ABSTRACT

China is an important security concern for the United States and its allies, including the Five Eyes intelligence-sharing group that is sometimes described as the core of the ‘Anglosphere’ security community. While we would expect securitising discourses at the elite level to reproduce some common perceptions of China, to what extent are attitudes to China shared across the publics in these countries? In this article, we unpack public attitudes towards China in the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. Drawing on the results of public opinion surveys we conducted in 2022, we note areas of similarity and divergence then drill down into the drivers of public attitudes. We show that even though aggregate attitudes towards China in the five countries appear to align with official security discourses, this hides significant variation in how different groups within these societies view China. In particular, ethnic minorities and recent immigrants, along with members of higher socio-economic classes, urban residents, and young people, tend to be more positive towards China. Our findings bring new insights into the potency of government-driven securitisation, particularly in terms of identifying groups within societies that are less inclined to follow their government’s view of China.

Introduction

In late 2022, the Biden administration’s National Security Strategy described China as ‘America’s most consequential geopolitical challenge’ and stated that the United States would ‘prioritize maintaining an enduring competitive edge over the PRC’ (The White House Citation2022, 11, 23). A few months later, the United States House of Representatives passed a resolution establishing a new Select Committee on the Strategic Competition between the United States and the Chinese Communist Party (US Congress Citation2023). At its first hearing, titled ‘The Chinese Communist Party’s Threat to America,’ its Chairman described relations with China as ‘an existential struggle over what life will look like in the twenty-first century’ and announced that the ‘era of wishful thinking [about economic engagement with China] is over’ (The Select Committee on the CCP Citation2023). The many tensions in the relationship between the two countries that came to prominence in the years following President Trump’s election in 2016 were not resolved by the subsequent change in US leadership and there now seems to be a well-established consensus within the US foreign policy community that the United States is in direct competition with China.

This hardened position in the United States has been accompanied by a diplomatic push to convince its partners around the world to adopt a similar viewpoint – a process Friis and Lysne (Citation2021, 1176) describe as an ‘attempt at comprehensive macrosecuritization of China’. While this is not always an easy task for the United States, one group of staunch US allies has been particularly supportive of its foreign policy. In recent years, the four other countries that, along with the United States, make up the intelligence-sharing group known as the ‘Five Eyes’ and are sometimes referred to as the core of the ‘Anglosphere’ (Mycock and Wellings Citation2019, 1) – Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom – have also shifted from relatively friendly positions towards China to much more adversarial stances. As close allies with a long history of cooperation in war (Holland Citation2020; Vucetic Citation2011b), it is perhaps unsurprising that in recent years policy networks and shared securitising discourses at the elite level among the members of this security community have reproduced some common perceptions of and responses to China. But are publics in these five countries as worried about China as their governments, to what extent are public attitudes to China similar across this group of countries, are these attitudes driven by similar concerns, and how much variation in attitudes do we see within each country?

Public opinion matters to security communities because the public’s sense of shared identity, values, and worldview also underpins a security community’s integration and cooperation. While research into security communities often focuses on discourse and networks at the elite level, looking at mass attitudes allows us to examine whether elite-level securitising discourses are also reflected in public views. In this article, we explore the security community of the Anglosphere core by examining public attitudes to China in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States, testing to what extent perceptions of China as an external power and potential threat are shared across the five countries. We compare the drivers of attitudes to China in each country, differentiating between socio-demographic factors, perceptions of China’s national image, and attitudes to issues that have been the subject of security concerns about China across the group. This allows us to look beyond aggregate public opinion about China to examine more closely the variation between different social groups’ attitudes within each country and to see whether attitudes to specific issues that have been the focus of securitising discourses are associated with positive or negative views of China in either a consistent or varied way.

The article begins by defining the Anglosphere and the Five Eyes, explaining how the grouping of the five selected countries constitutes a security community and providing an overview of how their official relations with China have taken a similarly fractious turn since the late 2010s. We then present the results of a public opinion survey we fielded in all five countries in 2022, comparing public attitudes to China across the group. Here we note that while attitudes to China are generally negative across a range of issues, New Zealanders are notably more positive than the rest. At the same time, despite the US government often taking the lead in criticising China, Americans do not stand out as the most negative or concerned about China, but they are the most internally divided.

Subsequently, we move to identify factors that would help us understand and explain public attitudes. We find that across the five countries, non-White ethnic minorities and recent (i.e. first and second generation) immigrants – but also members of higher socio-economic classes, urban residents, and young people – tend to be more positive towards China, perhaps seeing it more as an opportunity rather than a threat. Interestingly, the differences across the five countries can be largely explained by the same structure of driving forces, particularly by the assessment of Chinese foreign policy. Anglosphere publics also share a broad concern about China’s threat to democracy. Our results show that even though aggregate public attitudes towards China appear to be in line with official security discourses, this hides significant variation in the way that different groups within these societies view China. Our findings bring new insights into the potency of government-driven securitisation, particularly in terms of identifying social groups that are less inclined to follow their government’s view of China. We also suggest that our survey data can serve as the basis for future studies.

The Anglosphere, the Five Eyes and security communities

The Anglosphere is an ambiguous concept rather than a formal grouping of states. Despite its political proponents pointing to shared liberal democratic and capitalist values, cultural ties, military campaigns and immigration history as the foundation for deep bonds between certain English-speaking countries, the concept of the Anglosphere is rarely acknowledged in public discourse due to its association with imperialism and racism (Mycock and Wellings Citation2019, 1). The concept has been employed critically by researchers seeking to understand the national and international politics of English-speaking states, often focusing on identity politics (e.g. Holland Citation2020; Wellings Citation2019; Vucetic Citation2011a), but there is no clear agreement on exactly which countries fall within the group. Ravenhill and Heubner’s (Citation2019) political economy approach includes every country that was at some time part of the British Empire, choosing to focus on the ten largest economies among them, while Holland’s (Citation2020) constructivist analysis examines an Anglosphere inner core of just the USA, UK and Australia. A common approach, however, which we follow here, is to treat the Anglosphere ‘core’ as consisting of Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the UK and USA (Legrand Citation2015; Mycock and Wellings Citation2019; Vucetic 2011b). For the purposes of our study, we are interested in examining these five states as a security community whose members not only view internal military conflict between them as unthinkable but also have a shared sense of external threat – in this case from China.

