Abstract

J.-J.-L. Graslin, an ‘anti-economist’, who fundamentally criticized physiocratic doctrine, and N. Baudeau, described as a ‘blind enthusiast’ of Physiocracy, started an open controversy in journals over the value of the processing industry in 1767. The purpose of this paper is to clarify the historical significance of their short-term controversy and Graslin’s far-sighted subjective theory of value confronting Physiocracy. As with other physiocrats, Baudeau insisted on the sterility of industry because it does not produce any net product. Baudeau argued that the value of a processed product was composed of two values: the value of materials and that of food for labour. By contrast, Graslin maintained that the value of labour must be considered separately from the value of food for labour. According to Graslin, labour that processes raw materials generates new value beyond the value of those materials, in the same way that agricultural labour generates value; therefore, the former type of labour is not sterile. The controversy symbolizes a preliminary confrontation between the upcoming cost theory of value and the subsequent subjective theory of value. On the latter, Graslin produces a table similar to Carl Menger’s table of needs satisfaction.

1. Introduction

This paper highlights the Correspondence (Baudeau and Graslin Citation1777)1 between J.-J.-L. Graslin2 and N. Baudeau3 and discusses their differing views on the value of the processing industry. As a result, it becomes clear how Graslin’s subjective theory of value was confronted with the powerful doctrine of Physiocracy promoted by F. Quesnay and other physiocrats including Baudeau. Furthermore, Graslin will be recognized as one of the most remarkable contributors to the development of subjective theory of value.

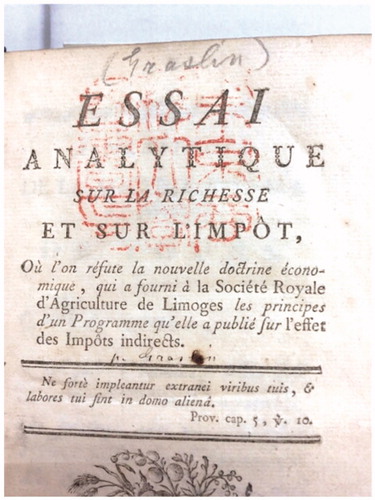

Graslin, a receveur général (tax officer general) in Nantes, was ‘the harshest critic of Physiocracy’ (Schumpeter Citation1954, 175).4 Graslin definitely denied physiocratic doctrine in his Essai Analytique sur la richesse et sur l’impôt (Analytic Essay on Wealth and Tax, 1767).5 Essai Analytique was written to propose the introduction of a progressive consumption tax against the physiocratic impôt unique (single tax) that was imposed only on agricultural products. As theoretical groundwork, Graslin developed the subjective theory of value and regarded not only land products but also processed industrial products as taxable wealth. It was necessary to increase tax revenue to rebuild given the severe fiscal situation at that time. However, the physiocratic doctrine inequitably narrowed taxable objects depending on the taxation on landlords’ net product. The physiocrats emphasized that industry is sterile because it does not produce any net product, whereas Graslin claimed that industry also produces net product, and that every product and every labour should be valued similarly based on need and scarcity. Thus, Graslin revealed an inconsistency in the physiocratic tax theory from a subjective viewpoint in his Essai Analytique.

After being criticized by the physiocrats, Graslin sent a letter to the editors of the Commerce Gazette (Commerce Newspaper) to justify his proposal, and publicly demanded an explanation for the physiocratic proposition concerning the so-called sterility of industry. This letter started an open controversy between Graslin and Baudeau over the sterility of industry. The Correspondence consists of their five letters: Graslin’s first letter, Baudeau’s first reply, Graslin’s second letter, a lawyer’s (Baudeau’s second) reply, and Graslin’s third letter.

Baudeau was a strong supporter of Quesnay and Graslin described Baudeau as a ‘blind enthusiast’ (Correspondence, 26). In fact, Baudeau had been an opponent of Physiocracy. He switched his thought from ‘anti-physiocracy’ to ‘pro-physiocracy’ in 1766 (Clément and Soliani Citation2012, 29), then devotedly promoted the physiocratic doctrine symbolized in Quesnay’s Tableau économique. Physiocrats called themselves ‘economists’ and believed that their doctrine was the only valid economic theory, that is the true Science économique. Graslin was called an ‘anti-economist’ and a ‘distinguished adversary against the science’ by Baudeau (Correspondence, 8).

Graslin and Baudeau’s retorts in the journals and the newspapers were provoked by Baudeau’s insult in his first reply. Baudeau supported the sterility of industrial production, quoting from L’Ordre naturel et essential des sociétés politiques (The Natural and Essential Order of Political Societies, 1767) by P.-P. Le Mercier de la Rivière. Their argument through the five letters in the Correspondence ended up without compromise.

Graslin’s subjective theory of value in Essai Analytique also affected A. R. J. Turgot’s Valeurs et monnaies (Value and Money, Citation[1769]1919) which has been considered to be one of the most far-sighted contributions to the theory of subjective value. However, Turgot contributed to the promotion of physiocratic doctrine by underscoring the sterility of industry in his Les Réflexions sur la Formation et la Distribution des Richesse (Reflections on the Formation and Distribution of Wealth Citation[1766]1914, section 17).

