Abstract

Phenomenon

Developing modern medical curricula requires collaboration between different scientific and clinical disciplines. Consequently, institutions face the daunting task to engage colleagues from different disciplines in effective team collaboration. Two aspects that are vital to the success of such teamwork are “team learning behavior” by all team members and “leader inclusiveness behavior” by the team leader. Team members display team learning behavior when they share information, build upon and integrate each other’s viewpoints. The team leader can promote such team learning by exhibiting inclusiveness behavior, which aims to encourage diversity and preserve individual differences for an inclusive workplace, nurturing engagement in teamwork. There is a paucity of in-depth research on leader inclusiveness behavior in the field of medical education. This case study aimed to offer unique insight into how leader inclusiveness behavior manifests itself in a successful interdisciplinary teacher team, demonstrating team learning behavior in undergraduate medical education.

Approach

We conducted a qualitative, ethnographic case study using different but complementary methods, including observations, interviews and a documentary analysis of email communication. By means of purposive sampling, we selected an existing interdisciplinary teacher team that was responsible for an undergraduate medical course at Maastricht University, the Netherlands, and that was known to be successful. Chaired by a physician, the team included planning group members and tutors with medical, biomedical, and social sciences backgrounds as well as student-representatives. In the course of one academic year, 23 meetings were observed and recorded, informal interviews were conducted, and over 100 email conversations were collected. All data were submitted to a directed content analysis based on team learning and leader inclusiveness concepts.

Findings

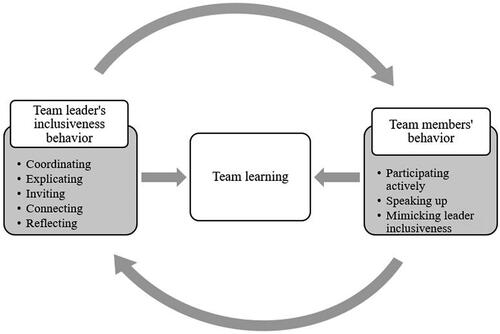

Leader inclusiveness behavior became evident from verbal and non-verbal interactions between the team leader and team members. Leader inclusiveness behavior that facilitated team learning behavior manifested itself in five actions undertaken by the team leader: coordinating, explicating, inviting, connecting, and reflecting. Similarly, team members facilitated team learning behavior by participating actively, speaking up behavior, and mimicking leader inclusiveness behavior. These behaviors demonstrated engagement and feelings of inclusion, and reinforced leader inclusiveness behavior by creating additional opportunities for the leader to exhibit such behavior.

Insights

This case study responds to the need for inclusive leadership approaches in medical education. Our findings build upon theoretical knowledge on team learning and leader inclusiveness concepts. By studying behaviors, interactions and documents we obtained in-depth information on leader inclusiveness. Our findings are unique in that they demonstrate how leader inclusiveness behavior manifests itself when leaders interact with their team members. This study provides health professionals who are active in education with practical suggestions on how to act as a successful and inclusive leader. Finally, the behaviors identified open up avenues for future professional development initiatives and future research on team leadership.

Supplemental data for this article is available online at here.

Introduction

Medical education institutions are under increasing pressure from accreditation bodies, professional associations, and national policies to continuously innovate their teaching practices. Facing the daunting task to design courses that reflect the complexities of present-day interdisciplinary healthcare practices,Citation1–6 these institutions rely on their staff to collaborate across various disciplines, from medicine to the biomedical and social sciences.Citation7 Only with such an integrated approach across disciplines can patient problems, that are inherently interdisciplinary, become a trigger for learning.Citation1,Citation7–9 Consequently, many health care professionals are now put in the challenging position to work in interdisciplinary teacher teams.Citation10 Indeed, previous research has reported that working in such teams is not yet fully accepted or the norm in medical education, even though such reserve may negatively affect the quality of education.Citation10,Citation11

This begs the question: What do we know about successful teams? Research has warned us that simply bringing individual experts together does not automatically translate to successful teamwork.Citation12,Citation13 Other studies have emphasized the importance of team processes to team success.Citation14,Citation15 That is, how team members interact, how they negotiate their individual perspectives and their willingness to reconsider their individual views to form a new, shared team perspective is what defines a team’s success.Citation14,Citation15 Despite the substantial research on teamwork in healthcare,Citation16,Citation17 surprisingly little is known about teamwork in medical teaching.Citation11 Recently, we as a research team found that teams of teachers from different disciplinary backgrounds are not automatically successful and their different ways of working influence the quality of the courses they produce.Citation11 What also came to the fore from our previous research was the crucial role the team leader plays in mediating the team success.Citation18 We saw a need to explore how team leaders orchestrate successful teamwork in current medical education, allowing team members to unlock their full potential and unique capacities.Citation19 To address this research gap, we undertook a longitudinal ethnographic case study of a successful interdisciplinary teacher team, zooming in on leadership behavior.

