ABSTRACT

Getting to and from campus matters, especially for students who have relocated from regional and remote (RR) areas who must wrangle, often for the first time, rigid mass public transportation (MPT). Little is known about MPTs’ influence on RR students’ retention intentions or how MPT interacts with other known geographic proximity barriers. Interviews with ten equity practitioners from three Australian universities revealed four interconnected themes. First, MPT access and accessibility can limit university participation. Second, MPT provides a time benefit, enabling study while commuting. Third, relocation anxieties interact with MPT as accommodation further from campus requires greater MPT usage. Fourth, parents are concerned about MPT access and accessibility which adds to other “mixed messages” that they give their children, affecting participation. Efforts that address MPT access and accessibility may improve RR higher education retention and educational outcomes.

Introduction

In Australia, and many other countries, university qualifications enable upward social mobility (Marginson & Yang, Citation2021). Students from regional and remote (RR) locales in Australia are formally identified as an equity group, but despite efforts to increase their participation and retention in higher education, they remain under-represented. With a growing gap between RR educational outcomes and that of their metropolitan peers, RR under-representation is a cause for concern (Napthine, Graham, Lee, & Wills, Citation2019).

RR Australians typically fall into more than one equity group as they experience overlapping disadvantages (Napthine et al., Citation2019). According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (Citation2018a, Citation2018b, Citation2018c), 10% of the population live in RR communities, many of whom are Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and/or from low socioeconomic (LSES) backgrounds. RR university students are typically first-generation students (Nelson et al., Citation2017). RR students have much to gain from a university qualification; however, the further a student lives from a metropolitan area, the lower the expectation is that they will go to university (Zacharias et al., Citation2018). Despite efforts by equity practitioners, distance remains a barrier to RR students’ university aspirations and participation (Zacharias et al., Citation2018). Consequently, people from RR areas are less likely to attend and complete university (Napthine et al., Citation2019).

Many RR individuals desire a university experience but abandon their aspirations as the geographic proximity creates barriers to participation that, for many, are seemingly insurmountable (Regional Development Australia, Citation2012). Known geographic proximity barriers include relocation from home and connections to home. Home (or family home) is the current home address of a dependent student’s parent/s or guardian/s or the address where an independent student lived six months before they commenced university (Australian Government, Citation2021). The costs related to relocating include accommodation and living expenses, time costs related to commuting from accommodation to university and psychological costs such as experiencing anxiety and homesickness due to sacrificing connections to home; and for Indigenous students, the loss of cultural connections (Nelson et al., Citation2017).

Transportation is critical to overcoming the geographic distance between accommodation and university for relocated RR students. However, the research around MPTs’ influence on RR student retention is limited. Some research suggests that MPT poses a safety risk to university participation among RR students (see Gale et al., Citation2010; Russell-Bennett, Drennan, Kerr, & Raciti, Citation2016), while other research highlights the lack of familiarity with using MPT (Wilks & Wilson, Citation2012). This research addresses one of the many gaps in the literature and is framed by the research question: How does MPT impact the university retention intentions of Australian RR students and interact with relocation from home and connection to home geographic proximity barriers?

Literature review & theory

Social cognitive theory

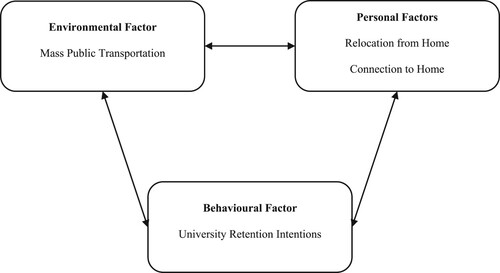

Bandura’s (Citation1989) Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) was used to organise the literature review and conceptual model. SCT views human behaviours in terms of a holistic model showing the interplay between environmental, personal, and behavioural factors (Bandura, Citation1989). SCT has been used in higher education and equity research to help contextualise how geographic proximity barriers inhibit students’ achievement of their university goals (Sogunro, Citation2015). This research uses SCT to explore how MPT (the environmental factor), as well as relocation from home and connection to home (personal factors), influence RR students’ university retention intentions (the behavioural factor), as shown in .

