Abstract

Background

Hand hygiene compliance (HHC) is recognised as a major factor in the prevention of healthcare-associated infections. Healthcare workers (HCWs) compliance is still suboptimal. Simulation as an educational strategy may contribute to improved performance.

Objective

This study aimed to assess the effect of simulation interventions led by nursing students on HCWs’ HHC.

Method

A prospective quasi-experimental design with before and after intervention measurements was implemented in an 1150-bed tertiary hospital. Four consecutive periods, measuring before and after HHC, were examined in four hospital divisions. For each division, unique simulation activities were developed and led by nursing students, educators, and hospital leaders. Sixty seven students and 286 healthcare workers, along with two nurse educators, participated in the simulation sessions. HHC of all HCWs in the divisions was assessed by hospital infection control personnel.

Results

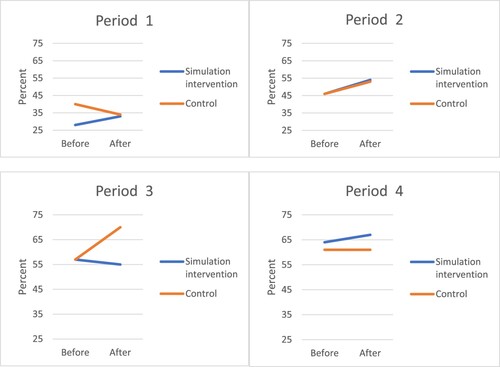

Hospital HHC rose across the four periods in all four divisions during this study. In three out of four periods and divisions, HHC increased significantly more in the simulation intervention groups compared to the overall hospital improvement.

Conclusion

Student-led simulation for HCWs is an additional effective method to improve HHC. Nursing managers should consider joining forces with nursing educators to enable students to become agents of change in healthcare settings and encourage further collaboration.

Impact statement

Students led simulations is a valuable strategy for improving HCWs HHC in a hospital setting.

Plain language summary

Hand hygiene of healthcare workers is a critical element of infection prevention. However, their compliance with this practice is less than optimal. Simulation is a widely accepted strategy for education and improvement in healthcare. In this study, nursing students led simulation sessions relating to hand hygiene for hospital healthcare workers. The simulation intervention was conducted during four subsequent years in four divisions which are comprised of Obstetrics/gynecological, internal, or surgical wards, and critical care areas in a tertiary hospital. Nursing educators and hospital nurse managers developed unique scenarios suitable for each division. Hand hygiene compliance improved throughout the hospital during these years in three of four divisions following the simulation activities. Student-led simulation offers an additional approach to improving hand hygiene compliance. Furthermore, this collaboration between nursing students, educators, and hospital staff benefits all parties involved.

Introduction

Healthcare associated infections are among the major challenges in hospital acute care (Doronina et al., Citation2017). Hand hygiene (HH) is recognised as a factor in their reduction and prevention (World Health Organization [WHO], Citation2009), and one of the most effective and simplest measures available (Doronina et al., Citation2017; Mouajou et al., Citation2022; Siegel et al., Citation2007). Hand hygiene compliance (HHC) is historically known to be low and has received additional importance in recent years (Mouajou et al., Citation2022). Research utilises the WHO Five Moments guidelines and hand rubbing techniques to improve HHC (Al-Maani et al., Citation2022; Allegranzi et al., Citation2013; Kibira et al., Citation2022). A recent systematic review (Bredin et al., Citation2022) including 105 studies found that the pooled HHC rate for nurses was 52% (95% CI: 47–57) and for doctors was 45% (95% CI: 40–49%). Different multimodal interventions have been used with some success in improving HHC (Al-Maani et al., Citation2022; Kibira et al., Citation2022). Despite the common knowledge regarding the importance of HH, compliance is lower than optimal and there remains much need for improvement (Gould et al., Citation2017).

At the same time, simulation has rapidly developed as an educational method based on the experiential theory (Kolb, Citation2014) to reinforce multiple skills among healthcare students and personnel (Cantrell et al., Citation2017; Dixon-Woods & Lame, Citation2018). Simulation has been widely and successfully used in healthcare education and healthcare practice for task training, team building, and systems improvement (Orledge et al., Citation2012). During the COVID 19 pandemic, several medical centers reported on in situ simulation to improve guidelines for the intubation of infected patients and to improve the flow and care of incoming patients (Choi et al., Citation2020; Lateef et al., Citation2020). Its use has continued to expand and contribute to technical and non-technical skills in varied healthcare fields (Zhang et al., Citation2018). Recent publications report on the successful use of simulation with trauma teams (Rosqvist et al., Citation2019), personnel training for the implementation of a new stroke protocol (Ortega et al., Citation2018), and gynecology/obstetric residents (Garber et al., Citation2018). Studies have proposed experiential learning theory as a theoretical model for simulations in healthcare, citing their effectiveness in teaching and debriefing (O’Regan et al., Citation2016; Sawyer et al., Citation2016). Successful learning from simulation requires that learners have opportunities to act (or observe the simulation activity), reflect, discuss actions, and internalise learning.

