Abstract

Academic language in geography education has attracted attention due to the increasing linguistic heterogeneity in most classrooms. Considering that subject-specific language differs from the language students use in their everyday lives, language-aware geography education contributes to addressing subject-specific language demands. However, there seems to be little empirical research and no systematic overview available concerning this topic. Thus, the aim of this study is to systematically review publications that empirically researched language in geography education to provide a synthesized state of knowledge for future research in this field. In accordance with the PRISMA guidelines, a final selection of 38 studies from three literature databases–Web of Science, ProQuest, and Scopus–were analyzed in this study. The empirical studies were categorized with reference to their subject-specific themes, concepts of space, and working methods, as well as the examined language. The main findings showed that the studies primarily examined language at the text/discourse level and in the written language mode. Particularly, the studies predominately investigated reading skills. Furthermore, physical geographical themes were at the center of the set of publications. This systematic review has both theoretical and practical implications for future research on the role of language in geography education research.

1. Introduction

Written and spoken language skills—two of the most important components of educational processes—are gaining importance in content areas, especially in the wake of increasing globalization and migration (Peukert & Gogolin, Citation2017). In such a context, linguistic heterogeneity in geography classrooms creates students’ language and learning barriers by limiting their access to academic content (Fang, Schleppegrell, & Cox, Citation2006; Spires, Kerkhoff, Graham, Thompson, & Lee, Citation2018). This is particularly significant because the subject-specific features of the language used in geography may not be familiar to students, depending on their amount of socialization and prior linguistic knowledge (Peukert & Gogolin, Citation2017). Moreover, the demands of the language that students use in their everyday lives are different from those of the language specific to a subject (Halliday, Citation1999; Snow & Uccelli, Citation2009).

As subject-specific language becomes increasingly relevant as a means of learning and achievement in geography education, there is a desideratum concerning the systematization of its empirical research. Thus, this systematic review aims to generate knowledge on quantifying and systematically accounting for the proportion of existing empirical studies that emphasize the role of language in geography education research. Furthermore, if researchers have access to a comprehensive systematization of existing publications in that field, future studies on the role of language in empirical geography research can only add value to the discourse.

The results of this systematic review will shed light on the following guiding research questions:

RQ1: To what extent has language in primary and secondary geography education been researched?

RQ2: Which subject-specific themes, methods, and concepts of space do the studies refer to?

2. Theoretical framework

Geography is an exceptional subject that aims to enable students to produce knowledge about the world and shape their perspectives on it across different spatial and temporal dimensions and interconnections (Brooks, Citation2017; Lane & Bourke, Citation2019). Thus, the development of students’ holistic understanding of geographical processes regarding the human-environment relations constituting geographical thinking is of primary importance to identify spatial patterns and connected issues (Alexandre, Citation2009; Lambert, Citation2011; Puttick & Cullinane, Citation2022).

From an epistemological perspective, subject-specific language creates the basis for students’ geographical thinking as it is the primary means to access the content- and language-related nature of geography: “[…] thinking geographically and communicating geographically are inextricably entwined with one another” (Delaney & Hay, Citation1997).

Geography has its distinct subject-specific language, e.g. vocabulary, syntax, and grammar, which needs to be acquired as a basis for understanding geographical content, concepts and principles taught in class (Gallagher & Leahy, Citation2019; Kirk, Citation1995).

Consequently, language and the subject are closely connected. Despite the interwoven notion of the subject of geography and its language, the most characteristic key features of each concept will be identified separately in this study to systematically develop categories, thus creating basic categorization schemes.

2.1. Conceptualizing the subject of geography

The subject of Geography, at its core, deals with spatial phenomena (Gersmehl, Citation2014). Many geographers and geography educators classify the themes of the subject into physical geography with subdisciplines in, e.g. geology, geophysics, climatology and on the other hand, human geography with subdisciplines related to, e.g. urban development, economics, ethnology (Gersmehl, Citation2014; Lambert & Balderstone, Citation2012). The subject especially includes themes connected to interrelations between human and natural systems, e.g. climate change, migration. Moreover, it is dynamic in nature because societies are constantly evolving, and so are scientific insights (Lambert & Balderstone, Citation2012; Puttick & Cullinane, Citation2022).

The concept of space is fundamentally geographical since it is regarded as a means to address the complexity of the earth as a dynamic system (Bednarz & Lee, Citation2019; Symaco & Brock, Citation2017). Accounting for the fact that geographers conceptualize space in different ways, e.g. as space, place, and scale (Cresswell, Citation2008; Lambert, Citation2011; Taylor, Citation2009) or space as a container, locational relation, object of perception, and social construct (Wardenga, Citation2002), this study, summarizes the different concepts of space into two contrary notions. First, space is defined based on neutral quantifiable characteristics, structures, and functions of geographical phenomena, which we call physical-material space (Bednarz & Lee, Citation2019; National Research Council, Citation2006). Second, space is defined from a constructivist perspective, including individual and collective perceptions or space as a social product of communication and practices, which we call perceptual, constructed space (Weiss, Citation2020).

