Abstract

Phenomenon: Indigenous and non-Indigenous scholars have called for mentorship as a viable approach to supporting the retention and professional development of Indigenous students in the health sciences. In the context of Canadian reconciliation efforts with Indigenous Peoples, we developed an Indigenous mentorship model that details behavioral themes that are distinct or unique from non-Indigenous mentorship.

Approach: We used Flanagan’s Critical Incidents Technique to derive mentorship behaviors from the literature, and focus groups with Indigenous faculty in the health sciences associated with the AIM-HI network funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Identified behaviors were analyzed using Lincoln and Guba’s Cutting-and-Sorting technique.

Findings: Confirming and extending research on mainstream mentorship, we identified behavioral themes for 1) basic mentoring interactions, 2) psychosocial support, 3) professional support, 4) academic support, and 5) job-specific support. Unique behavioral themes for Indigenous mentors included 1) utilizing a mentee-centered approach, 2) advocating on behalf of their mentees and encouraging them to advocate for themselves, 3) imbuing criticality, 4) teaching relationalism, 5) following traditional cultural protocols, and 6) fostering Indigenous identity.

Insights: Mentorship involves interactive behaviors that support the academic, occupational, and psychosocial needs of the mentee. Indigenous mentees experience these needs differently than non-Indigenous mentees, as evidenced by mentor behaviors that are unique to Indigenous mentor and mentee dyads. Despite serving similar functions, mentorship varies across cultures in its approach, assumptions, and content. Mentorship programs designed for Indigenous participants should consider how standard models might fail to support their needs.

Introduction

Indigenous and non-Indigenous academics have named mentorship as a potent practice supporting the retention of Indigenous students in higher education in general,Citation1–5 and in health sciences specifically.Citation6–12 With this in mind, there is a strong need to invest in the mentorship of Indigenous health professionals and scholars. Doing so would potentially promote cultural safety, career success for Indigenous health professionals, and culturally appropriate health service and research environments,Citation10,Citation13–16 as current services, practices, and approaches to health and health research are not meeting the needs of Indigenous people.Citation17–20 The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) Calls to Action (#23),Citation21 specifically state the need for Indigenous representation in health professions, and by extension, health research. Indigenous people are underrepresented in higher education in general,Citation22 and in the health sciences in particular.Citation23,Citation24 Insomuch that mentorship helps Indigenous students complete post-secondary education, continue into medical school or graduate studies, and perform well in their associated fields, issues of underrepresentation, employment, and income will also be addressed in part, as health careers are highly competitive and in demand.Citation25

Mentorship and associated activities of apprenticeship, role-modeling, and experiential learning in the context of familiar others are aligned with Indigenous modes of transmitting Indigenous knowledge and knowledge systems (e.g., environmental knowledge).Citation26,Citation27 Contemporary academic mentorship, however, varies in form (e.g., hierarchical vs. peer), type (e.g., informal vs. formal), and function (e.g., career-related vs. psychosocial).Citation28 Mentoring is a longitudinal relationship where an experienced mentor guides a less experienced protégé, or “mentee,” that requires different practices depending on the protégé’s stage of development, is affected by characteristics of the mentor and the mentee, and the content of which depends on the program’s purpose and mentoring function.Citation28 While mentorship relationships are generally positive experiences, how mentorship is implemented cross-culturally is not well understood, especially when the mentees are Indigenous. One exception is a set of considerations for Indigenous mentoring programs in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) programs.Citation29 Windchief and BrownCitation29 proposed a model of Indigenous mentorship that included 1) creating an inclusive campus climate, 2) attracting mentors with interest and past success, 3) supporting Indigenous identity with relevant education, 4) making space for Indigenous values, 5) understanding Indigenous family structures, and 6) integrating Indigenous worldviews. Their model weaved together personal communications, literature on Indigenous issues present in the education discourse, and literature on non-Indigenous mentorship to derive relevant program design considerations specific to Indigenous students. It was not a direct investigation of Indigenous mentoring behaviors. The aim of this study was to fill this gap and identify mentorship behaviors that are characteristic of Indigenous approaches to mentoring, distinct from non-Indigenous mentorship, in the interest of supporting pro-retention strategies for Indigenous students in health science careers.

Positionality statement

It is a standard in some qualitative methods (e.g., Emerson et al.Citation30) and regular in Indigenous methodologies (e.g., KovachCitation31; WilsonCitation32) to include a reflexive or positionality statement. In qualitative methods, the purpose is to preemptively address criticisms of bias when the researcher is the instrument instead of psychometrically validated scales or behavioral counts.Citation33 Reflexive statements acknowledge the consciously relevant aspects of the individuals conducting the research that may influence the selection of research questions, the sample, data collection, and interpretation so that readers can calibrate for their bias. It is a mechanism of establishing credibility, the qualitative correspondent term for internal validity.Citation34 In Indigenous methodologies, the statements are similarly for internal validity, but within the philosophical underpinnings of relationalism.Citation31,Citation32 Authors introduce themselves and their relationship to the project in the attempt to build relationship with the readers, from which the readers can contextualize the results.

