Abstract

Understanding climate change concern among adolescents is considered a useful strategy for building public engagement with climate change. However, the psychological and sociodemographic antecedents of climate change concern have been studied mainly with Western adults. We used structural equation modeling (SEM) to gain insights into the factors predicting climate change concern among adolescents in Cambodia to be used to support the planning of climate related education. The results of a survey with students in grades 7–9 (N = 389) show that ecological worldview—or belief in an ecocrisis—is the strongest predictor of climate change concern among Cambodian adolescents. Altruistic environmental concern is associated with the strength of the ecological worldview. Building understanding of the human impact on climate and reflection on altruistic motives for environmental action may be good focal points for climate change education in Cambodia, however more research is needed to better understand climate change concern and its individual and cultural predictors in Cambodia and elsewhere outside the West.

Introduction

Human-caused climate change is a threat to the functioning of ecosystems and thereby to human well-being and survival (IPCC, 2022). The impacts of climate change are particularly strong on people in the Global South, who depend on climate-sensitive livelihoods and whose ability to adapt to changes is limited (Eckstein et al., Citation2021), as well as on young people who will live with the consequences of climate change throughout their adult life (Corner et al., Citation2015). Researchers and governments around the world have called on education, that can increase peoples’ awareness of climate change and engagement in its mitigation (Evans & Luo, Citation1990; Hermans & Korhonen, Citation2017; Özdem et al., Citation2014).

In climate change education, an effective choice can be to focus on climate-related concern and understanding its underlying factors. According to several studies, subjective concern is significantly related to environmental behavior. Overall, it is known that affective factors are often more strongly related to behavior than cognitive factors (e.g. knowledge and understanding) (Hermans & Korhonen, Citation2017; van der Linden, Citation2017). Concern related to climate change predicts an individual’s commitment to climate change mitigation and adaptation, and therefore understanding young people’s climate change concern has been suggested as “a key strategy for building a citizenry that supports climate change action” (Stevenson et al., Citation2019, p. 1). However, previous research has demonstrated that considerable cross-cultural variation in the level of collective climate-related concern exists. The factors underlying this concern among children and adolescents living in non-Western countries are poorly understood (Corner et al., Citation2015; Salehi et al., Citation2016).

Education supporting climate literacy and engagement among adolescents should be designed with the intended audience in mind (García Vinuesa et al., Citation2022; Lieske et al., Citation2014). It is known, for example, that gender, age, living area, and parental education influence the nature and level of general environmental concern and, more specifically, climate-related concern among young people (Chawla & Cushing, Citation2007; Corner et al., Citation2015). It is also well documented that, in addition to demographic factors, climate change concern is strongly influenced by many individual-level factors, such as existing knowledge, personal values, and worldviews (Corner et al., Citation2015). In addition, climate-related predictors are distinctive and specific to each nation (Lee et al., Citation2015). Therefore, understanding the interplay between sociodemographic variables, so-called psychometric variables (e.g. knowledge, values, and worldviews), and climate change concern can help design climate change education so that it best supports climate engagement among different target groups and in different cultural contexts (Corner et al., Citation2015; Schultz et al., Citation2005). Climate change-related concern or its antecedents among Cambodian adolescents have not been studied.

Climate change concern and factors associated with it

In environmental psychology, concern can also be referred to as “worry,” “perceived risk,” or “perceived seriousness” and these terms may have slightly different meanings in different studies (Sundblad et al., Citation2007; van der Linden, Citation2014). In this research, climate change concern refers to feelings of concern and worry (van der Linden, Citation2017). Adolescents’ climate change concern is known to be linked with self-reported climate change mitigation behaviors (Stevenson et al., Citation2018; Stevenson & Peterson, Citation2015).

The demographic patterns determining climate change-related concern seem to diverge greatly between English-speaking Western democracies–where most studies have been conducted–and the rest of the world (Lewis et al., Citation2019). Gender is probably one of the most studied demographic predictors of climate change concern, and girls and young women have consistently been found to express more concern about climate change than boys and young men (Boyes et al., Citation2014; Corner et al., Citation2015; Stevenson & Peterson, Citation2015). However, when cross-national studies are compared with studies focused on the West, the gender effect between adult males and females has been found to be much smaller in non-Western countries (Hornsey et al., Citation2016; Lewis et al., Citation2019).

Age or grade are commonly found to affect environmental concern and consciousness. Young people are, in general, equally, or more interested in and concerned about climate change than older people (Corner et al., Citation2015). It is also known that adolescents’ environmental attitudes and engagement tend to dip in adolescence, however they usually recover in young adulthood (e.g. Olsson & Gericke, Citation2016). Other socio-demographic factors, such as a living area that has a higher probability of climate-related impacts (e.g. floods) or parents’ higher education level, are sometimes associated with children’s higher levels of general environmental concern or climate-related concern (Bichard & Kazmierczak, Citation2012; Tranter & Skrbis, Citation2014).

