, in the following national elections of 2014, the discourse would gradually turn its focus. Mainly expressed in the press by, again, the SD actors, it would predominantly include themes on “prioritising” welfare for the “natives” and on avoiding welfare provisions for the “other.” However, at that point, the welfare-related framing of immigration would also increasingly be highlighted by other including “mainstream” actors as well as being widely reported in the press.

Table 2. Combined list of key discourse topics in Swedish Press reporting on immigration during national elections periods of 2010 & 2014.

Table 3. Combined list of key discourse topics in Swedish Press reporting on immigration during national elections of 2018 & 2022.

Contrary to 2010 and, to some extent, also 2014, the situation in 2018 and 2022 would clearly be much more dynamic and diversified, indeed both in terms of variety of topics discussed and of actors given “voice” in the press discourse to express immigration-related views. During the election campaigns of 2018 and 2022, namely, most of the mainstream parties would emerge as by then already holding clear and relatively elaborate, and in most cases rather obviously far-from-liberal, stance on immigration. Accordingly, “voices” arguing for various immigration restrictions (initially, mainly with regard to “refugees”) would come to be expressed ever more clearly and across the wider political spectrum. At the same time, in 2018 & 2022, the debates would on a whole revolve around issues that could directly or indirectly – and explicitly as well as implicitly – be related to immigrants/immigration, with indeed all/most actors – including far-right and mainstream politicians as well as the media – voicing concerns with regard to immigration-related politics and policies.

Crucially, as mentioned above, the 2015 “Refugee Crisis” would emerge here as the key line dividing the above, election-centred periods of (a) the early 2010s and (b) the late 2010s & early 2020s, in addition to being the key factor influencing the 2018 & 2022 period. Indeed, this emphasises that the “Refugee Crisis” had a clear impact on the qualitative aspects of the press discourse in the aftermath of 2015 (note, e.g. the topics related to refugees or to a synonymous “non-European immigration”; see ) but also constituted a much more profound contextual breaking point resulting in the introduction of exclusionary and nativist views and their progressive normalisation.

5.3. Key insights from the in-depth critical discourse analysis

Given this study draws on existent in-depth analyses of Swedish immigration-related press discourse before/until 2015 (see Bolin, Hinnfors, and Strömbäck Citation2016) and thereafter (Ekman and Krzyżanowski Citation2021), our below focus of in-depth Critical Discourse Analysis (Krzyżanowski Citation2010) is on key deployed argumentation schemes – or topoi – and on the supporting discursive strategies that either persisted over time in the entire 2010–2022 period, or would become evident as that period would have axially evolved.

The first argumentation scheme that remained paramount was certainly the one related to the ever more persistent distancing between “us” and “them,” and to creation of the persistent nativist imaginary that eventually enabled gradual introduction and recontextualisation of frames emphasising the rights of natives over the “non-native them.” A consistent feature of many articles over time, namely, was in their construction of imagined reader as a native, which thus created an implicature of a wider “us” voice and of a peculiar “phatic communion” (Malinowski Citation1920; Senft Citation1995) existing between journalists/authors and readers. This meant types of argumentation wherein the press texts would objectify and de-agentify immigrants and rarely, if at all, address them as interlocutors, indeed despite migrants being de facto focus of the discourse/reporting as such. In this context, the use of strategies of “self-and other presentation” (Reisigl and Wodak Citation2001) and of the discursive “representation of social actors” (van Leeuwen Citation2008) became apparent. They supported various de- and re-agentification patterns with “immigrants” shown as either active or passive depending on the implied relations with, and actions vis-à-vis, the “natives” or the generic “Sweden” more widely (see Examples 1–3).

Example 1: Immigrants already play an important role in the Swedish labour market. (SvD, 2014/09/12Footnote2)

Example 2: The moderates’ party leader has claimed that exclusion passed down from immigrant parents to their children is “the single biggest social problem in Sweden today”. (AB, 2018/09/07)

Example 3: He means that people in vulnerable areas in general and Swedish-Somalis, in particular, have become a tool in gesture politics. (DN, 2022/09/11)