Research methodologist Linda Tuhiwai Smith [Maori] articulated that Indigenous methods can take two forms.Footnote1Citation35 The first being knowledge creation founded on processes and procedures from traditional societies that are based in Indigenous epistemologies (e.g., relationalism) and ontologies (e.g., interconnectedness). The second form is when Western methods are used for the self-determined interests of Indigenous Nations, communities, agencies, organizations, and populations. As an Indigenous mentorship network of Indigenous and non-Indigenous mentors within a non-Indigenous healthcare system, chartered to offered supports where they do not exist, we choose this second form since it works to translate Indigenous Ways of Doing through a discourse that is familiar to researchers and consumers of research. Indigenous Ways of Doing are not simply cultural practices; they are ways of engaging in behaviors that manifest the belief systems and philosophical assumptions of Indigenous societies (e.g., epistemologies and ontologies).Citation36 It should be noted that our methodology included adherence to many Indigenous ethical expectations in research,Citation37 including a consensus model of decision-making, reciprocity through and within the network, and following traditional protocols (e.g., smudge).

Due to the number of authors on this paper, we only offer brief introductions, but we hope they serve the purposes stated above. The first author is of Ukrainian, Irish, and Apache decent, works as an assistant professor of Indigenous psychology, and serves on the Alberta Indigenous Mentorship in Health Innovation network (AIM-HI, described more in the methods section) evaluation committee as a co-principal investigator (co-PI). The second author is Métis, is a mid-career clinician-scientist in rheumatology and health services research, and is AIM-HI’s PI. The third author is European Settler, Romani, and Shawnee, currently working on their PhD in medical anthropology, has been involved in AIM-HI as a research assistant and as an active mentee within the network. The fourth author is a settler of German, English, and Irish descent, who has worked in diversity-related leadership consulting and activism for over 16 years, and is connected to the project through relationships with the AIM-HI team and a shared mission. The fifth author is of Filipino and Turkish descent and is currently completing their master’s degree in industrial-psychology with the first author. The six author is a European Settler, works as an assistant professor and models of care scientist, and serves on the AIM-HI evaluation committee as a co-PI. The seventh author is a member of Piikani First Nation, works as an associate professor, family physician-scholar, and assistant dean, and serves as a co-PI for AIM-HI.

Method

To explore behaviors that are important to Indigenous mentorship, we used Flanagan’s critical incident technique (CIT).Citation38 The method has five steps: 1) decipher the goals of the sought-after results, 2) operationalize what would count as relevant data, 3) collect the data, 4) analyze the data, and 5) interpret/report the results.Citation38,Citation39 We selected CIT because it is a recognized but flexible method for identifying phenomena that is critical but may not be frequent.Citation39

In step 1, we defined our goal to identify behaviors associated with Indigenous mentorship, informed by experienced Indigenous mentors. In step 2, we operationalized Indigenous mentorship approaches as behaviors that were unique to Indigenous mentoring (see Model Development below), i.e., distinguishable from behaviors that are typical in non-Indigenous mentorship. In step 3, we collected data via a literature review to identify non-Indigenous and Indigenous mentorship behaviors. For Indigenous behaviors, we supplemented the published literature by facilitating focus groups with Indigenous mentors. To analyze the data (step 4), we employed Lincoln and Guba’s cut-and-sort technique to categorize behaviors according to shared content.Citation40 This technique added transparency to CIT because, while Flanagan’s CIT framework describes the use of data from different sources to derive critical incidents, it does not delineate the steps involved during the analysis of data. This cut-and-sort technique is particularly valuable when the qualitative data is in the form of short statements, as opposed to long interviews. Interpretation (step 5) was the joint product of our interdisciplinary team, which represented perspectives in organizational psychology (n = 3), primary health care (n = 2), medical anthropology (n = 2), counseling (n = 1), and sociology (n = 1), six of whom are Indigenous (i.e., First Nations, Métis, and American Indian).

Model development sample and procedure

Since our aim was to identify behaviors characteristic of Indigenous mentorship, our process needed to distinguish between behaviors associated with Indigenous and non-Indigenous mentorship approaches and styles. We followed a parallel process of identifying behavioral categories and behaviors associated with Indigenous and non-Indigenous mentorship.

Non-Indigenous mentorship

We identified behaviors associated with non-Indigenous mentorship through a scan of the education (e.g., DavisCitation41) and organizational psychology literature (e.g., Nick et al.Citation42). This scan emphasized articles in multicultural educationCitation43–47 and cross-cultural competence in organizational settingsCitation48,Citation49 to avoid over-simplifying conceptualizations of contemporary mentorship or falsely attributing mentorship behaviors to Indigenous mentorship that are really characteristic of culturally competent mentoring behaviors. Much of the research focused on protégé perceptions rather than mentor behavior. As a result, our scan did not rely exclusively on empirically-derived mentor behaviors, but on any description of mentor behaviors, whether in a review, an empirical study, or conceptual paper in a peer-reviewed source.Footnote2

Using this liberal standard, it was clear that mentor behaviors occupy significant attention even if mentor behaviors are not often measured. For example, an initial scan by the third author identified 29 mentorship articles of which 11 articles articulated mentor behaviors. From those 11 articles, we extracted 93 mentor behaviors, which satisfied established taxonomies of mentorship roles (i.e., career, academic, and psychosocial support),Citation28,Citation50,Citation51 and quickly became redundant in content. Due to redundancy (referred to as saturation in other qualitative methodsCitation52), we did not continue the search beyond the initial scan. We subjected the extracted non-Indigenous mentorship behaviors to the analytical procedure described below.

Indigenous mentorship

To derive behavioral items related to Indigenous mentorship, we followed the same process of extracting mentor behaviors from the literature specific to Indigenous mentors and students. The process identified 22 articles, of which there were 17 empirical (primarily qualitative) studies on Indigenous mentorship.Footnote3 Mentorship was often called for but infrequently operationalized or defined, with the literature review only producing 29 behaviors.

