ABSTRACT

This article explores tax credits for political party funding in Aotearoa New Zealand (NZ). Participation in the democratic process is low and declining in NZ, as political party membership drops and parties increasingly focus their attention on small numbers of large donors. Advantages of tax credits include incentivising parties to engage with society to attract donations, encouraging individuals to participate in the democratic process and potentially providing greater financial support to parties. The primary disadvantage is that tax credits require at least a small financial contribution from a donor, which will not be possible for everyone. For a relatively low cost of approximately NZ$2.35 per voter, large donations could be eliminated from the NZ political funding system, along with the concomitant potential for undue influence. Using the Canadian model for comparison, a similar system in NZ may result in greater public political engagement and better funded political parties.

本文探讨了澳特罗亚新西兰政党基金税收减免的问题。新西兰民主过程的参与率很低,而且越来越低。政党成员的人数在减少,政党越来越在乎少数人的大额献金。税收减免的益处包括刺激政党联系社会吸引捐赠,鼓励个人参与民主过程,并潜在地为政党提供更大的资金支持。主要的弊端在于税收减免需要起码小额的捐赠,这并非人人都能办到。为了平均每票2.35元的低成本,需要在新西兰的政治献金体系中消灭大额捐赠及其过度的影响。以加拿大的模式做比较,同样的制度在新西兰可能导致更多的公共政治参与以及政党基金的优化。

Introduction

This article asks whether the system of tax credits could be used in Aotearoa New Zealand (NZ) to support political party funding.Footnote1 Globally, it is common for governments to use the tax system to encourage philanthropic donations. For example, in NZ a tax credit of 33 per cent may be claimed for donations to approved charities and organisations. However, the tax credit is not available if the donation is made to a political party. A different approach is adopted in Australia, where donations to an organisation with ‘deductible gift recipient’ status are tax deductible. However, unlike NZ, tax deductions may also be claimed for political contributions or gifts made by an individual in a personal capacity, up to a maximum of A$1,500 to registered political parties (Australian Tax Office Citation2017).

The reason why some countries elect to provide tax credits for eligible donations to political parties is to encourage participation in the democratic process, i.e. encouraging the public to engage with political parties and encouraging political parties to engage with the public.Footnote2 As noted by Wike and Castillo (Citation2018, 2) ‘an engaged citizenry is often considered a sign of a healthy democracy’. This is desirable because greater political participation increases the range of voices that are heard in policy debates and it ‘confer[s] a degree of legitimacy on democratic institutions’ (Wike and Castillo Citation2018, 2). Alongside political engagement of citizenry a further consideration is fundraising. It is important for democracy that political parties have access to funds to engage with potential voters (Wesley and Young Citation2022). Of course, the tax system is not the only mechanism to encourage political engagement. However, the tax system provides additional benefits such as increased transparency and, arguably and within limits, greater equality.

Globally there are myriad ways that political parties are funded. There is no one method, or combination of methods, that has proven superior to others. This perhaps reflects the complexity of political party funding. Tax credits combine both public and private funding. The public funding comprises the state contribution by way of tax credit, while the private funding comprises the individual donation to the party.

In 2022, several of the main NZ political parties faced Serious Fraud Office prosecutions resulting from non-compliance with election funding regulation. Behaviour in these cases included splitting large donations to avoid disclosure of the donor’s name, along with non-disclosure of large donations as required. This, together with other funding scandals, has generated questions on the suitability of the current regulations to ensure transparency of process and trust in the funding system. Therefore, adopting an exploratory approach, the article examines the potential advantages and disadvantages of adopting an alternative funding mechanism – tax credits. In doing so, this paper adds to the literature on political finance by illustrating how tax credits can generate greater engagement between political parties and donors, increase visibility of donations, broaden the donor base and potentially reduce reliance on a small number of wealthy donors.

We show that for a relatively low cost to the state (NZ$2.35 per voter per annum), that large donors could be eliminated from political party finance in NZ. Using the Canadian model as the basis for analysis, we find that the average donation would cost $68.75 for a donor and $206.25 for the state. The scheme would generate strong incentives for political parties to engage with the public and communicate their policies to attract donations. In addition, our calculations show that the system could result in political parties having more funding than under the current funding system.

This article commences by briefly exploring the primary methods of political party funding adopted globally. The strengths and weaknesses of these options are explored. This is followed by a discussion on the use of tax credits for funding purposes. The article then outlines NZ’s current approach to political party funding. Subsequently, a case study using Canada is presented, as an example of the successful, and long-lived, adoption of tax credits. A discussion follows, which considers the positive and negative implications of tax credits. Conclusions are drawn in the final section.

Political party funding options

This section explores the most common political party funding options, together with their advantages and disadvantages. The section is split into two sub-sections: private donations and state funding, as the two primary mechanisms to fund political parties. With public funding, the government provides some or all funding. Private funding may include donations from individuals, corporations and other entities such as trade unions or trusts. There is a balance to be achieved in minimising the potential for perceived or actual influence from private donations and ensuring parties do not lose connections to their membership base if they are fully state funded. Balance is also needed to ensure that funding mechanisms do not unfairly benefit large or incumbent parties.

Private donations

A key concern with private donations is that those who are wealthier have greater capacity to make political donations. As noted by Tham and Young (Citation2006, 8) ‘the promise of democracy is that each citizen will share equally in political power’. When some are more able to donate than others, the perception may be that some have greater share – or greater influence (Gilens and Page Citation2014). As perception of undue influence can harm the public’s trust and support for elected representatives, the democratic process is damaged even when influence is absent (The Australian Senate Citation2018).