We used two concepts from organizational behavior research,Citation20 that is, “team learning” and “leader inclusiveness”, to inform our study. Team learning refers to specific behaviors displayed by all members of the team, such as sharing knowledge, acting upon and discussing this knowledge, and, finally, exposing, negotiating and integrating different viewpoints to come to agreements or new shared ideas, views, or concepts (also coined “constructive conflicts”).Citation21,Citation22 Leader inclusiveness, on the other hand, has been defined as the “words and deeds exhibited by a leader or leaders that indicate an invitation and appreciation for others’ contributions.”Citation20 Research from various fields has consistently shown that effective team learning only occurs when certain conditions are met. For instance, the environment must be psychologically safe so that team members feel free to share and discuss,Citation20 all team members must take an effort to cross their disciplinary boundaries to accomplish tasks,Citation23 and the team leader must possess qualities that promote team learning.Citation18 By exhibiting inclusiveness behavior, team leaders can create such psychological safety:Citation17,Citation20 They can invite and include voices and perspectives that might otherwise be absent in discussions and decision-making,Citation20,Citation24,Citation25 allowing team members to become engaged and be committed to work together.Citation18,Citation20,Citation26 The following example from a pioneering study on team learning processes illustrates that, even though team performance relies heavily on team processes, the leader’s behavior is just as important: A lead surgeon told his team tasked with implementing an innovative cardiac surgery technology that: “you have to make this work together”. Rather than emphasizing experts’ individual contributions, he made it clear that it was all about what the group would be able to accomplish.Citation27 It was this empowering and motivating behavior that escorted his team toward success.Citation27

Having remained unexplored in the field of medical education, there is at present a paucity of in-depth research on leader inclusiveness behavior. Previous studies, moreover, have made explicit calls for interdisciplinary teamwork in medical education,Citation28 leadership development,Citation29–31 diversity and inclusion,Citation32 and for research that identifies the specific actions that effective leaders undertake to promote their team’s success.Citation33 Such insights may help team leaders to shape their teamwork in a way that modern-day medical education requires. The focus of our groundwork was therefore on leadership in a team of teachers from various disciplinary backgrounds. More specifically, we set out to unpack the inclusiveness behavior exhibited by a leader of a proven successful, interdisciplinary teacher team demonstrating team learning in medical education. To identify patterns of leader inclusiveness behavior, we conducted an ethnographic case study exploring the team’s verbal and non-verbal behaviors and interactions.

Method

Study design

We conducted an ethnographic case study, an approach that is fitting when studying human behavior as such endeavors typically require detailed information on social interactions in an interactive and interdisciplinary context.Citation34,Citation35 We longitudinally and iteratively collected data, using a triangulation of qualitative methods.Citation34,Citation36 By focusing on a case, we hoped to obtain rich information about the selected team leader’s behavior and we therefore took all opportunities to observe this team’s interactions. We entered the research setting with a preordained data plan, pre-identified informants and a specific timeline, which distinguishes this rapid ethnography from conventional ethnography.Citation35

Setting

This study focused on an interdisciplinary teacher team, responsible for the development, organization, execution, evaluation and improvement of an integrated, undergraduate medical course at Maastricht University (MU), the Netherlands. In this university, the medical curriculum is organized into thematic courses, such as the cardiovascular system. The main method of instruction is problem-based learning, which revolves around the discussion of problems or cases, for instance about a patient with chest pain, designed to enable authentic and integrated learning. Cases are discussed in tutorial groups of 10–12 students that are guided by a tutor. All course components are developed and executed by planning groups that consist of collaborating staff members from various professional disciplines (medical doctors, social scientists, biomedical scientists, etc.) as well as medical students. Each planning group is chaired by a team leader who meets with the various team members throughout the course: the tutors guiding the tutorial groups, student representatives from these groups, and the members of the planning group.

Sampling strategy

By means of purposive sampling,Citation36 we selected an existing interdisciplinary teacher team that was responsible for a second-year, eight-week medical course for a cohort of 316 students. We specifically selected this team as it was considered highly successful based on the following observations: 1) The team was categorized in a previous study as a successful team working with an integrated team approach and high levels of team learning,Citation11 2) the team had received high student evaluations,Citation11 and 3) the team leader was previously awarded the local “Honors award for education in the domain of Medicine” thanks to “exceptional qualities, being inspiring and role-modeling”. The team members included educators from the medical, biomedical, and social sciences. The team leader was a female physician who had four years’ experience as the leader of this team. During this study, the team leader was obtaining a master’s degree in Health Professions Education. See and for more background information on the team members.

Table 1. Demographics of the planning group members.

Table 2. Demographics of the tutors.