Environmental psychologists have found that an individual’s environmental concerns may stem from an awareness or belief that harming nature has detrimental effects on the objects of their valuations; whether egoistic, biospheric, or altruistic valuations (Schultz, Citation2001; Stern et al., Citation1999). Biospheric value orientations refer to concern toward other species and ecosystems, and altruistic value orientations refer to concern toward the wider community of people outside the self and family. Both these value orientations—either biospheric orientation alone or together with altruistic orientation—have been found to be positively associated with concern for and engagement with climate change in adults in different cultures (Shi et al., Citation2016; van der Linden, Citation2015). Environmental concern based on biospheric values has also been found to be strongly associated with ecological worldviews in adolescents in Slovenia (Torkar et al., Citation2021).

Worldviews can be considered constructs that describe people’s conscious beliefs about the world as a function of their value priorities (Rohan, Citation2000). Worldviews are an important link between an individual’s values and their decisions (Rohan, Citation2000). Ecological worldview, which is often measured using the New Ecological Paradigm (NEP) scale (Dunlap, Citation2008; Dunlap et al., Citation2000), is usually positively associated with climate-related concern among adults (Kellstedt et al., Citation2008; Milfont, Citation2012; Xue et al., Citation2018). However, we found no studies examining this association among adolescents.

Knowledge is likely a necessary, yet not a sufficient condition for climate change concern (van der Linden, Citation2017). In studies with adolescents, climate change knowledge has been positively linked with climate change concern (Boyes et al., Citation2014; Stevenson et al., Citation2014). However, research with adults has discovered that the association between scientific or climate knowledge and climate-related concern is not straightforward, and it can depend on, for instance, worldviews (Shi et al., Citation2015).

As no studies exist regarding Cambodian adolescents’ climate change concern, the aim of this study is thus to determine how the above-mentioned sociodemographic and psychometric factors interplay and whether they can predict climate change concern among Cambodian adolescents. Our purpose is to enrich understanding of the factors underlying climate change concern and support the development of more effective climate education and communication activities in Cambodia.

Materials and methods

Research context

Cambodia is a country facing a high risk of weather-related disasters—especially floods, storms, and droughts—and the survival and adaptive capacity of Cambodians is weak because of poverty and agricultural dependence (UNDRR, 2019). Almost one-third of Cambodia’s 16 million people are 14 years or younger (World Bank, Citation2020).

Participants and procedure

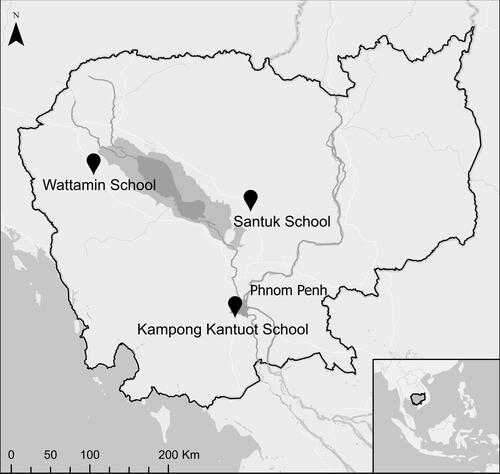

A survey was conducted in four Cambodian public schools in 2014–2015. Permission was sought from the principals of each school and all the participating students were informed that participation was voluntary. First, a pilot study was carried out in December 2014 in O’dambang I secondary school in Battambang Province. Here, 23 students completed a survey translated in Khmer. After this, three group interviews were conducted with 11 students from grades 7, 8, and 9. Based on the pilot study, those survey items that appeared confusing for the students were modified (see the description of the final survey measures in ). The actual, modified survey in Khmer was targeted at students in grades 7, 8, and 9 in three public schools located in different parts of Cambodia: Battambang Province (Wattamim school), Kandal Province (Kompong Kantuot school), and Kampong Thom Province (Santuk school) (see ). A convenience sampling was used: it was based on the study sites’ different levels of vulnerability to flooding. One of our study sites, Kandal, is more prone to flooding than other study sites, and yet another study site, Battambang, experienced extensive floods and subsequent crop damage 16 months prior to data collection (Cambodia Humanitarian Response Forum, Citation2013; National Committee for Disaster Management, Citation2003). Furthermore, we had access to these schools via teachers and/or local NGO workers. To reduce the possibility for a possible sampling error caused by non-random sampling, all study sites were situated in public schools in different parts of the country.

Table 2. Correlations between model constructs in the preliminary model.

The survey was based on self-reporting and the question concerning knowledge about climate change was based on self-assessment. This approach has both advantages and disadvantages. Surveys based on self-reports are more feasible to carry out compared to interviews and observations. On the other hand, self-reports and self-assessments often lead to different types of measurement error. These include, for example, inaccurate responses due to problems of understanding questions or response scales, students’ unrealistic optimism about their own abilities, information deficits or neglection, or socially desirable responding. Thus, the results of self-reports should be treated with caution (Baumgartner & Steenkamp, Citation2006; Brown et al., Citation2015).