Some studies recognize Graslin’s Essai Analytique as a pioneering work in classical economics (Desmars Citation[1900]1973; Faccarello Citation2008, Citation2009), a forerunner of Ricardo (Dubois Citation1911, ix), of Walras’s equilibrium theory (Orain Citation2006, 964), and of Veblen’s division between the propertied class and working class (Maherzi Citation2008, 21). Furthermore, Graslin is considered to be a neo-mercantilist in the same way as Melon and Forbonnais (Dubois Citation1911, xix). Hutchison (Citation1988) recognizes Graslin as being a contributor to the subjective theory of value.

From another viewpoint, it is certain that Graslin’s value theory can be considered as a forerunner of C. Menger’s work in respect of its specific insights concerning the idea of marginal utility, which will be described later in this paper. Along with this point, it should also be emphasized that the Correspondence is a typical example of the contemporary conflict between the physiocrats and their opponents. Hitherto, however, the Correspondence has not been clearly exposited.

Following the above introductory observations, the bulk of this paper explains the controversy between Graslin and Baudeau over the value of industry in the Correspondence and discusses how Graslin’s subjective theory of value confronted that influential doctrine. Section 2 focuses on the background of the Correspondence. Baudeau and some like-minded advocates played a leading role in the promotion of the physiocratic doctrine through different works, journals, and newspapers. Section 3 discusses the essence of the five letters in the Correspondence and exposits their arguments over the value of labour in processing industries. Section 4 elaborates on Graslin’s subjective theory of value, which was the basis of his argument, and compares it with the theories of Turgot, Galiani, and Menger. Section 5 concludes with some general remarks.

2. Background of the Correspondence

This section provides an overview of the circumstances surrounding the controversy between Graslin and Baudeau. Physiocracy originated from Quesnay’s philosophy of the ‘natural order’ and elaboration of the Tableau économique, and rapidly expanded its influence after 1758.6 The physiocrats promoted an agriculture-oriented policy and a single tax on land products. Their policies included the deregulation of trade and traffic, the abolition of trade privilege, and the disbandment of guilds. Hence, the interests of the privileged class conflicted with these physiocratic policies.

The physiocrats formulated ‘a clear strategy’ to change ‘the policy of the Kingdom and even the shape of the French monarchy as a whole’ (Orain Citation2015, 350). Moreover, the physiocrats worshipped Quesnay much like a religious leader, and called him the ‘European Confucius’ or ‘Contemporary Socrates’. Indeed, D. Hume7 wrote to A. Morellet8 about the physiocrats’ overweening worship of Quesnay.9 There were some key advocates of Quesnay’s physiocratic doctrine. V. R. Marquis de Mirabeau first became a zealous advocate of Quesnay in 1757 through Mirabeau’s own L’Ami des hommes (Human Friend, 1756–60), which maintained fiscal reconstruction through an increase in the farm population. Quesnay’s Tableau économique10 was disseminated by Mirabeau’s annotation in L’Ami des hommes (Citation1761). Mirabeau then published Théorie de l’impôt (Tax Theory, Citation[1760]1761) and Philosophie rurale (Rural Philosophy, Citation[1763]1764) in which he proposed a single tax on land products. Graslin, in his Essai Analytique, often criticized Mirabeau’s assertion.

The physiocrats utilized their own journals to promote their doctrines. P. S. Dupont de Nemours, another key advocate of Quesnay,11 began to publish the Gazette du Commerce (Commerce Newspaper, 1763–83) and the Journal d’agriculture, du commerce et des finances (Agriculture Commerce Finance Journal, 1765–83). Meanwhile, Baudeau issued Éphémerides du Citoyen (Citizen Ephemeris, 1765–72), and Dupont de Nemours joined in editing it from 1768. Furthermore, Turgot edited the Nouvelles Éphémerides Économique (New Citizen Ephemeris, 1774–76).

It was in 1766, the same year as the publication of Turgot’s Les Réflexions, that Turgot encountered and reviewed Graslin’s Essai Analytique. Turgot himself held an essay competition, hoping for all applicants to submit papers faithful to Physiocracy. However, Graslin’s paper offered a criticism of Physiocracy. In 1767, two physiocratic books, targeting Graslin, were published in succession: Baudeau’s Exposition de la loi naturelle (Exposition of the Natural Law) and Le Mercier de la Rivière’s L’ Ordre naturel et essential (The Natural and Essential Order). Shortly afterwards, Graslin sent his first letter to the editors of the Gazette du Commerce to raise a question about a statement in Le Mercier de la Rivière’s L’Ordre naturel et essential. Graslin’s letter appeared in the Gazette du Commerce issued on 22 August 1767. Baudeau replied to Graslin in Éphémerides du Citoyen, vol. 9, in 1767 instead of Le Mercier de la Rivière. This was the beginning of a heated exchange between Graslin and Baudeau. Subsequently, Graslin published Essai Analytique in November 1767.

3. Controversy between Graslin and Baudeau over the Value of Industrial Production

This section exposits the five letters in the Correspondence in the sequence in which they were written. Graslin’s first letter has a sense of propriety; Baudeau’s reply is written in an assertive manner. The argument descended into a bitter exchange.