Data collection

Data collection took place in the course of the 2018–2019 academic year and included non-participant, semi-guided observations, informal interviews, and the collection of email communication and meeting notes. One research team member (TvO) observed 23 meetings between the team leader and several members of the team, of which nine times with the planning group, seven times with the tutors, and seven times with the student-representatives. Guided by the behavioral concepts of team learning and leader inclusiveness, the observer paid explicit attention to actions, gestures, body language, and affect taking place in the team (see Supplementary Appendix 1). Team meetings lasted between 30 minutes and 2.5 hours, were audio-taped, and were partly transcribed verbatim. Shortly after the meetings, field notes were transformed into concrete, more detailed reconstructions of the interactions that had taken place.Citation36 In addition to collecting over 100 team email conversations, we also gathered meeting notes to explore written agreements, actions and results. Immediately after the team meetings, TvO conducted short interviews with either the team leader or the members. The interview questions were tailored to the observations and focused on team learning and leader inclusiveness. In one interview, for instance, we probed into the team leader’s reasons for initiating an evaluation moment. We also interviewed both staff and students about their perceptions of their team leader’s specific contributions, such as her initiative to undertake an evaluation moment. This enabled both theoretical sampling for emerging insights and member-checking of perspectives and experiences reported during the observations.Citation36,Citation37

Data analysis

To be able to analyze the interactions in-depth and develop the coding scheme, the first six meetings were transcribed verbatim. Consequently, field notes, transcripts, e-mails and interviews were iteratively and independently coded by SM and TvO, using a directed approach to content analysis.Citation38 In such an approach, the “analysis starts with a theory or relevant research findings as guidance for initial codes.”Citation38 In our case, this meant that we started from the concepts of team learning and leader inclusiveness. From the team learning concept, we derived from the following initial codes: behaviors of sharing, building upon knowledge, and negotiating to achieve new, shared meanings.Citation14 By focusing on what the leader said, wrote, and didCitation20 to engage team members, we obtained the initial codes pertinent to the leader inclusiveness concept, such as codes capturing person-oriented, empowering behavior as well as task-oriented, directive behavior. In cases where we identified team-learning behavior, that is, when the team had dialogs and discussions about each other’s knowledge and ideas, we focused on the team leader’s preceding behavior to identify subcategories of leader inclusiveness codes. Guided by the initial codes thus obtained, SM and TvO independently coded passages, while also identifying new codes they deemed relevant to this study (e.g., showing emotions, asking questions, delegating tasks to interested members). The resulting coding scheme subsequently served to analyze the field notes of later meetings, interviews and emails. Finally, we combined individual codes and their subcategories into major, overarching categories that reflected the verbal and non-verbal interactions between the team leader and members. Ambiguities or disagreements about coding and category generation were discussed in the entire research team, until consensus was reached. In the Results section, each category will be briefly described, illustrated by representative quotes. Data analysis was managed using ATLAS.ti 8 software.

Reflexivity and research rigor

In addition to keeping a reflexive journal during fieldwork, SM reflected on the research process in an ethnographic research group and in the research team. To provide a rich and holistic understanding of leader inclusiveness behavior,Citation38 we used data and methods triangulation through data-collection in time and comparison of data from observations, interviews and a scrutiny of email communication.Citation35 The two researchers who had independently performed the data analysis presented their preliminary findings in several discussion groups to obtain input from different stakeholders. We also invited the leader and members of the team to review our data interpretation,Citation39 to which they responded that, although giving a true reflection of their team, the results could better articulate how the leader made explicit didactical knowledge (e.g., how to formulate exam questions, explaining the difference between replicating facts vs. applying knowledge).

This study received approval from the Dutch Association for Medical Education (NVMO) ethical review board (NVMO ERB 1054). All participants were informed that participation was voluntary, and gave informed consent.

Results

In this section, we will first focus on leader inclusiveness behavior displayed by the team leader and then on the behavior of team members (i.e., the planning group members, tutors and student-representatives). From the data we identified five actions undertaken by the leader that represented effective leader inclusiveness behavior: coordinating, explicating, inviting, connecting, and reflecting. By creating an environment in which the various team members felt engaged and committed to work together, these behaviors were found to promote team learning. In a similar fashion, team members promoted team learning and inspired the leader to exhibit more inclusiveness behavior by participating actively, speaking up, and mimicking the team leader’s inclusiveness behavior. Hence, effective leader inclusiveness behavior that contributed to team learning was a product of reciprocal interactions between the leader of the team and its members (see ).

Figure 1. A conceptual framework of interdisciplinary leader inclusiveness behavior, enhancing team learning behavior.

