ABSTRACT

Climate change can undermine human, national and planetary security in various ways. While scholars harve explored the human security implications of climate change and climate security discourses in Australia, systematic scientific assessments of climate change and national security are scarce. I address this knowledge gap by analysing whether climate change impacts the national security of Australia before 2050, focussing particularly on climate-related threats within Australia and on countries of high strategic importance for Australia. The results indicate that climate change will very likely undermine Australia’s national security by disrupting critical infrastructure, by challenging the capacity of the defence force, by increasing the risk of domestic political instability in Australia’s immediate region, by reducing the capabilities of partner countries in the Asia-Pacific region, and by interrupting important supply chains. These impacts will matter most if several large-scale disasters co-occur or if Australia becomes involved in a major international conflict. By contrast, international wars, large-scale migration, and adverse impacts on key international partners are only minor climate-related risks.

Introduction

Climate change is increasingly perceived as a security issue by scholars and policy makers.Footnote1 There has been extensive research on the impact of climate change for human security and livelihoods (O'Brien and Barnett Citation2013), armed conflict (Mach et al. Citation2019), and migration (Hoffmann et al. Citation2020), among others. Likewise, high-ranking security policy institutions like the UN Security Council (Citation2021) and NATO (Citation2021) are considering climate change-related risks with increased frequency. In Australia, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese (Citation2022) recently stated: ‘The security implications of climate change are clear and cannot be ignored.’ Leading Australian security analysts conceive climate change, particularly in the Asia-Pacific region, as ‘a global systemic crisis with disruptions that will transform the geopolitical landscape’ (Glasser Citation2022: v)

Security is a broad and contested term subject to different interpretations. Particularly since the 1990s, various approaches have challenged traditional (yet far from unequivocal) definitions of security as national integrity and national sovereignty. Proponents of human security argue for a focus on human safety and well-being, placing individuals at the centre of analysis, while securitisation scholars contend that what counts as a security issue (and whose security is threatened by whom/what) is socially constructed rather than objectively given. Building on these debates and an empirical analysis of climate security discourses in several countries, Diez, von Lucke, and Wellmann (Citation2016, 20–24) distinguish three broad understandings of climate security: (i) a territorial understanding focussed on state security and national interests, (ii) an individual understanding concerned with the adverse impacts of food insecurity, water scarcity and disasters on individuals and social groups, and (iii) a planetary understanding highlighting climate change impacts on ecosystems and the earth system as a whole.

In general, the human security implications of climate change are uncontested (O'Brien and Barnett Citation2013) and are also well-documented in the Australian context (see section 'Climate change in Australia' and, for instance: CSIRO and BoM Citation2020; Rice et al. Citation2022; van Oldenborgh et al. Citation2021). Likewise, scholars like McDonald (Citation2015, Citation2021a) and Thomas (Citation2017) have conducted in-depth analyses of climate security discourses in Australia. Recently, McDonald (Citation2021b) made a comprehensive argument for a planetary perspective on ecological security, including in Australia.

Research has also focussed on the implications of climate change for national security and territorial reference objects. One the one hand, critical approaches have argued that such a ‘narrow’ focus is only concerned with symptoms (e.g. political instability, border insecurity) rather than the causes (e.g. CO2 emissions) of the problem, and can be ignorant to the suffering of individuals and groups as a territorial lens is overly state-centric (Diez, von Lucke, and Wellmann Citation2016; Telford Citation2018). On the other hand, assessments of national security implications of climate change can provide important contributions to academic debates in the fields of ‘traditional’ security studies, strategic studies and classical geopolitics as well as to broader debates on foreign, defence and economic policies (Farbotko Citation2018; von Uexkull and Buhaug Citation2021).Footnote2

As of yet, there is no systematic, research-based analysis of the national security implications of climate change in Australia. Such works exist for the USA (Busby Citation2008) and Canada (Greaves Citation2021), for instance, but even the comprehensive volume of Moran (Citation2011) (analysing 43 countries) does not contain a chapter on Australia.

After coming into office in mid-2022, the Albanese government ordered the Office of National Intelligence to assess climate and security risks, but the methods and findings remain classified. Previously, the Senate’s Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade References Committee (FADTRC Citation2018) and Durrant, Bradshaw, and Pearce (Citation2021) produced substantial reports on climate change and national security in Australia. However, the former is based on voluntary inputs by various individuals and institutions rather than a systematic assessment of existing evidence and the latter mostly focuses on two issues (geopolitical influence and the water-conflict nexus). Both also show only very limited engagement with peer-reviewed research and provide no clear conceptual framework or definition of security that could be used for comparative analyses (e.g. over time or between countries). While these issues are common among policy reports, they illustrate the need for a (complementary) academic analysis.

My study addresses this gap by analysing the national security implications of climate change in Australia based on a clear and comprehensive definition of national security, as well as scientific studies and data. The analysis is guided by the following research question: Which aspects (or dimensions) of national security in Australia might be affected by climate change, and what is the evidence that such effects will occur prior to 2050?

To answer this question, I will mostly rely on information from existing peer-reviewed studiesFootnote3, complemented by government documents, non-peer-reviewed reports written by leading experts, and statistical data when appropriate. The temporal focus of this article ranges from now to 2050 because uncertainty about climatic change and its impacts increases with extended time horizons, not at least due to the varying impacts of different emission scenarios.

The next section provides a definition of national security and specifies particular dimensions of national security that can be affected by climate change. Afterwards, I summarise how climate change will likely play out in Australia and how these impacts will affect national security. The paper ends with a brief discussion and conclusion.

Defining national security

Like the concept of ‘security’, ‘national security’ is also multifaceted and contested. Almost all NGO and government reports and even the majority of academic publications dealing with climate change and security provide no definition of national security. This makes identifying the scope of their work and comparing findings challenging. Likewise, there is no consensus on the definition of national security in Australia. The 2016 Defence White Paper, the 2020 Defence Strategic Update (Department of Defence Citation2016, Citation2020), and the national security homepage of the Department of Home Affairs (Citation2022), for instance, all use the term multiple times, but provide no explicit definition.

In this article, I follow Harold Brown, who understands national security as ‘the ability to preserve the nation's physical integrity and territory; to maintain its economic relations with the rest of the world on reasonable terms; to preserve its nature, institutions, and governance from disruption from outside; and to control its borders’ (Watson Citation2008, 5). This definition is broad enough to go beyond matters of international war and borders, yet sufficiently narrow to exclude the human and planetary security impacts of climate change. These are beyond the scope of this article and are already covered by other studies (see 'Introduction'). However, one should keep in mind that this is ‘merely’ an operational definition as the meaning of national security shifts over time and across contexts. Particularly when it comes to climate change, some scholars argue that any useful understanding of national security should contain elements of human and planetary security (see 'Introduction').Footnote4

Which aspects (or dimensions) of this definition of national security are affected by climate change? In his ground-breaking study on the USA, Busby (Citation2008) identifies two clusters of threats climate change poses for national securityFootnote5, with each cluster containing a number of distinct threats.

