ABSTRACT

People with disability have demanded the recognition of full legal personhood in order to realise their rights and to overcome dominance and oppression. Legal personhood is also being claimed for similar reasons for natural entities, including rivers, forests, and mountains. However, the prevailing neo-liberal understanding of legal personhood relies on the individual exercising personhood independently. This may not be enough to secure the interests and realise the rights of people with disability, natural entities, or other cohorts that are not experiencing a wealth of power and privilege. In this article, we attempt to overcome centuries of (white, able-bodied, cis gender) male centric theory of legal personhood. We reject the dominant conceptions of personhood from liberal political theory that emphasise an atomistic, isolated individual making independent decisions. Instead, we argue for a different conception of legal personhood – relational personhood. We use insights from feminist theories of relational autonomy as well as the experience of disability to help us re-conceptualise personhood to embrace exercising autonomy through a collaborative process of acknowledging, interpreting and acting on an individual’s expressions of will and preference. We then apply this new conception to the recognition of legal personhood in nature and explore how natural entities can exercise their personhood via their relationships with humans – and, in particular, Indigenous Peoples, who have developed close relationships with natural entities over centuries. Our aim is to demonstrate the utility of a conception of legal personhood that encompass the reality of the interdependence of all individuals and entities.

I. Introduction

For much of history, in Europe and jurisdictions heavily influenced by European colonisers, legal personhood largely only included white, able-bodied, heterosexual, cis gender men.Footnote1 In some places, it also required land ownership.Footnote2 Legal personhood has, fortunately, broadened significantly over time. This expansion of legal personhood was, at least in part, due to the emergence of liberal political theory, which began to advocate for freedom and equality for all individuals.Footnote3 However, the bulk of liberal political theorists have also been white, European, able-bodied, heterosexual, cis gender men and their work has been created through the lens of that generally privileged experience.Footnote4 This lens led them to view individuals as atomistic actors that operate independently and are largely self-interested.Footnote5 This perception is problematic because it disregards the relationships that are critical for flourishing – such as spouses, partners, friends, cooks, cleaners, childcare providers, doctors, fellow community members, and others. If these people were considered, it would become clear that even white, able-bodied, heterosexual, cis-gender men are not atomistic actors – in fact, we all rely heavily on others and frequently make decisions that are influenced by these other actors and their needs. In addition, self-interest is often superseded by the needs of these actors or others that are either dependents or are highly influential on us. For these reasons, while liberal political theory has expanded the definition of legal personhood by prioritising freedom and equality – it has also limited it by not recognising the inherent interconnectedness of all entities.

This liberal political understanding of legal personhood has been widely influential. For example, in most jurisdictions, legal personhood can be denied if an individual cannot demonstrate that they can make decisions independently.Footnote6 This understanding of personhood has disproportionately disadvantaged women, people with disability and other minority groups and entities who routinely rely on interdependent relationships with others to make and enforce decisions.Footnote7 It has also, arguably, disadvantaged everyone by creating a legal system that is not equipped to manage the reality of the interdependence of all people.

Natural entities are similarly disadvantaged by this liberal political definition of legal personhood. The environment – including natural entities like lakes, rivers, and mountains, as well as individual plants and animals – has traditionally been constructed as a legal object, with no rights or powers of its own. A legal object is not visible and legible to the law in the same ways that a legal person or legal subject is.Footnote8 As Christopher Stone noted back in 1972, this meant that the law struggled to ‘see’ impacts to the environment unless those impacts also affected the interests of legal persons (human or otherwise).Footnote9 Although changes to standing requirements in environmental law have somewhat diminished this problem,Footnote10 because almost all natural entities remain legal objects in the vast majority of jurisdictions, they have no enforceable rights of their own. At best, the law can limit the actions of others in an attempt to protect the environment, but this does not recognise or protect the rights of nature to exist and flourish. Without legal personhood, Nature is legally weak, and cannot protect itself against the actions of humans, or other legal persons such as corporations. As we enter the Anthropocene, and human impacts on the environment take on a global scale, the lack of legal personhood and a level playing field between the interests and rights of humans and nature is growing ever more alarming.

In this article, we aim to address some of these issues. We propose a conception of legal personhood that emerged from discussions that began at a workshop on legal personhood at Melbourne Law School in August 2019, which brought together scholars exploring legal personhood in both disability rights and environmental law.Footnote11 We develop a working theoretical framework for how legal personhood can be conceptualised in a way that overcomes centuries of (white, able-bodied, cis gender) male centric theory of legal personhood. We reject the dominant conceptions of personhood from liberal political theory that emphasise an atomistic, isolated individual making independent decisions. Instead, we use insights from feminist theories of relational autonomy as well as the experience of disability to help us re-conceptualise personhood to embrace exercising autonomy through a collaborative process of acknowledging, interpreting, and acting on an individual’s expressions of will and preference. We then apply this new conception to the recognition of legal personhood in nature and explore how natural entities can exercise their personhood via their relationship with humans – including Indigenous Peoples, who have developed intimate relationships with natural entities over centuries. Our aim is to demonstrate how a conception of legal personhood that encompass the reality of the interdependence of all individuals and entities can ensure that historically marginalised cohorts can overcome relationships of dominance and finally secure their rights.

II. Problematic parallels between the legal personhood of people with disability and natural entities

It is important to emphasise that we are not drawing parallels between the legal personhood of people with disability and natural entities.Footnote12 Instead, we are identifying that the recent developments in understandings of the right to legal personhood in relation to disability have demonstrated the significance of feminist theories on the inherently relational reality of autonomy. We are then arguing that these theories are relevant, and important, in the context of the legal personhood of nature because they provide a new lens through which to view personhood – a lens that sees personhood as an individual right that may be exercised by the individual or entity in collaboration with others.

In addition, disability is an important lens for legal personhood because the 2006 United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) is the first human rights instrument to explicitly recognise the relational reality of personhood. It establishes state obligations to provide access to support for the exercise of legal personhood and to ensure safeguards for the will and preferences of the individual (Article 12(3 and 4)). In this way, it has created a recognition of relational personhood in international human rights law, which can be applied to other humans and – potentially – other entities, such as natural entities.

Disability also illuminates the relational reality of autonomy because people with disability are often disproportionately dependent on others. However, disability does not inherently cause dependence. It is often inaccessibility, exclusion, and social marginalisation that results in people with disability being dependent on othersFootnote13 – including when exercising legal personhood via legal decision-making. For example, although there are more than 70 million deaf people around the world who use sign languages to communicate, they are not routinely taught across our education systems.Footnote14 The result is that deaf people are dependent upon sign language interpreters to participate in society. When exercising legal personhood – making legal decisions – they will likely need to involve at least one additional person to effectively communicate their will and preferences to other parties. In this example, it is not being deaf that causes dependence on others for legal decision-making. It is social marginalisation and a lack of accessibility that causes this dependence. As discussed earlier, we argue that legal personhood is always relational, and all people use some form assistance in exercising legal personhood – because that is the nature of our highly social society.Footnote15 However, people with disability are more frequently required to use assistance in exercising legal personhood and therefore the context of disability presents a useful lens through which to examine legal personhood as a relational concept.

The reason that we must further emphasise that we are not drawing parallels between people with disability and nature is that there is a long history of people with disability being dehumanised. For example, the label of ‘invalid’ has led to law, policy, and practice that has allowed for the institutionalisation, forced sterilisation, impoverishment, and disregard for the lives of people with disability.Footnote16 This has been occurring for centuries and remnants can be seen in modern law, policy, and practice.Footnote17 Disability scholar, Dan Goodley noted that:

The valued citizen of the twenty-first century is cognitively, socially and emotionally able and competent. Biologically and psychologically stable, genetically and hormonally sound and ontologically responsible. Hearing, mobile, seeing, walking. Normal: sane, autonomous, self-sufficient, self-governing, reasonable, law-abiding and economically viable.Footnote18

A particularly poignant example of the dehumanisation of people with disability is their treatment during the eugenics era and the following holocaust that occurred under the Nazi regime in Germany.Footnote20 Momentum in the eugenics movement began largely in the United States and England during the first half of the twentieth century. Medical professionals, scientists, and others were strongly advocating for the eradication of impairment – along with all qualities that they determined were a deviation from the able-bodied white-Aryan standard that they decided was the ‘norm’. Through various methods, that ranged from institutionalisation to forced sterilisation and forced medical experimentation, the eugenics movement dehumanised people with disability and was a strong motivating factor for the mass murder of people with disability as part of the holocaust – a fact which is often overlooked in discussions of the holocaust.Footnote21 We give this unfortunate history in order to demonstrate the profound importance of not drawing parallels between people with disability and any non-human object. It risks further marginalisation.