Mass public transportation

Transportation choice is a SCT environmental factor. In Australia, MPT and motorised private transportation are the most popular modes of commuting (Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development, Citation2016). MPT usage rates are lower in RR locales due to inadequate MPT infrastructure (Currie, Citation2010). MPT is defined as state government-funded transportation networks which follow a set route and schedule (Queensland Government, Citation2020). One in eight Australians uses MPT for their daily commute, with 65% occurring on heavy rail, 30% occurring on buses and 5% occurring on ferries or light rail (DIRD, Citation2016). MPT is also a preferred method of transportation among university students in other nations (Danaf, Abou-Zeid, & Kaysi, Citation2014) and impacts students’ quality of life (Gim, Citation2020).

MPT usage is influenced by access, being commuter-based factors, such as being familiar and competent with using MPT, and accessibility being transport system-based factors, such as scheduling and routes (Murray, Davis, Stimson, & Ferreira, Citation1998). When commuters can use MPT (access) and MPT satisfies their needs (accessibility), commuters consider it a viable choice (Murray et al., Citation1998). Commuters also consider fare affordability, time sacrifices, personal and possessional safety, and previous user experience when selecting transportation modes (Moreno-Monroy, Lovelace, & Ramos, Citation2018). Inaccessible MPT forces part-time or online university participation (Fleming & Grace, Citation2017), and in the United Kingdom (UK), it affects participation, retention intentions and success in compulsory education (Moreno-Monroy et al., Citation2018).

MPT affordability matters. In the UK, it was found that as MPT costs increase, higher education participation intentions decrease (Kenyon, Citation2011). Despite commitments to invest in Australian MPT ridership, few strategies have successfully addressed the rising costs and impracticality of MPT in RR areas (Li, Dodson, & Sipe, Citation2018). Australian MPT concession “smart cards” have made commuting somewhat more affordable for university students (Liu, Wang, & Xie, Citation2019). Although these concessions subsidise MPT fares for RR students, MPT infrastructure is typically located in gentrified areas instead of in-need RR communities (Liu et al., Citation2019). As a result, RR communities experience low MPT access and accessibility (Currie, Citation2010).

Safety risks are also a significant barrier to MPT use (Delbosc & Currie, Citation2012). Ethnic minorities and women fear being targets of abuse either during their commute (Gardner, Cui, & Coiacetto, Citation2017). A higher security presence on MPT has had some success in alleviating these fears (Gardner et al., Citation2017). However, security remains a concern for commuters, especially in the evening (Delbosc & Currie, Citation2012). Safer, high quality MPT infrastructure matters to university students as MPT has been connected to lower academic confidence (Ellis, Rowley, Nellum, & Smith, Citation2018).

Relocation from home

Relocation from home is a SCT personal factor. Australians prefer face-to-face, on-campus study (Napthine et al., Citation2019; Stone, O’Shea, May, Delahunty, & Partington, Citation2016). RR university campuses typically offer a limited range of courses, and some only offer the first year of study, requiring students to relocate to complete their degree (Napthine et al., Citation2019). Given the geographic size of Australia and the small population spread mostly along the eastern seaboard, relocating for university is a significant undertaking for about one-third of RR students (Cardak et al., Citation2017; Zacharias et al., Citation2018).

Relocation involves financial costs, logistical processes, and psychic costs such as worry and stress, which lead many students to either not apply, defer, allow their university offers to elapse, or “satisfice” by changing their university or course preferences to match courses available at nearby campuses (Zacharias et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, RR students are less likely to secure or afford on-campus accommodation, relegating them to cheaper rental accommodation that is geographically distant from campus that, in turn, requires them to navigate unfamiliar MPT, incur greater MPT expenses and spend more time commuting (Fleming & Grace, Citation2017).

Demographic factors play an important role in cultivating relocation decisions. Harvey, Burnheim, and Brett (Citation2016) noted that the influences of age, gender and socioeconomic status affect whether prospective RR students will relocate to attend university. Non-school leavers, which includes mature-age students, are less likely to relocate than school leavers (Harvey et al., Citation2016). This may be attributed to younger applicants’ desire for independence (Napthine et al., Citation2019) or older applicants’ responsibilities (Stone et al., Citation2016). Male applicants are less likely to apply for local universities than female applicants, which is related to the emphasis on female-targeted course offerings provided by RR campuses (Harvey et al., Citation2016).

