ABSTRACT

The long-term use of transfer support robots in nursing facilities is an important option for improving the efficiency of care work. The “Resyone” transfer support robot is a combination of an electric care bed and a wheelchair, and the wheelchair half of the bed can be detached at the touch of a button. The purpose of this study was to investigate how the long-term use of Resyone would improve the performance of transfer assists, such as reducing the need for multiple caregivers. One Resyone was installed in a nursing facility in Japan and 17 caregivers used it for more than 11 months. The time and number of caregivers required for each transfer assist were surveyed for three 1-week periods: 1 week before (Phase 1) and at 3 weeks (Phase 2) and 11 months (Phase 3) after the introduction of Resyone. In Phase 1, approximately 60% of all transfer assists were performed by two caregivers, but in Phase 2, this was reduced to approximately 20%, and finally, in Phase 3, all transfer assists were performed by a single caregiver. These results suggested that the long-term use of Resyone was associated with improved work efficiency in transfer assistance in a nursing facility.

Introduction

As the world’s older adult population continues to grow rapidly and the working-age population continues to decline, the shortage of caregivers in nursing facilities has become an urgent issue not only in Japan but also globally (Faucounau et al., Citation2009; Kondo, Citation2019). An important option for reducing the physical and mental burden on caregivers and improving the quality of care is the utilization of robotic care equipment (Kondo, Citation2019; Yoshimi et al., Citation2021a, Citation2021b; Kato et al., Citation2021; Robotic Care Devices Portal site). In particular, caregivers face the problem of an increased burden on the lower back caused by daily repetitive transfer tasks and the associated risk of back pain (Dawson et al., Citation2007; Fujimura et al., Citation1995; Pompeii et al., Citation2009). In addition, depending on the degree of disability or body size of care recipients, multiple caregivers are required to provide transfer assistance (OSHA, Guidelines for Nursing Homes, Ergonomics for the Prevention of Musculoskeletal Disorders), which may reduce their work efficiency.

To resolve the aforementioned issues, a previous study suggested that a robotic lifting device, “Hug” (Fuji Corporation, Aichi, Japan), which inserts a soft robotic arm under each armpit of a care recipient, could assist in transfer care tasks and successfully reduce the physical burden on caregivers (Yoshimi et al., Citation2021a). Similarly, another study suggested that a robotic-assisted transfer device could support stand-pivot transfers and fully dependent transfers, where the care recipient is in a sling and their weight is supported fully by the robot (Grindle et al., Citation2015). Although these assistive robots are effective in transfer care tasks, it may be difficult for caregivers to provide the series of care tasks associated with transfers, such as “getting up from a bed,” “sitting on the bed edge,” and “transferring from the bed to a wheelchair,” for example, in a care recipient who requires a high degree of assistance.

“Resyone Plus” (Resyone) (Panasonic AGE-FREE Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan) is a type of transfer support robot consisting of a combination of an electric care bed and a wheelchair, with half of the bed separating at the touch of a button to function as a wheelchair (Kume et al., Citation2015, Citation2019; Robotic Care Devices Portal site; ). Resyone is novel in that it can support transfer care tasks without physical assistances from a caregiver such as for getting up from a bed and sitting on a bed edge before transferring a care recipient. Specifically, although caregivers are needed initially to move a care recipient to one side of Resyone, which functions as a wheelchair (), the other steps in the procedure for separating the wheelchair side of the Resyone bed (), raising the care recipient to a sitting position (), and transforming Resyone into a wheelchair () can be carried out at the touch of a button. Thus, it may be possible that Resyone can be used by a single caregiver for a care recipient who would otherwise require a high level of nursing care administered by multiple caregivers. If this could be achieved, the use of robotic care equipment would lead to an improvement of work efficiency; however, this has not been examined in nursing facilities.

Figure 1. Images of the transfer support robot “Resyone Plus” (Resyone) developed by Panasonic AGE-FREE Co., Ltd. (Osaka, Japan) (a). Resyone is a type of transfer support robot that is a combination of an electric care bed and a wheelchair, with half of the bed separating at the touch of a button to function as a wheelchair as shown in panels (b–d). The images used in this figure were kindly provided by Panasonic AGE-FREE Co., Ltd. with permission for use in publication. The person using this robot and the person on the bed are both models and not participants in this study.

