ABSTRACT

This article maps the behaviours of two middle powers, Australia and Indonesia, as a response to the emergence and evolution of the Indo-Pacific concept. The background for this analysis is the emergence and development of the ‘Indo-Pacific’ concept as a response to crises of legitimacy enveloping the region and how countries in the region, including middle powers, respond to it. Using a minimalist definition which I have developed of a middle power as a country with a middle level of power capabilities and a penchant for cooperation, this article develops a framework based on two dimensions of outcome (ranging from status-quoist to reformist outlooks) and process (ranging from Lockean to Kantian strategies) to facilitate a more open-ended approach towards looking at middle-power behaviours beyond the common categorisation of traditional/emerging, and Western/non-Western. Using Australia’s 2017 Foreign Policy White Paper and 2023 National Defence: Defence Strategic Review, and Indonesia’s 2015 Defence White Paper and 2019 ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific, this article concludes that while Australia is exhibiting a status-quoist/Lockean approach, Indonesia is demonstrating a reformist/Kantian approach towards the Indo-Pacific. The outcome-process dimension framework developed in this article is useful as a tool to map other middle power behaviours in various contexts.

Introduction

The rise of the Indo-Pacific concept within the lexicon of international politics has triggered responses from policymakers within and beyond the alleged new region. These responses range from a full acceptance of the concept by countries such as the United States (US) (Zeng and Zhang Citation2021), Japan (Koga Citation2020), India (Roy-Chaudhury and de Estrada Citation2018), Australia (Taylor Citation2020), and Canada (Benjamin Citation2022), to an oppositional stance by China (Zhang Citation2019), with a middle position of qualified acceptance by the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) and its 11 member states (Tan Citation2020) as well as South Korea (Wilkins and Kim Citation2022, 431–434).

However, even among those countries that have fully embraced the concept, there are different responses towards US’ Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP) strategy. The FOIP strategy was initially formulated by Japan in 2016 and subsequently adopted and developed by the US as its own; however, in 2018, Japan moved away from treating it as a strategy and into a more abstract-sounding ‘vision’ to avoid any perception of aggressive intention (Koga Citation2020, 65). India, while having China’s rise as the main concern in its Indo-Pacific strategy, is not comfortable with the US’ FOIP strategy and prefers to reassure China that it is not the main target of the country’s Indo-Pacific strategy – a strategy of ‘evasive balancing’ (Rajagopalan Citation2020). Australia has embraced FOIP as a normative frame only (Wallis et al. Citation2020, 2) and has not expressed any interest in joining the US’ Freedom of Navigation Operation (FONOP) as part of its FOIP strategy (Taylor Citation2020, 106). Canada has managed to avoid being tangled in the US’ FOIP strategy, as it may place it at odds with Southeast Asian countries (Mustapha Citation2023, 10).

While Chinese policymakers’ stance on the Indo-Pacific concept has been categorised as ‘curious nonchalance’ (Zhang Citation2019), in reality, there are more diversity in responses from within China towards the concept, particularly among its scholars (Ma Citation2020). Southeast Asian countries via ASEAN have issued the ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific (AOIP), among other means, as a hedging tool against various uncertainties that may result from US–China competition in the Indo-Pacific (Kuik Citation2022) and as a proposal to move the evolution of the concept away from the dominance of any one country (Anwar Citation2020, 127). South Korea’s adoption of the Indo-Pacific concept has been called ‘circumspect’ (Wilkins and Kim Citation2022, 431–433) and ‘cautious’ (Abbondanza Citation2022, 412–414).

This article argues that while the emergence and development of the Indo-Pacific concept can be seen as a response to China’s Belt and Road Initiative and its overall assertive foreign policy (Jung, Lee, and Lee Citation2021, 53), the bigger question attached to the Indo-Pacific concept is how the crises of legitimacy of the regional and global order have been recognised in the region (Wirth and Jenne Citation2022), which then prompts the need to re-arrange the way policymakers formulate and engage with the region (Wilkins and Kim Citation2022). However, this article does not equate this order with a US-led one, as there are aspects of the global order that have neither been created nor maintained by the US, such as the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (Strating Citation2020, 8), which the US has not ratified. This article understands the hierarchical structure in the Indo-Pacific as a multiplex order (Acharya Citation2017), where there is more than one constituting principle in organising regional interactions involving various actors. Liberal principles are only one set at play in the region. Further, states are not the only actors in the Indo-Pacific.

Therefore, regional countries’ engagement in the concept must be considered as a response to both China’s rise and the decreasing level of legitimacy of the current order at play in the region. Given the various ways in which countries within and beyond the region engage with the concept, it is important to pay attention to the nuances involved in different countries’ responses, especially vis-à-vis the impact the crises of legitimacy have on what has traditionally been recognised as their foreign policy approach. Especially for middle powers in the region, whose foreign policy is usually associated with ‘middlepowermanship’ traits of mediation, coalition-building, and multilateralism (Stephen Citation2013, 38), their response to the crises of legitimacy as a result of the US’ decline and China’s rise have shown a divergence away from these very traits towards more realist traits of balancing and alliances, as shown by Efstathopoulos in the case of Australia (Citation2023, 221–223).

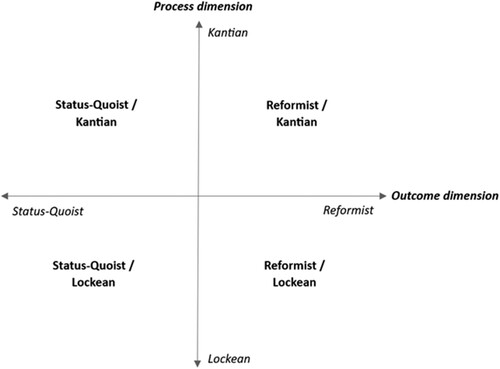

This article connects the behaviours of middle powers in the Indo-Pacific region with the Indo-Pacific concept. It analyses the association between the Indo-Pacific concept and the regional middle powers’ perceptions and responses to the concept in the form of their foreign and defence policies. Efstathopoulos’s work (Citation2023), which focused on the application of the Grand International Relations theory (with its mission of bridging Western/Non-Western IR theories), analyses middle powers’ behaviours using the examples of Australia and Brazil. Different from this work, this article at hand investigates this association vis-à-vis two middle powers in the Indo-Pacific region representing the so-called traditional and emerging categories, Australia and Indonesia, using two dimensions developed based on the works of Jordaan (Citation2003), Struye de Swielande (Citation2018), and Teo (Citation2022). These two dimensions, in line with Goh’s (Citation2007) framework, are the outcome and process. Whereas the former revolves around a middle-power’s outlook on what a status quo means for the Indo-Pacific and the importance (or otherwise) of maintaining it, and ranges from status-quoist to reformist, the latter revolves around the strategies with which a middle power engages the Indo-Pacific, and ranges from Lockean to Kantian approaches.

