ABSTRACT

Within cultural tourism, creative tourism is gaining popularity in international and domestic tourism. Primary research in creative tourism, however, especially from the point of view of consumers, is still in its infancy. Therefore, the aim of this article is to explore a niche market in creative tourism. Specifically, the demand for handicraft, and creative motivation, is researched using a quantitative consumer behaviour survey of 252 respondents carried out in Hungary in April and May, 2021. The survey examined the awareness and image of handicraft activities and workshops, as well as consumer behaviour related to these activities. Results contribute to deepening the knowledge of the market segment of creative tourism and, through this, new aspects are added to further studying and understanding rural development.

Introduction

Changes in tourism trends in recent years have led to a growing demand for tourism and recreation services from a wider range of people. Experience has shown that, in the twenty-first Century, the motivation for tourism is increasingly focused on the acquisition of experience and self-expression, and there is a general trend towards diversified services, both in traditional mass tourism and in destinations newly entering the tourism market (Ananzeh, Ismail, & Awawdeh, Citation2021; Coccossis, Citation2008; Kulcsár, Citation2015; Törőcsik & Csapó, Citation2021). In the context of international tourism trends, the progress and evolution of cultural tourism have created new supply and demand segments, resulting in the creation of additional niche products (Binkhorst & Den Dekker, Citation2009; Gonda, Citation2014). Effects of the rapid growth of cultural tourism in recent decades have been the diversification of tourism demand and the emergence of new and innovative forms of tourism within the general cultural tourism sector (Duxbury & Richards, Citation2019; Harcsa, Citation2017; Richards, Citation2002; Tan, Kung, & Luh, Citation2013).

Recent tourism trends include the rapid increase in the proportion of senior citizens, changes in family structure, the rise in overall level of education, and the demand for knowledge and skills; these can be linked to social and demographic changes (Csapó & Végi, Citation2021; Remoaldo et al., Citation2020). The vast majority of analysts of global tourism trends, until the emergence of COVID-19, agree tourism is undergoing a new type of growth and transformation, with social factors (the need for personalisation of offers and consumption patterns, due to the rise of individualism) as the main drivers, coupled with demographic (ageing societies and the parallel phenomenon of population explosion), economic, political, and technological (digitalisation, mobility, the relationship between experience and play, internet accessibility) changes (Lőrincz & Sulyok, Citation2017; Nagy, Csapó, & Végi, Citation2021; Nod, Mókusné, & Aubert, Citation2021).

One element of the conscious development of rural areas (Bakas & Duxbury, Citation2018; Keskitalo, Schilar, Cassel, & Pashkevich, Citation2021), and the (re)thinking of tourism, is the strengthening of the role of creative tourism (Richards, Citation2021; Vuin, Carson, Carson, & Garrett, Citation2016). To the best of our knowledge, both international and Hungarian research in this area is less focused, and a comprehensive survey of entrepreneurs and consumers offering craft activities as a service has not been carried out. Recognising this gap, the authors formulated the following research question: What is the role of handicraft and creative programmes in the demand and supply side of rural tourism and what are the most important consumer behaviour trends concerning these niche products? The research question is implemented in the research process by applying an exploratory online questionnaire survey targeting different groups of consumers in Hungary (where the authors work and research). We believe that this regional approach contributes to the international literature in order to better understand the subject by contributing to exploration of the demand side of craft activities and, in parallel, its implications for rural tourism development. The article first introduces the most important literature and theories, starting with creative tourism, and later focuses on handicraft and creative programmes. After this, the research methodology is explained by providing the research design and methods. Findings explain survey results using descriptive statistics and relationship analysis, while in the Discussion and Conclusion we draw the most important lessons from the results, provide research limitations and suggest future research directions.

Literature review & theory

Research about tourism attractions linked to crafts reveals tourism product types can be classified as niche products within cultural tourism, with creativity and culture linked (Li & Kovacs, Citation2021). Those working in creative industries (artists or professionals working in cultural/creative industries) are related to culture and cultural tourism (Palenčíková & Csapó, Citation2021; Pret & Cogan, Citation2019). Historically, creative tourism, as a product, is relatively new. Creative tourism is an example of tourism development and innovation that is an increasingly popular tourism trend paralleling socio-economic changes, especially in the developed world (Csapó, Citation2020; Törőcsik & Csapó, Citation2021). In the early 2000s, the transformation of cultural tourism led to Richard and Raymond first publishing a new approach to product innovation termed “creative tourism” (Richards & Raymond, Citation2000). Their definition of creative tourism is: “[…] tourism which offers visitors the opportunity to develop their creative potential through active participation in learning experiences which are characteristic of the holiday destination where they are undertaken” (Richards & Raymond, Citation2000, p. 18).