Team leader’s inclusiveness behavior

Coordinating

The team leader focused on the tasks they had to perform as a team. Being aware of the course outline and upcoming deadlines, she kept everyone up to date about this. In doing so, she allowed her team members to be involved in the process and to respond to the information received, by asking questions, providing input, or starting a discussion. In one of her e-mails, for instance, she wrote: “Enclosed is some preparation. Please, everyone, think and work along, then we finish sooner and better!.” Moreover, knowing the strengths and expertise of each of her team members, the team leader was sure to mobilize these: “I feel like a helicopter, sitting on top of it [the team process], but I want people to have their own task and are put in charge of it” (interview, September). Although she did not have content expertise on all course elements, she managed to ask the right people questions and to delegate tasks to the people she knew were able or willing to delve into the topic: “I want to make her owner of this. I think that she, a specialist in hereditary diseases, can think: what is the essence of this program? And she will like it, she did this last year as well” (field note, September). According to one team member, the team leader made her feel “free to work creatively, despite the fact that the team leader kept up the pressure of deadlines,” which was considered a strength.

Explicating

The team leader explicitly communicated about the course development process, its logistics and content, the course vision, and meaning of terminology. She often shared her didactic knowledge, as well as knowledge obtained from people outside the team, such as assessment experts. By continuously asking explicit questions about the course vision and the meaning of content, she invested in a shared vision and understanding of the course. For instance, she asked: “Is this ‘a-need-to-know’ question, something we will find in the end terms, something that should be tested, assumed knowledge?” (field note, October). Members soon learned to speak the same language and were able to discuss and even negotiate educational elements. We observed the team leader listen explicitly to all members asking questions, nodding, writing down what was told, and suggesting follow-up actions. As the leader explained: “I’m explicit. I don’t like to assume things. I rather name it, ask what’s actually meant and try to understand” (interview, April).

Next, the leader showed her vulnerable side by sharing her personal values, feelings, and emotions in honesty. This often triggered team members to offer a helping hand or ask clarifying questions, for instance in response to stress or frustrations shared (e.g., “What is needed to overcome current problems?”). Shared happiness and pride led team members to mimic and reinforce of positive statements made by the leader. Both in writing and in face-to-face communication, the leader expressed gratitude for everyone’s time and effort, for example by closing an e-mail as follows: “[…], Thanks for creating the doodle and […], thanks for working on Case 8 and 9. Everyone, thanks for this fruitful meeting” (e-mail, September). Not only did the team leader usually end her e-mails and meetings in this way, she was also very generous with giving signs of recognition which encouraged others to do the same.

Inviting

The team leader often invited team members to express their opinions, suggest ideas, and ask questions: “Let’s give it back to the group. Are we comfortable [about this], are we on track? Are there any doubts?” (field note, November). To set the stage for interaction, she raised many open questions at the start of each meeting, especially during the first meetings, where she asked student members: “What do you think?” Such questions were typically informal, short, and direct. Especially when others showed active participation and spoke up by raising questions, rather than giving the answer or telling people what to do, she posed reflective questions in return. In an interview, she explained: “I don’t want a right/wrong game, I want discussion” (interview, September). Facial expressions, such as looking confused or showing a question mark, also were intended to spark reactions from others.

In the meeting room, the leader made sure to sit next to and in between her team members, rather than at the head of the table. This way of positioning herself reflected her personal values and leadership goals, as she attached great value to other people’ views, enabling group discussions, and “being in-between” instead of “on top” of people. Finally, in her emails too, the team leader used inviting language, as in the following example where she addressed a team member who had been absent from a previous meeting: “We come together [on] Wednesday at 8.30, will you be there too? Hope so. With gratitude” (e-mail, October)

Connecting

The team leader often emphasized how the team could achieve its goals by being jointly responsible for the course, as evidenced by the frequent use of “we” and “us” in her communication: “Looking forward [to] seeing you, we’re going to rock!” (e-mail, September). In addition, she occasionally checked with her team whether they were still happy with the course and their teamwork, for instance by asking “This is fun, right?” (field note, October) .

When members participated actively in a fruitful discussion or negotiation, the leader often told the group how proud she was of her team or how much joy she took in achieving something together as a team. Laughter was an important ingredient of all meetings. Jokes were made between the many discussions, sometimes even in the heat of discussions. This seemed to be a deliberate strategy to connect: “I feel like a connecting leader. In that, I don’t mind making fun of myself” (interview, April).

Reflecting

The team leader seized many opportunities to reflect on the end product (the course), the team process, the power of the team and of its individual members, and on individual learning processes. For instance, when in a meeting the leader noticed that team members were losing their attention, as we could tell from their passive body language and distraction, she reflected on this team process and tried to energize everyone to finish the job: “Please guys, I know we sat down for a while. Quick and dirty’, we only have six minutes left” (field note, September).

As became clear from the interviews, emails, and meetings, the leader often reflected on team power, not only by emphasizing how unique the team was, but also by calling attention to individual strengths and weaknesses: “Dear [student-members], You have done an incredibly good job! Great to see that everything is up-to-date!” (e-mail, October). Oftentimes, when reflecting on her own capabilities, the leader inspired others to do the same or to react. For instance, when admitting she did not have sufficient knowledge of a subject, others would admit they did not either, would share knowledge and experiences, or would take over the task. The fact that the leader reflected on her personal improvement points also shone through in an interview: “Sometimes I notice I could have done something better or different[ly]. […] Now things are improving [smiles]” (interview, December).

