ABSTRACT

The personality trait of schizotypy has received considerable attention in creativity research; however, to date, literature has exclusively focused on its relationship with benevolent creative ideation. The present study investigated how different subdimensions of schizotypy were related to malevolent creativity, where original ideas are generated to harm others intentionally. N = 104 participants completed a novel performance test for malevolent creativity and reported the frequency of engaging in malevolent creativity in daily life. Schizotypy was assessed with a multidimensional inventory (sO-LIFE). The sO-LIFE subdimension of Impulsive Non-conformity positively correlated with individuals’ performance on the malevolent creativity test as well as with their typical malevolent creativity behavior, confirming our expectations that individuals high in impulsive antisocial schizotypy demonstrate a greater capacity and willingness to use creativity toward malicious goals. Results also indicated a weak contribution of Unusual Experiences to malevolent creativity performance, yet correlations were only significant at the trend level. Unexpectedly, Cognitive Disorganization was positively correlated with malevolent creativity behavior in daily life. This pattern of relationships shows that individual differences in schizotypal personality traits are also related to darker sides of creativity, which may inform future investigations embedded into the rich framework linking creativity and psychopathology.

Introduction

Profiling the “creative genius” by means of certain personality traits is still one of the most intriguing avenues of contemporary creativity research. In terms of positively connotated traits, a multitude of empirical studies established openness to experience and extraversion as the two strongest predictors of creative ability (Karwowski & Lebuda, Citation2016; Puryear, Kettler, & Rinn, Citation2017). These findings, however, are paralleled by an equally rich research tradition linking creativity to different measures of psychopathology, most prominently, psychotic thinking and delusion proneness, which occur in clinical manifestations of schizophrenia, but are also prevalent to the personality trait of schizotypy (Claridge, Citation1997).

Deemed “schizophrenia’s less deviant bedfellow” (Claridge, Citation1997, p. 3), schizotypy is characterized by aberrant and unsystematic thought processes and is commonly conceptualized as an increased vulnerability toward developing psychotic disorders (Fisher et al., Citation2004; Nelson & Rawlings, Citation2010; Nettle, Citation2006). Broader, multidimensional models of schizotypy (Claridge & Blakey, Citation2009; Mason, Claridge, & Jackson, Citation1995) describe four components of schizotypal personality traits. The first component includes positive symptoms like unusual or hallucinatory experiences and magical ideation and is thus mostly labeled “positive schizotypy.” Individuals with this profile are prone to perceptual aberrations and odd beliefs and fantasies. The second component emphasizes negative symptoms like introvertive anhedonia, denoting intimacy avoidance and constricted affect and also emphasizing solitude and independence, and is commonly labeled “negative schizotypy.” Third, the component of cognitive disorganization describes attention deficits, poor decision-making and social anxiety, often accompanied by a sense of purposelessness, and is labeled “disorganized schizotypy.” Fourth and finally, impulsive non-conformity reflects impulsive, reckless, and antisocial behavior that is characterized by eccentricity, violence, and a lack of self-control, which is why it is labeled “antisocial schizotypy” (see, e.g., Mason, Citation2015; Polner et al., Citation2019).

Among these dimensions, positive schizotypy is the one most consistently linked to higher levels of creativity across several measurement schemes: Positive schizotypy in terms of unusual experiences was positively associated with self-rated creativity (Batey & Furnham, Citation2008; Claridge & Blakey, Citation2009; Schuldberg, Citation1990) as well as creative performance in psychometric tests for verbal and figural creativity (Abu-Akel et al., Citation2020; Batey & Furnham, Citation2009; Mohr & Claridge, Citation2015; Rominger, Fink, Weiss, Bosch, & Papousek, Citation2017). Similarly, elevated levels of positive schizotypy were found in samples of artists and poets (Burch, Pavelis, Hemsley, & Corr, Citation2006; Holt, Citation2019; Nelson & Rawlings, Citation2010; Nettle, Citation2006). It has been argued that positive schizotypy and creativity may overlap in their cognitive style, which is defined by spontaneous and loose associations, allusive thinking, and mind wandering (Eysenck, Citation1993; Nelson & Rawlings, Citation2010; Rominger, Weiss, Fink, Schulter, & Papousek, Citation2011), but still retains necessary cognitive control in order to guide behavior (Fink, Perchtold, & Rominger, Citation2018). This may also explain why mild manifestations of disorders on the schizophrenia spectrum, like schizotypy, are linked to heightened levels of creativity (Abraham, Citation2014; Claridge & Blakey, Citation2009), but full-blown schizophrenia is not (Acar, Chen, & Cayirdag, Citation2018). The overlap of cognitive processes in creativity and schizotypy is also supplemented by neuroscientific investigations reporting that both show similar effects on the level of the brain (Fink, Benedek, Unterrainer, Papousek, & Weiss, Citation2014a; Fink et al., Citation2014b; Park, Kirk, & Waldie, Citation2015; Rominger et al., Citation2017). In this regard, Fink et al. (Citation2014b) found that highly original ideas and high schizotypy were associated with similar functional brain activity during creative ideation, noting that both creative originality and schizotypy could be a function of (over)including a vast number of stimuli or associations in one’s mental processes (also see Fink et al., Citation2018). Altogether, the link between positive schizotypy and the desirable ability for creative thinking and innovation has led to speculations that positive schizotypy may reflect a more healthy, beneficial trait (Mohr & Claridge, Citation2015), as opposed to negative or disorganized schizotypy, which seems to hamper creativity (Aguilera & Rodríguez-Ferreiro, Citation2021; Batey & Furnham, Citation2008; Nelson & Rawlings, Citation2010; Schuldberg, Citation1990).

Another dimension of schizotypy relevant to creativity is impulsive non-conformity (Claridge & Blakey, Citation2009; Sacks, Weisman de Mamani, & Garcia, Citation2012), reflecting the (sub)clinical reality that individuals on the schizophrenia spectrum often display disinhibited, antisocial, and aggressive characteristics that are also akin to symptoms of psychoticism (Mason, Citation2015). Supporting the idea that a high tendency toward non-conformity inherently promotes “thinking out of the box,” previous studies found impulsive non-conformity positively associated with convergent and divergent thinking performance as well as creative personality (Batey & Furnham, Citation2008; Burch et al., Citation2006; Claridge & Blakey, Citation2009; Michalica & Hunt, Citation2013; O’Reilly, Dunbar, & Bentall, Citation2001; Schuldberg, Citation1990; Stanciu & Papasteri, Citation2018; but see Polner, Simor, & Kéri, Citation2018). Impulsive non-conformity was also found to be elevated in professions of poetry and visual arts (Nettle, Citation2006; but see Rawlings & Locarnini, Citation2008). This link of creativity with a “darker side of personality” involving antisocial and aggressive behavior may fit the notion of what research calls “the darker side to creativity” (Cropley, Citation2010; Eysenck, Citation1995). However, there is the intriguing predicament that research linking schizotypal thinking to creativity exclusively assessed creativity as a benevolent and constructive ability contributing to the greater good. This is also evident in the widely accepted notion that creativity requires both novelty and usefulness/effectiveness of ideas as defined within a social context (e.g., finding original and useful applications for everyday objects; alternate uses; see Plucker, Beghetto, & Dow, Citation2004; Runco & Jaeger, Citation2012). Yet, to date, research did not focus on darker outcomes of creative ideation itself.

