Abstract

Teachers’ conceptions of geography play a key role in teacher identity. They also impact students’ learning. This paper aims to describe teacher students’ conceptions of geography and their sources.

Our data comes from two online questionnaires. Participants came from Switzerland (nQ1 = 20, nQ3 = 98). In contrast to previous research, participants in our studies could not be assigned to only one conception. Eight of 11 statements about what geography is and five of eight statements about the main purpose of geography education were endorsed by 90% or more of participants in both studies. This includes those about understanding sustainability and the system earth. Some items showed significant differences by migration background and by the grade level the students want to teach.

While the results are mostly positive, teacher educators need to find ways to reach those students who do not yet have a current view of geography, e.g. regarding the role of sustainability.

Participants saw diverse sources as shaping their conceptions. Most participants saw specialist literature as an influential and often-used source. Yet, many knew few empirical studies about teaching/learning the subject.

Teacher educators and researchers thus need to find ways to make research literature more memorable for teacher students.

Shulman (Citation1986) argued that different forms of knowledge are important for teachers. One of them is pedagogical content knowledge (PCK), a concept that has been further developed by other authors over time (Shulman, Citation2015). One aspect of teachers’ PCK is their conception of their subject.

Why do teachers’ conceptions of geography matter?

In general, teachers’ conceptions have a big impact on students’ learning. Firstly, teachers’ conceptions affect how they teach a topic (e.g. Barthmann et al., Citation2019; Hannah & Rhubart, Citation2019; Lane, Citation2009). Secondly, teachers can pass on their (mis)conceptions to their students (see e.g. literature reviews in Preston (Citation2015); Yates and Marek (Citation2014)). These two processes also apply to conceptions of their subject. Moreover, Shulman (Citation2015, 4) argues that “if you can’t agree on what a subject entails, it’s rather difficult to design a curriculum to teach it”.

Teachers’ PCK, and thus their conceptions of the subject, are context-dependent (Shulman, Citation2015). Thus, one cannot assume that student teachers in Switzerland have the same conceptions as those found in other countries (e.g. Alkis, Citation2009; Bradbeer et al., Citation2004; Catling, Citation2004, Citation2014; Knecht et al., Citation2020; Morley, Citation2012; Öztürk Demirbas, Citation2013; Preston, Citation2014; Puttick et al., Citation2018; Seow, Citation2016; Virranmäki et al., Citation2019).

The current context for geography education in Switzerland’s German-speaking cantons is the “Curriculum 21” (EDK, Citation2016). The “Curriculum 21” introduced the subject RZG for grades seven to nine. RZG is an abbreviation of the German words for spaces, times, and societies. RZG combines geography, history, and political education. It is similar to social studies in other countries. The cantons decide on how to implement the “Curriculum 21”. Some, such as Basel-Landschaft, teach geography as a separate subject. Others, such as Basel-Stadt, teach geography as part of RZG (Erziehungsdepartement des Kantons Basel-Stadt, Citation2016).

In such a context, what if teachers have no clear conceptions of what “geography” and “history” are? How will their students learn the difference? Research in other countries showed that not all teachers have clear conceptions of their subjects. For instance, Bourke and Lidstone (Citation2015, 7, Australia) found that teacher students “might not really understand the difference between geography and history […]“.

A clear conception of one’s subject is also important for the development of teacher identity, which is part of “becom[ing] a mature teacher” (Shulman, Citation2015, 12). For instance, Seow (Citation2016, Singapore) showed links between teacher students’ identity and their conceptions of geography. Similarly, Tambyah (Citation2008, Australia) found that a “lack of knowledge” led to many teacher students not incorporating the subject SOSE into their identity. SOSE stands for “Studies of Society and Environment”.

What are teachers’ conceptions of geography?

No studies to answer this question for Switzerland seem to exist.

Many of the existing studies from other countries are inspired by Catling’s (Citation2004) work (, all studying teacher students). Knecht et al.’s (Citation2020) study found that teacher students’ conceptions differ between discipline and school subject.

Table 1. Overview of some studies based on the category system popularized by Catling.

While these categories are widely used, other studies used different category systems (e.g. Alexandre, Citation2009; Öztürk Demirbas, Citation2013; Virranmäki et al., Citation2019; Walshe, Citation2007). For instance, Bourke and Lidstone (Citation2015, 7–8, n = 112, Australia) found that teacher students had “seven main discourses”: (1) “mapping”, (2) “history,” (3) “globalists,” (4) “earthists,” (5) “sustainability “(“similar to Catling’s environmentalists“), (6) “excursions,” and a (7) “negativity towards geography“. In Bradbeer et al.’s study (2004, n = 153, Australia, New Zealand, UK, USA) undergraduate geography students saw geography as: “the Study of the World”, “the Study of the World divided into Human and Physical Dimensions”, “the study of people–environment interactions”, the “Study of Spatial Patterns” and “Areal Differentiation or the Study of Places” (22–23).

