ABSTRACT

A three-level training intervention was developed using the Quality Implementation Framework (QIF) to increase technology transfer of rehabilitation technologies to market. Thirty-two teams completed Level 1, 14 completed Level 2, and 6 completed Level 3. The validated Technology Transfer Readiness Assessment Tool (TTRAT) measured teams’ technology transfer progress and the effectiveness of the training program. Teams that completed at least two training levels demonstrated increased technology transfer readiness. Additional team outcomes include receiving other federal awards, FDA designations, and generating sales. Future work includes measuring teams’ progress relative to participant demographics and developing additional training content based on gaps in technology transfer readiness. The multi-level training initiative shows it is a promising foundation for training researchers and aspiring entrepreneurs on technology transfer and subsequent technology transfer outcomes.

Introduction

Assistive technologies (AT) are a key facilitator to improved health and function, independence, and community participation for nearly 2.5 billion people worldwide with disabilities (Assistive, Citation2019; Global, Citation2022). Accessibility to quality ATs worldwide can be variable with effective technology transfer (TT) or the process to ensure products reach the intended beneficiaries, serving as a key facilitator or barrier (Leahy & Lane, Citation2010). Challenges to effective assistive technology technology transfer (ATTT) include a need for more resources, incentives, and collaboration. Facilitators, including access to training, technical assistance, funding, and interdisciplinary collaboration, may accelerate ATTT (Higgins, Citation2022). The Initiative to Mobilize Partnerships for Assistive Technology Transfer (IMPACT) Center was funded by the National Institute for Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR) in 2018 with a mission to offer technical assistance to grantees to support technology transfer of their products. One of the IMPACT Center’s key objectives was to develop a multi-level ATTT training program to assist with overcoming these challenges.

A gap in training specific to ATTT

A desk review of existing TT training revealed several resources but no specific training interventions for assistive and rehabilitation technologies, with minimal agreement on one robust emergent model for disability, AT, and rehabilitation researchers to follow. This may be critical as training was identified as a key facilitator to ATTT (Higgins, Citation2022).

I-Corps and Lean LaunchPad

There is no shortage of training models on academic TT, with the National Science Foundation (NSF) I-Corps program taking the lead. It has trained 1,900 teams from 1,280 academic and other organizations on the Lean LaunchPad customer discovery methodology, and more than 1,036 have launched startups (Foundation, Citation2021). The Lean LaunchPad materials and platform are based on The Startup Owner’s Manual and the Business Model Canvas (S. G. Blank & Dorf, Citation2012). They stress the importance of entrepreneurial immersion (concentrated exposure to business development and formation), hypothesis-driven customer discovery (validation of the business idea, target market, and customers’ needs and pain points through interviews and surveys), and business model validation (process to test and refine to ensure the business is viable and scalable) to achieve product-market fit (the degree to which a product satisfies market demand). The selection criteria include detailing the market size and describing the technology’s fit on the traditional Business Model Canvas (Strategyzer, Citation2020) initially designed for software, and the Lean Startup Canvas (S. Blank, Citation2013) adapted specifically for startups. However, ATTT and healthcare standards may follow unique development methodology; thus, a mismatched canvas may not be as helpful for AT teams and prevent them from being enrolled in the NSF or related programs offered by NIH (Grants.gov) and the nonprofit organization VentureWell (VentureWell, Citation2023).

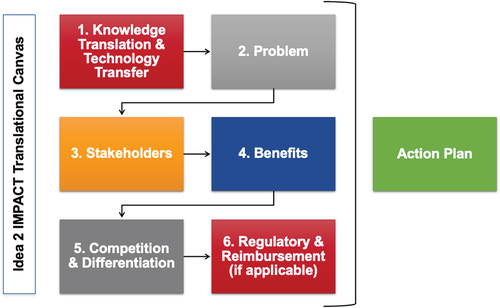

Pitt Translational Canvas

To address the mismatched canvas, University of Pittsburgh researchers developed the Pitt Translational Canvas (). The Pitt Translational Canvas is a linear and more generalizable model than the traditional TT methodology that includes identifying the problem, stakeholders, solution, its benefits, its competition, and differentiation to develop a translational action plan. This model was implemented in an in-person course with an initial cohort of three teams which resulted in 3 unique action plans, an average increase in innovation self-efficacy, and one of the teams receiving an innovation award (Goldberg, Citation2018).

