ABSTRACT

Recent voices in creativity research emphasize the vital role that processes of active engagement and interaction play. These distributed, interactivity-based, and ecological accounts critique the reduction of creativity to mental mechanisms and eschew the methodological individualism that underlies this view. Instead, they elevate socio-material couplings to a genuine causal mechanism, hereby explaining why others “are good to be creative with” beyond mutual inspiration or mere constraints on creativity. With improvised dance duets as our example, we introduce a micro-analysis that unpacks these mechanisms from a first-person viewpoint: We describe how the embodied communication at the sub-second scale, a continuous “give and take” between dancers, mediates the co-creation process and how reciprocal micro-actions cumulate into more complex creative effects. Secondly, we distinguish convergent and divergent co-creation dynamics, degrees of playful exploration vs. adaptive pressures, and degrees of individual creative autonomy. Thirdly, we argue that the mix of external constraints, joint exploration, and individual ideation provides a fertile mechanism for co-creation. Finally, we discuss forms of individual creative vision that respect and exploit the dynamic ecology, which can manifest in immediate micro-inspirations, but also in subtle modulations of ongoing process, and in “cultivating” the wider system in ways that benefit novelty.

Introduction

Our present objective is to put under the magnifying glass how the continuous embodied “give-and-take” that many jazz musicians, dancers, or sportsmen report, may lead to spontaneous, yet far from random co-creations. Following Kimmel, Hristova, and Kussmaul (Citation2018), we will study co-creators “in the act.” Using improvised dance duets as our example, we opt for a thorough micro-genetic analysis – a process audit, if you will – at the timescale of several seconds. Looking at interaction with this high degree of temporal resolution is a promising way to uncover details of the co-creative genesis, ask new questions about mechanisms, and evaluate the respective relationship between individual and collective factors. It is also a good way to contrast different forms of creative interaction on a spectrum from convergent to divergent interactions (e.g., complementation, counterpoint, challenge).

Our motivation for writing this paper for a journal with a psychological audience is straightforward: In recent times, interactivity-based, ecological, and distributed creativity accounts have emerged, which argue that engaging with things, spaces, and people provides a mechanism of creativity in its own right. According to this new paradigm, creativity is the emergent outcome of coupling dynamics in a system wider than the mind (Glaveanu, Citation2014a; Malafouris, Citation2019; Sawyer & DeZutter, Citation2009; Steffensen, Vallée-Tourangeau, & Vallée-Tourangeau, Citation2016; Vallee-Tourangeau, Citation2014), a view that is sometimes expressed through the notion of transactionality, which we will discuss. Presently, we hope to hand our readers a methodological and analytic tool to enrich and nuance, and – where needed – to critically evaluate details of this approach.

The following analysis looks at the immediate, yet ephemeral forms of creativity that can be found in improvisational dance contexts. It is rooted in 1st and 2nd person “re-experiencings” supported by video-feedback. By providing a window on creativity “in the act” we will examine, both, the role of collective emergence and how individual creative intentions nourish the former.

The paper begins with an overview of critiques of mind-bound creativity research as well as connections to post-cognitivist cognitive science (Section “Creativity in the act”), before laying out our micro-genetic method (Section “A Micro-genetic approach”), which we apply in two extended case studies (Section “Case studies”); we close by discussing the implications of the micro-analysis for theories of improvisational co-creation (Sections “Lessons about co-creation” and “From theory to method and back”).

Creativity in the act

We begin by surveying the current shift away from traditional individualist views, which have been recently diagnosed as being in a crisis (Glaveanu et al., Citation2019; Malinin, Citation2019), and the emergence of views that emphasize the performative, participatory, and ecological dimensions.

Internalism and its critics

Many accounts in the traditional psychology of creativity, e.g., problem solving theories, variation and selection theories, and dual pathway theories (Boden, Citation1990; Hennessey & Amabile, Citation2010; Kozbelt, Beghetto, & Runco, Citation2010; Runco, Citation2007; Wallas, Citation1926; Ward & Kolomyts, Citation2010; Welling, Citation2007) focus on mental capabilities and thus on the creative resources of individual creators. Operative mechanisms include incubation, problem development, intuition, moments of insight, divergent thinking, mental imagery, associative connections or analogical reasoning, re-framing, and others. This can be summed up as an individualist tradition, which was, at its origins, driven by a dominant interest in creative genius or – in research since the 1950s – in the creative potentials of ordinary individuals.

All these accounts fundamentally assume that ideas arise in the mind (internalism), such that their generation precedes, and is largely separate from, implementation. The creative process is held to preexist the engagement with materials, spaces, and other people. This position is criticized by Malafouris (Citation2014, p. 145) and Ingold (Citation2010) who both take issue with the idea that creative acts impose preconceived form on inert matter (a view which Ingold dubs hylomorphism). Furthermore, traditional research tends to disregard whatever is collaborative or otherwise social about creativity; it also neglects how creativity feeds on the situated constraints and possibilities inherent in the present situation, as well as the role of embodied resources. Malinin (Citation2019, p. 2), for instance, takes traditional research to task for focusing on creative thought as if cognition occurs “in a vacuum devoid of bodily activity, material environment, and socio-cultural context.” We may discuss the involved issues under separate headings:

One frequent shortcoming – at least associated with some older theories – is to focus on creativity statically, by studying the relationship of preconditions and outcomes, while neglecting the process. For example, a process focus can correct popular misconceptions such as the notion of momentary intuition, the classical “heureka” moment. Process-analytic work reveals that creativity requires preparation and hard work over time (Gardner, Citation1993). Even micro-moments of so-called intuition can be analyzed as events encompassing multiple stages (Petitmengin-Peugeot, Citation1999). Below we will show that a processual account of events of several seconds duration in improvised creativity is possible.

A second shortcoming is the disregard of embodied action and perception, a problem that may relate to the dominant interest in inventors, mathematicians, or scientists, and even pervaded how visual artists were analyzed. This neglect was first corrected by accounts of the recursive iterations whereby creative processes move between exploration and generation (Finke, Ward, & Smith, Citation1992; Ward, Smith, & Finke, Citation1998) and by accounts that analyze creativity as a larger system whose evolution over time is characterized by an interplay of so-called “enterprises,” i.e. arrays of activities, with concepts (Gruber, Citation1988). As we will demonstrate below, post-cognitivist approaches radicalize this critique by emphasizing active doing and by looking at resources that arise from the reciprocity of interaction.

A third shortcoming is the neglect of how situated environments constrain and facilitate creativity (Kirsh, Citation2009; Robbins & Aydede, Citation2009). The neglect of “here-and-now” resources may be the flipside of theory biases that overstate what mind-bound potentials can achieve. From the situated viewpoint, skilled action and interaction become a creative asset, e.g., discovery through exploration. This view also implies that specific external limitations contribute to creativity. In this paper, we clarify what kinds of resources may be found in interactive situations and what skills are involved in exploiting them.

A fourth shortcoming is the disregard of social and collaborative aspects. Creative feats, even when they are solitary practices, are embedded in histories and cultural contexts. Glaveanu (Citation2014b) speaks of a recent “we” paradigm of creativity research, which includes social variables as integral factors (e.g., Amabile, Citation1996; Csikszentmihalyi, Citation1998). Sawyer (Citation2006), for example, points out that even individual insights can be traced back to previous collaborations. A perhaps more radical argument is that “[a]lthough society often thinks of creative individuals as working in isolation, intelligence and creativity result in large part from interaction and collaboration with other individuals” (Fischer, Giaccardi, Eden, Sugimoto, & Ye, Citation2005, p. 482). This is the specific meaning of “social” that lies at the heart of this paper.

A final problem underneath these neglects is that traditional views subscribe to a restrictive methodological individualism. They disregard causal effects emerging as individuals engage with their social or material ecology. According to Vallee-Tourangeau (Citation2014, p. 27 f) this suffuses the entire methodology of experimentation:

thinking and problem solving outside the laboratory involve interacting with external resources, and through this interactivity with a material world, solutions are distilled. Still, laboratory work on problem solving pays scant and largely indifferent attention to interactivity […] Ignoring a problem’s physical presentation and the potential for interactivity betray a deep misconception of thinking outside the psychologist’s laboratory. There, thinking is the product of a fluid and dynamic interaction with external resources that produces a shifting configuration of physical features and action affordances.

