Abstract

Geographical thinking is often regarded as one of the most crucial outcomes of geography education. Nevertheless, with the growing variety of definitions and conceptualizations surrounding geographical thinking, the entire concept is becoming increasingly intricate and abstract, gradually acquiring a degree of internal shallowness. To address this complexity and enhance the clarity regarding these diverse definitions and conceptualizations, a systematic review was conducted. Following the PRISMA guidelines, a final selection of 50 records including empirical articles, books and book chapters, were analyzed. The main findings reveal insights on temporal development, spatial distribution, and possible classifications of geographical-thinking definitions and conceptualizations. The article concludes with a discussion of possible implications for educational practice and related recommendations for future research.

Introduction

Almost 80 years ago, Smith (Citation1945) argued for the implementation of geographical thinking within geography lessons, saying that it would help students become purposeful thinkers and successful doers rather than “animated gazetteers.” She described the poor state of geographical thinking among students in the United States and lamented about how geography was taught.

Nowadays, scholars largely agree on the importance of geographical thinking. The vast majority of researchers believe that geographical thinking plays a pivotal role in conceptualizing the world, as it helps us make sense of its overwhelming complexity and better understand its immeasurable interconnectedness. Such thinking is of great value, and it is considered to be powerful in various ways (Brooks et al., Citation2017).

The case for thinking geographically becomes even more convincing in the current context of the Anthropocene. In this epoch driven by human activities, geographical thinking empowers us to foster a more sustainable and resilient future. Valuing and developing geographical thinking should thus be prioritized as an appropriate educational response (Lambert, Citation2023).

Furthermore, implementing geographical thinking in schools is one approach to replacing the descriptive, fact-based image of geography. As Jackson (Citation2006) pointed out, demonstrating the power of geographical thinking might also address geography’s outdated content and reverse the increasing fall in students’ numbers and erroneous perceptions around geography.

Though the field of geographical thinking research has undergone immense development since Smith’s article (1945), some of her crucial questions remain unresolved. Despite the importance of geographical thinking, there is no cohesive consensus regarding what it actually is or how it should be developed and evaluated in schools. Consequently, divergent definitions, approaches, and conceptualizations around geographical thinking abound (e.g., Brooks et al., Citation2017). In addition, with more and more articles loosely employing the term geographical thinking, the term itself is becoming rather shallow.

Therefore, this article aims to summarize and classify different conceptualizations and definitions of geographical thinking and identify the most influential literature from this perspective. Moreover, it aims to identify and reflect on the temporal development and spatial distribution of articles defining and conceptualizing geographical thinking and to indicate how they could evolve in the future. It is not the intention of this article to suggest new ways of defining geographical thinking; rather, we seek clarity on already extant knowledge.

Theoretical premises: clarifying the terminology

To better contextualize the results of the following literature review, this section briefly outlines our current understanding of geographical thinking within the discipline of geography education.

In the field of geography in general, geographical thinking is commonly associated with shifting and evolving paradigms of geography and is mainly related to names such as Carl Ritter, Friedrich Ratzel, Richard Hartshorne, Vidal de la Blache, etc., and terms such as qualitative revolution, spatial science, etc. However, in geographical education, geographical thinking mostly refers to the cognitive process of thinking like a geographer. Even though these two approaches share some common ground (e.g., Morgan, Citation2013), it is crucial to differentiate between them, with our focus being on the latter.

Geographical thinking is often mentioned in the context of other concepts, such as spatial thinking (e.g., Metoyer & Bednarz, Citation2017), relation thinking (e.g., Karkdijk et al., Citation2019a), system thinking (Cox et al., Citation2019b, Citation2019a), geographical reasoning (Karkdijk et al., Citation2019b), geographic literacy (Favier & Van der Schee, Citation2014), and powerful knowledge (e.g., Maude, Citation2016), among others (e.g., Bendl et al., Citation2023). Even though geographical thinking shares common traits with these concepts, we treat it as a self-sufficient concept standing on its own. We do not aspire to fully grasp all the other mentioned concepts, as each would entail its own systematic review.

Methods

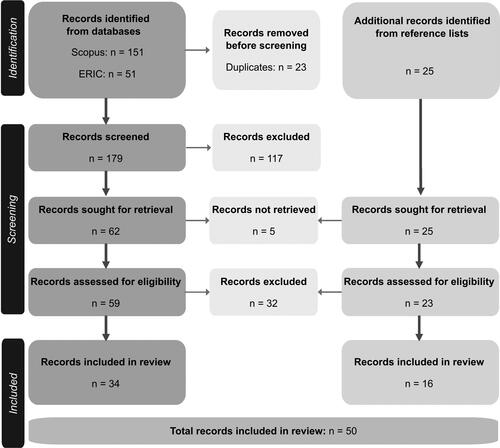

To identify different conceptualizations and definitions of geographical thinking, we conducted a systematic review. We followed PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses) 2020 during the review (Page et al., Citation2021).

Literature search

The Scopus and ERIC databases were used to search for relevant English written literature (similarly Bernhäuserová et al., Citation2022). The search extended beyond empirical studies to include all peer-reviewed articles, review articles, and conference papers.