An essential element for the sustainable use of this type of robot is the improved proficiency of caregivers as they gain experience with the device. The same applies to Resyone, and even though Resyone can be operated using a simple process, it is assumed that a certain amount of time, for example, a period of more than 1 month, may be needed to become familiar with the operation and handling of Resyone. This suggests the need to investigate the long-term effects of introducing this type of robot, including the process of learning to use it. Another issue with transfer assist robots in nursing facilities in Japan is that their introduction does not ensure they are used, as the percentage of facilities that have introduced them, but do not use them frequently, is the same as the percentage of facilities that have introduced them and use them frequently (Survey of Elderly Care by the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan), which may also be related to the level of proficiency in using these devices.

Therefore, in this study, we introduced a Resyone for a care recipient who required a high level of care at a nursing facility in Japan that had never used a transfer assist robot before. The aim of the present study was to examine the long-term effects on working efficiency such as reducing the need for multiple caregivers during transfer assists. To investigate them, the timing, duration, and number of 17 caregivers required for each transfer assist were surveyed for three 1-week periods: 1 week before (Phase 1) and at 3 weeks (Phase 2) and 11 months (Phase 3) after the introduction of Resyone.

Method

We selected a special nursing facility for the elderly that had not yet used Resyone (selected from facility list in a report: Survey of elderly care by the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan, Citation2017). Individuals requiring level 3 long-term care generally need partial or full assistance when standing up, sitting up, standing on one leg, walking, body washing, money management, eating, nail clipping, putting on and taking off pants, moving around, decision making involved in daily life, facial washing, hair dressing, mouth cleaning, urination, defecation, and transfer from/to a bed (Imahashi et al., Citation2007).

A single Resyone was used for one care recipient (male, age class: 80–84 years, weight class: 50–60 kg, height class: 170–180 cm). His designation for the determination of daily life independence (bedridden level) of the elderly with disability was Grade C (Supplementary Table 1), and that for daily life independence level of the elderly with dementia was Grade IIIa (Supplementary Table 2). In an interview with the caregivers prior to the survey, it was confirmed that the care recipient was sometimes assisted by two or three caregivers, depending on the care recipient’s condition and the caregivers’ proficiency, for transfers from a bed to a wheelchair.

A total of 17 full-time caregivers (male, 6; female, 11; age, 46 ± 14 years; work experience, 9.6 ± 6.8 years) who were involved in the use of Resyone participated in this study. The caregivers consisted of 16 certified care workers with a national qualification in the area of nursing care and one care helper. Of the 16 certified care workers, four were also licensed care helpers and one was a licensed practical nurse. The duties of care workers and care helpers are similar, but certified care workers are in charge of a unit and provide care instructions to the other caregivers. The average height and weight of the caregivers in the unit in each phase were calculated for each sex (). The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics and Conflicts of Interest Committee of the National Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology (acceptance no. 1275) and all participants provided written informed consent.

Table 1. The average height and weight of the caregivers in the unit in each phase. Height was shown by centimeter and weight by kilograms.

The 1-week surveys were conducted in three 3 phases: before (Phase 1) and at 3 weeks (Phase 2) and 11 months (Phase 3) after the introduction of Resyone. On the first day of its introduction, a briefing session on how to use Resyone was held by the developer and manufacturer for the caregivers who would use the device. After the introduction of Resyone, it replaces the care recipient’s conventional bed, which means that Resyone will continue to be used at least as their bed all day long. The evaluation protocol involved a questionnaire, a care record survey of transfers and place of stay, analysis of the caregivers’ recorded voices, and analysis of physical burden via heart rate measurement using a wearable device (Polar OH1 Heart Rate Sensor; Polar Electro Oy, Vantaa, Finland).

During a 1-week period, a questionnaire was administered to 12 caregivers in Phase 2 and 13 caregivers in Phase 3. The questionnaire consisted of the following questions: 1) Was physical burden reduced by using Resyone? and 2) Could effective assistance be provided by using Resyone? The questions were answered using one of the following 4 options: “Agree,” “Somewhat agree,” “Somewhat disagree,” and “Disagree.” The questionnaire also asked about the advantages and disadvantages of operating Resyone in a descriptive format. Based on our past experience with surveys on nursing care robots, when “neutral” was included in a questionnaire asking about the advantages and disadvantages of these robotics in Japanese nursing facilities, the general tendency was that the overwhelming majority of respondents answered “neutral.” The purpose of this survey was to clarify the positive or negative effects of the introduction of Resyone by excluding “neutral” from the survey.