In terms of socioeconomic status, the financial cost of relocation is prohibitive for RR students and even more so for those from LSES backgrounds (Cardak et al., Citation2017). Beyond the initial move, ongoing living costs and sundries on top of study-related expenses place LSES students under constant financial pressure (Cardak et al., Citation2017). Despite the expansion of government-funded relocation support, students still require a supplementary income (Napthine et al., Citation2019). The National Centre for Student Equity in Higher Education (Citation2017) reported that without parental financial support, school leaver RR students need to work at least 18 h each week as government welfare is insufficient. Working students struggle to balance work and study, adversely affecting their participation and retention intentions (Norton & Cherastidtham, Citation2018).

Connection to home

Connection to home is a SCT personal factor. Those from RR communities typically possess strong family, community and cultural attachments that impact their post-school choices (Napthine et al., Citation2019). The decision to relocate to university means that these important ties change; indeed, some connections are severed (Zacharias et al., Citation2018). For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, many of whom live in regional or remote locations (ABS, Citation2018b), the need to maintain connections to family, culture and community is critical to their well-being and their educational attainment (Smith et al., Citation2018). Thus, attending university for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians involves significant socio-cultural sacrifices (Smith et al., Citation2018).

Connection to home matters to RR Australians because, as Napthine et al. (Citation2019) posited, individuals, particularly young people, value opportunities within their communities more greatly than opportunities offered elsewhere. Regional Development Australia (Citation2012) also noted the importance of high social connectedness the exists in RR settings, describing the benefits that flow when residents give and receive help from friends, family and peers. Importantly, RR high school students’ value high social connectedness and associate metropolitan communities with low social connectedness (Schmidt, Citation2017). Hence, high school students recognise that relocating for university will mean that not only will they lose their strong connections, but it is unlikely that they will build connections in their new, metropolitan community (Smith et al., Citation2018).

Prospective RR students fear not only being isolated from home-based support networks but also experiencing loneliness as they realise it will be harder to make friends in a metropolitan environment (Smith et al., Citation2018). The parents of prospective RR students also recognise the impact of the loss of connection to home and some may not support or hesitate to support their child’s decision to relocate for university (Drummond, Halsey, & van Breda, Citation2011; Russell-Bennett et al., Citation2016). In response to these concerns, some prospective RR students change their course choices to those accessible at closer, RR campuses while others will abandon their career aspirations altogether (Gore et al., Citation2017; Napthine et al., Citation2019).

Retention intentions

This research is concerned with the influence of MPT on the university retention intentions of RR students. Retention intentions is a SCT behavioural factor. The literature on retention is voluminous as the reasons why students leave university are complex and largely the result of a combination of personal circumstances and institutional factors (Napthine et al., Citation2019). Metropolitan students are more likely complete their degrees (72.9%) than those from regional (67.7%) and remote (61.5%) areas (Parliament of Australia, Citation2022). Some of the reasons why RR students leave university include the experiencing of financial hardship, much of which is associated with relocation, social, and geographic isolation linked to breaking or changing connections to home, and low academic achievement due to factors such as the need to work, caring responsibilities, not feeling like they belong, and low academic confidence (Cupitt, Costello, Raciti, & Eagle, Citation2015; Parliament of Australia, Citation2022).

Improving the retention intentions for RR students is paramount for university equity practitioners. Upward social mobility and social justice outcomes hinge on RR students completing their studies (Napthine et al., Citation2019). Many RR students who leave university are burdened with both debts and regrets (Norton & Cherastidtham, Citation2018).

Methods

With little known about the influence of MPT on Australian RR students’ university experience, a qualitative approach provided the opportunity to explore the complexity of the context and identify patterns (Braun & Clarke, Citation2013). In-depth interviews conducted with “expert proxies”. As noted by Raciti, Eagle, and Hay (Citation2016), equity practitioners are exceptional “expert proxies” whose expertise is rarely tapped despite them being well-positioned to not only observe the experiences of equity students and their families and communities over time but also to interact directly with students across the full spectrum of their academic journey.

A semi-structured format comprised of probing questions adapted from the literature review (Napthine et al., Citation2019), such as: How do RR students perceive their home communities? What challenges do you think exist for students considering using public transport to reach campus? Do the challenges differ for RR and metropolitan students? In the interviews, the expert proxies were asked how the experiences of RR students differed from metropolitan students.

This research was approved by the University of the Sunshine Coast’s Ethics Committee, Approval Number S191353. Ethical requirements were adhered to. To ensure anonymity, pseudonyms have been allocated to each participant when reporting the findings. In-depth interviews were conducted one-on-one, over the telephone to enable participation by equity practitioners in remote locations and were 30–40 min in duration. Interviews were conducted by the primary researcher, digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim by a commercial transcription organisation. Notes were also taken by the primary researcher throughout the in-depth interviews.

