Abstract

Background

Internationally, the nursing workforce is ageing. Chronic conditions are becoming more prevalent amongst the ageing nursing workforce. With an increase in chronic conditions and an ageing nursing workforce, understanding environmental influences on nurses’ health and work capacity is vital to supporting this workforce.

Aim

A scoping review was conducted to explore the influence of a critical care environment on nurses’ health and work capacity.

Design

A scoping review was conducted according to PRISMA-ScR guidelines.

Methods

Database extraction occurred in June 2023 and included MEDLINE Complete, PubMed, Scopus, CINAHL, and Embase.

Results

Eight studies met the inclusion criteria. Studies were conducted internationally with sample sizes from 20 to 500 critical care nurses (CCNs).

Conclusions

Findings identified the critical care environment had an impact on nurses’ health and working capacity. Many CCNs self-reported having a chronic condition that influenced their nursing practice. Further research is needed to explore how to mitigate the influence of a chronic condition to support this valuable workforce.

Impact statement

This research highlights the growing prevalence of chronic conditions in the nursing population. Chronic conditions were prevalent amongst critical care nurses (CCNs) in this study, and this research adds that this influenced their work capacity. This study found that the critical care work environment can adversely influence the physical and psychological health and well-being of nurses. Poor physical health including conditions such as fatigue and musculoskeletal pain influenced absenteeism and a nurse’s intention to leave the critical care specialty. Poor psychological health influenced role management and clinical decision-making. Further research is needed to explore ways to better support a CCNs’ health and wellbeing. Particularly, the ageing nurse population to mitigate the influence of a chronic condition and optimise the recruitment and retention of this valuable nursing workforce.

Plain language summary

Nurses face a multitude of challenges in adopting healthy lifestyle habits due to the physically and emotionally demanding nature of their work. With an increase in chronic conditions, an ageing nursing workforce and patient complexity the nurses’ health status and well-being will be vital to sustaining the nursing workforce. This review highlights that chronic conditions and poor health exist amongst CCNs. The elevated levels of poor health and chronic conditions amongst nurses pose serious concerns over the sustainability of the current critical care nursing role and worldwide retention and recruitment challenges. More research is needed to inform organisational leaders on how best to enhance the critical care environment to support CCNs with chronic conditions or suboptimal health to improve nursing practice and patient care.

Introduction

Internationally, the nursing workforce is ageing (Buerhaus, Citation2005, p. 55; RCN, Citation2016; Ryan et al., Citation2019). For example, in the Republic of Ireland, 65% of all nurses are aged over 40 years and more than 30% are aged over 50 years (Health Service Executive, Citation2017); in the United States of America, it is estimated that 50% of nurses are aged over 50 years (Buerhaus et al., Citation2000); and in Canada and the United Kingdom, 38.9% and 34.5%, respectively, of nurses are over 50 years (Ryan et al., Citation2019). In Australia, of the registered nurses working clinically, 82,609 (29.7%) are over the age of 50 years and approaching the later stages of their career (AIHW, Citation2020; Phillips & Miltner, Citation2015; Ryan et al., Citation2019). Some challenges with an ageing nursing workforce include an increased risk of chronic conditions potentially impacting on recruitment, retention, and work capacity. This is of particular concern for critical care areas that are facing increasing workforce shortages.

As nurses age, nursing can become a physically and emotionally demanding profession, especially in critical care environments where the complexity of the role includes managing patients with life-threatening events (Lim et al., Citation2010). Hence, there are recognised challenges faced by older nurses in the workplace related to the physical and psychological strain of providing direct patient care (Ryan et al., Citation2019). Critical care areas are recognised to have increased occupational stress, which can result in poor health choices by nurses and potentially increase the development of chronic conditions (Chegini et al., Citation2019; Perry et al., Citation2015; Steege & Pinekenstein, Citation2016). However, how the presence of an acute or chronic health condition alters the critical care nurse’s capacity to undertake their role and meet the expectations of the work environment remains largely unknown. Therefore, the aim of the scoping review was to map and critique the literature exploring the influence of a critical care environment on nurses’ acute or chronic physical and psychological health, well-being, and work capacity.

Background

Challenging work conditions in critical care could have a causal link to the development of chronic conditions and negatively impact nurses’ physical and psychological health (Daouda et al., Citation2021). The work environment and nurses’ role expectations are potential barriers to healthy self-management behaviours, thereby increasing the risk of developing poor health and/or chronic conditions (Brennan, Citation2017; Peplonska et al., Citation2014). General ward nurses have previously self-reported that occupational stress has either contributed to or exacerbated a chronic physical condition (Lukan et al., Citation2022). Occupational stress is a physiological response; when one’s ability is not at the standard required to manage workload expectations and environmental pressures (Quick & Henderson, Citation2016). In nursing, occupational stress is a universally recognised stressor often challenged by unsustainable workloads and shift patterns (Lim et al., Citation2010). The ongoing exposure to occupational stresses such as short-staffing, high workforce turnover, role demands, and emotional exhaustion (Opie et al., Citation2011) potentially impact a nurse’s health and their ability to practice (Sarafis et al., Citation2016; Steege & Pinekenstein, Citation2016). Critical care nurses (CCNs) have been reported to experience significantly higher levels of occupational stress compared to other specialties (Chegini et al., Citation2019). This poses numerous challenges to the sustainability of the critical care nursing workforce.

