?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

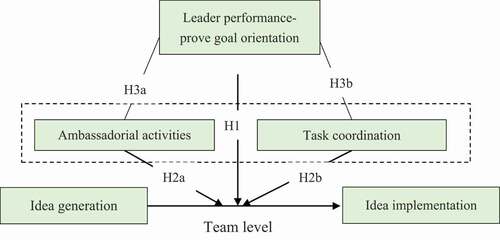

Creative idea generation does not necessarily lead to the implementation of these ideas. Although the conditional relationship between creative idea generation and implementation has frequently been recognized, there have been few studies of the moderating factors that facilitate converting creative ideas into tangible innovations. To fill this research gap, we explore whether leader performance-prove goal orientation facilitates the implementation of creative ideas at the team level. Furthermore, we investigate the mediating role of leader comprehensive boundary-spanning strategy in the moderating effect of leader performance-prove goal orientation. From an analysis of data from 83 new product development (NPD) teams, we find the following: (1) Leader performance-prove goal orientation positively moderates the relationship between idea generation and implementation. (2) Leader ambassadorial activities and task coordination both positively moderate the relationship between idea generation and implementation. (3) The moderating role of leader performance-prove goal orientation is mediated by leader ambassadorial activities. Our findings have theoretical and practical implications for innovation management in NPD teams.

Although many novel ideas emerge within organizations, only a few are recognized and converted into tangible innovative outcomes (Baer, Citation2012; Perry-Smith & Mannucci, Citation2017). However, “ideas are useless until used” (Perry-Smith & Mannucci, Citation2017). As innovation is an essential way for organizations to gain competitive advantages, sustainability, and growth, and organizations have increasingly turned to team-based structures to develop innovative projects, more research is needed on the boundary conditions under which team-level creative ideas can be successfully converted into innovative products (Perry-Smith & Mannucci, Citation2017; van Knippenberg, Citation2017). Only a few studies to date have focused on team-level research, and they have obtained conflicting empirical results on the relationship between creative idea generation and implementation. Some scholars have argued that the generation of creative ideas promotes team innovation (Axtell et al., Citation2000; Somech & Drach-Zahavy, Citation2011). However, others have found non-significant or even negative relationships (Baer, Citation2012; De Dreu & West, Citation2001). These results suggest a contingent relationship between idea generation (the development of novel and useful ideas) and idea implementation (the conversion of ideas into innovative products, services, procedures, and processes) (Anderson, Potočnik, & Zhou, Citation2014; Lee & Farh, Citation2019; Mumford, Scott, Gaddis, & Strange, Citation2002; West, Citation2002).

Notwithstanding, the contingencies of the relationship between idea generation and implementation are underexplored in team innovation research (van Knippenberg, Citation2017). Those few scholars who have explored this area have found that participation in decision-making, team innovation climate, individual network ability, and implementation instrumentality can turn divergent new thinking into innovative outcomes (De Dreu, Citation2001; Perry-Smith & Mannucci, Citation2017; Somech & Khalaili, Citation2014). Although these studies have obtained meaningful results, they have largely ignored the goal-directed nature of innovation implementation and the role of goal priorities in achievement context when implementing teams’ creative ideas. Furthermore, although scholars have pointed out that implementing creative ideas “lie outside of the teams” (van Knippenberg, Citation2017), these studies have mainly examined the moderating factors between idea generation and implementation from an internal perspective; the moderating effects of external factors have been largely ignored.

The implementation of creative ideas faces many challenges. First, studies have found that decision makers are biased against extremely creative ideas or cannot recognize creative ideas at all (Mueller, Wakslak, & Krishnan, Citation2014; Zhou, Wang, Song, & Wu, Citation2017). Second, organizational resources are limited and thus not all creative ideas can be implemented (Baer, Citation2012; Berg, Citation2016). In settings that emphasize and reward creativity and innovation (e.g., new product development [NPD] teams), advocating the implementation of teams’ creative ideas is primarily a motivational, goal-directed process, and thus requires teams to be motivated to eliminate decision makers’ creative bias and compete for resources by demonstrating competence and championing their creative ideas, which is central to performance-prove goal orientation (Alexander & van Knippenberg, Citation2014). More importantly, creative ideas “require skillful leadership in order to maximize the benefits of new and improved ways of working” (Anderson et al., Citation2014, p. 1298). Leaders are the representatives of teams, and their performance-prove goal orientation, defined as a dispositional tendency to demonstrate competence and gain favorable evaluations, may be the most important factor in facilitating the implementation of teams’ creative ideas (Chadwick & Raver, Citation2015; Dragoni, Citation2005).

Additionally, individuals choose specific behaviors and strategies during goal pursuit/striving process to realize their achievement priorities (Alexander & van Knippenberg, Citation2014; Gong, Kim, Lee, & Zhu, Citation2013). Motivated by a performance-prove goal that focuses on obtaining positive external evaluations, leaders will initiate more externally oriented behaviors and work across team boundaries to seek organizational resources to realize their team’s creative ideas. Therefore, in light of boundary-spanning theory (Ancona & Caldwell, Citation1992), we contend that leader performance-prove goal orientation influences the relationship between idea generation and implementation through leader boundary-spanning behaviors, which refer to actions through which the leader reaches out into his/her environment to obtain resources and support (Faraj & Yan, Citation2009; Marrone, Citation2010).