Before explaining these dimensions in detail, the article presents a picture of the Indo-Pacific as a region in which crises of legitimacy on regional and global order have been evolving. Next, it elaborates both dimensions of outcome and process as tools to describe middle-power behaviours, followed by a mapping of Australia and Indonesia’s positions in both dimensions. The last section concludes the article.

The context: crises of legitimacy in the Indo-Pacific

Most studies have treated regional countries’ engagement with the Indo-Pacific concept as a function of their response to the power dynamics and the rivalry between the US and China and their need to choose a side. Studies have thus, for example, described India’s Indo-Pacific strategy as ‘evasive balancing’ (Rajagopalan Citation2020), Australia’s as showing ‘dilemmas of mateship’ (Job Citation2020), Indonesia’s as a form of ‘balancing behavio[u]r of a “dove state”’ (Shekhar Citation2022) and a ‘hedging plus policy’ (Anwar Citation2023). Other studies have identified South Korea’s strategy as ‘manoeuvring in a geopolitical middle’ (Job Citation2020), Southeast Asian countries’ and ASEAN’s as ‘hedging’ (Tan Citation2020; Kuik Citation2022), and Canada as being ‘stuck … in the middle’ (Job Citation2020).

This article, however, looks at the emergence of the Indo-Pacific concept as a result of crises of legitimacy in the region and employs Reus-Smit’s (Citation2007) work on the issue of international crises of legitimacy. Reus-Smith understood legitimacy as ‘an entitlement to control, which generally means an entitlement to issue authoritative commands that require compliance from those subject to them’ (158) and noted that it is thus socially sanctioned and subject to contestation from its subjects. Reus-Smit defined the concept of crises as ‘critical turning points in which the imperative to adapt is heightened by the immanent possibility of death, collapse, demise, disempowerment, or decline into irrelevance’ (166). Adopting this frame to look at the crises of legitimacy in the Asia-Pacific arrangement that resulted in the emerging Indo-Pacific regional conception as a form of systemic adaptation, Wirth and Jenne (Citation2022) listed increasing strains on the US hub-and-spoke system and the poor performance of Asia-Pacific regionalism as causes for the crisis in the Asia-Pacific regional order.

There are a few important characteristics of the regional ordering of the Indo-Pacific. First, there is more than one order operating in it and the US is not the only source of this order. The US hub-and-spoke bilateral post-World War II order has been the dominant feature of the ordering mechanism in East Asia and beyond but ASEAN and its various institutions and norms have played a great role in the multilateral landscape of the region (Acharya Citation2021, 112). Among these institutions are the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF), ASEAN Plus Three (APT) and the East Asia Summit (EAS) with their organising principles of ASEAN’s 1976 Treaty of Amity and Cooperation (TAC) and the 2011 EAS Declaration of Principles (Bali Principles) emphasising, unlike the logic of US alliance under its hub-and-spoke structure and the liberal-democratic logic of the UN system, neutrality and respect for national sovereignty in conducting regional matters. In line with Acharya’s idea of multiplex, therefore, the order in the Indo-Pacific must be understood as a plurality of organising principles and norms (Acharya Citation2017).

Second, even if we only focus on the rules-based order created and maintained by the US, countries in the region have different definitions of what constitutes that order. For example, Strating (Citation2020) found different views of what constitutes a maritime rules-based order even among ‘like-minded’ US allies and partners of Australia, Japan, South Korea, and India (57).

Third, various countries have attempted and are still attempting to breach the regional order. China is at the forefront of these challenges, but the US is also guilty of undermining the regional order. Reflecting on Ikenberry’s three pillars of the liberal international order of free trade, intergovernmental organisations, and international law (Ikenberry Citation2009), China has been challenging this order through import bans and excessive import tariffs to punish countries that it deems hostile. For example, it imposed these measures on South Korea in 2017 in response to its Terminal High Altitude Area Defence program (Yang Citation2019). Nevertheless, particularly under the Trump Administration, the US has also undermined the liberal international order to some degree with its decisions to leave the Trans-Pacific Partnership and Paris Climate Agreement in 2017 and its disdain for various international institutions and cooperation (Jung, Lee, and Lee Citation2021, 56). Thus, focusing too much on China in this respect risks associating our definition of rules-based order only on the aspects of that order that China has been challenging, whereas in reality there are many aspects in ‘a world of orders’ and that China, while challenging some of them, has been quite supportive of the others (Johnston Citation2019).

The framework: outcome and process dimensions of middle-power behaviours

In the International Relations literature, there is no commonly agreed definition for the term ‘middle power’ (Struye de Swielande Citation2018, 19). There are various approaches to defining it. Teo (Citation2022) elaborated on the three key factors most commonly used to identify a middle power: position, identity and behaviour. Position is related to a middle power’s military and economic capacity as immediately below great powers; identity is related to a state’s self-identification and other states’ acknowledgement of its status as a middle power; and behaviour is related to a middle power’s supposedly liberal foreign policy characteristics (middlepowermanship) associated with multilateralism, niche diplomacy, and soft power tactics. Carr (Citation2014) added a fourth element to this, namely systemic impact, which is the capacity to protect its core interests and the ‘ability to alter a specific element of the international order through formalised structures, such as international treaties and institutions, and informal means, such as norms or balances of power’ (80). Struye de Swielande (Citation2018) agreed with Carr’s definition but used slightly different names to refer to each approach (20–21).

More and more analyses, however, have found middle powers behaving out of line with the liberal foreign policy trajectory. Jordaan (Citation2003) traced the origin of ‘emerging middle powers’ such as Argentina, Brazil, Nigeria, Malaysia, South Africa, and Turkey, which have all been successful in their economic development after the Cold War, but have usually been marked by relatively unstable democratic traditions. In terms of foreign policy, they show a more reformist stance towards global order and a high appetite to engage more at the regional level. He contradicted these traits with those of ‘traditional middle powers’, with a more established democratic tradition and appeasing stance towards the global order. Jordaan later reflected further on the categories he developed and concluded that it would be more beneficial to keep the traditional definition of middle power and let the concept of a middle power refer to ‘traditional middle power’ (Jordaan Citation2018).

More current observations on the behaviours of ‘traditional middle powers’ show a divergence from liberal foreign policy traditions. Abbondanza (Citation2021) traced this change in Australia’s foreign policy in terms of its ‘good international citizen’ image owing to its hard-line policies towards asylum seekers, among other things, while Efstathopoulos (Citation2023) demonstrated Australia’s contemporary proclivity for a more realist character of foreign policy in the form of balancing and alliance building, and Wallis (Citation2020) saw Australia’s foreign policy as being too reliant on its alliance with the US.

