Abstract

During the 2015 sudden rise in migration movements in Europe, approximately 2.4 million refugees arrived in Europe and 1.2 million asylum applications were received in the European Union countries. We were interested in finding out whether these rapid changes and the polarised attitudes represented in the media affected young people’s attitudes towards people with different cultural backgrounds. This study, therefore, examined young people’s global understanding in four European countries: Czechia, Finland, Germany and the Netherlands. The aim was to identify the level of world-mindedness of young people and compare the results with an earlier study (conducted in 2010) with the same research design. The research was targeted at a group of upper-secondary students in these countries. In total, 962 students participated in the study in 2017. Although the context in the observed countries varied, the findings revealed a stable state, or rather a slightly positive change of world-mindedness, to 2010 in all the countries. The results stress the need to remain sensitive to students’ opinions and attitudes towards other people and cultures in geography lessons in general and especially when teaching and learning about current societal issues, inequality, exclusion and solidarity.

Introduction

Globalisation, which has increased our encounters with people coming from different cultural backgrounds, can improve our understanding of diversity and broaden our worldviews. Geography education can have a key role in developing and assessing students’ geographical worldviews (their origins, past applications and suitability to actual issues), and it also has an excellent opportunity to support young people’s growth as culturally and socially sensitive individuals who are open to encounters with other people and cultures (e.g. Werlen, Citation2018). Although no single scientific field can claim global understanding as its domain (Solem & Zhou, 2018), many of the topics of global citizenship education (such as human rights, global governance, sustainability, identity, cultural diversity, etc.) are traditionally part of the geography curricula at various levels of education (de Miguel González, Bednarz, & Demirci, 2018; Al-Maamari, Citation2020). Geography education should then encourage students to improve their respect for foreign regions’ contexts, their willingness to solve regional problems, and their initiative to engage in regional cooperation (Lee, Citation2018). Therefore, geography education is vital for the education of global-minded citizens (Scoffham, Citation2019; de Miguel González, 2021). However, people’s own experiences and education, other people’s attitudes and media representations are just some of the many elements that shape our understanding of the world (Reynolds & Vinterek, Citation2016). This is the starting point for this research: our interest in young people’s global awareness.

This study follows the work that was conducted as cross-national research on geography students’ world-mindedness and their ideas of the global perspective in geography education in Finland, Germany and the Netherlands (Béneker, Tani, Uphues, & van der Vaart, Citation2013). The results of the survey were surprisingly similar in all three participating countries: most of the students were open to the world, showed a sense of curiosity and were interested in cultural experiences and opportunities to meet other people and see other places. At the same time, however, many of the young participants prioritised their personal and national interests over wider global aspects, such as sharing welfare and giving up specific rights (Béneker et al., Citation2013). Subsequently, the research was carried out in a selection of countries in Central and Eastern Europe (Czechia, Hungary and Serbia) in 2011 (Hanus, Řezníčková, Marada, & Benéker, Citation2017; Pavelková, Hanus, & Hasman, Citation2020). The findings showed that students in these countries, especially in Czechia and Hungary, were more nation-minded, while Serbian students manifested a higher level of world-mindedness with scores close to the Western countries.

After conducting these studies, the situation in Europe changed considerably when the European Union (EU) faced an increase in the number of migrants. Our assumption was that sudden changes and the public discussion on the migration in many countries could have affected people’s attitudes towards refugees and, more generally, towards other people and cultures, and that could have an effect also on their world-mindedness (according to the Group Threat Theory and Contact Theory; see, e.g. Berg, Citation2009; García-Faroldi, Citation2017). We were thus interested in finding out whether some changes of young people’s attitudes and ideas of others could be traced after the migration rise of 2015. Therefore, we decided to replicate the earlier study after these sudden changes with a focus on upper-secondary school students in Czechia, Finland, Germany and the Netherlands.

Our aim is to identify the level of world-mindedness of young people in four countries and to evaluate the differences between the 2010 and 2017 results.Footnote1 First, we will make a brief overview of the sudden changes in migration in Europe and in participating countries. Subsequently, the context of global education will be described. After that, the gathered data and the used methods will be explained. We will compare the structure of world-mindedness on the level of countries, as well as on the level of individual participants. Based on the analysed data, we will discuss the potential of geography education in enhancing students’ cultural and social sensitivity – their world-mindedness.

The migration rise in Europe: Background for this study

Rapid changes in migration happened in 2015 in Europe: approximately 2.4 million refugees arrived in Europe and 1.2 million asylum applications were received in EU countries. The highest number of first-time asylum applicants in the EU in 2015 was registered in Germany (35% of all applicants), followed by Hungary (14%) and Sweden (12%) (Eurostat, Citation2016). Compared with the previous year, the number of first-time asylum applicants in 2015 increased the most in Finland (+822%) (see ).

