ABSTRACT

How did many Australians come to accept that competition, rather than cooperation, with China was necessary in the Pacific Islands? We use discourse analysis techniques to examine the role that framings in Australian official discourse, media, and commentary over the last decade (2011–2021) played in constructing China’s presence in the region as threatening such that many Australians have accepted that policies aimed at competing with China are the most reasonable foreign and strategic policy response. We find that Australian official discourse was characterised by qualified optimism about China’s role until 2018, when a more explicit emphasis on competition emerged. Echoing this shift, while the media and (much of) the commentary framed China’s role in terms of threat and competition throughout the decade, this framing increased significantly in 2018. It is impossible to isolate the Australian government’s policy approach to China in the Pacific Islands from its broader understanding of China’s increasingly activist role in Australia, the Indo-Pacific, and globally. But our findings suggest that, by consistently framing China in terms of threat and competition, the media and – to a lesser extent, commentary – created an enabling environment for the public to accept changes to the Australian government’s policies.

Introduction

In 2014 then Australian Foreign Minister Julie Bishop (Citation2014a) urged Australia to cooperate with China in the Pacific Islands, commenting that: ‘We should be engaging China for not only is it a growing presence in our region, but we should be doing what we can to capitalise on our respective strengths, using our combined weight to bear overcoming [sic] some of the development challenges of the Pacific’. Reflecting this cooperative approach, in 2015 Australia agreed to a Trilateral Malaria Project with China and Papua New Guinea (PNG). Yet only three years later, in April 2018, Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull expressed alarm about rumours that China was establishing a military base in Vanuatu, declaring that: ‘We would view with great concern the establishment of any foreign military bases in those Pacific Island countries and neighbours of ours’ (quoted in Pacific Beat Citation2018a). A few months later, Bishop stated that Australia’s approach to China’s investment in the Pacific Islands would be both ‘complementary in the sense that we recognise that there’s a need for infrastructure investment in the Pacific and we’re encouraging it, competitive in the sense that we want people to have options’ (quoted in Wroe Citation2018e). In November 2018, Australia announced a substantial policy ‘step-up’ to improve its relationships and increase its investments in the region (Morrison Citation2018a), a move widely interpreted as an attempt to compete with China for influence in the region.

How did many Australians come to accept the government’s policy switch towards competition, rather than cooperation, with China in the Pacific Islands? In this article, we use discourse analysis techniques to examine the role that framings in Australian official discourse, media, and commentary over the last decade (2011–2021) played in constructing China’s presence in the Pacific Islands as threatening such that many Australians accepted that competition was the most reasonable foreign and strategic policy response.

After first outlining our analytical framework, we provide background on China’s evolving presence in the Pacific Islands and Australia’s regional policies between 2011–2021. We then review the academic literature to justify our identification of three dominant ‘frames’ that have been used to characterise China’s presence in the Pacific Islands – opportunity, neutral, and threat – and analyse our data against these frames. We conclude that Australian official discourse was characterised by qualified optimism about China’s role in the region until 2018, when a more explicit emphasis on competition emerged. In contrast, the media and (much of) the commentary framed China’s role in the Pacific Islands in terms of threat and competition throughout the decade, although this increased significantly in 2018 in line with changes in the official discourse and developments in the region. It is impossible to isolate the Australian government’s policy approach to China in the Pacific Islands from its broader understanding of China’s increasingly activist role in Australia, the Indo-Pacific, and globally. But our findings suggest that, by consistently framing China in terms of threat and competition, the media and – to a lesser extent, commentary – helped to socially construct China as a potential threat and competitor in the Pacific and created an enabling environment for the public to accept changes to the Australian government’s policies.

Analytical framework

We have been guided by Roxanne Doty’s (Citation1993, 298) concept of ‘how-possible’ questions that ‘examine how meanings are produced and attached to various social subjects/objects, thus constituting particular interpretive dispositions which create possibilities and preclude others’. Like Doty, we used discourse analysis techniques to analyse how knowledge is produced and reproduced through discourse, ‘the representational practices through which meanings are generated’ (Dunn and Neumann Citation2016, 2). What distinguishes a discourse analysis approach from one focused primarily on presupposed subjects (such as states) and material facts (such as the relative size of aid budgets, military deployments, or diplomatic engagements) is that it holds that discourse has the power to constitute subjects and the meaning of material facts. Discourse uses concepts, metaphors, analogies, and frames to construct ‘particular subject identities, positioning these subjects vis-à-vis one another and thereby construct … a particular “reality” in which this policy becomes possible, as well as a larger “reality” in which future policies would be justified in advance’ (Doty Citation1993, 304–305). Therefore, discourse analysis can reveal how Australian leaders, policymakers, and commentators understood China’s role in the Pacific Islands and how this created an enabling environment for the Australian public to accept government’s foreign and strategic policies. Indeed, the media and commentary can play ‘a key role in explaining and engaging with international affairs in a way that makes sense of foreign policy for citizens and localises international politics’ (Davis and Brookes Citation2016, 54; Robinson Citation2001).

Our analysis focused on the dominant frames used to depict China’s presence in the Pacific Islands in Australian official discourse, media, and commentary. The process of framing involves ‘select[ing] some aspects of a perceived reality and mak[ing] them more salient in a communicating text, in such a way as to promote a particular problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and/or treatment recommendation for the item described’ (Entman Citation1993, 52). Framing is important because human minds filter inputs to help identify concepts worth processing and to organise their thinking about complex issues; common filters include stereotypes, biases, and heuristics (Hudson and Day Citation2019). Yet these frames typically exist in the background, without us noticing how they influence our thinking. This highlights the mechanism of presupposition, by which discourses create ‘background knowledge and in doing so construct … a particular kind of world in which certain things are recognised as true’ (Doty Citation1993, 306). Discourse also attaches labels to subjects so certain qualities are linked to ‘particular subjects through the use of predicates and the adverbs and adjectives that modify them’ (Doty Citation1993, 306). The quality, attribute, or property of a subject is ‘important for constructing identities for those subjects and for telling us what subjects can do’ (Doty Citation1993, 306).

Noting the concept of intertextuality, that is, that ‘texts always refer back to other texts which themselves refer to still other texts’ (Doty Citation1993, 302), we analysed representations of China’s presence in the Pacific Islands in Australian public discourse over the last decade (2011–2021). We limited our analysis to the last ten years for pragmatic reasons, given the quantum of potential data, and because we anticipated there would be an increase in both coverage and threat framing in 2018, given that was when reports of attempts by China to establish military bases in the region began. The significant nature of this increase would be demonstrated by analysing the preceding seven years. We defined public discourse as including official discourse (public statements and policies adopted by the government in the form of official communications, e.g. government documents, speeches, and statements), and Australian and international media and commentary. Overall, we analysed 673 separate sources. We also analysed academic texts over the last two decades to identify our three analytical frames.

We analysed media reports from major Australian media outlets with large audiences and a focus on international affairs: The Australian, Sydney Morning Herald, The Age, The Guardian, Australian Financial Review, Australian Associated Press, and the Australian Broadcasting Corporation. We analysed media reports from major international media outlets that cover international affairs, particularly Australia and the Pacific Islands region: New York Times, Washington Post, Agence France Press, Reuters, CNN, BBC, NPR, and Financial Times. We analysed commentary from major Australian think tanks and relevant university research centres: The Interpreter (Lowy Institute), The Strategist (Australian Strategic Policy Institute), Australian Outlook (Australian Institute of International Affairs), East Asia Forum (Crawford School at the Australian National University), and DevPolicy (Development Policy Centre at the Australian National University). We also analysed commentary from major international think tanks and blogsites known to cover Australia and the Pacific Islands region: Centre for Strategic and International Studies, Chatham House, Pacific Forum, East West Center, RAND Corporation, and The Diplomat. We included media and commentary sources as the ‘discourse(s) instantiated in these various documents produce meanings and in doing so actively construct the “reality” upon which foreign policy is based’ (Doty Citation1993, 303). These sources also facilitate the reception and influence the meaning of official discourse by shaping the ‘general system of representation in a given society’ (Doty Citation1993, 303). This is important because to be taken seriously, official discourse ‘must make sense and fit with what the general public takes as “reality”’ (Doty Citation1993, 303).