Therefore, while most countries allow for private donations to political parties, there are usually constraints on these donations. For example, some countries have upper limits on donations, some countries disallow donations from non-natural persons, and some prohibit donations from non-residents or non-citizens.Footnote3 It is common for countries to ban foreign donations or to have these set at a very low threshold. In the NZ context, Geddis (Citation2007, 6) writes: ‘the legitimacy of persons who are not eligible to vote in this country’s elections funding those who are contesting them is debatable, to say the least’. There are additional differences around transparency and disclosure, where there is a balance between wanting to protect people’s private spending and not deter donations, while allowing visibility into the process.

As noted, private funding of political parties creates the potential for a donor to obtain undue influence over the political process (Leong and Hazelton Citation2017; Tello, Hazelton, and Leong Citation2019). In Australia, political parties rely on a small number of large donors. For example, in 2020–21, 39 and 57 per cent of the Coalition’s and Labor’s declared donations, respectively, came from five donors, leading to the suggestion that ‘these donors can achieve significant access and influence’ (Griffiths and Emslie Citation2022). Influence extends to the relatively small group of donors that contribute to fundraising events in Australia, where access to Ministers may be available (Wood, Griffiths, and Chievers Citation2018). It is notable that in Australia, it is highly regulated industries that contribute the biggest share of political donations (Wood, Griffiths, and Chievers Citation2018).

While regulation exists in most countries to promote transparency of donations, there are also suggestions that these rules can be worked around. For example Chapple and Anderson argue that NZ political parties have found creative ways to avoid and potentially evade regulation on donations reporting, including through ‘use of trusts, anonymous donations, auctions, donation splitting and inter-temporal transfer of donations’ (Chapple and Anderson Citation2021, 20). Similarly, in Australia, Griffiths and Emslie (Citation2022) suggest that with a relatively high threshold of A$14,300 for declaration of individual donations, large donors can split their donations into several separate payments below this threshold to avoid transparency of disclosure. This behaviour has been visible recently in NZ (Murphy Citation2022).

A concern with private funding is that it is likely to benefit larger incumbent parties, which may impact on the ability of new or small parties to attract similar levels of funding. This can be ameliorated by caps: either on donations or expenditure. Many countries have upper spending limits on donations to a political party, although sometimes these are high.Footnote4 However, there is some debate on whether capping donations or expenditure is beneficial. In NZ, Bryce (Citation2008, 12) provides evidence showing that the wealthiest parties have received ‘relatively poor value for money from their expenditure’, when examining spending to vote ratios from the 2005 election. However, more recent literature suggests correlations between higher spending on election campaigning results and greater election success (Schuster Citation2020; Cagé and Dewitte Citation2021; Bekkouche, Cage, and Dewitte Citation2022). Therefore, arguments for capping expenditures may appeal to equity considerations.

Survey findings from NZ show strong support for capping donations to political parties (Chapple, Duran, and Prickett Citation2021). As shown in , 43.7 per cent of people prefer for the cap to be less than $1,000, with a further 25.6 per cent preferring this to be under $10,000. There is no limit to donations at the present time in NZ, but only 17.6 per cent of survey respondents indicated this as their preference.

Table 1. How much should people be permitted to donate?a

State funding

Most countries have some form of state support for political parties. There are typically two forms of public funding: direct election funding in the form of specific grants or services, and indirect funding, such as tax subsidies (Jenson Citation1991). Election funding is usually provided after an election, with some proportionate allocation based on votes. There has been a worldwide trend towards increases in the share of state subsidies that comprise total party income in recent decades, with state funding now ‘generally accounting for a clear majority of party funding’ in Europe (European Parliament Citation2021, 7).

Direct state funding takes different forms, but typically is associated with dollar values for votes received above a minimum threshold. Sometimes there may be an additional lump sum payment. Reimbursement of election spending is a further option, with the advantage that it doesn’t encourage overspending if it is capped in some way, although it may advantage wealthier parties.

There are several advantages of state funding. Perhaps the most obvious is that it means that parties do not have to rely on fundraising to attract donations (Australian Government Citation2008). Added benefits are transparency and minimising opportunity to influence policy. Depending on the policy design, state funding may also help with ensuring that parties are well-resourced to undertake democratic duties.

An issue with state funding is designing funding that does not advantage large incumbent parties. However, state funding may reduce the incentive for political parties to engage with their members or society in general, if they do not need their assistance in fundraising (Tham Citation2010). Furthermore, state funding may be unpopular as some will not believe that political parties should be a priority for funding when resources are constrained (Australian Government Citation2008).

Tax credits and tax deductibility provide a further opportunity to make a tax-preferred political donation in some countries. While neither of these are currently available in NZ (discussed further later in this article), other countries sometimes allow for a tax credit or a tax deduction. By way of illustration, in Australia, individuals who make gifts or contributions to political parties and politicians in a personal capacity may claim the expenditure as a tax deduction (Australian Tax Office Citation2017). However, deductions are capped at A$1,500 for contributions to both political parties and A$1,500 for contributions to independent candidates and members. A membership subscription to a registered political party is permitted as a tax deduction for an individual. Businesses cannot claim the same deductions.

Tax credits or deductions are usually capped at fairly small amounts, with the intended aim of encouraging small donations and diversification of the funding base (Tham Citation2010). While tax credits or deductions may achieve that, the tax benefit is gained by the taxpayer, rather than the political party (Tham Citation2010). Therefore, parties or candidates may receive no incremental funding from the existence of the tax credit or deduction, if they do not incentivise more donors. Notwithstanding that possibility, the presence of the tax credit or deduction reduces the cost of the donation to the donor, and therefore is intended to encourage donations.

Surveys undertaken by Chapple over the period from 2016 to 2020, indicate around 75 per cent of New Zealanders regularly report not much, little or no trust in the way political parties are funded (Chapple Citation2020). In support of public funding, Chapple writes ‘by eliminating the big donations, parties will be forced once again to work towards mass membership so they can access members’ time as a resource to pursue political office’ (Chapple Citation2020). However, elimination of large donations requires alternative funding mechanisms. Tax credits are one potential alternative.