Sustaining a healthy nursing workforce is central to the delivery of high-quality nursing and safe patient care. Whilst the epidemiology of chronic conditions is reported in the general nursing workforce, there is limited evidence describing the presence of chronic conditions within the critical care nursing workforce. There is a paucity of evidence of how the environment and the presence of a health condition alter the critical care nursing practice and work capacity. Understanding the critical care workforce needs and considerations to better support the nurses’ health and working capacity are necessary given the global increase in chronic conditions, an ageing nursing workforce and retention challenges (Steege & Pinekenstein, Citation2016; WHO, Citation2014).

Aim

The aim of the scoping review was to map and critique the literature exploring the influence of a critical care environment on nurses’ acute or chronic physical and psychological health, well-being, and work capacity.

Methods

The scoping review was conducted in accordance with the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) methodological guidance when conducting scoping reviews (Peters et al., Citation2020). A scoping review was determined as the best approach to answer the research question due to the need to map out the available evidence and identify evidence gaps in the literature. The five-step framework by Peters et al. (Citation2020) was adopted for this scoping review and included (1) identification of a research question; (2) identification of relevant studies through a pilot literature search identifying keywords; (3) study screening and selection; (4) data extraction and summarisation, and (5) reporting.

For this review, the chronic condition was defined as being of long duration, slow in progression, and not passed from person to person (WHO, Citation2014). A physical symptom is defined as a physical indication of a bodily condition that is ongoing in nature and can be perceived by a patient or clinician (Martin & McFerran, Citation2008).

Eligibility criteria

The eligibility criteria for this scoping review included peer-reviewed literature; English language, and registered nurses working in critical care environments. A critical care environment was defined as intensive care units, emergency departments, coronary care, interventional suites, and perioperative (ACI, Citation2021). All research designs were included. Grey literature and studies reporting on nurses working in non-critical care areas were excluded.

Search strategy

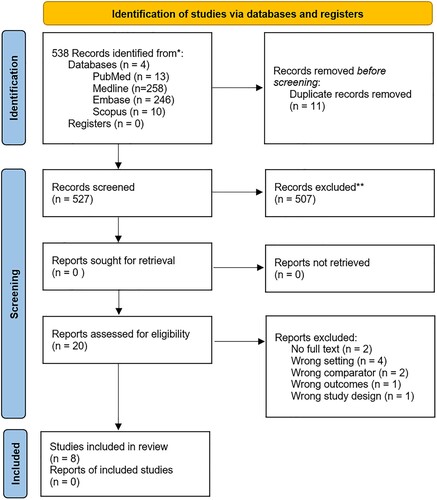

A systematic search was conducted of five databases: PubMed, MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, and Scopus in June 2023. No predefined date limiter was applied. The search strategy was reviewed by a librarian and three researchers. Text words contained in the titles and abstracts of relevant articles and index terms from a pilot search were then used to develop a full search strategy ().

Table 1. Search terms applied across databases.

Terms were selected for each database and included chronic disease, chronic conditions, and chronic illness, health status, physical health or health, critical care, nurs*, and nurse workforce. Search terms were modified by using Boolean operators “or” and “and”; then, the titles were screened. For example, Embase was searched using the following search terms: critical care nurse.mp.; emergency nurse.mp.; acute care nurse.mp.; workforce/ or nursing/ or nursing staff/; health status.mp. or health status/; physical health.mp. or health/ and chronic disease/ or chronic symptoms.mp.

The initial search was performed, and title/abstract screening was conducted by two researchers with any conflicts resolved through discussion or a third reviewer. Duplicates were removed. In addition, a manual search of reference lists was undertaken after the abstract screening process. All identified citations were collated and uploaded into COVIDENCE, a web-based tool that streamlines the screening and data extraction processes when conducting scoping reviews (Veritas Health Innovation, Citation2023).

Relevant sources were retrieved in full and assessed for quality using the JBI quality appraisal tool for cross-sectional studies (JBI, Citation2014) (). The full texts of selected citations were assessed against the inclusion criteria by two reviewers (AL and MF). Then, data were extracted from papers by two independent reviewers (AL and MF) using a data extraction table. The PRISMA-ScR flowchart () reports inclusion and exclusion of sources of evidence. Mapping and aligning of the findings were synthesised into three themes: (i) the impact of critical care work environments on nurses’ physical health; (ii) a CCNs’ psychological well-being; and (iii) the capacity to undertake the nursing role in critical care.

Table 2. Assessment of quality appraisal of scoping review studies. Appraisal tool: JBI quality appraisal tool for cross-sectional studies.

Results

Eight studies involving a sample of 1278 CCNs were included in this scoping review. The studies were conducted in the United States of America (n = 2), Spain (n = 2), Brunei (n = 1), Egypt (n = 1), Taiwan (n = 1), and Iran (n = 1). Four of the eight studies were single-site centres (Arrogante & Aparicio-Zaldivar, Citation2017; Eldin et al., Citation2021; Imes & Chasens, Citation2019; Ruggiero, Citation2003) while four were multi-centred studies (Chen et al., Citation2019; Marti-Ejarque et al., Citation2021; Rahman et al., Citation2016; Rostamabadi et al., Citation2017). All studies (n = 8) utilised a cross-sectional research design, and the quality of evidence was identified as level four according to the JBI Quality Appraisal for cross-sectional design (JBI, Citation2014). Level-four evidence primarily consists of observational-descriptive studies that describe patterns, associations, or individual cases. It is important to consider the limitations of these study designs when interpreting their findings (JBI, Citation2014). No systematic reviews, scoping reviews, or randomised control trials were identified.