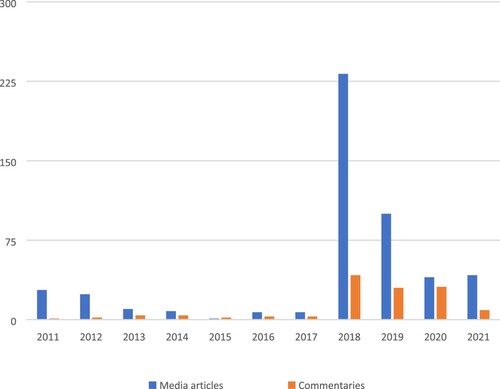

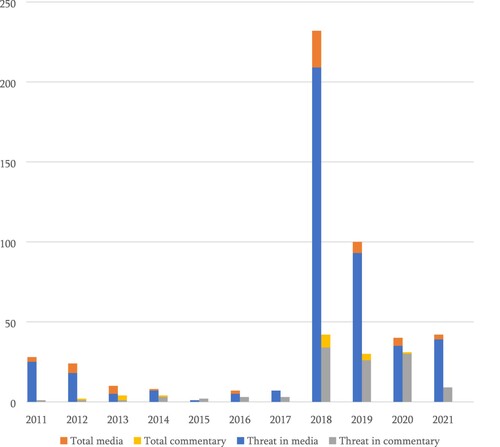

To identify media reports for analysis we searched the Factiva database, using the search terms ‘Beijing’ or ‘China*’ and ‘Pacific Island*’ or ‘Pacific state* or ‘Pacific nation*’. To identify commentary, we searched the online archive of each blog for sources relating to China and the Pacific Islands. Overall, we identified 499 media articles and 131 commentaries. Notably, there was a spike in both media articles and commentaries in 2018, with the distribution over time illustrated in .

Given our large dataset, we first analysed sources by skim reading to code each against our three frames (some sources were coded against multiple frames). We then extracted the relevant parts of each source into a table and analysed the specific language used, focusing on the processes of subject position, presupposition, and predication. Conscious of intertextuality, we identified when sources referred to each other (explicitly, or implicitly, such as sharing the same language). Finally, we mapped the frequency in which China and the Pacific Islands were mentioned across the media, commentary, and official discourse over time.

China’s evolving presence in the Pacific Islands, 2011–2021

China slowly built a diplomatic and economic presence in the Pacific Islands from the 1970s in the context of competing with Taiwan for diplomatic recognition. By 2011 that competition had cooled, and Taipei and Beijing tacitly agreed to stop competing in 2008. Competition restarted after Taiwan’s 2016 election. Beijing persuaded Solomon Islands and Kiribati to switch their recognition to China in September 2019, reducing the number of Pacific states that have diplomatic relations with Taiwan to four.

During the decade 2011–2021, China’s interests in the Pacific Islands developed a strategic edge. In April 2018, it was reported that China was in talks to build a ‘military base’ in Vanuatu, although both governments denied this. In September 2019, a Chinese company sought to lease Tulagi Island, home to a former Japanese naval base, in Solomon Islands. The Solomon Islands government vetoed the lease, which had been agreed by the provincial authorities. Kiribati’s switch back to recognising China may see the satellite-tracking station China had built there in 1997 updated and returned to operation; it had been mothballed when Kiribati recognised Taiwan in 2003.

China’s economic presence in the region also grew over the decade. State-owned corporations undertook major logging projects and developed fisheries, as well as the Ramu and Frieda River mines in PNG. Nine Pacific states signed up to the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI),Footnote1 which has seen China invest in infrastructure construction around the world, especially potential ‘dual use’ ports. This led to claims that China was engaged in ‘debt-trap diplomacy’, using lending to pursue the strategic objective of securing military access (Parker and Chefitz Citation2018). As there are questions about the sustainability of much of the debt taken on by Pacific states, there are concerns that they may be particularly susceptible to such influence (Rajah, Dayant, and Pryke Citation2019). But whether aid, loans, and the BRI are primarily aimed at strategic, rather than economic, ends remains unclear. Indeed, Fox and Dornan (Citation2018) observed that, while almost half of Pacific states were classified by the IMF and Asian Development Bank as being at high risk of debt distress, and China was the region’s largest bilateral lender (holding approximately 12% of all regional debt), except for Tonga, China’s lending comprised less than half of the total to any one Pacific state. And although China’s aid increased in the last decade, it was still dwarfed by Australia’s contribution, and Beijing’s aid has declined in real terms since 2019: committing US$290 m in 2018, US$1bn in 2019, but only US$4.2 m in 2020 (Lowy Institute Citation2020).Footnote2

Australia’s Pacific Islands policy, 2011–2021

Australia began 2011 under the leadership of a Labor government that sought to reframe Australia’s engagement in the Pacific Islands as a ‘new era of cooperation’ and ‘partnership’ in then Prime Minister Kevin Rudd’s (Citation2008) ‘Port Moresby Declaration’. The Coalition government continued this framing after coming to power in 2013. Despite their rhetorical emphasis on the region, neither government implemented a broad-ranging regional policy agenda.

The Australian government’s approach changed at the 2017 Pacific Islands Forum leaders’ meeting, when then Prime Minister Turnbull committed Australia to ‘step-change’ its engagement (PM&C Citation2017). In 2018 Prime Minister Scott Morrison (Citation2018a) said this ‘Pacific step-up’ would include initiatives focused on enhancing development, security, diplomatic, and people-to-people links. This built on Australia’s provision of approximately half of all development aid to the region (Lowy Institute Citation2020). A dedicated cross-agency Office of the Pacific was created in 2019 to oversee implementation. Notably, apparently to counter BRI lending, Australia created a A$2 billion Australian Infrastructure Financing Facility for the Pacific and allocated an extra A$1bn to its Export Finance and Insurance Corporation to support investment. It also committed funding to major infrastructure projects, including the PNG Electrification Partnership and the Coral Sea Cable, and to redevelop the Republic of Fiji Military Forces’ Blackrock Camp. The latter two projects were reportedly direct counters to offers by China. As part of the security aspects of the Pacific step-up, Australia created the Australia Pacific Security College, Pacific Fusion Centre, committed to maintain a larger military presence, including through an upgraded Pacific Maritime Security Program, and to redevelop the Lombrum Naval Base on Manus Island, PNG. Australia agreed on a security treaty with Solomon Islands in 2017, a vuvale (friendship) partnership with Fiji in 2019, and a comprehensive strategic and economic partnership with PNG in 2020. In June 2018 Australia and Vanuatu began negotiations on a bilateral security treaty.

China as an ‘opportunity’

The first frame we identified from the academic literature positioned China as a potential partner for Australia, with its presence in the Pacific Islands presented as an opportunity for cooperation, particularly on aid projects (D’Arcy Citation2007; Dornan and Brant Citation2014; Powles Citation2007; Wallis Citation2017a; Wallis Citation2017b). Other proposed forms of cooperation included trade and investment liberalisation (Shiming Citation2019), policy dialogues, and military exercises, exchanges, and training (Connolly Citation2016; Zhang Citation2017a, Citation2017b, Citation2020a).

Until 2018, Australian official discourse about China’s presence in the Pacific Islands generally followed its broader approach of seeking to balance its economic and security interests while avoiding explicitly characterising China as threatening. The opportunity frame dominated Australian official discourse from 2011-2019, appearing in 28 of our 31 identified sources during that period. However, this optimism was qualified, with cooperation often presented as a method of influencing China’s behaviour. For example, in 2011, when he was Foreign Minister, Kevin Rudd argued that Australia should ‘find a way of working with China that’s constructive, that hopefully encourages them to adopt some of the norms around transparency, accountability and predictability’ (quoted in Gartrell Citation2011). Parliamentary Secretary for Pacific Island Affairs Richard Marles said in 2012 that Australia ‘did not see Chinese aid projects initiated so far as being linked to its political objectives’, but observed that ‘we just like to be doing it together in a co-ordinated way’ (quoted in Wallace Citation2012). In April 2013 Prime Minister Julia Gillard (Citation2013a) said that Australia wanted ‘to see countries around the world working for aid and development in the Pacific … we think that there are ways of working together’. During a visit to China, Gillard signed a development cooperation partnership between Australia and China.

In 2013 caution about cooperation with China became more explicit. In May 2013, when discussing the new Defence White Paper, Gillard (Citation2013d) stressed that it was intended to ‘bolster habits of cooperation’, although aware of the ‘risks’ in the ‘changing strategic order’. The White Paper recognised that ‘the growing reach and influence of Asian nations opens up a wider range of external players for our neighbours to partner with’ (DoD Citation2013, 15), but argued that ‘Australia welcomes China’s rise’ and ‘does not approach China as an adversary’ (DoD Citation2013, 9, 11). It flagged the ‘Australia-China Defence Engagement Action Plan’ as providing scope for enhanced ‘maritime engagement, peacekeeping cooperation, humanitarian assistance and disaster relief engagement’ (DoD Citation2013, 62).

As shadow minister from 2011–2013, and from 2013–2018 as Minister for Foreign Affairs in the Coalition government, Bishop also identified the potential for developing ‘joint venture’ development projects with China (quoted in Minus Citation2011). Like her Labor predecessors, Bishop presented cooperation as allowing Australia to ‘influence the priorities of infrastructure decisions and the transparency around how aid is delivered’ (quoted in Flitton Citation2011) and to ‘capitalise on our respective strengths’ (Bishop Citation2014b).

Bishop’s position was in lockstep with her government’s efforts to position China as a potential partner. The Defence Issues Paper 2014 described Australia’s ‘surprisingly close and effective defence relationship with China’ and foreshadowed ‘opportunities for increased practical military-to-military contact’ (DoD Citation2014, 18). In November 2014 Australia agreed to elevate the relationship to a ‘comprehensive strategic partnership,’ and then Prime Minister Tony Abbott (Citation2014) reported, during a press conference with China’s President Xi Jinping, that ‘our two sides have agreed to reinforce our coordination and communication within multilateral mechanisms including … the Pacific Islands Forum’. In 2016, when visiting China, Bishop (Citation2016) mentioned ‘the opportunities that I see in Australia and China carrying out more joint aid and development projects in the Pacific’.

