Abstract

Aims:

To conduct an integrative literature review to reveal any evidence supportive of the integration of traditional therapies for First Nations peoples in Australia within a western healthcare model, and to identify which, if any, of these therapies have been linked to better health outcomes and culturally safe and appropriate care for First Nations peoples. If so, are there indications by First Nations peoples in Australia that these have been effective in providing culturally safe care or the decolonisation of western healthcare practices.

Design:

Integrative literature review of peer-reviewed literature.

Data Sources:

Online databases searched included CINAHL, Medline, Scopus, ScienceDirect InformitHealth, and ProQuest.

Review Methods:

Databases were searched for papers with full text available and published in English with no date parameter set. The PRISMA guidelines were used during the literature review and the literature was critiqued using the Critical Appraisal Skills tool.

Results:

Seven articles met the inclusion criteria and were included in the review. Four articles selected were qualitative, two used a mixed method design, and one used a quantitative method. Six themes arose: (i) bush medicine, (ii) traditional healers, (iii) traditional healing practices, (iv) bush tucker, (v) spiritual healing, and (vi) therapies that connected to cultures such as yarning and storytelling.

Conclusion:

There is limited literature discussing the use of traditional therapies in Western healthcare settings. A need exists to include traditional therapies within a Western healthcare system. Creating a culturally safer and appropriate healthcare experience for First Nations people in Australia and will contribute to advancement in the decolonisation of current healthcare models.

Impact statement

This integrative review addresses the current barriers in providing culturally appropriate healthcare for First Nations peoples and how decolonisation of healthcare models and the use of traditional therapies could benefit health and wellbeing outcomes.

Plain language summary

This research aims to investigate all available current research on the topic of integration of traditional therapies for First Nations peoples in Australia in the current healthcare model. By analysing common themes and the use of traditional therapies within the literature, this review aims to identify if such therapies have been useful in creating a more culturally safe and accessible healthcare system.

1. Introduction

The underutilisation of healthcare services by First Nations people in Australia is well-documented and is well known to adversely affect health and wellbeing outcomes (Elias & Paradies, Citation2021; McGough et al., Citation2022; O'Brien et al., Citation2013; Poroch, Citation2012; Shahid et al., Citation2013; Wilson & Waqanaviti, Citation2021). Factors that promote this underutilisation include limited understanding of First Nations belief systems, lack of culturally safe and/or appropriate, accessible care, and fear or distrust associated with Western healthcare providers (AIHW, Citation2020; Elias & Paradies, Citation2021; O'Brien et al., Citation2013; Poroch, Citation2012; Shahid et al., Citation2013; Wilson & Waqanaviti, Citation2021). A literature review conducted by Rooney et al. (Citation2021) identified that the incorporation of traditional First Nations medicines, healers, and therapies has a beneficial effect on the accessibility of palliative care services for First Nations peoples within a global context.

While it is recognised that Western healthcare systems continue to work towards adopting culturally safe and acceptable healthcare services for First Nations peoples, further work towards the decolonisation of healthcare is required (Geia et al., Citation2020). Decolonisation can be used to address the negative harm caused by colonisation including genocide and assimilation of First Nations peoples and exploitation of traditional knowledge (Narasimhan & Chandanabhumma, Citation2021; Smith, Citation2012). In order to provide decolonised healthcare, health and wellbeing should be provided from a First Nations viewpoint. This includes incorporating First Nations beliefs and practices surrounding health and wellbeing and placing this in the forefront of care opposed to the current Western-focused approach (Sherwood & Edwards, Citation2006; Wilson, Citation2016).

Approaching health and wellbeing using a holistic framework is aligned with the principles of the Social and Emotional Wellbeing (SEWB) Framework as well as First Nations peoples’ perspective of health, which encompasses mental health, physical, cultural, and spiritual health, with Land being central to wellbeing (McGough et al., Citation2022; SEWB, Citation2017; Ward & Wilson, Citation2022; Wilson & Waqanaviti, Citation2021). From a traditional perspective, some First Nations peoples may approach the concept of health and wellbeing from a different viewpoint than that of the Western healthcare system. These differences in worldviews often clash which may lead to poor health and wellbeing outcomes. The SEWB (Citation2017) aims to improve Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s wellbeing and mental health through a holistic and whole-of-life definition of health. SEWB (Citation2017) views health from a holistic viewpoint incorporating the health of family, kin, community, Country, culture, spirituality, and ancestry into the overall view of health and wellbeing (Calma et al., Citation2017). Central to this concept is the idea of identity. Through the effects of colonisation and generational traumas, First Nations peoples continue to lose cultural connections which can negatively affect health and wellbeing (Carlson, Citation2016, p. 38, 266). This holistic viewpoint of health and wellbeing that links to cultural and identity draws parallels to the concept of integrative care models. Integrated care involves the provision of efficient care that reflects the whole needs of the person, aims to incorporate multidisciplinary health service delivery, and strengthens person-centred healthcare (RACP, Citation2018; WHO, Citation2016).