The way students handle spatial or geographical information leads to the development of competences concerning working methods. These refer either to the acquisition, presentation or evaluation of geographical information, which are based on the collection of data or working with discontinuous texts, such as maps, diagrams, and satellite images (Lambert & Balderstone, Citation2012). Furthermore, graphical, visual, and textual presentations of geographical information are included through the presentation of procedural connections as in concept maps, demonstration of spatial relations using, e.g. mental maps, or increasing graphicness through creating diagrams (Lambert & Balderstone, Citation2012). summarizes the key features of the subject’s categories.

Table 1. Summary of the categories of geography.

2.2. Conceptualizing language in geography education

Subject-specific language in geography education can be conceptualized based on three language dimensions (word, sentence, and text/discourse level) as well as language actions (reception, production, interaction, and mediation). A summary of the key features of language actions is illustrated in .

Table 2. Summary of the categories of language actions.

It has been well established among scholars that subject-specific language can be considered at the word, sentence, and text/discourse level (Abedi et al., Citation1997; Schleppegrell, Citation2004). The word level includes subject-specific terminology that is characteristic of the subject and communicates geographical concepts that need to be cognitively accessed (Spires et al., Citation2018). In addition, the meaning of terms used in geography classrooms may differ from their meaning as known in everyday language (Gallagher & Leahy, Citation2019; Morawski & Budke, Citation2017).

At the sentence level, subject-specific words are embedded in phrases. These phrases occur in similar structures, especially when dealing with subject-specific working methods (e.g. chunks). In addition, the sentence level encompasses basic communicative language actions (Schleppegrell, Citation2004).

Finally, the text/discourse level poses the highest linguistic demands, as it includes characteristics of both the word and sentence levels, as well as cohesion-related complexity (Berendes et al., Citation2018; Budke & Kuckuck, Citation2017). At this level, language is regarded to be connected with continuous and discontinuous texts in geography education. It refers to reading and producing texts that are characterized by precise and concise language, dense information, and geography-specific terms describing complex processes (Schleppegrell, Citation2004; Snow & Uccelli, Citation2009).

Apart from the language dimension, communicative language actions (reception, production, interactions, mediation) and strategies of the reputable Common European Framework of Reference for Languages provide a more profound categorization scheme for language used in geography education. The language actions, depicted in terms of both written and spoken language modes (Council of Europe, Citation2020), are as follows:

Reception generally refers to the oral and written understanding of content. Receiving geography-specific language and content through spoken language, e.g. teacher talks or audio, and written language, e.g. continuous and discontinuous texts requires students to cognitively process and decode the spoken and written inputs (Morawski & Budke, Citation2017). Written reception is of particular importance to this study, as it includes the explicit language skills of reading comprehension (Council of Europe, Citation2020). Since reading is one of the sources of information construction, reading a text and reading a map have been particularly categorized in this study (Chang et al., Citation2021; Hinde et al., Citation2011; OECD, Citation2019).

Production refers to spoken and written language based on previously decoded and understood geography-specific information. In this study, the category of writing a formal text was added to written production to emphasize the more formal types of writing in geography lessons (Council of Europe, Citation2020; Morawski & Budke, Citation2017).

Third, spoken and written interaction may include the co-constructed exchange of geography-specific information and perceptions among students (symmetrical) and between students and teachers (asymmetrical). In addition, students ought to react to spoken contributions in appropriate geography-specific language (Morawski & Budke, Citation2017).

Finally, mediation refers to constructing and conveying meaning across different modes and media (Council of Europe, Citation2020). This could apply to explaining geographical issues based on, e.g. maps. Apart from this, mediation also involves transferring geographical information and data into other forms of representation (Morawski & Budke, Citation2017).

Argumentation competence is embedded, as it makes “student scientific thinking and reasoning visible” (Osborne et al., Citation2004, p. 995). Reasoning was added to argumentation in our categorization scheme as the structure or form of arguments, according to the Toulmin scheme (data, warrant, backing, qualifier, claim), is regarded as quality criteria in geography education (Toulmin, Citation2003).

However, despite this detailed differentiation, which is necessary to define a concrete categorization scheme, it is important to note that language dimensions and actions are closely interrelated in reality (Council of Europe, Citation2020).

3. Method

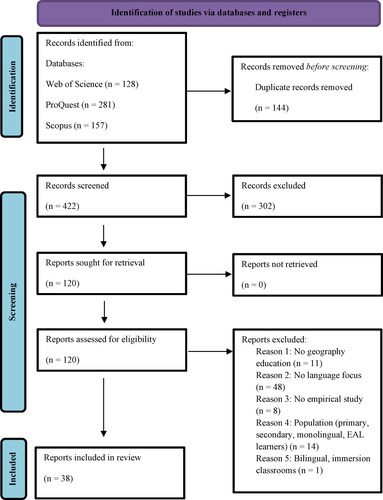

To address the research questions of this study, a systematic review of the English language literature on language in geography education research was conducted following the PRISMA guidelines (Page et al., Citation2021). In addition, a methodological approach was constructed by considering the inclusion and exclusion criteria to determine the selection of studies, which were then reviewed based on a theoretically derived and predefined literature-based categorization scheme (see Section 2). The resulting PRISMA scheme is displayed in .