In 2018, as concern about China’s presence – particularly lending – in the region began to mount, the official discourse began to include more warnings about the potential consequences of China’s behaviour. In August 2018, then Prime Minister Turnbull (Citation2018) said that Australia wanted to ‘work with China … in the Pacific to ensure that our respective engagement, including lending, reinforces our common goals of supporting the sustainable economic development, freedom and wellbeing of the people and nations of the Pacific’. In August 2018 Bishop commented: ‘we welcome the role played by all donors, including China, to support development in the Pacific’, but that it was important they ‘don’t impose onerous debt burdens on regional governments’ (quoted in Lyons Citation2018a). After taking office in August 2018, Prime Minister Morrison (Citation2018b) commented: ‘we want to continue working with others … such as China – to ensure our engagement strengthens the common goal of enhancing sustainable development and the wellbeing of our Pacific friends’.

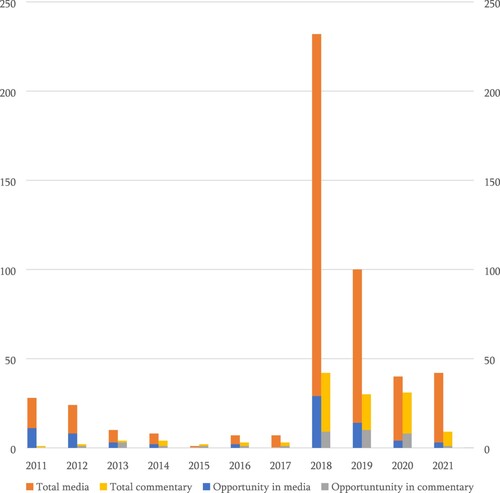

Despite its prevalence in official discourse, as illustrates, the opportunity frame was infrequently adopted in the media and commentary, although it was present proportionately more frequently in the commentary than media.

When it adopted the opportunity frame, the media and commentary argued that China’s interest in the Pacific Islands could be seen as a ‘positive development rather than a challenge, insofar as it creates opportunities for greater cooperation’ (O’Keefe Citation2013), ‘rather than building any new security or diplomatic arrangements designed to compete with it’ (Hayward-Jones Citation2013; Hanson and Fifita Citation2011; Wallis Citation2017a), with trilateral cooperation on aid projects identified as offering a ‘low risk opportunity’ (Claxton Citation2013; Smith Citation2012; Zhang Citation2016; Zhang Citation2019a), notwithstanding the differences in approach (Moyle and Dayant Citation2018).

China as ‘neutral’ Pacific presence

The second frame we identified positioned China as a ‘neutral’ presence in the Pacific Islands. This frame is based on scholarship which did not presuppose that China was inherently threatening. It instead argued that the Pacific Islands region was ‘marginal in China’s strategic landscape’ (Yang Citation2009, 145) and that ‘China’s objectives are ultimately domestic in nature’ and consequently there was ‘no well-coordinated grand strategy behind China’s presence in the region’ (Pan, Clarke, and Loy-Wilson Citation2019, 389-390). China’s approach to the region was said to mirror its actions in other developing countries (Wesley-Smith Citation2013; Zhang Citation2007), to be driven by economic interests (Hannan and Firth Citation2015; Zhang Citation2021), diplomatic competition with Taiwan, support in international fora, and a desire to build its image as ‘a benign, responsible global power’ (Zhang and Lawson Citation2017, 200-201; Atkinson Citation2010; Fletcher and Yeophantong Citation2019; Zhang and Shivakumar Citation2017). Indeed, China’s presence in the Pacific Islands was said to have grown ‘more by accident than by design’, after Fiji adopted a ‘Look North’ policy following its 2006 coup (Wallis Citation2017a, 202). China was characterised as having a comparatively ‘small footprint’ in the region, ‘few diplomats, no permanent military presence and relatively limited aid, trade and investment in comparison to other regions’ (Smith Citation2015, 1), and to lag behind Australia, the US, and New Zealand ‘in important ways’ (Zhang Citation2020b). Therefore, scholars concluded that ‘the geostrategic threat posed by China’s presence in the Pacific should not be exaggerated’ (Fletcher and Yeophantong Citation2019, 22; Wesley-Smith and Smith Citation2021; Zhou Citation2021). Even if, ‘in the event of armed conflict, more direct action cannot be ruled out if Beijing regards key strategic interests to be at stake’ (Wesley-Smith and Smith Citation2021, 21), scholars argued that this was ‘far from certain and it would be a strategic miscalculation to hasten this possible future through Cold War style framing’ (O’Keefe Citation2020, 96).

We coded only two pieces of our 45 identified sources of official discourse against the neutral frame, both being statements by Prime Minister Morrison (Citation2019a, Citation2019b) recognising China’s growth changed its international role.

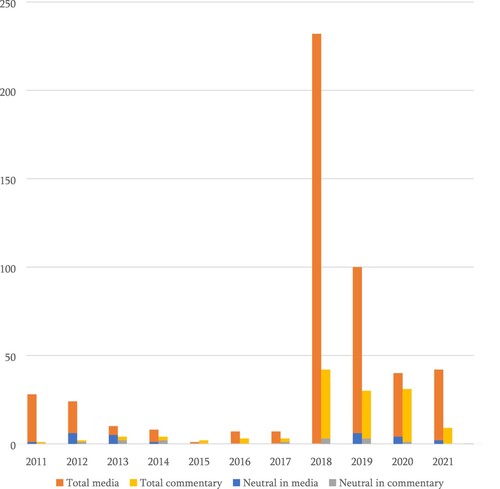

As illustrated in , relatively few media and commentary pieces adopted the neutral frame. Early in the decade there was some agreement with the academic literature that there was ‘little evidence that China is doing anything more than supporting its commercial interests and pursuing South-South cooperation’, particularly as ‘China has not yet sought to project hard power into the Pacific Islands’ (Hayward-Jones Citation2013; Claxton Citation2013). Indeed, one media report observed that ‘self-fulfilling prophecies’ of competition with China ‘can yet be avoided’ (Levine Citation2012). While the media dropped the neutral frame from 2015, commentary continued to argue that the region ‘isn’t strategically important to China, it isn’t high-priority’ (Safi Citation2015). Therefore, Australia’s concern was said to be ‘premature’, with China’s presence in the region not driven by strategic competition, but instead by its ‘much larger ‘Going Out’ strategy to expand China’s outreach to the developing world’ (Zhang Citation2016; Baker Citation2018). While the neutral frame became less common as the decade wore on, in 2018 commentators sought to debunk the ‘debt-trap diplomacy’ idea, arguing that it was a ‘far stretch’ (Fox and Dornan Citation2018), particularly as ‘Beijing actually operates in the region under a number of constraints’ (Zhang Citation2019b). In 2019 commentary therefore argued that Australia should not be concerned about Solomon Islands and Kiribati switching their diplomatic recognition to China, as ‘having China as a diplomatic partner will not profoundly change either country’s economic or social challenges’ (Pryke Citation2019).

China as a ‘threat’

The third frame we identified from the academic literature was of China as a ‘threat’. This frame was prominent in the 2000s, and presupposed that, as a rising power, China was a potential competitor to Australia and its partners. Scholars argued that China could encourage Pacific states to shift their allegiance away from their traditional partners (Crocombe Citation2007), that China could test its strategic power against the US in the region (Dobell Citation2007; Henderson and Reilly Citation2003; Shie Citation2010; Windybank Citation2005) and that China’s increased presence had ‘accelerated the erosion of the United States as a unipolar power’ (Lanteigne Citation2012, 23). Little academic literature after 2013 explicitly adopted a threat frame despite China emerging as a great power. Instead, there was caution that China’s presence could result in ‘accidental friction’ with Australia and its partners, such as if China sent its army to evacuate its citizens (Connolly Citation2016, 491), and that China’s aid and concessional loans could fuel corruption and instability in the region, posing a security risk to Australia (Wallis Citation2017a).

Two pieces of academic work at the end of the decade explicitly adopted the threat frame. In 2020 it was argued that Chinese ‘influence and interference’ in the Pacific Islands was ‘quite brazen’, with the BRI characterised as a tool of China’s ‘grand strategy’ (Connolly Citation2020, 42). This interpretation was supported in 2021 by Chinese scholars who argued that, while China had economic and diplomatic interests, it also had a geopolitical objective: ‘to counterattack the perceived US containment of China by opening up a “new battlefield” for political influence and economic competition in the South Pacific’ and ‘ensure China’s rise at the systemic (global) level’ (Lei and Sui Citation2022, 83).