The first cluster includes direct threats climate change poses to the ‘homeland’, including three threats less relevant in the Australian context: threats to the existence of the country (this only applies to small island states heavily affected by sea-level rise), threats to the seat of government (Canberra is inland and will not become uninhabitable in the next few decades), and significant adverse changes to a country’s borders (climate change is unlikely to affect Australia’s maritime boundaries within this study’s timeframe). The remaining four direct threats to homeland deserve closer attention and will be discussed in further detail below: threats to the monopoly of force, disruption of critical infrastructure (particularly related to energy, food and water), mass loss of life (due to extreme climate events) that undermine the legitimacy of the government, and a massive (climate-related) influx of migrants from other countries. Based on concerns articulated by Barrie et al. (Citation2015) and McDonald (Citation2021a), I add a fifth category: challenges to defence capacities and infrastructure.

The second cluster refers to climate-related threats to countries of high strategic importance. In this context, Busby (Citation2008) discusses several points relevant for a major global power but less important for a middle power like Australia. A case in point are threats to foreign military bases. These are key for the global projection of military strength by the USA, but strategically less important for Australia, which only maintains three foreign bases. However, there are three threats outlined by Busby which are also key to Australia’s geo-strategic context and will be analysed in further detail below: political instability in strategically important countries, reduced capabilities of key strategic partners, and widespread political-economic instability in areas of high economic relevance.

Before further analysing these national security threats, the article will briefly outline the predicted impacts of climate change in Australia.

Climate change in Australia

In order to assess the impacts of climate change in Australia, I draw primarily on the two most authoritative sources on this issue: the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC Citation2021, 1805–1811) and the most recent State of Climate update by the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation and the Australian Bureau of Meteorology (CSIRO and BoM Citation2020).

Climate change is already visible in Australia. Average temperatures have increased by 1.44 °C relative to the pre-industrial period. Ocean temperatures have risen by even more, facilitating (along with other stressors) mass coral bleaching events like those seen at the Great Barrier Reef in 2016, 2017, 2020 and 2022. Precipitation is also declining and becoming more erratic, with the total amount of rainfall having decreased by 16% in Southwestern Australia and by 12% in Southeastern Australia since 1970. In the same time period extreme (heavy) rainfall events have become 10% more common in some regions. While cyclone frequency has decreased in recent decades, studies find a trend towards more frequent and intense bushfires and floods (van Oldenborgh et al. Citation2021).

The average temperature in Australia is predicted to increase by roughly another 1.1 °C, however some estimates predict and increase as high as 1.5 °C by the middle of the century. This implies a cumulative warming of around 2.5 °C relative to pre-industrial levels, notably above the 1.5 °C mark most scientists have recommended as the global limit (and the 2.0 °C mark, already implying some significant risks). Consequentially, very hot days (above 35 °C) will become increasingly more common around the country, particularly in the northern regions (CSIRO and BoM Citation2015). Simultaneously, drought frequency is predicted to continue increasing in frequency across all parts of Australia by 2050 as a result of both reduced precipitation and increased temperature, with the southwestern region predicted to have the greatest decline in rainfall (Coppola et al. Citation2021). Precipitation declines will also negatively affect groundwater recharge rates and river runoff.

A climate-changed Australia will also experience more frequent and intense fires and floods by the middle of the century. Fire-prone weather conditions will become more frequent and extreme with rising temperatures and decreased rainfall. By 2030, the countrywide McArthur Forest Fire Danger Index will be more than 8% higher than it was in 1995 even under a conservative climate change scenario (CSIRO and BoM Citation2015, 140). Furthermore, models predict an increase in flood frequency and intensity associated with heavy precipitation events and rising sea levels (see below), particularly in northern and eastern Australia (Hirabayashi et al. Citation2013). A recent study found evidence that with each 1° C of global warming, the risk of mega flooding events, such as those in Queensland and New South Wales in 2022, nearly doubles (Rice et al. Citation2022). Predictions for storms are less certain and contradictory. The number of cyclones is set to decrease, but several models anticipate a higher intensity of tropical cyclones (Kumar, Mishra, and Ganguly Citation2015).

Finally, conservative estimates show sea levels around Australia rising by 40-90 cm by the end of the century. This implies that before 2050, current 1-in-100 years high water level events will become two to five times more likely (Vitousek et al. Citation2017), while sandy shorelines in most parts of Australia with retreat by 50–80 metres (relative to 2010) if no adaptation measures are conducted (Vousdoukas et al. Citation2020).

Does climate change impact Australia’s national security?

Direct threats to Australia

Climate change is highly unlikely to pose a threat to the monopoly of force of the Australian government within the timeframe considered here. Research largely agrees that climate change will not increase the risk of international war for the foreseeable future, as even contentious transboundary water issues are usually addressed by non-violent means. Likewise, while climate change can increase the likelihood of armed conflict within states, it only does so if pre-existing risk factors like weak institutions, a history of violence, or low levels of human development are present (von Uexkull and Buhaug Citation2021; Ide et al. Citation2020). Australia is hence unlikely to experience a climate-related (or any kind of) civil war in the next few decades.

There are two further, yet minor threats to the monopoly of force to be considered. The first one is international fishing disputes. The IPCC (Citation2022, 1599–1607) predicts that ocean warming and acidification will result in lowered fishing potential and a southward shift of fish stocks (towards colder waters). This could result in more (severe) international fishing disputes and more illegal intrusions of fishing vessels from other countries into Australia’s territorial waters. The latter possibility cannot be discounted and would require additional monitoring efforts by the Australian Navy. This is particularly so because in countries like Indonesia or Papua New Guinea fishing is an important source of livelihoods and local fish stocks are projected to decline.Footnote6 However, large-scale international fishing disputes are still unlikely to occur. From 1974 to 2016 Australia has only been involved in seven international fishing conflicts, most of which were of low intensity with the last conflict dating back to 2008 (Spijkers et al. Citation2019).

A climate-related increase in crime and violent extremism is the second minor threat to the monopoly of force. There is widespread agreement that climate change will have adverse impacts on Australia’s economy, including considerable GDP reductions and job losses in mining (Pizarro et al. Citation2017), tourism (Swann and Campbell Citation2016) and agriculture (IPCC Citation2022, 1610–1611). Analysts have articulated concerns that the resulting unemployment and poverty can in turn drive extremism. However, a recent study by Cherney et al. (Citation2022) finds socio-economic characteristics to be a weak predictor of youth radicalisation.