In the past two decades, various interventions have aimed to improve HH compliance. A study by Moghnieh et al. (Citation2017) compared incentive-driven plans with audits and feedback to staff, and found that both were important to maintain sustainable results. The incentive-driven intervention group increased a threefold HHC, from 21% to 60%, whereas the audits and feedback group increased twofold, from 23% to 51%. Several studies assessing the effectiveness of interventions for hospital nurses report that education and feedback to improve compliance as well as multi-modal strategies were needed to sustain any improvements (Allegranzi et al., Citation2013; Doronina et al., Citation2017; Erasmus et al., Citation2011; Moro et al., Citation2014; Staines et al., Citation2017). Allegranzi et al. (Citation2013) implemented the WHO strategy with provision of alcohol based hand rub, training, monitoring of practices and workplace remainders to improve HHC. They used HHC rates as an outcome. Overall compliance increased from 51.0% before the intervention (95% CI 45·1–56·9) to 67.2% after (61·8–72·2). Pires and Pittet (Citation2017) suggested using scenario-based simulation learning to improve education on HH in medical schools. Their recommendation was based on studies finding an improvement in knowledge and attitudes after simulation. They also reported studies highlighting the central role of nurses, who have the most patient contact, in infection control. Simulation scenarios (case based) have been recommended for promoting the WHO HH strategy and used successfully in an emergency room program (Ghazali et al., Citation2018; Tartari et al., Citation2019). Interprofessional education simulation (IPE) scenarios have been introduced to improve hospital infection control skills (Saraswathy et al., Citation2021). Several studies have found simulation effective for teaching infection control to nursing students (Kim et al., Citation2021; Kim & Oh, Citation2015; Luctkar-Flude et al., Citation2014). The aim of the study was to assess the effect of simulation interventions led by nursing students on HCWs’ HHC during a hospital wide campaign. HHC was measured by hospital wide HH monitoring before and after the interventions.

Method

Study design

A prospective three-stage quasi-experimental design with before and after intervention measurements was implemented. The simulation sessions, as interventions, were developed specifically for the present study. This intervention, that was developed and proposed by university nursing department became part of the hospital’s infection control and prevention multi-modal strategy to improve HHC. Each division involved was the intervention group in one period (with before intervention and after intervention HHC assessments), while the other divisions comprised an additional control group.

Study setting

The study took place in a large, 1,150-bed, tertiary-level university affiliated hospital in Israel, serving approximately a one million multi-ethnic rural and urban population, in collaboration with a university nursing department. Four hospital divisions: gynecology, internal medicine, critical care, and surgery in four consecutive periods participated in the intervention. Each division has 3–10 wards, ranging from 8 patient units per ward in critical care, and up to 45 patients’ units in internal medicine. The number of patient beds in each division ranged from 150 to 400 and included a total of approximately 850 out of the total 1150 hospital beds.

Sample

Overall, 67 students and 286 HCWs participated in the simulation sessions, along with two nurse educators. Each HCW participated in one session only. Between 15 and 25 HCWs participated in each session, led by four students with one faculty member. In the first two periods, only nurses and nursing aides participated in the simulation intervention sessions. Physicians were included in the third and fourth period. Participation in simulation sessions rates were calculated as HCWs attending a simulation session out of all HCWs in the division. All HCWs in the hospital were audited by the hospital infection control and prevention program to asses hospital wide HHC.

Students participated as part of an elective clinical research courses / seminars for nursing students in the university’s four-year undergraduate program. An Infection Prevention and Control seminar, one of several offered, aimed at enabling students to investigate a research question using nursing research methodology. Each seminar was attended by 15–20 fourth-year nursing students.