Based on goal orientation theory (Vandewalle, Citation1997), which holds that goal orientation determines the subsequent motivational processes of goal generation and goal striving (Chen & Kanfer, Citation2006) and incorporates external perspectives (Ancona, Citation1990), we propose a theoretical model for when and how novel ideas generated by teams can be successfully implemented. We contribute to the literature in the following three ways. First, we respond to the call for more empirical insights into the relationship between idea generation and implementation by exploring it at the team level (van Knippenberg, Citation2017). Second, we explore the critical boundary condition of leader performance-prove goal orientation between idea generation and implementation. This effort complements the literature by introducing the moderating role of leader motivational disposition in an achievement context. Furthermore, because teams cannot work in isolation in modern organizations (Ancona & Caldwell, Citation1992), we incorporate an external perspective to investigate the moderating effects of specific leader boundary-spanning strategies (ambassadorial and task coordination activities) on the relationship between idea generation and implementation. We thus provide a unique perspective on the complex boundary conditions between the generation of creative ideas and their implementation. Third, we enrich the literature by exploring the mediating role of leader boundary-spanning activities in the moderating effect of leader performance-prove goal orientation. This facilitates an in-depth understanding of the complex moderating mechanism of leader performance-prove goal orientation, and elucidates the relationship between externally oriented goal orientation and boundary-spanning activities. The theoretical model is summarized in .

Theory and hypotheses

We propose that idea generation and implementation are conditionally related; that is, the successful implementation of innovative products relies on contingent factors. In this study, we argue that one kind of achievement motivational disposition – performance-prove goal orientation – offers team leaders the critical motivation to obtain scarce organizational resources such as attention, money, talent, time, or political cover to realize their team’s creative ideas (Alexander & van Knippenberg, Citation2014; Perry-Smith & Mannucci, Citation2017). The inherent motivation to be recognized and outperform others inspires team leaders to champion and “issue-sell” their creative ideas, which in turn helps to quell top management’s fears of failure. Moreover, a team’s “better than average” performance reputation earned through high performance-prove goal orientation could send an effective signal when top management is allocating innovative resources among teams/projects. Therefore, leaders with high performance-prove goal orientation facilitate the successful conversion of creative ideas into innovative products. Furthermore, we propose that this externally oriented motivational disposition induces subsequent externally oriented goal striving behaviors, and thus leader performance-prove goal orientation also indirectly influences the relationship between idea generation and implementation through boundary-spanning activities.

Ancona (Citation1990) differentiated boundary-spanning strategies into three categories. The “ambassadorial” strategy concentrates on ambassadorial activities; the “technical scouting” strategy combines scouting and task coordination activities; and the “comprehensive” strategy combines ambassadorial and task coordination activities. A comprehensive strategy involves both vertical and horizontal communication, which aims to influence resource allocation and obtain support. Ambassadorial activities involve talking up and “selling” good ideas, buffering external interventions, and acquiring resources (e.g., money, new members, and equipment, Ancona & Caldwell, Citation1992), while task coordination activities are concerned with negotiating schedules, dealing with dependency issues, and coordinating with other teams focused on research and development (R&D), design, and manufacturing (Ancona & Caldwell, Citation1992). We contend that this comprehensive strategy is most effective when teams attempt to implement their creative ideas (Alexander & van Knippenberg, Citation2014).

Therefore, in light of goal orientation theory and the external perspective, we constructed a theoretical model to investigate the critical boundary conditions that facilitate converting team creative ideas into innovative outputs through the lens of leader performance-prove goal orientation and boundary-spanning strategies. Furthermore, the mediating effects of leader boundary-spanning behaviors on the moderating effect of leader performance-prove goal orientation in the relationship between idea generation and implementation will be theorized and examined.

The relationship between idea generation and implementation

Team idea generation is defined in this paper as the process of generating novel and useful ideas through the concerted effort of team members, and idea implementation is the process of converting collective creative ideas into tangible outcomes that can be subsequently diffused and adopted within and outside organizations (Perry-Smith & Mannucci, Citation2017). Although some scholars have found that the generation of creative ideas is positively related to idea implementation (Somech & Khalaili, Citation2014), other studies have suggested a non-significant or even negative relationship (Baer, Citation2012; De Dreu & West, Citation2001; Lee & Farh, Citation2019; Lu, Bartol, Venkataramani, Zheng, & Liu, Citation2019; Perry-Smith & Mannucci, Citation2017). One reason for these conflicting results is the implicit bias against novel ideas, which involve high uncertainty and require substantial investment of organizational resources to implement. This may inhibit acceptance and the “green light” from top management and other critical decision makers, who require further proof of idea implementation (Baer, Citation2012; Lee & Farh, Citation2019). The other reason for the non-significant relationship might be that top management cannot fully recognize the novelty and value of these creative ideas. In other words, teams’ creative ideas may not attract enough attention from top management (Lu et al., Citation2019).

The moderating role of leader performance-prove goal orientation

As new ideas involve high uncertainty and risk of failure and may consume a large amount of organizational resources, top management and other critical decision makers utilize various criteria to decide whether to support the implementation of a team’s new idea (Baer, Citation2012). One of the most widely used criteria is the decision maker’s impressions of a team’s previous performance/competence. As the team’s role model and representative, a leader’s impression and efficacy may be treated as characteristic of their team. The literature has demonstrated that team leaders with performance-prove goal orientation pursue and obtain “better than average” performance evaluations, which ensure that they often win inter-team competitions (Dietz, Van Knippenberg, Hirst, & Restubog, Citation2015; Dragoni, Citation2005). More importantly, their “better than average” performance evaluations are more likely to be noticed by decision makers, because performance-prove goal oriented leaders tend to show off their competencies and high performance in achievement settings (Dragoni & Kuenzi, Citation2012). Therefore, previous excellent performance and positive reputation are important signals for critical decision makers (e.g., top management) that a team can cope with the uncertainty and risks involved in initiating creative ideas under the management of performance-prove goal oriented leaders.