We also acknowledge that the recent transnational movement to recognise rivers and other natural entities as legal persons and/or living beings can result in situations in which natural entities have legal personhood in ways that continue to be denied to people with disability. For example, in Uttarakhand, India, the state High Court has ruled that:

… rivers, streams, rivulets, lakes, air, meadows, dales, jungles, forests wetlands, grasslands, springs and waterfalls [have] the status of a legal person, with all corresponding rights, duties and liabilities of a living person.Footnote22

We strongly acknowledge that people with disability are entitled to a right to legal personhood on an equal basis with other humans. We are leaving aside, in this article, the debate about whether natural entities should also be recognised as legal persons. That discussion is, and should be, a separate debate. Here, we are simply exploring whether the insights gained from disability rights can illuminate new ways forward in recognising legal personhood for nature and utilising the knowledge and experience of those in close relationships with nature to exercise the autonomy and decision-making power that is an inherent part of that personhood. Ultimately, the dehumanisation of people with disability, and the ‘othering’ of nature and natural entities, although foundationally and essentially different, both underscore the problems of domination. As Stone argued, an object is a thing, ‘less than a person’ in both moral weight and legal power, and the recognition of legal personhood is an opportunity to level the playing field and reinstate a power balance.Footnote25

III. Domination, paternalism, and othering in the recognition of legal personhood

Dominance has many different meanings and its precise boundaries have been debated by many theorists from many different disciplines. For example, in political theory, the concepts of dominance and non-dominance have been a preoccupation of neo-republican theorists.Footnote26 They have generally defined it as arbitrary interference with the individual – accentuating physical interreference or threat of physical interference without a justification such as imminent harm or criminal behaviour. They have highlighted non-dominance as essential for liberty and freedom.Footnote27 Similar definitions of dominance in social psychology have identified that it can erode an individual’s ability to participate in community and public life – and that it carries significant psychological implications.Footnote28 Political scientists have argued that dependency can breed such domination.Footnote29 Adding more nuance, social and political theorists have argued that a definition of dominance that primarily considers control over the individual or entity from an intentional and physical perspective – consistent with the ideas of many neo-republican political theorists – is grossly underinclusive because it does not take into account the vast amount of domination that takes place via social and psychological means that are often unintentional. This domination may occur through discrimination, marginalisation, social exclusion, and other insidious and intangible methods.Footnote30 Most constructions of the concept of dominance encompass both the experiences of people with disability and the relationship that humans have with nature. This dominance is negative due to the inherent lack of power of one party and the inherent inability of that party to reframe their situation or to seek redress if the party in the position of dominance exerts their power over them.Footnote31

A. People with disability

In the context of disability, domination occurs via physical means as well as social and psychological means.Footnote32 This domination is often the result of dependence on others, which is often caused by social marginalisation, as discussed above. Physical dominance is often experienced by people with disability due to bodily dependence on others that is sometimes a result of biological factors, but more frequently is a result of inaccessible physical spaces. For example, a lack of accessible public toilets forces some people with disability into potentially dangerous situations of physical dependence on others.Footnote33 Physical dominance can also occur due to physical dependence on the state. For example, people that live in institutional settings that are owned and managed by the state; people that are wards of the state; and people with mental health disability who are subjected to mental health laws that specifically allow for bodily interference of people with mental health disabilities. These situations place decisions about the individual’s body and environment in the hands of the state. These situations can propagate particularly profound physical dominance because to escape such dependence on the state, you must overcome an entire governing body and bureaucracy. People with disability are also often socially and psychologically dependent due to prejudice, marginalisation, and oppression. For example, the social world is sometimes so hostile to people with disability that they become socially isolated. In these situations, the few relationships that people with disability build are at risk of becoming relationships of dependence because of the rarity of their existence. In these ways – and in many others – people with disability are experiencing marginalisation and domination.

In addition, some relationships of domination that people with disability experience are created and perpetuated by specific legal measures that remove the legal personhood of people with disability. These measures can create relationships of both physical dominance as well as social and psychological dominance. For example, due to ableist notions that de-value the decision-making skills of people with disability, many jurisdictions have purportedly objective legal measures that subject people with disability to alternative forms of decision-making that include decisions being imposed upon them either regarding a particular decision, particular areas of decision-making, or to all their decisions. For example, guardianship, conservatorship, interdiction, and other such measures can be imposed in a limited fashion to constrain the legal personhood and agency of an individual with disabilities, or, in some jurisdictions, they can be used to wholly remove an individual’s legal personhood and vest their decision-making power in another individual or in the state. These legal mechanisms create relationships of dominance between the individual with disabilities and the state or other actor that is vested with their decision-making power – the individual with disabilities is subordinated because their decision-making power is removed.Footnote34

There are also mechanisms in most criminal justice systems that divert people with disability into a separate – often less rights-protective – justice system. For example, ‘unfitness to plead’ laws that are used to determine that an individual cannot participate in a trial or in his own defence. These laws are usually applied to people with cognitive disability and/or mental health disability. They are often purported to protect individuals with disabilities from being forced to participate in legal proceedings. However, in many jurisdictions, there is evidence to indicate that they are used disproportionately for racial minorities and Indigenous Peoples and that they often result in the individual being diverted into a much less preferable situation in which they may be held in prison indefinitely or for significantly longer than if they had been convicted of the crime that they were charged with.Footnote35 These are only a few examples of how the legal personhood of people with disability is routinely denied and they are subjected to relationships of dominance in which they lack the power to enforce their own wishes or make decisions in their lives. The impact of these denials of personhood is profound and far reaching – it decreases the individual’s power and privilege significantly and can result in bodily interference, psycho-social disempowerment, among other effects of decision-making denial.

It is important to note, that not all people with disability are experiencing domination and marginalisation. There are, of course, people with disability that enjoy a wealth of social capital and minimal dependence – either physically, socially, or psychologically – on others or on the state. However, the unfortunate history of poor treatment of people with disability has resulted in many experiencing high levels of dependence and relationships of domination. This dependence and domination is often a result of the legal personhood of the individual being denied or curtailed – as described above – which has necessitated the emergence of the fight to secure the right to legal personhood for people with disability.

B. Nature and natural entities

Categories of legal person have expanded over time to explicitly include women, children, persons with disabilities, as well as ‘fictional’ persons such as corporations.Footnote36 However, the central hierarchy of law has gone unchallenged. Legal subjects matter more than legal objects, and the natural world has largely retained its status as merely a legal object. Even the advent of environmental law since the 1960s, ‘a massive upwelling of layer upon layer of substantial public and private law doctrines, almost volcanic in the power and mass of its eruption’Footnote37 which recognised the environment in law as a socio-ecological concept,Footnote38 did not fundamentally alter the status of nature as ‘other’: a legal object under the dominion of humans, and separate from us.Footnote39 Modern environmental law continues this tradition of dominion and disconnection by ‘assum[ing] that we can isolate and control elements of the natural world as we choose’.Footnote40

The nature/human duality is also a particular cultural framing in which ‘agency has erroneously become exclusive to humans, thereby removing non-human agency from what constitutes a society’.Footnote41 Vanessa Watts argues that the very foundation of ‘Euro-Western’ understandings of the world, what she terms the ‘epistemological-ontological divide’, artificially separates theory from place and practice, and leads to ‘an exclusionary relationship with nature’.Footnote42 In settler colonial states, this conceptual framing of the world, in combination with the invasion and theft of Indigenous peoples’ lands, has contributed to the erasure of both the ongoing role of Indigenous peoples in creating and caring for Country,Footnote43 but also of Indigenous cosmologies which recognise that ‘all elements of nature possess agency’.Footnote44 In acknowledging this, we also recognise that there is no such thing as a ‘pan-Indigenous’ cosmology, and that the laws and cultural protocols of each Nation/Tribe/Clan group are specific to both people and place.