Table 1. First-time asylum applicants in Czechia, Finland, Germany and the Netherlands in 2014 and 2015 (Eurostat, 2016).

Since the 1990s, Czechia has gradually transformed from a country of prevailing emigration to a net immigration country (Drbohlav, Citation2011). Nevertheless, the number of immigrants living in Czechia and their percentage of total population are still fairly modest in the European context (Czech Statistical Office, Citation2019). A tendency towards immigration growth, with only a slowdown caused by the economic crisis in 2007/2008, can be observed. At the end of 2016, there were 496,413 immigrants in Czechia, which totals 4.5% of the population. Czechia was influenced by the increased migration in 2015/2016 much less than other countries. Yet, an atmosphere of fear of migrants (who threaten Czech economy, traditional catholic-based culture and security in general) was created by the media and many politicians (Jelínková, Citation2019). The topic of immigration was considered one of the top issues. The manner of such debates was often manipulative (Pavelková et al., Citation2020). Compared to the rest countries taking part, Czech economy is weaker, with a purchase parity of approx. 70% of average of the rest three countries in both years (see ).

Finland, with its present population of 5.5 million people, has been (and still is) a relatively homogeneous country by its ethnic background. More than 87% of the population speak Finnish as their native language. Historic minorities are Finland-Swedes, Sami and Roma people (Finland in Figures, Citation2020). The share of foreign citizens living in Finland is 4.8%, and the share of persons with a foreign background is 7.7% (Key Figures on Population by Region, 1990–2019, 2020). The number of asylum seekers had always been low compared with other Nordic countries, and therefore, it is easy to understand how the increase in 2015 was something that had never been experienced before. Even when the absolute numbers of refugees were small, the rapid change made asylum policy a key political issue in Finland in 2015 (Wahlbeck, Citation2019).

Germany, with its present population of 83.2 million people (Statistisches Bundesamt, Citation2020), has never really been a homogenous country regarding the ethnic background of population. What has changed over the years is the regions where migrants are coming from. In addition, the extent of migration has varied a lot over time (Berlinghoff, Citation2018). The share of foreign citizens living in Germany is 12.4%, and the share of persons with a foreign background is 26.0%. Most of them have their background either in other European countries (64.9%) or in the Near and Middle East (15.2%) (Statistisches Bundesamt, Citation2020). The rapid rise of registered arriving refugees, overall 890,000 in 2015 and first-time asylum applicants, almost 442,000 in 2015 and 723,000 in 2016 (Eurostat, Citation2016) compared to 34,000 per year between 2003 and 2013 and 173,000 in 2014 (Herbert & Schönhagen, Citation2020), led to an administrative and infrastructural crisis. In politics and society in general, this caused debates about migration, asylum policy and its consequences. Several authors address a continuing polarisation of society regarding these topics (e.g. Herbert & Schönhagen, Citation2020).

In the Netherlands, 24.6% of the population has a migrant background, 10.6% from Western and 14.0% from non-Western origins (Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek, Citation2021). Of these migrants, 46.3% were born in the Netherlands and belong to the group of second-generation migrants. The largest group is from Turkey (9.8%), and other important countries of origin are Morocco, Surinam, Indonesia, Germany and Poland. From 2007, there has been a positive migration balance, with the majority of migrants coming from European countries, followed by migration from Asia. Since 2015, public and policy debates about migration flared up when almost 45,000 asylum seekers arrived in the Netherlands because of the war in Syria. This number has dropped again to about 20,000 per year. Despite this lower number, there is an ongoing polarised and emotional debate about the pros and cons of immigration (De Beer & De Valk, Citation2019).

Research on Europeans’ opinions about immigration in the first two decades of this century show a relatively stable public attitude (e.g. Hatton, Citation2017). However, Lönnqvist, Ilmarinen, and Sortheix (Citation2020) showed how polarisation of attitudes among the political elite was strengthened. Stockemer, Niemann, Unger, and Speyer (Citation2020) noted how the media had not made a clear distinction between refugees and other immigrants, and that caused some confusion on people’s ideas about who was migrating to Europe. The refugees of 2015 were often portrayed as dangerous outsiders by the press in many European countries (Lönnqvist et al., Citation2020). This conflation could have influenced Europeans’ perceptions of migrating people and widened the gap between the ideas of “us” and “them”.

Context of global education

Merryfield, Tin-Yau Lo, Cho Po, and Kasai (Citation2008) distinguish several aspects of global education that can be grouped into three dimensions: Knowledge of the world and its interconnectedness, Inquiry into global issues, and Perspective consciousness, open-mindedness, intercultural experience/competence (i.e. global values development) (Béneker et al., Citation2013). The results of the educational part of the questionnaire were used for the general explanation of the education context of the study (see below).