The work environments included intensive care, emergency departments, operating theatre, coronary care, and high dependency (). Twenty-one instruments were used across the eight studies. With studies using up to three instruments in a survey. Of the 21 instruments, eight of the instruments (38%) were validated and used to measure general health in nurses (Arrogante & Aparicio-Zaldivar, Citation2017; Eldin et al., Citation2021; Marti-Ejarque et al., Citation2021); fatigue and sleep quality (Rostamabadi et al., Citation2017; Ruggiero, Citation2003); depression and anxiety (Ruggiero, Citation2003); and the impact of workload (Rostamabadi et al., Citation2017; Ruggiero, Citation2003). Three themes were synthesised during data analysis: (i) the impact of critical care work environments on nurses’ physical health; (ii) a CCNs’ psychological well-being; and (iii) the capacity to undertake the nursing role in critical care ().

Table 3. Summary of included quantitative studies (n = 8).

Table 4. Contents of data themes.

Theme 1: the impact of critical care work environment on nurses’ physical health

Across the studies, the impact of the critical care environment influenced a nurse’s physical health. Physical symptoms and chronic conditions were reported across six out of the eight studies in this review (Chen et al., Citation2019; Eldin et al., Citation2021; Imes & Chasens, Citation2019; Marti-Ejarque et al., Citation2021; Rahman et al., Citation2016; Rostamabadi et al., Citation2017). The speciality studied most commonly were intensive care (n = 418) (Imes & Chasens, Citation2019; Rahman et al., Citation2016; Ruggiero, Citation2003), followed by emergency (n = 322) (Chen et al., Citation2019; Rahman et al., Citation2016; Ruggiero, Citation2003) and the operating room (n = 165) (Eldin et al., Citation2021; Marti-Ejarque et al., Citation2021).

A range of physical symptoms were reported and included: fatigue (Chen et al., Citation2019; Eldin et al., Citation2021; Rahman et al., Citation2016; Ruggiero, Citation2003); musculoskeletal pain (Eldin et al., Citation2021; Marti-Ejarque et al., Citation2021; Rostamabadi et al., Citation2017); and headache or migraine (Eldin et al., Citation2021; Rahman et al., Citation2016). The presence of chronic conditions self-reported by nurses working in critical care was evident and included cardiovascular disease (Chen et al., Citation2019; Eldin et al., Citation2021; Marti-Ejarque et al., Citation2021; Rahman et al., Citation2016), diabetes, thyroid conditions (Imes & Chasens, Citation2019; Marti-Ejarque et al., Citation2021; Rahman et al., Citation2016), chronic skin conditions such as dermatitis (Marti-Ejarque et al., Citation2021; Rostamabadi et al., Citation2017), respiratory conditions such as asthma (Imes & Chasens, Citation2019; Rahman et al., Citation2016), chronic gastrointestinal conditions (n = 2) (Chen et al., Citation2019; Rostamabadi et al., Citation2017), and chronic headache conditions including migraines (n = 2) (Eldin et al., Citation2021; Rahman et al., Citation2016).

Chen et al. (Citation2021) in Taiwan conducted a multi-centre study across four hospitals and explored if chronic conditions were perceived to influence role performance in emergency nurses (n = 222). Over 50% (n = 127) of emergency nurses self-reported chronic conditions. The chronic conditions reported included varicose veins (11.7%, n = 26), gastrointestinal disease (9.9% n = 22), hepatitis B and hepatitis C (6.8%, n = 15), herniated intervertebral disc (6.3%, n = 14), cardiovascular disease (5.9%, n = 13), urinary conditions (4.1%, n = 9), and liver disease (1.8%, n = 4) (Chen et al., Citation2019). Similarly, Rahman et al. (Citation2016) in Brunei Darussalam conducted a multi-centre study across four hospitals with emergency (n = 100) and intensive care nurses (n = 101). The authors used a validated Occupational Fatigue Exhaustion/Recovery tool to measure work-related fatigue and psychosocial factors. A fifth of participants (n = 40, 20%) reported the presence of hypertension, diabetes, high cholesterol, asthma, and migraines along with workplace fatigue (Rahman et al., Citation2016).

Some nursing specialties are more involved than others in regularly lifting and transferring patients, working in poor postures, and standing for long hours, which can lead to the development of musculoskeletal disorders (Rostamabadi et al., Citation2017). Marti-Ejarque et al. (Citation2021) in Spain conducted a multi-centred study to investigate the impact of an operating room environment compared to a general ward environment on nurses’ (n = 331) health. The validated tools Modified Scale Short Form Health Survey 12.20 and Short Form Health Survey SF36 tool were used. The authors found a significant difference in musculoskeletal conditions (p < 0.009) and dermatitis (p < 0.026) for nurses working in an operating room environment compared to a general ward setting. Nurses working in the operating room environment (n = 165) reported a higher percentage of chronic conditions compared to general ward-based nurses (n = 166) including musculoskeletal pain (42.6%, n = 40 versus 25.2%, n = 27) and lower back pain (73.4%, n = 71 versus 66.4%, n = 69). Additionally, operating room nurses reported a higher prevalence of fertility problems (9.0%, n = 15 versus 7%, n = 10) and thyroid conditions (7%, n = 12 versus 4%, n = 7) compared to general ward nurses (Marti-Ejarque et al., Citation2021).

