Abstract

Educational frameworks emphasize to students the importance of gaining differentiated worldviews and being open-minded toward other cultures. As a primary medium in class, textbooks should accurately represent diversity to help students develop intercultural awareness and critical thinking. This study aims to analyze geography textbooks’ of Hesse (Germany) on their representation of diversity dimensions across different countries and continents using a multidimensional approach to superdiversity. For the analysis, a qualitative content analysis is initially conducted. Then, the representation of the continents is compared using network analysis. Our findings reveal a biased portrayal across all continents, leading to homogenization within the teaching material. This inconsistency contradicts the curricular requirements of Hessian geography and suggests that the textbook approval process is not sufficiently rigorous in ensuring that the standards are met.

1. Introduction

Globalization, migration, and various social movements bring a high degree of diversity into society (Vertovec, Citation2007), including schools. In Germany, 33% of students have a migration background (Federal Statistic Office, Citation2023), leading to high cultural, ethnic, and socioeconomic diversity in the classroom (Stoicovy, Citation2002). An understanding of diversity can only be established and promoted if teaching materials, appropriately depict diversity (Federal Government Commissioner for Migration, Refugees and Integration, Citation2015). The United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO, Citation2017) emphasizes the importance of representing diverse identities in teaching materials, recognizing that there is greater diversity of identities today than ever before due to increased mobility and globalization. Teaching material can enhance students’ awareness of diversity and various sources of cultural identity (Tabatadze, Citation2015; Tabatadze et al., Citation2020). Therefore, it is crucial that educational materials accurately reflect the multifaceted identities present within and across societies (UNESCO, Citation2017). In Germany, textbooks are one of the most commonly used medium in geography classes (Brucker, Citation2017). They are essential for building students’ knowledge, values, behaviors, and attitudes (Lee, Citation2018; Tabatadze & Gorgadze, Citation2023). Therefore, textbook authors should strive to provide fair and inclusive representations, offering diverse role models and challenging traditional gender norms to broaden students’ perspectives and opportunities (UNESCO, Citation2017).

A reasoned representation is crucial because textbooks are never impartial regarding cultures and ethnicities; their content is often debated and reflects the power imbalances and entrenched beliefs of the dominant culture (Moreau, Citation2003). Textbooks often idealize one nation while misrepresenting others, hindering social cohesion, appreciation of diversity, and tolerance (Greaney, Citation2006). Consequently, textbooks communicate socially and culturally endorsed norms, shaping students’ perceptions of individuals and ethnic groups different from their own (Cornbleth, Citation2002; Greaney, Citation2006). This can result in students internalizing stereotypes, which influences their perceptions of gender, culture, and ethnicity (Dalimunthe et al., Citation2021). Studies of school textbooks, such as the comprehensive study under the auspices of the Federal Government Commissioner for Migration, Refugees and Integration (2015), revealed a significant lack of normalization of diversity and migration across various history, politics and geography textbooks.

Geography education plays a crucial role in developing a diverse worldview. A socially critical geography curriculum (Fien, Citation1999) enables students to appreciate the diversity of people and society and the cultural abundance of humanity (International Geographical Union, Citation1992). To achieve this goal, critical thinking is crucial (Inoue, Citation2005). According to Critical Multicultural Education (CMCE), critical thinking is promoted by “deeper questions” concerning different cultural perspectives, equality, power relations, and the representation of various groups (Jenks et al., Citation2001; Sleeter & Grant, Citation2007). These abilities of changing perspectives and critical thinking are for preventing stereotypes that can lead students to develop biased worldviews (Usher, Citation2023). CMCE specifically addresses geography’s relevance achieving these goals (Picton, Citation2008; Usher, Citation2023). Geography textbooks should promote intercultural and critical thinking (Canale, Citation2016; Davidson & Liu, Citation2020). Therefore, avoiding stereotypes and biases and addressing diversity are crucial when writing and establishing geographical textbooks (Lee et al., Citation2021). To global diversity, accurate representation of countries and continents in geographical content is crucial. However, the representation of countries and continents in textbooks varies significantly (Risager, Citation2021; Tajeddin & Pakzadian, Citation2020) and, textbooks do not seem to favor critical thinking and reflection (Canale, Citation2016).

Education serving a multicultural perspective calls for comprehensive and unbiased representation of continents. Thus, this study aimed to analyze how the representation of countries and continents differs and which patterns of similarities among continents are produced.

2. Theoretical framework

2.1. Textbook analysis on representation of countries and continents

We identified three research approaches for the representation of countries and continents in textbooks: (1) the overall share of countries and continents’ representation, (2) the representation of a specific continent in detail, and (3) the representation of specific diversity dimensions in textbooks.

Focusing on the overall share, Risager (Citation2021) analyzed the general image of the world and the represented range of countries and their image by analyzing all mentioned countries in the analyzed textbooks. The range is mainly wide, however the UK, US, Canada, Ireland, Australia, and South Africa, are the most represented in textbooks, which is a clear focus on the Western world (Risager, Citation2021). The over-representation of the UK and the US is supported by several other analyses of different countries in, for example, Turkish (Toprak & Aksoyalp, Citation2015), American (Hong, Citation2009), Norwegian (Lund, Citation2007), and Saudi (Alsaif, Citation2016) textbooks. There are several critiques on the contribution of represented countries in textbooks; for example, the predominance of Western culture, but not the students’ own culture, in Saudi English textbooks used in universities (Alsaif Citation2016).