Intervention

The simulation intervention part of this three-stage research design was carried out four times in four different hospital divisions: (1) Period I 2013–2014; (2) Period II 2014–2015; (3) Period III 2015–2016; and (4) Period IV 2016–2017. The intervention consisted of five – six simulation sessions, each approximately 45 min long, attended by mixed personnel from the wards of the participating division, in each of the four periods. The simulation sessions were opened to all HCWs from the division involved in this project during each intervention period. They were repeated once a week for two months, scheduled close to shift handover to encourage maximum participation. Every worker was invited to participate in one session. All interventions took place from mid-November to mid-January in each consecutive year from 2013 to 2017. The observations, HHC audits, were carried out from July until November, and from December until June in each of the four divisions.

The structure of each simulation session included: (1) Short explanation about the activity’s purpose (5–10 min); (2) Two case based scenarios in which up to 4 HCWs actively participated while the other participants were asked to check HH opportunities and HH performance as an educational exercise (10–15 min); (3) Debriefing consistent of discussion regarding which HH opportunities were correctly performed, possible improvements and conclusions and summary of take home messages (10–15 min); (4) Participants verbal and written feedback on the activity (5 min). The interventions were carried out in an available division area in each period. The two nursing faculty members (ILR, NH) together with students and hospital personnel from each division, and the Infection Control unit, were jointly responsible for the organisation and logistics of this intervention. The two nurse faculty members have extensive experience with nursing education and the use of simulation. Hospital personnel contributed to the clinical fidelity of the scenarios. The Infection Control Unit conducts routine HH assessments in all hospital divisions, as recommended by the WHO (World Health Organization, Citation2009) and mandated by the Israeli Ministry of Health (Citation2009).

The students practiced leading HH simulation sessions before the intervention stage. The nursing faculty members prepared the students for leading the simulation sessions using rehearsals, practice and feedback. There was a nurse educator at every session to support students and intervene if necessary. For educational purposes only, the students assessed HHC before and after the intervention, in which they played a key role. This seminar offered students an opportunity to actively participate in a research project and to contribute to evidence based practice in the clinical settings while interacting with hospital personnel in a unique manner.

Standardized simulation sessions based on written scenarios were used to maintain fidelity. Each scenario included an opening scene description and clear routine actions, with expected behaviour and answers or information to give participants when requested. The WHO-based HH form (Israeli Ministry of Health, Citation2009; World Health Organization, Citation2009) is the accepted tool for HH auditing in the Israeli health system. This tool has been studied and found reliable in 19 countries (Stewardson et al., Citation2013) and is considered the gold standard for HHC assessment by the International Society for Infectious diseases (Murthy & Grein, Citation2018).

Simulation scenarios were specifically created for each division in each period of this study. They were developed by two experienced academic nurse educators (ILR, NH), with over twenty years in nursing education and infection control experience, in collaboration with the Infection Control Unit and representatives from each division. The scenarios included actions and interventions performed by personnel during patient care in each division (See Appendix 1 for a sample scenario). Each session included a pre-briefing, intervention, debriefing, and summary. Healthcare workers’ satisfaction with simulation participation was assessed at the end of each session. Satisfaction with the intervention was measured on a 5-point Likert scale (1 – not satisfied at all, 5 – very satisfied) developed by educators and evaluated by other nurse educators and hospital personnel involved in this study. Students also rated their satisfaction with the seminar on a standard satisfaction survey conducted regularly by the university quality of education unit.

This study was approved by the university’s Department of Nursing Research Committee and by the hospital’s IRB (XXX). To preserve the anonymity of the divisions, we labelled them A, B, C, and D in the results.

Outcome measurements

The outcome measurements of this study were HHC rates during the four periods in the four divisions compared to overall hospital compliance. Using standard WHO (World Health Organization, Citation2009) observation form, the hospital’s Infection Control Unit overtly observed HH behaviours before and after interventions. Overt observations, when the observers are easily visible, are an accepted part of hospital monitoring. At least 200 hand hygiene opportunities were observed in each ward during each period, as recommended by the WHO (Citation2009).

Data analysis

Excel software was used for data collection (Microsoft Corporation, Microsoft Excel 2017) and SPSS software for all statistical analyses (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp. 2017). The final dataset was screened for errors and no extreme or nonlogical (i.e. number of opportunities < number of HH performances) values were found. Categorical variables were summarised as frequency and percentages. The main variables of the study are counts such as the number of hand hygiene performed. Therefore, the Poisson regression which allow to model count data was used. The association in the Poisson regression model is reported as Incidence Rate Ratio (IRR). Generalized estimating equations (GEE), is a method for modeling longitudinal or clustered data and usually used with non-normal data such as count data. Therefore, GEE model with Poisson distribution, log link function, and natural log of the opportunities for HHC as an offset term was used to calculate the IRR and to estimate the differences between groups before and after the intervention, while adjusting for month of the year. Intervention (yes/no), time (before/after), intervention-time interaction and month of the year were included in the model. Relative effect sizes were interpreted as described by Olivier et al. (Citation2017). All statistical tests were two-sided and p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

A total of 81,051 opportunities for HHC of all HCWs in the wards were observed over the course of the four periods of this study. HCWs’ participation in the simulation sessions ranged from 10.8% (Period II) to 64.6% (Period III); overall participation was 27.1% ().