CCNs often perform physical activities as part of their role, which can contribute to workplace fatigue (Rahman et al., Citation2016). In a single-centre study, Eldin et al. (Citation2021) compared nurses (n = 160) working in outpatient departments (n = 80) and intensive care and operating room nurses (n = 80) in Egypt. The multi-modal study used a validated General Health Questionnaire tool and biomarkers (blood samples) to report on and measure the health effects of occupational stress. Findings identified that 85% (n = 68) of intensive care and operating room nurses had higher rates of fatigue compared with outpatient department nurses (p < 0.0001). Also, there was a statistically significant difference reported for physical symptoms such as lower back pain (p < 0.0001), headache (p < 0.0001), and hypertension (p < 0.0001) for CCNs when compared with outpatient department nurses (Eldin et al., Citation2021). The critical care environment was shown to influence the physical health of nurses when compared to the general nurse population.

Ruggiero (Citation2003) in the United States of America conducted a single-centre study with nurses in critical care settings such as intensive care, coronary care, emergency, recovery, or cardiac catheterisation laboratory (n = 142). The survey included the validated Standard Shift Work Index Chronic Fatigue Scale; Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; Beck Depression Inventory-II; and Beck Anxiety Index tools to explore contributing factors of chronic fatigue. The author reported that 68% (n = 97) of nurses self-reported that sleep disturbances were commonly experienced and contributed to chronic fatigue. Whilst this study is dated, it is reported that CCNs commonly reported fatigue, general tiredness, and a lack of energy irrespective of sleep quantity or hard work (Ruggiero, Citation2003). Of the 142 respondents with self-reported chronic fatigue, 20% (n = 28) reported short-staffed units and heavy patient load as a perceived cause of fatigue (Ruggiero, Citation2003).

This theme identified that CCNs regularly self-reported the presence of poor physical health and chronic conditions. The casual association remains unclear, but it was reported to be influenced by the physical work environment.

Theme 2: a CCNs’ psychological well-being

The second theme maps how the critical care nurse’s psychological well-being was influenced by the work environment. Psychological symptoms reported included psychological distress; occupational stress; depression; and anxiety (Ruggiero, Citation2003). This review identified several factors that contributed to CCNs’ perceptions of psychological distress including shift work; high-pressure fast-paced setting; and the emotional burden of caring for high-acuity patients (Imes & Chasens, Citation2019; Marti-Ejarque et al., Citation2021).

The high-pressure and fast-paced nature of a critical care environment impacted nurses’ psychological well-being which manifested as occupational stress (Eldin et al., Citation2021; Marti-Ejarque et al., Citation2021). CCN self-reported being under pressure to complete tasks leads to occupational stress (Eldin et al., Citation2021). Two-thirds (n = 54) of CCN suffered from stress and experienced higher levels of stress compared with outpatient department nurses (Eldin et al., Citation2021). Similarly, operating room nurses (19.1%, n = 18) had higher self-reported levels of occupational stress than general ward nurses (14%, n = 15) (Marti-Ejarque et al., Citation2021).

Psychological distress in CCN can also be caused by the emotional burden of caring for the critically ill who often have poor clinical outcomes (Arrogante & Aparicio-Zaldivar, Citation2017; Eldin et al., Citation2021). Arrogante and Aparicio-Zaldivar (Citation2017) in Spain conducted a single-centre study with critical care registered nurses (n = 30), nursing assistants (n = 14), and physicians (n = 8). The survey included the validated Maslach Burnout and Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale tools. The Maslach Burnout Scale identified emotional exhaustion and depersonalisation (between 17 and 26; total sample n = 52), and personal accomplishment levels were low (>29), indicating moderate to high-level burnout in critical care clinicians. Importantly, the results of the mediational model analyses showed that resilience mediated the relationships between three burnout dimensions and mental health (−0.51 and 0.58). However, the authors’ analysis of the Maslach Burnout Scale did not conform to the recommended guidelines and therefore interpretation of the authors’ findings is limited.

Shift work was a common contributing environmental factor impacting nurses’ psychological health and well-being (Eldin et al., Citation2021; Imes & Chasens, Citation2019; Ruggiero, Citation2003). In the United States of America, Imes and Chasens (Citation2019) conducted a single-centre study that explored differences in self-reported wellness and health with rotating shift work for intensive care nurses (n = 23). The survey was conducted twice: one after a shift pattern of consecutive day shifts and one after consecutive night shifts. While the sample size was small, 30.4% (n = 7) of intensive care nurses were found to have emotional or psychological conditions. Shift work was correlated with higher emotional distress (r = 0.497, p < 0.5) and lower memory and concentration scores (r = .602, p < 0.01) (Imes & Chasens, Citation2019). Similarly, Rahman et al. (Citation2016) identified an association between shift work and tiredness; self-rated health (p < 0.011); and stress (p < 0.001) in CCNs. Moreover, there was a correlation between occupational stress and the ability to recover between shifts in CCNs (p < 0.001) (Rahman et al., Citation2016). The authors suggest that the demand of shift work expectations can influence psychological health and well-being.