3.1. Graslin’s First Letter

Graslin pointed out the inaccuracy of a statement in Le Mercier de la Rivière’s L’Ordre naturel et essential. Graslin cited Le Mercier de la Rivière’s assertion that the value of food being consumed by a weaver would be replaced by the value of the weaver’s output following the processing of that weaver’s labour, as explained below:

Weaver buys food and clothes for 150 livres [pounds], and some flax for 50 livres that he sells as linen for 200 livres; it is equal to the sum of its costs. Someone says this worker quadruples the first value of flax in this way. Not at all, he only joins a foreign value that is the value of everything he necessarily consumed to this first value. These two accumulated values form not the value of flax, for it does not exist anymore, but what we can name the necessary price of the linen. Price represents by this means, 1. The value of 50 livres for flax, 2. The value of 150 livres accounts for other consumed products. (Correspondence, 4–5)12

In response to this physiocratic passage, Graslin claimed that the value of food and clothes consumed by the weaver should not be directly replaced with the value of the weaver’s output or labour, for there existed two different 150-livre values: one was the value of the food and clothes consumed by the weaver, and the other was the value of his output. Graslin elaborates as follows:

That the worker consumed a value of 150 livres, and that the labour of the worker, who transformed the flax into linen, produced another value of 150 livres, in other words, increased 150 livres over the value of the flax … no one can lead the matter to another conclusion except that there existed two values, completely different from each other, 150 livres each, and one of those is the fruit of the weaver’s labour. (Correspondence, 6)

Thus, Graslin emphasized the existence of two different values: the value of the weaver’s subsistence and that of the weaver’s labour which created the product.

3.2. Baudeau’s Reply

Baudeau replied to Graslin in Éphémerides du Citoyen, vol. 9, in 1767, where Baudeau was the chief editor. In his reply, he called Graslin an ‘avowed adversary against the science’ and an adversary in ‘a distinguished place among anti-economists’. Moreover, he stated, ‘Mr. G who brags that he does not dread the disgraceful anathema’ (Correspondence, 8).

Baudeau denied that labour produces new value, using a long quotation from Le Mercier de la Rivière’s L’Ordre naturel et essential. According to Baudeau, farmers produce everything they and others use and consume, and they also have their own products to exchange for conveniences, though artisans must purchase materials and food, which farmers produce, to provide energy for their labour. Industry is sterile because products produced by processed labour consist only of the materials for products and food for artisans’ consumption without any surplus. By distinguishing between sterile and productive in this manner, Baudeau denied that a product such as linen had a value by itself (12–13).13 Thus the ‘price is just the sum of several values consumed and added, however, to add is not to increase’ (10). Furthermore, Baudeau accused Graslin of supposing the existence of equivalent products every year, despite the fact that it did not conform to Graslin’s idea. To support this argument, Baudeau reasserted the original fertility of agriculture and claimed that the more workers consume materials and food, the more they produce (14–15). Finally, Baudeau cynically advised Graslin to study the ‘true elemental principles of economics’ because Graslin’s position ‘was far from the true elementary principles of the Science économique’ (15).

3.3. Graslin’s Second Letter

In response to Baudeau, Graslin contributed his second letter to the Journal d’agriculture, du commerce et des finances, November 1767, and justified his earlier points promoting the value of industry. In opposition to the physiocratic opinion that the value of linen over raw flax is necessarily regarded as the value of food consumed by the weaver, Graslin reiterated his three points concerning the weaver.

The partial value that exceeds the raw flax’s value in linen is quite distinct and independent from the value of the food the worker consumes.

These two values separately and entirely enter the system of wealth.

One of these values is the fruit of the worker’s labour. (Correspondence, 19–20)

Based on the above, Graslin explained the value of industrial labour: A worker’s labour for the value of 150 livres is indispensable for processed linen, since the flax can serve as a good that fulfils our needs only after being processed (24). The labour input is the object of the purchaser’s enjoyment from one side and the only means of the worker’s livelihood from another side. The worker obtains his food, first, by an exchange of his labour for his wage or an exchangeable product and, second, by another exchange of the wage or the exchangeable product for food. In other words, the worker offers a value for another value (25–6). Thus, industrial labour has value. Moreover, the value of 150 livres, which he exchanges for his labour, is not necessarily equal to the actual value of his food if he needs less food than the value of 150 livres. The worker can exchange the rest of the value of 150 livres for other goods. Therefore, it is not correct that industrial labour is sterile due to the replacement of its value with food.

In addition, Graslin advanced some key propositions.

The values of things are not inherent in themselves, nor dependent on their correlative.

All wealth or all means to pay do not necessarily come from agriculture.

Industrial production is wealth as well as farm production.

It is not necessarily true that only an increase in the net product from land causes an increase in the wealth of the State.

The net product does not circulate from one class to another.14

The Tableau économique is only sophistry.

Every tax should not be imposed exclusively on landowners.

Therefore, the physiocratic tax recommendation would be one of the most dangerous policies the government could ever adopt. (Correspondence, 28)

Moreover, Graslin suggested that Baudeau should not call any adversary an anti-economist but anti-Quesnéiste or anti-Miraboliste. Opponents of Physiocracy should be able to disagree and protest without being considered enemies of economics (29–30).

3.4. Mr Treillard’s Letter

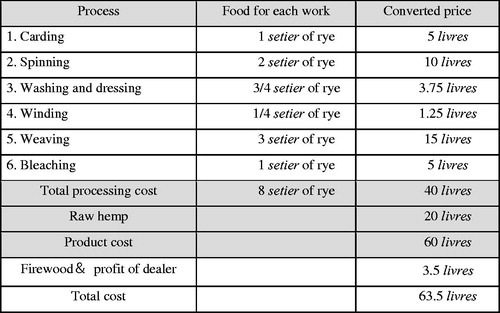

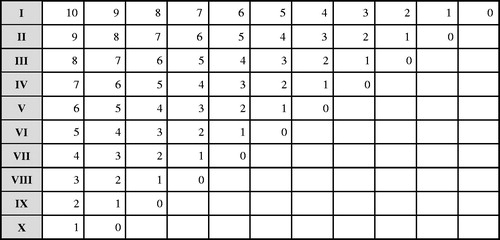

The next letter that objected to Graslin’s letters is from Mr Treillard, a lawyer in Limousin. It was published in Éphémerides du Citoyen by Baudeau in January 1768. Treillard maintained that industrial labour adds nothing to the value of raw material by showing the details of how rye was used to pay for labour processing activity to make ‘his’ hemp cloth, converting 1 setier into 5 livres,15 as below (33–4) ().