Furthermore, many novel ideas are abandoned because they do not demonstrate potential and fail to attract the attention of critical decision makers (Mueller, Melwani, Loewenstein, & Deal, Citation2018; Mueller et al., Citation2014). Performance-prove goal oriented leaders are more likely to perceive the team behaviors that lead to high performance evaluations, that is, the production of innovative products rather than merely the generation of ideas. The desire to outperform others motivates high performance-prove goal oriented leaders to sell their teams’ creative ideas by underscoring their value and encouraging positive assessment of these ideas by top management (Lu et al., Citation2019). This increases the likelihood that they will be recognized and approved by top management and receive adequate resources. Although previous studies have found mix results regarding the effect of performance-prove goal orientation on creativity (Dietz et al., Citation2015; Gong et al., Citation2013), we propose that teams led by high performance-prove goal oriented leaders are more likely to successfully implement their creative ideas.

Hypothesis 1 (H1): Leader performance-prove goal orientation positively moderates the relationship between idea generation and implementation at the team level.

The moderating role of leaders’ comprehensive boundary-spanning strategy

External communications are critical for the implementation of creative new product ideas, because they directly invite financial support, political cover, task-related help, and other valuable resources (Alexander & van Knippenberg, Citation2014; Ancona & Caldwell, Citation1992). Therefore, we propose that the comprehensive boundary-spanning strategy of team leaders positively moderates the relationship between idea generation and implementation.

First, we suggest that a leader’s ambassadorial activities increase the likelihood that creative ideas will be implemented by granting them influence and legitimacy (Perry-Smith & Mannucci, Citation2017). Ambassadorial activities are defined as those by which the team leaders “protect the team from outside pressure, persuade others to support the team and lobby for resources,” and represent the vertical communication of team leaders (Ancona & Caldwell, Citation1992, p. 640). According to Perry-Smith and Mannucci (Citation2017), for a team’s creative ideas to be realized, they must be championed, legitimated, and validated by outsiders, especially top management and stakeholders. Team leaders who frequently engage in external ambassadorial activities can develop intense external contacts with top management and other critical decision makers that allow them to obtain advance information about the present task and/or project. Additionally, through ambassadorial activities, teams can improve their ideas to exceed the expectations of external actors. This increases the chances that they will be approved and supported by external actors, especially decision makers in control of the allocation of valuable resources such as money, talent, time, and political cover (Ancona & Caldwell, Citation1992; Perry-Smith & Mannucci, Citation2017). Furthermore, teams need a sparse spanning network structure to champion and legitimize their creative ideas (Perry-Smith & Mannucci, Citation2017). Leaders who conduct ambassadorial activities build this type of social network with top management and other critical decision makers, and thus can borrow the structural holes of top management to increase the influence and legitimacy of their creative ideas, helping to ensure that they are accepted and implemented.

Second, we propose that horizontal external communication from team leaders (task coordination activities) also positively moderates the relationship between idea generation and implementation. Team leaders who often negotiate and coordinate tasks with other work teams/units can obtain concrete task-related help and support and professional advice when implementing novel ideas. For example, after discussing design issues with experts and representatives from product design teams/units, NPD team leaders may be more confident about the feasibility of their novel ideas for products and more motivated to “sell” their team’s ideas to critical decision makers. Moreover, based on professional advice and feedback from R&D, design and manufacturing groups/units, the feasibility of creative ideas can be improved and obstacles to implementation can be removed, accelerating the successful implementation of these ideas (Ancona & Caldwell, Citation1992).

Hypothesis 2a (H2a): Leader ambassadorial activities positively moderate the relationship between idea generation and implementation.

Hypothesis 2b (H2b): Leader task coordination activities positively moderate the relationship between idea generation and implementation.

The mediating role of leaders’ comprehensive boundary-spanning strategy

We further propose that the moderating effect of leader performance-prove goal orientation is mediated by comprehensive boundary-spanning strategies, that is, the ambassadorial activities and task coordination activities of team leaders. In essence, performance-prove goal orientation is an externally oriented motivation and can therefore lead to externally oriented goal striving behaviors (Chen & Kanfer, Citation2006; Gong et al., Citation2013). Leaders motivated by performance-prove goals desire to be recognized and applauded by external evaluators. Therefore, team leaders with high performance-prove goal orientation will engage in more external communication activities with top management (vertical external communication) and other work teams/units (horizontal external communication) than leaders with low performance-prove or other goal orientations, because these boundary-spanning behaviors convey critical evaluation information and feedback regarding focal teams’ performance and impression management. Alexander and van Knippenberg (Citation2014) theoretically proposed that performance-prove goal orientation can enhance a team’s boundary-spanning behaviors during innovation implementation. However, this proposition has not been empirically verified.

As leaders’ ambassadorial and task coordination activities are theorized to moderate the relationship between idea generation and implementation, we contend that the moderating effect of leader performance-prove goal orientation is mediated by leader ambassadorial activities and task coordination activities.

Hypothesis 3a (H3a): Leader ambassadorial activities mediate the moderating effect of leader performance-prove goal orientation on the relationship between idea generation and implementation at the team level.