Second, using a care record survey of transfers, the 17 caregivers were asked to fill in the following information when transferring the care recipient using Resyone during three 1-week periods of Phases 1–3: 1) time of transfer, 2) whether the care recipient was assisted by one or multiple caregivers, and 3) destination after transfer. Bathing assistance is sometimes scheduled irregularly on a weekly basis; therefore, a 1-week survey period was used to investigate the exhaustive contents of care work for the care recipient. In Phases 2 and 3, a care record survey of transfers was used to verify whether half of Resyone was detached and used as a wheelchair (i.e., whether the care recipient was transferred or moved).

Third, we asked three caregivers who were mainly involved in providing care to the care recipient to wear a heart rate sensor and carry a voice recorder for 1 day during their work shift in Phases 1 and 2, and extracted the changes in heart rate during transfers as reported previously (Yoshimi et al., Citation2021a) by classifying them into three transfer scenarios: transfer assist by a single caregiver without Resyone, transfer assist with multiple caregivers without Resyone, and transfer assist by a single caregiver with Resyone. The exact timing of the start and end of each transfer was identified based on the instructions for the transfer from the caregiver to the care recipient recorded on the voice recorder. The changes in heart rate in each transfer scenario were plotted as boxplots and compared using an unpaired t-test. Statistical analysis was performed with MATLAB statistical tool box (MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA, USA).

Lastly, after all the surveys had been completed, an interview was held with five caregivers who had been involved in the operation of Resyone, as well as the director and deputy director of the nursing facility. In the interview, they gave their opinions about the advantages and disadvantages of operating Resyone, the changes in proficiency associated with the long-term use of Resyone, and the information needed for its sustained operation over 11 months. Each opinion or comment was extracted and listed.

Results

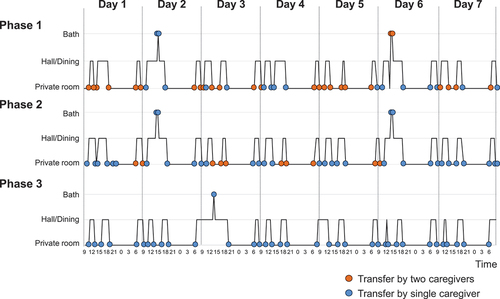

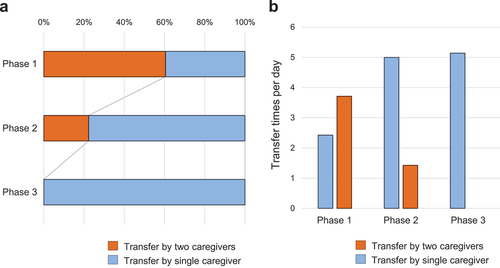

Firstly, using the care record survey during the 1-week evaluation periods in Phases 1–3, the time of transfer, staffing levels (either single- or multiple-caregiver assistance), and the destination of the transfer were compiled. As a result, we confirmed all multiple-caregiver assists were provided by two caregivers in this evaluation period. Next, as a result of identifying the pattern of daily life based on the transfer destination of the care recipient, we confirmed that he visited the common area (hall) and dining room several times a day and bathed once or twice a week in Phases 1–3 (). In Phase 1 before the introduction of Resyone, approximately 60% of all transfer assists were provided by two caregivers (). In contrast, in Phases 2 and 3 after the introduction of Resyone, all transfer assists were performed using Resyone (i.e., by detaching one side of Resyone and transforming it into a wheelchair). Moreover, in Phase 2, the number of transfers assisted by two caregivers was reduced to 22% of all transfers, with the remaining 78% assisted by a single caregiver. In Phase 3, two-caregiver assistance was no longer provided and all transfers were carried out by a single caregiver (). These results showed that over the 11-month period after the introduction of Resyone, the number of two-caregiver assists decreased gradually, and eventually, all transfers were carried out by a single caregiver in Phase 3 ().

Figure 2. The life pattern of the care recipient, and the staffing levels required for each transfer of the care recipient during three 1-week periods: 1 week before (Phase 1) and at 3 weeks (Phase 2) and 11 months (Phase 3) after the introduction of Resyone. Orange and blue circles represent transfers by two caregivers and a single caregiver, respectively. From the care record survey, we confirmed that all transfer assists were performed using Resyone in Phases 2 and 3 (i.e., by detaching one side of Resyone and transforming it into a wheelchair).