Despite the brevity of our overview, the critical themes raised clearly suggest that restrictive mentalism will not do for several convergent reasons; we simply cannot afford to overlook situatedness, embodied resources, and processes of collaborative emergence. The overview also indicates that going beyond methodological individualism promises the discovery of heretofore not discussed creativity mechanisms.

Interactivity-based and distributed views

A number of more recent theories – we might term them post-mentalist – emphasize that socially and materially distributed processes are carriers of creativity. For example, creators from various domains report creativity that springs from “conversations” with other people, spaces, or objects and materials. E.g., the dynamic coupling with dance partners can leverage the emergence of novelty (Torrents, Hristovski, Coterón, & Ric, Citation2016); similarly Michelangelo is reputed to have said that he “releases the form from the marble” (Ingold, Citation2014). These views emphasize the constitutive role of dynamic coupling, performativity, and the causal power that lies in recursive engagements. The following claims underlie this:

Creativity transcends mind-bound processes. Acting in the world is irreducibly part of creating. For example, Malafouris – in his theory of material engagement – states that “the making of the creative idea is inseparably […] mental and physical” (Citation2014, p. 145 f) and the creator’s conceptual space is “in moment-to-moment improvisational thinking inside the world (p. 145). We must therefore look to the relational activity. The recursive couplings between the agent and its socio-material ecologyFootnote1 have been described, e.g., as “transactional agent-environment coupling” (Vallee-Tourangeau, Citation2014, p. 40) and, by Ingold (Citation2010), as the weaving of a “fabric”.Footnote2

Thus, creativity mechanisms can be, at least in part, located in the sphere between agent and ecology (including other people), whose field dynamics are deemed to have causal properties that impact creativity. Creativity arises as an emergent property of the recursive give-and-take over time, a “dialogue” if we will.Footnote3

Since creativity may be read as a property of a whole system, encompassing the interacting agents and their environment, this system should therefore be the proper unit of analysis.

Skilled physical engagement with the world is causally efficacious thanks to different types of active strategies that are harnessed to creative ends; these strategies must thus be part of the analysis.

Malinin (Citation2019) argues that “a new definition of creativity is needed to describe creativity as situated practice, emerging through person-environment interactions (material/ technological as well as socio-cultural).” Such convictions are reflected in the notion of distributed creativity (Sawyer & DeZutter, Citation2009) as well as in the work of Glaveanu (Citation2014a, Citation2014b), who discusses temporal, social, and material aspects of distributedness. Glaveanu’s perspective on the wider creative system envisages a constant integration of a system of actors, audiences, artifacts, actions, and affordances. Sawyer (Citation2003) additionally provides the methodological suggestion to study processes of collaborative emergence, i.e. analyze the genesis of a creative event via a give-and-take of response, elaboration, modification or even re-interpretation in interaction. Our own venture of analyzing social interaction as a process of give-and-take will build on and refine these suggestions.

Historical underpinnings of some of these ideas may be found in the notion of transactionality developed by the philosophers Dewey and Bentley (Citation1949) in their influential meta-theory of behavioral inquiry (see Brinkmann, Citation2011; Ryan, Citation1997). They propagate a basic stance that looks at whole events in terms of a durationally extended interplay between elements and that withholds causal attributions to individual elements. Later in this paper we will discuss the term “transactional” in a creativity context, although we will eventually propose a more restrictive definition than Dewey and Bentley’s broad methodological stance would suggest.

Grounding in postcognitivist theory

This new account of creativity is beholden to post-cognitivist cognitive science, where embodied, enactive, extended, and embedded cognition claims (the “4Es”) have been made. In this loose alliance of post-cognitivist views, cognition is held to involve not only the brain, but also bodily structures and processes. Cognitive events extend into the organism’s environment, they involve things an organism does, and they operate in their unique external settings, not in the abstract.

The discussed notion of distributed creativity extends Hutchins’s seminal concept of distributed cognition (Citation1995, Citation2014). Hutchins reconstructs how complex abilities like navigating a navy ship arise from the sum total of individual minds, socio-cognitive coordination, tools, technologies, worksharing arrangements, and communicative arrays. This relates to the emphasis on external features that become “transparent equipment” (Clark, Citation2008) or “transient extended cognitive systems” (Wilson & Clark, Citation2009). In philosophy, this general position is known as externalism (Menary, Citation2010), the claim that inner cognitive states are dependent on their relationship with the external world and that the environment can support mental functions. The extended mind hypothesis even claims that cognition may literally extend beyond the skin (Menary, Citation2013).

Moreover, individual agents use the world “as its own model” (Brooks, Citation1991), e.g., via deictic cues (Ballard, Hayhoe, Pook, & Rao, Citation1997). Perceived features provide an external memory bank and reference points; clever spatial arrangements can help to organize attention (Kirsh, Citation1995).

Cognition is frequently also seen as a form of action (Engel, Maye, Kurthen, & König, Citation2013). This implies that engaging with the environment can produce more rapid, robust, or parsimonious reasoning outcomes. Active exploration and manipulation facilitate problem solving (Kirsh & Maglio, Citation1994). Reasoning can happen as reflection-in-action (Schön, Citation1991) as a real-time process of working toward solutions, which responds to problem states that evolve while acting. The dynamics and continuity of cognition are a requirement, but also a boon since they relieve individuals of the need to make one-shot decisions. They can offload internal thinking to a coupling process over time, in which information gathering, deciding, and acting are braided and recursive (Beer, Citation2003; Gray & Fu, Citation2004; Kirsh & Maglio, Citation1994). All this demonstrates the inadequacy of the serial “perceive-think-act” view of cognition, a view that misrepresents how multiple intersecting loops connect agents and their worlds.

Indeed, recent enactive approaches emphasize that creative systems operate in “continually flowing and dynamic interaction with an environment rather than discrete actions and goal-oriented planning” (Davis, Hsiao, Popova, & Magerko, Citation2015, p. 119). Related, interactivity-based analyses of creative problem solving and reasoning (Kirsh, Citation1995, Citation2009, Citation2014; Steffensen, Citation2013; Steffensen et al., Citation2016; Trasmundi & Steffensen, Citation2016) emphasize the role of recursive engagements (cf. Cowley & Vallée-Tourangeau, Citation2010). Through detailed process analysis these accounts demonstrate that situated embodied actions may not only furnish the context, but the very means of insight, discovery, and reasoning. Interactivity-based mechanisms include (mutual) solution probing, directed exploration, feedback stimulation, and active manipulation or niche shaping.

Some interaction theories implicitly recognize creativity as being part-and-parcel of self-organizing social encounters. Such a position is exemplified by social enactivism, which reclaims the notion of participatory sense-making (De Jaegher & Di Paolo, Citation2007) and where it is “the in-between [that] becomes the source of the operative” (Fuchs & De Jaegher, Citation2009). Even if sophisticated creativity does not lie in the focus of these approaches, the interesting implication arises here that creativity is deeply rooted in everyday interactions.

Ecological dynamics and creative emergence

Finally, a research field known as ecological dynamics is also frequently associated with the wider “4E” paradigm. The basic model used in this field understands behavior as a “continuous functional adaptation […] to a set of interacting […] constraints in order to exploit them to their fullest in achieving specific intended performance goals” (Seifert, Button, & Davids, Citation2013, p. 169). This field of constraints notably includes ecological “actionables” known as affordances (Gibson, Citation1979), interpersonal dynamics, task definitions or desired outcome constraints, as well as internal preferences and dispositions of agents. Authors writing in an ecological dynamics perspective emphasize that, given a set of constraints, the agent-environment system self-organizes in a specific range of ways. Accordingly, novel constraints can stimulate behavior of novel kinds (Araújo, Hristovski, Seifert, Carvalho, & Davids, Citation2017; Chow, Davids, Hristovski, Araújo, & Passos, Citation2011; Seifert & Davids, Citation2017). Behavior is largely seen as adaptation to constraints here.