Table 1. Number of students leading HH simulation sessions, and percentage of HCWs participation, by period.

In each period of the study, HHC rates were evaluated for group type (intervention or control), time (before or after the intervention) and month (reflecting the hospital’s seasonal load). During the years of the study, there was a significant rise in HHC rates (IRR 1.336, 1.803, 2.139, from Period II, III and IV, respectively, p < 0.001) when compared to the beginning, Period I (). Therefore, the repeated measurement analysis was conducted separately for each period. In three of the four periods (period I, II, and IV) there was a significantly positive gain in HHC after intervention compared to the control group, representing a small to medium effect size (IRR 1.409; 1.032; 1.045, respectively, p < 0.001, ). In period III, despite HHC improvement in the control group (from 57% to 70%), no change in HHC rate was observed in the intervention group (). demonstrates the HHC rates before and after intervention in both groups in each period.

Table 2. Increase in hand hygiene compliance rate by period* 2013–2017.

Table 3. Hand hygiene compliance before and after simulation sessions in each division and control, by period* 2013–2017.

Most simulation participants (260/286, 90.1%) expressed satisfaction with this intervention, with a mean score of 4.6 (± 0.4). Many participants added a short sentence of appreciation for this intervention and recognition of the importance of HHC. No one felt that the simulation sessions were unnecessary or unhelpful. Several staff members expressed interest in additional meetings as “booster” sessions at reasonable intervals. Students rated this seminar as positive (4.66–4.8, from 5 maximum) in satisfaction surveys, conducted at the end of each semester.

Discussion

Simulation is one of many interventions widely used in healthcare to improve HHC and other aspects of clinical quality improvement (Ghazali et al., Citation2018; Orledge et al., Citation2012; Saraswathy et al., Citation2021). In this study HHC increased significantly more in the intervention groups compared to the overall hospital improvement in three out of four periods (IRR 1.049, 1.032, 1.045, Period I, II, and IV, respectively, p < 0.001). This finding represents small to medium effect size of the current intervention and adds to the literature demonstrating the effectiveness of simulation for improving quality in healthcare (Orledge et al., Citation2012; Ortega et al., Citation2018; Zhang et al., Citation2018). It is noteworthy that this improvement was above the hospital-wide increase in HH compliance, attributable to the Infection Control Unit, whose activities included continual monitoring, feedback, and posters. The persistent increase in HH compliance throughout this study demonstrates the value of continuous, multi-model interventions to improve HH compliance, supporting similar previous findings (Doronina et al., Citation2017; Moghnieh et al., Citation2017; Rees et al., Citation2013).

We used the WHO’s (Citation2009) Five Moments model for both debriefing and feedback during the intervention and as an observation tool (Israeli Ministry of Health, Citation2009) in accordance with previous research (Allegranzi et al., Citation2013; Kilpatrick et al., Citation2018; Kingston et al., Citation2017). The specific gain in HHC after the simulation sessions highlights the intervention's effectiveness in three out of four divisions; the general trend of HHC improvement can be attributed to both the intervention and hospital infection control and prevention activities. This effect may be partially explained by the dissemination of knowledge and expected behaviours created by the modeling of HCWs who participated in the sessions.

In the present study, nursing supervisors and medical leaders were committed and involved, which may have contributed to the percentage of personnel participating in the simulation activities. Previous literature also emphasised the importance of management and team leaders’ support and involvement in HH interventions (Huis et al., Citation2013; Lieber et al., Citation2014). This commitment enabled an organisational climate which encouraged HCWs to participate in simulation sessions. These provided participants an opportunity to zoom into the challenges and principles of hand hygiene and with the means to better comply with hand hygiene guidelines. As found in other studies, personal feedback for hand hygiene behaviours during intervention sessions is one of the effective strategies to improve compliance (Moghnieh et al., Citation2017; Shlomai et al., Citation2015; Walker et al., Citation2014).