The second, albeit related, persistent feature of the Swedish press discourses on immigration in 2010–2022 was its focus on the topos of the Swedish self-image, and particularly so from the 2015ff “Refugee Crisis” onwards (see especially Krzyżanowski Citation2018a). Indeed, a recurring feature in the media in the context of the four election periods in focus was that the success of SD, as well as of the wider anti-immigration opinions and related calls for various forms/degrees of politics of exclusion, were often discussed in relation to the Swedish self-image. The latter, paradoxically, rested on the idea of “Sweden” as an open, humanitarian, and tolerant country while therein also highlighting aforementioned “Swedish exceptionalism” (Breazu and Machin Citation2024; Rydgren and van der Meiden Citation2019). The image of Sweden as “the fortress of liberalism and tolerance, immune to extreme right-wing parties” (Ex, 21/09/2010) was, apparently, also presented as the one held internationally. However, since 2010 onwards, ever more voices have been raised claiming that this image of Sweden was at least about to change (see Examples 4-6). In the same guise, press outlets even took a somewhat more self-critical tone and intermittently acknowledged that the Swedish self-perception may have perhaps been too self-righteous to begin with, up to the point of possibly even obscuring the problems in society (e.g. DN, 16/09/2014; DN 14/09/2022). It was also claimed that mainstream media’s alleged creation of a limited “corridor of opinion”Footnote3 – a synonym used in illiberal criticism of liberal stance towards immigration in Sweden – effectively made it impossible to discuss immigration in other than just humanitarian or post-humanitarian way (SvD, 11/09/2022).

Example 4: On Sunday, everything changed. Sweden is no longer the haven of tolerance. (Syd, 2010/09/21a)

Example 5: We must start with perhaps the hardest part of all, looking at ourselves in the mirror and realising how false our self-image is. (DN, 2010/09/21)

Example 6: The idea of Sweden as a progressive oasis, a nation with modern values, which has been the basis of our self-image, no longer applies. (Syd, 2022/09/13)

Similarly, the Swedish self-image topos was vital in press representations of political parties in the context of immigration. Here, even though the SD was, at least initially, largely deemed as anti-immigration by the media and by the mainstream parties, a recurring description of the SD voters was different and saw them as, essentially, and quite paradoxically, non-xenophobic. This was as a rather vital normalisation strategy which effectively “classified” a political party – and its political “voices” – as radical, yet at the same time mitigated representation of its voters and their opinions/views (an issue that also harks back to the nativist frame above – as it highlights the rights of natives on the one hand, and their apparent confusion regarding political choices on the other; see Examples 8-9).

Example 8: I think that the Sweden Democrats is the party of dashed hopes. It’s much more about that than ideological racism. (Syd, 2010/09/21b)

Example 9: But is everyone who votes for SD anti-immigrant? Far from it, most are disappointed, as Stefan Löfven says. They are disappointed in many other things; unemployment, healthcare, school and elderly care. But above all, they are disappointed that nothing is being done. (AB, 2014/09/17)

The above line, synergetic with the wider topos of denial of xenophobia/exclusion was in itself a type of positive self-presentation wherein both individual and social dimensions were mobilised to defend the “we” ingroup by disclaiming its exclusionary views and intentions (van Dijk Citation1992). In the analysed press discourses, even high-ranking politicians were quoted as subscribing to the image of the non-racist Swedish society, including then/later government officials given “voice” and quoted in the press (see Example 10, a quote from the then immigration minister from L; or Example 11: with the then opposition leader and later prime minister from M). In this context the eventually widespread “conceptual flipsiding” (Krzyżanowski and Krzyżanowska Citation2022, Citation2024) strategy would also emerge and allow using a reversal of liberal-democratic concepts (e.g. in Example 10, of “equality”) in defence of Swedish society as inherently non-xenophobic, etc. At the same time, classic forms of denial of exclusion by using “disclaimers” (van Dijk Citation1992) would also become evident (see, e.g., the use of “but” in Example 11).

Example 10: No, I do not think so. We have something to be careful with, there is broad support around the idea that we should treat everyone equally. (GP, 2014/09/12)

Example 11: Sweden is not a racist country, but many Swedes see an integration policy that does not work, with gang shootings and people who are dependent on benefits. (AB, 2018/09/08)

Within the framing and argumentation such as above, strategies of what van Leeuven (Citation2007) referred to as “legitimation through path dependency” (i.e. by way of reference to “natural” order of things and/or to path-dependent logics of social events and actions) would also be applied to legitimise why an increasingly large part of Swedes voted for SD. A common argument was that the mainstream parties have, allegedly, long been avoidng immigration-related debates and unwilling to discuss or “deal with” immigration and integration. Hence, it was argued, those issues as if “naturally” eventually fell into the lap of the far-right which, apparently, was willing to take them up in order to avoid the even further “tabooisation” of the immigration issue (see Examples 12 & 13).

Example 12: “I also think that Sweden should have a generous immigration policy, but we must not taboo a discussion about integration” (DN, 2014/09/17).

Example 13: “The political parties have put aside the integration issues in order to avoid the debate and thereby risk provoking their own voters” (AB, 2010/09/21).