Team members’ behavior

As shows, leader inclusiveness behavior was a product of continuous interactions between the leader of the team and its members. That is to say, not only did inclusiveness behavior originate in the leader, it could also be fed or be reinforced by the team members. This was the case when team members “participated actively,” “spoke up,” and “mimicked leader inclusiveness behavior,” which created new opportunities for the leader to exhibit inclusiveness behavior, such as inviting or reflecting. These behaviors, which showed that team members were engaged and felt included, were conducive to team learning behavior.

Participating actively

Team members participated actively in the team process and made clear they were up for improvement: “The evaluation report rightly demonstrates that collaboration is difficult to judge in [this] assignment. Shall we talk about a better assignment next meeting?” (team member email, May). The different members all kept an overview, checked whether tasks were properly divided among the team members, whether content had been checked for accuracy, and whether all agenda items had been adequately tackled by the end of the meeting. These actions created opportunities for the leader to explicate and connect, such as expressing gratitude and emphasizing team effort. Although recognizing their official leader, members felt they all had an active role in sharing and negotiating ideas, which made them feel committed to making changes to the program: “Everyone is open and honest with each other, in for improvement. There’s simply space to do that, it’s not ‘just do your job’” (student interview, October). As the academic year came to an end, we observed the team making enthusiastic agreements for the next year on sharing the responsibility and workload even more. Meanwhile, individual team members had already made necessary preparations: “Per case, I kept track of possible improvements for next year” (field note, member, December).

Speaking up

We often noticed that, although professional discussions abounded, the atmosphere was relaxed and personal. Laughter, serious discussions, personal reflections, and anecdotes followed each other in rapid succession. Team members shared their successes, doubts, and mistakes, creating opportunities for the leader to reflect and invite by asking questions and stimulating dialogs. All team members voiced their opinions, raised concerns, and made suggestions about the organization of meaningful education for students, in turn giving way to more questions, discussion and negotiation: “I feel free to say whatever I want because I feel valued, no-one will give a stupid remark. I don’t feel like I have to watch my mouth, I don’t have to be secretive” (student interview, October). In addition, team members shared their reflections on past discussions on course-related topics, asking for their fellows’ input and feedback: “Some [comments] were positive, some pointed at improvement. I’d like to receive more concrete feedback to be able to improve this [assignment]” (member email, November). Finally, the team leader and team members openly discussed their knowledge gaps, encouraging the team to reflect even more and to admit their deficiencies too. For example, a member from the social sciences asked: “What’s with this lingo? ‘A space-occupying lesion.’ Is that normal?” (field note, October)

Mimicking leader inclusiveness behavior

We noticed that, when the team leader was absent, the other team members mimicked her inclusiveness behavior, for instance by asking “How is everyone doing?” at the start of the meeting (field note, November). Moreover, when left to their own devices, the team still continued to engage in discussion, sharing ideas and integrating each other’s perspectives to finally come to an agreement, thereby demonstrating high levels of team learning. It was clear that team members were well-informed of the course content and its logistics, and were able to justify their decisions regarding certain assignments. The team leader proudly pointed out that her behavior was “contagious”: “I can see he is doing his best more. He now even thanks me for some things [which is the same as she would do]” (interview, November). Also in their emails to the group, team members used the same positive and inviting expressions, as the following email from a student member illustrates: “With this [positive] feedback, I can imagine that you [leader] look forward to go[ing] for it again, right?!” (student email, May).

Discussion

Rising to the call for greater integration in medical education and the inherent demand for well-functioning teams of teachers from the medical, biomedical, and social sciences,Citation1,Citation2,Citation8 we undertook a case study of a successful interdisciplinary teacher team zooming in on leader inclusiveness behavior. We found that effective leader inclusiveness behavior manifested itself in five actions undertaken by the leader: Coordinating, explicating, inviting, connecting, and reflecting. Being conducive to team learning, these behaviors induced team members to share their knowledge and ideas, build upon each other’s contributions, and to negotiate and integrate different viewpoints to come to shared understandings. In a similar fashion, team members had the potential to promote team learning by participating actively, speaking up, and mimicking leader inclusiveness behavior. These behaviors, which demonstrated that team members were engaged and felt included, reinforced leader inclusiveness behavior exhibited by the leader.