The studies in show differences within the UK and differences between countries. There were also differences in the prevalence of conceptions between countries in Bradbeer et al.’s study (2004).

Many studies use open-ended questions or open formats such as interviews, mind/concept maps, or document analysis (Alexandre, Citation2009; Bourke & Lidstone, Citation2015; Bradbeer et al., Citation2004; Öztürk Demirbas, Citation2013; Seow, Citation2016; Virranmäki et al., Citation2019; Waldron et al., Citation2009; Walshe, Citation2007, and all studies in ). There is a lack of studies that use closed-question formats.

Where do teachers’ conceptions of geography come from?

Only a few studies look at the sources of teacher (students’) conceptions of geography. For example, Virranmäki et al. (Citation2019, 109–110, n = 11, Finnland) found that the conceptions of the geography of in-service upper-secondary teachers came from “the national core curriculum […]”, textbooks, “free time activity […], their own understanding of the world and their studies at university”, and “[t]he surrounding world”. Teachers also “follow[ed] different media sources in order to gain new geographical information and to update their own understanding” (110). Seow (Citation2016, 155, n = 4, Singapore) found that, when defining geography, “all the pre-service teachers” in her study “t[ook] reference from the syllabuses and textbooks in terms of both geographical content and structure”.

Virranmäki et al. (Citation2019, 110) also showed that “[m]ore than half of the teachers say that they do not know what is happening within the discipline of geography”. This is not an isolated finding. Other studies across countries and subjects also showed that not all teachers/teacher students inform themselves about what is happening in relevant research (e.g. Avci et al., Citation2021; Billo et al., Citation2019; Booher et al., Citation2020; Dekker et al., Citation2012; Lastrapes & Mooney, Citation2020; Mills et al., Citation2020; Schulman, Citation2022; Vanderlinde & van Braak, Citation2010).

This could impact their conceptions of the subject. Shulman (Citation2015, 4–5) stresses “that the content of a discipline […is] not a ‘given’ but […] a decision, a construction, a matter of debate and deliberation”. Therefore, teachers need to keep up with what is happening in their discipline. For example, since the end of the 1960s, geography “turn[ed] away from ‘mailman geography’” (Schmithüsen, Citation2002, translated), i.e. from merely describing where places are and what is there. Modern geography focuses e.g. on spatial variability, human-environment interactions, and sustainability (IGU, Citation2019). Yet, as late as 2011 (!) a professional development workshop for teachers in Switzerland was still titled “Farewell to Mailman’s Geography—What now?” (Reuschenbach, Citation2011, translated).

Moreover, teachers need to keep up with what is happening in geography to base their teaching on current scientific information. This is not always the case. For instance, Pluto has not been considered a planet since 2006 (e.g. CNES, Citation2006). Yet, learning materials on the Swiss teacher portal Zebis still list Pluto as one of the planets of our solar system (Galardi, Citation2018). Encountering current research is especially important in areas such as climate change and sustainable development. For instance, Hannah and Rhubart (Citation2019, 7, USA) found that only 39.7% of teachers acknowledged the vast consensus of scientists on climate change.

Teachers also need to encounter current research in geography education to develop an evidence-based practice (e.g. discussion in Schulman, Citation2022).

Research questions

The literature review identified a lack of studies (a) looking at teacher students’ conceptions of geography in Switzerland and (b) using closed-ended questions. There were only a few studies on the sources of teacher students’ conceptions.

To address these issues, this study uses mainly closed-ended items. The research questions are:

Which conceptions do teacher students in Switzerland have of geography?

Do teacher students consume research literature? Do they see it as shaping their conception of geography? Which other sources do they see as shaping their conception?

Method

We collected data as part of the #TCDTE project. TCDTE stands for “Teacher Concepts of Digital Tools in Education”. The #TCDTE project was a pilot project. It collected data on areas such as conceptions of the subject and aspects of teaching, interests, use of information sources, and more. We used online questionnaires implemented in Questback and written in German. Only questions selected for this paper are described here. All questions and any write-in answers are translated for this paper.