Example 14: SD is strong in those places where Sweden is not successful, where job opportunities are fewer, and the population is decreasing. (Ex, 2014/09/17)

Example 15: It is a gross simplification to call them [SD voters] racists. They are afraid and lost in multicultural Sweden. (Ex, 2014/09/15)

Nevertheless, the press discourse would still intermittently admit that the growing support for SD was not only the case of a passive path-dependence, “coincidence” or of “feeling lost” (see above) – but that it de facto correlated with the growing appeal of, and support for, anti-immigration ideas and xenophobic attitudes in Sweden (see Examples 16-18). However, even then the arguments would be expressed that, while there was indeed a change in the Swedish society as such, the said process would be disclaimed as not, in fact, a “nativist turn” as was argued above. Instead, the change would be normalised by being perceived as “natural” given the many social, political and economic changes happening more widely, in Sweden and beyond, and in that way affecting the “people” (so-called “ethnonationalist victimhood,” Breazu and Machin Citation2022). In this context, hence, the support for SD and anti-immigration agenda would again be, effectively, normalised as well as “pre-legitimised” (Krzyżanowski Citation2014) as, as if, a part of natural order of things and of wider, path-dependent logic of social schange.

Example 16: The Sweden Democrats is in the parliament because there is a part of the electorate that likes the party’s ideas. They know what the Sweden Democrats stands for. They don’t vote for the party despite it exorcise prejudices about Muslims and want to limit immigration. They vote for the party because of just that. (DN, 2010/09/21)

Example 17: Sweden is a country where racism, exclusion and discrimination are increasing exponentially even though the established parties, apart from the Sweden Democrats, condemn and reject racism, discrimination, and the growing segregation. (SvD, 2014/09/16)

Example 18: There is a lot to love in Sweden – but there is also a lot of covert racism and xenophobia that has come to the surface now. (AB, 2018/09/09)

Interestingly, however, the press discourse would often be selective in its “normalisation-spotting,” i.e. it would spot it in some context yet ignore it elsewhere (more widely as a token of the so-called “calculated ambivalence,” Wodak Citation2003). This would significantly reinforce the overall tendency towards hybridisation and increasing ambivalence of press discourse vis-à-vis anti-immigration views.

The above would also, effectively, impact the (in)stability of opinions held by the press as far as the far-right and its anti-immigration stance. The SD would, thereby, often be seen as “double-faced” (Akkerman Citation2016; Moffitt Citation2021) – especially as far as disguising its ideological background and roots (De Witte Citation1996). Here, the press would most frequently use strategies of “intensification” (Reisigl and Wodak Citation2001) and, e.g. quote various radical statements by SD politicians to emphasise their and thus the party's radical views. In this context, both national-level SD politicians would often be quoted (see Example 19 – with a press quote from SD member of parliament, or Example 20 – with press quoting a tweet by SD’s legal policy spokesperson alluding to the party's ideas of “repatriation” of immigrants). However, the more radical statements would be taken up by the press from the SD regional-level functionaries (see especially the multiple quote “compound” in Example 21) while, at the same time, avoiding construction of such a radical image with regard to national-level SD politicians.

Example 19: “The West has faced Islam on the battlefield many times throughout history. It’s the same battle now” (AB, 2010/09/10).

Example 20: “Welcome to the repatriation train. You’ve got a single ticket. Next stop, Kabul!” (Ex, 2022/09/11).

Example 21: “Send all Gypsies out of the country with a total ban on returning”, “You bloody half-apes I want to kill you”, “Parasites”, and “Sweden should rather be invaded by cockroaches than by Africans” are all comments from SD municipality candidates in the 2014 election (DN, 2014/09/15).

6. Conclusions

The analysis above confirms our main hypothesis pertaining to the change and negativisation of Swedish press’ portrayal of immigration over time, and in particular throughout our period of investigation (2010–2022). Correlated with the parliamentary entry and the ensuing growth of public support for the Swedish far-right – constructed, at least initially, as the main articulator of anti-immigration views – the said negativisation of discourse pertained to wider dynamics whereby immigration-related issues would be debated ever more broadly in the press over time. As we have shown, that growing breadth and depth of discourse would effectively carry the said negativisation: with the number of issues and complexity of argumentation growing, previously radical views could be ever more widely debated and normalised, and ever less contested or mitigated. This, as we have noticed, would be the case practically irrespective of the type of outlets (quality/tabloid, liberal/conservative, nationwide/regional), and would emerge as a general tendency wherein the press would stand on a par with the general trajectory of immigration-related discourses of the wider Swedish public sphere.

