Abstract

Many countries worldwide consider the demand for lowering the qualification level of teachers as a possible solution to the long-term lack of qualified teachers, aging teaching staff, and high teacher drop-out rate. In Czechia, geography is increasingly being taught by non-specialist teachers; therefore, we compared specialized and non-specialized geography teachers’ teaching conceptions. Drawing on previous robust qualitative research, we developed a questionnaire measuring teachers’ conceptions of geography teaching and surveyed Czech lower secondary in-service geography teachers (n = 530). Path analysis revealed that specialized geography teachers report longer and stronger relationships between the conceptions that may represent a wider range of geographies available to students. Non-specialized teachers demonstrated only a narrow and limited epistemological awareness of the subject. Our research serves as evidence supporting the inevitability of teachers’ specialization in the discipline.

Introduction

Despite varying contexts, geography in many countries is threatened by cuts in curriculum time or because it is increasingly being taught by non-specialist teachers (Butt, Citation2020). These trends are also noticeable in Czechia where the marginalization of geography in schools is accompanied by a long-term lack of qualified teachers, ageing of the teaching staff, and a high teacher drop-out rate (Maršíková & Jelen, Citation2019). These chronic gaps in school staffing have been resolved by the reduction of specialization demands on teachers as a key policy and strategy.

The discussion about the quality of geography teaching, however, lacks evidence on the differences between specialized and non-specialized teachers. Specialized teachers as knowledge experts are more likely to take greater risks in their classroom due to better understanding of the subject (Rogers, Citation2011), which has been confirmed in small-scale studies in geography education (Brooks, Citation2010, Citation2016; Lane, Citation2011; Lee, Citation2018; Puttick, Citation2016). Moreover, denying the relationship between specialization and the quality of teaching would mean questioning the purpose and function of the initial teacher education. In geography teaching, epistemological awareness of the subject is represented, among others, through geography conceptions, where some conceptions support learning more effectively than others (Lane, Carter, & Bourke, Citation2019).

This study attempts to reveal the impact that teachers’ specialization in geography has on their conceptions of geography teaching. In a large-scale study of Czech geography teachers, we proposed the following research question: How do conceptions of geography prevalent among teachers transform in relationship to their specialization or non-specialization in geography teaching?

The first part of this paper deals with the theoretical background and origins of the questionnaire used in this study. The second part details the questionnaire survey conducted to examine Czech in-service teachers’ perspectives on geography teaching. To conclude, we discuss implications for educational policy and the professional development of geography teachers.

State-of-the-art: a need for a large-scale research

Here we addressed the voices claiming that a large-scale study is required in geography education (Bednarz, Heffron, & Huynh, Citation2013; Butt, Citation2020). Zadrozny, McClure, Lee, and Jo (Citation2016) reviewed 191 research articles published on geography education in the last two decades. They concluded that among the 65 articles that were categorized as qualitative, 26 articles used slightly different methods to collect data. Moreover, they pointed out that “among the studies reviewed, there was not a single pair of articles of which the results are comparable.” (Zadrozny et al., Citation2016, p. 228).

Research focusing on teachers’ conceptions of geography teaching reduces the complexity of the qualitative phenomena, determining teachers’ multifaceted subject identity (Brooks, Citation2016), but overcomes the limited comparability of qualitative findings (Zadrozny et al., Citation2016). Although dozens of qualitative studies are available, there is still no valid instrument for determining teachers’ conceptions of geography teaching. To fill this research gap, we developed an original questionnaire that measures teachers’ geography conceptions. The data yielded by this provide a decontextualized “snapshot-in-time” information about teachers’ geographical epistemological awareness.