Figure 1. Systematic search and selection process based on the PRISMA statement.Source: Adapted for this study based on Page et al. (Citation2021).

3.1. Literature search

A systematic search was conducted in three literature databases—ProQuest, Scopus, and Web of Science. We included Web of Science because it has the largest number of peer-reviewed publications followed by Scopus (Creswell, Citation2002). We further added ProQuest to also be able to access dissertations. Additionally, we developed a search protocol using an appropriate search syntax for language use in geography education that was applied to the respective literature databases from 1 January 2000 to 17 November 2021:

AB=(“geography” OR “earth science”) AND AB=(“secondary school*” OR “high school*” OR “elementary education” OR “primary school*”) AND AB=(“academic language” OR “reading” OR “writing” OR “communication” OR “argument*” OR “reasoning” OR “vocabulary” OR “scientific litera*” OR “language us*”)

Quotation marks were added to ensure that complete terms were included during the search process. However, in the case of ProQuest, curved brackets were applied in addition to quotation marks. Apart from this, regarding the level of education, we added synonyms that evolved after finishing the preliminary searches. Moreover, truncations (*) were applied to the search syntax for Web of Science and Scopus to ensure that the various word endings of the terms were included. The terms of the syntax referring to language in geography education were inferred from preliminary searches and included rather explicit language-related key skills, e.g. “reading” or “writing” (Brown & Ryoo, Citation2008; Snow & Uccelli, Citation2009).

3.2. Literature analysis

The final search was conducted on 17 November 2021, resulting in 422 publications after deducting duplicates. The titles, keywords, and abstracts of these publications were then screened according to the following inclusion and exclusion criteria (after which 302 publications were excluded):

The publication must be peer-reviewed.

The publication must be in English to ensure a transparent and replicable approach.

Empirical publications must include the aims of the research, descriptions of participants, study designs, and data.

The study’s focus should be on language in geography education, including language actions indicated by the Council of Europe (Citation2020).

The article’s context should refer to primary and secondary geography education and its students. Publications examining teacher variables or parents’ views were excluded.

Publications on research conducted in monolingual classrooms, which may involve students with English as additional language (EAL) backgrounds, were included. We excluded publications on bilingual or immersion education, as they involve undertaking a different approach toward foreign language acquisition (Dalton-Puffer & Smit, Citation2013; Nikula, Citation2016).

Publications on research involving students with special needs were excluded.

The results were screened by an independent second rater. We found that the interrater reliability resulted in ϰ = 0.92, indicating an almost perfect agreement (Brennan & Prediger, Citation1981). All discrepancies were resolved through discussion and a consensus was found.

Following the full-text screening of 120 publications based on the respective inclusion and exclusion criteria, 38 papers were found to be eligible for inclusion in this systematic review and were exported into an Endnote Library. Data extraction was carried out by one researcher and then systematized based on the categorization schemes.

4. Results

This section addresses the research questions outlined above from a descriptive perspective.

4.1. To what extent has language in primary and secondary geography education been researched?

4.1.1. Language dimension

Most of the publications analyzed in this study investigated language at the text/discourse level (33 studies). Approximately one-third of these studies also examined language at the word level, while two studies focused solely on researching language at the word level (Adams, Citation2009; Dal, Citation2008).

4.1.2. Language mode

It was observed that the written language mode has been extensively investigated in the literature. Notably, there was only one study (Kerlin, McDonald, & Kelly, Citation2010) that focused solely on the spoken language of students.

4.1.3. Language actions

The language actions of the studies were mainly observed to be at the productive (52.6%) and receptive (52.6%) levels. Furthermore, overlaps were identified among seven studies that reported on both language actions (Adeyemi & Cishe, Citation2016; Cleary, Citation2019; Dal, Citation2008; Lee, Citation2010; Rampersad, Shahiba, & Ali, Citation2020; Suwono, Salmah, & Tenzer, Citation2020; Thomas, Citation2017).

4.1.4. Language skills

Explicit language skills, e.g. reading a text (14 studies) and a map (5 studies), writing a formal text (8 studies), provided a more in-depth overview of language in the included studies, as shown in . In addition, argumentation/reasoning appeared as the primary language skill that had been researched in terms of various language action levels, and in the spoken and written modes (11 studies). Particularly, argumentation/reasoning appeared to have been researched mainly at the written production (5 studies) and mediation (4 studies) levels.

Table 3. Reported language skills.

provides an overview of the reported language dimensions and actions in primary and secondary geography education.

Table 4. Reported language in geography education research.

Table 5. Reported subject-specific themes, concepts of space, and working methods.

