Abstract

Objectives

The purpose of this study was to translate the Work-Related Quality of Life Scale (WRQoLS-2) into Chinese and validate the capacity of the tool to effectively measure this concept in a cohort of nursing professionals from mainland China.

Methods

The Chinese version of the WRQoLS-2 (WRQoLS-2C) was developed using forward and backward language translation. In total, 639 nurses were invited to complete the WRQoLS-2C. Two weeks later, 79 (12.4%) nurses were retested. Construct validity was analysed using exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis (EFA, CFA). Cronbach’s α and the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) were used to assess internal consistency, reliability and test-retest reliability. Correlation between the WRQoLS-2C and the Quality of Nursing Work Life scale (QNWL) total score was used to assess criterion-relation validity.

Results

A seven-factor structure was revealed and confirmed using EFA (explaining 70.3% of the variance) and CFA (χ2 = 680.39, df = 413, χ2/df = 1.65, p < 0.001). The goodness-of-fit index was 0.88, and adjusted goodness-of-fit index 0.86 indicating a reliable model. The internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.94) and test-retest reliability (ICC = 0.84) of the WRQoLS-2C were high. The correlation coefficient between the WRQoLS-2C and QNWL total scores was 0.79 (p < 0.01).

Conclusion

The WRQoLS-2C was a reliable and valid instrument that can be used to assess WRQoL in the mainland China nursing profession.

Impact statement

There are few options available to assess work related quality of life in Chinese language. This study has confirmed that the WRQoLs-2C is an effective instrument to measure this concept in nurses from mainland China.

Plain language summary (PLS)

Work related quality of life is an important predictor of workplace turnover intension. Managers can take measures to improve work related quality of life and reduce employee attrition. There are very few tools to measure work related quality of life and fewer in Chinese language. We translated the WRQoLS-2 into Chinese according to Brislin's translation model, following cross-cultural adaption guidelines, and verified its reliability and validity in a cohort of mainland Chinese nurses. The translated instrument has good reliability and validity in nurses, but has not yet been verified in other occupational groups.

Keywords:

1 Introduction

Nurses constitute the largest group of healthcare workers, and the stability of the nursing team directly affects quality of the nursing care. There is a global nursing resource shortage and high rates of nurse turnover have become critical (Buchan et al., Citation2015; NSI Nursing Solutions, Citation2019). In China, the nursing situation is dire. In 2015 the total number of registered nurses in China reached 3.241 million, an increase from 1.52 in 2010 to 2.36 registered nurses per 1,000 population (National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China, Citation2017). Nonetheless, the proportion of nurses is still significantly lower than that in other countries, such as Canada and Japan, where the numbers of registered nurses per 1,000 population were 9.8 and 11.2, respectively, (WHO, Citation2018) in 2018.

There are many reasons for this situation, including a high turnover rate. According to a comparative review, nurse turnover rates significantly vary across countries; New Zealand has the highest rate (44.3%), followed by the United States (26.8%), Canada (19.9%) and Australia (15.1%) (Duffield et al., Citation2014). In China, a nationwide survey of 168 hospitals found that 12,000 nurses left their nursing positions or hospitals between 2003 and 2007; two-thirds of these nurses left because of resignation (38%) or a career change and one-third retired (Xu Ying & Liu Ke, Citation2011). Many factors are associated with high turnover rates, including the quality of working life (QWL), which is negatively correlated with attrition (Mosadeghrad et al., Citation2011) and can predict nurses’ intention to leave their organisation and profession (Lee et al., Citation2015). Improving QWL and job satisfaction of nurses and reducing the turnover rate are important for maintaining a healthy and sustainable care team.