Studies focusing on specific continents revealed that Africa is frequently represented in the context of negative aspects, often reduced to diseases and social problems (Hummer, Citation2014). Such portrayals tend to perpetuate postcolonial representations of Black people, including racism, prejudice (Aping et al., Citation2022; Hummer, Citation2014) and Afro-pessimism (Gordon et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, Africa is mostly represented as a continent rather than as individual African countries, leading to homogenization and inadequate representation of the continent (Aping et al., Citation2022). In the context of South America, an analysis of German Spanish textbooks showed that South American children are mainly represented as poor, in need of help, underdeveloped, and problematic (Zabel Citation2022). In contrast, European society is illustrated as the “white rescuer” – progressive and helpful, reflecting a Eurocentric perspective (Tastan et al., Citation2016; Zabel, Citation2022). Many textbook analyses identified an under-representation of several African and Asian countries and an overrepresentation of the US, UK, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand (Lu et al., Citation2022; Xiang & Yenika-Agbaw, Citation2021). The homogenization of Asia is found in American textbooks (Hong, Citation2009), as the representation depends on the political and cultural importance of Asian countries to the US. Thus, Asia is mainly represented by China and Japan because of their economic importance to the US (Hong, Citation2009), leading to bias in American textbooks. The representation of countries and generated bias leads to a lack of global diversity and absence of local cultures (Gómez Rodríguez, Citation2015).

In the textbook analysis of English as a foreign language used in China, Xiang and Yenika-Agbaw (Citation2021) explored issues related to race/ethnicity, gender/sexuality, social class, and disability. The analyzed textbooks taught the learners that each country has one racial/ethnic group, representing them. For example, Han represents China, and whites represent the US, UK, and Canada (Xiang & Yenika-Agbaw, Citation2021).

Textbooks thus limit the opportunity to expose learners the diversity of the world, which also refers to the socioeconomic status. They predominantly depict middle-class individuals as dominating the world and global representations, and the illustrations mostly feature affluent people, while those from lower socioeconomic background are notably absent (Xiang & Yenika-Agbaw, Citation2021). In terms of gender and sex, the study found that only males and females are represented, with males significantly over-represented. People with disabilities are completely excluded from these representations (Xiang & Yenika-Agbaw, Citation2021). An arbitrary representation of 13 diversity dimensions was found by Dörfel et al. (Citation2023) in Hessian geography textbooks. The analyzed 13 dimensions were extremely unevenly represented in their occurrence.

Overall, the existing research primarily focuses on the detailed representation of specific continents or countries, the overall share in countries or continent’s representation, or an analysis of cultural diversity dimensions. A comparison of the representation of countries and continents from a multidimensional perspective will help to bridge these approaches.

2.2. Curricular requirements

In general, the Hessian curriculum demands students to gain a multidimensional and differentiated worldview, be open-minded toward other cultures, and depict the social reality of diversity (Hessian Curricula, Citation2021). The Hessian curriculum highlights the importance of critical thinking (including the context of culture), reflective engagement with facts, and geographic issues. These elements are required in both the lower (grades 5–9) and upper (grades 10–13) curricula, as well as in almost all geographical competency and educational standards. Both curricula require students to gain an intercultural understanding resp. competency; for example “meeting people from different sociocultural contexts and cultures without prejudice and with reflection in their actions” (Hessian Curricula, Citation2023). Geography teaching should, therefore, enable critical thinking in students (Hessian Curricula, Citation2023; Young & Lambert, Citation2014), offering significant opportunities for challenging stereotypes (Picton, Citation2008) and grasping the social reality of diversity (Hessian Curricula, Citation2021).

2.3. Superdiversity in textbook analysis

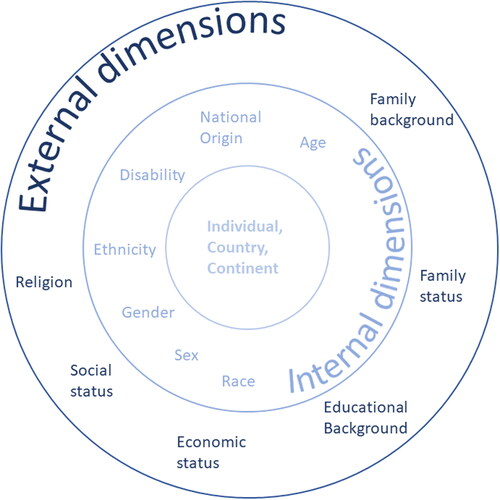

This study is grounded in the superdiversity approach (Vertovec, Citation2007). This approach prompts a reassessment of social categories as multidimensional, fluid, and permeable, contrasting with a 1D group perspective (Vertovec, Citation2007). To address the inherent complexity of modern societies, it is necessary to consider various diversity dimensions simultaneously (Vertovec, Citation2007). That is, individuals or groups should not only have exemplary French national background but also specific economic status, educational background, and for example a disability. To specify this multidimensional approach, we adapted the classification of diversity dimensions by Gardenswartz and Rowe (Citation2002). They classified diversity of individuals into three layers: (1) the internal dimensions (innate) are most stable; (2) the external dimensions (acquired) are more variable over the lifetime of an individual; and (3) the outermost layer is organizational dimensions. We devided the classification into internal and external dimensions and focused on 13 dimensions to describe the diversity of groups of individuals, such as societies, countries, and continents (Dörfel et al., Citation2023) (compare ).