The purpose of this integrative review was to identify what is known about the integration of First Nations traditional therapies in Western healthcare and identify which therapies have been linked to better health outcomes and culturally safe and appropriate care.

2. The review

2.1 Aim

The aim of this qualliterature review was to analyse literature exploring the use of traditional First Nations therapies within a Western healthcare setting. Thus the aim was to investigate the following questions: “In relation to traditional therapies for First Nations peoples in Australia, what has been integrated into Western models of healthcare?”, “Is there evidence to suggest the integration of traditional therapies will improve health and wellbeing outcomes for First Nations peoples in Australia” and “Have traditional therapies been utilised in healthcare? And if so, are there indications by First Nations peoples in Australia that these have been effective in providing culturally safe care?”.

2.2 Design

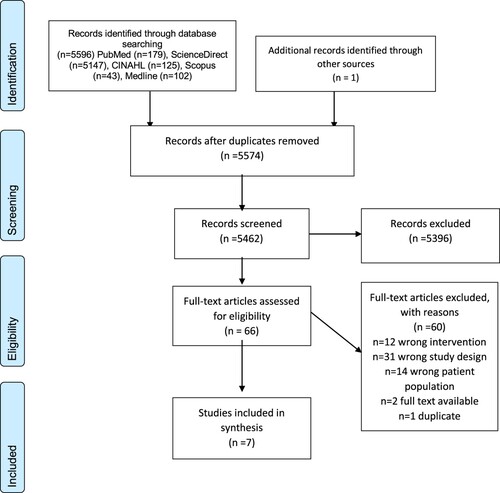

The framework used to guide this review was based on Whittemore and Knafl (Citation2005) updated methodology for integrative reviews. This review process contains the following stages: problem identification; systematic search of literature; data retrieval; article evaluation; and data analysis and presentation (Whittemore & Knafl, Citation2005). Additionally, utilisation of the Whittemore and Knafl (Citation2005) framework allowed included literature to consist of multiple research designs while also providing structure and rigor to the review. The method of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) Statement (Moher et al., Citation2009) was also employed when undertaking the research process (refer to ).

2.3 Search methods

Databases that were searched included PubMed, ScienceDirect, CINAHL, Scopus, and MedLine. Additionally, reference lists from included studies were also screened. Inclusion criteria for the review included peer reviewed, primary research studies, published in English, within an Australian context. Only studies that focused on the use of traditional and/or complementary therapies utilised by First Nations peoples in Australia were selected. No date parameters were set in order to investigate all relevant published literature. Studies were excluded if they did not primarily focus on First Nations peoples in Australia and associated traditional therapies. Database screening was conducted utilising search terms and keywords that focused on traditional healing practices including (Australian OR Australia) AND (Indigenous OR Aboriginal OR Torres Strait OR “First Nations”) AND (healing OR healers OR “traditional methods” OR “traditional therapy”) Search terms used for each database search have been summarised in . The search for literature was conducted over an extended period throughout 2022. An additional search using the same search terms and parameters was conducted in early 2023 prior to submission for publication. No additional literature was located.

Table 1. Search terms healing methods.

2.4 Data retrieval

The data extraction process utilised the Whittemore and Knafl (Citation2005) guide for data analysis. Seven articles were selected for review with data extracted including authors, country, study objectives, methodology, results and findings, and limitations.

Cultural safety of the methodology used in the research was also taken into consideration for data extraction including whether traditional knowledges and ownership of knowledge were recognised within the study ().

Table 2. Summary of articles.

2.5 Quality appraisal

Once articles were chosen, they were analysed using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) principles summarised in . The literature review incorporated all seven articles for critique, identifying the strengths and limitations of each article. Results from this appraisal found that all articles chosen indicated the studies were of high quality and demonstrated validity. An additional critique was added to the review of literature addressing Cultural Safety. Cultural Safety was critiqued against the guidelines and frameworks research conducted by the Lowitija Institute and the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) (Citation2013). Using this definition, an additional criterion assessing Cultural Safety was added to the Summary of Articles table () titled Cultural Considerations. Four of the articles chosen acknowledged Traditional Owners and knowledge systems while three articles made no mention of culturally safe methodology considerations.

Table 3. Methodological quality appraisal of articles (using CASP).