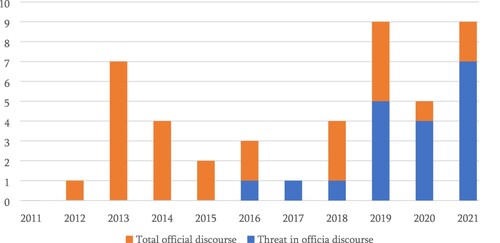

While the official discourse overwhelmingly used the opportunity frame until 2018, in 2019 the threat frame became more common, as illustrated in .

The 2016 Defence White Paper implicitly expressed concern about China’s increasing presence in the Pacific Islands. It observed that China would ‘continue to seek greater influence’ and, while hopeful that China had ‘greater capacity to share the responsibility of supporting regional and global security,’ also warned that ‘it will be important for regional stability that China provides reassurance to its neighbours by being more transparent about its defence policies’ (DoD Citation2016, 42). The 2017 Foreign Policy White Paper observed that ‘increasing competition for influence and economic opportunities in Papua New Guinea, other Pacific countries and Timor-Leste, as well as growing aid and loans from other sources, means they can turn elsewhere for advice and assistance’ (DFAT Citation2017, 100). Without naming China, it cautioned that aid and loans have ‘the potential to strain the capacity of countries to absorb assistance and manage their debt levels’ (DFAT Citation2017, 100).

2018 saw Australia’s official discourse begin to frame China’s presence as more explicitly threatening. In January 2018, then Minister for International Development and the Pacific Concetta Fierravanti-Wells expressed concern about China constructing ‘useless buildings’ and leaving Pacific states with ‘unsustainable’ debt burdens (quoted in Graue and Dziedzic Citation2018). In a line that became infamous for China’s response (Jingye Citation2018), Fierravanti-Wells commented that, in comparison to China, Australia did not ‘want to build a road that doesn’t go anywhere’ (quoted in Pacific Beat Citation2018b). Instead, she argued that Australia wanted to ‘ensure that the infrastructure that you do build is actually productive and actually going to give some … benefit’ (quoted in Pacific Beat Citation2018b). Then Foreign Minister Bishop quickly watered-down Fierravanti-Wells’s comments, saying that ‘Australia works with a wide range of development partners, including China’ (quoted in Remeikis Citation2018). Nevertheless, Fierravanti-Wells’s comments were frequently referenced in subsequent media reports (26 reports) and commentary (three sources), with commentator Graeme Dobell arguing that ‘Fierravanti-Wells is only guilty of voicing in more pointed language the fears expressed diplomatically in our foreign policy white paper’ (Dobell Citation2018a). Bishop also began to harden her language about China’s lending later in 2018, arguing that it might be ‘detrimental to their long-term sovereignty if they were ‘trapped into unsustainable debt outcomes’ (quoted in Wroe Citation2018f).

Official discourse began to explicitly name China as a potential threat in 2020, with the Defence Strategic Update stating that:

Since 2016, major powers have become more assertive in advancing their strategic preferences and seeking to exert influence, including China’s active pursuit of greater influence in the Indo-Pacific. Australia is concerned by the potential for actions, such as the establishment of military bases, which could undermine stability in the Indo-Pacific and our immediate region (DoD Citation2020, 11).

The threat framing dominated media reports every year of the decade analysed, except 2015, as illustrated in . However, there were proportionately fewer references to threat between 2011 and 2017, reflecting that there were relatively few mentions of China’s role in the Pacific in the Australian media and commentary during that period. The threat framing increased significantly in 2018, as did media and commentary coverage.

The primary claim used to support the threat framing in the media and commentary from 2011–2021 was that China’s increased presence in the Pacific Islands had led to growth in its ‘influence’ (Jennings Citation2016; Brunnstrom and Martina Citation2021; Callick and Bodey Citation2014; Flitton Citation2014; Sheridan Citation2014). Indeed ‘influence’ was a ‘floating signifier’ (Laclau Citation2005, 131) in the media and commentary that acquired a pejorative meaning to characterise the nature of China’s perceived threat. Many tools of Chinese statecraft were identified as assumed sources of influence, including ‘no strings’ and ‘soft’ loans (ABC News Citation2011; Colton Citation2018; Coorey Citation2012; Doherty Citation2018; Flitton Citation2012; Gartrell Citation2011; Oakes Citation2011a; Pacific Beat Citation2017b), ‘chequebook diplomacy’ (Brien Citation2012; Wallis Citation2012), ‘debt-trap diplomacy’ (Wroe Citation2018d; Davidson Citation2018; Kehoe, Tillett, and Coorey Citation2018), Chinese corporations (Pacific Beat Citation2017a; Wroe Citation2017), growing diplomatic footprint, ‘illegal Chinese immigrants’, ‘organised crime’ (Herr and Bergin Citation2011), and training and scholarships (Zhang Citation2016). But seldom did the media or commentary identify direct causality between these tools and changes in the behaviour of Pacific states that generated substantive strategic gains for China.

From 2016 the media and commentary began to focus on China’s potential strategic interests, warning that ‘building stronger relationships with Pacific Island nations is paramount for China to be able to project power through the Pacific Oceans’ and could ‘lay the groundwork for future hegemony’ (Wyeth Citation2016). There was also concern about China’s assumed strategic interests in monitoring and surveillance (Kenderdine Citation2017; Meick, Ker, and Chan Citation2018). But it was the April 2018 media reports claiming that the wharf China had funded in Vanuatu was ‘trojan horse operation’ and would be turned into a military base (Wroe Citation2018b), which ‘could see the rising superpower sail warships on Australia’s doorstep’ (Wroe Citation2018a) that triggered a flood of discussion about China’s strategic intentions – with 28 reports in the first week alone. This was despite both the Vanuatu and Chinese governments immediately denying the claim. Consequently, from 2018 references to ‘China’s strategic ambitions’ (Wroe Citation2018g) or ‘strategic threat’ (Dobell Citation2018c; Hayward-Jones Citation2018) became frequent. This characterisation reflected an assumption that the Pacific Islands were a ‘hotly contested geopolitical space’ (Dayant and Pryke Citation2018; Mudaliar Citation2018) that ‘Australia can lead or lose’ (Jennings Citation2018). From 2018, the term ‘assertive’ (or its derivations) was frequently used to describe China’s behaviour (Karp and Remeikis Citation2018), as were the militaristic images of China ‘flexing its muscles’ (Agence France Press Citation2018a), or ‘on the march’ (Australian Associated Press Citation2018a) as it sought to ‘aggressively expand its strategic presence in the Pacific’ (Packham Citation2018c; Citation2019; Callick Citation2016; Greenfield and Barrett Citation2018; White Citation2019) turning the Pacific ‘into a de facto Chinese lake within a decade’ (Jennings Citation2018; Hughes Citation2012).

As the COVID-19 pandemic spread in early 2020, media reports also focused on China engaging in ‘vaccine diplomacy’ in the ‘battle for influence’ (Packham Citation2020; Harris Citation2020), with Australia said to be ‘in a race against time to secure millions of COVID jabs for the Pacific’ (Packham Citation2021). There was also increased focus on ‘Chinese hacking and foreign interference’ (Galloway Citation2021) through China’s ‘penetration of the information domain’ in the region (Dupont Citation2021; Shoebridge Citation2021).

The threat framing relied on positioning Pacific states as ‘impoverished’ (Agence France Presse Citation2018a), ‘fragile,’ with ‘needy island governments’ (Levine Citation2012) that were ‘vulnerable’ (ABC News Citation2011) to ‘debt distress’ (Callick Citation2011) due to their ‘dependence’ (Oakes Citation2011b) on being ‘heavily indebted’ to China (Colton Citation2018). This characterisation reflected a longstanding presupposition that Pacific states are an ‘arc of instability’ (Ayson Citation2007). It also depended on characterising Pacific states as either venal – with China lining ‘the pockets of corrupt officials’ and ‘corrupt elites’ (Flitton Citation2012; Dziedzic Citation2018b; Jennings Citation2018; Packham Citation2018a) – or passive dupes ‘attached to easy money’ (Australian Associated Press Citation2018b). Pacific states were frequently presupposed to spend Chinese aid and loans poorly, resulting in ‘cash payments to local politicians and expensive but usually poorly maintained sporting arenas’ (Anderson Citation2016; Griffiths Citation2018), or to have ‘mistakenly assumed concessional loans would be eventually forgiven’ (Brant Citation2015) leading ‘to catastrophe and humiliation’ (Levine Citation2012). One 2012 headline stated: ‘End the cargo-cult mentality that has ruined our neighbours’ (Hughes Citation2012), while a 2017 headline warned that: ‘China emerges as all-powerful new deity in Pacific cargo cult’ (Newman Citation2017). The news that Solomon Islands and Kiribati switched their recognition to China in 2019 was followed by headlines asking ‘What does it take for China to take Taiwan’s Pacific allies? Apparently, $730 million’ (Whiting, Zhou, and Feng Citation2019), or observing that ‘Taiwan says China lures Kiribati with airplanes after losing another ally’ (Lee Citation2019). Each headline reflected longstanding pejorative Australian perceptions of the region.