The five core Anglosphere countries have been described by Vucetic (2011b, 30) as a ‘security community par excellence’. A security community, a concept first developed by Deutsch (Citation1957), is an integrated group of people with a shared expectation that social problems among them will be resolved through peaceful means rather than physical violence. Adler and Barnett (Citation1998) later re-examined the concept from a constructivist perspective, identifying different stages in the development of a security community while emphasising that both transnational and inter-state interactions contribute to the building of trust, shared interests and even collective identities that make war between members of the community unthinkable. Through this logic, the shared identity binding the Anglosphere core has resulted in ‘two centuries of peaceful change’ among its members (Vucetic 2011b, 30).

Interactions between societies, not just between states or elites, contribute to the construction of a security community (Adler and Barnett Citation1998, 14). Bellamy (Citation2004, 39) distinguishes between epistemic communities, consisting of direct interactions between elites, and transversal communities, consisting of direct and indirect interactions between national civil societies, arguing that both contribute to the construction of a security community. The ‘practice turn’ in IR theory and Adler’s central involvement in that turn meant that the development of the security community concept has mainly focused on interactions between security elites as ‘communities of practice,’ rather than on how the public in different states might develop a sense of shared identity. Nevertheless, there has been some recognition of the ways in which the mass public might matter for the construction and maintenance of a security community. In his discussion of the cognitive evolution of communities of practice, Adler (Citation2008, 214) notes that NATO used public opinion campaigns to increase support for joining the security community in Central European countries. Researchers have also used public opinion as evidence for the decline of a security community (Risse Citation2016, 34–36) or for its absence, as in the case of ASEAN (Chang Citation2016, 344). While public opinion does not provide the whole picture of a security community, it does offer some insight into the shared identities and values that Risse (Citation2016, 26) views as the key driver of cooperation.

Being closely linked to the formation of shared identity, security communities are necessarily also involved in processes that draw distinctions between insiders and outsiders. If security communities are constituted by ongoing international and transnational interactions between institutions and elites who share a sense of identity, interests, and purpose (Adler Citation1997, 253), then we could reasonably expect members of the community to also have overlapping views on what threatens their interests or values. From this perspective, membership in a mature security community is an internalised norm that shapes the construction of identities, interests, and other views of the world, including the legitimacy of policies and behaviour (Bellamy Citation2004, 7). Not only does membership in a security community tell us who ‘we’ are, it also ‘tells us who "they" are, what "they" are doing, and whether or not "they" constitute a problem’ (Bellamy Citation2004, 9). While trust and tolerance towards out-groups are generally higher within security communities than in states that are not part of such communities (Tusicisny Citation2007), and different security communities can have relationships with outsider neighbours ranging from engagement to confrontation (Bellamy Citation2004), security communities are systems of shared meanings where ‘people institutionalize commonalities running through the whole region, including shared perceptions of external threats’ (Adler Citation1997, 254). So although security communities are unlike traditional alliances in that they are constituted by their shared values and identities rather than shared perceptions of threat (Risse Citation2016, 25), and research into security communities has been more concerned with understanding how members of these communities come to no longer view each other as threats than with the process by which they develop a sense that they share common external enemies, there is a clear conceptual link between membership in a security community and perceptions of potential threats from outside the community.

Although the Anglosphere is not a formal institution, the five core states are linked by a web of transgovernmental policy networks in a range of areas, with security cooperation as an important and longstanding focus (see Legrand Citation2015, 2019). The annual Five Country Ministerial brings together home affairs, immigration, and security ministers from across the group, but it is the Five Eyes intelligence-sharing agreement that is the most prominent of these arrangements. Given a much greater public profile by the Edward Snowden leaks in 2013, the Five Eyes arrangement is what Vucetic (Citation2019, 81) calls the core of the ‘Anglosphere in security’. Five Eyes members point to the exceptional closeness and longevity of this security relationship, and to their shared values, such as democracy and the rule of law (Legrand Citation2019, 70–71). Researchers note that this Anglosphere core is unusually willing to follow the United States into war (Vucetic 2011b), and describe it as a security community ‘bound by a shared identity forged through racialised conflicts and their subsequent retelling in national mythology’ (Holland Citation2020, 60). While Anglosphere scholarship has examined the origins of this shared identity and its foreign policy implications (see Wellings and Mycock (eds.) Citation2019; Wellings Citation2019), the question of whether there is a shared view on China across the Anglosphere publics is yet to be explored. As relations between the United States and China become more adversarial, will we see public views within the Anglosphere converge, such that rallying behind the United States as it confronts its great power rival is perceived to be the most obvious and logical course of action?

Convergence of government positions on China

From the late 2010s to early 2020s, official relations with China significantly chilled across all five countries. In the United States, tensions over trade increased after Trump took office and continued under President Biden, with disputes over Covid, Taiwan and spy balloons periodically flaring up. In Canada, the arrest of Huawei deputy chair Meng Wanzhou in 2018, and China’s subsequent retaliatory detention of Michael Spavor and Michael Kovrig, triggered a steep dive in relations between the two countries (Paris Citation2020). The Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) also claimed that China was involved in a campaign to interfere in the 2021 federal election (Fife and Chase Citation2023). Since 2014, when Xi Jinping was given the rare honour of addressing the Australian federal parliament, relations between China and Australia have soured over accusations of China’s interference in Australian domestic politics, claims of Chinese hacking, the detention of Australian citizens Cheng Lei and Yang Hengjun in China, former Prime Minister Scott Morrison’s call for an independent inquiry into Covid’s origins, and Australia’s criticism of China at the United Nations over its conduct in the South China Sea (BBC Citation2022). In the UK, a high point in 2015, when the then-PM David Cameron referred to a ‘golden era’ of relations and invited Xi for a state visit, was followed by rising tension, albeit less acute than in Australia. China’s policies in Hong Kong were a particular focal point for disagreement and in November 2022 the new Conservative PM Rishi Sunak used his first major foreign policy speech to publicly announce that the so-called golden era was over (Allegretti Citation2022). In New Zealand, there has been somewhat less antagonism between the two governments, but there have been accusations of interference in domestic politics, with both major political parties suffering scandals over MPs with inappropriate links to China (McCulloch Citation2021).

