ABSTRACT

This article examines the different use of internet memes between political party organisations and partisan spaces. We analyse the relationship between organisational logics and memes as a genre characterised by participation. We conduct a mixed-methods analysis of the internet memes posted by five Australian political parties, their youth branches, and partisan meme spaces during the 2022 Australian federal election. We identify three styles of memetic content created by political parties and partisans: professional, generic, and participatory. We argue that these different kinds of meme each relate to particular organisational logics, with the hierarchical structures of professional election campaigns largely hollowing out the participatory potential of internet memes in both production and form.

Memes have become ubiquitous in discussion around digital campaigning in recent years, with growing attention on the function of social media in election campaigns and politics more generally (Dean Citation2019; Gibson Citation2020). This has become especially pronounced in news coverage. For example, coverage of the 2022 Australian federal election reported on a ‘meme war’ (Butler Citation2022), ‘meme factory’ (Dahlstrom Citation2022), and ‘shitposting’ (Wilson Citation2022) – all of which seems at first deeply unserious in the context of a first-order election. Academic research on internet memes in elections tends to emphasise the content and groups created by ‘grassroots’ partisan supporters outside of formal party organisation structures, which we refer to in this article as ‘partisan spaces’ (McKelvey, DeJong, and Frenzel Citation2023; see also: McLoughlin and Southern Citation2021; Moody-Ramirez and Church Citation2019). This tendency in academic research to view memes as the domain of peripheral, grassroots actors outside the direct control of the party appears to conflict with the popular media narrative (as illustrated by the above news articles) that party organisations are the key actors investing resources in competing meme strategies, as the production and circulation of internet memes becomes institutionalised within a party or campaign apparatus (Baulch, Matamoros-Fernández, and Suwana Citation2024; Burroughs Citation2020).

Beyond the horse-race narrative of who is winning the ‘meme war’ in any given election, we are interested in a potentially obscured contest between parties and partisans about what memes mean. In particular, we are interested in the tug-of-war between the party organisational logic anchored in hierarchical structures and professionalised, highly managed campaigns (Gibson Citation2020) – what has elsewhere been termed the ‘vertical models of linkage and engagement: leader-focused, centralised, bureaucratic organisations that market finished programs to the public’ (Bennett, Segerberg, and Knüpfer Citation2018, 1658) – and memes as characterised by their participatory implications and the way their circulation and reproduction relies on specific subcultural understandings (Nissenbaum and Shifman Citation2017; Shifman Citation2014). In this paper, we ask two questions. First, how is the organisational character of meme posters expressed in the way they use memes? Second, do memes across these various permutations provide a means for citizens to participate in election campaigns, or have internet memes become integrated into the professional repertoire of party organisations, losing their participatory potential in the process? To answer these questions, we conduct a mixed-methods study of the use of internet memes by five Australian political parties during the 2022 federal election: the Australian Labor Party (ALP), the Liberal Party of Australia (Liberals) and its junior coalition partner the National Party of Australia (Nationals), the Australian Greens Party (Greens), and Pauline Hanson’s One Nation (PHON).

Using quantitative content analysis (Krippendorff Citation2018), we first examine the salience and thematic focus of internet memes in a campaign context. Then, using critical visual analysis (Rose Citation2016) we examine the aesthetic qualities of a subsample of the memes, to explore how their production and circulation relates to the particular communicative and participatory imperatives of the campaign. This analysis is supplemented with several semi-structured interviews with meme creators working either with one of the parties’ digital communications team during the 2022 election campaign, or alternatively, administrating a partisan meme space not formally affiliated with a party. These interviews provide further insights into the digital communications strategies of the parties, and the place of memes and participation in them.

We find, first, that internet memes constitute on average less than 15% of the images shared by Australian political parties, when taking partisan supporter meme pages out of consideration. During the 2022 federal election campaign, memes functioned primarily as a means of visual attack ads or negative campaigning, consistent with previous research that found memes are used primarily to mock or ridicule political opponents (McKelvey, DeJong, and Frenzel Citation2023), rather than promote a party’s platform or policy agenda (McLoughlin and Southern Citation2021). Building from this initial quantitative work into the critical visual analysis, we identify three distinct styles of internet memes circulated by political parties and partisans: professional, generic, and participatory. These styles point to differences in aesthetic quality and production value (professional memes compared to generic and participatory memes) and the required subcultural knowledge for interpretation (professional and generic memes compared to participatory memes). We argue that these variations in aesthetic quality and required subcultural literacy reflect the participatory character of the content and the organisational logics of the social media users who post them.

Internet memes and political parties

Internet memes are groups of digital items sharing common characteristics of content, form, and stance, created and circulated via the internet with awareness of each other (Shifman Citation2014). These shared characteristics constitute a template, which functions as the base from which users create unique variations (Nissenbaum and Shifman Citation2018). The ability for audiences to understand a specific meme instance often relies on specific (sub)cultural knowledge (Miltner Citation2014; Nissenbaum and Shifman Citation2017; Shifman Citation2014) with the successful diffusion of a meme contingent on it fitting the frames of the social networks in which they are produced (Spitzberg Citation2014). Memes fulfil a variety of social functions. These include the construction of shared values, identity formation and the maintenance of social boundaries (Gal, Shifman, and Kampf Citation2016; Katz and Shifman Citation2017; Shifman Citation2014). As a form of cultural capital, meme literacy distinguishes members of an in-group through their understanding of particular practices of memetic construction and so fulfils a gatekeeping function (Milner Citation2016; Nissenbaum and Shifman Citation2017). The choice to publish a particular meme in a particular digital space is one which ‘co-constructs’ both individuals as content creators and replicators, as well as a broader collective or community (Gal, Shifman, and Kampf Citation2016, 1701).