The questionnaire was developed over time. Two versions of the questionnaire contribute data to this paper. The two versions are labeled Q1 and Q3 throughout. The samples for Q1 and Q3 are reported separately, as some questions were phrased differently.

The data was analyzed in SPSS. SPSS’ SUM function was used to check how many of the statements participants agreed to. Group differences were evaluated with Mann-Whitney U tests with a 0.05 significance level.

Participants

The #TCDTE project targeted teachers and teacher students. Participants were recruited in classes for teacher students and through messages at one institution as well as through emails and contacts.

This paper includes only participants () who gave informed consent, wanted to be or were geography/RZG teachers, and answered at least part of the “What is geography…?” question. Two participants did not state they were teacher students and were excluded. Participants who claimed prior participation in the project were not excluded (nQ1 = 3, nQ3 = 9). Data collection before Q1 did not include geography. For Q3, these participants’ current or previous codes (the latter only specified by five of them) did not match any code of the Q1 sample.

Table 2. Description of the teacher students in the two samples.

Not all remaining participants chose to answer all items. This means items have varying n numbers.

describes the sample and thus can help to compare this study to others. The majority of both samples already have some teaching experience, although not necessarily at all (or only) in the grades they are studying for. As part of the teacher education program, teacher students must do teaching practices. Additionally, many teacher students in Switzerland already have part-time teaching positions in school.

Testing for differences for all variables described in is beyond the scope of this paper. In some cases, it is impossible due to small cell sizes. Previous studies ( and Bradbeer et al., Citation2004) have found considerable differences in conceptions between countries. Consequently, this paper tests for differences between participants with and without a migration background. This cultural factor could influence students’ conceptions.

Selected questions

To answer research question 1, we selected two rating-scale questions ( and ). The options for the geography question () were based on the results of and partly translated from earlier studies of conceptions (such as Catling, Citation2004; Morley, Citation2012; Preston, Citation2015) as well as Viehrig et al. (Citation2012) and (DGfG, Citation2012). The options for the geography education question () were partly based on the history version of the questionnaire, partly e.g. on general geography education literature (e.g. Bar-Gal & Bar-Gal, Citation2008; Reinfried & Haubrich, Citation2015; Schrüfer, Citation2003), curricula, standards and the like (e.g. DGfG, Citation2012; EDK, Citation2016; IGU, Citation2019).

Table 3. “What for you is ‘geography’? geography is … Please evaluate every option.”

Table 4. In your opinion, what’s the main purpose of geography education? Geography education should… Please evaluate each option.

To answer research question 2, we selected three questions from the questionnaires ( and , ). The options for the questions in and were mostly based on earlier history versions of the questionnaire.

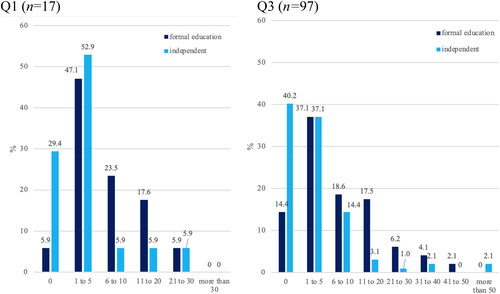

Figure 1. “How many scientific empirical studies about learning and teaching geography do you know approximately? Not just the name, but e.g. either read the article, heard a summary of results, …” (Q1)/“How many scientific empirical studies about learning and teaching your subject do you know approximately? Not just the name, but e.g. either read the article, heard a summary of results during a presentation, …. This refers to your subject(s), i.e. learning and teaching geography, history, politics, RZG, philosophy, ethics, religion, ERG.” (Q3) In both versions, participants could select one of the given options.

Table 5. “How often do you access the following sources of information regarding geography? Please evaluate every option.” (Q1)/“How often do you access the following sources of information regarding your subject? Please evaluate every option. This question refers to your respective subject/s, i.e. geography, history, politics, social studies, philosophy, ethics, religion, ethics-religions-community.” (Q3).

Table 6. “What do you think has particularly strongly shaped your current image of the world/of geography? Please evaluate every option” (Q1)/ ”What do you think has particularly strongly shaped your current image of the subject matter of your subject? Please evaluate every option. This refers to your subject, i.e. e.g. your image of the past, your image of geography/the world, your image of philosophy, etc.” (Q3).

In four of the selected questions () participants also had the option to write in and rate answers. The write-in option was rarely used. If participants only rated the write-in answer (e.g. “does not apply” or “rather applies”) without writing in anything to specify what they are rating that answer is not reported.