There is also evidence that foreign policy views across the five countries are converging towards a position where China is openly represented as a strategic competitor and even a threat. In October 2023, the heads of all five countries’ security services made an unprecedented joint public appearance, warning of the threat posed by China’s attempts to steal technology from private companies (Corera Citation2023). The USA, UK, and Australia have further formalised their security concerns through the establishment of the AUKUS security pact, which has been widely interpreted as being driven by perceptions of a Chinese security threat (e.g. Edel Citation2021). The 2022 United States National Security Strategy describes China as its ‘most consequential competitor’ (The White House, 12). The UK’s 2021 Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy calls China a ‘systemic competitor’ (Cabinet Office Citation2021, 26), while Australia’s 2023 National Defence Statement describes competition between China and the USA as ‘the defining feature of our region and our time’ and claims that China is ‘engaged in strategic competition in Australia’s near neighbourhood’ (Australian Government Citation2023, 23). Although New Zealand’s National Security Strategy is somewhat more circumspect, identifying China’s assertive role in regional strategic competition while also noting the need for continued engagement with China (New Zealand Government Citation2023, 4–5), and Canada does not currently have a singular document outlining its national security strategy, there are other indications that policymakers’ views across the five countries appear to have converged, particularly in relation to concerns about information security and interference by China in domestic democratic institutions.

The Australian government excluded Chinese telecommunications company Huawei from participating in the rollout of its 5G network in 2018, and the following year the company was banned from doing business with any US organisations. Also in 2018, New Zealand’s security services blocked a proposal from a local telecommunications company to use Huawei equipment in its 5G infrastructure (Jolly Citation2018), although this did not amount to a formal ban (Thomas Citation2020). In July 2020 the UK announced it would be removing Huawei equipment from its 5G networks and Canada announced a similar ban in May 2022. In early 2023 the United States banned federal employees from using TikTok over concerns that the app, which is owned by Chinese company ByteDance, poses a security risk. The other four countries rapidly followed suit, although the New Zealand ban only applied to MPs, not all government workers.

Primarily driven by concerns over political interference from China, the United States’ Foreign Agent Registration Act (FARA) has been recently emulated in Australia, with the introduction of its Foreign Influence Transparency Scheme Act. Britain has also introduced a new Foreign Influence Registration Scheme, and Canada has begun developing a similar legal mechanism in response to accusations of China’s interference (Ho Kilpatrick Citation2023). New Zealand does not have an equivalent law but took steps to ban foreign political donations in late 2019.

There has been a great deal of sharing of information across elite networks in the five countries on this issue of China’s interference in democratic processes and institutions, with the five governments often making reference to the experiences and decisions of the others. In July 2022 the directors of the FBI and MI5 gave a joint statement warning of the threat posed by the Chinese Communist Party (MI5 Citation2022), and when New Zealand banned foreign political donations the government minister’s statement referenced laws in Canada, Australia and the UK (Little Citation2019). A Canadian parliamentary security report noted Canada’s relative lack of awareness of foreign interference activities in comparison to the widespread view in Australia, New Zealand and the United States that they represent a significant threat (National Security and Intelligence Committee of Parliamentarians Citation2020, 56), and cited research and policy advice from Australia and New Zealand (ibid, 60, 67), as well as a US government report critical of China’s Confucius Institutes (ibid, 71). The Canadian report included a nearly four-page section outlining how foreign interference threatens the other four countries (ibid, 72-75). In 2019, a UK Foreign Affairs Committee report also noted that in Britain there had been relatively little attention to the issue of Chinese interference compared to the prominent debate in Australia, New Zealand and the United States (House of Commons Foreign Affairs Committee Citation2019, 5). Australian academics and experts have given testimony at US government hearings on China’s interference activities (U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission Citation2023; House Armed Services Committee Citation2018), and one prominent New Zealand academic, Professor Anne-Marie Brady, has briefed officials in all four other countries on the issue of China’s international interference (Nippert Citation2019).

This close relationship not only facilitates policy makers’ mutual learning and comparison, it also generates pressure to conform on issues of national security. A report published in 2018 by the CSIS referred to New Zealand as the ‘soft underbelly’ of the group due to its vulnerability to Chinese interference (Walters Citation2018), and in the same year, a former CIA analyst argued that New Zealand’s membership of the Five Eyes group needed to be reconsidered for the same reason (Roy Citation2018).

It is not always the case that US policies towards China are replicated wholesale across the group. All four non-US countries have joined the China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, despite US opposition to the institution, and Australia and New Zealand are also members of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) alongside China. New Zealand’s former PM Jacinda Ardern at times pushed back against recent attempts by the United States and others to frame the current international environment as one of systemic competition between democracies and authoritarian states (Miller Citation2022). Nevertheless, there is solid evidence that policymakers’ views of China as a security threat are becoming more closely aligned in the five countries. But do we see a similar picture when we look at public opinion?

Methodology

Our empirical analysis relies on data from a large-scale online public opinion survey we conducted in each of the five countries in 2022.Footnote1 The USA, UK, and Canada were surveyed in July-September 2022 with 1500 respondents per country while Australia and New Zealand were surveyed in April-June 2022 with 1200 respondents per country. All samples were representative of the general population according to quotas of gender, age, and region within the country. The USA, UK, and Canada’s samples were also representative according to the education level and rural-urban divide. In the USA, the sample also represented domestic ethnic divisions, while in Canada, it represented language divisions (the respondents had the option to answer in either English or French). The questionnaires consisted of more than 200 questions on areas including general social attitudes, political and international attitudes, and specific views on China, alongside a standard battery of demographic questions. Ethical approval was granted by the Palacký University Olomouc ethics board and surveys were conducted according to the ICC/ESOMAR International Code on Market and Social Research.

Descriptive statistics

Public views of China across the Anglosphere

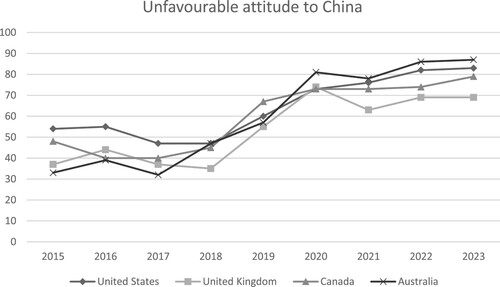

Before we examine our data it is first useful to identify whether official tensions are generally reflected in public opinion on China across the five countries. Here we also see some indication of convergence. For aggregate views of China over time across the allied countries (excluding New Zealand) we can look to Pew surveys conducted annually between 2015Footnote2 and 2023 (see Pew Research Centre Citationn.d.; Citation2023). Not only did public opinion towards China turn sharply negative during this period, there was also a close alignment of opinion across the group (). The greatest negative shift occurred in Australia, which recorded a 54-point increase in unfavourable views, with unfavourable attitudes in the other three countries increasing by 29 (USA), 31 (Canada) and 32 (UK) points.