The threat framing also positioned China as a malign actor in the Pacific Islands. Pacific states were described as ‘intimidated’ (Coorey Citation2011), with little agency to resist China. Fiji was characterised as a ‘geopolitical ‘football’ (Garnaut Citation2012), and Solomon Islands as ‘the latest domino to fall’ (Korporaal Citation2019). Indeed, media headlines described China’s behaviour as neo-colonial, with one headline describing ‘China’s Pacific Challenge – a chain of credit colonies’ (Dupont Citation2018) and reports claiming that: ‘Xi has effectively colonised the region that was once Australia’s sphere of influence’ (Newman Citation2018). The apparent denial of the agency of Pacific states was also evident in a tendency to frame the Pacific Islands as Australia’s ‘backyard’ (Clark Citation2018; Townshend and Thomas-Noone Citation2018; Wroe Citation2018g), with one 2019 headline declaring: ‘Pacific Neighbours invite bully into the backyard’ (Oriel Citation2019).

Throughout the decade the media consistently claimed that China’s perceived influence in the region made Australia feel ‘alarmed’ (Agence France Press Citation2018b), ‘anxious’ (Dziedzic Citation2018a; Hayward-Jones Citation2018), ‘fear[ful]’ (Dorling Citation2011a; Packham Citation2018b), ‘concern[ed]’ (Dorling Citation2011a; Citation2011b). China’s influence was portrayed as zero-sum, with claims that the Australian government saw ‘Beijing’s growing role as coming at Australia’s expense’ (Dorling Citation2011b). During the early part of the decade this framing focused on post-coup Fiji (Callick and Bodey Citation2014; Cullen Citation2011; Dorling Citation2011a; Herr and Bergin Citation2011; Kerin Citation2012; Oakes Citation2011a) but later on Vanuatu and Solomon Islands. The threat frame also frequently used language of competition and conflict. It commonly characterised Australia and its partners as being in a ‘rivalry’ (Herr and Bergin Citation2011), ‘battle for supremacy’ (Brien Citation2012), ‘race’ to ‘vie’ (Cullen Citation2011; Mcquillan Citation2012) or ‘compete’ to be a ‘counter’ (Entous Citation2011; Herr and Bergin Citation2011) against China.

The prevalence of the threat framing in the media and commentary, particularly after 2018, meant that Australian policy initiatives in the Pacific Islands were frequently presented as a response to China’s presence in the region, rather than discussed for their own merits or acknowledging that they may have had different motivations. For example, Australia’s ‘step up’ was characterised as part of a ‘tug-of-war for regional influence’ (Lyons Citation2018b), a ‘strategic battle to secure geopolitical and military dominance’ (Packham and Aikman Citation2018), or part of a ‘great game’ (Sheridan Citation2018). By framing the ‘Pacific step up’ almost exclusively in terms of China’s perceived threat, the media and commentary contributed to a perception that Australia’s renewed focus on the region was primarily about competing with China, rather than motivated by an interest in the priorities and needs of Pacific states themselves, thereby potentially undermining the capacity of these policies to enhance Australia’s relationships in the region (Morgan Citation2020; Varrall Citation2021; Wallis Citation2021).

Conclusion

The Australian government maintained a cautiously optimistic framing of China’s presence in the Pacific Islands until 2018, positioning China as a potential partner. But this was underpinned by Australia’s longstanding strategic anxiety about any power with potentially inimical interests establishing a foothold in the region. From 2018 onwards, Australian official discourse began to more explicitly frame China’s presence in the region as a threat. This provided at least part of the public rationale for the substantial spending necessary to implement Australia’s ‘Pacific step-up’ policy. China’s presence in the Pacific Islands was more explicitly framed as a threat in the media and commentary before this, but the frequency of that framing (and of coverage of China’s role in the region) increased significantly after the April 2018 reports that China was in talks to build a military base in Vanuatu, echoing changes in the Australian government’s approach. Significantly, the first of these reports claimed that ‘top national security figures in Canberra and Washington’ were ‘deeply concerned about China’s ambitious for Vanuatu’ (Wroe Citation2018c), suggesting that at least some sources may have come from within the government (Dobell Citation2018b). The claims in that report were frequently repeated in subsequent coverage. The threat framing positioned China as Australia’s competitor, as it was presupposed to be using its tools of statecraft to influence the region in pursuit of strategic objectives that undermined Australia’s security. It is impossible to isolate Australians’ perception of China in the Pacific Islands from their broader understanding of China’s increasingly activist role in Australia, the Indo-Pacific, and globally. But given the overwhelming frequency of the threat framing in the media and – to a lesser extent the commentary – this likely contributed to constructing China as a threat. This, in turn, likely facilitated public reception of a more threat-oriented framing in the official discourse and support for substantial government investments via the ‘Pacific step-up’. Indeed, the 2019 Lowy Institute Poll found that 73 percent of respondents agreed that ‘Australia should try to prevent China from increasing its influence in the Pacific’. More than half (55 percent) believed that China establishing a military base in the region would critically threaten Australia’s interests, and 54 percent agreed that ‘Australia should partner with Papua New Guinea and the United States in redeveloping a joint military base on Manus Island’ in PNG (Lowy Citation2019).

Pacific Island leaders have clearly expressed their concern about the threat framing, particularly that it has undermined their agency and autonomy, and contributed to a belief that Pacific states will eventually have to make a strategic choice between China and their traditional partners. Former Pacific Islands Forum Secretary General Dame Meg Taylor (Citation2019) has stated she ‘reject[s] the terms of the dilemma in which the Pacific is given a choice between a ‘China alternative’ and our traditional partners’. This suggests that, while the media coverage and commentary explained Australia’s anxiety about China’s role in the Pacific in a way that made sense of Australia’s changing foreign policy approach for the Australian public (Davis and Brookes Citation2016), much of it has had counter productive effects, undermining Australia’s relationships in the Pacific by exacerbating a threat framing that many Pacific states and leaders reject, and which in fact makes them feel insecure.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the University of Adelaide Summer Research Scholarship scheme, which supported Angus, Isabel, and Alicia to work with Joanne on this project. Joanne is also thankful for the significant amount of work that Angus, Isabel, and Alicia invested in the data collection and analysis for this project over their summer break, and for the thoughtful and constructive feedback of the anonymous reviewers and journal editors.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Joanne Wallis

Joanne Wallis is Professor of International Security in the Department of Politics and International Relations at the University of Adelaide.

Angus Ireland

Angus Ireland is undergraduate students at the University of Adelaide.

Isabel Robinson

Isabel Robinson is undergraduate students at the University of Adelaide.

Alicia Turner

Alicia Turner is undergraduate students at the University of Adelaide.

Notes

1 Pacific Island signatories are: Cook Islands, Federated States of Micronesia, Fiji, Niue, Papua New Guinea, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tonga and Vanuatu. China State Information Center, ‘Belt and Road Portal’, https://eng.yidaiyilu.gov.cn/info/iList.jsp?cat_id=10076&tm_id=80&cur_page=1

2 NB: ‘Data for 2019 and 2020 has not been reported for all donors and is incomplete. 2018 is the latest year of comprehensive aid data from all donors.’

References

- Abbott, Tony. 2014. “Joint Press Statement with President Xi, Canberra.” November 17. https://pmtranscripts.pmc.gov.au/release/transcript-23977.

- ABC News. 2011. “China Expands Loans to Pacific Island nations.” ABC News, April 4. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2011-04-04/china-expands-loans-to-pacific-island-nations/2628664.

- Agence France Presse. 2018a. “China's Huawei, ZTE blocked from Australia's 5G network”. August 23.

- Agence France Presse. 2018b. “Australia Hikes aid in Pacific as China Pushes for Influence.” May 9.

- Anderson, Fleur. 2016. “Australia needs to get Its Regional Alliances in Order.” Australian Financial Review, November 11.

- Atkinson, Joel. 2010. “China-Taiwan Diplomatic Competition and the Pacific Islands.” The Pacific Review 23 (4): 407–427.

- Australian Associated Press. 2018a. “Tongan PM Warns of Chinese loans.” Australian Associated Press, August 15.

- Australian Associated Press. 2018b. “Aust, NZ must Team Up on Pacific Policies.” Australian Associated Press, March 2.

- Ayson, Robert. 2007. “The ‘Arc of Instability’ and Australia’s Strategic Policy.” Australian Journal of International Affairs 61 (2): 215–231.

- Baker, Nicola. 2018. “Aid, Influence and ‘Strategic Anxiety’ in the Pacific.” East Asia Forum, April 20. https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2018/04/20/aid-influence-and-strategic-anxiety-in-the-pacific/.

- Bishop, Julie. 2014a. “Opening address – 2014 Australasian Aid and International Development Policy workshop.” Canberra, February 14. https://www.foreignminister.gov.au/minister/julie-bishop/speech/opening-address-2014-australasian-aid-and-international-development-policy-workshop.

- Bishop, Julie. 2014b. “Australia in China’s Century.” Melbourne, May 30. https://www.foreignminister.gov.au/minister/julie-bishop/speech/australia-chinas-century.

- Bishop, Julie. 2016. “Doorstop Interview - Beijing, China.” Beijing, February 17. https://www.foreignminister.gov.au/minister/julie-bishop/transcript-eoe/doorstop-interview-beijing-china.

