ABSTRACT

Over the past decade the problem of wage theft has burst onto the Australian policymaking scene, seemingly out of nowhere. Its meteoric rise, from a largely unrecognised issue to the broad public agenda, then onto the narrower governmental and decision agendas of state and federal governments, was a major feat in policy advocacy. It stands as a particularly outstanding example of the power of framing to change the salience and esteem of an issue. By tracing the journey of the wage theft issue through the different spheres of public and governmental attention, this research illuminates under-studied aspects of the re-framing and agenda-setting artforms and advances the study of advocacy group interventions in policy conflicts.

Introduction

Framing has incredible power to alter political reality. Scholars of public policymaking have long understood that framing can make the difference between a problem being seen or remaining invisible; being high or low on the policy agenda; becoming subject of reform or being side-lined (Birkland Citation2007; Rein and Schön Citation1993; Rochefort and Cobb Citation1994). Since the argumentative turn in policy studies, the discursive dimension of policymaking has been a major area of scholarship, with framing a key concept to understand the impact of language on policy. Many aspects of policy framing have been thoroughly explored – we know framing can transform an issue’s salience, and the policy response deemed legitimate, and that sometimes issues can be strategically re-framed (Fawcett et al. Citation2019). We know less about the strategic use of framing by non-government actors, and in particular, we have had only sporadic work tracking reframing ‘campaigns’ by advocacy groups (De Bruycker Citation2017). As a result, the questions of how these players advance an alternative frame, and what ‘work’ that frame does to produce policy change, have only tentative answers.

This research advances the project of investigating advocacy group reframing by looking at one illuminating case-study: the battle over wage theft regulation in Australia. Over the last decade, so-called wage theft – the non-payment of minimum entitlements – has burst onto the Australian policy scene. Its elevation up the agenda by labour activists, and their extraction of significant reform, including from very resistant governments, has been a significant feat of advocacy. Framing played a major role in that campaign: the very term ‘wage theft’ was a key point of contestation between advocates and defenders of the status quo (Teicher Citation2020, 50). By charting the rise and contestation of wage theft, this research deepens our understanding of advocacy groups and the role framing plays in their policy interventions. We shed new light on the effects a frame has on a policy conflict, including previously underexplored organisational and rhetorical effects. This case study renders more clearly the evolving strategies and practices of policy advocacy in Australia, in particular the advocacy efforts of Australian unions, and gives scholars of policy conflict – in Australian and internationally – new concepts to understand framing dynamics in their own jurisdictions.

Agenda dynamics & framing in policy theory

The concept of framing cuts across many scholarly literatures, and even within policy studies can be approached from a range of starting points (Bacchi and Goodwin Citation2016, 57–61; Barbehön, Münch, and Lamping Citation2015, 246). In this work we are most interested in framing as it affects the policy agenda, and so we start from the theory around agenda setting, before examining the role of framing. The key insight of agenda-setting research is that, because policymakers’ attention is severely limited, they are forced to choose between problems to focus on (Birkland Citation2007; Jones and Baumgartner Citation2005; Kingdon Citation1984). This prioritisation is not a straightforwardly ‘rational’ calculus: politics frequently intervenes. Advocates (within or outside government) can agitate, sometimes forcefully, to get priority status for their issue, resulting in fierce issue competition (Birkland Citation2007). In their efforts to analyse these battles, scholars have identified three distinct layers of agenda being contested. In Pralle’s (Citation2009) formulation, the public agenda is the broadest: issues discussed by the public, often via the media. The governmental agenda – issues receiving attention from state institutions – is considerably more limited and elite. Narrower still is the decision agenda: issues up for active decision by senior policymakers: legislation requiring a vote; items before cabinet; cases requiring determination by the regulator. Each of these agendas has a different set of limits, access points, opportunities, and power-balances. They are often linked: building support in one can help achieve access to the next. But they can also fall out of alignment: sometimes cabinet decide on issues no longer as pertinent for the public, or sometimes items are de-prioritised on the decision agenda, despite their continued importance within other spheres (Pralle Citation2009). It is, in other words, a multi-levelled maze that an issue must navigate to go from ‘non-problem’ to subject of reform.

Scholarship on agenda setting shows governments invest great time and effort into establishing and protecting their agendas (Howlett and Shivakoti Citation2014). They are, however, frequently beset by events and crises that forcibly shift their attention, and the efforts of non-government actors to achieve the same. The role of those actors – advocacy groups, social movements, etc. – has been a growing focus of agenda-setting research over the last decade (Chaqués Bonafont Citation2016; Dür and Mateo Citation2014). Work at the intersection of policy and interest-group studies has attempted to understand how these players can seize the agenda, the strategies they employ, and the extent to which their agency is constrained by institutional and broader political contexts (Grömping and Halpin Citation2021; Lisi and Loureiro Citation2022; Varone et al. Citation2018).

Much attention has been given to the framing strategies these groups employ – that is, the language advocates use to describe their issue (e.g. Boscarino Citation2016; Jensen and Seeberg Citation2019; Yordy et al. Citation2019). A key idea since the argumentative turn in policy studies, the concept of framing rests on the notion that policy problems have to be discursively constructed, and can be constructed in a variety of ways, as policy issues are open to a range of descriptions, each with divergent understandings of cause and remedy (Rein and Schön Citation1993). Sometimes one framing of an issue will be broadly hegemonic for the players active in that policy space – a situation Laws and Rein (Citation2003, 174) describe as ‘frame dominance’. Or issues may lack a dominant frame; there may be a situation of ‘frame pluralism’, where multiple frames jostle for dominance (Laws and Rein Citation2003, 174). And issues may move from one state to another; frames can be contested (see Fawcett et al. Citation2019); issues can be reframed. We examine the battle over wage theft as a case-study in reframing.

There are divergent approaches to the study of reframing. Some conceive of reframing in normative terms – as a virtuous ability to reflect upon framing and be open to an alternative frame; something that can assist in resolving intractable policy disputes (Rein and Schön Citation1993; for a critique see Bacchi and Goodwin Citation2016, 60). But there is a more analytical approach to reframing, viewing the process in terms of policy conflict combatants using frames as discursive weapons in attempts to shift the policy status-quo – that is, not to amicably resolve the conflict at all, but as armaments to further and win it. We find this approach in the work of Baumgartner and Jones (Citation1996) (in the guise of policy ‘image’ rather than ‘frame’) and Sarah Pralle (Citation2006); but also in the social movement literature on framing, and aspects of it in the advocacy coalition literature (Dodge Citation2017, 892–893). Despite this, investigations into the strategic use of framing by non-government actors are underdeveloped (see De Bruycker Citation2017, 780). One of the key outstanding questions according to De Bruycker (Citation2017, 780) is around whether advocacy groups can, through strategic framing, ‘punch above their weight’ and affect how an issue is understood not only by the group’s members, but by all the players on the policy scene, and in so doing, drive reform forward. Our case study engages directly with this question, examining how the reframing of wage theft helped catapult it up to the decision agenda, resulting in a significant change to an entrenched policy status-quo.