Of the participants, 29% were from Wattamim school, 33% from Kompong Kantuot school, and 38% from Santuk school. The age of the respondents varied from 11 to 16 (median age was 15), and 69% identified as female and 31% as male. The students’ parents worked primarily in agriculture, fishing, or craft-related occupations.

Out of a total of 407 respondents, 389 valid questionnaires were included in the analysis. The survey took about 20 min to complete.

Measures

The socio-demographic measures used in the analysis were gender and grade. We also used living area, age, and parents’ educational levels as covariates. The psychological measures used are described below. The scales of all variables and the modifications made to some of the variables are presented in .

Table 1. Variable measurement scales and items.

Environmental concern

Schultz’s (Citation2001) Environmental motives scale (EMS) is based on the idea that an individual’s environmental concerns may stem from an awareness or belief that harming nature has detrimental effects on the objects of their egoistic valuations, biospheric valuations, or altruistic valuations. In other words, environmental concerns are based on egoistic, biospheric or altruistic values. In this study, we used the environmental motives scale adapted for children (ChEMS) as an indicator of general environmental concern (Bruni et al., Citation2012).

Ecological worldview

The new ecological paradigm scale, or the NEP scale by Dunlap and colleagues (Dunlap, Citation2008; Dunlap et al., Citation2000), is one of the most popular constructs of environmental worldviews. The NEP scale was constructed to tap into the five hypothesized facets of an ecological worldview: the reality of limits to growth, anti-anthropocentrism, the fragility of nature’s balance, rejection of exemptionalism, and the possibility of an ecocrisis. The children’s version of the NEP scale (NEP for Children scale or NEP-C), used in this study, measures three dimensions: rights of nature, ecocrisis, and human exemptionalism (Manoli et al., Citation2007).

Self-assessed knowledge of climate change

A self-assessment of the level of climate change knowledge was used in this study.

In their extensive review, Gifford and Nilsson (Citation2014) found that knowledge—even self-reported knowledge—is one of the main predictors of general environmental concern (and behavior) (see also Lyons & Breakwell, Citation1994; Milfont, Citation2012). However, in a study by Kellstedt et al. (Citation2008), climate-related knowledge was not associated with concern.

Climate change concern

In this study, climate change concern was understood as an affective orientation based on environmental values (i.e. level of worry about climate change) (Stevenson et al., Citation2018). This definition is consistent with the ChEMS scale (Bruni et al., Citation2012; Schultz, Citation2001). The level of climate change concern was measured using self-assessment.

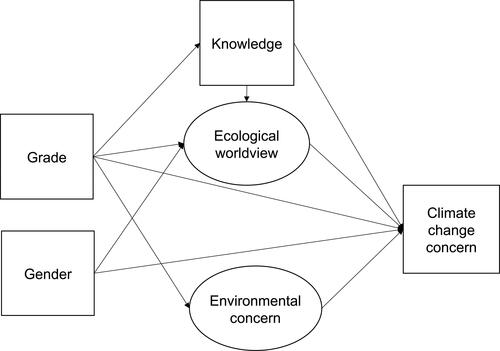

Based on the above literature, we propose the following hypotheses: Grade level is associated with climate change concern so that the higher the grade is, the lower the level of concern (H1). This association is partly mediated by higher self-assessed knowledge, stronger ecological worldview, and higher biospheric and altruistic general environmental concern (H2). Furthermore, the female gender is positively associated with higher climate change concern (H3), and this association is partly mediated by a stronger ecological worldview (H4).

Based on these hypotheses, we constructed a hypothetical path model (), which we then tested using SEM analysis (see Analyses below).

Analyses

Preliminary analyses and reliability calculations (Cronbach’s alpha) were conducted using SPSS version 25. The theoretical model was tested using a SEM constructed with Mplus8 (Muthén & Muthén, Citation1998). SEM was chosen for performing the actual analysis because of the method’s advantages in behavioral research: SEM provides flexibility to model relationships among multiple predictors and criterion variables simultaneously while constructing unobservable latent variables.

Regarding normality, the univariate distributions of the study variables were within a reasonable range (skewness ± 1.5, kurtosis ± 1.5) (Curran et al., Citation1996). Thus, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and SEM analyses were conducted using a maximum likelihood (ML) estimation. The internal consistencies of the scales (Cronbach’s alpha) used were 0.70. To evaluate the fit of the hypothesized model, four commonly recommended fit indices were used: the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI), the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR). Adequate fit has been defined as CFI > 0.9, TLI > 0.9, RMSEA < 0.08, and SRMR < 0.08 (Byrne, Citation2013).