The presence of constraints can as such benefit creativity. Narrowing down the appropriate constraints can help to manifest new degrees of creative freedom (Torrents, Balagué, Ric, & Hristovski, Citation2021). More generally, creative systems can be catalyzed by using task constraints as control parameters to stimulate variability of behavior (Chow et al., Citation2011; Davids, Araújo, Hristovski, Passos, & Chow, Citation2012); to “create new contexts in which novel opportunities for action emerge” (Hristovski, Davids, Araùjo, & Passos, Citation2011, p. 196); to prompt transitions to new behaviors; to structure the search for novelty; and to facilitate the re-organization of the generative system or the transfer of solutions to novel contexts (Orth, van der Kamp, Memmert, & Savelsbergh, Citation2017, p. 5). It has been shown that, in interpersonal contexts, the ongoing mutual constraining dynamics between two agents has the power of triggering creative adaptations (Araújo, Davids, & Hristovski, Citation2006; Kimmel, Citation2019; Kimmel et al., Citation2018; Łucznik & Loesche, Citation2017; Torrents et al., Citation2016; van der Schyff, Schiavio, Walton, Velardo, & Chemero, Citation2018; Walton et al., Citation2017). Mutual constraint demonstrably benefits creative breadth in jazz (Walton, Richardson, Langland-Hassan, & Chemero, Citation2015). In dance, well-chosen task constraints imposed on improvised interaction have a similar effect (Torrents et al., Citation2016).

Ecological dynamic accounts “partner up” with modeling tools from dynamic systems theory. The latter pitch the analysis relationally from the very start, by describing the coupling dynamics between agents (i.e., brains, bodies) and ecologies (i.e., material environment, other people) in a single model. This is possible because “[differential equations for] single dynamical systems can have parameters on each side of the skin” (Silberstein & Chemero, Citation2011, p. 3). Through this lens, the very idea of the “creative” is a property of the overall process. Certain collective-level features have been postulated to creatively self-organize, e.g., in joint dancing (Torrents et al., Citation2016). This concept applies to systems with many components and many levels of component interaction without any central controller. Self-organizing systems are complex and have their specific emergent dynamics. For example, a suitable increase of entropy can be conducive to creative emergence, when agents “operate on the edge of chaos” (van der Schyff et al., Citation2018), meaning that the system is neither too rigid nor too chaotic. A similar argument emphasizes that creative agents can identify particularly productive zones for exploring novelty or work with deliberate system disruptions, as well as utilizing short-lived system states where small actions result in large qualitative changes (Hristovski et al., Citation2011). We will later refer back to the notions of creative self-organization and emergence and show that they provide vital tools even from a qualitative perspective.

Taking stock

These various “broad views” of cognition evidently share in common the externalist conviction that a whole organism (i.e., brain and sensorimotor periphery) acts in the world and hereby makes creative resources available. Interactions with the material ecology as well as relational dynamics between persons move into focus. Any of these broad views, even cautious variants, will give creativity a framing that addresses its sensitivity to ecological constraints and see it as potentially augmented by physical operations “in the world.” And, if “thinking” is indeed augmented in this way, whatever mental ideation might be involved, it must fall short of a full explanation. The mind cannot be the sole operational locus of creativity.

In view of the many different fields contributing to the debate, each with their academic jargons, a rough-and-ready roadmap to the debate could be as follows: (i) Situatedness describes sensitivity to the evolving ecology; it applies even to solo improvisation and is a common denominator of all “broad views” (and, in our view, the appropriate general stance toward cognitive creativity research). (ii) Distributedness refers more narrowly to systemic networks composed of multiple people and/ or things that generate emergent creative functions; (iii) Transactionality tends to appear as a loose equivalent of distributedness in some publications; given this near-redundancy we will later apply the notion to differentiate something more specific: patterns of emergence where the systemic network shows strong autocatalytic elements, which are recursively harnessed to creative aims.

Scholars associated with the “broad view” differ with respect to the degree to which they study individual cognition and even with respect to how much they consider parlance of mental events appropriate. Some opt for a full focus on the in-between (Ihde & Malafouris, Citation2019), while others leave room for considering mental activities in a dynamically evolving ecology and are open to utilizing insights from individualist creativity research (Glaveanu et al., Citation2019). Or, as Glaveanu (Citation2014a, p. 86) puts it “both individuals and systems are important for our study of creativity.” The latter is a view we align ourselves with and will develop later in this paper.

Either way, there is an evident need to change perspective. For example, as we shall later argue, the long-standing inquiry into creative talent may, in certain contexts, be asking the wrong question because it presupposes an individual locus of creativity. Instead, we should raise new questions such as how individual and external factors are integrated and create synergies. Finally, the perspective change requires new research tools, which is what we concern ourselves with next.

A micro-genetic approach

The methodological problem we wish to focus on is how to reconstruct the micro-dynamics of situated creative assemblies with high temporal resolution, as applied to interpersonal settings.

Data collection protocol

To understand how creativity emerges in and through interaction a detailed process analysis with high temporal zoom factor is desirable. Micro-genetic research tools are now well-tested which investigate how an interaction event unfolds down to the sub-second scale: Both observational (e.g., Steffensen, Citation2013; Steffensen et al., Citation2016) and phenomenological tools (e.g., Gesbert, Durny, & Hauw, Citation2017; Kimmel, Citation2021; Kimmel et al., Citation2018) approaches have been recently applied in the cognitive sciences and surrounding fields such as motor and interaction control studies or research of field sports. Within creativity research, Glaveanu’s work on crafts is notable for a micro-genetic approach using head-mounted cameras (Glaveanu, Citation2014b).

Our present micro-genetic analysis belongs to the phenomenological family; it is therefore of a 1st and 2nd person variety. Tapping into “subjective” experiences has the virtue of making non-observables accessible such as imagery, intentions, anticipation, attention, emotion, pain, proprioception, subtle percepts as well as subtle actions that happen inside the body, all of which usually elude observational “objective” methods.

The two authors and a third interviewer, who is a long-time CI expert, met with couples of experienced dancers in a workshop setting and asked them to improvise together. The dancers first interacted naturally, within an agreed theme. Then, short events of several seconds length were jointly selected for a detailed reconstruction. In this reconstructive dialog we used multiple “sweeps” (cf. Crandall, Klein, & Hoffman, Citation2006; Klein, Citation2003) that built in intensity from summary description to a detailed examination, subsequent probes, and hypothetical questioning: First, the dancers were asked to give a general description of the event. Second, a timeline was created. The participants were asked to consider how many phases the event had and to identify its main “pivots.” Third, we zoomed in to “unpack” the micro-structures of each phase (perception, action, imagery, anticipation, etc.). Dancers A and B took turns in giving an account of each such “thin slice,” but could comment on each other’s reports at any time. This led to a detailed reconstruction of the “who does what when,” including the reciprocal causalities between A and B that arise, e.g., as one person imparts force to the other, invites a response, amplifies an action, or messes with actions of the partner. Lastly, we asked about possible action alternatives at particular junctures that had been discarded.

Part of this reconstructive dialog happened between practice sessions while sitting together. At other moments, we had experts repeat techniques or actively experiment with variations while we filmed and interviewed them. Sometimes, we actively encouraged specific variations to see “which small differences make a difference” at the level of the collective dynamic.

Interviewing tools

The applied interviewing tools (cf. Kimmel, Citation2021) are designed to overcome the difficulty that even experts seldom, in their natural language, describe embodied events and experiences comprehensively. A supportive structure and cueing is thus needed.

Specifically, we used video-stimulated self-confrontation (cf. Axelsson & Jansson, Citation2018; Lyle, Citation2003; O’Brien, Citation1993; Sinnott, Kelly, & Bradley, Citation2017), using a tablet computer to review what had happened. This enables an immersive “re-experiencing” while memories of the event are still fresh. The visual anchors assist the informants in reflexivizing the “what happens when” and allow a deep focus on the small-scale causalities that drive interaction.