As a form of public discourse, memes about politics are a means of participating in normative arguments ‘about how the world should look and the best way to get there’ (Shifman Citation2014, 120). In this regard they fulfil three functions: persuasion or political advocacy, a form of grassroots action, and as modes of expression and public discussion (Shifman Citation2014). In the context of political campaigns, memes have been used to consolidate political allegiances, and through their virality influence broader political discourses (Dean Citation2019). Memes can make political messages more accessible to broader audiences, deactivating group boundaries through humour and the remixing of pop culture iconography (McSwiney et al. Citation2021). Though the policy content of political memes has typically been low, memes can still play an important informational role in bringing political content to those who otherwise may not see it (McLoughlin and Southern Citation2021). Typically, political parties have deployed memes to ‘de-brand or deconstruct’ (McKelvey, DeJong, and Frenzel Citation2023, 1636) and mock political opponents (Dean Citation2019). This makes them a useful form of negative campaigning, shoring up political identities and the alliances and antagonism associated with them (Dean Citation2019). That is, memes tend to make supporters feel better about their own party or candidates, while increasing dislike of opponents (Moody-Ramirez and Church Citation2019). However, memes appear to have little effect in shifting political ideology, with research suggesting that ‘political memes are not vectors of persuasion’ (Galipeau Citation2023, 448).

Partisan meme spaces which support a party, but are not directly party controlled, use memes as a form of participatory media during campaigns to build community and hence partisanship, rather than trying to sway voters to influence electoral outcomes (McKelvey, DeJong, and Frenzel Citation2023). These informal spaces for creating and sharing memes are viewed as a potential means of citizen participation in campaigning (Gibson Citation2015). These ‘partisan scenes’ provide a space for supporters to discuss issues in a more ideological and provocative manner than the party organisation itself (McKelvey, DeJong, and Frenzel Citation2023). At the same time, we know parties are courting meme makers and their followers to reach wider (read: younger) audiences (Kreiss Citation2016). Indeed in some cases, political parties have hired or established ‘meme factories’ of content creators to churn out campaign content (Baulch, Matamoros-Fernández, and Suwana Citation2024).

The 2022 Australian federal election

The 2022 Australian federal election was announced on 10 April and took place on Saturday, 21 May. All 151 seats in the House of Representatives, and 40 (of 76) seats in the Senate were contested. The conservative Liberal-National Coalition government led by Prime Minister Scott Morrison was defeated and the Australian Labor Party led by Anthony Albanese was returned to government for the first time since 2013. Meanwhile, the Australian Green Party led by Adam Bandt achieved historic results, winning 3 lower house seats in Brisbane in the state of Queensland for the first time. On the other end of the political spectrum, Pauline Hanson’s eponymous far-right party, Pauline Hanson’s One Nation, performed so poorly that Hanson only narrowly managed to retain her seat in the Senate (McSwiney Citation2024). In terms of issues, the economy and economic management were most important among voters, with rising inflation and slow wage growth in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic raising widespread concern over the cost of living, followed by climate change and health (Cameron et al. Citation2022). Political leadership and matters of integrity also factored as a key issue determining how citizens voted (Cameron et al. Citation2022), with Morrison regarded as widely unpopular by the electorate (Gauja, Sawer, and Sheppard Citation2023; McAllister Citation2023).

Research design

We take a mixed-methods approach, combining quantitative content analysis (Krippendorff Citation2018) and qualitative visual analysis (Rose Citation2016). This is supplemented with four semi-structured interviews: three with people who had worked on a party’s digital campaigns, and one with the creator behind one of the biggest partisan meme pages in Australian politics. We focus on Facebook and Instagram. Our sample includes (where available) the public Facebook pages and Instagram accounts for the five parties mentioned above, each of the parties’ leader, youth branch, and one partisan meme page associated with the party (). Including these four page and account types covers a range of professionalism and organisation within the party, from the leader and national party at one end, to partisan meme pages on the other. The inclusion of party youth branches provides a middle ground between the two, as they tend to be formally associated with, but largely autonomous from, the central party and without the same expectations of professionalism.

Table 1. Summary of Australian political party and partisan meme Facebook and Instagram accounts.

Facebook and Instagram are selected as two of the most used social media platforms in Australia. While the technological affordances of both platforms encourage extensive use of visual media, Instagram is a specifically visual medium. The Instagram platform architecture is built around ‘grids’, profiles of still and video visual media uploaded and shared by the user. These materials remain on the user’s grid unless taken down or hidden. This contrasts with other means of sharing visual media on Instagram like ‘stories’, which are automatically removed after 24 hours, or private messaging. The Facebook platform architecture includes several interfaces. We focus on Facebook pages, ‘the most public parts of Facebook,’ which constitute a ‘mass media like one-to-many communication’ (Rieder et al. Citation2015, 3–4). Pages are themselves comprised of various components, including a ‘timeline’ where all posted material is listed in chronological order (except for pinned posts). This is then broken up by specific tabs for still images (‘photos’), pre-recorded video material (‘videos’), and archived live video footage (‘live’).