Having the simulation sessions within the hospital wards may have attracted the attention of a larger number of personnel, so that not only the participants gained from this intervention. The increase in HH compliance in three of the study’s period (1, 2, and 4), despite participation rates (37%, 10.8%, 64.4%, 22.6% in Period 1, 2, 3 and 4, respectively) may indicate that participants shared their experiences and thoughts with their colleagues. This created a spillover effect, namely, heightening the general awareness of the issue and thus contributing to improvement (Howard et al., Citation2018; Pearson et al., Citation2015). However, in one of the four study periods, period 3, a significant decrease in HHC was observed. This finding may be associated with the high HHC within the division during this time period. In addition, there was a dramatic hospital-wide gain in HH compliance, from 55% to 70%, possibly due to an accelerated hospital infection control campaign and previous successful intervention in this division.

The simulation intervention was a major component of the nursing student research-clinical seminar. Students rated this seminar as positive (4.66–4.8, from 5 maximum) in satisfaction surveys, conducted at the end of each semester. They felt empowered by their ability to carry out this project within the hospital with healthcare workers, a feeling that was found in previous studies (Bell et al., Citation2015; Kennedy et al., Citation2015). This unique flipped classroom design implemented in this study allowed students to teach HCWs in the clinical setting. The common practice of this strategy occurs within the classroom (Barbour & Schuessler, Citation2019). In this study students organised and led the simulation sessions in the hospital, although the sessions were designed by educators. This kind of collaboration can strengthen the relationships and involvement between academia and the clinical healthcare services and is mutually beneficent to all participants. Kalogirou et al. (Citation2020) concluded their qualitative study, after intervening 36 administrators, with the need for more collaboration between the practice and education to bridge the theory–practice gap by creating more touch points with one another. The collaboration between students, faculty and the Infection Control Unit is a prolific ground for mutual benefit and the creation of shared objectives. To the best of our knowledge this is the first student-led simulation intervention for HHC improvement reported in the literature.

The organisation of this intervention was an effective educational endeavour for students and a meaningful collaboration between the in the university nursing department and the hospital. This partnering requires continuous investment on both sides. Using simulation to improve HHC was effective and well received. Even small participation rates of healthcare workers in the simulation led to overall compliance gains. The subsequent involvement of physicians in this study reflected recognition by the hospital management of the importance of this intervention. Furthermore, this recognition validates simulation as an effective method in multi-modal HHC strategies.

Limitations

We acknowledge several limitations of our study. First, our study was conducted during a hospital wide campaign for hand hygiene improvement that included posters and educational talks. The simulation sessions were a unique addition to the overall efforts. Thus, it is hard to conclude if our intervention would have been successful without the campaign. Secondly, as this study evolved over the years, there were some changes that should be considered. Only nurses and nursing aids participated in the simulation in the first two period. The last two periods also included physicians. This change affected the development and execution of the scenarios for those divisions. Only part of HCWs in each unit participated in the simulation sessions although all were invited which may present a selection/ participation / uptake bias, a third limitation. Fourthly, HH observations were conducted on all HCWs, not necessarily including those who had participated in the simulation. However, the fundamental assumption of the study design is that a change in a social-behavioral norm e.g. hand hygiene will be reflected in all unit personnel, not just individuals participated in the simulation sessions.

Conclusions

In conclusion, student led simulation for HHC was found to contribute to a wider hospital campaign. Further HHC improvement strategies could consider including student led simulations as part of hospital quality improvement efforts. Nursing managers may look at joining forces with nursing educators and teaming up to make students agents of change in the healthcare settings. Students and HCWs benefit from this unique arrangement, gaining educational experiences.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Allegranzi, B., Gayet-Ageron, A., Damani, N., Bengaly, L., McLaws, M.-L., Moro, M.-L., & Pittet, D. (2013). Global implementation of WHO's multimodal strategy for improvement of hand hygiene: A quasi-experimental study. Lancet Infectious Diseases, 13(10), 843–851. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70163-4

- Al-Maani, A., Al Wahaibi, A., Al-Zadjali, N., Al-Sooti, J., AlHinai, M., Al Badawi, A., … Al-Abri, S. (2022). The impact of the hand hygiene role model project on improving healthcare workers’ compliance: A quasi-experimental observational study. Journal of Infection and Public Health, 15(3), 324–330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiph.2022.01.017

- Barbour, C., & Schuessler, J. B. (2019). A preliminary framework to guide implementation of the flipped classroom method in nursing education. Nurse Education in Practice, 34, 36–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2018.11.001