Eldin et al. (Citation2021) reported that 32.5% (n = 26) of intensive care and operating room nurses had severe psychological distress compared to only 5% (n = 4) of the general nurse population. The authors reported that intensive care nurses had a higher prevalence of psychological conditions (p < 0.0008) compared to outpatient department nurses. Furthermore, 35% (n = 28) of intensive care and operating room nurses scored higher when assessed for psychological distress compared to 25% (n = 20) of the general nurse population. Whilst dated, Ruggiero (Citation2003) sought to measure depression and anxiety within critical nurses (n = 142) using the validated Beck Depression Inventory-II and Beck Anxiety Inventory. The authors reported that 23% (n = 32) of CCNs met criteria for mild, moderate, or severe depression and 32% (n = 45) of nurses met criteria for mild or moderate anxiety.

This theme has identified that a critical care setting can influence nurses’ psychological health and well-being. The high-pressure, fast-paced critical care environment and role demands led to psychological distress, occupational stress, depression, and anxiety for many CCNs.

Theme 3: the capacity to undertake the nursing role in critical care

The final theme maps the nurses’ capacity to undertake critical care activities and tasks whilst experiencing an acute or chronic condition. The capacity to undertake critical care nursing activities requires physical capability such as manual handling tasks, being emotionally present for patients, and demonstrate effective cognitive ability to react and make critical decisions (Chen et al., Citation2019; Rostamabadi et al., Citation2017).

Rostamabadi et al. (Citation2017) in Iran conducted a multi-centre survey study across eight intensive care units (n = 214 nurses) to explore factors associated with a nurse’s capacity to work. To measure work capacity, the validated Work Ability Index (WAI) and National Aeronautics and Space Administration task-load tools were selected. The WAI was used to measure nurses’ work capacity and health. The tool explores different aspects of workability including current workability; workability in relation to role demands; the number of current health conditions; estimated work impairment due to health conditions; sick leave; own prognosis of workability 2 years from now; and psychological resources. The cumulative index of work ability ranges from 7 to 49 points. It is divided into the categories: poor (7–27 points), moderate (28–36 points), good (37–43 points), and excellent work ability (44–49 points). Results reported that 27.57% (n = 59) of respondents had a chronic condition diagnosed by a physician. CCNs reporting a chronic condition were associated with a poor mean WAI score (between 7 and 35). Nurses reporting respiratory conditions (100%, n = 7) had the most reduced working capacity (30.85). Followed by those reporting genitourinary conditions (87.5%, n = 7, score 31.87); skin conditions (60%, n = 9, score 31.87); digestive conditions (52.94, n = 9, score 31.87); and musculoskeletal conditions (67.6%, n = 19, score 33.46) (Rostamabadi et al., Citation2017).

The physical capacity to undertake nursing work including manual tasks such as patient mobilisation and using heavy equipment was influenced by the CCNs’ health. One study found a significant association (p = 0.005, 95% CI = 0.01, 0.07) between work capacity and role performance such as quality and efficiency of nursing practice. For example, critical care areas nurses with chronic physical fatigue (p < 0.001) reported reduced work activity (p = 0.007) and motivation (P < 0.001) when performing the nursing role. However, no significant associations were found with physical or temporal demand, work effort, and overall workload with poor work capacity (Rostamabadi et al., Citation2017). Similarly, Rahman et al. (Citation2016) found CCNs’ self-rated health was significantly associated with perceived working capacity (p = 0.001). Marti-Ejarque et al. (Citation2021) reported that one in three reasons for absenteeism amongst operating room nurses were linked to musculoskeletal conditions. Musculoskeletal pain was also identified to impact absenteeism rates and was the reason for 10.9% (n = 18) of operating room nurses requesting relocation to another specialty (Marti-Ejarque et al., Citation2021).

The environmental context of a nurse’s task and role performance was examined in two studies (Chen et al., Citation2019; Rostamabadi et al., Citation2017). Task performance accounts for the ability to perform the nursing role (Chen et al., Citation2019). The ability to effectively perform tasks in critical care was multifactorial and was impacted by physical, psychological, and environmental factors (p < 0.01). Moreover, environmental exposures to biological, chemical, and toxic substances may contribute to chronic conditions in nurses, such as occupational asthma, allergies, liver diseases, and skin dermatitis (Rostamabadi et al., Citation2017). Protection from environmental biological hazards (b = 0.17, P < .002) and the safety climate of an organisation (b = 0.24, P < .001) were both significantly associated with the capacity to perform tasks with emergency nurses (Chen et al., Citation2019). These findings suggest that the influence on working capacity is multifaceted and includes nurses’ health and the work environment.

CCNs who reported a psychological disorder (62.50%, n = 5) rated a poor work capacity (score 31.37) (Rostamabadi et al., Citation2017). Nurses reporting a reduced work capacity may experience cognitive, psychomotor, and behavioural impairment leading to a slower reaction time, a lapse in critical judgement and reduced motivation (Chen et al., Citation2019; Rostamabadi et al., Citation2017). High-level functioning and critical thinking that is required by CCNs can contribute towards occupational pressure. For example, the complexity of tasks, confronting unpredictable events, decision-making under time pressure, and dealing with patients’ and relatives’ emotional load (Chen et al., Citation2019). Excessive occupational pressure may lead to negative associations increasing workplace frustration (p < 0.001) and temporary workload demand (p < 0.0001) and capacity to perform the emotional dimensions of the nursing role (Rostamabadi et al., Citation2017).