Results

Research question 1: which conceptions do teacher students in Switzerland have of geography?

shows participants’ conceptions of geography. For the write-in option, in Q3, one participant each said (rating it “fully applies”) “the formation of the earth”, “understanding of space” and “interdisciplinary”. One wrote “the construction of apparent realities”, but did not rate the item.

On average, participants in Q1 rather or fully agreed to 10.40 of the specified options (SD = 1.05, Mdn = 11, range 8–11, n = 20). 70.0% of participants rather or fully agreed to all 11 specified options (n = 20). In Q3, the average was 10.05 (SD = 1.37, Mdn = 11, range 4–11, n = 98) and 54.1% agreed to all 11 options (n = 98).

In Q3, there were significant differences by migration background in several items (), while in Q1 there were none. Q1 had a small sample size, which made it harder to detect significant differences.

Table 7. Geography is … items with significant differences by migration background (Q3).

shows participants’ conceptions about the purpose of geography education. For the write-in option, in Q3, one participant wrote “to enable the students to recognize the problem of euro-centric perspectives” (“fully applies”)

Of the eight specified options, participants in Q1 on average rather or fully agreed to 6.32 (Mdn = 7, SD = 1.16, range 3–8, n = 19). Only 5.3% of participants rather or fully agreed to all specified options (n = 19). In Q3, the average was 6.24 (Mdn = 6, SD = 1.19, range 3–8, n = 98) and 14.3% agreed to all eight options (n = 98).

In Q3, only “to supply the students with a comprehensive geographic knowledge” showed a significant difference by migration background (without: M = 3.29, Mdn = 3, SD = 0.67, n = 59, range 1–4; with: M = 3.63, Mdn = 4, SD = 0.55, n = 32, range 2–4, p = 0.015). In Q1 there were no significant differences.

Research question 2: Do teacher students consume research literature? Do they see it as shaping their conception of geography? Which other sources do they see as shaping their conception?

shows that participants use a variety of sources for information. Most participants claimed they rather or very often use specialist literature.

In Q3, only use of biographies showed a significant difference by migration background (without: M = 1.95, Mdn = 2, SD = 0.79, range 1–4, n = 60; with: M = 2.45, Mdn = 3, SD = 0.72, range 1–4, n = 31, p = 0.003). In Q1 there were no significant differences.

shows that in Q1, 53.0% of participants reported knowing five or fewer studies from their formal education. 82.3% of participants reported knowing five or fewer studies from independent reading, etc. In Q3 these numbers were 51.5% and 77.3%, respectively.

In Q3 there was a significant difference for independent study knowledge by migration background (p = 0.020, with teacher students without a migration background knowing less). In Q1 there were no significant differences.

displays how participants saw the impact of different sources on their conceptions. All but one of the sources in Q1 have at least someone saying it influenced their image of the subject “rather a lot” or “very much”.

The write-in option for another subject, in Q3, was used to specify art, biology, Latin, “French, English, Latin”, math, music, and religion (one each), as well as German (two), and history (four). Two participants specified the subject “economics, work, housekeeping” (WAH), whereby one of them explained: “concerning sustainability”.

In the write-in option for “something else”, one participant specified “TV programs” (“rather influenced a lot”). The rating “influenced very much” was used by one participant each specifying “Podcast about history on Spotify. 1 HOUR HISTORY”, “politics” and “academic studies as an environmental engineer”. Another participant specified “friend” without a rating.

In Q3 there were significant differences by migration background in several items (). In Q1, there were none.

Table 8. Sources influencing participants’ conceptions – difference by migration background (Q3).

For some participants, sources they use frequently (“often” or “very often”) seem to impact their conception “rather little” or “(almost) not at all”. For specialist literature, this was claimed by 11.8% of participants in Q1 (n = 17) and 22.4% in Q3 (n = 85). For their academic studies, these values are 6.7% (n = 15) and 15.2% (n = 79) respectively. The values are even higher for many of the digital information sources (Wikipedia: Q1 16.7%, n = 12, Q3 39.1%, n = 69; digital social networks: Q1 16.7%, n = 6, Q3 22.7%, n = 22; institutional internet offers Q1 63.6%, n = 11, Q3 66.7%, n = 51; private internet offers Q1 71.4%, n = 7, Q3 40.0%, n = 25).

Discussion and outlook

Research question 1: Which conceptions do teacher students in Switzerland have of geography?

Our paper describes teacher students’ conceptions of geography in Switzerland, which had not been studied before.