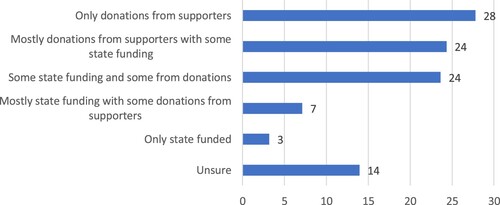

We collected data from a survey of just over 1,000 respondents and asked respondents what they believed was the right balance of funding for political parties.Footnote5 The responses are shown in . While 28 per cent believed that political parties should not receive any state funding, 58 per cent supported at least some state funding.

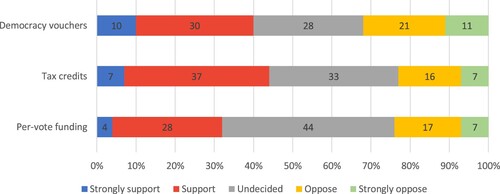

We also asked our survey respondents their views on three different forms of state funding: democracy vouchers,Footnote6 tax credits, and per-vote funding. We provided some context, including advantages and disadvantages, of each of the options. The results are shown in . Among the three options provided, tax credits were the most attractive to respondents, with 44 per cent supporting or strongly supporting this option. Democracy vouchers were second, with 40 per cent supporting or strongly supporting this option, and per-vote funding was the least attractive with 32 per cent support. We focus on the most attractive option, tax credits, for the remainder of this article.

Tax credits

Prior to commencing a discussion on tax credits, it is important to clarify that the trade-off for tax credits would be limiting private donations. The primary argument for placing a cap on private donations – and essentially replacing private funding with public funding – is to minimise the opportunity for vested interests to use their wealth to influence political decisions. There is a growing body of research illustrating this influence. For example, research from the US has shown how governments’ decisions typically align with elite preferences, rather than the broad public interest (Gilens and Page Citation2014; Kuhner Citation2021) while research from the UK has established that large party donations are linked to appointments in the House of Lords, a law-making body (Mell, Radford, and Thévoz Citation2015).

Our own analysis of 32 OECD countries shows that only one-third of the countries, including NZ, allow unlimited donations (Rashbrooke and Marriott Citation2022). In Australia, Griffiths and Emslie (Citation2022) find that large donors to political parties can achieve ‘significant access and influence’, a finding supported by several other studies (de Figueiredo and Edwards Citation2007; Witko Citation2011; Bromberg Citation2014; Moxon Citation2022). As well as the issue with access, there is an equality concern as the access is only available to those who can afford large donations.

There are two primary mechanisms by which the tax system can support political donations. These are tax deductions or tax credits. Tax deductions allow for the donor to treat the donation as an expense, which reduces taxable income. Tax credits offset income tax that is due to be paid. The benefit to the taxpayer with both tax deductions and tax credits, is an overall reduction in the individual’s tax paid. However, under the tax deduction, tax is calculated on income after the donation has been deducted, reducing the tax payable. Whereas with the tax credit, tax is calculated on income before the donation is deducted and a tax credit must usually be applied for after the donation has been made. Therefore, there are timing and compliance advantages with a tax deduction.

A tax deduction provides a greater benefit to a higher income earner, that is, someone who is paying a higher marginal income tax rate. Whereas the tax benefit from a tax credit accrues equally to all donors. While it may therefore appear that a tax credit is preferable on equity grounds, some have argued that a tax credit system may reduce the financial incentive for wealthier individuals to donate, when compared to a system that involves deductions (Throsby and Withers Citation1979). However, tax credits for political donations usually have relatively low upper thresholds, so this argument is less relevant for political donations than, say, donations to the arts.

With all donations, there is the issue of who can participate, which is often those who are wealthier and have the discretionary income to make donations (Jansen and Young Citation2011). Thus, one of the arguments for tax credits is they promote equality. As noted by Carmichael and Howe (Citation2014) ‘the very essence of democracy is equality’. A generous tax credit can allow for democratic participation among lower income earners than would otherwise be possible.

While Young (Citation2012) argues that a tax credit for political donations is democratically desirable, as it encourages political parties to solicit small contributions from individuals, donations tend to come from higher income earners, meaning that participation in the tax credit is ‘not neutral in socio-economic terms’ (Young Citation2012, 145). Similarly, Carmichael and Howe (Citation2014) report that 37 per cent of their donor sample were resident in the top income earning quintile, while 10 per cent were in the lowest. This finding became more pronounced when examining those making the largest donations, i.e. those over C$750. These donors comprised 52 per cent of the top income earning quintile, compared to 8 per cent who were in the lowest quintile. However, income is mediated by political interest, as higher levels of political interest are associated with higher levels of income (Jansen, Thomas, and Young Citation2012). Notwithstanding this, while some diversification of donors may result from the tax benefit, some in society will remain unable to participate.

Tax credits for donations are a form of public financial support for political parties (Jansen and Young Citation2011). Using tax terminology, a tax credit is a ‘tax expenditure’ as it is revenue forgone, rather than an actual outgoing. Like all tax expenditures, these can be accused of being less transparent than actual outgoings. It is also more difficult to project what the financial support from the government will be, as the total cost will be determined by individual uptake. Jenson suggests that tax credits ‘partially disguise the fact that the state is spending money’, claiming they are not as visible to the public, despite being a real cost. Instead, they often appear as private funding that involves less state activity (Jenson Citation1991, 147).