We decided to apply Catling’s (Citation2004) conceptions of geography teaching as a theoretical background for our study. Catling’s typology has a rich history, beginning in 1996 when Walford published a pioneering study describing the way his specialist geography teacher-training students perceived geography. Walford (Citation1996) classified pre-service teachers into categories, namely Interactionists, Synthesizers, Spatialists, and Placeists, based on different traditions of geographical thought (cf. Pattison, Citation1964). Walford’s approach was later followed by Reinfried (Citation2004) and Martin (Citation2000). Catling (Citation2004) added a second line of inquiry drawing on ideas from Martin (Citation2000) about teachers’ conceptualizations of the purpose of geography teaching because teachers appeared to hold two images of the subject, that of geography as a subject discipline and that of geography teaching. This involved adding new categories to the typology, namely, Global personalists, Localists, Locationists, and Map-lovers. The success of a teacher does not depend solely on their disciplinary knowledge but also on how they use their subject knowledge in teaching (Alexandre, Citation2016; Brooks, Citation2016). We utilise the nine Catling’s (Citation2004) conceptions of geography teaching: Globalist (factual knowledge about the world; descriptive geography), Earthist (knowledge and understanding of how the world works), Interactionist (focusing on the interdependence and interaction between humans and the environment), Placeist (understanding of culture and community; how places develop, what they are like, and why), and Environmentalist (sustainability; the impact of human activity on the environment).

To date, Catling’s typology is frequently used in international research of geography education that are framed by a range of terms—conceptions, perceptions, persuasions, beliefs, understandings. Minor nuances also appear in the labels of individual categories. Up to the present time, the research in exploring the conceptions of geography and geography teaching that is influenced by Catling’s typology has been primarily aimed at students (Senyurt, Citation2014), students of primary-level geography teaching (Bourke & Lidstone, Citation2015; Catling, Citation2004; Morley, Citation2012; Preston, Citation2014; Puttick, Paramore, & Gee, Citation2018), students of secondary-level geography teaching (Alkis, Citation2009; Knecht, Spurná, & Svobodová, Citation2020), and in-service teachers (Preston, Citation2015). Bourke and Lidstone (Citation2015) and Spurná, Knecht, and Svobodová (Citation2021) also applied Catling’s typology to curriculum analysis.

The findings presented by Spurná et al. (Citation2021) indicate that the perspectives regarding geography education play an essential role in the Czech curriculum. At the lower secondary level in Czechia exist progression inconsistency, imbalances between stated objectives and outcome measures, and the predominant occurrence of the globalist perspective aimed at declarative knowledge. These discrepancies might impact teachers’ lesson planning, conceptions, and attitude, in general. Limited or biased perspectives on geography education in the curriculum may cause situations where some teachers cannot align with their attitudes and conceptions of the subject (Martin, Citation2000, Citation2008).

Materials and methods

This study contributes to the validation of Catling’s typology through the questionnaire format, as it is still unclear whether individual conceptions of geography teaching exist across the geography teacher population and whether they are measurable using a quantitative approach. This quantitative study not only provides a large-scale overview of teachers’ conceptions but also clarifies whether and how these conceptions are distributed among the population of teachers.

We supplemented the present qualitative data based on structured, open-ended questions with a snapshot of how all the geography conceptions are reflected in the minds of the teachers in one moment. The quantitative approach allowed us to recognize what the relations among the conceptions are, whether any of them is dominant, whether any selected factors are influential, and whether these findings may be generalizable.

Construction of the questionnaire

The research questionnaire was based on Catling’s typology. We used nine fundamental Catling’s conceptions that have appeared in previous small-scale studies: Globalist, Earthist, Interactionist, Placeist, Environmentalist, Localist, Map-lover, Synthesizer, and Facilitator (see Appendix A). The design of the individual items was based on the interpretation of authentic statements of teachers reflecting their conceptions of geography teaching from previous research (e.g. Alkis, Citation2009; Bourke & Lidstone, Citation2015; Catling, Citation2004; Morley, Citation2012; Preston, Citation2014, Citation2015; Puttick et al., Citation2018; Senyurt, Citation2014). Topic items were selected for each conception to appropriately characterize its meaning. The first questionnaire version included seven items per conception. This version was piloted with pre-service geography teachers (Master’s degree students) since we did not wish to approach in-service teachers directly for piloting the questionnaire due to their enormous existing workload. After verifying the validity and reliability of the individual items in the pilot study, using Exploratory Factor Analysis and Cronbach’s Alpha, the inadequate items, which minimally saturated the conceptions or covered more conceptions with their meanings, were discarded. The final version of the questionnaire consisted of 45 items, with every conception containing five items (see Appendix B).