Figure 1. Unfavourable attitudes towards China (percentage of respondents reporting negative attitudes). Source: Pew

There is no Pew data for New Zealand before 2021, but we can compare annual Asia New Zealand Foundation surveys to assess changing views. A 2017Footnote3 poll found that 62% of respondents thought that China was friendly and 18% thought that China was a threat (Asia New Zealand Foundation Citation2018, 37–39). Since then threat perceptions have increased significantly, with the 2021 and 2022 surveys both finding that 37% viewed China as a threat and only 29% and 30% viewed China as a friend, respectively (Asia New Zealand Foundation Citation2022, 20; Citation2023, 22–23).

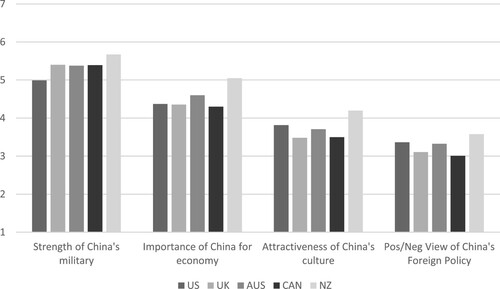

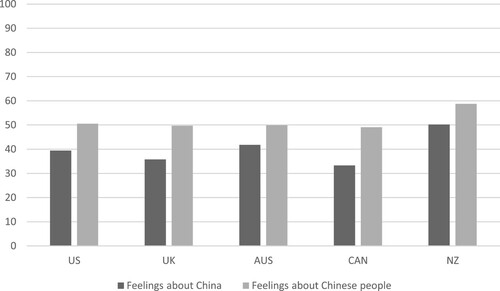

Looking at our own survey data from 2022 we can compare recent attitudes to China across a wide range of areas. Besides other issues, we asked respondents to evaluate China in terms of four key aspects of its national image: the strength of its military, its importance for their own country’s economy, the attractiveness of its culture, and whether they viewed its foreign policy positively or negatively. We also asked about their feelings about the Chinese people, and their overall positive or negative feelings about China. For the first four questions, we used a seven-point Likert scale where 1 was very weak/unimportant/unattractive/negative and 7 was very strong/important/attractive/positive. For respondents’ feelings about the Chinese people and overall feelings about China, we used a thermometer scale of 0-100, where 0 was the most negative and 100 the most positive.

On the four image questions, we found the responses across the five countries to be strikingly similar. Mean views of China’s military strength ranged from a low of 4.99 in the United States to 5.67 in New Zealand; views of economic importance ranged from 4.30 in Canada to 5.05 in New Zealand; average perceptions of cultural attractiveness were the lowest in the United Kingdom at 3.48 and highest in New Zealand at 4.20; and views of China’s foreign policy were most negative in Canada with an average of 3.01 and most positive (or, more accurately, least negative) in New Zealand with a mean of 3.58 ().

Figure 2. Perceptions of various areas related to China (mean values). Source: Own data (Sinophone Borderlands)

On the question of overall feelings about China, New Zealand was the only country where the mean view reached the neutral mark (M = 50.23), with Australia (M = 41.80), the United States (M = 39.42), the UK (M = 35.78) and Canada (M = 33.27) all having an average view of China that was more negative than positive (). Attitudes toward the Chinese people were essentially neutral in four of the countries, with only New Zealand’s mean response (M = 58.77) a clear distance from the midpoint.

Figure 3. General favourability of China and of Chinese people (mean values). Source: Own data (Sinophone Borderlands)

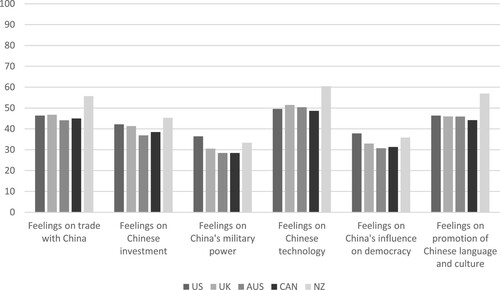

Digging deeper into more specific areas we also asked respondents about their feelings on six issues where there has been tension between China and Western democracies: trade with China; Chinese investment; China’s military power; Chinese technology; China’s influence on democracy; and the promotion of Chinese language and culture (). Here, we again used the thermometer scale of 0-100. On three of these questions – trade with China, Chinese technology, and promotion of Chinese language and culture – New Zealand was the clear outlier, with the other four countries recording mean results very close to one another and well below the New Zealand mean. On trade, the four countries’ mean results ranged from Australia’s 44.17 to the UK’s 46.76, with New Zealand at 55.79. On Chinese technology, they ranged from Canada at 48.68 to the UK at 51.52, with New Zealand at 60.48. On Chinese language and culture promotion, mean responses ranged from Canada’s 44.23 to the United States’ 46.37, with New Zealand’s mean again much higher at 56.96.

Figure 4. Assessment of various areas of interaction with China (mean values). Source: Own data (Sinophone Borderlands)

Looking at responses across the five countries we can make a few initial observations. The first is that while average views of China in the other four countries are quite similar across the range of issues, New Zealand is the consistent outlier of the group. The New Zealand public is more positive about China on every question except for feelings on China’s military and China’s influence on democracy, where the United States is slightly more positive (or less negative). New Zealanders also view China’s military as stronger, its economy as more important and its culture as more attractive than the publics in the other four countries.

The second observation is that the United States public is not consistently the most negative or concerned about China, despite years of strong US government and elite rhetoric about the strategic threat China poses to US interests. Americans on average view Chinese culture as more attractive and have a less negative view of China’s foreign policy than their counterparts in Australia, Canada and the UK. They also view China’s military and economy as less strong on average and are less concerned about Chinese investment and China’s influence on democracy than the public in Australia, Canada and the UK, and are the least worried about China’s military power.

Societal divisions concerning attitudes towards China

Looking closer at various domestic divisions within the five countries can help us understand attitudes towards China. To begin, there are no notable differences in attitudes between genders. With education levels, those with tertiary education are slightly more positive towards China than those with primary and secondary. Similarly, younger respondents were more positive than older ones. Those living in big cities tend to be somewhat less negative towards China than those living in smaller cities and rural areas.

There are some noteworthy regional differences in the USA – overall sentiment towards China is almost neutral in California (mean value 49), and only slightly negative in states such as New York (45), Florida (44), and Texas (43). In the remaining four countries, the regional differences are less pronounced, but a similar pattern exists: London ends up with the most positive attitude towards China (43) in the UK, Auckland the most positive in New Zealand (53), and Victoria (44) the most positive region in Australia (besides the Australian Capital Territory, which was slightly more positive).