To supplement this source, we facilitated break out groups with Indigenous mentors at the Alberta Indigenous Mentorship in Health Innovation (AIM-HI) network’s annual retreat, held May 8–10, 2018 in Banff. AIM-HI is part of the national Canadian Institutes of Health Research-funded Indigenous Mentorship Program Network. AIM-HI hosts a range of activities to foster mentoring opportunities (e.g., speaker sessions, retreats, talking circles, sweat lodges) and provides scholarships, research opportunities, and professional development. Members represent a wide range of health fields in academia (e.g., public health, medical anthropology) and medicine (e.g., family medicine). The network is based on a cascading mentorship model, where each person in the network is considered a mentor and mentee simultaneously. AIM-HI’s design is informed by Indigenous epistemologies and values, in that it acknowledges how status (e.g., mentor or mentee) is dependent on the situation, which supports ideas of egalitarianism or flattened power distances, and encourages reciprocity.Citation53,Citation54

On day three of the retreat, two co-PI’s of AIM-HI introduced this project, described the need for identifying Indigenous mentorship behaviors, and facilitated discussions among attendees about their mentoring actions. Three breakout groups were formed, one each to cover mentorship roles available in the educational and organizational literature (i.e., career support, academic support, and psychosocial support).Citation50 Each group had about eight people (N ≈ 24), although counts and demographic information were not collected. There was a note taker assigned to each group, but discussions were not audio-recorded. To keep the focus on uniquely Indigenous mentorship behaviors, we asked Indigenous mentors to give examples of what they do and do not do to provide cultural safety or decolonize the academic space for their Indigenous mentees. The retreat generated an additional 46 behaviors (total items (i) = 75).

Analysis

To identify uniquely Indigenous mentorship behaviors, we applied two rounds of Lincoln and Guba’s cut-and-sort technique to our behavioral items.Citation40 The cut-and-sort technique facilitates a process where individual units of meaning are cut, or represented individually, from a list or text, and then sorted according to shared meaning.Citation55 The process works well when meaning units consist of singular statements rather than dense text.Citation55,Citation56

The first round of cutting-and-sorting was conducted solely on the non-Indigenous behavioral items (i = 93; item list not shown). This was done to confirm the taxonomy of non-Indigenous or mainstream mentorship,Citation57 and establish a behavioral definition of non-Indigenous mentorship with which to identify uniquely Indigenous mentorship behaviors. The first and fourth authors participated in this sorting process. We sorted items as a collaborative exercise, where we discussed, debated, and categorized each behavior after we reached agreement. Although we began with the taxonomy proposed by KramCitation57, because of our novel emphasis on mentor actions, we allowed for novel categories to emerge if they were necessary for making useful distinctions. No category of behaviors depended on contentious or vague items.

In the second round of cutting-and-sorting, we sorted Indigenous mentorship behavioral items (i = 75; see ). Items could be sorted into new categories according to their unique but shared content or into categories from the non-Indigenous model derived in round one. We followed this practice since we assumed some overlap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous mentor practices, but our goal was to isolate uniquely Indigenous mentorship practices. In other words, to identify Indigenous-specific mentor behaviors, we allowed behavioral items derived from the Indigenous literature and AIM-HI retreat to be sorted into categories of non-Indigenous mentorship if they fit there better, in terms of shared content. This helped to ensure our Indigenous mentorship categories were mutually exclusive and therefore more pure representations of Indigenous-specific practices.

Table 1. Indigenous behavioral items by thematic category.

Results

Non-Indigenous mentorship behaviors

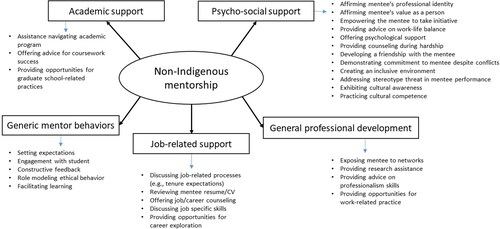

Contrary to expectations, non-Indigenous mentoring behaviors did not fall cleanly into Kram’sCitation57 two-part taxonomy of career-related or psychosocial support, nor into a three-part taxonomy augmented to emphasize academic support for mentoring in academic spaces.Citation50 The sort of non-Indigenous mentorship behaviors produced five categories. Although the number of items are not necessarily reflective of the frequency of actual behaviors, in order of item counts, the five categories were: 1) Psychosocial support (i = 38), 2) General professional development (i = 19), 3) Job-specific support (i = 16), 4) Generic mentorship interactions (i = 11), and 5) Academic support (i = 9; see ). Psychosocial support contained items similar to Kram’s descriptions (i.e., role modeling, acceptance-and-confirmation, counseling, and friendship), as did general professional development (i.e., coaching, protection, challenging assignments, and exposure). Job-related support was unexpected, which was related to more proximal and immediate work formalities (e.g., tenure expectations, job-specific skills). Generic mentorship behaviors were baseline behaviors that did not specify a target for support (e.g., career or otherwise) and were so basic that it would be hard to imagine a mentoring relationship without such behaviors (e.g., setting expectations with mentee, offering constructive feedback, being engaged with mentee). Finally, academic support seemed conceptually different from the other mentoring behaviors in that they were explicitly targeted to success in school rather than in career (e.g., help navigating academic program requirements, providing advice on classwork). See for a diagram of thematic behavioral categories and example behaviors.