QWL is a subjective feeling or perception of the job, organisation and employers (Vagharseyyedin et al., Citation2011). The definition of the QWL is variable (Vagharseyyedin et al., Citation2011). Often defined as the degree to which nurses are able to satisfy important personal needs through their experiences in their work place organisation while achieving the organisation’s goals (Brooks et al., Citation2007), QWL reinforces the notion that while managers pay attention to nurses’ performance, they should also pay attention to their work-related physical and psychological health. Reliable and valid instruments can to assess the QWL status of nurses and identify problems that need to be solved to improve work efficiency and nursing quality also vary. Tools, such as the 36-question Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) questionnaire (Yang et al., Citation2012) and World Health Organization Quality of Life-BREF (WHOQOL-BREF) (Wu et al., Citation2015), which are widely used in China, focus on the quality of life. However, these scales or questionnaires are not specifically focused on work-related quality of life. Brooks’ Quality of Nursing Work Life scale (QNWL) has been translated into Chinese (Fu et al., Citation2015) and is widely used but only applicable to the nursing profession. To compare difference in QWL across different professions, a universal scale is required, rather than a scale specific to a particular profession. The Work-related Quality of Life Scale (WRQoLS) is applicable to workplace rather than profession (Van Laar et al., Citation2007) and has proven reliability and validity across a variety of professional groups (Sulaiman et al., Citation2015). There are two versions of this scale; the original version has 23 items and after a series of studies, researchers supplemented the scale with a factor examining employee engagement and produced the second version, the WRQoLS-2 (http://www.qowl.co.uk/qowl_news_wrqol2_dev.html). The purpose of this study was to translate the WRQoLS-2 into Chinese, ensure cultural adaptation and test its validity and reliability in a nursing cohort.

2 Methods

2.1 Setting & sample

Convenience sampling was used to select participants. The researchers visited departments every Monday morning from December 2018 to March 2019 at a Class A Hospital of Grade III in Shandong Province, which employs approximately 3000 nurses. The inclusion criteria for this study were as follows: (1) agreement and consent to participate in this study and (2) registered nurses who worked at the hospital for at least six months. We only visited one department at a time to distribute the questionnaires. A total of 700 questionnaires were distributed.

Rex B. Kline suggests that 200 participants were enough for a factor analysis (Kline, Citation2015). According to Walter et al.(Walter et al., Citation1998), we assumed the null hypothesis value of ICC was 0.40; two replicated measurements; 80% of power; the significance level was 95% and the ICC value was 0.70 (Nunnally & Bernstein, Citation1994), the minimum sample size was 33. In our study, 79 nurses who completed the questionnaire the first time were retested two weeks later to assess the test-retest reliability of the WRQoLS-2C. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee at Qilu Hospital of Shandong University (KYLL-2017-524), and the participants provided informed consent before participating in this study.

2.2 Instruments

2.2.1 Chinese version of the WRQoLS-2

The WRQoLS-2 comprises 32 items, and Q32 reflects the perception of the overall quality of work life and is not used in scoring. The remaining 31 items were clustered into the following seven factors: control at work (CAW), employee engagement (EEN), general well-being (GWB), home-work interface (HWI), job career satisfaction (JCS), stress at work (SAW) and working conditions (WCS). Each item was scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Questions Q7, Q9, Q19, Q24 and Q29 were reverse scored and converted during the statistical analysis.

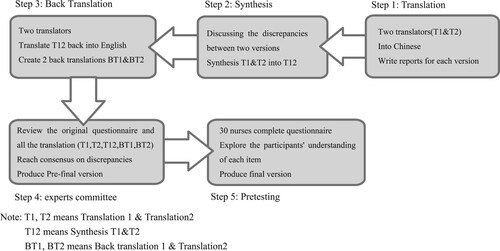

It is now recognised that if measures are to be used across cultures, the items must not only be translated well linguistically but also must be adapted culturally to maintain the content validity of the instrument at a conceptual level across different cultures (Beaton et al., Citation2000). The English version of the WRQoLS-2 was authorised and provided by Dr. Van Laar, D. L. by email and then translated into Chinese according to Brislin's translation model (Brislin, Citation1970) and cross-cultural adaption guidelines (Beaton et al., Citation2000). Dr. Van Laar, D. L. provided guidance and advice throughout the study. The whole translation process consisted of five steps (). (1) Forward translation: First, the WRQoLS-2 was translated into Chinese by two bilingual experts who were not familiar with the scale, and then, T1 (Translation 1) and T2 (Translation 2) were obtained. (2) Synthesis of the translations: By discussing the discrepancies between T1 and T2 by the two translators, a preliminary draft, T12 (Synthesis T1&T2), was obtained. (3) Back translation: Two researchers, including a bilingual nursing teacher and an English teacher familiar with Chinese who had not seen the original scale, translated T12 back into English and then obtained BT1 (Back translation 1) and BT2 (Back translation 2). (4) Expert panel: A panel of bilingual experts comprising 3 psychology and 2 nursing experts discussed the differences and modifications of T1, T2, T12, BT1 and BT2 in a meeting to form the prefinal version. (5) Pretesting: We selected 30 nurses for pretesting to explore the participants’ understanding of each item and ensure that each item had clear wording and clarity. Finally, we obtained the final Chinese version of WRQoLS-2, namely, WRQoLS-2C.