Sampling and sample

Using a non-probability, purposive sampling approach, 24 Australian equity practitioners, who were part of the professional network of the second author, were contacted seeking their participation in the research. Non-responders (n = 13) were contacted twice via email and invited to participate. One non-participant, who declined the invitation citing time constraints, recommended another practitioner who was subsequently interviewed.

Ten experienced practitioners from three Australian universities participated in the research. Two of these three Australian universities are classified as Regional Universities and are headquartered in RR areas. University #1 has six campuses of which five are in RR areas, University #2 has three campuses of which two are in RR areas and University #3 delivered to four regional and four metropolitan locales. Nine of the 10 practitioners in this research were located at RR campuses and shared insights about the students they work with on these RR campuses. The one metropolitan-based practitioner coordinated a large equity programme delivered to four regional locales which they regularly visited. RR student representation was important in the equity strategies of each university. The sample was skewed by gender with one male participant and nine female participants. The demographic profile of participants, such as age or gender, were not key criteria for selection because participants were interviewed as proxies to share their observations and experiences with RR students. That is, this research was about the RR students they worked with, not about the practitioners themselves. Anecdotally, most practitioners are female hence the gender skew did not raise concerns about bias in the responses.

Data analysis

Manual thematic analysis was conducted by the primary researcher in the first instance and then by the other members of the research team as per Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2013) guidelines. Digital recordings and transcripts were used to triangulate the findings among the research team, which met several times to discuss the data before reaching agreement on the final themes. In this article we report the distinct experiences of RR students as observed by expert proxies.

Findings

Four interconnected themes emerged from the data. First, MPT access and accessibility can limit university participation. Second, MPT provides a time benefit, enabling study while commuting. Third, relocation anxieties interact with MPT as accommodation further from campus requires greater MPT usage. Fourth, parents are concerned about MPT access and accessibility which adds to other “mixed messages” that they give their children, affecting aspirations and participation.

Theme 1: MPT access and accessibility

Participants regularly commented on the inflexible nature of MPT and its implications for students commuting between accommodation and campus. RR students were described as at the mercy of MPT as they must organise themselves around MPT and study timetables, reducing their control or freedom regarding time spent on campus. MPT accessibility impeded student abilities to attend lectures and tutorials or participate in extracurricular activities and acted as a barrier to participation, negatively impacting the retention intentions of RR commuters. The barriers posed by MPT accessibility are even more pronounced for RR students with disabilities.

There are other people [with disabilities] where I know they just don’t come to university [and disengage] because they don’t know a transport route or can’t find their own independent transport (Angel).

The negative impact of low MPT flexibility was more noticeable among RR students who commuted greater distances. Furthermore, MPT access barriers included safety concerns, primarily at night when MPT facilities are closing. Students attending evening and night classes and those who live distantly were more thoughtful of safety risks due to the longer time commitment required to commute late at night. MPT usage also prevents involvement in extracurricular and social activities that were related to an improved sense of belonging and friendships, as well as academic performance and confidence:

I’ve had students … who I’ve had to let go early because the last bus going back down to Brisbane left at like six pm on a Friday … That’s another issue when there’s not enough public transport, to the extent that it cuts into a students’ classes. (Lyna)

Students who have to commute and have to commute an hour or more each way will normally leave earlier and so, therefore, have less exposure to some of the added benefits of coming to university. (Hexis)

I would say that in urban areas it’s [MPT] probably a bit riskier for women and people of different sort of ethnic backgrounds that there’d still be a bit of bullying and harassment that would go on (Nonna).

While students are eligible for discounted MPT fares, information about these discounts was thought to be hard to locate, reducing access. Indeed, information visibility emerged in the data, with participants noting that the inadequate visibility of student MPT fare discounts meant that many RR students were unaware of financial support that may assist in facilitating their engagement in university. I think they could be better informed [about MPT discounts] … I don’t think it’s that visible (Nonna). Participants noted that to mitigate MPT access and accessibility issues, RR students may disengage from on-campus activities and/or transition to more convenient but less preferred online learning delivery methods.