One advantage of tax credits is they can provide support for parties in the period between elections (Jenson Citation1991). While many state funding tools provide for funding primarily around elections, it is important for political parties to have funds to engage with citizens outside of an election period. Therefore, tax credits recognise the importance of activity throughout the electoral cycle (Jenson Citation1991). The three major federal parties in Canada in the 1980s were able to substantially grow their sources of funding, and the amounts of funding, in large part resulting from the tax credit provided by the Canada Elections Act (Jenson Citation1991).

Unlike a direct annual public subsidy, the political contribution tax credit generates an incentive for parties to solicit donations and the smallest contributions generate the greatest incentives (Young Citation1998; Jansen and Young Citation2011). This encourages parties to engage with their membership base as well as other members of society (Young Citation1998; Marziani and Skaggs Citation2011). There is an argument that tax credits allow for greater equality of the democratic process. Parties only receive funding where they have convinced taxpayers that they are worthy of their donation and citizens effectively control where the state funding goes. Conversely, the visibility afforded to large incumbent parties is likely to act in their advantage in the same way as vote related funding.

One of the aims of providing a tax credit for political contributions is to encourage participation in the democratic process. Boatright and Malbin (Citation2005) examine the impact of tax credits on the propensity of citizens to contribute to a party or candidate. Their study involved the introduction of a 100 per cent tax credit in Ohio for the first US$50 contribution to a state candidate. A survey asked Ohio residents about their awareness of the tax credit and how it influenced their decision to make a political contribution. The findings suggest that if citizens are aware of the tax credit, the number of contributors was likely to increase, and the donor pool was likely to resemble the general population more closely than in the absence of the tax credit. Boatright and Malbin (Citation2005) also report that eight per cent of donors said the tax credit influenced their donation decision, with five per cent who said they would have donated had they known about the tax credit. However, later research finds contrasting results, reporting that publicising incentives, such as tax credits, did little to enhance new donors (Schwam-Baird et al. Citation2016).

Despite the potential benefit of tax credits, they are not widely used to encourage political engagement. Among European countries, France provides a tax credit for residents who donate to an approved political party funding association, or a political party. The maximum tax benefit is €7,500 per person and €15,000 per tax household per year (Cabinet Roche and Cie Citation2019). The reduction is 66 per cent tax relief of the amount paid up to a maximum 20 per cent of taxable income.

As noted earlier Canada has a system of tax credits for political party donations. The United States of America had federal tax credits between 1972 and 1986, with an average of just under four per cent of tax returns claiming the credit (Norden and Keith Citation2017). In recent decades, a small number of states have permitted residents to claim tax credits, typically with a 100 per cent tax credit for the first US$50 donation (Norden and Keith Citation2017).Footnote7

Political party funding in Aotearoa New Zealand

NZ has regulated the use of money, or goods and services at election time since 1858 (Geddis Citation2014). It has only been in the last two decades that these rules have become more stringent. After several incidents that challenged the integrity of the existing rules around the 2005 election campaign, a review took place that highlighted issues within the existing regulatory framework (Geddis Citation2007). The review resulted in various changes that were intended to provide greater certainty and transparency in the electoral process (New Zealand Parliament Citation2010). A further review occurred after the 2017 General Election, resulting in additional changes, particularly relating to foreign donations and Party Secretary due diligence (Justice Committee Citation2019).

Donations may be monetary, goods or services, or provision of goods and services below market value (Electoral Act 1993 s 207(2)). However, donations exclude the provision of free labour to a candidate, and the provision of goods or services by a NZ person to a candidate that have a market value of less than $300, or $50 where the same provision is by an overseas person (Electoral Act 1993 s 207(2)). Donations of goods and services at less than market value are also included, where the market value is greater than $1,500 or $50 from an overseas person.

Political parties are required to report donations to the Electoral Commission in an annual return. At the present time these are: the name of every donor who donated over $15,000 during the year; every anonymous donation over $1,500; all donations from an overseas person over $50, including a body corporate or unincorporated body with a head office or principal place of business outside NZ (Electoral Act 1993 s 207(2)).Footnote8 In addition, anonymous donations that are channelled through the Electoral Commission must be disclosed, i.e. protected disclosures. NZ has relatively few protected disclosures: two per cent of funding in the 2020 election year, one per cent in the 2017 election year, and two per cent in the 2014 election year (Electoral Commission Citation2022). Additional disclosures required are the number of party donations over $1,500 but less than $5,000 and the total value of these donations; the number of party donations over $5,000 but less than $15,000 and the total value of these donations. Equivalent disclosures for loans are also mandated.

In NZ, political parties have been subject to spending limits on election expenses since 1996, and third party promoters have had spending limitations since 2008 (Geddis Citation2007). However, these limits apply to a relatively narrow range of electoral activity relating to advertising during the three-month regulated period. Many activities, such as candidate travel, renting campaign offices, advertising prior to the regulated period or opinion polling is not included within the cap (Geddis Citation2021).

Members of Parliament receive state funding for their parliamentary duties. This funding is for parliamentary work, such as making laws, rather than for campaigning. The other main source of state funding in NZ is the election broadcasting allocation. The Electoral Commission distributes this fund to political parties for campaign advertising. In 2020, the most recent election year, the total value of this fund was $4.15 million (Electoral Commission Citation2020).

State funding options have been canvassed previously in NZ. For example, in 1986 a Royal Commission proposed the introduction of state funding. This would involve party funding of $1/party vote, up to 20 per cent of total, and $0.50c for additional party votes. There was a proposed threshold for payment of receiving one per cent of the total party vote (Royal Commission Citation1986). This was explored further in 2007, where the proposal was that parties would receive funding based on party votes received at the previous election. Funding amounts were proposed to be $2.00/vote for each party vote, up to 20 per cent of the total party vote, and $1.00 per vote for additional party votes up to a total cap of 30 per cent (Cabinet Decision Citation2007a). While this second proposal was agreed in a Cabinet Minute, the decision was rescinded shortly thereafter (Cabinet Decision Citation2007b).