This review identified organisational culture within a critical care environment affects the ability to perform the critical care nursing role. Chen et al. (Citation2019) found that the perception of how much safety is valued within an organisation was significantly associated (p < 0.001) with a nurse’s ability to perform tasks. Organisational commitment and job satisfaction variables were positively associated with critical care nurse performance. Another study reported: burnout (p < 0.001), commitment to the workplace (p < 0.010), and trust in management (p < 0.021) influenced a nurse’s work capacity and experience of fatigue symptoms (Rahman et al., Citation2016). In contrast, organisational commitment, job satisfaction, personal, and professional variables were positively associated with role performance (Chen et al., Citation2019). Positive organisational culture was found to include occupational behaviours associated with nursing tasks; establishment and improvement of safety climates; supportive working environment strategies such as reduced workload and social support; and the implementation of physical and psychological health programs for nurses (Chen et al., Citation2019).

This theme has identified that the presence of an acute or chronic condition can influence a nurse’s ability to manage within the critical care environment. A number of factors were highlighted to influence a nurse’s ability to manage their role such as physical capacity, psychological health, and organisational culture. The review has highlighted that the critical care environment can influence nurses’ work capacity especially in the presence of a chronic condition.

Discussion

The key findings in this scoping review highlighted that the combination of ageing and the critical care work environment has the potential to make a substantive impact on nurses’ physical and psychological health, in turn influencing working capacity. While the level of evidence is weak, all studies reported the presence of chronic conditions across the critical care nursing workforce. It remains unclear if different critical care environments may need different strategies to support nurses’ health and wellbeing as they could elicit different rates of occupational stress, poor health choices, or adaptability to fulfil the critical care role.

This review highlighted the demanding critical care nursing role have an influence on a nurses’ physical health. The physical aspect of the critical care nurse's role includes standing for prolonged periods, physically supporting, mobilising, and turning complex and critically ill patients regularly (Levi et al., Citation2021). While the evidence was weak, intensive care and operating theatre nurses were more likely to experience biomechanical and ergonomic risks during work activities and had a higher prevalence of musculoskeletal conditions compared to general nurses (Marti-Ejarque et al., Citation2021). These physical tasks require the nurse to perform challenging body movements such as bending and lifting, leading to injuries influenced workability (Chen et al., Citation2019; Eldin et al., Citation2021; Marti-Ejarque et al., Citation2021), absenteeism rates, and intent to leave the speciality in this review (Eldin et al., Citation2021; Marti-Ejarque et al., Citation2021).

Similarly, physical fatigue was identified to be associated with burnout, lower self-rated health, reduced work commitment and trust in management (Rahman et al., Citation2016). Physical fatigue symptoms were identified to impact nurses’ physical health and work capacity in critical care. CCNs who reported sleep-related impairment strongly correlated with higher levels of fatigue, emotional distress and anger (Ruggiero, Citation2003). Fatigue poses a potential risk to patient safety by increasing medical errors and decreasing vigilance in clinician decision-making (Chegini et al., Citation2019; Montgomery, Citation2007). Further research is critical to explore contributing critical care environmental factors that might influence nursing fatigue.

In this review, nurses’ psychological health was influenced by the critical care environment. Occupational stress was prevalent in CCNs across all studies, which could manifest as depression and anxiety (Imes & Chasens, Citation2019; Ruggiero, Citation2003). Critical care environments encompass a variety of stressful events including life-threatening conditions, unexpected death, and patients in severe pain or dying, which can increase the emotional burden and occupational stress (Eldin et al., Citation2021; Marti-Ejarque et al., Citation2021; Vogt et al., Citation2023). Repeated exposure to such events could influence a nurses’ intention to leave the profession, work capacity and psychological health (Ahwal & Arora, Citation2015).

CCNs must utilise critical thinking skills under pressure and manage patients’ and relatives’ emotional load across a range of shift rotations and rostering schedules, despite experiencing high workload and overtiredness (Eldin et al., Citation2021; Imes & Chasens, Citation2019; Rostamabadi et al., Citation2017; Ruggiero, Citation2003). Clinical decision-making is an integral aspect of these processes, and for CCNs, they are required to make decisions on a minute-by-minute basis (Harrison & Nixon, Citation2002). The ability to fulfil the requirements of the role is dependent on clinical decision capacity and the capability of the critical care nurse. This review reported poor psychological health could impair concentration, leading to a slower reaction time, lapses in clinical judgement, decision-making, and focused thinking, reducing nurses’ work capacity (Imes & Chasens, Citation2019).

The review highlighted that there were specific challenges experienced by nurses working within critical care environments that related to their physical and psychological health and wellbeing. CCNs self-reported a high percentage of chronic conditions when compared to other specialties in this review (Eldin et al., Citation2021; Marti-Ejarque et al., Citation2021). Given the ageing workforce, the presence of chronic conditions in CCNs is likely to increase, which may pose recruitment and retention issues for healthcare organisations (AIHW, Citation2020; Elshaer et al., Citation2018; Henriksen et al., Citation2021). Higher level of evidence is needed to better understand how roles and activities, and organisational and environmental factors impact on the retention of CCNs (Phillips & Miltner, Citation2015). Additionally, more rigorous research is needed to enhance support structures, safe climate, and define a supportive work environment to enhance the recruitment and retention of CCNs.