We combined this approach with techniques of Explication interviewing, a dialogically guided technique from empirical phenomenology (Depraz, Varela, & Vermersch, Citation2003; Froese, Gould, & Seth, Citation2011; Høffding & Martiny, Citation2016; Petitmengin, Citation2006; Vermersch, Citation1994). Explication interviewing was specifically developed to elevate pre-reflective cognition into consciousness, hence to access tacit aspects of experience, intuitions, and embodied skills “hidden in the body” (Dreyfus & Dreyfus, Citation1999). Interviewers act in a maieutic function; they stabilize informants’ awareness on “thin slices” of experience and encourage a bodily aware, yet reflexive evocative state (Depraz et al., Citation2003; Petitmengin, Citation2006; Stern, Citation2004). The interviewer’s presence (joint breathing, voice modulation, etc.) supports this. Interviewers are trained to be sensitive to hesitation, gaze, etc., to gauge how “connected” the respondent is and to re-stabilize attention when needed. These techniques are known to counteract some of the recognized pitfalls of introspection (Bitbol & Petitmengin, Citation2013) such as memory lapse, omission, confabulation, and ad hoc justification (Vermersch, Citation1999). For similar reasons, Explication interviewing uses iterative checks and re-paraphrasing, which provide a kind of built-in quality check. The dialogic (i.e., 2nd person) modality offsets some of the risks and biases introspection has been criticized for. Anchoring in the video, which the informants and the research team review together, supports this further.

In Explication interviews, the interviewers firmly discourage distracting associations, beliefs, generalizations, or explanations; the idea is to stay very close to the actual embodied level. By keeping informants grounded in the physical reality of interaction they can optimally enrich their report. In the present study, we took interest in the locus and quality of sensations, precursor actions and micro-triggers, or information prompting an adaptation. Our probes recursively came at the event from different angles, using content-free questions (e.g., “what information tells you that you are on target?”) that target the “how” or “what,” instead of “why,” as well as a set of creativity-specific questions customized for this study.

Analysis

With the help of the timeline, we aimed to trace how embodied communication drives the process forward and how the reciprocal (physical and informational) exchange causally shapes a particular creative trajectory.

To understand the emerging trajectory as a whole the functionality of the various micro-constituents needs to be described: First, we identified micro-actions such as exploratory behavior, exploiting a sudden possibility, shaping the field, preparing an option, waiting, or – directed at the partner – enablement, active manipulation, imposing constraints, invitation, accompanying, complementation, nudging, redirecting, or provoking. We noted whether an action mainly functions to gather information, explore action options openly, or impose a decisive and constrained effect on the collective dynamic; we also noted whether the action aimed at problem finding, problem solving, or both. Secondly, we identified sources of perceptual orientation our informants draw upon, notably the following: triggers for starting an action; signals for continuing a multi-phasic action; information confirming that one can continue or must adapt; information indicating serendipitous “doables”; information indicating readiness; and information about the constraints of the setting. Thirdly, we identified momentary system states that are perceived as what we would call “springboards” for complexifying a pattern or as “kernels” inviting creative development. Finally, we noted when and how individually reported exploration interests, themes, or pursuits had an impact. Overall, we came to understand how the ecological constraints of context, space, and interaction dynamics, against the backdrop of individual interests or ideas, made particular actions attractive to individuals.

In this way, we worked upwards from phenomena occurring at the timescale of a second or less to emergent effects that span several seconds. As small-scale actions synergize, blend, or create other complex effects, phenomena arise that we might loosely term creative arcs or creative lines. Each interaction thus unfolds its highly specific trajectory of collaborative emergence, to cite Keith Sawyer’s influential notion once more. Our particular style of analysis allows us to effectively unpack this emergent process texture in terms of the micro-evolution of the embodied “give and take” between the individuals, whose shared ecology co-evolves with their actions at every moment.

Our analysis was necessarily synthetic, since verbalizations emerge by and by as dancers go through the video feedback with dialogic facilitation by the interviewers. The interview was recursive, multi-aspectual, sampled from two perspectives, and, given how short the analyzed interaction event was, of considerable extension (e.g., 88 minutes in case study 1 below). Since movements always have more aspects that can be attended to or mentioned simultaneously the analysis needed to integrate portions from different points in the interview. A key to a precise timeline was referencing verbalizations (including pointing) from our informants to the specific action that appears on the video at the same moment.

Note also that as dancers and long-time embodiment scholars we cannot deny that our movement observation skills and embodied empathy played a central role for “connecting the dots” of our sophisticated movement data. We note this in the interest of full disclosure and think it hardly different from, say, domain-specific skills needed to do process research on mathematical or musical creativity.

Case studies

Our present case study examples come from improvisational dance duets. The word improvisation refers to a spontaneous, but also ephemeral form of creativity. It can be defined as a modus operandi for generating context-responsive behaviors in real time. Improvisers operate under time pressure and evolving situational constraints, must make do with limited resources, and may face ambiguous conditions. Instead of peak performance, the challenge lies in “good enough,” but immediate contributions, in maintaining continuity, and, in an interpersonal context, working together effectively without prior agreement.Footnote4 All this makes improvisation the most ecologically situated form of creativity. Improvisers must ongoingly relate to, and work with the evolving ecology. Spontaneity must be firmly grounded in the immediate spatial situation and interpersonal dynamics. Sawyer (Citation2003) speaks of this as staying in touch with the evolving “emergent.” The creative “ego” has to be sacrificed at the expense of relationality and dynamic openness (Berliner, Citation1994). The eternal trap for novice improvisers is to plan a pattern ahead, which the external world may render obsolete a second later, or try to impose interests that spring to mind, but do not fit the collective process. More experienced improvisers strike a workable balance between individual demands (e.g., stability), collective meaning (e.g. mutual fit), and their exploratory interests.

Contact Improvisation

Even though we collected data from several interaction domains,Footnote5 the power of our methodology is ideally illustrated through a dance known as Contact Improvisation (henceforth abbreviated CI). We chose this domain due to its open, power-symmetric, and formally unconstrained explorations which exhibit creative dynamics of considerable breadth.

CI was developed in the 1970s. It is a continuous form of embodied sense-making with a strong commitment to joint exploration and “a spontaneous mutual investigation of the energy and inertia paths created when two people engage actively and dance freely” (Torrents et al., Citation2016, p. 94). CI follows an egalitarian ethos of respect, mutuality, and autonomy. In contrast to leader-follower dances like Tango Argentino or Salsa, there is no “director” of the improvisation. Decision making is symmetric, even if micro-initiatives may alternate. Much of the time, actions braid so closely that no single instigator of a form or process can be made out. CI is usually practiced on jams in duets or, occasionally, larger formations, and most often without music accompaniment (so-called “silent jams”). Note that coordination happens directly through the body, not through any added semiotics. The meaning experienced by the dancers lies in the physical act, so the dance is not meant to “stand for” anything. In an improvisational dance each creative moment exists in its own terms, in contradistinction to making a sculpture or painting.

CI is notable for its free play and exploration in which “novel places” are explored. Within the bounds of safety and respect, much is possible here. The dancers allow themselves to be taken by surprise, welcome states of “not-knowing,” and sometimes push the boundaries of the possible. Partners may assist, but also challenge, tease, or even trick each other. Often they say “yes, and” to what a partner proposes, but moments of “no but” are equally frequent and produce new and interesting dynamics. CI dancers seldom enforce things; they remain open to new affordances and serendipity, as reflected in the following quotations from our informants: “We don’t have goals. Whatever happens is right” or “We love little glitches because they take us off.” Experienced dancers show a high capacity for utilizing emergent dynamics. In a relevant sense, their creativity is developed not only in, but through the interaction, as we shall demonstrate.