2.6 Data extraction and synthesis

As per Whittemore and Knafl (Citation2005) framework, the data analysis was conducted using the steps of data reduction, data display, data comparison, and conclusion verification. Organising data from each article into study demographics, methodology, sample population, key findings, limitations, and cultural considerations allowed for data reduction. For the data display stage, this information was organised into a table. In the data comparison stage, the articles were analysed to identify common themes and relationships and then were regrouped based on these commonly identified themes, summarised in .

Table 4. Summary of traditional therapies.

2.7 Ethical considerations

As the study is a literature review of existing literature, ethical clearance was not obtained. However, studies included in the review were critiqued for suitable ethical clearance with all studies obtaining ethical clearance.

3. Results

A total of 66 articles were identified for full-text review. On examination, 60 articles were excluded because they did not meet all inclusion criteria, were not primary research, did not provide information regarding the applications of traditional therapies, or did not meet the target population of First Nations peoples in Australia. The references list of the selected articles and secondary literature were manually assessed for further articles of relevance to the study. An additional article was added to the review from this manual search to make the total number of selected papers seven.

In total, seven articles were identified for inclusion in the review. Four of the included articles used a qualitative paradigm to conduct their studies using data collection methods of interviews, focus groups, feedback forms, or observational methods. Two articles used a mixed-method approach, and one study used a quantitative paradigm. The studies were conducted in four states and one territory of Australia: Northern Territory (n = 1), Queensland (n = 2), South Australia (n = 1), Victoria (n = 2), and Western Australia (n = 1). These seven studies identified 15 traditional therapies that had been integrated into Western healthcare settings. These therapies have been summarised in in order of prevalence in selected studies.

3.1 Themes

A review of the selected articles demonstrated a small number of traditional therapies that have been integrated into Western models of healthcare. The articles selected for this study were analysed for commonalities where traditional therapies could be seen to have been integrated. From this review, six major themes describing an integration of traditional therapies within Western healthcare models in Australia were identified. These therapies included (i) bush medicine, (ii) traditional healers, (iii) traditional healing practices, (iv) bush tucker, (v) spiritual healing, and (vi) therapies that connected to culture such as yarning and storytelling.

3.1.1 Bush medicine

Based on the literature, bush medicine was the most frequently mentioned traditional therapy either requested by First Nations peoples or incorporated into Western models of care (Adams et al., Citation2015; Gall et al., Citation2019; McGrath & Phillips, Citation2009; Panzironi Citation2013; Shahid et al., Citation2010). A quantitative study conducted by Adams et al. (Citation2015) with First Nations patients found that 18.7 percent of participants used at least one form of traditional medicine to support their care. This statistic included the use of bush medicine, traditional healers, and other complementary alternative medicines. 2.8 percent of all participants reported using traditional First Nation therapies, and 10.7 percent reported using complementary and/or alternative medicine not associated with primarily traditional First Nations therapies (Adams et al., Citation2015).

A mixed-methods study by Gall et al. (Citation2019) with First Nations women undergoing investigations for gynaecological cancer found that 86 percent of the study participants perceived traditional or complementary medicine as of high importance for their treatment. These women also reported challenges in communication and disclosure of traditional and complementary medicine use with Western healthcare providers due to poor communication, lack of trust, or lack of rapport (Gall et al., Citation2019).

When integrated, bush medicine was associated with building stronger connections between First Nations peoples and Western healthcare providers. Integration of bush medicines allowed spiritual and traditional practices to be incorporated within a healthcare setting (McGrath & Phillips, Citation2009). Bush medicine has a spiritual significance for some First Nations peoples and is also connected to a holistic worldview of health incorporating physical, emotional, and spiritual aspects of healing and wellbeing (Shahid et al., Citation2010). In a mixed method study, Panzironi (Citation2013) discussed the uses for bush medicines made from different types of plants and utilised by Ngangkaṟi (traditional healers of the Ngaanyatjarra, Pitjantjatjara and Yankunytjatjara languages groups) for wound care, or utilised during massage to provide healing.

3.1.2 Traditional healers

Another prominent intervention identified in the literature described the use of traditional healers (Adams et al., Citation2015; Gall et al., Citation2019; McGrath & Phillips, Citation2009; Panzironi Citation2013; Shahid et al., Citation2010). Adams et al. (Citation2015) identified that 2.8 percent of the cancer patients within their study utilised treatment from traditional First Nations practitioners while 2.4 percent visited complementary and alternative medicine practitioners. Gall et al. (Citation2019) identified that 33 percent of study participants reported using a traditional healer while undergoing gynaecological cancer investigations. In their investigation, Gall et al. (Citation2019) identified one hospital in South Australia that employed traditional healers to work alongside doctors and nurses to deliver safe complementary and traditional care for hospitalised First Nations patients.