Our data collection comprises all images posted to the public timeline or grid of the selected pages and accounts during 2022 federal election campaign (10 April – 21 May 2022), excluding profile and banner images, and video content. Content was collected via the CrowdTangle researcher API. This resulted in a total of 3,424 images (Facebook = 2142, Instagram = 1282). To make the data feasible for human coding, we first did an initial round of quantitative coding, manually identifying internet memes from this larger set of images (testing inter-coder reliability for this initial relevance on a sample of 30 images resulted in perfect agreement between the two coders). We identified a subset of 514 internet memes (Facebook = 331, Instagram = 183). We drew a random sample of 100 memes each from Facebook and Instagram to code in greater detail.

For the quantitative content analysis we coded for basic descriptive and compositional variables, such as: whether the image included pop culture references; whether the image referenced a party leader (either from the page’s own party or an opponent); whether the image was user generated in the sense of being explicitly attributed to a user either in the image or accompanying text; whether the tone of the image was positive or negative; what issue the image related to, such as education or the environment; and whether the aesthetic of the meme was DIY (do-it-yourself) in the sense of being possible to create for individuals with no particular technical skills or software. These codes all met acceptable thresholds for intercoder reliability (see table A1 in Appendix for individual Krippendorff’s alpha values). We included an open text field where we noted any recognisable meme templates.

We then undertook a more substantiative qualitative analysis of a subset of the memes, drawing on Rose’s (Citation2016) method of critical visual analysis to understand how visual media can be used to construct and represent the social world. Here, we pay close attention to the overall composition of a meme, including its aesthetic sophistication, and situate the memes in their broader political and cultural context. This was supplemented by semi-structured interviews, to better understand the intent and processes behind the production and circulation of internet memes in party and partisan spaces. Despite difficulties in gaining access, which was expected given the general culture of secrecy that Australian political parties operate in (Gauja and McSwiney Citation2019), we completed four interviews with a mix of party campaign staff and partisan administrators, drawn from three different parties covering a range of ideological orientations. These interviews provide critical firsthand insights into how memes are used in election campaigns, and the tensions between party and partisan memes.

Findings

The salience of memes in Australian election campaigns

From the number of internet memes posted, it is clear that memes constitute only a small proportion of the wider digital visual media created and circulated by Australian political parties during the 2022 federal election – at least on Facebook and Instagram. This is consistent with previous research that found the salience of political memes has been overstated in some contexts (McSwiney et al. Citation2021). Across all pages in our study, the mean proportion of image posts containing memes was 15% (although this average was as expected higher for partisan spaces at 28% compared with 13% for all other pages, and these proportions mask considerable variation in the number of posts by each page).

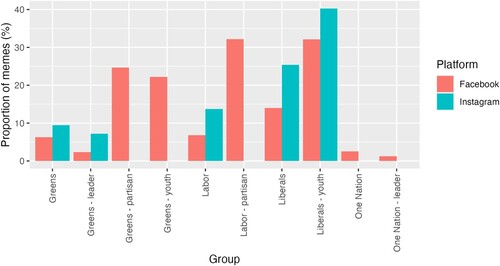

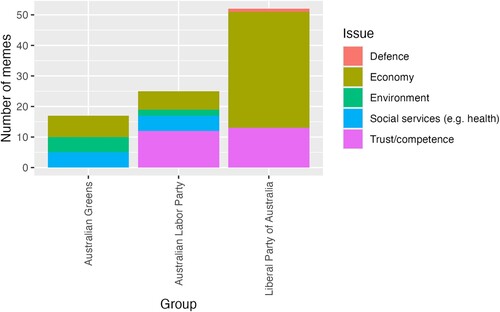

The Nationals did not create or circulate internet memes from any of their accounts, while the PHON national party organisation posted only a handful. Overall, the visual content of the Nationals and PHON is very limited compared to the ALP, Liberals, and Greens. While the other three parties posted internet memes, there are differences in the way they are distributed across the different types of pages and accounts sampled (). For the ALP, the national party organisation posted more memes than the partisan meme space, but the accounts for the party leader Anthony Albanese and the youth branch posted no memes. For the Liberals, the national party organisation likewise posted most of the memes, with many also originating with the youth branch. However, though there was a Liberal party partisan meme space on Facebook it was inactive during the election, and Liberal leader Scott Morrison did not post any memes. In the Greens, the national party organsiation, leader Adam Bandt, youth branch, and partisan meme page all posted memes, though the greatest quantity was posted by the partisan space.

Among these three parties, several clear patterns emerged. First, in terms of content themes, the main topics each of the parties shared memes about generally followed their characteristic policy focuses (). The ALP posted memes mostly on political trust (48%), followed by the economy (24%) and social services (20%). The Liberals also posted memes about political trust (25%), but not nearly as often as memes about the economy (73%). The Greens focused on a mix of the economy (30%), social services (22%), as well as environmental issues (22%). Cost of living was a thematic emphasis across all three parties.