Almost fifty years ago, in 1972, Christopher Stone’s provocative paper posed an ‘unthinkable’ question for Euro-Western law: what if, instead of remaining a legal object, nature could be the subject of legal rights and legal personhood? In order to do so, Stone argued that nature required three things: ‘first, that [it] can institute legal actions at its behest; second, that in determining the granting of legal relief, the court must take injury to it into account; and, third, that relief must run to the benefit of it’.Footnote45 In Stone’s argument, granting legal rights (and legal personhood) to nature was explicitly framed as a way to address the domination and othering of nature, by making it as visible to the law, and as able to act in law, as human persons and corporations.

Although Stone’s argument has been influential,Footnote46 it failed to stimulate significant legal change for almost forty years. The concept of ‘nature’ as a legal subject with rights languished on the fringes of environmental law until the mid-2000s, when local ordinances recognising natures’ rights began being passed by communities in the USA.Footnote47 In 2008, the issue gained global traction with the creation of the new Constitution in Ecuador, which granted nature specific rights. In 2011, these rights were put to the test in the case of the Río Vilcabamba, in which the court recognised the right of the river to be protected from the impacts of road construction.Footnote48 By the mid-2010s, the legal approach to the ‘rights of nature’ began to shift away from recognising a universal construct of nature in totality, and instead began to focus on specific natural entities. Broad rights of nature continue to be pursued in a number of jurisdictions, but there is a growing transnational movement to recognise rivers and other landscape features (natural entities) as legal persons, legal subjects, and/or living entities.Footnote49 The earliest example of this shift comes from Aotearoa New Zealand, which granted legal personhood to the Te Urewera National Park, as part of a treaty dispute settlement with Māori.Footnote50 In 2017, Te Urewera was joined by Te Awa Tupua (the Whanganui River),Footnote51 and then by the Ganga and Yamuna Rivers in Uttarakhand, India,Footnote52 and the Río Atrato (Atrato River) in Colombia.Footnote53 By 2020, Lake Erie in the USA had gained and lost legal rights,Footnote54 and all rivers in Bangladesh were recognised as legal persons and living entities.Footnote55 In the USA, Tribes are also recognising nature’s rights in various ways within their own jurisdictions – for individual species (such as manoomin/wild rice),Footnote56 rivers (the Klamath River),Footnote57 and nature as a whole.Footnote58 Again, it is important to note that ‘rights of nature’ as expressed in settler state law, while they may attempt to embody and reflect the laws and cultural protocols of Indigenous peoples, are a Euro-Western interpretation or translation of Indigenous laws and cultural protocols, and often only a weak form of legal pluralism.Footnote59

As rights of nature have become more widely enacted, the reasons for doing so have likewise diversified. Whilst environmental protection remains a key driver (and was explicitly cited by courts in Uttarakhand and Bangladesh), the relationship between people and nature as a reason to recognising nature’s rights is emerging more strongly, as seen in Māori concepts of kaitiakitanga (which can be loosely although not completely understood as guardianship) and the explicit recognition by the courts that protecting the rights of people depends on protecting the rights of the environment.Footnote60 In Aotearoa, it is also important to see the recognition of natural entities as legal persons in the context of treaty dispute settlements: the use of this legal tool was explicitly employed as a form of circuit breaker in negotiations to enable the natural entity to ‘own’ itself, rather than continue to be ‘owned’ by either the New Zealand government or Māori.Footnote61

Although the rights of nature, in various forms, are increasingly recognised in a growing number of jurisdictions, threshold questions remain.Footnote62 How can these rights be given force and effect? Who speaks for nature? How do we even know what natural entities ‘want’? The issue of representation is emerging as a crucial issue for law in supporting the realisation of legal personhood for nature.Footnote63

C. Relational personhood to combat dominance

Similar to neo-republican theorists, we are arguing that autonomy is essential for combating such relationships of dominance.Footnote64 However, we are also drawing on moral philosophy and feminist theory, including the work of Indigenous scholars, to argue that the concept of isolated autonomy is not enough – that the idea that autonomy must be exercised individually is biased towards (white) men, is illusory, and is unproductive.Footnote65 It is biased towards white men because it is based on a history of male decision-makers subjugating others, largely women (and men of colour), and ignoring the contributions that these subjugated ‘others’ make that are essential for the effective decision-making of men. This is exemplified in the support required for an individual’s health, wellbeing, and home to run smoothly in order to create the space for decision-making. It is illusory because the reality is that we are all intertwined, and our decisions are dependent upon the decisions of one another – both because we all require support in multiple areas of our lives in order to have space to make decisions and because even our thoughts are not wholly independent thoughts – they are continually influenced by others and shaped by our experiences and relationships with others (including the world around us). If this relational aspect of autonomy is not recognised, seeking ‘independent’ autonomy is unproductive because you are seeking something that does not exist and is impossible to accomplish.

We are arguing that the recognition of legal personhood is essential for the recognition of an entity’s autonomy and for the freedom for that entity to exercise that autonomy. We are also arguing that the recognition of an individual’s personhood and autonomy are essential for overcoming relationships of dominance with both other individuals, legal entities, as well as the state. Finally, we are arguing that the recognition of personhood and autonomy only has the power to overcome dominance if it is conceived of as shared – if there is an understanding that we simultaneously exist as both individual entities and as part of a whole. Our personhood and autonomy are our own, but they are also intricately tied to those around us and the systems that we live within. This is true for every entity. However, it may be particularly important in the context of disability, nature, and other historically marginalised individuals and entities that have experienced profound domination by other individuals, groups, and entities.

In this section, we have explored the ways in which formal recognition of legal personhood has been an important step for both people with disability and natural entities in pushing back against entrenched modes of dominance and dependence. However, we have also highlighted the continued necessity of relying on others to give full effect to personhood in different contexts. Making sense of this apparent tension between independence and reliance on others requires us to acknowledge that autonomy is inherently relational.

IV. Relational autonomy as a means of expressing legal personhood

Toward the end of the last century, a historical discussion re-emerged within the anthropological community debating the concept that personhood is a relational as opposed to an individual construct. This discussion emerged from a desire of feminist theorists and anthropologists to address Geertz’s claim that the ‘Western conception of the person is … a rather peculiar idea within the context of the world’s cultures’.Footnote66 These discussions primarily centred around Confucian and Buddhist concepts of personhood, whereby the individual is seen as existing in relation to and inextricably bonded with ‘the other’.Footnote67 The family, community or village is seen as central to the person.Footnote68 These scholars argue that the individualised (as opposed to collective) self is a western postmodern construct and is not generally desired in more socially interdependent cultures. Adopted by feminist theorists, the concept of relational personhood or relational autonomy was born, promoting the idea that it is ‘the group’ that shapes the personhood and personal identity of an individual.Footnote69 Moreover, it is ‘the group’ that supports, and collaborates with the individual to achieve personal agency, a concept at the heart of personhood.

These concepts are also reflected in Article 12 of the CRPD. Paragraph 3 of Article !2 requires that state parties to the convention provide access to support for the exercise of legal capacity. This paragraph is the first time that a human rights instrument has explicitly acknowledged that legal personhood is relational – that we all exercise our personhood in relation to those around us. Paragraph 4 also requires that any mechanisms related to the exercise of legal personhood must respect the rights, will and preference of the individual. This is revolutionary because it recognises that the right to legal personhood and agency is an individual right and that the individual is entitled to protection for his or her will and preference. However, it is simultaneously recognising that legal personhood can be exercised via relationships with others – and that there is a state obligation to ensure that every individual has access to such relationships. This goes beyond the conception of relational personhood identified by the anthropological community, because it embraces the western concept of an individual right to personhood – however, it requires recognition that individual personhood is inherently relational. This revolution has significant implications for marginalised communities because they are the individuals who often utilise support for the exercise of legal personhood (often because their marginalisation and domination has left them in positions without individual power and a need to depend on others, as described above). In addition, the effective use of such support has the potential to elevate marginalised groups by facilitating their exercise of legal personhood and, thereby, potentially mitigating some of the dominance that they are experiencing. In these ways, ‘relational personhood’ has the power to achieve greater equality for marginalised groups.