We formulated the items in a neutral manner to keep them unbiased. To do so, we avoided active verbs and other terms that might create the wrong impression. We used a 5-point Likert scale ranging from important (5 points) to irrelevant (1 point) for teaching geography. All study participants provided informed consent at the beginning of the questionnaire. Alongside these items, with reference to previous research, we also collected information about gender, length of teaching experience, specialization in geography teaching, and preference between physical, human, and regional geography.

Sampling

The survey was conducted in the first half of 2020, when the questionnaire was distributed online to geography teachers. Geography teachers in Czechia are not registered, therefore the randomization of the sample among the teachers was done on the level of schools that are registered with the Ministry of Education. According to the official data provided by the Ministry of Education in September 2019, there were 5374 lower secondary geography teachers in Czechia (Maršíková & Jelen, Citation2019).

We focused on lower secondary education because in Czechia, geography is taught in all its complexity at the comprehensive lower secondary level (from 6th to 9th grade), and geography teachers (with or without specialization) bear full responsibility for curriculum implementation. Regarding upper secondary levels, many secondary schools (such as technical secondary schools and vocational secondary schools) do not provide a systematic and consistent geography education (Řezníčková, Citation2003). At the upper secondary level, geography is mainly taught at advanced secondary schools (i.e. grammar schools; gymnázium), which culminates in a school-leaving examination at the end of secondary schooling (see Greger & Walterová, Citation2007). Taking this examination is voluntary.

We approached 1200 schools where geography is taught as a lower-secondary school subject, in two rounds of data collection (due to COVID-19 school closures) and addressed 200 teachers directly and 1000 teachers via their headteachers. The survey responses were submitted by 530 teachers who were in most cases approached via their headteachers. These teachers represent about 10% of the lower secondary geography teachers in Czechia and the response rate was 44%.

There were 328 female and 202 male teachers. Their average teaching experience was 14.4 years (SD = 10.5). A total of 410 respondents were geography specialist teachers, which is 77% of the research sample. These aspects of the sample indicate an appropriate representativeness of the data when compared to the total population of all Czech geography teachers because the official data show exactly the same ratios of specialized teachers and of gender distribution among the geography teachers in Czechia (Maršíková & Jelen, Citation2019).

As specialist teachers, we considered those teachers who had an MA degree in teaching geography. Practically, it means that the teachers have graduated from 1 of 8 public universities providing teacher training in geography in Czechia.

Data analyses

The collected data were examined through a set of descriptive and inductive analyses. Using SPSS Version 26.0 (IBM SPSS, Armonk, NY) and SPSS AMOS (license No. 25), we conducted the following analyses describing the psychometric characteristics of measurement: normality test (Kolmogorov-Smirnov), which demonstrated that our data were suitable for inductive statistics (d = 0.05; p > 0.20); and structural equation modelling (SEM, especially path analysis based on a combination of Pearson correlations and regressions), which also carried information about validity (criteria, such as root mean square error of approximation, Tucker-Lewis index, and comparative fit index). All observed criteria were in standard values. Reliability was indicated by Cronbach’s Alpha (α = 0.92), which demonstrated suitable internal consistency. The variation coefficient of all items was 9.6%. In addition, ANOVA (Levene’s test and post-hoc test) and simple Pearson correlation were conducted to uncover differences in the conceptions of the teacher population. To generalize our findings to the entire population of geography teachers, the level of statistical significance (p-values, <0.05, <0.01, and <0.001) was used. Cohen’s d was used as the substantive signification to measure the differences between the conceptions among the teachers.

SEM analyses were realized on the data matrix based on the value of arithmetic means for individual conceptions. All the conceptions were considered to be observed as endogenous variables. For the analysis, we selected the method of maximum likelihood. In addition to the conceptions, specialization in geography entered the analysis as another variable and became a foundation for structural modeling of path models. Based on this variable, three models emerged: initial model, specialized in geography model, and non-specialized in geography model. To verify the robustness of the variable for a multi-group SEM we applied, besides the psychometric characteristics such as construct validity and reliability of the geography teaching conception as the general construct, the measurement of item equivalence (configural, metric, scalar, and strict equivalences; see ). The stability index for the variables of all three structural models is at the interval ranging from 0.03 to 0.11, which may be declared as stable systems (Bentler & Freeman, Citation1983).