For this reason, the present study investigated the relationship between schizotypal personality traits and malevolent creativity, that is, creativity purposefully geared toward inflicting material, mental, or physical harm on others (e.g., Cropley, Kaufman, & Cropley, Citation2008). More precisely, malevolent creativity denotes the utilization of creative thinking ability for the pursuit of malicious, antisocial, and destructive goals (Cropley, Kaufman, White, & Chiera, Citation2014; Runco, Citation2010), which are best exemplified in unprecedented terrorism (Logan, Ligon, & Derrick, Citation2020), novel biochemical warfare, or unmatched criminal activities. Yet, similar to the understanding that psychotic- and schizophrenic-like thoughts regularly occur in the general population (Fonseca-Pedrero et al., Citation2018; van Os, Linscott, Myin-Germeys, Delespaul, & Krabbendam, Citation2009), malevolent creativity is also part of everyday life, apparent in instances of creative lying, harassment, theft, revenge, property destruction, or even aggressive humor (Cropley et al., Citation2014; Harris, Reiter-Palmon, & Kaufman, Citation2013; Perchtold-Stefan, Fink, Rominger, & Papousek, Citation2020a). Importantly, the concept of malevolent creativity concedes that the damage caused by some creative ideas and products is intentional and not simply an accidental byproduct of versatile creative ideation (James, Clark, & Cropanzano, Citation1999; Kapoor & Khan, Citation2016).

In keeping with traditional creativity research, the majority of studies on malevolent creativity have emphasized personality traits and stable characteristics that may facilitate malevolent creative ideation. Notwithstanding considerable discrepancy in measurement approaches, malevolent creativity has been quite robustly linked to disagreeableness in terms of antisocial and aggressive behavior (Hao et al., Citation2020; Hao, Tang, Yang, Wang, & Runco, Citation2016; Harris & Reiter-Palmon, Citation2015; Jonason, Abboud, Tomé, Dummett, & Hazer, Citation2017), establishing antagonistic punishment tendencies as a prominent feature of malevolent creativity (Lee & Dow, Citation2011; Perchtold‐Stefan, Fink, Rominger, & Papousek, Citation2020b). While no study to date has specifically examined links for the personality trait of schizotypy, some accounts provisionally suggest that hostile and impulsive traits may overlap with malevolent creativity, strongly hinting at a role of impulsive non-conformity. For example, Harris and Reiter-Palmon (Citation2015) noted that individuals high in impulsivity and implicit aggression were less inhibited in expressing malevolently creative ideas, presumably due to a general disregard for the consequences of their actions. Further, Papousek et al. (Citation2014) reported that individuals high in positive schizotypy displayed greater sensitivity to threatening stimuli as indicated by EEG coherence changes during confrontation with anger. The authors interpreted their findings in terms of greater likelihood of inappropriate behavior in provocative interpersonal situations, where interestingly, malevolent creativity is most likely to occur in (see Baas, Roskes, Koch, Cheng, & Dreu, Citation2019; Harris & Reiter-Palmon, Citation2015). Perchtold‐Stefan et al. (Citation2020b) reported a small positive correlation between malevolent creativity and the psychoticism scale of the Personality Inventory for the DSM-5, which measures eccentricity, cognitive perceptual dysregulation, and unusual beliefs and experiences (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013), further hinting at the relevance of schizotypal features in malevolent creativity.

This study aimed for a comprehensive assessment of malevolent creativity, using both a maximum performance test and a self-report approach in order to investigate links with schizotypy. For a novel, psychometric test of malevolent creativity, we used a real-world idea generation task called the Malevolent Creativity Test (MCT; see Perchtold-Stefan et al., Citation2020ab), which captures individuals’ capacity for malevolent creative ideation in four hypothetical, but unfair social situations that depict harmful behavior of another person. The MCT then asks participants to generate as many different original ideas as possible with the goal of sabotaging or taking revenge on the wrongdoer (for similar approaches, see Hao et al., Citation2020, Citation2016; Harris & Reiter-Palmon, Citation2015). To capture individuals’ self-reported malevolent creativity behavior, the Malevolent Creativity Behavior Scale (MCBS; Hao et al., Citation2016) was administered, assessing the frequency of lying, hurting others, and playing tricks on others in daily life. This dual approach to malevolent creativity allowed us to determine whether aspects of schizotypy were linked to both the theoretical capacity for malevolent creativity ideation (performance) and the typical use of malevolent creativity in daily life (trait). For a broader, multidimensional assessment of schizotypy, we used the short version of the Oxford-Liverpool Inventory of Feelings and Experiences (Mason, Linney, & Claridge, Citation2005), in order to examine how different subdimensions of schizotypy, i.e., Unusual Experiences, Cognitive Disorganization, Introvertive Anhedonia, and Impulsive Non-Conformity, are related to malevolent creativity.

Due to the lack of previous research clearly differentiating effects of performance and self-report measures of malevolent creativity, and due to this being the first investigation linking schizotypy and malevolent creativity, we did not posit separate hypotheses for the MCT and the MCBS. Accordingly, we expected that two schizotypy subscales, in particular, would be positively related to ability (MCT) and self-report, trait-level indicators (MCBS) of malevolent creativity. We expected that Impulsive Non-Conformity (antisocial schizotypy) would be positively correlated with malevolent creativity in light of an obvious overlap in antisocial behavior and rule-breaking (e.g., Acar & Sen, Citation2013; Perchtold‐Stefan et al., Citation2020b). Further, we hypothesized that Unusual Experiences would be positively correlated with malevolent creativity based on robust links with general creative potential (Acar & Sen, Citation2013).