4.2. Which subject-specific themes, methods, and concepts of space do the studies in primary and secondary geography education refer to?

summarizes which subject-specific themes, methods, and concepts of space are addressed within the analyzed publications.

4.2.1. Themes

The most frequently reported themes in the publications analyzed in this study were rooted in physical geography (22 studies), since the studies were mostly implemented in earth science classrooms (Adams, Citation2009; Chang, Citation2010; Chang et al., Citation2021; Kerlin et al., Citation2010; Lee, Citation2010; Nuryanti et al., Citation2019; Pallant et al., Citation2020; Pedretti, Citation2009; Polman & Pea, Citation2001; Thomas, Citation2017; Voss, Citation2011; Yoo et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, themes concerning interconnections between physical and human geography, e.g. climate change, were extensively reported in the studies (12 studies). Apart from this, few studies were noticeably concerned with themes that were merely connected to human geography (Lee, Citation2006; Reich, Citation2009; Richter et al., Citation2012).

4.2.2. Working methods

The reported working methods in the studies were in accordance with the primary importance of discontinuous texts in geography education. Geography-specific working methods, particularly maps, were reported most frequently (6 studies). Further geography-specific working methods that were mentioned in the studies were working with graphs (Karasavvidis et al., Citation2000; Lee, Citation2006; Suwono et al., Citation2020) and data (Kerlin et al., Citation2010; Nuryanti et al., Citation2019; Suwono et al., Citation2020).

4.2.3. Concepts of space

The concepts of space rarely received much attention in the studies, as they were mentioned implicitly. In a large number of studies, the concept of space was not specified (10 studies). Apart from this, the materials, tasks, and practical methods described in the majority of the publications referred to the physical-material space (23 studies), while about one-third of the 38 studies included the perceptual, constructed space (10 studies).

5. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to gain a better understanding of the role of language in primary and secondary geography education research. Additionally, the current study provides insights into the subject of geography through the analysis of relevant publications across several categories, as outlined above. This systematic review was guided by the following research questions:

RQ1: To what extent has language in primary and secondary geography education been researched?

RQ2: Which subject-specific themes, methods, and concepts of space do the studies in primary and secondary geography education refer to?

We identified 38 peer-reviewed publications that empirically investigated the above outcomes. Following the examination of the systematic review, three key findings were identified in the present research. First, the reported publications predominantly examined language at the text/discourse level (33 studies) rather than the word (10 studies) and sentence levels (4 studies). Second, it became evident that written language (33 studies) was at the center of the publications compared to spoken language (14 studies). Notably, ten of the selected studies researched both language modes. Third, the geographical content of the publications primarily referred to physical-geographical themes (22 studies), as opposed to human geographical themes (3 studies).

Our first and second findings highlight that examined language at the text/discourse level appears in connection with both continuous and discontinuous texts in geography education research, which is in accordance with our theoretical framework (Berendes et al., Citation2018; Snow & Uccelli, Citation2009). Additionally, the main language skill researched in the selected set of studies was reading a text, with Alford and Windeyer (Citation2014), Chang et al. (Citation2021), Lee (Citation2010) and Ward-Washington (Citation2001) being exemplary publications. In this regard, it is interesting to note that the language-aware teaching of reading as a key language skill was at the center of these studies. For instance, Alford and Windeyer (Citation2014) explored reading skills of EAL students based on a “language-driven content and language integration model where content is used as a vehicle to learn the target language (Banegas, 2012; Met, 1999)” (p. 79). An interesting finding of this particular study is that language-aware geography education can be enhanced by utilizing the expertise of language teachers, who can “investigate the language demands of geography (…) to identify the literacy practices within geography that create opportunities for learning” (p. 91). This idea is further supported by the research findings of Ward-Washington (Citation2001), which states that, “It is recommended that high school content area teachers are trained in the most current reading research practices especially strategic reading instruction” (p. 67). One interpretation of these findings is that language and content are closely intertwined, thus highlighting that the proficiency in reading skills provides students with access to a more profound understanding of displayed geographical information and spatial patterns, thus enabling them to anticipate future spatial issues across spatial and temporal dimensions (Alexandre, Citation2009; Lambert, Citation2011).

It is a well-known fact that reading skills are key to educational achievements (Gallagher & Leahy, Citation2019; OECD, Citation2019; Seah & Chan, Citation2021). Considering this, it is interesting to note that the study by Chang et al. (Citation2021) also supports the notion that there is a positive correlation between students’ reading skills and subject-specific achievements. This is further supported by the results of Lee (Citation2010), which state that the explicit teaching of subject-specific language enhances the meaning construction from geographical information (p. 84). This contributes to a more profound understanding of the complexity, interconnectedness and multi-layered notion of geography (Alexandre, Citation2009; Puttick & Cullinane, Citation2022).