CI creativity is exhibited in the dynamics and movement in space, yet considerably goes beyond external form. CI dancers relish the exploration of joint kinesthesia, momentum, and touch in contact situations (in addition to out-of-contact moments). The creative forms that arise include acrobatic joint lifts, backflips, supported handstands, off-balance leaning, rolling across or sliding off the partner. Here, elements from both bodies enter into synergy through weight sharing, kinetic chains, levers, elasticity, skeletal architectures, or myofascial structures that combine stabilizing struts and elastic tension (tensegrity, Silva, Fonseca, & Turvey, Citation2010). To spontaneously co-assemble collective structures of this sort, it takes considerable physical dexterity, reactivity, attentional skills, and the ability to flexibly synthesize fitting micro-actions in real time. Moments of great subtlety and interiority are equally common. Dancers may, for example, work with the subtle “small-dance,” the tiny swaying movements that bodies create when standing upright, or with the rhythms of breathing. In all these ways, CI creativity is a deeply intercorporeal skill, which involves dynamics or functionalities that stretch across the body boundary. Being creative together benefits immensely, both, from the shared sensory space and physical participation in the bodily states of the other person, a theme we will elaborate on later.

We will now guide the reader through two improvisational dance events considered what Boden (Citation1990) calls psychological creativity (P-creativity), which is when an idea is creative with respect to the experience of the person concerned. This means that we make no claims here as to these events being historical “firsts,” nor is there any reliable way of ascertaining this. The first case study looks at a technically demanding, but organically emerging inverted lift, while the second case study follows a highly dynamic and complex interaction sequence, in which one micro-challenge leads to the next.

Case study 1

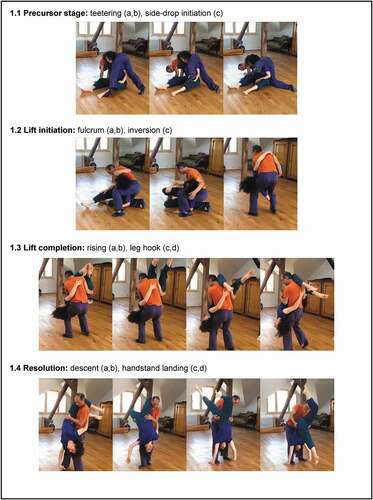

Our first case shows how an inverted lift () emerged within a CI improvisation of several minutes. The creative event in focus has an overall duration of twenty seconds. It can be split into a precursor phase of 8 seconds (Fig. 1.1); the actual lift then builds up over 6 seconds (Fig. 1.2 & 1.3); another 6 seconds are used to land again and to resolve the situation (Fig. 1.4). As acrobatic techniques go, lifts per se are nothing particularly new to CI dancers. They are a nonrandom and meaningful form of collective behavior appreciated for their kinesthetic and acrobatic, possibly also for communicative qualities. At the same time lifts are versatile and provide creative leeway, since their spatiotemporal specifics are open. Despite there being a set of basic technical principles, how they are specifically mixed and calibrated for a lift depends on the unique situation. Our specific instance of a lift was considered distinctly P-creative. Both dancers commented on its surprising ease (i.e. biomechanic functionality), as well as its unique evolution and specific combination of elements. The precise spatial constellation and dynamic had not been considered before by either dancer. Let us now take a closer look at the four phases to analyze the micro-processes of interaction that drive the dynamic forward:

Precursor stage (Fig. 1.1)

Teetering. Our analysis sets in as the male (in the lighter/orange top; M) teeters with his belly and hips on the female dancer’s (in darker/blue top; F) shoulders (1.1a), who is sitting with her legs stretched out in front of her. M then lets himself slip downwards very slightly, while F softly rounds her back in response (1.1b).

Side-drop initiated. M now begins to roll sideways, so that one knee and one foot touch the ground, which land on F’s left hand side and give him support (1.1c).

Lift initiation (Fig. 1.2)

Fulcrum. M begins to assume a more upright orientation while F now also folds sideways from her sitting position (1.2a). These actions occur simultaneously and mutually license each other. F folds until her elbow and lower arm touch the ground and her head rests its full weight in M’s lap (1.2b). As this happens, the couple maintains the hip-neck contact from the prior stage. At the same time, M’s left foot slides below his knee (also 1.2b). Note that since the knee already came to the ground at a 90 degree angle at the previous stages, it takes only a tiny move to bring the foot underneath M’s body center, thus becoming ready for getting up.

Inversion. F begins to use the fulcrum supplied by the neck against M’s lap (with the help of her lower arm) to lift her pelvis from the ground; the fulcrum gives her enough support to make a few tiny steps with her feet (between 1.2b-c) and then to push herself off the ground fully (1.2c). M’s right arm begins to assist F’s pelvis’s upwards trajectory early in this process. M’s hip and leg muscles push him upwards into a standing position (1.2c).

Lift completion (Fig. 1.3)

Rising. Once F’s torso begins to rise upwards, M decides to join his partner’s incipient movement. He gets up himself and sits further backwards (1.3a). The counter-weight that is hereby created translates into extra energy for F’s vertical motion while his upward extending thigh provides a lever that lifts her neck. In other words, his co-actions confirm and amplify her movement tendency. F in turn realizes that she is receiving assistance so she decides to continue her (technically challenging) inverting motion (1.3b). She activates, as she says, “muscle function chains … to have connections ready in the body” enough to pull herself into inverted position, while using her grip on M’s torso to secure and pull herself further up. Sensing this continuing upward movement of hers, M in turn supports her torso with his two hands.

Leg hook. A moment later, their full connection allows M to straighten his back fully (1.3c). F’s neck is now left unsupported and hangs freely; she hooks both legs over M’s right shoulder to provide added support (1.3d).

Resolution (Fig. 1.4)

Descent. The dancers end up with F’s body hanging from M’s while he rotates counterclockwise (1.4a-b). After M has completed a quarter rotation, F tries to efficiently direct part of her weight through M’s body into the ground and uses the friction generated by pushing toward his body to move downwards slowly (1.4a-b).

Handstand landing. F touches the ground again with her hands, while the legs gradually release her weight downwards and while M assists her in grounding her hands fully into a handstand (1.4c). In the end, F’s feet regain ground contact again (1.4d).

Although this inverted lift is a, biomechanically speaking, complex synergy with a certain build-up logic and the requirement of utmost coordination, it did arise spontaneously. An emergent process of distributed creativity (Sawyer & DeZutter, Citation2009) underlies it. Only as dancers ratcheted each other’s actions like cogs on a wheel did the collective form of the lift emerge. The example illustrates how cascades of reciprocal scaffolding activity between two persons – a continuous dynamic of enablement, complementation, assistance, and amplification – lead to a biomechanic synergy of a highly demanding, yet unpremeditated (and in principle unforeseeable) sort.

Micro-causalities

Our Explication interviewing provided detailed insights into reciprocal triggering and facilitation, coordinated synergistic co-actions, as well as exploited precursors and enabling chance elements. Considered from the viewpoint of the complete lift, the central moment at the outset – the creative kernel, if we will – is F’s realization that her neck can become a fulcrum (as her heads sinks, as she says, “saturatedly” into his lap (1.2a-b). The fact that M begins getting up and pulls his body center in the opposite direction adds a lever to this (1.2c-1.3b) and hereby provides a multiplicative factor. The possibility for the full inverted lift thus emerged through an exploitable micro-synergy between already incipient individual actions, which lent themselves to further coordinated augmentation.

Contingency

The dancers testify to multiple possible continuations at key junctures and even specify actions of either dancer that could have changed the trajectory: At the side-drop stage shown in Fig. 1.1 and 1.2., F could have intentionally dropped elsewhere than M’s falling direction (“tons of options … .even upwards with force)” or she could have lacked attentiveness to his move and remained immobile. In this case, the neck fulcrum would have remained absent altogether. In actual reality, F decided to move with M’s direction at the initial moment due to realizing that “M has more options” than herself. A different dynamic might also have resulted at the stage shown in Fig. 1.2 if M had rolled both feet under his body or had fallen forward instead of getting up. In this case, the neck’s position would not have been useful as a fulcrum. Even if the fulcrum had been exploited and M had kept his body somewhat straighter, it remains questionable whether F would have strained to work herself into inverted position devoid of the assisting counter-pull. We can minimally say that M’s co-action in Fig. 1.3 was necessary for a smooth and easy action on F’s part. Overall, our interviews provide confirmation in two respects that the creative dynamics of the lift were emergently coordinated and unplanned: (i) several alternative trajectories are mentioned as conceivable, and (ii) the chosen trajectory depended on specifiable precursors and co-actions of the partner, which emerged from the real-time dynamics and could not have been foreseen as such.