Theme 2: MPT time benefit

This research revealed that there are benefits to MPT use for RR students. Participants had observed that MPT offered RR students the opportunity to study during their commute, unlike others who drove themselves to campus. RR students used this time as an opportunity to catch up on course readings, lecture preparation and reflection and relaxation. This time benefit increases MPT accessibility and may improve the retention intentions of RR students providing space for valuable downtime.

[On MPT benefits] I think equally there’s other opportunities if someone wants to make a start on their reading, whether it’s on their device or hard copy. Yes, it can be a bit of downtime as well to reflect on your day (Angel).

Theme 3: relocating from home anxieties

Relocating from home is a known geographic proximity barrier; however, how it interacts with MPT is unknown. The need for relocated students to secure and maintain accommodation was a major source of anxiety for RR students. Participants noted that there were three types of university accommodation – on-campus accommodation (which is usually adjacent to campus), near-campus accommodation (which is usually a convenient distance from campus), and non-campus accommodation (which is usually an inconvenient distance from campus). Participants concurred that on-campus accommodation offered the greatest benefits. The further the accommodation was from campus, the greater were RR students concerns. Specifically, being rental properties, there was inherent insecurity about upholding and retaining leases and the further from campus the accommodation was, the fewer benefits of university life were available. When renting a unit or house, it can be a little more insecure, as we all know … I think that there’s great benefits, psychological and emotional benefits to be gained by moving into campus-based accommodation (Lyna). Lyna further explained on-campus housing, can be expensive. I suppose that financial expense needs to be weighed up with what’s affordable, but also the advantages, as I said before, of the stability and perhaps the camaraderie that can come with living on campus.

While participants presumed that securing on or near-campus accommodation was the best option for most students, financial and non-financial concerns were also identified as the cause of other student relocation anxieties. Whereas the financial considerations were about accommodation affordability, the non-financial concerns were related to the social and psychological challenges associated with living with strangers. I’ve come across kids who … express some concern … It’s not just starting university; it’s getting somewhere to live, it’s not knowing who you might live with, wondering about how you’re going to cope with your finances (Lyna). Trino added:

Those social challenges can create some issues often. We have had situations where we’ve found that those students have had to leave the student accommodation and find private accommodation because of those reasons.

I think sometimes the issues can take a while to play out, particularly if someone has a disability, particularly if it’s not a visible or a known disability. It might take a few weeks more, the barriers or difficulties to arise. (Angel)

Accommodation anxieties were ongoing throughout RR students time at university. Beyond initial costs to relocate, ongoing costs associated with accommodation were problematic. For RR students, ongoing relocation expenses were difficult to manage without financial support, such as government welfare or a supplementary income. Those unable to afford rent and core living expenses struggled and were often forced to seek paid employment during study:

A lot of these children … have to get jobs to afford accommodation. Then also, on top of that, they’ve got bills, electricity, internet, the normal day to day things that are taken for granted when you don’t have to relocate. (Octavia)

We recommend that students don’t work more than 15 hours a week because … if you’re studying full-time, you can’t really manage if it’s more than that. Some of them actually have to because they actually need the money to live on. (Hepper)

That pressing need of needing to turn up for a shift, and dedicate the time to getting your assignment done, they’re equally pressing. It does mean that sometimes something has to give. (Angel)

Often they’re moving … finance is a massive issue I would argue … Getting access to Youth Allowance [government welfare]. It doesn’t always come into effect until they start their study, and even then, it can take a little bit of time to actually hit their bank account. (Cubbie)

You’ve got your proactive students, which is probably only a small portion of the students which actually go and seek [financial] support … I think there is probably more needed to be done to communicate that there are options. (Decan)

Theme 4: mixed messages from concerned home connections

When asked about the social challenges associated with the RR transition to university, participants suggested that students often navigated competing voices from key influencers, such as parents. Prospective university students typically consult multiple sources to gather information and motivation, with the most important ranging from the social influence of peer groups, family and significant others to formal websites and contacts. These influencers rarely deliver consistent messages to RR students, adding confusion to the already difficult decision as to whether to go to university. Equity practitioners often had to “myth bust” incorrect messages and assure parents and other influencers:

It could be different messages that are coming through to young people … What their guardians or parents might say in relation to future pathways could be very different to what a university or a TAFE or another adult college might say. (Lyna)

Their [RR students] parents and their families and the role models in their life haven’t espoused – been to uni[versity] or particularly value university. So, you might be the black sheep if you want to go and not get supported. (Nonna)