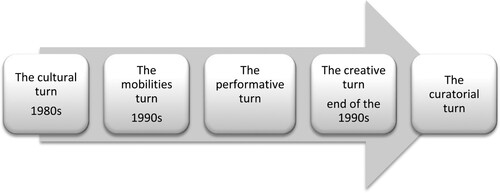

Since the 2000s, the terms “creative culture” and “creative tourism” have been used more and more widely in analyses of cultural tourism trends. According to the working definition of UNESCO (Citation2006), creative tourism is defined as, “travel directed toward an engaged and authentic experience, with participative learning in the arts, heritage, or special character of a place, and it provides a connection with those who reside in this place and create this living culture” (UNESCO, Citation2006, p. 3). Richards (Citation2021) divides the development of cultural tourism over time into stages ().

Figure 1. Stages in the development of cultural tourism from the 1980s to the present. Source: Richards (Citation2021).

According to Richards (Citation2021), the creative turn in cultural tourism dates back to the late 1990s, so the emergence and expansion of creative tourism in international tourism starts from the beginning of the twenty-first Century. The main driving force behind the emergence of creative tourism was the growing segment of tourists who wanted more authentic experiences than those offered by cultural and mass tourism during their travels. Looking at creative tourism from the demand side, “participation” and “authenticity” became keywords, including participation in different activities and the acquisition of authentic experiences (Sarantou, Kugapi, & Huhmarniemi, Citation2021; Virginija, Citation2016). This desire to know, and the need for involvement, require tourism destinations and service providers to offer increasingly authentic experiences (Ilincic, Citation2014; Tan, Kung, & Luh, Citation2014) to meet travellers’ demands to learn and have more authentic experiences.

In addition, a 2018 UNWTO (World Tourism Organisation of the United Nations) analysis highlights:

[…] the shift from observation to immersion in travel has, and will continue to, grow the understanding and appreciation of cultural tourism in its broader (symbiotically tangible and intangible) sense. This is magnified in emerging destinations (especially the Asian region) which offer, and are overtly positioning, culture as one of their key differentiators and reasons for superior experience delivery. Cultural Tourism allows destinations which may be lacking in hard infrastructure to compete not just effectively, but assertively and sustainably, with their soft infrastructure offerings, i.e. inviting culture, heritage and community (UNWTO, Citation2018, p. 51).

Growing international and national research on creative industries (media and advertising, film and video, publishing, music, performing arts, fine arts, applied arts, design and fashion, art and antique markets, crafts, architecture, software development, and digital game development) and creative tourism (Richards, Citation2020, Citation2021) reveals creative industries contribute substantially to sustainability and inclusive growth due to the diversity of its activities (e.g. IT, painting, crafts) (Michalkó & Lőrincz, Citation2007; OECD, Citation2006; UNCTAD, Citation2010; UNESCO, Citation2021).

Creative tourism-related developments can be found in three main areas: creative performances, creative spaces, and creative tourism products (Richards & Wilson, Citation2006). Services offered by craftspeople and creative professionals can be classified in the latter two categories (creative space and creative tourism products). These niche products focus on consumer preferences, such as experience-seeking, authenticity, and personalisation (Jászberényi, Citation2020). Sarantou et al. (Citation2021) emphasise the importance of identity-building, creativity, and storytelling through case studies from Finland and Namibia. Their findings show that, through the collaboration of creative professionals and the local community, creative tourism offers new tourism opportunities for destinations, provides longer-term livelihoods for creative service providers, and offers relevant experiences for tourists. Quantitative Portuguese research (Remoaldo et al., Citation2020) analysing tourists’ creative tourism motivations found visitors identified three characteristic clusters, “novelty seekers”, “knowledge and skills learners” and “leisure creativity seekers”. More recent research also identified cultural and creative industrial parks as a location for creative tourism (Chang & Hung, Citation2021). Highlights from research analysing the relationship between consumer values and consumer engagement related to consumer behaviour and creative tourism reveal the most recent research directions are using and explaining the role of big data or digital technologies (Hopkins, Citation2022; Kliestik, Zvarikova, & Lăzăroiu, Citation2022a) and artificial intelligence (Kliestik, Kovalova, & Lăzăroiu, Citation2022b; Nica, Sabie, Mascu, & Luțan (Petre), Citation2022).