Indigenous mentorship behaviors

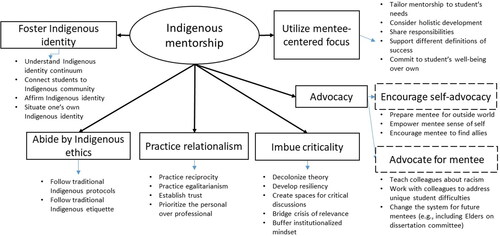

Of the 75 behavioral items identified in the Indigenous mentorship literature and provided by Indigenous mentors in the AIM-HI network, eight were redundant with items in the non-Indigenous mentorship model, leaving a final list of 67 Indigenous-specific mentorship behaviors to be sorted. In order of the item count, Indigenous mentorship behaviors clustered into seven categories: 1) Utilize a mentee-centered focus (i = 19), 2) Teach students’ self-advocacy (i = 10), 3) Imbue criticality (i = 9), 4) Abide by Indigenous ethics (i = 8), 5) Practice relationalism (i = 8), 6) Facilitate positive Indigenous identity development (i = 7), and 7) Advocate on behalf of Indigenous students (i = 6; see ). There was nearly equal representation of each category in the literature and the breakout group data, except practice relationalism, which appeared more in the literature, and advocacy, both encouraging self-advocacy and advocating on behalf of mentees, which appeared more at the retreat.

details the items within the six categories. Items provide the nuance of each construct and collectively give a description of the category-level construct. For example, in what we called “mentee-centered focus,” the literature depicted Indigenous mentors assisting students with their personal vision, making space for topics students want to talk about in lab meetings, understanding and using mentee’s lived experiences for motivation, and showing concern for students’ well-being. However, the mentors in breakout groups expanded on this saying, “not to save, fix, or mold the mentee,” that areas of development need to be identified, not assumed, and that what is good for the students should be conceptualized in terms of what fits into the larger context of their life and within their definition of success. In the Indigenous context, this category is not about career or professional development from a top-down approach to mentoring, where the mentor is positioned as the knower of what is right for the mentee. As one mentor put it, “If a mentor is not happy with [the mentee’s] direction, that is your problem, not the mentees’.”

When Indigenous mentors encouraged self-advocacy, the literature described them as attempting to empower Indigenous students and talking about balancing culture with expectations of the academy. Mentors in our network provided more detail, saying that they tell their mentees to “never believe that they are less,” use adverse moments as teaching moments, and preemptively discuss conflicts between academic expectations and cultural values and how to resolve them. Importantly, advocating for oneself included building relationships shrewdly. Multiple comments were made that Indigenous students should be careful who they socialize with, not to pursue psychological support if they feel unsafe, and to find or make allies with supportive non-Indigenous individuals who are likeminded and/or share similar values.

Indigenous mentors imbue criticality. In the literature, this meant that Indigenous mentors helped bridge the crisis of relevance and created spaces for critical discussions about research and inquiry.Citation58 Mentors in our network said they helped students understand and navigate academic bureaucracy. This included hard advice to deconstruct colonial “engraining,” not to absorb the institutional mindset, and, provocatively, to behave institutionalized. As principal investigators, we have experienced this in our own lives. One non-Indigenous member of our team has witnessed Indigenous students performing differently during discussions than on written exams, where Indigenous students answered in ways that were more conventional and institutionalized in writing. In a discussion of these results, another member of our team recollected the need to suppress or repackage knowledge that came through traditional modes (e.g., dreams) in ways that are acceptable within Western methods.

Indigenous mentors abide by the rules of etiquette and protocol specific to the Indigenous community in question. This is both to role model these behaviors for mentees who may be disconnected from their culture or unacquainted with these practices, and to help mentees who are more traditional feel welcomed and comfortable. For example, in the literature, Indigenous mentors reported using traditional protocols and practices such as smudge, talking circles, gifting, starting with prayer, song, or reflexive introductions. In the breakout groups, mentors focused on etiquette more than protocols. Mentors described the need to “pace yourself in conversations,” “leave empty space during conversations,” emphasize listening over hearing, and encourage input from multiple mentors and significant friends and family.

Indigenous mentors practice relationalism. Although articulating the relational worldview is beyond the scope of this article, briefly speaking, it is an ontological position which recognizes reality as a set of interconnected and interdependent relationships.Citation32,Citation59–61 This ontology is lived and expressed through ethical, spiritual, and legal systems and obligations that emphasize respect, egalitarianism, reciprocity, and rapport, among others, with other humans, as well as with living and non-living relatives, often denoted by the phrase “All my relations.”Citation58,Citation61 Most of these behaviors were derived from the literature, which strongly emphasized reciprocity (e.g., establishing trust through reciprocity, encouraging and demonstrating reciprocity of benefits, and giving tips for how to integrate respect and reciprocity in research and professional life). Mentors within our network spoke to this in a minor way, emphasizing advice for egalitarianism, “Always believe that you are equal at the table,” and meaningful relationships that “prioritize the personal over the professional.”

Indigenous mentors facilitate their mentee’s identity development. The literature spoke to mentors affirming their Indigenous identity, working with other mentors to identify areas of difficulty, and connecting students to Indigenous communities. Mentors in our network affirmed connecting mentees to Indigenous communities; however, they also included the mentor’s responsibility to know where they themselves come from, and emphasized supportive peer environments.

Finally, Indigenous mentors advocate on behalf of their mentees when they are not around. All of these items came from mentors in our network. They argued that mentors have the responsibility to teach colleagues about racism, help fellow faculty integrate strategies for inclusion, advocate for Indigenous community members’ presence on thesis and dissertation committees, allow for alternative forms of theses/dissertations (e.g., in traditional languages; storied form), and building infrastructure to control research (e.g., community control).