Online training to promote adoption of the Translational Canvas for AT

Over several decades there has been a shift in popularity and acceptance of less traditional and more diverse educational models, including online courses, from the traditional in-person classroom model. Research has shown that online or distance education can result in students outperforming in-person education when paired with engaged instructors, collaborative stakeholders, flexibility, and relevant, high-quality content (Howlett et al., Citation2009; O’Doherty et al., Citation2018; Shachar & Neumann, Citation2003; Yousef et al., Citation2015). Online training has increased the ability of professionals to obtain valuable continuing education without the constraints of time or geographical location (L. R. Goldberg & Crocombe, Citation2017; O’Doherty et al., Citation2018).

Mixed success has been reported for completely asynchronous online courses that allow learners to complete a course in their own timeframe, typically attributed to non-engaging content and low interactivity between learners (Gamage et al., Citation2020; Setia et al., Citation2019). Studies have found that blending asynchronous learning with synchronously facilitated interactions for a sense of community increases learner satisfaction. A flipped classroom approach, which can be used in online or in-person environments, where students put into practice what was learned on their own time (Connor et al., Citation2014; Rhim & Han, Citation2020; T. Wang et al., Citation2021; Yardley et al., Citation2012), increases learner engagement, completion rates, knowledge retention, and content use. Careful consideration should be given to a course’s design, structure, and content (Cao et al., Citation2021; Rhim & Han, Citation2020; Vallée et al., Citation2020; Zheng et al., Citation2015). In particular, videos, often used as a leading source of content for online courses, should be short and engaging. Guo et al. (Citation2014) found that segments that were 6 minutes or less, talking heads interspersed with slides, and tablet drawing tutorials had more success in viewing completion than traditional classroom-style lectures.

Sound pedagogy for in-person and online training includes matching key learning objectives with valid assessments at multiple time points. A review of assessment tools for assessing technology transfer readiness conducted by Zorrilla et al. demonstrated that tools have been similarly driven toward commercialization and do not include implications on or insights from stakeholders or the technology’s likelihood of adoption. Trainings facilitated by NIH, NSF (I-Corps and its nodes, Citation2023), and VentureWell measure TT variably and inconsistently. The Technology Translation Readiness Assessment Tool (TTRAT) was recently developed to fill this gap as an evaluation tool for the market readiness of a proposed product that looks beyond just commercial success. It is composed of six domains or subscales: 1) Problem, 2) Stakeholders, 3) Solutions, 4) Competition & Differentiation, 5) Team, and 6) Sustainability and three readiness levels: 1) Early Readiness: Concept has been postulated at a basic level, 2) Emerging Readiness: Concept and application of idea have been formulated but need further developing, and 3) Mature Readiness: Concept and application of the idea have been thoroughly formulated and are ready for product testing and/or development (Zorrilla et al., Citation2022).

Objectives

Current ATTT training and assessment gaps underscore the need to help raise awareness and train disability and rehabilitation researchers and entrepreneurs for increased success of ATTT. This study aimed to address these gaps through two unique objectives:

Objective 1: Develop a multi-phased training intervention to meet the tech transfer needs of AT innovators in small businesses, universities, and nonprofit organizations

Objective 2: Evaluate the training intervention effectiveness

Methods

Objective 1

General development framework (quality implementation framework)

The multi-level, sequential training program was developed using the Quality Implementation Framework (QIF) (Meyers et al., Citation2012). The QIF indicates that a dynamic and iterative process of implementation influences outcomes by continuing to revisit needs assessments, adaptations, implementation teams and plans, technical assistance strategies, feedback structures, and assessment strategies to improve future applications.

We followed four QIF phases (). All content was developed by a content development team, experts with experience in 1) AT and rehabilitation development, engineering, and product design, 2) education, 3) participatory action design, 4) the University of Pittsburgh Innovation Institute’s Education and Outreach Director and an Executive-In-Residence, and 5) developers of the University of Pittsburgh translation course. Development of each level was also informed by our key stakeholders (people who use AT, Advisory Board members, mentors, and specialty organizations).

The content development team conducted a review of existing open-source content, including those from well-known TT centers and resources like the Center on Knowledge Translation for Technology Transfer, the National Rehabilitation Information Center, Lean LaunchPad, VentureWell, and the Association of University Technology Managers Learning Center.

Ethics and the internal review board

To ensure that appropriate steps were taken to protect the rights and welfare of humans participating in the training intervention, the IMPACT Center’s content development team submitted a protocol to the internal review board. Based on the information provided, it was determined that the project did not meet the regulatory definition of “human subjects research,” and therefore did not require IRB review and approval. Although the project does involve people in various ways, they are not the subject of the study and therefore are not “human subjects.” Instead, it could be defined as a “systematic investigation” that is not “designed to contribute to generalizable knowledge” about people but the inventions and ideas being commercialized.