The concept of “craftsmanship”, in the Hungarian context of cultural tourism, can be understood using Hungaricums. In this context, craftsmanship belongs to the group of “museums and landscapes” within the Hungaricums, emphasising folk character. The other approach is rural tourism. Rural tourism focuses on local traditions – building on the historical, cultural, and social characteristics of the settlement – craft products, craft activities, and demonstrations that are presented as attractions (Hungarian Tourism Agency, Citation2021). Further, some craft activities can be classified as “intangible cultural heritage” (National Committee of Intangible Cultural Heritage, Citation2023; Tóth, Citation2023). Hungarian literature has attempted to address the gastronomic side of handicrafts, such as Angler and Kóka (Citation2021), Minorics and Gonda (Citation2015), and Vas-Guld (Citation2021), which take a general approach to the relationship between handicraft food and its consumers. Conversely, Háló (Citation2021) analyses tourism implications of handicraft markets in a regional analysis context, while others analyse possible links and opportunities between crafts and tourism based on a single foodstuff (Angler, Citation2015; Füreder, Citation2019; Kerekesné & Kovács, Citation2017). Lastly, the Covid-19 pandemic severely affected the creative industries worldwide, including cultural service providers and creative professionals (Khlystova, Kalyuzhnova, & Belitski, Citation2022). The majority of creative industries, including craft-based services, did not show resilience to the COVID-19 pandemic, and self-employed and part-time creative professionals were particularly hard hit.

Methods

Research design

An online questionnaire survey was used to investigate the awareness and image of craft activities and workshops on the demand side, as well as consumer behaviour related to these activities. Areas explored were: associations, respondents’ (who used the services at least once in the last three years) opinions of concepts, and key issues (motivation, location, duration, consuming, price, number of people, and communication channel). Mixed-methods (qualitative and quantitative) were used to develop the questionnaire. First, a literature review was conducted to identify existing scales and measures of the constructs of interest (Remoaldo et al., Citation2020). Second, semi-structured interviews with Hungarian craftspeople, as experts in the field, were conducted to gain further insight into survey constructs and to identify any additional items. Based on this data, a customised questionnaire was made to create a pilot test that aimed to characterise the motivations and profile creative tourists.

There were four main forums and channels used to share the online questionnaire (through embedded online access): a professionally featured Facebook page, a professional news portal page, craftspeople sharing the survey in specific Facebook groups, as well as their sharing it among friends and acquaintances using the snowball method. In addition, several national professional organisations were invited to shar the survey with others, as were most of the craftspeople interviewed. The online survey was anonymous. Respondents completed questionnaires between 17th April and 23rd May 2021. illustrates the questionnaire questions. These are grouped according to the willingness to pay for craft occupations.

Table 1. Research variables and response categories in the research model.

The questionnaire also included questions excluded from the research model due to measurement on a nominal scale. In the demographics section, the respondent's gender, postcode, and whether they had a second home, or occupation. Additional questions related to craft activities were: What is the first thing that comes to mind when you think of crafts, craft activities, craft workshops, and craft camps? In your free time, how regularly do you do crafts or creative activities, and how often have you done so in the last 3 years? In what kind of company, with whom would you most like to do crafts outside your home (in a workshop)? Where do you get information about craft activities? Would you be willing to pay for a craft session if it was in person, or an online pre-recorded session that could be viewed at any time, or an online live session where you could get immediate professional help and feedback? Why would you recommend craft sessions to others? What suggestions for improvement do you have for the organisation of craft sessions? Are there any craftspeople whose sessions you would recommend? Although the survey's sample size (n = 252) is limited and not representative, and thus the research design is limited by the small consumer base, findings contribute to understanding consumer habits of those interested in creative tourism's craft programmes.

Data analysis

The questionnaires were processed using SPSS statistical software. Descriptive statistics and relationship analyses were used to analyse results. Descriptive statistics were used to generate frequencies and distributions (mode, mean, and relative standard deviation, where the average deviation of each response from the mean was expressed as a %). Using relationship tests, we looked for statements of the type “the more … , the more … ” among the closed questions measured on an ordinal scale. In , the arrow indicates the relationship between the variables to be explained and the potential explanatory variables, which is the main aim of the research. The research objective sought to identify if “willingness to pay” (the likelihood of participating in craft activities of a given price and duration) significantly influenced other variables. For the eleven types of craft sessions, of different cost and duration (2–3 h, 1 d, 2–5 days), respondents were asked whether they would attend the session. Relationship tests are interpreted at the 5% significance level (95% confidence level for the sample population). The Kendall's tau (τ) rank correlation coefficient, suitable for exploring relationships between questions measured on an ordinal scale, has a coefficient interval range of −1 to1, whereby the coefficient sign gives the direction of the relationship and its absolute value note the relationship strength. Tau lower than 0.2 can be interpreted as a weak relationship, tau of at least 0.7 indicates a strong one, and tau between 0.2 and 0.7 marks a moderate relationship (Sajtos & Mitev, Citation2007).