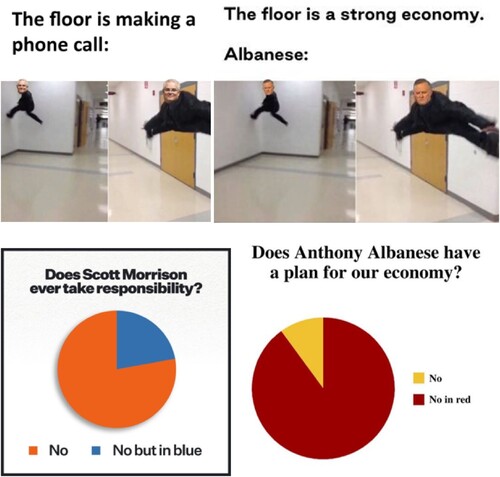

Second, and expectedly, pop culture references were frequently deployed, with 42% of our coded sample containing references to pop culture icons like the animated sitcom The Simpsons or science fiction franchise Star Wars. Third, memes rarely included images of the leader of the party sharing the meme (e.g. Liberal memes rarely included Scott Morrison), but often referenced the leader of another party leader (e.g. ALP memes often included Scott Morrison). This was typically to mock or ridicule the leader of an opposing political party as a means of visual negative campaigning. Fourth, and relatedly, the ALP and Liberals appear to engage in a degree of content copying in terms of memetic templates used. For example, it was not uncommon for a meme posted by the ALP attacking the Liberals to be reposted by the Liberals shortly after but remixed to flip the attack on the ALP, and vice versa (Figure ).

Figure 3. Examples of meme reproduction by the ALP (top left, bottom left) and Liberals (top right, bottom right) attacking the leader of the opposing party. Source: @AustralianLabor, @LiberalPartyAustralia, Facebook.

Last, participatory and user-generated content is quite minimal in the official election campaigns of the parties (i.e. circulated in posts by the accounts of the national party organisation or party leader). This applies in terms of both creator attribution (either in image or in accompanying text), as well as whether memes were cross-posted from youth branches or the partisan spaces. Memes shared by the ALP and Liberal parties in particular appear to be exclusively ‘in-house’ products created by those formally affiliated with the digital campaigns. In the case of the Greens, there were some images circulated that originated in the partisan meme space and youth branch – though without attribution – or were follower submitted (and acknowledged in the accompanying text), but this was in the minority of the content posted by the Greens party overall.

Memetic styles in election campaigns

Building on our initial quantitative content analysis, our qualitative visual analysis identified three distinct styles of internet memes posted by the parties: professional, generic, and participatory. These styles reflect differences in the aesthetic and production quality of the memes, as well as the extent of subcultural knowledge required among audiences for the intended interpretation. Though inductively developed through our visual analysis, the three styles speak to previous research on the participatory dimensions of memes (McKelvey, DeJong, and Frenzel Citation2023; Nissenbaum and Shifman Citation2017; Shifman Citation2014) and the growing professionalisation of meme production (Baulch, Matamoros-Fernández, and Suwana Citation2024; Burroughs Citation2020). They also capture the sentiment of internet culture slang used to describe different meme qualities. For example, the generic memes we identify tend to rely on highly saturated meme templates, and so in this sense respect, might be considered ‘normie’ memes in that their content is ‘boringly conventional or mainstream’ (Know Your Meme Citation2015).

Professional memes

Memes in the professional category all require a degree of sophistication with photo editing software on behalf of the creator, while lacking any significant subcultural knowledge to interpret. In the data, spoof movie posters are characteristic of this professionalised style of memes. These memes remix promotional posters from recognisable Hollywood films to ridicule political opponents. As shows, these images require some knowledge in the use of photo editing, with minimal deviation from the original promotional poster. There are no crude edges or poorly executed cut-and-paste edits. Color and font are extremely similar, if not identical, to those in the source material. Notably, this kind of meme was produced and shared almost exclusively by the accounts for the national party organisations of the ALP and Liberals. Aside from the pop culture references and the more humorous tone, these professionalised memes are not especially different from the non-memetic materials shared by these parties, such as regular campaign posters.

Figure 4. Examples of spoof movie posters as professional memes shared by the ALP (bottom) and Liberals (top). Source: @AustralianLabor, @LiberalPartyAustralia.

The better visual fidelity of these images is likely in part a product of the greater resources available to major parties in Australia. According to Clark Cooley, federal president of the Young Liberals and one of the administrators of the Young Liberal Movement of Australia page, ‘Coalition central headquarters has a social media team of 15-20 people who run all the memes for the main pages and candidates’. The thematic direction of the content, and to some extent the overall creative control, is also top-down. A member of the ALP’s organic content team within the digital campaign explained that the team would receive ‘direction about what the theme is for the day or the week, through formal channels like [team leader] coming back from the director's meeting each morning and being like: this is what's on the agenda’. What distinguishes these professional memes from other memes in the data is the lack of play or experimentation. They are (by the standards of the rest of the data) high-quality advertising products, which suggest little to no room for participatory input due to the greater technical skills involved in production.