A climate change-related increase in crime is markedly a more realistic scenario because heat-stressed people tend to display more aggressive behaviour and heat increases the opportunities for property crimes (e.g. because more people are outdoors more often). Stevens et al. (Citation2019) find that in New South Wales, a one degree rise in mean summer temperatures corresponds with a 7% increase in reported assaults. A not-yet peer-reviewed study even suggests that by mid-century, the Australian police force would need to grow by 11.2% to deal with the additional number of violent and property crimes (Awaworyi et al. Citation2022). While this poses no threat to the Australian government’s monopoly of force, such a development would require significant additional resources in the domestic security sector.

As outlined above, Australia will face a higher frequency and intensity of heatwaves, bushfires, droughts and flood events. Such disasters will come with immense human and economic costs. Between 1987 and 2016, for example, they caused at least 971 deaths and an average annual economic damage of $18.2 billion (IPCC Citation2022, 1617–1618). Can such losses undermine the legitimacy of the government as an institution (and not just support for specific parties or politicians)?

The limited evidence available on this question suggests that this is a possible, yet unlikely scenario. Trust in and support for governments after disasters can either increase or decline, depending on how the population perceive the government’s disaster management. However, such an effect is mostly confined to leading politicians and how they handle the emergency (Katz and Levin Citation2016). Data from the OECD (Citation2021) show that trust in government as an institution declined in Australia in the years after the 2011 Queensland floods (−7.9%) and the 2019/2020 bushfires (−2.2%), but there is no evidence for a long-term trend. Furthermore, the disaster type most influenced by climate change, heatwaves, is hardly suitable for politicisation due to its often silent, invisible and dispersed impacts.

There is no doubt that climate change will cause disruptions to critical infrastructure in Australia. Sea-level rise is an important cross-cutting threat as it will increase the risk of coastal floods, particularly when combined with high tides and storms. According to CSIRO and BoM (Citation2015, 153–157) significant parts of Australia’s key infrastructure are critically close to the coastline, many of which will require significantly enhanced protection from inundation and shoreline recession prior to the middle of the century (see ). Likewise, sea-level rise, higher temperatures, more extreme rainfall events, floods and wildfires will make the maintenance of transport infrastructure more difficult, affecting thousands of kilometres of roads and rail-lines (Taylor and Philp Citation2015). A case in point is the 2022 disruption of a crucial rail line in Southern Australia due to a major flood, which resulted in a severe shortage of some food items and other goods in Western Australia (Towie Citation2022).

Table 1. Coastal infrastructure threatened by climate impacts until 2050 (based on: Steffen et al. Citation2019, 18).

Climate change further affects the supply, transition, and demand aspects of energy infrastructure. While hard to quantify, climate change will pose significant risks to energy production, for instance storms forcing wind power turbines to shut down, droughts reducing hydropower production, and the cooling of power plants becoming more difficult. Extreme events like bushfires, floods and storms already negatively affect power lines. Furthermore, by 2050, demand for energy (and particularly for air-conditioning) for buildings will be far greater than now in all major cities except for Hobart and Melbourne (Wang, Chen, and Ren Citation2010). Given the generally high resilience of the Australian energy infrastructure, these developments will mostly become critical during specific time periods, particularly when several stressors coincide. For instance, if high temperatures have increased demand for cooling at the same time as power lines are switched off because of fire-prone weather and an the associated drought affects the cooling of coal plants (AEMO Citation2020).

Finally, research predicts severe disruptions of food-related infrastructure and across the agricultural sector due to climate change. Heat and drought related stress will adversely affect a wide range of crops (including staple foods like wheat) as well as livestock and dairy production (Dreccer et al. Citation2018; Nidumolu et al. Citation2014). By 2050, Australia is will be facing climate-related agricultural loss of over $200 billion (Steffen et al. Citation2019), as well as wheat yield declines of up to 30% in some regions (IPCC Citation2022, 1584). However, with Australia exporting currently around 70% of its agricultural production (ABARES Citation2020), climate change is unlikely to affect food security in Australia in the near to medium future.

Climate change poses serious challenges to defence capacities and infrastructure of Australia in at least three ways. First, as Barrie et al. (Citation2015) point out, the Australian Defence Force (ADF) is dependent on civilian infrastructure for electricity, water, roads, rails and communication. This means that the general impacts of climate change on infrastructure will affect military actors as well. For instance, the Tanami Road (connecting Alice Springs to the Kimberley) is considered crucial by several strategic planners in the case that Australia would need to engage in a regional military conflict. Even if the road would be sealed, it remains highly vulnerable to extreme climate events like heat waves and floods (O'Connor Citation2022). Military-relevant industrial infrastructure will also be increasingly endangered by sea-level rise (DCCEE Citation2011).

Second, climate change also poses additional challenges for military infrastructure. The risk of equipment malfunctioning, not being available or requiring additional maintenance increases with more frequent and intense heat waves. This is particularly so for the already very warm northern areas of Australia where several key ADF bases are located (Thomas Citation2011). This includes, for example, the overheating of equipment or the enhanced storage requirements for heat-sensitive ammunition. In its submission to the 2017 Senate inquiry, the Department of Defence (Citation2017, 7) further argues that ‘a large number of key Defence installations are at or just above sea level and much of Australia's infrastructure is aging so there is an increased likelihood of climate change impacting Defence base operations in the short to medium term.’ According to Tranter (Citation2019), in 2013, the same department classified 13 out of 38 Defence sites assessed as experiencing high or very high risks due to sea-level rise, flooding and coastal erosion beyond 2040. A recent update to this report is still classified (illustrating considerable information uncertainties around this issue) yet is expected to predict even more severe outcomes. This adds to higher temperatures complicating outdoor training operations and climate change having adverse impacts on supply chains (see section 'Threats to countries of high strategic importance').

Third, climate change will increasingly stretch the capacity of the ADF. Domestically, the ADF is a major responder to climate-related disasters and on average assists with more than thirty emergencies per year, including the large 2022 floods in New South Wales, Queensland and Victoria. In addition, the ADF is an important actor for Australia’s substantive provision of relief after major disasters in the Asia-Pacific region, including the 1997 drought in Papua New Guinea, cyclone Haiyan in the Philippines (2013), and cyclone Winston in Fiji in 2016 (Barrie et al. Citation2015; DFAT Citation2017). With the frequency and intensity of such disasters predicted to increase in the coming decades, the manpower and resources of the ADF will be stretched thin (or, alternatively, the Australian government will face a loss of legitimacy and reputation if it can no longer provide large-scale disaster relief to its own population and/or partner countries). Should the intrusion of illegal fishing vessels into Australian territorial waters occur more often (see above), additional monitoring capacities of the Royal Australian Navy will be required as well (Layton Citation2021).