Table 2 . Item equivalence of multi-group structural equation modeling.

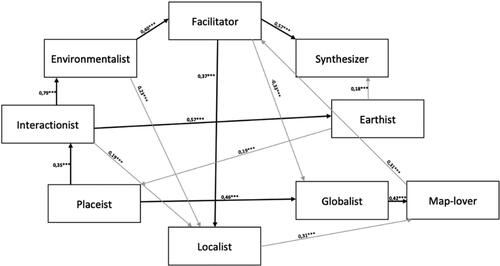

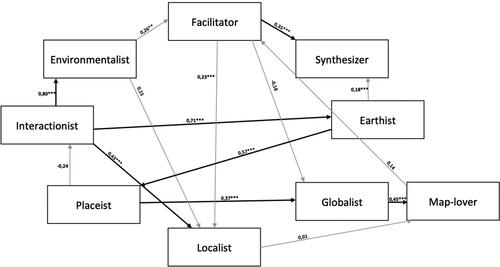

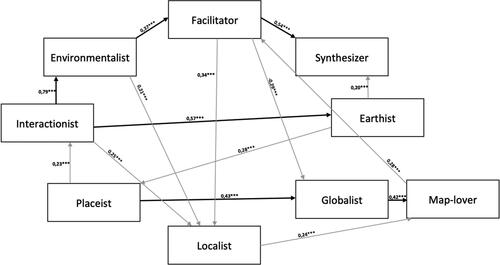

The equivalence values () show the same size of factor loadings, the arithmetic means, or the means of the variables but also in the standard error of the calculations across the groups (specialized and non-specialized teachers). This enables a direct comparison of the models for the teachers with and without specialization. For path analysis we used the regression (standardized β of standardized direct and indirect effects) between conceptions and squared multiple correlations (R2) as the estimation of variance of each conception to interpret the results of all the models. The first path analysis model calculated the regressions among all the conceptions (all conceptions explaining all conceptions). The reduction to the strong regressions (β > 0.35) and values of residuals led to designing the initial model (), which is typical for all Czech geography teachers regardless of their teaching specialization, and the other two ( and ) models. These demonstrate the variability of the relationships between the conceptions regarding teachers’ specialization or non-specialization in geography teaching.

Figure 1. Relationships among the conceptions (all teachers). Note: The most distinguished trajectories that are determined by the standardized direct but also by the indirect effects higher than 0.35 are highlighted.

Results

In this section, we present our findings about the conceptions of geography among Czech teachers and evaluate the relationships between the individual conceptions of geography teaching of specialized and non-specialized geography teachers.

shows that teachers scored high in all individual conceptions. Out of all the conceptions, the most preferred one was the generic skills-oriented Facilitator. This conception concentrates on the support of wider personal development in the students through geography education (e.g. developing critical thinking or pupils’ co-operation and collaboration). On the other hand, the least preferred conception was that of the Globalist, which describes a teacher who is oriented to factual and declarative geographical knowledge (e.g. general overview about continents and oceans or knowledge about individual countries, rivers, lakes, cities, etc.).

We also examined which factors determine teachers’ conceptions of geography teaching. The analyses revealed slight significance and minor nuances in all the measured groups of teachers’ preferred conceptions. From the gender perspective, the arithmetic means of all the conceptions were rather balanced (ranging in interval x = <3.55–4.04> for men and x = <3.55–4.15> for women). Similarly, minor differences in the arithmetic means for the individual conceptions are evident in the case of the preferences of physical (n = 185), human (n = 104), and regional (n = 241) geography. Similarly, the length of teaching experience was a non-significant factor too.

demonstrates that the conceptions of specialized and non-specialized teachers were predominantly balanced. The differences between these were very small, with the exception of Earthist, which was a significant factor (p = 0.00; d = 0.47). On a general level, we can state that the specialized geography teachers find the Earthist conception to be more important for teaching than the non-specialized teachers. The Earthist conception is anchored in Earth science topics that put emphasis on geographical reasoning and geographical inquiry.