We found that, unlike one-way communication which can be detrimental, two-way interactions between the leader and team members are critical for leader inclusiveness behavior. Promoting team learning behavior calls for specific behaviors on the part of both the team leader and team members. In this respect, our findings allow us to draw two important, albeit tentative, conclusions. First, to promote team learning, the team leader must create an environment that encourages interactions. The leader in our study did so not only by using inviting and connecting language, both verbally and in her email conversations, but also through non-verbal, explicit body language and facial expressions. Importantly, in doing so, she frequently spoke of “we,” “us,” and “our.” Weiss et al.Citation40 however, argued that the use of such inclusive language is more effective when addressed to people who share the same professional background. Since the team under scrutiny in our study was interdisciplinary, we may conclude that the team members went through an identification process where they had come to view themselves as members of a single team and their leader as their representative. The second tentative conclusion is that all team members should engage in shared leadership,Citation41 a term derived from the organizational literature that perfectly captures the behavior and engagement displayed by the members of our successful team. More specifically, these team members demonstrated that they, too, could mimic inclusiveness behavior and take responsibility by contributing ideas, asking questions, and stimulating and convincing each other. Indeed, empirical research on (educational) change and development has shown that shared leadership, when distributed among and stemming from the team members, is a useful source for team effectiveness.Citation41,Citation42

Another important finding arising from our study is that leader inclusiveness behavior plays an important role in creating psychological safety, which in turn, is vital to team learning and team effectiveness. Not only do our findings provide rich information on the way the team leader showed inclusiveness behavior, they also demonstrate that the other team members could foster a safe environment by mimicking leader inclusiveness behavior. Through both of these mechanisms, interactions were encouraged: Everyone felt safe to name issues, question the unknown, show their vulnerability and bring up ideas. In this context, it is important to cite Nembhard and Edmondson’sCitation20 study on neonatal intensive care units that showed that leader inclusiveness positively predicted engagement in quality improvement work, and that this was mediated by safeguarding psychological safety. In contrast to this study, our findings provide rich information on the way a team leader shows inclusiveness behavior, but also demonstrate that other members of a team can foster a safe environment as well by showing leader inclusiveness behavior themselves. This way, our study nicely illustrates the role of team leader inclusiveness behavior in creating psychological safety in an interdisciplinary teacher team.

Other factors that may have contributed to the success of this specific teacher team were the fact that the leader was always ready to explain didactics and had a student-centered focus. Even though she worked with representatives from various professional backgrounds and did not have expertise on all disciplinary course contents, the team leader was able to create an inclusive team environment anyway. By continuously explicating and discussing the course content and course vision, she created a shared goal and language, which earlier studies in healthcare have flagged as a prerequisite for effective teamwork.Citation43 Indeed, the team members explicitly emphasized the importance of her didactical knowledge to the team process. The fact that the leader was passionate about educating the young generation of physicians and was pursuing a master in health professions education may explain this zest for explicating didactics and her student-centered focus.

This study builds on the view that in academic healthcare settings -be they an academic hospital, teaching hospital, or medical school- effective leadership goes beyond traditional leadership understandings. That is to say, rather than focusing on exerting influence, providing answers to technical challenges and directing a group in a certain direction,Citation19,Citation44,Citation45 our research proposes that team members can be engaged in medical education through openness and vulnerability. The engaging, inclusive and reflective leadership approach shown by the team leader in our study suggests that we need a leadership paradigm shift, as scholars in academic medicine were already keen to point out.Citation19 To this we should like to add that, if we want interdisciplinary teacher teams to successfully reach their goals via team learning, an inclusive, engaging, and safe team climate is imperative. By displaying inclusiveness behaviors such as coordinating, explicating, inviting, connecting, and reflecting, the leader plays a crucial role in achieving this goal. Shared leadership occurs when team members mimic this behavior, show active participation, and speak up.

Practical implications

The findings of the present study could stimulate initiatives for the professional development of leaders in education. For instance, formal faculty development programs could be aimed at making leaders aware of their current behavior and coaching them to exhibit the behavioral attributes needed for inclusiveness. Understanding of leadership could be further developed through informal workplace-based learning where leaders reflect on their leadership practices. Earlier research in healthcare has demonstrated that traditional interpretations of leadership still prevail, and are heavily influenced by organizational settingsCitation45,Citation46 which underscores the importance of changes in leadership practices. We call for professional development programs and experiential, workplace-based learning opportunities to maximize teaching around development of leadership understandings, and to align these understandings with modern leadership thinking.Citation30,Citation45

Methodological reflections and implications

One of the merits of our study is that we collected data from different sources on multiple occasions over a prolonged period of time. As such, our approach deviates from classic team research designs that collect data about multiple subjects on only a few occasions. While these research designs are often explanatory, aiming at unraveling causalities, our study was exploratory in nature, aiming at an in-depth understanding of behavior. However, as we sampled only one successful team, we cannot know whether our leader’s behavior was representative of that of other successful leaders. We therefore welcome replications of this research with more teams to further explore leader inclusiveness. On the other hand, our use of three data sources created rich insights that were appropriate to our study purpose. Finally, we realize that the leadership behaviors required of a leader depend on the setting, context, and situation. In our selected case, the successful team was facing a rather complex task, i.e., developing an integrated course. Future research could unravel other effective leadership behaviors in teams facing a routine task or even investigate leadership behavior in unsuccessful teams.