It is important to keep in mind that because the ADF is generally well-resourced, climate change impacts are unlikely to affect routine operational procedures prior to 2050. However, the three threats discussed above could turn critical if several major disasters (within Australia and/or in partner countries) coincide and particularly if Australia were to engage in a regional military conflict. In the latter scenario, even relatively small disturbances of infrastructure and capacities could translate into military disadvantages (Thomas Citation2011).

Finally, a massive (climate-related) influx of migrants from other countries into Australia is very unlikely before the middle of the century for various reasons. First, Australia is an island country with well-guarded borders and strict immigration policies, making unwanted immigration very difficult. Second, particularly among those groups most vulnerable to climatic extremes (e.g. because they rely on subsistence agriculture) and hence most dependent on migration as an adaptation strategy (e.g. because several harvest seasons fail), climate change will likely produce ‘trapped populations’. Put differently, migration is expensive, and poor households who have lost assets and income due to droughts or storms become increasingly incapable of affording it, particularly when it comes to long-distance and/or international migration (Koubi et al. Citation2022). In line with this, and third, a large empirical literature shows that climate-related migration takes place overwhelmingly over short distances and/or within countries (Groth et al. Citation2020; Hoffmann et al. Citation2020), making Australia an unlikely destination for such migrants.

Threats to countries of high strategic importance

An in-depth analysis of each country of (potential) strategic relevance to Australia is beyond the scope of this article. However, the general literature on the topic, country-specific empirical analyses and available statistics allow me to make reliable statements on each of the three threats considered.

Will climate change trigger or facilitate political instability in strategically important countries? In line with the Department of Defence’s (Citation2020) recent Strategic Update, I focus on South and Southeast Asia as well as the Pacific Island countries. Large-scale or militarised international conflicts related to climate change are unlikely to occur in the first half of the century. Research has repeatedly shown that climate extremes, disasters and resource scarcity have a limited effect on conflict risks between states (von Uexkull and Buhaug Citation2021). Of gravest concern in this context are disputes over water along the Indus River (India-Pakistan) and the Mekong River (China-Myanmar-Laos-Vietnam–Cambodia). However, even here, cooperation has been more prevalent than conflict in the past and emerging conflicts have been resolved through diplomatic channels (Tir and Stinnett Citation2012; Po and Primiano Citation2021). International fishing conflicts in the region are also too low-profile to trigger large-scale confrontations between countries (Spijkers et al. Citation2019).

The picture looks different when focussing on armed conflict within states, such as communal violence, terrorism, and civil wars. Scholars now largely agree that climate-related extreme events like droughts or storms increase the risks of such conflicts, even though they are not the primary conflict driver (Mach et al. Citation2019).Footnote7 Empirical studies also find evidence for a link between disasters and armed conflict in several countries across the Indo-Pacific, including India (e.g. Gawande, Kapur, and Satyanath Citation2017), Indonesia (e.g. Gatti, Baylis, and Crost Citation2021), the Philippines (e.g. Eastin Citation2018) and the Solomon Islands (e.g. Boege Citation2022).

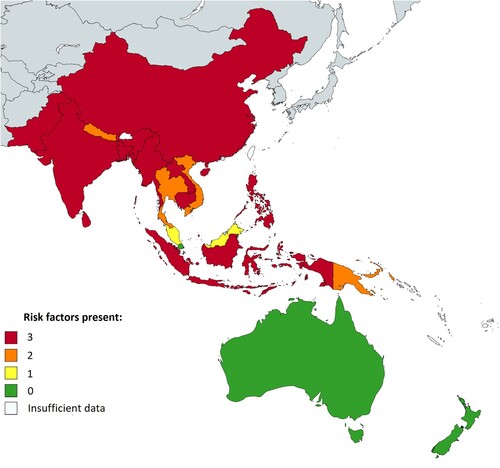

Furthermore, scholars have detected three key factors that make a country vulnerable to climate-related armed conflict: a high economic dependence on agriculture, the political exclusion of ethnic groups, and low levels of human development (Ide et al. Citation2020; Mach et al. Citation2019). Using the thresholds of Ide et al. (Citation2020), shows how many of these risk factors are present in various countries of the Asia-Pacific region. The fact that 79% of the countries are characterised by two or all three risk factors further demonstrates that climate-related, intrastate political instability is a real possibility in the coming decades.

Figure 1. Distribution of the three risk factors for climate-conflict links across the Asia-Pacific region (data on most Pacific Island states are not available)

In theory, climate change can result in reduced capabilities of key strategic partners, for instance by reducing economic growth, burdening their military with disaster response tasks, or disrupting key infrastructure. In this article, I consider climate change impacts on two groups of countries.

First, key international strategic partners of Australia include the USA and the UK (via the AUKUS partnership) as well as Japan and South Korea (via bilateral Special/Comprehensive Strategic Partnerships). While all four countries will face adverse climate change impacts (IPCC Citation2022), they are also very resilient to these changes due to their strong economies, high technological capacities and moderate climate. Phillis et al. (Citation2018) developed an integrated model that measures how climate secure a country is based on indicators for exposure, sensitivity, and adaptive capacity, attributing scores between 0 (very climate insecure) and 1 (highly climate secure) to 187 countries. In their analysis, the UK (16th), the USA (18th), South Korea (24th) and Japan (26th) rank very high. This makes it unlikely that their military or economic capabilities will be significantly reduced by the middle of the century unless they are severely undermined by other developments, such as a major geopolitical conflict. Qualitative analyses of these countries corroborate this assessment (e.g. Busby Citation2008; Kameyama et al. Citation2020).

The picture changes when focussing on strategic partners in South and Southeast Asia as well as the Pacific. In this region, Australia has close ties with New Zealand as well as (Comprehensive) Strategic Partnerships with India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Papua New Guinea, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam. Of these nine countries, only New Zealand ranks high as climate secure (7th), and with the exception of Malaysia, all other countries can be considered climate insecure according to Phillis et al. (Citation2018) (see ). Further studies suggest that climate change could result in political instability (e.g. Gawande, Kapur, and Satyanath Citation2017), internal migration flows (e.g. Nguyen Citation2021), and economic disruptions (e.g. IPCC Citation2022, 1490–1494) in these countries in the near future. Likewise, Australia signed a regional security declaration (the Boe Declaration) with 14 Pacific Island countries in 2018 and conceives them as strategically highly important.Footnote8 These countries are among the most vulnerable to climate change and could face widespread internal migration and economic instability over the coming decades (Boege Citation2022).