Examining the representation of countries and continents in the context of multidimensional diversity in geography textbooks allows us to evaluate two aspects: first, if textbooks avoid stereotypes and homogenization and, second, if they appreciate the diversity of the countries and continents by adequately representing diversity considering multidimensionality. Not considering an adequate representation can lead to consequences such as Eurocentrism (Nagre, Citation2023; Tastan et al., Citation2016; Zabel, Citation2022); othering (Lippert & Mönter, Citation2021), which means a constructed distinction between “us” and “the others” (Aping et al., Citation2022); and postcolonial representation of cultures and countries (Hong, Citation2009; Risager, Citation2021).

2.3.1. Research aim and research questions (RQs)

The Hessian curriculum demands the development of competencies such as critical thinking, open-mindedness, and interculturality, as well as avoiding prejudices (Hessian Curricula, Citation2021, Citation2023). Considering the concept of superdiversity, diversity dimensions, and their interconnection constitute the complex representation of continents. Homogenizing or simplifying diversity dimensions regarding different countries and continents would contradict curricular requirements.

We therefore aim to answer the following RQs:

RQ1: Does the frequency of diversity dimensions vary across countries and continents in Hessian textbooks?

RQ2: Does the connection in which dimensions occur differ between continents in Hessian textbooks?

3. Methods

3.1. Sampling

Hesse is one of six federal states in Germany with a textbook catalog for lower grades (5–6), middle grades (7–8), and upper grades (10–13) for high school (Gymnasium) (current catalog from 01.08.2022) (Appendix). The Hessian Ministry of Education and Cultural Affairs conducts the admission process. The analysis of all 11 licensed textbooks allows for a verification of the implementation of curricular requirements in representing diversity referring to all grades. The selection is limited to composite media but include all author texts of the 11 textbooks.

3.2. Qualitative content analysis

The textbook content was qualitatively examined using category-guided text analysis (Kuckartz & Rädiker, Citation2022). A category system developed through a deductive-inductive approach was the core of the analysis: 13 categories were initially derived from theoretical frameworks (deductive) and subsequently refined iteratively (inductive) (Kuckartz & Rädiker, Citation2022). This process resulted in a comprehensive coding framework with specific coding rules for each category or dimensions () (Dörfel et al., Citation2023).

Table 1. Coding framework with coding rules for 13 analyzed dimensions (Dörfel et al., Citation2023).

Based on headlines, sub-headings, and paragraphs, we defined coding units to structure the text by self-contained sections for a systematic analysis. We identified a total of 4689 coding units across all textbooks. Using the coding framework, we categorized each unit according to one or more of the 13 defined categories. Accordingly, a coding unit may fall into no category, a single category, or combination of any of the 13 categories.

Concerning the research aims, the main coding rule for categorizing and assigning one or more categories is the relation to a specific room sample. This includes both countries and whole continents. Cities or specific regions as part of a country (e.g. Ruhrgebiet) were subordinated to the country.

A second coder analyzed 36% of the material (4 out of 11 textbooks), using the coding framework independently and achieved similar results. Using Cohen’s (Citation1960) kappa, the intercoder reliability measured was 0.8, which was satisfactory (Greve & Wentura, Citation1997).

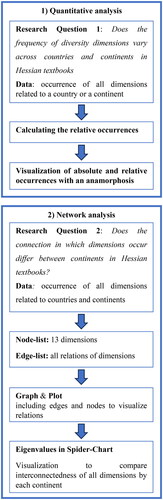

3.3. Quantitative analysis (RQ1)

To answer the RQ1, the results of the qualitative content analysis were evaluated quantitatively. Coding rules were used to identify the occurrence of all 13 diversity dimensions related to a country or a continent.

3.3.1. Countries

First, if one or more categories in a coding unit are related to at least one country, the occurrence of each representative category is attributed to the mentioned country. If there is more than one country as a room sample (e.g. Germany, France, and the UK), the represented dimensions are coded for each of the mentioned countries. Based on this procedure, the absolute occurrence of all diversity dimensions related to countries could be calculated for each country. Adding all absolute occurrences of countries classified into their continents, it was additionally possible to calculate the relative occurrence to evaluate the distribution of all countries of each continent. An anamorphosis visualizes the occurrences of diversity dimensions of all countries based on the absolute occurrences of all countries. The less a country was represented in the context of diversity dimensions, the smaller the country’s surface was illustrated, and the higher it was represented, the bigger its surface in the anamorphosis.

3.3.2. Continents

We calculated the absolute occurrence of all categories related only by the direct name of a continent (e.g. Africa and Europe) to evaluate how differentiated continents are represented. Based on these absolute occurrences, a second anamorphosis of the world’s continents has been created with the same procedure to visualize the results.