Findings

Descriptive statistics

Altogether 252 people completed the survey. Demographically, the majority of respondents (92%) were female. It is important to stress that the sample is not distorted in terms of gender because, in general, the vast majority of participants in craft activities are women. Most (83%) sellers on the Etsy website (a global marketplace for handmade goods) are women (Pengue, Citation2021). The greater interest and clear predominance of women was also reflected in the feedback from Hungarian craft service providers during the semi-structured interviews.

In terms of age, the largest proportion of respondents (32%) was aged 46–64, followed by those 19–24 (27%), 25–35 (20%), 36–45 (16%), 65 and over (4%), and 14–18 (1%). Two respondents gave a non-existent postcode and the remaining 250 respondents live in 103 municipalities. The majority (20%) came from the capital, Budapest. The remaining 80% of the respondents live in rural parts of Hungary. This reflects the distribution of the Hungarian population (about 9.7 million people). According to the Hungarian Central Statistical Office, 18% of Hungary's population lived in the capital on January 1, 2022 (HCSO, Citation2023).

Although craft sessions are available at respondents’ permanent and potential second residences (i.e. holiday homes), findings showed most (70%) respondents did not possess a second home. The most frequent household size was four people (27%), followed by two (25%), three (23%), five (12%), or alone (9%). The fewest (4%) lived in a household of six or more people. In terms of education, the majority (61%) had a higher education degree (college or university), and 38% had a secondary education. Only 1% of respondents had just primary education. None completed less than primary school. By occupation, most were employed in an intellectual occupation (30%), followed by students (28%), the self-employed (12%), middle or senior managers (6%), public employees (5%), freelance intellectuals (4%), and “inactive” occupations, such as previously being in childcare or child support, living on other income but not actively working (4%), manual workers (3%), the unemployed (3%) and those who worked while receiving a pension or other benefits (1%).

The main research question aimed to explore the awareness and demand for handicraft activities. Frequencies revealed the word “craftsman” did not conjure up the words “master craftsman”, “craftsman”, or “folk artist” for the majority, just anyone who makes a product by hand (78%). For “craft camp”, the majority associated the term with activities for children (66%) and “craft workshop” with activities for adults (77%). The majority (51%) couldn’t decide whether “craft activities” was for children or adults. Respondents typically participated in an organised craft activity in the last 3 years (58%), mostly doing a craft once a month (28%). Of the 28 types of craft sessions, the most popular was “wine and gastronomy” (baking, cooking, chocolate/candy making, barista training). Only 10% of the sample said they would not participate in one or more of these. The least popular was forging (53% refused this activity). The typical “willingness to travel” was 11–30 km for 2–3 h, 1 d, or 2–5 days of craft sessions. Respondents would like to do crafts with people with similar interests (70%) and find out about craft activities by browsing the internet (61%). A majority would be willing to pay – the lowest of the options offered – for both in-person and online sessions, whether pre-recorded or live. Out of the 23 criteria listed, the average respondent ranked the openness of the session leader as the “most important” element when choosing a craft session, as well as the effectiveness of his/her teaching, professionalism, knowledge, previous work, and references. The majority (80%) would recommend craft classes to others for the experience of creating and learning new techniques.

Relationship analyses

Analysing compulsory questions for the full sample (n = 252), the research model found the following did not significantly affect the likelihood of participating in craft activities of a given price and duration: their level of interest in specific occupations (straw and shoe making, basket weaving, furniture painting, jewellery making, doll and puppet making, sewing, knitting, crocheting, upholstery, mosaic making, beauty and cosmetics, musical instrument making) and the choice of craft occupations (the importance they attach to specific aspects and circumstances when choosing a craft activity: the quality and quantity of the materials used in the craft session, the equipment, tools, and comfort of the craft session venue, the cleanliness of the craft session venue, the hygiene conditions, the possibility of online payment (bank transfer), flexible cancellation (2–3 days before the session), expertise, knowledge, previous work, references of the facilitator, openness of the facilitator towards the participants, the effectiveness of the teaching, short film or video of the chosen craft session, possibility to filter between programmes by location, price, time and type of craft programme). shows explanatory variables that significantly affected response variables.