Discussion

We adapted a well-known qualitative technique (CIT) to decipher and identify behaviors associated with Indigenous approaches to mentoring in the health sciences. We empirically distinguished and delineated Indigenous mentorship behaviors from a set of non-Indigenous mentorship behaviors, and grouped these Indigenous behaviors into seven categories (or themes). These categories inform our model of Indigenous mentorship for the health sciences.

Implications

This study has multiple implications. Firstly, the behavioral Indigenous mentorship categories we derived help to validate the lived experiences of Indigenous people in health sciences education and professions. There are behaviors that emphasize traditional cultural motivations, some to reconnect mentees with culture and community, and others that represent survivance within institutions that have been historically unaccommodating to Indigenous cultures and racist toward Indigenous Peoples. These behavioral categories reflect the needs of Indigenous students and demonstrate the social capital that Indigenous mentors offer in a mentoring relationship. Indigenous mentorship behaviors are in addition to non-Indigenous approaches. These behaviors involve additional time and mental, emotional, and spiritual resources, and need to be considered as invisible work insomuch that they are not recognized by one’s institutions.Citation62 We hope this model helps to bring visibility to investments of mentors.

Secondly, these behavioral categories help to inform what cultural competence entails with regard to mentoring Indigenous students. If mentors and mentorship programs are asking how to support their Indigenous students, this model is a place to start. Previous research on cultural competence with Indigenous populations has shown that health practitioners misunderstand what competence implies, and are encouraged instead to work toward cultural humility.Citation63 Although the distinction is contested,Citation64 there are definite overlaps with the cultural humility construct (e.g., egolessness, self-awareness) and elements of our model (e.g., egalitarianism, reflexive awareness).Citation65

Third, we articulated ways that the construct of mentorship is similarly and differently enacted depending on whether one’s model of mentorship was Indigenous or non-Indigenous. This is important for theoretical development and questions around construct equivalence. For example, the most popular behaviors in the Indigenous model were related to a mentee-centered focus. Mentee-centeredness, where mentors do not assume that they know by default the best course of action for an individual, resembles in some ways the Leader-Member Exchange (i.e., LMX) theory in organizational psychology,Citation66 where leadership is a process of tailoring leadership style to the needs of the individual employee. At the same time, mentee-centered focus had nuances that are culturally significant (e.g., holism, egalitarianism) that differ from LMX.

Fourth, although we did not measure rates of behavior, our study adds to the research on mentorship by prioritizing behaviors as the construct of interest. We tried to avoid focusing on mentor attitudes, beliefs, endorsements, values, feelings, motivations, or agreements, and instead focused on what mentors do. This is not to neglect the significance of these other factors, and, no doubt, these constructs are intermingled with the behaviors that are associated with them. However, we viewed them as one level removed from the mentorship interaction and wanted to provide concrete ways of describing the phenomenon to inform individual mentors and mentorship program practices. Arguably, mentor behaviors can be assessed through mentee perceptions, as is the approach with most studies. The issue with that decision is that it fails to consider that impacts may not be intentional, behaviors may be misconstrued, and mentor behaviors may be invisible to their beneficiaries until significant time has lapsed. The focus on mentor, even mentor-reported, behaviors is a slight but significant shift in the conceptual target of mentorship research that we hope will generate more attention.

Finally, this study has implications for how we think about non-Indigenous mentorship. Through a sorting analytical techniqueCitation40,Citation55 couched within a larger generative behavioral identification technique,Citation38,Citation39 we found that non-Indigenous mentorship was more complicated than the two-factor psychometric structure of mentee perceptions previously shown.Citation50,Citation57,Citation67 Apart from a set of minimal mentorship behaviors, career support broke down into job preparation (academic), job (immediate), and career (future) supports. Presumably, mentors might vary across all of these dimensions, and supports may vary in their relationships with mentee outcomes. The mentoring dimension of psychosocial support held in this study, and it was the most popularly discussed of all mentorship behaviors. This may be an indicator that mentors primarily fulfill psychosocial-supportive roles. Another explanation is the reliance on literature in multicultural education and cross-cultural organizational psychology. It is possible that cultural minorities seek out mentors more for psychosocial support and thus our sampling method oversampled this perspective.Citation28,Citation68 We also identified a set of minimal mentorship behaviors. Our sampling method allowed us to make the claim that Indigenous mentoring behaviors are distinguishable from similar culturally-inclusive approaches to mentoring (e.g., culturally inclusive, sensitive, or competent mentoring).

Applications

The results of this study inform mentoring practices in the health sciences and inclusion of Indigenous Ways of Doing in academia.Citation5,Citation29,Citation36 Specifically, the model of Indigenous mentoring behaviors we identified can be used to inform training materials for non-Indigenous and Indigenous mentors alike who mentor Indigenous students, for evaluations of mentors within an Indigenous mentorship programs, as a self-assessment tool, and a small strategy to decolonize institutional spaces (e.g., hospitals, educational institutions). We are currently developing training and self-assessment materials built on this model to support mentor preparation in the Indigenous Primary Health Care and Policy Research network. This model may also inform other variations for mentoring, such as formal matched mentorship programs or peer-mentoring.

Limitations

This study has several notable limitations. Firstly, the original aim of this project was not to develop a model of Indigenous mentorship. Rather, it started as an applied project with the AIM-HI leadership team to inform mentor development in the network. We agreed that our assessment practices should match the intentions of the network, and that it was counterintuitive and even culturally inappropriate to ask mentors to participate in an Indigenous-supportive program only to assess them by non-Indigenous standards. Due to the immediate need, we operated within the practical constraints of time, human resources, funding, and coordination. One compromise was to end early the literature reviews from which we derived all of the non-Indigenous behavioral items and about 40% of the Indigenous behavioral items. Ideally, our scan for behaviors would have drawn on a larger body of work.