Those self-identifying as being members of the highest socio-economic class (from among five classes given as options to choose from) have substantially more positive views of China (55) than those self-identifying as belonging to other classes (42-32 mean value).

Those who reported being very happy are about 10 percentage points more positive towards China than those who are very unhappy. Even bigger differences exist in terms of expected life quality in future – those who expect their life to be much better in the future are substantially more positive towards China than those who expect their life quality to be much worse. We got similar results when checking for differences based on satisfaction with the political situation in the country and on individuals’ own economic well-being.

We also see important ethnic divisions, especially in the United States. While those self-identifying as White are negative towards China (34 mean value), others are neutral (Black at 51, Latino at 49, and Asian at 48). Similar findings also exist in other countries, although less pronounced.

A similar picture emerges when taking into account family background in terms of immigration. In the USA, first and second-generation Americans are substantially less negative about China than third-generation (or more) Americans, with a difference of about 17 percentage points. The differences in the UK, Australia, and Canada were of similar direction but substantially smaller, while in New Zealand, the differences were not noteworthy ().

Table 1. General assessment of China in five countries according to family background (mean values, 0 being most negative, 100 most positive, 50 neutral).

Similarly, political divisions based on party affiliation and voting preference exist especially in the USA: Republicans (33), Democrats (44), and Independents (38) differ in terms of their views of China, although the differences are not as large as in terms of ethnic divisions. In the other four countries, the differences between the voters of various (major) political parties are less pronounced (i.e. less than 10 percentage points). In the UK, Conservative party voters (32) are only slightly more negative than those who vote for the Labour Party (37), Liberal Democrats (37), and Scottish National Party (42). In Canada, Bloc Quebecois voters (29) are slightly more negative than those who vote for the Liberal Party (35), Conservative Party (30), or New Democratic Party (34). In Australia, supporters of the Australian Labor Party (43) and the Liberal Party (40) have similar views, with Australian Greens voters (50) being somewhat less negative and those who vote for the populist right-wing One Nation party being substantially more negative (29). Finally, in New Zealand, there are almost no differences between those who vote for the Labour Party (53), National Party (48), and Green Party (50).

Social interaction was found to play a role. Those who have never travelled to China are substantially more negative than all others. Similarly, and even more importantly,Footnote4 those who never interact with Chinese people (from the PRC) are substantially more negative than those who interact often. At the same time, respondents in New Zealand reported interacting with Chinese people the most often from among the five countries (mean value of 4, where 0 represented never interact and 10 represented interact very often), while respondents in the UK reported the least interaction (2.2).

To sum up the findings so far, across the five countries, those who are more educated, live in more developed regions, self-identify with higher socio-economic classes and are generally satisfied with their economic well-being and their country’s political situation tend to have more positive views of China than those living on the peripheries, less educated, unsatisfied, and expecting their life to get worse. This may suggest that China is seen as an opportunity to benefit among those who are better off while it is seen as a threat by those who are already worse off.

At the same time, respondents belonging to the ethnic majority and those who are third-generation citizens (or more) of the given country, who we would expect on average to be more privileged in socio-economic terms, tend to be more negative than members of minority groups and more recent immigrants. This may, in turn, suggest that minorities were less susceptible or willing to follow the securitisation discourses of China by their governments.

These divisions are especially visible in the USA, where China seems also to be an issue of political contestation fought largely between the groups defined by socio-demographic features, such as ethnicity, age, or class. In the remaining four countries, the socio-demographic and political divisions are less visible when it comes to attitudes towards China, suggesting that relations with China are not so politically contested and there is higher consensus between various sections of societies.

Finally, social interaction does seem to matter – those interacting with Chinese people more often tend to be more positive towards China. The fact that respondents in New Zealand report higher levels of interaction than others may play a role in the fact that it is the country with the most positive attitude towards China.

Regressions

To test and estimate the relative strength of the driving forces, we ran a series of regression analyses. We separately tested three models for each of the five countries. Model 1 included only the socio-demographic variables (age, education level, urban-rural divide, happiness, expected life quality in the future, satisfaction with own economic well-being and with the political situation in the country, and interaction with Chinese people). Model 2 also included the four variables representing important elements of China’s national image: the military strength of China, the economic importance of China for the respondent’s own country, the cultural attractiveness of China, and the assessment of Chinese foreign policy. Model 3 (the full model) also included the six variables representing issues where there has been tension or debate over relations with China: the assessment of trade with China, Chinese investment, Chinese technology, China’s influence on democracy in other countries, the promotion of China’s language and culture, and China’s military power. The dependent variable in each of the models was the general attitude towards China.Footnote5

To highlight a few most noteworthy results from the regressions, we observe that the five countries generally behave similarly in the three models. Model 1 has the strongest predictive power in the USA and the weakest in New Zealand, which is in line with the findings of the previous section. Model 2 and Model 3 have similar predictive strength across all five countries, without clear outliers or diverging patterns ().

Table 2. Adjusted R2 for the three regression models across the five countries.

As for the relative strength of the individual variables, in Model 1 we see similar results across all five countries. In Australia, interaction with Chinese people has a strong positive impact (.331), while age has a medium negative impact (-.171). Only satisfaction with the political situation was another significant predictor, with a weak positive impact. In the USA, interaction with Chinese people and age have similar impacts as in Australia (age is even stronger at −.202 while interaction is at .313). Satisfaction with the political situation also has quite a strong impact (.168), while expected future quality of life is also a statistically significant predictor. In Canada, age is an even stronger predictor than in the USA (−.220), while satisfaction with the political situation and interaction with Chinese people are both medium strength. Education and expected future quality of life are also statistically significant predictors. In the UK, interaction with Chinese people and age have similar impacts as in other countries (.266 and −.215), while expected future quality of life and satisfaction with the political situation are also statistically significant. In New Zealand, interaction with Chinese people and age both have similar although weaker impacts, but satisfaction with the political situation has a stronger impact. Expected future quality of life is also a statistically significant predictor.