Methods

Participants

An a priori power analysis for a multiple regression approach (G*Power, 1 – β = .80; α = .05) suggested a minimum of 102 participants to detect a medium sized effect of f2 = .15 (based on previous correlations of r = ~.33 between schizotypal traits and creativity measures;see Batey & Furnham, Citation2008; Fink et al., Citation2014a; Michalica & Hunt, Citation2013; O’Reilly et al., Citation2001; Rominger et al., Citation2017). Participants were mostly recruited not only via social media and university mail servers but also via local news groups and notices in local cafes and supermarkets. In total, 107 participants were tested; however, three had to be excluded from analyses due to noncompliance with test instructions or missing questionnaire data. The final sample consisted of 104 participants (56 women), aged between 18 and 39 years (M = 22.51, SD = 4.38). Most of the participants were undergraduate university students (87.5%), and the rest were high-school graduates from the working population. The study was approved by the local ethics committee, and informed consent was obtained from all participants. All participants completed the demographic questionnaire and schizotypy measure (sOLIFE) before reporting their malevolent creativity behavior in daily life (MCBS) and finally completing the MCT performance test.

Measures

Descriptive statistics, including means, standard deviations, minimum and maximum scores, and reliabilities (Cronbach’s alpha) of the utilized measures, are jointly reported in .

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for O-LIFE schizotypy and malevolent creativity.

Schizotypy

The shortened version of the Oxford-Liverpool Inventory of Feelings and Experiences (sO-LIFE; Mason et al., Citation1995, Citation2005) was used to assess schizotypal personality traits in a non-clinical sample. The sO-LIFE consists of 43 items answered in a yes/no format, which form four subscales of Unusual Experiences (positive schizotypy, 12 items, e.g., “Have you ever thought that you had special, almost magical powers?”), Introvertive Anhedonia (negative schizotypy, 10 items, e.g., “Have you often felt uncomfortable when your friends touch you?”), Cognitive Disorganization (11 items, e.g., “Do you often have difficulties in controlling your thoughts?”), and Impulsive Non-conformity (antisocial schizotypy, 10 items, e.g., “Do you at times have an urge to do something harmful or shocking?”). The sO-LIFE has demonstrated good psychometric qualities, reliability, and validity in previous studies with non-clinical adults and has been widely used to illustrate relationships with certain preferences, behaviors, and cognitive abilities such as creativity (Mason, Citation2015; Mason & Claridge, Citation2006; Polner et al., Citation2019). For descriptive statistics of the sO-LIFE, see .

Malevolent creativity in a performance test

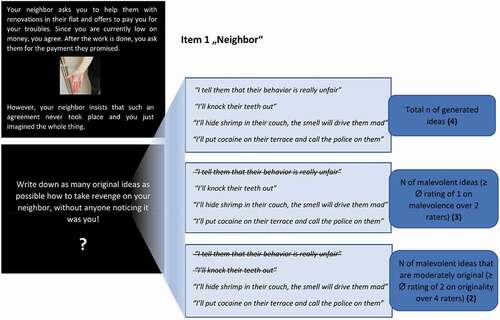

Participants’ capacity to spontaneously generate manifold malevolently creative ideas was measured using the Malevolent Creativity Test (MCT; Perchtold-Stefan et al., Citation2020a, Citation2020b). The MCT is a validated psychometric performance test consisting of four realistic, open-ended problems that depict different sorts of unfair behavior from peers/associates (Baas et al., Citation2019; Harris & Reiter-Palmon, Citation2015). Validity of the MCT was established by previous correlations with verbal divergent thinking, antagonistic personality, and angry mood (Perchtold‐Stefan et al., Citation2020b). See and Perchtold‐Stefan et al. (Citation2020b) for item descriptions. After a practice item, each situation was presented on a computer screen for 30 s, supplemented by a matching photograph. Participants were told to imagine the situation happening to them and to try and picture it as vividly as possible. During the appearance of a white question mark on screen, participants then generated as many original ways as possible to sabotage that person/take revenge for the unfair treatment on a sheet in front of them. After 3 minutes, a short tone indicated a new vignette appearing on the screen.

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the Malevolent creativity task (MCT) and the scoring procedure. Individuals face an unfair situation for 30 s and are subsequently given 3 min to generate and write down as many original ideas as possible as how to take revenge/sabotage the wrongdoer. Of four generated ideas to the ”neighbor” item, three meet the criterion for malevolence and count toward fluency. Two of these ideas meet the criterion for moderate originality and count toward total malevolent creativity. Separate scores are calculated for malevolence (Ø of malevolence ratings over 4 raters) and originality (Ø of originality ratings over 4 raters) per participant and item. Figure adapted from Perchtold‐Stefan et al. (Citation2020b) and used with permission of the authors and under the terms of the Creative Commons Attributions License.

On average, participants generated a total of M = 16.28 ideas (SD = 7.44). Only ideas that met the instructions of being (at least slightly) malevolent were scored as valid (M = 91.1% of generated ideas as rated by two independent raters). For indicators of creative ideation, the MCT scores originality (akin to novelty in standard definitions of creativity; see Runco & Jaeger, Citation2012) and malevolence/harmfulness of ideas. We consider the malevolence indicator as largely equivalent to the criterion of effectiveness in the standard creativity definition, since in the MCT, participants are explicitly instructed to harm wrongdoers in creative ways. Accordingly, a high degree of harmfulness is inherently effective in the context of the MCT where the infliction of harm/taking revenge is the established goal (for a similar argument, see Harris & Reiter-Palmon, Citation2015). Malevolence of ideas was scored on a 4-point Likert scale by four independent raters, with 1 indicating slight malevolence (e.g., talking badly with friends about the wrongdoer) and 4 indicating high malevolence (e.g., kidnap the wrongdoer and beat some sense into them; ICC = .88). Ratings were averaged over all answers per situation, over all situations (4), and raters (4) to yield a single malevolence score for the MCT. Accordingly, higher sores on the malevolence criterion reflect greater average harmfulness over all generated ideas. After rating all ideas for malevolence, the same four raters were also trained to rate the generated ideas for originality on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = not original, 4 = very original). Rating for originality took place in separate data files and with a time-delay to minimize rating-bias from scoring malevolence. Like for malevolence, ratings were averaged over all answers per situation, over all situations (4) and raters (4) to yield a single originality score for the MCT. Interrater reliability was ICC = .91. Higher scores on the originality criterion reflect greater average uniqueness over all generated ideas. A final score of malevolent creativity was computed by summing up all malevolent ideas with an average originality rating of ≥ 2 (= moderately original). This approach is based on the notion that “true” malevolent creativity requires ideas to qualify as both, malevolent, and original (see Harris & Reiter-Palmon, Citation2015; Harris et al., Citation2013). Thus, matching previous studies (Perchtold-Stefan et al., Citation2020a, Citation2020b), malevolent creativity was operationalized as the number of generated ideas that were both malevolent and original, delineating the overall degree of malevolent creativity and serving as the main variable of interest. While it is theoretically possible to also incorporate the degree of malevolence into this total score (i.e., only adding ideas with an average originality and malevolence of ≥ 2), we feel that malevolent creativity in the general population is better represented if all malevolent ideas count toward total malevolent creativity, in light of the many forms it can realistically take (lying, cheating, manipulation, aggressive humor, harmful tricks, bullying, property destruction, theft, etc.). The procedure of the MCT along with the scoring approach are illustrated in . See for descriptive statistics of the MCT.