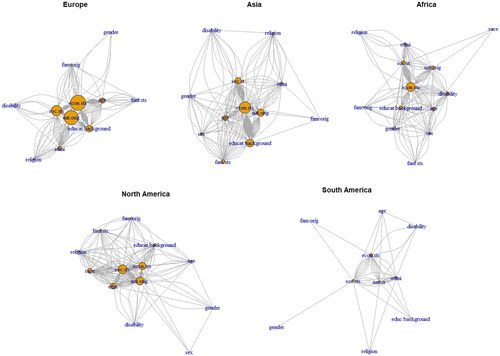

3.4. Network analysis (RQ2)

The network analysis applied graph theory to gain insight into the structure of a network (Newman et al., Citation2006). Nodes define the elements of these structures. The links between the elements are edges. In this study, diversity dimensions define the nodes in the network analysis (compare ). The common occurrence of two dimensions in one coding segment defines an edge. For more than two dimensions in a coding segment, the edges are documented in all pairs possible. We used R software (Douglas et al., Citation2024) and the igraph package (Csárdi et al., 2023) for the analysis. Analyzing the data by continent enables the comparison needed for RQ2. Regarding the occurrence for all dimensions per continent, we added up all codings per country, including the number of codes mentioned for the whole continent, with an exception that multiple answers of countries of the same continent in a single coding unit were only counted once for their continent (e.g. France, Germany, and the UK = 1× for Europe). Multiple countries from different continents in a coding unit were counted once for all different continents. As Oceania had a total occurrence of 13, which is not representative of the analysis, it was not considered for further analysis and discussion. We used two methods to gain insight into the network structure. First, we calculated the eigenvalues (EVs) (Bloch et al., Citation2023) of each node to concisely describe the position the node holds in the network by EV centrality (EVC). The EVC measures centrality based on the neighbor’s connections; a connection to a highly connected neighbor weights more than a loosely connected neighbor (Bloch et al., Citation2023). We depicted the EVs in spider charts using the R package fmsb (Nakazawa, Citation2023) to compare the EV patterns between the continents. Second, we plotted the network graph to depict all nodes and edges coded for each continent. We increased the size of each node by its degree of centrality (Bloch et al., Citation2023) to visualize the dimension’s weight in representing the continent’s diversity in the textbook. The Fruchterman–Reingold algorithm positions the nodes in the plot, locating those with many connections close together and those with few more distant.

Figure 1. Diversity dimensions classified into internal and external dimensions (CC by Dörfel et al., (Citation2023)).

4. Results

This section presents the research finding structured by our RQs.

4.1. RQ1

4.1.1. By countries

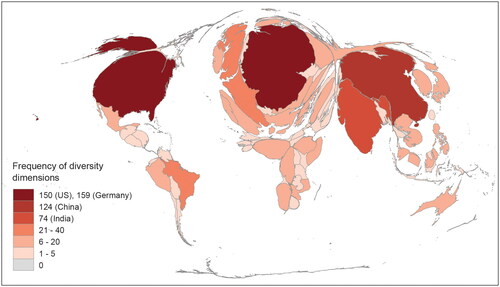

Three different countries on different continents represent a high occurrence of diversity dimensions: Germany (159), the US (150), and China (124) (). By a considerable margin, India is the fourth most diverse represented country in the textbooks (n = 74). Countries missing in were not mentioned in the context of diversity. There are 47 countries listed in with an absolute occurrence of five or less, which is, in total, a relative share of 59% of all represented countries in the context of diversity (n [total] = 80).

Table 2. Absolute occurrences of all analyzed dimensions related to countries represented in textbooks.

visualizes the results by illustrating the surface of all countries in proportion to their occurrence of represented diversity dimensions using value ranges.

Figure 3. Anamorphosis – illustration of countries by occurrence of diversity dimensions (drafted by Dörfel et al. Citation2023 – illustrated by C. Enderle (2023)).

Looking at the relative occurrences of dimensions according by countries (), it is striking that the diversity dimensions of all continents are dominated by only one or two countries. Europe’s diversity representation is dominated by Germany (48%), and is overwhelmingly higher by Western (90%) than Eastern European countries (10%). Asia is represented by China and India (59%), South America by Brazil (44%), and North America by the US (84%). Oceania is represented 100% by Australia. However, it is only mentioned 13 times and, thus, finds little representation overall. The distribution of diversity dimensions in Africa is the most balanced, represented by Nigeria, DR Kongo, and Namibia (45% in total).

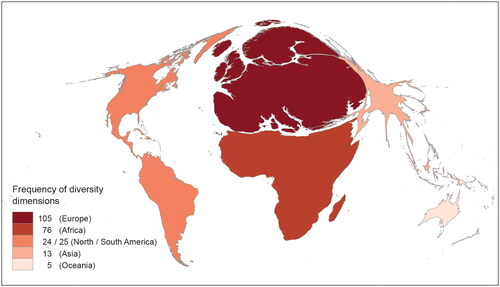

4.1.2. By continents

The absolute occurrences of diversity dimensions shown in significantly differ from those in the context of entire continent (). The highest occurrence of dimensions in the context of an entire continent is Europe (n = 105), followed by Africa (n = 76), and the lowest of Oceania (n = 5) and Asia (n = 13).