When constructing the SEM (Byrne, Citation2013), a two-step analysis was performed. The first step was to specify a measurement model whereby the unmeasured latent variables (NEP-C and ChEMS) were scaled onto their related observed indicator variables. Regarding the NEP-C scale, only four items (5, 6, 8, and 10) of the original 10-item scale performed the required latent construct, forming a one-factor solution. The items were: “When people mess with nature, it has bad results,” “Nature is strong enough to handle the bad effects caused by the way we live,” “People are treating nature badly,” and “If things don’t change, we will have a big disaster in the environment soon.” Thus, the items performed quite differently than in the original NEP-C scale (Manoli et al., Citation2007), and they mostly represented the “Ecocrisis” dimension of the NEP-C. The resulting four-item factor structure showed a strong model fit (Cronbach’s alpha .70, CFI > 0.996, TLI > 0.988, RMSEA < 0.033, and SRMR < 0.017, p > .05.)

The original three-factor solution of the ChEMS, including an “egoistic,” “altruistic,” and “biospheric” dimension, showed no acceptable model fit. A two-dimensional factor solution, including the “altruistic” and “biospheric” dimensions, showed an acceptable fit. The correlations between the factors in the preliminary model are presented in .

The final model diagram, however, included only the “altruistic” dimension, showing a strong model fit (the reliability alpha coefficient = 0.70, CFI > 0.991, TLI > 0.974, RMSEA < .032, and SRMR < .026 (p > .05). The “altruistic” items included in the final model were “My friends,” “Other children than me and my friends,” “Other Cambodian people,” and “People in other countries.” The descriptive measurements, reliability coefficients, and factor loadings for the latent variable scales in the final model are presented in .

Table 3. Measure descriptive, reliability, and CFA statistics of the latent variables.

In the second step of the SEM, regression structures among the latent variables were specified, and the relationships between the latent constructs and the observed variables and covariates were drawn. The hypothesized model served as the baseline against which other alternatively nested models were compared in assessing the evidence of construct and discriminant validity. To test whether the indirect paths from grade and gender had a significant effect on climate change concern, we performed bootstrapping (bootstrap = 2000) and estimated mediator effects using confidence intervals (CIs) constructed around the estimates (Hayes, Citation2017).

Results

Descriptive results

The majority (82%) of Cambodian adolescents agreed or strongly agreed with the statement “I am concerned about climate change” (mean = 4.01, SD = 0.89). However, they were quite uncertain of the meaning of the term “climate change.” Only 29% agreed or strongly agreed with the statement “I know what climate change means” (mean = 3.30, SD = 0.830), and 23% of the respondents chose the “I don’t understand” answer option.

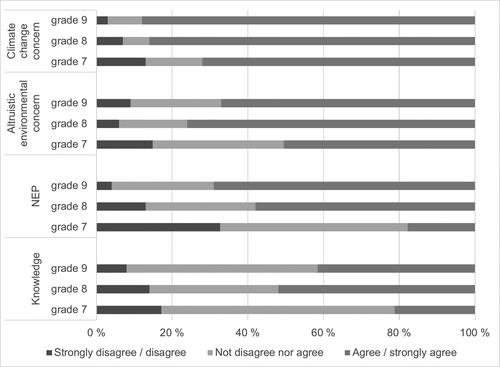

Self-assessed level of knowledge (p < .001) and the level of altruistic environmental concern (p = .037) were the highest on grade 8 (). Contrary to our expectations, ecological worldviews and climate change concern were the highest on grade 9 (p < .001). Thus, Hypothesis 1 was not supported.

Model results

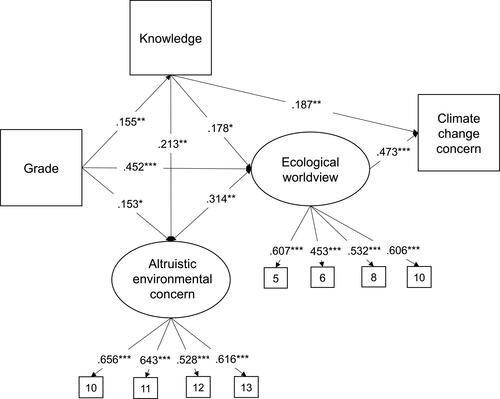

shows the final model with statistically significant effects, which are based on a strong fit of the model to the data: CFI > 0.976, TLI > 0.963, RMSEA < 0.034, and SRMR < 0.032 [χ2 = 52.582 (36), p < .05]. Gender, egoistic environmental concern, and biospheric environmental concern, which were included in the theoretical model, were excluded from the final model because of poor model fit. The same applied to the covariates living area and parents’ levels of education. Hypotheses 3 and 4 were thus not supported.

Figure 4. Factors affecting Cambodian upper secondary school students’ climate change concern. Note: *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

The final model explained the variation in Cambodian adolescents’ climate change concern relatively well (R2 = 0.295) (Cohen, Citation2013). The variances in adolescents’ ecological worldview (R2 = 0.261) and altruistic environmental concern (R2 = 0.079) were also significantly explained by the identified model. Grade level significantly predicted knowledge of climate change, ecological worldview, and altruistic environmental concern.

Furthermore, higher self-assessed knowledge predicted higher climate change concern, stronger ecological worldview, and higher altruistic environmental concern, even though these effects were relatively low. According to our model, the strongest predictor of adolescents’ climate change concern was their ecological worldview: the stronger the ecological worldview, the higher the climate change concern.