In Czech education for global understanding, the greatest emphasis is laid on the knowledge of the world and its interconnectedness, particularly on the issues of (under)development of regions and countries. Contrary, the inquiry into global issues and development of values to open-mindedness (e.g. learning to avoid stereotyping of countries or cultures) is rare. Finnish education equally employs all three dimensions of global education, specifically builds students’ knowledge of the world, employs inquiry-based learning strategies and frequently develops open-mindedness of students by exploring other cultures, learning about the dangers of stereotype images and discussing alternative points of view of people from different cultures/nations. Young people in Germany (similarly to their Czech and Dutch peers) commonly develop their knowledge of the world (especially the issues of globalization and global warming), but they are less frequently taught according to inquiry-based learning (IBL) principles. The least attention (from the dimensions of global education) is devoted to developing open-minded values (e.g. discussions on the different national perspectives on the world). Dutch global education places the greatest emphasis on the knowledge of the world (particularly knowledge about other parts of the world, globalization and climate change) from all countries taking part. The IBL strategies and the global values development strategies are employed less frequently. Although young people commonly explore other cultures and are required to work individually in their geography lessons, their education often lacks opportunities to discuss and present their work and give their personal opinions about international issues.

In comparison, in Finland all three dimensions of global education are commonly included in the lessons, while in the other three countries obtaining knowledge of the world dominates the lessons in global education.

Data and method

World-mindedness as a concept

While the concept of world-mindedness is relatively seldom used in recent studies of geography education (however, see Lee, Citation2018), its close connection to the contemporary discussions is easy to see. For their world-mindedness survey, Béneker et al. (Citation2013) selected 20 statements related to world-mindedness: 10 of them from Sampson and Smith (Citation1957) world-mindedness scale and 10 from Hett’s (Citation1993) global-mindedness scale. Sampson and Smith (Citation1957) concept of world-mindedness meant “purely a value orientation, or frame of reference, apart from knowledge about, or interest in, international relations”. They (1957) identify as highly worldminded the individual who favours a worldview of the problems of humanity, whose primary reference group is mankind [sic], rather than Americans, English, Chinese, etc.” Hett (Citation1993) defined global-mindedness as “a worldview in which one sees oneself connected to the world community and feels a sense of responsibility for its members”. Hett described five dimensions that she regarded relevant for a global-minded attitude: responsibility, cultural pluralism, efficacy, global centrism and interconnectedness. All the statements represented by Sampson and Smith (Citation1957) and Hett (Citation1993) were statistically validated in their own studies as well as in some later studies, and therefore, Béneker et al. (Citation2013) did not find any further tests needed. In our study, we followed the research design described by Béneker et al. (Citation2013).

Description of the questionnaire

Students’ world-mindedness was studied by presenting them 20 statements in the questionnaire (see ). A six-point Likert response scale (from strongly disagree to strongly agree) was used, and the reverse statements were recalculated before being used in the world-mindedness score.

Table A2. Statements derived from the world-mindedness scale (Sampson & Smith, Citation1957) and the global-mindedness scale (Hett, Citation1993). Reverse statements are marked with (r).

The statements that were used in the survey in the 2010 research and in our own study are connected to the following four aspects:

Patriotism (global–national) and human rights (justice, global centrism) – S1, S5, S9, S13, S17

Economy and migration (equal access, efficiency) – S2, S6, S10, S14, S18

Education and learning (responsibility, sustainability) – S3, S7, S11, S15, S19

Culture and attitude towards others (respect, diversity) – S4, S8, S12, S16, S20.

The subsequent part of the questionnaire consists of 15 statements on global education (see Béneker et al., Citation2013) to better understand the educational context of the study.

Research design

The questionnaire was first written in English and then translated into Czech, Dutch, Finnish and German. The research was targeted at a group of upper-secondary students. Our intention was to keep the research sample maximally homogenous between both years. This was most successfully achieved in Finland where 183 students out of the 199 participants were recruited from the same four schools that participated in the 2010 survey and partly in the Netherlands (half of the schools from 2010 participated in 2017). In Czechia and Germany, the 2010 schools had to be substituted to a greater extent in 2017/2018. However, this substitution was driven by the criteria for school selection (general secondary schools without the specific specialization – non-elitist schools attended by students of a mixed socioeconomic status reflecting the total socioeconomic structure of the population in the region; variability in the size of cities where schools are located (from the regional centres to smaller cities) set in 2010 to increase the comparability of the results.

A total number of 1,986 young people from four countries responded to the questionnaire: 1,024 in 2010 and 962 in 2017 (see Appendix, ). The age of participants varied from 14 to 19 years with a median age of 16.

Table A1. Structure of the research sample.