Treillard claimed that he could obtain his hemp cloth, for he had 8 setiers of surplus rye valued at 40 livres for workers’ food. He regarded nature’s blessings as abundant and argued that the value of his hemp cloth consisted of the value of workers’ food and of raw material.

Baudeau remarked on Graslin’s misunderstanding again at the end of this letter.16

3.5. Graslin’s Third Letter

In response to Treillard and Baudeau, Graslin’s long letter in the Journal d’agriculture, du commerce et des finances which was published in March 1768 proved that Treillard recognized only the value of 60 livres altogether. Treillard regarded the value of hemp cloth as the sum of the value of raw hemp and of rye. However, Graslin found there the value of 100 livres: the 20 livres value of the raw hemp, the 40 livres value of processing labour and the 40 livres value of the rye. Workers who exchange labour with rye will exchange rye for something else if they do not want to consume all the rye (46). Therefore, Graslin pointed out that the value of labour should not be replaced with the value of food.

At that time the physiocrats proposed a liberalization of wheat exports, even though domestic workers did not get enough food. Physiocratic argument rested on nature’s bounty and on the premise that labour had only the value of food. Graslin was concerned that this premise would be grounds for workers getting little food without any surplus. That was the prime reason why he submitted his opinions to scholarly journals. Graslin blamed the physiocrats for their ignorance of the miserable circumstances of workers. ‘Look at our farmland and the lower class in our town, you should see if this right to have their livelihood is not terribly restrained already’ (60). Finally, Graslin maintained that the export of grain and raw materials, which disadvantaged domestic industry, deprived workers of their livelihood, and weakened national competitiveness. It was important to sustain domestic industry since industry produces new value.17

Graslin’s Essai Analytique and the controversy over Physiocracy were almost forgotten thereafter. However, Graslin’s subjective theory of value at the time contained some innovative ideas. The next section discusses Graslin’s value theory presented in his Essai Analytique.

4. Graslin’s Subjective Theory of Value

Graslin’s Essai Analytique consists of two parts: wealth and tax. The former serves as logical groundwork for the latter. Graslin’s plan for a progressive consumption tax is founded on his contention that the upper classes, whose fortune is untaxed, should pay more tax than workers on low incomes. Moreover, he intended that not only the upper classes but also foreign visitors should pay the consumption tax, for they are avid consumers (170). Four features of his value theory in Essai Analytique are detailed below.

First, Graslin divides value into two kinds: direct value (individual absolute value) and relative value. Relative value represents the ratio of the direct values of two agents in an exchange. Wealth is defined as ‘every object with relative value according to the degree of need and scarcity’. Furthermore, the ‘term need (besoin) represents desire, utility, taste, pleasure; all qualities that form different degrees of need’ (Graslin Citation[1767]1911, 13–14). His distinctive point on value is that the value of any wealth increases or decreases independently of ‘cost’. Cost never increases the value of goods. Value is basically caused only by need and scarcity. In addition, scarcity is the dominant component of the value of wealth compared to need or desire (12, note 1). Consequently, Graslin’s value theory is not based on ‘cost value’ nor ‘labour cost value’, although a worker exchanges his labour for a wage or reward. The worker’s labour is wealth, and has a relative value based on need and scarcity, in the same way that the value of a product is determined according to the need of the purchaser and the scarcity of the product.

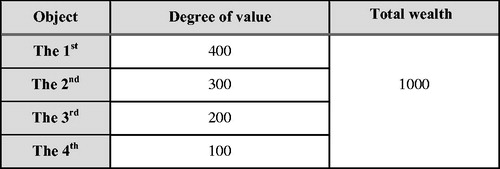

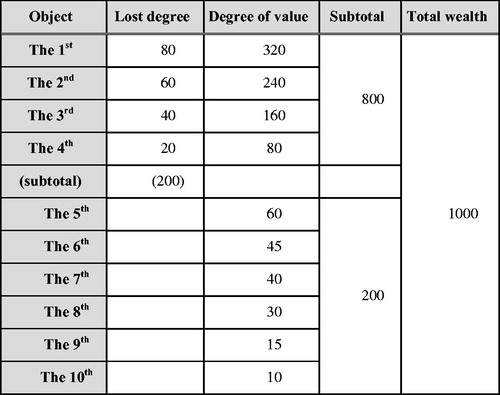

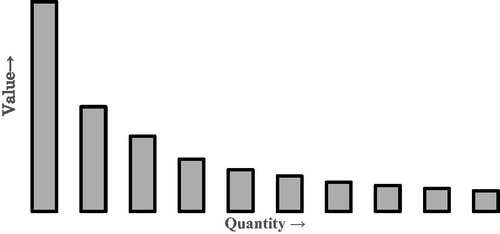

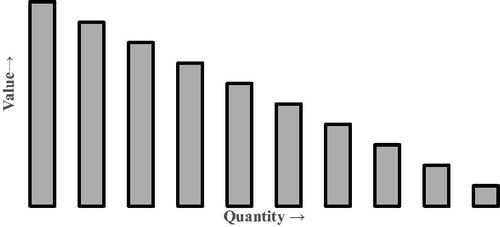

Second, based on the above principle, Graslin proposes a normative ‘wealth order’ whereby he graded wealth according to the degree of need for life. Graslin laid out the ‘wealth order’ in two tables: one showed the distribution of value degrees within four objects in a primitive society, while the other shows a similar distribution within ten objects in a civilized society (20).18 I shall call these two ‘Graslin’s tables’, and respectively.