To eliminate the potential omission of relevant literature in this phase of review, the search command was assembled from commonly used synonyms of the term geographical thinking. As a result, we used the following combination of keywords in the command:

“geographical thinking” OR “geography thinking” OR “geographic thinking” OR “geographically thinking” OR “think* geographically” OR “thinking through geography” OR “think* like a geographer*” OR “think* like geographer*”

Screening process

In the first stage, the first and second author independently inspected the identified titles and abstracts and confirmed that they were related to geographical thinking from the perspective of geographical education. The record eligibility criteria were further specified due to the unsatisfactory inter-coder reliability (80.4%, Cohen’s kappa − 0.61). Records that not only perceived geographical thinking similarly as geography educators but focused on geography education (and not e.g., on biology education) and had the potential to provide a definition/conceptualization of geographical thinking (i.e., not only mentioned geographical thinking marginally) were considered relevant. Thanks to this specification, the agreement between the coders was sufficiently high (97.8%, Cohen’s kappa − 0.96), and the coders solved the remaining four disagreements.

Based on this screening, we sought the relevant records for retrieval. In case the full text was not found, their corresponding authors were contacted. Despite that, the full text of several records remained unobtained (). It was thus necessary to exclude these from the full-text screening. We deemed the records eligible for the review if they met at least one of the following criteria:

It directly states a definition of geographical thinking.

It indirectly states a definition of geographical thinking by referring to another source.

It states the conceptualization(s) of geographical thinking.

It states specific aspects of geographical thinking.

As in the first screening, the first and second author independently inspected the records. The agreement between them was 88.1%, and Cohen’s kappa was 0.76. As there were minimal disagreements between the coders, these were individually resolved through discussion. In the end, 34 records from the databases were included in the review ().

To not omit definitions of geographical thinking stated in the books or book chapters not included in the selected literature database, we supplemented the search pool with all references stated in the 34 included records that met the search criteria (see ). This screening process was identical to the previous one. Based on the first and second author’s coding, 16 records were added to the review. Therefore, 50 total records were comprised the research sample pool for this review.

Data extraction and analysis

A structured data extraction form was developed by authors onto which the relevant data from each included record were extracted. An extensive table showing the extracted data appears in the Appendix.

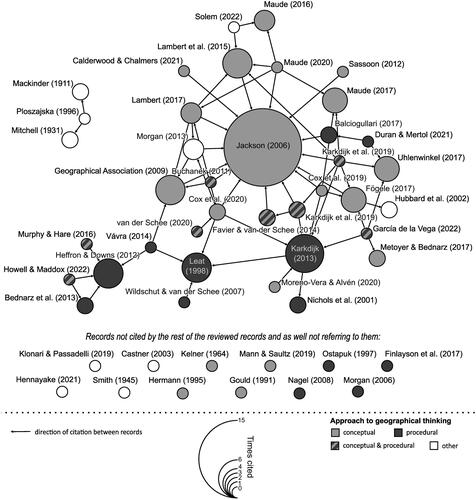

In addition to the summary narrative text describing and classifying the various perspectives on geographical thinking, we also synthesized the data into a citation network, i.e., a diagram depicting how the included records cite one another. The citation network was created using Gephi graph visualization and manipulation software. More specifically, Gephi’s Force Atlas layout was used. The visualization was then graphically enhanced using Inkscape software.

Results and discussion

This section addresses the three primary objectives of this article. Firstly, it addresses and reflects on the publishing trend in geographical thinking in geography education research. Secondly, it deals with the spatial distribution of the publications defining and conceptualizing geographical thinking. Lastly, it provides a classification and further discussion of the identified definitions and conceptualizations of geographical thinking and presents the most influential publications from this perspective.

Publishing trend in geographical thinking research

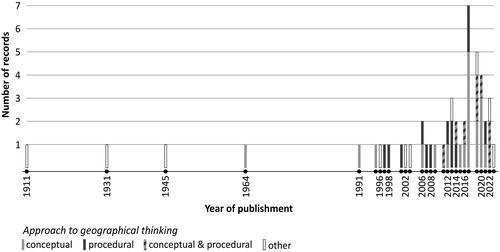

The analysis of annual publication on geographical thinking in geography education research offers valuable insights into the broader developmental trends within this field. The oldest relevant publication was by Mackinder (Citation1911), who strongly emphasized the importance of thinking geographically, rather than simply remembering plain facts and place names. As illustrates, international research on geographical thinking in geography education displays a discernible upward trajectory, particularly over the past two decades. This trend underlines the increasing research momentum and growing scholarly interest in this topic.

Figure 2. Frequency of the records on geographical education in relation to their publication year. The distinguished approaches to geographical thinking are characterized in the section “Classifying Identified Definitions and Conceptualizations.”

Three main periods of publishing research about geographical thinking were identified. The first phase extended from 1911 to 1994. Within this phase, only a small number of publications that defined geographical thinking in geography education were identified. This indicates that research on this topic was in its infancy compared to the upcoming phases. The second phase lasted from 1995 to 2010, during which some highly influential definitions and conceptualizations of geographical thinking were proposed (e.g., Jackson, Citation2006; Geographical Association, Citation2009). These ideas served as a stepping stone for further research . The last phase, which started in 2011, saw a considerable increase in the number of publications, reflecting the growing vitality of geographical thinking–oriented research. More recently, scholars have become increasingly interested in geographical thinking since it is believed to be a fundamental part of powerful knowledge. We believe that the general interest in powerful knowledge coming from the GeoCapabilites project phase 3 (Mitchell, Citation2022) is one of the main reasons for this strong development trend.