Hypothesis 3b (H3b): Leader task coordination activities mediate the moderating effect of leader performance-prove goal orientation on the relationship between idea generation and implementation at the team level.

Method

Sample and data collection

We collected data from new product development (NPD) teams in 10 high-tech companies in Shaanxi and Henan provinces in China. The products developed by these NPD teams are hardware-related such as electronic sensor and semi-conductor chip. This survey lasted eight months, from October 2018 to July 2019. One of the authors introduced this survey to the top management of the companies, who along with the human resource management departments provided their help. We assured the respondents of the confidentiality of the survey to increase the participation and response rate. To decrease the possibility of common method bias (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, Citation2003), we collected data from multiple sources (i.e., team leaders and team members). Team leaders/supervisors evaluated their team’s level of creative idea generation, their own performance-prove goal orientation and comprehensive boundary-spanning behaviors, and provided basic data such as team size and team tenure, and their own demographics such as gender, age, and tenure. It should be noted that each team leader/supervisor in our study was only in charge of one NPD team. Team members evaluated their team’s level of idea implementation. At least three key informants from each team evaluated the level of idea implementation, which should be sufficient to provide accurate information on the team’s function and output (Bresman, Citation2010). We distributed questionnaires to 102 NPD team leaders and 389 team members. After deleting questionnaires that were incomplete or had obvious mistakes, we obtained a sample set consisting of 83 teams (team leaders) and 305 team members. The response rate is 83% at the team level, and 78.4% at the individual level. We used a t-test to compare the demographics (such as tenure and age) between respondents and non-respondents and do not find any significant difference between these two groups (p > .1). Therefore, non-respondent bias is not an issue in our research.

Measurements

Idea generation

Rather than counting the number and frequency of creative ideas, we adopted a scale of team creativity to measure the degree to which teams generate novel and useful ideas (Baer, Citation2012). We adopted the four-item scale of team creativity developed by Shin and Zhou (Citation2007). Sample items were “How well does your team produce new ideas?” and “How useful are those ideas?” We used a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (poorly) to 7 (very much). Following the suggestion of Shin and Zhou (Citation2007), team leaders were asked to rate the level of idea generation of their team. Cronbach α = 0.91.

Idea implementation

We used the scale developed by Baer (Citation2012) to measure idea implementation at the team level with the referent-shift method, replacing “employee” with “your team.” At least three key informants in the teams who had a good understanding of the situation were asked to evaluate the level of team idea implementation. This scale had three items: “Please rate the frequency with which, in the past, your team’s creative ideas (1) have been approved for further development; (2) have been transformed into usable products; (3) have been successfully brought to market or successfully implemented at your organization.” Team members were asked to indicate their level of agreement with five statements using a 7-point Likert-type scale (1 = never, 7 = always). Three statistical indexes had to be calculated before the aggregation of individual-level data on idea implementation up to the team level: (1) The test of within-team inter-rater agreement rwg (James, Demaree, & Wolf, Citation1993) yielded a minimum value of 0.89 for idea implementation. (2) ICC (1), which describes the extent to which individual-level variability on a given measure is explained by higher-level units (Bliese, Citation2000), was 0.25 for idea implementation. (3) ICC (2), which provides the estimate of the reliability of group means (Bliese, Citation2000), was 0.71 for idea implementation. These indices justified the aggregation of individual-level data to the team level (Bliese, Citation2000). Cronbach α = 0.88.

Leader performance-prove goal orientation

We adopted the scale developed by Vandewalle (Citation1997) to assess team leaders’ performance-prove goal orientation, that is, to measure their desire to prove their competence and obtain favorable judgments about it. This four items were: “I am concerned with showing I can perform better than others,” “I try to figure out what it takes to prove my ability to others at work,” “I prefer to work on projects where I can prove my ability to others,” and “I enjoy it when others at work are aware of how well I am doing.” This scale has frequently been used in past research and validated in both Western and Eastern cultural contexts (Dragoni & Kuenzi, Citation2012; Gong et al., Citation2013). Leaders were asked to indicate their level of agreement with seven statements using a 7-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). Cronbach α = 0.90.

Leader comprehensive boundary-spanning strategy

Following Ancona and Caldwell (Citation1992), we used the self-evaluation method to ask team leaders to evaluate their level of boundary-spanning behaviors. Typical items concerning ambassadorial activities were: “To what extent did you persuade outsiders to support team decisions?” and “To what extent did you keep other groups in the company informed of your team’s activities?” Typical items concerning task coordination were: “To what extent did you coordinate activities with external groups?” and “To what extent did you resolve design problems with external groups?” Leaders were asked to indicate their level of agreement with seven statements using a 7-point Likert-type scale (1 = poorly, 7 = very much). Cronbach α = 0.91 and 0.89 for ambassadorial and task coordination activities, respectively.

Control variables

To obtain the unique effect of leader performance-prove goal orientation and boundary-spanning behaviors, we controlled for leader sex, leader tenure, team tenure, and team size. Team size and tenure have been found to influence the level of idea generation/team creativity and team innovation (Gong et al., Citation2013; Vandewalle & Cummings, Citation1997). Furthermore, previous studies have shown that sex and tenure may have distinct effects on individual performance goal orientation (Button & Mathieu, Citation1996). Tenure is also related to the social network of leaders, which may influence their boundary-spanning behaviors within organizations (Ancona & Caldwell, Citation1992). These control variables were obtained from the basic demographic data in the questionnaires.