Methods

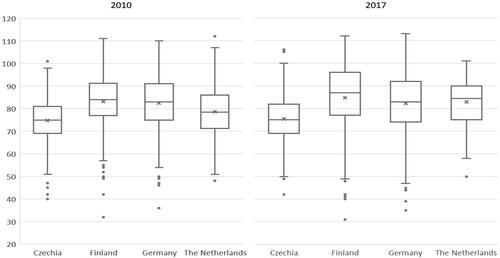

Data were gathered with a printed questionnaire in Czechia, Germany and the Netherlands. In Finland, a digital version of the questionnaire was used. Questionnaires were administered via geography teachers equipped with all necessary instructions. For the purpose of the evaluation of the results, the total theoretical range of world-mindedness scores between 20 and 120 points has been split into five categories first (equally − 20 points of the scale per category). Secondly, considering the construction of the questionnaire and the framework of interpretation of the scores (two scores nation-minded, two open minded and one indecisive in the middle of the scale) we merged categories into three: nationalist (less than 59.9), mid-stream (60–80) and open-minded (more than 80.1). Additionally, these categories were further split into 19 types of participants (Appendix 2; see also ). Nine of these types fall into the category of “mid-stream”, while “open-minded” and “nation-minded” categories are represented by five types each. These types represent possible combinations of scores in all world-mindedness aspects. Three types correspond to the “balanced structure”, which means that all aspect scores fall into the corresponding category. The rest of the types express an imbalance in the structure; for example, Type 2 falls under open-minders, even when the score in “patriotism” is lower and corresponds to the mid-stream or nation-minded category. Therefore, national interests are more manifested in the aspect of patriotism. Reversely, Type 16 is nation-minded in the overall score, but in “patriotism”, it shows more open-minded tendencies (scores corresponding to mid-stream or open-minded). It is obvious that some participants can fall under more than one type, especially in the mid-stream category. Nevertheless, such typology is useful for the evaluation of variability at the level of participants.

Table 2. Structure of participants according to the types of world-mindedness.

Results

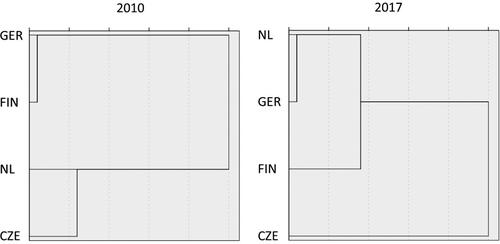

Based on the responses of all 1,986 participants, the overall level of world-mindedness of young people is on the threshold of the open-minded and mid-stream categories with a median value of 80 (). While Czechia falls into the mid-stream category, the other countries meet the criteria for the open-minded category, with the highest median score in Finland (86). While median scores stayed stable in Czechia and Germany, an increase of approximately five points was recorded in Finland (84 to 89) and the Netherlands (78.5 to 84). The Netherlands was the only country in the sample that changed category between 2010 and 2017.

Figure 1. World-mindedness score distribution in participating countries in 2010 (left) and 2017 (right).

Considerable variability in the results was observed both at the level of countries and between individual participants. Although the participants used almost the full range of the scale (maximum value was 113 and the minimum 31), the most frequent score (82, 3.3% of the sample) falls under open-minded category (see ).

The three statements with the highest scores in the whole sample (for both years) fall under three different aspects (“patriotism and human rights”; “education and learning”; “culture and attitudes to others”), and their preferences were rather stable over time and across countries. The statements with the most open-minded scores in both years were:

S7 – It is important that we educate people to understand the impact that current policies might have on future generations. (Average score 5.13 out of a maximum of 6.0)

S9 – Any healthy individual, regardless of race or religion, should be allowed to live wherever he wants to in the world. (4.94)

S4 – People in our country can learn something of value from all different cultures. (4.88)

In contrast, the pool of the most nation-minded statements was more variable across countries. Although this list was stable over time. Three of them refer to “patriotism” and one to “economy and migration”. The statements with the most nation-minded scores in the whole sample were:

S1 – It would be better to be a citizen of the world than of any particular country. (3.12)

S14 – Our country should permit the immigration of foreign people even if it lowers our standard of living. (3.13)

S13 – Our country should not participate in any international organization which requires that we give up any of our national rights or freedom of action. (3.25)

S17 – If necessary, we ought to be willing to lower our standard of living to cooperate with other countries in getting an equal standard for every person in the world. (3.25)

Differences between countries

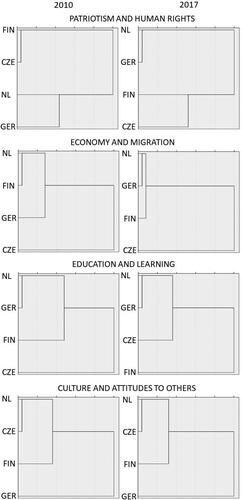

Differences between countries can be observed not only in the overall score of but also in its structure (). As mentioned in the methodology section, the score is saturated by the level of open-mindedness in its four aspects. According to the overall scores, participants are mostly open-minded in “culture and attitudes to others” and in “education and learning”, while national interests are more evident in “patriotism” and “economy and migration”. It means that, on average, young people are open to learning about foreign countries and to share the culture, but they are more vigilant when it comes to sharing the wealth or giving up some of the national rights.