Figure 3. Ratio of the number of staff required for assistance (a) and the number of transfers at each staffing level (b) over each phase before (Phase 1) and at 3 weeks (Phase 2) and 11 months (Phase 3) after the introduction of Resyone among 17 caregivers. Blue and Orange circles represent transfers by a single caregiver and two caregivers, respectively.

Secondly, by using a wearable heart rate sensor, the physical burden of normal transfers (single- or two-caregiver assistance) before and after the introduction of Resyone was examined (). The results confirmed a trend toward reduced heart rate changes during transfer assists with Resyone compared to single- or two-caregiver assistance without Resyone (p < .01, assistance with Resyone vs. single-person assistance without Resyone; p = .06, assistance with Resyone vs. two-person assistance without Resyone, unpaired t-test).

Figure 4. Heart rate difference before and after transfer assistance by a single caregiver without Resyone (left, n = 5), by two caregivers without Resyone (middle, n = 3), and with Resyone (right, n = 4) measured using a wearable heart rate monitor. All data plotted were calculated from transfers between a bed and wheelchair (i.e., “without Resyone” was between a conventional bed and wheelchair; “with Resyone” was between the Resyone bed and wheelchair).

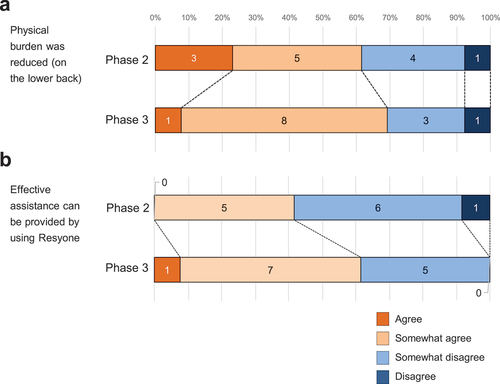

Thirdly, the survey responses from caregivers regarding the effects of using Resyone on reducing their work burden and the provision of effective care were compiled. The results showed that in Phase 2, 61% (23% Agree, 38% Somewhat agree) of responses were positive to the question “Was physical burden reduced by using Resyone?” while in Phase 3, 69.3% (8% Agree, 61.3% Somewhat agree) of responses were positive (). For the question “Could effective assistance be provided by using Resyone?” only 38% of responses were positive in Phase 2 (0% Agree, 38% Somewhat agree), but this increased to 62% (8% Agree, 54% Somewhat agree) in Phase 3 ().

Figure 5. Results of the questionnaire survey conducted after the introduction of Resyone in Phases 2 and 3. The questionnaire consisted of the following questions: 1) Was physical burden reduced by using Resyone? (a) and 2) Could effective assistance be provided by using Resyone? (b). The questions were answered using one of the following four options: “Agree,” “Somewhat agree,” “Somewhat disagree,” and “Disagree.” A total of 12 caregivers responded in Phase 2 and 13 caregivers responded in Phase 3. For each question, the total number of caregivers is shown in the bar chart.

Finally, from statements made in questionnaires from caregivers involved in the use of Resyone and from post-survey interviews with caregivers and the director and deputy director of the nursing facility, we extracted opinions on the advantages and disadvantages of Resyone and ideas for its sustainable use. As a result, the following representative advantages were identified: 1) even physically smaller caregivers could transfer the care recipient on their own; 2) the ability of a single caregiver to perform transfer assists allowed another caregiver, who was previously required for transfers, to engage in other tasks; 3) care for the recipient became more flexible, as there was no longer a need for caregivers to coordinate operations (e.g., assistance could be given when the resident was ready to get up) and additional care operations could be provided to expand the recipient’s range of activities; 4) caregivers became less fearful when assisting the care recipient with transfers (i.e., they now felt more comfortable assisting with transfers); 5) by being able to operate Resyone individually, a caregiver could provide assistance when the care recipient was ready to get up and not at a set time; and 6) the physical burden of performing transfers was reduced.

Conversely, the following representative disadvantages were identified: 1) the current performance of the Resyone wheelchair does not allow it to move over steps of 5 mm or higher, which limited the range of movement of the care recipient within the nursing facility; 2) the weight of the Resyone wheelchair is approximately 50 kg, which required a certain level of skill for the caregivers to push it around; 3) similar to 2), the weight of the Resyone wheelchair required a certain amount of skill by the caregivers to fine-tune its movement in a limited space, such as within the care recipient’s room; 4) the Resyone wheelchair was more prone to slipping forward in the seated position than a standard wheelchair and, therefore, required more attention to be paid to the care recipient’s posture when moving; and 5) when using Resyone as a wheelchair, the care recipient had to be moved to one side of the bed, which was a physical burden for caregivers.