Crucially, the process of the apparent, gradual negativisation of Swedish press discourse on immigration occurred, as we have shown, within the logic of strategic manufacturing of hybridity and ambiguity and the press's strategic avoidance of explicit self-positioning. While becoming ever more ambiguous, hybrid, and ambivalent, namely, the press discourse would rely on a variety of discursive strategies enabling a wide array of perceptions and representations to be formed and “packaged”. This would be achieved by shifting between acceptable discourses and frames and (quoting) radical opinions – i.e. within the frames of the so-called “borderline discourse” (Krzyżanowski and Ledin Citation2017) – and especially while using strategies of the press’ avoidance of its own agency in that process (see our findings on multiple non-press “voices” widely used as articulators of views and ideological positions in the examined press discourse). The above would, effectively, allow creating a generally pre-normalising dynamics based on the assumption that while thew press in itself remained objective, there was a wider negativisation of social and political views on immigration that was “anyway” already in progress and commonplace – and hence the press could only reflect or report on them accordingly. Similarly, the frequent use of “mitigation” and “distantiation” (Reisigl and Wodak Citation2001) would also facilitate the press’ showing its allegedly detached stance while essentially mitigating its agency.

While we also find that the key factors encompassed by our various sub-hypotheses generally proved decisive for the trajectories of press discourse under analysis, it is vital that they were re/emerging not only diachronically but also periodically, and often created a cumulative rather than a steady or a linear effect. Hence, at first, our political-ideological-factor sub-hypothesis has found its confirmation in/via the salience of dynamics of public debates on immigration accelerating in the periods leading directly to, or immediately following, key national-parliamentary elections in the period 2010-2022. As has been shown above, namely, all of the election periods yielded significant peaks in press-discourses on immigration in Sweden with the pre- and post-election dynamics allowing for acceleration of political-ideological framings as well as of their recontextualisation between media, the political, and the wider public sphere.

In a similar vein, our second, i.e. contextual-factor sub-hypothesis – which highlighted the salience of other than strictly political developments – has also been confirmed. It proved that especially the 2015–2016 “Refugee Crisis” in Europe was particularly decisive for the dynamics of press reporting on immigration in Sweden in our period of investigation. As we have shown above, namely, the “Refugee Crisis” constituted the key “peak” of the Swedish press discourse on immigration throughout 2010–2022 and was in itself also a period when immigration-related arguments and debates in the press remained at an exceptionally high level for the longest period of time. More importantly, however, the 2015–2016 “Refugee Crisis” remained vital for the qualitative dynamics of the analysed Swedish press discourse on immigration. It emerged as the key point in the discursive shift central to our analysis and signalled the point during which – and from which onwards – the discourse on immigration in the Swedish press (and in the wider public sphere) would not only change its tone but also since when the deeper normalisation logic would also become ever more “naturalised” (Fairclogh Citation1992; Wodak Citation2011).

The combination of the above dynamics, then, would also lead to the confirmation of our third – i.e. imaginary-recontextualisation-factor sub-hypothesis – which interrogated the salience of other issues being used as strategic, discursive “proxies” (Ekström, Krzyżanowski, and Johnson Citation2023) for immigration. Such was the case with, in particular, public debates surrounding “criminality” evident in Sweden especially since ca. 2018 onwards. That discourse – along with its qualitative depth – could, it seems, only emerge in the post-Refugee-Crisis logic which opened up path-dependencies for wider pre-legitmising of social problems and issues by way of negative perception of selected social groups, also as token of politicisation and mediatisation of, in particular, immigration (Krzyżanowski, Triandafyllidou, and Wodak Citation2018). This, in turn, resulted in the peculiar, political and media “polyphony” or “heteroglossia” (Bakhtin Citation1981, Citation1984), i.e. a wider multiplicity of “voices” critical of immigration being voiced simultaneously and subsequently. This, as we showed elsewhere (Ekström, Krzyżanowski, and Johnson Citation2023), even led to the point when, as such, immigration would not be mentioned or thematised explicitly any longer while instead various “public implicatures” – such as those implying the anyway close connection between immigration and wider social problems such as, e.g. criminality – could be developed and recontextualised.

Indeed, a polyphony of sorts was also established in the examined press discourse wherein, as we have shown, multiple forms of agency would often be constructed to, in particular, mitigate and objectivise the press's own stance. However, this process was often ambivalent and ambiguous as well as combined with further dynamics and features identified in our in-depth, critical discourse analysis. For example, by way of framing immigration persitently as “them”, a de-agentification of migrants and immigration would progressively occur while thus allowing for thematising and legitimising – and in any case effectively bringing to the fore – the interests and rights of the “natives”. At the same time, normalising path-dependencies – of effectively denying xenophobia or exclusion or at least viewing it selectively in the wider society – would be given space as well as pre-legitimised, including via, e.g., wider social and political processes and dynamics (e.g. globalisation, modernisation, etc.). Thereby, the discourse dynamics would, it seems, not only recontextualise immigration-related stance from Swedish political discourse as such (Krzyżanowski Citation2018a) but also start closely resembling public narratives elsewhere in Europe and beyond wherever the far-right has long served as one of key sources of illiberal, exclusionary imagination (Krzyżanowski Citation2018b, Citation2020b; Krzyżanowski and Krzyżanowska Citation2022, 2024).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Michał Krzyżanowski