Table 2. Relationship test results: Kendall's tau (τ) coefficients.

Of the four main categories of explanatory variables (willingness to travel, interest, the importance of the selection criteria for the craft, and demographic characteristics) there was no single explanatory variable that strongly influenced “willingness to participate” in craft activities. shows a significant relationship (correlation) was found between “willingness to travel” and “willingness to pay”, and the strongest (moderate) relationships were also found for these variables. The further respondents were willing to travel for training, whether it is 2–3 h, 1 d, or 2–5 days, the more likely they were to attend training at a given price. Only weak rank correlations between people’s interest in certain crafts and their willingness to pay (the more interested, then the more likely they would attend training at a given price), were found. For the occupations researched were: leatherwork, felt making, wine and gastronomy: baking, cooking, chocolate/candy making, barista training, blacksmithing, painting: experience, silk, watercolour, pottery, bag making, calligraphy, photography, holiday related, woodcarving, weaving, embroidery, beadwork, quilting, and graphics. Those who were more likely to attend certain courses considered the following factors more important: to be able to book via a website, to participate in individual or medium (5–10 people) workshops, to work in small groups, to buy the raw materials on the spot, to make a booking on the app or by phone, to pay by credit card, that the person running the session is well-known and popular, the qualifications and diplomas of the person in charge of the occupation, to allow them to give feedback on their satisfaction. Those more likely to attend certain courses considered the following factors less important: the possibility to cancel the training the day before the session, the quality and usability of the work, and the existence of customer service. Only weak demographic relationships were identified. Respondents more likely to attend trainings (at various prices), the older they were, the larger their household, and the higher their level of education.

Discussion & conclusions

In recent years, the nature of the links between tourism and creativity has changed and extended, along with contexts for creative tourism. Research has kept pace with these developments by offering insights and reflections from a wide range of local and national contexts. Moreover, as Duxbury and Richards (Citation2019) highlights, in general, the research on creative tourism has progressed from identifying the emergence of creativity-based tourism activities to examining the motivations and behaviours of creative tourists, the nature of the creative tourism experience, the general types of organisations supplying creative tourism products, the relationships between tourists and their destination, and the impacts of this activity in the communities in which it occurs. The present article provided further insights into the research of consumer behaviour, connected to handicraft and creative programmes, by conducting an online survey in regional Hungary.

Alongside international literature (Duxbury & Richards, Citation2019; Ilincic, Citation2014), this research found that, as a form of creative tourism, craft activities can be carried out through a wide range of programmes. In support of related literature (Li & Kovacs, Citation2021; Palenčíková & Csapó, Citation2021), it found market-based craft programmes offer primary opportunities for creativity, self-time, and craft motivation, and are typically offered as a small (6–8 persons) guaranteed programme through the craftsperson's communication network. Craft activities, as part of creative tourism, can be understood as a tourist offering as well, furthering international literature (Keskitalo et al., Citation2021; Li & Kovacs, Citation2021). Based on related literature (Khlystova et al., Citation2022), and our findings about the “consumer side”, the most important factors when running craft programmes, courses, and workshops are good atmosphere, homeliness, safety, and comfort. An important aspect which reduces clientele’s stress is that no previous training or knowledge be required of guests participating in programmes. Further, craft courses with a small group character, limited participants, and the increasingly popular “individual sessions”, where the focus is on one person, were found desirable.

The most important factors when choosing a craft programme, as a creative tourism experience, are the openness of the craft leader, the effectiveness of his/her teaching, his/her expertise, knowledge, previous work, and references. The main characteristics of motivated clientele that may be open to crafts are that their occupation or profession is monotonous, responsible, and stressful; they tend to put others first in their work, doing support work; they are constantly working on reconciling work, family, and household obligations; and/or that they are overloaded, doing many tasks at the same time. Craft group guests chose a craft course to spend time with themselves, enjoy creating, try new techniques, experience creative energies, and/or gain experience (with friends, colleagues, and people with similar interests). The target group interested in craft programmes wants to experience the following feelings and experiences: stress relief, relaxation, a sense of achievement, relaxation, liberation, flow experience, energising, timelessness, relaxation, serenity, creative experience, more effective problem solving, more harmonious life, and/or liberated energy. Finally, guests and participants sought to learn new techniques, learn a hobby, make a wearable creation that can be used in everyday life, and/or make a unique handmade gift.