Moreover, besides reading a text, a few publications conducted research on reading skills in combination with geography-specific discontinuous texts, such as reading a map (Adeyemi & Cishe, Citation2016; Falode et al., Citation2016; Richter et al., Citation2012; Słomska-Przech et al., Citation2021; Utami et al., Citation2018). In this regard, the findings of Utami et al. (Citation2018) indicate the interdependencies between language skills and the ability to decode maps: “students who have low literacy geography have difficulty in using map” (p. 1). The inextricable interrelations between language and content education become even more evident regarding the results of the studies that explicitly researched argumentation/reasoning, e.g. Chang (Citation2010), Engelen and Budke (Citation2021), Kerlin et al. (Citation2010), Pallant et al. (Citation2020), Ruhimat et al. (Citation2018) and Yoo et al. (Citation2020). The results of some of these studies imply increases in quality of written and spoken argumentation on geographical themes as a result of explicitly incorporating the structure of the Toulmin scheme (Engelen & Budke, Citation2021; Kerlin et al., Citation2010; Yoo et al., Citation2020). In particular, the notion of including geography-specific evidence, such as USGS data, and counterarguments resulted in more qualitative argumentation constructions. This further enhanced students’ geographical thinking, communication, development, and verbalization of their personal stances regarding spatial issues (Alexandre, Citation2009; Lane & Bourke, Citation2019).

Apart from the role of language in geography education research, our findings highlight the dominance of physical-geographical themes in this areas, as exemplified by twelve studies dealing with research on earth science classes (Adams, Citation2009; Chang, Citation2010; Chang et al., Citation2021; Kerlin et al., Citation2010; Lee, Citation2010; Nuryanti et al., Citation2019; Pallant et al., Citation2020; Pedretti, Citation2009; Polman & Pea, Citation2001; Thomas, Citation2017; Voss, Citation2011; Yoo et al., Citation2020). The physical geographical themes mentioned in the studies were mainly concerned with natural disasters, the water cycle, and astronomy. Surprisingly, human geographical themes were almost disregarded.

Overall, the key findings of this study indicate that the current research in geography education considers subject-specific language proficiency among primary and secondary learners as key to the degree of their access to and understanding of geographical information, especially considering how language and content are inextricably intertwined. Thus, geography teachers are responsible for the education of language in geographical content teaching.

However, there are at least three potential limitations concerning the results of this study. The first limitation concerns the inclusion of solely English empirical publications, which may have caused possible bias. Excluding all non-English articles may have contributed to overlooking research published in other languages. The second potential limitation is that the search conducted in this study was restricted only to peer-reviewed publications on three databases—Scopus, ProQuest, and Web of Science. Thus, we can assume that conducting further searches on other platforms, such as Google Scholar, would have resulted in locating non-peer-reviewed works, e.g. reports. However, due to the difficulties involved in systematically searching these, we limited our search to only peer-reviewed publications. Thirdly, the inclusion and exclusion of search terms, which surely contributed to selecting a specific set of resulting studies. We included explicit language skills that were previously inferred from the literature, rather than the language actions suggested by the Council of Europe (Citation2020). Therefore, studies researching language in geography education that have used terms other than those outlined in our search might have been overlooked.

6. Conclusion

Despite its limitations, this systematic review provides an essential overview of the empirical research conducted on language used in primary and secondary geography education. Students’ language capabilities in geography education are closely connected to a more holistic understanding of the world in terms of human-environment relations, which creates the basis for geographical thinking (Brooks, Citation2017). Thus, this systematic review makes a crucial contribution to the geography education research community by creating a basis for identifying progress, research desideratum, and future needs in the particular field. As suggested by Lambert (Citation2010), more innovation and progress in geography education including respective research is required to counteract bias of what empirical research is needed, e.g. on the role of language in geography education. In this regard, the present study is a necessary endeavor, as it is the first to provide a systematized overview based on a language- and content-based classification scheme.

The results of this study have several theoretical and practical implications. The language-related classification scheme significantly emphasizes a research desideratum, particularly at the spoken language level. Moreover, it encourages further research investigating the acquisition of subject-specific language at the word level. Furthermore, the subject-related classification scheme implemented in this study indicates that there is a research desideratum for geographical interventions based on human geographical themes. Additionally, subject-specific working methods are rarely at the center of the publications.

Finally, the present study enhances our understanding of the existing state of research in the field of language in primary and secondary geography education. In particular, it contributes to a growing body of evidence suggesting the increasing importance of the role of language in geography education research, highlighting that subject-specific language capabilities are key to students’ geography education and achievements. We hope that the current research will stimulate further investigation into this crucial area of study.

Disclosure statement

The authors report that there are no competing interests to declare.

Notes

1 According to the US National Science Education Standards, sciences are divided into “physical, life, and earth and space sciences.” The content standards of earth and space sciences commonly referred to as earth science are equivalent to the contents of physical geography. Thus, earth science is explicitly included in the search syntax.

References

- Abedi, J., Lord, C., & Plummer, J. R. (1997). Final report of language background as a variable in NAEP mathematics performance. National Center for Research on Evaluation, Standards, and Student Testing. https://cresst.org/wp-content/uploads/TECH429.pdf

- Adams, A. M. (2009). Utilizing a key word unraveling strategy to improve content comprehension in a high school agriculture earth science class (Publication Number 1471247) [Master’s thesis, University of California]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.