Limitations

The scoping review has several limitations. The studies provided low-quality evidence, and sample sizes were often small making it difficult to generalise these findings. While validated instruments were used in five studies, other researchers used self-developed tools, which limited study validity and rigor. Although chronic conditions were reported to be high, the prevalence of pre-existing conditions was unknown and the causation for chronic conditions could not be determined. The majority of studies were conducted in single sites, but some findings were strengthened by the inclusion of multiple units within the site. Given some of the included articles are dated, for example, Ruggiero (Citation2003), the generalisability and transfer of these new findings may be limited in relation to patient-to-staff ratio, manual handling policies, and workforce burden in contemporary healthcare today.

The studies that met the search criteria were mostly from European countries and the USA, limiting generalisability in Australia. Reliability and transferability of findings are limited, given all studies used self-reporting survey methods, which can lead to responder bias. This can occur when respondents complete rating scales in ways that do not accurately reflect their true responses, especially amongst responses to Likert scales that ask the respondent to agree or disagree with various statements (Smith, Citation2014). This review notes the importance of using a validated instrument to adhere to the instrument’s guidelines in data analysis.

Conclusion

This scoping review synthesised the literature that explored the influence of a critical care environment on nurses’ acute or chronic physical and psychological health, well-being, and work capacity. This review found that the critical care work environment negatively influenced the health and well-being of nurses and their work capacity. Work capacity was reported to be impacted by physical health, chronic conditions, psychological health, and well-being. The strengths of this review include providing evidence of the impact of acute or chronic conditions on nursing practice, absenteeism, and retention in critical care specialities. Further research is needed to explore ways to better support CCNs’ health and wellbeing. This is important for the ageing nurse population to mitigate the influence of a chronic condition and optimise the recruitment and retention of this valuable nursing workforce.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- ACI. (2021). Adult intensive care workforce report in COVID-19 pandemic.

- Ahwal, S., & Arora, S. (2015). Workplace stress for nurses in emergency department. IJETN, 1(2), 17–21.

- AIHW. (2020). Health workforce. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-health/health-workforce

- Arrogante, O., & Aparicio-Zaldivar, E. (2017). Burnout and health among critical care professionals: The mediational role of resilience. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing, 42, 110–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2017.04.010

- Brennan, E. J. (2017). Towards resilience and wellbeing in nurses. British Journal of Nursing, 26(1), 43–47. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2017.26.1.43

- Buerhaus, P. I. (2005). Six-part series on the state of the RN workforce in the United States. Nursing Economics, 23(2), 58–60, 55.

- Buerhaus, P. I., Staiger, D. O., & Auerbach, D. I. (2000). Implications of an aging registered nurse workforce. Jama, 283(22), 2948–2954. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.283.22.2948

- Chegini, Z., Asghari Jafarabadi, M., & Kakemam, E. (2019). Occupational stress, quality of working life and turnover intention amongst nurses. Nursing in Critical Care, 24(5), 283–289. https://doi.org/10.1111/nicc.12419

- Chen, X., Arber, A., Gao, J., Zhang, L., Ji, M., Wang, D., Wu, J., & Du, J. (2021). The mental health status among nurses from low-risk areas under normalized COVID-19 pandemic prevention and control in China: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 30(4), 975–987. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12852

- Chen, F. L., Chen, K. C., Chiou, S. Y., Chen, P. Y., Du, M. L., & Tung, T. H. (2019). The longitudinal study for the work-related factors to job performance among nurses in emergency department. Medicine, 98(12), e14950. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000014950

- Daouda, O. S., Hocine, M. N., & Temime, L. (2021). Determinants of healthcare worker turnover in intensive care units: A micro-macro multilevel analysis. PLoS ONE, 16(5), e0251779. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0251779

- Eldin, A. S., Sabry, D., Abdelgwad, M., & Ramadan, M. A. (2021). Some health effects of work-related stress among nurses working in critical care units. Toxicology and Industrial Health, 37(3), 142–151. https://doi.org/10.1177/0748233720977413

- Elshaer, N. S. M., Moustafa, M. S. A., Aiad, M. W., & Ramadan, M. I. E. (2018). Job stress and burnout syndrome among critical care healthcare workers. Alexandria Journal of Medicine, 54(3), 273–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajme.2017.06.004

- Haji Matarsat, H. M., Rahman, H. A., & Abdul-Mumin, K. (2021). Work-family conflict, health status and job satisfaction among nurses. British Journal of Nursing, 30(1), 54–58.