In concluding, this article has contributed research about the demand and supply characteristics of a less researched creative product of cultural tourism using quantitative methods. The research was primarily exploratory and collected data about a niche product of creative tourism that tourist destinations may benefit from developing further. Destinations’ attractiveness, and the range of programmes on offer, were significantly enhanced by craft programmes. Craft programmes provided a positive response to spatial and seasonal challenges of tourism. This is true for lesser-known destinations and the summer season, which is not the most popular in Hungary. Offering expansion also created employment and provided supplementary income for craftspeople and programme managers, who are typically women. Although the survey was not representative, results may increase understanding of consumer habits for those interested in craft programmes within creative tourism. To develop the supply range of creative tourism in rural areas, this research should be extended by researching the supply side, providing a complete presentation of service providers within a (quantitative) spatial distribution, and conducting an activity-based survey of craftspeople. Finally, market-oriented mapping and analysis of the demand side of craft programmes (e.g. awareness and image, willingness to pay, information acquisition, mobility) and including craft programmes in tourism and leisure offering for a given destination, are additional ways to expand creative tourism and its research.

Acknowledgment

The No. 142571 project was funded by the Ministry of Innovation and Technology with support from the National Research Development and Innovation Fund under the “OTKA” K_22 call programme.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Ananzeh, M. M. H., Ismail, A. I., & Awawdeh, A. (2021). Client perceptions of Emirati innovation strategy on service quality in UAE tourism sector. Rural Society, 30(2–3), 119–128.

- Angler, K. (2015). Kézműves borok – kérdőjelekkel. In Oroszi Viktor (Ed.), Szőlő, bor, turizmus: tanulmányok a szőlészet, borászat és borturizmus témaköréből. Pécs, Magyarország: Pécsi Tudományegyetem, 174, 18–34.

- Angler, K., & Kóka, B. (2021). Vonzza-e a kézműves élelmiszer a turistát? In Mezőfi, Nóra, Németh, Kornél, Péter, Erzsébet & Püspök Krisztián (Eds.), V. Turizmus és Biztonság Nemzetközi Tudományos Konferencia tanulmánykötet. Nagykanizsa, Magyarország: Pannon Egyetem Nagykanizsai Kampusz, 676 p., 114–124.

- Bakas, F. E., & Duxbury, N. (2018). Development of rural areas and small cities through creative tourism: The CREATOUR project. Anais Brasileiros de Estudos Turísticos, 8(3), 74–84.

- Binkhorst, E., & Den Dekker, T. (2009). Agenda for co-creation tourism experience research. Journal of Hospitality Marketing and Management, 18(2–3), 311–327.

- Chang, A. Y.-P., & Hung, K.-P. (2021). Development and validation of a tourist experience scale for cultural and creative industries parks. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 20, 100560.

- Coccossis, H. (2008). Cultural heritage, local resources and sustainable tourism. International Journal of Services, Technology and Management, 10(1), 8–14.

- Csapó, J. (2020). Exploring creative tourism as a new tourism product in Slovakia – Analysis of the primary results. Geograficke Informacie, 24(2), 28–42.

- Csapó, J., & Végi, S. (2021). Összefoglalás, elképzelések a világjárvány utáni időszak nemzetközi és hazai turizmusáról. In Csapó & Végi (Eds.), A globális, lokális és a glokális turizmus jelenlegi szerepe és jövője elméleti és gyakorlati megközelítésben. Pécs, Magyarország: PTE KTK Marketing és Turizmus Intézet, 145 p., 138–145.

- Duxbury, N., & Richards, G. (2019). Towards a research agenda for creative tourism: Developments, diversity, and dynamics. In N. Duxbury, & G. Richards (Eds.), A research agenda for creative tourism (pp. 1–14). Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing. ISBN 978-178-811-071-6. 8.

- Füreder, B. (2019). A kézműves, illetve a felső erjesztésű sörök és a fogyasztók egymásra találása napjainkban pár budapesti példa alapján. In Zsarnóczky, Rátz, & Michalkó (Eds.), VII. Magyar Turizmusföldrajzi Szimpózium 2019. Absztrakt kötet. Orosháza, Magyarország, Budapest, Magyarország: Kodolányi János Egyetem, 106 p., pp. 39–39.

- Gonda, T. (2014). A helyi termék turisztikai hasznosítása - a vidékfejlesztés új lehetősége. A Falu, 2014, 29(1), 17–23.