Specialized and non-specialized teachers: differences between trajectories

Path analysis helps us identify the most important conceptions in geography teaching, which illustrate diverse disciplinary orientations among geography teachers. For all teachers, the conceptions of Placeist and Interactionist provided the strongest regressions. These two main conceptions, especially Placeist, created the three basic trajectories or groups of conceptions (): description-, science-, and capability-oriented trajectories. Each of these trajectories was launched by the influential conception that is the starting point for the regressions toward the other conceptions. We followed the variability of the trajectories depending on the specialization or non-specialization in geography of the respective teachers.

shows that with the specialized teachers the three trajectories indicated a more shared and higher understanding of individual conceptions (higher R2 values), apart from the conception of Placeist and Environmentalist. Meanwhile, with the non-specialized teachers (), most of the values decreased in the model, which amputated and significantly reformed the basic trajectories; these trajectories were shorter and not so abundantly interconnected.

While the specialized teachers have two main conceptions—Placeist and Interactionist, the non-specialized teachers have only one—Interactionist. This is also evidenced through a rather narrow perspective and limited ability of non-specialist teachers to teach geography with the backing of a variety of conceptions and paradigms of geographical thinking.

Description oriented trajectory

The description-oriented trajectory went from Placeist to Globalist to Map-lover (). It represents geography through locational knowledge, facts about regions and places, supported by maps. This trajectory was typical for specialized teachers (). With non-specialized teachers, this trajectory was slightly transformed: the influence of Placeist conception decreased (). Non-specialized teachers prefer descriptive and declarative knowledge approach to geography teaching without direct connections to specific places.

Science oriented trajectory

The science-oriented trajectory led from Interactionist towards Earthist () as it attempted to recognize and reveal the interactions between people and environment with the support of Earth science. An example of this could be the interactions between people and nature that become the core for learning about physical geography phenomena. The trajectory in this form and intensity appears in teachers specialized in geography. With non-specialized teachers, there is an evident diversion from Earthist to Placeist conception, which can be explained as insufficient comprehension of the Earth science and physical geography phenomena, especially their causes and effects. Non-specialized teachers, therefore, tend to demonstrate these geographical phenomena using anecdotal local examples (manifested through personal travel experiences). The presence of the Earthist and Placeist relationship by non-specialized teachers may be interpreted as the consequence of the reduction in all other relationships between conceptions.

Capability oriented trajectory

The capability-oriented trajectory began with Interactionist and targeted gradually towards Environmentalist, Facilitator, and Synthesizer (). This trajectory focuses mainly geographical thinking, allowing the pupils to apply geographical knowledge to different settings. It begins with the people/environment interactions, and it determines the interest in sustainability (including climate change) and concentrates on the development of pupils’ generic knowledge and skills through geography and the relationship between geography and other school subjects. This trajectory differs from the description-oriented trajectory with the Facilitator conception being negative in the relationship to Globalist. This may be interpreted as a counterweight of geography teaching based on declarative world knowledge. This trajectory requires from teachers a deeper geographical epistemological awareness, the use of many resources and perception of the current situation in the world in accordance with the pupils’ learning. With specialized teachers, this trajectory may be expanded with Placeist or possibly also Localist conception, which may be interpreted as the ability of specialized teachers to recognize and demonstrate the geographical phenomena on the examples from a range of places, including the local environment (e.g. by using fieldwork). Besides, the specialized teachers gradually develop their individual conceptions into an interdisciplinary understanding. For non-specialized teachers the trajectory was reduced to only two conceptions: while the relationship between Interactionist and Environmentalist prevailed, the influence of Placeist and the remaining relationship between Facilitator and Synthesizer faded. Non-specialized teachers in this trajectory construct their conceptions based mainly on people/environment interactions and relate them to environmental issues and sustainability. The variability, applicability, interdisciplinarity, and depth of geography, which the specialized teachers develop, are lost.