Table 2. Climate security of Australia’s key strategic partners based on Phillis et al. (Citation2018).

The exact impact of climate change on the total economic and military resources of regional partner countries in the Asia-Pacific region remains unclear and hard to quantify. However, there is a real possibility that climate change will significantly undermine their capabilities.

Finally, will climate change facilitate widespread political-economic instability in areas of high economic relevance? In this study, I focus on three areas: major trading partners of Australia, key countries for global supply chains, and major oil-producing states.

lists the ten most important two-way trading partners of Australia (together accounting for over 70% of the total trade volume) (DFAT Citation2021, 16), how climate secure they are (Phillis et al. Citation2018), and their categorisation by the Fragile States Index (Fund for Peace Citation2022). Overall, Australia’s major trading partners are rather climate secure, with six countries among the top twenty percent and only two in the bottom half of the ranking. Likewise, eight of the ten countries are characterised as stable or even sustainable, only one (India) crosses the serious warning threshold, and none is on the lowest (‘alert’) level of state fragility. Studies of climate-related political instability have so far also only identified India as a country of concern (e.g. Gawande, Kapur, and Satyanath Citation2017). Widespread, climate-related political-economic instability among Australia’s major trading partners is hence a very unlikely scenario for the foreseeable future.

Table 3. Climate security and state fragility of Australia’s major two-way trading partners.

Dangers to global supply chains are much more concerning. As became clear during the COVID-19 pandemic, Australia is strongly dependent on the import of several categories of goods to maintain industrial production and civilian infrastructure. Examples include vehicles (11.86% of the total import value), various electrical and mechanical products (6.43%), medical products (3.8%), broadcasting equipment (3.16%). and computers (2.86%) (OECD Citation2022). Many of these products are imported from and produced in the southwestern industrial zone of China. In mid-2022, an intense heatwave in this region resulted in skyrocketing demand for electricity, in response to which provincial authorities shut down several factories to prevent a collapse of the power grid (Moore Citation2022). Southwestern China will also see a remarkable increase in flood frequency and storm intensity over the coming decades (Fang et al. Citation2020). This could have severe follow-up effects on global supply chains.

Finally, oil is a crucial commodity for Australia’s military infrastructure, industrial production and personal use. The recent Russian invasion of the Ukraine and the subsequent rise in global oil prices, for instance, have created severe inflation pressures in Australia, while almost all ADF vehicles, ships and planes run on oil-based fuel. Climate-related political instability of major oil producers is hence an area of concern.

Empirical evidence for this concern is mixed. Of the 18 countries that produced more than one million barrels of oil per day in 2021 (EIA Citation2022), several are politically very stable and rather climate secure, including Canada, Kazakhstan, Norway and the USA. Other major producers, by contrast, face both pre-existing political instability and a very high vulnerability to climate change, in particular Angola, Iraq, Libya and Nigeria (Phillis et al. Citation2018; Fund for Peace Citation2022). This is in line with recent studies that have found extreme climatic events increase the risk of violent conflict among oil-producing states in Western Africa and the Middle East (Helman, Zaitchik, and Funk Citation2020; Ide et al. Citation2021). However, there is still exists some scepticism about such a link (Daoust and Selby Citation2022). As well as this, the five biggest oil producersFootnote9 are unlikely to experience climate-related instability. The political-economic relevance of oil will also decline relative to renewable energy sources (see section 'Discussion and conclusion').Footnote10

Discussion and conclusion

Based on different understandings of security, a variety of climate security debates have emerged over the past years (Diez, von Lucke, and Wellmann Citation2016; Thomas Citation2017; McDonald Citation2015). Research has already demonstrated that climate change is a threat to planetary security (McDonald Citation2021b) and to human security in Australia (van Oldenborgh et al. Citation2021). However, despite similar assessments for other countries and a series of policy reports on the topic, a systematic assessment of climate change impacts on Australia’s national security based on (mostly peer-reviewed) scientific information is still lacking. The analyses presented above addresses this gap, using a clear definition of national security and focussing on the time period prior to 2050.

summarises the main findings of this analysis. When it comes to direct threats to the Australia, domestic political instability due to climate change is highly unlikely. Concerns about mass migration to Australia, which are common in political and public debates, also have little scientific basis. However, climate change will very likely undermine Australia’s national security by disrupting critical infrastructure and by challenging the capacities of defence forces. These impacts will matter most if (i) several severe climate-related disasters occur simultaneously (within Australia and/or its immediate region) or (ii) Australia was already involved in a major international conflict. When considering countries of high strategic importance to Australia, climate change-related international conflicts as well as adverse effects on major trading partners or key international allies are minor concerns. By contrast, climate change can increase the risk of domestic political instability and reduce the capabilities of partner countries in the Asia-Pacific region. The impact of climate change on important supply chains is also a risk.

Table 4. Climate change-related threats to Australia’s national security.

There are other potential impacts of climate change on Australia’s national security beyond those discussed here. For instance, its high CO2 emissions and lack of action to mitigate climate change could lower the international reputation of Australia, particularly among climate insecure countries in South(east) Asia and the Pacific. Such a loss in soft power would reduce Australia’s geopolitical influence (Durrant, Bradshaw, and Pearce Citation2021, 23–24). As of yet, there is too little empirical evidence to make a call on this issue. Likewise, solar geoengineering could worsen international tensions, for instance by causing disputes about the ‘right’ amount of temperature control and adverse side effects. However, large-scale geoengineering is unlikely to happen in the coming decades and empirical evidence about its security implications is hence very limited (Lockyer and Symons Citation2019). A rapid transition towards renewable energy could also amplify geopolitical competition over key minerals like lithium and rare earths (even though some analysists remain sceptical about this prospect, see Overland Citation2019). One should also note that this analysis did not include human or planetary security effects.

Another area for future research includes the potential national security benefits that arise from climate change (despite its adverse impacts on human and planetary security). To discuss just one example: The literature on disaster diplomacy has shown that countries can forge closer relations by providing aid to each other after extreme events, even though this effect is often temporary and never the main reason for improved relations (Kelman Citation2012). Already by now, Australia is a major provider a disaster relief in the Asia-Pacific region, for instance when it sent $35 million as well as DFAT, ADF and medical personnel to Fiji after cyclone Winston in 2016 (DFAT Citation2017, 13). With the number and frequency of such events predicted to increase, more opportunities (and more obligations) for disaster diplomacy will emerge.