With these tables, Graslin demonstrates how an increase in the number of objects affects each value. This idea is closely connected with the next point: a proposed human capacity for self-awareness of these different values.

Third, Graslin considers that luxury goods, which ranked low in the ‘wealth order’, may become more valuable than necessities, if the need or scarcity of luxury goods increases. He also assumes that a human capacity for self-awareness of different needs is always constant in both ‘primitive’ and ‘civilized’ societies (18–19, note). In other words, a simultaneous awareness of all needs is impossible, since everyone has a limited capacity for awareness of wealth based on need and scarcity. Accordingly, total needs, total wealth, and total value in the ‘wealth order’ correspond with each other proportionately. Therefore, awareness of individual needs will be weaker in a ‘civilized’ society than in a ‘primitive’ society, for there is a limited capacity for awareness of wealth as it spreads to different needs for many objects.

For instance, if a man has nothing to be able to satisfy his premier need, namely food, his only desire is to obtain food, and it is the only relevant wealth item for him. Once he has enough food, his desire changes to the pursuit of conveniences and luxury goods. Wealth for him is now not only premier needs but also includes conveniences and luxury goods. Since everyone has a limited capacity to be aware of needs, the more needs and desires they hold, any premier needs will become less intense (16, 21). This leads to the numerical difference in ‘degree of value’ between and .

Fourth, Graslin argues that value changes along with the quantitative change in the object:

The value of each thing will decrease proportionately, as the quantity of this sort of thing increases … The partial value of this thing must absolutely decrease according to the increase of the number of parts … When a muid of wheat19 doubles, a muid of wheat will have only half the value. Furthermore, it will similarly decrease the value, relative to the parts of other objects, while total wheat retains the same relationship of value in the wealth order. (Graslin Citation[1767]1911, 14–15)

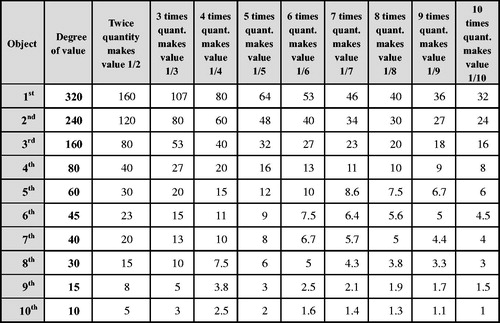

Thus, this passage implies his recognition of inverse proportional change in value relative to quantitative change in the object. His argument bears some primitive resemblances to the idea of diminishing marginal utility. It should be stated that Graslin did not mention the terms ‘additional’ or ‘marginal’,20 which is generally used as a term in marginal utility theory.21 Graslin’s words ‘as the quantity of this sort of thing increases’ and ‘when a muid of wheat doubles’ are not the same as ‘additional quantity’ in the strict sense. However, when his intention of inverse change in value relative to quantitative change in the object is taken literally, and when his words ‘when a muid of wheat doubles, a muid of wheat will have only half the value’ are taken into consideration, Graslin’s table 2 () can be developed into .

results in the expression of a similar idea, which is akin to ‘Menger’s table’ (Menger Citation[1871]1968, 93), even though the numerical values in differ from . It should be noted that Menger in fact possessed Graslin’s Essai Analytique (see Appendix). The figures in Menger’s table are interpreted as ordinal (Hayek Citation1934, 401; Hutchison Citation1953, 141). In restricting Menger’s table to integer values ‘it cannot be maintained that Menger conceived of satisfactions or marginal satisfactions in terms of infinitesimal magnitudes, as is the hallmark of a full-blown marginalist approach’ (Endres Citation1997, 29).22 Not only Menger but also Graslin occupies a position that is a long way from a pure marginalist approach.

A point of difference between Menger and Graslin is that Graslin’s table is based on the idea of cardinal utility. The difference between Menger’s table and Graslin’s table is depicted in and , in which Graslin’s table is hyperbolic in contrast to linearity in Menger’s table. Integer values in Menger’s table serve as both the order of values and abstract degrees of value and are consistent with ordinal utility. However, considering that the same integer values in Menger’s table indicate the identical degree of utility among different goods, as Menger explained, it would be difficult to eliminate the possibility that Menger had assumed cardinal utility. In contrast to this difficulty, numerical values in Graslin’s table concretely illustrate the proportional change according to quantity of the object. Thus, numerical values in Graslin’s table are cardinal.

As has been mentioned above, Graslin’s approach is certainly far from the pure marginalist-mathematical approach in the late nineteenth century. However, Graslin indeed offers the opinion that ‘economics is to have accuracy and demonstration like mathematics’ (Graslin Citation[1767]1911, 37 note). Nonetheless, Graslin tried to quantify value by assuming that human capacity to perceive one’s own needs is always constant. The quantified value is based on the idea is close to future ‘marginal utility’. Moreover, it is noteworthy that Graslin’s assumption about human capacity corresponds to the concept of total utility. Hence, it follows that Graslin discusses ‘value’ and ‘capacity’ as ‘marginal utility’ and ‘total utility’ respectively.