The situation in the Netherlands follows the overall pattern in both years, although all the partial scores increased in 2017. Dutch young people were the most open-minded in “education and learning” and especially in “culture and attitudes to others”. The German participants were considered open-minded in both years, but there was a notable decrease (by 1.25) in “culture and attitudes to others”. The Finnish overall pattern did not change between 2010 and 2017. Finnish young people were the most open-minded in all world-mindedness aspects except “patriotism”, which was the only aspect that did not increase notably in 2017 and stayed the same as in 2010. The overall pattern of world-mindedness in Czechia stayed stable in both years. The lowest average score recorded in both years was in “economy and migration”. Based on this result, Czech participants seemed to be rather cautious when it came to sharing resources with migrants and people of another culture. Although Czechia is considered a developed country its purchase parity and the economy in general is lower when compared to the Western countries. Being aware of this situation, Czech students manifested more nation-minded attitudes in economy than the students from other countries in this aspect. It seems that the overall wealth of the population influences young people’s open-mindedness in sharing resources. However, further research is needed in this regard.

When analysing the differences in the level and the structure of world-mindedness across countries, different patterns occurred (). While in 2010 two distinct pairs of countries close to each other can be observed, a pattern 3 + 1 can be observed in 2017 – this underlines a different level of world-mindedness in Czechia that has stayed stable since 2010. The pattern change can be ascribed to the decrease of open-mindedness in “culture and attitude to others” in Germany, and, especially, to the overall increase of world-mindedness (and all its aspects) in the Netherlands. Germany and the Netherlands, therefore, moved closer to one another, leaving Czechia behind, and Finland alone as well, although this pair of countries is closer to Finland than to Czechia.

Focusing on the median scores for “patriotism”, a pattern of two pairs of countries close to each other and distant to the rest occurred: Finland and Czechia; and the Netherlands and Germany. This pattern showed no significant changes in the scores. Finland and Czechia identically placed the highest emphasis on the possibility of any healthy individual to live wherever they want and were aware that their national values were probably not the best. Nonetheless, they did not prefer being world citizens instead of citizens of their country, did not prefer participating in any organisation that required giving up their national rights and most of them did not want to lower their standard of living for the benefit of other nations. Although the Dutch and German respondents mostly preferred the right of all people to live wherever they want as well, their scores in the rest of the statements were more open-minded and balanced. Contrary, Czech and Finnish participants declared national tendencies in three of the five patriotism statements. Considering the national context, it could be anticipated that the more nationally homogenous the country is, the more national interests are manifested in patriotism.

World-mindedness of “economy and migration” fully reveals the distinctiveness of Czechia compared to the rest of the countries. This is manifested by the national tendencies in the issues dealing with sharing the national wealth with less fortunate people in the world and, especially, with the rejection of immigration because of fear of lowering living standards. On the other hand, Czech participants were open-minded when it came to the benefits of an interconnected world, economic international cooperation and employing migrants. However, their average scores (per participant and statement) in all statements in this aspect were lower than the rest of the countries that were open-minded in all of the statements (2017: Czechia 3.3, Finland 4.2, Germany 4.1, The Netherlands 4.0). These scores were rather stable over time. Nonetheless, a minor decrease in scores occurred in Czechia, which is in contrast to a minor increase in almost all of the statements in the rest of the countries (2010: Czechia 3.4, Finland 3.8, Germany 4.0, The Netherlands 3.7).

The same pattern (3 + 1) as in the case of “economy and migration” is revealed in “education and learning”, but the relationship of the countries has changed between 2010 and 2017. The average scores for all of the statements in this aspect increased for all of the countries. As a consequence of this increase, Czech scores became closer to the German and Dutch ones, but Finnish scores showed even more open-mindedness in 2017, which made Finland more notably distinct from the other countries. The most preferred statement (in all the countries) in this regard is related to the need of understanding the impacts of current policies on future generations, while the least preferred (but the scores still indicate open-mindedness) declares the scepticism that individual behaviour can affect people in other countries.

Finland, the Netherlands and Czechia recorded their highest average scores in “culture and attitudes to others”. This aspect is surpassed by “education and learning” and in 2017 even by “economy and migration” in Germany. This is because of the decrease of the average scores of all statements in this aspect between 2010 and 2017, while the scores for the other countries (slightly) increased. The specific position of Germany is underlined by the lower average score in the statement related to the perceived inconvenience of migrant’s religious beliefs.

Individual variability of the participants

The analysis of the participants’ variability is based on the typology of participants (see Appendix, ). Participants falling into types 1, 2, 3, 13 and 14 were the most frequent in the whole sample in both years. This documents the overall high level of world-mindedness of participants as all of the most frequent types fall under the open-minded category or under mid-stream with one open-minded aspect (specifically “education and learning” or “culture and attitudes to others”). This is supported by the least frequent types falling into the nation-minded category – four of the five least frequent types in 2010 and all of the least frequent types in 2017. However, the distribution of participants between types differs across participating countries (see ).