Generic memes

Generic memes are those which the everyday social media user can be expected to understand and share. In this respect, they rely on widely circulating internet meme templates, but require no real subcultural knowledge to grasp the intended reading. They also require little-to-no technical sophistication to create, and can easily be made using online meme generators or through the insertion of minor elements like text (). This makes generic memes ideally suited to the thinness of contemporary political communications in that they allow creators to take one simple message (‘X has no plan for the economy’) and recycle it through many different templates. Doing so enables creators to keep the novelty of the visual content alive (by rotating the meme the message is communicated through) while reinforcing the same strategic narrative.

Figure 5. Examples of generic memes shared by the Australian Greens for Actually Progressive Teens (top left), Young Liberals (top right), ALP (bottom left) and Pauline Hanson’s One Nation (bottom right). Source: @GreenMemes, @YoungLibs, @AustralianLabor, @OneNationParty.

Such memes also rely on common pop culture references like The Simpsons. The reason for this, explained Elizabeth Thomspon, a former convenor of the New South Wales Young Greens who helps administer the Australian Young Greens Facebook page, is because the show ‘plays a bit to people's comfort and familiarity … people like it when they get the reference.’ The administer behind partisan meme page Australian Green Memes for Actually Progressive Teens agrees: ‘I think your Simpsons references are very ubiquitous with political memes, not just in Australian, but everywhere … the best memes are timeless … we've all grown up with The Simpsons’. Interestingly, the accessibility of The Simpsons as a cultural reference has a standarising effect on the kind of memes produced. As Clark Cooley explained, though the Young Liberal Movement of Australia page tried to experiment with other references and templates, The Simpsons content was so successful that they kept returning to it for their memes:

We tried different things out. We had a meme about the Real Housewives of Melbourne. We tried movies, we tried Pokémon … We tried a whole bunch of other stuff, Star Wars, all of this. But really what cut through is The Simpsons. I think maybe it's universal, maybe everyone knows it. You don't have to get Star Wars humour. Not everyone understands that, but everyone, everyone knows that [The Simpsons character] Homer is an idiot. So when we put a video with Anthony Albanese not knowing the unemployment rate, and Homer Simpson dubbed over the top, people get that.

Participatory memes

In contrast to the professional and generic memes, we identify a third group, participatory memes. Aesthetically, participatory memes are comparable to those in the generic meme category. What distinguishes them is the greater degree of subcultural knowledge required for interpretation.

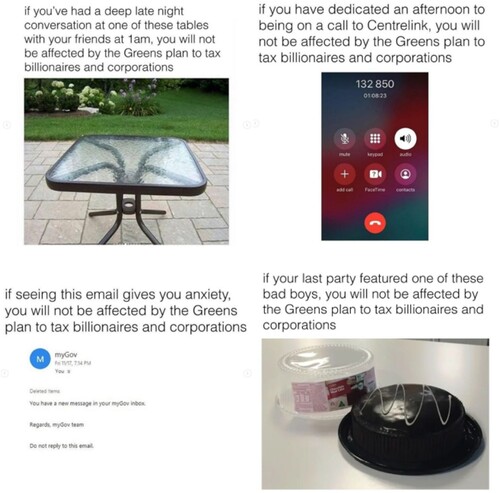

The best example of participatory memes in the campaign originated in the Greens-supporting partisan page Australian Green Memes for Actually Progressive Teens. In particular, a set of image macro memes spruiking the Greens proposed billionaire tax (). Here, the use of images like the glass-topped outdoor table and Coles supermarket chocolate cake, and references to MyGov emails and calls to social service provider Centrelink, have a specifically ‘ordinary’ character to them. These visual cues are distinctly recognisable to a younger and typically more financially precarious Australian audience that is particularly active on social media, but are likely make little sense to those outside the intended audience. This is very much the creator’s intent. As the page’s administrator explained, they wanted to do something ‘quintessentially Australian’ with this content to really drive home the message that the vast majority of Australians would be unaffected by proposed tax: ‘I Googled kind of like your Buzzfeed lists, like classic, “this is how you know you're Australian,” that kind of thing’. The result is images which provoke a sense of authenticity, suggesting that the creator too is just like the intended audience, in that they also ‘get’ these distinctly Australian cues. In this respect, participatory memes differ from those in the professional and generic categories in that they have an originality and specificity which allows the sharer to articulate a positionality as outside the party-professional clique.

Figure 6. Examples of billionaire tax memes. These memes, originally posted by the Australian Green Memes for Actually Progressive Teens partisan page were later picked up and reposted by accounts for the Greens party organisation and party leader Adam Bandt.

This aligns with the more participatory nature of the Greens meme community. Memes shared by the party and party leader Adam Bandt were occasionally lifted from the partisan Green Memes for Actually Progressive Teens or Young Greens pages, which in turn were often submitted by the followers of these pages. Indeed, as the administrator of Green Memes for Actually Progressive Teens explained, once they posted the first few memes in the billionaires tax series, followers then started submitting their own, which would then be reposted to the page as an album to collate all the related content, with attribution to the submitting page followers.