5. Conclusion

Despite Graslin’s dissent from physiocratic doctrine, the influence of Physiocracy expanded after the Correspondence. Baudeau was in the vanguard of its propagation with Dupont de Nemours. In 1776, the appearance of Smith’s Wealth of Nations and the downfall of Turgot heralded the decline of Physiocracy. However, physiocratic cost and capital theories are to some extent compatible with the next classical economics.23 Indeed, a critical appreciation and review of Physiocracy helped to initiate classical economics.

Graslin formulated a rudimentary framework of subjective theory of value linked to marginalist economics. This occurred before Turgot alluded to the subjective value concept in Valeurs et Monnaies.24 Graslin’s value theory is fundamentally distinguished also from Forbonnais (Citation1767) and Condillac (Citation1776), which only partially criticize physiocratic theory. However, Graslin’s pioneering subjective theory of value would be eclipsed by the shadow of Physiocracy and Smith’s labour theory of value thereafter. The controversy between Graslin and Baudeau represents, as it were, a preliminary confrontation between the subjective theory of value linked to marginalist economics from the late nineteenth century and the cost theory of value linked to Physiocracy and more so to classical economics from the late eighteenth century.

Acknowledgements

This paper was presented at the 2018 Conference of the History of Economic Thought Society of Australia in Perth, hosted by the University of Western Australia and Curtin University. I really appreciate the warm comments at the conference, helpful advice from the anonymous referees, and kind support from the editors.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Eiko Yamamoto

Eiko Yamamoto, Ph.D. in Economics from Waseda University in March 2020.

Notes

1 It has a long title: Correspondance entre M. Graslin, de l’Académique de S. Pétersburg, Auteur de l’Essai Analitique sur la Richesse & l’Impot. Et M. l’Abbé Baudeau, Auteur des Ephémérides du Citoyen. Sur un des Principes fondamentaux de la Doctrine des soi-disants Philosophiques Économistes (Correspondence between Mr. Graslin, St. Petersburg Academy, Author of the Analytic Essay on the Wealth and the Tax. And Mr. Father Baudeau, Author of Citizen Ephemeris. On one of the Fundamental Principles of the Doctrine of the so-called Philosophical Economists).

2 Jean-Joseph-Louis Graslin (1727–90) was born in Tours. After finishing his education for the legal profession in Paris, he started his career in Saint-Quentin. He was assigned to be the Parliament barrister and tax officer general in Nantes in 1758. Graslin’s economic studies mostly appeared between 1766 and 1768. He is known as a contributor to the development of Nantes and the Loire basin (Citation[1768]2008).

3 Nicholas Baudeau (1730–92) was born in Amboise. He joined the abbey in Périgord at the age of 20 and then became a canon regular. He moved to Paris in 1758, and then wrote papers on public finance and poverty, which were his concerns. Baudeau converted to Physiocracy in 1766 probably because he believed that the physiocratic idea of the natural order would defeat poverty. These circumstances surrounding his participation with the physiocrats are explained in detail in Clément and Soliani (Citation2012, 30–1).

4 ‘Graslin’s reputation was never what it should have been because he put so much emphasis upon criticism of the physiocrats – which is in fact the best ever proffered – that his readers were apt to overlook his positive contribution. Actually, his Essai Analytique presents the outlines of a comprehensive theory of wealth as a theory of total income rather than of income net of all producers’ expenses including wages – a not inconsiderable improvement considering the role the latter was to play later on. Also he was above his contemporaries in insight into the problem of ‘incidence of taxation’ (Schumpeter Citation1954, 175). ‘His correspondence with Baudeau is of considerable interest’ (175, footnote 7).

5 Graslin’s Essai Analytique was submitted to the prize essay contest organized by the Royal Society of Agriculture of Limousin, adjudicated by Turgot, Intendant of Limousin. The subject of the competition was ‘the effect of consumption tax on the proprietor’. Turgot as a referee criticized Graslin’s controversial views, since Graslin’s Essai Analytique was not in line with Physiocracy (Turgot Citation[1767] 1914).

6 In that year Quesnay’s Tableau économique was published.

7 David Hume (1711–76) stayed in Paris from 1763 to the beginning of 1767 and had contact with physiocrats.

8 Abbé André Morellet (1727–1819) was a physiocrat, however, he kept a certain distance from enthusiastic partisans. He translated Smith (Citation1776) into French and left a prospectus for the planning of a new commerce dictionary (1769).

9 ‘I see, in your leaflet, you don’t care to disoblige your economists … I expect that, in your work, you would strike them by lightning, squash them, crush them, and reduce them to dust and ash! They are the strangest and the most arrogant group among those who exist today after the annihilation of the Sorbonne’ (letter from Hume to L’abbé Morellet – 10 July 1769) (Hume Citation1888, 183–8).

10 Tableau fundamental (1758). Later, Tableau abrégés (1763) and Tableau formule (1766) were issued.

11 Dupont de Nemours argued the effect of free trade in line with the physiocratic policy in his De l’exportation et l’importation des grains (Citation1764). He edited Quesnay’s works and titled it Physiocratie (1768).

12 Graslin cited this from Le Mercier de la Rivière Citation[1767]1910, vol. 2, 403, chapter 43 titled ‘The industry is not productive at all: demonstration of this truth’.