QIF phase 1 & 2: host setting, content, targets, structure, and recruitment

idea 2 IMPACT (i2I): Translating Assistive Health Technologies and Other Products (Level 1) was developed and is hosted on Coursera, a common massive open online course (MOOC) platform, because of content development team’s familiarity with having developed a MOOC on Coursera called “Disability Awareness and Supports” with over 10,803 learners as of April 2023. In addition, Coursera also conforms with the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 2.0 AA published by World Wide Web Consortium to ensure all course content is accessible.

i2I was designed to include two modalities: 1) a 6-week MOOC that is entirely asynchronous; and 2) a closed “BootCamp” that has flipped learning components. Both versions offer flexible, self-paced online modules to provide participants with key concepts and information. The IMPACT BootCamp (Level 1; BootCamp) offers synchronous online recitations where participants present specific deliverables, receive live feedback from colleagues and mentors, and engage in focused discussion over Zoom.

Convenience sampling methods were used to recruit participants for i2I through project listservs and newsletters, social media, and the Coursera platform. In addition to the MOOC recruitment methods, BootCamp participants were recruited through direct project e-mails, webinars, and the NIDILRR grantee lists. All teams applied via a Qualtrics survey.

Objective 2

We evaluated the training intervention’s effectiveness through a two-fold approach, encompassing the assessment of BootCamp and StartUp using two primary outcome measures: 1) a post-training participant satisfaction survey and 2) the validated TTRAT.

Post training surveys – participant satisfaction

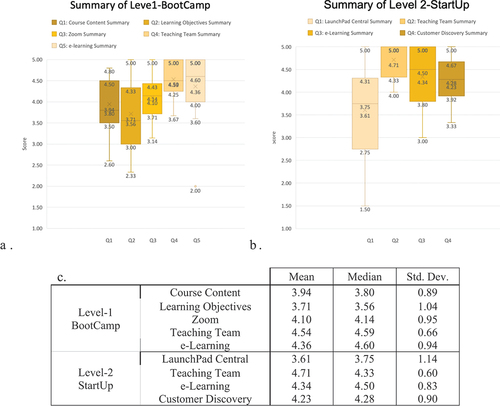

Participant satisfaction was measured at the end of each level using a post-training satisfaction survey on Qualtrics using a Likert scale from 1 to 5, with 1 being poor, 2 fair, 3 good, 4 very good, and 5 excellent. For areas not pertaining to a particular team, such as Regulatory and Reimbursement, teams were permitted to rate that question as Not Applicable. A score of 0 was applied to the analysis. The post-training satisfaction survey was administered and hosted on Qualtrics. The BootCamp survey was comprised of 5 sections: 1) Course Content, 2) Learning Objectives, 3) Zoom for Recitations, 4) the E-learning Experience, and 5) the Teaching Team (mentors and instructors). The StartUp survey included two additional sections: 1) the learning platform GLIDR, formerly known as LaunchPad Central), and 2) Customer Discovery. All teams were requested to complete the survey during the last training session, and reminders were sent one and three weeks later.

TTRAT data analysis

To further evaluate the effectiveness of the training, the TTRAT, developed and validated by Zorrilla et al. (Citation2022), is used four times throughout the training program for participants and mentors to assess innovation progress. The TTRAT assessment is used pre-, mid-, post-BootCamp, and post-StartUp.

Actual tech transfer progress

Training intervention deliverables and data from the IMPACT Center’s NIMS (NIDILRR Innovation Management Software) database were utilized as a tertiary approach to extract additional TT progress outcomes. NIMS data is populated by public searches and surveys sent to NIDILRR grantees for feedback on project outputs. The final pitches were reviewed, and data from NIMS was scrutinized by two authors for items such as intellectual property protection, funding, and awards.

Results

Objective 1

The QIF guided the development of three unique interventions: idea 2 IMPACT (i2I): Translating Assistive Health Technologies and Other Products (Level 1), IMPACT StartUp (Level 2), and IMPACT Accelerate (Level 3). Each of the interventions and associated results are detailed below.

idea 2 IMPACT (i2I): Translating Assistive Health Technologies and Other Products (Level 1)The goal of i2I was to introduce novice innovators interested in translating an idea into practical applications to the knowledge of ATTT best practices. i2I guided trainees step by step through the experience of developing an entrepreneurial idea. The course included case studies covering various disability and rehabilitation technologies.