This article considers the need to still employ the term ‘middle power’ even with the increasingly non-liberal foreign policy trajectories of some of these powers. Instead, it sees the need to investigate this change in trajectory as well. This position of not throwing the baby out with the bathwater requires a minimalist definition of middle power. There are two aspects to this minimalism: First, instead of using all four factors to define a middle power, this article uses only the positional and behavioural aspects. Second, while discussing a middle power’s behaviour, this article only uses a middle power’s predilection for cooperation as a marker of a middle power, as this is a function of its position in the international system of not being strong enough to make any change on its own, but being strong enough to influence change. The nature of this cooperation can either be liberal or otherwise and does not necessitate middlepowermanship as a trait of middle-power behaviours. To use Ravenhill’s (Citation1998) 5 C’s indicators of a middle power (capacity, concentration, creativity, coalition-building, and credibility), this article uses only the capacity indicator (similar to the positional aspect of the minimalist definition) and the coalition-building one (similar to the behavioural aspect of the definition) to define a middle power.

To reiterate, using a minimalist definition of middle power by concentrating on their positional and behavioural aspects makes it possible to envisage middle-power behaviours not only from a sole trajectory of middlepowermanship, associated with liberal foreign policy. This is particularly important in the context of increasing US–China competition and its impact on decreasing the strategic space to manoeuvre for middle powers (Boon and Teo Citation2022, 60). Moreover, instead of explaining the tendency of some middle powers as a move away from a certain trajectory (middlepowermanship), the use of this minimalist definition allows us to develop a categorisation of where their current trajectories actually lie (see the categorisation below). Another benefit of employing this minimalist definition is to provide a more disciplined understanding of what middle power means before developing any categorisation of its behaviours. For example, without putting forward an exact (minimalist) definition of middle power, and as a consequence still accepting middlepowermanship as a condition of being a middle power, it will be difficult to justify the categorisation of middle-power behaviours into Hobbesian, Lockean and Kantian by Struye de Swielande (Citation2018).

After clarifying what it means by ‘middle power’, this article can now build a framework to map the different behaviours of middle powers, based on the outcome and process dimensions. The naming and understanding of these two dimensions is based on Goh’s (Citation2007) framework. Goh considered outcomes ‘in terms of systemic attributes, particularly the distribution of power’ and defined order as ‘processes that regulate inter-state relations and expectations towards common goals’ (119). Drawing from this, this article sees the outcome as an aspirational power order that middle powers aim for through the implementation of their strategies, or processes, in the region. Unlike Goh, this article does not treat outcomes in terms of polarity but as the objective of the state’s strategies in terms of whether the status quo must be maintained or reformed; thus, outcomes range from ‘status-quoist’ to ‘reformist’. Processes range from ‘Lockean’ to ‘Kantian’.

The status-quoist and reformist categories are a simplified version of Struye de Swielande’s (Citation2018) list of categories in the literature to classify middle powers into followers (of the status quo), critical and toxic followers, and potential reformist or swing states (22). While middle powers definitely benefit from any current global and regional order owing to their ‘privileged positions in the global political economy … and regional political economies’ (Jordaan Citation2003, 169) (and thus the justification in this article for the status-quoist extreme in this spectrum of the first dimension), they have the incentive to weaken the traditional stratification of power and strengthen the functional differentiation in the system (Teo Citation2022, 17) without abolishing the current system. Thus, it amounts to the other extreme of reform, and not revision. A reformist tendency is possible for a middle power owing to its middle-level power capability coupled with its interest in increasing its influence in the system; ameliorating the system to be more inclusive of the sort of (functionally different) capability that it has helps a middle power with this aspiration.

As for the second dimension of process, Struye de Swielande’s (Citation2018) typology of middle powers into Hobbesian, Lockean, and Kantian categories serves as its base. Adopting Wendt’s (Citation1999, 246–312) classification of cultures of anarchy into Hobbesian, Lockean, and Kantian, Struye de Swielande associated Hobbesian middle powers with power politics, security, alliance, and prioritisation of high politics, Lockean middle powers with a mixed use of high and low politics, and Kantian middle powers with emphasis on middlepowermanship and low politics without totally excluding high politics (27).

This article compares the above definition of Hobbesian middle powers with Wendt’s original understanding of the Hobbesian culture of anarchy with an emphasis on states’ engagement with each other as enemies (Citation1999, 260) and argues that this typology does not fit the minimalist definition of middle power above because, first, the logics of ‘war of all against all’ (265) and ‘no-holds-barred power politics’ (262) work against the core interests of survival for middle powers with their limited, middle-level power capability. Second, in contrast to the above understanding of the Hobbesian culture, alliances are a property of the Lockean culture in the Wendtian framework (299) and the Hobbesian culture of ‘war of all against all’ does not allow for any form of cooperation. Thus, this article dispenses with the Hobbesian category of middle power for its framework.

The Lockean culture in the Wendtian framework is based on the logic of rivalry (Wendt Citation1999, 279). There are four implications for this logic for foreign policy: (1) states respect each other’s sovereignty; (2) owing to the first implication above, states’ anxiety towards others’ intent is less intense; (3) military strength is still important to address threats and balance rivals but as threats are less existential, the alliance is more likely to occur and prevail; and (4) should disputes proceed to war, the following violence will be limited (282–283). In this article, Lockean middle-power behaviour comprises two elements: respect for sovereignty and international law, and a preference for balance and alliances.

In the Wendtian framework, the Kantian culture of anarchy involves the logic of friendship and the prevalence of a collective security system (Wendt Citation1999, 298, 300). This article does not define Kantian middle-power behaviours this way and instead focuses on middlepowermanship as this type’s defining trait and specifically uses Behringer’s (Citation2013) three elements of middlepowermanship, namely multilateral diplomacy, preference to work on niche issues, and the use of soft power. In this article, Kantian middle powers use multilateral diplomacy as a means to settle disputes. They realise their own power limitation and thus choose niche issues on which they more likely have an influence. As another function of their limited material power, they choose to focus on their soft power in affecting change.

While employing a Wendtian perspective in elaborating the process dimension of the theoretical framework, this article does not adopt a constructivist perspective, with which Wendtian framework is often associated. Instead of using the categories of Lockean and Kantian as two different cultures of anarchy, the outcome-process framework in this article sees them as two logics of anarchy. The difference between the two lies in the levels of analysis: culture refers to a commonly accepted perception of the nature of international sytem by a group/society of states while logic refers to individual state’s employment of a certain way of looking at the system. There is no doubt that having a certain logic can be a result of a certain culture but this article is interested only in elaborating on how that logic is reflected in the formal statements pertaining to an individual state’s foreign and defence policies.

offers a visual representation of the two-dimensional framework elaborated above and the next section uses this framework to investigate the behaviours of Australia and Indonesia as middle powers through analysing their official documents, and shows their status-quoist/Lockean and reformist/Kantian approaches, respectively, in the context of the emergence of the Indo-Pacific construct.