Understanding the system earth is central to geography education (e.g. DGfG, Citation2012). Nearly all teacher students (Q1: 100%, Q3: 99%) see it as part of geography. Moreover, overall, 90% (Q1) and almost 92% (Q3) of participants see promoting sustainable development/fighting against environmental problems and managing the global human responsibility for the earth as part of geography.

Our results differ considerably from earlier studies from other countries (e.g. Alkis, Citation2009; Catling, Citation2004; Knecht et al., Citation2020; Morley, Citation2012; Preston, Citation2014; Puttick et al., Citation2018). All our participants saw several aspects as part of what geography is.

These differences could be due to using rating items instead of classifying qualitative data. When participants must write a text, they might only write the first idea that comes to their mind. Rating statements, however, can trigger more conceptions.

These differences might also be due to having a Swiss sample. Previous studies showed differences between countries in participants’ conceptions of geography (e.g. Bradbeer et al., Citation2004 or comparing the different studies using Catling’s categories in ).

Cultural differences can occur even within one country. One example is teacher students with and without a migration background. Yet previous studies usually did not discuss such differences (e.g. Alkis, Citation2009; Bourke & Lidstone, Citation2015; Bradbeer et al., Citation2004; Catling, Citation2004; Knecht et al., Citation2020; Preston, Citation2014; Puttick et al., Citation2018). Our study adds to the literature by examining these differences. In Q3, conceptions that can be seen as associated with “mailman geography” and the supply of geographic knowledge are significantly more frequent among students with a migration background than among those without one. Conversely, students with a migration background see sustainability and managing the responsibility for the earth as significantly less part of geography than those without a migration background.

Research question 2: Do teacher students consume research literature? Do they see it as shaping their conception of geography? Which other sources do they see as shaping their conception?

Our study also adds to the existing body of research by asking teacher students what they think has shaped their image of geography. Although the question was phrased somewhat differently in Q1 and Q3, the results show how diverse sources of teacher students’ conceptions can be. In Seow (Citation2016) and Virranmäki et al. (Citation2019), fewer sources were seen as shaping the conceptions.

In both earlier studies (Seow, Citation2016; Virranmäki et al., Citation2019), curriculum and school textbooks were influential sources for participants’ conceptions of geography. In our study, this did not seem to be the case. No mention was made explicitly of these two sources in the write-in option. Moreover, the areas in which these sources are encountered had a considerable share of participants seeing them as (almost) not or little influential for their conceptions, namely own geography classes (Q1 27.8%, Q3 33.3%) and academic studies (Q1 5.6%, Q3 20.6%).

Students are likely to encounter a current understanding of geography in specialist literature and their academic studies. Most participants often use specialist literature as an information source regarding geography/their subject. Most see it as influential for their conceptions. But for 11.1% of participants in Q1 and 27.8% in Q3, specialist literature has had “(almost) not at all” or “rather little” impact on their conception.

Many participants report knowing only a few empirical studies about geography education/their subject’s education. Our study thus confirms earlier results that much of current geography education research is not reaching many teacher students (e.g. Avci et al., Citation2021; Billo et al., Citation2019). This is also an issue in other countries and subject areas, (e.g. Alhumidi & Uba, Citation2017; Dekker et al., Citation2012; Galton, Citation2000). Moreover, a study in Germany found that not even all teacher educators read empirical research (Diery et al., Citation2020). However, geography teaching should be evidence-based (see e.g. discussion in Schulman, Citation2022).

Avci et al. (Citation2021, 17, translated), in a study in Switzerland, found that teachers/teacher students informed themselves “significantly more often about geography research results than about results concerning geography education”. Future studies should differentiate between these two types of specialist literature.

The low number of studies teacher students claim to know from their education can have two reasons. (1) Much of the geography teacher education they have experienced so far did not discuss research results. (2) Their geography teacher education did not discuss research in a manner that “stuck” and made it easy to recall. Future research should explore ways to solve this problem (see also discussion in Schulman, Citation2022).

The #TCDTE rating items did not differentiate between introductory textbooks and research or between current research and older research. In a study in the UK, Galton (Citation2000) “asked teachers to list any research projects or findings that had influenced their teaching”. The results showed that for those that did name any research at all, “for the most part [it] concerned publications in the early nineteen eighties”. Future studies should thus differentiate between different types of specialist literature.

Differences between Q1 and Q3

Two questionnaire versions (Q1, Q3) contributed data to this paper. Differences in results between Q1 and Q3 could be caused by the small sample size of Q1. The different phrasing (geography vs. the subject) in some questions also could have affected results.