Table 3. Relative occurrences of all analyzed dimensions related to countries represented in textbooks.

Table 4. Absolute occurrences of dimensions related to continents.

visualizes this representation of diversity dimensions related to continents through an anamorphosis by adapting the continents surface to the representation of diversity.

Figure 4. Anamorphosis – illustration of countries by occurrence of diversity dimensions (drafted by Dörfel et al. Citation2023 – illustrated by C. Enderle (2023)).

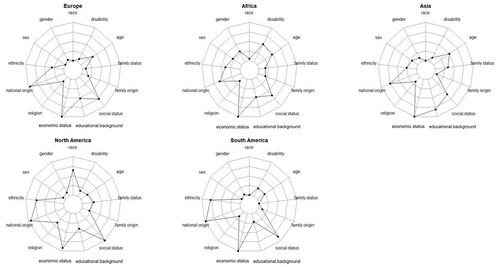

4.2. RQ2

The EVs of the nodes differ between continents (). For Europe, the most central nodes are economic status, social status, and national origin, similar to North and South America. However, comparing the overall pattern, Europe and Asia are alike; both networks have a high or medium centrality in terms of economic status, social status, national origin, educational background, age, and ethnicity. The other nodes are not central, except for medium family status in the Asian network. The centrality in the North and South American networks is also alike; while ethnicity is more central here, race is solely central in North America. In the representation of Africa’s diversity, economic status is the sole central node. Africa has a distinct pattern; the high economic status is sided by medium values in national origin, educational background, social status, age, and disability. Disability is not central in any network. The only commonality in all continents is that three of the external dimensions (economic status, social status, and educational background) are more central than all internal ones (race, ethnicity, age, gender, sex, and disability), except for the national origin.

The network graph of each continent () shows all edges (lines) between the 13 nodes (orange spheres) in the analyzed textbooks:

Europe is characterized by high interconnection of the three nodes’ economic status, national origin, and social status (). The orange circles represent the overlapping nodes, illustrating their high degree of centrality and close interconnection. In the second row, educational background, age, and ethnicity are highly connected. The other dimensions are less connected and often occur more isolated (periphery). Sex only occurs isolated in one code, and race does not occur in the context of Europe at all.

Asia is characterized by five central nodes (economic status, social status, educational background supplemented by national origin, and age), all of which are well interconnected, with economic status located in the middle (). Family status and ethnicity are well connected to this core unit. Sex, gender, disability, religion, and family origin are loosely connected to the network in the periphery. Race occurs only in isolation.

In the representation of Africa’s diversity, economic status is the most central node, which is connected to almost all other nodes. Social status, national origin, educational background, ethnicity, age, and disability constitute a circle around it (). Sex, gender, family origin, religion, family status, and race are outwards. Race is the most distant node.

The North American network is characterized by a core unit of closely connected nodes’ national origin, social status, and ethnicity (). Race, also of medium-high centrality, is more distant, apparently lacking a close connection to national origin. Religion, family status, family origin, and educational background constitute a close part of a half circle, and age, disability, gender, and sex are a more distant part of a half circle around this core unit. Sex is the node with the closest connection to the network.

The core of the South American network can be described as a chain (). Ethnicity, national origin, economic status, and social status are only closely connected to the neighbors in this row but lack interconnectivity between them. Disability, age, educational background, gender, family origin, and religion are loosely connected to this core. Among the outer nodes, only disability and age have an edge. Race, sex, and family status find no mention in the context of South America. An essential difference between the North and South American networks is the generally higher occurrence of all dimensions in North America, resulting in more edges.

5. Discussion

The findings of RQ1 indicated that the frequencies of diversity dimensions vary significantly among countries. The Global North is generally far more represented than the Global South. On examining a continent’s representation of diversity by country, bias is evident across continents. Europe, South America, and North America represented diversity by only one country each – Germany, Brazil, and the US, respectively, with a relative share between 44% and 84%. Asia represented approximately 59% by China (37%) and India (22%). Western European countries account for 90% of the continent’s portrayal versus 10% of Eastern European countries. This finding contradicts the Hessian Curricula as it focuses on Eastern Europe. “The eastward expansion of the European Union is taken into account” (translated from the Hessian Curricula, Citation2021).

Strikingly, Africa is often represented as a whole continent, whereas other regions are differentiated into several countries, thus the homogenization and simplification of African countries in hessian geography textbooks. However, this trend carries a significant risk. According to Hummer (Citation2014), this not only promotes homogenization and simplification but whole false statements. This discrepancy in the depiction of countries in textbooks has previously reported by various textbook analyses, which are trying to classify them to “outer-circle countries” and “inner-circle countries” according to their occurrences (Lu et al., Citation2022). Outer-circle countries, such as African (Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, Tanzania, and Zambia) and Asian countries (Bangladesh, India, Malaysia, Pakistan, Philippines, Singapore, and Sri Lanka), are extremely under-represented (Lu et al., Citation2022). Except for India, this classification applies in this study. Inner-circle (English-speaking) countries are conspicuously highly represented in many analyzed textbooks, such as by Lu et al. (Citation2022), Risager (Citation2021), Toprak & Aksoyalp (Citation2015), Lund (Citation2007), Hong (Citation2009), and Alsaif (Citation2016). Here, this only applies to the US and the UK. This adds to the inconsistency of the inner-circle countries found in prior analyses of different subjects (Xiang & Yenika-Agbaw, Citation2021). Conclusively, the classification of inner-circle countries appears to be dependent on the context, possibly the national background and subject. Furthermore, prior analyses pointed out the over-representation of Western countries (Lund, Citation2007; Risager, Citation2021; Tastan et al., Citation2016) including Westernization (Hong, Citation2009) –for instance the dominance of Western cultures over other cultures (Tastan et al., Citation2016). In this study, the highly represented countries are Germany, China, the US, and India, contradicting this focus on Western countries.