- Bell, K., Tanner, J., Rutty, J., Astley-Pepper, M., & Hall, R. (2015). Successful partnerships with third sector organisations to enhance the healthcare student experience: A partnership evaluation. Nurse Education Today, 35(3), 530–534. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2014.12.013

- Bredin, D., O’Doherty, D., Hannigan, A., & Kingston, L. (2022). Hand hygiene compliance by direct observation in physicians and nurses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Hospital Infection, 130, 20–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhin.2022.08.013

- Cantrell, M. A., Franklin, A., Leighton, K., & Carlson, A. (2017). The evidence in simulation-based learning experiences in nursing education and practice: An umbrella review. Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 13(12), 634–667. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecns.2017.08.004

- Choi, G. Y., Wan, W. T., Chan, A. K., Tong, S. K., Poon, S. T., & Joynt, G. M. (2020). Preparedness for COVID-19: In situ simulation to enhance infection control systems in the intensive care unit. British Journal of Anaesthesia, 125(2), e236–e239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2020.04.001

- Dixon-Woods, M., & Lame, G. (2018). Using clinical simulation to study how to improve quality and safety in healthcare. BMJ Simulation and Technology Enhanced Learning.

- Doronina, O., Jones, D., Martello, M., Biron, A., & Lavoie-Tremblay, M. (2017). A systematic review on the effectiveness of interventions to improve hand hygiene compliance of nurses in the hospital setting. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 49(2), 143–152. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnu.12274

- Erasmus, V., Huis, A., Oenema, A., van Empelen, P., Boog, M. C., van Beeck, E. H. E., Polinder, S., Steyerberg, E. W., Richardus, J. H., Vos, M. C., & van Beeck, E. F. (2011). The ACCOMPLISH study. A cluster randomised trial on the cost-effectiveness of a multicomponent intervention to improve hand hygiene compliance and reduce healthcare associated infections. BMC Public Health, 11, Article 721. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-721

- Garber, A., Rao, P. M., Rajakumar, C., Dumitrascu, G. A., Rousseau, G., & Posner, G. D. (2018). Postpartum magnesium sulfate overdose: A multidisciplinary and interprofessional simulation scenario. Cureus, 10(4), e2446. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.2446

- Ghazali, D. A., Thomas, J., Deilhes, E., Laland, C., Thévenot, S., Richer, J. P., & Oriot, D. (2018). Design and validation of an anatomically based assessment scale for handwashing with alcohol-based hand rub. Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology, 39(8), 1000–1002. https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2018.119

- Gould, D. J., Moralejo, D., Drey, N., Chudleigh, J. H., & Taljaard, M. (2017). Interventions to improve hand hygiene compliance in patient care. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 9(9), CD005186.

- Howard, R., Alameddine, M., Klueh, M., Englesbe, M., Brummett, C., Waljee, J., & Lee, J. (2018). Spillover effect of evidence-based postoperative opioid prescribing. Journal of the American College of Surgeons, 227(3), 374–381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2018.06.007

- Huis, A., Holleman, G., van Achterberg, T., Grol, R., Schoonhoven, L., & Hulscher, M. (2013). Explaining the effects of two different strategies for promoting hand hygienein hospital nurses: A process evaluation alongside a cluster randomised controlled trial. Implementation Science, 8, Article 41. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-8-41

- Israeli Ministry of Health. (2009). Hand hygiene in hospital settings. Retrieved 23 April 2020 at https://www.health.gov.il/hozer/mr24_2009.pdf (Hebrew).

- Kalogirou, M. R., Chauvet, C., & Yonge, O. (2020). Including administrators in curricular redesign: How the academic–practice relationship can bridge the practice–theory gap. Journal of Nursing Management, 29(4), 635–641. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.13209

- Kennedy, S., Hardiker, N., & Staniland, K. (2015). Empowerment an essential ingredient in the clinical environment: A review of the literature. Nurse Education Today, 35(3), 487–492. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2014.11.014

- Kibira, J., Kihungi, L., Ndinda, M., Wesangula, E., Mwangi, C., Muthoni, F., … Njoroge, A. (2022). Improving hand hygiene practices in two regional hospitals in Kenya using a continuous quality improvement (CQI) approach. Antimicrobial Resistance & Infection Control, 11, Article 56. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13756-022-01093-z