Method of study

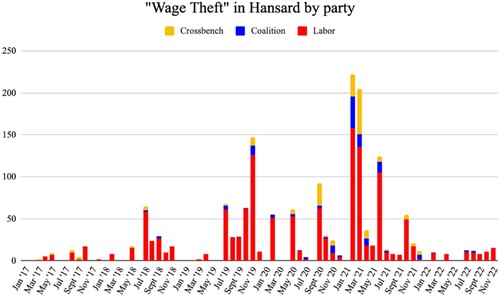

We employed a variety of methods to follow the progress of wage theft through the various levels of the policy agenda. First, using Factiva, we followed the debate through the Australian media, as a proxy for its salience on the public agenda. We ran a count of mentions of ‘wage theft’ in the nation’s major newspapers: The Age, the Sydney Morning Herald, The Australian and the Australian Financial Review (see ).

Figure 1. Mentions of ‘wage theft’ in major papers. (Monthly factive aggregates: The Age, Sydney Morning Herald, The Australian, Australian Financial Review.)

We were surprised to find that the phrase was entirely unused before 2015. This of course does not mean the problem later described as wage theft did not exist before this time. In fact, non-compliance with legally mandated wage entitlements is as old as the laws themselves.Footnote1 It has long been a concern of unions, and of workplace regulators – including in the decade leading up to 2015.Footnote2 However it is clear that it was not an issue high on the public, governmental or decision agendas – in need of special attention and reform – until that year.Footnote3 Rather, it was a low-salience issue, conceived as a problem the regulator had in hand; an area of routine enforcement; not an out-of-control problem. We argue this is because of how the issue was framed prior to 2015 – that is, in terms of underpayment. We ran searches for various phrases related to this framing – ‘underpayments’; ‘unpaid wages’ – to check if this revealed a lively debate prior to the coinage of ‘wage theft’ in 2015. We sifted through the data for uses to mean the same problem as described by ‘wage theft’. We found such usage was infrequent,Footnote4 and primarily described isolated incidents, dealt with via the bureaucratic mechanisms of the Fair Work Ombudsman. It was rarely if ever conceived of as a systemic problem affecting whole industries,Footnote5 and the emphasis, in the reports of the Ombudsman especially, was on the (allegedly) overwhelmingly accidental nature of the problem.Footnote6 therefore illustrates two things: (1) increasing adoption of the wage theft frame; (2) increasing attention on the issue itself.

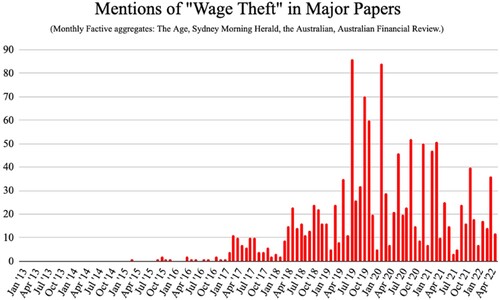

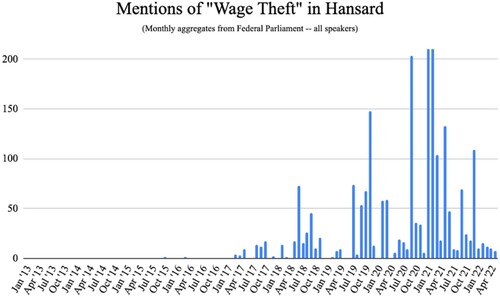

To follow this reframing and agenda-setting process into the governmental agenda, we tracked usage of ‘wage theft’ in the Federal Parliament Hansard from 2015 to 2022 – see and . Again, we checked for other terms, to see if this revealed a different pattern of attention on the underlying issue, but again found little deviation.Footnote7

Figure 2. Mentions of ‘wage theft’ in Hansard. (Monthly aggregates from Federal Parliament – all speakers.)

Based on these charts we identified four phases in the development of the wage theft debate: (1) the coinage of wage theft, in mid-2015; (2) its arrival as a consistent (but not always hot) issue on the public agenda; (3) its period of intense attention in the public and governmental agendas, with the wage theft frame ascendant; (4) the period of adopting reform on the decision agenda. We then sought to understand the story of how and why it moved through these phases by qualitatively tracking the development of the debate in the press and parliament through newspaper articles, parliamentary transcripts, and inquiry committee reports.

Phase 1: The coinage of wage theft

We can see that the issue of ‘wage theft’, so-framed, was literally non-existent before 2015 – a surprising finding to us. The question is: what changed in 2015? We have found the catalyst to be an episode of the ABC’s Four Corners program, featuring an investigation into migrant worker exploitation in convenience chain 7-Eleven. The program documented voluminous breaches of labour standards, with staff working well over the hours cap attached to their visas, for rates well below the minimum wage. The scandal provoked a significant outcry. The Government of the day, the Liberal-National Coalition, assured the public that the problem – of ‘underpayments’ – was something the Ombudsman could deal with through the normal mechanisms (Ferguson, Danckert, and Lee Citation2015). But journalists and commentators conceived of the problem as something larger and more systematic than mere ‘underpayments’. Four Corners dubbed the problem wage ‘fraud’ or wage ‘scams’, while Stephen Clibborn, industrial relations scholar at the University of Sydney, penned an op-ed in the Fairfax papers which introduced the phrase ‘wage theft’ to the Australian lexicon, describing the practice as systemic in certain industries (Clibborn Citation2015). Several months later, the term arrived in the Parliament, with Labor Whip, Joanne Ryan, quoting a constituent saying they ‘[did] not want our economy to be based on wage theft’ (House of Representatives Citation2015, 10985).

This ‘theft’ framing did not take immediately – as and show. Rather, the underlying issue entered a phase of frame pluralism. The wage theft frame was a marginal one, out at a radical edge of the debate at this point. However, the hegemony of ‘underpayments’ was clearly under strain: the arrival of ‘wage theft’ at this time was symptomatic of a broader concern that the 7-Eleven scandal was something different to the accidental, isolated problem of ‘underpayments’. And this spurred new attention on the issue on the governmental agenda: Senate inquiries and a special ministerial working group were set up to investigate (Education & Employment References Committee Citation2016a, 3; Ferguson, Danckert, and Lee Citation2015). In these forums, there was a battle around the scope and nature of the problem.Footnote8 ‘Wage theft’ did not rate a mention in those deliberations (see Education & Employment References Committee Citation2016b). Instead, a consensus emerged that, while not exactly systemic underpayments were a serious hazard afflicting franchises, and particularly franchises with largely migrant workforces. If there was any deliberate exploitation occurring, it was likely to be a few bad apples operating at a distance from franchise ‘head office’; not a business model. This constrictive framing of the problem allowed the government to keep its response to the issue relatively narrow. Before the 2016 election, the Coalition announced its crackdown if re-elected: new and larger fines for ‘intentional and systematic’ worker exploitation, increased liability for franchise head offices complicit in wage theft, extra investigatory powers for the Ombudsman, an expert taskforce to provide recommendations for reform, and more money for the Fair Work Ombudsman (Nutt Citation2016).Footnote9 After narrowly winning re-election, the government began drafting legislation for these changes (Field Citation2016). But by the time its Bill was presented to Parliament – in March 2017 – the issue had mutated into something larger. The limited problem affecting migrant workers in some franchises had become widespread, mainstream, ‘endemic’ (‘High time workers get better protection’, Citation2017).