- Brant, Philippa. 2015. “The Geopolitics of Chinese aid: Mapping Beijing’s Funding in the Pacific.” Lowy Institute, March 4. https://www.lowyinstitute.org/publications/geopolitics-chinese-aid.

- Brien, Derek. 2012. “Pacific Diplomacy needs Recalibrating.” The Australian, May 21.

- Brunnstrom, David, and Michael Martina. 2021. “U.S. says to Work with Allies to Help Pacific islands Amid China Rivalry.” Reuters, June 9.

- Callick, Rowan. 2011. “Fiji Casts Shadow on Pacific forum.” The Australian, September 5.

- Callick, Rowan. 2016. “Planet Trump Retreat Good News for China and Xi Jinping.” The Australian, July 28.

- Callick, Rowan, and Michael Bodey. 2014. “Radio Australia — and the Pacific — Suffering Thanks to ABC’s Network Merger.” The Australian, August 4.

- Clark, Andrew. 2018. “Time to Reset Our China Policy.” Australian Financial Review, February 2.

- Claxton, Karl. 2013. “Decoding China’s rising Influence in the South Pacific.” The Strategist, May 17. https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/decoding-chinas-rising-influence-in-the-south-pacific/.

- Colton, Greg. 2018. “Safeguarding Australia’s Security Interests through Closer Pacific Ties.” Lowy Institute, April 4. https://www.lowyinstitute.org/publications/stronger-together-safeguarding-australia-s-security-interests-through-closer-pacific-0.

- Connolly, Peter. 2016. “Engaging China’s New Foreign Policy in the South Pacific.” Australian Journal of International Affairs 70 (5): 484–505.

- Connolly, Peter. 2020. “The Belt and Road Comes to Papua New Guinea: Chinese Geoeconomics with Melanesian Characteristics?” Security Challenges 16 (4): 41–64.

- Coorey, Phillip. 2011. “Pax Americana in the Pacific.” Sydney Morning Herald, November 18.

- Coorey, Madeleine. 2012. “China raises Profile as Tonga Rebuilds after Riots.” Yahoo! News, April 29. https://sg.news.yahoo.com/china-raises-profile-tonga-rebuilds-riots-163239304.html.

- Crocombe, Ron. 2007. Asia in the Pacific Islands: Replacing the West. Suva: University of the South Pacific.

- Cullen, Simon. 2011. “Pacific Leaders Wooed by the World.” ABC News, September 8. https://www.abc.net.au/radio/programs/pm/pacific-leaders-wooed-by-the-world/2879028.

- D’Arcy, Paul. 2007. China in the Pacific: Some Policy Considerations for Australia and New Zealand, SSGM Discussion Paper 2007/4. Canberra: Australian National University.

- Davidson, Helen. 2018. “Warning Sounded over China's ‘Debtbook Diplomacy’.” The Guardian, May 15.

- Davis, Alexander E., and Stephanie Brookes. 2016. “Australian Foreign Policy and News Media: National Identity and the Sale of Uranium to India and China.” Australian Journal of Political Science 51 (1): 51–67.

- Dayant, Alexandre, and Jonathan Pryke. 2018. “Pivoting to the Pacific.” The Strategist, August 9. https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/pivoting-to-the-pacific/.

- DFAT (Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade). 2017. 2017 Foreign Policy White Paper. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

- Dobell, Graeme. 2007. China and Taiwan in the South Pacific: Diplomatic Chess versus Pacific Political Rugby, CSCSD Occasional Paper Number 1. Canberra: Australian National University.

- Dobell, Graeme. 2018a. “Australia frets and fights over the South Pacific.” The Strategist, January 22. https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/australia-frets-fights-south-pacific/.

- Dobell, Graeme. 2018b. “Awkward Alarum: China, Vanuatu and Oz”. The Strategist, 16 April, https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/awkward-alarum-china-vanuatu-oz/.

- Dobell, Graeme. 2018c. “China Challenges Australia in the South Pacific.” The Strategist, October 2. https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/china-challenges-australia-in-the-south-pacific/.

- DoD (Department of Defence). 2013. Defence White Paper 2013. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

- DoD (Department of Defence). 2014. 2014 Defence Issues White Paper. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

- DoD (Department of Defence). 2016. 2016 Defence White Paper. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

- DoD (Department of Defence). 2020. 2020 Defence Strategic Update. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

- Doherty, Ben. 2018. “China's aid to Papua New Guinea threatens Australia's influence.” The Guardian, July 3.

- Dorling, Philip. 2011a. “Fears over China's growing influence.” Sydney Morning Herald, September 2.

- Dorling, Philip. 2011b. “Canberra ‘Threatened’ by Chinese Conduct in Pacific.” The Age, September 2.

- Dornan, Matthew, and Philippa Brant. 2014. “Chinese Assistance in the Pacific: Agency, Effectiveness and the Role of Pacific Island Government.” Asia & the Pacific Policy Studies 1 (2): 349–363.

- Doty, Roxanne. 1993. “Foreign Policy as Social Construction: A Post-Positivist Analysis of U.S. Counterinsurgency Policy in the Philippines.” International Studies Quarterly 37 (3): 297–320.

- Dunn, Kevin C., and Iver B. Neumann. 2016. Undertaking Discourse Analysis for Social Research. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Dupont, Patrick. 2018. “China's Pacific challenge: a chain of credit colonies.” The Australian, September 4.

- Dupont, Patrick. 2021. “The United States’ Indo–Pacific Strategy and a Revisionist China: Partnering with Small and Middle Powers in the Pacific Islands Region.” Issues & Insights 21 (2): 1–40.

- Dziedzic, Stephen. 2018a. “Tonga called on Pacific islands to band together against China — then had a sudden change of heart.” ABC News, August 20. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-08-20/tonga-prime-minister-changes-mind-on-china-loan-issue/10138068.

- Dziedzic, Stephen. 2018b. “US and Australia working to counter China's PNG internet bid, top US diplomat confirms.” ABC News, September 28. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-09-28/us-and-australia-team-up-to-counter-china-internet-bid-in-png/10315750.

- Entman, Robert M. 1993. “Framing: Toward Clarification of a Fractured Program.” Journal of Communication 43 (4): 51–58.

- Entous, Adam. 2011. “Panetta says US committed to being Pacific power.” The Wall Street Journal, October 24.

- Fletcher, Luke, and Pichamon Yeophantong. 2019. Enter the Dragon: Australia, China, and the New Pacific Development Agenda. Sydney: Jubilee Australia Research Centre, Caritas Australia, and the University of New South Wales.

- Flitton, Daniel. 2011. “Rudd Accused of Neglecting Troubles in the Backyard.” Sydney Morning Herald, April 11.

- Flitton, Daniel. 2012. “Pacific Islanders relish their Moment on Diplomatic Stage.” Sydney Morning Herald, August 29.

- Flitton, Daniel. 2014. “Voiceless in the South Pacific.” Sydney Morning Herald, August 28.

- Fox, Rohan, and Matthew Dornan. 2018. “China in the Pacific: Is China Engaged in “Debt-Trap Diplomacy”?”. DevPolicy, November 8. https://devpolicy.org/is-china-engaged-in-debt-trap-diplomacy-20181108/?utm_source=Devpolicy&utm_campaign=22334c1efb-Devpolicy+News+Dec+15+2017_COPY_01&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_082b498f84-22334c1efb-227683262.

- Galloway, Anthony. 2021. “Pacific Islands Forum on brink of collapse over leadership dispute.” Sydney Morning Herald, February 8.

- Garnaut, John. 2012. “China cosies up to Fiji for influence.” Sydney Morning Herald, September 26.

- Gartrell, Adam. 2011. “Rudd to press China on aid secrecy.” Australian Associated Press, November 27.

- Gillard, Julia. 2013a. “Foreign Correspondents Association Newsmaker Lunch.” Sydney, April 4. https://pmtranscripts.pmc.gov.au/release/transcript-19196.

- Gillard, Julia. 2013d. “Transcript of Joint Press Conference.” Canberra, May 3. https://pmtranscripts.pmc.gov.au/release/transcript-19314.

- Graue, Catherine, and Stephen Dziedzic. 2018. “Federal Minister Concetta Fierravanti-Wells accuses China of funding ‘roads that go nowhere’ in Pacific.” ABC, January 10. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-01-10/australia-hits-out-at-chinese-aid-to-pacific/9316732.

- Greenfield, Charlotte, and Jonathan Barrett. 2018. “Tonga PM fears asset seizures as Pacific debts to China mount.” Reuters, August 16.

- Griffiths, Tom. 2018. “China’s Pacific ‘AID’ is Part of Its Grand Plan to Dominate.” The Australian, January 10.

- Hannan, Kate, and Stewart Firth. 2015. “Trading with the Dragon: Chinese Trade, Investment and Development Assistance in the Pacific Islands.” Journal of Contemporary China 24 (95): 865–882.

- Hanson, Fergus, and Mary Fifita. 2011. China in the Pacific: The New Banker in Town, Policy Brief. Sydney: Lowy Institute.