- Háló, K. (2021). Bőköz az asztalon – az Ormánság kézműves termékei a piacon. In Gonda (Ed.), A vidéki örökségi értékek szerepe az identitás erősítésében, a turizmus- és vidékfejlesztésben. Orfű, Magyarország: Orfűi Turisztikai Egyesület, 251 p., 52–59.

- Harcsa, I. M. (2017). Turizmus és gasztronómia adta lehetőségek a pálinka népszerűsítésére. A Falu, 32(2), 53–65.

- HCSO. (2023). Population by type of settlement, 1 January. Hungarian Central Statistical Office. https://www.ksh.hu/stadat_files/nep/en/nep0037.html 20 Jan. 2023

- Hopkins, E. (2022). Machine learning tools, algorithms, and techniques in retail business operations: Consumer perceptions, expectations, and habits. Journal of Self-Governance and Management Economics, 10(1), 43–55.

- Hungarian Tourism Agency. (2021). National tourism development strategy 2030 2.0. Budapest: Hungarian Tourism Agency. https://mtu.gov.hu/dokumentumok/NTS2030_Turizmus2.0-Strategia.pdf

- Ilincic, M. (2014). Benefits of creative tourism: The tourist perspective. In Richards, & Russo (Eds.), Alternative and creative tourism (pp. 99–113). Arnhem: ATLAS. [online].

- Jászberényi, M. (2020). A kulturális turizmus sokszínűsége. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó.

- Kerekesné, MÁ, & Kovács, G. (2017). I. Sajtakadémia: Kézműves Sajt, Tudomány, Turizmus. Tejgazdasági Szemle, 4(5), 27–27. https://www.tejgazdasagiszemle.hu/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Tejgazdasag-2017-szept.pdf

- Keskitalo, E. C. H., Schilar, H., Cassel, S. H., & Pashkevich, A. (2021). Deconstructing the indigenous in tourism. The production of indigeneity in tourism-oriented labelling and handicraft/souvenir development in Northern Europe. Current Issues in Tourism, 24(1), 16–32.

- Khlystova, O., Kalyuzhnova, Y., & Belitski, M. (2022). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the creative industries: A literature review and future research agenda. Journal of Business Research, 139, 1192–1210.

- Kliestik, T., Kovalova, E., & Lăzăroiu, G. (2022b). Cognitive decision-making algorithms in data-driven retail intelligence: Consumer sentiments, choices, and shopping behaviors. Journal of Self-Governance and Management Economics, 10(1), 30–42.

- Kliestik, T., Zvarikova, K., & Lăzăroiu, G. (2022a). Data-driven machine learning and neural network algorithms in the retailing environment: Consumer engagement, experience, and purchase behaviors. Economics, Management, and Financial Markets, 17(1), 57–69.

- Kulcsár, N. (2015). A fogyasztói érték és az élmény kontextusa a turisztikai szakirodalomban (The context of consumer value an experience in tourism literature). Vezetéstudomány – Budapest Management Review, 46(3), 18–25.

- Li, P. Q., & Kovacs, J. F. (2021). Creative tourism and creative spectacles in China. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 49(2021), 34–43.

- Lőrincz, K., & Sulyok, J. (Eds.). (2017). Turizmusmarketing. Akadémiai Kiadó. doi:10.1556/9789634540601

- Michalkó, G., & Lőrincz, K. (2007). A turizmus és az életminőség kapcsolatának nagyvárosi vetületei Magyarországon. Földrajzi Közlemények, 131(3), 157–169.

- Minorics, T., & Gonda, T. (2015). Kézműves és gasztrokulturális örökségünk turisztikai hasznosítása. In Oroszi (Ed.). Szőlő, bor, turizmus: tanulmányok a szőlészet, borászat és borturizmus témaköréből. Pécs, Magyarország: Pécsi Tudományegyetem, 174 p., 102–115.

- Nagy, D., Csapó, J., & Végi, S. (2021). A jövő turizmusa, a turizmus jövője – vállalkozói prognózis kutatás a Dél-dunántúli turisztikai vállalkozók szemszögéből. Turisztikai és Vidékfejlesztési Tanulmányok, 6(2), 72–85.

- National Committee of Intangible Cultural Heritage. (2023). Elements of the National Register of Best Safeguarding Practices. http://szellemikulturalisorokseg.hu/index0_en.php?name=en_f23_elements_best_safe

- Nica, E., Sabie, O.-M., Mascu, S., & Luțan (Petre), A. G. (2022). Artificial intelligence decision-Making in shopping patterns: Consumer values, cognition, and attitudes. Economics, Management, and Financial Markets, 17(1), 31–43.