The actors: Australia and Indonesia

To trace both middle powers’ approaches to the Indo-Pacific concept vis-à-vis the outcome and process dimensions elaborated above, this article uses their official documents which detail their defence and foreign policy directions. Using these documents, this article establishes the narratives related to what their governments consider the status quo in the region, their stance towards this status quo, and the strategies they use to attempt to either maintain or reform it. For Australia, the 2017 Foreign Policy White Paper and 2023 National Defence: Defence Strategic Review are used. For Indonesia, the 2015 Defence White Paper and 2019 AOIP are used to help map its position within the framework.

NVivo is used to identify and analyse the narratives in these documents. For the outcome dimension, this article uses the keywords ‘liberal international order’, ‘rules-based order’, ‘maintain’ and ‘stability’ to start the process of tracing the presence of the status-quoist tendency in these four documents. To check for the presence of the reformist tendency, the phrases ‘transform’, ‘neutral’ and ‘peace’ are used. For the Lockean category, the phrases ‘alliance’, ‘balance’, ‘competition’ and ‘rivalry’ are used while for the Kantian category, this article uses the phrases ‘cooperation’, ‘diplomacy’, ‘niche’, ‘soft power’, ‘multilateral’, ‘interdependence’ and ‘values’. These keywords are used only to approximate the four tendencies within the four documents, and it does not mean that the presence of these words exclusively marks a certain tendency. Instead, this article treats these phrases only as potential markers for those tendencies and reviews each relevant sentence containing those phrases in the context of the paragraph and section where it is located.

The two documents for Australia were produced by the current Labor (the 2023 National Defence: Defence Strategic Review) and previous Coalition (the 2017 Foreign Policy White Paper) governments. Despite one being a foreign policy document and the other a defence one, there is a continuity of narratives regarding their definition and stance on the status quo with the defence document showing a more Lockean turn in the country’s defence policy. Both documents for Indonesia were produced in the first and second terms of Joko Widodo’s presidency and, despite one being a defence document and the other a regional outlook document submitted to and later agreed upon by ASEAN, a reformist outlook and preference for the Kantian approach in the context of great power competition in the region are present in both.

Although these documents are not legislative documents, they are both a reflection and a guide for both countries’ foreign and defence policies. As a reflection, these documents are a statement of how each country currently views its strategic environment. As a guide, they offer basic principles on how to engage with this environment. For these two reasons, these four documents are essential to inform us of what sort of foreign and defence policies both countries have taken and will take and why they choose these policies.

Australia’s status-quoist/Lockean approach to the Indo-Pacific

The Australian government released its first Foreign Policy White Paper in 14 years on 23 November 2017 (the ‘White Paper’ from hereon) (Commonwealth of Australia Citation2017). This White Paper cites ‘rapid change’ as the main reason for its issuance. Australia’s latest (at the time of study) Defence White Paper was released in 2016. Following this, the Australian government released the 2020 Defence Strategic Update and the 2023 National Defence: Defence Strategic Review (the ‘Review’ from hereon) (Commonwealth of Australia Citation2023). In response to the recommendations suggested in this review, the Australian government expressed either agreement or agreement in principle.

The White Paper defines the Indo-Pacific as ‘the region ranging from the eastern Indian Ocean to the Pacific Ocean connected by Southeast Asia, including India, North Asia and the United States’ (1). In terms of security threats to Australia, the Review recognises:

(T)he strategic competition between major powers; the use of coercive tactics; the acceleration and expansion of military capabilities without necessary transparency; the rapid translation of emerging and disruptive technologies into military capability; nuclear weapons proliferation; and the increased risk of miscalculation or misjudgement. (28)

According to the White Paper, underlining several threats to Australia’s security is the power shift in the Indo-Pacific with the rise of China. In the document, China’s power and influence have been pictured as matching and, in some respects, exceeding that of the US (25) and as a result of this will attempt to influence the region to serve its interests (26). This is significant especially because Australia has benefited from the current international order maintained by the US (21). The White Paper acknowledges that the US has had a stabilising presence in the Indo-Pacific, and that for the foreseeable future, it will retain its dominant military and soft power (26).

Chapter 2 of the White Paper, titled ‘Contested World’, shows that the assumption of the association between Australia’s security and prosperity with the current international order created and maintained by the US is at the base of Australia’s foreign policy and that this foreign policy should seek to maintain the presence of the US in the Indo-Pacific against any potential revisionist force to both the regional and global order. The status quo is beneficial for Australia and must be maintained – the status quo itself being defined as a liberal, rules-based order, which is assumed to have the US as its main supporter. Using the term ‘rules-based order’, the White Paper associates itself with liberal values (7), peaceful resolution of disputes (105), and the importance of the US’ engagement to maintain the effectiveness of the that order (7). The White Paper sees the rules-based order in relation to the implementation of international law and as opposed to the application of coercive power (7, 83).

The nature of change in the Indo-Pacific in the Review is linked to the fact that Australia’s main ally, the US, is no longer the unipolar leader of the region (23) and that it is being challenged by China. This situation threatens Australia’s national interest owing to what the China–US competition may bring, including the risk of an open conflict. However, Australia is not taking a neutral stance vis-à-vis this competition and the risk of this competition spilling out into an open conflict. The Review focuses on China’s strategies and their impact in threatening the rules-based order, especially its sovereignty claim in the South China Sea (23). Defending the rules-based order, therefore, is in Australia’s best interest (5) and Australia’s defence must aim at doing so (6). In both the White Paper and Review, Australia sees the maintenance of the status quo as its main objective and considers it synonymous with the liberal rules-based order maintained by the US.

The White Paper identifies traditional and non-traditional security threats facing Australia. The latter include threats from, among other things, climate change, and food, energy, and water security (84–97), whereas the former is mainly related to the potential of open conflict between the US and China that will involve competition for power and principles and values of the regional order (26), on top of issues such as North Korea’s nuclear threat (42–43) and the proliferation of other weapons of mass of destruction (83–84). To counter these threats, the White Paper recommends military (by modernising the maritime capabilities of the Australian Defence Force and increasing its capability to apply force with a higher degree of speed and effectiveness [27]) and non-military means (including increasing the country’s capacity in protecting and strengthening international rules [82] and its soft power [109–115]). As part of its defence, reliance on the US deterrence is still a big part of Australia’s strategy, especially in addressing potential nuclear attacks [4, 39, 84].