In Model 2, we find that in the UK, the assessment of Chinese foreign policy and the cultural attractiveness of China are the strongest predictors (.276 and .257), while interaction with Chinese people is only slightly weaker. Expected quality of life and age remain statistically significant. In Canada, Chinese foreign policy is the strongest predictor (.376), and cultural attractiveness is weaker than in the UK (.169). Age, interaction with Chinese people, and satisfaction with the political situation remain significant. Perception of China’s military as strong has a negative (although weak) impact. In the USA, Chinese foreign policy is the strongest predictor (.295), ahead of the interaction with Chinese people, China’s cultural attractiveness, and age. Satisfaction with the political situation remains statistically significant, while the economic importance of China is a statistically significant, although weak, predictor. In New Zealand, Chinese foreign policy was the strongest predictor (.329) ahead of the cultural attractiveness and interaction with Chinese people. The economic importance of China was found to be a statistically significant, although weak, predictor. In Australia, the assessment of Chinese foreign policy was again found to be the strongest predictor ahead of the cultural attractiveness of China and interaction with Chinese people. In addition, the economic importance of China was found to be a medium-strength predictor (.116) and age remained statistically significant.

In Model 3, looking at Australia, only interaction with Chinese people remained statistically significant from the first model. Assessment of Chinese foreign policy remained the strongest predictor, ahead of assessment of China’s influence on democracy, and China’s cultural attractiveness. Other significant predictors were Chinese technology, China’s military power, trade with China, and economic importance of China. In New Zealand, none of the variables from the first model were significant. The strongest predictor was China’s influence on democracy in other countries (though only at .177) slightly ahead of other variables of the cultural attractiveness of China, Chinese foreign policy, the promotion of China’s language and culture, Chinese technology, Chinese investments, and trade with China. In the USA, age and interaction with Chinese people remained statistically significant from the first model. Assessment of Chinese foreign policy was the strongest predictor (.190), slightly ahead of Chinese technology, China’s military power, China’s influence on democracy in other countries, and cultural attractiveness of China. In Canada, only satisfaction with the political situation remained statistically significant from the first model (although weak). The strongest predictor was the assessment of Chinese foreign policy (.235) ahead of China’s influence on democracy in other countries, cultural attractiveness, military strength (negatively), assessment of China’s military power, trade with China, and the economic importance of China. Finally, in the UK, age and interaction with Chinese people remained statistically significant from the first model. The strongest predictor was cultural attractiveness, ahead of the assessment of Chinese foreign policy, China’s influence on democracy in other countries, assessment of China’s military power, trade with China, and China’s military strength.

Economic factors played only marginal roles in driving views. In particular, the perception of China as economically important did not prove to be a factor driving perceptions of China (either in positive or negative directions). This is noteworthy because economic (inter)dependence is often presented as being the reason why various countries would adopt softer positions on China. However, our results suggest that, for the public at least, it is plausible that views of a close economic relationship with China could be associated both with negative feelings where the relationship is perceived as one of vulnerability and with positive feelings where the relationship is perceived as one of opportunity. In any case, we did not find evidence to support a claim that perceptions of close economic integration would lead to a warmer attitude toward China.

While attitudes to China’s foreign policy are a key factor in people’s overall assessment of the country throughout the Anglosphere, UK opinion diverges slightly. With its geo-strategic distance from China being the greatest of the five countries, in the UK China’s foreign policy is less salient than Chinese culture in shaping general attitudes.

Of the six issue areas we looked at where there have been tensions over relations with China, attitudes to China’s influence on democracy was the strongest predictor of overall positive or negative views of the country across the Anglosphere, except for the United States, where the technology issue was the stronger predictor. For Americans, rivalry with China over technology appears more salient than concerns about any Chinese threat to democracy.

Conclusion

By conducting the first in-depth quantitative analysis of public opinion comparing the five Anglosphere states’ views on China – a significant external ‘other’ – this article lays the groundwork for future research into the similarities and differences of public attitudes towards international affairs across the Anglosphere. We find that Anglosphere public attitudes to China are not only similar but are driven by broadly similar factors across the group, despite significant differences in the five countries’ size, geographic location, and international power. Public attitudes to China are strongly associated with China’s foreign policy image, as well as the issue of China’s threat to democracy. As political and security elites across the group share concerns about China’s interference in liberal democracies and increasingly assertive foreign policy, their publics’ views of China are also being affected by these issues. Publics in all five countries are generally negative towards China across a range of areas, although New Zealanders stand out as the most positive. At the same time, our study also shows that, at least when it comes to public attitudes, the claim that New Zealand is the ‘soft underbelly’ of the Five Eyes group with respect to China is only partly true. While New Zealanders are outliers in having more positive views on the issues of Chinese technology and trade, they are also more concerned about China’s military power and influence on democracy than their US counterparts. Moreover, despite the US government often taking the lead in criticising China, Americans are not the most negative – but they are the most internally divided.

However, consistency in aggregate opinion can also obscure the ways in which different national publics within a security community exhibit their own distinct dynamics when it comes to specific issues and images linked to a foreign state. In the United States, concerns over Chinese technology are more salient than in the other four countries, reflecting awareness of peer competition between these two high-tech rivals. The United Kingdom stood out in that it was the perception of Chinese culture, not of China’s foreign policy, that we found to be the most significant driver of attitudes toward China. This may be due to the UK being the most geopolitically distant from the Indo-Pacific region of the five countries and a corresponding lesser attention to Chinese foreign policy in British public discourse, at least in comparison to more proximate concerns, such as Russia or the Middle East. In New Zealand, the link between the high level of self-reported interaction with Chinese people and the relatively positive views of China in comparison to the other four countries is more significant.

Importantly, views of China vary significantly between members of different societal groups within the five countries, with divisions being the most pronounced in the USA, especially when it comes to different ethnic groups, recent migrants, and voting preferences, but also other socio-demographic characteristics. On the one hand, non-White ethnic minorities and more recent migrants show significantly more positive attitudes towards China (overall having neutral sentiment) than the majority White population. On the other hand, urban residents, young, more educated and generally more well-off people tend to be more positive towards China. Both of these findings suggest there is a limited impact of the elite securitising discourse on various sections of populations (although exact reasons may vary between the given divisions). Moreover, the fact that these divisions are comparatively more present in the USA than in the other four studied countries is a finding with policy relevance that merits further research.