In NZ, tax credits or tax deductions are not available for political donations. Political parties cannot be a charity and therefore cannot be an approved donor for the purposes of receiving tax credits. Donations to political parties or candidates do not qualify as a tax deduction in NZ, as the expenditure would not meet the required nexus with the income earning process (Income Tax Act 2007 s DA 1).

Political party funding in Canada

This section briefly outlines some core components of political party funding in Canada. Canada has successfully used tax credits for political party funding for several decades. Canada is a useful comparator for NZ, as a British colony with similar political institutions. However, Canada has a tougher approach to regulating party funding. Donations must be disclosed at a low level (over NZ$200) and the total amount of donations that may be given to a political party in any year is around NZ$2,000.

Canada’s system of government is a federal parliamentary democracy. The Canadian Parliament is bicameral, with a House of Commons and Senate. A ‘first past the post’ voting system is in place. Canadians vote only for their local Member of Parliament, who may be independent or a member of a political party. Five political parties had representatives elected to the Federal Parliament at the last election in 2021, including the Liberal Party who currently form the government. The official opposition party is the Conservatory Party, while other smaller parties are the New Democratic Party, the Block Québécois, and the Green Party of Canada.

The foundation for the regulatory regime governing party and election finance was established in 1974 (Young Citation2012). However, new rules on political financing were introduced in 2003 and again in 2014.Footnote9 Among the changes were that only individuals may make contributions to registered political parties and changes in the thresholds to contribution limits. Current contribution limits for 2022 are C$1,675 annual limit to each registered political party, and C$1,675 in total to all registered associations and candidates of each registered party (Elections Canada Citationn.d.). These amounts include loans. Companies and trade unions are not permitted to make political contributions (Elections Canada Citationn.d.).

The 1974 changes established the political contribution tax credit that provides a tax credit for small donations from natural persons (Young Citation2012). As observed by Young ‘this is an extraordinarily generous tax credit and one that the parties employ to help them solicit contributions from individuals’ (Young Citation2012, 145). The emphasis on increasing participation is visible, as the goal was ‘to disperse among the citizenry the power to act politically’ through the tax credit (Young Citation1998).

Tax credits

While contributions may take the form of goods or services, or other assistance such as forbearance of interest on loans, it is only monetary contributions to a registered federal political party, a registered association or a candidate in a federal election that qualify for an income tax credit under the Income Tax Act (Elections Canada Citationn.d.). shows the donation amounts that apply from 2004 in Canadian dollars and NZ dollar equivalents.

Table 2. Tax credits for donations made after 2004.

Discussion

There is some indication that individuals would like to see more restrictions on private funding in NZ. As per in section two of this article, over two-thirds of people responded that this cap should be $10,000 or less. Noting that there is currently no upper limit for political party donations, if a cap was placed on such donations, some form of replacement funding would be required. If tax credits were used to fill this gap, it would require political parties to engage much further with their constituent base, to encourage participation by many smaller donors.

Section two outlined several issues that arise from private and public funding options. There are several additional issues that have risen more recently, as election regulation has not adapted to the changing nature of elections and campaigns. These issues specifically related to technology, the use of social media and increased use of third parties. Some of the problems identified include:

the use of technology to facilitate small donations, including from overseas, which reduces the intended transparency in current regulation;

the relative ease associated with using unincorporated associations to hide separate donations;

lack of timely reporting on donations, where donations are made visible only after elections results are finalised;

the ability for lobby groups to act as proxies for parties; and

the ability for overseas influence into elections on platforms that are held in overseas locations and can be funded from overseas sources (Electoral Reform Society Citation2019).

While tax credits in isolation cannot address all these issues, they can assist with some components. The advantage with tax credits is that they are visible: for a donor to receive a tax credit, their identity must be known. Where the tax credit is only available to an individual, this minimises the potential for splitting of donations including through companies, hiding overseas donations or channelling donations through lobby groups (note that this is not covered in this article).

The policy settings of a tax credit are likely to have a significant impact on their uptake. Where a 100 per cent credit exists, greater political engagement is likely. The advantage with a 100 per cent tax credit is it expands the ability of some to engage politically. Lower income earners are less likely to have the discretionary income to make political donations. To the extent that they are costless, tax credits create an environment for all interested people to be politically engaged.

In Canada, the existing tax credits increased in generosity in 2004. Young (Citation2012) reports that between 2002 and 2008, the number of individuals who made contributions to registered political parties increased by 44 per cent. While causality is not claimed, Young suggests that the figure is likely to continue to increase as parties work to increase their pools of donors as public subsidies are phased out.

A benefit of tax credits is they bridge the middle ground between state and private funding. The funds are provided by the state, but the allocation is determined by citizens when they donate. Thus, while they are funded by the state, they may be more politically acceptable than direct state funding.

Influence, or the perception of influence, is problematic in political party funding. One way to address this problem is to cap the maximum amount of donation that may be made by any one individual or entity. However, the disadvantage is that political parties receive significant amounts by way of large donations, and it requires considerably more effort to attract equivalent amounts of funding through small donations. If the option to have large donations was removed, but tax credits were introduced, political parties would need to work to engage with their supporters to obtain the funding that was lost from large donors.

For those who cannot donate, there may be a challenge to equity as these groups (along with all taxpayers) subsidise the tax credits that are claimed by those who can donate. Therefore, the potential remains for the tax credits to be a transfer of funds from the less wealthy to those who are wealthier. However, as shown in our calculations below, the average donation amount would cost a donor less than NZ$70.