In addition, the following points were raised when asked about the measures taken to ensure the effective use of Resyone: 1) to facilitate education on how to use the device, a caregiver who was not yet familiar with its operation observed another experienced caregiver using it; and 2) when the device was used by a caregiver who was not yet familiar with its handling in the early stage of its introduction, an experienced caregiver had to assist with its operation.

Discussion

In this study, Resyone, a transfer support robot, was introduced to a nursing facility in Japan for 11 months, and changes in the proficiency levels (i.e., number of caregivers required) and physical burden on caregivers, mainly for transfer assists, were examined. The results showed that after the introduction of Resyone, the number of transfers assisted by two caregivers decreased gradually over time, and after 11 months, it fell to zero, confirming that all transfers could be carried out by a single caregiver (). Furthermore, through a quantitative assessment using heart rate sensors () and a qualitative assessment based on surveys conducted among the caregivers (), we confirmed that the use of Resyone tended to reduce the physical burden associated with transfer assists. These results suggest that the introduction of Resyone can reduce the physical burden of transfer assists and improve work efficiency, which will be useful for the sustainable use of robotic care equipment such as transfer support equipment in the future.

In recent years, despite the chronic shortage of caregivers, many nursing facilities worldwide are required to carry out a wide variety of tasks with limited manpower, e.g., direct care for residents such as assistance with transfers, toileting, bathing, and eating as well as indirect care and other tasks such as documentation, communication, and medication administration (Ellis et al., Citation2012; Kato et al., Citation2021; Munyisia et al., Citation2011; Qian et al., Citation2016, Citation2014, Citation2012; Simmons & Schnelle, Citation2006). In particular, it has been pointed out that the repetitive daily tasks associated with repositioning and transferring residents around a bed can increase the physical burden on caregivers and the associated risk of back pain (Dawson et al., Citation2007; Fujimura et al., Citation1995; Pompeii et al., Citation2009). Therefore, in order to ensure safety during transfer assists, it is recommended that more than one caregiver provides assistance, depending on the care recipient’s physique and weight or caregivers’ proficiency. The U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration, for example, has published guidelines for nursing facilities on the combined use of welfare equipment with methods of care appropriate to the physique, weight, and condition of a care recipient, including recommendations for repositioning in a bed by at least three caregivers as well as the use of a friction-reducing device when assisting a resident weighing more than ~90 kg (for patients weighing <90 kg, transfer by two or three caregivers is recommended, in Guidelines for Nursing Homes, OSHA, Citation2009). However, in order to provide multiple-caregiver assistance, it is necessary to coordinate the actions of caregivers in advance. Furthermore, changing the work operations of caregivers who have already been assigned a large number of tasks could lead to a decrease in efficiency and quality of care such as less time spent with care recipients (Kayser-Jones et al., Citation2003). In this sense, this study is considered to be significant because, for the first time, it has shown that the introduction of a transfer support robot can reduce the staffing levels required for transfers. In fact, in the post-survey interviews, we confirmed that the ability of a single caregiver to assist with transfers meant that another caregiver who was previously needed could be engaged in other tasks and care could be more flexible as there was no longer a need to coordinate operations between caregivers. These effects may be broadly applicable to nursing facilities not only in Japan but also worldwide, since reducing the physical burden on caregivers and improving work efficiency are recognized as an urgent global issue. In comparing Resyone with other welfare equipment, low-tech equipment used for lateral transfers such as transfer boards and slides, for example, can be considered. These forms of low-tech equipment are relatively inexpensive, but they require more caregiver effort to use and do not relieve the caregiver of physical loads that can cause back, shoulder, neck, leg, and wrist injuries (Retsas & Pinikahana, Citation2000; Sivakanthan et al., Citation2019). In addition, mechanical lifts for transfers reduce the burden on caregivers; however, during transfers, the center of gravity when the care recipient is in transit is high, which can lead to instability and falls. In this sense, Resyone has the advantage that it can be used as a wheelchair without the need for transfer assistance, leading to easier and safer assistance. In fact, post-survey interviews with the caregivers revealed that they were less fearful when assisting with transfers especially for a care recipient who required a high level of transfer assistance. The American Nurses Association supports the introduction of actions and policies that result in the elimination of manual patient handling, since with the development of assistive equipment, such as transfer devices and lifts, the risk of musculoskeletal injury can be significantly reduced (American Nurses Association position statement, Citation2004). In addition, appropriate use of these assistive devices through the implementation of safe patient handling and mobilization programs has been highly effective in reducing injuries in care recipients (Ann Adamczyk, Citation2018; Teeple et al., Citation2017; Wyatt et al., Citation2020). As these reports have shown, our study supports the idea that the effective use of Resyone has the potential to provide safer and more reliable care, regardless of the skills of caregivers.