For an Aboriginal student … You’ve got a senior Elder – an Elder who’s a member of the family talking to a young one saying well I don’t know why you’re bothering going to university. (Trino)

As I mentioned before about regional students coming down to the city, sometimes they’re actually scared about catching it, or they don’t know how to use the bus timetable or train timetable. (Hepper)

I have also heard of students that have never caught a bus before on their own and also, a student who has never caught a train before on her own and her mother … was very worried about that, that the daughter might get off at the wrong station or something might happen. (Hexis)

Discussion and conclusions

Equity practitioners in Australia has made much progress over the last decade in addressing the underrepresentation of RR students; however, this momentum needs to be maintained to address the educational divide between metropolitan and RR locales (Napthine et al., Citation2019). The four themes identified in this research provide insight into the role of MPT in the experiences of RR students in Australia. In other countries the link between MPT and higher education inequality has been examined (e.g. Kenyon, Citation2011). However, MPT has largely been overlooked in equity research in Australia, and this study is one of the first not only focused on MPT but also how it interacts with other known geographic proximity barriers to create a picture of the complex situations that RR students find themselves in. This research set out to address the research question: How does MPT impact the university retention intentions of Australian RR students and interact with relocation from home and connection to home geographic proximity barriers?

This research found that MPT impacts university engagement and the retention intentions of Australian RR students, concurring with overseas studies (Kenyon, Citation2011). The inflexible nature of MPT scheduling created challenges for RR students. RR students’ on-campus participation in classes and extracurricular activities were constrained by MPT scheduling and students felt they had less freedom to come and go from campus. Rigid MPT scheduling prevented RR students from having a full and enriching university experience and optimising their academic capabilities and learning. Over time, RR students become worn down by MPT constraints, leading many to reduce their engagement or disengage with their studies as the difficulty of reconciling MPT schedules with class timetables and work becomes too much to bear. This is particularly the case for those RR students who live further away from campus and must tolerate regular, long-distance commutes. The MPT benefit of providing time to study, reflect and relax either deteriorates over time or is simply not substantive enough to outweigh the financial, time, safety and psychological costs incurred by MPT usage.

Unlike the UK, Australian students have access to discounted fares (Kenyon, Citation2011). This research found it was a lack of information about MPT discounts and concessions exacerbated that financial concerns of RR students, many of whom were from LSES backgrounds. Particularly for those unaccustomed to MPT, information regarding financial assistance was perceived as invisible. Consequently, uninformed students were deterred from using MPT because of its unaffordability or felt coerced into paying greater MPT fares than what they would have otherwise been entitled to. This challenge is linked to geographic proximity as RR students tend to incur the greatest time-losses when commuting and are more likely to transfer during their commute (for example, between buses or switching between trains, buses, and ferries), which incurs additional expenses and stresses for inexperienced and unprepared RR students.

MPT safety concerns of both students and influencers at home were evident and influenced usage and added to mixed messages directed at RR students. Among Australian equity literature were hints that MPT posed a safety risk for RR students (Russell-Bennett et al., Citation2016). Like Kenyon’s (Citation2011) UK study, this research confirmed the presence of a perceived safety risk among RR students, especially for women and people from ethnically diverse backgrounds. MPT commuting at night after classes was considered particularly risky with concerns about physical or verbal abuse. As RR students felt vulnerable when using MPT, many cut short their time on campus by leaving classes early to avoid or reduce night commuting, impacting their academic performance, engagement, and retention intentions. The time benefit of MPT was immaterial in the light of safety risks.

Unlike studies conducted overseas (Kenyon, Citation2011) or in Australia (Delbosc & Currie, Citation2012), this research confirmed the presence and nature of MPT as a geographic proximity barrier that influences RR students’ university engagement and retention intentions. Also, this research identified the interaction between MPT and two other prominent geographic proximity barriers, being relocation from home and connection to home. While each of these three geographic proximity barriers influenced retention intentions individually, it was the interaction between all three that formed confounding and complex scenarios that profoundly impacted engagement and retention intentions.