Political memes between parties and partisans

Despite the hype, not all parties who engaged in digital campaigning posted internet memes. Pauline Hanson’s One Nation posted only three memes and the Nationals posted none. This is surprising given the low production costs to make such content relative to other digital visual media like the Please Explain animated miniseries that PHON has been commissioning since 2021 (McSwiney and Sengul Citation2024), and in the case of the Nationals is at odds with the posting activity of their senior coalition partners the Liberals. Among the pages of parties that more frequently posted memes during the 2022 federal election campaign – the ALP, Liberals, and Greens – we find a clear relationship between the production and circulation of memes, and the type of organisation that shares the content. For the most part, when Australian political parties use internet memes, it is a top-down process, consistent with the institutionalisation and professionalisation of meme production in political campaigns elsewhere (e.g. Baulch, Matamoros-Fernández, and Suwana Citation2024; Dean Citation2019). What we call professional memes are the bulk of memetic content produced and shared by the main party pages and accounts of the ALP and Liberals, and to a lesser extent, of the Greens. With their high visual fidelity and a low threshold for interpretation, professional memes more closely resemble the corporate ‘meme-jacking’ advertisements of the 2010s (Milner Citation2016). This content is the most accessible for a broad audience of social media users, but in the pursuit of accessibility and reach effectively reduces the genre of internet memes to digital advertising.

However, there is a tension between the hierarchical logic of party and campaign organisation, and participatory internet cultures present on social media and meme audiences. This tension is found in the simultaneous use of professional memes and what we term generic memes, characterised by an amateurish do-it-yourself or ‘internet ugly’ aesthetic (Douglas Citation2014). What makes the DIY aesthetic of generic memes noteworthy is that paid party professionals who have the time to produce high quality content (professional memes) are also creating content that looks deliberately amateurish (generic memes). In effect, they are aping this DIY aesthetic for a specific communicative purpose: to fake the participatory ethos of meme cultures to make content appear authentic.

This mix of low-quality generic memes alongside the professionalised content (and wider high-budget digital campaign materials like campaign videos) can be explained by the need for party organisations to speak to broad and diverse audiences. Our interviewee from the ALP campaign team suggested that this was because:

The party permits, the party facade rather, not the structure, but the party voice permits a multitude of different voices and a multitude of different tonalities. So, you can have a Kardashian meme and anime manga meme go out under the same banner. And people intellectually appreciate that there are different tonalities within a bigger institutional voice.

I think that the organisational level is better at empowering and permitting creativity for the same reason. They know that they need to have a breadth of voice, whereas I think when you get to an individual, a human, there is a clear or a desire to have a clear voice, and typically for that voice to … have a kind of dignity to it.

His whole staff basically wanted to file off any rough edges. They didn't want anything going to him that they didn't think he would sign off, which meant that everything was extremely vanilla. I was able to add a little bit of colour into it, but it required a lot of consultation and fighting.

For partisan and youth branch spaces, the participatory potential aligns with the more decentralised, bottom-up organisational structures. In this content, internet memes were viewed as a way for people to engage in politics, while also addressing gaps in campaign capacity by sharing the burden of content creation. Elizabeth explained that the Young Greens page had set up ‘a group where people could submit their own content and we would credit whoever made that content and essentially just give them the framework to do it.’ Likewise, the moderator of the Greens partisan page would accept memes submitted by users either via direct messaging or in the comments under other posts on the page. This participatory approach to production helps to foster a sense of community around the pages, which the creators believe contributes to the wider Greens activist base: ‘You have opportunities to, I guess, raise their engagement level from just a once off to following the page to then joining the party to then in volunteering and things like that. And those opportunities can occur within each post,’ said the moderator of the Greens partisan page. There is also an ideologically affinity between the Greens and the participatory impetus of internet memes, as Elizabeth explained:

You’ve got this ideology of grassroots democracy [in the Greens], but we need to be able to enact that. And I think that's more than just making sure everybody's heard at the meeting or consensus decision making. So, in the way in which we campaign … was by making it easier to be able to have the content bringing people in because it's how you build a movement, giving people something to do. And not [just] making them feel like they are, but generally showing them that they are making a difference.

was wasting as much time as possible of our opposition … if I can put out a post which says it won't be ‘easy under Albanese’, and we get five-thousand interactions with that, that's five-thousand interactions that they [ALP supporters] are having with us rather than swing voters in North Sydney.

In the ALP and Liberals, it seems that the relationship between party and partisan spaces was particularly close, though the partisan and youth branch spaces acted autonomously. For example, Clark explained that the relationship between the youth branch page and the central digital campaign team was ‘very close … we talk every day. If there's things that they have created that they've got extra, I have no problem throwing it up [on our page]. So sometimes that higher quality stuff does drip down to us.’ In the ALP, our interviewee said that of the various ALP meme account across social media, a significant proportion are ‘probably managed or owned by people who were connected to the campaign’, and had likely come to work on the official campaign because of their other social media accounts:

It's not like the party directs or facilitates it in any way or resources it in any way. It's more that somebody within … the ‘extended Labor cinematic universe’ has just decided to make it [a meme page], and then by virtue of being reasonably good at it, ends up having a position in the campaign … There is a degree of collusion during the campaign, but it would be inaccurate to assume that it was an astroturfing exercise of the party cultivating all of these different groups off to the side.