The network analysis pointed out that Europe and Asia exhibit high commonalities in their centrality of represented dimensions, leading to a pattern of representing diversity that differs from the other continents. For both continents, economic status, social status, educational background, and national origin are of similar centrality. Regarding North and South America, despite the varying absolute occurrences, they show similarities between their centrality of represented diversity dimensions, which include the social status, economic status, national origin, and ethnicity. The similarities between Europe and Asia and between North and South America might indicate postcolonial representations leading to othering (Lippert & Mönter, Citation2021; Tastan et al., Citation2016; Zabel, Citation2022). However, Africa cannot be attributed to any of the patterns. It distinguishes itself through significantly lower centrality of educational background and higher centrality of gender and especially disability than other continents. The interconnectedness of disability and economic status in this network analysis was also observed in previous textbook analyses (Xiang & Yenika-Agbaw, Citation2021), resulting in stereotypes due to striking dependence on both dimensions. The differing internal dimensions and their high distribution to one of the continents contribute to the biased representation; race is only pointed out for high centrality in North America respectively the US. In Europe, Asia, Africa, and South America, it is absent (1 or 0 code).

This study has some limitations. First is the quality of the statements regarding diversity dimensions in the textbooks. Since the study focused solely on the occurrence of the dimensions, we did not evaluate their quality – for example, positive economic development statements versus problem-focused statements. In addition, Hessian geography textbooks were analyzed, and statements could not be generalized for Germany directly. Furthermore, textbooks always need to select content and never guarantee a comprehensive representation of the world. Our analysis included all Hessian textbooks and found biases when summing up their content. There was no statement regarding the selection of content of individual textbooks.

In conclusion, the results of the overall occurrence of all dimensions and the network analysis showed a biased representation of the world in the geography textbooks. This representation does not coincide with the concept of superdiversity respectively multi-dimensional representation of diversity. The textbooks failed to provide an adequate view of the world integrating diverse perspectives, which is needed for innovative and functioning societies (Nordström, Citation2008). They simplified the view of our world instead of reflecting superdiverse complex social systems (Vertovec, Citation2007) and do not support students who can deal with multiperspectivity. This may be because the inherent biases in geography textbooks reflect cultural norms Second, simplification and homogenization hinder critical thinking, fostering a sense of superiority among dominant groups and distortion among others. This involves the risk of reinforcing stereotypes and specific and biased images of the world, as Usher (Citation2023) addressed the integration of CMCE with Geography.

This bias may stem from a thematic focus on geography that subordinates the representation of countries to the spatial topics they characteristically exemplify. This adds another risk because teachers and students tend to perceive textbooks as sources of accurate information (Gay, Citation2010; Sleeter, Citation2005), assuming that authors have adequately considered economic, political, and gender issues (Sleeter, Citation2005). If these representations go unchecked, the characteristic examples could lead to stereotyping, thereby failing to meet the requirements of the Hessian curriculum. Different reasons for unbalanced representations have been suggested; Hummer (Citation2014) argues and criticizes the lack of adequate reappraisal of pre-colonial history in the context of representing Africa in textbooks. According to the purpose of this study, we finally want to classify the results as problematic in this context; UNESCO (Citation2017) underscores the importance of diverse identity representation in textbooks in today’s globalized world and Uhlenwinkel (Citation2017) on educating students about global citizenship. This is a bias that needs to be addressed further in both textbook writing and geography education research. This could follow the research approach of scholars such as Lee and Catling (Citation2017), who advocated in their “International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education” contribution for leveraging textbook authors’ expertise to enhance the development of teaching materials and expert training. In our context, this pertains to expertise in diverse geographical subjects and CMCE.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Christiane Enderle for creating the anamorphosis in Qgis.

Disclosure statement

The authors report that there are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alsaif, O. (2016). A variety of cultures represented in English language textbooks: A critical study at Saudi University. Sociology Study, 6(4), 226–244. https://doi.org/10.17265/2159-5526/2016.04.003

- Aping, S., Klein, G., Maraszto, A., Markom, C., Schuller, M., & Steinbauer-Holzer, A. (2022). Narrative und Repräsentationen von Afrika in aktuellen österreichischen Schulbüchern. Wiener Zeitschrift Für Kritische Afrikastudien, 22, 63–92. https://doi.org/10.25365/PHAIDRA.367_05.