Malevolent creativity as self-reported typical behavior

In the Malevolent Creativity Behavior Scale (MCBS; Hao et al., Citation2016), participants report how often they engage in malevolent creativity behaviors in everyday life (e.g., deceptions, tricks, lies, revenge, etc.). The MCBS consists of 13 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 0 (never) to 4 (usually, e.g., “How often do you engage in original forms of sabotage?” or “How often do you play tricks on people as revenge?”).

Statistical analysis

To determine how specific aspects of schizotypy are linked to malevolent creativity, multiple regression analyses were run. The four sO-LIFE subscales (Unusual Experiences, Introvertive Anhedonia, Cognitive Disorganization, and Impulsive Non-conformity) were simultaneously entered as predictors. The resulting semi-partial correlations indicated whether malevolent creativity was uniquely related to specific aspects of schizotypy, independent of others as well as gender. We included gender as an additional predictor to control for potential gender differences in malevolent creativity (Harris & Reiter-Palmon, Citation2015; Lee & Dow, Citation2011) as well as schizotypal personality (Fonseca-Pedrero et al., Citation2018; Furnham & Trickey, Citation2011; Mason & Claridge, Citation2006). Malevolent creativity in the MCT and malevolent creativity behavior in the MCBS were used as dependent variables. As supplementary analyses, multiple regression analyses were also run for the originality and malevolence scores on the MCT and for the specific subscales of the MCBS (hurting people, lying, playing tricks). The statistical assumptions for the multiple regression models (i.e., ratio of cases to independent variables, normality, independence of errors, homoscedasticity, linearity, and absence of multicollinearity) were met. Supplementary analyses included t-tests for gender differences in schizotypy and intercorrelations between the malevolent creativity measures and between schizotypy subscales. Results were considered statistically significant if p < .05 (two-tailed).

Results

Schizotypy and individuals’ capacity for malevolent creative ideation (MCT)

Gender significantly correlated with malevolent creativity in the MCT (sr = −.30, p = .002), indicating that men showed a higher capacity for malevolent creativity than women (men: M = 6.44, SD = 4.13; women: M = 4.45, SD = 4.23). Independent of gender and other schizotypal personality traits, only the subscale Impulsive Non-conformity explained unique variance in MCT performance (sr = .20, p = .032). While the subscale Unusual Experiences indicated a similar pattern of positive correlations with MCT performance, its contribution was only significant at trend level (sr = .16, p = .081).

Additional regression analyses for the criteria of originality and malevolence of ideas on the MCT yielded a similar pattern of results for originality (Impulsive non-conformity: sr = .18, p = .048; Unusual Experiences: sr = .16, p = .076, p’s of other subscales ≥.591); however, malevolence was only uniquely predicted by Impulsive non-conformity (sr = .21, p = .021, p’s of all other subscales ≥.262). See for all multiple regression models with total malevolent creativity, originality, and malevolence of ideas.

Table 2. Performance on the malevolent creativity test (MCT) and subscales of O-LIFE schizotypy.

Schizotypy and individuals’ self-reported malevolent creativity behavior (MCBS)

Gender significantly correlated with typical malevolent creativity behavior (sr = −.42, p < .001), indicating that men also reported greater use of malevolent creativity in daily life (men: M = 13.94, SD = 4.13; women: M = 8.36, SD = 5.41). While all sO-LIFE subscales showed significant positive zero-order correlations with malevolent creativity behavior, only Cognitive Disorganization (sr = .17, p = .044) and Impulsive Non-conformity (sr = .25, p = .003) explained unique variance in participants’ implementation of malevolent creativity in daily life. Multiple regression analyses for specific subscales of the MCBS revealed that Impulsive Non-Conformity emerged as a unique predictor of hurting people (sr = .25, p = .005) and playing tricks on others (sr = .29, p = .001), while Cognitive Disorganization emerged as a unique predictor of lying (sr = .30, p = .001). Additionally, hurting people was also predicted by Unusual Experiences (sr = .18, p = .026). See for all multiple regression models with total MCBS scores and the three subscales.

Table 3. Malevolent creativity behavior (MCBS) and subscales of O-LIFE schizotypy.

Supplementary analyses

Women reported more Unusual Experiences (women: M = 4.14, SD = 2.50, men: M = 2.75, SD = 2.58; t(102) = −2.79, p = .006) and more Cognitive Disorganization (women: M = 5.79, SD = 3.36, men: M = 4.48, SD = 3.19; t(102) = −2,03, p = .045) than men. Participants demonstrating a higher capacity for malevolent creativity in the MCT also reported using malevolent creativity more frequently in daily life (r = .36, p < .001). This pattern was also present for the subscales of MCT malevolence (r = .32, p = .001) and MCT originality (r = .24, p = .015). MCT malevolence and MCT originality were correlated at r = .63 (p <.001). All sO-LIFE subscales were positively correlated, except for Introvertive Anhedonia and Impulsive Non-conformity. See for a full correlational matrix of all study variables.

Table 4. Full correlational matrix of all study variables.

Discussion

Following the rich tradition of linking personality traits to various aspects of creativity, the present study focused on darker sides of creative ideation and investigated how subdimensions of schizotypy were related to malevolent creativity aimed at purposefully damaging others. First, our results confirmed the expected positive associations of the sO-LIFE subdimension Impulsive Non-conformity with malevolent creativity, which explained unique variance in both capacity (MCT) and self-reported trait-level aspects (MCBS) of malevolent creative ideation. While it may appear that self-reports of Impulsive Non-conformity naturally correlate with self-reports of disruptive behavior in the MCBS due to facet duplication, the link to participants’ malevolent creativity performance in the MCT suggests a different interpretation, pointing toward a shared psychological propensity for social transgressions, which may include dominating, exploiting, and punishing others.