An important set of limitations surrounding our study was the nuance accounted for or included in our design. For example, we did not assess how Indigenous mentorship behaviors get tailored to mentees’ development stages. EbyCitation28 outlined that mentees need different things based on their phase of employment (i.e., exploring, trial, or established). It is unclear whether Indigenous mentorship support also changes depending on the stages, occupational or otherwise, other than to say that the holistic needs of the mentee should be at the forefront. A similar limitation was a lack of exploration into the age, tenure, extent of Indigenous identification, and other individual differences of the mentors in question. It is possible that mentoring practices differ depending on 1) the age or gender match up, 2) if there are differences in authority between the pair, 3) whether the pair involved individuals who are mixed-race or non-Indigenous, 4) the location of both on the spectrum of assimilation, or 5) whether mentorship behaviors hold across disciplines.

Future steps

In addition to addressing the limitations mentioned above, future research should investigate the validity of this model. As mentors, we are certain that Indigenous mentors use non-Indigenous mentoring approaches. Research that tests the structural uniqueness of our Indigenous mentorship constructs through quantitative scales may show that some or all of our Indigenous mentorship behavioral categories rightfully belong under the umbrella of psychosocial supportive behaviors (e.g., fostering identity development) or its sub-domains (e.g., advocacy and protection [KramCitation57]). As many mentorship scales assess the mentee perspective, mentor-side assessment for Indigenous and non-Indigenous models may reveal different associations. Future research should also inspect the predictive validity of our Indigenous mentorship model on mentee (e.g., career advancement) and mentor outcomes (e.g., career satisfaction), hopefully showing incrementally explained variance over non-Indigenous mentorship practices. We are in the process of some of this validity work now. Following a demonstration of this model’s validity, a natural next step for a mentorship model is its utility in mentors’ self-assessment or training tool. Future research should investigate Indigenous and non-Indigenous responses to this model and outcomes of training based on it.

Finally, future research should investigate this model’s validity within Band, Nation, or Tribe, or with different Indigenous populations (e.g., Urban-based). We labeled our mentorship model using the broad term “Indigenous” because the data involved an intertribal (e.g., Cree, Blackfoot, Metis, Ojibwe, Anishinaabe, Maori, Aborigine or Torres Strait Islander, Alaskan Native) and international (i.e., Canada, United States, Australia, and New Zealand) sample of Indigenous mentors through the literature review and focus groups. Our intent was not to ignore important cultural, hereditary, political, or other differences, or suggest that these are inconsequential. Rather, the intent of our model was to provide evidence that Indigenous ways of mentoring exist and offer broad enough categories that multiple constituencies of Indigenous students, programs, and mentors will find it useful and easily adaptable. It is also important to note that our network’s location resides largely in urban healthcare organizations that often serve diverse Indigenous populations and hire from a diverse Indigenous applicant pool. Results may differ should a mentorship model emerge organically at a health or wellness center on reserve/reservation, with a particular Nation spread across reserves/reservations, or in more rural areas.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of Drs. Jennifer Leason (Anishnaabe), Robert Henry (Métis), Cheryl Currie, Karlee Fellner (Cree/Métis), and Cora Voyageur (Chipewyan Dene), who were instrumental in the network’s implementation and the development of it’s vision as co-principal investigators.

Data availability statement

Data for Indigenous behavioral items are included in . Data that support the findings for non-Indigenous items and categories are available from the corresponding author, Adam Murry, upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

Funding

Notes

1 P. 128.

2 For a full list of these sources, contact the author.

3 Ibid.

References

- Archibald JA, Aquash M, Kelly V, Cranmer L. Indigenous knowledges and education (ECE-12). Can J Native Ed. 2009;32(1):1–4.

- Bodkin-Andrews G, Carlson B. Racism, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander identities, and higher education: reviewing the burden of epistemological and other racisms. Seed Succ in Indig Austr High Educ. 2013;14:29–54. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/S1479-3644(2013)0000014002.

- Mosholder RS, Waite B, Larsen CA, Goslin C. Promoting Native American college student recruitment and retention in higher education. Multicult Educ. 2016;23(3-4):27–36.

- Pidgeon M, Archibald J, Hawkey C. Relationships matter: supporting aboriginal graduate students in British Columbia, Canada. CJHE. 2014;44(1):1–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.47678/cjhe.v44i1.2311.

- Rawana JS, Sieukaran DD, Nguyen HT, Pitawanakwat R. Development and evaluation of a peer mentorship program for Aboriginal university students. Can J Educ. 2015;38(2):1–34. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/canajeducrevucan.38.2.08.

- Aramoana J, Alley P, Koea JB. Developing an Indigenous surgical workforce for Australasia. ANZ J Surg. 2013;83(12):912–917. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/ans.12362.

- Elston KJ, Saunders V, Hayes B, Bainbridge R, McCoy B. Building Indigenous Australian research capacity. Contemp Nurse. 2013;46(1):6–12. doi:https://doi.org/10.5172/conu.2013.46.1.6.

- Felton-Busch C, Maza K, Ghee M, et al. Using mentoring circles to support Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nursing students: guidelines for sharing and learning. Contemp Nurse. 2013;46(1):135–138. doi:https://doi.org/10.5172/conu.2013.46.1.135.

- Flores G, Mendoza FS, DeBaun MR, et al. Keys to academic success for under-represented minority young investigators: recommendations from the research in academic pediatrics initiative on diversity (RAPID) national advisory committee. Int J Equity Health. 2019;18(1):93. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-019-0995-1.