Phase 2: wage theft gains an agenda beachhead

From 2017 we see the issue of wage theft as a more solid item on the public and governmental agendas. The major driver appears to have been a slew of journalistic investigations which helped expand the breadth of the problem. In May 2016, a Fairfax investigation found McDonalds had underpaid workers by tens of millions of dollars a year due to substandard wage deals with the Shop, Distributive and Allied Employees Association (Schneiders, Toscano, and Millar Citation2016a). Journalists uncovered further widespread underpayment at Woolworths, Hungry Jacks and KFC in late August (Schneiders, Toscano, and Millar Citation2016b); and at Caltex, Chemist Warehouse and the fruit picking industry in November (Baker and McKenzie Citation2016; Christodoulou and Ferguson Citation2016; Schneiders and Millar Citation2016). The scandals continued apace in the new year (see Christodoulou and Ferguson Citation2017; Toscano and Danckert Citation2017), with Senate inquiries into workplace relations mushrooming in response.

This wave of scandals established an atmosphere of crisis, with journalists and unions calling for urgent reform, and increasingly referring to the issue in the more dramatic ‘theft’ frame (ACTU Citation2016; Ferguson Citation2017a; Morey Citation2017). To quell the rising furore, the Government finally introduced its Fair Work Amendment (Protecting Vulnerable Workers) Bill 2017, giving effect to the promised crackdown from the election (Marin-Guzman Citation2017). Voting on the Bill, however, was delayed, partly due to lobbying by employer groups seeking less onerous reform (Ferguson Citation2017b; Gartrell Citation2017a; Citation2017b). In April, the reforms were quietly removed from the parliamentary program without explanation and did not reappear until August (Ferguson Citation2017c; Gartrell Citation2017b). The issue was successfully pushed off the decision agenda – for a time.

Meanwhile, employers were also seeking to push back on the rhetorical front. In October 2016 the Senate established an inquiry into non-compliance with the Fair Work Act. In public submissions and hearings, held concurrently with the introduction of the Government’s crackdown, unions attested to rampant, widespread ‘wage theft’, beyond franchises dominated by migrant workers (Australasian Meat Industry Employees’ Union Citation2016; Education & Employment References Committee Citation2017, 23). Employer groups, by contrast, rejected the very concept, claiming underpayments were a rare and accidental phenomenon, better understood as ‘non-compliance’. The same arguments were made in inquiries in Western Australia, Queensland and Victoria (AI Group Citation2020, 6; Education, Employment and Small Business Committee Citation2018, 21; Government of Western Australia Citation2019, 17). A press release by the Australian Industry Group in response to Queensland’s inquiry into wage theft is emblematic: it condemned what it called an investigation ‘into a loaded buzz-term like “wage theft”’, claiming the term ‘theft’ was ‘misleading, inappropriate and [had] the potential to unfairly brand every failure to correctly calculate an employee's pay as criminal’ (AI Group Citation2018). Similarly, Dick Grozier of the Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry told a Senate hearing he did ‘not accept the view that underpayment of wages is wage theft’ or ‘the policy implications of that name’ (Economics Legislation Committee Citation2018, 5). Coalition MPs were equally reluctant to use the term. Except when trying to re-define the term to apply to union malfeasance, the Coalition barely said ‘wage theft’ in parliament until 2021 – as (above) shows. However, this attempt at conceptual containment was undermined by the steady flow of new scandals; scandals which, by 2019, catapulted the issue right up to the top of the public and governmental agendas.

Phase 3: ‘wage theft’ frame hegemony

Our two charts go through a step-change in 2019. Usage of ‘wage theft’ rises sharply, but also becomes quite erratic. We argue one key event was the main cause of this new phase in the debate, and that was the wage theft scandal concerning celebrity chef, George Calombaris. In April 2017 – while the government’s franchise crackdown was stalled in the House – it emerged that Calombaris’ MAdE Establishment restaurant conglomerate had underpaid staff a total of $2.6 million (Thompson and Evans Citation2017). After an Ombudsman’s investigation and external audit, MAdE repaid the wages, with Calombaris claiming it was the product of ‘poor practice classifying workers’ and mistakes (Thompson and Evans Citation2017). Subsequent claims by MAdE employees of unpaid overtime being routine spurred the Ombudsman to investigate further. The second probe concluded in July 2019 that employees had been underpaid $7.8 million – triple the original total (Houston and Hawthorne Citation2017; Otter Citation2020). This scandal was the subject of what The Australian dubbed a media ‘firestorm’ (Stensholt and Hannah Citation2019). A TV celebrity known nation-wide, Calombaris provided a unique focal point for growing media coverage of ‘wage theft’. Indeed, use of the term spiked in the scandal’s wake: in the month before the second MAdE scandal – June 2019 – major Australian papers published just 17 articles using the ‘theft’ frame.Footnote10 July saw 102, with a third explicitly referring to Calombaris. The story led prime-time TV-news and radio, while Calombaris’ name echoed in the federal parliament over a dozen times in late 2019 (Chung Citation2019; House of Representatives Citation2019a, 874–875; Varga Citation2019).

Either side of the Calombaris scandal were others at high-profile restaurants (Brenner and Robinson Citation2020), as well as major supermarkets, banks, and later, universities (including the authors’ own institutions) (Economics References Committee Citation2022; Khadem Citation2019; NTEU Citation2023; Schneiders Citation2022). But the 2019 ‘Calombaris moment’ appears to have been key in terms of the Coalition government’s thinking on the issue. Before Calombaris, the Coalition was reluctantly considering major penalties for wage theft, avoiding legislating and dodging the language of ‘wage theft’. Afterwards, the government accepted that framing. We argue this is the point of successful reframing of the issue – the point at which even those most hostile to the frame found they had to adopt it. And by adopting it, the Coalition made it all but impossible to avoid criminalisation as their policy response.