Although we acknowledge the importance of the concept of powerful knowledge in geography education and welcome the interest it generated around geographical thinking, we believe that geographical thinking is such an influential concept that it can stand on its own. Consequently, we feel that characterizing geographical thinking only as part of some “higher” concept (powerful knowledge, geographical reasoning, etc.) could hinder the attention devoted to it in the upcoming fourth phase. Especially in light of the evidence that the implementation of geographical thinking into school practice has been insufficient (e.g., Hennayake Citation2022), it is surprising that it is already becoming part of an even more complex concept, the implementation of which will most likely be even more difficult.

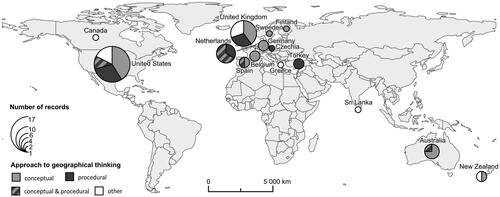

Spatial distribution of the identified publications

Spatial distribution analysis of the 50 identified records reveals highly uneven results (see ). The analysis clearly illustrates a substantial concentration of scholarly contributions from the “West,” especially the United States and the United Kingdom. This concentration can be attributed to these nations’ influential roles in shaping the discourse on geographical thinking in geography education. While this literature concentration highlights the substantial research output from these countries, it also underscores the need for a more global perspective on the topic, as perspectives from other regions may provide valuable insights and diverse viewpoints.

While the spatial distribution mentioned above is true overall, throughout the course of time, the publications have become more geographically diversified. While in the first one hundred years (since 1911), publications came only from the United States and the United Kingdom, the third phase shows higher diversity (see the Appendix), as significant contribution to the field is also visible, for example, from Benelux countries. This line of research is often inspired by Leat’s Thinking Through Geography strategies (Leat, Citation1998; see ) and examines either the effect of these strategies or the relational thinking that is considered the core of geographical thinking (Karkdijk et al., Citation2019a).

Classifying identified definitions and conceptualizations

The primary purpose of this systematic review was to summarize and classify different ways of defining and conceptualizing geographical thinking in geography education. Across all the reviewed publications, three key approaches for defining geographical thinking emerged. The publications most frequently (n = 19) explicitly linked geographical thinking to key geographical concepts (for more about key geographical concepts, refer to Taylor (Citation2008); Fögele (Citation2017); Maude (Citation2020), etc.). The second most prevalent (n = 13) way of defining and conceptualizing geographical thinking was through procedural dimensions, namely specific high-order thinking skills (HOTS). In several publications (n = 8), these two approaches were synthesized when defining geographical thinking and thus formed a third key approach.

The remaining 10 publications did not align with any of these approaches, leading to the formation of a fourth cluster named “other.” The following subsections characterize each cluster and further illuminate the various discrepancies within them. It is worth noting that authors describing and characterizing only one dimension of geographical thinking might not mean that they do not consider other dimensions to also be integral, as it might have been the authors’ goal to focus on a single dimension within the given paper (for more, see the section “Limitations”).

Thinking geographically through key geographical concepts

The most attention has been given to the conceptual dimension of geographical thinking, as the results suggest it is the most common way of defining geographical thinking (see the Appendix). Within this line of research, geographical thinking is inherently linked to the key concepts considered to be the discipline’s cornerstones, which allow us to think geographically (Cox et al., Citation2020; Calderwood and Chalmers, Citation2021). Though these publications share their association of geographical thinking with these key concepts (e.g., Sassoon, Citation2012), several discrepancies within their definitions exist.

Most importantly, there is no clear consensus over what the key concepts forming geographical thinking are (compare, for example, Maude (Citation2017) and Metoyer and Bednarz (Citation2017)). The most frequently mentioned key concepts include place, space, environment, scale, and some form of their interrelations/interactions/relations. Sometimes they are referred to as themes, core concepts, big ideas, or even cornerstones, and they often occur at different levels of hierarchy. Following Cox et al. (Citation2019a), we conclude that the selection of the key concepts usually varies according to an author’s beliefs, academic background, or research aims (compare Gould (Citation1991), Hermann (Citation1996), Mann and Saultz (Citation2019), and Moreno-Vera and Alvén (Citation2020)).

In addition to the differences related to the key concepts, their definitions of geographical thinking differ as well. For example, Cox et al. (Citation2020) noted that some aspects of geographical thinking consist of human–nature interactions, scale, local–global relationships, geographical issues, and their linkages to personal choices. Uhlenwinkel (Citation2017) similarly claimed that “people who think geographically use geographical concepts such as place, space, scale, interdependence, diversity, proximity or distance to analyse the phenomena in the world around them” (p. 45). In contrast, Kelner (Citation1964) applied a rather determinist approach and elaborated on the definition from the student’s perspective: “When a pupil understands that much of the nature of Egyptian life is related to that of the Nile River, and that slow developing Southeast Asia is handicapped in part by a forested, swampy countryside making transportation and communication difficult then the pupil not only knows geography, but he thinks like a geographer” (p. 34). Kelner further concluded that, by thinking geographically, students can find a deeper meaning in the fundamentals of human existence.