Traditional healers can also provide First Nations peoples with culturally safe and appropriate care as they may share a common language or similar worldview that can help First Nations peoples feel more comfortable within a Western care system (McGrath & Phillips, Citation2009). A qualitative study by Shahid et al. (Citation2010) identified that most traditional healers were located in rural or remote areas requiring First Nations patients to travel away from metropolitan healthcare to connect with traditional healers or suppliers of bush medicine. This presented a significant barrier as it was often time consuming, expensive and off Country, thereby obstructing traditional healers in their practice, and limiting access to First Nations patients in metropolitan hospitals (Shahid et al., Citation2010).

Panzironi (Citation2013) focused on the First Nations traditional healers from the Aṉangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara Lands and determined that the incorporation of traditional healers could help aid in closing the gap in healthcare for First Nations peoples and significantly improve health outcomes. Panzironi (Citation2013) also addressed how the inclusion and recognition of First Nations traditional healers as legitimate health practitioners could help increase the First Nations healthcare workforce and play a vital role in developing a two-way healthcare system between Western medical practitioners and First Nations traditional practitioners.

3.1.3 Traditional healing practices

Theme three acknowledged traditional healing practices that were described in the literature as methods of healing utilised by First Nation peoples (Panzironi Citation2013; Shahid et al., Citation2010). Shahid et al. (Citation2010) mentioned the use of traditional healing practices in a broad sense without further elaboration on the definition of traditional healing practices, however, discussed that traditional healing practices were often used in conjunction with bush medicines. Traditional healing practices were an important aspect of cancer treatments with some First Nations patients indicating they wanted to return to Country and incorporate bush medicine and other healing practices within their treatment (Shahid et al., Citation2010). Panzironi (Citation2013) provides an extensive document on the types of traditional healing practices used by First Nations peoples of the Aṉangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara Lands including healing methods such as Puuṉi (blowing breath), Pampuni (healing touch), Marali (spiritual healing), and suction method. Puuṉi is a healing process where a Ngangkaṟi (traditional healers) uses blowing breath with the intended purpose to neutralise sickness and help strengthen the spirit (Panzironi Citation2013). For the practice of Pampuni, a Ngangkaṟi will heal the body through touch or massage (Panzironi Citation2013). The practice of Marali includes a form of spiritual healing where Ngangkaṟi utilise tools to restore spiritual health and strength (Panzironi Citation2013). Lastly, the suction method involved a Ngangkaṟi using their mouth to pull out sickness or to clean out the blood (Panzironi Citation2013).

3.1.4 Bush tucker

The fourth theme identified described the use of traditional foods often referred to as bush tucker. This was highlighted in two studies to connect to culture as a means to promote healing (Gall et al., Citation2019; McGrath & Phillips, Citation2009). McGrath and Phillips (Citation2009) identified that during end-of-life care bush tucker provided a connection to culture and provided a form of comfort for First Nations patients. Gall et al. (Citation2019) conducted qualitative interviews revealing that the use of traditional foods was mentioned by participants to have healing properties and held cultural significance, however, their study did not specifically focus on the use of bush tucker as a form of traditional and/or complementary medicine.

3.1.5 Spiritual healing

Spiritual healing arose as another concept addressed in the literature (Kingsley et al., Citation2021; Panzironi Citation2013). Kingsley et al. (Citation2021) discussed the building of gathering places to provide a safe place to reconnect to cultures and communities promoting health and wellbeing through processes such as yarning to provide spiritual and cultural benefits. Gathering places helped provide First Nations patients with a way to connect to culture and community and promote spiritual healing and reciprocal support (Kingsley et al., Citation2021). As previously mentioned, Panzironi (Citation2013) discusses Marali, or a form of spiritual healing performed by a Ngangkaṟi. Panzironi (Citation2013) discusses how spiritual healing involves the interaction of three main spiritual entities: the Ngangkaṟi’s own spirit, the patient’s own spirit, and the different spiritual entities called mamu (negative spirit forces) that can cause misalignment or illness. Removal of these spiritual interferences by a Ngangkaṟi through spiritual healing can help establish the balance between physical, emotional, and mental health of the patients (Panzironi, Citation2013).