A potential issue with tax credits is when tax incentives are implemented, there will inevitably be attempts to gain by fraud. An example from Canada is the SNC-Lavalin case, where the company reimbursed employees’ (and their spouses’) donations to the federal Liberal Party, as corporations are not permitted to donate. The reimbursements took place for a decade before being discovered in 2019. Reports suggest this resulted in almost C$118,000 of the company’s funds being directed to political parties (Smith Citation2019). However, the primary disadvantage with tax credits is the cost, as discussed below.

To fully understand whether tax credits could be used as a substitute for private donations, we need some understanding of how much money is required to run a campaign. The amount of large donations made to political parties in 2020 (an election year in NZ) are outlined below in . All parties that attracted donations above $100,000 are included in the table, showing total private donations are just under $7 million.

Table 3. Donations to NZ political parties (2020).(1)

In 2020 a total of 1,606 individual donors were noted on the above 10 political party donation annual returns (Electoral Commission Citation2022), although this captures only donations that need to be declared. The numbers of multiple small donors are not in this total. Canada is approximately 7.5 times the size of NZ, measured by population. shows the value of donations, the number of donors, the proportion of votes received and the average donation per donor for the five largest political parties in the most recent election year, 2021.

Table 4. Financial information for Canada’s five largest political parties (2021 – Canadian $).

The total number of donors in 2021 across the five Canadian parties was 248,080. Adjusted for the NZ population, this would equate to approximately 33,000 donors in NZ, assuming roughly equivalent political participation. The average value of donations across the five parties is C$239 (NZ$275). Again, assuming a similar contribution in NZ, this would total just over NZ$9 million: 30 per cent more than what was donated in the last election year. Under the proposed model, parties may still accept donations beyond those that attract the tax credit. However, they would not be unlimited as they are presently. Therefore, private donations would remain an additional funding mechanism for parties.

The cost to a donor, for an average donation, would be $68.75, i.e. 25 per cent of the average $275 donation. The cost to the government for this approach, again assuming an average donation value of NZ$275 made by 33,000 donors, would be NZ$6.8 million.Footnote10 Therefore, for roughly NZ$2.35 per voter,Footnote11 large donations and its attendant opportunity for undue influence could be eliminated from the New Zealand political funding system. In practice, the cost to the government would be lower than this as not all tax credits would be claimed. Research from Canada suggests this could be nearly 50 per cent of eligible tax credits (Jansen and Young Citation2011).

Conclusion

The use of alternative funding mechanisms for political parties in NZ has the potential to improve trust in the funding system and to ensure the voting public that a small number of wealthy individuals do not receive undue influence from their large financial donations to parties they support. The advantages of tax credits are that they do not favour the interests of the wealthy, they facilitate the organisation of individuals who lack political capital, the market approach has the capacity to reflect the intensity of voter preferences effectively, and it has the political to be politically appealing (Hasen Citation1996). As shown in the above analysis, informed by the Canadian model, political parties may be better funded if tax credits were introduced.

Depending on the policy design, donations may remain inaccessible to those on low incomes or to those with few resources. However, a scheme such as that used by Canada, that has a generous tax credit for a relatively small donation, which decreases as the donation becomes larger, may address this potential inequity. Our analysis suggests that the average donation would cost $68.75 for a donor and $206.25 for the state, but would require parties to engage with the public to attract these donations. We observe the need to strengthen other donation regulation to fully achieve the benefits from tax credits.

An important trade-off is introducing an upper donation limit to remove the potential influence that is often attributed to large donations. This would improve trust and transparency in the political party funding system. As shown in our calculations, for approximately NZ$2.35 per voter per annum, ‘big money’ could be eliminated from the NZ political party funding.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Lisa Marriott

Lisa Marriott is a Professor of Taxation at Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand and an Extraordinary Professor at the University of Pretoria, South Africa.

Max Rashbrooke

Max Rashbrooke is a Senior Associate at the Institute for Governance and Policy Studies at Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand.

Notes

1 The article focuses on political parties, rather than candidates. However, in many countries, similar funding rules apply to candidates and parties.

2 Reference to participation in this article relates to donating money, rather than voting or other political activity.

3 For example, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Finland, France, Greece, Iceland, Ireland and Slovenia (among others) all have upper limits on donations; and Belgium, Canada, France, Israel, Latvia, Lithuania and Poland ban donations from companies and trade unions (Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance Citation2022). In Canada, only citizens and permanent residents may donate to political parties (Elections Canada Citationn.d.).

4 For example, among European Union Member States, only eight (Bulgaria, Denmark, Estonia, Germany, Hungary, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and Sweden) have no maximum size of private contribution to political entities. The average across the remaining 19 Member States is €53,000, ranging from €500 in Belgium to €300,000 in Slovakia (European Parliament Citation2021).

5 The survey was conducted online from 22–27 September 2022. It polled a nationally representative sample of 1,004 people, all aged over 18 years of age. The margin of error is ±2.9 per cent.

6 Democracy vouchers are used in the city of Seattle, in the United States of America. At the start of an election year, every enrolled voter is sent four US$25 vouchers that can be allocated to candidates of their choice.

7 See Norden and Keith (Citation2017) for a comprehensive account of the development of federal tax incentives in the United States. States that have a 100 per cent tax credit for the first $50 are Oregon, Ohio and Arkansas.

8 Note that proposed new legislation will require parties to identify any donor who donates more than $5,000 a year – this is a reduction from the current $15,000.

9 For a comprehensive account of the historical developments in Canada, see Beange (Citation2012).

10 Calculated at 75 per cent of the total. This assumes a similar tax credit scheme to what exists in Canada.

11 There were 2,894,486 voters at the last NZ general election in 2020.

References

- Australian Government. 2008. Electoral Reform Green Paper: Donations, Funding and Expenditure. Canberra: Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet.