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA)

We conducted CFA to verify the convergent and divergent validity of our constructs. Our research focused on the team level, and the critical variables in our theoretical model such as leader performance-prove goal orientation and ambassadorial and task coordination activities were evaluated by team leaders, and were thus inherently team-level constructs. Therefore, it was appropriate to use team-level CFA to test the fit between our theoretical model and the data (Chen, Mathieu, & Bliese, Citation2004). To increase the robustness of team-level CFA, we used the item parceling approach to create three parcels for each latent variable by averaging the aggregated items with the highest and lowest loadings (Landis, Beal, & Tesluk, Citation2000). The CFA results show a good fit between the data and our five-factor measurement model: c2/df = 1.53, GFI = 0.94, CFI = 0.95, RSMEA = 0.03, SRMR = 0.04. These indexes are better than those of a four-factor model (combining idea generation and implementation, c2/df = 3.84, GFI = 0.91, CFI = 0.92, RSMEA = 0.09, SRMR = 0.08), a second four-factor model (combining ambassadorial and task coordination activities, c2/df = 4.79, CFI = 0.89, RSMEA = 0.08, SRMR = 0.07), and a one-factor model (c2/df = 7.53, GFI = 0.74, CFI = 0.80, RSMEA = 0.11, SRMR = 0.09). Therefore, the convergent and divergent validity of the measures were supported.

Results

reported the means, standard deviations, and correlations of all of the variables. For example, the correlation between idea generation and implementation was not significant; leader performance-prove goal orientation was positively related to leader ambassadorial activities.

Table 1. Means, SD, and correlations

We tested H1, H2a, and H2b using the hierarchical linear regression method recommended by Aiken and West (Citation1991). First, we entered the control variables in the regression model; second, we entered the independent variable and moderators to explore the main effect; third, we put the interaction terms of idea generation and leader performance-prove goal orientation, idea generation and ambassadorial activities, and idea generation and task coordination in the regression model to examine the moderating effects of leader performance-prove goal orientation, ambassadorial activities, and task coordination. To reduce the possibility of multicollinearity, we centralized all of the predictors in the regression models (Aiken & West, Citation1991).

From , we can see that the interaction of idea generation and leader performance prove goal orientation was positively related to idea implementation, = 0.37, p = .004. Therefore, H1 was supported. To delineate the accentuating effects exerted by leader performance-prove goal orientation in the relationship between idea generation and implementation, we plotted a simple slope figure (Aiken & West, Citation1991). In , we can see that when the leader is high in performance-prove goal orientation (M + SD), idea generation was significantly related to idea implementation, b = 0.57 (

= 0.45), p = .002; however, when the leader was low in performance-prove goal orientation (M – SD), this relationship was not significant, b = −0.06 (

= −0.05), p = .137.

H2a proposed that leader ambassadorial activities positively moderates the relationship between idea generation and implementation. From , we can see that the estimated coefficient of the effect of idea implementation on the interaction between leader ambassadorial activities and idea generation was = 0.42, p = .005; therefore, H2a was supported. We also plotted a simple slope figure to delineate the moderating effect of leader ambassadorial activities. In , we can see that when leaders initiated a high level of ambassadorial activities (M + SD), idea generation was positively related to idea generation, b = 0.61 (

= 0.51), p = .002; however, when ambassadorial activities were low (M – SD), this relationship was not significant, b =- 0.03 (

= −0.02), p = .160. H2b, which proposed that leader task coordination positively moderates the relationship between idea generation and implementation, was marginally supported by our result,

= 0.16, p = .061. We plotted a simple slope figure to demonstrate the moderating role of leader task coordination. In , we can see that when leader task coordination level was high (M + SD), b = 0.27 (

= 0.21), p = .014; when leader task coordination level was low (M – SD), b = 0.05 (

= 0.04), p = .122.

Table 2. Results of hierarchical linear regression

Figure 2. Simple slope of the moderating role of leader performance-prove goal orientation in the relationship between idea generation and idea implementation

Figure 3. Simple slope of the moderating role of leader ambassadorial activities in the relationship between idea generation and idea implementation

Figure 4. Simple slope of the moderating role of leader task coordination in the relationship between idea generation and idea implementation

Following the interaction taxonomies proposed by Gardner, Harris, Li, Kirkman, and Mathieu (Citation2017), the directions of the independent variable and moderators were the same in the regression results regarding the moderating effects of leader goal orientation and leader ambassadorial and task coordination activities. Therefore, these interaction effects can be categorized as “strengthening” and more specifically, “accentuating.”

H3a and H3b proposed that leader ambassadorial activities and task coordination mediate the moderating effect of leader performance-prove goal orientation on the relationship between idea generation and implementation. We examined the mediated moderation models of H3a and H3b using the method recommended by Edwards and Lambert (Citation2007) and adopted by Grant and Berry (Citation2011). To obtain the mediated moderation effects of leader ambassadorial activities and task coordination activities on the moderating effect of leader performance, we needed to calculate the products of (1) the path from leader performance-prove goal orientation to leader ambassadorial activities and task coordination and (2) the interactions of leader boundary-spanning activities (ambassadorial activities and task coordination) and idea generation on idea implementation. We constructed the bias-corrected confidence intervals to examine H3a and H3b and used a bootstrap size of 5,000. If the 95% bias-corrected confidence interval excluded 0, the indirect effects of leader ambassadorial activities and task coordination on the moderating effect of leader performance-prove goal orientation in the relationship between idea generation and implementation can be confirmed. As the 95% bias-corrected interval excluded 0 [0.017, 0.209], H3a was supported. However, although the interaction of leader task coordination and idea generation on idea implementation was positive and significant (H2b), H3b was not supported, because the 95% bias-corrected interval included 0 [−0.012, 0.013].