Table A3. Categories and types of participants.

The majority of Dutch participants (58.6%) in 2010 were mid-streamers, most frequently open-minded in “culture and attitudes to others” and “education and learning”. Only approximately one-third (36.5%) of them were open-minded, most of them applying national interests in “economy and migration” and “patriotism”. In 2017, in contrast, the majority (55.4%) was open-minded with more national interests in “patriotism” and “economy and migration”. More than 10% was a balanced open-minder, which is the most world-minded type. Only a minor share of participants was nation-minded in both years (4.9% in 2010 and 2.9% in 2017).

Contrary to the Netherlands, the results of German participants were more stable in both years. Approximately half of the participants (53.3% in 2010; 48.1% in 2017) were open-minded, and only a negligible proportion was nation-minded (3.8%; 5.5%) – although a slight decrease of open-minders and increase of nationalists were recorded. The most frequent in both years were balanced open-minders, followed by open-minders with national tendencies in “patriotism” and “economy and migration”. However, the last type was surpassed by mid-streamers with open-mindedness in “education and learning” in 2017.

The share of Finnish open-minded participants changed from 50.7% in 2010 to 60.4% in 2017. This was manifested especially in the increase of the most frequent type – open-minders with national tendencies in patriotism – to almost one-third of all participants in 2017. This was supported by the increase of balanced open-minders. In contrast, a decrease was identified in open-minders with national reservations to “economy and migration” similarly in mid-streamers open-minded in “culture and attitudes to others”.

Czechia has significantly lower shares (24.9%, resp. 23.0%) of open-minders in both years, as the majority of Czech participants are mid-streamers (69.4%, resp. 72.4%), especially open-minded in “culture and attitudes to others” and in “education and learning”. A noticeable shift was recorded between 2010 and 2017. While the open-minders with national tendencies in “economy and migration” were third-most frequent in 2010, their numbers decreased, and they were surpassed by the mid-streamers defending national interests in “economy and migration” in 2017. Thus, while the defence of national interests in “economy and migration” remained, the level of world-mindedness decreased. It is obvious that the lower scores of world-mindedness in Czechia are caused by the higher frequency of mid-streamers, as the share of nation-minded participants is comparable to other countries (approximately 5.0% in both years).

The share of nation-minded participants in Czechia and the Netherlands slightly decreased between 2010 and 2017 (Czechia 5.7% to 4.6%; the Netherlands 4.9% to 2.9%) and stayed almost stable in Finland (4.0%, resp. 4.2%). However, a slight increase was observed in Germany (3.8% to 5.5%).

Discussion

This research began after the increase of asylum seekers arrived in Europe in 2015. We were interested in finding out whether this rapid change had some effect on young people’s attitudes towards other cultures. The context of the “refugee wave” significantly differed in all the observed countries. Despite the different contexts in each country, the rapid rise in migration movements in all of them led to emotional debates resulting in societal polarisation.

In contrast to these debates and polarisation, the average world-mindedness scores among the students in all countries have stayed rather stable. The slight changes observed were almost all positive. This resonates with the findings of some earlier research. For example, Stockemer et al. (Citation2020, 18) found, against their prior assumptions, that immigration attitudes did not change among adults during the 2010s in Europe. Fundamental political values remained stable even when the situation changed rapidly. Moreover, differences in the median scores among countries participating in our study were rather small – they did not exceed 10 points (from the total range of 100 points). This is in contrast with the findings of Heath and Richards (Citation2019), who noted that even when attitudes towards immigrants on average stayed relatively stable in Europe despite the rise in migration, the divergence between European countries in their attitudes increased. In some countries, attitudes had become more generous while in other countries they had become more negative towards immigrants. Even when the overall public attitude towards refugees had stayed relatively stable after the changes in 2015, Lönnqvist et al. (Citation2020) showed how the polarisation of attitudes among the political elite was strengthened. However, a significant polarisation of young people’s world-mindedness was not proven by our findings. Although the polarisation can be supported by the increase of (extremely) open-minded participants, the numbers of (extremely) nation-minded participants stayed stable or decreased slightly in participating countries.