- Australian Senate. 2018. Select Committee into the Political Influence of Donations. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

- Australian Tax Office. 2017. “Claiming Political Contributions and Gifts.” https://www.ato.gov.au/non-profit/gifts-and-fundraising/in-detail/fundraising/claiming-political-contributions-and-gifts/#:~:text=You%20need%20to%20claim%20your,to%20independent%20candidates%20and%20members.

- Beange, Pauline. 2012. “Canadian Campaign Finance Reform in Comparative Perspective 2000–2011: An Exhausted Paradigm or Just a Cautionary Tale?” PhD diss., University of Toronto.

- Bekkouche, Yasmine, Julia Cage, and Edgard Dewitte. 2022. “The Heterogeneous Price of a Vote: Evidence from Multiparty Systems, 1993–2017.” Journal of Public Economics 206: 104559. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2021.104559.

- Boatright, Robert G., and Michael J. Malbin. 2005. “Political Contribution Tax Credits and Citizen Participation.” American Politics Research 33 (6): 787–817. doi:10.1177/1532673X04273418.

- Bromberg, Daniel. 2014. “Can Vendors buy Influence? The Relationship Between Campaign Contributions and Government Contracts.” International Journal of Public Administration 37 (9): 556–567. doi:10.1080/01900692.2013.879724.

- Bryce, Edwards. 2008. “Political Finance and Inequality in New Zealand.” New Zealand Sociology 23 (2): 1–14.

- Cabinet Decision. 2007a. “Minute of Decision, CAB Min 07: 8/5”.

- Cabinet Decision. 2007b. “Minute of Decision, CAB Min 07: 16/8”.

- Cabinet Riche and Cie. 2019. “Income Tax in France: Tax Reductions and Credits.” https://www.cabinet-roche.com/en/french-tax-reduction-income-tax-in-france/#:~:text=French%20tax%20reduction%20%3A%20Donations%20to%20a%20political%20party,66%25%20of%20the%20amounts%20paid.

- Cagé, Julia, and Edgard Dewitte. 2021. “It Takes Money to Make MPs: New Evidence from 150 Years of British Campaign Spending”.

- Carmichael, Brianna, and Paul Howe. 2014. “Political Donations and Democratic Equality in Canada.” Canadian Parliamentary Review Spring: 16–18.

- Chapple, Simon. 2020. “How to Drop Big Money from NZ Politics.” Institute for Governance and Policy Studies. https://www.wgtn.ac.nz/igps/commentaries/how-to-drop-big-money-from-nz-politics.

- Chapple, Simon, and Thomas Anderson. 2021. “Who’s Donating? To Whom? Why? Patterns of Party Political Donations in New Zealand Under MMP.” Policy Quarterly 17 (2): 14–20. doi:10.26686/pq.v17i2.6818.

- Chapple, Simon, Cristhian Prieto Duran, and Kate Prickett. 2021. “Political Donations, Party Funding and Trust in New Zealand.” Institute for Governance and Policy Studies Working Paper 21/14.

- de Figueiredo, Rui, Jr., and Geoff Edwards. 2007. “Does Private Money Buy Public Policy? Campaign Contributions and Regulatory Outcomes in Telecommunications.” Journal of Economics & Management Strategy 16 (3): 547–576. doi:10.1111/j.1530-9134.2007.00150.x.

- Elections Canada. 2021. Canadian Election Results By Party 2021 (Sept 20).

- Elections Canada. 2022. Registered Party Financial Returns.

- Elections Canada. n.d. “The Electoral System of Canada.” Accessed July 13, 2022. https://www.elections.ca/content.aspx?section=res&dir=ces&document=part6&lang=e.

- Electoral Commission. 2020. “Broadcasting Allocation Decision 29 May 2020.” https://elections.nz/guidance-and-rules/for-parties/about-the-broadcasting-allocation/.

- Electoral Commission. 2022. “Party Donations and Loans by Year.” https://elections.nz/democracy-in-nz/political-parties-in-new-zealand/party-donations-and-loans-by-year/.

- Electoral Reform Society. 2019. “Fair Elections Under Threat? The Loophole List.” https://www.electoral-reform.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Fair-elections-under-threat-The-Loophole-List.pdf.

- European Parliament. 2021. Financing of Political Structures in EU Member States: How Funding is Provided to National Political Parties, Their Foundations and Parliamentary Political Groups, and how the use of Funds is Controlled. Brussels: Policy Department for Budgetary Affairs.

- Geddis, Andrew. 2007. “Rethinking the Funding of New Zealand’s Election Campaigns.” Policy Quarterly 3 (1): 3–10.

- Geddis, Andrew. 2014. Electoral Law in New Zealand: Practice and Policy. 2nd ed. Wellington: LexisNexis.

- Geddis, Andrew. 2021. “Funding New Zealand’s Election Campaigns: Recent Stress Points and Potential Responses.” Policy Quarterly 17 (2): 9–13. doi:10.26686/pq.v17i2.6817.

- Gilens, Martin, and Benjamin I. Page. 2014. Testing Theories of American Politics: Elites, Interest Groups, and Average Citizens. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Griffiths, Kate, and Owain Emslie. 2022. “$177 Million Flowed to Australian Political Parties Last Year, but Major Donors Can Easily Hide.” The Conversation, February 1. https://theconversation.com/177-million-flowed-to-australian-political-parties-last-year-but-major-donors-can-easily-hide-176129.

- Hasen, Richard L. 1996. “Clipping Coupons for Democracy: An Egalitarian/Public Choice Defense of Campaign Finance Vouchers.” California Law Review 84 (1): 1–59. doi:10.2307/3480902.

- Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance. 2022. “Political Finance Database.” https://www.idea.int/data-tools/data/political-finance-database.