Moreover, secondary II teacher students were only part of the Q3 sample. Students wanting to teach secondary II usually only have one or two subjects. They have different requirements than those wanting to teach secondary I (FHNW, Citation2022). Thus, those wanting to teach secondary II were likely exposed to more geography courses than participants wanting to teach secondary I. Only two geography conception items show significant differences between those studying for secondary I and secondary II (). Both cases can be seen as being related to “mailman” geography, which is less prevalent among secondary II students. The only significant difference in the conception of the purpose of geography education is in the item dealing with “a politically correct worldview” (sec I: M = 2.74, Mdn = 3, SD = 0.85, range 1–4, n = 76; sec II: M = 2.11, Mdn = 2, SD = 0.76, range 1–3, n = 18, p = 0.005). Future studies should explore the effects of a range of individual characteristics on teacher students’ conceptions (e.g. number of completed geography courses).

Table 9. Geography is … items with significant differences between secondary I and II (Q3).

So what?

Our results lead to three conclusions for practice:

Firstly, teacher educators and researchers need to find ways to make research more memorable for teacher students.

Secondly, teacher educators need to find ways to reach those students who do not have a current understanding of geography. This applies especially to the role of sustainability.

Thirdly, researchers can use the new framework we uncovered, in which teachers can hold varied conceptions of geography simultaneously instead of just being one “type”. Studies exploring the impact of culture vs. question format (open or closed) would be especially valuable.

Acknowledgments

Funds from the FHNW supported the #TCDTE project. Thanks to the participants. Thanks to all those who commented on the questionnaire during its development. Thanks to T.S. Thanks as well to both reviewers and editors for their helpful comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alexandre, F. (2009). Epistemological awareness and geographical education in Portugal: The practice of newly qualified teachers. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 18(4), 253–259. https://doi.org/10.1080/10382040903251067

- Alhumidi, H. A., & Uba, S. Y. (2017). Arabic Language Teachers’ engagement with published educational research in Kuwait’s Secondary Schools. International Journal of Higher Education, 6(2), 20. https://doi.org/10.5430/ijhe.v6n2p20

- Alkis, S. (2009). Turkish geography trainee teachers’ perceptions of geography. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 18(2), 120–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/10382040902861213

- Avci, O., Ferraro, F., Fischbach, M., Giger, N., Gilgen, T., Sahdeva, P., & Schulman, K. (2021). Wie sollten Forschungsergebnisse kommuniziert werden, so dass sie Lehrpersonen wirklich etwas bringen?Das Beispiel Klimawandel. Ein Studierendenprojekt im Rahmen des Moduls „Spezifische Aspekte geografiedidaktischer Forschung “im HS 2020. Retrieved August 17, 2021, from http://www.gesellschaftswissenschaften-phfhnw.ch/studierende-forschen-im-hs2020/.

- Bar-Gal, Y., & Bar-Gal, B. (2008). ‘To tie the cords between the people and its land’: Geography education in Israel. Israel Studies, 13(1), 44–67. https://doi.org/10.2979/ISR.2008.13.1.44

- Barthmann, K., Conrad, D., & Obermaier, G. (2019). Vorstellungen von Geographielehrkräften über Schülervorstellungen und den Umgang mit ihnen in der Unterrichtspraxis. Zeitschrift Für Geographiedidaktik, 47(3), 78–97.

- Billo, B., Meier, S., Oswald, A., von Lewinski, A., Wäschle, C., Zaugg, S., & Viehrig, K. (2019). Kommen fachdidaktische Forschungsergebnisse in der Praxis an? Ein Studierendenprojekt im Rahmen des Moduls “Spezifische Aspekte geografiedidaktischer Forschung”. Retrieved April 29, 2019, from http://www.gesellschaftswissenschaften-phfhnw.ch/studierende-forschen-ergebnisse-des-fachdidaktischen-studierendenprojekts-aus-dem-hs-2018/.

- Booher, L., Nadelson, L. S., & Nadelson, S. G. (2020). What about research and evidence? Teachers’ perceptions and uses of education research to inform STEM teaching. The Journal of Educational Research, 113(3), 213–225. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2020.1782811

- Bourke, T., & Lidstone, J. (2015). Mapping geographical knowledge and skills needed for pre-service teachers in teacher education. SAGE Open, 5(1), 215824401557766. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244015577668

- Bradbeer, J., Healey, M., & Kneale, P. (2004). Undergraduate geographers’ understandings of geography, learning and teaching: A phenomenographic study. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 28(1), 17–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309826042000198611

- Catling, S. (2004). An understanding of geography: The perspectives of English primary trainee teachers. GeoJournal, 60(2), 149–158. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:GEJO.0000033575.54510.c6

- Catling, S. (2014). Pre-service primary teachers’ knowledge and understanding of geography and its teaching: A review. RIGEO, 4(3), 235–260.