Michał Krzyżanowski is one of the leading international experts in critical discourse research of normalisation of the politics of exclusion and anti-immigration rhetoric in the context of far-right, illiberalism, and neoliberalism. He holds a Chair in Media and Communications at Uppsala University, Sweden, where he is also Deputy Head & Associate Head (Research) at Department/School of Informatics & Media as well as Director of Research at the Uppsala University Centre for Multidisciplinary Studies on Racism (CEMFOR). Info: https://www.katalog.uu.se/empinfo/?id=N20-1042.

Hugo Ekström

Hugo Ekström specialises in critical discourse analysis of mediated and political communication in the processes of mainstreaming of the far-right. Since 2023 he is a PhD Candidate in Media and Communications at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden, having previously studied and worked as a research assistant at Department of Informatics and Media, Uppsala University, Sweden. Info: https://www.gu.se/om-universitetet/hitta-person/hugoekstrom.

Notes

1 Abbreviations of Swedish political party names used throughout (in left-to-right order of political spectrum): Vänsterpartiet / The Left Party (V; socialist); Socialdemokraterna / Social-Democrats (S; social-democratic); Liberalerna/Liberals (L; Liberal-democratic); Moderaterna/Moderates (M; liberal-conservative); Kristdemokraterna / Christian-Democrats (KD; conservative); Sverigedemokraterna / Sweden Democrats (SD; far-right).

2 Translations of all Swedish examples are ours.

3 The term (SE: åsiktskorridoren) was coined by Ekengren-Oscarsson (Citation2013).

References

- Abiri, E. 2000. “The Changing Praxis of “Generosity”: Swedish Refugee Policy During the 1990s.” Journal of Refugee Studies 13 (1): 11–28.

- Akkerman, T. 2016. “Conclusion.” In Radical Right-Wing Populist Parties in Western Europe: Into the Mainstream, edited by T. Akkerman, S. L. de Lange, and M. Rooduijn, 278–282. London: Routledge.

- Andersson, L. M., and K. K. Geverts. 2008. “Inledning.” In En Problematisk Relation? Flytningspolitik och Judiska Flyktningar i Sverige 1920-1950, edited by L. M. Andersson, and K. K. Geverts, 7–31. Uppsala: Swedish Science Press.

- Asp, K. 1998. Flyktingrapporteringen i Rapport, JMG Granskaren 2/98. Göteborg: Göteborgs universitet.

- Asp, K. 2002. Integrationsbilder. Medier och allmänhet om integrationen. Norrköping: Integrationsverket.

- Backlund, A. 2023. “Government Formation and the Radical Right: A Swedish Exception?” Government and Opposition 58 (4): 882–898.

- Baker, P., C. Gabrielatos, M. KhosraviNik, M. Krzyżanowski, T. McEnery, and R. Wodak. 2008. “A Useful Methodological Synergy? Combining Critical Discourse Analysis and Corpus Linguistics to Examine Discourses of Refugees and Asylum Seekers in the UK Press.” Discourse & Society 19 (3): 273–306.

- Bakhtin, M. M. 1981. The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Bakhtin, M. M. 1984. Problems of Dostoevsky's Poetics. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Benson, R. 2013. Shaping Immigration News. Cambridge: CUP.

- Bernstein, B. 1990. The Structuring of Pedagogic Discourse. London: Routledge.

- Betz, H.-G. 1994. Radical Right-Wing Populism in Western Europe. New York: St. Martin's Press.

- Blomqvist, P., and J. Palme. 2020. “Universalism in Welfare Policy: The Swedish Case Beyond 1990.” Social Inclusion 8 (1): 114–123.

- Bolin, N., J. Hinnfors, and J. Strömbäck. 2016. “Invandring på ledarsidorna i svensk nationell dagspress 2010–2015.” In Migrationen i medierna: men det får en väl inte prata om, edited by L. Truedson, 192–211. Stockholm: Institutet för mediestudier.

- Breazu, P., and D. Machin. 2022. “Racism is Not Just Hate Speech: Ethnonationalist Victimhood in YouTube Comments About the Roma During Covid-19.” Language in Society 52 (3): 511–531.

- Breazu, P., and D. Machin. 2024. “Humanitarian Discourse as Racism Disclaimer: The Representation of Roma in Swedish Press.” Journal of Language & Politics. https://doi.org/10.1075/jlp.23044.bre.