In total, participants of this study were open-minded in “culture and attitudes to others” and “education and learning”, while more national tendencies were revealed in “patriotism” and “economy and migration”. This is in line with the findings of previous studies (Béneker et al., Citation2013, Hanus et al., Citation2017, Pavelková et al., Citation2020). Nonetheless, when comparing the data to 2010, a greater national emphasis on “economy and migration” in Czechia and “culture and attitudes to others” in Germany was identified. It could be assigned to the concept of group threat (Berg, Citation2009) when part of the population can perceive immigrants as competitors – e.g. in the labour market (in case of countries with lower purchase power), cultural traditions. On the other hand, contact theory can help us explain the higher level of world-mindedness in countries with high numbers of asylum seekers – having direct contact with immigrants positively influences the openness of the population to them (Pavelková et al., Citation2020). Nevertheless, the influence of group threat theory on young people, when group threat is often spread via traditional media, can be weakened by not using traditional media and rather following social networks in their “social bubble” instead. Moreover, the use of global social networks can support contact theory, as it is easier for young people to be in touch with people with different life stories and cultural background, which can increase their world-mindedness.

Limitations of the study

The limitations of the study methodology and findings must be considered when interpreting the findings. First, limitations result from the structure of the research sample and its recruitment. It is crucial to be aware of the limited numbers of participants in each country, which means that the findings are not representative of the whole population of young people in each country. Second, the comparison of the results between 2010 and 2017 is made of findings of two surveys with the same methodology but with different samples. Therefore, the developmental tendencies revealed should be perceived with respect to the samples’ differences. Third, the researchers should always be aware of the reliability of the survey’s answers, as respondents may reply what they think is expected rather than what they actually think. This can be strengthened by the fact that the survey took place at schools with teachers present. In contrast, some cases of rebellion can be expected when surveying young people anonymously at schools, resulting in more extreme opinions being expressed.

The role and potential of geography education

The results of this research show that even when the rapid rise in migration movements was interpreted as a major political, economic and social problem in the public discussion across Europe, the majority of young people kept their interest in opportunities to encounter other people and valued opportunities to learn from them. The majority of open attitudes towards encounters are an important condition for learning intercultural competences. This is food for thought when teaching about current societal issues and debates about inequality, exclusion and solidarity.

It is important for geography teachers and teacher educators to remain sensitive to the opinions and attitudes that their students have towards other people and cultures. Studies of world-mindedness, global-mindedness and global understanding can be conducted as part of geography teaching, and they can encourage students to think about their own attitudes and possible sources behind them. These studies can also help them construct arguments and critically evaluate different sources of information. An example for this is the educational section of the Atlas of European Values (EValue, s.a.), which is made available for use in the classroom and is the study of attitudes between people and countries on a large variety of issues.

Nonetheless, we are aware that the contribution of geography education to the young people’s world-mindedness and its role in the students’ values and attitudes development is much more complex and should be of interest of future research. Findings of this study and newly raised questions can help design these future studies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The first data were collected in 2010 in Germany, the Netherlands and Finland and in 2011 in Czechia. The second study was carried out in Germany, the Netherlands and Finland in 2018 and in Czechia at the turn of 2016 and 2017. Considering this variability in data collection, we will use 2010 (for 2010 and 2011 data) and 2017 (for 2016/17 and 2018 data) to make the text clear and its message more understandable.

References

- Al-Maamari, S. N. (2020). Developing global citizenship through geography education in Oman: Exploring the perceptions of in-service teachers. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/10382046.2020.1863664.

- Béneker, T., Tani, S., Uphues, R., & van der Vaart, R. (2013). Young people’s world-mindedness and the global dimension in their geography education: A comparative study of upper secondary school students’ ideas in Finland, Germany and the Netherlands. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 22(4), 322–336.

- Berg, J. A. (2009). White public opinion toward undocumented Immigrants: Threat and interpersonal environment. Sociological Perspectives, 52(1), 39–58.

- Berlinghoff, M. (2018). Geschichte der Migration in Deutschland. Bundeszentrale für Politische Bildung. https://www.bpb.de/gesellschaft/migration/dossier-migration/252241/deutsche-migrationsgeschichte.

- Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek. (2021). Hoeveel mensen met een migratieachtergrond wonen in Nederland? Retrieved February 21, 2021 from https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/dossier/dossier-asiel-migratie-en-integratie/hoeveel-mensen-met-een-migratieachtergrond-wonen-in-nederland-

- Czech Statistical Office. (2019). Online Database. Retrieved 2019 14 April. https://www.czso.cz/csu/czso/home

- De Beer, J. A. A., & De Valk, H. A. G. (2019). De ontnuchterende rol van de wetenschap in het migratiedebat. Demos: Bulletin over Bevolking en Samenleving, 35(6). https://nidi.nl/demos/de-ontnuchterende-rol-van-de-wetenschap-in-het-migratiedebat. 1–6.

- de Miguel González, R., Bednarz, S.W., & Demirci, A. (2018). Why geography education matters for global understanding? In A. Demirci, R. de Miguel González, & S. Bednarz (Eds.), Geography education for global understanding (pp. 3–12). Springer, Cham.

- de Miguel González, R. (2021). From international to global understanding: Toward a century of international geography education. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 30(3), 202–217.