Finally, it is important to highlight that there are two policy challenges ahead. First, Australia (just as other countries) needs to step up its efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and facilitate international negotiations in order to reduce the human, national and planetary security impacts of climate change. However, a certain amount of global warming and its associated consequences will occur even under very ambitious mitigation scenarios. Therefore, and second, Australia (as all other countries) needs to prepare for dealing with the adverse impacts of climate change. In the national security realm, critical infrastructure, defence capabilities and impacts on key regional partners are the areas of highest concern. Addressing these two challenges simultaneously is key to achieving a climate-secure future.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Tobias Ide

Tobias Ide is Senior Lecturer in Politics and International Relations at Murdoch University Perth. He holds an ARC Discovery Early Career Research Award (DECRA) and has published widely on climate change and security, including in International Affairs, Journal of Peace Research, Nature Climate Change, and World Development.

Notes

1 I thank the editors, two anonymous reviewers, and Luke Derrick for helpful comments on previous versions of this article.

2 To do so, however, they must be conceived of as providing one part of the puzzle rather than a comprehensive perspective on security (Glasser Citation2022).

3 These were retrieved by searches in the Scopus database, forward and backward snowball sampling of citations and references, and conversations with other scholars working on the topic.

4 In Australia, even a group of retired senior military leaders recently argued that climate security assessments by the government should include human security and climate change mitigation aspects (ASLCG Citation2022).

5 Busby (Citation2008, 480) proposes a slightly wider definition of security, resulting in the inclusion of a third cluster: ‘high-stakes international crises’ with enormous human security implications. I exclude this cluster as it is incompatible with my (narrower) definition of security.

6 Climate change will also undermine alternative livelihood strategies like agriculture in these countries.

7 Possible pathways include competition over scarce renewable resources, grievances due to lower economic performance, state weakness, and better recruitment opportunities among climate-deprived individuals.

8 This is also illustrated by recent concerns about increasing Chinese influence in the region.

9 USA, Saudi Arabia, Russia, Canada and China.

10 Even though military mobility will continue to strongly depend on oil (Bigger and Neimark Citation2017).

References

- ABARES. 2020. Analysis of Australian Food Security and the COVID-19 Pandemic. Canberra: ABARES.

- AEMO. 2020. 2020 Integrated System Plan, Appendix 8: Resilience and Climate Change. Perth: AEMO.

- Albanese, Anthony. 2022. “My Plan: National Security.” https://anthonyalbanese.com.au/my-plan/national-security-2 (15/09/2022).

- ASLCG. 2022. “A Joint Letter to the Australian Government & the Office of National Intelligence.” https://www.aslcg.org/joint-statement/ (02/01/2023).

- Awaworyi Churchill, Sefa Russell Smyth, and Trong-Anh Trinh. 2022. “Crime, weather and climate change in Australia.” https://www.researchgate.net/publication/360500594_Crime_Weather_and_Climate_Change_in_Australia (27/10/2022).

- Barrie, Chris, Will Steffen, Alix Pearce, and Michael Thomas. 2015. Be Prepared: Climate Change, Security, and Australia's Defence Force. Potts Point: Climate Council of Australia.

- Bigger, Patrick, and Benjamin D. Neimark. 2017. “Weaponizing Nature: The Geopolitical Ecology of the US Navy’s Biofuel Program.” Political Geography 60 (1): 13–22. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2017.03.007.

- Boege, Volker. 2022. “Climate Change, Conflict and Peace in the Pacific: Challenges and a Pacific way Forward.” Peace Review 34 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1080/10402659.2022.2023424.

- Busby, Joshua W. 2008. “Who Cares About the Weather?: Climate Change and U.S. National Security.” Security Studies 17 (3): 468–504. doi:10.1080/09636410802319529.

- Cherney, Adrian, Emma Belton, Siti Amirah Binte Norham, and Jack Milts. 2022. “Understanding Youth Radicalisation: An Analysis of Australian Data.” Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression 14 (2): 97–119. doi:10.1080/19434472.2020.1819372.

- Coppola, Erika, Francesca Raffaele, Filippo Giorgi, Graziano Giuliani, Gao Xuejie, et al. 2021. “Climate Hazard Indices Projections Based on CORDEX-CORE, CMIP5 and CMIP6 Ensemble.” Climate Dynamics 57 (5): 1293–1383. doi:10.1007/s00382-021-05640-z.

- CSIRO, and BoM. 2015. Climate Change in Australia: Projections for Australia's NRM Regions. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

- CSIRO, and BoM. 2020. State of the Climate 2020. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

- Daoust, Gabrielle, and Jan Selby. 2022. “Understanding the Politics of Climate Security Policy Discourse: The Case of the Lake Chad Basin.” Geopolitics, 1–38. doi:10.1080/14650045.2021.2014821

- DCCEE. 2011. Climate Change Risks to Coastal Buildings and Infrastructure: A Supplement to the First Pass National Assessment. Canberra: DCCEE.

- Department of Defence. 2016. 2016 Defence White Paper. Canberra: Australian Government.

- Department of Defence. 2017. Defence Submission to the Senate Inquiry on the Implications of Climate Change for Australia's National Security. Canberra: DoD.

- Department of Defence. 2020. 2020 Defence Strategic Update. Canberra: Australian Government.

- Department of Home Affairs. 2022. “National Security.” https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/about-us/our-portfolios/national-security (12/09/2022).

- DFAT. 2017. DFAT Submission to the Senate Inquiry on the Implications of Climate Change for Australia's National Security. Canberra: DFAT.

- DFAT. 2021. Trade and Investment at a Glance 2021. Canberra: DFAT.

- Diez, Thomas, Franziskus von Lucke, and Zehra Wellmann. 2016. The Securitisation of Climate Change: Actors, Processes and Consequences. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Dreccer, M. Fernanda, Justin Fainges, Jeremy Whish, Francis C. Ogbonnaya, and Victor O. Sadras. 2018. “Comparison of Sensitive Stages of Wheat, Barley, Canola, Chickpea and Field pea to Temperature and Water Stress Across Australia.” Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 248 (1): 275–294. doi:10.1016/j.agrformet.2017.10.006.

- Durrant, Cheryl, Simon Bradshaw, and Alix Pearce. 2021. Rising to the Challenge: Addressing Climate and Security in our Region. Potts Point: Climate Council of Australia.

- Eastin, Joshua. 2018. “Hell and High Water: Precipitation Shocks and Conflict Violence in the Philippines.” Political Geography 63 (1): 116–134. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2016.12.001.