- Jansen, Harold J., Melanee Thomas, and Lisa Young. 2012. “Who Donates to Canada’s Political Parties?” Annual Conference of the Canadian Political Science Association, Edmonton, June.

- Jansen, Harold J., and Lisa Young. 2011. “State Subsidies and Political Parties.” Policy Options, 43–47.

- Jenson, Jane. 1991. “Innovation and Equity: The Impact of Public Funding.” In Comparative Issues in Party and Election Finance, edited by F. Leslie Seidle, 111–178. Toronto and Oxford: Dundurn Press.

- Justice Committee. 2019. Inquiry into the 2017 General Election and 2016 Local Elections, Presented to the House of Representatives. https://www.parliament.nz/resource/en-NZ/SCR_93429/5dd1d57eeba54f36bf9f4da96dba12c073ed7ad8.

- Kuhner, Tim. 2021. “Representative Democracy in an Age of Inequality.” Policy Quarterly 17 (2): 21–28. doi:10.26686/pq.v17i2.6819.

- Leong, Shane, and James Hazelton. 2017. “Improving Corporate Political Donations Disclosure: Lessons from Australia.” Social and Environmental Accountability Journal 37 (3): 190–202. doi:10.1080/0969160X.2017.1336108.

- Marziani, Mimi Murray Digby, and Adam Skaggs. 2011. “More Than Combating Corruption: The Other Benefits of Public Financing.” Brennan Center for Justice.

- Mell, Andrew, Simon Radford, and S. Thévoz. 2015. “Is There a Market for Peerages? Can Donations buy you a British Peerage? A Study in the Link Between Party Political Funding and Peerage Nominations, 2005–14.” Department of Economics Discussion Paper 744. University of Oxford.

- Moxon, Sophie Louise. 2022. “Can Money buy Access? Political Finance Contributions and the Impact on Interest Group Access to Legislative Committees in Australia, Canada, Ireland, and the United Kingdom.” PhD thesis, University of York.

- Murphy, Tim. 2022. “The Monied Class Who Funded Winston Peters.” Newsroom 9 Jun 2022 https://www.newsroom.co.nz/millionaires-for-nz-first.

- New Zealand Parliament. 2010. “Electoral (Finance Reform and Advance Voting) Amendment Bill”.

- Norden, Lawrence, and Douglas Keith. 2017. Small Donor Tax Credits: A new Model. New York: Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law.

- Rashbrooke, Max, and Lisa Marriott. 2022. “A Reform Architecture for Political Party Funding in Aotearoa New Zealand.” Policy Quarterly 19 (1): 73–78. doi:10.26686/pq.v19i1.8108.

- Royal Commission on the Electoral System. 1986. Report of the Royal Commission on the Electoral System 1986. https://elections.nz/democracy-in-nz/what-is-new-zealands-system-of-government/report-of-the-royal-commission-on-the-electoral-system/.

- Schuster, Steven Sprick. 2020. “Does Campaign Spending Affect Election Outcomes? New Evidence from Transaction-Level Disbursement Data.” The Journal of Politics 82 (4): 1502–1515. doi:10.1086/708646.

- Schwam-Baird, Michael, Costas Panagopoulos, Jonathan S. Krasno, and Donald P. Green. 2016. “Do Public Matching Funds and Tax Credits Encourage Political Contributions? Evidence from Three Field Experiments Using Nonpartisan Messages.” Election Law Journal: Rules, Politics, and Policy 15 (2): 129–142. doi:10.1089/elj.2015.0321.

- Smith, Marie-Danielle. 2019. “Liberals Accused of Cover-up After Report Reveals Details of SNC-Lavalin’s Illegal Donations.” National Post, April 30. https://nationalpost.com/news/politics/liberals-accused-of-cover-up-after-report-reveals-details-of-snc-lavalins-illegal-donations.

- Tello, Edward, James Hazelton, and Shane Vincent Leong. 2019. “Australian Corporate Political Donation Disclosures: Frequency, Quality, and Characteristics Associated with Disclosing Companies.” Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 32 (2): 581–611. doi:10.1108/AAAJ-04-2016-2515.

- Tham, Joo-Cheong. 2010. “Regulating Political Contributions: Another View from Across the Tasman.” Policy Quarterly 6 (3): 26–30. doi:10.26686/pq.v6i3.4337.

- Tham, Joo-Cheong, and Sally Young. 2006. Political Finance in Australia: A Skewed and Secret System. Canberra: Democratic Audit of Australia.

- Throsby, David, and Glen Withers. 1979. The Economics of the Performing Arts. Melbourne: Edward Arnold Australia Ltd.

- Wesley, Jared, and Lisa Young. 2022. “Albertans’ Views about Money in Politics.” https://www.commongroundpolitics.ca/albertans-views-abut-money-in-politics.

- Wike, Richard, and Alexandra Castillo. 2018. Many Around the World are Disengaged from Politics: But Could be Motivated to Participate on Issues Like Health Care, Poverty and Education.. Washington, DC: Pew Research Centre.

- Witko, Christopher. 2011. “Campaign Contributions, Access, and Government Contracting.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 21 (4): 761–778. doi:10.1093/jopart/mur005.

- Wood, Danielle, Kate Griffiths, and Carmela Chievers. 2018. Who’s in the Room? Access and Influence in Australian Politics. Melbourne: Grattan Institute.

- Young, Lisa. 1998. “Party, State and Political Competition in Canada: The Cartel Model Reconsidered.” Canadian Journal of Political Science 31 (2): 339–358. doi:10.1017/S000842390001982X.

- Young, Lisa. 2012. “Regulating Political Finance in Canada: Contributions to Democracy?” In Imperfect Democracies: The Democratic Deficit in Canada and the United States, edited by Patti Tamara Lenard, and Richard Simeon, 138–160. Vancouver: UBC Press.