2.2.2 The QNWL questionnaire

QWL measured with the QNWL (nurses’ Quality of Nursing Work Life) is at least modestly associated with the WRQoLS-2C to establish concurrent validity. The QNWL questionnaire consisted of 42 items and the following 4 factors: work life-home life (7 items); work design (10 items); work context (20 items); and work world (5 items). The QNWL is a 6-point scale. The Chinese version of the QNWL was translated and modified by Fu X et al. (Fu et al., Citation2015). The Cronbach’s α of this questionnaire was 0.912, and this scale has been widely used in China Mainland (Li Sen et al., Citation2012; Huang et al., Citation2013; Wei Lijun et al., Citation2016).

2.3 Data collection

After obtaining informed consent, the nurses were asked to complete the following questionnaires: demographic questionnaire, the WRQoLS-2C and the QNWL. A total of 15–20 min was needed to complete the questionnaires. The questionnaires were completed independently and anonymously and then immediately collected. The research assistant checked each questionnaire to ensure that the questions were completed. If more than 5% of the data were incomplete, the questionnaire was discarded. Missing values (<5%) were imputed using mean or mode.

2.4 Data analysis

IBM SPSS® version 25.0 and AMOS® version 23.0 for Windows were used for the data management and analysis. The item-level content validity index (I-CVI) and scale-level content validity index (S-CVI) were used to assess the content validity of the WRQoLS-2C. The S-CVI includes S-CVI/UA (universal agreement), the percentage of items rated 3 or 4 by all experts, and S-CVI/Ave (average), which is the average I-CVI of all items in the scale. A panel of nursing experts (including two nursing directors, two nursing professors and three clinical nursing experts) scored each item of the WRQoLS-2C. The clinical nursing experts in this study were nurse practitioners with more than 15 years of work experience and associate chief nurses or chief nurses with a bachelor's degree or above. The following four grades were adopted for the scale: 1 = not relevant; 2 = somewhat relevant; 3 = quite relevant; and 4 = highly relevant. The “quite relevant” and “highly relevant” were given a score of one, all other ratings received a score of zero.

After reversing scores the total score and each factor score was obtained. Cronbach’s α and the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) were used to assess the test-retest reliability. Cronbach’s α greater than 0.80 (Nunnally & Bernstein, Citation1994), and the ICC greater than 0.70 (Aaronson et al., Citation2002) are acceptable values. The correlation between the total scores of the WRQoLS-2C and QNWL was used to assess the convergent validity of the WRQoLS-2C, and a correlation coefficient between 0.4 and 0.8 was satisfactory (An, Citation2006). The average variance extracted (AVE) value, an indicator of convergent validity, greater than 0.5 indicates good convergent validity (Fornell & David, Citation1981). Discriminant validity is the degree to which a test or measure diverges from (i.e. does not correlate with) another measure whose underlying construct is conceptually unrelated (Dixon & Johnston, Citation2019). The arithmetic square root of the AVE value of a factor greater than all correlation coefficients between this factor and the other factors indicate good discriminant validity (Fornell & David, Citation1981; Hair et al., Citation2006).

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) were used to assess the construct validity. All subjects were randomly divided into two groups. EFA was conducted with one group of 319 participants. CFA was conducted using the data of the remaining 320 participants. Before factor analysis, we first conducted the Bartlett's Test of Sphericity. An Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) value close to 1 and a p value less than 0.05 indicate that correlation between items is strong, and the items are suitable for factor analysis (Hair et al., Citation2006). Criterion to evaluate the goodness of fit of the CFA were as follow: Construct Reliability (CR) greater than 0.5, Chi square (χ2)/degree of freedom (χ2/df) less than 3, Root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) less than 0.08, and Comparative fit index(CFI), Goodness of fit index (GFI) and Adjusted goodness-of-fit index (AGFI) all greater than 0.90.

3 Results

3.1 Participant characteristics

In total, 700 questionnaires were distributed, and 639 questionnaires were returned that either did not have missing data or had missing values in less than 5% of the items. Among the 639 nurses, 570 (89.2%) were female and 69 (10.8%) were male. Participant characteristics are listed in .