Discussion

Overview of the findings

Using data from 83 NPD teams, we obtain several critical results. Our empirical results support H1, H2a, H2b, and H3a. However, H3b is not supported. That is, we find the interactions of idea generation and leader performance-prove goal orientation, idea generation and leader ambassadorial activities, and idea generation and task coordination significantly influence idea implementation. Furthermore, leader performance-prove goal orientation has a moderating effect on the relationship between idea generation and implementation through the mediating role of leader ambassadorial activities rather than task coordination activities.

First, as we theorized and in line with previous research, creative idea generation does not necessarily lead to the implementation of these ideas (Baer, Citation2012; Perry-Smith & Mannucci, Citation2017). This may be partly because the idea implementation scale we used was clearly distinguished from idea generation, rather than an innovation scale including both idea generation and implementation; thus, our findings support the differentiation of different innovation phases (Somech & Drach-Zahavy, Citation2011; West, Citation2002). Second, our results demonstrate that the moderating effect of leader performance-prove goal orientation on the relationship between idea generation and implementation cannot be mediated by leaders’ task coordination activities. This result indicates that although performance-prove goal orientation may induce externally oriented behaviors, for team leaders any externally oriented behaviors motivated by performance-prove goal orientation may be dominated by vertical communication, rather than horizontal communication with other work teams. Therefore, the relationship between goal orientations and subsequent goal pursuit/striving behaviors may differ depending on the subject, e.g., the team leader vs. team members (Ancona & Caldwell, Citation1992).

As we theorized, we find that leader performance-prove goal orientation and leader ambassadorial and task coordination activities positively moderate the relationship between idea generation and implementation. Performance-prove goal orientation provides the critical motivation for leaders to demonstrate their competence and dismiss the bias of top management against creative ideas. Ambassadorial and task coordination activities help to secure the resources needed to convert creative ideas into tangible innovative outcomes. This positive effect of leaders’ networking behaviors is also consistent with the effect of individuals’ networking in ensuring that their creative ideas are implemented (Baer, Citation2012).

Theoretical implications

Our study contributes to the literature in three ways. First, the dispositional tendency of leaders to enact and promote creative ideas, demonstrate competence, and outperform other NPD teams is vital when teams intend to implement their creative ideas. However, as far as we know, no previous study has empirically examined the role of leader performance-prove goal orientation in the transition from creative ideas to tangible innovative outcomes. Our study enriches the literature on the factors that facilitate the implementation of creative ideas at the team level through the lens of goal orientation theory. Furthermore, our findings offer evidence that it is theoretically and empirically meaningful to differentiate the idea generation phase from the implementation phase (Baer, Citation2012; Perry-Smith & Mannucci, Citation2017; West, Citation2002).

Second, this study is one of the first to use an external perspective to examine the moderating role of leader boundary-spanning strategy in the relationship between idea generation and implementation. Although modern team’s work is interdependent with other organizational units (Ancona & Caldwell, Citation1992), the literature has pervasively adopted an internal perspective when exploring factors facilitating the transition from idea generation to idea implementation. Additionally, in organizational context boundary spanners are often group leaders (Hogg, van Knippenberg, & Rast, Citation2012), and Ancona and Caldwell (Citation1992) proposed boundary-spanning theory primarily based on team leaders’ externally oriented strategies; nonetheless, there is a lack of research on the effects of leaders’ boundary-spanning behaviors. Therefore, we enrich the literature on the boundary conditions of the relationship between idea generation and idea implementation by taking an external perspective and identifying the critical moderating roles of leader ambassadorial and task coordination activities.

Third, scholars have argued that performance-prove goal orientation is related to externally oriented motivation, because someone who prefers this goal focuses on external evaluation (Gong et al., Citation2013). However, to the best of our knowledge, few studies have explored the effect of performance-prove goal orientation on boundary-spanning behaviors. We fill this theoretical gap by exploring whether the comprehensive boundary-spanning strategy of team leaders mediates the moderating role of leader performance-prove goal orientation. This investigation demonstrates the relationship between leader performance-prove goal orientation and specific leader boundary-spanning behaviors such as ambassadorial activities, and thus improves our understanding of the antecedents of boundary-spanning activities and the outcome of performance-prove goal orientation. Furthermore, our findings deepen our understanding of the complex underlying mechanisms of the moderating role of leader performance-prove goal orientation in the relationship between creative idea generation and implementation, and provide information for future research on the relationships between different goal orientations and boundary-spanning behaviors.

Managerial implications

Our empirical results provide several managerial implications regarding creativity and innovation management for NPD teams. First, the team’s generation of creative ideas does not in itself lead to their implementation. Therefore, team leaders should take steps to enhance the conversion of creative ideas into innovations. Our results demonstrate that when team leaders are characterized by high performance-prove goal orientation, the opportunities for successfully implementing these creative ideas increase. Therefore, we suggest that leaders be performance-prove motivated when creative ideas have been generated and search for organizational resources to implement them. Although individuals are generally driven by one dominant goal orientation, state goal orientation theory suggests that individuals may be “temporarily induced to prefer a specific achievement goal” (Dragoni, Citation2005, p. 1084). That is, when creative ideas have been generated, leadership can recognize this as a key moment to shift from other types of goal orientation (e.g., learning goal orientation) to performance-prove goal orientation. Leaders who lack this kind of ambidexterity can be trained through formal organizational training programs. Moreover, when NPD teams produce abundant creative ideas yet often fail to successfully implement them, management should assign leaders/supervisors with a high level of performance-prove goal orientation to increase the likelihood of creative idea implementation.