In previous studies, performance of the MCT showed correlations of medium size with verbal divergent thinking (see Perchtold-Stefan et al., Citation2020a, Citation2020b), underlining its value as a psychometric measure for divergent thinking in malevolent contexts. Hence, our results for Impulsive Non-conformity match previous observations that this antisocial, impulsive type of schizotypy is positively associated with divergent thinking in terms of alternate uses or verbal creativity (Batey & Furnham, Citation2009; Claridge & McDonald, Citation2009; LeBoutillier, Barry, & Westley, Citation2016, Citation2014; Schuldberg, Citation1990; also see Acar & Sen, Citation2013). For an explanation, it was noted that Impulsive Non-conformity reflects the absence of self-censorship and the expression of what comes to mind immediately, leading to a break of conceptual boundaries, potentially more risky and inappropriate ideas and, thus, higher creativity (see Burch et al., Citation2006). A greater willingness to express socially unacceptable ideas and taboo responses is also a likely catalyst for increased malevolent creativity in response to unfair social situations like depicted in the MCT. It has also been proposed that individuals higher in impulsivity and implicit aggression were more easily provoked into malevolent creativity due to low regard for the consequences of their malevolent actions (Harris & Reiter-Palmon, Citation2015). Reduced inhibitions for saying what comes to mind may also be related to greater authenticity as a personality trait, which interestingly, showed positive links with ideational fluency and uniqueness of ideas in a malevolent creativity problem (Xu, Zhao, Xia, & Pang, Citation2021). Impulsive Non-conformity was also linked to more pronounced power values as desirable life goals, which are believed to reflect the need to control or dominate others (Hanel & Wolfradt, Citation2016). It was assumed that such traits may lead to the exploitation and harm of others, incurring severe damage to social relations (Schwartz & Bardi, Citation2001). Accordingly, these links to social transgressions and disruptive behavior may explain why individuals high in Impulsive Non-conformity performed better in the MCT, since it specifically solicits the generation of original ideas to take revenge on, sabotage, or punish others (also see Perchtold-Stefan et al., Citation2020a).

Of note, it was posited that Impulsive Non-conformity is not related to greater divergent thinking per se, but rather, to the expression of inappropriate ideas, which may occasionally prompt higher quality/uniqueness ratings in specific tasks (Holt, Citation2015; Polner et al., Citation2018; also see Acar & Sen, Citation2013). However, in this study, the link between Impulsive Non-conformity and malevolent creativity was not restricted to rated malevolence (harmfulness) or originality of ideas but emerged for the total number of generated original ideas. Other studies examining the role of impulsive/aggressive traits in malevolent creativity reported links for fluency indicators as well (see Harris & Reiter-Palmon, Citation2015; Perchtold-Stefan et al., Citation2020a). This lends support to the existence of not only motivational but also cognitive factors that promote a greater number of malevolently creative ideas in high Impulsive Non-conformity. Additionally, the Impulsive Non-conformity component of schizotypy is most akin to Eysenck’s definition of psychoticism (Eysenck, Citation1995), which has been associated with various aspects of creativity, particularly, originality of creative ideas (Acar & Runco, Citation2012; Fink et al., Citation2014a; Fink, Slamar-Halbedl, Unterrainer, & Weiss, Citation2012), but also more antisocial, taboo responses in a divergent thinking task (Rawlings & Toogood, Citation1997).

On a final note on Impulsive Non-conformity and its antisocial elements, our results also showed that the links to self-reported malevolent creativity behavior were most prominent for the subdimensions of hurting others and playing tricks on others. This suggests that individuals high in this schizotypy subdimension not only possess greater hypothetical capacity for malevolent creativity but also more frequently implement this potential in daily life. Though preliminary, these findings warrant further attention with regard to physical/social aggression and delinquent behavior that may arise from this combination of traits (see, e.g., Sacks et al., Citation2012).

Results only partially confirmed our expectations that the subdimension of Unusual Experiences (positive schizotypy) would be positively correlated with individuals’ malevolent creativity. We observed a positive zero-order correlation with self-reported malevolent creativity behavior; however, in the multiple regression model, Unusual Experiences did not explain significant variance past the contribution of Impulsive Non-conformity and Cognitive Disorganization. Similarly, in the regression model for malevolent creativity performance, a contribution of Unusual Experiences was only found at the trend level, which somewhat deviates from the often robust links between positive schizotypy and “classic” creative ideation (see Abu-Akel et al., Citation2020; Acar & Sen, Citation2013; Mohr, Graves, Gianotti, Pizzagalli, & Brugger, Citation2001; Rominger et al., Citation2017). While studies reported that high positive schizotypy is linked to low agreeableness (Barrantes-Vidal, Lewandowski, & Kwapil, Citation2010; Ross, Lutz, & Bailley, Citation2002), matching a core feature of malevolent creativity (see Lee & Dow, Citation2011; Perchtold‐Stefan et al., Citation2020b), it was also suggested that positive schizotypy and particularly unusual experiences are linked to more positive and enriching mental experiences and more positive relationships with others (Mohr & Claridge, Citation2015, also see Tabak & Weisman de Mamani, Citation2013). The latter may counter the negative context of malevolent creative ideation, which is more strongly correlated with feelings of anger, aggression, and social threat (Baas et al., Citation2019; Hao et al., Citation2020; Perchtold‐Stefan et al., Citation2020b). This may serve as an explanation why in the present study, links between Unusual Experiences and malevolent creativity were weak at best.

We did not expect the unique positive contribution of Cognitive Disorganization to self-reported malevolent creativity behavior in daily life, which originated from the lying subscale of the MCBS. In the literature, findings for the role of disorganized schizotypy in creativity have been mixed (e.g., Aguilera & Rodríguez-Ferreiro, Citation2021; Batey & Furnham, Citation2008; Beaussart, Kaufman, & Kaufman, Citation2012; Carter, Hass, Charfadi, & Dinzeo, Citation2019; LeBoutillier et al., Citation2014). While a creativity link between disorganized schizotypy and dishonesty is possible (e.g., looseness of associations, cognitive leaps, etc., also see Gino & Wiltermuth, Citation2014), it is equally plausible that disorganized schizotypy and the lying subscale in the MCBS overlap in inattentive thinking and difficulties in decision-making, which are not necessarily creativity-related. In this regard, it has also been noted that the MCBS, while showing good reliability, does not capture novelty or originality of actions/ideas, but simply their frequency, making it less a measure of malevolent creativity than of malicious behavior (see Reiter-Palmon, Citation2018). On the other hand, several previous studies have established medium positive correlations of the MCBS with self-reported creative potential on the Runco Ideational Behavior Scale (RIBS; see Hao et al., Citation2020, Citation2016) and with originality in a verbal divergent thinking task (Perchtold‐Stefan et al., Citation2020b). In the present study, total MCBS scores were also clearly linked to originality in the MCT (r = .24), suggesting that the MCBS does at least partly tap into the novelty of (malevolent) creative ideation. Further, while creativity is naturally best assessed with multiple indices, there is the argument that ideational fluency and frequency of ideas are valid indicators of creativity on their own (see Jauk, Benedek, & Neubauer, Citation2014). This, together with the fact that our schizotypy links for the MCBS strongly overlap with links for the MCT, underscores the MCBS as a useful measure for capturing self-reported malevolent creativity behavior.