Table 1. Characteristics of the sample (n = 639)

3.2 Translation of the WRQoLS-2C

For items 5 and 13, the term “employer” in Chinese means “boss” or “the leader of the organisation in which one works”, but this was incorrectly back-translated as “organisation”, which was confused with the term “organisation” in items 26, 27 and 28. To adapt to Chinese culture and distinguish the concepts across the items, we modified the scale according to the expert panel's suggestions.

3.3 Validity & reliability

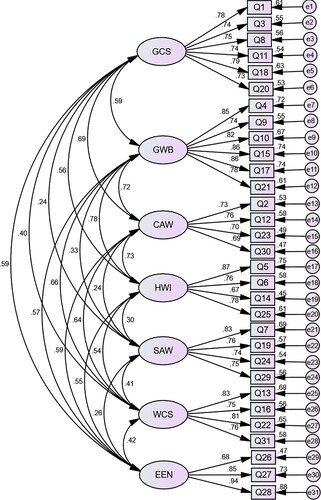

The content validity of each item was evaluated using I-CVIs by seven experts and the I-CVIs ranged from 0.86 to 1.000. The S-CVI/UA and S-CVI/Ave were 0.94 and 0.99, respectively, indicating that each item had a good correlation with the concept to be measured based on expert opinions. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) was 0.94, and Bartlett's test of sphericity was 5997.91 and statistically significant (P < 0.01), indicating that the data were appropriate for EFA. The EFA with principal component analysis extracted seven factors with eigenvalues >1.00 that explained 70.27% of the total variance. We re-ran the factor analysis with oblimin rotation, the results were same, suggesting that the seven factors were not correlated (). The confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) showed satisfactory goodness of fit indices. The chi-square test (χ2 = 680.39, df = 413, χ2/df = 1.65, P < 0.001) was significant. The RMSEA value was 0.04, the CFI was 0.96, the GFI was 0.88, and the AGFI was 0.86. shows the factor structure with factor loadings of the seven-factor model.

Table 2. Confirmatory factor analysis summary for all factors

In order to establish reliability, internal consistency, test-retest reliability and construct reliability scores were examined along with factor loadings. illustrates acceptable scores for Chronbach's alpha, which indicates good internal consistency and test-retest reliability. shows the correlations between the WRQoLS-2C total score, factors and the QNWL. The correlation between the WRQoLS-2C total score and QNWL was 0.79 (p < 0.01), indicating good concurrent validity. The AVE values of each factor ranged from 0.81 to –0.93, indicating good convergent validity which means high correlation between items within the same factor (). At the same time, the arithmetic square roots of AVE of each factor were all greater than the Pearson correlation coefficients between this factor and other factors, suggesting good discriminant validity. The Cronbach's α of the total scale increased to 0.94 if any one of items 7, 19, 24 and 29 were deleted. These four items belonged to the same factor, “Stress at Work (SAW)”. This factor showed very low concurrent validity (0.23) compared to other factors but was retained in our final model given its theoretical impact quality of work life.

Table 3. Correlation of WRQoLS-2 and QNWL (r, n = 639)

4 Discussion

In this study, we translated the WRQoLS-2 into Chinese and verified the translated instrument in a cohort of nurses from mainland China. We translated the WRQoLS-2 into Chinese according to Brislin's translation model (Brislin, Citation1970) and cross-cultural adaption guidelines (Beaton et al., Citation2000). It is well known that Chinese is not a single language; Chinese can be written traditionally or simplified. During the translation process, not only was the language considered but also the cultural background of people using the tool (Huang et al., Citation2008). The study showed that the translated version had good reliability that could have been strengthened by removing items related to stress at work but we chose to retain this factor as it is a critical construct of quality of life (Van Laar et al., Citation2007). Studies reported that job stress is a negative psychological state resulting from the interaction between workers and the working environment (Michie, Citation2002; Mosadeghrad et al., Citation2011), is a serious threat to work-related quality of life of health-care employees, and can cause absenteeism, turnover and a series of psychological problems (Mosadeghrad et al., Citation2011). In China, the level of job stress among nursing professionals is much higher than that in other medical professionals (Lu et al., Citation2016). Some studies have shown that the proportion of nurses who feel stressed out was as high as 88.7%, and women are more likely to feel pressure than men (Lu et al., Citation2016; Chen & Zhang, Citation2018).