A. People with disability

A focus on this notion of relational personhood and autonomy highlights the need not only to explore the role of the ‘other’ in realising an individual’s personhood, but the nature of the relationship between individuals. As we acknowledged above, the mere dependence of a person with disabilities on others (either because of severe disabilities, or through a combination of disability and socially constructed constraints) can give rise to situations of dominance, leading to disempowerment and dehumanisation. One of the reasons for this is inherent to the concept of ‘guardianship’ and its assumption that the guardian can act in the best interests of the individual. By articulating those ‘best interests’ as distinct from the will and preference of the individual, guardians are encouraged to substitute their interpretation of the best interests of their wards. This substitution becomes especially likely in situations where communication between guardian and ward is extremely limited, such as in cases of severe physical and/or intellectual disability. As Watson and colleagues noted:

when a person with severe or profound intellectual disability’s right to personhood is respected, the very practical issue of communication challenges for people with severe or profound intellectual disability remains. These challenges exist specifically in relation to having their expressions of preference acknowledged, interpreted and ultimately reflected in decisions made about them.Footnote70

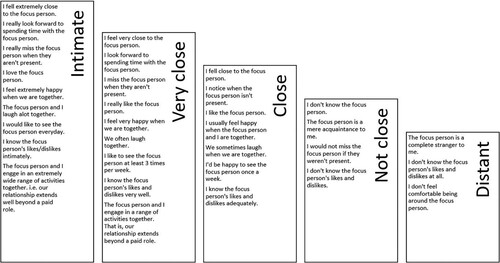

Figure 1. Continuum of relational closeness (Watson et al Citation2017).

Watson et al. found that there was a strong link between communicative responsiveness and relational closeness, and that this played an essential role in the realisation of autonomy and legal personhood for human beings, particularly those with severe cognitive disability.Footnote73 At the centre of these findings is the notion that a person’s autonomy and therefore personhood is heavily reliant on the ability of other(s) to respond to a person’s expression of will and preference. Watson et al characterise responsiveness as a complex process made up of several distinct tasks, including the ability to acknowledge, interpret and act on communication in multiple forms (verbal, behavioural, and via body language). Supporter responsiveness is most likely to be highest in relationships characterised as ‘intimate’, as this enables the supporter(s) to develop an understanding of the multiple forms of communication, particularly when these are non-verbal. Watson et al describe the actions of responsive supporters of individuals with disabilities as follows:

Supporters acknowledge/notice, as opposed to ignore, expressions of preference; they interpret these expressions of preference, assigning meaning to them; and they act on this meaning.Footnote74

It is via this focus on determining the will and preference of the focus person by supporters, that people with severe or profound intellectual disability can achieve decisions that encompass their preferences.Footnote75

In addition, Watson et al focus on the role of the supporter(s) as the key component that is ‘amenable to change’, as opposed to the expression of preference by the individual with disability. This not only removes the burden of doing additional work to give effect to their own personhood from the shoulders of the person with disability, but is also consistent with a social model of disability, where the ‘onus of change is not on the person with a disability, but rather, the environment of which they are a part’.Footnote76 Watson’s work has also included the creation of training packages to further assist supporters in harnessing their relational closeness to become effective and responsive supporters of decision-making by people with disability.Footnote77 This emphasis on the role of supporters also points to a role for the state in ensuring that people with disability can give effect to their full legal personhood. Given the central importance of relational closeness and circles of support to the expression and implementation of an individual’s will and preference, it becomes incumbent on the state to enable and support relational closeness as a key strategy for legal personhood.

This body of work provides a strong basis for the important role a close and responsive relationship may play in realising legal personhood not only within the context of human relationships, but also those between humanity and nature. Just as an exploration of relational closeness between people with severe intellectual disability and those close to them has revealed a pathway to legal personhood for people traditionally denied such status, so too may an exploration of the relationship between humanity and nature.

B. Nature and natural entities

Recognising natural entities as legal persons and the subject of legal rights increases their legal powers, whilst at the same time, collapsing the notion of a mountain, a river, a national park, a non-human species, or all of nature into an atomistic, individual actor within the Euro-Western legal framework. Mary Graham describes this unmoored state as the ‘fearful freedom’ of the individual, in which each ‘discrete individual then has to arm itself not just literally against other discrete individuals, but against its environment’.Footnote78 Giving force and effect to the legal rights of nature thus requires institutional capacity (organisation, funding, human resources) to ensure that the rights of nature are defended from encroachment. However, mere capacity to perform these functions will not be sufficient to genuinely represent the interests of natural entities in Euro-Western legal frameworks. As we explored above, autonomy and personhood are dependent on the person’s will and preference being understood by others. As Vanessa Watts explains, ‘it is necessary to tease out what the land’s intentions might be, and how she tries to speak through us’.Footnote79

Although we acknowledge the important distinctions between natural entities and human persons, the findings from Watson and colleagues’ work with persons with disabilities described above are also significant for the rights and personhood of natural entities. Watson and colleagues position the relationship between the person seeking agency, and the individual or group supporting them to realise it, as fundamental to legal personhood. So then, what are the ideal characteristics of this autonomy enhancing relationship, and how can they be replicated within the context of the relationship between humanity and the natural world?

At the centre of Watson and colleagues’ findings is the notion that a person’s autonomy is reliant on a supporter (representative) or support network’s ability to embark on a complex process of responding to that person’s expression of will and preference. As described above, this process of responsiveness can be understood as three distinct tasks: acknowledgment of an expression of will and preference, interpretation of that expression, and finally, the acting on that interpretation. Responsiveness depends on a high degree of intimacy in the relationship between the autonomy seeker and their support network, which is most likely to be present when several key conditions are met.

One of these conditions is a relationship that exists physically, in a person’s physical presence, acknowledging the importance of the ‘here and now’. The idea of relational closeness being rooted in the ‘here and now’ resonates with what Mihnea Tănăsescu describes as the ‘ontological relationality’ of place-based Indigenous cosmologies.Footnote80 He further describes this concept by saying:

[i]n relational ontologies it is this land, here and now, specific to a location and a people, that acts and is therefore given voice through particular partnerships with particular people, who themselves take their character from the land.Footnote81

Another condition of relational closeness that Watson and colleagues found to be essential to supporting autonomy was a genuine sense of reciprocity, and the notion that a relationship is mutually beneficial. Watson (Citation2016) found that where a supporter and the person being supported appeared to enjoy one another’s company on an equal basis, the supporter/representative was more likely to be responsive to the person’s expression of will and preference, in terms of their acknowledgment, interpretation and action. Linda Te Aho, writing explicitly of Māori cosmologies, explains that for Māori, ‘rivers are inextricably linked to tribal identities’.Footnote82 Tikanga (laws and practices) ‘recognised that if the people care for the river, the river will continue to sustain them’,Footnote83 introducing elements of both agency and reciprocity into the relationship between people and rivers, which echo ideas reflected in Watson and colleagues’ research.