To summarise, MPT plays an important role in the university participation of Australians from RR areas. Using social cognitive theory (Bandura, Citation1989), the findings of this research provide useful insights for equity practitioners as well as state governments who have carriage or MPT infrastructure. Universities are encouraged to work with the government to address MPT issues as a part of their suite of retention strategies related to the Napthine et al. (Citation2019) National Regional, Rural and Remote Education Strategy. Strategies, such as making information about MPT fare discounts clear to RR students, as well as highlighting the time opportunity benefit, may make the difference between a RR student deciding to complete their studies rather than leave university. This research provides a benchmark for future research that may explore the impact of COVID-19 MPT scheduling on RR student engagement and retention intentions. Different types of data from RR students, such as MPT journals and logs and interviews with RR students, are also encouraged. Replicating this study abroad would also yield useful insights.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). (2018a). Regional population growth, Australia, 2016–17. https://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/[email protected]/DetailsPage/3218.02016-17?OpenDocument

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). (2018b). Census of population and housing: Socioeconomic indexes for areas (SEIFA), Australia, 2016. https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/subscriber.nsf/log?openagent&SEIFA%202016%20Technical%20Paper.pdf&2033.0.55.001&Publication&756EE3DBEFA869EFCA258259000BA746&&2016&27.03.2018&Latest

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). (2018c). Estimates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, June 2016. https://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/[email protected]/DetailsPage/3238.0.55.001

- Australian Government. (2021). Services Australia: Family home location. https://www.servicesaustralia.gov.au/family-home-location-for-relocation-scholarship?context=22566#a1.

- Bandura, A. (1989). Human agency in social cognitive theory. American Psychologist, 44(9), 1175–1184. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.44.9.1175

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. London: SAGE Publications.

- Cardak, B., Brett, M., Bowden, J., Vecci, P., Bahtsevanoglou, B., & Mcallister, R. (2017). Regional student participation and migration. National Centre for Student Equity in Higher Education, Perth: Curtin University.

- Cupitt, C., Costello, D., Raciti, M., & Eagle, L. (2015). Social marketing strategy for low SES communities: Position paper. National Centre for Student Equity in Higher Education, Perth: Curtin University.

- Currie, G. (2010). Quantifying spatial gaps in public transport supply based on social needs. Journal of Transport Geography, 18(1), 31–41. doi:10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2008.12.002

- Danaf, M., Abou-Zeid, M., & Kaysi, I. (2014). Modeling travel choices of students at a private, urban university: Insights and policy implications. Case Studies on Transport Policy, 2(3), 142–152. doi:10.1016/j.cstp.2014.08.006

- Delbosc, A., & Currie, G. (2012). Choice and disadvantage in low-car ownership households. Transport Policy, 23(September), 8–14. doi:10.1016/j.tranpol.2012.06.006

- Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development (DIRD). (2016). Transport and Australia’s development to 2040 and beyond. https://www.infrastructure.gov.au/infrastructure/publications/files/trends_to_2040.pdf

- Drummond, A., Halsey, R., & van Breda, M. (2011). The perceived importance of university presence in rural Australia. Education in Rural Australia, 21(2), 1–18.

- Ellis, J. M., Rowley, L. L., Nellum, C. J., & Smith, C. D. (2018). From alienation to efficacy: An examination of racial identity and racial academic stereotypes among black male adolescents. Urban Education, 53(7), 899–928. doi:10.1177/0042085915602538

- Fleming, M., & Grace, D. (2017). Beyond aspirations: Addressing the unique barriers faced by rural Australian students contemplating university. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 41(3), 351–363. doi:10.1080/0309877X.2015.1100718

- Gale, T., Hattam, R., Comber, B., Tranter, D., Bills, D., Sellar, S., … Parker, S. (2010). Interventions early in school as a means to improve higher education outcomes for disadvantaged students. National Centre for Student Equity in Higher Education, Perth: Curtin University.

- Gardner, N., Cui, J., & Coiacetto, E. (2017). Harassment on public transport and its impacts on women’s travel behaviour. Australian Planner, 54(1), 8–15. doi:10.1080/07293682.2017.1299189

- Gim, T. (2020). The relationship between overall happiness and perceived transportation services relative to other individual and environmental variables. Growth and Change, 51(2), 712–733. doi:10.1111/grow.12380

- Gore, J., Ellis, H., Fray, L., Smith, M., Lloyd, A., Berrigan, C., … Holmes, K. (2017). Choosing VET – Investigating the VET aspirations of school students. Adelaide: National Centre for Vocational Education Research.

- Harvey, A., Burnheim, C., & Brett, M. (2016). Student equity in Australian higher education: Twenty-five years of a fair chance for all. Singapore: Springer.