On the decision agenda

Five days after the Calombaris scandal broke, the Coalition announced it would draft laws to criminalise wage theft. This was not totally unforeseen: prior to the 2019 election, the Coalition gave ‘in-principal’ support to all recommendations of its Migrant Worker Taskforce, including criminal penalties for the most aggravated cases of wage theft (Australian Government Citation2019; Clibborn Citation2020). But after the 2019 election, the Coalition’s focus swiftly returned to tougher regulation of unions, not employers: the government’s first industrial relations bills after the election aimed at criminal penalties for union malfeasance (Porter Citation2019). The Calombaris affair, breaking days into the first session of the new parliament, helped to not only catapult wage theft back to the top of the governmental agenda – ‘in-principle’ support for action had to become urgent action – but forced the theft frame on them too. Christian Porter, the Industrial Relations Minister, used the term tentatively at first, telling parliament ‘our government has a zero tolerance for this sort of behaviour, whether that is underpayment or wage theft’ (House of Representatives Citation2019a, 876, emphasis added) but by October 2019 he was sounding a full convert, telling the media ‘[there’s] got to be a criminal penalty for the most serious types of wage theft […] these companies aren’t getting the message and the deterrence has to be greater’ (Hannan Citation2019). While there was wrangling over the threshold for criminalisation – the Coalition sought to criminalise only the most egregious, systematic forms; labour activists called for lower bars – the question was not if wage theft would be criminisalised but how. After haggling over details between September 2019 and December 2020, the Government presented a bill to parliament that included, for the first time, criminal penalties for wage theft (House of Representatives Citation2020, cxvi).

The gravity of this moment should not be underestimated. Criminalisation would alter, to an extent, the fundamentals of the Fair Work regime – a deeply entrenched policy paradigm for industrial relations in Australia (see Stanford, Hardy, and Stewart Citation2018; Teicher Citation2020). Even the Labor Party was initially reluctant: in June 2017 Labor’s federal workplace relations spokesman, Brendan O’Connor, said ‘Labor understands why there are calls to increase penalties against rogue employers [who] exploit their workers but would be wary of criminalising industrial relations matters’ (Hannan Citation2017). But as the ‘theft’ frame caught on, labour activists and Labor parties slowly gravitated towards criminalisation as a policy demand. The first such call, publicly, was from then-Transport Workers Union secretary Tony Sheldon, who told ABC radio in May 2017: ‘if you were to steal out of the till, you would go to jail … ’

… But [employers] have stolen millions of dollars of payments to their own employees. They see it as part of their own corporate strategy on how to minimise payment while maximising their own profit – and that's theft. (Iggulden Citation2017)

The Coalition’s attempt to legislate federal wage theft laws failed in 2021. The Bill’s other, more controversial and pro-employer provisions, saw the Senate crossbench remove many sections; the Coalition, robbed of its ‘balancing’ pro-employer provisions, in turn cut wage theft criminalisation from the package (Marin-Guzman Citation2021; Munton et al. Citation2021). But the issue did not die with the Bill. It retained a place on the public and governmental agendas, even throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, all the way through to the 2022 federal election, with Labor committing in 2021 to criminalisation if elected (Albanese and Burke Citation2021). In September 2023, the subsequently elected Albanese Government introduced the wage theft criminalisation within its ‘Closing Loopholes’ bill. Though it had a somewhat tortured journey through the Senate, criminalisation of intentional wage theft finally navigated the decision agenda in December 2023, with a maximum penalty of ten years’ jail for wage theft offences passed into law.Footnote12

Discussion

What do we learn from the wage theft story about the art of framing and policy advocacy? We have many observations to take out of this case study – more than we can fit in one paper. Here, we focus here on what we believe to be two under-studied aspects of framing/agenda-setting dynamics. First are several effects we file under the heading of the organising impact of a frame. By this, we mean how the theft frame activated, channelled, or reconfigured collective action.Footnote13 One such organising effect was on the media. Wage theft slowly emerged as an issue thanks primarily to journalistic investigations: an example of the importance of the media in mobilising policy bandwagons (see Baumgartner and Leech Citation2001; Halpin Citation2011). After Adele Ferguson’s 7-Eleven exposé, more newsrooms put top investigators on what became a kind of wage theft ‘beat’, resulting in new scandals. Even in the early days, before fully adopting the ‘theft’ phrase, most of these stories employed the theft narrative: they identified victims to empathise with, and villainous bosses to revile (indeed, allies of these ‘villains’ complained about exactly this – see Valent Citation2019; Willox Citation2020). Increasingly they did adopt the actual phrase, and as they did, the media bandwagoning grew more intense. The frame helped drive this attention because, compared to subject-less, emotion-less ‘underpayment’, it had high drama, and rendered complex workplace conflicts as digestible, sensational stories. So the effect of the new narrative and frame did much to reorganise media work and attention.

Next was an impact on labour movement activism. Once wage theft grew as an issue in the media, union activists found a straightforward and emotionally powerful phrase to capture a whole spectrum of workplace exploitation. It allowed workers suffering a range of mistreatments – misclassification, unpaid overtime, non-payment of penalty rates, and more – to use a single umbrella term to describe a common plight, creating new opportunities for collective identification and action. What’s more, wage theft tended to be concentrated in industries unions had previously struggled to penetrate. The rise of wage theft was accompanied by a burst of recruitment, industrial action and labour activism through the courts – in retail and fast-food sectors; hospitality; farms and among casual academics (see Schneiders Citation2022). The impact was so profound that whole new organisations were formed around these efforts: RAFFWU and HospoVoice; casuals networks at universities, all of which were important in pushing the issue further and changing the industrial power-balance in their sectors.

Finally, wage theft as an issue helped to organise the labour movement’s – and particularly the Labor Party’s – efforts to battle the Coalition’s anti-union rhetoric and policies. When the Coalition brought forward bills for its union-targeting Registered Organisations Commission, and tough penalties for union malfeasance, Labor MPs, including then-Opposition Leader Anthony Albanese, would routinely steer debate towards ‘wage theft’, asking why workers and their unions were being targeted as criminals, while employers were seemingly let off lightly (House of Representatives Citation2019b, 1554). Union officials did the same (see Croucher Citation2017). Without wage theft scandals to organise around, it is difficult to say if Labor would have found an adequate defence for voting against crackdowns on union malfeasance. Going the other direction, it also seems plausible that the Coalition’s attempts to crack down on unions inadvertently helped to elevate wage theft as an issue: it was Labor’s go-to defence; it might not have come up so much if Labor did not wield it defensively.

This takes us into a dimension of agenda-setting that has not been thoroughly explored: the ways in which agenda-items interact with one another. The standard conception of agenda-setting views issues as isolated competitors, jostling for position on the agenda but not influencing each other directly (Vos, Schoemaker, and Liisa Luoma-aho Citation2014, 209). Here, we have two ostensibly separate issue-debates – (1) wage theft; (2) union malfeasance – affecting one another; something we might call issue synchronicity. Wage theft appearing on the agenda at the same time as the union malfeasance crackdown is an issue fought differently than if it arrived without the crackdown to respond to – and vice versa. We cannot know if wage theft would have risen slower or quicker or at all without the union crackdown – we just know that it would have been argued for differently and could have easily ended somewhere other than criminalisation. Wage theft criminalisation was in major part legitimised by the proposed criminalisation of union malfeasance – without that tit, there would have been no wage-theft-criminalisation tat. The lesson is that items can interact, sometimes in ways that have major effects on policy outcomes: a dynamic worthy of further study.