his scale is widely used in many professions and has been translated into several languages (Sirisawasd et al., Citation2014; Sulaiman et al., Citation2015; Easton & van Laar, Citation2018; Fontinha et al., Citation2019). We found a seven-factor-structure of the WRQLS-2C, which similar to Thai version and differs from the factor structure of the Malaysian WRQLS-2 that yielded a five-factor model after EFA and CFA (Sirisawasd et al., Citation2014; Sulaiman et al., Citation2015). This difference may be explained by the Malaysian WRQLS-2 being verified in different professions like office workers and health care workers, while all the participants in this study and the Thai version were nurses. Different occupations have different job characteristics and different perceptions of scale items. Therefore, if this scale is introduced into other occupations in the future, it should be verified in that specific population. Cultural adjustment is an additional factor for consideration in various settings. For example, the participants in the Malaysian study were not exclusively Malays, but also Indians, Chinese and other ethnicities. While the language is same, origins in different countries lead to the need for cultural adjustments in the process of translation (Guo Jinyu, Citation2012). In our study, all participants were Chinese and from mainland China. Future studies should be conducted to further replicate the factor structure of the scale in different professions, different cultures and larger more diverse samples.

5 Conclusion

Our research shows that the reliability and validity of the WRQoLS-2C were adequate to assess Chinese nurses’ work-related quality of life. Compared to existing scales of assessing quality of life, this scale has fewer items, and the content is easy to comprehend, which can increase nurses’ acceptance and compliance. Nevertheless, further research is needed to confirm the psychometric properties of this scale in more representative samples of nurses and other healthcare professionals.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aaronson, N., Alonso, J., Burnam, A., Lohr, K. N., Patrick, D. L., Perrin, E., et al. (2002). Assessing health status and quality-of-life instruments: Attributes and review criteria. Quality of Life Research: An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care and Rehabilitation, 11(3), 193–205. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015291021312

- An, S. (2006). Scale evaluation of statistics lecture series. Journal of Nursing Science, 94–95.

- Beaton, D. E., Bombardier, C., Guillemin, F., & Ferraz, M. B. (2000). Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine, 25(24), 3186–3191. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-200012150-00014

- Brislin, W. R. (1970). Back-translation for cross-cultural research. Journal of Cross Cultural Psychology, 1(3), 185–216. https://doi.org/10.1177/135910457000100301

- Brooks, B. A., Storfjell, J., Omoike, O., Ohlson, S., Stemler, I., Shaver, J., et al. (2007). Assessing the quality of nursing work life. Nursing Administration Quarterly, 31(2), 152–157. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NAQ.0000264864.94958.8e

- Buchan, J., Duffield, C., & Jordan, A. (2015). ‘Solving’ nursing shortages: Do we need a New agenda? Journal of Nursing Management, 23(5), 543–545. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.12315

- Chen, C., & Zhang, C. (2018). Management status on occupational stress of domestic nurses. Hosp Admin J Chin PLA, 25, 456–459.

- Dixon, D., & Johnston, M. (2019). Content validity of measures of theoretical constructs in health psychology: Discriminant content validity is needed. British Journal of Health Psychology, 24(3), 477–484. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjhp.12373

- Duffield, C. M., Roche, M. A., Homer, C., Buchan, J., & Dimitrelis, S. (2014). A comparative review of nurse turnover rates and costs across countries. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 70(12), 2703–2712. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.12483

- Easton, S., & van Laar, D. (2018). Organizational stress, cultural differences and quality of working life. Indian Journal of Career and Livlihood Planning, 1, 27–38.

- Fontinha, R., Van Laar, D., & Easton, S. (2019). Overtime and quality of working life in academics and non-academics: The role of perceived work-life balance. International Journal of Stress Management, 26(2), 173–183. https://doi.org/10.1037/str0000067

- Fornell, C., & David, F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(3), 382–388. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800313

- Fu, X., Xu, J., Song, L., Li, H., Wang, J., Wu, X., Hu, Y., Wei, L., Gao, L., Wang, Q., Lin, Z., & Huang, H. (2015). Validation of the Chinese version of the quality of nursing work life scale. PloS one, 10, e0121150. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0121150

- Guo Jinyu, L. Z. (2012). The introduction process and evaluation criteria of the scale. Chin J Nurs, 47, 283–285. https://doi.org/10.3761/j.issn.0254-1769.2012.03.039

- Hair, J., Black, B., Babin, B., Anderson, R., & Tatham, R. (2006). Multivariate data analysis (6th ed). NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Huang, H., Xu, J., Zhang, R., & Fu, X. (2013). Quality of work life among nurses working in different level hospital in Guangdong province. Journal of Nursing Science, 28, 56–58.