Conclusion

Memes have, for the most part, become integrated into the communications repertoire of party organisations. At the same time, memes represent a limited – albeit conversation driving – component of the professional digital campaigns of Australia’s major parties. Previous research suggests that this cut through does not improve policy knowledge among voters (McLoughlin and Southern Citation2021). Rather, political parties tend to use internet memes as a way of boosting brand recognition and exposure (McKelvey, DeJong, and Frenzel Citation2023). This is consistent with our findings that memes are primarily used by Australian political parties in a campaign setting as negative ads attacking political opponents, rather than positive policy proposals. An exception to this trend is the series of billionaire tax memes shared by some of the Greens party and partisan pages and accounts, discussed above.

We find that the way political parties use internet memes is less about finding innovative ways to engage a broader base of citizens in politics, and more about developing a narrow extension of the existing strategic communication repertories of parties. The hope that followers of a party’s social media will repost their content in their own networks, and so reach wider audiences, no doubt informs why Australian parties pursue memes as part of their digital campaigns (McSwiney Citation2021; see also: Galipeau Citation2023; McLoughlin and Southern Citation2021). But is this actually the case, and what electoral impact do memes have? As Galipeau (Citation2023) notes, more research is needed regarding the effects (if any) memes have on vote choice or agenda setting. Our interviewees were no more certain. Elizabeth said they ‘don’t think many votes have swung through social media’ and our interviewee from the ALP’s organic content team was similarly uncertain: ‘I don't know how many votes it wins’. Part of the problem, as Clark notes, is that the page and account administrators do not really know who the actual audience is: ‘it’s just so difficult to know whether or not we're just talking to our own people or we're actually talking to swing voters’.

Given this uncertainty, what seems most likely is that the production and circulation of memes in political campaigns is less about converting swing voters as it is engaging and energising existing members and supporters of a party (Dean Citation2019; McKelvey, DeJong, and Frenzel Citation2023). Their adoption seems in large part driven by party competition dynamics, especially if we consider the ways the major parties essentially copy the content posted by their opponents. As we demonstrate, the story for partisans is more complex. Here, memes serve a general function of engaging party supporters and members. However, they also play party-specific roles: representing genuine efforts at practicing central ideological pillars of the party in the case of the Young Greens and Greens partisan spaces, or as a means of opposition campaign time-wasting – a rather literal kind of ‘wasteful online play’ (Seiffert-Brockmann, Diehl, and Dobusch Citation2018) – in the case of the Young Liberals. That internet memes derive so much media coverage is more indicative of journalistic and editorial interest, in that it provides a novel angle for campaign reporting with a potential youth focus, rather than reflecting the actual political impact of memes or their importance to a party’s campaign overall.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Anika Gauja and participants at 2023 Australian Political Studies Association general conference for their supportive feedback on an earlier version of the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jordan McSwiney

Jordan Mcswiney is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow in the Centre for Deliberative Democracy and Global Governance at the University of Canberra. Jordan McSwiney researches the far right, with a focus on the organisation and communication of far-right parties and movements. He is the author of Far-Right Political Parties in Australia: Disorganisation and Electoral Failure (Routledge).

Michael Vaughan

Michael Vaughan is a Leverhulme Early Career Fellow at the International Inequalities Institute. He completed his PhD at the University of Sydney on the contentious politics of international tax, and then worked as a postdoctoral researcher at the Weizenbaum Institute for the Networked Society in Berlin with a focus on far-right digital communication. His research interests include digital political participation, far-right politics and the communicative dimension of mobilisation around economic inequality.

References

- Baulch, E., A. Matamoros-Fernández, and F. Suwana. 2024. “Memetic Persuasion and WhatsAppification in Indonesia’s 2019 Presidential Election.” New Media & Society 26 (5): 2473–2491. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448221088274.

- Bennett, W. L., A. Segerberg, and C. B. Knüpfer. 2018. “The Democratic Interface: Technology, Political Organization, and Diverging Patterns of Electoral Representation.” Information, Communication & Society 21 (11): 1655–1680. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1348533.

- Burroughs, B. 2020. “Fake Memetics: Political Rhetoric and Circulation in Political Campaigns.” In Fake News: Understanding Media and Misinformation in the Digital Age, edited by M. Zimdars, and K. McLeod, 191–200. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Butler, J. 2022, April 30. “Labor and the Liberals are waging an election meme war – but what is the point?” The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2022/may/01/labor-and-the-liberals-are-waging-an-election-meme-war-but-what-is-the-point.

- Cameron, S., I. McAllister, S. Jackman, and J. Sheppard. 2022. The 2022 Australian Federal Election: Results from the Australian Election Study. Canberra: Australian National University. https://australianelectionstudy.org/wp-content/uploads/The-2022-Australian-Federal-Election-Results-from-the-Australian-Election-Study.pdf.

- Dahlstrom, M. 2022, April 12. ScoMo’s ‘worst nightmare’: The $74k meme factory that could change the election. Yahoo News. https://au.news.yahoo.com/scott-morrison-worst-nightmare-federal-election-meme-factory-082116526.html.

- Dean, J. 2019. “Sorted for Memes and Gifs: Visual Media and Everyday Digital Politics.” Political Studies Review 17 (3): 255–266. https://doi.org/10.1177/1478929918807483.

- Douglas, N. 2014. “It’s Supposed to Look Like Shit: The Internet Ugly Aesthetic.” Journal of Visual Culture 13 (3): 314–339. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470412914544516.