The most cited primary resource in our systematic review (both within the conceptual approach and in general) was Jackson (Citation2006) (see ), as 15 of the 36 later published records referred to his article. He argued that thinking geographically “enables a unique way of seeing the world, of understanding complex problems and thinking about inter-connections at a variety of scales (from the global to the local)” (Jackson, Citation2006, p. 199). He advocated for space and place, scale and connection, proximity and distance, and relational thinking as the key disciplinary concepts, and further explained how they function using a specific example of consumer ethics. Such explanations, we believe, are great tools to communicate the true meaning of geographical thinking and how to help its implementation in schools.

Another strong line of research within the conceptual dimension originated from David Lambert’s research (e.g., Geographical Association, Citation2009; Lambert et al., Citation2015). To explain geographical thinking, Lambert provided a three-part analogy in which he described geographical core knowledge as “vocabulary” and conceptual knowledge as “grammar” (e.g., Lambert, Citation2017). This analogy acknowledges the important role of facts (every language needs a vocabulary), but it is still the concepts (the grammar) that allow us to group and understand these bits of information and facts.

Within this line of thought, the influential Geographical Association’s manifesto “A Different View” (Geographical Association, Citation2009) was established (). It treats geographical thinking as an essential educational outcome of learning geography: “To be able to apply knowledge and conceptual understanding about the changing world to new settings, that is to think” (Geographical Association, Citation2009, p. 10). Lambert (Citation2017) added that, while absorbing the vast amount of geographical facts might be impressive, it is not itself a sign of intellectual development. For that, conceptual knowledge development—which entails a certain set of rules, procedures, and patterns—is needed.

From all the above-mentioned definitions, it is apparent that the discrepancies within the conceptual approach are substantial. To sufficiently understand the conceptual approach to geographical thinking, it is crucial to describe the connection between key concepts and thinking geographically. In other words, how does the key concept make you think geographically? However, only a small number of current studies have attempted to answer this question.

Thinking geographically through high-order thinking skills

Another identified approach of conceptualizing geographical thinking is through its procedural dimension. Thirteen studies (26% of the sample) were classified within this approach (see and the Appendix). These publications were not primarily focused on geographical content, but rather on specific skills that should be applied to this content.

The vast majority of the analyzed records within the procedural dimension relate geographical thinking to inquiry (e.g., Ostapuk, Citation1997; Morgan, Citation2006; Nagel, Citation2008; Vávra, Citation2014; Mertol, Citation2021). Bednarz et al. (Citation2013) argued that geographic inquiries support students’ capacity to engage in geographical thinking and that it emphasizes geography’s disciplinary thinking. Furthermore, Finlayson et al. (Citation2017) claimed that engaging students in research tasks is an effective way to foster their geographical thinking. Nagel (Citation2008) however, noted that “thinking geographically is not a research-oriented approach to investigating the world; rather it is a way to know where something is, how its location influences its characteristics, and how its location influences relationships with other phenomena” (p. 358).

Despite the differences mentioned above, to some extent, all those publications framed their definition of geographical thinking within National Geography Standards from the United States (e.g., NGS, Citation2012), which are based mainly on an inquiry process. This process consists of five key stages: asking geographical questions, acquiring geographical information, organizing geographical information, analyzing geographical information, and answering geographical questions (NGS, Citation2012). In the secondary literature, these steps may slightly differ among different authors (compare, for example, NGS (Citation2012) and Bednarz et al. (Citation2013)).

Here, again, David Leat’s Thinking Through Geography project (TTG) (Leat, Citation1998; Nichols et al., Citation2001) proved influential (see ), becoming a strong source of inspiration for much of the Dutch research on geographical thinking. Leat (Citation1998) introduced well-thought-out strategies for developing thinking skills through geography based on five key components: information-processing skills, reasoning skills, inquiry skills, creative thinking skills, and evaluation skills. Although it is unclear to what extent are these components part of thinking geographically, the primary emphasis on the procedural dimension is apparent. According to Wildschut and Van Der Schee (Citation2007), these TTG strategies make students think about the unique and constantly changing world they live in, improve their ways of thinking, and, most importantly, encourage them to think geographically.

It is crucial to mention that Leat (Citation1998) linked those strategies not only with the general thinking skills (procedural approach) mentioned above but also with so-called “big concepts” (classification, cause and effect, location, decision making, planning, inequality, systems, and development). Thus, Leat (Citation1998) focused heavily on the procedural dimension of geographical thinking, he also underlined the importance of central underpinning concepts, as he claimed that, without them, geography would become a mass of disconnected content.

The last identified approach for defining geographical thinking within the procedural dimension implements cognitive taxonomies (Favier & Van der Schee, Citation2014; Karkdijk et al., Citation2019a; Howell & Maddox, Citation2022). These studies employed not only cognitive taxonomies but also the key concepts, and therefore are classified and further elaborated on in the following section.

Synthesizing conceptual and procedural dimensions of geographical thinking

A total of eight studies (16% of the sample) employed a combination of the previously two described approaches for defining geographical thinking (see and the Appendix). This way of defining geographical thinking has become especially apparent over the last decade (see ). While the definitions in the first phase focused mostly on one dimension only, the latter often synthetized more complex approaches together. Their relative novelty from a temporal perspective might be why none of them were identified as highly influencing the rest of the reviewed publications (see ).