3.1.6 Yarning and cultural connection

The final theme identified yarning and cultural connection as central to traditional health. Other methods less mentioned in the literature that promote healing and wellbeing for First Nations patients included culturally specific interventions such as artwork, storytelling, yarning, healing circles, singing and or chanting, and caring for Country which is defined in Kingsley et al. (Citation2009) as “having knowledge, sense of responsibility and inherent right to be involved in the management of traditional lands” (p.291) (Adams et al., Citation2015; Kingsley et al., Citation2009; Kingsley et al., Citation2021; Panzironi Citation2013). Many of these concepts were only mentioned briefly within the literature. Kingsley et al. (Citation2009) highlighted the importance that caring for the Country has on the health and wellbeing of First Nations peoples from a holistic standpoint. Caring for Country offered benefits such as building self-esteem, fostering self-identity, maintaining cultural connection, and allowing for relaxation and enjoyment through contact with the natural environment (Kingsley et al., Citation2009). Kingsley et al. (Citation2021) also highlighted additional methods in the use of healing and wellbeing including gathering places, story work, yarning, and artwork as elements that help promote connectivism, self-determination, and respect for culture, leading to the development of a culturally safe environment within a Western healthcare setting.

4. Discussion

The integration of bush medicines, healers, healing practices, spiritual healing, and other traditional therapies has the potential to facilitate holistic healthcare for First Nations peoples (Adams et al., Citation2015; Gall et al., Citation2019; Gee et al., Citation2014; McGrath & Phillips, Citation2009; Panzironi, Citation2013; Shahid et al., Citation2010). However, this viewpoint of integration of traditional therapies presents the issue from a Westernised approach to problem solving. We note that dominant Westernised models of health care such as an integrated approach, can perpetuate a positioning of First Nations Peoples whereby they effectively relinquish their cultural agency in conceded adherence to Western models of care, as a single avenue to achieve access to health care. Thus the onus is placed on First Nations Peoples to surrender to a model of care that requires them as recipients of care to act as ‘good patients’ who must integrate into a Western model of health care if they wish to receive health care service. This alternate conceptualisation of integration from a First Nations standpoint demonstrates a need for a shared aspiration for decolonisation of healthcare systems, such that inequity in access is removed and culturally safe engagement is achieved through reciprocal rather than transactional means. In doing so, cultural safety is less likely to be compromised and limitations of adverse dominant culture health model access traits are achieved, resulting in an authenticity of inclusion for First Nations people overall (Geia et al., Citation2020; McGough et al., Citation2022). In order to promote positive change within Western healthcare systems, decolonisation is needed (Geia et al., Citation2020). Addressing institutionalised racism in policies and practices within a healthcare setting helps promote decolonisation instead of mere integration (Elias & Paradies, Citation2021). This decolonisation of care can enable re/connection to culture thereby enhancing health and wellbeing. When reviewing the literature, the most common traditional therapy discussed was the use of traditional healers. Traditional healers play an important role in improving health and wellbeing outcomes for First Nations peoples by providing spiritual, cultural, social, and emotional support that may be overlooked by a Western model of healthcare. As traditional healers may have a similar worldview, culture, or language to First Nations patients, they could aid in the decolonisation of current Western healthcare models. This could improve utilisation of healthcare services, and also create better health and wellbeing outcomes for First Nations peoples (Elias & Paradies, Citation2021; McGrath & Phillips, Citation2009). Having First Nations traditional healers employed to work alongside Western healthcare professionals could play a significant role in providing culturally safe and decolonising care for First Nations peoples (Gall et al., Citation2018). Decolonisation methods such as this support a holistic ‘whole-of-life‘ delivery of healthcare services that highlight spiritual and cultural aspects of First Nations health and wellbeing. This decolonisation also supports First Nations peoples’ access to inclusive and improved healthcare services by building collaborative communication between Western healthcare providers and First Nations peoples, thus enhancing trust and rapport between clinicians and First Nations clients (Gall et al., Citation2018).

For healthcare professionals to provide culturally appropriate care it is important healthcare providers have an appreciation and understanding of First Nations Australians belief systems in relation to health, wellbeing, and healing (Shahid et al., Citation2010). The recognition of traditional therapies not only allows First Nations Australians choice in their own healthcare but also aids in the decolonisation of current healthcare practices (Shahid et al., Citation2010). This integration allows for culturally safe practice by allowing for cultural connection and support while fostering culturally appropriate healthcare practices (Gall et al., Citation2019; Kingsley et al., Citation2021; Shahid et al., Citation2010).