- Richmond C. Try bravery for a change: supporting Indigenous health training and development in Canadian universities. Aborig Policy Stud J. 2018;7(1):180–189. doi:https://doi.org/10.5663/aps.v7i1.29342.

- Walters KL, Simoni JM. Decolonizing strategies for mentoring American Indians and Alaska Natives in HIV and mental health research. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(S1):S71–S6. doi:https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2008.136127.

- Viets VL, Baca C, Verney SP, Venner K, Parker T, Wallerstein N. Reducing health disparities through a culturally centered mentorship program for minority faculty: the Southwest Addictions Research Group (SARG) experience. Acad Med. 2009;84(8):1118–1126. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181ad1cb1.

- Papps E, Ramsden I. Cultural safety in nursing: the New Zealand experience. Int J Qual Health Care. 1996;8(5):491–497. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/8.5.491.

- Fridkin AJ. Addressing health inequities through Indigenous involvement in health-policy discourses. Can J Nurs Res. 2012;44(2):108–122.

- Vogel L. Medical schools to boost numbers of Indigenous students, faculty. CMAJ. 2019;191(22):E621. doi: https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.l09-5753.

- Parker M, Pearson C, Donald C, Fisher CB. Beyond the Belmont principles: a community-based approach to developing an Indigenous ethics model and curriculum for training health researchers working with American Indian and Alaska Native Communities. Am J Community Psychol. 2019;64(1-2):9–20. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12360.

- Allan B, Smylie J. First Peoples, Second Class Treatment: The Role of Racism in the Health and Well-Being of Indigenous Peoples in Canada, Discussion Paper. Toronto, ON: Wellesley Institute; 2015.

- Jacklin KM, Henderson RI, Green ME, Walker LM, Calam B, Crowshoe LJ. Health care experiences of Indigenous people living with type 2 diabetes in Canada. CMAJ. 2017;189(3):E106–E112. doi:https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.161098.

- Thurston WE, Coupal S, Jones CA, et al. Discordant Indigenous and provider frames explain challenges in improving access to arthritis care: a qualitative study using constructivist grounded theory. Int J Equity Health. 2014;13(1):46–10. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-9276-13-46.

- Tjepkema M, Bushnik T, Bougie E. Life expectancy of First Nations, Métis and Inuit household populations in Canada. Health Rep. 2019;30(12):3–10. doi:https://doi.org/10.25318/82-003-x201901200001-eng.

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC). Honouring the truth, reconciling for the future. Government of Canda: Library and Archives Canada. http://www.trc.ca/about-us/trc-findings.html. Published 2015. Accessed April 21, 2021.

- National Household Survey (NHS). The Educational Attainment of Aboriginal Peoples in Canada. Ottawa, Ontario: Minister of Industry, Statistics Canada; 2013.

- Dhalla IA, Kwong JC, Streiner DL, Baddour RE, Waddell AE, Johnson EL. Characteristics of first-year students in Canadian medical schools. Can Med Assoc J. 2002;166(8):1029–1035.

- Mian O, Hogenbirk JC, Marsh DC, Prowse O, Cain M, Warry W. Tracking Indigenous applicants through the admissions process of a socially accountable medical school. Acad Med. 2019;94(8):1211–1219. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002636.

- Government of Canada. Canadian Occupational Projection System (COPS)—2019 to 2028 projections. Employment and Social Development Canada. https://open.canada.ca/data/en/dataset/e80851b8-de68-43bd-a85c-c72e1b3a3890. Accessed May 12, 2020.

- Battiste M. Indigenous Knowledge and Pedagogy in First Nations Education: A Literature Review with Recommendations. Ottawa, ON: National Working Group on Education; 2002.

- Cristancho S, Vining J. Perceived intergenerational differences in the transmission of Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) in two Indigenous groups from Columbia and Guatemala. Cult Psychol. 2009;15(2):229–254. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1354067X09102892.

- Eby LT. Mentoring. In: Zedeck S, ed. APA Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology: Selecting and Developing Members for the Organization. Vol. 2. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2011:505–525.

- Windchief S, Brown B. Conceptualizing a mentoring program for American Indian/Alaska Native students in the STEM fields: a review of the literature. Mentor Tutoring. 2017;25(3):329–345. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13611267.2017.1364815.

- Emerson RM, Fretz RI, Shaw LL. Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press; 1995.

- Kovach M. Indigenous Methodologies: Characteristics, Conversations, and Contexts. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press; 2009.

- Wilson S. Research is Ceremony. Halifax, NS: Fernwood Publishing; 2008.

- Willig C. Interpretation and qualitative research. In: Willing C, Rogers WS, eds. The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research in Psychology. London, UK: Sage; 2017:274–288.

- Golafshani N. Understanding reliability and validity in qualitative research. Qual. Rep. 2003;8(4):597–606.

- Smith LT. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. London, UK: Zed Books Ltd; 2012.

- Drummond A. Embodied Indigenous knowledges protecting and privileging Indigenous peoples’ ways of knowing, being, and doing in undergraduate nursing education. Aust J Indig Educ. 2020;49(2):127–134. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/jie.2020.16.

- Ball J, Janyst P. Enacting research ethics in partnerships with Indigenous communities in Canada: “do it in a good way”. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2008;3(2):33–51. doi:https://doi.org/10.1525/jer.2008.3.2.33.

- Flanagan JC. The critical incident technique. Psychol Bull. 1954;51(4):327–358. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/h0061470.