- Harrison, L., & Nixon, G. (2002). Nursing activity in general intensive care. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 11(2), 158–167. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2702.2002.00584.x

- Health Service Executive. (2017). Our people/our workforce - Public health service. http://www.hse.ie/eng/staff/Resources/OurWorkforce/Public-Health-Service-Workforce-Profile-at-December-2016.pdf

- Henriksen, K. F., Hansen, B. S., Wøien, H., & Tønnessen, S. (2021). The core qualities and competencies of the intensive and critical care nurse, a meta-ethnography. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 77(12), 4693–4710. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.15044

- Imes, C. C., & Chasens, E. R. (2019). Rotating shifts negatively impacts health and wellness among intensive care nurses. Workplace Health & Safety, 67(5), 241–249. https://doi.org/10.1177/2165079918820866

- JBI. (2014). Supporting document for the Joanna Briggs Institute levels of evidence and grades of recommendation. https://jbi.global/sites/default/files/2019-05/JBI%20Levels%20of%20Evidence%20Supporting%20Documents-v2.pdf

- Levi, P., Patrician, P. A., Vance, D. E., Montgomery, A. P., & Moss, J. (2021). Post-traumatic stress disorder in intensive care unit nurses: A concept analysis. Workplace Health & Safety, 69(5), 224–234. https://doi.org/10.1177/2165079920971999

- Lim, J., Bogossian, F., & Ahern, K. (2010). Stress and coping in Australian nurses: A systematic review. International Nursing Review, 57(1), 22–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1466-7657.2009.00765.x

- Lukan, J., Bolliger, L., Pauwels, N. S., Luštrek, M., Bacquer, D. D., & Clays, E. (2022). Work environment risk factors causing day-to-day stress in occupational settings: A systematic review. BMC Public Health, 22(1), 240. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-12354-8

- Marti-Ejarque, M. D. M., Guiu Lazaro, G., Juncal, R. C., Perez Paredes, S., & Diez-Garcia, C. (2021). Occupational diseases and perceived health in operating room nurses: A multicenter cross-sectional observational study. Inquiry, 58, 469580211060774. https://doi.org/10.1177/00469580211060774

- Martin, E., & McFerran, T. (2008). Symptom. Oxford University Press.

- Montgomery, V. L. (2007). Effect of fatigue, workload, and environment on patient safety in the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine, 8(2 Suppl.), S11–S16. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.PCC.0000257735.49562.8F

- Opie, T., Lenthall, S., Wakerman, J., Dollard, M., MacLeod, M., Knight, S., Rickard, G., & Dunn, S. (2011). Occupational stress in the Australian nursing workforce: A comparison between hospital-based nurses and nurses working in very remote communities. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing, 28(4), 36–43.

- Peplonska, B., Bukowska, A., & Sobala, W. (2014). Rotating night shift work and physical activity of nurses and midwives in the cross-sectional study in Lodz, Poland. Chronobiology International, 31(10), 1152–1159. https://doi.org/10.3109/07420528.2014.957296

- Perry, L., Gallagher, R., & Duffield, C. (2015). The health and health behaviours of Australian metropolitan nurses: An exploratory study. BMC Nursing, 14(1), 45. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-015-0091-9

- Peters, M. D. J., Marnie, C., Tricco, A. C., Pollock, D., Munn, Z., Alexander, L., McInerney, P., Godfrey, C. M., & Khalil, H. (2020). Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Synthesis, 18(10), 2119–2126. https://doi.org/10.11124/JBIES-20-00167

- Phillips, J. A., & Miltner, R. (2015). Work hazards for an aging nursing workforce. Journal of Nursing Management, 23(6), 803–812. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.12217

- Quick, J. C., & Henderson, D. F. (2016). Occupational stress: Preventing suffering, enhancing wellbeing. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 13(5). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13050459

- Rahman, H. A., Abdul-Mumin, K., & Naing, L. (2016). A study into psychosocial factors as predictors of work-related fatigue. British Journal of Nursing, 25(13), 757–763. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2016.25.13.757

- RCN. (2016). Unheeded warnings: Health care in crisis.

- Rostamabadi, A., Zamanian, Z., & Sedaghat, Z. (2017). Factors associated with work ability index (WAI) among intensive care units’ (ICUs’) nurses. Journal of Occupational Health, 59(2), 147–155. https://doi.org/10.1539/joh.16-0060-OA

- Ruggiero, J. S. (2003). Correlates of fatigue in critical care nurses. Research in Nursing & Health, 26(6), 434–444. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.10106

- Ryan, C., Bergin, M., White, M., & Wells, J. S. G. (2019). Ageing in the nursing workforce – A global challenge in an Irish context. International Nursing Review, 66(2), 157–164. https://doi.org/10.1111/inr.12482

- Sarafis, P., Rousaki, E., Tsounis, A., Malliarou, M., Lahana, L., Bamidis, P., Niakas, D., & Papastavrou, E. (2016). The impact of occupational stress on nurses’ caring behaviors and their health related quality of life. BMC Nursing, 15(1), 56. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-016-0178-y

- Smith, P. B. (2014). Response bias(es). In A. C. Michalos (Ed.), Encyclopedia of quality of life and well-being research (pp. 5539–5540). Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-0753-5_2503

- Steege, L. M., & Pinekenstein, B. (2016). Addressing occupational fatigue in nurses: A risk management model for nurse executives. JONA: The Journal of Nursing Administration, 46(4), 193–200. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNA.0000000000000325

- Veritas Health Innovation. (2023). Covidence systematic review software. https://www.covidence.org

- Vogt, K. S., Simms-Ellis, R., Grange, A., Griffiths, M. E., Coleman, R., Harrison, R., Shearman, N., Horsfield, C., Budworth, L., Marran, J., & Johnson, J. (2023). Critical care nursing workforce in crisis: A discussion paper examining contributing factors, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and potential solutions. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 32(19-20), 7125–7134. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.16642

- WHO. (2014). Global status report on noncommunicable diseases. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241564854