Study strengths

The present study is the first to examine the relationships between schizotypal personality traits and malevolent creativity, both when assessed as a cognitive potential in a psychometric test (MCT) and as a self-reported habit in daily life (MCBS). We consider this dual assessment of malevolent creativity a strength of our study, which also lends credibility to our observed general pattern of results. The correlation of schizotypal traits with both capacity and behavior aspects of malevolent creativity suggests that individuals high in certain aspects of schizotypy also translate their cognitive potential for malevolent creativity into real-life behavior, underlining the practical relevance of the results (also see Perchtold‐Stefan et al., Citation2020b). At the same time, it can be shown that the observed relationships are not simply due to the method overlap, in that self-report measures correlate with each other.

Study limitations and future research directions

Our findings, although preliminary and in need of replication in larger, more diverse samples, highlight a significant contribution of Impulsive Non-conformity to individuals’ capacity for malevolent creative ideation and self-reported malevolent creativity behavior. It seems warranted to examine this schizotypy – malevolent creativity link with other self-report scales of schizotypy, which may help clarify the role of unusual perceptual experiences in malevolent creativity. Yet, it was demonstrated that the inclusion of Impulsive Non-conformity in analyses of schizotypy does not dilute the classical three factor structure of positive, negative, and disorganized schizotypy (see Polner et al., Citation2019). Future investigations in larger samples will also provide exciting opportunities to specifically test whether our proposed relationships between schizotypy and malevolent creativity vary between genders. The internal consistency of the Impulsive Non-conformity subscale may appear rather low (α = .68). However, it has been noted that the Cronbach’s alpha may be severely underestimated for measures with dichotomous items, like the sO-LIFE in the present study (see Sun et al., Citation2007), which makes us confident in our results. The present results do not allow for any interference of causality due to the cross-sectional nature of the investigation. While creativity research generally treats personality traits as predictors of creative thinking (e.g., Puryear et al., Citation2017), similar conclusions for schizotypy and malevolent creativity are reserved for future longitudinal investigations. Finally, regarding the scoring of the MCT, two thoughts are noteworthy. First, it may be argued that especially when parsing malevolent creativity in the general population, the most malevolent ideas may not always be the most effective/practicable, as they may entail higher risk of facing personal repercussions (i.e., beating someone) or are simply rather hard to implement (emptying someone’s bank account under a fake name). While we consider the criterion of malevolence in the MCT as largely equivalent to effectiveness in standard definitions of creativity (see, e.g., Runco & Jaeger, Citation2012), since individuals are explicitly instructed toward creative ways of revenge/damage, future studies should implement more fine-grained analyses that have raters independently score malevolence and effectiveness of generated ideas. Second, on an alternative note, given that the criteria of malevolence and originality showed largely identical associations with Impulsive Non-conformity in the present study, this may inspire a combined score for malevolence/originality that more broadly parses other-rated creativity as an equivalent supplement to the fluency-based main score of malevolent creativity in the MCT.

Conclusion

Altogether, the present study contributes to the understanding of how schizotypy may be related to creative ideation that is intentionally used to damage others. Next to cognitive and affective factors, a more comprehensive understanding of personality aspects in malevolent creativity may help tackle the particularly detrimental combination that is harmful and original behavior. Detailed knowledge of those individual differences could help establish workplace training programs or therapeutic intervention programs focused on impulse control, empathy, or effective emotion regulation techniques (see, e.g., Harris & Reiter-Palmon, Citation2015; Perchtold-Stefan, Fink, Rominger, & Papousek, Citation2021) that help reduce malevolently creative actions in respective individuals and thus help protect organizations and society from highly sophisticated creative damage.

Data availability

The data set generated in this study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the financial support provided by the University of Graz.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abraham, A. (2014). Is there an inverted-U relationship between creativity and psychopathology? Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 750. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00750

- Abu-Akel, A., Webb, M. E., Montpellier, E., De, Bentivegni, S., Von, Luechinger, L., Ishii, A., & Mohr, C. (2020). Autistic and positive schizotypal traits respectively predict better convergent and divergent thinking performance. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 36, 100656. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2020.100656

- Acar, S., Chen, X., & Cayirdag, N. (2018). Schizophrenia and creativity: A meta-analytic review. Schizophrenia Research, 195, 23–31. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2017.08.036

- Acar, S., & Runco, M. A. (2012). Psychoticism and creativity: A meta-analytic review. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 6(4), 341–350. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027497

- Acar, S., & Sen, S. (2013). A multilevel meta-analysis of the relationship between creativity and schizotypy. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 7(3), 214–228. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031975

- Aguilera, M., & Rodríguez-Ferreiro, J. (2021). Differential effects of schizotypy dimensions on creative personality and creative products. Creativity Research Journal, 33(2) Advance Online Publication. 202–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2020.1866895

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Pub.

- Baas, M., Roskes, M., Koch, S., Cheng, Y., & Dreu, C. K. W. D. (2019). Why social threat motivates malevolent creativity. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 45(11), 1590–1602. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167219838551

- Barrantes-Vidal, N., Lewandowski, K. E., & Kwapil, T. R. (2010). Psychopathology, social adjustment and personality correlates of schizotypy clusters in a large nonclinical sample. Schizophrenia Research, 122(13), 219–225. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2010.01.006

- Batey, M., & Furnham, A. (2008). The relationship between measures of creativity and schizotypy. Personality and Individual Differences, 45(8), 816–821. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2008.08.014

- Batey, M., & Furnham, A. (2009). The relationship between creativity, schizotypy and intelligence. Individual Differences Research, 7(4), 272–284.

- Beaussart, M. L., Kaufman, S. B., & Kaufman, J. C. (2012). Creative activity, personality, mental illness, and short-term mating success. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 46(3), 151–167. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/jocb.11

- Burch, G. S. J., Pavelis, C., Hemsley, D. R., & Corr, P. J. (2006). Schizotypy and creativity in visual artists. British Journal of Psychology, 97(2), 177–190. doi:https://doi.org/10.1348/000712605X60030

- Carter, C., Hass, R. W., Charfadi, M., & Dinzeo, T. J. (2019). Probing linear and nonlinear relations among schizotypy, hypomania, cognitive inhibition, and creativity. Creativity Research Journal, 31(1), 83–92. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2019.1580091

- Claridge, G., & Blakey, S. (2009). Schizotypy and affective temperament: Relationships with divergent thinking and creativity styles. Personality and Individual Differences, 46(8), 820–826. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2009.01.015

- Claridge, G., & McDonald, A. (2009). An investigation into the relationships between convergent and divergent thinking, schizotypy, and autistic traits. Personality and Individual Differences, 46(8), 794–799. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2009.01.018

- Claridge, G. (1997). Schizotypy: Implications for illness and health. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/med:psych/9780198523536.001.0001

- Cropley, D. H., Kaufman, J. C., & Cropley, A. J. (2008). Malevolent creativity: A functional model of creativity in terrorism and crime. Creativity Research Journal, 20(2), 105–115. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10400410802059424