- Butterfield LD, Borgen WA, Amundson NE, Maglio AT. Fifty years of the critical incident technique: 1954-2004 and beyond. Qual Res J. 2005;5(4):475–497. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794105056924.

- Lincoln Y, Guba EG. Naturalistic Inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1985.

- Davis DJ. Mentorship and the socialization of underrepresented minorities into the professoriate: examining varied influences. Mentor Tutoring. 2008;16(3):278–293. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13611260802231666.

- Nick JM, Delahoyde TM, Del Prato D, et al. Best practices in academic mentoring: a model for excellence. Nurs Res Prac. 2012;2012:1–9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/937906.

- Alvarez A, Abriam-Yago K. Mentoring undergraduate ethnic-minority students: a strategy for retention. J Nurs Educ. 1993;32(5):230–232. doi:https://doi.org/10.3928/0148-4834-19930501-11.

- Brown RT, Daly BP, Leong FTL. Mentoring in research: a developmental approach. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 2009;40(3):306–313. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0011996.

- Chan AW, Yeh CJ, Krumboltz JD. Mentoring ethnic minority counseling and clinical psychology students: a multicultural, ecological, and relational model. J Couns Psychol. 2015;62(4):592–607. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000079.

- Feldman MD, Arean PA, Marshall SJ, Lovett M, O’Sullivan P. Does mentoring matter: results from a survey of faculty mentees at a large health sciences university. Med Educ Online. 2010;15(1):5063. doi:https://doi.org/10.3402/meo.v15i0.5063.

- Lewis V, Martina CA, McDermott MP, et al. Mentoring interventions for underrepresented scholars in biomedical and behavioral sciences: effects on quality of mentoring interactions and discussions. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2017;16(3):1–11. doi:https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.16-07-0215.

- Baylor University. Baylor University’s Community Mentoring for Adolescent Development. Waco, TX: Baylor University; 2004:56–74.

- Osula B, Irvin SM. Cultural awareness in intercultural mentoring: a model for enhancing mentoring relationships. Int J Leadersh Stud. 2009;5(1):37–50.

- Eby LT, Allen TD, Evans SC, Ng T, DuBois DL. Does mentoring matter? A multidisciplinary meta-analysis comparing mentored and non-mentored individuals. J Vocat Behav. 2008;72(2):254–267. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2007.04.005.

- Noe RA. An investigation of the determinants of successful assigned mentoring relationships. Pers Psychol. 1988;41(3):457–479. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1988.tb00638.x.

- Corbin J, Strauss A. Grounded theory research: procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qual Sociol. 1990;13(1):3–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00988593.

- Brant CC. Native ethics and rules of behaviour. Can J Psychiatry. 1990;35(6):534–539. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/070674379003500612.

- Cajete GA. The Native American learner and bicultural science education. In: Swisher K, Tippeconnic J, eds. Next Steps: Research and Practice to Advance Indian Education. Charleston, WV: Eric Publications; 1999:135–160.

- Ryan GW, Bernard HR. Techniques to identify themes. Field Methods. 2003;15(1):85–109. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X02239569.

- Murry AT, Wiley J. Barriers and solutions: directions for organizations that serve Native American parents of children in special education. J Am Indian Educ. 2017;56(3):3–33. doi:https://doi.org/10.5749/jamerindieduc.56.3.0003.

- Kram KE. Mentoring at Work: Developing Relationships in Organizational Life. Glenview, IL: Scott Foresman; 1985.

- Kirkness VJ, Barnhardt R. First nations and higher education: the four R’s – respect, relevance, relevance, reciprocity, responsibility. In: Hayoe R, Pan, J, eds. Knowledge across Cultures: A Contribution to Dialogue among Civilizations. Hong Kong: Comparative Education Centre, The University of Hong Kong; 2001:1–17.

- Room NR. Reviewing the transformative paradigm: a critical systemic and relational (Indigenous) lens. Syst Pract Action Res. 2015;28(5):411–427. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11213-015-9344-5.

- Verbos AK, Humphries M. A Native American relational ethic: an Indigenous perspective on teaching human responsibility. J Bus Ethics. 2014;123(1):1–9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1790-3.

- Aikenhead GS, Ogawa M. Indigenous knowledge and science revisited. Cult Stud Sci Educ. 2007;2(3):539–620. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11422-007-9067-8.

- June AW. The invisible labor of minority professors. Chron Hi Ed. 2015;62(11)A32. https://www.chronicle.com/article/the-invisible-labor-of-minority-professors/

- Isaacson M. Clarifying concepts: cultural humility or competency. J Prof Nurs. 2014;30(3):251–258. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.profnurs.2013.09.011.

- Danso R. Cultural competence and cultural humility: a critical reflection on key cultural diversity concepts. J Soc Work. 2018;18(4):410–430. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1468017316654341.

- Foronda C, Baptiste DL, Reinholdt MM, Ousman K. Cultural humility: a concept analysis. J Transcult Nurs. 2016;27(3):210–217. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1043659615592677.

- Nishii LH, Mayer DM. Do inclusive leaders help to reduce turnover in diverse groups? The moderating role of leader-member exchange in the diversity to turnover relationship. J Appl Psychol. 2009;94(6):1412–1426. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017190.

- Tepper K, Shaffer BC, Tepper BJ. Latent structure of mentoring function scales. Educ Psychol Measure. 1996;56(5):848–857. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164496056005013.

- Ragins BR. Diversified mentoring relationships in organizations: a power perspective. AMR. 1997;22(2):482–521. https://www.jstor.org/stable/259331 doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/259331.