- Drbohlav, D. (Ed.). (2011). Migrace a (i)migranti v Česku – Kdo jsme, odkud přicházíme, kam jdeme? Prague: Sociologické nakladatelství SLON.

- Eurostat. (2016, March 4). Record number of over 1.2 million first time asylum seekers registered in 2015. Eurostat News Release 44. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/2995521/7203832/3-04032016-AP-EN.pdf/790eba01-381c-4163-bcd2-a54959b99ed6.

- EValue. (s.a.). Atlas of European values. https://www.atlasofeuropeanvalues.eu/.

- Finland in Figures. (2020). Helsinki: Statistics Finland. http://www.stat.fi/tup/julkaisut/tiedostot/julkaisuluettelo/yyti_fif_202000_2020_23214_net.pdf.

- García-Faroldi, L. (2017). Determinants of attitudes towards immigration: Testing the influence of interculturalism, Group Threat Theory and national contexts in time of crisis. International Migration, 55(2), 10–22.

- Hanus, M., Řezníčková, D., Marada, M., & Benéker, T. (2017). Globální myšlení žáků: Srovnání vybraných evropských zemí. Geografie, 122(3), 359–381.

- Hatton, T. J. (2017). Refugees and asylum seekers, the crisis in Europe and the future of policy. Economic Policy, 32 (91), 447–496.

- Heath, A., & Richards, L. (2019). How do Europeans differ in their attitudes to immigration? Findings from the European Social Survey 2002/03–2016/17. OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers222. https://doi.org/10.1787/0adf9e55-en.

- Herbert, U., & Schönhagen, J. (2020). Vor dem 5. September. Die “Flüchtlingskrise” 2015 im historischen Kontext. Bundeszentrale für Politische Bildung. Retrieved November 1, 2020 from https://www.bpb.de/apuz/312832/vor-dem-5-september-die-fluechtlingskrise-2015-im-historischen-kontext.

- Hett, E. J. (1993). The development of an instrument to measure global-mindedness (doctoral dissertation). San Diego: University of San Diego.

- Jelínková, M. (2019). A refugee crisis without refugees: Policy and media discourse on refugees in the Czech Republic and its implications. Central European Journal of Public Policy, 13(1), 33–45.

- Key Figures on Population by Region, 1990–2019. (2020). Statistics Finland’s PxWeb Databases. http://pxnet2.stat.fi/PXWeb/pxweb/en/StatFin/StatFin__vrm__vaerak/statfin_vaerak_pxt_11ra.px/.

- Lee, D.-M. (2018). Using grounded theory to understand the recognition, reflection on, development, and effects of geography teachers’ attitudes toward regions around the world. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 27(2), 103–117.

- Lönnqvist, J.-E., Ilmarinen, V.-J., & Sortheix, F. M. (2020). Polarization in the wake of the European refugee crisis: A longitudinal study of the Finnish elite’s attitudes towards refugees and the environment. Journal of Social and Political Psychology, 8(1), 173–197.

- Merryfield, M., Tin-Yau Lo, J., Cho Po, S., & Kasai, M. (2008). Worldmindedness: Taking off the blinders. Journal of Curriculum and Instruction, 2 (1), 6–20.

- Pavelková, L., Hanus, M., & Hasman, J. (2020). Attitudes of young Czechs towards immigration: Comparison of 2011 and 2016. Auc Geographica, 55(1), 27–37.

- Reynolds, R., & Vinterek, M. (2016). Geographical locational knowledge as an indicator of children’s views of the world: Research from Sweden and Australia. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 25(1), 68–83.

- Sampson, D. L., & Smith, H. P. (1957). A scale to measure world-minded attitudes. The Journal of Social Psychology, 45(1), 99–106.

- Scoffham, S. (2019). The world in their heads: Children’s ideas about other nations, peoples and cultures. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 28(2), 89–102.

- Solem, M., & Zhou, W. (2018). The role of geography education for global understanding. In Demirci, A., de Miguel González, R. & Bednarz, S. (Eds.) Geography education for global understanding (pp. 59–69). Springer, Cham.

- Statistisches Bundesamt. (2020). Bevölkerungsstand am 31. Dezember 2019. https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Gesellschaft-Umwelt/Bevoelkerung/Bevoelkerungsstand/Tabellen/zensus-geschlecht-staatsangehoerigkeit-2019.html.

- Stockemer, D., Niemann, A., Unger, D., & Speyer, J. (2020). The “refugee crisis”, immigration attitudes, and Euroscepticism. International Migration Review, 54(3), 883–912.

- Wahlbeck, Ö. (2019). To share or not to share responsibility? Finnish refugee policy and the hesitant support for a common European asylum system. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies, 17(3), 299–316.

- Werlen, B. (2018). Foreword. In Demirci, A., de Miguel González, R. & Bednarz, S. W. (Eds.) Geography education for global understanding (pp. v–viii). Cham: Springer.