In two areas in particular our quantitative findings intersect with previous qualitative work on the Anglosphere and deserve to be the subject of future research. First, we find that perceptions of China’s threat to democracy are especially salient compared to other issue areas in the four non-US members of the group. Anglosphere advocates have pointed out that a central aspect of the group’s collective identity is a shared commitment to liberal democracy (see Mycock and Wellings Citation2019, 9). However, scholars have not yet considered whether contemporary attitudes and policies towards China might help reproduce Anglosphere identity across the five ‘core’ states. A common narrative of working together to defend liberal democracy against a threat from China could play a role in reproducing and reinforcing collective Anglosphere identity and security community membership. Second, we find a clear difference between attitudes to China among the majority White populations and non-White minority respondents in the Anglosphere. If the Anglosphere is indeed a security community bound together by narratives of racialized conflict (Holland Citation2020; Vucetic Citation2011a) then we might expect future tensions with China to reproduce such narratives, but public acceptance of these narratives might not be uniform. Anglosphere scholars should pay attention not only to how a narrative of China as racialized other might serve to reproduce this security community but also to the views of those who resist or reject this narrative, building on previous research into postcolonial and indigenous politics in the Anglosphere (Smits Citation2019).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/TGKQ5V

.Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Kingsley Edney

Kingsley Edney is Lecturer in Politics and International Relations of China at the University of Leeds. His research focuses on China's efforts to shape its international image. He is the author of The Globalization of Chinese Propaganda: International Power and Domestic Political Cohesion, co-editor of Soft Power with Chinese Characteristics: China's Campaign for Hearts and Minds, and has published articles on China's international relations in the Journal of Conflict Resolution, Journal of Contemporary China, and Pacific Review, among others.

Richard Turcsányi

Richard Turcsányi is an Assistant Professor at Palacký University Olomouc and Program Director at Central European Institute of Asian Studies. He is an author of Chinese Assertiveness in the South China Sea, co-editor of Contemporary China: A New Superpower? and has published numerous articles on Chinese foreign policy and relations between China and (Central and Eastern) Europe. In recent years he led a large-scale public opinion survey in 56 countries worldwide regarding their attitudes towards China and international affairs (sinofon.cz/surveys).

Notes

1 The survey data used in this article was a result of the European Regional Development Fund Project "Sinophone Borderlands – Interaction at the Edges", CZ.02.1.01/0.0/0.0/16_019/0000791. The data are available from Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/TGKQ5V.

2 Of the five countries, only the USA and UK were included in the 2014 Pew survey.

3 This was the first year that the survey asked about whether specific countries are friends or threats.

4 The causal direction between attitudes towards China and travelling to China may lead in both directions, while the causal direction between the attitudes towards China and interaction with the Chinese people is more likely to lead from the interaction with the people to the attitude towards the country.

5 The results of all 15 regressions are available in the online Annex (https://docs.google.com/document/d/1iJAQd7qoPEFz1-TV37PhW-IDyAcKhve0C4vjCOjk0wo/edit?usp=sharing). We treat general favourability towards China as the dependent variable because this is a standard indicator of China’s soft power or international image and most public opinion surveys focus on it. Since our dataset includes other variables that can be treated as alternative dependent variables – such as the willingness to align with China, more specific foreign policy preferences, and perceptions of various other aspects of, and interactions with, China – we suggest that future research conducts such studies and compares their results.

References

- Adler, Emanuel. 1997. “Imagined (Security) Communities: Cognitive Regions in International Relations.” Millennium: Journal of International Studies 26 (2): 249–277. https://doi.org/10.1177/03058298970260021101.

- Adler, Emanuel. 2008. “The Spread of Security Communities: Communities of Practice, Self-Restraint, and NATO's Post—Cold War Transformation” European Journal of International Relations 14 (2): 195–230. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066108089241.

- Adler, Emanuel, and Michael Barnett. 1998. Security Communities. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Allegretti, Aubrey. 2022. “Rishi Sunak Signals end of ‘Golden Era’ of Relations Between Britain and China.” The Guardian, November 29, 2022. https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2022/nov/28/rishi-sunak-signals-end-of-golden-era-of-relations-between-britain-and-china.

- Asia New Zealand Foundation. 2018. New Zealanders’ Perception of Asia and Asian Peoples: 2017 Annual Survey. https://www.asianz.org.nz/assets/reports/1179_POA_2018_FA_WEB.pdf.

- Asia New Zealand Foundation. 2022. New Zealanders’ Perception of Asia and Asian Peoples: 2021 Annual Survey. https://www.asianz.org.nz/assets/Uploads/Perceptions-of-Asia-2022.pdf.

- Asia New Zealand Foundation. 2023. New Zealanders’ Perception of Asia and Asian Peoples: 2022 Annual Survey. https://www.asianz.org.nz/assets/Uploads/Perceptions-of-Asia-Report-2022.pdf.

- Australian Government. 2023. National Defence: Defence Strategic Review. https://www.defence.gov.au/about/reviews-inquiries/defence-strategic-review.

- BBC. 2022. “Is China really open to improving ties with Australia?” July 21, 2022. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-australia-62217398.

- Bellamy, Alex J. 2004. Security Communities and Their Neighbours: Regional Fortresses or Global Integrators? Houndmills. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Cabinet Office. 2021. Global Britain in a Competitive Age: The Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy. March 16, 2021. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/global-britain-in-a-competitive-age-the-integrated-review-of-security-defence-development-and-foreign-policy.

- Chang, Jun Yan. 2016. “Essence of Security Communities: Explaining ASEAN.” International Relations of the Asia-Pacific 16 (3): 335–369. https://doi.org/10.1093/irap/lcv026.

- Corera, Gordon. 2023. “MI5 Head Warns of ‘Epic Scale’ of Chinese Espionage.” BBC, October 18, 2023. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-67142161.

- Deutsch, Karl, et al. 1957. Political Community and the North Atlantic Area: International Organization in the Light of Historical Experience. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Edel, Charles. 2021. “What Drove the United States to AUKUS?” The Strategist, November 3, 2021. https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/what-drove-the-united-states-to-aukus/.

- Fife, Robert, and Steven Chase. 2023. “CSIS Documents Reveal Chinese Strategy to Influence Canada’s 2021 Election.” The Globe and Mail, February 17, 2023. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/politics/article-china-influence-2021-federal-election-csis-documents/.

- Friis, Karsten, and Olav Lysne. 2021. “Huawei, 5G and Security: Technological Limitations and Political Responses.” Development and Change 52 (5): 1174–1195. https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12680.

- Ho Kilpatrick, Ryan. 2023. “The Ins and Outs of the China Daily USA.” China Media Project, March 16, 2023. https://chinamediaproject.org/2023/03/16/the-ins-and-outs-of-the-china-daily-usa/.

- Holland, Jack. 2020. Selling War and Peace: Syria and the Anglosphere. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- House Armed Services Committee. 2018. “State and Non-State Actor Influence Operations: Recommendations for U.S. National Security.” March 21, 2018. https://armedservices.house.gov/hearings/state-and-non-state-actor-influence-operations-recommendations-us-national-security.

- House of Commons Foreign Affairs Committee. 2019. “A Cautious Embrace: Defending Democracy in an Age of Autocracies.” November 5, 2019. https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201919/cmselect/cmfaff/109/109.pdf.

- Jolly, Jasper. 2018. “New Zealand Blocks Huawei Imports Over ‘Significant Security Risk’.” The Guardian, November 28, 2018. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2018/nov/28/new-zealand-blocks-huawei-5g-equipment-on-security-concerns.

- Legrand, Tim. 2015. “Transgovernmental Policy Networks in the Anglosphere.” Public Administration 93 (4): 839–855. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12207.

- Legrand, Tim. 2019. “The Past, Present and Future of Anglosphere Security Networks: Constitutive Reduction of a Shared Identity.” In The Anglosphere: Continuity, Dissonance and Location, edited by Ben Wellings, and Andrew Mycock, 56–76. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Little, Andrew. 2019. “Government to Ban Foreign Donations.” Beehive.Govt.nz, December 3, 2019. https://www.beehive.govt.nz/release/government-ban-foreign-donations.

- McCulloch, Craig. 2021. “Labour, National Tight-Lipped on Former Kiwi-Chinese MPs’ Departure.” RNZ, May 27, 2021. https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/political/443477/labour-national-tight-lipped-on-former-kiwi-chinese-mps-departure.

- MI5. 2022. “Joint Address by MI5 and FBI Heads.” July 6, 2022. https://www.mi5.gov.uk/joint-address-by-mi5-and-fbi-heads.

- Miller, Geoffrey. 2022. “Jacinda Ardern Strikes a Softer Tone on China.” The Diplomat, August 2, 2022. https://thediplomat.com/2022/08/jacinda-ardern-strikes-a-softer-tone-on-china/.

- Mycock, Andrew, and Ben Wellings. 2019. “Continuity, Dissonance and Location: An Anglosphere Research Agenda.” In The Anglosphere: Continuity, Dissonance and Location, edited by Ben Wellings, and Andrew Mycock, 1–18. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- National Security and Intelligence Committee of Parliamentarians. 2020. Annual Report 2019. https://www.nsicop-cpsnr.ca/reports/rp-2020-03-12-ar/annual_report_2019_public_en.pdf.

- New Zealand Government. 2023. Secure Together: New Zealand’s National Security Strategy 2023-2028. https://www.dpmc.govt.nz/sites/default/files/2023-11/national-security-strategy-aug2023.pdf.

- Nippert, Matt. 2019. “Police Fail to Crack Case of Burgled China Scholar Anne-Marie Brady.” New Zealand Herald, February 12, 2019. https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/police-fail-to-crack-case-of-burgled-china-scholar-anne-marie-brady/YPJVXRC3KEIR3Z6TN2RG2VTZ44/.

- Paris, Roland. 2020. “Canadian Views on China: From Ambivalence to Distrust.” Chatham House, July, 2020. https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/2020-07-21-canada-china-views-paris.pdf.

- Pew Research Center. 2023. “Topline Questionnaire, Pew Research Center, Spring 2023 Global Attitudes Survey.” https://www.pewresearch.org/global/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2023/10/PG_2023.11.06_U.S.-China_Topline.pdf.

- Pew Research Center. n.d. “Opinion of China.” Global Indicators Database. Accessed July 10, 2023. https://www.pewresearch.org/global/database/indicator/24/.

- Ravenhill, John, and Geoff Heubner. 2019. “The Political Economy of the Anglosphere: Geography Trumps History.” In The Anglosphere: Continuity, Dissonance and Location, edited by Ben Wellings, and Andrew Mycock, 95–119. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Risse, Thomas. 2016. “The Transatlantic Security Community: Erosion from Within?” In The West and the Global Power Shift: Transatlantic Relations and Global Governance, edited by Riccardo Alcaro, John Peterson, and Ettore Greco, 21–42. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Roy, Eleanor Ainge. 2018. “New Zealand’s Five Eyes Membership Called Into Question Over ‘China Links’.” The Guardian, May 28, 2018. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/may/28/new-zealands-five-eyes-membership-called-into-question-over-china-links.

- The Select Committee on the CCP. 2023. “Chairman Gallagher’s Opening Remarks.” February 28, 2023. https://selectcommitteeontheccp.house.gov/media/press-releases/chairman-gallaghers-opening-remarks.

- Smits, Katherine. 2019. “The Anglosphere and Indigenous Politics.” In The Anglosphere: Continuity, Dissonance and Location, edited by Ben Wellings, and Andrew Mycock, 156–172. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Thomas, Rachel. 2020. “Andrew Little Says New Zealand Won’t Follow UK’s Huawei 5G Ban.” Radio New Zealand, July 15, 2020. https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/political/421286/andrew-little-says-new-zealand-won-t-follow-uk-s-huawei-5g-ban.

- Tusicisny, Andrej. 2007. “Security Communities and Their Values: Taking Masses Seriously.” International Political Science Review 28 (4): 425–449. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512107079639.

- U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission. 2023. China’s Global Influence and Interference Activities. March 23, 2023. https://www.uscc.gov/hearings/chinas-global-influence-and-interference-activities.

- US Congress. 2023. H.Res.11 - Establishing the Select Committee on the Strategic Competition Between the United States and the Chinese Communist Party. January 10, 2023. https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-resolution/11.

- Vucetic, Srdjan. 2011a. The Anglosphere: A Genealogy of a Racialized Identity in International Relations. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Vucetic, Srdjan. 2011b. “Bound to Follow? The Anglosphere and US-led Coalitions of the Willing, 1950-2001.” European Journal of International Relations 17 (1): 27–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066109350052.

- Vucetic, Srdjan. 2019. “The Anglosphere Beyond Security.” In The Anglosphere: Continuity, Dissonance and Location, edited by Ben Wellings, and Andrew Mycock, 77–91. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Walters, Laura. 2018. “PM Responds to Report That Labels NZ as ‘Soft Underbelly’ for China Infiltration.” Stuff, May 30, 2018. https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/politics/104330488/nz-soft-underbelly-for-china-infiltration-of-intelligence-network–canadian-report.

- Wellings, Ben. 2019. English Nationalism, Brexit and the Anglosphere: Wider Still and Wider. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Wellings, Ben, and Andrew Mycock. 2019. The Anglosphere: Continuity, Dissonance and Location. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- The White House. 2022. National Security Strategy. October 2022. https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Biden-Harris-Administrations-National-Security-Strategy-10.2022.pdf.