This review also identified barriers with the use of traditional therapies by First Nations peoples. Although the use of a bush medicine or complementary and alternative medicines was mentioned the most within the reviewed literature, few identified what supplements or traditional medicines were being utilised by patients and referred to bush medicine in a broad sense. Although broad, the studies that discussed the use of traditional therapies within a Western healthcare setting linked this use to better health and wellbeing outcomes and an effective medium to provide culturally safe care (Gall et al., Citation2019; Kingsley et al., Citation2021; Shahid et al., Citation2010). Another barrier related to the incorporation of traditional therapies included the non-disclosure of the use of traditional medicines and healing due to the fear of being judged or stigmatised against (Adams et al., Citation2015; Gall et al., Citation2018). This barrier highlights the current privilege Western healthcare models have within an Australian context which can lead to poorer disclosure of the use of traditional therapies for the fear of being dismissed, ridiculed, or facing discrimination (Gall et al., Citation2019; Kingsley et al., Citation2021; Shahid et al., Citation2009). Another barrier of implementing traditional therapies was the lack of understanding of the bioactive components of traditional medicines and the interactions they may have with Western medicines (Shahid et al., Citation2010). Additionally, some First Nations Australians who may wish to utilise such healing therapies find these difficult to access within urbanised settings (McGrath & Phillips, Citation2009; Shahid et al., Citation2010). Access to such services is more prevalent in rural and remote settings further highlighting the privilege and prevalence of Western-based medical models (McGrath & Phillips, Citation2009; Shahid et al., Citation2010). Decolonising Western viewpoints and models of care may provide First Nations peoples with better access to care that is culturally important to them without the need for relocation or additional expenses (Shahid et al., Citation2010).

From the literature reviewed, the use of cultural practices such as spiritual healing, yarning, bush tucker, or other traditional healing practices showed a positive benefit for First Nations peoples (Kingsley et al., Citation2009; Kingsley et al., Citation2021; McGrath & Phillips, Citation2009; Panzironi, Citation2013; Shahid et al., Citation2010). Evidence suggests the use of traditional therapies can improve the health and wellbeing outcomes for First Nations peoples in Australia while supporting the decolonisation of current healthcare models allowing for more culturally safe and appropriate healthcare services (Adams et al., Citation2015; Gall et al., Citation2019; Kingsley et al., Citation2021; Shahid et al., Citation2010). From a global perspective, the idea of incorporating First Nations healing practices into a Western healthcare approach is a new field of research. Some recent studies address the notion of decolonising healthcare with First Nations health practices from a global perspective. In New Zealand, Marques et al. (Citation2022) highlighted that rongoā Māori fostered Māori health and wellbeing. A scoping study by Asamoah et al. (Citation2023) analysing research from Australia, Canada, and New Zealand found traditional healing practice can be utilised to support a Western biomedical approach. However, there is limited research identifying the types of traditional methods used, their effectiveness in supporting health and wellbeing and the decolonisation of healthcare, especially within an Australian context.

5. Limitations

This review has several limitations. Firstly, the literature search was restricted to electronic databases. Using only electronic databases for the literature review may have limited access to potential useful literature publications addressing the topic, especially as First Nations knowledges are often oral and not always recorded in formats that lend itself to Western knowledge construction and dissemination. As such relevant First Nations knowledge’s may have been relevant to the study but may have been overlooked in adherence to the integrative literature review methods selected for the study. Additionally, two of the studies included were conducted by the same lead author and researcher team which could have the potential for introducing bias to the literature review. Finally, the initial selection of articles was undertaken by a research student. Guidance during the integrative review process was provided by experienced senior researchers which may mitigate any selection risks and strengthen the review. All authors participated in the assessment of articles and agreement was achieved regarding the inclusion of articles.

6. Implication for practice

Limited literature exists addressing the use of First Nations traditional therapies in Western healthcare and how this could aid in the decolonisation of current models. The findings of this integrative review suggest that traditional therapies have the benefit of providing holistic and culturally appropriate care for First Nations peoples which may aid in the utilisation of healthcare services. Such improvements support equity for First Nations peoples within Western healthcare systems, increasing the utilisation of services and decolonisation of current healthcare models.

7. Recommendations

In order to improve access to culturally safe healthcare, decolonisation of current Western healthcare systems is needed. Evidence has indicated that First Nations healers and traditional healing methods are beneficial in improving access and cultural appropriate care while approaching care from a holistic and ‘whole-of-life’ approach. This holistic and integrative model of care has the potential to create more culturally safe and appropriate care settings that incorporate multiple aspects of health and wellbeing such as spiritual, cultural, emotional, and social care. More emphasis on First Nations healers and health practices being acknowledged as authentic healthcare options within a Western healthcare model would aid in the improvement of culturally appropriate care and bridge the gap some First Nations Australians face when accessing Western healthcare services.

8. Conclusion

There is limited research available on the implications of integrating traditional therapies into a Western healthcare model or on the benefits such implementations may have on the health and wellbeing of First Nations Australians. This integrative review identified that current research indicates the integration of First Nations traditional therapies has holistic benefits improving health and wellbeing. However, there is currently little evidence on how traditional therapies within a Western model of health could decolonise current services.