No direct association was found between grade level and climate change concern. However, a statistically significant indirect path with confidence intervals was observed from grade level to climate change concern mediated by ecological worldview. Thus, Hypothesis 2 was partly supported. The indirect paths, effects, and confidence intervals are presented in .

Table 4. Indirect paths and effects from grade level to climate change concern (standardized coefficients).

Discussion

The aim of the current study was to gain understanding of the factors underlying Cambodian adolescents’ climate change concern so that they could be used to support the planning of climate related education in Cambodia. The study is the first one examining the antecedents of adolescents’ climate change concern in Cambodia, and one of the few papers in IRGEE to address learners’ climate change concern in Southeast Asia (Boyes et al., Citation2014). According to our results, the strongest predictor of Cambodian adolescents’ climate change concern is their ecological worldview, or belief in an ecocrisis, which is stronger on higher grade levels.

Some caution is needed when interpreting this result. In our study, the NEP-C scale performed differently than expected. The final version of the NEP-C scale measures mainly one “facet” of ecological worldview: belief in the existence of an ecocrisis (Dunlap et al., Citation2000). A reason for the weak performance of the original scale may be related to the study participants’ confusion with some of the scale items, caused by the questionnaire’s lack of clarity or the participants’ lack of knowledge. For instance, the number of missing responses regarding the item “There are too many (or almost too many) people on earth” indicates that the item was confusing for the participants. Confusion has also been reported in studies with Chinese and Dutch children (Kopnina, Citation2011; Wu, Citation2012), which means that the content of this item may be too difficult for adolescents to understand (Rosa et al., Citation2022).

Another reason for the weak performance of the NEP-C scale may be culturally based and related to Cambodian adolescents’ general perception of the human–nature relationship, which is different from the general Western perception. For example, our pilot interviews indicated that young Cambodians associated positive meanings with the word “control,” which contradicts the original idea of the NEP (Dunlap et al., Citation2000; Manoli et al., Citation2007). Other studies have shown that people with Asian backgrounds generally place less weight on biospheric environmental concerns and more weight on anthropocentric concerns compared to people with Western backgrounds (Milfont et al., Citation2006; Watson & Halse, Citation2005). Furthermore, the division between nature and culture is generally not as strong in Asia as in the West (Aoyagi-Usui et al., Citation2003; Ironside, Citation2015; Wu, Citation2012). Wu (Citation2012) noted that the ecocrisis facet of the NEP is commonly supported in studies across different cultures.

Likewise, the low importance of biospheric concerns may be a reason why these concerns were not associated with Cambodian adolescents’ environmental worldview or climate change concern in the final model. The results are partly inconsistent with studies conducted outside Asia, in which both biospheric and altruistic values/environmental concerns have been associated with concerns about climate change (Shi et al., Citation2016; van der Linden, Citation2015). We think that in addition to biospheric and altruistic environmental concerns, it could be useful to study the impact of so-called relational, non-dichotomous values on environmental concerns in Cambodia and other Southeast Asian countries (Chan et al., Citation2016). Thus, new ways of understanding the antecedents of environmental and climate concerns in these cultures might be recognized.

Our results indicate that adolescents’ self-assessed level of climate change knowledge is associated with their climate change concern. In this study knowledge was assessed using a single-item measurement, which can reduce its validity and reliability (Bergkvist & Rossiter, Citation2007). Due to this and because increasing the level of public knowledge of climate change forms the basis of most climate change education activities, it would be good if future studies used an objective, multiple-item knowledge measure. More detailed information about students’ climate knowledge would also help in planning the contents of climate education, as it is known that secondary school students’ understanding of climate change is often incomplete and partially incorrect (Chang & Pascua, Citation2016).

Unlike in previous studies from Belgium (Meeusen, Citation2014), China (Shen & Saijo, Citation2008), and Australia (Tranter & Skrbis, Citation2014), Cambodian adolescents’ gender, living area or their parents’ levels of education were not associated with the adolescents’ climate change concern. The gender effect on environmental concern is generally high in the West, but smaller outside Western countries, which may explain the result (Hornsey et al., Citation2016; Lewis et al., Citation2019). Some studies have found that living in areas prone to flooding predict higher climate change concerns (Bichard & Kazmierczak, Citation2012). However, the prerequisite for this is that the people living in the area understand that the increase in floods is causally connected to climate change, which is not necessarily true in this study.

Educational implications and conclusions

Personal concern or worry is an emotional state that often leads to action, such as climate change mitigation or adaptation, aimed at reducing the threat causing the emotion (Stevenson et al., Citation2019; van der Linden, Citation2017). The results of this study indicate that knowledge may be relevant to Cambodian adolescents’ level of climate change concern. Furthermore, a belief in an ecocrisis seems to increase adolescents’ climate change concern. Therefore, it is important that education on climate change provides students with a broad-based knowledge (Chang & Pascua, Citation2016), that addresses the negative effects of human activity on climate.