QIF Phase 1 & 2: Content, Targets, Structure, and Recruitment. i2I participants focused on one stage of the modified Pitt Translational Canvas per module. They identified the problem, analyzed stakeholders, defined their solution, described its benefits, researched the competition, articulated differentiators, researched regulatory and reimbursement, and created an action plan. The module schedule () is identical for MOOC and BootCamp, except that each BootCamp module include a synchronous online recitation and office hours with assigned mentors. Mentors had experience in entrepreneurship, AT, or rehabilitation and were matched according to the team’s area of focus.

Table 1. Initial modules, topics, and content of i2I.

BootCamp has been offered to 3 cohorts of 8 to 12 teams and is a pre-requisite for Level 2 StartUp. To fulfill the IMPACT Center’s and NIDILRR’s knowledge translation mission to awardees past and present, preference was given to NIDILRR grantees. Any remaining slots were offered to teams with the most relevant backgrounds (i.e., topics most closely related to disability and rehabilitation) and those seeking NIDILRR funding. BootCamp participants were provided a “Certificate of Completion” at no cost to participants as NIDILRR grant funds covered expenses. A certificate of completion was provided to MOOC students by Coursera with an option to receive a “verified certificate” for a fee.

QIF Phase 3: Ongoing structure and changes once implementation begins. Fundamental changes to the BootCamp program (indicated in bold in ) were based on post-training surveys of trainees and mentors, utilization of the QIF, TTRAT scores, and stakeholder feedback sessions to review the program’s resources and modules. A graphics design company was hired to design a pitch deck template, garnering uniformity among deliverables, business knowledge acquisition, and slides tailored to investor presentation expectations. The initial course consisted of a 1:4 mentor-to-mentee ratio and optional office hours. Feedback from mentors and teams that participated in office hours informed that office hours were beneficial and engaging; thus, mandatory office hours and a 1:1 mentor-to-mentee ratio were implemented.

Table 2. BootCamp changes in bold.

IMPACT StartUp (Level 2)

Level 2 IMPACT StartUp (StartUp) was developed to build upon BootCamp and modeled after the NSF I-Corps program. StartUp engaged teams in the customer discovery process to better understand stakeholders’ needs and pain points.

QIF phase 1 and 2: host setting, content, and recruitment

We chose to host StartUp on GLIDR, a product management software that allows teams to input and track customer discovery, share feedback, and validate hypotheses on each of the Business Model Canvas components with each other and mentors. Teams that completed all BootCamp requirements and met the additional acceptance criteria () could apply for StartUp. StartUp was designed to support 4–6 teams per cohort, and included a consistent schedule and team requirements ( and ).

Table 3. StartUp acceptance criteria.

Table 4. StartUp course content. In addition to videos, readings, lecture topics, and weekly presentations during recitations, teams must conduct customer discovery interviews and report on them.

In addition to videos, readings, lecture topics, and weekly presentations during recitations, teams were required to conduct customer discovery interviews and report on them. Teams interviewed at least 50 potential stakeholders (i.e., partners, customers, or others who experience the particular problem being explored). Like BootCamp, teams were paired with a mentor to guide their customer discovery process and fill in gaps. Teams received a $25,000 award to support activities related to their TT process. 14 teams finished StartUp.

QIF phase 3: ongoing structure and changes once implementation begins

Changes to StartUp (, changes in bold) were implemented similarly to BootCamp. Programming was extended to accommodate additional guest speakers and various types of pitches (elevator, product, and technical pitches) to prepare for future funding requests.

Table 5. Changes to StartUp in bold.

Addition of IMPACT accelerate (Level 3)

A partnership with a local nonprofit consulting group (Fourth River Solutions, Citation2023) was established to bring additional services to the participating teams as Level 3 Accelerate. Over a 6-week engagement, a consulting team (1 project manager and 4 consultants) worked on a pre-determined, customized scope of work that may consist of the following: Value Proposition Assessment, Marketing Analysis, Competitor Analysis, Customer Discovery, Regulatory Assessment, Indication Prioritization, Business Plan, Investor Pitch Presentation, and Exit Strategy. Six teams completed Accelerate. To qualify for Accelerate, teams must have completed StartUp.

Objective 2

We focused the evaluation on two of the multi-level components: BootCamp and StartUp. We chose these two levels because of the consistency in data collection related to completing the TTRAT before and after BootCamp and after StartUp. () Future assessments will include both the i2I MOOC modality and Level 3 Accelerate.

Table 6. Number of teams that completed the TTRAT™ at each time point.