Contributions

All the authors (E.R., R.W., A.J.) contributed to the design of the study. The data collection was undertaken by E.R. All authors contributed to critical appraisal and data analysis. Manuscript for publication was prepared by E.R. with revisions made by R.W. and A.J. All authors have agreed on the final version of the manuscript.

Twitter Abstract

Decolonisation of care: Putting traditional healthcare models at the forefront creates culturally safer care for First Nations people in Australia. #FirstNations #Decolonisation # #TraditionalTherapies

Acknowledegments

The authors wish to acknowledge the helpful feedback, advice, and culturally relevant guidance Katrina Ward on drafts of this manuscript. The authors used the PRISMA checklist when writing the report Page, M.J., McKenzie, J.E., Bossuyt, P.M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T.C., Mulrow, C.D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J.M., Akl, E.A., Brennan, S.E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J.M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M.M., Li, T., Loder, E.W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., McGuinness, L.A., Stewart, L.A., Thomas, J., Tricco, A.C., Welch, V.A., Whiting, P., and Moher, D. (2020). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adams, J., Valery, P. C., Sibbritt, D., Bernardes, C. M., Broom, A., & Garvey, G. (2015). Use of traditional indigenous medicine and complementary medicine among indigenous cancer patients in Queensland, Australia. Integrative Cancer Therapies, 14(4), 359–365. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534735415583555

- Asamoah, G. D., Khakpour, M., Carr, T., & Groot, G. (2023). Exploring indigenous traditional healing programs in Canada, Australia, and New Zealand: A scoping review. Explore (New York, N.Y.), 19(1), 14–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.explore.2022.06.004

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2020). Palliative care services in Australia. Australian Government. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/palliative-care-services/palliative-care-services-in-australia/data.

- Calma, T., Dudgeon, P., & Bray, A. (2017). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander social and emotional wellbeing and mental health. Australian Psychologist, 52(4), 255–260. https://doi.org/10.1111/ap.12299

- Carlson, B. (2016). The politics of identity: Who counts as Aboriginal today? Aboriginal Studies Press. https://doi.org/10.3316/informit.9781922059963

- Elias, A., & Paradies, Y. (2021). The costs of institutional racism and its ethical implications for healthcare. Journal of Bioethical Inquiry, 18(1), 45–58. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11673-020-10073-0

- Gall, A., Anderson, K., Diaz, A., Matthews, V., Adams, J., Taylor, T., & Garvey, G. (2019). Exploring traditional and complementary medicine use by Indigenous Australian women undergoing gynaecological cancer investigations. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 36, 88–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctcp.2019.06.005

- Gall, A., Leske, S., Adams, J., Matthews, V., Anderson, K., Lawler, S., & Garvey, G. (2018). Traditional and complementary medicine use among indigenous cancer patients in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States: A Systematic Review. Integrative Cancer Therapies, 17(3), 568–581. http://doi.org/10.1177/1534735418775821

- Gee, G., Dudgeon, P., Schultz, C., Hart, A., & Kelly, K. (2014). Social and emotional wellbeing and mental health: An Aboriginal perspective. In P. Dudgeon, M. Milroy, & R. Walker R (Eds.), Working together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mental health and wellbeing principles and practice – revised edition (pp. 55–68). Commonwealth of Australia.

- Geia, L., Baird, K., Bail, K., Barclay, L., Bennett, J., Best, O., Birks, M., Blackley, L., Blackman, R., Bonner, A., Bryant AO, R., Buzzacott, C., Campbell, S., Catling, C., Chamberlain, C., Cox, L., Cross, W., Cruickshank, M., Cummins, A., … Wynne, R. (2020). A unified call to action from Australian nursing and midwifery leaders: Ensuring that Black lives matter. Contemporary Nurse, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/10376178.2020.1809107

- Kingsley, J., Munro-Harrison, E., Jenkins, A., & Thorpe, A. (2021). Developing a framework identifying the outcomes, principles and enablers of ‘gathering places’: Perspectives from Aboriginal people in Victoria, Australia. Social Science & Medicine, 283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114217

- Kingsley, J., Townsend, M., Phillips, R., & Aldous, D. (2009). “If the land is healthy … it makes the people healthy”: The relationship between caring for country and health for the Yorta Yorta Nation, Boonwurrung and Bangerang Tribes. Health & Place, 15(1), 291–299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.05.009

- Lowitija Institute and Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders Studies (AIATSIS). (2013). Researching right way: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health research ethics: A domestic and international review. National Health and Medical Research Council. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/Indigenous%20guidelines/evaluation-literature-review-atsi-research-ethics.pdf.