- Adeyemi, S. B., & Cishe, E. N. (2016). Effects of cooperative and individualistic learning strategies on students’ map reading and interpretation. Ghana Journal of Development Studies, 13(2), 154–175. https://dx.doi.org/10.4314/gjds.v13i2.9

- Aldobaikhi, H. (2016). Communication, interaction and collaboration by female Saudi secondary school students arising through asynchronous e-learning (Publication No. 10590309) [Doctoral dissertation, University of Southampton–Southampton]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global. https://eprints.soton.ac.uk/401236/

- Alexandre, F. (2009). Epistemological awareness and geographical education in Portugal: The practice of newly qualified teachers. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 18(4), 253–259. https://doi.org/10.1080/10382040903251067

- Alford, J., & Windeyer, A. (2014). Responding to national curriculum goals for English language learners Enhancing reading strategies in junior high school content areas. Journal of Immersion and Content-Based Language Education, 2(1), 74–95. https://doi.org/10.1075/jicb.2.1.04alf

- Bednarz, R., & Lee, J. (2019). What improves spatial thinking? Evidence from the Spatial Thinking Abilities Test. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 28(4), 262–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/10382046.2019.1626124

- Berendes, K., Vajjala, S., Meurers, D., Bryant, D., Wagner, W., Chinkina, M., & Trautwein, U. (2018). Reading demands in secondary school: Does the linguistic complexity of textbooks increase with grade level and the academic orientation of the school track? Journal of Educational Psychology, 110(4), 518–543. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000225

- Brennan, R. L., & Prediger, D. J. (1981). Coefficient kappa: Some uses, misuses, and alternatives. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 41(3), 687–699. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316448104100307

- Brooks, C. (2017). Understanding conceptual development in school geography. In M. Jones & D. Lambert (Eds.), Debates in geography education (2nd ed., pp. 103–114). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315562452

- Brown, B. A., & Ryoo, K. (2008). Teaching science as a language: A “content-first” approach to science teaching. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 45(5), 529–553. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.20255

- Budke, D. C. A., & Kuckuck, M. (2017). Sprache im Geographieunterricht. Waxmann Verlag. Retrieved from https://www.waxmann.com/index.php?eID=download&buchnr=3550

- Chang, C. C., Tsai, L. T., Chang, C. H., Chang, K. C., & Su, C. F. (2021). Effects of science reader belief and reading comprehension on high school students. Science Learning via Mobile Devices. Sustainability, 13(8), 4319. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084319

- Chang, C.-Y. (2010). Does problem solving = prior knowledge + reasoning skills in earth science? An exploratory study. Research in Science Education, 40(2), 103–116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-008-9102-0

- Cleary, A. (2019). A primary teacher’s exploration of the effects of formative assessment on teaching and learning [Master’s thesis, National University of Ireland, Maynooth, Ireland]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.

- Council of Europe. (2020). Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, teaching, assessment – Companion volume (978-92-871-8621-8). Retrieved from www.coe.int/lang-cefr

- Cresswell, T. (2008). Place: Encountering geography as philosophy. Geography, 93(3), 132–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/00167487.2008.12094234

- Creswell, J. W. (2002). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative (Vol. 7). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Dal, B. (2008). Assessing students’ acquisition of basic geographical knowledge. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 17(2), 114–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/10382040802148588

- Dalton-Puffer, C., & Smit, U. (2013). Content and language integrated learning: A research agenda. Language Teaching, 46(4), 545–559. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444813000256

- Davies, M., & Meissel, K. (2016). The use of Quality Talk to increase critical analytical speaking and writing of students in three secondary schools. British Educational Research Journal, 42(2), 342–365. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831218771303

- Delaney, E. J., & Hay, I. M. (1997). Worlds in our words: Geography as a second language. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 6(2), 124–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/10382046.1997.9965037

- Engelen, E., & Budke, A. (2021). Secondary school students’ development of arguments for complex geographical conflicts using the internet. Education Inquiry, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/20004508.2021.1966887

- Falode, O. C., Usman, H., Ilobeneke, S. C., Mohammed, H. A., Godwin, A. J., & Jimoh, M. A. (2016). Improving secondary school geography students’ positive attitude towards map reading through computer simulation instructional package in Bida, Niger State, Nigeria. Bulgarian Journal of Science and Education Policy, 10(1), 142–155. https://doi.org/10.29333/pr/8463.