Conclusions

The story of wage theft in Australia demonstrates the remarkable power of framing in deciding the fate of a policy conflict. The problem known as ‘underpayments’ was a low-salience issue, capturing very little public attention, and limited, bureaucratic attention in the governmental sphere. The problem was overwhelmingly considered an isolated one; the product of oversight rather than intention; something that could be handled through the standard mechanisms of the Ombudsman’s office. Reframed as ‘wage theft’, the same issue became a ‘media firestorm’, and a major, seemingly new policy problem, requiring fresh attention from legislators and the political executive. The new frame provoked considerable change in the activities of a wide range of players: the media, the labour movement, business groups, parliamentary parties, regulators and ministers; it both mobilised players (on both sides of the issue) and re-organised their collective action in various ways. As the new frame became hegemonic, criminalisation – a policy response once considered beyond the pale for both Labor and the Coalition, and undiscussed by unions publicly – became the logical, even the ‘moral’ response, resulting in a considerable change in the Australian government’s long-entrenched mode of industrial regulation through non-criminal mechanisms. It was very clearly a case of policy advocates – academics and unionists – ‘punching above their weight’, affecting the whole policy subsystem, and dramatically, through their change in language.

Our analysis of their reframing efforts helps us understand how this happened: in part, through the practical ‘work’ done by the frame to re-organise the resources and activity of a range of players on the policy scene – what we are calling the frame’s ‘organisational effects’; and in part through the dynamic interaction of the re-framed issue with other agenda items – ‘issue synchronicity’. Such insights will be of value to a range of other scholars. For those studying other cases of policy conflict, this study highlights important dimensions in need of investigation: (1) the ways in which issue framing affects the organisation of the media, advocacy groups, legislators and the executive – the discursive-organisational interface; (2) the ways in which an issue is affected by other issues on the agenda at the same time; the inter-issue interface. Or, for scholars of interest groups and policy advocacy, this study engages with the project outlined by De Bruycker (Citation2017), helping reveal some of the strategic considerations confronting advocates on any issue: considerations around what else is on the agenda and how that might interact with their own issue; around how a frame might not only alter perspectives of policymakers, but facilitate new forms of participation and attention from a range of actors on the policy scene. While some of these ideas are hardly new to the study of framing (see esp. Pralle Citation2006), conceiving of them as part of the strategic puzzle facing advocates, and investigating the strategic choices advocates make about them, highlights the importance of reframing by non-government actors, a group less thoroughly explored within the agenda-setting literature. This advocacy view of framing also offers opportunities for further research into reframing campaigns and the potential organising effects of reframing for mobilisation and recruitment through qualitative in-depth interviews with labour movement policy advocates – a project we hope to move to next.

Acknowledgements

We thank our peer reviewers for their time and their feedback, which has helped us improve this article greatly.

Disclosure statement

None of the authors have any direct conflicts of interest, though we have all worked at universities subject to wage theft, and have at various times been members of unions that campaigned on the issue.

Data availability statement

Happy to share our spreadsheets!

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

James C. Murphy

James C. Murphy is lecturer in Australian Politics at the University of Melbourne and studies state politics and Australian policy advocacy.

Katie Lovelock

Katie Lovelock teaches and researchers Australian politics and public policy at the University of Melbourne.

Emily Foley

Emily Foley, newly Dr Foley, studies Australian politics, especially the contemporary Australian Labor Party.

Notes

1 In March 1897, months after introduction of one of the world’s first broad-based minimum wages, the Age reported the submission by the Trades Hall Council to Victoria’s Premier of ‘a series of complaints with reference to evasions of the minimum wage clause in Government contracts’ (‘The minimum wage: numerous evasions alleged’ Citation1897).

2 From 2011 to 2013 the FWO ran a major audit of restaurants in Canberra. They found 105 of 179 audited businesses in breach of the Fair Work Act, with 68% of breachers not paying correct wages (Fair Work Ombudsman Citation2013, 29).

3 We could find only one reform proposal since 2000: a 2004 push by Labor in Opposition to create a $40m government fund to compensate victims of underpayment (Contractor and Brown Citation2004).

4 An example: the biggest year for articles mentioning ‘underpayment’ and ‘wages’ between 2000 and 2015 was 2006: 22 hits, mostly regarding exploitation of migrant workers. In 2015 things escalated: 104 hits. 2016 had 195 hits, 2017: 202; 2018: 204; 2019: 469. So coverage of ‘underpayment’ exploded with ‘wage theft’.

5 Some exceptions: a few news reports about systemic underpayment in the hospitality sector; media investigations into systemic exploitation of textile outworkers (Field Citation2001; Munro Citation2003); one union report about industry-wide underpayment in the cleaning sector. These reports, however, did not drive major spikes in media or parliamentary attention, we argue because the framing was not conducive to such attention.

6 For example Fair Work Ombudsman (Citation2011, 3–4).

7 In Hansard, from January 2011 (when fully searchable records begin) to December 2014 there were 129 hits for ‘underpayment’ and ‘wages’. In September 2015 alone there were 111.

8 At these hearings, Senators (Government and Opposition) and witnesses (7-Eleven management, employees, and union officials) talk about ‘wage fraud’, ‘visa fraud’, ‘underpayments’ and, from an SDA official, ‘non-observance of conditions’ (as if it were a matter of religious conscience) (21). See Education and Employment References Committee (Citation2016b).

9 The Government pledged $20 million in extra funding over four years for the Ombudsman – though this came after cutting the agency’s funding by $16.4 million a fortnight earlier (see Karp Citation2016; compare Department of Employment Citation2016, 125), and the money would eventually be part-diverted to the government’s new agency for policing trade union governance, the Registered Organisations Commission (Patty Citation2018).

10 Based on Factiva search for ‘wage theft’ or (‘wage’ and ‘theft’), covering The Australian, The Age, Herald Sun, Sydney Morning Herald, and the Australian Financial Review.

11 While it eschewed criminalisation, the NSW Coalition Government did seek tougher penalties for wage theft (Bonyhady Citation2021).

12 The Albanese government’s wage theft legislation have raised concerns regarding the extent to which it will override or weaken existing state wage theft laws – see Allen (Citation2023), RMIT ABC Fact Check (Citation2023).

13 Ferris and Ross (Citation2022) argue the rhetorical criminalisation of the behaviour individualises the ‘thieves’ as isolated deviants, instead of part of an oppressive class, or subjects of an oppressive ideology. While this view has some merits, it discounts the organisational and mobilising effects of the frame that allows for growing solidarity, even ‘class consciousness’. Moreover, the elements of the frame that are individualising are, we think, helpful for the issue’s elevation up the agenda through creating a digestible story that can act as a focal point.