- Bloch, F., Jackson, M. O., & Tebaldi, P. (2023). Centrality measures in networks. Social Choice and Welfare, 61(2), 413–453. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00355-023-01456-4

- Brucker, A. (Ed.). (2017). Geographiedidaktik in ubersichten (4. aktualisierte Auflage). Aulis Verlag.

- Canale, G. (2016). (Re)Searching culture in foreign language textbooks, or the politics of hide and seek. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 29(2), 225–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/07908318.2016.1144764

- Cohen, J. (1960). A coeffficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 20(1), 37–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316446002000104

- Cornbleth, C. (2002). Images of America: What youth do know about the United States. American Educational Research Journal, 39(2), 519–552. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312039002519

- Davidson, R., & Liu, Y. (2020). Reaching the world outside: Cultural representation and perceptions of global citizenship in Japanese elementary school English textbooks. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 33(1), 32–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/07908318.2018.1560460

- Dörfel, L., Ammoneit, R., & Peter, C. (2023). Diversity in geography – An analysis of textbooks. Erdkunde, 77(3), 195–212. https://doi.org/10.3112/erdkunde.2023.03.02

- Douglas, A., Roos, D., Mancini, F., Couto, A., & Lusseau, D. (2024). An introduction to R. https://intro2r.com/citing-r.html.

- Federal Government Commissioner for Migration, Refugees, and Integration. (2015). Schulbuchstudie Migration und Integration. https://www.uni-hildesheim.de/media/zbi/Schulbuchstudie_Migration_und_Integration_09_03_2015.pdf.

- Federal Statistic Office. (2023). Bevölkerung mit Migrationshintergrund - Ergebnisse des Mikrozensus 2021 - fachserie 1 reihe 2.2 - 2021 (endergebnisse). Federal Statistic Office.

- Fien, J. (1999). Towards a map of commitment a socially critical approach to geographical education. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 8(2), 140–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/10382049908667602

- Gardenswartz, L., & Rowe, A. (2002). Diverse teams at work: Capitalizing on the power of diversity (annotated edition). Society for Human Resource Management.

- Gay, G. (2010). Culturally responsive teaching: Theory, research, and practice (2nd ed.). Teachers’ College Press.

- Gómez Rodríguez, L. F. (2015). The cultural content in EFL textbooks and what teachers need to do about it. Profile Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 17(2), 167–187. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v17n2.44272

- Gordon, L. R., Menzel, A., Shulman, G., & Syedullah, J. (2018). Afro pessimism. Contemporary Political Theory, 17(1), 105–137. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41296-017-0165-4

- Greaney, V. (2006). Textbooks, respect for diversity, and social cohension. In E. Roberts-Schweitzer, V. Greaney, & K. Duer (Eds.), Promoting social cohesion through education (pp. 47–70 World Bank Publications.

- Greve, W., & Wentura, D. (1997). Wissenschaftliche Beobachtung: Eine Einführung (1st ed.). Beltz.

- Hessian Curricula. (2021). Bildungsstandards und Inhaltsfelder.: Das neue Kerncurriculum für Hessen. Sekundarstufe I - Gymnasien. https://kultusministerium.hessen.de/sites/kultusministerium.hessen.de/files/2021-06/kerncurriculum_erdkunde_gymnasium.pdf.

- Hessian Curricula. (2023). Kerncurriculum gymnasiale Oberstufe. https://kultusministerium.hessen.de/sites/kultusministerium.hessen.de/files/2023-07/kcgo_erdkunde_2022_aktualisierte_version_stand_juni_2023.pdf.

- Hong, W. P. (2009). Reading school textbooks as a cultural and political text: Representations of Asia in geography textbooks used in the United States. Journal of Curriculum Theorizing, 25(1), 86–99. https://journal.jctonline.org/index.php/jct/article/view/HONGREAD.

- Hummer, K. (2014). Die Darstellung Afrikas in Schulbüchern für Geschichte und Geografie [magistra, University of Vienna, Faculty of Philological and Cultural Studies]. University Library. https://doi.org/10.25365/thesis.31545

- Inoue, Y. (2005). Critical thinking and diversity experiences: A connection [Paper presentation]. American Educational Research Association Annual Meeting.

- International Geographical Union. (1992). International charter on geographical education. https://www.igu-cge.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/1.-English.pdf.

- Dalimunthe, R. P., Susilo, S., & Izzuddin. (2021). The portrayal of women in Arabic textbooks for non-arabic speakers. SAGE Open, 11(2),215824402110141. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440211014184

- Jenks, C., Lee, J. O., & Kanpol, B. (2001). Approaches to multicultural education in preservice teacher education: Philosophical frameworks and models for teaching. The Urban Review, 33(2), 87–105. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010389023211

- Kuckartz, U., & Rädiker, S. (2022). Qualitative inhaltsanalyse. Methoden, praxis, computerunterstützung. (5. Auflage). Beltz Juventa.