Though the line between these classifications is very thin, several significant discrepancies within various definitions of this synthesizing approach can be observed. For example, García De La Vega (Citation2022) treats geographical thinking as a cognitive domain but defines it mainly in relation to the key concepts. He argues that teaching geography through key concepts helps organize and link content in geography lessons. This way of learning is believed to help with students’ cumulative learning, their understanding of geography as an intellectual core of knowledge, and their ability to think geographically (García De La Vega, Citation2022).

A slightly stronger emphasis on the conceptual dimension is also apparent in Karkdijk et al. (Citation2019b) and Murphy and Hare (Citation2016). While Karkdijk et al. (Citation2019b) concluded that geographical thinking is a reasoning process in which students apply their geographical conceptual knowledge to specific regional contexts, Murphy and Hare (Citation2016) developed the idea of so-called cross-cutting themes. All these authors, however, strongly linked their differently framed conceptual dimensions to the procedural dimension. Murphy and Hare (Citation2016) even provided a specific example through the city of Shanghai, claiming that geographical thinking occurs when “one asks questions about the city’s internal spatial organization and material landscape, its changed relative location, and the ways in which the city’s unique history and geographical characteristics influenced the direction that development took” (p. 97).

Several other identified records that employed the synthetizing approach primarily emphasized the procedural dimension of defining geographical thinking. For example, while Howell and Maddox (Citation2022) also discussed geographical thinking in the context of the main geographical themes, they focused primarily on the inquiry process that comes with it and referred exclusively to the records from the procedural dimension (). This strong focus on specific geographical thinking skills can be further traced to Van der Schee (Citation2020), who argued that students should learn high-order thinking skills comprising geographical thinking.

Another example of this approach appeared in Karkdijk et al. (Citation2019b), who concluded that using mysteries and concept maps (one of many TTG strategies) fosters relational geographical thinking. This type of thinking is treated as a “core” of thinking geographically, as this line of research builds on Haubrich, who claimed that “to think geographically, students have to be able to formulate correct geographical relationships explaining the world around them” (as cited in Karkdijk et al., Citation2013, p. 184).

The works of Buchanek (Citation2011), Favier and Van der Schee (Citation2014), and Karkdijk et al. (Citation2019a) took a slightly different approach to defining geographical thinking with an emphasis on the procedural dimension. These articles combined the two dimensions by discussing the key concepts in the context of cognitive taxonomies. While Favier and Van der Schee (Citation2014) claimed that many of the thinking processes within fall in the categories “analyzing,” “evaluating,” and “creating” of the revised Bloom Taxonomy, Karkdijk et al. (Citation2019a) employed the structure of observed learning outcomes (SOLO) taxonomy to measure the specific outcome of geographical thinking exercises.

Other approaches to defining geographical thinking and their specific aspects

The rest of the identified records (n = 10, 20% of the sample) did not fit any of the previous approaches for defining and conceptualizing geographical thinking (see the Appendix). Apart from Morgan (Citation2013), these publications stand at the edge of the citation network, as they neither refer to other records defining/conceptualising geographical thinking nor are cited by the later records on this topic (). Moreover, these publications mostly did not use a direct definition of geographical thinking. Instead, they focused on some relevant geographical thinking aspects (e.g. Mitchell Citation1931). Since these aspects repeatedly appeared in relation to geographical thinking throughout our whole sample of 50 records, we conclude the results section with a brief overview of these aspects (in bold) and their relevance to geographical thinking.

Throughout the analysis, a few descriptions of geographical thinking revolved around what it is not (i.e., definition by negation and difference). For instance, Mackinder (Citation1911) asserted that it encompasses more than mere knowledge of place names and facts, and Hennayake (Citation2022) differentiated between mere memorization of facts and true geographical thinking.

Even though these publications demonstrate the difference between content knowledge memorization and thinking geographically, they do not neglect the importance of this knowledge in geographical thinking. Some even emphasized its importance, as there is consensus that, to some extent, thinking geographically, builds upon these factual knowledge bases (e.g., Morgan, Citation2006). Similarly, geographical thinking is presumed to be less available to those who lack geographical knowledge. Moreover, several authors concluded that, to think geographically, students need something relevant to think about (e.g., Smith, Citation1945; Balciogullari, Citation2017).

Furthermore, thinking geographically has been repeatedly mentioned in tandem with relational thinking (especially in the Dutch literature, e.g., Karkdijk et al., Citation2013; Favier & Van der Schee, Citation2014; Karkdijk et al., Citation2019b), system thinking (e.g., Cox et al., Citation2020; Van der Schee, Citation2020), spatial and geospatial thinking (e.g., Metoyer & Bednarz, Citation2017; Klonari & Passadelli, Citation2019), and visualizations, visual images, and map reading (e.g., Ploszajska, Citation1996; Castner, Citation2003). However, how these aspects relate to geographical thinking varies vastly among authors. The aspects briefly covered in this review and which are also commonly characterized with relation to geographical thinking include inquiry (e.g., Nagel, Citation2008; Finlayson et al., Citation2017; Howell & Maddox, Citation2022), powerful knowledge (e.g., Solem, Citation2023), and critical thinking (Hubbard et al., Citation2002).