- Kenyon, S. (2011). Transport and social exclusion: Access to higher education in the UK policy context. Journal of Transport Geography, 19(4), 763–771. doi:10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2010.09.005

- Li, T., Dodson, J., & Sipe, N. (2018). Examining household relocation pressures from rising transport and housing costs – an Australian case study. Transport Policy, 65(February), 106–113. doi:10.1016/j.tranpol.2017.03.016

- Liu, Y., Wang, S., & Xie, B. (2019). Evaluating the effects of public transport fare policy change together with built and non-built environment features on ridership: The case in South East Queensland, Australia. Transport Policy, 76(February), 78–89. doi:10.1016/j.tranpol.2019.02.004

- Marginson, S., & Yang, L. (2021). Individual and collective outcomes of higher education: A comparison of Anglo-American and Chinese approaches. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 20(1), 1–31. doi:10.1080/14767724.2021.1932436

- Moreno-Monroy, A., Lovelace, R., & Ramos, F. (2018). Public transport and school location impacts on educational inequalities: Insights from São Paulo. Journal of Transport Geography, 67(February), 110–118. doi:10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2017.08.012

- Murray, A., Davis, R., Stimson, R., & Ferreira, L. (1998). Public transportation access. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 3(5), 319–328. doi:10.1016/s1361-9209(98)00010-8

- Napthine, D., Graham, C., Lee, P., & Wills, M. (2019). National regional, rural and remote tertiary education strategy final report. Canberra: Australian Government.

- National Centre for Student Equity in Higher Education. (2017). Successful outcomes for regional and remote students in Australian higher education: Issues, challenges, opportunities and recommendations from research funded by the National Centre for Student Equity in Higher Education. National Centre for Student Equity in Higher Education, Perth: Curtin University.

- Nelson, K., Picton, C., McMillan, J., Edwards, D., Devlin, M., & Martin, K. (2017). Understanding the completion patterns of equity students in regional universities. National Centre for Student Equity in Higher Education, Perth: Curtin University.

- Norton, A., & Cherastidtham, I. (2018). Dropping out: The benefits and costs of trying university. https://grattan.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/904-dropping-out-the-benefits-and-costs-of-trying-university.pdf

- Parliament of Australia. (2022). Regional and remote higher education: A quick guide. https://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/download/library/prspub/8543739/upload_binary/8543739.pdf

- Queensland Government. (2020). 2019–2020 annual report. https://www.parliament.qld.gov.au/Documents/TableOffice/TabledPapers/2020/5620T1712.pdf

- Raciti, M., Eagle, L., & Hay, R. (2016). Social marketing strategy for low SES communities: Survey of expert proxies. National Centre for Student Equity in Higher Education, Perth: Curtin University.

- Regional Development Australia. (2012). Aspirations and destinations of young people: A study of four towns and their communities and schools in Central Hume, Victoria. School of Education and Arts, Ballarat: University of Ballarat.

- Russell-Bennett, R., Drennan, J., Kerr, G., & Raciti, M. (2016). Social marketing strategy for low SES communities. National Centre for Student Equity in Higher Education, Perth: Curtin University.

- Schmidt, M. (2017). “No one cares in the city”: How young people’s gendered perceptions of the country and the city shape their educational decision making. Australian and International Journal of Rural Education, 27(3), 25–38.

- Smith, J., Bullot, M., Kerr, V., Yibarbuk, D., Olcay, M., & Shalley, F. (2018). Maintaining connection to family, culture and community: Implications for remote aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander pathways into higher education. Rural Society, 27(2), 108–124. doi:10.1080/10371656.2018.1477533

- Sogunro, O. (2015). Motivating factors for adult learners in higher education. International Journal of Higher Education, 4(1), 22–37. doi:10.5430/ijhe.v4n1p22

- Stone, C., O’Shea, S., May, J., Delahunty, J., & Partington, Z. (2016). Opportunity through online learning: Experiences of first-in-family students in online open-entry higher education. Australian Journal of Adult Learning, 56(2), 146–169.

- Wilks, J., & Wilson, K. (2012). Going on to uni? Access and participation in university for students from backgrounds of disadvantage. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 34(1), 79–90. doi:10.1080/1360080x.2012.642335

- Zacharias, N., Mitchell, G., Raciti, M., Koshy, P., Li, I., Costello, D., … Trinidad, S. (2018). Widening regional and remote participation: Interrogating the impact of outreach programs across Queensland. National Centre for Student Equity in Higher Education, Perth: Curtin University.