- Fang, Z., Schleppegrell, M. J., & Cox, B. E. (2006). Understanding the language demands of schooling: Nouns in academic registers. Journal of Literacy Research, 38(3), 247–273. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15548430jlr3803_1

- Gallagher, F., & Leahy, A. (2019). From drowned drumlins to pyramid-shaped peaks: Analysing the linguistic landscape of geography to support English language learning in the mainstream classroom. Irish Educational Studies, 38(4), 435–450. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2019.1606727

- Gersmehl, P. (2014). Teaching geography (3rd ed.). Guilford Publications https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0064.2010.00329.x

- Halliday, M. A. (1999). The notion of “context” in language education. In M. Ghadessy (Ed.), Text and context in functional linguistics (pp. 1–24). John Benjamin Publishing Company. https://doi.org/10.1075/cilt.169.04hal

- Hinde, E. R., Popp, S. E. O., Jimenez-Silva, M., & Dorn, R. I. (2011). Linking geography to reading and English language learners’ achievement in US elementary and middle school classrooms. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 20(1), 47–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/10382046.2011.540102

- Holzer, M. A. (2016). Building bridges to climate literacy through the development of systems and spatial thinking skills (Publication No. 10291814) [Doctoral dissertation, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey–New Brunswick]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.

- Karasavvidis, I., Pieters, J. M., & Plomp, T. (2000). Investigating how secondary school students learn to solve correlational problems: Quantitative and qualitative discourse approaches to the development of self-regulation. Learning and Instruction, 10(3), 267–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-4752(99)00030-4

- Kerlin, S. C., McDonald, S. P., & Kelly, G. J. (2010). Complexity of secondary scientific data sources and students’ argumentative discourse. International Journal of Science Education, 32(9), 1207–1225. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500690902995632

- Kirk, R. M. (1995). Editorial: Geography as conversation? Journal of Geography in Higher Education 19(3), 269–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098269508709315

- Lambert, D. (2010). Geography education research and why it matters. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 19(2), 83–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/10382046.2010.482180

- Lambert, D. (2011). Reviewing the case for geography, and the ‘knowledge turn’ in the English National Curriculum. The Curriculum Journal, 22(2), 243–264. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585176.2011.574991

- Lambert, D., & Balderstone, D. (2012). Learning to teach geography in the secondary school: A companion to school experience. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315771274

- Lane, R., & Bourke, T. (2019). Assessment in geography education: A systematic review. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 28(1), 22–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/10382046.2017.1385348

- Lee, S. (2010). Vocabulary and content learning in grade earth science: Effects of vocabulary preteaching, rational cloze task, and reading comprehension task. The CATESOL Journal, 21, 75–102.

- Lee, V. G. (2006). Reading experiences of adolescent boys as they navigate the multiple discourses and social contexts of school, home, and rural community: An ethnographic case study (Publication No. 3281200) [Doctoral dissertation, University of Northern Colorado–Greeley]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.

- Lloyd, A. M. (2016). Place-based outdoor learning enriching curriculum: A case study in an Australian primary school (Publication No. 10633290) [Doctoral dissertation, Western Sydney University–Sydney]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.

- Morawski, M., & Budke, A. (2017). Learning with and by language: Bilingual teaching strategies for the monolingual language-aware geography classroom. The Geography Teacher, 14(2), 48–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/19338341.2017.1292939

- National Research Council. (1996). National science education standards. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/4962

- National Research Council. (2006). Learning to think spatially. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/11019

- Nikula, T. (2016). CLIL: A European approach to bilingual education. In N. Van Deusen-Scholl & S. May (Eds.), Second and foreign language education (pp. 1–14). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-02323-6_10-1

- Nuryanti, A., Kaniawati, I., & Suwarma, I. R. (2019). Junior high school students’ scientific literacy on earth science concept. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 1157(2), 022044. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1157/2/022044

- Nyoni, E., Manyike, T. V., & Lemmer, E. (2019). Difficulties in geography teaching and learning in the ESL classroom in Zimbabwe. Per Linguam-a Journal of Language Learning, 35(2), 74–87. https://doi.org/10.5785/35-2-810

- OECD. (2019). PISA 2018 results (Volume I). https://doi.org/10.1787/19963777

- Osborne, J., Erduran, S., & Simon, S. (2004). Enhancing the quality of argumentation in school science. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 41(10), 994–1020. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.20035

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 372, n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

- Pallant, A., Lee, H.-S., & Pryputniewicz, S. (2020). How to support secondary school students’ consideration of uncertainty in scientific argument writing: A case study of a high-adventure science curriculum module. Journal of Geoscience Education, 68(1), 8–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/10899995.2019.1622403

- Pedretti, G. (2009). The use of mental rehearsal strategies to develop high school Agriculture Earth Science students’ skills in reading and following laboratory assignment directions [Master’s thesis, University of California, Davis–Davis]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.

- Peukert, H., & Gogolin, I. (2017). Dynamics of linguistic diversity (Vol. 6). John Benjamins Publishing Company. https://doi.org/10.1075/hsld.6

- Polman, J. L., & Pea, R. D. (2001). Transformative communication as a cultural tool for guiding inquiry science. Science Education, 85(3), 223–238. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.1007

- Puttick, S., & Cullinane, A. (2022). Towards the nature of geography for geography education: An exploratory account, learning from work on the nature of science. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 46(3), 343–359. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098265.2021.1903844

- Rampersad, A., Shahiba, A., & Ali, N. (2020). Improving literacy in secondary school geography. Caribbean Curriculum, 27, 156–189.