There are two immediate implications of relational autonomy (and the corresponding need for relational closeness) for giving effect to the rights of nature. Firstly, the relationship must be specific, between nominated individuals and local, place-based understandings of nature. In the case of Ecuador, the rights of nature created in the Constitution ‘encourage the inauguration of nature as a legal person who, by virtue of its intrinsic characteristics, can have a representative relationship with anyone’.Footnote84 As a result, it is difficult (if not impossible) to avoid the problem of substituting the representative’s will and preference for that of the natural entity. Kauffman and Martin, in their analysis of the successful government-initiated ‘rights of nature’ cases in Ecuador note that:

[s]ometimes, these [cases] are motivated by instrumental policy considerations directed by President Correa, while other times the Ministry of Environment simply invokes [rights of nature] to justify routine administrative actions.Footnote85

In Colombia, the court acknowledged the special relationship between the communities along the Río Atrato, and that these communities received special protections in Colombian law (due to their status as Indigenous peoples, or descendants of former slaves). Although the court originally nominated the Ministry for Environment as the guardian of the river, the appointed river guardians now include one man and one woman from each of the seven villages along the river, reflecting the deep and ongoing relationships between the river and the people who live along it.Footnote90

The second implication of relational autonomy for rights of nature is that this relationship should be active and contemporaneous, as a ‘particular connection with the land is as good as the practices that keep it alive’.Footnote91 For Indigenous peoples, the processes of colonisation interrupt ‘our ability to communicate with place’.Footnote92 Although the history of the relationship remains, colonisation can erode awareness and understanding of laws and cultural protocols, so that this communication and understanding of the land’s agency must in some cases be re-learned and re-activated. In the case of Te Urewera, the supporting strategy document, Te Kawa o Te Urewera, ‘sets out from the beginning to be a philosophical guidebook in finding one’s way in building [and re-building] relationships with the natural world’.Footnote93

As the examples from Aotearoa and Colombia demonstrate, there is a role for the law in defining, and supporting, the specific, active relationships between people and nature, and emphasising relational closeness as the necessary element for giving full effect to legal personhood for nature. Tănăsescu argues that:

the Te Urewera Act constitutes, in my view, the most significant innovation in nature’s representation so far, precisely because of the minimalist grant of legal entity status and the determined focus on representative arrangements. Te Urewera, in contrast to nature’s rights in Ecuador, is a particular place that enters into anthropomorphic relations with particular people, now potentially empowered to reinvent future relationships which can unsettle the definition of what constitutes a human as much as what constitutes ‘nature’.Footnote94

V. Relational personhood: a new conception of legal personhood

The essence of our argument is that personhood is never independent. Personhood for every individual and natural entity is reliant upon and supported by their environment, relationships, and power dynamics. We are arguing that liberal political theorists in the Euro-western world were wrong to conceive of the legal person as an isolated, atomistic individual. However, we are also arguing that they were correct to conceive of legal personhood as an individual right that has the power to overcome hierarchies of domination and social marginalisation. As such, our conception of legal personhood is one of relational personhood that attaches to the individual or entity and connects them to the world around them. In other words, we believe that it is critical that humans (and, increasingly, natural entities) have a right to be recognised as individual legal persons. We also believe that the law should recognise that the exercise and expression of that legal personhood is often, if not always, a relational process whose success is heavily dependent upon the individual or entity’s environment, relationships, and socio-economic position.

In this paper, we have developed the concept of relational personhood as a way of broadening and deepening our understanding of personhood in general. In addition, we use this concept as a way of explicitly identifying how to give personhood full force and effect, particularly for non-verbal communicators (such as some persons with disabilities, or natural entities such as rivers). Relational autonomy is a mechanism by which individual rights can be operationalised. For clarity, we are not arguing here for the creation of group or community rights (although we also acknowledge that this may be occurring in the field of rights of nature), but about how those individual rights can be operationalised.

We find the work of Watson and colleagues to be instructive in demonstrating the practicality of identifying and creating relationships of sufficient closeness and understanding that they can be a means of giving expression to a communicator who is expressing their will and preference nonverbally. For many people with disabilities, this is essential for the operationalisation of their personhood: rather than privileging the decisions of a guardian acting in the ‘best interests’ of the person, it is now feasible to acknowledge a special relationship as a means of expressing the will of the person directly. This empirical work shows that there is a genuine alternative to substituted decision-making, and shows how the identified indicators could become part of a recognised legal framework.

We also acknowledge that in itself, this recognition of the ‘special relationship’ does not solve the problem of dominance or potential abuse of power. Merely because a relationship is close does not necessarily ensure that the relationship will be one of mutual benefit. However, the concept of relational autonomy requires us to focus not only on the relationship, but to see the relationship as a means towards giving effect to autonomy. The concept of relational personhood explicitly acknowledges that we are all of us in relationships, and that these relationships can be both barriers to, or expressions of, our individual personhood. By bringing these relationships to the fore, we can explicitly identify (and strengthen) the indicators of relational autonomy, and acknowledge and address relationships that undermine autonomy. Every person is vulnerable to relationships of dominance, and rather than relegating such discussions to special circumstances of vulnerability, the concept of relational personhood places this analysis front and centre for all legal persons.

Extending rights to natural entities was historically constructed as an individualised creation of personhood to effectively achieve Christopher Stone’s three elements: legal action at its behest, the consideration by the court of injury to nature itself, and that any relief goes to the benefit of nature.Footnote95 However, although an individualised concept of personhood for nature can formally address these three elements, they can only be effectively achieved via the actions of a representative who can understand and act on the expressed preferences or interests of the natural entity. We argue here that relational closeness is the only way to achieve this outcome, by enabling the representative to communicate with the natural entity, as well as facilitating the communication of the natural entity with the rest of the world, including the court system.

As Martuwarra River of Life et al (this issue) describe, the legal personhood of natural entities requires a new, fit-for-purpose form, which they define as an ‘ancestral being’, leaving open the question of precisely which rights and powers would accompany this status in law.Footnote96 The ancestral being concept is another way of describing ‘relational personhood’, as the purpose of ‘ancestral’ is to formally acknowledge the interconnectedness between humans and natural entities. Some natural entities have received a recognition in law as a ‘living entity’ rather than a legal person,Footnote97 which in the absence of the rights and powers of personhood, depends even more heavily on this relationship, and the willingness of representatives to act.Footnote98

There are no easy answers to the question of how we can know what a natural entity’s will and preference is. But relational personhood shows that there is a way to combine autonomy and power (which natural entities may need in order to be protected within Western legal frameworks) with the close relationships of interdependence and interconnection necessary to give expression to nature’s rights and interests. Considering this from an explicitly pluralist perspective also emphasises the laws and protocols that Indigenous peoples have developed over tens of thousands of years in partnership with the world around them. Relational personhood can thus be a powerful tool for an anti-colonial form of environmental protection.

VI. Conclusion

We came together to write this paper because of the expansion of legal personhood over the past decade to explicitly include people and natural entities whose claims to be legal subjects, with rights and powers of their own, have been historically excluded from models of personhood. In particular, we were inspired by the empirical work of Watson et al in developing a model of relational autonomy that can enable a non-verbal person to give effect to their will and preference. In bringing together perspectives from rights of nature scholarship as well as the rights of persons with disabilities, drawing on theory as well as empirical work, we can develop a new understanding of the concept of ‘personhood’ in general, as well as offering specific insights into the recognition of nature as a legal person.

We have discussed how context of disability has furthered our understanding of legal personhood as an inherently relational concept has the potential to overcome entrenched framings of personhood as atomistic, isolated, and individual, built on an assumption of the white, able-bodied, cis gender, upper-middle class male. We have also explored the relationship between legal personhood and domination, and the ways in which legal personhood can be a powerful response to dominance. We have also identified the inherent weakness in the current assumptions of individualised personhood, particularly (but certainly not only) for people with disability.

We have also drawn on the recent developments in environmental law, in which natural entities have been recognised as legal persons and/or the subjects of legal rights in a growing number of jurisdictions. Although we acknowledge the important reasons not to conflate the interests of natural entities (non-humans) with those of people with disability, we also believe that there are important insights for the personhood of natural entities that can be gained from the scholarship on the rights of people with disability.

Our concept of ‘relational personhood’ uses the work of Watson and colleagues on relational closeness and the role of supporters in assisting people with severe cognitive disability to give effect to their personhood. This important empirical work demonstrates the utility of a conception of legal personhood that encompasses the reality of the interdependence of all individuals and entities. We also acknowledge that the indicators of the special relationship identified by Watson and colleagues are not intended as a legal framework by which the relationship is defined or governed. Their work demonstrates that direct expression of a person’s will and preference is feasible, but how this is reflected in the law is the next important step.