- EIA. 2022. “Petroleum and Other Liquids.” https://www.eia.gov/international/data/world (04/11/2022).

- FADTRC. 2018. Implications of Climate Change for Australia’s National Security. Canberr: Senate of the Commonwealth of Australia.

- Fang, Jiayi, Daniel Lincke, Sally Brown, Robert J. Nicholls, Claudia Wolff, et al. 2020. “Coastal Flood Risks in China Through the 21st Century – an Application of DIVA.” Science of The Total Environment 704 (1): 135311. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.135311.

- Farbotko, Carol. 2018. “Climate Change and National Security: An Agenda for Geography.” Australian Geographer 49 (2): 247–253. doi:10.1080/00049182.2017.1385119.

- Fund for Peace. 2022. Fragile States Index: 2022 Annual Report. Washington DC: Fund for Peace.

- Gatti, Nicolas, Kathy Baylis, and Benjamin Crost. 2021. “Can Irrigation Infrastructure Mitigate the Effect of Rainfall Shocks on Conflict? Evidence from Indonesia.” American Journal of Agricultural Economics 103 (1): 211–231. doi:10.1002/ajae.12092.

- Gawande, Kishore, Devesh Kapur, and Shanker Satyanath. 2017. “Renewable Natural Resource Shocks and Conflict Intensity.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 61 (1): 140–172. doi:10.1177/0022002714567949.

- Glasser, Robert. 2022. “Foreword.” In The Geopolitics of Climate and Security in the Indo-Pacific, edited by Robert Glasser, Cathy Johnstone, and Anatasia Kapetas, v–vi. Canberra: ASPI.

- Greaves, Wilfrid. 2021. “Climate Change and Security in Canada.” International Journal 76 (2): 183–203. doi:10.1177/00207020211019

- Groth, Juliane, Tobias Ide, Patrick Sakdapolrak, Endeshaw Kassa, and Kathleen Hermans. 2020. “Deciphering Interwoven Drivers of Environment-Related Migration – A Multisite Case Study from the Ethiopian Highlands.” Global Environmental Change 63 (1): 102094. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2020.102094.

- Helman, David, Benjamin F. Zaitchik, and Chris Funk. 2020. “Climate has Contrasting Direct and Indirect Effects on Armed Conflicts.” Environmental Research Letters 15 (10): 104017. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/aba97d.

- Hirabayashi, Yukiko, Roobavannan Mahendran, Sujan Koirala, Lisako Konoshima, Dai Yamazaki, et al. 2013. “Global Flood Risk Under Climate Change.” Nature Climate Change 3 (9): 816–821. doi:10.1038/nclimate1911.

- Hoffmann, Roman, Anna Dimitrova, Raya Muttarak, Jesus Crespo Cuaresma, and Jonas Peisker. 2020. “A Meta-Analysis of Country-Level Studies on Environmental Change and Migration.” Nature Climate Change 10 (10): 904–912. doi:10.1038/s41558-020-0898-6.

- Ide, Tobias, Michael Brzoska, Jonathan F. Donges, and Carl-Friedrich Schleussner. 2020. “Multi-method Evidence for When and how Climate-Related Disasters Contribute to Armed Conflict Risk.” Global Environmental Change 62 (1): 102063. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2020.102063

- Ide, Tobias, Juan Miguel Rodriguez Lopez, Christiane Fröhlich, and Jürgen Scheffran. 2021. “Pathways to Water Conflict During Drought in the MENA Region.” Journal of Peace Research 58 (3): 568–582. doi:10.1177/0022343320910777.

- IPCC. 2021. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- IPCC. 2022. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kameyama, Yasuko, Keisuke Nansai, Gen Sakurai, Kentaro Tamura, Seiichiro Hasui, et al. 2020. Compound Risks of Climate Change: Implications to Japanese Economy and Society. Tokyo: NIES.

- Katz, Gabriel, and Ines Levin. 2016. “The Dynamics of Political Support in Emerging Democracies: Evidence from a Natural Disaster in Peru.” International Journal of Public Opinion Research 28 (2): 173–195. doi:10.1093/ijpor/edv010.

- Kelman, Ilan. 2012. Disaster Diplomacy: How Disasters Affect Peace and Conflict. London: Routledge.

- Koubi, Vally, Lena Schaffer, Gabriele Spilker, and Tobias Böhmelt. 2022. “Climate Events and the Role of Adaptive Capacity for (im-)Mobility.” Population and Environment 43 (3): 367–392. doi:10.1007/s11111-021-00395-5.

- Kumar, Devashish, Vimal Mishra, and Auroop R. Ganguly. 2015. “Evaluating Wind Extremes in CMIP5 Climate Models.” Climate Dynamics 45 (1): 441–453. doi:10.1007/s00382-014-2306-2.

- Layton, Peter. 2021. “Preparing Australia to Respond to Disasters – At Home and Abroad.” https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/preparing-australia-respond-disasters-home-abroad (30/12/2022).

- Lockyer, Adam, and Jonathan Symons. 2019. “The National Security Implications of Solar Geoengineering: An Australian Perspective.” Australian Journal of International Affairs 73 (5): 485–503. doi:10.1080/10357718.2019.1662768.

- Mach, Katharine J., Caroline M. Kraan, W. Neil Adger, Halvard Buhaug, Marshall Burke, et al. 2019. “Climate as a Risk Factor for Armed Conflict.” Nature 571 (7764): 193–197. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1300-6.

- McDonald, Matt. 2015. “Climate Security and Economic Security: The Limits to Climate Change Action in Australia?” International Politics 52 (4): 484–501. doi:10.1057/ip.2015.5.

- McDonald, Matt. 2021a. “After the Fires? Climate Change and Security in Australia.” Australian Journal of Political Science 56 (1): 1–18. doi:10.1080/10361146.2020.1776680.

- McDonald, Matt. 2021b. Ecological Security: Climate Change and the Construction of Security. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Moore, Scott. 2022. “What China’s Heatwave From Hell Tells Us About the Future of Climate Action.” https://www.newsecuritybeat.org/2022/09/chinas-heatwave-hell-tells-future-climate-action/ (15/09/2022).

- Moran, Daniel, ed. 2011. Climate Change and National Security: A Country-Level Analysis. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press.

- NATO. 2021. “NATO Climate Change and Security Action Plan.” https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_185174.htm (15/09/2022).

- Nguyen, Cuong Viet. 2021. “Do Weather Extremes Induce People to Move? Evidence from Vietnam.” Economic Analysis and Policy 69 (1): 118–141. doi:10.1016/j.eap.2020.11.009.