The Review emphasises the Australia–US alliance, especially in the context of the changing strategic environment in the Indo-Pacific and nuclear threats in the region (78). However, it also realises the importance of Australia increasing its deterrence capacity. The technological source of this capacity will come mainly from Australia’s involvement within the AUKUS alliance, through its first and second pillars on the provision of conventionally-armed, nuclear-powered submarines (8) and more advanced defence capabilities, such as underwater warfare and hypersonics (72), respectively. The Review asserts that even though any invasion of the Australian content is unlikely, incursion in its exclusive economic zone and disruption of its sea lines of communication are still a possibility, and therefore, Australia should have a credible deterrence capability to manage these risks (37). Although China is never mentioned as a target of this deterrence (it is only mentioned in the first and second chapters of the Review while detailing the current strategic environment in the region), the painting of China as a destabilising factor in the region is obvious in Chapters 1 and 2 of the Review either in its own capacity to pose a threat to regional stability or in its role in great power competition with the US (2).

To sum up, through analysing the White Paper and the Review, Australia as a middle power is showing a status-quoist/Lockean approach in its response towards the new construct of Indo-Pacific. While the White Paper provides a more general guide on how Australia should conduct its foreign policy in the context of changes in the region, the Review provides both a general guide as well as specific steps Australia needs to take to improve its national defence. Regardless of the insufficiency of defence spending in the 2023/2024 budget to fully realise the Review’s recommendations (Hellyer Citation2023), however, the Albanese Government’s defence spending in this budget is still the largest in the country’s history and the trend will continue in next decade or so (IISS Citation2023) to be geared towards following these recommendations.

In concrete terms, this status-quoist/Lockean approach is very obvious when looking at Australia’s ambitious defence capacity building projects, mainly through AUKUS trilateral security partnership, to address the increasing tensions in the Indo-Pacific. Just to show the extent of these projects, the first pillar of AUKUS will deliver eight submarines to be delivered within the next 30 years with a cost up to AUD368 billion (Green and Doran Citation2023). Furthermore, this status-quoist/Lockean approach can also be seen from Australia’s current penchant for minilateralism and alliance formation, mainly through the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue and AUKUS, instead for multilateralism (Abbondanza Citation2021, 191).

Indonesia’s reformist/Kantian approach to the Indo-Pacific

To trace Indonesia’s approach to the Indo-Pacific, this article analyses the narratives in its 2015 Defence White Paper (‘Buku Putih Pertahanan Indonesia’ – the ‘Indonesian Paper’ from hereon) (Ministry of Defence of the Republic of Indonesia Citation2015) and AOIP (ASEAN Citation2019). The first document is the first defence white paper in seven years, and it was released during the first Joko Widodo presidential term; there is no information on when the current defence minister will commission the formulation of the next white paper (Saptohutomo Citation2023). There are the Indonesian and English versions of this document and this article uses the latter.

The second document, although an ASEAN one, was formulated by Indonesian diplomats and can be traced back to the speech of the country’s then foreign minister Marty Natalegawa (the foreign minister under previous president Soesilo Bambang Yudhoyono) at the Center for Strategic and International Studies on 20 May 2013 (Weatherbee Citation2019, 2). In his second term, Joko Widodo commissioned his foreign minister to draft an ASEAN document to manage the development of the Indo-Pacific concept. This document was called ‘ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific’ (AOIP) and was formally endorsed by ASEAN leaders in a meeting in June 2019 in Bangkok (Anwar Citation2020, 127). The AOIP reflects Indonesia’s view of the Indo-Pacific and how it should be managed in the future. It comprises 6 sections and 23 articles. The sections are titled: Background and Rationale, ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific, Objectives, Principles, Areas of Cooperation, and Mechanism.

The Indonesian Paper’s basic premise in understanding the dynamics of global security is that economic growth enhances regional military power (1). This premise is particularly applicable to the contribution of China’s economic development to its military modernisation and how this has been affecting and will affect the military balance and create a security dilemma in the region (7). The Indonesian Paper does not use the term ‘Indo-Pacific’ despite having proposed, under its previous president Soesilo Bambang Yudhoyono and through his foreign minister’s speech in May 2013, ‘An Indonesian Perspective on the Indo-Pacific’ (Natalegawa Citation2013; Suryadinata Citation2018, 4). This is mainly because the first term of Joko Widodo’s presidency focused more on an inward-looking maritime policy (Dannhauer Citation2022, 10). The Indonesian Paper spots the potential security risk to regional stability posed by China’s economic development and its consequent military modernisation, especially as the US is trying to rebalance this development through economic and diplomatic engagement, and military rebalancing in the region (7).

The Indonesian Paper recognises the presence of traditional and non-traditional security challenges in the Asia Pacific (this is the term the paper uses to describe the strategic region where Indonesia is located). Among the non-traditional security challenges are terrorism, espionage, transnational crime, climate change, natural disaster, food security, and global epidemics, among others. Traditional security challenges listed in the Indonesian Paper are inter-state border issues, intra and inter-state conflicts, and weapons of mass destruction. The threats brought in by the South China Sea disputes are explained in detail in terms of the use of military instruments as part of the claimant states’ claims, the involvement of other countries from outside the region in the disputes, and the fact that there is no credible institution to help resolve the issue (8).

The Indonesian Paper accepts that China’s rise forms the backdrop for the increasing strategic insecurity for Indonesia, but the said rise plays its part through the provision of military modernisation and the response by the US to this modernisation in the form of balancing (7). China is posing a threat to regional stability in its own right, but not least important as another threat is the China–US competition owing to China’s rise; and to respond to this, Indonesia has encouraged the creation of a ‘dynamic equilibrium’: ‘a condition characterised by [the] absence of a dominant state power in the region’ (2). This dynamic equilibrium is Indonesia’s vision of the region to replace the great power competition that is currently prevailing.

The AOIP, a product of Joko Widodo’s second presidential term where the president’s interest in maritime cooperation and connectivity coincided with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ vision of ASEAN’s approach to the Indo-Pacific (Dannhauer Citation2022, 18), is premised on the same fear that the rise of material power (in both military and economic terms) contributes to ‘the deepening of mistrust, miscalculation, and patterns of behavio[u]r based on a zero-sum game’ (Article 1). An ‘inclusive regional architecture’ is perceived as the antidote to this development of mistrust, miscalculation, and a zero-sum game tendency (Article 3). The AOIP does not specify what it means by ‘inclusive regional architecture’ but in the same article, it argues that ASEAN’s ‘collective leadership’ will be an important element in ‘forging and shaping the vision for closer cooperation in the Indo-Pacific’. From both documents, it can be approximated that ‘an inclusive regional architecture’ and ‘a dynamic equilibrium’ involve the absence of a great power’s dominance in the region and an emphasis on the inclusion of the voice of all regional countries in the management of the region, regardless of their size. This is Indonesia and ASEAN’s vision of the Indo-Pacific. The AOIP states that ASEAN has been actively engaged in the development of this inclusive regional architecture and needs to maintain its central role in the evolving regional architecture in the newly conceptualised Indo-Pacific region.