Implications for educational practice and related recommendations for future research

The results from the systematic review confirm that several different ways of conceptualizing and defining geographical thinking exist. Even within the specific dimensions of conceptualizing geographical thinking, several discrepancies were identified. It is clear that geographical thinking revolves around key concepts, high-order thinking skills, and other particular aspects (such as spatial thinking, relational thinking, etc.). However, it remains unclear what the specific concepts, concrete thinking skills, and aspects are and how they work together to foster the development of geographical thinking.

Lack of scholarly consensus might also be one of the causes of scarce research evaluating whether school lessons foster geographical thinking (except for the Dutch line of research, e.g., Karkdijk et al., Citation2019a). The findings partially explain the unsatisfactory and insufficient implementation of geographical thinking within school practice. What connects the several definitions of geographical thinking noted throughout this review is not only the general approach or specific key concept or high-order thinking skill they focus on, but often also their abstractness and their complexity. This fact, however, makes the implementation of geographical thinking even more difficult.

The results of this systematic review reveal the variability in defining and conceptualizing geographical thinking and its consequences, including the danger of emptying the term of its meaning. We believe that this should be of great interest to scholars since geographical thinking is considered one of the most important goals of geography education (e.g., Geographical Association, Citation2009).

In the second rounds of our screening process, we analyzed almost 90 publications dealing with geographical thinking. Nearly half of these publications included the concept of geographical thinking in their title or abstract without explaining it at all in the publication itself. They treated this term as a claim to support their argument. Moreover, its usage varied greatly, including in its meaning. In some cases, the studies simply claimed several high-order thinking skills, such as interpretation or analysis, are the key skills of geographical thinking, failing to elaborate on how these skills are geographical or how they constitute geographical thinking. They did not relate geographical thinking to any concepts or specific authors and operated with this term loosely. In our perspective, this kind of usage makes the term increasingly shallow and rather vacuous (e.g., such as the term “critical thinking”).

Based on our results, we offer four suggestions for future research on geographical thinking we believe could help with its implementation and stop its “definitional emptying”:

Head toward a clear consensus regarding both the conceptual and procedural dimensions of geographical thinking and clarify the role of other aspects, such as spatial thinking, system thinking, etc.

Emphasize the synthetizing approach and clarify the relationships between the key concepts and specific high-order thinking skills instead of investigating only a single facet of geographical thinking.

Employ specific examples and case studies to explain how geographical thinking is developed and related to the selected definition. This should address the question “How exactly are these components of geographical thinking developing students’ capacity to think geographical?”

Encourage research that would verify if and how geographical thinking is fostered and evaluated and research paying attention to teachers’ understanding of this term.

Limitations

Despite their indisputable value, several relevant publications (e.g., Uhlenwinkel, Citation2013; Nilsson & Bladh, Citation2022), could not be included in our study, as they did not meet the strict methodological criteria outlined in PRISMA. The reasons for this included, among others, not being written in English or not being indexed in specific research databases. To mitigate this limitation, a second round of analysis was conducted (for further details, see the “Methods” section).

The second set of limitations primarily stems from the classification of the analyzed definitions. By assigning a definition to a specific approach, such as conceptual or procedural, we do not intend to imply that the author automatically neglected the second dimension of geographical thinking. It might have been the author’s intention to focus solely on one dimension. For example, Balciogullari (Citation2017) definition of geographical thinking elaborated exclusively on the procedural dimension, but later the author also acknowledged the significance of key concepts such as place and scale. Since these additional considerations were not explicitly stated within the definition itself, it was classified within the procedural dimension (this applies, for example, to Leat (Citation1998), Morgan (Citation2006), and Lambert (Citation2017)). The interconnectedness between the two key identified approaches is also apparent from the citation network depicted in , since, for instance, all the records defining geographical thinking using the conceptual dimension did not strictly refer only to other records from this approach. Notwithstanding the limitations of this study, we believe these constrains will not hinder its capacity to serve as a certain “guidepost” for future research endeavours.

Conclusion

This systematic review builds on vast foundations of already existing knowledge and provides a unique overview of one of the most vital outcomes of geography education: geographical thinking. We believe that geographical thinking should not only be seen as a pivotal objective of geography education but also as an opportunity to enhance its overall standing and relevance in contemporary society.

A more in-depth analysis of the reviewed literature reveals that, while some scholars strictly associate geographical thinking with the key concepts of the discipline, others align it with high-order thinking skills or contextualize it within specific theoretical frameworks, such as powerful knowledge or spatial thinking. The most complex approach to conceptualizing geographical thinking involves a synthetic perspective that combines both the conceptual and procedural dimensions and reflects scholars’ growing interest in the topic over the past decade. Although these definitions have the potential to comprehensively elucidate the essence of geographical thinking, they often tend to be highly complex and abstract, rendering their implementation in practical school settings a formidable challenge.

In conclusion, the findings presented herein evince an increasing scholarly interest in geographical thinking over the past two decades, especially in the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Netherlands. While this surge in interest is undoubtedly positive and pivotal for the advancement of geographic education as an academic discipline and for teaching geography in schools, it also poses certain risks. Our results suggest that the proliferation of diverse definitions and conceptualizations is progressively diluting the concept. Thus, in concluding this study, we would like to underline this peril, as we are keen to prevent geographical thinking from becoming lost in the vast sea of ambiguous (or elusive) and incomprehensible interpretations.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article was originally published with errors, which have now been corrected in the online version. Please see Correction (http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10382046.2024.2369445).