Conclusion

This case study is unique in that it demonstrates how effective leader inclusiveness behavior manifests itself in a successful interdisciplinary teacher team in medical education. Behaviors, interactions, and documents were examined through the lens of team learning and leader inclusiveness behavior. By coordinating, explicating, inviting, connecting, and reflecting, the leader created an environment in which team members felt included, responsible and committed. Team members, on the other hand, participated actively, spoke up, and mimicked leader inclusiveness behavior, which promoted team learning, afforded the leader additional opportunities to exhibit leader inclusiveness behaviors, and reflected shared leadership capacity. The modern, specific leader behaviors identified offer practical suggestions on how to optimally include and engage diverse professionals and students in medical education. Lastly, they open up avenues for future professional development initiatives and research on interdisciplinary team leadership.

Funding information

No funding was obtained for the work represented in the manuscript.

Prior presentations

This study was accepted for presentation at the AmericanEducational Research Association (AERA) 2020 AnnualMeeting San Francisco, CA (Conference Canceled).

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (26.8 KB)Acknowledgments

We wish to thank our participants for their time and continuous enthusiasm. Special thanks go to Guusje Bressers, Anneke van der Niet and the members of the Maastricht University Ethnography Group for their reflections and advice on our methodology. Lastly, we wish to thank Angelique van den Heuvel for her language editing.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

References

- Wilkes M. Medical school in 2029. Med Teach. 2018;40(10):1016–1019. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2018.1507253.

- Harden RM. Ten key features of the future medical school-not an impossible dream. Med Teach. 2018;40(10):1010–1015. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2018.1498613.

- Frenk J, Chen L, Bhutta ZA, et al. Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Lancet. 2010;376(9756):1923–1958. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61854-5.

- The Association of Faculties of Medicine of Canada. The future of medical education in Canada (FMEC): a collective vision for MD education. Ottawa. https://www.afmc.ca/sites/default/files/pdf/2010-FMEC-MD_EN.pdf. Published 2010. Accessed January 10, 2021.

- Irby DM, Wilkerson L. Educational innovations in academic medicine and environmental trends. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(5):370–376. doi:https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.21049.x.

- Neville AJ, Norman GR. PBL in the undergraduate MD program at McMaster University: three iterations in three decades. Acad Med. 2007;82(4):370–374. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e318033385d.

- Harden RM. The integration ladder: a tool for curriculum planning and evaluation. Med Educ. 2000;34(7):551–557. doi:https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2923.2000.00697.x.

- Harden RM, Sowden S, Dunn WR. Educational strategies in curriculum development: the SPICES model. Med Educ. 1984;18(4):284–297. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.1984.tb01024.x.

- Safford MM, Allison JJ, Kiefe CI. Patient complexity: more than comorbidity. The vector model of complexity. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(S3):382–390. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-007-0307-0.

- Stalmeijer RE, Gijselaers WH, Wolfhagen IH, Harendza S, Scherpbier AJ. How interdisciplinary teams can create multi-disciplinary education: the interplay between team processes and educational quality. Med Educ. 2007;41(11):1059–1066. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02898.x.

- Meeuwissen SNE, Gijselaers WH, Wolfhagen IHAP, Oude Egbrink MGA. How teachers meet in interdisciplinary teams: hangouts, distribution centers, and melting pots. Acad Med. 2020;95(8):1265–1273. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000003115.

- Horwitz SK, Horwitz IB. The effects of team diversity on team outcomes: a meta-analytic review of team demography. J Manag. 2007;33(6):987–1015. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206307308587.

- Coyle D. The Culture Code: The Secrets of Highly Successful Groups. London, UK: Cornerstone; 2019.

- Van den Bossche P, Gijselaers WH, Segers M, Kirschner PA. Social and cognitive factors driving teamwork in collaborative learning environments. Small Group Res. 2006;37(5):490–521. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1046496406292938.

- Edmondson AC. Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Adm Sci Q. 1999;44(2):350–383. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2666999.

- Lingard L, McDougall A, Levstik M, Chandok N, Spafford MM, Schryer C. Representing complexity well: a story about teamwork, with implications for how we teach collaboration. Med Educ. 2012;46(9):869–877. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2012.04339.x.

- Edmondson AC. Speaking up in the operating room: how team leaders promote learning in interdisciplinary action teams. J Manag Stud. 2003;40(6):1419–1452. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6486.00386.

- Meeuwissen SNE, Gijselaers WH, Wolfhagen IHAP, Oude Egbrink MGA. Working beyond disciplines in teacher teams: teachers’ revelations on enablers and inhibitors. Perspect Med Educ. 2021;10(1):33–40. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-020-00644-7.

- Lieff SJ, Yammarino FJ. How to lead the way through complexity, constraint, and uncertainty in academic health science centers. Acad Med. 2017;92(5):614–621. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001475.