- Reich, G. A. (2009). Testing historical knowledge: Standards, multiple-choice questions and student reasoning. Theory & Research in Social Education, 37(3), 325–360. https://doi.org/10.1080/00933104.2009.10473401

- Richter, D., Marin, F., & Decanini, M. M. S. (2012). The sketch maps as a language to analyze geographic reasoning. Procedia - Social and Behavoral Sciences, 46, 5183–5186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.06.405

- Riffel, A. D. (2015). An insight into a school’s readiness to implement a CAPS related indigenous knowledge curriculum for meteorological sciences. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 3(11), 906–916. https://doi.org/10.13189/ujer.2015.031117

- Rudsberg, K., & Öhman, J. (2015). The role of knowledge in participatory and pluralistic approaches to ESE. Environmental Education Research, 21(7), 955–974. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2014.971717

- Ruhimat, M., Ningrum, E., & Wijayanto, B. (2018). The implementation of problem based learning toward students’ reasoning ability and geography learning motivation. IOP Conference Series-Earth and Environmental Science, 1st Upi International Geography Seminar 2017, Bristol. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/145/1/012035

- Schleppegrell, M. J. (2004). The language of schooling: A functional linguistics perspective. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781410610317

- Seah, L. H., & Chan, K. K. H. (2021). A case study of a science teacher’s knowledge of students in relation to addressing the language demands of science. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 19(2), 267–287. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10763-019-10049-6

- See, B. H., Gorard, S., & Siddiqui, N. (2017). Can explicit teaching of knowledge improve reading attainment? An evaluation of the core knowledge curriculum. British Educational Research Journal, 43(2), 372–393. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3278

- Sejati, A. E., Amaluddin, L. O., Hidayati, D. N., Kasmiati, S., Sumarmi, & Ruja, I. N. (2017). The effect of outdoor study on the geography scientific paper writing ability to construct student character in senior high school. Advances in Social Science Education and Humanities Research, 100, 104–108. https://doi.org/10.2991/seadric-17.2017.22

- Słomska-Przech, K., Panecki, T., & Pokojski, W. (2021). Heat maps: Perfect maps for quick reading? Comparing usability of heat maps with different levels of generalization. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 10(8), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi10080562

- Snow, C. E., & Uccelli, P. (2009). The challenge of academic language. The Cambridge Handbook of Literacy, 112, 112–113. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511609664.008

- Sormunen, E., & Lehtio, L. (2011). Authoring wikipedia articles as an information literacy assignment: Copy-pasting or expressing new understanding in one’s own words? Information Research-an International Electronic Journal, 16(4), 503.

- Spires, H. A., Kerkhoff, S. N., Graham, A. C. K., Thompson, I., & Lee, J. K. (2018). Operationalizing and validating disciplinary literacy in secondary education. Reading and Writing, 31(6), 1401–1434. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-018-9839-4

- Suwono, H., Salmah, H., & Tenzer, A. (2020). Scientific literacy profile of science and non-science students in senior high schools in Malang. AIP Conference Proceedings, 2215(1), 070024.

- Symaco, L., & Brock, C. (2017). Space, place and scale in the study of education. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315652443

- Taylor, C. (2009). Towards a geography of education. Oxford Review of Education, 35(5), 651–669.

- Thomas, D. B. (2017). Using the multimedia strategies of learner-generated drawing and peer discussion to retain terminology in secondary education science classrooms (Publication No. 10618195) [Doctoral dissertation, The University of North Carolina at Charlotte–Charlotte] ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.

- Toulmin, S. E. (2003). The uses of argument. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511840005

- Utami, W. S., Zain, I. M., & Sumarmi. (2018). Geography literacy can develop Geography skills for high school students: Is it true? IOP Conf. Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 296, 1–6. doi:10.1088/1757-899X/296/1/012032

- Voss, S. M. (2011). The affordances of multimodal texts and their impact on the reading process (Publication No. 3490686) [Doctoral dissertation, University of Minnesota–Minnesota]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.

- Ward-Washington, R. R. (2001). The effectiveness of instruction in using reading comprehension strategies with eleventh-grade social studies students (Publication No. 3040621) [Doctoral dissertation, The University of Mississippi–Mississippi]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.

- Wardenga, U. (2002). Alte und neue Raumkonzepte für den Geographieunterricht. Geographie heute, 23(200), 8–11.

- Weiss, G. (2020). The social-constructivist concept of space in a German geography education context: Status-quo and potential. Review of International Geographical Education Online, 10(4), 684–705. https://doi.org/10.33403/rigeo.781489

- Yoo, B. H., Kwak, Y., & Park, W. M. (2020). Analysis of argumentation structure in students’ writing on socio-scientific issues (SSI): Focusing on the unit of climate change in high school earth science I. Journal of the Korean Earth Science Society, 41(4), 405–414. https://doi.org/10.5467/JKESS.2020.41.4.405