We also acknowledge that Euro-Western ways of knowing and being have largely failed (so far) to learn from Indigenous Peoples’ laws and philosophies. In developing this concept of relational personhood, we hope to build a bridge between Euro-Western legal concepts (such as legal personhood) and Indigenous Peoples’ law and protocol that governs the relationship between people and place. We hope that the concept of ‘relational personhood’, and the relational closeness work articulated by Watson and colleagues, can assist in the quest to ‘tease out what the land’s intentions might be’.Footnote99

We have drawn attention to the relational reality of legal personhood through an examination of disability and disability human rights law.Footnote100 We have articulated this as ‘relational personhood’ and applied the concept in the context of the legal personhood of natural entities. Our aim was to demonstrate how a relational understanding of personhood can allow for the meaningful recognition of personhood – especially for marginalised groups, such as people with disability, women, and others (including natural entities). We believe that this recognition of personhood is critical for overcoming historical and on-going relationships of dominance that are experienced by these groups. Ultimately, we seek to propagate relational personhood – as a more accurate conception of personhood – and to utilise it to secure the right to legal personhood for marginalised groups and to, thereby, increase the power and privilege held by these groups in an effort to achieve greater equality and to come closer to securing equal rights for all.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the two anonymous reviewers for their thoughtfulness and insight, and the journal editorial team for shepherding this paper through the review process. We also acknowledge all speakers and participants at the workshop on legal personhood held at the University of Melbourne Law School in 2019. This paper has emerged from the connections made during that event and the insights generously shared by all participants.

Disclosure statement

Erin O'Donnell is a member of the Birrarung Council, but does not speak for the Birrarung Council in writing this article.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Anna Arstein-Kerslake

Anna Arstein-Kerslake Associate Professor Anna Arstein-Kerslake is an academic at Melbourne Law School and at the Irish Centre for Human Rights at the National University of Ireland Galway. Her research focuses on the human rights of people with disability as well as the right to legal capacity – including legal personhood and legal agency. Her 2017 Book, Restoring Voice to People with Cognitive Disability (Cambridge University Press) was one of the first books ever published on the right to legal capacity. She is also currently on the Editorial Board of The International Journal of Disability and Social Justice (IJDSJ). From 2014-2017, she was the Academic Convenor of the Disability Research Initiative (DRI) at the University of Melbourne and she is now an Establishment Committee Member of the Melbourne Disability Institute. She has successfully completed large research projects in the areas of legal personhood and its impact in criminal law as well as multiple areas of civil law. Notably, she provided support to the United Nations Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities on a general comment on the right to equal recognition before the law. She has also participated widely in consultation with governments and other bodies, including: the United Kingdom Ministry of Justice, the Irish Ministry of Justice, Amnesty Ireland, Interights, and the Mental Disability Advocacy Center, among others.

Erin O’Donnell

Erin O'Donnell is an Early Career Academic Fellow at Melbourne Law School. She is a water law and policy specialist, focusing on water markets, environmental flows, and water governance. She has worked in water resource management since 2002, in both the private and public sectors. Erin is recognized internationally for her research into the groundbreaking new field of legal rights for rivers, and the challenges and opportunities these new rights create for protecting the multiple social, cultural and natural values of rivers. Her work is informed by comparative analysis across Australia, New Zealand, the USA, India, Colombia, and Chile. In 2018, Erin was appointed to the inaugural Birrarung Council, the voice of the Yarra River. For the past three years, Erin has been working in partnership with Traditional Owners across Victoria to identify law and policy pathways to increase Aboriginal access to water rights.

Rosemary Kayess

Rosemary Kayess is a Senior Research Fellow at UNSW Social Policy Research Centre (SPRC) and Senior Lecturer at UNSW Law & Justice, and in 2019, was elected chair of the United Nations (UN) Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Ms Kayess was elected to the UN Committee in 2018 and her rapid appointment to the position of vice-chair in March 2019 recognised her unique expertise from her academic and community positions in Australia and internationally. Ms Kayess graduated from UNSW with a Bachelor of Social Sciences (Hons) in 1994 and a Bachelor of Laws in 2004. She is Academic Lead Engagement of UNSW's Disability Innovation Institute and is one of the driving forces behind the ground-breaking initiative to help transform the lives of people with disability by harnessing research and innovation across all faculties and disciplines. In 2019, Ms Kayess was awarded the Human Rights Medal by the Australian Human Rights Commission.

Joanne Watson

Joanne Watson is a Senior Lecturer in Disability and Inclusion at Deakin University. She is a Speech Pathologist and researcher with over 25 years' experience in the disability sector as a clinician, trainer, support worker, family member and researcher. Jo has worked in Australia, China, Hong Kong and the United States within these roles. Jo's PhD explored supported decision-making mechanisms with people with severe-profound intellectual disabilities and those who care for and about them. Jo has a special interest in working with and supporting people with severe to profound intellectual disability and their supporters, augmentative and alternative communication, assistive technology, supported decision-making, and the application of digital technologies in her teaching and practice. Jo's publications include book chapters and peer and non-peer reviewed academic journals and publications. Jo presents widely in the area of disability and communication disorders within Australia and internationally.

Notes

1 Naffine (Citation2009); Kurki (Citation2019).

2 Ganshof (Citation1996); Radin (Citation1982); Rehbinder (Citation1970).

3 de Haar (Citation2018); Shklar (Citation1998), pp 1–19.

4 Kurki (Citation2019); Mackenzie and Stoljar (Citation2000); McClain (Citation1991); McConnell (Citation1996); Shklar (Citation1998).

5 Christman (Citation2004); Karlan and Ortiz (Citation1992); Mackenzie and Stoljar (Citation2000); McConnell (Citation1996).

6 Arstein-Kerslake (Citation2017a); Arstein-Kerslake and Flynn (Citation2016a); Flynn and Arstein-Kerslake (Citation2014).

7 Arstein-Kerslake (Citation2019); Arstein-Kerslake (Citation2021); Arstein-Kerslake and Flynn (Citation2016b); Christman (Citation2004); Karlan and Ortiz (Citation1992); Mackenzie and Stoljar (Citation2000); McConnell (Citation1996).

8 O’Donnell (Citation2018a), pp 151–153.

9 Stone (Citation1972).

10 See, for example, Carlson (Citation1998).

11 O’Donnell et al (Citation2019).

12 We define ‘natural entity’ to include landscape features (rivers, lakes, mountains, forests), ecosystems, or species. In this paper, we do not explicitly engage with the rights of individual animals or plants.

13 This is in line with the social model of disability. For more information on the social model of disability, see Hughes and Paterson (Citation1997); Shakespeare (Citation2016); Traustadóttir (Citation2009).

14 ‘Without Sign Language, Deaf People Are Not Equal’ (2019), Human Rights Watch, https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/09/23/without-sign-language-deaf-people-are-not-equal.

15 This is in line with feminist theory on relational autonomy. For more information, see Christman (Citation2004); Mackenzie and Stoljar (Citation2000).

16 Davidson (Citation2019); Hughes (Citation2012); Hughes (Citation2019); Millward (Citation2014); Schweik (Citation2009); Snyder and Mitchell (Citation2010).

17 Davis (Citation2014); Shakespeare (Citation1998).

18 Goodley (Citation2014), p 23.

19 Campbell (Citation2009).

20 Evans (Citation2016); Fioranelli et al. (Citation2017); Herzog (Citation2018); Knittel (Citation2014); Shakespeare (Citation1998).

21 Lombardo (Citation2008); Pfeiffer (Citation1994); Shakespeare (Citation1998); Tredgold (Citation2009); Waxman (Citation1994; Woodhouse (Citation1982).

22 Lalit Miglani v State of Uttarakhand & others, WPPIL 140/2015 (High Court of Uttarakhand) 2017, 64. http://lobis.nic.in/ddir/uhc/RS/judgement/31-03-2017/RS30032017WPPIL1402015.pdf.