- Harris, Rob. 2020. “Australia Commits $500 m for COVID-19 Vaccine for the Pacific and south-east Asia.” Sydney Morning Herald, October 31.

- Hayward-Jones, Jenny. 2013. “Big Enough for All of Us: Geo-Strategic Competition in the Pacific Islands.” Lowy Institute, May 16. https://www.lowyinstitute.org/publications/big-enough-all-us-geo-strategic-competition-pacific-islands.

- Hayward-Jones, Jenny. 2018. “Diverging Regional Priorities at the Pacific Islands Forum.” Australian Outlook, September 3. https://www.internationalaffairs.org.au/australianoutlook/diverging-regional-priorities-at-pacific-islands-forum/.

- Henderson, John, and Benjamin Reilly. 2003. “Dragon in Paradise: China’s Rising Star in Oceania.” The National Interest 72: 94–104.

- Herr, Richard, and Anthony Bergin. 2011. “US moves to counter China in the Pacific.” The Australian, December 1.

- Hudson, Valerie M., and Benjamin Day. 2019. Foreign Policy Analysis: Classic and Contemporary Theory. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Hughes, Helen. 2012. “End the Cargo-Cult Mentality that has Ruined Our Neighbours.” The Australian, April 16.

- Jennings, Peter. 2016. “Australia needs To Limit Its Exposure to Corruptive Influences.” The Australian, September 3.

- Jennings, Peter. 2018. “With Donald at Large, Australia needs a Plan B for defence.” The Australian, July 21.

- Jingye, Cheng. 2018. “Pacific Islands want China’s aid - Just Ask Them.” Australian Financial Review, January 19.

- Karp, Paul, and Amy Remeikis. 2018. “Labor’s Penny Wong says world ‘rethinking how best to work with the US.’” The Guardian, July 18.

- Kehoe, John, Andrew Tillett, and Philip Coorey. 2018. “Labor Ready to Counter China in Pacific.” Australian Financial Review, May 4.

- Kenderdine, Tristan. 2017. “Putting the Pacific on China’s Radar.” East-West Center, January 4. https://www.eastwestcenter.org/publications/putting-the-pacific-chinas-radar.

- Kerin, John. 2012. “Fiji returns from Cold.” Australian Financial Review, July 31.

- Korporaal, Glenda. 2019. “Solomons the Latest Domino to Fall in China’s Taiwan Plan.” The Australian, September 18.

- Laclau, Ernesto. 2005. On Populist Reason. London: Verso.

- Lanteigne, Marc. 2012. “Water Dragon? China, Power Shifts and Soft Balancing in the South Pacific.” Political Science 61 (1): 21–38.

- Lee, Yimou. 2019. “Taiwan says China lures Kiribati with airplanes after losing another ally.” Reuters, September 20.

- Lei, Yu, and Sophia Sui. 2022. “China–Pacific Island Countries Strategic Partnership: China’s Strategy to Reshape the Regional Order.” East Asia, 39 (1): 81–96.

- Levine, Stephen. 2012. “Pacific States must Pursue a Prudent Course.” The Australian, May 29.

- Lowy Institute. 2019. “Lowy Institute Poll 2019”. Lowy Institute. https://poll.lowyinstitute.org/charts/australia-in-the-pacific.

- Lowy Institute. 2020. “Pacific Aid Map.” Lowy Institute. https://pacificaidmap.lowyinstitute.org/graphingtool.

- Lyons, Kate. 2018a. “Huge increase in Chinese aid pledged to the Pacific.” The Guardian, August 9.

- Lyons, Kate. 2018b. “‘The China show': Xi Jinping arrives in PNG for start of Apec summit.” The Guardian, November 16. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/nov/16/the-china-show-xi-jinping-arrives-in-png-for-start-of-apec-summit.

- Mcquillan, Laura. 2012. “Pacific vital to US, Clinton says.” Australian Associated Press, September 1.

- Meick, Ethan, Michelle Ker, and Han May Chan. 2018. China’s Engagement in the Pacific Islands: Implications for the United States. Washington: U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission.

- Minus, Jodie. 2011. “Bishop call to sign up Chinese.” The Australian, April 11.

- Morgan, Wesley. 2020. “Oceans Apart? Considering the Indo-Pacific and the Blue Pacific.” Security Challenges 16 (1): 44–64.

- Morrison, Scott. 2018a. “Australia and the Pacific: A New Chapter.” Lavarack Barracks, Townsville, November 8. https://www.pm.gov.au/media/address-australia-and-pacific-new-chapter.

- Morrison, Scott. 2018b. “Keynote Address to Asia Briefing Live - “The beliefs that guide us.” Sydney, November 1. https://www.pm.gov.au/media/keynote-address-asia-briefing-live-beliefs-guide-us.

- Morrison, Scott. 2019a. “Chicago Council on Global Affairs.” Chicago, September 23. https://www.pm.gov.au/media/chicago-council-global-affairs.

- Morrison, Scott. 2019b. “Doorstop - Nadi, Fiji.” Nadi, October 12. https://www.pm.gov.au/media/doorstop-nadi-fiji.

- Morrison, Scott. 2021. “National Press Club Barton ACT.” Barton, February 1. https://www.pm.gov.au/media/address-national-press-club-barton-act.

- Moyle, Euan, and Alexandre Dayant. 2018. “Reconciling with China in the Pacific.” The Strategist, October 15. lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/reconciling-china-pacific.

- Mudaliar, Christopher. 2018. “Australia outbids China to fund Fiji Military Base.” The Interpreter, October 4. https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/australia-outbids-china-fund-fiji-military-base.

- Newman, Maurice. 2017. “China emerges as All-Powerful New Deity in Pacific Cargo Cult.” The Australian, 31 December.

- Newman, Maurice. 2018. “It may not be fashionable, but the South Pacific counts.” The Australian, May 2.

- Oakes, Dan. 2011a. “Fijian Shadow Looms over Pacific Island Conference.” Sydney Morning Herald, September 6.

- Oakes, Dan. 2011b. “Chinese Loans in Pacific on the Rise.” Sydney Morning Herald, April 6.

- O’Keefe, Michael. 2013. “Pacific Cold War last thing we want.” The Australian, March 25.

- O’Keefe, Michael. 2020. “The Militarisation of China in the Pacific: Stepping Up to a New Cold War?” Security Challenges 16 (1): 94–112.

- Oriel, Jennifer. 2019. “Pacific Neighbours Invite Bully into the Backyard.” The Australian, August 19.

- Pacific Beat. 2017a. “Undersea cable deal with PNG inked amid concerns over Chinese influence in the Pacific.” ABC News, November 13. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-11-14/png-to-get-new-australia-funded-undersea-internet-cable/9146570.

- Pacific Beat. 2017b. “One Belt, One Road: ‘Colonial Power’ fears Limiting Australia, Labor warns, as China signs PNG deals.” ABC News, November 21. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-11-21/labor-warns-australian-caution-in-pacific-as-china-signs-png/9174272.

- Pacific Beat. 2018a. “Chinese Military Base in Pacific would be of ‘Great Concern’, Turnbull tells Vanuatu.” ABC News, April 10. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-04-10/china-military-base-in-vanuatu-report-of-concern-turnbull-says/9635742.

- Pacific Beat. 2018b. “Interview with Catherine Graue, Pacific Beat.” Parliament of Australia, June 27. https://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/search/display/display.w3p;query=Id:%22media/pressrel/6051715%22.

- Packham, Ben. 2018a. “Pacific ‘Biggest Single Hole in Australia’s strategic policy’: Labor.” The Australian, April 10.

- Packham, Ben. 2018b. “Move to Head off China with Aussie Base in PNG.” The Australian, September 20.

- Packham, Ben. 2018c. “Chinese investment alarms PNG MPs.” The Australian, November 15.

- Packham, Ben. 2019. “Jitters as China spruiks Samoa Deals.” The Australian, October 20.

- Packham, Ben. 2020. “China Testing Its Vaccine in Papua New Guinea.” The Australian, August 20.

- Packham, Ben. 2021. “China Winning Vaccine Diplomacy War.” The Australian, April 4.

- Packham, Ben, and Amos Aikman. 2018. “Alliance to Test China's resolve in Pacific.” The Australian, November 16.

- Pan, Chengxin, Matthew Clarke, and Sophie Loy-Wilson. 2019. “Local Agency and Complex Power Shifts in the Era of Belt and Road: Perceptions of Chinese Aid in the South Pacific.” Journal of Contemporary China 28 (117): 385–399.

- Parker, Sam, and Gabrielle Chefitz. 2018. Debtbook Diplomacy: China’s Strategic Leveraging of its Newfound Economic Influence and the Consequences for U.S. Foreign Policy. Cambridge, MA: Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. https://www.belfercenter.org/sites/default/files/files/publication/Debtbook%20Diplomacy%20PDF.pdf.

- Payne, Marise. 2021. “Address to Australia China Business Council.” Canberra, August 5. https://www.foreignminister.gov.au/minister/marise-payne/speech/address-australia-china-business-council.