In elaborating the principles that should govern the Indo-Pacific, the AOIP mentions the need to observe the (Lockean) norms of respect for sovereignty and non-intervention. The document emphasises the need not to create new mechanisms or replace the existing ones, but instead to strengthen the existing ASEAN-led mechanisms to achieve the vision of an inclusive regional architecture (Article 4), the most important of which is TAC, with its emphasis on the principles of respect for state sovereignty, non-interference, and peaceful means of dispute resolution (TAC, Article 2).

The AOIP, however, pays significant attention to other principles that sound more Kantian: inclusivity, equality, and mutual respect and benefit (Article 10). Still on Kantian themes, regarding the sort of Indo-Pacific that ASEAN wants to create, the document envisions a region of ‘dialogue and cooperation instead of rivalry’ and ‘development and prosperity for all’ (Article 6). Dialogue and cooperation are markers of AOIP’s preference for multilateral diplomacy, whereas the rejection of rivalry is a negation of the Lockean logic of anarchy. In terms of niche diplomacy, the AOIP lists various detailed areas of cooperation that can be initiated in the Indo-Pacific, divided into the themes of maritime cooperation, connectivity, and the UN Sustainable Development Goals 2030 (Section V). With respect to soft power, the AOIP relies on the importance and acceptance of ASEAN centrality in the maintenance of regional order so far as capital to further influence the direction of the Indo-Pacific (Article 5).

Indonesia’s position in the outcome-process framework shows a reformist outlook on the Indo-Pacific through its vision of a dynamic equilibrium condition and an inclusive regional architecture through ASEAN. In terms of strategies to realise this vision, despite adherence to the non-intervention tradition of ASEAN, it relies mainly on multilateral processes and soft power, and focuses on niche issues for cooperation.

To summarise, in the Indonesian Paper and AOIP, the country has been showcasing a reformist/Kantian approach in response to the rise of US–China competition in the region. Although both documents only contain general guidelines on how the country should conduct its defence and foreign policies in the near future without specifying policy recommendations to be taken by both Indonesia and ASEAN, the reformist/Kantian principles embedded in these documents have also been reflected in the country’s various statements regarding the Indo-Pacific region (for an example of this sort of statement by the Foreign Minister, see MFA (Citation2023)).

In terms of concrete policies, Indonesia’s reformist/Kantian approach in the twenty-first century could be traced back to Megawati Sukarnoputri’s presidency with Indonesia’s proposal for the establishment of ASEAN Security Community in 2003, which later became ASEAN Political and Security Committee, as a tool to solidify ASEAN centrality and to move away from the logic of great-power competition in managing regional affairs (Anwar Citation2023, 368). The same motivation, plus the desire to facilitate a mechanism to enmesh great powers to the norms of amity and cooperation, as embedded in TAC, were behind Indonesia’s recommendation to promote a more inclusive regional architecture by widening the membership of East Asia Summit (369). Indonesia’s increasing contribution to peacekeeping operation, including the construction and management of National Peacekeeping Training Center in 2021 (Thies and Sari Citation2018, 405–406), is also a symptom of the country’s reformist/Kantian approach.

Conclusion

While Australia is moving towards a status-quoist/Lockean approach in its foreign policy, Indonesia is moving towards a reformist/Kantian one. Australia’s approach is marked by its preference for the maintenance of the status quo associated with the US-led liberal rules-based international order and its Lockean strategy has been developed along the lines of increasing its deterrence capacity in the midst of China’s rise and what this means for global and regional order. Reflecting on works focused on the cycle of Australia’s foreign policy movement between its middle-power episode (defined through a mainstream, liberal, understanding of the term) and its alliance-with-great-power episode, such as Widmaier (Citation2019) and Taylor (Citation2020), Australia is now in its alliance episode with its emphasis on the perceived need to stay close to its great and powerful ally. To add to this discussion, this article argues that what both Widmaier (Citation2019) and Taylor (Citation2020) associated with Australia’s foreign policy tradition of emphasising its alliance with great power reflects the status-quoist/Lockean approach of the outcome-process framework. This article, however, does not see Australia’s alliance tradition as opposite to its middle-power approach, as has been suggested by Beeson and Higgott (Citation2013). A middle power, minimally defined, has a wider range of approaches to take as a function of its place in the international system.

Indonesia’s reformist attitude is exhibited through its preference for a regional order marked by the absence of a single power’s dominance (dynamic equilibrium) and inclusion of regional states’ voices in the management of the regional order, regardless of its power capabilities (inclusive regional architecture). Indonesia’s Kantian trait is seen in its prioritisation of multilateral diplomacy and soft power as a de facto leader in ASEAN to pursue traditional and niche security issues that can enhance cooperation in the Indo-Pacific. To use Goh’s term of ‘omni-emneshment’ (Citation2007, 120–123), Indonesia’s reformist/Kantian approach is an effort to engage other states to abide by regional rules of engagement and to integrate it into the regional system. The idea of dynamic of equilibrium within AOIP is aimed at enveloping the US and China in a network of mutually agreed regional principles of cooperation.

In identifying Australia’s status-quoist approach and Indonesia’s reformist approach, this article sees the association between traditional and emerging middle powers (Jordaan Citation2003) and their appeasing and reformist stances towards the global order, respectively, as still valid. In terms of similarities, however, Jordaan's categorisation still sees middle powers (regardless of their categories) showing characteristics of middlepowermanship, namely a preference for multilateralism and niche diplomacy (169). There is thus still a heavy association between what being a middle power means and middlepowermanship in this categorisation. The process dimension in this article tries to detach this automatic definition of middle power through the introduction of the Lockean and Kantian categories.

In terms of the outcome dimension of the framework, and to reflect on the discussion of international crises of legitimacy (Reus-Smit Citation2007) in the Indo-Pacific (Wirth and Jenne Citation2022), this article has shown different interpretations of what sort of order is in operation in the region through its elaboration of the outcome dimension: a US-led liberal order (for Australia) or ASEAN-centred order (for Indonesia). While for Australia the rise of China is seen as a threat towards the US-led liberal order, the impact of this rise to the potential incursion of great-power competition into the region is the main worry for Indonesia. Within this context of changing global and regional environment due to increasing great-power competition, and the ensuing crises of legitimacy towards the current order, the outcome and process framework developed in this paper can hopefully help generate a more nuanced understanding of middle-power perceptions of the regional and international order as well their behaviours as a function of these perceptions.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the journal editors and the anonymous reviewers for their feedback for this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Christian Harijanto

Christian Harijanto is a Sessional Lecturer at the School of Media, Creative Arts and Social Inquiry at Curtin University. His research interests include the Indo-Pacific concept, middle-power theory, Australian and Indonesian foreign and defence policies, and Islam in Indonesian Politics.