- Marques, B., Freeman, C., & Carter, L. (2022). Adapting traditional healing values and beliefs into therapeutic cultural environments for health and well-being. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(1), 426. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010426

- McGough, S., Wynaden, D., Gower, S., Duggan, R., & Wilson, R. (2022). There is no health without cultural safety: Why cultural safety matters. Contemporary Nurse, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/10376178.2022.2027254

- McGrath, P., & Phillips, E. L. (2009). Insights from the northern territory on factors that facilitate effective palliative care for Aboriginal peoples. Australian Health Review, 33(4), 636–644. https://doi.org/10.1071/AH090636

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. http://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

- Narasimhan, S. & Chandanabhumma, P. P. (2021). A scoping review of decolonization in indigenous-focused health education and behavior research. Health Education & Behavior, 48(3), 306–319. https://doi.org/10.1177/10901981211010095

- National Strategic Framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders Peoples’ Mental Health and Social and Emotional Wellbeing 2017-2023 (SEWB). (2017). Australian health ministers’ advisory council, Australian Government. https://www.niaa.gov.au/sites/default/files/publications/mhsewb-framework_0.pdf.

- O'Brien, A., Bloomer, M., McGrath, P., Clark, K., Martin, T., Lock, M., Pidcock, T., van der Riet, P., & O'Connor, M. (2013). Considering Aboriginal palliative care models: The challenges for mainstream services. Rural and Remote Health, 13(2), 2339. https://doi.org/10.22605/RRH2339

- Panzironi, F., & Anangu Ngangkaṟi Tjutaku Aboriginal Corporation. (2013). Hand-in-hand. Report on Aboriginal traditional medicine. Aṉangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara Lands (APY): Aṉangu Ngangkaṟi Tjutaku Aboriginal Corporation.

- Poroch, N. (2012). Kurunpa: Keeping spirit on country. Health Sociology Review, 21(4), 383–395. https://doi.org/10.5172/hesr.2012.21.4.383

- Rooney, E. J., Johnson, A., Jeong, S. Y., & Wilson, R. L. (2021). Use of traditional therapies in palliative care for Australian first nations peoples: An integrative review. Journal of Clinical Nursing. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.16070

- Royal Australasian College of Physicians. (2018). Physicians supporting better paitentt outcomes: Discussion paper.

- Shahid, S., Bessarab, D., Van Schaik, K., Aoun, S., & Thompson, S. (2013). Improving palliative care outcomes for Aboriginal Australians: Service providers’ perspectives. BMC Palliative Care, 12(1), 26. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-684X-12-26

- Shahid, S., Bleam, R., Bessarab, D., & Thompson, S. C. (2010). “If you don't believe it, it won't help you”': Use of bush medicine in treating cancer among Aboriginal people in Western Australia. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine, 6(1), 18–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-4269-6-18

- Shahid, S., Finn, L. D., & Thompson, S. C. (2009). Barriers to participation of Aboriginal people in cancer care: Communication in the hospital setting. Medical Journal of Australia, 190(10), 574–579. http://doi.org/10.5694/mja2.2009.190.issue-10

- Sherwood, J., & Edwards, T. (2006). Decolonisation: A critical step for improving Aboriginal health. Contemporary Nurse : A Journal for the Australian Nursing Profession, 22(2), 178–190. https://doi.org/10.5172/conu.2006.22.2.178

- Smith, L. T. (2012). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and indigenous peoples (2nd ed.). Zed Books.

- Ward, K., & Wilson, R. L. (2022). Chapter 4: The social and emotional well-being (SEWB) of first nations Australians. In N. Proctor, R. L. Wilson, H. Hamer, D. McGarry, & M. Loughhead (Eds.), Third edition commissioned (2021) mental health: A person-centred approach (pp. 61–80). Cambridge University Press.

- Whittemore, R., & Knafl, K. (2005). The integrative review: Updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 52(5), 546–553. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x

- Wilson, R. L. (2016). An Aboriginal perspective on ‘Closing the Gap’ from the rural front line. Rural and Remote Health, 16(1), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.22605/RRH3693

- Wilson, R. L., & Waqanaviti, K. (2021). Chapter 13 emotional and social well-being for first nations people in the mental health context. In Yatdjulgin: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nursing and midwifery care (pp. 281–306). Cambridge University Press.

- World Health Organisation. (2016). Integrated care models: An overview. Health Services Delivery Programme, Division of Health Systems and Public Health Regional Office for Europe. https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/322475/Integrated-care-models-overview.pdf.