23 Lalit Miglani v State of Uttarakhand & others, WPPIL 140/2015 (High Court of Uttarakhand) 2017, 62.

24 Arstein-Kerslake (Citation2019); Arstein-Kerslake (Citation2021); Arstein-Kerslake et al. (Citation2017); Dhanda (Citation2006); Flynn and Arstein-Kerslake (Citation2014); Gooding and O’Mahony (Citation2016); Minkowitz (Citation2006); Series (Citation2013); Series (Citation2015); Walmsley (Citation2005).

25 Stone (Citation1972), p 451.

26 Costa (Citation2009); Costa (Citation2019); Thompson (Citation2013).

27 Pettit (Citation1999).

28 Hawley (Citation1999); Sidanius et al. (Citation2001); Sidanius et al. (Citation2017); Tajfel (Citation1974).

29 Lovett (Citation2009); Lovett (Citation2010); Palynchuk (Citationforthcoming).

30 Krause (Citation2013); Schuppert (Citation2015).

31 Arstein-Kerslake and Flynn (Citation2017); Lovett (Citation2009).

32 Arstein-Kerslake and Flynn (Citation2017).

33 Kitchin and Law (Citation2001).

34 Arstein-Kerslake (Citation2017a); Arstein-Kerslake and Flynn (Citation2017); Flynn and Arstein-Kerslake (Citation2014).

35 Arstein-Kerslake et al. (Citation2017); Gooding and O’Mahony (Citation2016).

36 Naffine (Citation2009); Kurki (Citation2019).

37 Plater (Citation1994), p 1003.

38 O’Donnell (Citation2018a), p 17.

39 Godden (Citation1998).

40 Sheehan (Citation2019), p 232.

41 Watts (Citation2013), p 20.

42 Watts (Citation2013), p 23.

43 Levis et al. (Citation2017); Pascoe (Citation2018).

44 Watts (Citation2013), p 23.

45 Stone (Citation1972), p 458.

46 Stone’s provocation led to a dissenting judgment from US Supreme Court Justice Douglas in Sierra Club v Morton 405 U.S. 727 (Citation1972) that recognised a river as a plaintiff.

47 Burdon (Citation2010).

48 Wheeler v Director de la Procuraduria General Del Estado de Loja, Juicio No. 11121-2011-0010, translations from Spanish as per Daly (Citation2012).

49 Macpherson and Clavijo Ospina (Citation2018); O’Donnell (Citation2021); for more on the terminology of legal person/legal entity, see Grear (Citation2013).

50 Ruru (Citation2014).

51 Te Awa Tupua (Whanganui River Claims Settlement) Act 2017 (New Zealand), s 14.

52 Mohd. Salim v State of Uttarakhand & others WPPIL 126/2014 (High Court of Uttarakhand) 2017 (India); this case has been stayed pending appeal to the Indian Supreme Court, see O’Donnell (Citation2018b).

53 Centro de Estudios para la Justicia Social ‘Tierra Digna’ and Others v the President of the Republic and Others [Citation2016] Corte Constituciónal [Constitutional Court], Sala Sexta de Revision [Sixth Chamber] (Colombia) No T-622 of 2016 (10 November 2016), translations as per Macpherson and Clavijo Ospina (Citation2018).

54 Drewes Farm Partnership v City of Toledo Ohio 441 F. Supp. 3d 551 (N.D. Ohio 2020).

55 Human Rights and Peace for Bangladesh v Government of Bangladesh and others [2016] HCD (Writ Petition No. 13989 of 2016, judgement declared on 3 February 2019, 283, translation from Bangla as per Islam and O’Donnell (Citation2020).

56 F. Bibeau, ‘Rights of Manoomin’, Ninth Interactive Dialogue of the General Assembly on Harmony with Nature, UN General Assembly, 22 April 2019, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pP65rIhocqQ.

57 J.A. Schertow, ‘The Yurok Nation Just Established the Rights of the Klamath River’, Cultural Survival, 21 May 2019, https://www.culturalsurvival.org/news/yurok-nation-just-established-rights-klamath-river.

58 CELDF, ‘Press Release: Ho-Chunk Nation General Council Approves Rights of Nature Constitutional Amendment’, 17 September 2018, https://celdf.org/2018/09/press-release-hochunk-nation-general-council-approves-rights-of-nature-constitutional-amendment.

59 Fitz-Henry (Citation2014); Marshall (Citation2020); O’Donnell et al (Citation2020); Tănăsescu (Citation2020).

60 Macpherson and Clavijo Ospina (Citation2018).

61 Tănăsescu (Citation2020).

62 Chapron (Citation2019).

63 O’Donnell and Talbot-Jones (Citation2018); Tănăsescu (Citation2020).

64 Lovett (Citation2009); Lovett (Citation2010); Pettit (Citation1999).

65 Christman (Citation2004); Mackenzie (Citation2014); Mackenzie and Stoljar (Citation2000).

66 Geertz (Citation1984), p 126.

67 Suh (Citation2000).

68 Chan (Citation2004); Iyengar and Lepper (Citation1999).

69 Appell-Warren (Citation2014).

70 Watson et al. (Citation2017).

71 Watson et al. (Citation2017), p 1026.

72 Watson et al. (Citation2017), p 1030.

73 Watson (Citation2016); Watson et al. (Citation2017).

74 Watson et al. (Citation2017), p 1029.

75 Watson et al. (Citation2017), p 1028.

76 Watson et al. (Citation2017), p 1028.

77 Watson and Joseph (Citation2015).

78 Graham (Citation2008), p 186.

79 Watts (Citation2013), p 22.

80 Tănăsescu (Citation2020), p 449.

81 Tănăsescu (Citation2020), p 451.

82 Te Aho (Citation2009), p 285.

83 Te Aho (Citation2009), p 286.

84 Tănăsescu (Citation2020), p 438.

85 Kauffman and Martin (Citation2017), p 137.

86 Tănăsescu (Citation2020), p 447.

87 Tănăsescu (Citation2020), p 447; see also Te Urewera Act 2014 (NZ), s 4.

88 Te Awa Tupua (Whanganui River Claims Settlement) Act 2017 (NZ), s 3.

89 Tănăsescu (Citation2020), p 446.

90 Macpherson and Clavijo Ospina (Citation2018).

91 Tănăsescu (Citation2020), p 449.

92 Watts (Citation2013), p 23.

93 Tănăsescu (Citation2020), p 448.

94 Tănăsescu (Citation2020), p 451.

95 Stone (Citation1972), p 458.

96 Martuwarra River of Life et al. (Citation2021)

97 O’Bryan (Citation2019).

98 O’Donnell (Citation2021).

99 Watts (Citation2013), p 22.

100 For an overview of ‘Disability Human Rights Law,’ see Arstein-Kerslake (Citation2016), Arstein-Kerslake (Citation2017b), Arstein-Kerslake (Citation2018).

References

Primary legal sources

Cases

- Centro de Estudios para la Justicia Social ‘Tierra Digna’ and Others v the President of the Republic and Others [2016] Corte Constituciónal [Constitutional Court], Sala Sexta de Revision [Sixth Chamber] (Colombia) No T-622 of 2016 (10 November 2016), translations from Spanish as per Macpherson and Clavijo Ospina (2018).

- Drewes Farm Partnership v. City of Toledo Ohio 441 F. Supp. 3d 551 (N.D. Ohio 2020).

- Human Rights and Peace for Bangladesh v Government of Bangladesh and others [2016] HCD (Writ Petition No. 13989 of 2016, judgement declared on 3 February 2019, 283 translations from Bangla as per Islam and O’Donnell (2020).

- Lalit Miglani v State of Uttarakhand & others, WPPIL 140/2015 (High Court of Uttarakhand) 2017.

- Mohd. Salim v State of Uttarakhand & others WPPIL 126/2014 (High Court of Uttarakhand) 2017 (India).

- Sierra Club v Morton 405 U.S. 727 (1972).

- Wheeler v Director de la Procuraduria General Del Estado de Loja, Juicio No. 11121-2011-0010, translations from Spanish as per Daly (2012).

Statute

- Te Awa Tupua (Whanganui River Claims Settlement) Act 2017 (New Zealand).