- CNES. (2006). Pluto is no longer a planet. Retrieved March 31, 2022, from https://cnes.fr/en/web/CNES-en/5360-pluto-is-no-longer-a-planet.php.

- Dekker, S., Lee, N. C., Howard-Jones, P., & Jolles, J. (2012). Neuromyths in education: Prevalence and predictors of misconceptions among teachers. Frontiers in Psychology, 3, 429. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00429

- DGfG. (2012). (Ed.). Bildungsstandards im Fach Geographie für den Mittleren Schulabschluss mit Aufgabenbeispielen. Selbstverlag Deutsche Gesellschaft für Geographie.

- Diery, A., Vogel, F., Knogler, M., & Seidel, T. (2020). Evidence-based practice in higher education: Teacher educators’ attitudes, challenges, and uses. Frontiers in Education, 5, 62. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2020.00062

- EDK. (2016). Lehrplan 21. Räume, Zeiten, Gesellschaften (mit Geografie, Geschichte). Retrieved August 30, 2021, from http://v-ef.lehrplan.ch/.

- Erziehungsdepartement des Kantons Basel-Stadt. (2016). Geografie und Geschichte als Teilbereich von „Natur, Mensch, Gesellschaft “auf der Primarstufe und als Fachbereich „Räume, Zeiten, Gesellschaften “auf der Sekundarstufe I – Eckwerte zur Umsetzung des Lehrplans. Retrieved March 03, 2022, from https://www.edubs.ch/publikationen/material/downloads/Factsheet_NMG_RZG_BS_161115.pdf/download.

- FHNW. (2022). Fachwissenschaftliche Zulassungsbedingungen für den Studiengang Sekundarstufe II (Lehrdiplom für Maturitätsschulen). Retrieved October 10, 2022, from https://www.fhnw.ch/de/die-fhnw/hochschulen/ph/rechtliche-dokumente-und-rechtserlasse/rechtserlasse-ausbildung/112-4c_fachwissenschaftlichezulassungsbedingungenstudiengangsekundarstufeii.pdf.

- Galardi, S. (2018). Die Planeten. Retrieved March 31, 2022, from https://www.zebis.ch/sites/default/files/teaching_material/planetensystem_teil_1.pdf.

- Galton, M. (2000). Integrating theory and practice: Teachers’ perspectives on educational research. Paper presented at the ESRC Teaching and Learning Research Programme, First Annual Conference - University of Leicester. Retrieved November 2000, from http://www.leeds.ac.uk/educol/documents/00003247.htm,.

- Hannah, A. L., & Rhubart, D. C. (2019). Teacher perceptions of state standards and climate change pedagogy: Opportunities and barriers for implementing consensus-informed instruction on climate change. Climatic Change, 158(3-4), 377–392. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-019-02590-8

- IGU. (2019). International charter on geographical education. Retrieved July 18, 2022, from https://www.igu-cge.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/IGU_2016_eng_ver25Feb2019.pdf.

- Knecht, P., Spurná, M., & Svobodová, H. (2020). Czech secondary pre-service teachers’ conceptions of geography. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 44(3), 458–473. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098265.2020.1712687

- Lane, R. (2009). Articulating the pedagogical content knowledge of accomplished geography teachers. Geographical Education, 22, 40–50.

- Lastrapes, R. E., & Mooney, P. (2020). Teachers’ use and perceptions of research-to-practice articles. Exceptionality, 29(5), 375–389. https://doi.org/10.1080/09362835.2020.1772068

- Mills, M., Mockler, N., Stacey, M., & Taylor, B. (2020). Teachers’ orientations to educational research and data in England and Australia: Implications for teacher professionalism. Teaching Education, 32(1), 77–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/10476210.2020.1843617

- Morley, E. (2012). English primary trainee teachers’ perceptions of geography. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 21(2), 123–137. https://doi.org/10.1080/10382046.2012.672678

- Öztürk Demirbas, Ç. (2013). Perceptions of pre-service social sciences teachers regarding the concept of “Geography” by mind mapping technique. Educational Research and Reviews, 8(9), 496–505.