Second, team leaders can also initiate more comprehensive boundary-spanning activities to facilitate the implementation of teams’ creative ideas. As leaders are the representatives of their teams, ambassadorial activities constitute their main behaviors in high performance teams (Ancona & Caldwell, Citation1992), including persuading top management to support their projects, presenting the novelty and value of their creative ideas, and acquiring valuable resources for the implementation of their teams’ creative ideas. A high frequency of ambassadorial activities indicates team leaders’ high networking ability, which can substantially enhance the implementation of creative ideas. Our findings also demonstrate that vertical coordination and negotiation activities with other work teams/units should be encouraged when converting creative ideas into tangible outcomes.

Limitations and future directions

Although our research was carefully designed, some limitations remain and need to be resolved by future research. First, we used cross-sectional data to test our theoretical model, which only provide correlations rather than causal relationships between the variables. In the future, longitudinal data should be collected to further explore causality between variables, especially the relationship between idea generation and implementation. Second, according to the innovation phase model based on the social network perspective (Perry-Smith & Mannucci, Citation2017), individual innovation consists of four phases: idea generation, idea enactment, idea champion, and idea implementation. Although individual-level innovation processes may differ from team-level innovation, this network-based innovation model provides critical insights for future directions in team innovation research. For example, in addition to exploring the boundary conditions between idea generation and implementation, we could explore the moderators between idea generation and idea enactment, as each phase has unique requirements.

Third, we used at least three key informants within each team to measure idea implementation; however, our results will be more robust if we collect data from all team members. Furthermore, the measurement invariance regarding core variables should be verified in the future by collecting data from countries with different cultural backgrounds (Vandenberg & Lance, Citation2000).

Conclusion

Based on the literature on creativity and innovation (Baer, Citation2012; Perry-Smith & Mannucci, Citation2017; van Knippenberg, Citation2017; West, Citation2002) and goal orientation theory (Dragoni, Citation2005; Gong et al., Citation2013; Vandewalle, Citation1997), we proposed a theoretical model of the boundary conditions between idea generation and implementation at the team level and the mediating mechanisms that explain this moderating effect. Our results demonstrated that leader performance-prove goal orientation facilitates the realization of creative ideas as tangible outcomes. Furthermore, the moderating role of leader performance-prove goal orientation is mediated by leaders’ ambassadorial activities. Therefore, for teams to increase the chances of their ideas being implemented, team leaders should adopt performance-prove goal orientation. If they are characterized by other types of goal orientation, they should be trained to switch between different goal orientations to meet the demands of different innovation stages.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: SAGE.

- Alexander, L., & van Knippenberg, D. (2014). Teams in pursuit of radical innovation: A goal orientation perspective. Academy of Management Review, 39(4), 423–438. doi:https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2012.0044

- Ancona, D. G. (1990). Outward bound: Strategies for team survival in an organization. The Academy of Management Journal, 33(2), 334–365.

- Ancona, D. G., & Caldwell, D. F. (1992). Bridging the boundary: External activity and performance in organizational teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 37(4), 634–665.https://doi.org/10.2307/2393475

- Anderson, N., Potočnik, K., & Zhou, J. (2014). Innovation and creativity in organizations: A state-of-the-science review, prospective commentary, and guiding framework. Academy of Management, 40(5), 1297–1333.

- Axtell, C. M., Holman, D. J., Unsworth, K. L., Wall, T. D., Waterson, P. E., & Harrington, E. (2000). Shop floor innovation: Facilitating the suggestion and implementation of ideas. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 73(3), 265–285. doi:https://doi.org/10.1348/096317900167029

- Baer, M. (2012). Putting creativity to work: The implementation of creative ideas in organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 55(5), 1102–1119. doi:https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2009.0470

- Berg, J. M. (2016). Balancing on the creative high wire: Forecasting the success of novel ideas in organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly, 61(3), 1–36. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0001839216642211

- Bliese, P. D. (2000). Within-group agreement, non-independence, and reliability: Implications for data aggregation and analysis. In K. J. Klein & S. W. Kozlowski (Eds.), Multilevel theory, research, and methods in organizations (pp. 349–381). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Bresman, H. (2010). External learning activities and team performance: A multimethod field study. Organization Science, 21(1), 81–96. doi:https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1080.0413

- Button, S. B., & Mathieu, J. E. (1996). Goal orientation in organizational research: A conceptual and empirical foundation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 67(1), 26–48. doi:https://doi.org/10.1006/obhd.1996.0063

- Chadwick, I. C., & Raver, J. L. (2015). Motivating organizations to learn: Goal orientation and its influence on organizational learning. Journal of Management, 41(3), 957–986. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206312443558

- Chen, G., & Kanfer, R. (2006). Toward a systems theory of motivated behavior in work teams. Research in Organizational Behavior, 27, 223–267. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-3085(06)27006-0

- Chen, G., Mathieu, J. E., & Bliese, P. D. (2004). A framework for conducting multi-level construct validation. Research in Multi-Level Issues, 3, 273–303.