Chance

Even tiny, serendipitous features of the dance can noticeably determine the course taken (cf. Kirsh, Citation2014). F’s stable neck placement being so close to M’s torso (1.2a-b) made it possible for M to lift F, “otherwise things would have continued in a different direction; I’d have looked for an easier way.” And, the fact that M’s hands already “happen to land underneath” F’s pelvis allowed supporting her upwards motion without further preparation (1.2b). Also, M’s knee dropped to the ground (1.2a) at an angle that required only a tiny extra adjustment of the foot (1.2b) to be used to push his torso upwards, which further contributed to making the coordination so smooth. In these many ways, there are chance convergences that enable a specific creative outcome, which the dancers come to exploit opportunistically.

Following the synergy

Not only do the dancers work with what is present, their creative trajectory gravitates toward effective biomechanical synergies. Being functional in this respect is part-and-parcel of being creative for the dancers. For example, F’s inversion into a head-down position became surprisingly easy in virtue of a “highly specific and coordinated use of force” through the synergistic combination of F’s locking into M’s lap and M’s knee levering F’s head upwards (both 1.2a-b) and then sitting back (1.3a-b). Specifically, his “sitting backwards opened a counterbalance and considerably greater forces were freed, which could […] be redirected to facilitate the upwards motion.” If it hadn’t been for this, F’s rising further up would have been difficult or even impossible to execute. Furthermore, the counterbalance had a mutually stabilizing effect, which made up for the dancers’ less than ideal relative position and without which their trajectory would probably have taken a simpler direction. Finally, M reports that momentum from F’s legs, when they pushed off the ground (1.2b-c), contributed to his getting up more fully – he “went into the momentum.” In each of these instances, the dancers picked up on facilitations the partner’s incipient actions and added to them. Their creative path thus, to no small extent, follows a practical logic that banks on resonance with the partner and a clever combination of small elements to generate the necessary energy. The dancers emphasize being insufficiently athletic to perform this lift with brute force and explicitly remark that finding synergistic effects of these kinds is “pleasurable and an esthetic thing to savor.”

Slower dynamics

Finally, the dancers report that more slowly evolving cognitive dynamics contribute to giving a creative path its direction, such as attentional state, preference, or interest: Notably, the condition of possibility for the fulcrum was F’s conscious intention to keep the neck-torso relation (1.1c, 1.2a-b) constant in order to “see what comes of it.” F explains that she was exploring creative potentials of maintaining this relational structure, which exemplifies a frequent creativity heuristic of CI dancers who like to keep certain aspects invariant for a moment in order to explore how the system responds. Somewhat similarly, concerning M’s hand support for F’s pelvis (starting in 1.2b), the dancers speculate that their heightened attention to the arms had carried over from the last moment (F: “a kind of priming facilitated [… .] certain options”; M: “it was easier to call up”). The question how more lasting creative interests constrain emergent coordination patterns will be picked up later again.

Multiple constraints on emergence

Evidently, the co-creative path emerged in a field of multiple constraints, i.e. the dancers’ initial relative placement, the mutual facilitation and micro-affordances they created for each other, their orientation toward functional ease and synergy, as well as particular exploration interests. Take away any of these factors and a different or no inverted lift would have resulted. Furthermore, this was a path-dependent co-creation, which had to run through several necessary precursor states. Even small changes in prior states would have had great consequences.

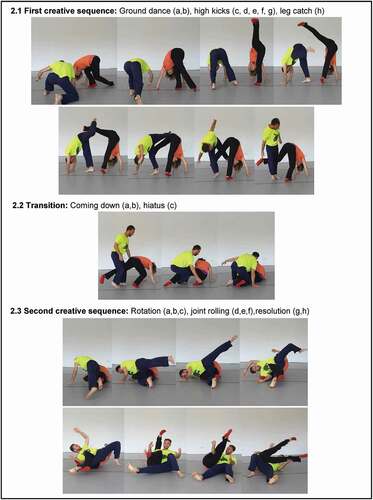

Case study 2

Our second micro-analysis is again taken from an extended improvisation and showcases a continuously evolving cascade of creative interactions with an overall duration of 10 seconds (). It is composed of a two-second high-leg interaction (Fig. 2.1), a three-second transition from upright action to the ground (Fig. 2.2), and five seconds of rolling there (Fig. 2.3). Let us now zoom in on the micro-dynamics again to reconstruct how the creative sequences emerge, grouped into three sub-headings this time.

First creative sequence (Fig. 2.1)

Ground dance. It begins with a dance situation on the ground where the previous interaction had happened. Both dancers now bring their bodies upwards, although their hands keep touching the ground (2.1a). They do not touch each other yet, but coordinate their paths and come almost alongside each other, bottoms facing upwards and legs fully stretched (2.1b).

High kicks. From this position the female dancer (darker/orange top; F) initiates a rapid acrobatic element. She kicks her left leg upward (2.1c) and pivots by a few degrees so the leg traces a semi-circle (2.1d) before coming down (2.1e). The male dancer (lighter/ yellow top; M) has already begun to close in toward her position (2.1c) and, right in the middle of F’s high kick, takes up the inspiration for a similar, although more compact kick that he directs at her lifted leg (2.1d-e). Thus, while entering F’s body space, M mirrors her form (“when I saw her leg go up then I knew that I could also follow with my leg”). Their leg trajectories and relative timings intersect in a way similar to the syncopation one frequently sees in Capoeira practitioners.

Leg catch. As the legs come down again (2.1f-g), a curious interpersonal topology emerges, a leg tangle (2.1h): F’s free left leg gets caught between M’s knees because his leg comes down outside hers; he then deliberately accentuates this by closing both legs to pin her down between his knees. This getting caught prevents F’s from returning her torso to the ground immediately so she keeps her arms and hands in place for support. M, meanwhile, is standing straight. F expressed being flabbergasted: “I felt that [his] leg was catching my leg and noticed that he is upright and I had no clue how he got there”.

Transition (Fig. 2.2)

Coming down. In the resulting situation, F drops her body center (2.2a), folds sideways (2.2b) and comes to lie on her flank and elbow (2.2c). As F initiates this, she scoops M’s knee along with hers; so the knee clamp works in the opposite direction as well once her right knee slides forward (2.2b). The impact from his partner pulls M into a squat (2.2b) and he momentarily struggles with his balance as a result; his right arm is brought down for extra support (2.2b-c). When both dancers arrive on the floor, M’s right knee ends up pinned down under F’s outstretched leg, while her toes are tucked under his ankle (2.2c). Her leg grips around his.

Hiatus. A moment follows at which the legs are tightly entangled (2.3c). The movement stops almost completely for a fraction of a second. The dancers seem to probe for exits in a “now what?” moment, as one dancer puts it. Apparently, a not so easy to resolve situation has emerged, to which a creative response is needed.

Second creative sequence (Fig. 2.3)

Rotation. M, to extricate himself, tries to “open the space again” by rotating outwards, which frees his upper leg (2.3a). M’s torso tilts forward (2.3b) – both heads now point to the wall – and he anchors his weight on his the extended hands meeting the ground next to his head (2.3b-c). His rotation reaches 180 degrees, utilizing the stretched leg’s momentum as it swings to the rear (also 2.3b-c). Next, M straddles F with his pelvis. While rotating around his central axis he simultaneously continues the upwards-and-sideways arc of his leg. (“I kind of drop on to you with my [right] side … and then the leg swings around”). The right arm and shoulder lead the straddling; his front and the lower arm follow along until he faces the ceiling (2.3d).