References

- Abbondanza, Gabriele. 2021. “Australia the ‘Good International Citizen’? The Limits of a Traditional Middle Power.” Australian Journal of International Affairs 75 (2): 178–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/10357718.2020.1831436.

- Abbondanza, Gabriele. 2022. “Whither the Indo-Pacific? Middle Power Strategies from Australia, South Korea and Indonesia.” International Affairs 98 (2): 403–421. https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiab231.

- Acharya, Amitav. 2017. “After Liberal Hegemony: The Advent of a Multiplex World Order.” Ethics and International Affairs 31 (3): 271–285. https://doi.org/10.1017/S089267941700020X.

- Acharya, Amitav. 2021. ASEAN and Regional Order: Revisiting Security Community in Southeast Asia. London: Routledge.

- Anwar, Dewi Fortuna. 2020. “Indonesia and the ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific.” International Affairs 96 (1): 111–129. https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiz223.

- Anwar, Dewi Fortuna. 2023. “Indonesia’s Hedging Plus Policy in the Face of China’s Rise and the US-China Rivalry in the Indo-Pacific Region.” Pacific Review 36 (2): 351–377. https://doi.org/10.1080/09512748.2022.2160794.

- ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations). 2019. ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific. https://asean.org/asean2020/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/ASEAN-Outlook-on-the-Indo-Pacific_FINAL_22062019.pdf

- Beeson, Mark, and Richard Higgott. 2013. “The Changing Architecture of Politics in the Asia-Pacific: Australia’s Middle Power Moment?” International Relations of the Asia-Pacific 14: 215–237. https://doi.org/10.1093/irap/lct016.

- Behringer, Ronald M. 2013. “The Dynamics of Middlepowermanship.” Seton Hall Journal of Diplomacy and International Relations 14 (2): 9–22. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/dynamics-middlepowermanship/docview/1519491995/se-2?accountid=10382.

- Benjamin, Jacob. 2022. “Canada’s Cross-Pacific Relations: From Asia-Pacific to Indo-Pacific.” International Journal 77 (1): 89–111. https://doi.org/10.1177/00207020221116777.

- Boon, Hoo Tiang, and Sarah Teo. 2022. “Caught in the Middle? Middle Powers amid U.S.-China Competition.” Asia Policy 17 (4): 59–76. https://doi.org/10.1353/asp.2022.0058.

- Carr, Andrew. 2014. “Is Australia a Middle Power? A Systemic Impact Approach.” Australian Journal of International Affairs 68 (1): 70–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/10357718.2013.840264.

- Commonwealth of Australia. 2017. 2017 Foreign Policy White Paper. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia. https://www.dfat.gov.au/sites/default/files/2017-foreign-policy-white-paper.pdf.

- Commonwealth of Australia. 2023. National Defence: Defence Strategic Review. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia. https://www.defence.gov.au/about/reviews-inquiries/defence-strategic-review.

- Dannhauer, Pia. 2022. “Elite Role Conceptions and Indonesia’s Agency in the ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific: Reclaiming Leadership.” Pacific Review, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/09512748.2022.2125999.

- Efstathopoulos, Charalampos. 2023. “Global IR and the Middle Power Concept: Exploring Different Paths to Agency.” Australian Journal of International Affairs 77 (2): 213–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/10357718.2023.2191925.

- Goh, Evelyn. 2007. “Great Powers and Hierarchical Order in Southeast Asia: Analyzing Regional Security Strategies.” International Security 32 (3): 113–157. https://doi.org/10.1162/isec.2008.32.3.113.

- Green, Andrew, and Matthew Doran. 2023. “Australian Nuclear Submarine Program to Cost up to $368b as AUKUS Details Unveiled in the US.” Australian Broadcasting Corporation, March 14. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2023-03-14/aukus-nuclear-submarine-deal-announced/102087614.

- Hellyer, Marcus. 2023. “Defence Budget 2023-24IF – Nervous Times Ahead.” Australian Defence Magazine, June 12. https://www.australiandefence.com.au/defence/budget-policy/defence-budget-2023-24-nervous-times-ahead#:~:text=The%20annual%20defence%20budget%20has,years%20of%20the%20forward%20estimates.

- IISS (International Institute for Strategic Studies). 2023. “Australia’s 2023 Defence Strategic Review.” Accessed September 16, 2023. https://www.iiss.org/en/publications/strategic-comments/2023/australias-2023-defence-strategic-review/#:~:text=Australia's%202023%20Defence%20Strategic%20Review%20provides%20a%20blueprint%20for%20building,the%20threat%20posed%20by%20China.

- Ikenberry, G. John. 2009. “Liberal Internationalism 3.0: America and the Dilemmas of Liberal World Order.” Perspectives on Politics 7 (1): 71–87. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592709090112.

- Job, Brian L. 2020. “Between a Rock and a Hard Place: The Dilemmas of Middle Powers.” Issues and Studies. Institute of International Relations 56 (2): 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1142/S10132.51120400081.

- Johnston, Alastair Iain. 2019. “China in a World of Orders: Rethinking Compliance and Challenge in Beijing’s International Relations.” International Security 44 (2): 9–60. https://doi.org/10.1162/isec_a_00360.

- Jordaan, Eduard. 2003. “The Concept of a Middle Power in International Relations: Distinguishing between Emerging and Traditional Middle Powers.” Politikon 30 (1): 165–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/0258934032000147282.

- Jordaan, Eduard. 2018. “Faith No More: Reflections on the Distinctions between Traditional and Emerging Middle Powers.” In Rethinking Middle Powers in the Asian Century: New Theories, New Cases, edited by Tanguy Struye de Swielande, Dorothée Vandamme, David Walton, and Thomas Wilkins, 111–121. Milton: Taylor & Francis Group.

- Jung, Sung Chul, Jaehyon Lee, and Ji-Yong Lee. 2021. “The Indo-Pacific Strategy and US Alliance Network Expandability: Asian Middle Powers’ Positions on Sino-US Geostrategic Competition in Indo-Pacific Region.” Journal of Contemporary China 30 (127): 53–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2020.1766909.

- Koga, Kei. 2020. “Japan’s ‘Indo-Pacific’ Question: Countering China or Shaping a New Regional Order?.” International Affairs 96 (1): 49–73. https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiz241.

- Kuik, Cheng-Chwee. 2022. “Hedging via Institutions: ASEAN-Led Multilateralism in the Age of the Indo-Pacific.” Asian Journal of Peacebuilding 10 (2): 355–386. https://doi.org/10.18588/202211.00a319.

- Ma, Bo. 2020. “China’s Fragmented Approach toward the Indo-Pacific Strategy: One Concept, Many Lenses.” China Review 20 (3): 177–204. https://muse.jhu.edu/related_content?type=article&id=764075.