13 Graslin did not claim that the processed linen had a value by itself.

14 Graslin’s intention with this point seems to be that the net product attributed to each class or sector cannot be substituted for another net product.

15 Setier is an old volume unit of grain.

16 Baudeau ‘has been depicted as the zealous prototype of the disciple … However, all too often we forget that, before becoming one of Quesnay’s apostles, this [Baudeau’s] exalted mind was a staunch opponent of physiocratic doctrine … He [Baudeau] was the champion of the rural lifestyle, not the defender of agricultural capitalism. Nor was he the promoter of free trade as in the physiocratic theory’ (Orain Citation2015, 355). For all the above observation, Baudeau seems to ‘defend the orthodox ideas of Quesnay’ in Correspondence.

17 The opinion of F. Galiani, which opposes the liberalization of the international grain trade, in Dialogues sur le commerce des blés (Citation1770), basically conforms to Graslin’s.

18 For instance, ‘the 1st’ is food, ‘the 2nd’ is clothes, ‘the 3rd’ is dwelling, ‘the 4th’ is farming implements in a primitive society, then, objects from the 5th to the 10th represent conveniences and luxuries.

19 A muid of wheat is equivalent to around 1,872 litres.

20 The word ‘marginal’ was first introduced by P. H. Wicksteed in his Alphabet of Economic Science in 1888 (Howey Citation1972, 297). The term was not used even in the 1870s. Howey focuses on the marginal concept from the nineteenth century and consequently does not recognize Graslin’s Essai Analytique in the eighteenth century.

21 The above discussion naturally leads to an examination of its relationship to Turgot, who is considered to be one of the most significant contributors to utility theory. In Valeurs et monnaies ([1769]1919), Turgot explains that once hungriness is satisfied, a man will become aware of another need in the next grade:

When the savage is hungry, he values a piece of game bird rather than the best bear skin; but, when his appetite is satisfied and he feels cold, it will be the bear skin that becomes valuable to him. (Turgot [1769]1919, 85)

Turgot explains that a new need arises after the satisfaction and the saturation of a previous need, showing his recognition of Graslin’s Essai Analytique. However, Turgot uses the concept of ‘saturated need’ and ‘subsequent need’ similar to F. Galiani’s discussion, whereby ‘as soon as a desire is settled, another desire stimulates man with the same intensity’ (Galiani Citation[1751]1803, 61).

22 ‘Menger nowhere concerned himself with ascertaining relative maximum values of total satisfaction, or minimum values of marginal satisfaction’ (Endres Citation1997, 30).

23 Clément and Soliani (Citation2012) suggest that Baudeau’s approach to capital and capital formation was quite unorthodox, since he applied the physiocratic approach to surplus in agriculture. Landlords were considered to belong to a capitalist category as long as they provide advances to agriculture (30).

24 While Turgot criticized Graslin’s Essai Analytique (Turgot Citation[1769]1914), he would not have written Valeurs et monnaies without reference to Essai Analytique.

References

- Baudeau, N. 1767. Exposition de la loi naturelle. Amsterdam/Paris: Chez Lacombe.

- Baudeau, N., and J. J. L. Graslin. 1777. Correspondance entre M. Graslin, de l’Académique de St. Pétersburg, Auteur de l’Essai Analitique sur la Richesse & l’Impot. Et M. l’Abbé Baudeau, Auteur des Ephémérides du Citoyen. Sur un des Principes fondamentaux de la Doctrine des soi-disants Philosophiques Économistes. London/Paris: Chez Onfroy.

- Clément, A., and R. Soliani. 2012. ‘The Work of Nicolas Baudeau: Original and Unappreciated Thought.’ History of Economics Review 56 (1): 29–55. doi:10.1080/18386318.2012.11682199.

- Condillac, É. B. 1776. 1970. Le Commerce et le Gouvernement. Genève: Slatkine Reprints.

- Desmars, J. [1900]1973. Un Précurseur d’A. Smith en France. Paris/New York: Société Anonyme du Recueil Général des Lois et des Arrêts et du Journal du Palais: B. Franklin.

- Dubois, A. 1911. Introduction. In Essai Analitique sur la Richesse et sur l’Impôt, edited by J. L. Graslin, v–xxx. Paris: Paul Geuthner.

- Dupont de Nemours, P. S. 1764. De L’exportation et de L’importation des grains. Soissons/Paris: P.G. Simon. doi:10.1086/ahr/15.2.375.

- Dupont de Nemours, P. S. 1768. Physiocratie, ou, Constitution Naturelle du Gouvernement le Plus Avantageux au Genre Humain. Leyde/Paris: Chez Merlin.

- Endres, A. 1997. Neoclassical Microeconomic Theory: The Founding Austrian Vision. New York: Routledge.

- Faccarello, G. 2008. ‘Galimatias simple ou galimatias double?’ In Sur la Problématique de Graslin, edited by P. Le Pichon and A. Orain (dir.) , 89–125. Rennes: Presses universitaires de Rennes.

- Faccarello, G. 2009. ‘The Enigmatic Mr. Graslin. A Rousseauist Bedrock for Classical Economics?’ The European Journal of the History of Economic Thought 16 (1): 1–40. doi:10.1080/09672560802707399.

- Forbonnais, F. V. d. 1767. Principes et Observations Économiques. Amsterdam: Chez Marc Michel Rey.