Joint rolling. Until the moment shown in 2.3c, F stays put apart from drawing her knee closer in the lock and rotating minimally. But from moment 2.3d onwards she begins to act more decisively. She starts to mess with M’s ongoing actions at the moment where M’s free knee reaches the apex of its arc by rolling from her flank to her back. While doing so, her pelvis rotates (2.3d-e). This makes both entangled knees rise, which acts as an upward lever on M’s whole leg. Also, the support that F’s pelvis had provided for M now gets pulled away under him through her sideways rotation. M is unexpectedly displaced so that he slides off F (2.3e). His head and torso suddenly tilt upwards. With a surprised grin M drops to the ground next to F (2.3f).

Resolution. F, meanwhile, is taken along with the momentum. As soon as her back is grounded and M has come down fully, she pulls both legs upwards, drops them outstretched over his torso, rolls her hip onto him and slides over his surface (2.3g), while he turns onto his tummy and uses one hand to guide her legs and shield his face (2.3h).

To sum this up, we have discussed two subsequent creative moments, where the second one is the path-dependent outcome of the first. The first creative motive is complementing and mirroring a leg kick, which results in a problem configuration – the knee clamp; this in turn stimulates a creative solution attempt by one partner that the other partner modulates, thereby creating the next problem. Throughout, both dancers keep enacting a shared general idea manifested as multiple rapid spirals and rotations. Note that the leg kicking interaction of the first creative sequence (Fig. 2.1) is only based on visual coordination. In the absence of any mechanical connection or ”collective physics”, we might speak of an “esthetic synergy” here. In contrast, the dynamic in the second creative sequence that develops out off the knee clamp (Fig. 2.3) exhibits mutually invasive mechanical coupling. Now, the “collective physics” of the entangled bodies begins to drive creativity. The dancers’ interplay of forces, weights, and momentum creates dynamic trade-offs, both through overlapping actions and sequential triggering.

Micro-causalities

Zooming in on the details, the first creative sequence (Fig. 2.1) begins with a kind of – at least biomechanically speaking – parallel creativity (Fischer et al., Citation2005); dancers are moving individually (2.1a-b) and relate to each other visually as M joins into F’s high-kick a split second later (2.1c). The intersecting 3-D trajectories of their high legs (2.1g) directly result in the unique configuration that brings their knees together (2.1h), a position which M exploits by adding the knee clamp with minimal extra effort. M does this to introduce a creativity-stimulating challenge for himself and the partner. As the second creative sequence begins (Fig. 2.3), dancer M is the first to try to resolve this impasse (2.3a-c), but dancer F surprises him at just the moment that he prepares to swing his leg over her (2.3d). Her rolling sideways displaces him and changes his attempt at problem solving into something different, a drop (2.3d-f). We may say that F co-modulates M’s ongoing action in real-time (Kimmel & Rogler, Citation2019), so that it results in something different, a sudden further challenge that supervenes on the first one and keeps their entanglement going. Dancer F commented on the changes in dominant initiative between the dancers as follows: “You were provoking and that’s when I was like, yeah, I have to do something not to get the knee … ah … twisted. But actually I think I’m going into a wrong direction to survive it. And then you gave in. Later. As you turned with me” [our italics]. M also confirms for that later moment “I’m kind of following.” Looking at the a small snippet of the video footage in slow motion even suggests a miniature scale give-and take in which, firstly, M’s free leg rises and his body front begins to open, which gives F’s pelvis a minimal impetus (2.3c), which she then picks up on (2.3d) and creates a full rotation from, which in turn becomes a major lever that redirects M’s movement (2.3e-f).

Iterativity & creative perturbation

What this analysis shows well is the crucial role that recursive micro-cycles of bidirectional coupling play for creative surprises to arise. Dancers use the causal consequences of their own actions, the re-afferent feedback from the partner, and the new state of entanglement this creates to develop their creativity. M’s knee clamp at a single remove already results in F pulling him into the squat and faces him with a tricky leg tangle (2.2c). This creative kernel would not have occurred without the prior deliberate perturbation, and the whole dance would have taken a completely different direction. As in case study 1, this analysis demonstrates how tiny local negotiations (in our case: of weight, balance, force, and space) can give rise to new creative interests at the next moment. Different from case study 1, in which a potentially risky acrobatic form and therefore complementary and supportive micro-moves were in focus, this second case study indicates that micro-moves that mess with ongoing collective dynamics in clever ways and that create joint challenges provide another major source of creative innovation.

Continuity & discontinuity

The question emerges in what way dancers relate to the ongoing collective dynamics. Case study 2, again, offers indications that chance and emergence are actively embraced. Several creative aspects simply emerged by exploiting a serendipitous possibility. F’s high kick in 2.1c-d exploits her body position and M’s knee clamp in 2.2a-b was done “without really having to do too much effort” or going against the dynamics. But going with the dynamic alone is often only half the story; the dancers skillfully merge micro-ideas into what they “get for free.” Of special note in this context, M’s creative intention was to introduce discontinuity within the prior continuity of their dance. He reports that the interruption is “still somehow related to the pattern like I didn’t, completely, introduce something that was outside of that world. Like, we were still in the mechanics of this spiraling together and then we ended up in this place where I could interrupt it in a way without really having to do too much effort to interrupt it.” M specifically notes that his perturbation was introduced with “a softness and listening […] a sensitivity inside the interruption,” also to prevent injury. The example illustrates that perturbations require skill to happen in a, both, thematically and biomechanically continuous way.

Slower dynamics

Across different moments of the improvisation, both dancers acknowledge the mentioned spiraling theme where they alternately move around each other’s centers, or as M also puts it “a larger rhythmic theme.” This has the status of a joint frame (Fogel, Citation1993) that had previously been established between them in the first creative sequence (Fig. 2.1) and that, as a shared creative interest, continues into the second sequence (Fig. 2.3), where it constrains the selection of actions. M states: “we’re in this moment of kind of spiraling together, in this kind of harmonious moment. And I think it was just out of that kind of tracing our bodies following those circular pathways. So it was another way of kind of staying in time and in space together.” The spiraling theme is interrupted at one moment by M’s sudden knee clamp which “broke not just the rhythm, but this biomechanics of what had been happening […] And maybe that’s why it was such a surprise” [to F]. Later, as F states, the spiraling continues on the ground despite a strikingly “new spatial arrangement between us” that results when M’s extricates himself from the lock in a circular arc.

Embodied esthetics

Dancer M comments on the mirroring leg action in 2.1d-e as a case of embodied esthetics “that looks cool, but also feels cool.” This perception relates to the required skill and self-challenge: “it’s always better to arc with somebody [… .] there’s this excitement that it’s like, wow, if that was one second earlier or later we would crash. [… .] And you’re able to do it but still maintain your own structure. […] There is a lot more complexity than doing it by yourself. Because you’re not only tracking the movement, or: your own movement, but you have to track it in relationship to another person. […] I have to sense, yeah, where this other person is in space and how my body is relating to that person. So, I would say that it’s spatially much more complex, […] maybe there is a puzzling. Like a puzzling how do these bodies fit together in space.” Other comments by M suggest that fleeting body memories from the past (“I’ve done just a little bit of Capoeira or … you know, so those movement patterns might be in my body somewhere”) and a specific interest in playful togetherness convergently shaped his decision to follow F’s high-kick: “there is […] a play in a staying with someone – because also you’re doing the same movement as someone. It’s like kind of showing that you’re together with them. So I think it was a way of harmonizing and bringing a connection between us to also follow with the leg.”

Summing up

Overall, our empirical analysis illustrated three basic points: First, creative forms can straddle the skin boundary; they emerge from couplings of multiple components from two bodies. Secondly, the creative process co-evolves with a field of constraints and affordances, which the participants continuously shape through their activity. Thirdly, embodied interaction itself furnishes many mechanisms of creative genesis. Whatever role ideas and intentions played, creativity much depended on the continuous embodied give-and-take between the dancers, which expressed the creativity, but recursively generated it as well.