- Kilpatrick, C., Tartari, E., Gayet-Ageron, A., Storr, J., Tomczyk, S., Allegranzi, B., & Pittet, D. (2018). Global hand hygiene improvement progress: Two surveys using the WHO hand hygiene self-assessment framework. Journal of Hospital Infection, 100(2), 202–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhin.2018.07.036

- Kim, E., Kim, S. S., & Kim, S. (2021). Effects of infection control education for nursing students using standardized patients vs. peer role-play. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18, Article 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18010107

- Kim, K. M., & Oh, H. (2015). Clinical experiences as related to standard precautions compliance among nursing students: A focus group interview based on the theory of planned behavior. Asian Nursing Research, 9(2), 109–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anr.2015.01.002

- Kingston, L. M., O'Connell, N. H., & Dunne, C. P. (2017). Survey of attitudes and practices of Irish nursing students towards hand hygiene, including handrubbing with alcohol-based hand rub. Nurse Education Today, 52, 57–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2017.02.015

- Kolb, D. A. (2014). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development (pp. 32–36). FT Press.

- Lateef, F., Stawicki, S. P., Xin, L. M., Krishnan, S. V., Sanjan, A., Sirur, F. M., … Galwankar, S. (2020). Infection control measures, in situ simulation, and failure modes and effect analysis to fine-tune change management during COVID-19. Journal of Emergencies, Trauma, and Shock, 13(4), 239–245. https://doi.org/10.4103/JETS.JETS_119_20

- Lieber, S. R., Mantengoli, E., Saint, S., Fowler, K. E., Fumagalli, C., Bartolozzi, D., … Bartoloni, A. (2014). The effect of leadership on hand hygiene: Assessing hand hygiene adherence prior to patient contact in 2 infectious disease units in Tuscany. Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology, 35(3), 313–316. https://doi.org/10.1086/675296

- Luctkar-Flude, M., Baker, C., Hopkins-Rosseel, D., Pulling, C., McGraw, R., Medves, J., … Brown, C. A. (2014). Development and evaluation of an interprofessional simulation-based learning module on infection control skills for prelicensure health professional students. Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 10(8), 395–405. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecns.2014.03.003

- Moghnieh, R., Soboh, R., Abdallah, D., El-Helou, M., Al Hassan, S., Ajjour, L., … Mugharbil, A. (2017). Health care workers’ compliance to the My 5 moments for hand hygiene: Comparison of 2 interventional methods. American Journal of Infection Control, 45(1), 89–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2016.08.012

- Moro, M. L., Morsillo, F., Nascetti, S., Parenti, M., Allegranzi, B., Pompa, M. G., & Pittet, D. (2014). Determinants of success and sustainability of the WHO multimodal hand hygiene promotion campaign, Italy, 2007–2008 and 2014. Eurosurveillance, 22(23), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2017.22.23.30546

- Mouajou, V., Adams, K., DeLisle, G., & Quach, C. (2022). Hand hygiene compliance in the prevention of hospital-acquired infections: A systematic review. Journal of Hospital Infection, 119, 33–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhin.2021.09.016

- Murthy, R., & Grein, J. (2018). Hand hygiene monitoring. In Z. A. Memish (Ed.), Guide to infection control in healthcare settings. International Society for Infectious Disease. https://isid.org/guide/infectionprevention/hand-hygiene-monitoring/.

- Olivier, J., May, W. L., & Bell, M. L. (2017). Relative effect sizes for measures of risk. Communications in Statistics-Theory and Methods, 46(14), 6774–6781. https://doi.org/10.1080/03610926.2015.1134575

- O’Regan, S., Molloy, E., Watterson, L., & Nestel, D. (2016). Observer roles that optimise learning in healthcare simulation education: A systematic review. Advances in Simulation, 1, Article 4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41077-015-0004-8.

- Orledge, J., Phillips, W. J., Murray, W. B., & Lerant, A. (2012). The use of simulation in healthcare: From systems issues, to team building, to task training, to education and high stakes examinations. Current Opinion in Critical Care, 18(4), 326–332. https://doi.org/10.1097/MCC.0b013e328353fb49

- Ortega, J., Gonzalez, J. M., de Tantillo, L., & Gattamorta, K. (2018). Implementation of an in-hospital stroke simulation protocol. International Journal of Health Care Quality Assurance, 31(6), 552–562. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJHCQA-08-2017-0149

- Pearson, M. L., Wyte-Lake, T., Bowman, C., Needleman, J., & Dobalian, A. (2015). Assessing the impact of academic-practice partnerships on nursing staff. BMC Nursing, 14(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-015-0085-7