- Galiani, F. [1751]1803. ‘Della Moneta.’ In Scrittori Classici Italiani di Economia Politica, edited by P. Custodi, vol. III. Parte Moderna. Milano: Destefanis.

- Galiani, F. [1770]1984. Dialogues sur le Commerce des Bleds. Paris: Fayard.

- Graslin, J. J. L. [1767]1911. Essai Analitique sur la Richesse et sur l’Impôt. Paris: Paul Geuthner.

- Graslin, J. J. L. [1768]2008. ‘Dissertation de Saint-Petersbourg.’ In Graslin Le temps des Lumières à Nantes, edited by P. Le Pichon and A. Orain (dir.), 295–317. Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes.

- Hayek, F. A. v. 1934. ‘Carl Menger.’ Economica 1 (4): 393–420.

- Howey, R. S. 1972. ‘The Origin of Marginalism.’ History of Political Economy 4 (2): 281–302. doi:10.1215/00182702-4-2-281.

- Hume, D. 1888. Oeuvre Économique, edited by L. Say. Paris: Guillaumin.

- Hutchison, T. W. 1953. A Review of Economic Doctrine, 1870–1929. Oxford: Clarendon.

- Hutchison, T. W. 1988. Before Adam Smith. Oxford and New York: Basil Blackwell.

- Maherzi, D. 2008. ‘Introduction.’ In Essai Analitique sur la Richesse et sur l’Impôt, edited by J. J. L. Graslin [1767, Réédition du text de 1911]. Paris: L’Harmattan.

- Menger, C. [1871]1968. ‘Grundsätze der Volkswirtschaftslehre.’ Gesammelte Werke. Bd. 1. Tübingen: J. C. B. Mohr.

- Mercier de la Rivière, L. [1767]1910. L’Ordre Naturel et Essential des Sociétés Politiques. Paris: Paul Geuthner.

- Mirabeau, V. R. d. [1760]1761. Théorie de l’impôt. Avignon: Coordonnées et Noms des Responsables.

- Mirabeau, V. R. d. 1761. L’Ami des Hommes, ou, Traité de la Population. 6 vols. Avignon: Coordonnées et Noms des Responsables.

- Mirabeau, V. R. d. [1763]1764. Philosophie rurale, ou, Économie générale et politique de l’agriculture, t. 1–3. Amsterdam: Les Libraires associés.

- Orain, A. 2006. ‘“Équilibre” et Fiscalité au Siècle des Lumières, d’Économie Politique de Jean-Joseph Graslin.’ Revue Économique 57 (5): 955–981. doi:10.3917/reco.575.0955.

- Orain, A. 2015. ‘Introduction on the Difficulty of Constituting an Economic Avant-Garde in the French Enlightenment.’ European Journal of Economic Thought 22 (3): 349–358. doi:10.1080/09672567.2015.1026113.

- Schumpeter, J. 1954. History of Economic Analysis. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Smith, A. 1776. 1976. ‘An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations.’ In The Wealth of Nations, edited by R. H. Campbell and A. S. Skinner, vol. I. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Turgot, A. R. J. [1766]1914. ‘Les Réflexions sur la Formation et la Distribution des Richesses.’ In OEuvres de Turgot, edited by G. Schelle, vol. II, 533–601. Paris: Alcan.

- Turgot, A. R. J. [1767]1914. ‘Observation sur les mémoires récompensés par la Société d’Agriculture de Limoges, 1. Sur les Mémoires de Graslin, 2. Sur les Mémoires de Saint-Peravy.’ In OEuvres de Turgot, edited by G. Schelle, vol. II, 630–665. Paris: Alcan.

- Turgot, A. R. J. [1769]1919. ‘Valeurs et monnaies.’ In OEuvres de Turgot, edited by G. Schelle, vol. III, 79–98. Paris: Alcan.

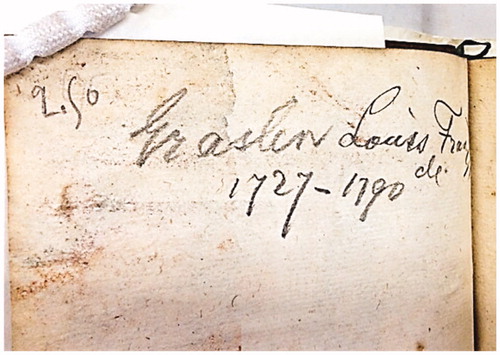

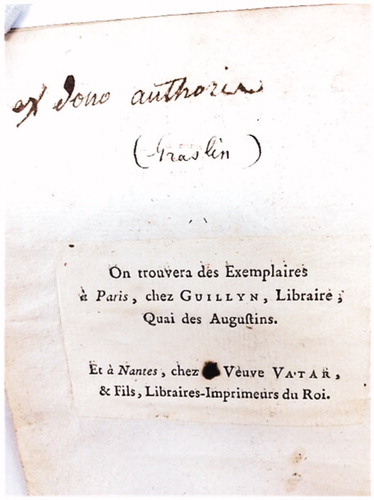

Appendix

Menger was possessed of Graslin’s Essai Analytique. Currently, part of Menger’s library is in the ‘Carl Menger Collection’ in Hitotsubashi University (Tokyo, Japan). We can find slight annotations, including Graslin’s name and lifespan, on the back of the front cover and on the inside cover of the book (See ). These annotations seem to be in Menger’s handwriting because of the close similarity with annotations in his other books held in the Collection. Doubtless, Menger was fully aware of Graslin’s Essai Analytique and familiar with its contents.