References

- * Balciogullari, A. (2017). Geographical thinking approach in geography education. In M. Pehlivan & W. Wu (Eds.), Research highlights in education and science 2017 (pp. 26–24). ISRES.

- *Bednarz, S. W., Heffron, S., & Huynh, N. T. (Eds.) (2013). A road map for 21st century geography education: Geography education research. Association of American Geographers.

- Bendl, T., Marada, M., & Havelková, L. (2023). Preservice geography teachers’ exposure to problem solving and different teaching styles. Journal of Geography, 122(3), 66–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221341.2023.2220114

- Bernhäuserová, V., Havelková, L., Hátlová, K., & Hanus, M. (2022). The limits of GIS implementation in education: A systematic review. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 11(12), 592. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi11120592

- Brooks, C., Butt, G., & Fargher, M. (Eds.). (2017). The power of geographical thinking. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-49986-4

- *Buchanek, R. (2011). How differences of opinion influence students’ capacity to think geographically. The International Journal of the Humanities: Annual Review, 9(3), 141–156. https://doi.org/10.18848/1447-9508/CGP/v09i03/43183

- *Calderwood, R., & Chalmers, L. (2021). Geography scholarship, scholarship and thinking. New Zealand Geographer, 77(2), 130–136. https://doi.org/10.1111/nzg.12292

- *Castner, H. W. (2003). Photographic mosaics and geographic generalizations: A perceptual approach to geographic education. Journal of Geography, 102(3), 121–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221340308978533

- Cox, M., Elen, J., & Steegen, A. (2019a). Systems thinking in geography: Can high school students do it? International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 28(1), 37–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/10382046.2017.1386413

- *Cox, M., Elen, J., & Steegen, A. (2019b). The use of causal diagrams to foster systems thinking in geography education: Results of an intervention study. Journal of Geography, 118(6), 238–251. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221341.2019.1608460

- *Cox, M., Elen, J., & Steegen, A. (2020). Fostering students geographic systems thinking by enriching causal diagrams with scale. Results of an intervention study. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 29(2), 112–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/10382046.2019.1661573

- *Favier, T., & Van der Schee, J. (2014). Evaluating progression in students’ relational thinking while working on tasks with geospatial technologies. Review of International Geographical Education Online RIGEO, 4(2), 155–181.

- *Finlayson, C., Gregory, M., Ludtke, C., Meoli, C., & Ryan, M. (2017). Cultivating geographical thinking: A framework for student-led research on food waste. Review of International Geographical Education Online RIGEO, 7(1), 80–93.

- *Fögele, J. (2017). Acquiring powerful thinking through geographical key concepts. In C. Brooks, G. Butt, & M. Fargher (Eds.), The power of geographical thinking (pp. 59–73). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-49986-4_5

- *García De La Vega, A. (2022). A proposal for geography competence assessment in geography fieldtrips for sustainable education. Sustainability, 14(3), 1429. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031429

- *Geographical Association. (2009). A different view: A manifesto from the Geographical Association.

- *Gould, P. (1991). Guest essay: Thinking like a geographer. The Canadian Geographer/Le Géographe Canadien, 35(4), 324–332. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0064.1991.tb01297.x

- *Hennayake, N. (2022). Reflecting on geography higher education in Sri Lanka: Unpacking/releasing the hegemonic burden…. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 47(1), 34–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12455

- *Hermann, D. (1996). Developing a spatial perspective: Using the local landscape to teach students to think geographically. Journal of Geography, 95(4), 162–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221349608978716

- *Howell, J. B., & Maddox, L. E. (2022). Geographic inquiry for citizenship: Identifying barriers to improving teachers’ practice. The Journal of Social Studies Research, 46, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jssr.2022.04.001

- *Hubbard, P., Kitchin, R., Bartley, B., & Fuller, D. (2002). Thinking geographically: Space, theory and contemporary human geography. Continuum Book.

- *Jackson, P. (2006). Thinking geographically. Geography, 91(3), 199–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/00167487.2006.12094167

- *Karkdijk, J., Admiraal, W., & Van Der Schee, J. (2019a). Small-group work and relational thinking in geographical mysteries. Review of International Geographical Education Online, 9(2), 402–425. https://doi.org/10.33403/rigeo.588661

- *Karkdijk, J., Van Der Schee, J. A., & Admiraal, W. F. (2019b). Students’ geographical relational thinking when solving mysteries. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 28(1), 5–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/10382046.2018.1426304

- *Karkdijk, J., Van Der Schee, J., & Admiraal, W. (2013). Effects of teaching with mysteries on students’ geographical thinking skills. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 22(3), 183–190. https://doi.org/10.1080/10382046.2013.817664

- *Kelner, B. G. (1964). To think like geographers: Philadelphia introduces a new course of study. Journal of Geography, 63(1), 32–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221346408985085

- *Klonari, A., & Passadelli, A. S. (2019). Differences between dyslexic and non-dyslexic students in the performance of spatial and geographical thinking. Review of International Geographical Education Online, 9(2), 284–303. https://doi.org/10.33403/rigeo.510360

- *Lambert, D. (2017). Thinking geographically. In M. Jones (Ed.), The handbook of secondary geography education (pp. 20–30). Geographical Association.