Satisfaction survey data analysis

The post-training satisfaction survey was divided into 5 topic areas (), with sub-questions in each (Appendix Figures A1-A8). As displayed in , when each category of questions was summarized and averaged, participants rated each as Good or Very Good overall (). Participants rated all subareas of the training as Good, Very Good, or Excellent on average, and highly regarded the informational videos, e-learning process, feedback from the teaching team and mentors, and the customer discovery process (Appendix Figure A1-A8).

Figure 3. Summary of satisfaction feedback from post-training surveys for BootCamp and StartUp. (a) summary of 5 topic categories from BootCamp survey. (b) summary of 4 topic categories from StartUp survey. (c) mean, Median and standard deviation represented in a and B. Likert scale from 1 to 5, where 1 is poor, 2 is fair, 3 is good, 4 is very good, and 5 is excellent, not applicable is 0. (BootCamp N = 17; StartUp N = 10).

To test the continual satisfaction of the training, we compared the heterogeneity of data between teams that participated in BootCamp (N = 18, Group 1), to teams that participated in both BootCamp and StartUp (N = 7, Group 2).

The Total Z-score of −0.93 with a p-value of 0.35 suggests that there is no significant difference between the two groups compared in terms of overall satisfaction with the training. There is also no significant difference between the two groups for satisfaction within the 4 domains.

TTRAT data analysis

Technology transfer readiness was measured at three unique time points: pre-BootCamp, post-BootCamp, and post-StartUp using the TTRAT on Qualtrics. A varying number of teams completed the TTRAT, and only the 18 teams that completed the TTRAT both pre- and post-BootCamp were considered for the analysis (). provides evidence of the diversity of technology types, technology readiness levels (TRLs), roles, and levels of experience in TT and is detailed in Tables A1 and A2. However, for the TTRAT data, group 1 and group 2 demonstrated heterogeneity, indicating that the two groups have distinct characteristics or differences in certain aspects. This could imply variations in their responses, performance, or other measurable factors related to the TTRAT assessment.

Table 7. BootCamp Teams’ TTRAT Readiness Levels (pre-BootCamp), technology, and level of experience. Note: early Readiness: 59.9% or below (74 or less), emerging Readiness: 60%-79.9% (75–99), mature Readiness: 60%-79.9% (100–125); technology type: freeware includes software, mobile applications, and programs.

BootCamp analysis

A Wilcoxon Test was conducted to compare the course’s effect on TT readiness by looking at TTRAT scores () broken down by readiness domain for Group 1 () and Group 2 (). The results indicate that except for the “Problem” domain in both groups, and the “Team” domain of Group 2, all other domains showed a statistically significant improvement post-BootCamp as indicated by p-values ≤0.05. These results suggest that the course improved technology readiness levels.

Table 8. Heterogeneity test result of TTRAT.

Table 9. Wilcoxon signed ranks test comparison of pre-BootCamp and post-BootCamp by domain in group 1 (N = 8).

Table 10. Wilcoxon signed ranks test comparison of pre-BootCamp and post-BootCamp by domain in group 2 (N = 8).

StartUp analysis

A Wilcoxon Test using SPSS v.28 with an alpha of .05 was performed to compare the effect of the training on TT readiness by looking at TTRAT scores at two time points broken down by readiness domain ().

Table 11. Wilcoxon signed ranks test comparison of post-BootCamp and post-StartUp by domain (N = 10).

The result indicated that the mean score improved in all domains, with statistically significant differences (p-value <0.05) in the Stakeholders, Solution, Competition & Differentiation, Sustainability. Moreover, the Grand Total scores for post-BootCamp and post-StartUp demonstrated a significant difference (p-value = 0.005). The findings indicate that StartUp had an impact on the readiness of a solution ().

Table 12. Summary of TTRAT Wilcoxon signed ranks test comparison analysis of pre-BootCamp and post-BootCamp by domain in Group1(N = 8) and group 2 (N = 10); and of pre-BootCamp and post-StartUp by domain (N = 10).

Actual tech transfer progress

Final pitches were reviewed for additional technology transfer outcomes and data in the NIMS database. Eighteen outcomes () were identified across categories of additional “intellectual property protection,” “funding,” “awards,” and ‘other,” with the majority in additional funding. One testimonial of merit comes from Nate Davis, Chief Executive Officer of The Ramp Doctor, a home-modification company that helps people with disabilities and seniors age successfully in their homes when he said: “If it wasn’t for the IMPACT Center, my idea would still be sitting on a shelf.” Instead they have received additional funding and generated novel revenue.

Table 13. Outcomes identified from participating teams.