- Lee, D. M. (2018). Using grounded theory to understand the recognition, reflection on, development, and effects of geography teachers’ attitudes toward regions around the world. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 27(2), 103–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/10382046.2016.1273616

- Lee, J., & Catling, S. (2017). What do geography textbook authors in England consider when they design content and select case studies? International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 26(4), 342–356. https://doi.org/10.1080/10382046.2016.1220125

- Lee, J., Catling, S., Kidman, G., Bednarz, R., Krause, U., Martija, A. A., Ohnishi, K., Wilmot, D., & Zecha, S. (2021). A multinational study of authors’ perceptions of and practical approaches to writing geography textbooks. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 30(1), 54–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/10382046.2020.1743931

- Lippert, S., & Mönter, L. (2021). Building the nation or building society? Analyse zur Darstellung raumbezogener Identität in Schulbüchern gesellschafts-wissenschaftlicher Integrationsfächer. Zeitschrift Für Didaktik Der Gesellschaftswissenschaften, 12(1), 55–78.

- Lu, J., Liu, Y., An, L., & Zhang, Y. (2022). The cultural sustainability in English as foreign language textbooks: Investigating the cultural representations in English language textbooks in China for senior middle school students. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 944381. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.944381

- Lund, R. (2007). Questions of culture and context in English language textbooks: A study of textbooks for the teaching of English in Norway. The University of Bergen.

- Moreau, J. (2003). Schoolbook nation: Conflicts over American history textbooks from the Civil War to the present. University of Michigan Press.

- Nagre, K. (2023). (Mis)educating England: Eurocentric narratives in secondary school history textbooks. Race Ethnicity and Education, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2023.2192945

- Nakazawa, M. (2023). Functions for medical statistics book with some demographic data. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=fmsb.

- Newman, M. E. J., Barabási, A. L., & Watts, D. J. (2006). The structure and dynamics of networks. Princeton studies in complexity. Princeton University Press.

- Nordström, H. K. (2008). Environmental education and multicultural education - Too close to be separate? International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 17(2), 131–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/10382040802148604

- Picton, O. J. (2008). Teaching and learning about distant places: Conceptualising diversity. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 17(3), 227–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/10382040802168321

- Risager, K. (2021). Language textbooks: Windows to the world. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 34(2), 119–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/07908318.2020.1797767

- Sleeter, C. E. (2005). Un-standardizing curriculum: Multicultural teaching in the standardized-based classroom. Teachers College Pr.

- Sleeter, C. E., & Grant, C. A. (2007). Making choices for multicultural education: Five approaches to race, class and gender (6.th ed., Vol. 54). John Wiley & Sons.

- Stoicovy, C. (2002). A case for culturally responsive pedagogy. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 11(1), 80–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/10382040208667470

- Tabatadze, S. (2015). Teachers’ approaches to multicultural education in Georgian classrooms. Journal for Multicultural Education, 9(4), 248–262. https://doi.org/10.1108/JME-07-2014-0031

- Tabatadze, S., & Gorgadze, N. (2023). Analysis of language textbooks in Georgia: Approaches to gender equality of males and females while teaching languages. International Journal of Educational Reform, 32(2), 169–188. https://doi.org/10.1177/10567879221147011

- Tabatadze, S., Gorgadze, N., Gabunia, K., & Tinikashvili, D. (2020). Intercultural content and perspectives in school textbooks in Georgia. Intercultural Education, 31(4), 462–481. https://doi.org/10.1080/14675986.2020.1747290

- Tajeddin, Z., & Pakzadian, M. (2020). Representation of inner, outer and expanding circle varieties and cultures in global ELT textbooks. Asian-Pacific Journal of Second and Foreign Language Education, 5(10), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40862-020-00089-9

- Tastan, C., Gür, B. S., & Celik, Z. (2016). Eurocentrism in higher education in Turkey: Locality and universality in textbooks on sociology of education. Eurocentrism at the margins (pp. 121–134). Routledge.

- Toprak, T. E., & Aksoyalp, Y. (2015). The question of re-presentation in EFL course books: Are learners of English taught about New Zealand? International Journal of Society, Culture, & Language, 3(1), 91–104. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3590259.

- Uhlenwinkel, A. (2017). Enabling educators to teach and understand intercultural communication: The example of “Young people on the global stage: Their education and influence”. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 26(1), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/10382046.2016.1217078

- UNESCO. (2017). Making textbook content exclusive: A focus on religion, gender, and culture. Education 2030. United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization. http://repository.gei.de/handle/11428/265.

- Usher, J. (2023). Africa in Irish primary geography textbooks: Developing and applying a framework to investigate the potential of Irish primary geography textbooks in supporting critical multicultural education. Irish Educational Studies, 42(1), 123–143. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2021.1910975

- Vertovec, S. (2007). Super-diversity and its implications. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 30(6), 1024–1054. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870701599465

- Xiang, R., & Yenika-Agbaw, V. (2021). EFL textbooks, culture and power: A critical content analysis of EFL textbooks for ethnic Mongols in China. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 42(4), 327–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2019.1692024

- Young, M., & Lambert, D. (2014). Knowledge and the future school: Curriculum and social justice. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Zabel, J. (2022). Eurozentrismus im Schulbuch: Eurozentrische Diskurse und Kolonialität(en) in deutschen Schulbüchern für den Spanischunterricht. Kölner Online Journal Für Lehrer*Innenbildung, 6, 152–170. https://doi.org/10.18716/OJS/KON/2022.2.9.

Appendix

Table A1. All licensed geography textbooks in Hesse (status: 2022) (Dörfel et al., Citation2023).