We reconstructed the event in terms of microscopic physical or informational interchanges between the individuals, the give-and-take from which a co-creative path emerged. Specifically, by tracking the embodied (i.e. non-semantic) communication through which the dance partners provide small affordances and constraints for each other and how simultaneous actions amplify or other modulate each other we came to understand how, in one case, a demanding inverted lift synergy emerged and, in the other case, how one interesting micro-challenge triggered the next in a cascade, which led to a unique spatio-temporal dynamic. The creative process was thus mediated by mutual interpersonal scaffolding, a mechanism which can take different forms, as we have seen and will explain in greater detail below. In the process, the interacting individuals recursively stimulate each other’s micro-creativity, e.g., through on-the-spot challenges and problem solving, but may also temporarily establish joint exploration interests and themes.

Ultimately, the analysis clarified why a certain class of creative process is neither causally attributable to a sole author nor to a single moment. Instead, the give-and-take between individuals can become a creative resource quite beyond or, if we will, “atop of,” individual micro-ideation. A collective system can catalyze co-creation and drive individuals to unexplored possibilities. Both of our case studies thus exemplify processes that can be legitimately referred to as transactional forms of creativity, which we aim to define more precisely later.

Lessons about co-creation

We would now like to further reflect on the role of transactional dynamics in the wider context of improvisation research and specify some of their dimensions.

Why interaction is creatively productive

What is the role of interaction dynamics for creativity? It is evident that togetherness vastly expands the range of things one can do (e.g., no one can lift themselves up), but our point is a further reaching one: Interaction, understood as reciprocal dynamic, can also become a genuine mechanism of creativity. This means that creative genesis happens not only in interaction, but literally through it.

CI experts, in several of our micro-phenomenological interviews, noted why interacting takes them way beyond their solo creativity: “When I am in contact I never need [my own] creativity, because the other person takes care of this. The other person provides so much nourishment for my creativity that I would never get stuck. You work with whatever you have or wait for impulses to come.” Another dancer says: “It somehow happened, but both of us ask ourselves – wow, how did that come about – in these moments evidently something new happens that does not result from planning. It is only possible through the specific interaction now.”

Similarly, informants from other studies report practices of converging on certain zones that propel them into really novel dynamics impossible to produce alone, sometimes associated with precarious states of “brinkmanship” (Kimmel & Rogler, Citation2018, Citation2019) and states of “not knowing” (Kimmel et al., Citation2018). Interaction can produce options they would not consider alone or that propel them “off the beaten path.” An improvising jazz musician (pers. comm.) remarked that “others help you subvert your habits.” Interaction can afford moments of sudden theme convergence between jazz players (Monson, Citation2006) or parallel actions that blend into unexpected new doables. Note how this process-dynamic argument differs from social creativity arguments that emphasize pooling of resources such as in mutual brainstorming or inspiration.

Nonetheless, the proverb “the more, the merrier” does not apply: Whereas experts can draw from togetherness in unique ways (Torrents et al., Citation2016), based on a high-quality interaction, for novices co-creating together can be much more challenging than acting alone (Issartel, Gueugnon, & Marin, Citation2017). For them, the potentials of transactional creativity may be offset by highly demanding coordination pressures of some musical or movement system, which need to be mastered first since multiple tasks at both the individual and the collective level need to be carried out interdependently. So, togetherness has pros and cons. As Keith Sawyer notes, a tricky balance is always at stake between interpersonal coherence and inventiveness (Citation2003, p. 88).

Convergence and divergence

Both case studies have in common that creative outcomes emerge if, and only if both agents engage in relational micro-activities at each moment. However, we have also seen that the process can involve quite different micro-textures.

One type of relational dynamic is convergent. It involves cascades of mutual enablement and dynamic complementation of what another person does, as exemplified by case study 1. On the basis of reciprocal invitations and responses two or more persons converge on a collaborative form of creative synergy. In convergent dynamics, co-creators pick up on and extend the collective dynamic, often with some shared underlying interest e.g. in an acrobatic challenge. The partners develop themes together, enable, add to, amplify, or complement the partner’s actions. In CI, this is often termed “saying ‘yes, and’” to an offer, a mode of smooth collaboration. They may use prior states as a “homebase” for (Eilam & Golani, Citation1989) or “springboard” into (Sudnow, Citation1978) an extension. In particular, two individuals can progressively complexify a biomechanic structure toward something more intriguing. The outcome remains open, of course, but both act within the constraints of some joint functionality, such as the lift we have seen, so the situation has a chance of being complexified.

Another type of relational dynamic appeared in the second part of case study 2, a mode that is more divergent. It occurs when one or both persons mess with the ongoing dynamics, exert energy against what is already happening or effect some discontinuity. Mild forms of divergence are commonly termed “saying 'no, but'” in CI circles, where one still acts somewhat collaboratively. It means that a proposal by the partner is not taken up, but a counterproposal is made that maintains continuity and is fairly easy to embrace.

However, more incisive forms of divergence are also possible, such as active challenge or even perturbation of an ongoing partner action, e.g., by redirecting a force vector elsewhere. In case study 2, this took the form of playful antagonism, in which agents still look after each other and maintain a joint orientation. The more extreme cases, such as we might see in martial arts, are characterized by forceful manipulation, disruption, deception, and coercion. This often implies “hijacking” the other person’s attempts, a real-time converting into a structure opposed to the other person’s interest (Kimmel & Rogler, Citation2018). Thus, radical divergence can include “hostile take-over” attempts of the interaction system as a whole – which can, of course, induce creative counteractions (Kimmel & Rogler, Citation2019).

On the one hand, divergence may arise in virtue of a deliberate perturbation undertaken in order to stimulate creativity, as in our case study 2. Unforeseen regions of the possibility space are frequently accessed through risk taking and challenging yourself or others. For example jazz band leader Miles Davis is reputed to have done this very skillfully with other band members. (This exemplifies active problem finding, cf. Runco, Citation1994). On the other hand, divergence of sorts can also arise less intentionally. “Happy accidents” and errors are known to drive creativity. In such cases creative repairs are developed on the spot (e.g., when a musician disguises the error of another as discussed by Berliner, Citation1994) or what happened is co-opted into a new function (called retroactive reframing by Sawyer, Citation2003).

The convergence vs. divergence distinction also sits nicely with a spectrum of co-creative dynamics that we may glean from the improvisation literature (Torrance & Schumann, Citation2019). For example, the musicologist Berliner (Citation1994) contrasts creative interactions in jazz bands along the lines of complementary forms such as synchronic mixing, reinforcing, repetition or mirroring, motivic development, as well as divergent forms such as counter-point structures that create cross-accentuation schemes or interlocking patterns, or gap filling (i.e. occupying open spaces).

An overlapping distinction concerns how pro-actively improvisers relate to what is already going on. Some improvisational moments involve just “surfing the flow.” Improvisers exploit serendipity and chance discovery; they opportunistically pick up on readily accessible affordances. The opposite of this is to shape the collective situation with effort by going against the momentary dynamics. In these instances, improvisers typically give their interest in a theme or technique a greater prominence than what the ecology readily affords.Footnote6

The terms convergent and divergent are familiar from traditional creativity research. It will therefore be helpful to explicate the relationship of our views to these more disembodied views. In a context such as a dance duet, the creative process can be said to be externalized and enactivized: It happens as much through action in the world as through internal ideation. In other words, functions of convergence- and divergence-producing engagement with the world move into focus, as well as the role of relating to the ongoing task dynamics and its constraints. The term convergent thinking is normally applied to the solving defined problems in the mental realm (Guilford, Citation1967). In an embodied context, this would map on actions that occur within a current task definition, be it a joint frame or theme improvisers pursue together or be it an ongoing technique that requires resolution, such as lift that needs to result in a safe landing. Convergent actions thus operate within relatively defined degrees of freedom. In contrast, divergent thinking, as it is normally conceptualized, operates in more unconstrained ways and transcends given task definitions. Analogously, divergent interaction in a field such as partner dance implies that the degrees of freedom are opened up or new dynamics introduced into the collective field, such that the task itself becomes a subject to negotiation and that shared frames, if any, are called into question.

Serendipity, adaptation, exploration, and ideation