Discussion

A three-phased training intervention was developed to meet the TT needs of innovators in small businesses, universities, and nonprofit organizations. Using the TTRAT, we determined that the training is effective in helping to advance technology readiness.

The results of the heterogeneity test showed that for the satisfaction survey, the majority of the data did not exhibit heterogeneity. However, for the TTRAT, group 1 and group 2 demonstrated heterogeneity. This might be because the TTRAT is a relatively objective testing tool with less bias, allowing it to differentiate between distinct populations more sensitively. Group 2 was recruited based on the conditions of group 1, with an additional five requirements. On the other hand, satisfaction surveys are more subjective and may be influenced by individual perceptions, emotional states, or personal experiences, potentially leading to more uniform responses across different groups despite varying conditions or interventions.

TTRAT domain and Grand Total scores significantly increased post-BootCamp, except for the problem. However, this is not surprising, as most teams already understand the problem they are trying to solve when developing their products. The lower satisfaction rates for some learning objectives suggest that certain aspects of the training program were more challenging or less relevant to participants’ needs. However, the training intervention significantly impacted domains significant for commercializing technologies.

In the initial Bootcamp phase, participants engaged in activities focused on understanding and clarifying the problem, coupled with identifying barriers and facilitators to effective technology transfer. The tangible outcomes of this stage included the establishment of a Proof of Concept, a comprehensive list of stakeholders, and the initiation of customer channels. Drawing from the literature base, this stage leveraged insights into problem-solving methodologies and effective stakeholder engagement (Choi, Citation2009; Zorrilla et al., Citation2022).

Moving into the StartUp phase, the emphasis shifted toward conducting a comprehensive customer discovery process and implementing an evidence-based tech transfer readiness assessment. The outcomes sought at this stage involve the validation of business viability and addressing customer pain points through data-driven decision-making and optimization. The literature informing this phase encompassed best practices in customer-centric approaches, as well as strategies for tech transfer readiness assessment found in relevant academic and industry publications (Blank & Dorf, Citation2012; R. H. Wang et al., Citation2021; Zorrilla, Citation2022).

As participants progressed to the Accelerate stage, key activities involved the development of a robust business plan and the formulation of a strategic roadmap. The desired outcomes included a comprehensive roadmap equipped with measurable success metrics. The literature base influencing this stage encompassed strategic management and business planning literature, providing a theoretical foundation for the development of effective business strategies and success metrics within the context of technology transfer (Kirsch et al., Citation2009; Lane, Citation2003).

A limitation of this study is that the training was evaluated using a pre-post design without a control group and a relatively small sample size. Therefore, it is difficult to establish a causal relationship between the training, the observed gains in the TTRAT scores, and the generalizability of the findings. Thus, a larger study with more diverse participants is needed to confirm the effectiveness. The study also did not assess the long-term impact of the training intervention on the transfer of ATs to the market due to the time it can require, often attributed to clinical trial lengths, funding gaps, and regulatory pathway requirements.

The training intervention developed in this study holds promising potential for broader application in diverse contexts and settings, extending beyond the confines of the original target audience. The carefully crafted multi-level training program, along with its underlying formula informed by relevant literature, presents a framework that could serve as a successful model for other institutions aiming to foster assistive technology tech transfer.

The evaluation method employed in our study, utilizing the Technology Transfer Readiness Assessment Tool (TTRAT), has shown to be effective in assessing the readiness of our multi-level assistive technology-focused technology translation program. The TTRAT provided a comprehensive, structured, and data-driven approach to evaluating various dimensions of our program. It allowed us to identify actionable insights, strengths, weaknesses, and areas for improvement, refinement and future development of course content and participant needs. While designed for our AT-focused program, the framework can be modified to suit other programs across diverse fields.

By strategically incorporating partnerships, engaging in focused feedback through diverse focus groups, featuring additional expert guest speakers, and expanding the existing Accelerate program, we anticipate further strengthening the efficacy and relevance of the training. Notably, Accelerate is set to evolve with the introduction of dual pathways, including an extended format culminating in a Demo Day. This innovation not only provides participating teams with an opportunity to showcase their technological advancements but also serves as a platform to facilitate collaborations and attract potential funding from investors. As we embark on future endeavors, the insights gained from this initiative could potentially guide and inspire similar programs in other institutions seeking to make significant strides in assistive technology tech transfer. This scalability and adaptability underscore the versatility of our approach, suggesting its potential applicability as a successful model for advancing assistive technology innovation across various educational and research settings.