This study supports the idea that the antecedents of climate change concern are culture specific (García Vinuesa et al., Citation2022; Salehi et al., Citation2016). In Cambodia, climate change issues can be addressed from the viewpoint of altruistic motives, as they seem to resonate with Cambodian adolescents. In education, knowledge of the causes of climate change can be linked to practical and moral reflection on how climate change affects different groups of people and on individuals’ moral responsibilities for the environment and thereby for other people. However, it is important that individual adolescents need not feel that they carry too big a burden of responsibility for climate action. The responsibility of societal and political actors in protecting the environment and climate needs to be emphasized (Ojala, Citation2012). In addition, climate and environmental issues can be addressed from the perspective of relational values, because a strict separation between biospheric and altruistic values does not necessarily support Cambodian conception of human-nature relationship.

It is important to note, that concern does not always lead to positive action. Strong feelings of concern or worry can also cause pessimism, which hinders students’ learning and competence to act. Therefore, it is important that teachers support students’ proactive coping strategies, self-efficacy, and agency experiences, so that the students’ concern can be channeled into action instead of withdrawal or denial (Ojala, Citation2012).

Further research, both broad-based and in-depth studies, are needed to better understand the structure of Cambodian adolescents’ climate related knowledge and concern as well as worldviews related to the environment and the human-nature relationship.

Acknowledgments

Our sincere gratitude to Bunyeth Chan, Ret Thaung, Sreykol Tam, Sarak Chheang, Khim Phearum, Nick Souter, and Puthi Komar Organization for their valuable assistance with the field work, Eero Laakkonen for helpful advice with the analysis, and the Kone Foundation for support in this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available because they contain information that may compromise the research participants’ privacy/consent.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aoyagi-Usui, M., Vinken, H., & Kuribayashi, A. (2003). Pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors: An international comparison. Human Ecology Review, 10(1), 23–31.

- Baumgartner, H., & Steenkamp, J. B. E. (2006). Response biases. In The handbook of marketing research: Uses, misuses, and future advances (p. 95). SAGE: Thousand Oaks, California.

- Berkvens, J. B. (2017). The importance of understanding culture when improving education: Learning from Cambodia. International Education Studies, 10(9), 161–174.

- Bergkvist, L., & Rossiter, J. R. (2007). The predictive validity of multiple-item versus single-item measures of the same constructs. Journal of Marketing Research, 44(2), 175–184. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.44.2.175

- Bichard, E., & Kazmierczak, A. (2012). Are homeowners willing to adapt to and mitigate the effects of climate change? Climatic Change, 112(3–4), 633–654. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-011-0257-8

- Boyes, E., Stanisstreet, M., Skamp, K., Rodriguez, M., Malandrakis, G., Fortner, R. W., Kilinc, A., Taylor, N., Chhokar, K., Dua, S., Ambusaidi, A., Cheong, I. P-A., Kim, M., & Yoon, H. G. (2014). An international study of the propensity of students to limit their use of private transport in light of their understanding of the causes of global warming. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 23(2), 142–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/10382046.2014.891425

- Brown, G. T., Andrade, H. L., & Chen, F. (2015). Accuracy in student self-assessment: Directions and cautions for research. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 22(4), 444–457. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2014.996523

- Bruni, C. M., Chance, R. C., & Schultz, P. W. (2012). Measuring values-based environmental concerns in children: An environmental motives scale. The Journal of Environmental Education, 43(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.2011.583945

- Byrne, B. M. (2013). Structural equation modeling with Mplus: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Routledge.

- Cambodia Humanitarian Response Forum (2013). Cambodia: Floods. Humanitarian Response Forum (HRF) Situation Report No 06. Retrieved March 7, 2022, from https://reliefweb.int/report/cambodia/floods-humanitarian-response-forum-hrf-situation-report-no-06-08-november-2013

- Chan, K. M. A., Balvanera, P., Benessaiah, K., Chapman, M., Díaz, S., Gómez-Baggethun, E., Gould, R., Hannahs, N., Jax, K., Klain, S., Luck, G. W., Martín-López, B., Muraca, B., Norton, B., Ott, K., Pascual, U., Satterfield, T., Tadaki, M., Taggart, J., & Turner, N. (2016). Why protect nature? Rethinking values and the environment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 113(6), 1462–1465. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1525002113

- Chang, C. H., & Pascua, L. (2016). Singapore students’ misconceptions of climate change. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 25(1), 84–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/10382046.2015.1106206

- Chawla, L., & Cushing, D. F. (2007). Education for strategic environmental behavior. Environmental Education Research, 13(4), 437–452. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620701581539

- Cohen, J. (2013). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge.

- Corner, A., Roberts, O., Chiari, S., Völler, S., Mayrhuber, E. S., Mandl, S., & Monson, K. (2015). How do young people engage with climate change? The role of knowledge, values, message framing, and trusted communicators. WIREs Climate Change, 6(5), 523–534. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.353

- Curran, P. J., West, S. G., & Finch, J. F. (1996). The robustness of test statistics to nonnormality and specification error in confirmatory factor analysis. Psychological Methods, 1(1), 16.