References

- AI Group. 2018. “‘Wage Theft’ Inquiry Headed into Dangerous Ground.” Media Release, August 10. https://web.archive.org/web/20200806221208/https:/www.aigroup.com.au/policy-and-research/mediacentre/releases/wage-theft-inquiry-14Aug/.

- AI Group. 2020. “Submission on Victorian Wage Theft Bill 2020.” March 9. https://cdn.aigroup.com.au/Submissions/Workplace_Relations/2020/Consultation_Paper_Victorian_Wage_Theft_Bill_march_2020.pdf.

- Albanese, Anthony, and Tony Burke. 2021. “Labor Will Criminalise Wage Theft.” Media Release, May 13. https://anthonyalbanese.com.au/media-centre/labor-will-criminalise-wage-theft-13-may-2021.

- Allen, Jacinta. 2023. Commonwealth Follows Victoria’s Lead on Wage Theft. Premier of Victoria. Accessed March 4, 2024. http://www.premier.vic.gov.au/commonwealth-follows-victorias-lead-wage-theft.

- Andrews, Daniel. 2018. “Dodgy Employers to Face Jail for Wage Theft.” Media Release. http://www.premier.vic.gov.au/dodgy-employers-face-jail-wage-theft.

- Australasian Meat Industry Employees’ Union. 2016. Submissions of the AMIEU QLD Branch to the Inquiry into Corporate Avoidance of the Fair Work Act 2009. Senate Committee on Education & Employment.

- Australian Council of Trade Unions. 2016. Systemic Underpayment of Workers Shows System is Broken. Media Release, December 9. https://web.archive.org.au/awa/20210413130913mp_/https:/www.actu.org.au/media/1033005/actu-release-161209-underpayment.pdf.

- Australian Government. 2019. Australian Government Response: Report of the Migrant Workers’ Taskforce. Australian Government.

- Bacchi, Carol, and Susan Goodwin. 2016. Poststructural Policy Analysis: A Guide to Practice. New York: Springer.

- Baker, Richard, and Nick McKenzie. 2016. “Bitter Harvest: The Gangs Exploiting Illegal Farm Workers.” Sydney Morning Herald, November 15: 1.

- Barbehön, Marlon, Sybille Münch, and Wolfram Lamping. 2015. “Problem Definition and Agenda-Setting in Critical Perspective.” In Handbook of Critical Policy Studies, edited by Frank Fischer, Douglas Torgerson, Anna Durnová, and Michael Orsini, 241–258. Edward Elgar.

- Baumgartner, Frank R., and Bryan D. Jones. 1996. Agendas and Instability in American Politics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Baumgartner, Frank R., and Beth L. Leech. 2001. “Interest Niches and Policy Bandwagons: Patterns of Interest Group Involvement in National Politics.” The Journal of Politics 63 (4): 1191–1213. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-3816.00106.

- Birkland, Thomas. 2007. “Agenda Setting in Public Policy.” In Handbook of Public Policy Analysis, edited by Frank Fischer and Gerald Miller, 63–78. Boca Raton, FL: Routledge.

- Bonyhady, Nick. 2021. “NSW to Introduce Tougher Tax Laws to Target Wage Theft.” The Sydney Morning Herald, April 13.

- Boscarino, Jessica. 2016. “Setting the Record Straight: Frame Contestation as an Advocacy Tactic.” Policy Studies Journal 44 (3): 280–308. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12121.

- Brenner, Mathew, and Richard Robinson. 2020. “All These Celebrity Restaurant Wage-Theft Scandals Point to an Industry Norm.” The Conversation, February 10. http://theconversation.com/all-these-celebrity-restaurant-wage-theft-scandals-point-to-an-industry-norm-131286.

- Chaqués Bonafont, Laura. 2016. “Interest Groups and Agenda Setting.” In Handbook of Public Policy Agenda Setting, edited by Nikolaos Zahariadis, 200–218. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Christodoulou, Mario, and Adele Ferguson. 2016. “Caltex Warned Station Owners of Coming Raids.” Sydney Morning Herald, November 3: 3.

- Christodoulou, Mario, and Adele Ferguson. 2017. “Investigation Uncovers Domino’s Pay Problems.” Sydney Morning Herald, February 11: 9.

- Chung, Frank. 2019. “Waitress Lashes MasterChef Judge.” News.com.au, July 19. https://www.news.com.au/finance/work/at-work/he-should-be-taken-off-masterchef-former-waitress-says-george-calombaris-still-owes-her-2000/news-story/04542dae75823a84367e50663f66d502.

- Clibborn, Stephen. 2015. “Visa Amnesty Needed for All Victims.” Canberra Times, September 9.

- Clibborn, Stephen. 2020. “Australian Industrial Relations in 2019: The Year Wage Theft Went Mainstream.” Journal of Industrial Relations 62 (3): 331–340. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022185620913889.

- Contractor, Aban, and Malcolm Brown. 2004. “Labor Pledges $40 m to Underpaid Workers.” Sydney Morning Herald, August 7: 4.

- Croucher, James. 2017. “Jail Bosses for ‘Wage Theft’.” The Australian, May 15. Accessed via Factiva.

- De Bruycker, Iskander. 2017. “Framing and Advocacy: A Research Agenda for Interest Group Studies.” Journal of European Public Policy 24 (5): 775–787. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2016.1149208.

- Department of Employment. 2016. Portfolio Budget Statements for the Fair Work Ombudsman. Department of Employment. Parliament of Australia. https://webarchive.nla.gov.au/awa/20210603125049/https:/www.dese.gov.au/about-us/resources/fair-work-ombudsman.

- Dodge, Jennifer. 2017. “Crowded Advocacy: Framing Dynamic in the Fracking Controversy in New York.” Voluntas 28 (3): 888–915. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-016-9800-6. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44668790.

- Dür, Andreas, and Gemma Mateo. 2014. “Public Opinion and Interest Group Influence: How Citizen Groups Derailed the Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement.” Journal of European Public Policy 21 (8): 1199–1217. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2014.900893.

- Economics Legislation Committee. 2018. Inquiry into Treasury Laws Amendment (2018 Superannuation Measures No. 1) Bill 2018. Hearing Transcript, June 12. https://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/download/committees/commsen/1c8de347-a6fc-4948-add3-0db958c393ca/toc_pdf/Economics Legislation Committee_2018_06_12_6211_Official.pdf;fileType = application%2Fpdf.

- Economics References Committee. 2022. Systemic, Sustained and Shameful. Unlawful Underpayment of Employees Remuneration. Commonwealth of Australia. https://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/download/committees/reportsen/024434/toc_pdf/Systemic,sustainedandshameful.pdf;fileType = application%2Fpdf.

- Education, Employment and Small Business Committee. 2018. A Fair Day’s Pay for a Fair Day’s Work? Exposing the True Cost of Wage Theft in Queensland. Report. Parliament of Queensland. https://www.parliament.qld.gov.au/Work-of-Committees/Committees/Committee-Details?cid = 183&id = 3257.