With non-specialized teachers, it is possible to trace a sole relationship between Interactionist and Localist. We interpret this as an effort of the teachers to demonstrate people/environment interactions with examples from the local environment, typically through fieldwork around the school. Nevertheless, this is where the trajectory ends.

Discussion

The path analysis showed two conceptions as crucial, that of Interactionist and Placeist. These two conceptions significantly influence the teachers’ views of geography teaching which means that the Czech teachers define geography as a discipline that is primarily based on an interest in humans and their interactions with the physical environment in different spaces and places. Interactionist and Placeist conceptions are the bases for three influential trajectories interconnecting other conceptions: description-, science-, and capability-oriented. The labels for these trajectories reflect geography teachers’ ways of thinking and deciding about teaching. In the case of the specialized teachers, the path analysis model shows stronger relationships and at the same time longer trajectories between conceptions. With non-specialized teachers, the relationships between the conceptions were weaker or absent.

Our research serves as evidence supporting the inevitability of teachers’ specialization in the discipline because the undergraduate teaching experience clearly defines what it means to be a geography teacher. Teachers’ subject expertise “can be seen as a tool that they use to interpret and negotiate their teaching practice” (Brooks, Citation2010, 147). During specialized teacher training, the teachers are exposed to the opportunities for reconceptualization and reproduction of subject knowledge for teaching and in this way, they can construct and develop their own subject identity (Brooks, Citation2016). An important feature of geography taught at all levels of education is the variety of traditions of geographical thought and geographical knowledge that are available to teachers and students (Morgan, Citation2002). We reference Preston (Citation2015), who presented evidence that we need teachers with subject specialization in geography teaching if we want the pupils to be exposed to a wide range of geography and to impart geography knowledge in a meaningful way to pupils. Our study confirmed other authors’ findings that only qualified teachers with a background in geography hold a clear understanding of geography which can be regarded as powerful disciplinary knowledge (Lane, Citation2011; Lee, Citation2018; Puttick, Citation2016; Virranmäki, Valta-Hulkkonen, & Rusanen, Citation2019).

Our findings reinforce the need to develop and expand teachers’ awareness about different conceptions of geography teaching e.g. through in-service teacher training courses. As Martin (2000) and Preston (2014) point out, teachers with limited perceptions of geography pass these on to the students. Only teachers who are familiar with different conceptions of geography teaching are capable of establishing a balance among different conceptions in their teaching practice. The developed and interconnected trajectories of conceptions of geography prove that specialization in geography teaching may play a crucial role in the process of shaping desirable teachers’ subject identity. Specialization of teachers is also assumed to be the essence of developing geography education’s potential through the capability approach (Bustin, Citation2019).

It is significant to highlight the curricular context of the study. Although the findings of Spurná et al. (Citation2021) indicate that the lower secondary geography curriculum in Czechia is mainly oriented toward the information-based globalist perspective, the globalist conception had the lowest scores among the teachers. We interpret this situation in two ways: first, the national curriculum does not directly influence the teachers’ conceptions of geography as the alignment with teaching attitude is missing; secondly, the teachers’ marginal negative inclination toward the globalist conception might be caused by the social desirability of the responses.

Regarding the methodology the survey confirmed “small and valuable discoveries” stemming from earlier qualitative inquiries into conceptions of pre-service or in-service geography teachers’ analysis (see Bradbeer, Healey, & Kneale, Citation2004; Martin, Citation2000; Morley, Citation2012; Preston, Citation2014). It can be concluded from this study that adding a quantitative design resulted in a better understanding of how geography teachers manifest their epistemological awareness of the subject. Even though other researchers often conclude that teachers’ conceptions of geography and geography teaching may be somewhat messy and not fitting into defined categories (Clausen, Citation2018; Lane, Citation2011; Walshe, Citation2007), our research findings indicated that teachers’ conceptions of geography teaching based on Catling’s ideas may be a valid and measurable construct.

Even though we are aware of the criticism of a research design based on direct questioning because survey data do not allow the exploration of conceptions of geography and its sources in more detail (Puttick et al., Citation2018), we decided to follow and elaborate on the direct approach. Our quantitative data allow us to specify and expand knowledge based on structured, open-ended questions with the possibility to analyze how the geography conceptions are reflected in the mind of a teacher in a specific moment and describe the relationships between them. Since the teachers scored relatively high in judging all conceptions of geography teaching, we consider replacing the Likert scale in the dimensions of the questionnaire with ranking the statements that characterize the conceptions according to the importance.