- Huang, T. Y., Moser, D. K., Hsieh, Y. S., Lareau, S. C., Durkin, A. C., & Hwang, S. L. (2008). Validation of Chinese version of the modified pulmonary functional status and dyspnea questionnaire with heart failure patients in Taiwan. American Journal of Critical Care: An Official Publication, American Association of Critical-Care Nurses, 17(5), 436–442. https://doi.org/10.4037/ajcc2008.17.5.436

- Kline, R. B. (2015). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (4th ed). New York: The Guilford Press.

- Lee, Y. W., Dai, Y. T., & McCreary, L. L. (2015). Quality of work life as a predictor of nurses’ intention to leave units, organisations and the profession. Journal of Nursing Management, 23(4), 521–531. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.12166

- Li Sen, W. L., Xu Guoying, Z. H., & Ying Jusu, W. X. (2012). Present situation and Its related factors of quality of nursing work life. Nurs J Chin PLA, 29, 22–25.

- Lu, H., Zhang, Y., Yin, Q., & Yuan, X. (2016). Current status and coping style of work stress among medical staff in Suzhou city. Chin J Public Healt, 32, 1684–1688.

- Michie, S. (2002). Causes and management of stress at work. Occup Environ Med, 59(1), 67–72. https://doi.org/10.1136/oem.59.1.67

- Mosadeghrad, A. M., Ferlie, E., & Rosenberg, D. (2011). A study of relationship between job stress, quality of working life and turnover intention among hospital employees. Health Services Management Research, 24(4), 170–181. https://doi.org/10.1258/hsmr.2011.011009

- National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China. (2017). National Nursing Development Plan (2016–2020).

- NSI Nursing Solutions. (2019). 2019 National Health Care Retention Report.

- Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. H. (1994). Psychometric theory (3rd ed). New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Sirisawasd, P., Chaiear, N., Johns, N. P., & Khiewyoo, J. (2014). Validation of the Thai version of a work-related quality of life scale in the nursing profession. Safety and Health at Work, 5(2), 80–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shaw.2014.02.002

- Sulaiman, N. S., Choo, W. Y., Mat Yassim, A. R., Van Laar, D., Chinna, K., & Majid, H. A. (2015). Assessing quality of working life Among Malaysian workers. Asia-Pacific Journal of Public Health, 27(8_suppl), 94S–100S. https://doi.org/10.1177/1010539515583331

- Vagharseyyedin, S. A., Vanaki, Z., & Mohammadi, E. (2011). The nature nursing quality of work life. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 33(6), 786–804. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193945910378855

- Van Laar, D., Edwards, J. A., & Easton, S. (2007). The work-related quality of life scale for healthcare workers. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 60(3), 325–333. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04409.x

- Walter, S. D., Eliasziw, M., & Donner, A. (1998). Sample size and optimal designs for reliability studies. Statistics in Medicine, 17(1), 101–110. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19980115)17:1<101::AID-SIM727>3.0.CO;2-E

- Wei Lijun, H. H., Hu Yani, L. H., & Liuhong, X. (2016). The study of correlation between the quality of working life and turnover intention among Male nurses. Chinese Nursing Management, 16, 777–782. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1672-1756.2016.06.014

- WHO. (2018). World health statistics.

- Wu, H. C., Wen, S. H., Hwang, J. S., & Huang, S. C. (2015). Validation of the traditional Chinese version of the menopausal rating scale with WHOQOL-BREF. Climacteric: The Journal of the International Menopause Society, 18(5), 750–756. https://doi.org/10.3109/13697137.2015.1044513

- Xu, Y., You, L., Liu, K., Ma, W., Wang, H., Fang, J., Lv, A., Sun, J., Wu, Z., Lu, M., Yan, J., Zheng, J., & Zhu, X. (2011). Current turnover status of hospital nurses in China. Chinese Nursing Management, 11, 29–32.

- Yang, Z., Li, W., Tu, X., Tang, W., Messing, S., Duan, L., et al. (2012). Validation and psychometric properties of Chinese version of SF-36 in patients with hypertension, coronary heart diseases, chronic gastritis and peptic ulcer. International Journal of Clinical Practice, 66(10), 991–998. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-1241.2012.02962.x