- Nod, G., Mókusné, P. A., & Aubert, A. (2021). Kispadra ültetett desztinációmenedzsment a pandémia félidejében(?). Turizmus Bulletin, 21(2), 43–54.

- OECD. (2006). International Measurement of the Economic and Social Importance of Culture. Available at: https://www.oecd.org/sdd/na/37257281.pdf

- Palenčíková, Z., & Csapó, J. (2021). Creative tourism as a new tourism product in Slovakia. The theoretical and practical analysis of creative tourism: Formation, importance, trends. Nitra, Slovakia: Constantine the Philosopher University in Nitra, 135 p.

- Pengue, M. (2021). Etsy Statistics: Buyers Demographics, Revenues, and Sales. https://writersblocklive.com/blog/etsy-statistics/

- Pret, T., & Cogan, A. (2019). Artisan entrepreneurship: A systematic literature review and research agenda. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 25(4), 592–614.

- Remoaldo, P., Serra, J., Marujo, N., Alves, J., Gonçalves, A., Cabeça, S., & Duxbury, N. (2020). Profiling the participants in creative tourism activities: Case studies from small and medium sized cities and rural areas from Continental Portugal. Tourism Management Perspectives, 36, 100746.

- Richards, G. (2002). From cultural tourism to creative tourism: European perspectives. Tourism, 50(3), 225–234.

- Richards, G. (2020). Designing creative places: The role of creative tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 85, 102922.

- Richards, G. (2021). Rethinking cultural tourism. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing. 208 p.

- Richards, G., & Marques, L. (2012). Exploring creative tourism: Editors introduction. Journal of Tourism Consumption and Practice, 4(2), 1–11.

- Richards, G., & Raymond, C. (2000). Creative tourism. ATLAS News, 23, 16–20.

- Richards, G., & Wilson, J. (2006). Developing creativity in tourist experiences: A solution to the serial reproduction of culture? Tourism Management, 27, 1209–1223.

- Sajtos, L., & Mitev, A. (2007). SPSS kutatási és adatelemzési kézikönyv. Budapest: Alinea Kiadó.

- Sarantou, M., Kugapi, O., & Huhmarniemi, M. (2021). Context mapping for creative tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 86, 103064.

- Tan, S. K., Kung, S. F., & Luh, D. B. (2013). A model of ‘creative experience’ in creative tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 4(1), 153–174.

- Tan, S. K., Kung, S. F., & Luh, D. B. (2014). A taxonomy of creative tourists in creative tourism. Tourism Management, 42, 248–259.

- Törőcsik, M., & Csapó, J. (2021). A turisztikai trendek csoportosítása. In Csapó & Végi (Eds.), A globális, lokális és a glokális turizmus jelenlegi szerepe és jövője elméleti és gyakorlati megközelítésben. Pécs, Magyarország: PTE KTK Marketing és Turizmus Intézet, 145 p., 11–15.

- Tóth, A. (2023). New perspectives for living traditions: Intangible cultural heritage in north-east Hungary. Acta Ethnographica Hungarica, 66(2), 421–437.

- UNCTAD. (2010). Creative Economy Report 2010: A Feasible Development Option. https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/ditctab20103_en.pdf

- UNESCO. (2006). Towards Sustainable Strategies for Creative Tourism Discussion. Report of the Planning Meeting for 2008 International Conference on Creative Tourism. Santa Fe, New Mexico, U.S.A. October 25–27, 2006. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000159811

- UNESCO. (2021). Cultural and creative industries in the face of COVID-19: An economic impact outlook. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000377863

- UNWTO. (2018). Tourism and culture synergies. Madrid: UNWTO, 160 p.

- Vas-Guld, Z. (2021). “Terroir”? “Bio”? “Kézműves”? – minőséget meghatározó fogalmak? In Gonda (Ed.), A vidéki örökségi értékek szerepe az identitás erősítésében, a turizmus- és vidékfejlesztésben. Orfű, Magyarország: Orfűi Turisztikai Egyesület, 251 p., 188–196.

- Virginija, J. (2016). Interaction between cultural/creative tourism and tourism/cultural heritage industries. In Butowski (Ed.), Tourism - From empirical research towards practical application (pp. 137–157). London: IntechOpen Limited.

- Vuin, A., Carson, D. A., Carson, D. B., & Garrett, J. (2016). The role of heritage tourism in attracting “active” in-migrants to “low amenity” rural areas. Rural Society, 25(2), 134–153.