- Dunlap, R. E. (2008). The New Environmental Paradigm Scale: From marginality to worldwide use. The Journal of Environmental Education, 40(1), 3–18. https://doi.org/10.3200/JOEE.40.1.3-18

- Dunlap, R. E. V. L., Liere, K. V., Mertig, A., & Jones, R. E. (2000). Measuring endorsement of the new ecological paradigm: A revised NEP scale. Journal of Social Issues, 56(3), 425–442. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-4537.00176

- Eckstein, D., Künzel, V., & Schäfer, L. (2021). Global climate risk index 2021. Who suffers most from extreme weather events 2000–2019. Briefing paper, Germanwatch.

- Evans, G., & Luo, J. (1990). Public education and information mechanisms. In IPCC, climate change. The IPCC response strategies. Report prepared for Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change by Working Group III, IPCC/World Meteorological Organization/United Nations Environment Program. (p. 330).

- García Vinuesa, A., Rui Mucova, S. A., Azeiteiro, U. M., Meira Cartea, P. Á., & Pereira, M. (2022). Mozambican students’ knowledge and perceptions about climate change: An exploratory study in Pemba City. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 31(1), 5–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/10382046.2020.1863671

- Gifford, R., & Nilsson, A. (2014). Personal and social factors that influence pro‐environmental concern and behaviour: A review. International Journal of Psychology, 49(3), 141–157. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12034

- Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Publications.

- Hermans, M., & Korhonen, J. (2017). Ninth graders and climate change: Attitudes towards consequences, views on mitigation, and predictors of willingness to act. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 26(3), 223–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/10382046.2017.1330035

- Hornsey, M. J., Harris, E. A., Bain, P. G., & Fielding, K. S. (2016). Meta-analyses of the determinants and outcomes of belief in climate change. Nature Climate Change, 6(6), 622–626.

- IPCC (2022). Summary for policymakers. In H.-O. Pörtner, D. C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E. S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, & B. Rama (Eds.), Climate change 2022: Impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the sixth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (pp. 3–33). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009325844.001

- Ironside, J. (Ed.). (2015). What about the ‘unprotected’ areas? Building on traditional forms of ownership and land use for dealing with new contexts. In Conservation and development in Cambodia (pp. 221–242). Routledge.

- Kellstedt, P. M., Zahran, S., & Vedlitz, A. (2008). Personal efficacy, the information environment, and attitudes toward global warming and climate change in the United States. Risk Analysis, 28(1), 113–126. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.2008.01010.x

- Kopnina, H. (2011). Qualitative revision of the New Ecological Paradigm (NEP) Scale for children. International Journal of Environmental Research, 5, 1025–1034.

- Lee, T. M., Markowitz, E. M., Howe, P. D., Ko, C. Y., & Leiserowitz, A. A. (2015). Predictors of public climate change awareness and risk perception around the world. Nature Climate Change, 5(11), 1014–1020. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2728

- Lewis, G. B., Palm, R., & Feng, B. (2019). Cross-national variation in determinants of climate change concern. Environmental Politics, 28(5), 793–821. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2018.1512261

- Lieske, D. J., Wade, T., & Roness, L. A. (2014). Climate change awareness and strategies for communicating the risk of coastal flooding: A Canadian maritime case example. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 140, 83–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecss.2013.04.017

- Lyons, E., & Breakwell, G. M. (1994). Factors predicting environmental concern and indifference in 13- to 16-year-olds. Environment and Behavior, 26(2), 223–238. https://doi.org/10.1177/001391659402600205

- Manoli, C. C., Johnson, B., & Dunlap, R. E. (2007). Assessing children’s environmental worldviews: Modifying and validating the New Ecological Paradigm Scale for use with children. The Journal of Environmental Education, 38(4), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.3200/JOEE.38.4.3-13

- Meeusen, C. (2014). The intergenerational transmission of environmental concern: The influence of parents and communication patterns within the family. The Journal of Environmental Education, 45(2), 77–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.2013.846290

- Milfont, T. L. (2012). The interplay between knowledge, perceived efficacy, and concern about global warming and climate change: A one‐year longitudinal study. Risk Analysis, 32(6), 1003–1020. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.2012.01800.x

- Milfont, T. L., Duckitt, J., & Cameron, L. D. (2006). A cross-cultural study of environmental motive concerns and their implications for proenvironmental behavior. Environment and Behavior, 38(6), 745–767. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916505285933

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998). Mplus [computer software].

- National Committee for Disaster Management (2003). Mapping vulnerability to natural disasters in Cambodia. Royal Government of Cambodia and United Nations World Food Programme. Retrieved February 18, 2022, from https://documents.wfp.org/stellent/groups/public/documents/ena/wfp034529.pdf

- Ojala, M. (2012). Regulating worry, promoting hope: How do children, adolescents, and young adults cope with climate change? International Journal of Environmental and Science Education, 7(4), 537–561.