Conclusion

In summary, the IMPACT Center’s Multi-Level Training Initiative stands as a promising foundation for equipping researchers and aspiring entrepreneurs with the essential skills for effective technology transfer. The Technology Transfer Readiness Assessment Tool (TTRAT) provides a valuable evaluative framework specifically tailored to assess emerging technologies, with a particular focus on their potential success in the unique landscape of assistive technology. What sets this training apart is:

In-depth focus on understanding assistive technology development: This program offers dedicated attention to unraveling the complexities of assistive technology, ensuring participants gain a deep understanding of its nuances.

Emphasis on demonstrating value in a specialized market: It addresses the challenge of showcasing the significance of assistive technology, even within a niche market, providing strategies for effective communication of its benefits.

Tailored insights and skills for the field: Participants acquire insights and skills specifically crafted to tackle the distinct challenges and opportunities within the realm of assistive technology.

A versatile, industry-agnostic framework: The program provides a structured approach that extends beyond specific industry boundaries, equipping participants with adaptable tools applicable across diverse sectors.

Holistic understanding of user needs: The training ensures a holistic approach toward understanding the diverse needs of users, guiding participants to develop solutions that are truly impactful through customer discovery interviews.

Expert-led mentorship and guidance: Participants benefit from the mentorship of industry experts, receiving personalized guidance throughout the program to refine their skills and insights and challenging them to think outside the box.

As we take these initial steps in the translational framework, it becomes evident that the approach extends beyond conventional success metrics in industry. The trajectory includes the development of a broadscale online learning program, strategically designed to fill existing gaps in knowledge and expertise. By expanding these efforts, we aim to provide a tailored and comprehensive technology transfer assessment and training platform uniquely crafted for assistive technology innovators. This not only propels the field forward but also underscores our commitment to fostering impactful and sustainable advancements in assistive technology.

Supplemental Figures and Table.docx

Download MS Word (528.5 KB)Acknowledgements

This project was supported by the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research, a Center within the Administration for Community Living (ACL), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). These results do not necessarily represent the policy of NIDILRR, ACL, or HHS, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data is available upon request.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/10400435.2024.2384940

Additional information

Funding

References

- Assistive technology market estimates: Rapid growth ahead [website]. (2019). Bureau of Internet Accessibility. Retrieved April 20, 2022, from https://www.boia.org/blog/assistive-technology-market-estimates-rapid-growth-ahead

- Blank, S. (2013, May). Why the Lean start-up changes everything. Harvard Business Review.

- Blank, S. G., & Dorf, B. (2012). The startup owner’s manual. Vol. 1: The step-by-step guide for building a great company (1st ed.). K&S Ranch, Inc.

- Cao, W., Hu, L., Li, X., Li, X., Chen, C., Zhang, Q., & Cao, S. (2021). Massive open online courses-based blended versus face-to-face classroom teaching methods for fundamental nursing course. Medicine, 100(9), e24829. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000024829

- Choi, H. J. (2009). Technology transfer issues and a new technology transfer model. Journal of Technology Studies, 35(1), 49–57. https://doi.org/10.21061/jots.v35i1.a.7

- Connor, K. A., Meehan, K., Newman, D. L., Walter, D., Ferri, B. H., Astatke, Y., & Chouikha, M. F. (2014). Collaborative research: Center for mobile hands-on STEM [Paper presentation]. ASEE Annual Conference and Exposition 2014, Indianapolis, Indiana.

- Foundation, N. S. (2021). National science foundation innovation corps (I-Corps™) biennial report (national science foundation innovation corps (I-Corps™). Biennial Report, Issue. https://nsf-gov-resources.nsf.gov/2022-06/NSFI-Corps2021BiennialReport.pdf

- Fourth River Solutions. (2023). Fourth River solutions. We are 4RS. Retrieved March 19, 2023 from http://www.fourthriversolutions.org

- Gamage, D., Perera, I., & Fernando, S. (2020). MOOCs lack interactivity and collaborativeness: Evaluating MOOC platforms. International Journal of Engineering Pedagogy (iJEP), 10(2), 94–111. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijep.v10i2.11886

- Global report on assistive technology. (2022). World Health Organization and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- Goldberg, L. R., & Crocombe, L. A. (2017). Advances in medical education and practice: Role of massive open online courses. Advances in Medical Education and Practice, 8, 603. https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S115321

- Goldberg, M. (2018). Idea 2 impact: Foster-ing clinician Scientists’ innovation skills [Conference Presentation]. VentureWell OPEN Conference 2018, Austin, TX.