- Nembhard IM, Edmondson AC. Making it safe: the effects of leader inclusiveness and professional status on psychological safety and improvement efforts in health care teams. J Organiz Behav. 2006;27(7):941–966. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/job.413.

- Edmondson AC, Dillon JR, Roloff KS. Three perspectives on team learning. ANNALS. 2007;1(1):269–314. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/078559811.

- Meeuwissen SNE, Gijselaers WH, Wolfhagen IHAP, Oude Egbrink MGA. When I say … team learning. Med Educ. 2020;54(9):784–785. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14174.

- Decuyper S, Dochy F, Van den Bossche P. Grasping the dynamic complexity of team learning: an integrative model for effective team learning in organisations. Educ Res Rev. 2010;5(2):111–133. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2010.02.002.

- Carmeli A, Reiter-Palmon R, Ziv E. Inclusive leadership and employee involvement in creative tasks in the workplace: the mediating role of psychological safety. Creativ Res J. 2010;22(3):250–260. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2010.504654.

- Appelbaum NP, Dow A, Mazmanian PE, Jundt DK, Appelbaum EN. The effects of power, leadership and psychological safety on resident event reporting. Med Educ. 2016;50(3):343–350. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12947.

- Koeslag-Kreunen M, Van den Bossche P, Hoven M, Van der Klink M, Gijselaers W. When leadership powers team learning: a meta-analysis. Small Group Res. 2018. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1046496418764824.

- Edmondson AC, Bohmer RM, Pisano GP. Disrupted routines: team learning and new technology implementation in hospitals. Adm Sci Q. 2001;46(4):685–716. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/3094828.

- Chang A, Fernandez H, Cayea D, et al. Complexity in graduate medical education: a collaborative education agenda for internal medicine and geriatric medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(6):940–946. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-013-2752-2.

- Stoller JK. Developing physician-leaders: a call to action. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(7):876–878. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-009-1007-8.

- Cadieux DC, Lingard L, Kwiatkowski D, Van Deven T, Bryant M, Tithecott G. Challenges in translation: lessons from using business pedagogy to teach leadership in undergraduate medicine. Teach Learn Med. 2017;29(2):207–215. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10401334.2016.1237361.

- McKimm J, O’Sullivan H. When I say … leadership. Med Educ. 2016;50(9):896–897. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13119.

- Cianciolo AT. Making the most of what we say. Teach Learn Med. 2019;31(1):5–6. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10401334.2018.1550857.

- Lobas JG. Leadership in academic medicine: capabilities and conditions for organizational success. Am J Med. 2006;119(7):617–621. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.04.005.

- Jerolmack C, Khan S. Talk is cheap: ethnography and the attitudinal fallacy. Soc Methods Res. 2014;43(2):178–209. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124114523396.

- Reeves S, Peller J, Goldman J, Kitto S. Ethnography in qualitative educational research: AMEE Guide No. 80. Med Teach. 2013;35(8):e1365–e1379. doi:https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2013.804977.

- Atkinson P, Pugsley L. Making sense of ethnography and medical education. Med Educ. 2005;39(2):228–234. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2929.2004.02070.x.

- King N, Horrocks C, Brooks J. Interviews in Qualitative Research. London, UK: SAGE Publications Limited; 2018.

- Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687.

- Varpio L, Ajjawi R, Monrouxe LV, O’Brien BC, Rees CE. Shedding the cobra effect: problematising thematic emergence, triangulation, saturation and member checking. Med Educ. 2017;51(1):40–50. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13124.

- Weiss M, Kolbe M, Grote G, Spahn DR, Grande B. We can do it! Inclusive leader language promotes voice behavior in multi-professional teams. Leadersh Q. 2018;29(3):389–402. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2017.09.002.

- Pearce CL, Sims HP. Vertical versus shared leadership as predictors of the effectiveness of change management teams: an examination of aversive, directive, transactional, transformational, and empowering leader behaviors. Group Dyn. 2002;6(2):172–197. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037//1089-2699.6.2.172.

- Koeslag-Kreunen MGM. Leadership for Team Learning: engaging University Teachers in Change [doctoral thesis]. Maastricht: Datawyse/Universitaire Pers Maastricht; 2018.

- Stühlinger M, Schmutz JB, Grote G. I hear you, but do I understand? The relationship of a shared professional language with quality of care and job satisfaction. Front Psychol. 2019;10:1310. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01310.

- Mulgan GB. Mind: How Collective Intelligence Can Change Our World. Princeton University Press; 2017.

- Gordon LJ, Rees CE, Ker JS, Cleland J. Dimensions, discourses and differences: trainees conceptualising health care leadership and followership. Med Educ. 2015;49(12):1248–1262. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12832.

- Alizadeh M, Mirzazadeh A, Parmelee DX, et al. Leadership identity development through reflection and feedback in team-based learning medical student teams. Teach Learn Med. 2018;30(1):76–83. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10401334.2017.1331134.