- Olsson, D., & Gericke, N. (2016). The adolescent dip in students’ sustainability consciousness—Implications for education for sustainable development. The Journal of Environmental Education, 47(1), 35–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.2015.1075464

- Özdem, Y., Dal, B., Öztürk, N., Sönmez, D., & Alper, U. (2014). What is that thing called climate change? An investigation into the understanding of climate change by seventh-grade students. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 23(4), 294–313. https://doi.org/10.1080/10382046.2014.946323

- Rohan, M. J. (2000). A rose by any name? The values construct. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 4(3), 255–277. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327957PSPR0403_4

- Rosa, C. D., Collado, S., & Larson, L. R. (2022). The utility and limitations of the New Ecological Paradigm Scale for children. The Journal of Environmental Education, 53(2), 87–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.2022.2044281

- Salehi, S., Nejad, Z. P., Mahmoudi, H., & Burkart, S. (2016). Knowledge of global climate change: View of Iranian university students. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 25(3), 226–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/10382046.2016.1155322

- Schultz, P. W., Gouveia, V. V., Cameron, L. D., Tankha, G., Schmuck, P., & Franěk, M. (2005). Values and their relationship to environmental concern and conservation behavior. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 36(4), 457–475. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022105275962

- Schultz, P. W. (2001). The structure of environmental concern: Concern for self, other people, and the biosphere. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 21(4), 327–339.

- Shen, J., & Saijo, T. (2008). Reexamining the relations between socio-demographic characteristics and individual environmental concern: Evidence from Shanghai data. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 28(1), 42–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2007.10.003

- Shi, J., Visschers, V. H., & Siegrist, M. (2015). Public perception of climate change: The importance of knowledge and cultural worldviews. Risk Analysis, 35(12), 2183–2201. https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.12406

- Shi, J., Visschers, V. H., Siegrist, M., & Arvai, J. (2016). Knowledge as a driver of public perceptions about climate change reassessed. Nature Climate Change, 6(8), 759–762. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2997

- Stern, P. C., Dietz, T., Abel, T., Guagnano, G. A., & Kalof, L. (1999). A value-belief-norm theory of support for social movements: The case of environmentalism. Human Ecological Review, 6(2), 81–97.

- Stevenson, K. T., Peterson, M. N., & Bondell, H. D. (2019). The influence of personal beliefs, friends, and family in building climate change concern among adolescents. Environmental Education Research, 25(6), 832–845. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2016.1177712

- Stevenson, K. T., Peterson, M. N., & Bondell, H. D. (2018). Developing a model of climate change behavior among adolescents. Climatic Change, 151(3–4), 589–603. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-018-2313-0

- Stevenson, K. T., Peterson, M. N., Bondell, H. D., Moore, S. E., & Carrier, S. J. (2014). Overcoming skepticism with education: Interacting influences of worldview and climate change knowledge on perceived climate change risk among adolescents. Climatic Change, 126(3–4), 293–304. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-014-1228-7

- Stevenson, K., & Peterson, N. (2015). Motivating action through fostering climate change hope and concern and avoiding despair among adolescents. Sustainability, 8(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8010006

- Sundblad, E.-L., Biel, A., & Gärling, T. (2007). Cognitive and affective risk judgements related to climate change. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 27(2), 97–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2007.01.003

- Torkar, G., Debevec, V., Johnson, B., & Manoli, C. C. (2021). Assessing children’s environmental worldviews and concerns. CEPS Journal, 11(1), 49–65.

- Tranter, B., & Skrbis, Z. (2014). Political and social divisions over climate change among young Queenslanders. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 46(7), 1638–1651. https://doi.org/10.1068/a46285

- United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (2019). Disaster risk reduction in Cambodia: Status report 2019. United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR), Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific. Retrieved March 10, 2022, from https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/68230_1cambodiaupdaed16oct2019.pdf

- van der Linden, S. (2014). Towards a new model for communicating climate change. In Understanding and governing sustainable tourism mobility (pp. 263–295). Routledge.

- van der Linden, S. (2015). The social-psychological determinants of climate change risk perceptions: Towards a comprehensive model. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 41, 112–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2014.11.012

- van der Linden, S. (2017). Determinants and measurement of climate change risk perception, worry, and concern. In The Oxford encyclopedia of climate change communication. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2953631

- Watson, K., & Halse, C. M. (2005). Environmental attitudes of pre-service teachers: A conceptual and methodological dilemma in cross-cultural data collection. Asia Pacific Education Review, 6(1), 59–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03024968

- World Bank (2020). Data help desk, World Bank country and lending groups. Retrieved February 18, 2022, from https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups

- Wu, L. (2012). Exploring the new ecological paradigm scale for gauging children’s environmental attitudes in China. The Journal of Environmental Education, 43(2), 107–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.2011.616554

- Xue, W., Marks, A. D., Hine, D. W., Phillips, W. J., & Zhao, S. (2018). The new ecological paradigm and responses to climate change in China. Journal of Risk Research, 21(3), 323–339. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2016.1200655