It is also noteworthy that the use of Resyone does not completely relieve the physical burden on caregivers, since part of the function of Resyone involves the provision of physical assistance (e.g., lateral transfer to one side of the Resyone wheelchair). Even if this physical assistance by caregivers is included, the finding that heart rate differences were lower with Resyone than without Resyone during transfer assistance () was an apparently positive result, even though the sample size was limited. According to the questionnaire survey, approximately 70% of the caregivers agreed that the use of Resyone reduced their physical burden, while the remaining 30% disagreed (). The reasons for the negative comments were obscure, but one of the factors may be related to the opinions from the post-survey interview that pushing and moving the Resyone wheelchair occasionally required a lot of effort due to its weight of approximately 50 kg. In a future study, the number of caregivers should be increased, and heart rates should be measured not only in bed-Resyone transfer situations, but also other transfer situations and when moving with Resyone’s wheelchair. As indicated by the post-survey interview, another limiting factor of the Resyone wheelchair was that it could not go over steps higher than 5 mm, which limited its range of movement within the nursing facility. In order to promote the efficient introduction of Resyone, it would be necessary to check in advance the living range of the targeted care recipient and environmental aspects such as steps and floor surfaces in the nursing facility.

One of the interesting findings of this study was that the number of two-caregiver assists reduced gradually over time. Naturally, even though most of Resyone’s operations are performed using buttons, it takes a certain amount of time to become familiar with the procedure. The post-survey interviews also revealed that it requires some time to get used to maneuvering the Resyone wheelchair due to the small size of its tires. Therefore, the results suggest that a certain period of practice is required before the effects of its introduction become apparent. The increase in positive opinions in the questionnaire between Phases 2 and 3, such as more effective care or reduced physical burden by the use of Resyone, may be related to such a proficiency effect (). Furthermore, the interviews revealed that the following measures were taken to increase the level of proficiency: when the device was used by a caregiver who was not yet familiar with its handling in the early stage of its introduction, an experienced caregiver should be present, and to facilitate education on how to use Resyone, a caregiver who was not yet familiar with it observed another experienced caregiver using it. In the future, it will be necessary to issue guidelines for new types of transfer support robots such as Resyone that include information on safe patient handling and mobilization, environmental adjustments, and educational systems for caregivers to enhance the proficiency of handling these devices.

Other limitations of this study are as follows. First, we did not assess the effectiveness of Resyone from the point of view of the care recipient. According to a previous study using the “Hug” transfer support robot, its long-term use not only reduced the physical burden on caregivers but also increased the frequency of verbal communication between caregivers and care recipients (Yoshimi et al., Citation2021a). In other words, the results suggest that the reduced physical burden on caregivers may have a positive effect on care recipients in the form of increased communication. The same may apply to Resyone, where the ability of caregivers to perform transfers more flexibly and the reduction of the physical burden of transfers may have a positive effect on the care recipient. For example, the introduction of Resyone may lead to more opportunities for care recipients to be transferred, who can then spend more time outside their private room and communicate with other care recipients and caregivers. Secondly, there is a need for more examples of the introduction of Resyone. A large-scale study would clarify the effects of its use on caregivers and care recipients in different demographic groups. Lastly, although this study was limited to work efficiency in transfer assistance, further research is needed to determine whether Resyone can contribute to overall work efficiency in a nursing facility. In order to investigate these details, we need to identify new care tasks that can be assigned due to the reduction in the number of transfers requiring multiple caregivers.

Overall, despite these limitations, we believe that our findings provide a basis for the effective introduction and sustainable use of robotic care equipment such as Resyone to improve operational work efficiency and reduce physical burden on caregivers in nursing facilities.