- Brune, Y. 2004. Nyheter från gränsen. Tre studier i journalistik om “invandrare”, flyktingar och rasistiskt våld. Göteborg: JMG, Göteborgs universitet.

- Demker, M. 2015. “Mobilisering kring migration förändrar det svenska partisystemet.” In Fragment, edited by A. Bergström, B. Johansson, H. Oscarsson, and M. Oskarson, 261–272. Göteborg: SOM-Institutet.

- Demker, M. 2016. “De generösa svenskarna? En analys av attityder till invandring och invandrare i Sverige.” Norsk Statsvitenskapelig Tidskrift 32 (2): 186–196.

- Demker, M. 2023. Flyktning- oh Invsndringspolitiken under 1990-talet i väljarnas ögon. (Valforskningsprogrammet rapportserie 2024:4). Göteborg: GU Statsvetenskapliga institutionen.

- De Witte, H. 1996. “On the “Two Faces” of Right-Wing Extremism in Belgium: Confronting the Ideology of Extreme Right-Wing Parties in Belgium with the Attitudes and Motives of Their Voters.” Res Publica (Liverpool, England) 38 (2). https://doi.org/10.21825/rp.v38i2.18642.

- Ekengren Oscarsson, H. 2013. Väljare är inga dumbommar. Henrik Ekengren Oscarsson. Forskning om val, opinion och demokrati. https://ekengrenoscarsson.com/2013/12/10/valjare-ar-inga-dumbommar.

- Ekman, M. 2022. “The Great Replacement: Strategic Mainstreaming of far-Right Conspiracy Claims.” Convergence 28 (4): 1127–1143.

- Ekman, M., and M. Krzyżanowski. 2021. “A Populist Turn?: News Editorials and the Recent Discursive Shift on Immigration in Sweden.” Nordicom Review 42 (S1): 67–87.

- Ekström, H., M. Krzyżanowski, and D. Johnson. 2023. “Saying ‘Criminality’, Meaning ‘Immigration’? On the Role of ‘Proxy’ Discourses in Normalization of the Politics of Exclusion in Sweden.” Critical Discourse Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405904.2023.2282506.

- Fairclogh, N. 1992. Discourse and Social Change. Cambridge: Polity.

- Ghersetti, M., and T. Odén. 2018. Flyktingkrisen 2015. Mediernas bevakning och allmänhetens åsikter. Karlstad: Myndigheten för samhällsskydd och beredskap.

- Goldschmidt, T., and J. Rydgren. 2018. Social Distance, Immigrant Integration, and Welfare Chauvinism in Sweden. Discussion Paper SP VI 2018–102. Berlin: WZB Berlin Social Science Center.

- Hedman, L. 1985. “En explorativ studie av invandrarbilden i massmedia.” In Invandrare i tystnadsspiralen. Journalisten som verklighetens dramaturg, edited by L. Hedman, et al., 21–195. Stockholm: Arbetsmarknadsdepartementet.

- Hinnfors, J., A. Spehar, and G. Bucken-Knapp. 2012. “The Missing Factor: Why Social Democracy Can Lead to Restrictive Immigration Policy.” Journal of European Public Policy 19 (4): 585–603.

- Hultén, G. 2006. Främmande sidor: Främlingskap och nationell gemenskap i fyra svenska dagstidningar efter 1945. Stockholm: University of Stockholm, JMK.

- Kallis, A. 2021. “‘Counter-Spurt’ But Not ‘De-Civilization’: Fascism, (Un)Civility, Taboo, and the ‘Civilizing Process’.” Journal of Political Ideologies 26 (1): 3–22.

- Krzyżanowski, M. 2010. The Discursive Construction of European Identities. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.

- Krzyżanowski, M. 2013. “From Anti-Immigration and Nationalist Revisionism to Islamophobia: Continuities and Shifts in Recent Discourses and Patterns of Political Communication of the Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ).” In Right-Wing Populism in Europe: Politics and Discourse, edited by R. Wodak, et al., 135–148. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Krzyżanowski, M. 2014. “Values, Imaginaries and Templates of Journalistic Practice: A Critical Discourse Analysis.” Social Semiotics 24 (3): 345–365.

- Krzyżanowski, M. 2016. “Recontextualizations of Neoliberalism and the Increasingly Conceptual Nature of Discourse.” Discourse & Society 27 (3): 308–321.

- Krzyżanowski, M. 2018a. “‘We Are a Small Country That Has Done Enormously Lot’: The ‘Refugee Crisis’ & the Hybrid Discourse of Politicising Immigration in Sweden.” Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies 16 (1-2): 97–117.