- De Dreu, C., &;West, M. A. . (2001). Minority dissent and team innovation: theimportance of participation in decision making. Journal of AppliedPsychology, 86(6), 1191–1202. doi:0021-9010.86.6.1191/0021-9010.86.6.1191

- De Dreu, C. K. W., & West, M. A. (2001). Minority dissent and team innovation: The importance of participation in decision making. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(6), 1191–1201. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.6.1191

- Dietz, B., Van Knippenberg, D., Hirst, G., & Restubog, S. L. D. (2015). Outperforming whom? A multilevel study of performance-prove goal orientation, performance, and the moderating role of shared team identification. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(6), 1811–1824. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038888

- Dragoni, L. (2005). Understanding the emergence of state goal orientation in organizational work groups: The role of leadership and multilevel climate perceptions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(6), 1084–1095. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.6.1084

- Dragoni, L., & Kuenzi, M. (2012). Better understanding work unit goal orientation: Its emergence and impact under different types of work unit structure. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(5), 1032–1048. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028405

- Edwards, J. R., & Lambert, L. S. (2007). Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: A general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychological Methods, 12(1), 1–22. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.12.1.1

- Faraj, S., & Yan, A. (2009). Boundary work in knowledge teams. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(3), 604–617. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014367

- Gardner, R. G., Harris, T. B., Li, N., Kirkman, B. L., & Mathieu, J. E. (2017). Understanding “it depends” in organizational research: A theory-based taxonomy, review, and future research agenda concerning interactive and quadratic relationships. Organizational Research Methods, 20(4), 610–638. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428117708856

- Gong, Y., Kim, T. Y., Lee, D. R., & Zhu, J. (2013). A multilevel model of team goal orientation, information exchange, and creativity. Academy of Management Journal, 56(3), 827–851. doi:https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.0177

- Grant, A. M., & Berry, J. W. (2011). The necessity of others is the mother of invention: Intrinsic and prosocial motivations, perspective taking, and creativity. Academy of Management Journal, 54(1), 73–96. doi:https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.59215085

- Hogg, M. A., van Knippenberg, D., & Rast, D. E. (2012). Intergroup leadership in organizations: Leading across group and organizational boundaries. Academy of Management Review, 37(2), 232–255. doi:https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2010.0221

- James, R. L., Demaree, R. G., & Wolf, G. (1993). rwg: An assessment of within-group interrater agreement. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(2), 306–309. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.78.2.306

- Landis, R. S., Beal, D. J., & Tesluk, P. E. (2000). A comparison of proves to forming composite measures in structural equation models. Organizational Research Methods, 3(2), 186–207. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/109442810032003

- Lee, S. M., & Farh, C. I. C. (2019). Dynamic leadership emergence: Differential impact of members’ and peers’ contributions in the idea generation and idea enactment phases of innovation project teams. Journal of Applied Psychology, 104(3), 411–432. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000384

- Lu, S., Bartol, K. M., Venkataramani, V., Zheng, X., & Liu, X. (2019). Pitching novel ideas to the boss: The interactive effects of employees’ idea enactment and influence tactics on creativity assessment and implementation. Academy of Management Journal, 62(2), 579–606. doi:https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2016.0942

- Marrone, J. A. (2010). Team boundary spanning: A multilevel review of past research and proposals for the future. Journal of Management, 36(4), 911–940. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206309353945

- Mueller, J., Melwani, S., Loewenstein, J., & Deal, J. J. (2018). Reframing the decision-makers’ dilemma: Towards a social context model of creative idea recognition. Academy of Management Journal, 61(1), 94–110. doi:https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2013.0887

- Mueller, J. S., Wakslak, C. J., & Krishnan, V. (2014). Construing creativity: The how and why of recognizing creative ideas. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 51(1), 81–87. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2013.11.007

- Mumford, M. D., Scott, G. M., Gaddis, B., & Strange, J. M. (2002). Leading creative people: Orchestrating expertise and relationships. The Leadership Quarterly, 13(6), 705–750. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S1048-9843(02)00158-3

- Perry-Smith, J. E., & Mannucci, P. V. (2017). From creativity to innovation: The social network drivers of the four phases of the idea journey. Academy of Management Review, 42(1), 53–79. doi:https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2014.0462

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- Shin, S. J., & Zhou, J. (2007). When is educational specialization heterogeneity related to creativity in research and development teams? Transformational leadership as a moderator. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(6), 1709–1721. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.6.1709

- Somech, A., & Drach-Zahavy, A. (2011). Translating team creativity to innovation implementation: The role of team composition and climate for innovation. Journal of Management, 39(3), 684–708. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206310394187

- Somech, A., & Khalaili, A. (2014). Team boundary activity: Its mediating role in the relationship between structural conditions and team innovation. Group and Organization Management, 39(3), 274–299. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601114525437

- van Knippenberg, D. (2017). Team innovation. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 4(1), 211–233. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032516-113240

- Vandenberg, R. J., & Lance, C. E. (2000). A review and synthesis of the measurement invariance literature: Suggestions, practices, and recommendations for organizational research. Organizational Research Methods, 5(1), 139–158. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428102005002001

- Vandewalle, D. (1997). Development and validation of a work domain goal orientation instrument. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 57(6), 995–1015. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164497057006009

- Vandewalle, D., & Cummings, L. L. (1997). A test of the influence of goal orientation on the feedback-seeking process. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82(3), 390–400. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.82.3.390

- West, M. A. (2002). Sparkling fountains or stagnant ponds: An integrative model of creativity and innovation implementation within groups. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 51(3), 355–387. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1464-0597.00951

- Zhou, J., Wang, X. M., Song, L. J., & Wu, J. (2017). Is it new? Personal and contextual influences on perceptions of novelty and creativity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 102(2), 180–202. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000166