- Nidumolu, Uday, Steven Crimp, David Gobbett, Alison Laing, Mark Howden, et al. 2014. “Spatio-temporal Modelling of Heat Stress and Climate Change Implications for the Murray Dairy Region, Australia.” International Journal of Biometeorology 58 (6): 1095–1108. doi:10.1007/s00484-013-0703-6.

- O'Brien, Karen, and Jon Barnett. 2013. “Global Environmental Change and Human Security.” Annual Review of Environment and Resources 38 (1): 373–391. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-032112-100655.

- O'Connor, Ted. 2022. “Military Analysts Call for Greater Focus on Sealing the Vehicle-Killing Tanami Road.” https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-09-16/tanami-road-defence-strategy-focus-military-analysts-say/101439574 (16/09/2022).

- OECD. 2021. “Trust in Government.” https://data.oecd.org/gga/trust-in-government.htm (27/10/2022).

- OECD. 2022. “Trade Flow Profile: Australia.” https://oec.world/en/profile/country/aus?yearlyTradeFlowSelector=flow1 (03/11/2022).

- Overland, Indra. 2019. “The Geopolitics of Renewable Energy: Debunking Four Emerging Myths.” Energy Research & Social Science 49 (1): 36–40. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2018.10.018.

- Phillis, Yannis A., Nektarios Chairetis, Evangelos Grigoroudis, Fotis D. Kanellos, and Vassilis S. Kouikoglou. 2018. “Climate Security Assessment of Countries.” Climatic Change 148 (1): 25–43. doi:10.1007/s10584-018-2196-0.

- Pizarro, Jessica, Bre-Anne Sainsbury, Jane Hodgkinson, and Barton Loechel. 2017. “Australian Uranium Industry Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment.” Environmental Development 24 (1): 109–123. doi:10.1016/j.envdev.2017.06.002.

- Po, Sovinda, and Christopher B. Primiano. 2021. “Explaining China’s Lancang-Mekong Cooperation as an Institutional Balancing Strategy: Dragon Guarding the Water.” Australian Journal of International Affairs 75 (3): 323–340. doi:10.1080/10357718.2021.1893266.

- Rice, Martin, Lesley Hughes, Will Steffen, Simon Bradshaw, Hilary Bambrick, et al. 2022. A Supercharged Climate: Rain Bombs, Flash Flooding and Destruction. Potts Point: Climate Council of Australia.

- Spijkers, Jessica, Gerald Singh, Robert Blasiak, Tiffany H. Morrison, Philippe Le Billon, et al. 2019. “Global Patterns of Fisheries Conflict: Forty Years of Data.” Global Environmental Change 57 (1): 101921. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2019.05.005

- Steffen, Will, Karl Mallon, Tom Kompas, Annika Dean, and Martin Rice. 2019. Compound Costs: How Climate Change is Damaging Australia's Economy. Potts Point: Climate Council of Australia.

- Stevens, Heather R., Paul J. Beggs, Petra L. Graham, and Hsing-Chung Chang. 2019. “Hot and Bothered? Associations Between Temperature and Crime in Australia.” International Journal of Biometeorology 63 (6): 747–762. doi:10.1007/s00484-019-01689-y.

- Swann, Tom, and Rod Campbell. 2016. Great Barrier Bleached: Coral Bleaching, the Great Barrier Reef and Potential Impacts on Tourism. Canberra: Australia Institute.

- Taylor, Michael A.P., and Michelle L. Philp. 2015. “Investigating the Impact of Maintenance Regimes on the Design Life of Road Pavements in a Changing Climate and the Implications for Transport Policy.” Transport Policy 41 (1): 117–135. doi:10.1016/j.tranpol.2015.01.005.

- Telford, Andrew. 2018. “A Threat to Climate-Secure European Futures? Exploring Racial Logics and Climate-Induced Migration in US and EU Climate Security Discourses.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 96 (1): 268–277. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.08.021.

- Thomas, Michael Durant. 2011. “Climate Change and the ADF.” Australian Defence Force Journal 20 (185): 34–44. https://search.informit.org/doi/abs/10.3316/INFORMIT.451430811278277

- Thomas, Michael Durant. 2017. The Securitization of Climate Change: Australian and United States’ Military Responses (2003–2013). Cham: Springer.

- Tir, Jaroslav, and Douglas M. Stinnett. 2012. “Weathering Climate Change: Can Institutions Mitigate International Water Conflict?” Journal of Peace Research 49 (1): 211–225. doi:10.1177/0022343311427066.

- Towie, Narelle. 2022. “‘A Logistical Nightmare’: Flooding Takes Out Sole Rail Link Sparking West Australian Food Shortage.” https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2022/feb/04/a-logistical-nightmare-flooding-takes-out-sole-rail-link-sparking-west-australian-food-shortage (05/02/2022).

- Tranter, Kellie. 2019. “Is Defence Covering Bases for Climate Risk?” https://www.newcastleherald.com.au/story/6246272/is-defence-covering-bases-for-climate-risk/ (24/08/2022).

- UN Security Council. 2021. 8864th Meeting: Maintenance of International Peace and Security: Climate and Security. New York: United Nations.

- van Oldenborgh, Geert Jan, Folmer Krikken, Sophie Lewis, Nicholas J. Leach, Flavio Lehner, et al. 2021. “Attribution of the Australian Bushfire Risk to Anthropogenic Climate Change.” Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences 21 (3): 941–960. doi:10.5194/nhess-21-941-2021.

- Vitousek, Sean, Patrick L. Barnard, Charles H. Fletcher, Neil Frazer, Li Erikson, et al. 2017. “Doubling of Coastal Flooding Frequency Within Decades due to sea-Level Rise.” Scientific Reports 7 (1): 1399. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-01362-7.

- von Uexkull, Nina, and Halvard Buhaug. 2021. “Security Implications of Climate Change: A Decade of Scientific Progress.” Journal of Peace Research 58 (1): 3–17. doi:10.1177/0022343320984210.

- Vousdoukas, Michalis I., Roshanka Ranasinghe, Lorenzo Mentaschi, Theocharis A. Plomaritis, Panagiotis Athanasiou, et al. 2020. “Sandy Coastlines Under Threat of Erosion.” Nature Climate Change 10 (3): 260–263. doi:10.1038/s41558-020-0697-0.

- Wang, Xiaoming, Dong Chen, and Zhengen Ren. 2010. “Assessment of Climate Change Impact on Residential Building Heating and Cooling Energy Requirement in Australia.” Building and Environment 45 (7): 1663–1682. doi:10.1016/j.buildenv.2010.01.022.

- Watson, Cynthia. 2008. U.S. National Security: A Reference Handbook. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO.