ABSTRACT

#MeToo has raised public awareness on issues of sexual harassment and misconduct at an unprecedented scale, nurturing hopes for sustainable change also in terms of gender equality. We use the concept of politicization to assess the potential for change which #MeToo might have induced in the broader print media discourse on gender equality issues. We analyse Australia as an arguably difficult case due to its conservative political and media system, thus offering political activism rather dire prospects of public resonance. We assess a total of two years of media coverage in the eight largest newspapers (October 2016 – September 2018), combining automated content analysis with manual claims analysis. Our results speak to the societal debate on gender equality as well as the potential of online social movements to change mainstream discourses and social realities.

The #MeToo momentum

The MeToo movement was first initiated by Tarana Burke in 2006 to signal to black women and girls that they were not alone with their experiences of sexual harassment and abuse (Gibson et al. Citation2019). The movement gained momentum in October 2017 when Harvey Weinstein, a well-established Hollywood producer, became the centre of a large-scale sexual harassment scandal. The hashtag #MeToo, created by actress Alyssa Milano, encouraged people to share their stories to demonstrate the structural dimensions and magnitude of the problem. It was used 12 Million times around the globe within the following 24 h (see Fileborn, Loney-Howes, and Hindes Citation2019) and quickly spilled over from social media, generating attention in the mainstream media. While building on other, similar movements (Loney-Howes et al. Citation2021), #MeToo provided an ungated, direct communication channel for women, revealing an unimagined scope of structural sexual harassment, misconduct, and violence (Mendes, Keller, and Ringrose Citation2019). Sexual harassment and violence should be understood as symptoms of a deeper cause, namely the imbalance of power between and inequality of men and women, expressed also in, for example, unequal pay and career chances or gender discrimination (Gill and Orgad Citation2018). In this respect, the ‘explosion’ of #MeToo and its global spread nurtured hopes for the empowerment of women (Loney-Howes et al. Citation2021). However, the question remains if #MeToo has really brought about a sustained change regarding gender equality, thus the equal and fair distribution of opportunities, resources, rights, and responsibilities between women and men (Hammarström et al. Citation2014).

Arguably, the mobilizing potential of political activism is strongly influenced by the discursive environment in which it operates (Koopmans et al. Citation2005). Certain topics may not be publicly discussed at all or not very prominently, and while political activism might be more urgently needed in such cases, it might be difficult to spark if the chances of public resonance look dire. Australia seems like such a case regarding gender equality. According to the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Index, gender equality is declining as the country has fallen from rank 15 to 44 in the last 14 years (Coggan Citation2020). In another recent survey, the share of women stating that gender equality is important to them was 17% higher than the share of men, the second-highest discrepancy in the world (Davey Citation2021). Women are still significantly underrepresented in the Australian parliament (Collier and Raney Citation2018) and domestic violence is a recurrent issue (Davey Citation2021). Also, the term of Australia’s only female Prime Minister Julia Gillard (2010–2013) was accompanied by a sexist backlash. Overall, the political climate for women in Australia is described as difficult, even ‘toxic’ (Mao Citation2019).

Hence, Australia is a country where gender equality still remains a large societal issue and, therefore, presents an interesting case to analyse the influence of #MeToo on the public discourse about gender equality. Research thus far has rather focused on other regions like the US (O’Boyle and Li Citation2019; Zarkov and Davis Citation2018), and Europe (Askanius and Hartley Citation2019; De Benedictis, Orgad, and Rottenberg Citation2019) while studies of the Australian case tend to remain limited to the specific topic of sexual harassment (e.g. Hindes and Fileborn Citation2019; Loney-Howes and Fileborn Citation2020). We aim to contribute to the discussion by analyzing Australian mainstream print news. Our study is guided by the following research question: (in how far) has the #MeToo movement led to a politicization of the broader topic of gender equality in Australian print media discourse? Theoretically, our research draws on the concept of politicization to understand the potential for political change that #MeToo might have induced. We analyse two years of print media coverage on gender equality in the eight largest Australian newspapers (October 2016–September 2018) and base our study on manually coded political claims (Koopmans and Statham Citation1999) as well as automated text analysis (Boumans and Trilling Citation2016). Doing so allows studying broader trends but also more fine-grained nuances of the news media debate on gender equality before and after the (potentially) politicizing momentum of #MeToo in October 2017.

Public discourse about gender equality

The public sphere is the societal forum for debate and contestation where common discussions, negotiations, evaluations, and definitions of social and political standards for society occur (Habermas Citation1962). As such, the public sphere is ‘capable of influencing the use of public power and of holding public officials accountable’ (Fraser Citation2009, 155). Discourse taking place in the public sphere mirrors the dynamic social and discursive construction of constantly changing knowledge, identity, and social relations, thus changing as well as reproducing social realities (Jørgensen and Phillips Citation2002, 9). Looking into public discourse, therefore, tells us about currently salient topics and the political and societal actors discussing them. It also reveals the normative foundations of a society in terms of which values are upheld and cherished, including why and how they change. For tracing such changes in the debate, we rely on the concept of politicization defined as ‘an increase in polarization of opinions, interests or values and the extent to which opinions are publicly advanced ‘ (De Wilde Citation2011, 566/567). As such, politicization means to render something political by making an issue a subject of political discussion and contestation (Hay Citation2013). Politicization can highlight possible existent societal inequalities and create a sense of urgency and pressure on responsible political decision-makers, thereby opening up a window of opportunity for structural change (De Wilde Citation2011). Thus, the politicization of gender equality could change the incentives for its advocates to push their agenda in an altered discursive context which has become more open and responsive to their arguments (Koopmans et al. Citation2005). Politicization is understood as a multi-dimensional phenomenon, developing in terms of (1) an intensification of debates (salience) in terms of news media visibility, (2) an increase of the range of actors getting involved in the debate (actor expansion), and (3) the polarization of opinions in terms of their range and distance (De Wilde Citation2011). Therefore, a change in these three dimensions regarding how an issue is discussed in public discourse could spark political mobilization and thereby lead to institutional change (Koopmans et al. Citation2005).

A public debate as such is enabled by the mass media as a central, institutionalized interface for public discourse reaching a broad audience. As such, ‘[m]edia … are central to what ultimately come to represent our social realities’ (Brooks and Hébert Citation2006, 297): Yet, in addition to conveying information, the media must also be seen as an active agent of news. News media do not only transfer the communication of others; they are subject to economic constraints and, therefore, carefully select the news to be published. Doing so, they follow a logic of news values (O’Neill and Harcup Citation2009). News values can influence how information is presented and highlight what makes something ‘newsworthy’ (Galtung and Ruge Citation1965). For example, news stories concerning powerful individuals, organisations or institutions are likely to gather news attention. Similarly, stories concerning celebrities or entertainment stories about show business or unfolding drama are likely to create news traction. Moreover, good (stories about positive outcomes) or bad news (stories focused on conflict or tragedy as well as sensationalism, crime, and violence) have a higher news value (O’Neill and Harcup Citation2009). Somewhat related, news media highlight some aspects of an issue in their reporting more than others, suggesting a certain kind of interpretation (Entman Citation1993; Goffman Citation1974). Doing so, they may place an issue into a larger context, highlighting how it is connected to the bigger picture, focusing on trends over time and highlighting different contexts and environments (thematic framing). News media may, however, also treat issues as single episodes or discrete events (episodic framing), without connecting them to a broader theme (Iyengar Citation1991). The latter may be problematic as the media may miss the chance to convey a full understanding of how events and cases connect or how these episodes may be symptoms of deeper structural causes.

Empirical research on the topic of gender equality has generally highlighted the importance of structural conditions in how debates about violence against women evolve. In war contexts, for example, gender-based violence may be deemed less significant in comparison to news about peace agreements. However, rape myths and distrust towards women persist also in stable criminal justice systems, where stereotypes of women as deceitful are being reproduced in an every-day climate of male hegemony (see Phipps et al. Citation2018, 2/3). These stereotypes are also replicated in the news media. Indeed, prior research on sexual harassment in the media (Zarkov and Davis Citation2018) finds that coverage fosters and reinforces stereotypes about rape, rapists, and rape victims (Hindes and Fileborn Citation2019). Sexual predators are often referred to as ‘monsters’ and victims as either ‘virgins’ or ‘promiscuous women’ who asked to be abused (Mason and Monckton-Smith Citation2008; O’Hara Citation2012). Based on these findings, media are found to contribute to a rape-enabling culture (Loney-Howes and Fileborn Citation2020), emphasising newsworthy stories about crime and violence. Furthermore, there seems to be a gender bias in terms of women’s under- or misrepresentation in the news (Collins Citation2011) and a topical bias towards linking women actors with what is called soft-topics (Ross and Carter Citation2011).

The same is true for studies of #MeToo coverage in particular. For the UK context, De Benedictis, Orgad, and Rottenberg (Citation2019) conclude that coverage of #MeToo is largely a reproduction of known patterns which focuses on individual cases of celebrities (Franssen Citation2020), thus following the earlier discussed logic of news values. Debates about gender-based violence are also overwhelmingly focused on white women’s experiences neglecting black women or intersectional dynamics in general, such as the role of class (Phipps et al. Citation2018). Analysing Danish and Swedish media coverage, Askanius and Hartley (Citation2019) support these findings and state that sexual assault is portrayed as a personal and individual, rather than a structural problem, highlighting how episodic, rather than thematic framing prevails in coverage on the topic. For the Australian case, Hindes and Fileborn (Citation2019) analyse news coverage of grey area sexual violence in the #MeToo era. They find a reproduction of known patterns of putting the onus on women who did not protect themselves enough, portraying men as aggressively driven by sexual instincts. Meanwhile, Loney-Howes and Fileborn (Citation2020) look into #MeToo coverage in regional and rural media in Australia and find that discourse reinforces a focus on heterosexual, white women.

While these studies provide valuable insights into how #MeToo is covered in the media, they do not assess its connection to the broader issue of gender equality. Going beyond the state of the art, we provide a systematic, large-scale assessment of #MeToo’s influence on how gender equality is portrayed in mainstream news outlets. Additionally, studies do not assess politicization holistically. Prior studies on #MeToo coverage in other contexts find sustained salience for sexual violence, assault, and harassment, but also women’s rights, gender equality, reproductive rights, and the gender pay gap (De Benedictis, Orgad, and Rottenberg Citation2019; Ennis and Wolfe Citation2018). Studies analysing social media contents regarding the impact of the similar movement SlutWalk (Zhang and Kramarae Citation2014) show more attention to issues of gender, sex, and gender equity. The study by Boyle and Rathnayake (Citation2020; also Dejmanee et al. Citation2020) illustrates polarized dynamics in the #MeToo discourse in the US context, yet again for social media only. While results for social media cannot directly inform our hypotheses, they nonetheless may mirror trends developing in the mainstream media, too. We, therefore, tentatively expect that #MeToo has induced a politicization of the broader debate on gender equality in Australian print news. Thus, (a) greater visibility of the broader theme of gender equality; (b) a greater range of actors becoming involved; and (c) a greater polarization of positions is expected. In turn, it is expected that this politicization may help to raise awareness about discrimination against women and gender equality. By doing this, politicization can have a positive effect on how gender is further being discussed and debated in the Australian political landscape.

Combining claims-making and automated content analysis

Starting from the very general assumption that gender equality is a policy issue advanced and supported more in a left-leaning climate, the Australian environment can be regarded as unfavourable (Harris Rimmer and Sawer Citation2016) in at least three dimensions possibly relevant to gender equality discourses. First, in terms of legal aspects, defamation laws in Australia, unlike other Western countries such as the US, put the onus on the person making the allegations rather than on the accused (Harris Rimmer and Sawer Citation2016). This makes it harder for affected persons to speak up. Second, in terms of the political system, the Liberal Party of Australia, traditionally promoting a conservative economic-liberal stance, has been in government since 1996, interrupted only between 2007–2013 by the Australian Labor Party (Gauja Citation2015). Third, the media system in Australia is generally described as liberal, resembling the UK and the U.S., but also shows strong traits of clientelism, mirrored, for instance, in the well-known and tolerated political loyalty of the public media and informal connections between private media owners and political actors (Jones and Pusey Citation2010, 456). In particular, Australian newspapers are heavily dominated by the News Limited Corporation () belonging to the Murdoch-founded News Corp. These newspapers are generally described as centre-right to rightist in terms of their political leaning (Jones and Pusey Citation2008; see FN 1). Overall, assessing if #MeToo sparked a politicization of the broader issue of gender equality in Australia can help to understand how conservative systems hinder or support political activism for gender equality.

Table 1. Analysed news outlets.

Our period of analysis covers October 2016-September 2018. It is based on a quantitative content analysis, yet claims analysis has been described as a hybrid with qualitative and quantitative elements (Kluknavská, Bernhard, and Boomgaarden Citation2021). In that sense, we aim to study broader trends and patterns in print news coverage based on automated content analysis, but delve much deeper into the debate by analysing claims raised in news articles on gender equality. We analysed the eight largest daily newspapers in Australia (), including all sections except for TV guides and book reviews. For our search terms, we drew on similar theoretical and empirical research, and terms associated with sexual harassment and misconduct (see Supplementary Material A for full search string). A total of n = 6567 articles were included in the analysis.

For the automated analysis, we used R to analyse whole articles along the three dimensions of politicization: salience, expansion, and polarization; we used regular expressions as well as the stringr package for data cleaning and the extraction of Metadata (e.g. date and section).

The salience of gender equality in Australian news coverage was measured using topic modelling as an inductive text-mining approach (Boumans and Trilling Citation2016) with the stm package (Roberts, Stewart, and Tingley Citation2018). A topic model identifies ‘what is being talked about’ by clustering words that frequently co-occur in the whole text corpus and documents individually. The output of a topic model is a collection of words for each ‘topic’ ranked in terms of their frequency (label terms) which then needs to be interpreted and labeled by the researcher (Günther and Domahidi Citation2017; see Supplementary Material C1). For the analysis, the text corpus was preprocessed, i.e. we deleted stop-words like ‘the’, ‘a’, ‘is’, ‘are’, rarely occurring terms (frequency < 50), and numbers from the text to increase the readability of the output. Moreover, these preprocessing steps also helped to increase term exclusivity as well as semantic coherence, thus contributing to the distinctiveness of topics (see Supplementary Material C2). As argued above, the topic of gender equality is a cross-sectional issue touching upon very different policy areas, also mirrored in the rather broad definition of our search string. A topic model allows for a more fine-grained analysis of the salience of different gender equality sub-issues. The final number of topics identified by the model needs to be assessed in an iterative process in which different amounts of topics are tested. We decided on a 12-topic model which was the clearest interpretable solution. Each article was then assigned to the topic with the highest expected proportion in the text (; see Supplementary Material C). Not all of the twelve identified topics were equally relevant for our analysis as news articles often cover several, in some way connected topics. Therefore, we decided to only include the six directly relevant ones (see Supplementary Material C3).

For measuring expansion in terms of the range of actors appearing in the discourse, we automatically extracted persons and organizations from articles using the SpacyR package in R. To get a clearer picture, we ranked the extracted list of entities according to the number of mentions and, in a second step, searched for them in the text to compute a variable indicating how many of those 50 actors were mentioned in an article.

For measuring polarization, we used the quanteda package in R (Benoit, Watanabe, and Wang Citation2020) and applied the extensively validated Lexicoder sentiment dictionary (Young and Soroka Citation2012) for calculating average sentiment scores per article (number of positive words – number of negative words/total number of words in article). Based on this, we calculated the standard deviation of sentiment in articles per month to represent the degree of polarization as the average difference from the mean.

Turning to manual coding, claims-making analysis is a method specifically tailored to the measurement of contestation, originally developed to analyse claims raised by social movements. Claims-making refers to the process of ‘articulating claims that bear on someone else's interests’ (Lindekilde Citation2013, 1), focusing on the purposive and public expression of views, criticism, political demands, calls to action, proposals, or physical attacks (Statham et al. Citation2005). It looks at the relations between the actors making strategic interventions (claims) on specific issues, conveying certain evaluations, and addressing other actors (Koopmans and Statham Citation1999). We define a ‘claim’ as an expression of a political opinion by physical or verbal action (reported) in the public sphere regarding gender equality. For our purposes, claims must deal with gender equality in the broad sense defined earlier.

We identified claims as our unit of analysis directly in the text from a stratified sample of articles. These covered the whole period of analysis to keep the workload of manual coding manageable: in a pre-test, an average number of around 2.5 claims per article were found. We, therefore, defined a number of 50 articles per newspaper (400 articles in total) for obtaining a sample of over 1000 claims. All claims from these 400 articles were included ().

Based on Koopmans and Statham (Citation1999), we identified the claim in the article based on the object of the claim: as objects, thus actors about whom the claims were made, we counted terms referring directly to a person’s sex or gender (woman/man/boy/girl, diverse, transgender), actors described with gender/sex adjectives (female/male/feminine/masculine) and terms that implied a certain stance towards gender equality (for example feminist, misogynist). We coded the explicit information given in the article and in some cases, could not distinguish the sex or gender of actors quoted or mentioned. Our use of the terminology reflects how the terms were used in news coverage.

Each claim must include a claimant (the active voice, thus the actor raising the claim), in our case a political or societal actor (e.g. government, social movement, expert, journalist if writing editorial piece) who makes a statement relating to the identified object actor. Furthermore, we coded the evaluation conveyed towards the object (positive/ slightly positive/ ambivalent or neutral/ slightly negative/ negative); the broader issue context (e.g. domestic violence, equal pay, sexual harassment) and the justifications or frames, if specified ().

Table 2. Examples of coded claims

The justifications/frames of claims were identified inductively in an extensive pre-test and the list of frames extended during the coding (see Supplementary Material B2 for further information). Claims tend to be incomplete; in those instances when a claimant did not explicitly justify their argument, we coded ‘no frame’. Claim identification and all variables coded for the claim analysis were checked for reliability and yielded satisfactory scores (see Supplementary Material B1).

Regarding the three dimensions of politicization, we looked into the variable issue for salience, assessing the overall visibility of the different aspects of the debate. The variables object and claimant were analysed for expansion, looking at who was talked about and who was given a voice to speak. The variables of position and frame served to measure and contextualise the polarization of positions.

Salience, polarisation and actor expansion in the #MeToo discourse

In this section, we first present our results for the automated analysis and then move on to delve deeper into the contestation of gender equality based on manual text analyses regarding the three aspects of politicization as discussed earlier: salience, expansion, and polarization.

The bigger picture

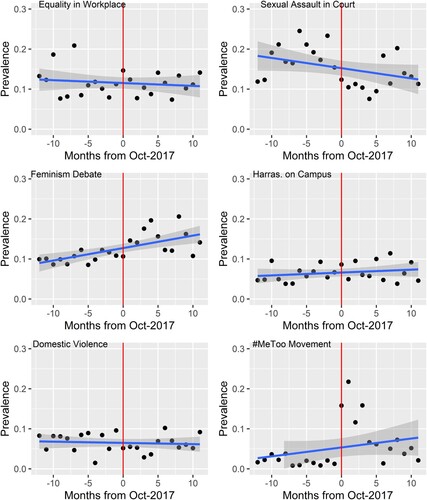

To begin with, salience assesses the dynamics in news visibility of the broader issue of gender equality and its subtopics. The subtopics identified with our topic model dealt with equality in the workplace and equal career chances, sexual assault and harassment, and feminism (). Discussions about equality in the workplace, sexual assault legal cases as well as domestic violence seem to (slightly) decrease regarding prevalence while the visibility of feminism and sexual harassment in universities increased. The actual discussion on sexual harassment in Hollywood’s entertainment industry, which we labelled #MeToo, is weak before October 2017; visibility is explained by coverage of, for example, the rape accusations against movie director Roman Polanski. Due to its similarity to the #MeToo discussion, such coverage was still clustered into that specific topic by the topic model.

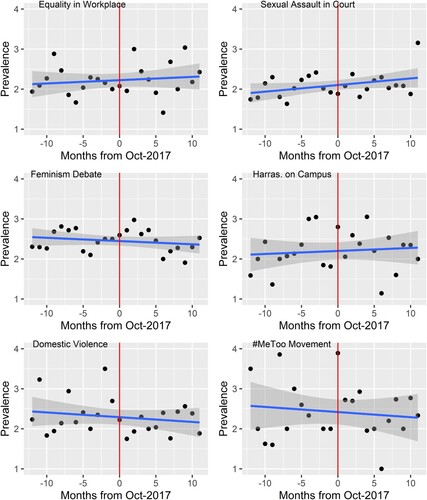

Expansion refers to the dynamics in the range of actors that became involved in the broader discussion about gender equality. Here, the actors mentioned most in news articles were politicians from the U.S. – Donald Trump and Hilary Clinton, followed by domestic politicians like Malcolm Turnbull, Tony Abbott, or domestic political parties. In addition, individuals or companies involved in sexual abuse scandals (for example Cardinal Pell) were visible on the print news agenda. When considering only the 50 most prominent actors on average and over time, we see an increase in actor mentions in the equality in the workplace discussion as well as articles on sexual assault in court and on campus. In the feminism debate, as well as the debate on domestic violence and #MeToo, we see a slight decrease in the range of actors involved (; see Supplementary Material D for all topics).

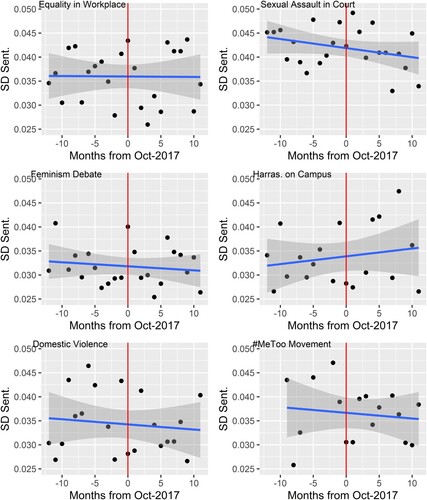

Polarization, operationalized as the standard deviation in the position of claimants, measures how extreme the range of positions (; see Supplementary Material E for all topics). Especially in news articles covering sexual assault and how it was dealt with in court, polarization was higher in comparison to all other relevant topics but decreased over the two years. Discussions on equality in the workplace, feminism, domestic violence, and the #MeToo debate decreased or stagnated in polarization as well; the only topic with an increasing trend is the discussion about sexual harassment on campus. Yet, given the very low numbers overall, changes in the polarization of opinions on gender equality are not particularly pronounced for our period of analysis.

Nuances in the contestation of gender equality

In the following, we discuss the results of our claims analysis to take a closer look at the unfolding debate. Regarding the overall salience, the average of claims per article mostly ranged between 2 and 3 across newspapers (). We found more claims after #MeToo, indicating that contestation became stronger (: Total). In terms of subtopics, the debate was dominated by four broad issues: violence and sexual harassment against women, equality and inequality in the workplace, gender stereotypes and cultural norms, and the role of gender movements and feminism.

Table 3. Issues of gender equality with associated objects before and after #MeToo.

As also shown in the automated analysis, the discussions on feminism and gender movements increased after #MeToo, with especially sexual harassment becoming a more discussed topic. At the same time, claims on gender inequality decreased, suggesting a possible turn to a more positive framing of gender issues. Men were prevalently associated with gender-based violence and sexual harassment topics as both as those who make claims and who are objects of these claims, especially after #MeToo. In contrast, opinions concerning gender diversity and inequality issues were raised about women as claim objects, rather than by women themselves, increasingly after #MeToo ().

Regarding the expansion of actors involved in the debate, the voice of women was stronger than the voice of men; women were also given more space after #MeToo (). #MeToo not only increased the visibility of claimants from the entertainment industry in general, but also the active voice of female celebrities and influential public figures, surpassing their male colleagues in the industry. Similarly, the voice of female journalists was much stronger in comparison to their male counterparts, even increasing after #MeToo. Women were more often talked about (female object actors: 62.5%) in comparison to men (37.5%), but decreasingly so after #MeToo (69.3% to 57.4%). This suggests a shift from a more passive depiction to a more active role of women in the discourse. Men were, however, more visible than women in the category of political actors (generally the most prominent claimant group), even more so after #MeToo. In the entrepreneur category, women dominated partly because they were often given space to talk as successful role models in business ().

Table 4. Categories of Claimants.

Polarization towards different genders was measured as the standard deviation of claimants’ positions towards objects. Claims about female object actors showed higher polarization (SD = 1.180) than their male counterparts (SD = 0.996). Yet, greater polarization in opinions on gender equality was observed amongst women than men as the SD amongst female claimants increased after #MeToo (from 1.102to 1.224), while it decreased for male claimants (from 1.142 to 1.109).

Further deepening the analysis of polarization, we looked into the justifications used to support positions. Overall, we identified four broad frames (): unfriendly polity and policy structures, sexism and stereotypes, empowerment for gender equality, and male gender discrimination. Unchanged by #MeToo, women needed to justify themselves much more often than men. Similarly, when (female or male) claimants spoke about women, they more often used a justification to support their claim than when talking about men (). Women and men used different justifications: women were more often connected to the need to empower themselves, both in a sense of actively claiming their empowerment for gender equality and being an object of such framing (). The sexism and stereotypes frame was generally related to women, both as active claimants and passive objects of claims (). The debate was also framed in terms of the supposed male gender discrimination, surprisingly emphasized by both female (6.5%) and male (8.8%) claimants, and even more after #MeToo (both genders around 9%). It was still men, who were increasingly (6.7% to 11.2%) connected as objects of discrimination after #MeToo. Thus, it seems that this debate, while strongly focussed on women, also led to a stronger discussion of discrimination against men (see also , example no. 3).

Table 5. Frames with associated objects before and after #MeToo.

The politicizing spark?

The aim of our study was to understand #MeToo’s potential politicizing effect on the broader debate about gender equality in Australia by analysing print news regarding salience, expansion, and polarization. Our results for the automated content analysis show increasing trends for topics directly linked to the #MeToo debate, i.e, sexual harassment, and feminism, mostly in terms of salience but not for actor expansion or polarization. Therefore, our tentative expectations find weak support looking at the bigger picture only. These general trends are qualified in the manual coding which shows important nuances in how #MeToo has affected the discussion about gender equality for men and women differently.

Many of our results resonate directly with the literature: the salience of topics related to sexual harassment, misconduct, and violence increased after #MeToo (De Benedictis, Orgad, and Rottenberg Citation2019; Ennis and Wolfe Citation2018) while other topics related to gender equality were affected to a much lesser degree. Regarding expansion, #MeToo coverage focused on already famous people (O’Neill and Harcup Citation2009); also in Australia, the stories surfacing with #MeToo were framed as episodes rather than connecting them with a greater theme to highlight structural problems (Askanius and Hartley Citation2019; De Benedictis, Orgad, and Rottenberg Citation2019; more generally also Iyengar Citation1991). Overall, men are found even more dominant in the debate after #MeToo, as the category of political actors, mostly men, is most prominent (e.g. Collins Citation2011). #MeToo has increased the space for women in the print news discourse, actively claiming a stronger say in the debate, but men are still seen as the ones exerting political power (Musto, Cooky, and Messner Citation2017). Especially in a media context shaped by clientelism, this seems an immediate mirror of a political culture of male hegemony (Jones and Pusey Citation2010).

In terms of a polarization of positions, our findings indicate a weak influence of #MeToo, but some aspects are particularly noteworthy. Women’s claims were more often grounded in an explicitly formulated justification. This dynamic of the news discourse can be due to women justifying themselves more or journalists feeling a greater need to cover such claims with a justification. This result may be understood as a mirror of the logic of defamation laws in Australia in that the onus is put on women justifying their ‘accusations’ (Hindes and Fileborn Citation2019) or their involvement in the discourse more generally. Moreover, the discrimination of men was increasingly used as a frame in claims after #MeToo. Looking into examples (see , example 3), this seems to be a backlash in terms of ‘whataboutism’, thus countering an accusation with a counter-accusation, which has been observed intensely in the U.S. context (Boyle and Rathnayake Citation2020; Dejmanee et al. Citation2020). In that sense, journalists might have felt the need to ‘balance’ news on gender equality, while also serving the news value of sensationalism. Given the structural deprivation of women made visible with #MeToo, this sort of relativization, however, rather serves to reinforce a culture of male hegemony and ignorance to protect male privilege (O’Neill Citation2021).

Overall, the politicizing spark of #MeToo on the Australian print media discourse is weak. Most influence is observed for directly related topics such as sexual harassment and violence, from which we conclude that the overall media logic of news values was not disrupted by #MeToo (e.g. O’Neill and Harcup Citation2009). As Yin and Sun (Citation2020, 1) argue for the Chinese case, ‘MeToo manifests both the potential to change gender hierarchies in the digital age and the limitation that structural inequalities cannot be changed by technologies per se’. In that respect, it seems that underlying asymmetric power relations between men and women have been somewhat politicized only in an explicitly physical, sensationalist sense. Resonating with similar studies (see Phipps et al. Citation2018), the male-dominated, conservative Australian context seems to slow down efforts to spark a politicization of gender equality. Thus, with gender equality declining and the political climate described as toxic, it seems that political activism to advance the equal treatment of men and women still has a long way to go. Our analysis shows first steps of women speaking up and being granted a say in the mainstream (print) media discourse, highlighting the important societal function of social media activism. Yet, in Australia, changing these particular social realities seems a more difficult task than in other countries.

Our study is limited in that we have analysed two years and only one case, but combining two approaches to content analysis shedding light on different aspects of the print media discourse. Future research should consider longer periods and directly compare cases and media channels. It should also broaden its scope and consider discourses of race and diversity in connection to the advancement of equality in the #MeToo context. This can help to better assess how #MeToo might help to sustainably change not only gender balances but also if and how it may induce sustainable policy change for the implementation of equal and fair treatment of people in all aspects of life.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Verena K. Brändle for helpful criticism on earlier drafts of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Olga Eisele

Olga Eisele is a post-doctoral researcher at the University of Vienna. Her research focuses on political communication with a focus on the relationship between media and politics, the European Union in crisis, as well as automated content analysis. She obtained her PhD from the University of Vienna in 2017.

Elena Escalante-Block

Elena Escalante-Block is a postdoctoral researcher at Antwerpen University and, at the time when this research was conducted, was a PhD candidate at Sciences Po Paris and Marie Sklodowska-Curie fellow in the Innovative Training Network PLATO. Her dissertation investigated how state aid cases can serve as ‘trigger moments’ in the politicisation/depoliticisation and legitimation/delegitimation of the European Union.

Alena Kluknavská

Alena Kluknavská is a post-doctoral researcher at Masaryk University in Brno. She focuses on the populist radical right parties in Central and Eastern Europe, communication of political actors and social movements. She obtained her PhD in August 2015 from Comenius University in Bratislava.

Hajo G. Boomgaarden

Hajo G. Boomgaarden is Professor for Empirical Social Science Methods with a Focus on Text Analysis at Vienna University. His research interests include (advances in) content analysis, media portrayals of politics and media effects on political attitudes and behaviors. He obtained his PhD from the University of Amsterdam in 2007.

Notes

1 See http://www.roymorgan.com/findings/5136-political-profiles-of-newspapers-readerships-june-2013-201308272330. Last accessed 13 June 2019.

References

- Askanius, Tina, and Jannie Moller Hartley. 2019. “Framing Gender Justice.” NORDICOM Review 40 (2): 19–36.

- Benoit, Ken, Kohei Watanabe, Haiyan Wang, … Paul Nulty - Journal of Open, and Undefined 2018. 2020. “Quanteda: An R Package for the Quantitative Analysis of Textual Data.” Joss.Theoj.Org.

- Boumans, Jelle W, and Damian Trilling. 2016. “Taking Stock of the Toolkit.” Digital Journalism 4 (1): 8–23.

- Boyle, Karen, and Chamil Rathnayake. 2020. “#HimToo and the Networking of Misogyny in the Age of #MeToo.” Feminist Media Studies 20 (8): 1259–1277.

- Brooks, Dwight E., and Lisa P. Hébert. 2006. “Gender, Race, and Media Representation.” In The SAGE Handbook of Gender and Communication, edited by Bonnie J. Dow and Julia T. Wood, 297–318. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Coggan, Maggie. 2020. “Gender Equality in Australia is on the Decline. Here’s What Could Fix It.” PRObono Australia News. https://probonoaustralia.com.au/news/2020/03/gender-equality-in-australia-is-on-the-decline-heres-what-could-fix-it/.

- Collier, Cheryl N., and Tracey Raney. 2018. “Understanding Sexism and Sexual Harassment in Politics: A Comparison of Westminster Parliaments in Australia, the United Kingdom, and Canada.” Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society 25 (3): 432–455. doi:10.1093/SP/JXY024.

- Collins, Rebecca L. 2011. “Content Analysis of Gender Roles in Media: Where Are We Now and Where Should We Go?” Sex Roles 64 (3–4): 290–298.

- Davey, Melissa. 2021. “‘Gender Ignorant’ Treasurers Leave Australia Lagging Behind in Women’s Equality, Equity Advocate Says.” The Guardian, January 28. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/jan/29/gender-ignorant-treasurers-leave-australia-lagging-behind-in-womens-equality-equity-advocate-says.

- De Benedictis, Sara, Shani Orgad, and Catherine Rottenberg. 2019. “#MeToo, Popular Feminism and the News: A Content Analysis of UK Newspaper Coverage.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 22 (5–6): 718–738.

- Dejmanee, Tisha, Zulfia Zaher, Samantha Rouech, and Michael J. Papa. 2020. “#MeToo; #HimToo: Popular Feminism and Hashtag Activism in the Kavanaugh Hearings.” International Journal of Communication 14: 3946–3963.

- De Wilde, Pieter. 2011. “No Polity for Old Politics? A Framework for Analyzing the Politicization of European Integration.” Journal of European Integration 33 (5): 559–575.

- Ennis, Eliza, and Lauren Wolfe. 2018. #MeToo: The Women’s Media Center Report. http://www.womensmediacenter.com/reports/media-and-metoo-how-a-movement-affected-press-cover age-of-sexual-assault.

- Entman, Robert M. 1993. “Framing: Toward Clarification of a Fractured Paradigm.” Journal of Communication 43 (4): 51–58.

- Fileborn, B., R. E. Loney-Howes, and S. Hindes. 2019. “#MeToo Has Changed the Media Landscape, but in Australia There Is Still Much to Be Done.” The Conversation 8: 1–6.

- Franssen, Gaston. 2020. “Celebrity in the #MeToo Era.” Celebrity Studies 11 (2): 257–259.

- Fraser, Nancy. 2009. Scales of Justice: Reimagining Political Space in a Globalizing World. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Galtung, Johan, and Marie Holmboe Ruge. 1965. “The Structure of Foreign News.” Journal of Peace Research 2 (1): 64–90.

- Gauja, Anika. 2015. “The State of Democracy and Representation in Australia.” Representation 51 (1): 23–34.

- Gibson, Camille, Shannon Davenport, Tina Fowler, Colette B. Harris, Melanie Prudhomme, Serita Whiting, and Sherri Simmons-Horton. 2019. “Understanding the 2017 “Me Too” Movement’s Timing.” Humanity & Society 43 (2): 217–224.

- Gill, Rosalind, and Shani Orgad. 2018. “The Shifting Terrain of Sex and Power: From the ‘Sexualization of Culture’ to #MeToo.” Sexualities 21 (8): 1313–1324.

- Goffman, Erving. 1974. Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of Experience. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Günther, Elisabeth, and Emese Domahidi. 2017. “What Communication Scholars Write About: An Analysis of 80 Years of Research in High-Impact Journals.” International Journal of Communication 11: 3051–3071.

- Habermas, Jürgen. 1962. Strukturwandel Der Öffentlichkeit. Untersuchungen Zu Einer Kategorie Der Bürgerlichen Gesellschaft. Frankfurt: Suhrkamp.

- Hammarström, Anne, Klara Johansson, Ellen Annandale, Christina Ahlgren, Lena Aléx, Monica Christianson, Sofia Elwér, et al. 2014. “Central Gender Theoretical Concepts in Health Research: The State of the Art.” Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 68 (2): 185–190.

- Harris Rimmer, Susan, and Marian Sawer. 2016. “Neoliberalism and Gender Equality Policy in Australia.” Australian Journal of Political Science 51 (4): 742–758.

- Hay, Colin. 2013. “From Politics to Politicisation: Defending the Indefensible?” Politics, Groups and Identities 1 (1): 109–112.

- Hindes, Sophie, and Bianca Fileborn. 2019. “‘Girl Power Gone Wrong’: #MeToo, Aziz Ansari, and Media Reporting of (Grey Area) Sexual Violence.” Feminist Media Studies.

- Iyengar, Shanto. 1991. Is Anyone Responsible?: How Television Frames Political Issues. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Jones, Paul, and Michael Pusey. 2008. “Mediated Political Communication in Australia: Leading Issues, New Evidence.” Australian Journal of Social Issues 43 (4): 583–599.

- Jones, Paul, and Michael Pusey. 2010. “Political Communication and ‘Media System’: The Australian Canary.” Media, Culture & Society 32 (3): 451–471.

- Jørgensen, Marianne W., and Louise J. Phillips. 2002. Discourse Analysis as Theory and Method. London: Sage.

- Kluknavská, Alena, Jana Bernhard, and Hajo G. Boomgaarden. 2021. “Claiming the Crisis: Mediated Public Debates About the Refugee Crisis in Austria, the Czech Republic and Slovakia.” Journal of Refugee Studies 34 (1): 241–263.

- Koopmans, Ruud, and Paul Statham. 1999. “Political Claims Analysis: Integrating Protest Event and Political Discourse Approaches.” Mobilization: An International Quarterly 4 (2): 203–221.

- Koopmans, Ruud, Paul Statham, Marco Giugni, and Florence Passy. 2005. Contested Citizenship: Immigration and Cultural Diversity in Europe. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Lindekilde, Lasse. 2013. “Claims-Making.” In The Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Social and Political Movements, edited by D. A. Snow, D. Della Porta, B. Klandermans, and D. McAdam. Major Reference Works.

- Loney-Howes, R. E., and Bianca Fileborn. 2020. “#MeToo in Regional, Rural and Remote Australia: An Analysis of Regional Newspapers Reports Profiling the Movement.” International Journal of Rural Criminology 5 (2).

- Loney-Howes, Rachel, Kaitlynn Mendes, Diana Fernández Romero, Bianca Fileborn, and Sonia Núñez Puente. 2021. “Digital Footprints of #MeToo.” Feminist Media Studies.

- Mao, Frances. 2019. “2019 Election: Why Politics Is Toxic for Australia’s Women.” BBC News, May 16. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-australia-48197145.

- Mason, Paul, and Jane Monckton-Smith. 2008. “Conflation, Collocation and Confusion.” Journalism 9 (6): 691–710.

- Mendes, Kaitlynn, Jessalynn Keller, and Jessica Ringrose. 2019. “Digitized Narratives of Sexual Violence: Making Sexual Violence Felt and Known Through Digital Disclosures.” New Media & Society 21 (6): 1290–1310.

- Musto, Michela, Cheryl Cooky, and Michael A. Messner. 2017. ““from Fizzle to Sizzle!” Televised Sports News and the Production of Gender-Bland Sexism.” Gender & Society 31 (5): 573–596.

- O’Boyle, J., and Q. J. Y. Li. 2019. “#MeToo Is Different for College Students: Media Framing of Campus Sexual Assault, Its Causes, and Proposed Solutions.” Newspaper Research Journal.

- O’Hara, S. 2012. “Monsters, Playboys, Virgins and Whores: Rape Myths in the News Media’s Coverage of Sexual Violence.” Language and Literature: International Journal of Stylistics 21 (3): 247–259.

- O’Neill, Rachel. 2021. “Notes on Not Knowing: Male Ignorance After #MeToo.” Feminist Theory.

- O’Neill, Deirdre, and Tony Harcup. 2009. “News Values and Selectivity.” In The Handbook of Journalism Studies, edited by Karin Wahl-Jorgensen and Thomas Hanitzsch, 161–174. New York: Routledge.

- Phipps, Alison, Jessica Ringrose, Emma Renold, and Carolyn Jackson. 2018. “Rape Culture, Lad Culture and Everyday Sexism: Researching, Conceptualizing and Politicizing New Mediations of Gender and Sexual Violence.” Journal of Gender Studies 27 (1): 1–8.

- Roberts, Margaret E., Brandon M. Stewart, and Dustin Tingley. 2018. “Stm: R Package For Structural Topic Models.” Journal of Statistical Software 55 (2).

- Ross, Karen, and Cynthia Carter. 2011. “Women and News: A Long and Winding Road.” Media, Culture & Society 33 (8): 1148–1165.

- Statham, Paul, Ruud Koopmans, Marco Giugni, and Florence Passy. 2005. “Resilient or Adaptable Islam?.” Ethnicities 5 (4): 427–459.

- Yin, Siyuan, and Yu Sun. 2020. “Intersectional Digital Feminism: Assessing the Participation Politics and Impact of the MeToo Movement in China.” Feminist Media Studies.

- Young, Lori, and Stuart Soroka. 2012. “Affective News: The Automated Coding of Sentiment in Political Texts.” Political Communication 29 (2): 205–231.

- Zarkov, Dubravka, and Kathy Davis. 2018. “Ambiguities and Dilemmas Around #MeToo: #forhow Long and #WhereTo?” European Journal of Women’s Studies.

- Zhang, Wei, and Cheris Kramarae. 2014. ““SlutWalk” on Connected Screens: Multiple Framings of a Social Media Discussion.” Journal of Pragmatics 73: 66–81.