- Grants.gov. PA-18-314: Innovation Corps (I-Corps) at NIH program for NIH and CDC translational research (Admin Supp). Retrieved January 10, 2023 from https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/pa-files/PAR-22-073.html

- Guo, P. J., Kim, J., & Rubin, R. (2014). How video production affects student engagement: An empirical study of MOOC videos [Paper presentation]. Proceedings of the first ACM conference on Learning@ scale conference, Atlanta, Georgia.

- Higgins, E. (2022). Barriers and facilitators to technology transfer of NIDILRR grantees. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology, 17(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/17483107.2020.1820085

- Howlett, D., Vincent, T., Gainsborough, N., Fairclough, J., Taylor, N., Cohen, J., & Vincent, R. (2009). Integration of a case-based online module into an undergraduate curriculum: What is involved and is it effective? E-Learning & Digital Media, 6(4), 372–384. https://doi.org/10.2304/elea.2009.6.4.372

- Kirsch, D., Goldfarb, B., & Gera, A. (2009). Form or substance: The role of business plans in venture capital decision making. Strategic Management Journal, 30(5), 487–515. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.751

- Lane, J. P. (2003). The state of the science in technology transfer: Implications for the field of assistive technology. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 28(3/4), 333–354. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024913516109

- Leahy, J. A., & Lane, J. P. (2010). Knowledge from research and practice on the barriers and carriers to successful technology transfer for assistive technology devices. Assistive Technology Outcomes and Benefits, 6(1), 73–86 Summer 2010.

- Meyers, D. C., Durlak, J. A., & Wandersman, A. (2012). The quality implementation framework: A synthesis of critical steps in the implementation process. American Journal of Community Psychology, 50(3), 462–480. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-012-9522-x

- O’Doherty, D., Dromey, M., Lougheed, J., Hannigan, A., Last, J., & McGrath, D. (2018). Barriers and solutions to online learning in medical education – An integrative review. BMC Medical Education, 18(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-018-1240-0

- Rhim, H. C., & Han, H. (2020). Teaching online: Foundational concepts of online learning and practical guidelines. Korean Journal of Medical Education, 32(3), 175. https://doi.org/10.3946/kjme.2020.171

- Setia, S., Tay, J. C., Chia, Y. C., & Subramaniam, K. (2019). Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) for continuing medical education–why and how? Advances in Medical Education and Practice, 10, 805. https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S219104

- Shachar, M., & Neumann, Y. (2003). Differences between traditional and distance education academic performances: A meta-analytic approach. International Review of Research in Open & Distributed Learning, 4(2), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v4i2.153

- Strategyzer, A. Z. I. (2020). Business Model Canvas – Download the official template. https://www.strategyzer.com/canvas/business-model-canvas

- Vallée, A., Blacher, J., Cariou, A., & Sorbets, E. (2020). Blended learning compared to traditional learning in medical education: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(8), e16504. https://doi.org/10.2196/16504

- VentureWell. (2023). The E-Team program. Retrieved January 10, 2023 from https://venturewell.org/e-team-grant-program/

- Wang, R. H., Kenyon, L. K., McGilton, K. S., Miller, W. C., Hovanec, N., Boger, J., Viswanathan, P., Robillard, J. M., & Czarnuch, S. M. (2021). The time is now: A FASTER approach to generate research evidence for technology-based interventions in the field of disability and rehabilitation. Archives of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, 102(9), 1848–1859. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2021.04.009

- Wang, T., Sun, C., Mei, Y.-J., Hou, C.-Y., & Li, Z.-J. (2021). Massive open online courses combined with flipped classroom: An approach to promote training of resident physicians in rheumatology. International Journal of General Medicine, 14, 4453. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJGM.S325437

- Yardley, S., Teunissen, P. W., & Dornan, T. (2012). Experiential learning: AMEE guide No. 63. Medical Teacher, 34(2), e102–e115. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2012.650741

- Yousef, A. M. F., Chatti, M. A., Wosnitza, M., & Schroeder, U. (2015). A cluster analysis of MOOC stakeholder perspectives. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 12(1), 74–90. https://doi.org/10.7238/rusc.v12i1.2253

- Zheng, S., Rosson, M. B., Shih, P. C., & Carroll, J. M. (2015). Designing MOOCs as interactive places for collaborative learning [Paper presentation]. Proceedings of the Second (2015) ACM Conference on Learning@ Scale, Vancouver, BC, Canada.

- Zorrilla, M., Ao, J., Terhorst, L., Cohen, S. K., Goldberg, M., & Pearlman, J. (2022). Using the lens of assistive technology to develop a technology translation readiness assessment tool (TTRAT)™ to evaluate market readiness. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology, 19(4), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/17483107.2022.2153936