- Lambert, D. (2023). Teaching in the human epoch: The geography of it all. GEReCo UK IGU-CGE. https://www.gereco.org/2023/01/30/teaching-in-the-human-epoch-the-geography-of-it-all/.

- *Lambert, D., Solem, M., & Tani, S. (2015). Achieving human potential through geography education: A capabilities approach to curriculum making in schools. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 105(4), 723–735. https://doi.org/10.1080/00045608.2015.1022128

- *Leat, D. (1998). Thinking through geography. Chris Kington Publishing.

- *Mackinder, H. (1911). The teaching of geography from an imperial point of view, and the use which could and should be made of visual instruction. The Geographical Teacher, 6(2), 79–86.

- *Mann, B., & Saultz, A. (2019). The role of place, geography, and geographic information systems in educational research. AERA Open, 5(3), 233285841986934. https://doi.org/10.1177/2332858419869340

- *Maude, A. (2016). What might powerful knowledge look like? Geography, 101(2), 70–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/00167487.2016.12093987

- *Maude, A. (2017). Applying the concept of powerful knowledge to school geography. In C. Brooks, G. Butt, & M. Fargher (Eds.), The power of geographical thinking (pp. 27–40). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-49986-4_3

- *Maude, A. (2020). The role of geography’s concepts and powerful knowledge in a future 3 curriculum. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 29(3), 232–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/10382046.2020.1749771

- *Mertol, H. (2021). The geographical thinking skills and motivation of the students in the departments of Geography in Turkey. International Journal of Curriculum and Instruction, 13(2), 1778–1801.

- *Metoyer, S., & Bednarz, R. (2017). Spatial thinking assists geographic thinking: Evidence from a study exploring the effects of geospatial technology. Journal of Geography, 116(1), 20–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221341.2016.1175495

- Mitchell, D. (2022). GeoCapabilities 3—Knowledge and values in education for the Anthropocene. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 31(4), 265–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/10382046.2022.2133353

- *Mitchell, S. L. (1931). Geographic thinking. The New Era in Home and School, 12, 245–248.

- *Moreno-Vera, J. R., & Alvén, F. (2020). Concepts for historical and geographical thinking in Sweden’s and Spain’s primary education curricula. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 7(1), 107. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00601-z

- *Morgan, A. (2006). Developing geographical wisdom: Postformal thinking about, and relating to, the world. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 15(4), 336–352. https://doi.org/10.2167/irg199.0

- *Morgan, J. (2013). What do we mean by thinking geographically?. In M. Jones & D. Lambert (Eds.), Debates in geography education (pp. 273–281). Routledge.

- *Murphy, A. B., & Hare, P. R. (2016). The nature of geography and its perspectives in ap ® human geography. Journal of Geography, 115(3), 95–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221341.2015.1111405

- *Nagel, P. (2008). Geography: The essential skill for the 21st century. Social Education, 72(7), 354–358.

- *Nichols, A., Kinninment, D., & Leat, D. (2001). More thinking through geography. Chris Kington Publishing.

- Nilsson, S., & Bladh, G. (2022). Thinking geographically? Secondary teachers’ curriculum thinking when using subject-specific digital tools. Nordidactica, 3, 171–203.

- *NGS. (2012). Geography for life: National geography standards (2nd ed.). National Council for Geographic Education.

- *Ostapuk, M. A. (1997). The Dragon and the Anchor: Using a field experience, journaling, and writing to teach the five geographic skills sets. Journal of Geography, 96(4), 196–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221349708978787

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 372, n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

- *Ploszajska, T. (1996). Constructing the subject: Geographical models in English schools, 1870–1944. Journal of Historical Geography, 22(4), 388–398. https://doi.org/10.1006/jhge.1996.0026

- *Sassoon, H. (2012). Teaching the geography of development from the big picture. Teaching Geography, 37(3), 113–115.

- *Smith, V. B. (1945). High school geography and geographic thinking. Journal of Geography, 44(6), 232–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221344508986469

- *Solem, M. (2023). Geography achievement and future geographers. The Professional Geographer, 75(2), 207–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/00330124.2022.2081227

- Taylor, L. (2008). Key concepts and medium term planning. Teaching Geography, 33(2), 50–54.

- Uhlenwinkel, A. (2013). Spatial thinking or thinking geographically? On the importance of avoiding maps without meaning. Gl_Forum, 1, 294–305.

- *Uhlenwinkel, A. (2017). Geographical thinking: Is it a limitation or powerful thinking? In C. Brooks, G. Butt, & M. Fargher (Eds.), The power of geographical thinking (pp. 41–53). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-49986-4_4

- *Van der Schee, J. (2020). Thinking through geography in times of the COVID-19 pandemic. J-READING Journal of Research and Didactics in Geography, 2(9), 21–30. http://www.j-reading.org/index.php/geography/article/view/259.

- *Vávra, J. (2014). Cramming facts and thinking concepts: Instance of preparation of student geography teachers in Liberec. Review of International Geographical Education Online RIGEO, 4(3), 261–280.

- *Wildschut, H. M. A., & Van Der Schee, J. A. (2007). Searching for strategies to help students to structure their geographical research papers in a domain specific way. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 16(4), 351–366. https://doi.org/10.2167/irgee222.0