- Krzyżanowski, M. 2018b. “Discursive Shifts in Ethno-Nationalist Politics: On Politicisation and Mediatisation of ‘Refugee Crisis’ in Poland.” Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies 16 (1-2).

- Krzyżanowski, M. 2020a. “Normalization and the Discursive Construction of ‘New’ Norms and ‘New’ Normality: Discourse in/and the Paradoxes of Populism and Neoliberalism.” Social Semiotics 30 (4): 431–448.

- Krzyżanowski, M. 2020b. “Discursive Shifts and the Normalisation of Racism: Imaginaries of Immigration, Moral Panics and the Discourse of Contemporary Right-Wing Populism.” Social Semiotics 30 (4): 503–527.

- Krzyżanowski, M., M. Ekman, P. E. Nilsson, M. Gardell, and C. Christensen. 2021. “Un-Civility, Racism and Populism: Discourses and Interactive Practices of Anti- & Post-Democratic Communication.” Nordicom Review 42: 3–15.

- Krzyżanowski, M., and M. Ekström. 2022. “The Normalisation of Far-Right Populism and Nativist Authoritarianism: Discursive Practices in Media.” Journalism and the wider Public Sphere/s. Discourse & Society 33 (6): 719–729.

- Krzyżanowski, M., and N. Krzyżanowska. 2022. “Narrating the ‘New Normal’ or Pre-Legitimising Media Control? COVID-19 and the Discursive Shifts in the Far-Right Imaginary of ‘Crisis’ as a Normalisation Strategy.” Discourse & Society 33 (6): 805–818.

- Krzyżanowski, M., and N. Krzyżanowska. 2024. . “Conceptual Flipsiding’ in/and Illiberal Imagination: Towards a Discourse-Conceptual Analysis.” The Journal of Illiberalism Studies 4 (2): 1–14. https://doi.org/10.53483/XCPS3572.

- Krzyżanowski, M., and P. Ledin. 2017. “Uncivility on the Web: Populism in/and the Borderline Discourses of Exclusion.” Journal of Language & Politics 16 (4): 566–581.

- Krzyżanowski, M., A. Triandafyllidou, and R. Wodak. 2018. “The Politicisation and Mediatisation of the ‘Refugee Crisis’ in Europe.” Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies 16 (1-2): 1–14.

- Krzyżanowski, M., and R. Wodak. 2009. The Politics of Exclusion: Debating Migration in Austria. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

- Krzyżanowski, M., R. Wodak, H. Bradby, M. Gardell, A. Kallis, N. Krzyżanowska, C. Mudde, and J. Rydgren. 2023. “Discourses and Practices of the ‘New Normal’: Towards an Interdisciplinary Research Agenda on Crisis and the Normalization of Anti- and Post-Democratic Action.” Journal of Language & Politics 22 (4): 415–437.

- Laruelle, M. 2022. “Illiberalism: A Conceptual Introduction.” East European Politics 38 (2): 303–327.

- Malinowski, B. 1920. “Classificatory Particles in the Language of Kiriwina.” Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies 1/4: 33–78.

- Milani, T. 2020. “No-go Zones in Sweden: The Infectious Communicability of Evil.” Language, Culture and Society 2 (1): 7–36.

- Moffitt, B. 2021. “How Do Mainstream Parties ‘Become’ Mainstream, and Pariah Parties ‘Become’ Pariahs? Conceptualizing the Processes of Mainstreaming and Pariahing in the Labelling of Political Parties.” Government and Opposition 1 (19): 385–403. https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2021.5.

- Mondon, A., and A. Winter. 2020. Reactionary Democracy: How Racism and the Populist Far Right Became Mainstream. London: Verso.

- Mudde, C. 2019. The Far-Right Today. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Nilsson, Å. 2004. SCB, Efterkrigstidens invandring och utvandring. Stockholm: Statistiska centralbyrån.

- Odmalm, P., and E. Hepburn. 2017. “Mainstream Parties, the Populist Radical Right, and the (Alleged) Lack of a Restrictive and Assimilationist Alternative.” In The European Mainstream and the Populist Radical Right, edited by P. Odmalm, and E. Hepburn, 1–27. London: Routledge.

- Orvesto. 2011. Orvesto Konsument Helår 2010. Stockholm: Kantar Sifo.

- Orvesto. 2015. Orvesto Konsument 2014: Helår. Stockholm: Kantar Sifo.

- Orvesto. 2019. Räckviddsrapport, Orvesto Konsument 2018 Helår. Stockholm: Kantar Sifo.

- Orvesto. 2022. Räckviddsrapport, Orvesto Konsument 2022:2. Stockholm: Kantar Sifo.