- Cropley, D. H., Kaufman, J. C., White, A. E., & Chiera, B. A. (2014). Layperson perceptions of malevolent creativity: The good, the bad, and the ambiguous. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 8(4), 400–412. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037792

- Cropley, D. H. (2010). Malevolent innovation: Opposing the dark side of creativity. In D. H. Cropley, A. J. Cropley, J. C. Kaufman, and M. A. Runco (Eds.), The dark side of creativity(pp. 329–338). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Eysenck, H. J. (1993). Creativity and Personality: Suggestions for a Theory. Psychological Inquiry, 4(3), 147–178. doi:https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli0403_1

- Eysenck, H. J. (1995). Creativity as a product of intelligence and personality. In D. H. Saklofske, and M. Zeidner (Eds.), International handbook of personality and intelligence(pp. 231–247). New York, NY: Plenum Press. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4757-5571-812

- Fink, A., Benedek, M., Unterrainer, H. F., Papousek, I., & Weiss, E. M. (2014a). Creativity and psychopathology: Are there similar mental processes involved in creativity and in psychosis-proneness? Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 1211. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01211

- Fink, A., Perchtold, C., & Rominger, C. (2018). Creativity and cognitive control in the cognitive and affective domains. In R. E. Jung, and O. Vartanian (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of the neuroscience of creativity(pp. 318–332). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316556238.019

- Fink, A., Slamar-Halbedl, M., Unterrainer, H. F., & Weiss, E. M. (2012). Creativity: Genius, madness, or a combination of both? Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 6(1), 11–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024874

- Fink, A., Weber, B., Koschutnig, K., Mathias, B., Reishofer, G., Ebner, F., … Weiss, E. M. (2014b). Creativity and schizotypy from the neuroscience perspective. Cognitive, Affective & Behavioral Neuroscience, 14(1), 378–387. doi:https://doi.org/10.3758/s13415-013-0210-6

- Fisher, J. E., Mohanty, A., Herrington, J. D., Koven, N. S., Miller, G. A., & Heller, W. (2004). Neuropsychological evidence for dimensional schizotypy: Implications for creativity and psychopathology. Journal of Research in Personality, 38(1), 24–31. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2003.09.014

- Fonseca-Pedrero, E., Chan, R. C. K., Debbané, M., Cicero, D., Zhang, L. C., Brenner, C., … Ortuño-Sierra, J. (2018). Comparisons of schizotypal traits across 12 countries: Results from the International Consortium for Schizotypy Research. Schizophrenia Research, 199, 128–134. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2018.03.021

- Furnham, A., & Trickey, G. (2011). Sex differences in the dark side traits. Personality and Individual Differences, 50(4), 517–522. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2010.11.021

- Gino, F., & Wiltermuth, S. S. (2014). Evil genius? How dishonesty can lead to greater creativity. Psychological Science, 25(4), 973–981. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797614520714

- Hanel, P. H. P., & Wolfradt, U. (2016). The ‘dark side’ of personal values: Relations to clinical constructs and their implications. Personality and Individual Differences, 97, 140–145. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.03.045

- Hao, N., Qiao, X., Cheng, R., Lu, K., Tang, M., & Runco, M. A. (2020). Approach motivational orientation enhances malevolent creativity. Acta Psychologica, 203, 102985. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2019.102985

- Hao, N., Tang, M., Yang, J., Wang, Q., & Runco, M. A. (2016). A new tool to measure malevolent creativity: The malevolent creativity behavior scale. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 682. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00682

- Harris, D. J., Reiter-Palmon, R., & Kaufman, J. C. (2013). The effect of emotional intelligence and task type on malevolent creativity. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 7(3), 237–244. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032139

- Harris, D. J., & Reiter-Palmon, R. (2015). Fast and furious: The influence of implicit aggression, premeditation, and provoking situations on malevolent creativity. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 9(1), 54–64. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038499

- Holt, N. J. (2019). The expression of schizotypy in the daily lives of artists. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 13(3), 359–371. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/aca0000176

- Holt, N. J. (2015). Schizotypy. In O. J. Mason, and G. Claridge (Eds.), Advances in mental health research. Schizotypy: New dimensions(pp. 197–214). London, UK: Routledge. doi:https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315858562-13

- James, K., Clark, K., & Cropanzano, R. (1999). Positive and negative creativity in groups, institutions, and organizations: A model and theoretical extension. Creativity Research Journal, 12(3), 211–226. doi:https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326934crj1203_6

- Jauk, E., Benedek, M., & Neubauer, A. C. (2014). The road to creative achievement: A latent variable model of ability and personality predictors. European Journal of Personality, 28(1), 95–105. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/per.1941

- Jonason, P. K., Abboud, R., Tomé, J., Dummett, M., & Hazer, A. (2017). The dark triad traits and individual differences in self-reported and other-rated creativity. Personality and Individual Differences, 117, 150–154. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.06.005

- Kapoor, H., & Khan, A. (2016). The measurement of negative creativity: Metrics and relationships. Creativity Research Journal, 28(4), 407–416. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2016.1229977

- Karwowski, M., & Lebuda, I. (2016). The big five, the huge two, and creative self-beliefs: A meta-analysis. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 10(2), 214–232. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/aca0000035

- LeBoutillier, N., Barry, R., & Westley, D. (2014). The role of Schizotypy in predicting performance on figural and verbal imagery-based measures of creativity. Creativity Research Journal, 26(4), 461–467. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2014.961778

- LeBoutillier, N., Barry, R., & Westley, D. (2016). Creativity and the measurement of subclinical psychopathology in the general population: Schizotypy, psychoticism, and hypomania. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 10(2), 240–247. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/aca0000047

- Lee, S. A., & Dow, G. T. (2011). Malevolent creativity: Does personality influence malicious divergent thinking? Creativity Research Journal, 23(2), 73–82. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2011.571179

- Logan, M. K., Ligon, G. S., & Derrick, D. C. (2020). Measuring Tactical Innovation in Terrorist Attacks. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 54(4), 926–939. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/jocb.420

- Mason, O. J., Claridge, G., & Jackson, M. (1995). New scales for the assessment of schizotypy. Personality and Individual Differences, 18(1), 7–13. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(94)00132-C

- Mason, O. J., & Claridge, G. (2006). The Oxford-liverpool inventory of feelings and experiences (O-LIFE): Further description and extended norms. Schizophrenia Research, 82(23), 203–211. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2005.12.845

- Mason, O. J., Linney, Y., & Claridge, G. (2005). Short scales for measuring schizotypy. Schizophrenia Research, 78(23), 293–296. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2005.06.020

- Mason, O. J. (2015). The assessment of schizotypy and its clinical relevance. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 41(2), 374–385. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbu194