- Te Urewera Act 2014 (New Zealand).

Other

- United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

Secondary sources

- L Appell-Warren (2014) Personhood: An Examination of the History and Use of an Anthropological Concept, Edwin Mellen Press.

- A Arstein-Kerslake (ed) (2016) Disability Human Rights Law, MDPI.

- A Arstein-Kerslake (2017a) Restoring Voice to People with Cognitive Disabilities, Cambridge University Press.

- A Arstein-Kerslake (ed) (2017b) Disability Human Rights Law, MDPI.

- A Arstein-Kerslake (ed) (2018) Disability Human Rights Law, MDPI.

- A Arstein-Kerslake (2019) ‘Gendered Denials: Vulnerability Created by Barriers to Legal Capacity for Women and Disabled women’ 66 International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 101501. doi:10.1016/j.ijlp.2019.101501.

- A Arstein-Kerslake (2021) Legal Capacity & Gender: Realising the Human Right to Legal Personhood and Agency of Women, Disabled Women, and Gender Minorities, Springer Nature.

- A Arstein-Kerslake and E Flynn (2016a) ‘The General Comment on Article 12 of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities: A Roadmap for Equality Before the Law’ 20(4) The International Journal of Human Rights 471–490. doi:10.1080/13642987.2015.1107052.

- A Arstein-Kerslake and E Flynn (2016b) ‘Legislating Consent: Creating an Empowering Definition of Consent to Sex That Is Inclusive of People With Cognitive Disabilities’ 25(2) Social & Legal Studies 225–248. doi:10.1177/0964663915599051.

- A Arstein-Kerslake and E Flynn (2017) ‘The Right to Legal Agency: Domination, Disability and the Protections of Article 12 of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities’ 13(1) International Journal of Law in Context 22–38. doi:10.1017/S1744552316000458.

- A Arstein-Kerslake, P Gooding, L Andrews and B McSherry (2017) ‘Human Rights and Unfitness to Plead: The Demands of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities’ 17(3) Human Rights Law Review 399–419. doi:10.1093/hrlr/ngx025.

- Bruce Pascoe (2018) Dark Emu. Magabala Books.

- Peter Burdon (2010) ‘The Rights of Nature: Reconsidered’ 49 Australian Humanities Review 69–89.

- FK Campbell (2009) Contours of Ableism: The Production of Disability and Abledness. Palgrave Macmillan UK. doi:10.1057/9780230245181.

- AE Carlson (1998) ‘Standing for the Environment’ 45 UCLA Law Review 931-1004.

- H Chan (2004) ‘Informed Consent Hong Kong Style: An Instance of Moderate Familism’ 29 Journal of Medicine and Philosophy 195-206.

- Guillaume Chapron, Yaffa Epstein and José Vicente López-Bao (2019) ‘A Rights Revolution for Nature’ 363 Science 1392-1393.

- J Christman (2004) ‘Relational Autonomy, Liberal Individualism, and the Social Constitution of Selves’ 117(1–2) Philosophical Studies: An International Journal for Philosophy in the Analytic Tradition 143–164.

- MV Costa (2009) ‘Neo-republicanism, Freedom as non-Domination, and Citizen Virtue’ 8(4) Politics, Philosophy & Economics 401–419. doi:10.1177/1470594X09343079.

- M V Costa (2019) ‘Freedom as Non-Domination and Widespread Prejudice’ 50(4) Metaphilosophy 441–458. doi:10.1111/meta.12367

- Erin Daly (2012) ‘The Ecuadorian Exemplar: The First Ever Vindication of Constitutional Rights of Nature’ 21 Review of European Community and International Environmental Law 63-66.

- M Davidson (2019) Invalid Modernism: Disability and the Missing Body of the Aesthetic. Oxford University Press.

- LJ Davis (2014) The End of Normal. University of Michigan Press.

- A Dhanda (2006) ‘Legal Capacity in the Disability Rights Convention: Stranglehold of the Past or Lodestar for the Future Symposium: The United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities’ 2 Syracuse Journal of International Law and Commerce 429–462.

- S E Evans (2016) Hitler’s Forgotten Victims: The Holocaust and the Disabled. The History Press.

- M Fioranelli, M G Roccia, M Rovesti, F Satolli, P Petrelli and T Lotti (2017) ‘The Holocaust of the Disabled’ 167(1) Wiener Medizinische Wochenschrift 54–55. doi:10.1007/s10354-017-0572-4

- Erin Fitz-Henry (2014) ‘Decolonizing personhood’ in Michelle Maloney and Peter Burdon (eds) Wild Law – In Practice, Routledge, 133–148.

- E Flynn and A Arstein-Kerslake (2014) ‘Legislating Personhood: Realising the Right to Support in Exercising Legal Capacity’ 10(1) International Journal of Law in Context 81–104. doi:10.1017/S1744552313000384

- L Godden (1998) ‘Preserving Natural Heritage: Nature as Other.’ 22(3) Melbourne University Law Review 719-742.

- FL Ganshof (1996) Feudalism. University of Toronto Press.

- C Geertz (1984) ‘“From the Natives’ Point of View”: On the Nature of Anthropological Understanding’ in Richard A Shweder and Robert A LeVine (eds) Culture Theory, Cambridge University Press, 123–136.

- P Gooding and C O’Mahony (2016) ‘Laws on Unfitness to Stand Trial and the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities: Comparing Reform in England, Wales, Northern Ireland and Australia’ 44 International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice 122–145. doi:10.1016/j.ijlcj.2015.07.002

- D Goodley (2014) Dis/Ability Studies: Theorising Disablism and Ableism : Theorising Disablism and Ableism. Taylor & Francis Group.

- Mary Graham (2008) ‘Some Thoughts about the Philosophical Underpinnings of Aboriginal Worldviews’ 45 Australian Humanities Review 181–194.

- Anna Grear (2013) ‘Law’s Entities: Complexity, Plasticity and Justice’ 4 Jurisprudence 76-101.

- EV de Haar (2018) Degrees of Freedom: Liberal Political Philosophy and Ideology. Routledge.

- PH Hawley (1999) ‘The Ontogenesis of Social Dominance: A Strategy-Based Evolutionary Perspective’ 19(1) Developmental Review 97–132. doi:10.1006/drev.1998.0470

- D Herzog (2018) Unlearning Eugenics: Sexuality, Reproduction, and Disability in Post-Nazi Europe, University of Wisconsin Press.

- B Hughes (2012) ‘Civilising Modernity and the Ontological Invalidation of Disabled People’ in B Hughes, D Goodley and LJ Davis (eds) Disability and Social Theory, Springer, 17–32.

- B Hughes (2019) A Historical Sociology of Disability: Human Validity and Invalidity from Antiquity to Early Modernity. Routledge.

- B Hughes and K Paterson (1997) ‘The Social Model of Disability and the Disappearing Body: Towards a Sociology of impairment’ 12(3) Disability & Society 325–340. doi:10.1080/09687599727209

- Mohammad Sohidul Islam and Erin O’Donnell (2020) ‘Legal Rights for the Turag: Rivers as Living Entities in Bangladesh’ 23 Asia Pacific Journal of Environmental Law 160–177.

- S Iyengar and M Lepper (1999) ‘Rethinking the Value of Choice: A Cultural Perspective on Intrinsic motivation’ 76(3) Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 349-366.

- PS Karlan and DR Ortiz (1992) ‘In a Diffident Voice: Relational Feminism, Abortion Rights, and the Feminist Legal Agenda’ 87(3) Northwestern University Law Review 858–896.

- Craig M Kauffman and Pamela L Martin (2017) ‘Can Rights of Nature Make Development More Sustainable? Why Some Ecuadorian Lawsuits Succeed and Others Fail’ 92 World Development 130–142.

- R Kitchin and R Law (2001) ‘The Socio-Spatial Construction of (In)accessible Public Toilets’ 38(2) Urban Studies 287–298. doi:10.1080/00420980124395

- SC Knittel (2014) The Historical Uncanny: Disability, Ethnicity, and the Politics of Holocaust Memory. Fordham University Press.