- Gal, N., L. Shifman, and Z. Kampf. 2016. “It Gets Better”: Internet Memes and the Construction of Collective Identity.” New Media & Society 18 (8): 1698–1714. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444814568784.

- Galipeau, T. 2023. “The Impact of Political Memes: A Longitudinal Field Experiment.” Journal of Information Technology & Politics 20 (4): 437–453. https://doi.org/10.1080/19331681.2022.2150737.

- Gauja, A., and J. McSwiney. 2019. “Do Australian Parties Represent?” In Do Parties Still Represent? An Analysis of the Representativeness of Political Parties in Western Democracies, edited by K. Heidar, and B. Wauters, 47–65. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Gauja, A., M. Sawer, and J. Sheppard. 2023. “Watershed: The 2022 Australian Federal Election.” In Watershed: The 2022 Australian Federal Election, edited by A. Gauja, M. Sawer, and J. Sheppard, 1–20. Canberra: ANU Press.

- Gibson, R. K. 2015. “Party Change, Social Media and the Rise of ‘Citizen-Initiated’ Campaigning.” Party Politics 21 (2): 183–197. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068812472575.

- Gibson, R. K. 2020. When the Nerds go Marching in: How Digital Technology Moved from the Margins to the Mainstream. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Katz, Y., and L. Shifman. 2017. “Making Sense? The Structure and Meanings of Digital Memetic Nonsense.” Information, Communication & Society 20 (6): 825–842. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2017.1291702.

- Know Your Meme. 2015. “Normie.” Know Your Meme. https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/normie.

- Kreiss, D. 2016. Prototype Politics: Technology-Intensive Campaigning and the Data of Democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Krippendorff, K. 2018. Content Analysis: An Introduction to its Methodology. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE.

- McAllister, I. 2023. “Party Explanations for the 2022 Australian Election Result.” Australian Journal of Political Science 58 (4): 309–325. https://doi.org/10.1080/10361146.2023.2257611.

- McKelvey, F., S. DeJong, and J. Frenzel. 2023. “Memes, Scenes and #ELXN2019s: How Partisans Make Memes During Elections.” New Media & Society 25 (7): 1626–1647. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448211020690.

- McLoughlin, L., and R. Southern. 2021. “By any Memes Necessary? Small Political Acts, Incidental Exposure and Memes During the 2017 UK General Election.” The British Journal of Politics and International Relations 23 (1): 60–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/1369148120930594.

- McSwiney, J. 2021. “Social Networks and Digital Organisation: Far Right Parties at the 2019 Australian Federal Election.” Information, Communication & Society 23 (10): 1401–1418. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2020.1757132.

- Mcswiney, J. 2024. Far-right Political Parties in Australia: Disorganisation and Electoral Failure. London: Routledge.

- McSwiney, J., and Sengul, K.. 2024. “Humor, Ridicule, and the Far Right: Mainstreaming Exclusion Through Online Animation.” Television & New Media 25 (4): 315–333https://doi.org/10.1177/15274764231213816.

- McSwiney, J., M. Vaughan, A. Heft, and M. Hoffman. 2021. “Sharing the Hate? Memes and Transnationality in the Far Right’s Digital Visual Culture.” Information, Communication & Society 24 (16): 2502–2521. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2021.1961006.

- Milner, R. M. 2016. The World Made Meme: Public Conversations and Participatory Media. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Miltner, K. M. 2014. "There’s no place for lulz on LOLCats”: The role of genre, gender, and group identity in the interpretation and enjoyment of an Internet meme. First Monday.

- Moody-Ramirez, M., and A. B. Church. 2019. “Analysis of Facebook Meme Groups Used During the 2016 US Presidential Election.” Social Media + Society 5 (1): 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305118808799.

- Nissenbaum, A., and L. Shifman. 2017. “Internet Memes as Contested Cultural Capital: The Case of 4chan’s /b/ Board.” New Media & Society 19 (4): 483–501. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444815609313.

- Nissenbaum, A., and L. Shifman. 2018. “Meme Templates as Expressive Repertoires in a Globalizing World: A Cross-Linguistic Study.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 23 (5): 294–310. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcmc/zmy016.

- Rieder, B., R. Abdulla, T. Poell, R. Woltering, and L. Zack. 2015. “Data Critique and Analytical Opportunities for Very Large Facebook Pages: Lessons Learned from Exploring “We are all Khaled Said.”.” Big Data & Society 2 (2): 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951715614980.

- Rose, G. 2016. Visual Methodologies: An Introduction to Researching with Visual Materials. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE.

- Seiffert-Brockmann, J., T. Diehl, and L. Dobusch. 2018. “Memes as Games: The Evolution of a Digital Discourse Online.” New Media & Society 20 (8): 2862–2879. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444817735334.

- Shifman, L. 2014. Memes in Digital Culture. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Spitzberg, B. H. 2014. “Toward a Model of Meme Diffusion (M3D).” Communication Theory 24 (3): 311–339. https://doi.org/10.1111/comt.12042.

- Wilson, C. 2022, May 10. “The Greems”: How the Greens harnessed online chaos to power a digital campaign. Crikey. https://www.crikey.com.au/2022/05/10/australian-greens-social-media-federal-election/.