- MFA (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Indonesia). 2023. “Indonesian Foreign Minister: Indo-Pacific is not a Battle Ground.” July 14. https://kemlu.go.id/portal/en/read/4971/berita/indonesian-foreign-minister-indo-pacific-is-not-a-battle-ground.

- Ministry of Defence of the Republic of Indonesia. 2015. Defence White Paper. 3rd ed. Jakarta: Ministry of Defence of The Republic of Indonesia.

- Mustapha, Jennifer. 2023. “Rethinking Canada’s Security Interests in Southeast Asia: From ‘Asia-Pacific’ to ‘Indo-Pacific’.” Canadian Foreign Policy Journal x: 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/11926422.2023.2203936.

- Natalegawa, Marty. 2013. “An Indonesian Perspective on the Indo-Pacific.” The Jakarta Post, May 20. https://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2013/05/20/an-indonesian-perspective-indo-pacific.html.

- Rajagopalan, Rajesh. 2020. “Evasive Balancing: India’s Unviable Indo-Pacific Strategy.” International Affairs 96 (1): 75–93. https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiz224.

- Ravenhill, John. 1998. “Cycles of Middle Power Activism: Constraint and Choice in Australian and Canadian Foreign Policies.” Australian Journal of International Affairs 52 (3): 309–327. https://doi.org/10.1080/10357719808445259.

- Reus-Smit, Christian. 2007. “International Crises of Legitimacy.” International Politics 44 (2-3): 157–174. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.ip.8800182.

- Roy-Chaudhury, Rahul, and Kate Sullivan de Estrada. 2018. “India, the Indo-Pacific and the Quad.” Survival 60 (3): 181–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/00396338.2018.1470773.

- Saptohutomo, Aryo Putranto. 2023. “Menhan Prabowo Diminta Selesaikan Buku Putih Pertahanan Ketimbang Orkestrasi Intelijen.” Kompas, April 3. https://nasional.kompas.com/read/2023/04/03/23032591/menhan-prabowo-diminta-selesaikan-buku-putih-pertahanan-ketimbang-orkestrasi.

- Shekhar, Vibhanshu. 2022. “Indonesia”s Great-Power Management in the Indo-Pacific: The Balancing Behavior of a ‘Dove State’.” Asia Policy 29 (4): 123–149. https://doi.org/10.1353/asp.2022.0062.

- Stephen, Matthew. 2013. “The Concept and Role of Middle Powers during Global Rebalancing.” Seton Hall Journal of Diplomacy and International Relations 14 (2): 36–52. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/concept-role-middle-powers-during-global/docview/1622290539/se-2?accountid=10382.

- Strating, Rebecca. 2020. Policy Study 80: Defending the Maritime Rules- Based Order: Regional Responses to the South China Sea Disputes. Washington: East-west Center. https://www.eastwestcenter.org/publications/defending-the-maritime-rules-based-order-regional-responses-the-south-china-sea.

- Struye de Swielande, Tanguy. 2018. “Middle Powers: A Comprehensive Definition and Typology.” In Rethinking Middle Powers in the Asian Century: New Theories, New Cases, edited by Tanguy Struye de Swielande, Dorothée Vandamme, David Walton, and Thomas Wilkins, 19–31. Milton: Taylor & Francis Group.

- Suryadinata, Leo. 2018. “Indonesia and Its Stance on the ‘Indo-Pacific’.” ISEAS Perspective 66, October 23. https://www.iseas.edu.sg/images/pdf/[email protected].

- Tan, See Seng. 2020. “Consigned to Hedge: South-East Asia and America’s ‘Free and Open Indo-Pacific’ Strategy.” International Affairs 96 (1): 131–148. https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiz227.

- Taylor, Brendan. 2020. “Is Australia’s Indo-Pacific Strategy an Illusion?” International Affairs 96 (1): 95–109. https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiz228.

- Teo, Sarah. 2022. “Toward a Differentiation-Based Framework for Middle Power Behavior.” International Theory 14 (1): 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1752971920000688.

- Thies, Cameron G., and Agguntari C. Sari. 2018. “A Role Theory Approach to Middle Powers: Making Sense of Indonesia’s Place in the International System.” Contemporary Southeast Asia: A Journal of International and Strategic Affairs 40 (3): 397–421. https://doi.org/10.1355/cs40-3c.

- Wallis, Joanne. 2020. “‘Is It Time for Australia to Adopt a ‘Free and Open’ Middle-Power Foreign Policy?” Asia Policy 27 (4): 7–20. https://doi.org/10.1353/asp.2020.0053.

- Wallis, Joanne, Sujan R. Chinoy, Natalie Sambhi, and Jeffrey Reeves. 2020. “A Free and Open Indo-Pacific: Strengths, Weaknesses, and Opportunities for Engagement.” Asia Policy 27 (4): 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1353/asp.2020.0051.

- Weatherbee, Donald E. 2019. “ASEAN, and the Indo-Pacific Cooperation Concept ISEAS Perspective No.47.” Indonesia, June 7. https://www.iseas.edu.sg/images/pdf/ISEAS_Perspective_2019_47.pdf.

- Wendt, Alexander. 1999. Social Theory of International Politics, Cambridge Studies in International Relations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Widmaier, Wesley M. 2019. “Australian Foreign Policy in Political Time: Middle Power Creativity, Misplaced Friendships, and Crises of Leadership.” Australian Journal of International Affairs 73 (2): 143–159. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10357718.2019.1570486.

- Wilkins, Thomas, and Jiye Kim. 2022. “Adoption, Accommodation or Opposition? – Regional Powers Respond to American-Led Indo-Pacific Strategy.” Pacific Review 35 (3): 415–445. https://doi.org/10.1080/09512748.2020.1825516.

- Wirth, Christian, and Nicole Jenne. 2022. “Filling the Void: The Asia-Pacific Problem of Order and Emerging Indo-Pacific Regional Multilateralism.” Contemporary Security Policy 43 (2): 213–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/13523260.2022.2036506.

- Yang, Florence. 2019. “Asymmetrical Interdependence and Sanction: China’s Economic Retaliation over South Korea’s THAAD Deployment.” Issues and Studies. Institute of International Relations 55 (4): 1–39. https://doi.org/10.1142/S10132.51119400083.

- Zeng, Xianghong, and Shaowen Zhang. 2021. “From “Asia Pacific” to “Indo Pacific”: The Adjustment of American Asia Pacific Strategy from the Perspective of Critical Geopolitics.” East Asian Affairs 1 (02): 2150009. https://doi.org/10.1142/S2737557921500091.

- Zhang, Feng. 2019. “China’s Curious Nonchalance towards the Indo-Pacific.” Survival 61 (3): 187–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/00396338.2019.1614791.