Naturally, this research had some limitations. Firstly, it is possible that teachers in other countries might have other perspectives. Secondly, it should be noted that our results analyzed the data concerning the question of what geography teachers consider to be important in teaching the subject. However, we don’t know whether their preferred conception is also evident in their behavior while teaching. Thirdly, it is challenging to talk about a typology of conceptions of geography teaching and subsequently about types of geography teachers. Conceptions of geography are dynamic and in the case of individual teachers, it is more accurate to talk about dominant or prevailing conceptions that manifest and determine just a small but relevant piece of their subject identity.

Conclusion

We provide evidence that implementation of policies enabling non-specialized teachers to teach geography may result in a lower quality of teaching. As countries around the world consider diminishing qualification demands on the teachers to be one of the possible solutions to chronic gaps in schools staffing, policymakers should consider the consequences. Our research supports the assumption that well-developed disciplinary and subject knowledge gained in specialized teacher training enable the teachers to present geography in its full scope and mediate for the pupils a variety of geographical thinking.

The findings show that specialized teachers have a deeper geographical epistemological awareness manifested through wider aims, scope, rationale, and depth of geographical thinking, and that they connect geographies taught by them with the learning needs of their pupils. Teachers specialized in geography teaching demonstrate through their trajectories that they perceive teaching geography as an opportunity to communicate people/environment interactions in specific and changing places. They are prepared to decide whether and how to explain these interactions and possibly also to depict the environmental (including sustainable development and climate change), local, and interdisciplinary contexts. Finally, they also connect geographical knowledge with everyday life. On the other hand, non-specialized teachers cannot fully develop the potential geography has in education. Their trajectories signify a possible threat in terms of reducing geography to a descriptive discipline about places and maps or demonstrating geographical phenomena using examples of specific places without any deeper explanations or understanding regarding the core or the causes and effects. Possibly, they may reduce geography to a practical discipline about sustainability and climate change. Concurrently, it is necessary to highlight that non-specialized teachers do not attain the Facilitator conception in the trajectories, which may be interpreted as a lack of utilization of geography for the personal development and generic skills of their pupils.

Even though our research enables one to capture a mere “snapshot” of teachers’ conceptions of geography teaching in time, it is a challenge for us to compile more “snapshots” that could declare the development and dynamics of conceptions in time and place. In future, we would like to explore the similarities and differences in conceptions between pre-service and in-service teachers and compare teachers’ conceptions of geography teaching in different countries.

Table 1 . Arithmetic means for the conceptions of geography teaching in relation to specialization in teaching geography.

Data availability statement

A data set associated with the paper supporting the results or analyses presented in the paper is available on request by the authors.

Disclosure statement

This is to acknowledge any financial interest or benefit that has arisen from the direct applications of your research.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alexandre, F. (2016). The standardization of geography teachers’ practices: A journey to self-sustainability and professional identity development. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 25(2), 166–188.

- Alkis, S. (2009). Turkish geography trainee teachers’ perceptions of geography. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 18(2), 120–133.

- Bednarz, S., Heffron, S., & Huynh, N. T. (2013). A road map project for 21st century geography education: Geography education research. National Geographic Society.

- Bentler, P. M., & Freeman, E. H. (1983). Tests for stability in linear structural equation systems. Psychometrika, 48(1) 143–45.

- Bourke, T., & Lidstone, J. (2015). Mapping geographical knowledge and skills needed for pre-service teachers in teacher education. SAGE Open, 5(1), 2158244015577668.

- Bradbeer, J., Healey, M., & Kneale, P. (2004). Undergraduate geographers’ understandings of geography, learning and teaching: A phenomenographic study. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 28(1), 17–34.

- Brooks, C. (2010). Why geography teachers’ subject expertise matters. Geography, 95(3), 143–148.

- Brooks, C. (2016). Teacher subject identity in professional practice: Teaching with a professional compass. Routledge: London.