- Education & Employment References Committee. 2016a. A National Disgrace: The Exploitation of Temporary Work Visa Holders. Commonwealth of Australia. https://www.aph.gov.au/parliamentary_business/committees/senate/education_and_employment/temporary_work_visa/report.

- Education & Employment References Committee. 2016b. Inquiry into Australia’s Temporary Work Visa Program. Hearing Transcript, September 24. https://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/download/committees/commsen/d6f5909e-a9b2-4b68-8df4-47e49f91508b/toc_pdf/Education and Employment References Committee_2015_09_24_3826_Official.pdf;fileType = application%2Fpdf#search = "committees/commsen/d6f5909e-a9b2-4b68-8df4-47e49f91508b/0007.

- Education & Employment References Committee. 2017. Corporate Avoidance of the Fair Work Act 2009. Report. Commonwealth of Australia.

- Fair Work Ombudsman. 2011. Annual Report 2010–11. Fair Work Ombudsman. https://www.fairwork.gov.au/sites/default/files/2021-10/Fair-Work-Ombudsman-Annual-Report-2010-11.pdf.

- Fair Work Ombudsman. 2013. Annual Report 2012–13. Fair Work Ombudsman. https://www.fairwork.gov.au/sites/default/files/2021-10/Fair-Work-Ombudsman-Annual-Report-2012-13.pdf.

- Fawcett, Paul, Michael Jensen, Hedda Ransan-Cooper, and Sonya Duus. 2019. “Explaining the ‘Ebb and Flow’ of the Problem Stream: Frame Conflicts Over the Future of Coal Seam Gas (‘Fracking’) in Australia.” Journal of Public Policy 39 (3): 521–541. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X18000132.

- Ferguson, Adele. 2017a. “Wage Fraud: Pizza Hut Hit with Fines.” The Age, January 27. https://amp.smh.com.au/business/companies/wage-fraud-pizza-hut-hit-with-fines-20170127-gtzrbx.html.

- Ferguson, Adele. 2017b. “Billson Woos MP Mates on Franchises.” Australian Financial Review, July 10: 40.

- Ferguson, Adele. 2017c. “Workers Losing as Protection Law is Shelved. Sydney Morning Herald, April 7: 25.

- Ferguson, Adele, Sarah Danckert, and Jane Lee. 2015. “7-Eleven Founder Could Face Senate Grilling on Wage Abuse.” Australian Financial Review, September 2: 5.

- Ferris, Emma, and Stuart Ross. 2022. “Decaffeinated Resistance: Social Constructions of Wage Theft in Melbourne’s Hospitality Industry.” Journal of Criminology 56 (1): 42–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/26338076221115891.

- Field, Nina. 2001. “Action Urged on Outworker Conditions.” Australian Financial Review, November 23: 10.

- Field, Emma. 2016. “Protection for Foreign Workers.” Weekly Times, November 2: 15.

- Gartrell, Adam. 2017a. “Ex-Minister Lobbied for Franchisees.” The Age, April 7: 2.

- Gartrell, Adam. 2017b. “Turnbull Government’s Worker Exploitation Crackdown Delayed.” Sydney Morning Herald, June 20. https://amp.smh.com.au/politics/federal/turnbull-governments-worker-exploitation-crackdown-delayed-20170620-gwulij.html.

- Government of Western Australia. 2019. Inquiry into Wage Theft in Western Australia. Report. https://www.commerce.wa.gov.au/sites/default/files/atoms/files/report_of_the_inquiry_into_wage_theft_0.pdf.

- Grömping, Max, and Darren Halpin. 2021. “Do Think Tanks Generate Media Attention on Issues They Care About? Mediating Internal Expertise and Prevailing Government Agendas.” Policy Sciences 54 (4): 849–866. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-021-09434-2.

- Halpin, Darren. 2011. “Explaining Policy Bandwagons: Organized Interest Mobilization and Cascades of Attention.” Governance 24 (2): 205–230. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0491.2011.01522.x.

- Hannan, Ewin. 2017. “Labor Baulking at Union Calls for Bosses to be Jailed for Wage Theft.” The Australian, June 6.

- Hannan, Ewin. 2019. “Beyond Hopeless: Porter Slams Woolworths.” The Australian. October 31. Accessed via Factiva.

- “High Time Workers Get Better Protection.” 2017. The Age, January 3: 14.

- House of Representatives. 2015. Parliamentary Debates, October 13. 44th Parliament, Official Hansard, No. 15.

- House of Representatives. 2019a. Parliamentary Debates, July 24. 46th Parliament, Official Hansard, No. 1.

- House of Representatives. 2019b. Parliamentary Debates, July 31. 46th Parliament, Official Hansard, No. 1.

- House of Representatives. 2020. Fair Work Amendment (Supporting Australia’s Jobs and Economic Recovery) Bill 2020. Explanatory Memorandum. Parliament of Australia.

- Houston, Cameron, and Mark Hawthorne. 2017. Ex-staff speak out against Calombaris.Sydney Morning Herald, 10 April: 9

- Howlett, Michale, and Richa Shivakoti. 2014. “Agenda-Setting Tools: State-Driven Agenda Activity from Government Relations to Scenario Forecasting.” Paper Presented to European Consortium for Political Research Conference, Glasgow, Scotland.

- Iggulden, Tony. 2017. “Union Boss Wants Underpaying Employers Jailed for ‘Wage Theft’.” ABC News, May 16. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-05-16/union-boss-wants-underpaying-employers-jailed/8528882.

- Jensen, Carsten, and Henrik Beck Seeberg. 2019. “On the Enemy’s Turf: Exploring the Link Between Macro- and Micro-Framing in Interest Group Communication.” Journal of European Public Policy 27 (7): 1054–1073. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2019.1659845.

- Jones, Bryan, and John Baumgartner. 2005. The Politics of Attention. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Karp, Paul. 2016. “Coalition Plans Crackdown on 7-Eleven Style Wage Theft.” The Guardian, May 16. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2016/may/19/coalition-plans-crackdown-on-7-eleven-style-wage-theft.

- Khadem, Nassim. 2019. “Michael Hill Jewellers Admits It Underpaid Staff by up to $25 Million.” ABC News, July 11. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-07-11/michael-hill-jewellers-says-it-underpaid-staff-up-to-2425m/11299162.

- Kingdon, John. 1984. Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies. Boston: Little, Brown.

- Laws, David, and Martin Rein. 2003. “Reframing Practice.” In Deliberative Policy Analysis: Understanding Governance in the Network Society, edited by Maarten Hajer and Hendrik Wagenaar, 172–206. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lisi, Marco, and João Loureiro. 2022. “Interest Group Strategies and Policy Involvement: Does the Context Matter? Evidence from Southern Europe.” Interest Groups & Advocacy 11 (1): 109–135. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41309-021-00145-w.