- Michalica, K., & Hunt, H. (2013). Creativity, schizotypicality, and mystical experience: An empirical study. Creativity Research Journal, 25(3), 266–279. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2013.813780

- Mohr, C., & Claridge, G. (2015). Schizotypy—do not worry, it is not all worrisome. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 41(suppl 2), 436–443. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbu185

- Mohr, C., Graves, R. E., Gianotti, L. R., Pizzagalli, D., & Brugger, P. (2001). Loose but normal: A semantic association study. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 30(5), 475–483. doi:https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1010461429079

- Nelson, B., & Rawlings, D. (2010). Relating schizotypy and personality to the phenomenology of creativity. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 36(2), 388–399. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbn098

- Nettle, D. (2006). Schizotypy and mental health amongst poets, visual artists, and mathematicians. Journal of Research in Personality, 40(6), 876–890. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2005.09.004

- O‘Reilly, T., Dunbar, R., & Bentall, R. (2001). Schizotypy and creativity: An evolutionary connection? Personality and Individual Differences, 31(7), 1067–1078. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00204-X

- Papousek, I., Weiss, E. M., Mosbacher, J. A., Reiser, E. M., Schulter, G., & Fink, A. (2014). Affective processing in positive schizotypy: Loose control of social-emotional information. Brain and Cognition, 92, 84–91. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2014.10.008

- Park, H. R. P., Kirk, I. J., & Waldie, K. E. (2015). Neural correlates of creative thinking and schizotypy. Neuropsychologia, 73, 94–107. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2015.05.007

- Perchtold-Stefan, C. M., Fink, A., Rominger, C., & Papousek, I. (2020a). Motivational factors in the typical display of humor and creative potential: The case of malevolent creativity. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1213. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01213

- Perchtold-Stefan, C. M., Fink, A., Rominger, C., & Papousek, I. (2021). Failure to reappraise: Malevolent creativity is linked to revenge ideation and impaired reappraisal inventiveness in the face of stressful, anger-eliciting events. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 1–13. Advance Online Publication. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2021.1918682

- Perchtold‐Stefan, C. M., Fink, A., Rominger, C., & Papousek, I. (2020b). Creative, antagonistic, and angry? Exploring the roots of malevolent creativity with a real‐world idea generation task. The Journal of Creative Behavior. Advance online publication. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/jocb.484

- Plucker, J. A., Beghetto, R. A., & Dow, G. T. (2004). Why isn’t creativity more important to educational psychologists? Potentials, pitfalls, and future directions in creativity research. Educational Psychologist, 39(2), 83–96. doi:https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep3902_1

- Polner, B., Faiola, E., Urquijo, M. F., Meyhöfer, I., Steffens, M., Rónai, L., … Ettinger, U. (2019). The network structure of schizotypy in the general population. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 271(4) Advance online publication. 635–645. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-019-01078-x

- Polner, B., Simor, P., & Kéri, S. (2018). Insomnia and intellect mask the positive link between schizotypal traits and creativity. PeerJ, 6, e5615. doi:https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.5615

- Puryear, J. S., Kettler, T., & Rinn, A. N. (2017). Relationships of personality to differential conceptions of creativity: A systematic review. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 11(1), 59–68. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/aca0000079

- Rawlings, D., & Locarnini, A. (2008). Dimensional schizotypy, autism, and unusual word associations in artists and scientists. Journal of Research in Personality, 42(2), 465–471. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2007.06.005

- Rawlings, D., & Toogood, A. (1997). Using a ‘taboo response’ measure to examine the relationship between divergent thinking and psychoticism. Personality and Individual Differences, 22(1), 61–68. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(96)00177-8

- Reiter-Palmon, R. (2018). Are the outcomes of creativity always positive? Creativity Theories – Research - Applications, 5(2), 177–181. doi:https://doi.org/10.1515/ctra-2018-0016

- Rominger, C., Fink, A., Weiss, E. M., Bosch, J., & Papousek, I. (2017). Allusive thinking (remote associations) and auditory top-down inhibition skills differentially predict creativity and positive schizotypy. Cognitive Neuropsychiatry, 22(2), 108–121. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13546805.2016.1278361

- Rominger, C., Weiss, E. M., Fink, A., Schulter, G., & Papousek, I. (2011). Allusive thinking (cognitive looseness) and the propensity to perceive “meaningful” coincidences. Personality and Individual Differences, 51(8), 1002–1006. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.08.012

- Ross, S. R., Lutz, C. J., & Bailley, S. E. (2002). Positive and negative symptoms of schizotypy and the Five-factor model: A domain and facet level analysis. Journal of Personality Assessment, 79(1), 53–72. doi:https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327752JPA7901_04

- Runco, M. A., & Jaeger, G. J. (2012). The standard definition of creativity. Creativity Research Journal, 24(1), 92–96. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2012.650092

- Runco, M. A. (2010). Creativity has no dark side. In D. H. Cropley (Ed.), The dark side of creativity(pp. 15–32). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511761225.002

- Sacks, S. A., Weisman de Mamani, A. G., & Garcia, C. P. (2012). Associations between cognitive biases and domains of schizotypy in a non-clinical sample. Psychiatry Research, 196(1), 115–122. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2011.09.019

- Schuldberg, D. (1990). Schizotypal and hypomanic traits, creativity, and psychological health. Creativity Research Journal, 3(3), 218–230. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419009534354

- Schwartz, S. H., & Bardi, A. (2001). Value hierarchies across cultures. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 32(3), 268–290. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022101032003002

- Stanciu, M. M., & Papasteri, C. (2018). Intelligence, personality and schizotypy as predictors of insight. Personality and Individual Differences, 134, 43–48. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.05.043

- Sun, W., Chou, C. P., Stacy, A. W., Ma, H., Unger, J., & Gallaher, P. (2007). SAS and SPSS macros to calculate standardized Cronbach’s alpha using the upper bound of the phi coefficient for dichotomous items. Behavior Research Methods, 39(1), 71–81. doi:https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03192845

- Tabak, N. T., & Weisman de Mamani, A. G. (2013). Latent profile analysis of healthy schizotypy within the extended psychosis phenotype. Psychiatry Research, 210(3), 1008–1013. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2013.08.006

- van Os, J., Linscott, R. J., Myin-Germeys, I., Delespaul, P., & Krabbendam, L. (2009). A systematic review and meta-analysis of the psychosis continuum: Evidence for a psychosis proneness-persistence-impairment model of psychotic disorder. Psychological Medicine, 39(2), 179–195. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291708003814

- Xu, X., Zhao, J., Xia, M., & Pang, W. (2021). I can, but I won’t: Authentic people generate more malevolently creative ideas, but are less likely to implement them in daily life. Personality and Individual Differences, 170, 110431. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110431