- Pires, D., & Pittet, D. (2017). Hand hygiene mantra: Teach, monitor, improve, and celebrate. Journal of Hospital Infection, 95(4), 335–337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhin.2017.03.009

- Rees, S., Houlahan, B., Safdar, N., Sanford-Ring, S., Shore, T., & Schmitz, M. (2013). Success of a multimodal program to improve hand hygiene compliance. Journal of Nursing Care Quality, 28(4), 312–318. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCQ.0b013e3182902404

- Rosqvist, E., Lauritsalo, S., & Paloneva, J. (2019). Short 2-H in situ trauma team simulation training effectively improves non-technical skills of hospital trauma teams. Scandinavian Journal of Surgery, 108(2), 117–123. https://doi.org/10.1177/1457496918789006

- Saraswathy, T., Nalliah, S., Rosliza, A., Ramasamy, S., Jalina, K., Shahar, H. K., & Amin-Nordin, S. (2021). Applying interprofessional simulation to improve knowledge, attitude and practice in hospital-acquired infection control among health professionals. BMC Medical Education, 21(1), 1–11. URL: shorturl.at/fwM58. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-02907-1

- Sawyer, T., Eppich, W., Brett-Fleegler, M., Grant, V., & Cheng, A. (2016). More than one way to debrief: A critical review of healthcare simulation debriefing methods. Simulation Healthcare, 11(3), 209–217. https://doi.org/10.1097/SIH.0000000000000148

- Shlomai, N. O., Rao, S., & Patole, S. (2015). Efficacy of interventions to improve hand hygiene compliancein neonatal units: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Disease, 34(5), 887–897. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-015-2313-1

- Siegel, J. D., Rhinehart, E., Jackson, M., & Chiarello, L. (2007). Health care infection control practices advisory committee. Guideline for isolation precautions: Preventing transmission of infectious agents in health care settings. American Journal of Infection Control, 35(10), s53–s164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2007.10.007

- Staines, A., Amherdt, I., Lécureux, E., Petignat, C., Eggimann, P., Schwab, M., & Pittet, D. (2017). Hand hygiene improvement and sustainability: Assessing a breakthrough collaborative in Western Switzerland. Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology, 38(12), 1420–1427. https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2017.180

- Stewardson, A. J., Allegranzi, B., Perneger, T. V., Attar, H., & Pittet, D. (2013). Testing the WHO hand hygiene self-assessment framework for usability and reliability. Journal of Hospital Infection, 83(1), 30–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhin.2012.05.017

- Tartari, E., Fankhauser, C., Peters, A., Sithole, B. L., Timurkaynak, F., Masson-Roy, S., … Pittet, D. (2019). Scenario-based simulation training for the WHO hand hygiene self-assessment framework. Antimicrobial Resistance & Infection Control, 8(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13756-018-0426-x

- Walker, J. L., Sistrunk, W. W., Higginbotham, M. A., Burks, K., Halford, L., Goddard, L., … Finley, P. J. (2014). Hospital hand hygiene compliance improves with increased monitoring and immediate feedback. American Journal of Infection Control, 42(10), 1074–1078. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2014.06.018

- World Health Organization. (2009). WHO guidelines on hand hygiene in health care. http://whqlibdoc. WHO. int/publications/2009/9789241597906_eng.pdf.

- Zhang, C., Grandits, T., Härenstam, K. P., Hauge, J. B., & Meijer, S. (2018). A systematic literature review of simulation models for non-technical skill training healthcare logistics. Advances in Simulation, 3, Article 15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41077-018-0072-7

Appendix

1. Hand hygiene scenario

Example: A part of a typical session.

Opening – explanation of activity and short reminder of the “5 moments for hand hygiene”.

Description (read to participants, volunteers requested): Two post-operative patients.

Mrs. Sara Dahan, 71, COPD, 1 d after Rt. Hemicolectomy, dry wound dressing, hemovac drain, IV fluids, naso-gastric tube.

Mrs. Etty Zinger, 4 days after subtotal gastrectomy, IV fluids, TPN, surgical wound leaking small amount of serotic fluid, abdomen distended, patient in noticeable discomfort.

Scene: Beginning of evening shift. Nurse with mobile computer and care cart enters room to measure vital signs, assess wounds and drains; nurse aide replenishes supplies; doctor in hall writing orders.

All observing participants write down hand hygiene indications and opportunities as they think correct.

Debriefing: request reactions from participants, others, comments.

Discuss hand hygiene indications, where problems arise during work and possible solutions/ improvement.