- Preston, L. (2014). Australian primary pre-service teachers’ conceptions of geography. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 23(4), 331–349. https://doi.org/10.1080/10382046.2014.946325

- Preston, L. (2015). Australian primary in-service teachers’ conceptions of geography. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 24(2), 167–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/10382046.2014.993173

- Puttick, S., Paramore, J., & Gee, N. (2018). A critical account of what “geography” means to primary trainee teachers in England. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 27(2), 165–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/10382046.2017.1321304

- Reinfried, S., & Haubrich, H. (Eds.). (2015). Geographie unterrichten lernen. Die Didaktik der Geographie. Cornelsen.

- Reuschenbach, M. (2011). Abschied von der Briefträgergeografie –was nun? Schulblatt Des Kantons Zürich, 2/2011, 48. https://edudoc.ch/record/92396/files/Schulblatt_2_11.pdf(2).

- Schmithüsen, F. (2002). Wandel des Erdkundeschulbuchs seit dem Kieler Geographentag. Retrieved March 22, 2022, from http://www.schmithuesen.de/Dissertation/3-8322-0153-X_ABS.PDF.

- Schrüfer, G. (2003). Verständnis für fremde Kulturen. Entwicklung und Evaluierung eines Unterrichtskonzepts für die Oberstufe am Beispiel von Afrika [Dissertation]. Universität Bayreuth.

- Schulman, K. (2022). Research publications’ impact on geography teachers. In E. Artvinli, I. Gryl, J. Lee, & J. T. Mitchell (Eds.), Geography teacher education and professionalization (pp. 161–177 Springer

- Seow, T. (2016). Reconciling discourse about geography and teaching geography: The case of Singapore pre-service teachers. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 25(2), 151–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/10382046.2016.1149342

- Shulman, L. S. (1986). Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching. Educational Researcher, 15(2), 4–14. https://doi.org/10.2307/1175860

- Shulman, L. S. (2015). PCK. Its genesis and exodus. In A. Berry, P. Friedrichsen, & J. Loughran (Eds.), Re-examining pedagogical content knowledge in science education (pp. 3–13). Routledge.

- Tambyah, M. (2008). I am a geography and SOSE teacher: Developing a subject identity in pre-service secondary social science teachers. Retrieved September 20, 2017, from https://www.aare.edu.au/publications-database.php/5781/i-am-a-geography-and-sose-teacher-developing-a-subject-identity-in-pre-service-secondary-social-scie.

- Vanderlinde, R., & van Braak, J. (2010). The gap between educational research and practice: Views of teachers, school leaders, intermediaries and researchers. British Educational Research Journal, 36(2), 299–316. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411920902919257

- Viehrig, K., Siegmund, A., Wüstenberg, S., Greiff, S., & Funke, J. (2012). Systemisches und räumliches Denken in der geographischen Bildung – Erste Ergebnisse zur Überprüfung eines Modells der Geographischen Systemkompetenz. In A. Hüttermann, P. Kirchner, S. Schuler, & K. Drieling (Eds.), Räumliche Orientierung: Räumliche Orientierung, Karten und Geoinformation im Unterricht (pp. 95–102). Westermann.

- Virranmäki, E., Valta-Hulkkonen, K., & Rusanen, J. (2019). Powerful knowledge and the significance of teaching geography for in-service upper secondary teachers – A case study from Northern Finland. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 28(2), 103–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/10382046.2018.1561637

- Waldron, F., Pike, S., Greenwood, R., Murphy, C. M., O’Connor, G., Dolan, A., & Kerr, K. (2009). Becoming a teacher. Primary student teachers as learners and teachers of history, geography and science: An All-Ireland study. Retrieved May 03, 2021, from https://www.academia.edu/4354553/BECOMING_A_TEACHER_PRIMARY_STUDENT_TEACHERS_AS_LEARNERS_AND_TEACHERS_OF_HISTORY_GEOGRAPHY_AND_SCIENCE_AN_ALL_IRELAND_STUDY.

- Walford, R. (1996). ‘What is geography?’ an analysis of definitions provided by prospective teachers of the subject. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 5(1), 69–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/10382046.1996.9964991

- Walshe, N. (2007). Understanding teachers’ conceptualisations of geography. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 16(2), 97–119. https://doi.org/10.2167/irgee212.0

- Yates, T. B., & Marek, E. A. (2014). Teachers teaching misconceptions: A study of factors contributing to high school biology students’ acquisition of biological evolution-related misconceptions. Evolution: Education and Outreach, 7(1), 18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12052-014-0007-2