- Marin-Guzman, David. 2017. “Heavier Fines for Wage Rip-Offs.” Australian Financial Review, March 2: 7.

- Marin-Guzman, David. 2021. “Unions and Employers Oppose Federal Wage Theft Laws.” Australian Financial Review, February 6. https://www.afr.com/work-and-careers/workplace/unions-and-employers-oppose-federal-wage-theft-laws-20210205-p56zuv.

- “Minimum Wage: Numerous Evasions Alleged.” 1897. The Age, March 26: 6. https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/193696882?searchTerm = The%20minimum%20wage%3A%20numerous%20evasions%20alleged.

- Morey, Mark. 2017. “We Should Have a Royal Commission into Wage Theft.” Sydney Morning Herald, February 16: 17.

- Munro, Peter. 2003. “My Career – Copping It Sweet.” Sydney Morning Herald, June 28: 1.

- Munton, Joellen, Andrew Stewart, Shae McCrystal, Tess Hardy, and Adriana Orifici. 2021. “The (Omni) Bus That Broke Down: Changes to Casual Employment and the Remnants of the Coalition’s Industrial Relations Agenda.” Australian Journal of Labour Law 34 (3): 132–169.

- NTEU (National Tertiary Education Union). 2023. Wage Theft Report. NTEU. https://www.nteu.au/News_Articles/National/Wage_Theft_Report.aspx#:~:text = News%20Update%2C%2022%20February%202023,part%20of%20universities%27%20business%20models.

- Nutt, Tony. 2016. Coalition Election Policy — Protecting Vulnerable Workers. Liberal-National Coalition. https://cdn.liberal.org.au/pdf/policy/2016 Coalition Election Policy - Protecting Vulnerable Workers.pdf.

- Olsen, William. 2020. “Victory for Andrews Labor Government as Anti-Wage Theft Law is Passed.” Independent Australia, June 26. https://independentaustralia.net/politics/politics-display/victory-for-andrews-labor-government-as-anti-wage-theft-law-is-passed,14041.

- Otter, Caley. 2020. Wage Theft Bill 2020, Bill Brief. Research Note No. 4. Parliament of Victoria.

- Patty, Anna. 2018. “Unions Watchdog Gets Funding Boost, but Fair Wages Enforcer Misses Out.” Sydney Morning Herald, May 9. https://amp.smh.com.au/business/workplace/unions-watchdog-gets-funding-boost-but-fair-wages-enforcer-misses-out-20180509-p4zea5.html.

- Porter, Christian. 2019. Fair Work (Registered Organisations) Amendment (Ensuring Integrity) Bill 2019 Explanatory Memorandum. Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia. https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Bills_Legislation/Bills_Search_Results/Result?bId = r6348.

- Pralle, Sarah. 2006. Branching Out, Digging. In: Environmental Advocacy and Agenda Setting. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt2tt4d7.

- Pralle, Sarah. 2009. “Agenda-Setting and Climate Change.” Environmental Politics 18 (5): 781–799. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644010903157115.

- Rein, Martin, and Donal Schön. 1993. “Reframing Policy Discourse.” In The Argumentative Turn in Policy Analysis and Planning, edited by Frank Fischer and John Forester, 145–166. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

- RMIT ABC Fact Check. 2023. “Promise Check: Legislate to Make Wage Theft a Criminal Offence.” ABC News, May 19. Accessed March 4, 2024. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2023-05-19/promise-check-make-wage-theft-criminal-offence/101791840.

- Rochefort, David, and Roger Cobb. 1994. The Politics of Problem Definition. Lawrence, Kan: University Press of Kansas.

- Schneiders, Ben. 2022. Hard Labour: Wage Theft in the Age of Inequality. Melbourne: Scribe.

- Schneiders, Ben, and Royce Millar. 2016. “Chemist Chain Probed Over Worker Pay.” The Age, November 8: 6.

- Schneiders, Ben, Nick Toscano, and Royce Millar. 2016a. “Hamburgled: McDonald’s, Coles, Woolworths Workers Lose in Union Pay Deals.” Sydney Morning Herald, May 19. https://www.smh.com.au/business/workplace/hamburgled-mcdonalds-coles-woolworths-workers-lose-in-union-pay-deals-20160518-goycw5.html.

- Schneiders, Ben, Nick Toscano, and Royce Millar. 2016b. “Sold Out: Quarter of a Million Workers Underpaid in Union Deals.” Sydney Morning Herald, August 30. https://www.smh.com.au/business/workplace/sold-out-quarter-of-a-million-workers-underpaid-in-union-deals-20160830-gr4f68.html.

- Searle, Adam. 2021. “From Underpayments to Epidemic.” Workplace Review 11 (1): 30–36.

- Stanford, Jill, Tess Hardy, and Andrew Stewart. 2018. “Australia, We Have a Problem.” In The Wages Crisis in Australia, edited by Adam Stewart, Tess Hardy, and Jill Stanford, 3–20. South Australia: University of Adelaide Press.

- Stensholt, John, and Ewan Hannah. 2019. “Calombaris scandal sparks ‘firestorm’”. The Australian, 3 August: 29

- Teicher, Julian. 2020. “Wage Theft and the Challenge of Regulation.” In Contemporary Work and the Future of Employment in Developed Countries, edited by Peter Holland and Chris Brewster, 50–67. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Thompson, Sarah, and Simon Evans. 2017. MasterChef Judge’s $2.6 m Pay Blunder.” Australian Financial Review, April 4: 3.

- Toscano, Nick, and Sarah Danckert. 2017. “Zombie Deal Stings Bakers.” The Age, January 2: 1.

- Valent, Dani. 2019. “‘Scared’ Chefs Seek Amnesty on Wage Scandals.” Sydney Morning Herald, October 3: 1.

- Varga, Remy. 2019. “ABC’s Faine Breaks Ranks over Calombaris.” The Australian, August 1. Accessed via Factiva.

- Varone, Frédéric, Roy Gava, Charlotte Jourdain, Steven Eichenberger, and André Mach. 2018. “Interest Groups as Multi-Venue Players.” Interest Groups & Advocacy 7 (2): 173–195. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41309-018-0036-2.

- Vos, Marita, Henny Schoemaker, and Vilma Liisa Luoma-aho. 2014. “Setting the Agenda for Research on Issue Arenas.” Corporate Communications: An International Journal 19 (2): 200–215. https://doi.org/10.1108/CCIJ-08-2012-0055.

- Willox, Innes. 2020. “Weigh Calombaris Facts Before Joining Lynch Mob.” Herald Sun, February 15: 59.

- Yordy, Jill, Jongeun You, Kyudong Park, Christopher M. Weible, and Tanya Heikkila. 2019. “Framing Contests and Policy Conflicts Over Gas Pipelines.” Review of Policy Research 36 (6): 736–756. https://doi.org/10.1111/ropr.12364.