Conclusion

In this study, we demonstrated that the introduction of a transfer support robot, Resyone, led to a gradual decrease in the number of two-caregiver transfers and an increase in the number of single-caregiver transfers over an 11-month period in a nursing facility in Japan. Moreover, the use of Resyone tended to reduce the physical burden associated with transfer assists. These results suggest that the introduction of Resyone can reduce the physical burden on caregivers and improve the efficiency of transfer assists, which will be useful for the sustainable use of robotic care equipment such as transfer support equipment in the future.

Author contributions

I.K. conceived the study. All authors designed the study. K.K., Y.T., K.A., K.S., and N.I. performed the study and data collection. K.K. and T.Y. analyzed the data, prepared the figure, and wrote the paper. All authors revised the manuscript.

Clinical trial registration

UMIN Clinical Trials Registry no. UMIN000039204. Trial registration date: January 21, 2020. Interventional study. Parallel, non-randomized, single blinded.

Consent to publish statement/form

All of the authors have contributed to this study and are in agreement with the content of the manuscript.

Declarations and ethics statements

Study protocols have been reviewed and approved by the Ethics and Conflicts of Interest Committee of the National Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology (acceptance no. 1275) and all participants provided written informed consent.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (17.8 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (26.1 KB)Acknowledgments

We thank the staff of “Ai-ko Home Obu-en,” a special nursing home for the elderly, for their cooperation. We also thank N. Hashimoto, A. Sugiyama, M. Chiso, and H. Nakamura for their technical support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed during the current study are not publicly available given that the research team has not completed its analysis, but are available from the corresponding author on request.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website.

Additional information

Funding

References

- American Nurses Association position statement on elimination of manual patient handling to prevent work-related musculoskeletal disorders. (2004). The Prairie Rose, 73(4). 18–19. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15586553/

- Ann Adamczyk, M. (2018). Reducing intensive care unit staff musculoskeletal injuries with implementation of a safe patient handling and mobility program. Critical Care Nursing Quarterly, 41(3), 264–271. https://doi.org/10.1097/CNQ.0000000000000205

- Dawson, A. P., McLennan, S. N., Schiller, S. D., Jull, G. A., Hodges, P. W., & Stewart, S. (2007). Interventions to prevent back pain and back injury in nurses: A systematic review. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 64(19), 642–650. https://doi.org/10.1136/oem.2006.030643

- Ellis, W., Kaasalainen, S., Baxter, P., & Ploeg, J. (2012). Medication management for nurses working in longterm care. The Canadian Journal of Nursing Research, 44(3), 128–149. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23156195/

- Faucounau, V., Wu, Y. H., Boulay, M., Maestrutti, M., & Rigaud, A. S. (2009). Caregivers’ requirements for in-home robotic agent for supporting community-living elderly subjects with cognitive impairment. Technology and Health Care, 17(1), 33–40. https://doi.org/10.3233/THC-2009-0537

- Fujimura, T., Yasuda, N., & Ohara, H. (1995). Work-related factors of low back pain among nursing aides in nursing homes for the elderly. Sangyo Eiseigaku Zasshi, 37(2), 89–98. https://doi.org/10.1539/sangyoeisei.37.2_89

- Grindle, G. G., Wang, H., Jeannis, H., Teodorski, E., & Cooper, R. A. (2015). Design and user evaluation of a wheelchair mounted robotic assisted transfer device. BioMed Research International, 2015, 198476. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/198476

- Imahashi, K., Kawagoe, M., Eto, F., & Haga, N. (2007). Clinical status and dependency of the elderly requiring long-term care in Japan. The Tohoku Journal of Experimental Medicine, 212(3), 229–238. https://doi.org/10.1620/tjem.212.229

- Kato, K., Yoshimi, T., Tsuchimoto, S., Mizuguchi, N., Aimoto, K., Itoh, N., & Kondo, I. (2021). Identification of care tasks for the use of wearable transfer support robots - an observational study at nursing facilities using robots on a daily basis. BMC Health Services Research, 21(1), 652. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06639-2

- Kayser-Jones, J., Schell, E., Lyons, W., Kris, A. E., Chan, J., & Beard, R. L. (2003). Factors that influence end-of-life care in nursing homes: The physical environment, inadequate staffing, and lack of supervision. The Gerontologist, 43(Suppl. 2), 76–84. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/43.suppl_2.76

- Kondo, I. (2019). Frailty in an aging society and the applications of robots. Japanese Journal of Comprehensive Rehabilitation Science, 10, 47–49. https://doi.org/10.11336/jjcrs.10.47

- Kume, Y., Tsukada, S., & Kawakami, H. (2015). Design and evaluation of rise assisting bed “Resyone” based on ISO 13482. Journal of the Robotics Society of Japan, 33(10), 781–788. (in Japanese). https://doi.org/10.7210/jrsj.33.781.