- PM&C (Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet). 2017. “Media Release – Pacific Islands Forum in Samoa.” September 6. https://pmtranscripts.pmc.gov.au/release/transcript-41165 https://www.malcolmturnbull.com.au/media/remarks-at-pacific-island-forum-micronesia.

- Powles, Michael. 2007. China Looks to the Pacific, CSCSD Occasional Paper Number 1. Canberra: Australian National University.

- Pryke, Jonathan. 2019. “Solomons and Kiribati snub Taiwan for China – does it matter?” The Interpreter, September 23. https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/solomons-and-kiribati-snub-taiwan-china-does-it-matter.

- Rajah, Roland, Alexandre Dayant, and Jonathan Pryke. 2019. Ocean of Debt? Belt and Road and Debt Diplomacy in the Pacific. Sydney: Lowy Institute.

- Remeikis, Amy. 2018. “Julie Bishop in balancing act after colleague criticises China’s Pacific aid.” The Guardian, January 11.

- Robinson, Piers. 2001. “Theorizing the Influence of Media on World Politics: Models of Media Influence on Foreign Policy.” European Journal of Communication 16 (4): 523–544.

- Rudd, Kevin. 2008. “Port Moresby Declaration.” March 6. https://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/search/display/display.w3p;query=Id:%22media/pressrel/2KUP6%22.

- Safi, Michael. 2015. “China Increases Its Aid Contribution to Pacific Island Nations.” The Guardian, March 2. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/mar/02/china-increases-aid-contribution-pacific.

- Sheridan, Greg. 2014. “Right move to Bring Fiji back into the fold.” The Australian, February 17.

- Sheridan, Greg. 2018. “Major moves: Morrison has Remade Australia's Strategic Position.” The Australian, November 23.

- Shie, Tamara Renee. 2010. “Rising Chinese Influence in the South Pacific: Beijing’s “Island Fever”.” Asian Survey 47 (2): 307–326.

- Shiming, Wang. 2019. “Open Regionalism and China-Australia Cooperation in the South Pacific.” China International Studies 75: 84–108.

- Shoebridge, Michael. 2021. “Ardern–Morrison meeting about the Pacific, Not China Policy Shenanigans.” The Strategist, May 29. https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/ardern-morrison-meeting-about-the-pacific-not-china-policy-shenanigans/.

- Smith, Graeme. 2012. “Are Chinese Soft Loans Always a Bad Thing?” The Interpreter, March 29. https://archive.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/are-chinese-soft-loans-always-bad-thing.

- Smith, Graeme. 2015. “China in the Pacific: Zombie Ideas Stalk On.” State, Society and Governance in Melanesia: In Brief 2015 (2): 1–2. https://dpa.bellschool.anu.edu.au/sites/default/files/publications/attachments/2015-12/SSGM_IB_2015_2_Smith_0.pdf.

- Taylor, Meg. 2019. “A rising China and the future of the “Blue Pacific”.” The Interpreter, February 15. https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/rising-china-and-future-blue-pacific.

- Townshend, Ashley, and Brendan Thomas-Noone. 2018. “Australia must Refocus Foreign Policy on Its Own Indo-Pacific Region.” Australian Financial Review, July 23.

- Turnbull, Malcolm. 2018. “Speech at the University of New South Wales.” Sydney, August 7. https://pmtranscripts.pmc.gov.au/release/transcript-41723.

- Varrall, Merriden. 2021. “Australia’s Response to China in the Pacific: From Alert to Alarmed.” In The China Alternative: Changing Regional Order in the Pacific Islands, edited by Graeme Smith, and Terence Wesley-Smith, 107–141. Acton: ANU Press.

- Wallace, Rick. 2012. “Pacific Aid has Strings Attached as Russia seeks to Buy Favours.” The Australian, May 26.

- Wallis, Joanne. 2012. “The dragon in our backyard: the strategic consequences of China’s increased presence in the South Pacific.” The Strategist, August 30. https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/the-dragon-in-our-backyard-the-strategic-consequences-of-chinas-increased-presence-in-the-south-pacific/.

- Wallis, Joanne. 2017a. Pacific Power? Australia’s Strategy in the Pacific Islands. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press.

- Wallis, Joanne. 2017b. Crowded and Complex: The Changing Geopolitics of the South Pacific. Canberra: Australian Strategic Policy Institute.

- Wallis, Joanne. 2021. “Contradictions in Australia’s Pacific Islands Discourse.” Australian Journal of International Affairs 97 (4): 487–506.

- Wesley-Smith, Terence. 2013. “China’s Rise in Oceania: Issues and Perspectives.” Pacific Affairs 86 (2): 351–372.

- Wesley-Smith, Terence, and Graeme Smith. 2021. “Introduction: The Return of Great Power Competition.” In The China Alternative: Changing Regional Order in the Pacific Islands, edited by Graeme Smith, and Terence Wesley-Smith, 1–40. Acton: ANU Press.

- White, Hugh. 2019. “Australia must prepare for a Chinese military base in the Pacific.” The Guardian, July 15.

- Whiting, Natalie, Christina Zhou, and Kai Feng. 2019. “What does it take for China to take Taiwan's Pacific allies? Apparently, $730 million.” ABC News, September 18. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-09-18/solomon-islands-cuts-ties-with-taiwan-in-favour-of-china/11524118.

- Windybank, Susan. 2005. “The China Syndrome.” Policy 21 (2): 28–33.

- Wroe, David. 2017. “Australia Refuses to Connect to Undersea Cable Built by Chinese Company.” Sydney Morning Herald, July 26.

- Wroe, David. 2018a. “China eyes Vanuatu Military Base in Plan with Global Ramifications.” Sydney Morning Herald, April 9.

- Wroe, David. 2018b. “The Great Wharf from China, Raising Eyebrows across the Pacific.” Sydney Morning Herald, April 11.

- Wroe, David. 2018c. “Vanuatu PM defends China deals but vows to oppose any new foreign military base.” Sydney Morning Herald, 12 April.

- Wroe, David. 2018d. “Trouble in Paradise.” Sydney Morning Herald, April 13.

- Wroe, David. 2018e. “Australia will Compete with China to Save Pacific Sovereignty, says Bishop.” Sydney Morning Herald, June 18.

- Wroe, David. 2018f. “Looking north: PNG signs on to China's Belt and Road Initiative.” Sydney Morning Herald, June 21.

- Wroe, David. 2018g. “Payne Heads to Pacific meeting with a nod to Neighbours’ Climate Fears.” Sydney Morning Herald, September 2.

- Wyeth, Grant. 2016. “What to Make of China in the South Pacific?” The Diplomat, September 29. https://thediplomat.com/2016/09/what-to-make-of-china-in-the-south-pacific/.

- Yang, Jian. 2009. “China in the South Pacific: Hegemon on the Horizon?” The Pacific Review 22 (2): 139–158.

- Zhang, Yongjin. 2007. “China and the Emerging Regional Order in the South Pacific.” Australian Journal of International Affairs 61 (3): 367–381.

- Zhang, Feng. 2016. “Should Australia Worry about Chinese Expansion in the South Pacific?” The Strategist, July 11. https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/australia-worry-chinese-expansion-south-pacific/.

- Zhang, Denghua. 2017a. “China’s Diplomacy in the Pacific: Interests, Means and Implications.” Institute for Regional Security 13 (2): 32–53.

- Zhang, Denghua. 2017b. “Why Cooperate with Others? Demystifying China’s Trilateral aid Cooperation.” The Pacific Review 30 (5): 750–768.

- Zhang, Denghua. 2019a. “Working with China on Humanitarian Aid in the Pacific.” East Asia Forum, July 26. https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2019/07/26/working-with-china-on-humanitarian-aid-in-the-pacific/.

- Zhang, Denghua. 2019b. “China Constrained as much as Controlling in the South Pacific.” East Asia Forum, May 16. https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2019/05/16/china-constrained-as-much-as-controlling-in-the-south-pacific/.

- Zhang, Denghua. 2020a. A Cautious New Approach: China’s Growing Trilateral Aid Cooperation. Acton: Australian National University Press.

- Zhang, Denghua. 2020b. “China in the Pacific and Traditional Powers’ New Pacific Policies: Concerns, Responses and Trends.” Security Challenges 16 (1): 78–93.

- Zhang, Denghua. 2021. “China’s Motives, Influence and Prospects in Pacific Island Countries: Views of Chinese Scholars.” International Relations of the Asia-Pacific 1 (1): 1–27.

- Zhang, Denghua, and Stephanie Lawson. 2017. “China in Pacific Regional Politics.” The Round Table 106 (2): 197–206.

- Zhang, Denghua, and Hemant Shivakumar. 2017. “Dragon Versus Elephant: A Comparative Study of Chinese and Indian Aid in the Pacific.” Asian and the Pacific Policy Studies 4 (2): 260–271.

- Zhou, Fangyin. 2021. “A Reevaluation of China's Engagement in the Pacific Islands.” In The China Alternative: Changing Regional Order in the Pacific Islands, edited by Graeme Smith, and Terence Wesley-Smith, 233-258. Acton: ANU Press.