- Östberg, K., and J. Andersson. 2013. Sveriges Historia 1965-2012. Stockholm: Norstedts.

- Pietikäinen, S., and H. Dufva. 2006. “Voices in Discourses: Dialogism, Critical Discourse Analysis and Ethnic Identity.” Journal of Sociolinguistics 10: 205–224.

- Reisigl, M., and R. Wodak. 2001. Discourse and Discrimination: Rhetorics of Racism and Anti-Semitism. London: Routledge.

- Rydgren, J. 2002. “Radical Right Populism in Sweden: Still a Failure, But for How Long?” Scandinavian Political Studies 25 (1): 27–56. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9477.00062.

- Rydgren, J. 2006. Tax Populism to Ethnic Nationalism. Radical Right-Wing Populism in Sweden. New York: Berghahn Books.

- Rydgren, J., and S. van der Meiden. 2019. “The Radical Right and the end of Swedish Exceptionalism.” European Political Science 18: 439–455. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-018-0159-6.

- Sarnecki, J. 2021. Immigration and Crime Development at the National and Municipal Levels. Stockholm: Institute for Future Studies. https://www.iffs.se/kalendarium/iffs-play/jerzy-sarnecki-immigration-and-crime-development-at-the-national-and-municipal-levels.

- Scarpa, S., and C. Schierup. 2018. “Who Undermines the Welfare State? Austerity-Dogmatism and the U-Turn in Swedish Asylum Policy.” Social Inclusion 6 (1): 199–207.

- Schierup, C.-U., and A. Ålund. 2011. “The end of Swedish Exceptionalism? Citizenship, Neoliberalism and the Politics of Exclusion.” Race & Class 53 (1): 45–64.

- Senft, G. 1995. “Phatic Communion.” In Handbook of Pragmatics Online, Volume 1. https://doi.org/10.1075/hop.1.pha1.

- SOU. 2006. SOU 2006:21. Mediernas vi och dom: Mediernas betydelse för den trukturella Diskrimineringen: Rapport. Stockholm: Fritze. https://www.regeringen.se/contentassets/976435886ee54a6ebda2f149522e9395/mediernas-vi-och-dom—mediernas-betydelse-for-den-strukturella-diskrimineringen/.

- SOU. 2007. SOU 2007:102, Svenska nyhetsmedier och mänskliga rättigheter i Sverige: En översikt: Rapport nr 1. Stockholm: Fritze. https://www.regeringen.se/contentassets/3fb20cbaffa9473e8c64a49309157087/svenska-nyhetsmedier-och-manskliga-rattigheter-i-sverige-sou-2007102/.

- SOU. 2012. SOU 2012:74, Främlingsfienden inom oss: Betänkande. Stockholm: Fritze. https://www.regeringen.se/contentassets/59ee0dc5b7dd4411b66e0c51adcdf75b/framlingsfienden-inom-oss-sou-201274/.

- Strömbäck, J., F. Andersson, and E. Nedlund. 2017. Invandring i medierna – Hur rapporterade svenska tidningar åren 2010-2015? Delmi rapport: 2017:6. Stockholm: Delegationen för migrationsstudier.

- Theorin, N., and J. Strömbäck. 2020. “Some Media Matter More Than Others: Investigating Media Effects on Attitudes Toward and Perceptions of Immigration in Sweden.” International Migration Review 54 (4): 1238–1264.

- van Dijk, T. A. 1991. Racism and the Press. London: Routledge.

- van Dijk, T. A. 1992. “Discourse and the Denial of Racism.” Discourse and Society 3 (1): 87–118.

- van Leeuven, T. 2007. “Legitimation in Discourse and Communication.” Discourse & Communication 1 (1): 91–112. https://doi.org/10.1177/1750481307071986.

- van Leeuwen, T. 2008. Discourse as Practice. Cambridge: CUP.

- van Leeuwen, T., and R. Wodak. 1999. “Legitimizing Immigration Control: A Discourse-Historical Analysis.” Discourse Studies 1 (1): 83–118.

- Wildros, C. 2017. The Evolution of Attitudes Toward Immigration in Sweden. Uppsala: Uppsala University / Department of Government.

- Wodak, R. 2003. “Populist Discourses: The Rhetoric of Exclusion in Written Genres.” Document Design 4 (2): 132–148.

- Wodak, R. 2011. “Critical Linguistics and Critical Discourse Analysis.” In Discursive Pragmatics, edited by J. Zienkowski, J.-O. Östman, and J. Verschueren, 50–70. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Wodak, R. 2015. The Politics of Fear: What Right-Wing Populist Discourses Mean. London: Sage.

- Wodak, R. 2021. The Politics of Fear: Shameless Normalization of Far-Right Discourse. London: Sage.