- Kume, Y., Tsukada, S., & Kawakami, H. (2019). Development of safety technology for rise assisting robot “Resyone Plus. Dynamics & Control, Robotics & Mechatronics, 85(869), 18–00344. https://doi.org/10.1299/transjsme.18-00344 (in Japanese).

- Munyisia, E. N., Yu, P., & Hailey, D. (2011). How nursing staff spend their time on activities in a nursing home: An observational study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 67(9), 1908–1917. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05633.x

- Occupational Safety & Health Administration, OSHA. (2003). Guidelines for nursing homes: Ergonomics for the prevention of Musculoskeletal disorders. OSHA Publication 3182. (revised March 2009). Retrieved December, 2021, from https://www.osha.gov/sites/default/files/publications/final_nh_guidelines.pdf

- Pompeii, L. A., Lipscomb, H. J., Schoenfisch, A. L., & Dement, J. M. (2009). Musculoskeletal injuries resulting from patient handling tasks among hospital workers. American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 52(7), 571–578. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajim.20704

- Qian, S., Yu, P., & Hailey, D. (2016). Nursing staff work patterns in a residential aged care home: A timemotion study. Australian Health Review, 40(5), 544–554. https://doi.org/10.1071/AH15126

- Qian, S., Yu, P., Hailey, D. M., Zhang, Z., Davy, P. J., & Nelson, M. I. (2014). Time spent on daytime direct care activities by personal carers in two Australian residential aged care facilities: A time–motion study. Australian Health Review, 38(2), 230–237. https://doi.org/10.1071/AH13161

- Qian, S., Yu, P., Zhang, Z., Hailey, D. M., Davy, P. J., & Nelson, M. I. (2012). The work pattern of personal care workers in two Australian nursing homes: A time–motion study. BMC Health Services Research, 12(1), 305. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-12-305

- Retsas, A., & Pinikahana, J. (2000). Manual handling activities and injuries among nurses: An Australian hospital study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 31(4), 875–883. Robotic Care Devices Portal site - Robotic Devices for Nursing Care Project. Retrieved December, 2020, from. http://robotcare.jp/en/development/index.php

- Simmons, S. F., & Schnelle, J. F. (2006). Feeding assistance needs of long-stay nursing home residents and staff time to provide care. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 54(6), 919–924. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00812.x

- Sivakanthan, S., Blaauw, E., Greenhalgh, M., Koontz, A. M., Vegter, R., & Cooper, R. A. (2019). Person transfer assist systems: A literature review. Disability and Rehabilitation. Assistive Technology, 16(3), 270–279. https://doi.org/10.1080/17483107.2019.1673833

- Survey of elderly care by the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan. (2017). Report on research project on possibilities of utilization of IoT etc. Geriatric Health Care Facilities, Retrieved October, 2020, from http://www.roken.or.jp/wp/wpcontent/uploads/2018/04/H29_Iot_katsuyo_report.pdf

- Teeple, E., Collins, J. E., Shrestha, S., Dennerlein, J. T., Losina, E., & Katz, J. N. (2017). Outcomes of safe patient handling and mobilization programs: A meta-analysis. Work, 58(2), 173–184. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-172608

- Wyatt, S., Meacci, K., & Arnold, M. (2020). Integrating safe patient handling and early mobility: Combining quality initiatives. Journal of Nursing Care Quality, 35(2), 130–134. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCQ.0000000000000425

- Yoshimi, T., Kato, K., Aimoto, K., Sato, K., Itoh, N., & Kondo, I. (2021b). Utilization of transfer support equipment for meeting with family members in a nursing home during the COVID-19 pandemic: A case report. Geriatrics & Gerontology International, 21(8), 741–742. https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.14198

- Yoshimi, T., Kato, K., Tsuchimoto, S., Mizuguchi, N., & Kondo, I. (2021a). Increase of verbal communication by long-term use of transfer-support robots in nursing facilities. Geriatrics & Gerontology International, 21(2), 276–277. https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.14113