- Bustin, R. (2019). Geography education’s potential and the capability approach. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Butt, G. (2020). Geography education research in the UK: Retrospect and prospect. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

- Catling, S. (2004). An understanding of geography: The perspectives of English primary trainee teachers. GeoJournal, 60(2), 149–158.

- Clausen, S. W. (2018). Exploring the pedagogical content knowledge of Danish geography teachers: Teaching weather formation and climate change. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 27(3), 267–280

- Greger, D., & Walterová, E. (2007). In pursuit of educational change: The transformation of education in the Czech Republic. Orbis Scholae, 1(2), 11–44.

- Knecht, P., Spurná, M., & Svobodová, H. (2020). Czech secondary pre-service teachers’ conceptions of geography. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 44(3), 458–473.

- Lane, R. (2011). Exploring the content knowledge of experienced geography teachers. Geographical Education, 24(2011), 51–63.

- Lane, R., Carter, J., & Bourke, T. (2019). Concepts, conceptualization, and conceptions in geography. Journal of Geography, 118(1), 11–20.

- Lee, D. M. (2018). Toward a typology of changes in primary teachers’ awareness of geography based on receiving graduate education. Journal of Geography, 117(5), 216–228.

- Maršíková, M., & Jelen, V. (2019). Hlavní výstupy z Mimořádného šetření ke stavu zajištění výuky učiteli v MŠ, ZŠ, SŠ a VOŠ [Main findings from the extraordinary survey on the status of teaching profession in kindergartens, primary schools, secondary schools and vocational schools]. Czech Ministry of Education.

- Martin, F. (2000). Postgraduate primary education students’ images of geography and the relationship between these and students’ teaching. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 9(3), 223–244.

- Martin, F. (2008). Knowledge bases for effective teaching: Beginning teachers’ development as teachers of primary geography. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 17(1), 13–39.

- Morgan, J. (2002). “Teaching geography for a better world”? The postmodern challenge and geography education. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 11(1), 15–29.

- Morley, E. (2012). English primary trainee teachers’ perceptions of geography. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 21(2), 123–137.

- Pattison, W. D. (1964). The four traditions of geography. Journal of Geography, 63(5), 211–216.

- Preston, L. (2014). Australian primary pre-service teachers’ perspectives of geography. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 23(4), 331–349.

- Preston, L. (2015). Australian primary in-service teachers’ perspectives of geography. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 24(2), 167–180.

- Puttick, S. (2016). An analysis of individual and departmental geographical stories, and their role in sustaining teachers. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 25(2), 134–150.

- Puttick, S., Paramore, J., & Gee, N. (2018). A critical account of what “geography” means to primary trainee teachers in England. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 27(2), 165–178.

- Reinfried, S. (2004). Do curriculum reforms affect classroom teaching in geography? The case study of Switzerland. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 13(3), 239–250.

- Řezníčková, D. (2003). Geographical education in Czechia: The past, present and future. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 12(2), 148–154.

- Rogers, G. (2011). Learning‐to‐learn and learning‐to‐teach: The impact of disciplinary subject study on student‐teachers’ professional identity. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 43(2), 249–268.

- Senyurt, S. (2014). Turkish primary students’ perceptions of geography. Journal of Geography, 113(4), 160–170.

- Spurná, M., Knecht, P., & Svobodová, H. (2021). Perspectives on geography education in the Czech National Curriculum. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 30(2), 164–180.

- Virranmäki, E., Valta-Hulkkonen, K., & Rusanen, J. (2019). Powerful knowledge and the significance of teaching geography for in-service upper secondary teachers – a case study from Northern Finland. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 28(2), 103–117.

- Walford, R. (1996). What is geography? An analysis of definitions provided by prospective teachers of the subject. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 5(1), 69–76.

- Walshe, N. (2007). Understanding teachers’ conceptualisations of geography. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 16(2), 97–119.

- Zadrozny, J., McClure, C., Lee, J., & Jo, I. (2016). Designs, techniques, and reporting strategies in geography education: A review of research methods. Review of International Geographical Education Online, 6(3), 216–33.